Abstract

MAPK phosphatase-1 (DUSP1/MKP-1) is a mitogen and stress-inducible dual specificity protein phosphatase, which can inactivate all three major classes of MAPK in mammalian cells. DUSP1/MKP-1 is implicated in cellular protection against a variety of genotoxic insults including hydrogen peroxide, ionizing radiation, and cisplatin, but its role in the interplay between different MAPK pathways in determining cell death and survival is not fully understood. We have used pharmacological and genetic tools to demonstrate that DUSP1/MKP-1 is an essential non-redundant regulator of UV-induced cell death in mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs). The induction of DUSP1/MKP-1 mRNA and protein in response to UV radiation is mediated by activation of the p38α but not the JNK1 or JNK2 MAPK pathways. Furthermore, we identify MSK1 and -2 and their downstream effectors cAMP-response element-binding protein/ATF1 as mediators of UV-induced p38α-dependent DUSP1/MKP-1 transcription. Dusp1/Mkp-1 null MEFs display increased signaling through both the p38α and JNK MAPK pathways and are acutely sensitive to UV-induced apoptosis. This lethality is rescued by the reintroduction of wild-type DUSP1/MKP-1 and by a mutant of DUSP1/MKP-1, which is unable to bind to either p38α or ERK1/2, but retains full activity toward JNK. Importantly, whereas small interfering RNA-mediated knockdown of DUSP1/MKP-1 sensitizes wild-type MEFs to UV radiation, DUSP1/MKP-1 knockdown in MEFS lacking JNK1 and -2 does not result in increased cell death. Our results demonstrate that cross-talk between the p38α and JNK pathways mediated by induction of DUSP1/MKP-1 regulates the cellular response to UV radiation.

Keywords: Apoptosis, DNA Damage, Dual Specificity Phosphoprotein Phosphatase, JNK, MAP Kinases (MAPKs), p38 MAPK, Signal Transduction, DUSP1, MKP-1

Introduction

Dual specificity mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatases (DUSPs or MKPs)2 act in direct opposition to dual specificity MAPK kinases (MKKs or MEKs) by dephosphorylating and inactivating MAPKs, thus regulating the physiological outcome of signaling (1). The MKPs comprise a family of 10 enzymes, each having distinct properties in terms of transcriptional regulation, subcellular localization, and substrate specificity (2). The inducible, nuclear phosphatase DUSP1/MKP-1 was the first of this family of enzymes to be discovered. Although first characterized as an ERK1 and -2 phosphatase in vitro, it was subsequently demonstrated to have activity toward p38 and JNK MAPKs and to be capable of inactivating all three classes of MAPK in vivo (3, 4). This broad substrate selectivity is governed by the ability of DUSP1/MKP-1 to form physical complexes with ERK, p38, and JNK MAPKs. Complex formation is also accompanied by catalytic activation of DUSP1/MKP-1 in vitro (5).

Recent studies of mice lacking DUSP1/MKP-1 have confirmed that the inactivation of multiple MAPK pathways by DUSP1/MKP-1 plays a key role in a wide variety of physiological settings in vivo. Thus, Dusp1/Mkp-1−/− mice display abnormalities in the innate immune response, T-cell activation and function, and metabolic homeostasis (6–10). At the cellular level, the ability of DUSP1/MKP-1 to regulate the activities of p38 and JNK signaling have been implicated in the responses to a wide variety of stress conditions, and mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) lacking DUSP1/MKP-1 are sensitive to cisplatin, hydrogen peroxide, anisomycin, and ionizing radiation (11–14).

Despite these advances, the relationships between the MAPK pathways involved in the inducible expression of DUSP1/MKP-1 and those that regulate cell survival or cell death are less clear. For instance, both p38 and JNK have been implicated in the transcriptional induction of DUSP1/MKP-1 in response to bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS), whereas the ERK pathway is able to regulate the induction of DUSP1/MKP-1 by cisplatin (15–17). Enhanced JNK activation has been proposed to mediate cell death in Dusp1/Mkp-1−/− MEFs exposed to cisplatin, whereas inhibition of the p38 pathway is reported to prevent cell death following anisomycin treatment and serum starvation (13, 14). Some of this complexity may be due to agonist or cell type differences, but may also be due to an over-reliance on the use of chemical inhibitors of MAPK signaling, with attendant problems of drug potency and/or specificity.

Here we have used a combination of genetic and pharmacological tools to explore the involvement of MAPK signaling in the transcriptional induction of DUSP1/MKP-1 in response to UV radiation, and the subsequent effect of this induction on UV-induced cell death. These tools include MEFs in which defined MAPKs have been deleted as well as cells lacking key downstream effectors and regulators of MAPK signaling, including DUSP1/MKP-1 itself. We demonstrate definitively that the induction of DUSP1/MKP-1 transcription by UV radiation (as well as cisplatin and oxidative stress) opposes apoptosis, and is dependent on signaling via p38α. This involves downstream effectors of p38 signaling, including the MSK1 and -2 protein kinases and transcription factors CREB/ATF1. Interestingly, neither JNK1 nor -2 play any role in mediating DUSP1/MKP-1 expression in response to these stresses. In contrast, UV radiation-induced apoptosis in cells lacking DUSP1/MKP-1 is mediated by JNK signaling alone. Our findings highlight a mechanism in which expression of DUSP1/MKP-1 mediates cross-talk between the p38 and JNK pathways to regulate the cellular response to UV and other DNA damaging agents.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

The inhibitor SB203580 was purchased from Calbiochem. Actinomycin D was from Sigma. Antibodies against phospho-ERK1/2, ERK1/2, phospho-p38, p38, phospho-JNK1/2, JNK, MSK1, phospho-CREB/ATF1, phospho-Jun, Jun, phospho-MK2, MK2, and caspase-3 were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Antibodies against DUSP1/MKP-1 and Tubulin were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Mouse anti-poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase antibody was purchased from AbD Serotec. Cisplatin and hydrogen peroxide were from Sigma. Tumor necrosis factor α was from R&D Systems. Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was obtained from Invitrogen. Cells were irradiated with defined doses of UV (254 nm) using a Stratalinker (Stratagene).

Generation of Immortalized Mouse Embryo Fibroblasts

Primary MEFs were isolated from 15- to 16-day-old embryos generated by crossing Dusp1/Mkp-1+/− (18) mice. Embryos were genotyped by PCR, using two separate reactions with the primer pair 5′-CAGGTACTGTGTGTCGGTGGTGCTAATG-3′ and 5′-CTATATCCTCCTGGCACAATCCTCCTAG-3′ for the wild-type allele or 5′-AAATGTGTCAGTTTCATAGCCTGAAGACG-3′ and 5′-CTATATCCTCCTGGCACAATCCTCCTAG-3′ for the mutant allele. Head and internal organs were removed on a Petri dish in phosphate-buffered saline and the trunk was dissected in 10 ml of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 0.05% trypsin (Invitrogen) with fine scissors. Following incubation at 37 °C for 10 min, the solution was pipetted 5 times with a 20-ml glass pipette. This was repeated with 10- and 5-ml glass pipettes with 10-min incubations at 37 °C in between before trypsinization was terminated by adding 5 ml of FBS. Cells were then transferred into a Falcon tube and incubated for 2 min at 4 °C to allow solid tissue to sediment. The supernatant was then transferred into a new tube through a 70-mm cell strainer (Falcon). Following centrifugation, the pellet was washed once with complete medium (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin (100 units/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml)). Cells were counted and plated at 10 × 106 cells per 15-cm plate. The next day, the medium was changed and the cells were cultured until they reached confluency. The cells were subcultured at a density of 5–10 × 106 cells per 15-cm plate every 3 days. This process was repeated until cells reached crisis and became established cell lines.

Cell Culture and Transfections

Immortalized MEFs were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin (100 units/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). FLAG-tagged p38α, both wild-type and p38α T180A/Y182F (AGF), were expressed from pcDNA3 and pCMV, respectively (19). A CREB was expressed from the pRC vector (20), whereas Myc-tagged DUSP1/MKP-1 and kinase interaction motif mutant DUSP1/MKP-1 were expressed from pSG5. Transfections were carried out in 60-mm dishes (Iwaki) using Lipofectamine LTX (Invitrogen) and Plus reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions. Control siRNA oligos and siRNA oligos (Ambion) targeting DUSP1, MSK1, and MSK2 (100 pmol) were transfected using Lipofectamine RNAi Max (Invitrogen).

