Abstract

Self-assembly of complex structures is commonplace in biology but often poorly understood. In the case of the actin cytoskeleton, a great deal is known about the components that include higher order structures, such as lamellar meshes, filopodial bundles, and stress fibers. Each of these cytoskeletal structures contains actin filaments and cross-linking proteins, but the role of cross-linking proteins in the initial steps of structure formation has not been clearly elucidated. We employ an optical trapping assay to investigate the behaviors of two actin cross-linking proteins, fascin and α-actinin, during the first steps of structure assembly. Here, we show that these proteins have distinct binding characteristics that cause them to recognize and cross-link filaments that are arranged with specific geometries. α-Actinin is a promiscuous cross-linker, linking filaments over all angles. It retains this flexibility after cross-links are formed, maintaining a connection even when the link is rotated. Conversely, fascin is extremely selective, only cross-linking filaments in a parallel orientation. Surprisingly, bundles formed by either protein are extremely stable, persisting for over 0.5 h in a continuous wash. However, using fluorescence recovery after photobleaching and fluorescence decay experiments, we find that the stable fascin population can be rapidly competed away by free fascin. We present a simple avidity model for this cross-link dissociation behavior. Together, these results place constraints on how cytoskeletal structures assemble, organize, and disassemble in vivo.

Keywords: Actin, Cell Motility, Cytoskeleton, Fluorescence, Single Molecule Biophysics, FRAP, alpha-Actinin, Fascin, Optical Trap

Introduction

The actin cytoskeleton forms and manages an array of diverse structures with regularity and precision. The same set of tools is used by all cells to many different ends; for example, muscle cells form sarcomeres and non-muscle cells form filopodia, lamellipodia, and stress fibers (1–8). Formation and maintenance of actin cytoskeletal structures are critical for proper cell functions and viability (9–16), but the mechanisms of these actions are poorly understood.

A great deal of work has been done examining how cytoskeletal proteins are regulated and how they are sorted within the cell. Although assembly of complex cytoskeletal structures is clearly essential for the proper mechanical behavior of the cell, the physical mechanisms driving their assembly are incompletely understood. Mechanisms have been proposed for formations of structures such as filopodia (17–19) and stress fibers (20, 21). Filopodial nucleation is thought to occur by formation of the filopodial tip complex bringing together actin filament barbed ends, allowing local elongation leading to filopodial growth (17). A recent study using electron tomography has revealed that prior to filopodia nucleation at the plasma membrane of cultured fibroblasts, filaments in the lamellipodia can be observed in distinct pairs (22). The authors suggest these pairs may play a key role in filopodial nucleation. Stress fiber formation is proposed to function through the coalescence of actin bundles mediated by myosin II (23). Both of these key cellular structures require actin cross-linking proteins. In these models, the cross-linking proteins are described as simple molecular staples, but it is possible that they play a critical role in the formation of these and other high order structures. Here, we attempt to gain insight in the formation of cytoskeletal structures by performing an in vitro analysis of two very distinct actin cross-linking proteins, fascin and smooth muscle α-actinin, to determine orientations of filaments that are required to allow these proteins to form cross-links.

α-Actinin is a member of the spectrin family of proteins and is found in all eukaryotes (24). It is functional as an anti-parallel homodimer. Each monomer is composed of two carboxyl-terminal EF hand domains, four spectrin repeats, and two amino-terminal calponin homology domains that include the actin binding domain (25) (Fig. 1A). The actin binding domain is conserved with other actin cross-linkers, including fimbrin and filamin (25). Tissue-specific isoforms of α-actinin are involved in z-discs of sarcomeres in muscle cells and stress fibers in non-muscle cells (24). In vitro experiments have shown that α-actinin can form homogeneous actin networks (three-dimensional meshworks with uniform cross-linker density and mesh size), tight bundles, or a mixture of the two (26–29). Electron microscopy has captured α-actinin interacting with actin filaments in multiple orientations as follows: cross-linking parallel filaments, anti-parallel filaments, and side binding both actin binding domains of a single α-actinin dimer to one filament (30–32).

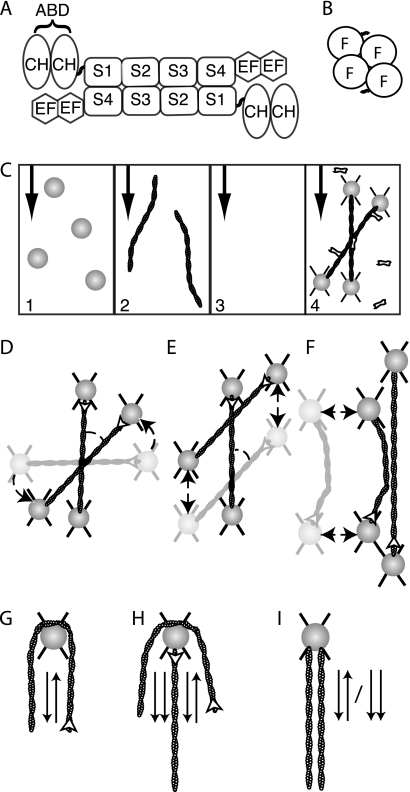

FIGURE 1.

