Abstract

Alcohol has many effects throughout the body. The effect on circadian rhythms and the correlation of these effects to withdrawal effects of alcohol present interesting findings. By measuring 3 planes of activity of female Sprague-Dawley rats during alcohol usage and continuing study through the first two days following withdrawal of alcohol allow for the observation of a drastic modulation of the circadian pattern of activity.

Introduction

The Greek poet Hesiod wrote in 700 B.C., “Of themselves, diseases come among men, some by day and some by night. Whoever wishes to pursue the science of medicine in a direct manner, must first investigate the seasons of the year and what occurs in them.” (41). Patterns of health and homeostasis have been noted throughout history. The observable daily pattern in humans is that of circadian rhythmicity. Human circadian rhythms have been noted in a wide range of aspects of homeostasis, including physiology, behavioral, endocrinology, neurology, and metabolism (48). It is argued that “the concept of homeostasis should be extended to include the precisely timed mechanisms of the circadian timing system which enables organisms to predict when environmental challenges are most likely to occur…It must be concluded that the day-night cycle of the natural environment has played a fundamental role in shaping the evolutionary development of homeostatic mechanisms because of the dominating predictability of diurnal changes in illumination, temperature, food availability, and predator activity.” (28). The circadian rhythm is controlled by an internal “clock” in mammals, which is located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), found in the anterior hypothalamus (36,40,47,48). The SCN receives information about levels of light via the retinohypothalamic tract (29,36).

Disruption of circadian rhythms can have many effects. For instance, there are short term conditions such as jet lag and its associated symptoms of fatigue, disorientation and insomnia (3,41). Disruption of circadian rhythms can also be seen in numerous long term diseases. It has been noted in everything from arthritis, asthma, cancer and diabetes to heartburn, heart disease, hypertension, multiple sclerosis, and stroke (41). Although there is mounting evidence for chronotherapy, the process of synchronizing treatment with body rhythms, for being successful in the administration and effectiveness of drug therapies (41), there is little knowledge of how drugs themselves impact circadian rhythms.

Alcoholic beverages have been consumed for centuries for a variety of purposes, including hygienic, anesthetic, religious, and recreational. Alcohol, specifically ethanol, is hydrophobic in nature, which allows it to cross cell membranes easily. So once alcohol is in the bloodstream it can diffuse into nearly every tissue in the body, including the brain. The actual site of action, however, remains controversial (43). Initially, alcohol crosses the blood brain barrier and produces feelings of relaxation and cheerfulness by causing the release of dopamine and serotonin in the nucleus accumbens, the brain’s pleasure center (50). Further exposure results in alcohol’s dose-dependant CNS depression, leading to ataxia, slurred speech, blurred vision, slowed reaction times, and uninhibited behavior (15,18,19,20). In addition to alcohol’s depressive actions, repetitious alcohol consumption elicits tolerance and withdrawal effects. Tolerance occurs when a subject’s reaction to a drug decreases after repeated exposure so that larger doses are required to achieve the same effect (13,15,18,19,20,34). The body makes adaptations to the drug which requires that more of the drug the applied in order to reach the same bodily changes produced by the drug. Once these adaptations are set, the body then becomes dependent on the drug, needing it to function physiologically in the same manner (15,18,19,20). These adaptations remain after use of the drug is discontinued and subsequently appear as “withdrawal” signs and symptoms which are commonly the opposite effects that the drug produces. Alcohol withdrawal symptoms classically consist of hyperexciteability and insomnia (6,8,15,18,19,20)

Nearly all of the published studies on the effects of alcohol analyze the effects of the drug during usage and immediately following cessation of the treatment. No studies to date have looked at how the drug modulates the behavioral circadian rhythm, not only during intoxication and immediately following cessation, but also for the subsequent hours and days following the termination of treatment. We hypothesize that chronic alcohol administration will alter the behavioral circadian rhythm activity and that subsequent withdrawal of the alcohol will cause changes in the circadian rhythm that will produce the symptoms of alcohol withdrawal.

Methods

Animals

Pregnant, female Sprague-Dawley rats (n=38) weighing from 160–190 g were housed in the experimental room in groups of four at an ambient temperature of 21 ± 2 °C and a relative humidity of 37–42%. The rats were acclimated to the test environment for seven days prior to experimentation on a 12:12 h light (07:00–19:00)/dark (19:00-07:00) cycle. At the beginning of the experiment all rats were weighed and individually housed in Omnitec Digiscan RXYZM DVA animal activity computerized monitoring system test cages. After 12 hours of accommodation to the test cages, rats were continuously monitored (sample time: 10 min) throughout the 24 hour cycle for 16 days (1,7,16).

Testing Apparatus

The test chambers for constant activity monitoring consisted of clear acrylic open field boxes (40.5×40.5×31.5) with 2 levels of infrared motion sensors consisting of 16 infrared beams spaced 2.5 cm apart. The first and second levels of sensors were 6 cm and 12.5 cm above the cage floor, respectively. The activity monitoring system checked each of the beams at a frequency of 100 Hz to determine whether the beams were interrupted. The interruption of any beam was recorded as an activity score. Interruptions of two or more beams separated by at least a second was recorded as a movement score. The total distance traveled in centimeters was calculated from the total number of beams interrupted in consecutive sequence. Cumulative counts were complied and downloaded every 10 minutes into OASIS data collection program, and organized into 24 motor indices (1,7,16).