Generation of Stable Cell Lines Containing a DUSP1/MKP-1 Luciferase Reporter

A 3-kb fragment containing the human proximal DUSP1 promoter was excised from pGL3-MKP-1-luc (22) using NcoI and blunt end ligated into the EcoRV site of the vector pGL4.28hyg (Promega) to produce pGL4.28-MKP-1-luc. Immortalized MEFs were transfected with pGL4.28-MKP-1-luc, using Lipofectamine LTX, and subjected to three rounds of selection using hygromycin (100 μg/ml, Sigma) before basal and UV-induced luciferase activities were determined. Cells were routinely cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing hygromycin at a concentration of 100 μg/ml.

SDS-PAGE and Western Blotting

Cells were lysed in MKK lysis buffer (0.27 m sucrose, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm EGTA, 10 mm Tris, 1% Triton-X) containing protease inhibitors (Roche Applied Science) and phosphatase inhibitors (sodium fluoride, sodium β-glycerophosphate, and sodium orthovanadate). Gel electrophoresis was performed using the NuPAGE system (4–12% BisTris gels, Invitrogen). Western blotting was performed as described previously (21).

Flow Cytometry

Adherent cells were collected via trypsinization and combined with non-adherent cells. These were pelleted and fixed in 70% ethanol before treatment with RNase A (50 μg/ml) and staining with propidium iodide (100 μg/ml). Flow cytometry was carried out on a BD Bioscience FACscan machine, and analysis was performed using CellQuest software. Apoptotic cells were assumed to have sub-G1 DNA content, and the result was expressed as a percentage of total cells counted.

Survival Assays

MTS assays were carried out in 24-well plates using the One Solution CellTiter kit from Promega according to the manufacturer's instructions. Results were expressed as a percentage of untreated control values.

Quantitative Real Time RT-PCR

RNA was precipitated in ethanol, then isolated using RNeasy purification kits (Qiagen). cDNA was generated using reverse transcription reagents (Applied Biosystems). TaqMan quantitative RT-PCR was carried out as described in Ref. 21 on an ABI Prism 7700 machine, and analyzed using Sequence Detector software. All probes were pre-designed and obtained from Applied Biosystems. The following primer/probe sets were used: β-actin, DUSP1, DUSP2, DUSP4, DUSP5, DUSP6, DUSP7, DUSP8, DUSP9, DUSP10, DUSP16, and c-Fos. Sample data were normalized to β-actin.

Luciferase Assays

Cells were transfected in 24-well plates with a luciferase reporter construct consisting of a 3-kb fragment of the human Dusp1/Mkp-1 promoter cloned into the pGL3 vector (22). Empty pGL3 was used as a negative control, and pRL-TK (Renilla luciferase driven by the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase promoter) was used to normalize for transfection efficiency. The NF-κB (nuclear factor κB) reporter construct 3× κB-ConA (concanavalin A)-luciferase and the Rous sarcoma virus expression vectors encoding the dominant-negative IκBα (inhibitor of NF-κB) Mad3 and β-galactosidase were kindly provided by Dr. Neil Perkins (University of Newcastle) (23). The dual luciferase reporter assay (Promega) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions, and data collection was performed on an Orion II microplate luminometer (Berthold Systems).

RESULTS

Regulation of DUSP1/MKP-1 mRNA and Protein Levels by UV Radiation

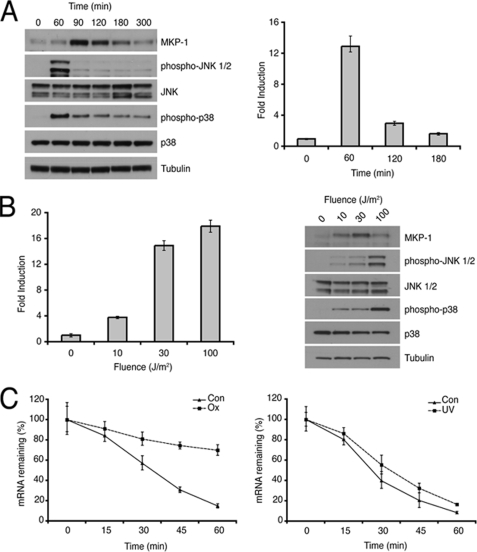

DUSP1/MKP-1 mRNA is inducible by a variety of cellular insults, including hydrogen peroxide, cisplatin, and short-wavelength UV radiation. We detected induction of both DUSP1/MKP-1 mRNA and protein in MEFs (both primary and immortal), HeLa, U2OS, and MCF7 cells 1 h after UV irradiation (data not shown). We next assessed the time course of DUSP1/MKP-1 mRNA and protein induction in UV-irradiated immortalized MEFs. We observed robust activation of p38α and JNK MAPKs, and induction of DUSP1/MKP-1 mRNA and protein in these cells (Fig. 1A). Importantly, the appearance of MKP-1 protein correlated temporally with the inactivation of both JNK and p38α.

FIGURE 1.

Induction of DUSP1/MKP-1 by UV radiation. A, wild-type MEFs were either mock irradiated or exposed to 30 J/m2 UV and then incubated at 37 °C for the indicated times. Cells were then lysed, and proteins analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using the indicated antibodies (left). DUSP1/MKP-1 mRNA levels were also determined using quantitative RT-PCR (right). B, wild-type MEFs were exposed to 0, 10, 30, or 100 J/m2 UV and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. Cells were then lysed, and DUSP1/MKP-1 mRNA levels were determined using quantitative RT-PCR (left). Proteins were also analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using the indicated antibodies (right). C, wild-type MEFs were either treated with 300 μm H2O2 (Ox) for 3 h or exposed to 30 J/m2 UV (UV) and incubated for 1 h, before addition of 2 μg/ml of actinomycin D. Cells were then lysed at the indicated times, and DUSP1/MKP-1 mRNA levels were determined using quantitative RT-PCR. Experiments were performed three times, each with triplicate determinations, and mean values with associated errors are shown (mean ± S.E.).

Recently, DUSP1/MKP-1 mRNA has been shown to be stabilized by oxidative stress-induced binding of RNA-binding proteins HuR and NF90 (24). In agreement with Kuwano et al. (24) we find that exposure of MEFs to hydrogen peroxide causes a significant increase in DUSP1/MKP-1 mRNA stability. In contrast, the stability of DUSP1/MKP-1 mRNA in UV-irradiated cells is unchanged (Fig. 1C). This suggests that increased DUSP1 transcription results in the induction of DUSP1/MKP-1 mRNA by UV. Indeed, we observe that the induction of DUSP1/MKP-1 protein by UV radiation is abolished by the transcription inhibitor actinomycin D (supplemental Fig. S1). DUSP1/MKP-1 mRNA and protein levels increase in a UV dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1B). However, at high UV fluence (100 J/m2), DUSP1/MKP-1 protein levels actually decline and this correlates with increased phosphorylation of both p38α and JNK (Fig. 1B). Our data suggests that low fluences of UV leads to increased transcription of the DUSP1/MKP-1 gene and to subsequent dephosphorylation of both p38α and JNK MAPKs. However, this mechanism is disrupted at high UV fluences, probably as a result of UV-mediated inhibition of DUSP1/MKP-1 translation (25).

The Induction of DUSP1/MKP-1 mRNA and Protein in UV-irradiated Cells Is Mediated by p38α

Although signaling through the MAPK pathways has been implicated in transcriptional regulation of DUSP1/MKP-1 in response to stress, it is unclear which pathways and downstream effectors are involved. For example, the classical ERK MAPK is reported to mediate induction of DUSP1/MKP-1 in response to cisplatin (12, 15), whereas ERK, p38α, and JNK have been implicated in DUSP1/MKP-1 induction by bacterial LPS, hydrogen peroxide, and sodium arsenite (16, 17, 22, 26, 27). In addition, the DUSP1/MKP-1 gene is reported to be a target for a number of MAPK-regulated transcription factors, including p53, NF-κB, and ATF2 and -7, and to be down-regulated in cells lacking c-Fos (28–31).