Optically trapped filaments are used to build specific actin architectures for analysis of cross-linker angular dependence of binding. A, α-actinin is active as an anti-parallel homodimer. Each monomer contains an actin binding domain (ABD) composed of two calponin homology (CH) domains. A series of four spectrin repeats (S1–4) make up the dimerization domain. Each monomer also contains two EF hand domains that are responsible for modulating protein behavior based on calcium signaling (24). Smooth muscle α-actinin, the form used in this study, is calcium-insensitive. B, fascin is functional as a monomer made of a tight cluster of four fascin domains (F). C, flow chamber with four lanes is used to add reagents in isolation. Beads are added in channel 1, actin filaments in channel 2, and cross-linking proteins in channel 4. Channel 3, which contains only buffer, is used to arrange structures without accidental addition of other components and serves as a barrier between the actin and cross-linker channels to prevent diffusional mixing and unintended aggregation. The black arrows indicate the direction of flow. D, to examine binding behavior of proteins based on actin orientation, two actin filaments were trapped between four 1-μm polystyrene beads. Filaments were crossed and rotated (dashed arrow) until a desired angle was achieved. White arrowheads indicate filament polarity. × indicates optical traps. E, once the desired angle was achieved, one filament was scanned (dashed arrows) over the other, allowing for the exploration of a large number of potential binding sites. Binding events were recorded when the scanned filament stuck at one point on the stationary filament during the scan, and a deformation of the scanned filament was observed. F, parallel and anti-parallel arrangements were also tested. A single filament was stretched out perpendicular to the fluid flow, and a second filament was allowed to touch that filament tangentially. If no interaction was observed, one of the filaments was rotated 180°, and the experiment was repeated. G, to assess if the proteins would bind anti-parallel filaments, a single filament was wrapped around a bead, and the ends were allowed to interact. Arrows indicate the polarity of the neighboring section of filament. H, addition of a second filament to the wrapped filament assay produces areas of parallel and anti-parallel alignment. For proteins that are selective for parallel versus anti-parallel arrangements, the combination of the assays in G and H clearly shows the preference. I, single bead assays were also performed where two filaments of unknown polarity were attached to a single bead. If they always link, then there is no polarity preference. If they never link, then a given protein cannot bind aligned filaments. If they bind 50% of trails, it implies that there is a selection for one orientation, the orientation of which a wrapped bead experiment as described in section G can determine.

Fascin is a small globular protein that consists of four fascin-repeat domains tightly packed together (Fig. 1B). A crystal structure has been available for some time,2 and now new structures and examinations are giving more insight into the location of the actin-binding interfaces on the molecule (22, 33, 34). Fascin is conserved from Drosophila to humans and is a major component of the finger-like cellular projections known as filopodia, where it cross-links the tight actin bundle at the filopodial core (35). The actin in these bundles is arranged in a parallel manner with the barbed ends toward the tip of the projection (17). Fascin has not been observed to be a stable component of nonbundling structures (e.g. meshworks), instead forming a “network of bundles” rather than a homogeneous network as seen in α-actinin (36, 37). In vivo and in vitro work has shown fascin to be a dynamic cross-linker, rapidly turning over within filopodial bundles (38, 39).

Direct manipulation of actin cross-linking proteins has been performed (40, 41). Using optical trapping techniques, Miyata et al. (41) report rupture forces and bond lifetimes of α-actinin to actin bonds. Ferrer et al. (40) report rupturing the bonds and observing bond lifetimes between actin and the cross-linking proteins α-actinin and filamin. These studies show that the α-actinin to actin bond can sustain a large force (40–80 piconewtons) and report average bond lifetimes between 2.5 and 20 s. These are some of the first single molecule studies of cross-linkers, and they display surprising bond strength and stability.

Current models of how cytoskeletal structures nucleate and grow are based largely on evidence from video microscopy and snapshots from electron micrographs (17, 20, 22, 38). These studies make the assumption that growing filaments must attain a specific orientation and proximity before cross-linking proteins can nucleate and stabilize structures. In our study, we test that assumption directly by recreating a variety of actin structures like those cross-linking proteins might encounter in cells, and we assess the ability of the proteins to form and maintain cross-links. α-Actin and fascin show strikingly different behaviors in this assay. α-Actinin cross-links in every structure tested, although fascin only cross-links filaments in one specific orientation. Once the parameters for interaction were determined, we examined the dissociation behavior of these proteins from actin bundles and found that fascin dissociation from bundles seems to happen primarily in the presence of competitive agents but not in isolation. We propose a model where cross-links rapidly toggle between being bound to one and two filaments but are rarely lost to solution unless a competitive agent is present.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Protein Purification

Actin was purified using an established protocol (42). Actin was polymerized at a concentration of 10 μm monomer in assay buffer (AB: 25 mm imidazole, pH 7.5, 25 mm KCl, 1 mm EGTA, 4 mm MgCl2, and 10 mm dithiothreitol) in the presence of 2 mm ATP using 90% dark (unlabeled) actin and 10% biotinylated actin and then stabilized with tetramethylrhodamine (TMR)3-phalloidin. Polarity-labeled actin was made by growing a cap consisting of 30% TMR-labeled actin and 70% dark actin on the barbed end of dark filaments and then coating with Alexa-633 phalloidin. Human fascin was purified using an established method (43). Chicken smooth muscle α-actinin was purified using an established method (44). An additional gel filtration step was performed over a Sepharose 4B (Sigma) column to remove contaminants (supplemental Fig. S1). Proteins with chemical modifications (Biotin, TMR, and Atto-647N) were labeled using maleimide chemistry. Reactions of protein and 2–10 times molar excess dye were incubated overnight at 4 °C in phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.0. Excess dye was removed by at least 2-h incubation with Bio-Beads (Bio-Rad) and then overnight dialysis into storage buffers, including two buffer exchanges.