Horizontal activity measures the amount of movement along the floor of the cage. Vertical 1 measures any sort of activity above the floor, as in standing or rearing of the head. Vertical 2 requires that the rat be fully extended along the wall of the cage, as in reaching or jumping.

Procedure

The first 3 days of recording served as a baseline measurement of activity for each individual rat so they could serve as their own control on the days of alcohol consumption (1,16). During this time, food pellats and water were continuously supplied. During the experiment, ethanol was administered in the following manner: free access to a nutritionally balanced liquid diet containing ethanol (5%, w/v, 36% ethanol-derived calories) was available. The average daily intake of ethanol was 19.9 ± 0.8 g/kg, which was previously found to produce blood ethanol levels of 198 ± 6 mg/dl (9).

Data Analysis

Twenty-four hour activity patterns were evaluated for the three levels of activity indicated above and plotted displaying the hourly means and standard deviations. The original histograms were evaluated and paired data points reflecting the appropriate hourly means a standard deviations. These paired data points were characterized by fitting a cosine curve with a twenty-four hour period. Such curves are typically parameterized by estimating the mesor (baseline, average), amplitude (distance from mesor to highest point), and acrophase (time at which the maximum occurs) using the cosinor analysis procedures and f-tests for statistical significance as described by et al., (2). Table 1 displays the days on which activity was measured and the corresponding experimental description. Parameter estimates of the cosine curves with the appropriate standard errors and p-values are presented in Table 2. Here the standard errors of the mesor estimate are presented; however for presentation of the results below the mesor estimate and amplitude of the cosine are represented as the mesor value ± a second amplitude estimate. Table 3 displays the tests for significance of the parameter estimate differences. Activity for the control days were evaluated to determine whether the days could be pooled as an overall control group. Representative treatment days were compared to the control group and to other treatment days using appropriate F-tests to qualify the effects of the treatment changes on the activity patterns. Representative plots contrasting specific treatment days with control days were constructed to visually present the effects of various stages in the treatment cycle. F-tests contrasting cosine parameter estimates were computed to test for significant differences between parameter estimates.

Table 1.

Summary of the days, general treatment categories, and treatment phase.

| Day | Treatment Group | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Controls | Normal Activity |

| 5 | Controls | Normal Activity |

| 9 | Controls | Normal Activity |

| 26 | Study | During Alcohol Use/Drug Effect |

| 30 | Study | Removal of Alcohol/Withdrawal |

| 31 | Study | Withdrawal |

Table 2.

Cosine curve parameter estimates and amplitude significance tests. (Period=24 Hours)

| Tau | Grp | N | Activity Reading | Mesor | Mesor (se) | Amp. | Amp. p-value | Acro. (deg.) | Acro (hrs) | R-square |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | 1,2,3 | 144 | Hz | 2158.54 | 49.06 | 2308.5 | <0.001 | −33.28 | 3.22 | 0.8870 |

| 4 | 48 | Hz | 1068.33 | 59.14 | 0998.2 | <0.001 | −30.49 | 3.03 | 0.7599 | |

| 5 | 48 | Hz | 1777.50 | 67.86 | 537.52 | <0.001 | −346.43 | 24.1 | 0.4108 | |

| 6 | 48 | Hz | 2559.58 | 80.50 | 386.65 | 0.0059 | −65.32 | 5.35 | 0.2040 | |

| 24 | 1,2,3 | 144 | Va1z | 279.03 | 10.26 | 262.61 | <0.001 | −9.21 | 1.61 | 0.6992 |

| 4 | 48 | Va1z | 164.38 | 9.43 | 167.76 | <0.001 | −8.64 | 1.58 | 0.7785 | |

| 5 | 48 | Va1z | 272.88 | 9.72 | 146.71 | < | −16.01 | 2.07 | 0.7166 | |

| 6 | 48 | Va1z | 385.88 | 11.78 | 88.74 | < | −39.34 | 3.62 | 0.3873 | |

| 24 | 1,2,3 | 144 | Va2z | 30.66 | 1.32 | 29.92 | < | −16.98 | 2.13 | 0.6468 |

| 4 | 48 | Va2z | 14.96 | 1.26 | 16.65 | < | −27.16 | 2.81 | 0.6608 | |

| 5 | 48 | Va2z | 41.83 | 1.35 | 09.05 | < | −304.33 | 21.29 | 0.3315 | |

| 6 | 48 | Va2z | 28.63 | 01.22 | 15.92 | < | −70.39 | 05.69 | 0.6528 |

Table 3.

F-tests of significance for difference between cosine curve parameter estimates.

| Animal Group 1 | Animal Group 2 | Ho: Equal Parameter | F-stat | Degree of Freedom | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 26 | Control | Mesor | 141.00 | (1,186) | <0.001 |