Data implicating MAPK signaling in DUSP1/MKP-1 induction has been obtained using pharmacological inhibitors where drug specificity is questionable, particularly in the case of inhibition of JNK signaling by SP600125 (32). To overcome these limitations, we have used MEFs derived from wild-type mice and animals lacking either p38α (33) or both major isoforms of JNK (JNK1 and JNK2) (34).

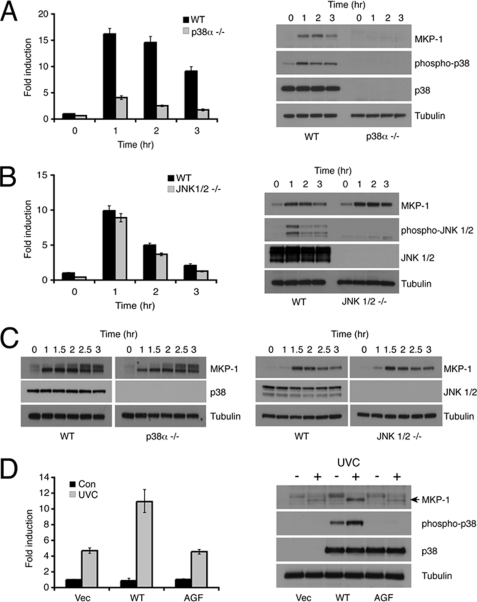

Deletion of p38α reduces the level of UV-inducible DUSP1/MKP-1 mRNA by ∼75%, and DUSP1/MKP-1 protein is almost undetectable in UV-irradiated p38α−/− MEFs (Fig. 2A). In contrast, loss of both JNK1 and JNK2 has no significant effect on the induction of either DUSP1/MKP-1 mRNA or protein by UV (Fig. 2B). Loss of either p38α or JNK1/2 does not affect inducible expression of DUSP1/MKP-1 in response to non-stress stimuli, as the DUSP1/MKP-1 protein is induced normally in response to serum stimulation (Fig. 2C). The greatly reduced expression of DUSP1/MKP-1 in p38α−/− MEFs is not a nonspecific effect of gene loss, as UV inducible expression of both DUSP1/MKP-1 mRNA and protein is rescued in these cells by re-expression of wild-type p38α, but not by a mutant in which the phosphoacceptor sites within the activation loop of the kinase have been substituted by non-phosphorylable residues (Fig. 2D).

FIGURE 2.

DUSP1/MKP-1 induction by UV is mediated by p38α. A, wild-type (WT) or p38α−/− MEFs were either mock irradiated or exposed to 30 J/m2 UV and then incubated at 37 °C for the indicated times. Cells were then lysed, and DUSP1/MKP-1 mRNA levels were determined using quantitative RT-PCR (left). Proteins were also analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using the indicated antibodies (right). B, wild-type (WT) or Jnk1/2−/− MEFs were either mock irradiated or exposed to 30 J/m2 UV and then incubated at 37 °C for the indicated times. Cells were then lysed, and DUSP1/MKP-1 mRNA levels were determined using quantitative RT-PCR (left). Proteins were also analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using the indicated antibodies (right). C, wild-type, p38α−/−, or Jnk1/2−/− MEFs were starved for 16 h in medium containing 0.5% FBS, then stimulated with 15% FBS for the indicated times. Cells were then lysed, and proteins analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using the indicated antibodies. D, p38α−/− MEFs were transfected with either empty vector, or expression vectors (Vec) encoding either wild-type p38α or a non-activable (AGF) mutant of p38α. Cells were mock irradiated or exposed to 30 J/m2 UV and then incubated at 37 °C for 1 h before lysis. DUSP1/MKP-1 mRNA levels were determined using quantitative RT-PCR (left). Proteins were also analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using the indicated antibodies (right). Experiments were performed three times, each in triplicate, and mean values with associated errors are shown (mean ± S.E.).

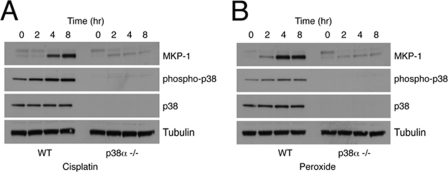

Finally, we also examined the involvement of p38α and JNK signaling in the induction of DUSP1/MKP-1 by both cisplatin and hydrogen peroxide. In both cases, loss of p38α greatly reduced the induction of DUSP1/MKP-1 mRNA and protein (Fig. 3, A and B), whereas loss of JNK1 and -2 had no significant effect (data not shown). We conclude that signaling through the p38α MAPK pathway mediates the induction of DUSP1/MKP-1 mRNA and protein in response to UV radiation, cisplatin, and hydrogen peroxide.

FIGURE 3.

DUSP1/MKP-1 induction by both cisplatin and oxidative stress is mediated by p38α. A, wild-type (WT) or p38α−/− MEFs were treated with 100 μm cisplatin for the indicated times. B, wild-type or p38α−/− MEFs were treated with 300 μm hydrogen peroxide for the indicated times. Cells were then lysed, and proteins analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using the indicated antibodies. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

UV-induced Expression of DUSP1/MKP-1 Is Mediated by MSK1 and -2

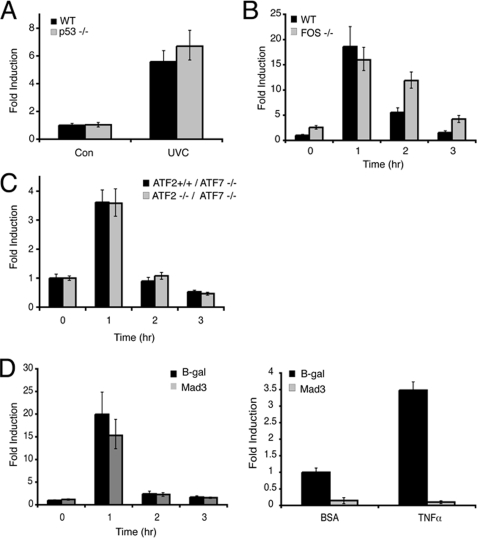

Having established that p38α activation is critical for the stress-responsive regulation of DUSP1/MKP-1, we next addressed a number of possible downstream effectors of p38α activity. The p53 tumor suppressor has been implicated in mediating DUSP1/MKP-1 transcription (28, 29), and p53 is a well characterized target of p38α MAPK in cells exposed to genotoxic stress (35, 36). We utilized HCT116 colon cancer cells and their isogenic p53-null derivatives (37) to study the p53 dependence of UV-induced DUSP1/MKP-1 mRNA expression. DUSP1/MKP-1 mRNA is robustly induced by UV radiation in HCT116 cells irrespective of p53 status (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, this induction is inhibited by SB203580, a specific inhibitor of p38α and -β (data not shown). This observation, coupled with the fact that we observe induction of DUSP1/MKP-1 mRNA and protein in MEFs where the immortalization process is accompanied by loss of the p53 or p19ARF tumor suppressors (38), indicates that p53 function is not essential for UV-induced expression of DUSP1/MKP-1.

FIGURE 4.

DUSP1/MKP-1 induction by UV is independent of p53, c-Fos, ATF2, and NF-κB. A, HCT116 p53+/+, and p53−/− cells were either mock irradiated or exposed to 100 J/m2 UV and then incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. B, wild-type (WT) and c-Fos−/− MEFs were either mock irradiated or exposed to 30 J/m2 UV and then incubated at 37 °C for the indicated times. C, Atf7−/−/Atf2+/+ and Atf7−/−/Atf2−/− MEFs were either mock irradiated or exposed to 30 J/m2 UV and then incubated at 37 °C for the indicated times. D, wild-type MEFs were transfected with either empty vector, or an expression vector encoding Mad3. After 24 h, cells were exposed to 30 J/m2 UV and then incubated at 37 °C for the indicated times. DUSP1/MKP-1 mRNA levels were assessed by quantitative RT-PCR (left). Wild-type MEFs were cotransfected with the NF-κB reporter construct 3xκB-ConA-luc and either an empty vector or an expression vector encoding Mad3. Renilla luciferase was included as a transfection control. Cells were then stimulated with either 10 ng/ml of bovine serum albumin (BSA) or tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α. After 8 h, cells were lysed, and luciferase activities were determined (right). Experiments were performed three times, each with triplicate determinations and mean values with associated errors are shown (mean ± S.E.). B-gal, β-galactosidase.