Optical Trapping Assays

To make neutravidin-coated beads for use in these experiments, biotinylated polystyrene beads (1 μm diameter, Molecular Probes) were rinsed three times in phosphate-buffered saline and then incubated for 1 h at room temperature with 2.5 mg/ml neutravidin (Molecular Probes). The beads were then incubated with 10 mg/ml BSA or TMR/BSA for 30 s before being rinsed 10 times in AB with 1 mg/ml BSA to complete blocking and washing. All experiments were performed on a home-built optical trapping and multicolor fluorescence microscope. Four-input laminar flow chambers coupled with fluid reservoirs and valves were used in all trapping assays (45). All solutions were prepared in AB. Flow chambers were blocked with 1 mg/ml BSA. Reservoirs were loaded with solutions. Reservoir one was loaded with 4 μl of neutravidin-coated beads in 1 ml of observation buffer (AB plus 0.86 mg/ml glucose oxidase, 0.14 mg/ml catalase, 9 mg/ml glucose). Reservoir two was loaded with 1 μl of 10 μm F-actin diluted in 1 ml of observation buffer. Reservoir three was observation buffer only. Reservoir four contained a final concentration of 1 μm cross-linking protein in observation buffer for angular dependence assays and 0.1 μm cross-linking protein when making bundles for unzipping experiments. Solutions were allowed to flow through the flow chamber, creating four distinct lanes in the main channel. One to four beads were trapped in the first lane. The beads were transited through the actin channel where actin filaments were allowed to stick to the beads. The beads and actin were arranged into the desired geometry in the buffer only lane. Movie acquisition was started, and then the bead and actin structures were then moved into the cross-linking protein lane. Movies were recorded using Andor Luca and iXon cameras with epifluorescence illumination, at frame rates from 0.1 to 0.2 s per exposure. Data were analyzed using ImageJ movie processing and angle measurement tools.

Fluorescence and FRAP

Fascin-actin bundles were made by incubating 10 μm F-actin (10% biotin, 90% dark) with 4 μm labeled atto-647N-fascin in AB for 2 h. Flow cells were formed using double-sided tape to adhere 24 × 60-mm coverslips crosswise on the microscope slides. Chambers were loaded with neutravidin solution (0.5 mg/ml), incubated for 2 min, and then blocked with a 1 mg/ml BSA in AB for 10 min, before loading bundle solution (diluted to 0.5 μm actin in AB) and incubating for 2 min. Observation buffer was then loaded, and the slide was placed on the microscope. Solution changes were performed by spotting solutions at the opening of the flow chamber and wicking them through with filter paper. Before each assay, the chamber was washed with an additional observation buffer wash to remove any free fascin from solution. FRAP was performed by closing down the field iris until only the area to be bleached was visible and then increasing the laser power for the bleaching step. Optics were restored to observation settings and movies were recorded. Cross-linking protein washes were performed using 3 μm protein in observation buffer.

RESULTS

We set out to determine whether α-actinin and fascin could bind filaments in any orientation presented or if they would only form cross-links when presented with filaments already arranged in a specific orientation. Actin geometries of desired specifications were arranged using an optical trapping microscope coupled to a flow chamber (Fig. 1C) (45). Once the desired geometries (Fig. 1, d–I) were constructed, they were moved into a flow lane containing 1 μm cross-linking protein (Fig. 1C). Cross-linking events were counted using a binary link/no link metric. Movies were acquired at rates of 5–10 frames/s. Filaments had to remain together in a fixed orientation for at least three consecutive frames for a cross-linking event to be counted. When the filament polarity was known or could be deduced, events were recorded with specific angles. When the polarity was not known, binding events were categorized in pairs that contain both possible angles (e.g. 45/135°). The binding profile from these data is the angular dependence of binding. No cross-linking events or filament self-association was ever observed in the absence of cross-linking protein.

α-Actinin Is a Promiscuous, Flexible Cross-linker

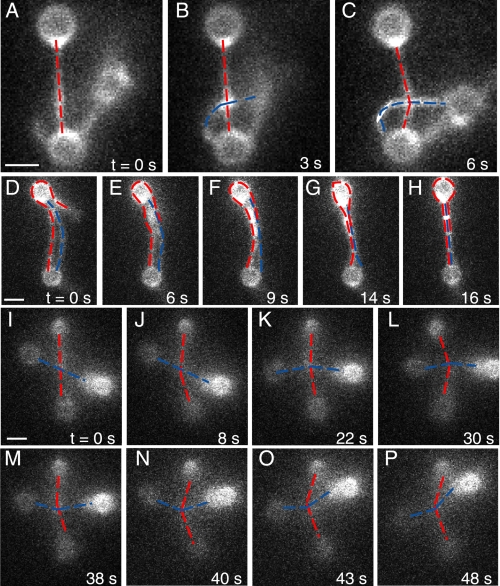

α-Actinin proved to be a promiscuous cross-linker (Fig. 2 and Table 1). When parallel or anti-parallel filaments were tested, the filaments formed many cross-links, like a zipper closing, forming bundles (Fig. 2, d--H). When pairs of filaments crossed over a range of angles from 16 to 165° were probed, in all cases a single point of attachment was observed. These cross-links formed within a few seconds of entering the cross-linking channel, but the time scale cannot be precisely quantified with this system.

FIGURE 2.

α-Actinin is a flexible cross-linker that cross-links actin in all orientations examined. A–C, gallery shows the formation of a single cross-link by α-actinin at a 90° cross of two actin filaments on three beads (supplemental Movie S1). d--H, α-actinin bundles aligned filaments. The filament marked in red is strung between the two beads and wraps around the top bead. The blue filament is strung between the two beads. All three filament segments bind into a tight bundle. This arrangement necessitates the formation of anti-parallel cross-links and could include parallel cross-links as well (supplemental Movie S2). I–P, α-actinin cross-link is stable, remaining bound while the link is rotated and pulled in various directions. Gallery shows a 48-s range. This link was observed for more than 3 min before the complex fell out of the optical traps (supplemental Movie S3). Scale bar in all figures equals 1 μm.

TABLE 1.