| Amplitude | 101.9 | (1,186) | <0.001 | ||

| Acrophase | 0.176 | (1,186) | 0.676 | ||

| Day 30 | Control | Mesor | 16.53 | (1,186) | <0.001 |

| Amplitude | 178.5 | (1,186) | <0.001 | ||

| Acrophase | 2.45 | (1,186) | 0.119 | ||

| Day 31 | Control | Mesor | 17.13 | (1,186) | <0.001 |

| Amplitude | 196.70 | (1,186) | <0.001 | ||

| Acrophase | 2.97 | (1,186) | 0.087 | ||

| Day 30 | Day 31 | Mesor | 55.18 | (1,90) | <0.001 |

| Amplitude | 1.03 | (1,90) | 0.314 | ||

| Acrophase | 6.57 | (1,90) | 0.012 | ||

| Day 26 | Day 30 | Mesor | 62.07 | (1,90) | <0.001 |

| Amplitude | 13.10 | (1,90) | <0.001 | ||

| Acrophase | 2.38 | (1,90) | 0.127 | ||

| Day 26 | Day 31 | Mesor | 222.9 | (1,90) | <0.001 |

| Amplitude | 18.74 | (1,90) | <0.001 | ||

| Acrophase | 4.42 | (1,90) | 0.038 | ||

| =========== | =========== | =========== | =========== | =========== | =========== |

| Day 26 | Control | Mesor | 37.81 | (1,186) | <0.001 |

| Amplitude | 12.95 | “ | <0.001 | ||

| Acrophase | 0.01 | 0.945 | |||

| Day 30 | Control | Mesor | 0.11 | (1,186) | 0.743 |

| Amplitude | 19.22 | “ | < | ||

| Acrophase | 0.52 | “ | 0.471 | ||

| Day 31 | Control | Mesor | 31.40 | (1,186) | < |

| Amplitude | 41.57 | “ | |||

| Acrophase | 3.54 | “ | 0.062 | ||

| Day 30 | Day 31 | Mesor | 54.82 | (1,90) | < |

| Amplitude | 7.21 | “ | 0.009 | ||

| Acrophase | 4.01 | “ | 0.048 | ||

| Day 26 | Day 30 | Mesor | 64.17 | (1,90) | |

| Amplitude | 1.20 | “ | 0.276 | ||

| Acrophase | 1.10 | “ | 0.298 | ||

| Day 26 | Day 31 | Mesor | 215.8 | (1,90) | |

| Amplitude | 13.72 | “ | |||

| Acrophase | 7.04 | “ | 0.008 | ||

| =========== | =========== | =========== | =========== | =========== | =========== |

| Day 26 | Control | Mesor | 42.78 | (1,186) | < |

| Amplitude | 15.26 | “ | < | ||

| Acrophase | 0.911 | “ | 0.241 | ||

| Day 30 | Control | Mesor | 21.34 | (1,186) | < |

| Amplitude | 37.26 | “ | < | ||

| Acrophase | 3.58 | “ | 0.060 | ||

| Day 31 | Control | Mesor | 0.72 | (1,186) | 0.400 |

| Amplitude | 17.07 | “ | < | ||

| Acrophase | 18.33 | “ | < | ||

| Day 30 | Day 31 | Mesor | 52.36 | (1,90) | < |

| Amplitude | 7.09 | “ | 0.009 | ||

| Acrophase | 01.21 | “ | 0.274 | ||

| Day 26 | Day 30 | Mesor | 211.5 | (1,90) | |

| Amplitude | 8.47 | “ | |||

| Acrophase | 4.40 | “ | 0.39 | ||

| Day 26 | Day 31 | Mesor | 60.64 | (1,90) | < |

| Amplitude | 0.09 | “ | 0.767 | ||

| Acrophase | 23.32 | “ | < |

Results

Control

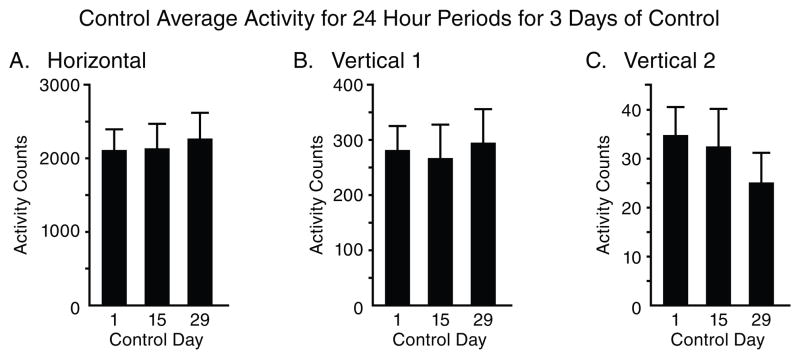

Fig. 1 summarizes the total locomotor activity for 24 hour periods for the 3 control days. The data demonstrates that the control group exhibits similar activity with the minor fluctuations during the days of control. The 24 hour total activity level in the control rats remains consistent during the control portion of the experiment for all three locomotor indices: horizontal, vertical 1, and vertical 2.

Figure 1.

The figure summarizes (N=8) the total 24 hour activity of three locomotor indices (A,B, and C) recorded from three randomized control days. The recordings were obtained from 31 consecutive non-stop recording days. The data shows that the control group exhibited similar levels of activities with minor non significant fluctuation.