The c-Fos transcription factor is a transcriptional target of MAPK signaling, and is also phosphorylated and activated by the p38α pathway in UV-irradiated cells (39, 40). Furthermore, failure to induce DUSP1/MKP-1 in MEFs derived from c-Fos−/− mice during the late phase response to UV irradiation has been linked with increased JNK activation and apoptosis (30). However, we observe that DUSP1/MKP-1 mRNA is induced with normal kinetics during the early response to UV radiation in MEFs derived from c-Fos−/− mice (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, DUSP1/MKP-1 mRNA levels are actually increased at later times after UV irradiation in c-Fos−/− MEFs. This is reflected in higher protein levels, and is not mediated by increased mRNA stability (supplemental Fig. S2, A and B). We presume that loss of c-Fos may have some effect, either directly or indirectly, on levels of DUSP1/MKP-1 transcription.

The activating transcription factor (ATF) family of leucine zipper transcription factors can also mediate transcription via cAMP-responsive element (CRE) and AP-1 sites in target gene promoters, and may contain transcriptional activation domains that are substrates for both JNK and p38α MAPKs (41, 42). A recent paper (31) reported that feedback regulation of p38α MAPK signaling by DUSP1/MKP-1 was abrogated in the livers of double knock-out mice lacking ATF2 and the related transcription factor ATF7. We obtained MEFs from Atf2−/−/Atf7−/− animals, but these show no apparent defect in the UV-induced expression of DUSP1/MKP-1 mRNA when compared with MEFs from mice lacking ATF7 alone (Fig. 4C). The induction of DUSP1/MKP-1 by γ-radiation is an NF-κB-dependent process (14), and p38α is a known transducer of survival signals via NF-κB in UV-irradiated cells (43). However, we found that DUSP1/MKP-1 mRNA induction is unaffected by overexpression of the NF-κB repressor Mad3, despite efficient inhibition of a bona fide NF-κB-dependent reporter (Fig. 4D).

DUSP1/MKP-1 mRNA is inducible by cAMP-dependent signaling via CREs within the gene promoter (44–46). The transcription factor CREB is phosphorylated by protein kinase A in response to elevated cAMP levels. However, CREB is also a substrate for the mitogen and stress-activated kinases (MSKs)-1 and -2, which are in turn activated by ERK and p38α MAPKs (47, 48). Interestingly, p38α-mediated MSK1 activation is also associated with the phosphorylation of histone H3 associated with the DUSP1/MKP-1 gene in response to sodium arsenite, and is thought to play a role in chromatin remodeling associated with the stress-induced transcriptional induction of DUSP1/MKP-1 (22).

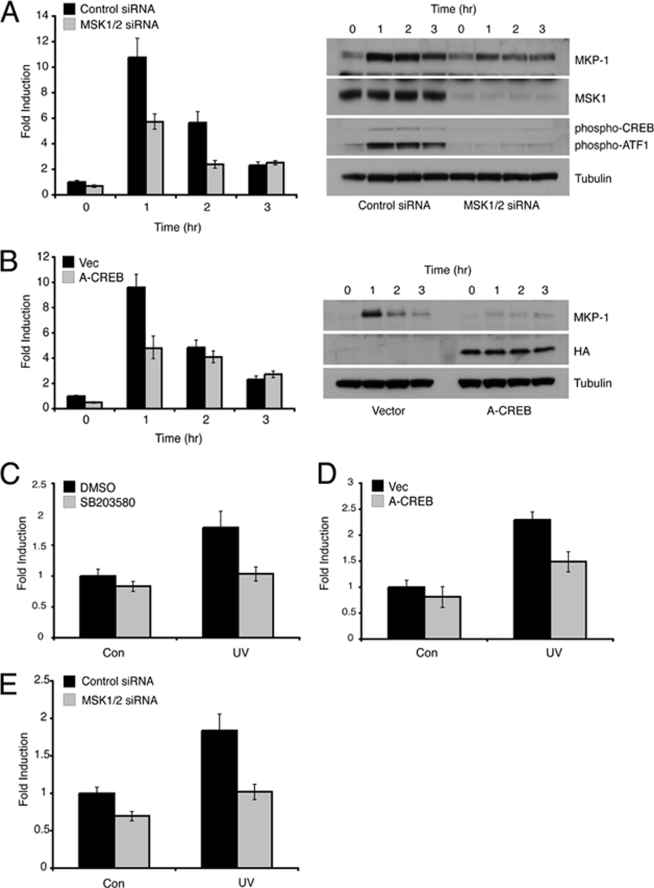

To determine whether p38α-mediated activation of MSK1 and MSK2 is involved in the UV-inducible expression of DUSP1/MKP-1, we assessed the induction of DUSP1/MKP-1 in wild-type MEFs depleted of MSK1 and MSK2 by siRNA-mediated knockdown. UV-inducible phosphorylation of both CREB and ATF1 was significantly reduced in cells transfected with siRNAs targeting both MSK1 and -2, and this was accompanied by a significant reduction in the levels of both DUSP1/MKP-1 mRNA and protein following exposure to UV radiation (Fig. 5A). In contrast, DUSP1/MKP-1 induction by serum stimulation was unaffected by knockdown of MSK1 and -2 (data not shown). To probe the involvement of CREB in the UV-induced expression of DUSP1/MKP-1, we used hemagglutinin-tagged A-CREB, a dominant-negative form of CREB that lacks the DNA binding domain, but is able to dimerize with endogenous CREB and ATF1, thus preventing DNA binding (20). Expression of A-CREB caused a significant reduction in DUSP1/MKP-1 mRNA and protein levels in UV-irradiated MEFs (Fig. 5B). In agreement with these findings, a luciferase reporter driven by a 3-kb fragment of the Dusp1/Mkp-1 promoter shows significant UV-inducible activity when stably transfected into wild-type MEFs. Furthermore, this activity is suppressed by the p38α inhibitor SB203580 (Fig. 5C), the overexpression of A-CREB (Fig. 5D), or siRNA-mediated knockdown of both MSK1 and -2 (Fig. 5E). We conclude that the p38α signal transduction pathway activates UV-inducible DUSP1/MKP-1 transcription at least in part by the MSK1/2-dependent phosphorylation of CREB/ATF1.

FIGURE 5.

Induction of DUSP1/MKP-1 by UV is dependent on signaling via MSK1/2 and CREB/ATF1. A, wild-type MEFs were transfected with either a control siRNA, or siRNAs targeting MSK1 and MSK2. Cells were either mock irradiated or exposed to 30 J/m2 UV and then incubated at 37 °C for the indicated times. Cells were then lysed and either DUSP1/MKP-1 mRNA levels were determined using quantitative RT-PCR (left) or proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using the indicated antibodies (right). B, wild-type MEFs were transfected with either empty vector or an expression vector (Vec) encoding hemagglutinin-tagged A-CREB. After 24 h, cells were either mock irradiated or exposed to 30 J/m2 UV and then incubated at 37 °C for the indicated times. Cells were then lysed and either DUSP1/MKP-1 mRNA levels were determined using quantitative RT-PCR (left) or proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using the indicated antibodies (right). Wild-type MEFs stably transfected with the MKP-1 reporter pGL4.28-MKP-1-luc were either pre-treated for 1 h with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or 10 μm SB203580 (C), transfected with either empty vector or an expression vector encoding A-CREB (D), or transfected with either a control siRNA or siRNAs targeting MSK1 and -2 (E). Cells were then either mock irradiated or exposed to 30 J/m2 UV and incubated at 37 °C for 8 h. Cells were then lysed, firefly luciferase activity was quantified and its levels normalized to protein concentration. Experiments were performed three times, each with triplicate determinations, and mean values with associated errors are shown (mean ± S.E.). DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; HA, hemagglutinin.