α-Actinin binds in all orientations tested

α-Actinin formed cross-links in all geometries. The 1st 3 rows of the table show orientations where the filaments were aligned. In these cases, the filaments were linked along the length of the filaments forming bundles. The last 3 rows show that crossed filaments always cross-linked. The last column shows the probability, using a binomial cumulative distribution function, that only one orientation was sampled during the course of the experiments reported in each row. We did not attempt to control the chirality of filament crosses (e.g. 90° with horizontal filament crossed over the vertical or under the vertical) and the probability calculation does not take into account potential chiral differences.

| Angle (degrees) | Orientation | Orientation Fig. reference | Crosses tested | Crosses that bound | Probability of sampling only one conformation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0/180 | One bead, two filaments | 1I | 6 | 6 | 0.0313 |

| 180 | One bead, wrapped filament | 1G | 11 | 11 | 1 |

| 0/180 | Four beads, two filaments | 1F | 5 | 5 | 0.0625 |

| 16–45/36–165 | Four beads, two crossed filaments | 1D | 7 | 7 | 0.0156 |

| 46–89/91–135 | Four beads, two crossed filaments | 1D | 3 | 3 | 0.25 |

| 90 | Four beads, two crossed filaments | 1D | 9 | 9 | 1 |

Once formed, these cross-links were very stable. They were never seen to dissociate during the time of observation (2–4 min for single points of attachment in the presence of α-actinin). The stability of single links may be explained in two ways. One, it is possible there are two or more cross-linking proteins present at the linkage site (supplemental Fig. S2). Two, because the links are under some load, they may not be able to dissociate in the same manner as unloaded links (as suggested by Ferrer et al. (40)). Interestingly, these links remained bound even when the orientation of the filaments was changed, and the linkage was rotated (Fig. 2, I–P). This implies that the α-actinin remains flexible even while engaged in an active cross-link. Our observation period ended when the actin filaments broke or photobleached or when the structure fell out of the optical traps.

Fascin Selectively Cross-links Parallel Filaments

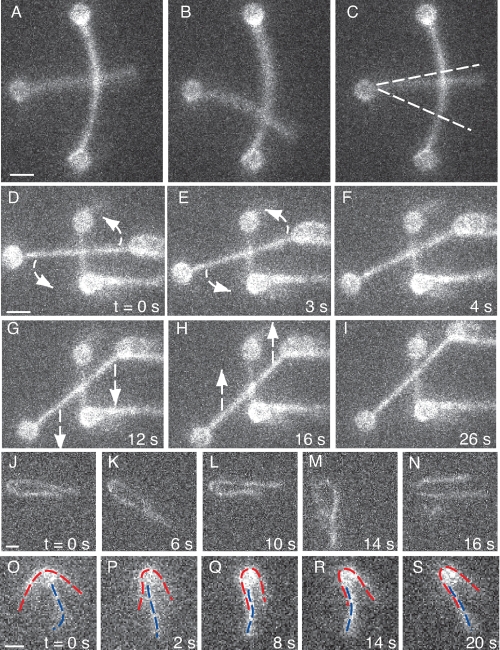

In contrast to α-actinin, fascin is an orientation-selective cross-linker. Fascin only cross-linked filaments when they were arranged in a parallel orientation (Fig. 3 and Table 2). Anti-parallel filaments (Fig. 3, J–N) and crossed filaments (Fig. 3, A–I) showed no sign of fascin-induced linkage. We estimate that transient cross-links, if present, should have been observed in our system. Fascin has been shown by FRAP to dissociate at a rate of once per 6 s (0.12/s) (38), 20-fold slower than our detection threshold. Therefore, we are quite confident that we recorded most of the events that took place. When linkages were observed using the parallel orientation (Fig. 3, O–S), the filaments invariably formed bundled sections (multiple links) and remained bound. Based on these data, we believe it is unlikely that fascin will form stable cross-links between two filaments oriented in anti-parallel or crossed orientations.

FIGURE 3.

Fascin only cross-links actin when filaments are arranged in a parallel orientation. A–C, fascin does not bind in a crossed orientation near 90°. The free end of a filament with only one end bound to a bead was allowed to freely scan over an anchored filament. No binding events were observed. Because of the bend in the filament with both ends anchored to beads, all crossing was near 90° (±10°). Approximately 2.5 μm length of the anchored filament was probed by the free filament end (∼900 potential binding sites). At 1 μm fascin concentration, ∼50% of the available fascin-binding sites should be filled, so the scanning filament should have found a viable binding site if the orientation of the filaments was conducive to binding. Dotted lines indicate the range over which the free filament scanned (supplemental Movie S4). d–I, a pair of crossed filaments was arranged and scanned. No binding events were observed. This pair of filaments was tested over a range of ∼100° and scanned over a 1.5 μm distance at ∼15° increments (supplemental Movie S5). J–N, fascin does not bind in an anti-parallel orientation as shown by this filament wrapped around a nonfluorescent bead. Filament ends diffused together but never remained coupled (supplemental Movie S6). O–S, one filament (red) wraps around a bead that has a second filament (blue) attached. One side of the red filament bundles with the blue filament, but the other does not. This behavior is explained by polarity selection. Coupled with the results from J–N, we can determine that fascin will bind parallel but not anti-parallel filaments (supplemental Movie S7).

TABLE 2.

Fascin binding is selective for parallel actin filaments

Fascin only binds to filaments oriented in a parallel orientation (0°). Crossed filaments (16–165°) form no cross-links. Filaments oriented in an anti-parallel orientation do not form cross-links. When two beads are attached to the same filament, we observed 8 of 18 tests forming cross-links. In this orientation, approximately 50% of the trials should have filaments oriented in a parallel manner and 50% in an anti-parallel orientation. When two polarity-labeled filaments were allowed to interact in a parallel orientation, they were observed to form cross-links and bundles. From these results, we determined that fascin will only form cross-links when filaments are oriented in a parallel orientation. For crosses of 16–165°, a scan of one angle was performed, and because no cross-links were observed, a new angle was selected, and another scan was performed with that same filament pair. The notation 4/4 in the crosses tested field mean four crosses were formed, and each of those crosses was tested in both orientations represented in that bin on the table. The same meaning is intended for the 5/5 notation. NA, not applicable.

