Abstract

Protein kinase C (PKC) is considered crucial for hormonal Na+/H+ exchanger (NHE1) activation because phorbol esters (PEs) strongly activate NHE1. However, here we report that rather than PKC, direct binding of PEs/diacylglycerol to the NHE1 lipid-interacting domain (LID) and the subsequent tighter association of LID with the plasma membrane mainly underlies NHE1 activation. We show that (i) PEs directly interact with the LID of NHE1 in vitro, (ii) like PKC, green fluorescent protein (GFP)-labeled LID translocates to the plasma membrane in response to PEs and receptor agonists, (iii) LID mutations markedly inhibit these interactions and PE/receptor agonist-induced NHE1 activation, and (iv) PKC inhibitors ineffectively block NHE1 activation, except staurosporin, which itself inhibits NHE1 via LID. Thus, we propose a PKC-independent mechanism of NHE1 regulation via a PE-binding motif previously unrecognized.

Keywords: Cell pH, Membrane Lipids, Phorbol Esters, Protein Kinase C (PKC), Sodium Proton Exchange, Diacylglycerol, Hormone Receptors

Introduction

Tumor-promoting phorbol esters (PEs)2 have been used to validate the involvement of protein kinase C (PKC) in the functions of many proteins and in cellular processes (1, 2). The ubiquitous Na+/H+ exchanger (NHE1 isoform) is a well-documented PE-activated membrane protein (3–5) that has long been believed to be activated via PKC (6). NHE1 catalyzes electroneutral Na+/H+ exchange and is an important regulator of intracellular pH (pHi), Na+ concentration, and cell volume (6–10). NHE1 is activated in response to various stimuli, including hormones, growth factors, and mechanical stress, and thereby optimizing the intracellular ionic environment for many cellular functions including cell proliferation, cell migration, and volume regulation (6–10). Furthermore, this activation is also thought to be involved in the pathogenesis of diseases, such as cancer and heart failure (11–13). Regulation of NHE1 is thought to occur through the interaction of multiple signaling molecules with the carboxyl (C)-terminal cytoplasmic domain of NHE1, their post-translational modifications, and subsequent conformational changes in the amino (N)-terminal transmembrane domain responsible for catalyzing the Na+/H+ exchange reaction (6, 10) (see Fig. 1A for membrane topology). Furthermore, this regulation is attributable to a change in the affinity for intracellular H+ (6, 14, 15). Of the signaling molecules, calcineurin B homologous protein 1 (CHP1, a ubiquitous isoform of CHPs) was suggested to play an essential role in maintaining the structure/function of NHE1 as an obligatory subunit (16, 17). However, neither NHE1 nor CHP1 is phosphorylated by PKC in vitro.3 Thus, at present, conclusive evidence for PKC involvement and the detailed molecular mechanism underlying NHE1 activation remain elusive.

FIGURE 1.

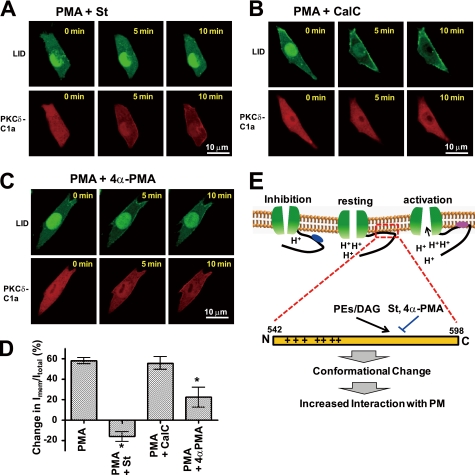

Plasma membrane translocation of LID. A, topology model of NHE1 and amino acid sequence of LID. Positions of two mutant constructs (LI1 and LI2) are represented. Leu-562 and Ile-563 in LI1 and Leu-573 and Ile-574 in LI2 were replaced with two alanine residues. B, PMA (1 μm) facilitates translocation of GFP-labeled LID (GFP-WT-LID) to the plasma membrane, in a similar time course as mCherry-labeled PKCδ-C1a domain. Note that fluorescence signals detected in the nucleus decreased and accumulated in the plasma membrane. C, time courses for the accumulation of two fluorescent probes in the plasma membrane within the same cells. Means ± S.E. (n = 7). D, colocalization efficiency was analyzed for a cell in B before and 10 min after PMA addition. High Pierson's coefficient (0.918) was observed with PMA. E, PMA does not promote the plasma membrane translocation of the 27 N-terminal residues of LID. OAG (100 μm) (F) and phenylephrine (Phe) (1 μm) (G) facilitate plasma membrane translocation of LID. In G, α1AR was stably expressed. H, PMA does not promote plasma membrane translocation of two LID mutants.