DUSP1/MKP-1 Is an Essential, Non-redundant Regulator of Both JNK and p38α Signaling in UV-irradiated MEFs

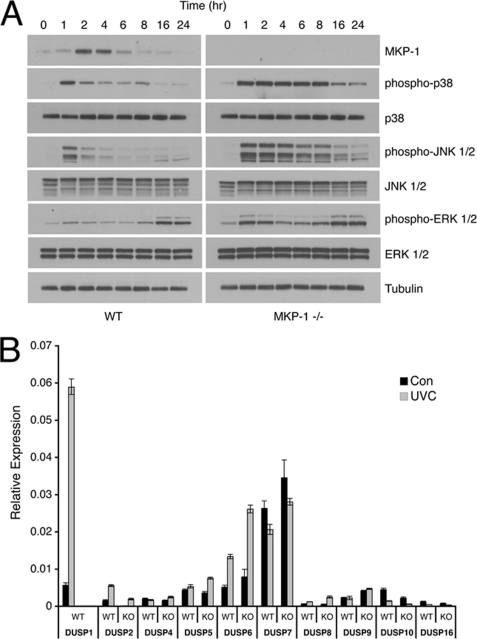

Conditional overexpression of DUSP1/MKP-1 has been demonstrated to suppress the activity of both the p38α and JNK MAPKs, and to protect cells against UV-induced cell death (49). However, the effects of endogenous DUSP1/MKP-1 knockdown or deletion have not previously been assessed in the context of the response to UV-induced DNA damage. We obtained immortalized MEFs from Dusp1/Mkp-1−/− mice, and determined the kinetics of ERK, p38α, and JNK phosphorylation following UV irradiation (Fig. 6A). The most obvious effects of Dusp1/Mkp-1 deletion are that both the magnitude and duration of p38α and JNK phosphorylation are greatly increased, with significantly elevated levels seen up to 16 h after irradiation. The classical ERK1/2 pathway is also modulated by DUSP1/MKP-1, with a rapid but transient phosphorylation observed in cells lacking DUSP1/MKP-1, whereas no significant increase in ERK phosphorylation is seen in wild-type MEFs. Our results suggest that DUSP1/MKP-1 is the major phosphatase responsible for the inactivation of both p38α and JNK, and also that endogenous DUSP1/MKP-1 is responsible for preventing significant activation of the ERK pathway in UV-irradiated cells. In support of the former, we also observe that DUSP1/MKP-1 is the only member of the DUSP/MKP family to exhibit significantly increased mRNA levels in UV-irradiated wild-type MEFs. Furthermore, deletion of Dusp1/Mkp-1 does not lead to compensatory changes in the mRNA levels of 8 of the other 9 DUSP/MKP transcripts (Fig. 6B). The exception is the ERK-specific phosphatase DUSP6/MKP-3, which is slightly up-regulated in Dusp1/Mkp-1−/− MEFs. As the DUSP6/MKP-3 gene is a transcriptional target of the ERK pathway (21), this is probably due to the transient increase in ERK activation we observe in cells lacking DUSP1/MKP-1.

FIGURE 6.

DUSP1/MKP-1 is an essential non-redundant regulator of UV-induced p38α and JNK signaling. A, wild-type (WT) or Dusp1/Mkp-1−/− MEFs were either mock irradiated or exposed to 30 J/m2 UV and then incubated at 37 °C for the indicated times. Cells were then lysed, and proteins analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using the indicated antibodies. B, WT or Dusp1/Mkp-1−/− MEFs were either mock irradiated or exposed to 30 J/m2 UV and then incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. DUSP/MKP mRNA levels were determined using quantitative RT-PCR. Experiments were performed three times, each with triplicate determinations, and mean values with associated errors are shown (mean ± S.E.). KO, knock-out.

Consistent with increased p38α and JNK phosphorylation in cells lacking DUSP1/MKP-1, we also observe modulation of several MAPK targets. These include increased levels of c-Fos mRNA (Fig. 7A) and increased phosphorylation of MAPK-activated protein kinase 2 (MAPKAP kinase 2 or MK2) and c-Jun (Fig. 7B). In agreement with our conclusion that the Dusp1/Mkp-1 gene is transcriptionally up-regulated in response to p38α signaling, a luciferase reporter driven by a 3-kb fragment of the DUSP1/MKP-1 promoter shows increased UV-inducible activity following transient transfection into Dusp1/Mkp-1 null MEFs when compared with wild-type cells. The apparent lack of response in the latter reflects the decreased sensitivity of this reporter following transient transfection. This activity is completely suppressed by exposure to the p38α and -β inhibitor, SB203580 (Fig. 7C).

FIGURE 7.

Loss of DUSP1/MKP-1 results in increased MAPK signaling and gene transcription. A, wild-type (WT) or Dusp1/Mkp-1−/− MEFs were either mock irradiated or exposed to 30 J/m2 UV and then incubated at 37 °C for the indicated times. c-Fos mRNA levels were determined using quantitative RT-PCR. B, wild-type or Dusp1/Mkp-1−/− MEFs were either mock irradiated or exposed to 30 J/m2 UV and then incubated at 37 °C for the indicated times. Cells were lysed, and proteins analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting using the indicated antibodies. C, wild-type or Dusp1/Mkp-1−/− MEFs were cotransfected with a firefly luciferase reporter driven by the proximal 3-kb region of the DUSP1/MKP-1 promoter and as a transfection control a plasmid encoding Renilla luciferase. After 24 h, cells were preincubated with either dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or 10 μm SB203580 (SB), exposed to 30 J/m2 UV, and then incubated at 37 °C for 5 h. Cells were lysed, and luciferase activities were determined. Experiments were performed three times, each with triplicate determinations and mean values with associated errors are shown (mean ± S.E.).

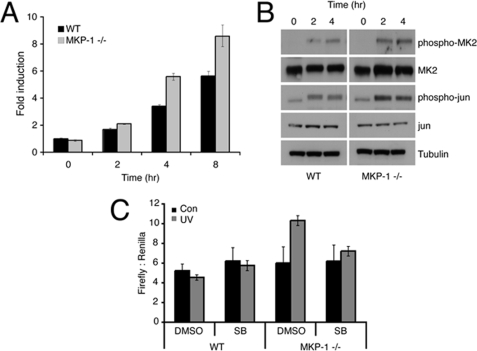

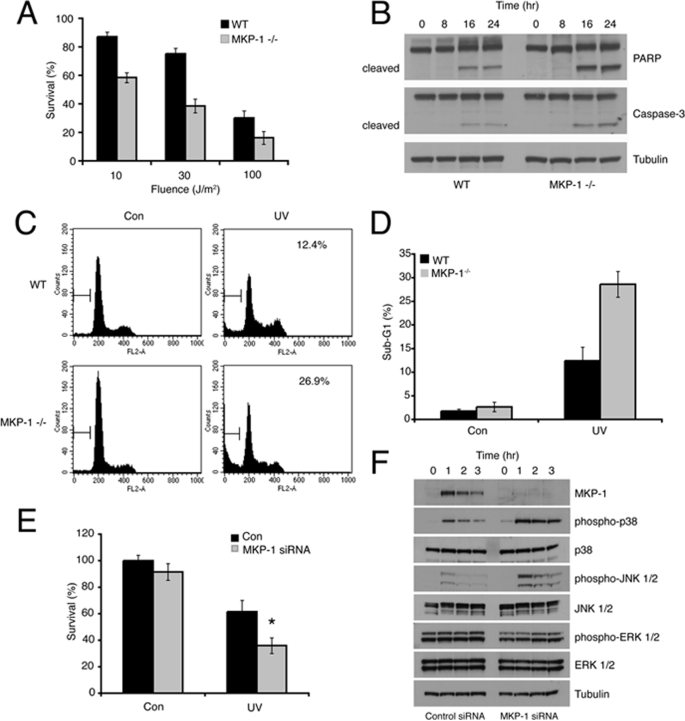

Cells Lacking DUSP1/MKP-1 Show Increased Sensitivity to UV-induced Apoptosis Mediated by JNK