| Angle (degrees) | Orientation | Orientation Fig. reference | Crosses tested | Crosses that bound | Probability of sampling only one conformation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Polarity labeled, four bead, two filaments | 1F | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 180 | Polarity labeled, four beads, two filaments | 1F | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| 0/180 | One bead, two filaments | 1I | 18 | 8 | 7.6 × 10−6 |

| 180 | One bead, wrapped filament | 1G | 9 | 0 | 1 |

| 16–45/36–165 | Four beads, two crossed filaments | 1D | 4/4 | 0 | NA, four crosses rotated through range |

| 46–89/91–135 | Four beads, two crossed filaments | 1D | 5/5 | 0 | NA, five crosses rotated through range |

| 90 | Four beads, two crossed filaments | 1D | 5 | 0 | 1 |

To support the polarity distinction observed in the fascin system, we performed a series of assays using polarity-labeled actin (Table 2). Rapid photobleaching of available far red phalloidin labels (Alexa-633) made this a challenging experiment and limited the number of successful trials. In those instances, the orientation of the filaments was recorded as soon as a filament was attached to a bead. The filaments were dramatically bleached before final geometries were attained. Tension between beads was used to establish intact filaments and the formation of cross-links. Filaments arranged in a polar fashion rapidly formed bundles, whereas the filament pairs tested in an anti-parallel orientation did not form a bundle after approximately 1 min of observation.

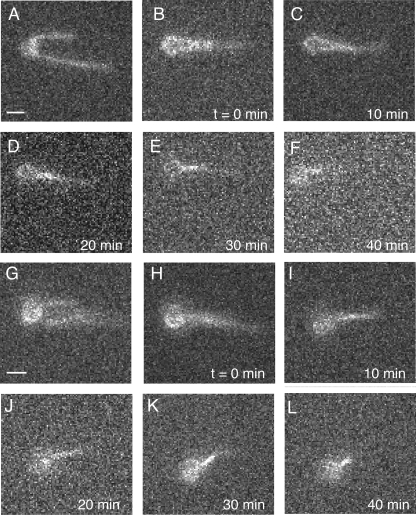

Two-filament Bundles Are Not Observed to Dissociate

Next we assessed the unzipping behavior of these two-filament bundles. Bundles were formed by attaching two filaments to a single bead and then allowing them to cross-link in the presence of 0.1 μm α-actinin or 0.1 μm fascin. After being formed, bundles were moved into a flow lane containing only buffer; flow in all other lanes was stopped, and movies were recorded. After 40 min of observation under continuous buffer flow, neither the fascin nor α-actinin bundles were observed to dissociate (Fig. 4). This result was surprising given previous measurements of fascin dissociation rate (0.12/s) (38) and α-actinin actin binding domain dissociation rate (0.66/s) (27), and this led us to further investigate the dynamics of the cross-linking proteins in bundles.

FIGURE 4.

Bundles do not dissociate even over long time scales. A–F, one long filament was attached in the middle to a bead, and the ends were allowed to form a bundle in the presence of 0.1 μm α-actinin. After bundle formation, the bundle was moved into the buffer lane, and all other flow lanes were turned off. The bundle was observed periodically over 40 min. The filaments were never observed to separate (supplemental Movie S8) This experiment was replicated six times with the same results, using bundles derived from one to three filaments (two to three lengths of filaments incorporated into the bundle). G–L, two filaments were attached to a bead, and the same experiment was performed using 0.1 μm fascin. As with α-actinin, the fascin bundles were extremely stable, showing no dissociation over 40-min observations. This experiment was replicated six times using two and three filaments in the bundle (supplemental Movie S9). Additional material on this experiment is found in supplemental Figs. S3 and S4 and supplemental Movies S10–S13.

Dynamics of Fascin Within Bundles

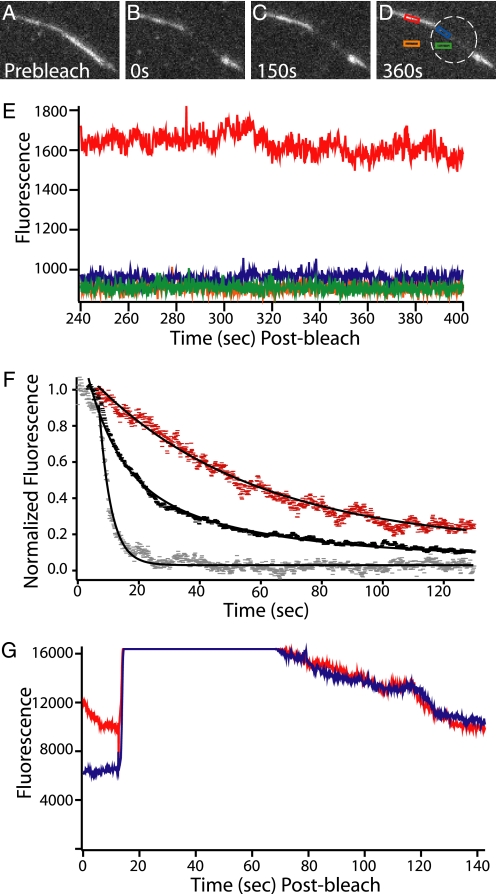

A series of FRAP and fluorescence decay experiments revealed that fascin in bundles is stable and does not dissociate from the bundles unless competed away. Unfortunately, we were unable to prepare a functional, fluorescent-labeled α-actinin protein, so we restrict our discussion of dissociation to fascin.

First, bundles of dark biotinylated actin filaments and fluorescent atto-647N-fascin were made and washed into the neutravidin-coated chamber (Fig. 5A). Two chamber volumes of buffer was then flowed in the chamber to remove free fascin from solution. The fascin dissociation rate from the bundles was extremely slow, indistinguishable from background bleaching (Fig. 5E). When a section of a bundle was bleached with no fascin in solution, no recovery was seen, and the boundary between bleached and unbleached areas remained sharp, suggesting that the bound fascin does not appreciably redistribute within the bundle (Fig. 5, A–E). This corroborates our results from the unbundling assay in the optical trap.