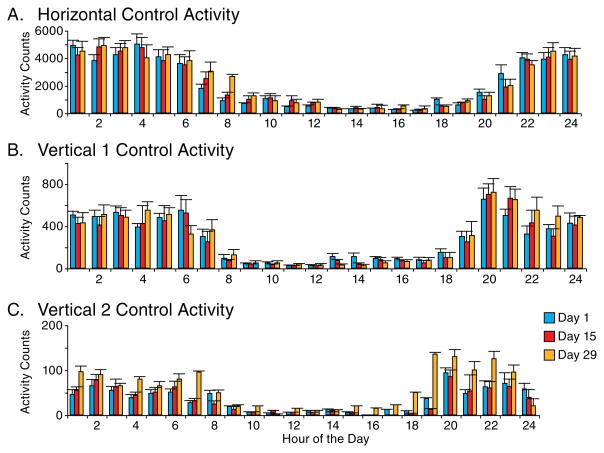

Fig. 2 summarizes the hourly horizontal, vertical 1, and vertical 2 locomotor activity, also during the control portion of the experiment. Days 1, 5, and 9 were arbitrarily chosen as representative of the daily pattern of activity in the rats. They display activity consistent with nocturnal behavior. Theses three days of control were also determined to be statistically similar using the cosine curve analysis (2). Therefore, the control days 1, 5, and 9 are grouped together for purposes of simplicity in demonstrating the data gathered. The horizontal activity of the control group shows an average (mesor) of 2158.54 beam crossings per hour during the 24 hour period, with an amplitude above and below that value of 2,308.51 and maximal activity approximately 3:15 AM. The mesor for the vertical activity level 1 (sitting posture) was 279.03 ± 262.61, with maximal activity close to 1:40 AM, and for the vertical activity level 2 (reaching posture) the mesor was 30.66 ± 29.92 beam crossings, with maximal activity close to 2:05 AM.

Figure 2.

The figure summarizes the hourly sum (N=8) of the rat described in figure 1 of the three locomotor indices (A,B, and C) evaluated. The hour’s histogram show the hourly activity pattern typical of nocturnal animals. The number under the column indicates the recording time. The hourly activity pattern on experimental day days 1,15, and 29 exhibit similar levels and patterns with minor non-significant fluctuation.

Experiment

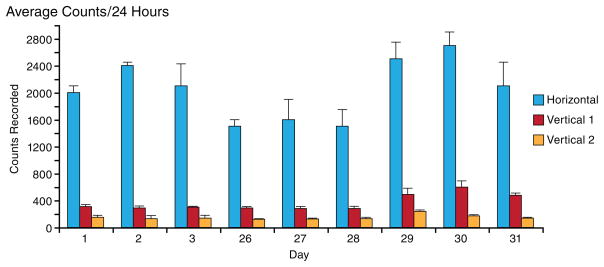

Fig. 3 shows the average counts for 24 hour periods during all phases of experimentation. Days 1–3 account for a control baseline. This control was previously established and is the control used for statistical comparison. The average counts for the days of alcohol treatment and those for the days of alcohol withdraw display statistical differences, not only one from the other, but also each from the control.

Figure 3.

The figure summarizes the total 24 hours of the three locomotor activity indices obtained on experimental days 1 to 3 (control), 26 to 28 the last three days of the alcohol consumption and the last three experimental day after abrupt alcohol cessation (experimental days 29 to 31)

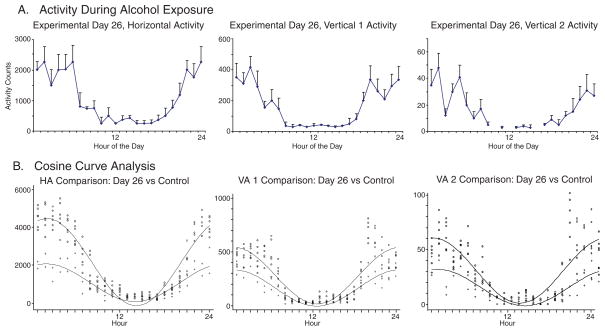

Alcohol Consumtion, Experimental Day 26

Fig. 4(a) shows the hourly activity recorded for Day 26, again arbitrarily chosen to represent the effects of alcohol usage. All levels of activity, horizontal, vertical 1, and vertical 2 display statistical difference during peak activity hours compared to that of the control as shown in Fig. 2(c). The activity recorded during the 12 hours of light, when the rats sleep, however, is similar to that of the control. The most notable difference is that the activity during the 12 hours of dark, when the rats are awake and is usually more depressed. More specifically, the horizontal beam crossings during this alcohol consumption phase showed a mesor of 1,068.33 ± 998.2 (p<0.001), for vertical 1 was 164.38 ± 167.76 (p<0.001), and for vertical 2 were 14.96 ± 16.65 (p<0.001). Also, the times of the maximum activity (acrophase) for each level of measurement did not significantly change.

Figure 4.

The figure shows the 24 hourly activity of the three locomotor indices (Fig. 4A) and the superimposed cosine curve analysis of the control day with experimental day 26 (Fig. 4B). Similar observations were obtained from experimental days 27 and 28.