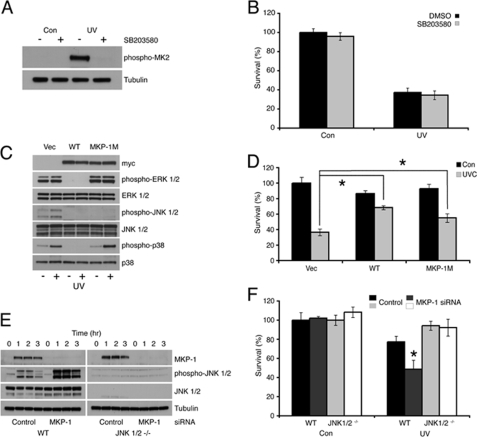

MEFs from mice lacking DUSP1/MKP-1 are sensitive to a range of chemical and physical stress conditions including hydrogen peroxide, cisplatin, anisomycin, and ionizing radiation (11–14). However, the role of DUSP1/MKP-1 in protection against UV-induced cell death has only been addressed by conditional overexpression of DUSP1/MKP-1 in U937 human leukemia cells (49). To determine whether endogenous DUSP1/MKP-1 protects cells against UV radiation, we first compared the survival of wild-type and Dusp1/Mkp-1−/− MEFs. Cells lacking DUSP1/MKP-1 show significantly decreased viability when compared with wild-type cells as assessed using the MTS assay at UV fluences between 10 and 100 J/m2 (Fig. 8A). This decrease in viability is characterized by hallmarks of apoptotic or programmed cell death, including increased caspase-dependent cleavage of both poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase and caspase-3 itself (Fig. 8B), and increased accumulation of cells with sub-G1 DNA content (Fig. 8, C and D). This is unlikely to be due to long-term adaptation to gene loss, as specific siRNA-mediated knockdown of DUSP1/MKP-1 also leads to increased phosphorylation of p38α and JNK, and is accompanied by a significant decrease in viability after UV irradiation (Fig. 8, E and F). To dissect out the MAPK pathways involved in mediating cell death in Dusp1/Mkp-1−/− MEFS, we first employed SB203580, a specific inhibitor of p38α and -β. As expected, SB203580 blocked the UV-induced phosphorylation of the p38 substrate MAPKAP kinase 2/MK2. However, this drug did not affect levels of UV-induced lethality, indicating that the sustained activation of p38 MAPK seen in cells lacking DUSP1/MKP-1 does not modulate UV-induced apoptosis (Fig. 9, A and B). Increased JNK activity has been implicated in cell death in cells lacking DUSP1/MKP-1 in response to cisplatin and ionizing radiation, largely based on the ability of the chemical inhibitor SP600125 to reduce levels of apoptosis (12, 14). To circumvent problems associated with chemical inhibition of JNK, we have made use of wild-type DUSP1/MKP-1 and a DUSP1/MKP-1 mutant (MKP-1M). MKP-1 M contains substitutions within the highly conserved kinase interaction motif in the amino-terminal non-catalytic domain of the protein. Although MKP-1 M retains its ability to bind to and inactivate JNK, it is no longer able to interact with or inactivate ERK or p38α (5). The re-expression of wild-type DUSP1/MKP-1 leads to suppression of ERK, p38α, and JNK activation in UV-irradiated Dusp1/Mkp-1−/− MEFs, and also results in a significant rescue of UV-induced lethality (Fig. 9, C and D). In contrast, expression of MKP-1 M does not affect phosphorylation of ERK, or the ability of UV radiation to activate p38α, but does result in complete abolition of JNK phosphorylation. Interestingly, MKP-1 M expression rescues UV-induced lethality in Dusp1/Mkp-1−/− MEFs almost as effectively as wild-type DUSP1/MKP-1 (Fig. 9D). Finally, we have assessed the effects of siRNA-mediated knockdown of DUSP1/MKP-1 on the UV sensitivity of both wild-type MEFs and MEFs lacking JNK1 and JNK2. Although knockdown of DUSP1/MKP-1 in wild-type cells results in a significant increase in levels of phospho-JNK and a significant decrease in survival after UV irradiation, DUSP1/MKP-1 knockdown has no effect on the viability of cells lacking both JNK1 and JNK2 after UV irradiation (Fig. 9, E and F). This indicates that these JNK isoforms are the relevant target for DUSP1/MKP-1 in protection against UV-induced lethality. Overall, our data demonstrate that it is the prolonged activation of JNK, and not p38α, which is important in mediating UV-induced cell death.

FIGURE 8.

Loss of DUSP1/MKP-1 sensitizes cells to UV-induced apoptosis. A, wild-type (WT) or Dusp1/Mkp-1−/− MEFs were exposed to 0, 10, 30, or 100 J/m2 UV, and then incubated at 37 °C for 36 h. Cell survival was assessed by MTS assay, and results were normalized to untreated control values. B, wild-type or Dusp1/Mkp-1−/− MEFs were exposed to 30 J/m2 UV, and then incubated at 37 °C for the indicated times. Cells were lysed, and proteins analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting using the indicated antibodies. C and D, wild-type or Dusp1/Mkp-1−/− MEFs were exposed to 30 J/m2 UV, and then incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. Cells were fixed in ethanol and stained using propidium iodide. Cell death was assessed by flow cytometry. E, wild-type MEFs were transfected with either a control siRNA, or an siRNA targeting DUSP1/MKP-1. After 48 h, cells were exposed to 30 J/m2 UV. Cell survival was assessed after 36 h by MTS assay, and results were normalized to untreated control values. F, wild-type MEFs were transfected as in E, exposed to 30 J/m2 UV, and then incubated at 37 °C for the indicated times. Cells were then lysed, and proteins analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting using the indicated antibodies. Experiments were performed three times, with triplicate determinations, and mean values with associated errors are shown (mean ± S.E.). * = p < 0.05, comparing the survival of UV-irradiated cells transfected with either control or DUSP1/MKP-1 siRNA using the Student's t test. PARP, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase.

FIGURE 9.

UV-induced cell death is JNK dependent. A, Dusp1/Mkp-1−/− MEFs were pre-treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or 10 μm SB203580, and then exposed to 30 J/m2 UV. Following incubation at 37 °C for 1 h, cells were lysed, and proteins analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting using the indicated antibodies. B, Dusp1/Mkp-1−/− MEFs were treated as in A. After 36 h, cell survival was assessed by MTS assay and the results normalized to untreated control values. C, Dusp1/Mkp-1−/− MEFs were transfected with either empty vector or an expression vector encoding either wild-type (WT) MKP-1 or MKP-1 M. After 24 h, cells were exposed to 30 J/m2 UV and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. Cells were then lysed, and proteins analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting using the indicated antibodies. D, Dusp1/Mkp-1−/− MEFs were transfected as in C. After 24 h, cells were exposed to 30 J/m2 UV. Following incubation at 37 °C for 36 h, cell survival was assessed by MTS assay, and the results were normalized to untreated control values. * = p < 0.05, comparing the survival of UV-irradiated cells transfected with empty vector with those transfected with either an expression vector encoding WT MKP-1, or those transfected with an expression vector encoding MKP-1 M using Student's t test. E, wild-type and Jnk1/2−/− MEFs were transfected with either a control siRNA, or an siRNA targeting DUSP1/MKP-1. After 48 h, cells were either mock irradiated or exposed to 30 J/m2 UV, and then incubated at 37 °C for the indicated times. Cells were lysed, and proteins analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting using the indicated antibodies. F, wild-type and Jnk1/2−/− MEFs were transfected as in E, then either mock irradiated or exposed to 30 J/m2 UV. Cell survival was assessed after 36 h by MTS assay, and results were normalized to untreated control values. * = p < 0.05, comparing the survival of UV-irradiated cells transfected with control siRNA and those transfected with an siRNA targeting MKP-1 using Student's t test. Experiments were performed three times, each with triplicate determinations, and mean values with associated errors are shown (mean ± S.E.).