FIGURE 5.

Fluorescence decay and FRAP of labeled fascin in bundles shows the fascin population is stable unless a competitor is added. A–D, bundle of dark actin held together by fluorescent atto-647-fascin (labeled on exposed cysteines using maleimide chemistry, measured 0.95 dyes/fascin) is bleached and then observed in a series of movies over 400 s. Before bleaching, the flow cell was rinsed with buffer to remove free fascin from solution. The boundary between the bleached and unbleached regions of the bundle remained sharp and the signal from the unbleached portion of the bundle remained nearly constant. The white ring indicates the zone of bleaching. Low observational laser power was used to facilitate the long acquisition time by minimizing photobleaching. E, fascin in the bundle is stable in the absence of cross-linker in solution. The graph shows the fluorescence decay profile of the four highlighted regions from D, recorded during the final movie of this observation. The fluorescence of the bundle (red) remains stable and higher than the other three regions. The green curve is background in the bleached zone; orange is the background outside of the bleached zone, and blue is the bundle in the bleached zone. F, fascin in bundles can be competed away. A series of buffer wash experiments using bundles similar to those in A–D were performed. In all cases the bundles had been rinsed with buffer to remove free fascin from solution before data were recorded. All data points are background subtracted and then normalized so that a value of 1 corresponded to the average value of the first 25 data points after the wash was initiated. When the bundles were washed with buffer only (red), a slow decay (0.019 ± 0.003 s−1, S.E.) was seen in the fluorescent signal. This corresponds to the photobleaching rate at the laser powers used in these experiments. When 3 μm unlabeled fascin (black) was washed in a double exponential decay was observed. The faster rate corresponds to fascin being displaced from the bundle (0.10 ± 0.007 s−1, S.E.). This value closely matches that of Aratyn et al. (38), who reported a decay rate of 0.12 s−1. The slower rate (0.023 ± 0.002 s−1, S.E.) corresponds to photobleaching. When 3 μm unlabeled α-actinin was washed in a rapid single exponential decay was observed (0.254 ± 0.004 s−1, S.E.). This is even more rapid than the decay observed with the addition of fascin. This shows that the presence of a competitive agent causes rapid cross-linker turnover. G, fascin replacement is uniform and complete across the entire bundle. With no fascin in solution, a region of a bundle made with fluorescent fascin was bleached. Blue indicates the area of the bundle that was bleached, and red indicates the area that was not bleached. After bleaching, a significant difference in signal between the two curves is observed. Next, 3 μm fluorescent fascin was washed into the chamber (around the 20-s mark, where signal rises to saturation). It was allowed to incubate for 30 s and then was washed out with buffer. The wash is completed, and the signal drops to resolvable levels after approximately an additional 20 s. At this point, the bundle inside and outside the bleach zone have the same fluorescence. This confirms that free fascin can incorporate completely and evenly into the bundle.

Because cross-linking proteins must bind to two filaments to form a link, we hypothesized that a high avidity might be dominating the behavior such that the multiple binding sites prevented complete dissociation. To test this, bundles constructed of directly labeled fascin were rinsed with buffer containing unlabeled fascin. The fluorescence of the bundles was rapidly lost (decay of 0.10 s−1) (Fig. 5F), matching closely the in vivo and in vitro results reported by Aratyn et al. (38) in which all experiments had free fascin in the cytoplasm or solution. Thus, cross-links can be rapidly removed by competition.

The fascin replacement rate along the bundles is uniform (Fig. 5G). With no fascin in solution, a section of a bundle was bleached yielding a difference in fluorescence signal between the bleached and unbleached section. Labeled fascin was washed into a chamber and allowed to incubate for 30 s. The chamber was then washed with buffer to remove free fascin. After the wash, the fluorescence intensity on the bundle inside and outside of the bleach spot was identical. This confirms that when fascin is present in solution, the replacement of fascin in the bundle takes place rapidly, further indicating that the presence of fascin in solution is critical for bundle cross-link turnover.

Interestingly, fascin is removed by other competitive agents. Bundles containing fluorescent fascin lost fluorescence extremely rapidly (0.254 s−1) when unlabeled α-actinin was introduced (Fig. 5F).

DISCUSSION

We have directly observed that α-actinin is a promiscuous, flexible cross-linker with the ability to cross-link all orientations of actin filaments. Our data support a model where the actin binding domains on each end of the α-actinin dimer freely rotate with respect to each other, whether through flexible linker regions or a twist in the dimerization domain itself, and can bind any filament at any orientation that presents binding sites within a given interaction radius. This conclusion is well supported by other work. The diverse role of α-actinin in forming meshworks and bundles is well studied in vitro. Electron microscopy data have shown α-actinin has the ability to link filaments into parallel and anti-parallel bundles, as well as to side binding with both binding domains attached to the same filament (32). Rheology data have shown that it can form homogeneous networks (evenly distributed meshworks) (26, 46). Although crystallization of full-length α-actinin has proved difficult, electron microscopy coupled with partial crystal structures has yielded a great deal of insight into the structure of the functional dimer and how this molecule might function and supports the idea that the binding domains can rotate with respect to each other (31, 47–49).

We have also directly observed the binding behavior of fascin, which is a highly selective molecule. Fascin cross-linking is limited to filaments that have been arranged in a parallel orientation. This is consistent with known roles of fascin in formation of filopodial bundles and with in vitro observations (12, 17).

The observation that no unbundling occurs in the absence of free cross-linking protein was surprising but not unprecedented. Fis, a DNA compaction and looping protein from Escherichia coli, has been shown to condense (cross-link) DNA and remain stably bound in a buffer in the absence of protein for 20 min, but in the presence of competitive factors, it can be partially competed off of the DNA (50). Our competition assays show that similar behaviors may be present in both systems.