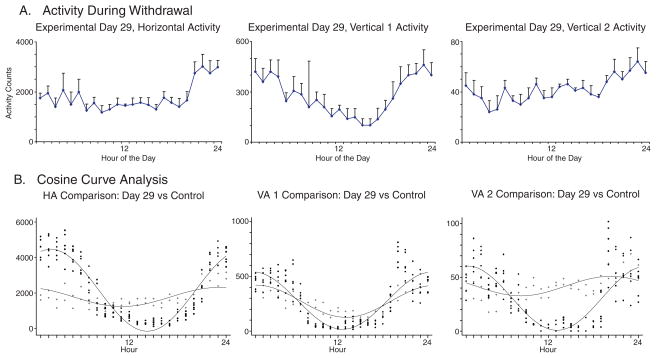

Alcohol Withdrawal, Experimental Days 29 and 30

Figs. 5 and 6 show the hourly activity recorded for Day 29 (Fig. 5(a)) and Day 30 (Fig. 6(a)), the first 2 days after alcohol consumption was discontinued. Day 29 shows a mesor for beam crossings for the horizontal and vertical 1 activity is increased from Day 26 by almost 70%, but remained below normal (p<0.001); and the vertical 2 activity increased by 170%, but also remaining below normal (p<0.001). Again, the times of maximal activity (acrophase) for the horizontal and vertical 1 levels of activity were not significantly different between alcohol usage, Day 26 and alcohol withdrawal, Day 29. However upon inspection of Figure 5(a) a dramatic, although non-significant (p=0.390) change in the timing of maximal vertical 2 level activity is indicated. The maximum activity for the alcohol usage (Day 26) is approximately 3 AM, while the withdrawal activity (Day 29) increases during daylight hours, reaching a maximum at close to 9 PM, thus demonstrating an altered circadian rhythm.

Figure 5.

The figure shows the 24 hourly activity of the three locomotor indices (Fig. 5A) and the superimposed cosine curve analysis of the control day with experimental day 29 the first day of abrupt alcohol cessation (Fig. 5B).

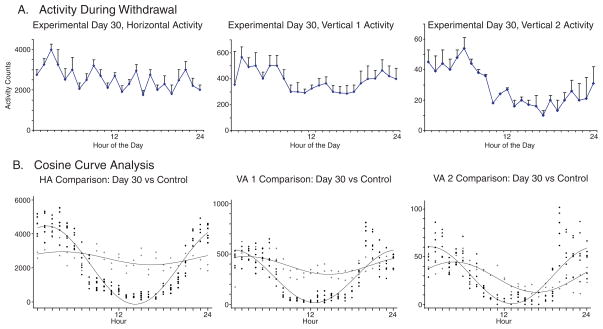

Figure 6.

The figure shows the 24 hourly activity of the three locomotor indices (Fig. 6A) and the superimpsoded cosine curve analysis of the control day with experimental day 30 the second day of abrupt alcohol cessation (Fig. 6B).

The second day of withdrawal, Day 30, indicates a tendency to return to normal activity during the period of darkness, but with persisent differences. For Day 30, there was an elevated horizontal activity mesor of 2559.58 beam crossings, significantly different from normal (p<0.001) with a significantly lower (p<0.001) amplitude of ± 386.65. The maximal activity time, 5:30 AM, returns to approximately normal (p=0.087). The mesor of vertical 1 activity, 385.88, on Day 30, was also elevated (p<0.001) while the amplitude remains significantly (p<0.001) reduced at 88.74 beam crossings, with maximal activity at 2:00 AM, again returning to normal (p=0.062). Vertical 2 activtiy mesor, 28.63, returns to normal (p=0.400), while the amplitude, 15.92 remains reduced (p<0.001), and the acrophase, 5:40 AM indicates a shift (p<0.001) toward daylight hours.

Discussion

The data displays a marked difference in the levels of activity between the control, the application of alcohol, and the withdrawal thereof. A decrease in the total activity of the rats was observed after 26 days of alcohol consumption, most of the decrease occurring during the 12 hours of dark phase, the time when the rats are awake. This depression of motor activity can be explained by alcohol’s depressive actions on the CNS (15,18,19,20,46). This alteration in the awake locomotor activity creates an alteration in the circadian activity pattern of the animal. In every axis, horizontal, vertical 1, and vertical 2, there were changes in the level of activity. Once the alcohol was removed, and blood alcohol concentrations began to drop, the rats increased their locomotor activity which can be interpreted as withdrawal behavior. This alteration in the circadian rhythm is apparent due to the significant change in the acrophase from 3 AM to 9 PM. The characteristic signs of withdrawal manifested in the data collected during the hourly recordings of activity are hyperactivity, hyperexcitability, and insomnia similar to other reports (6,13,18,19,20). Theses symptoms are notably the exact contraries to the effects during alcohol consumption, and agree with previous observations (6,8,15,18,19,20,40)

This, therein, begs the question: Does withdrawal from alcohol create the disturbance in circadian rhythms or does a disturbance in the circadian rhythm produce withdrawal-like effects? The data suggests that ethanol creates changes throughout the brain that have many effects that lead to dependence and subsequent withdrawal effects. These changes involve changes which alter the circadian rhythm. Furthermore, the data suggests that this modulation in circadian rhythm activity is then responsible for perpetuating the symptoms of withdrawal and that once the circadian rhythm activity is corrected, the signs of withdrawal can be reversed, similar to the idea that once the circadian rhythm in restored in a jet lagged traveler, their symptoms of jet lag fade away (41). This warrants further investigation.

Although no specific receptor for ethanol has been found, ethanol has been found to produce affects on numerous receptors throughout the body. Such receptors include serotonin (5-HT) (11,35) voltage gated calcium channels (17); receptors for the excitatory amino acid, glutamate (12,35); GABA neurotransmission (23,44); catecholamines such as norepinephrine and dopamine (39). Changes in each of these receptors are suspected in not only producing dependence on alcohol, but also in claiming responsibility for the withdrawal syndrome.

The relationship of 5-HT and ethanol self-administration has long been realized. It is agreed that increasing 5-HT neurotransmission will produce reductions in alcohol self-administration (32). It was reported that depletion of 5-HT in the brain slowed the rate of development of tolerance. Data has shown that ethanol withdrawal alters the function of 5-HT in the brain, suggesting that reduced 5-HT activity in the brain may be a secondary consequence of ethanol withdrawal. 5-HT, however, does not appear to play a role in the development of dependence on ethanol (11,32).