DISCUSSION

We have investigated the mechanism of induction of DUSP1/MKP-1, and the role subsequently played by this phosphatase in the modulation of the apoptotic response to UV radiation. Apoptosis is an important means by which cells with irreparably damaged DNA can be removed. DUSP1/MKP-1 is highly expressed in human tumors and, in some cases, is an independent prognostic indicator (50, 51). Moreover, DUSP1/MKP-1 is induced by cisplatin and can mediate chemoresistance (52). This latter observation suggests that DUSP1/MKP-1 could be a potential therapeutic target. The identification of the pathways responsible for DUSP1/MKP-1 induction by DNA damaging agents including UV and cisplatin is therefore of interest.

We have demonstrated that DUSP1/MKP-1 induction by UV radiation, cisplatin, and oxidative stress is dependent on p38α signaling, but is completely independent of JNK1 and -2. A previous report (22) suggested that increased p38α-mediated histone H3 phosphorylation within chromatin associated with the DUSP1/MKP-1 gene is involved in mediating its stress-induced transcription. Furthermore, the MSK1 protein kinase was activated in a p38α-dependent manner with identical kinetics to those of H3 modification in cells exposed to sodium arsenite, suggesting that MSK1 may be the relevant H3 kinase. A more recent report suggests an even stronger link between histone H3 phosphorylation and DUSP1/MKP-1 expression, postulating that DUSP1/MKP-1 is itself a histone H3 Ser-10 phosphatase and negatively regulates it own expression by reversing this chromatin modification (53). However, we have examined the kinetics of H3 phosphorylation and, although loss of this modification does correlate temporally with induction of the DUSP1/MKP-1 protein in wild-type cells, H3 dephosphorylation occurs with identical kinetics in MEFs lacking DUSP1/MKP-1 (data not shown), indicating that DUSP1/MKP-1 is not the relevant activity. Our own data suggests a more direct role for MSK1 and -2 in regulating DUSP1/MKP-1 expression via phosphorylation of transcription factors CREB/ATF1. Interestingly, a recent report (54) indicates that it may be the recruitment of MSK1 by phospho-CREB itself that facilitates histone H3 phosphorylation at CRE-dependent promoters.

Recent work has identified DUSP1/MKP-1 as a critical negative regulator of MAPK signaling in the innate immune response (55). Initial reports indicated that ERK activity was required for the transcriptional activation of DUSP1/MKP-1 in response to bacterial LPS in alveolar macrophages (27). However, more recent studies using conditional deletion of p38α in the myeloid lineage have demonstrated that this kinase is an essential component of the signaling pathways activated downstream of Toll-like receptors in response to LPS in bone marrow-derived macrophages (56). Interestingly, LPS-inducible expression of DUSP1/MKP-1 was significantly attenuated in these cells, as was the amount of phosphorylated CREB associated with the DUSP1/MKP-1 gene promoter. In parallel experiments performed in Msk1/Msk2 double knock-out macrophages, LPS-inducible DUSP1/MKP-1 expression was also significantly reduced (57). Our results indicate that the regulation of DUSP1/MKP-1 expression following both the engagement of Toll-like receptors in macrophages, and the induction of DNA damage in MEFs, share common pathway components downstream of p38α MAPK.

The greatly extended time course of both p38 and JNK phosphorylation observed in UV-irradiated Dusp1/Mkp-1−/− MEFs suggests that the induction of this phosphatase is the predominant mechanism by which the activity of these MAPKs is regulated. We have assessed the mRNA levels of all 10 members of the DUSP/MKP family, and find that DUSP1/MKP-1 is the only phosphatase that shows a significant increase in expression after treatment with UV or cisplatin. Interestingly, several DUSP/MKP genes are reported to be responsible for the coordinated regulation of JNK activity in human embryonic kidney 293T cells exposed to hydrogen peroxide (58). However, we observed that peroxide-treated MEFs respond very similarly to UV-irradiated cells, in that DUSP1/MKP-1 is the only phosphatase to show significant up-regulation (data not shown). This is consistent with recent observations of increased p38α/JNK activation and lethality in peroxide-treated MEFs from Dusp1/Mkp-1 knock-out mice (11).

The involvement of DUSP1/MKP-1 in the regulation of UV-induced lethality was surmised from previous experiments in which DUSP1/MKP-1 was conditionally overexpressed in a human leukemia cell line (49). Here we have shown for the first time using loss of function experiments that the induction of endogenous DUSP1/MKP-1 and the resulting inhibition of JNK activity is essential in protecting cells from the lethal effects of UV radiation. This finding is consistent with a role for persistent JNK activation in the promotion of cell death (59), and the observation that cells lacking JNK1 and JNK2 are relatively resistant to UV-induced apoptosis (60). In contrast, JNK-mediated activation of ATF2 and c-Jun has also been implicated in the stress-induced transcription of several genes involved in DNA repair (61). It is possible that Dusp1/Mkp-1 null cells may operate a more efficient DNA repair program than their wild-type counterparts, due to enhanced JNK signaling. However, our results indicate that prolonged JNK activation in these cells overrides any survival advantage by initiating programmed cell death. Christmann et al. (30) have suggested that reduced levels of DNA repair may result in impaired transcription of DUSP1/MKP-1, resulting in JNK-mediated cell death. Deletion of DUSP1/MKP-1 may thus uncouple a mechanism that links DNA repair efficiency to survival via the modulation of JNK activity. This will be the focus of a future investigation.

In conclusion, our findings indicate that DUSP1/MKP-1 induction represents a mechanism by which cross-talk between two distinct stress-inducible MAPK pathways regulates the biological outcome of signaling. Signal integration by the p38α and JNK pathways has emerged as an important determinant of cellular responses in a wide variety of tissues and pathologies, including inflammation and cancer (62). Our work suggests that cross-talk mediated by DUSP1/MKP-1 plays a key role in determining cell fate following exposure to DNA damaging agents such as UV radiation and cisplatin.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Angel Nebreda (CNIO Madrid) for the kind gift of p38α−/− MEFs, Dr. Cathy Tournier (University of Manchester) and Dr. Roger Davis (HHMI, University of Massachusetts Medical School) for providing Jnk1/2−/− MEFs, Prof. Yusen Liu (Nationwide Childrens Hospital, Columbus, OH) for pGL3-3kb-MKP-1-luc, Prof. Bernd Kaina (University of Mainz, Mainz, Germany) for c-Fos−/− MEFs, Prof. Simon Arthur for pRC-A-CREB-hemagglutinin, and Dr. Wolfgang Breitweiser (Paterson Institute, Manchester, UK) for providing Atf2+/+/Atf7−/− and Atf2−/−/Atf7−/− MEFs.

This work was supported a grant from Cancer Research UK (to S. M. K.) and a MRC Ph.D studentship (to C. J. S.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1 and S2.