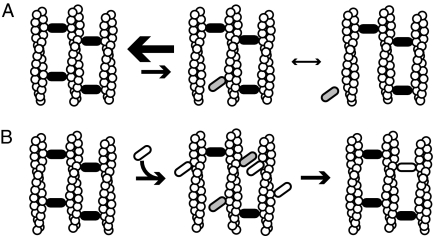

These results led us to the following model. Fascin that is involved in cross-linking (one fascin molecule interacting with two filaments) is very stable in the absence of competing free fascin. In tight fascin bundles, filaments are arranged in in-register arrays that are very stiff on short length scales. When one fascin-binding site releases from an actin filament, the actin- binding site cannot diffuse away. For complete dissociation to occur, the second binding site on the fascin must release before the first one rebinds. Our results indicate that when a cross-linking fascin releases one binding site, it will rebind that site before the second site releases, leading to stable bundles when no fascin is in solution. This indicates that the on rate of the free actin binding domain of the singly bound fascin is faster than the off rate of the bound actin binding domain. We propose a model where the fascin molecule toggles back and forth between single and double bound states, with very rare dissociations (Fig. 6A).

FIGURE 6.

Models of bundle formation and dynamics. A, bundles are stable in the absence of competitive agents. Cross-linking proteins that are bound to two filaments (black ovals) stabilize filament bundles. These proteins can toggle to a state (gray ovals) where they are only bound to a single filament. Because the actin site is restrained, the single bound cross-linker can readily rebind the second filament. This rebinding rate is faster than the dissociation rate in the single bound state, yielding bundles that are very stable. B, when a competitive agent (white oval) is added to a stable bundle it can occupy actin sites near single bound cross-linkers, preventing their rebinding. This leads to dissociation of the endogenous cross-linker and either replacement with the exogenous agent (shown) or dissociation of both factors (not shown). If cross-linking protein is abundant in solution, there is a constant exchange of proteins in the bundle as shown by previous FRAP experiments.

When a competitive agent, such as free fascin molecules, is present in solution, cross-linking fascin can be rapidly displaced from the bundle. When a bound fascin molecule enters the singly bound state, free protein in solution can compete for the transiently available binding site. Fascin that is bound to a single actin filament with no available second binding site (bound on the surface of the bundle or where another molecule is occupying the actin site) dissociates rapidly. This explains how all the fluorescent fascin is lost from bundles when dark fascin is introduced. Furthermore, when two molecules compete for the same location in a bundle, as soon as one molecule dissociates the other can form a link, in many cases leading to cross-linker replacement or turnover (Fig. 6B). We also observed that excess α-actinin in solution displaced fascin in bundles more rapidly than excess fascin in the bundles. It is possible that this rate difference is due to α-actinin having a higher affinity for actin than fascin, thus being a better competitor. It is also possible that, because α-actinin is a much longer molecule than fascin, α-actinin opens up fascin bundles as it integrates preventing singly bound fascin molecules from rebinding and causing a more rapid loss to solution.

Our fascin exchange results closely match previously reported data, which were collected in the presence of free fascin in solution (in vitro and in vivo) (38, 39). Our model begins to explain how bundles can be both stable and dynamic, allowing filopodia to form and bend without breaking, being overly rigid or overly soft.

Current Models of Actin Structure Formation

The orientation of actin filaments prior to structure nucleation is overlooked in most current models of cytoskeletal structure formation. The implicit assumptions are that the filaments grow in the correct orientation, align by thermal motion prior to assembly, and/or align after cross-links form. Here, we have shown that different cross-linking proteins have different angular dependence of binding and that filament orientation is important for the earliest stages of structure formation and stabilization.

In the case of α-actinin, cross-links can form regardless of the actin orientation, but those cross-links do not lock in an orientation. This has several ramifications for structure formation. α-Actinin can bind filaments if they are arranged correctly, or it can bind a pair of filaments and hold them in proximity to each other while a proper orientation is reached. Conversely, because it is so nonselective, it may form links that are not beneficial. This would indicate that some form of regulation is required to prevent aberrant structure formation when α-actinin is involved. α-Actinin is known to have many different binding partners (51), and non-muscle α-actinin is calcium-regulated (52), so it is reasonable to think active regulation likely prevents most aberrant activity.

Fascin is highly selective in its cross-linking behavior. Fascin localization in cells is mostly limited to filopodia and bundles that line the cell periphery. Based on our observations, these filaments must be aligned before fascin can stabilize the structures. This finding supports the convergent elongation model of filopodial formation presented by Borisy and co-workers (17), where filament ends come together and are linked by a filopodial tip complex into so-called λ precursors. Once the precursor forms, the filaments can grow and should be arranged in a parallel fashion, allowing fascin to bind. Other mechanisms may still prove valid. In cells there are also circumferential bundles that can cross each other in an anti-parallel orientation. These bundles may be realigned by some other means. For example, myosin X could cross-link the ends of the nascent bundles, leading to reorientation as they grow and the addition of fascin to stabilize a newly forming and growing filopodia (18, 19). Fascin is known to have its binding behavior deactivated by phosphorylation (39); however, the selective binding of fascin may aid in preventing fascin from forming unwanted structures, limiting the amount of effort the cell must expend to regulate it.

There are many different actin cross-linking proteins. Some are found exclusively in bundles (e.g. fascin, fimbrin, and espin), others almost exclusively in meshworks (e.g. filamin), and others in both types of structures (e.g. α-actinin). Our work shows that this selectivity may be due to inherent properties of the cross-linking proteins rather than, or in conjunction with, external localization and organizational cues. Understanding the properties of cross-linking proteins will help us place constraints on the behavior of the cytoskeleton, leading to a more complete understanding of cytoskeletal assembly and organization. The interactions probed here are complex, and many questions still remain. It is possible that filament tension or twist may change cross-link behavior, as might other interacting proteins. In this study, we have directly observed the behavior of two cross-linking proteins and established a road map for further testing the behavior of these types of proteins.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Gary Borisy for providing the fascin cDNA and Yvonne Aratyn for helpful discussions.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant GM078450 (to R. S. R.). This work was also supported by an American Heart Association predoctoral fellowship (to D. S. C.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S4 and Movies S1–S13.