Serotonin seems to display a particular connection between circadian rhythms and withdrawal (35). In the rat, 5-HT levels are highest during the hours of light, and lowest during hours of darkness. The amplitude of the rhythm in 5-HT tissue concentration has been shown to be the largest in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) (20). Both in vivo (5,21,45) and in vitro (24,33) experiments have shown that pharmacological intervention with selective ligands for 5-HT receptors produces phase shifts and/or changes in amplitude of the measured rhythm. On the basis of these findings, it is clear that serotonergic innervation of the SCN plays an important part in modulating the activity and output of the circadian oscillator (22,25,35).

Furthermore, ethanol has been shown to upregulate long-lasting (L-type) calcium channels (14). L-type calcium channels are primarily found on dendrites and neuronal cell bodies in the brain (17). Activation of these channels mediate long lasting increases in cytosolic calcium that may be linked with second messenger functions of calcium in brain, which includes involvement in neurotransmitter release. Evidence further indicates that chronic ethanol administration may result in upregulation of these L-type calcium channels with increasing calcium influx and that the temporary maintenance of these changes are involved in the development of functional tolerance, dependence, and in the withdrawal syndrome (14,17,32).

Glutamate is the major excitatory neurotransmitter in the CNS (15). One of the primary receptors for glutamate is the NMDA receptor (12,15). Ethanol is a potent and selective inhibitor of the function of the NMDA receptor (32). Chronic ethanol usage results in an upregulation of the NMDA receptor function. This function of ethanol is thought to underlie the mechanism of ethanol tolerance and the symptoms of ethanol withdrawal, especially withdrawal seizures (12,32,35).

Ethanol also produces some of its effects by modulating the GABA receptor in the brain (23). GABA is an inhibitory neurotransmitter of which ethanol is believed to be an agonist. Ethanol has the effect of downregulating GABA receptors. Alcohol binding of the ligand produce a conformational change in the receptor and the control ion pore opens to allow the flow of ions. In some receptors the binding of the ligand produces a closed conformational state in spite of the continuing presence of the ligand. This state is called “desensitization” (tolerance). The delta subunit-containing GABAARS and tonic inhibition mediated by them appears to cause the sobriety impairing concentration of ethanol (27). The delta subunit-containing GABAARS considered by some as the “ethanol receptor” of the brain (10). The tonic inhibition mediated by these GABAARS has an equally high sensitivity to ethanol (49), suggesting that the delta subunit-containing GABAARS of the brain are the target for sobriety impairing concentration of ethanol (27). Specifically, some studies suggest that chronic ethanol application alters the GABAA receptor gene expression, which suggests a method of ethanol tolerance and withdrawal (32,34,44) as well as modulation of the circadian clock gene (23).

Chronic ethanol ingestion increases the activity of NE and decreases the activity of DA in the brain (39). Both of these systems are thought to be involved in the development of physical dependence on ethanol and in ethanol withdrawal; however data suggests that the ethanol induced alterations in DA activity and sensitizes the DA receptors, which may contribute more highly to certain signs of alcohol withdrawal (32). Acutely, dopaminergic neurons are resistant to the effects of alcohol, possibly mediating a reinforcing effect of ethanol in the short term (32,39).

Ethanol creates these neuromodulatory adaptations involving 5-HT, L-type calcium channels, glutamate, GABA, NE, and DA (23,32,35). These adaptations are proposed to account for not only the acute effects of alcohol intoxication, but also withdrawal. The effects involve an alteration of a gene, which then produces either an upregulation or downregulation of a gene product (3,31,32).

All of the above interpretations consider synaptic interaction. Recently, it was reported that neurons are able to communicate without synapses. They are able to send chemical messages by means of diffusion to target cells via the extracellular space (52). These observations led to the suggestion that in addition to synaptic chemical communication, there is another form of interaction among neurons (51). Moreover, in the CNS most of the drugs are modulators and their targets are non-synaptic receptors, transporters, enzymes, and ion channels. These non-synaptic receptors are more affected because they outnumber synaptic, the synaptic ones and they are more sensitive to fine modulation of ambient in the extracellular space compared with receptors in the synapses (52), the non-synaptic function are thought to be responsible for the modulation, tuning and alteration of many physiological processes such as the level of arousal and may be also circadian activity patterns shown in this study following chronic alcohol consumption. Furthermore, studies have shown (4,25,37,38) that both chronic ethanol intake and ethanol withdrawal may be associated with changes in a fundamental parameter of the circadian pacemaker (3,31). The results of this study further supports the evidence that ethanol alters the circadian rhythm.

The mammalian clock system contains a master clock located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) (23,34). In mice, the system includes three Period (Per) genes (Per 1, Per 2, Per 3), two Cryptochrome genes, the Clock gene, and the gene encoding brain-muscle Arnt-like protein 1 (30,42). Recent studies have shown that ethanol consumption does alter the circadian expression patterns of Per genes in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (42). Evidence suggests that it is this ability of ethanol to alter genetic expression involved in the circadian rhythm that is paramount in discovering the causal relationship to withdrawal. The disruption in circadian rhythms by alteration of the genetic controllers, leads to the behavioral effects of withdrawal.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Stacy Norrell, Department of Neurobiology and Anatomy.

Cruz Reyes-Vasquez, Department of Neurobiology and Anatomy.