- DUSP1/MKP-1

- dual specificity phosphatase-1/mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1

- ATF

- activating transcription factor

- CRE

- cAMP-response element

- CREB

- cAMP-response element-binding protein

- MSK

- mitogen and stress-activated kinase

- MEF

- mouse embryo fibroblast

- BisTris

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol

- MTS

- 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dickinson R. J., Keyse S. M. (2006) J. Cell Sci. 119, 4607–4615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Owens D. M., Keyse S. M. (2007) Oncogene 26, 3203–3213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chu Y., Solski P. A., Khosravi-Far R., Der C. J., Kelly K. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 6497–6501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Groom L. A., Sneddon A. A., Alessi D. R., Dowd S., Keyse S. M. (1996) EMBO J. 15, 3621–3632 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slack D. N., Seternes O. M., Gabrielsen M., Keyse S. M. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 16491–16500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chi H., Barry S. P., Roth R. J., Wu J. J., Jones E. A., Bennett A. M., Flavell R. A. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 2274–2279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hammer M., Mages J., Dietrich H., Servatius A., Howells N., Cato A. C., Lang R. (2006) J. Exp. Med. 203, 15–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao Q., Wang X., Nelin L. D., Yao Y., Matta R., Manson M. E., Baliga R. S., Meng X., Smith C. V., Bauer J. A., Chang C. H., Liu Y. (2006) J. Exp. Med. 203, 131–140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Y., Reynolds J. M., Chang S. H., Martin-Orozco N., Chung Y., Nurieva R. I., Dong C. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 30815–30824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu J. J., Roth R. J., Anderson E. J., Hong E. G., Lee M. K., Choi C. S., Neufer P. D., Shulman G. I., Kim J. K., Bennett A. M. (2006) Cell Metab. 4, 61–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou J. Y., Liu Y., Wu G. S. (2006) Cancer Res. 66, 4888–4894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Z., Xu J., Zhou J. Y., Liu Y., Wu G. S. (2006) Cancer Res. 66, 8870–8877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu J. J., Bennett A. M. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 16461–16466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Z., Cao N., Nantajit D., Fan M., Liu Y., Li J. J. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 21011–21023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang J., Zhou J. Y., Wu G. S. (2007) Cancer Res. 67, 11933–11941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sánchez-Tilló E., Comalada M., Xaus J., Farrera C., Valledor A. F., Caelles C., Lloberas J., Celada A. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 12566–12573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu J. H., Chen T., Zhuang Z. H., Kong L., Yu M. C., Liu Y., Zang J. W., Ge B. X. (2007) Cell. Signal. 19, 393–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dorfman K., Carrasco D., Gruda M., Ryan C., Lira S. A., Bravo R. (1996) Oncogene 13, 925–931 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raingeaud J., Gupta S., Rogers J. S., Dickens M., Han J., Ulevitch R. J., Davis R. J. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 7420–7426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahn S., Olive M., Aggarwal S., Krylov D., Ginty D. D., Vinson C. (1998) Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 967–977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ekerot M., Stavridis M. P., Delavaine L., Mitchell M. P., Staples C., Owens D. M., Keenan I. D., Dickinson R. J., Storey K. G., Keyse S. M. (2008) Biochem. J. 412, 287–298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li J., Gorospe M., Hutter D., Barnes J., Keyse S. M., Liu Y. (2001) Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 8213–8224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duckett C. S., Perkins N. D., Kowalik T. F., Schmid R. M., Huang E. S., Baldwin A. S., Jr., Nabel G. J. (1993) Mol. Cell. Biol. 13, 1315–1322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuwano Y., Kim H. H., Abdelmohsen K., Pullmann R., Jr., Martindale J. L., Yang X., Gorospe M. (2008) Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 4562–4575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iordanov M. S., Pribnow D., Magun J. L., Dinh T. H., Pearson J. A., Magun B. E. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 15794–15803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu Q., Konta T., Nakayama K., Furusu A., Moreno-Manzano V., Lucio-Cazana J., Ishikawa Y., Fine L. G., Yao J., Kitamura M. (2004) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 36, 985–993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen P., Li J., Barnes J., Kokkonen G. C., Lee J. C., Liu Y. (2002) J. Immunol. 169, 6408–6416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li M., Zhou J. Y., Ge Y., Matherly L. H., Wu G. S. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 41059–41068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang H., Wu G. S. (2004) Cancer Biol. Ther. 3, 1277–1282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Christmann M., Tomicic M. T., Aasland D., Kaina B. (2007) Carcinogenesis 28, 183–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Breitwieser W., Lyons S., Flenniken A. M., Ashton G., Bruder G., Willington M., Lacaud G., Kouskoff V., Jones N. (2007) Genes Dev. 21, 2069–2082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bain J., McLauchlan H., Elliott M., Cohen P. (2003) Biochem. J. 371, 199–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adams R. H., Porras A., Alonso G., Jones M., Vintersten K., Panelli S., Valladares A., Perez L., Klein R., Nebreda A. R. (2000) Mol. Cell 6, 109–116 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuan C. Y., Yang D. D., Samanta Roy D. R., Davis R. J., Rakic P., Flavell R. A. (1999) Neuron 22, 667–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.She Q. B., Chen N., Dong Z. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 20444–20449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sanchez-Prieto R., Rojas J. M., Taya Y., Gutkind J. S. (2000) Cancer Res. 60, 2464–2472 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bunz F., Hwang P. M., Torrance C., Waldman T., Zhang Y., Dillehay L., Williams J., Lengauer C., Kinzler K. W., Vogelstein B. (1999) J. Clin. Invest. 104, 263–269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zindy F., Eischen C. M., Randle D. H., Kamijo T., Cleveland J. L., Sherr C. J., Roussel M. F. (1998) Genes Dev. 12, 2424–2433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tanos T., Marinissen M. J., Leskow F. C., Hochbaum D., Martinetto H., Gutkind J. S., Coso O. A. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 18842–18852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Price M. A., Cruzalegui F. H., Treisman R. (1996) EMBO J. 15, 6552–6563 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raingeaud J., Whitmarsh A. J., Barrett T., Dérijard B., Davis R. J. (1996) Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 1247–1255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gupta S., Campbell D., Dérijard B., Davis R. J. (1995) Science 267, 389–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gupta M., Gupta S. K., Hoffman B., Liebermann D. A. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 17552–17558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ryser S., Massiha A., Piuz I., Schlegel W. (2004) Biochem. J. 378, 473–484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sommer A., Burkhardt H., Keyse S. M., Lüscher B. (2000) FEBS Lett. 474, 146–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burgun C., Esteve L., Humblot N., Aunis D., Zwiller J. (2000) FEBS Lett. 484, 189–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Deak M., Clifton A. D., Lucocq L. M., Alessi D. R. (1998) EMBO J. 17, 4426–4441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wiggin G. R., Soloaga A., Foster J. M., Murray-Tait V., Cohen P., Arthur J. S. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 2871–2881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Franklin C. C., Srikanth S., Kraft A. S. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 3014–3019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rojo F., González-Navarrete I., Bragado R., Dalmases A., Menéndez S., Cortes-Sempere M., Suárez C., Oliva C., Servitja S., Rodriguez-Fanjul V., Sánchez-Pérez I., Campas C., Corominas J. M., Tusquets I., Bellosillo B., Serrano S., Perona R., Rovira A., Albanell J. (2009) Clin. Cancer Res. 15, 3530–3539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vicent S., Garayoa M., López-Picazo J. M., Lozano M. D., Toledo G., Thunnissen F. B., Manzano R. G., Montuenga L. M. (2004) Clin. Cancer Res. 10, 3639–3649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sánchez-Pérez I., Martínez-Gomariz M., Williams D., Keyse S. M., Perona R. (2000) Oncogene 19, 5142–5152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kinney C. M., Chandrasekharan U. M., Yang L., Shen J., Kinter M., McDermott M. S., DiCorleto P. E. (2009) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 296, C242–249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shimada M., Nakadai T., Fukuda A., Hisatake K. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 9390–9401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang X., Liu Y. (2007) Cell. Signal. 19, 1372–1382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim C., Sano Y., Todorova K., Carlson B. A., Arpa L., Celada A., Lawrence T., Otsu K., Brissette J. L., Arthur J. S., Park J. M. (2008) Nat. Immunol. 9, 1019–1027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ananieva O., Darragh J., Johansen C., Carr J. M., McIlrath J., Park J. M., Wingate A., Monk C. E., Toth R., Santos S. G., Iversen L., Arthur J. S. (2008) Nat. Immunol. 9, 1028–1036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Teng C. H., Huang W. N., Meng T. C. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 28395–28407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen Y. R., Wang X., Templeton D., Davis R. J., Tan T. H. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 31929–31936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tournier C., Hess P., Yang D. D., Xu J., Turner T. K., Nimnual A., Bar-Sagi D., Jones S. N., Flavell R. A., Davis R. J. (2000) Science 288, 870–874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hayakawa J., Mittal S., Wang Y., Korkmaz K. S., Adamson E., English C., Ohmichi M., Omichi M., McClelland M., Mercola D. (2004) Mol. Cell 16, 521–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wagner E. F., Nebreda A. R. (2009) Nat. Rev. Cancer 9, 537–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.