We predicted that NHE1 is activated through PKC-independent mechanisms such as direct interaction with PE/diacylglycerol (DAG). The NHE1 region adjacent to the CHP-binding site (18, 19) was reported to bind phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), a membrane phospholipid, and to be critical for maintaining basal exchange activity (20, 21). Because this ∼60-residue region (Fig. 1A), which includes the PIP2-binding site, is also essential for hormonal NHE1 activation (6, 22, 23), we hypothesized that change in the interaction of this region (lipid-interacting domain, LID) with cell membranes may be critical for regulation of NHE1. Here, we investigated the biochemical properties of LID, and found that it contains a novel PE/DAG-binding domain, which plays a critical role in NHE1 regulation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Molecular Biology

The template plasmid carrying cDNA coding for the NHE1 human isoform with some unique restriction sites cloned into the pECE mammalian expression vector has been described previously (24). All the constructs were produced by a polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based strategy as described previously (24). In brief, PCR products generated using forward and reverse primers were inserted into the appropriate restriction sites of expression vectors. For construction of GFP- or mCherry-tagged wild-type and mutant LID, the cytoplasmic region (amino acids 542–598) of NHE1 was amplified by PCR using pECE constructs as templates and inserted into mammalian expression vectors, pEGFP-C1 or pmCherry-C1 (BD Biosciences Clontech, Palo Alto, CA), respectively. For construction of mCherry-PKCδ-C1a, PKCδ-C1a domain (amino acids 159–208) of cloned human PKCδ was amplified and inserted into pmCherry-C1 vector, and for construction of MARCKS-GFP, the entire coding region of cloned human MARCKS was inserted into pEGFP-N1 vector. The cDNA coding for mouse α1-adrenergic receptor was purchased from Invitrogen and cloned into the expression vector pT-REx-DEST30 (Invitrogen). GFP-labeled PLCδ-PH domain (25) was kindly provided by Dr. Tobias Meyer (Stanford University). The DNA sequences of the PCR fragments were confirmed using an Applied Biosystems Model 3130 autosequencer.

Confocal Microscopy

Exchanger-deficient PS120 cells (26) or PS120 cells stably expressing the wild-type NHE1 (our basic confocal observations described in this report did not differ across these two cell types) were co-transfected with GFP- or mCherry-labeled LID and other constructs for 6–8 h by Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, CA). Cells were trypsinized and plated onto glass-bottom 35-mm dishes. Fluorescent signals were observed by confocal microscopy with an Olympus Fluoview FV1000 confocal microscope 16–24 h after trypsinization. Various reagents such as PMA, OAG, and receptor agonists were added directly to dishes at 22–25 °C. Imaging data were usually taken each 15 or 30 s over 10–20 min. Changes in fluorescence intensities around plasma membranes (Figs. 1C and 6D) were analyzed using Image-Pro Plus software (Media Cybernetics Inc.). Fluorescence intensities in areas including plasma membranes and the whole cells were measured after these areas were selected by eye through an experimental series. Statistical analysis of colocalization was performed using software included with the confocal system (Fig. 1D). For co-transfection with mCherry-LID and GFP-PLCδ-PH (supplemental Figs. S5 and S6), line scanning of fluorescence intensity was performed at each cell, and fluorescence intensities in plasma membrane (Imem) and cytosol (Icyt) were measured using Image-Pro Plus software (Media Cybernetics, Inc.). The relative membrane-localization index (Imem − Icyt)/(Imem + Icyt) was calculated as described (25).

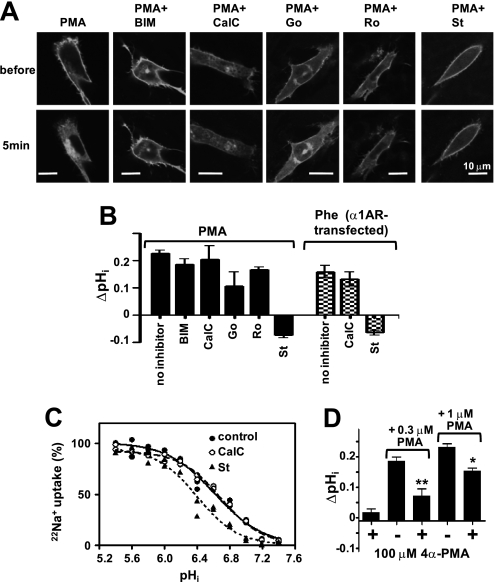

FIGURE 6.