Keith Burau, School of Public Health, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

Nachum Dafny, Department of Neurobiology and Anatomy.

References

- 1.Algahim MF, Yang PB, Wilcox VT, Burau KD, Swann AC, Dafny N. Prolonged methylphenidate treatment alters the behavioral diurnal activity pattern of adult male Sprague-Dawley rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009;92:93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bingham C, Arbogast B, Guillaume GC, Lee JK, Halberg F. Inferential statistical methods for estimating and comparing cosinor parameters. Chronobiologia. 1982;9:397–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Comasco E, Nordquist N, Göktürk C, Aslund C, Hallman J, Oreland L, Nilsson KW. The clock gene PER2 and sleep problems: association with alcohol consumption among Swedish adolescents. Ups J Med Sci. 2010;115:41–8. doi: 10.3109/03009731003597127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dwyer SM, Rosenwasser AM. Neonatal clomipramine treatment, alcohol intake and circadian rhythms in rats. Psychopharmacology. 1998;138:176–183. doi: 10.1007/s002130050660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edgar DM, Miller JD, Prosser RA, Dean RR, Dement WC. Serotonin and the mammalian circadian system: II. Phase shifting rat behavioral rhythms with serotonergic agents. J Biol Rhythms. 1993;8:17–31. doi: 10.1177/074873049300800102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freund G. Alcohol, barbiturate, and bromide withdrawal syndrome in mice. In: Mello NK, Mendelson JH, editors. Recent Advances in Studies of Alcoholism. Washington: U.S. Govt. Printing Office; 1971. pp. 453–471. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaytan O, Swann AC, Dafny N. Disruption of sensitization to methylphenidate by a single administration of MK-801. Life Sci. 2002;70:2271–2285. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(02)01470-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldstein DB, Pal N. Alcohol Dependence Produced in mice by inhalation of ethanol: grading the withdrawal reaction. Science. 1971;172:288–290. doi: 10.1126/science.172.3980.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gottesfeld Z, Maier M, Mailman D, Lai M, Weisbrodt NW. Splenic sympathetic response to endotoxin is blunted in the fetal alcohol-exposed rat: role of nitric oxide. Alcohol. 1998;16(1):19–24. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(98)00009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanchar HJ, Wallner M, Olsen RW. Alcohol effects on gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptors: are extrasynaptic receptors the answer? Life Sci. 2004;76:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higgins GA, Lê AD, Sellers EM. 5-HT Mediation of Alcohol Self-Administration, Tolerance, and Dependence: Preclinical Studies. In: Kranzler Henry R., editor. The Pharmacology of Alcohol Abuse. Vol. 114. Springer-Verlag; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffman PL. Effects of Alcohol on Excitatory Amino Acid Receptor Function. In: Kranzler Henry R., editor. The Pharmacology of Alcohol Abuse. Vol. 114. Springer-Verlag; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoshaw BA, Lewis MJ. Behavioral sensitization to ethanol in rats: evidence from the Sprague-Dawley strain. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2001;68:685–90. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00489-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katsura M, et al. Increase in Expression of α1 and α2/δ1 Subunits of L-Type High Voltage-Gated Calcium Channels After Sustained Ethanol Exposure in Cerebral Cortical Neurons. Journal of Pharmacological Sciences. 2006;102:221–230. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fp0060781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katzung BG. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology. 9. McGraw-Hill Companies; 2004. pp. 367–378. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee MJ, Yang PB, Wilcox VT, Burau KD, Swann AC, Dafny N. Does repetitive Ritalin injection produce long-term effects on SD female adolescent rats? Neuropharmacology. 2009;57:201–207. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leslie SW. Effects of Ethanol on Voltage-Dependent Calcium Channel Function. In: Kranzler Henry R., editor. The Pharmacology of Alcohol Abuse. Vol. 114. Springer-Verlag; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Majchrowicz E. Induction of physical dependence on alcohol and the associated metabolic and behavioral changes in rats. Pharmacologist. 1973;15:159. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Majchrowicz E. Spectrum and continuum of ethanol intoxication and withdrawal in rats. Pharmacologist. 1974;16:304. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Majchrowicz E. Induction of physical dependence upon ethanol and the associated behavioral changes in rats. Psychopharmacologia. 1975;43:245–254. doi: 10.1007/BF00429258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin KF, Marsden CA. In vivo diurnal variations of 5-HT release in hypothalamic nuclei. In: Redfern PH, Campbell IC, Davies JA, Martin KF, editors. Circadian Rhythms in the Central Nervous System. Macmillan; London: 1985. pp. 81–94. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin KF, Redfern PH. 5-Hydroxytryptamine and Noradrenaline Synthesis, Release and Metabolism in the Central Nervous System: Cricadian Rhythms and Control Mecanisms. In: Redfern PH, Lemmer B, editors. Physiology and Pharmacology of Biological Rhythms. Vol. 125. Springer-Verlag; 1997. pp. 157–176. [Google Scholar]