The fascin crystal structure is available through the RCSB Protein Data Bank, code 1DFC.

- TMR

- tetramethylrhodamine

- FRAP

- fluorescence recovery after photobleaching

- BSA

- bovine serum albumin.

REFERENCES

- 1.Otto J. J., Kane R. E., Bryan J. (1979) Cell 17, 285–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heggeness M. H., Wang K., Singer S. J. (1977) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 74, 3883–3887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kane R. E. (1976) J. Cell Biol. 71, 704–714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kane R. E. (1975) J. Cell Biol. 66, 305–315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goll D. E., Mommaerts W. F., Reedy M. K., Seraydarian K. (1969) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 175, 174–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maruyama K., Ebashi S. (1965) J. Biochem. 58, 13–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ebashi S., Maruyama K. (1965) J. Biochem. 58, 20–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ebashi S., Ebashi F. (1965) J. Biochem. 58, 7–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rafelski S. M., Theriot J. A. (2004) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 73, 209–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pellegrin S., Mellor H. (2007) J. Cell Sci. 120, 3491–3499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Faix J., Rottner K. (2006) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 18, 18–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adams J. C. (2004) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 16, 590–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall A. (2009) Cancer Metastasis Rev. 28, 5–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bamburg J. R., Bloom G. S. (2009) Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 66, 635–649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kee A. J., Hardeman E. C. (2008) Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 644, 143–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Le Clainche C., Carlier M. F. (2008) Physiol. Rev. 88, 489–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Svitkina T. M., Bulanova E. A., Chaga O. Y., Vignjevic D. M., Kojima S., Vasiliev J. M., Borisy G. G. (2003) J. Cell Biol. 160, 409–421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tokuo H., Mabuchi K., Ikebe M. (2007) J. Cell Biol. 179, 229–238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bohil A. B., Robertson B. W., Cheney R. E. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 12411–12416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hotulainen P., Lappalainen P. (2006) J. Cell Biol. 173, 383–394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Svitkina T. M., Verkhovsky A. B., McQuade K. M., Borisy G. G. (1997) J. Cell Biol. 139, 397–415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Urban E., Jacob S., Nemethova M., Resch G. P., Small J. V. (2010) Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 429–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Naumanen P., Lappalainen P., Hotulainen P. (2008) J. Microsc. 231, 446–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Broderick M. J., Winder S. J. (2005) Adv. Protein Chem. 70, 203–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsudaira P. (1991) Trends Biochem. Sci. 16, 87–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wachsstock D. H., Schwartz W. H., Pollard T. D. (1993) Biophys. J. 65, 205–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wachsstock D. H., Schwarz W. H., Pollard T. D. (1994) Biophys. J. 66, 801–809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pelletier O., Pokidysheva E., Hirst L. S., Bouxsein N., Li Y., Safinya C. R. (2003) Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 148102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu J., Tseng Y., Wirtz D. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 35886–35892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taylor K. A., Taylor D. W., Schachat F. (2000) J. Cell Biol. 149, 635–646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu J., Taylor D. W., Taylor K. A. (2004) J. Mol. Biol. 338, 115–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hampton C. M., Taylor D. W., Taylor K. A. (2007) J. Mol. Biol. 368, 92–104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sedeh R. S., Fedorov A. A., Fedorov E. V., Ono S., Matsumura F., Almo S. C., Bathe M. (2010) J. Mol. Biol. 400, 589–604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen L., Yang S., Jakoncic J., Zhang J. J., Huang X. Y. (2010) Nature 464, 1062–1066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kureishy N., Sapountzi V., Prag S., Anilkumar N., Adams J. C. (2002) BioEssays 24, 350–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmoller K. M., Lieleg O., Bausch A. R. (2008) Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 118102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Esue O., Harris E. S., Higgs H. N., Wirtz D. (2008) J. Mol. Biol. 384, 324–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aratyn Y. S., Schaus T. E., Taylor E. W., Borisy G. G. (2007) Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 3928–3940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vignjevic D., Kojima S., Aratyn Y., Danciu O., Svitkina T., Borisy G. G. (2006) J. Cell Biol. 174, 863–875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ferrer J. M., Lee H., Chen J., Pelz B., Nakamura F., Kamm R. D., Lang M. J. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 9221–9226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miyata H., Yasuda R., Kinosita K. (1996) BBA-Gen Subjects 1290, 83–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pardee J. D., Spudich J. A. (1982) Methods Enzymol. 85, 164–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vignjevic D., Peloquin J., Borisy G. G. (2006) Methods Enzymol. 406, 727–739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Feramisco J. R., Burridge K. (1980) J. Biol. Chem. 255, 1194–1199 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Courson D. S., Rock R. S. (2009) PLoS One 4, e6479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tseng Y., Fedorov E., McCaffery J. M., Almo S. C., Wirtz D. (2001) J. Mol. Biol. 310, 351–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ylänne J., Scheffzek K., Young P., Saraste M. (2001) Structure 9, 597–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kuboniwa H., Tjandra N., Grzesiek S., Ren H., Klee C. B., Bax A. (1995) Nat. Struct. Biol. 2, 768–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Atkinson R. A., Joseph C., Kelly G., Muskett F. W., Frenkiel T. A., Nietlispach D., Pastore A. (2001) Nat. Struct. Biol. 8, 853–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Skoko D., Yoo D., Bai H., Schnurr B., Yan J., McLeod S. M., Marko J. F., Johnson R. C. (2006) J. Mol. Biol. 364, 777–798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sjöblom B., Salmazo A., Djinoviæ-Carugo K. (2008) Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65, 2688–2701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Burridge K., Feramisco J. R. (1981) Nature 294, 565–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.