- 23.McElroy B, Zakaria A, Glass JD, Prosser RA. Ethanol modulates mammalian circadian clock phase resetting through extrasynaptic GABA receptor activation. Neuroscience. 2009;164:842–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Medanic M, Gillette MS. Serotonin regulates the phase of the rat suprachiasmatic pacemaker in vitro only during the subjective day. Journal of Physiology. 1992;450:629–642. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mistlberger RE. Illuminating Serotonergic Gateways for Strong Resetting of the Mammalian Circadian Clock. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integretive, and Comparative Physiology. 2006;291:R177–R179. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00158.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mistlberger RE, Nadeau J. Ethanol and circadian rhythms in the Syrian Hamster: effect on entrained phase, reentrainment rate, and period. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1992;43:159–165. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(92)90652-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mody I. Extrasynaptic GABAA receptors in the crosshairs of hormones and ethanol. Neurochemistry International. 2008;52:60–64. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moore-Ede MC. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparitive Physiology. Vol. 250. American Physiological Society; 1986. Physiology of the circadian timing system: predictive versus reactive homeostasis; pp. R737–R752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moore RY. Mechanisms and Applications. Elsevier Science B.V; 1998. Entrainment Pathways in the Mammalian Brain. Biological Clocks. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morse D, Sassone-Corsi P. Time after time: inputs to and outputs from the mammalian circadian oscillators. Trends in Neuroscience. 2002;25:632–637. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(02)02274-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perreau-Lenz S, Zghoul T, de Fonseca FR, Spanagel R, Bilbao A. Circadian regulation of central ethanol sensitivity by the mPer2 gene. Addict Biol. 2009;14:253–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2009.00165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Petrakis IL. A Rational Approach to the Pharmacotherapy of Alcohol Dependence. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2006;26:S3–S12. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000248602.68607.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prosser RA, Dean RR, Edgar DM, Heller HC, Miller JD. Serotonin and the mammalian circadian system: I. In vitro phase shifts by serotonergic agonists and antagonists. J Biol Rhythms. 1993;8:1–16. doi: 10.1177/074873049300800101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prosser RA, Glass JD. The mammalian circadian clock exhibits acute tolerance to ethanol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:2088–2093. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01048.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prosser RA, Mangrum CA, Glass JD. Acute ethanol modulates glutamatergic and serotonergic phase shifts of the mouse circadian clock in vitro. Neuroscience. 2008;152:837–848. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.12.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reppert SM, Weaver DR. Molecular Analysis of Mammalian Circadian Rhythms. Annual Review of Physiology. 2001;63:647–676. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.647. Annual Reviews. 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosenwasser AM. Effects of ethanol and ethanol preference on the mammalian circadian pacemaker: behavioral characterization. Alcohol Clinical Exp Res. 2004;28:136. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosenwasser AM, Fectuau ME, Logan RW. Effects of ethanol intake and ethanol withdrawal on free-running circadian activity rhythms in rats. Physiol Behav. 2005;84:537–542. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Samson HA, Hoffman PL. Involvement of CNS Catecholamines in Alcohol Self-Administration, Tolerance, and Dependence: Preclinical Studies. In: Kranzler Henry R., editor. The Pharmacology of Alcohol Abuse. Vol. 114. Springer-Verlag; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seggio JA, Fixaris MC, Reed JD, Logan RW, Rosenwasser AM. Chronic ethanol intake alters circadian phase shifting and free-running period in mice. J Biol Rhythms. 2009;24:304–12. doi: 10.1177/0748730409338449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smolensky M, Lamberg L. The Body Clock: Guide to Better Health. Henry Holt and Company, LLC; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spanagel R, Rosenwasser RA, Schumann Gunter, Sarkar Dipak K. Alcohol Consumption and the Body’s Biological Clock. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research. Research Society on Alcoholism. 2005;29:1550–1557. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000175074.70807.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stubbs CD, Rubin E. Alcohol, Cell Membranes, and Signal Transduction in Brain. Plenum Press; 1993. Molecular Mechanisms of Ethanol and Anesthetic Actions: Lipid- and Protien-Based Theories. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ticku MK, Mehta AK. Effects of Alcohol on GABA-Medited Neurotransmission. In: Kranzler Henry R., editor. The Pharmacology of Alcohol Abuse. Vol. 114. Springer-Verlag; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tominaga K, Shibata S, Ueki S, Watanabe S. Effects of 5-HT 1A receptor agonists on the circadian rhythm of wheel-running hamsters. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1992;214:79–84. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90099-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Trujillo JL, Roberts AJ, Gorman MR. Circadian timing of ethanol exposure exerts enduring effects on subsequent ad libitum consumption in C57 mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:1286–1293. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00954.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Uz T, Akhisaroglu M, Ahmed R, Manev H. The pineal gland is critical for circadian Period 1 expression in the striatum and for circadian cocaine sensitization in mice. The Psychiatric Institute; 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van Dongen HPA, Kerkhof GA, Dinges DF. Molecular Biology of Circadian Rhythms. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2004. Human Circadian Rhythms. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wei W, Faria LC, Mody I. Low ethanol concentrations selectively augment the tonic inhibition mediated by delta subunit-containing GABAA receptors in hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24:8379–8382. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2040-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yoshimoto K, McBride WJ, Lumeng L, Li TK. Alcohol. Vol. 9. Pergamon Press; 1991. Alcohol Stimulates the Release of Dopamine and Serotonin in the Nucleus Accumbens; pp. 17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vizi ES. Pharmacological and Clinical Aspects. John Wiley and Sons, Chichester; New York: 1984. Non-synaptic interactions between neurons: Modulation of neurochemical transmission. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vizi ES, Fekete A, Karoly R, Mike A. Non-synaptic receptors and transporters involved in brain functions and targets of drug treatment. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:785–809. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00624.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]