Differential effects of lipophilic compounds on plasma membrane translocation of LID. A, staurosporin (St) inhibits PMA-induced LID (upper), but not PMA-induced PKCδ-C1a (lower), plasma membrane translocation. B, in contrast, calphostin C (CalC) does not inhibit PMA-induced LID (upper) translocation, but does inhibit PKCδ-C1a (lower) plasma membrane translocation. C, similar to staurosporin, 4α-PMA partly inhibits LID, but not PKCδ-C1a, plasma membrane translocation. D, relative change (%) in the fluorescence intensity of GFP-LID localized in the plasma membrane before and after (10 min) the addition of PMA and/or other reagents. Means ± S.E. (n = 5–7). *, p < 0.05 versus PMA alone. E, schematic models for NHE1 regulation (upper) with LID (lower). In the resting state, physiological NHE1 activity is preserved by interaction of LID with membrane phospholipids. Upon PE or receptor stimulation, PE/DAG binds to LID (probably its C-terminal portion), induces a conformational change to increase its affinity for membrane lipids, and thereby increases H+ affinity, leading to NHE1 activation. Mutations or interaction with some lipophilic compounds such as staurosporin reduce the affinity of LID to lipids, and thus inhibit NHE1 by decreasing H+ affinity.

Transfection of NHE1 Variants

In this experiment, we first stably transfected PS120 cells with mouse α1-adrenergic receptor under selection with G418. The cDNAs encoding the wild-type and mutant NHE1 variants were transfected by Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) into either PS120 or PS120 cells expressing α1-adrenergic receptor. Stable cell populations with Na+/H+ exchange activity were selected by acid-killing selection procedure as previously described (22).

Measurement of pHi Change

Extracellular stimuli-induced change in pHi was measured using the dual-excitation ratiometric pH-indicator BCECF/AM, as previously described (27). Briefly, cells expressing NHE1 variants were serum-depleted more than 2 h and loaded for 3 min with 0.3 μm BCECF/AM (Invitrogen) at room temperature in HEPES-buffered saline (HBS) containing: 140 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 2 mm CaCl2, 1 mm MgCl2, 5 mm glucose, and 20 mm Hepes/Tris (pH 7.0). Cells were then placed in a flow chamber connected to a perfusion system and superfused (0.6 ml/min) with HBS at 35 °C. We measured fluorescence at 510–530 nm with alternating excitations at 440 and 490 nm through a 505-nm dichroic reflector. Images were collected every 10–20 s using a cooled CCD camera (ORCA-ER, Hamamatsu photonics K.K., Japan) mounted on an inverted microscope (IX 71, Olympus) with a ×20 objective (UApo/340, Olympus), and processed with AQUACOSMOS software (Hamamatsu Photonics). Change in pHi was monitored by switching perfusions from normal medium to HBS containing various reagents. The resting pHi was calibrated as previously reported, using a high [K+] solution containing: 140 mm KCl, 2 mm CaCl2, 1 mm MgCl2, and 0.005 mm nigericin, and adjusted to various pH values ranging from 7.0 to 7.5. The change in pHi was also measured by the [14C]benzoic acid-equilibration method (22, 28). In this experiment, serum-depleted cells were preincubated for 30 min in bicarbonate-free HEPES-buffered DMEM (pH 7.0), and then incubated in the same medium containing [14C]benzoic acid (1 μCi/ml) and various agents for 15 min at 37 °C. In some experiments, cells were preincubated in HEPES-buffered DMEM containing wortmannin (10 μm) or PKC inhibitors (1 μm) and then switched to radioisotope medium containing PMA or phenylephrine and each inhibitor. After washing four times with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline, the cellular uptake of 14C-radioactivity was measured. The change in pHi was calculated according to the following equation: ΔpHi = log10 (14Cstim/14Cref), where 14Cstim and 14Cref are the intracellular 14C-radioactivity in the presence or absence of extracellular stimuli, respectively.

Measurement of 22Na+ Uptake

22Na+ uptake activity was measured by the K+/nigericin pHi clamp method as described previously (29). In brief, serum-depleted cells in 24-well plates were preincubated for 30 min at 37 °C in a Na+-free choline chloride/KCl medium containing: 20 mm HEPES/Tris (pH 7.4), 1.2–140 mm KCl (adjusted to total 140 mm by choline chloride), 2 mm CaCl2, 1 mm MgCl2, 5 mm glucose, and 0.005 mm nigericin. 22Na+ uptake was initiated by adding the same choline chloride/KCl solution containing 22NaCl (37 kBq/ml; final concentration, 1 mm), 1 mm ouabain, and 0.1 mm bumetanide. In some wells, the uptake solution contained 0.1 mm EIPA. One min later, cells were rapidly washed four times with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline to terminate 22Na+ uptake. pHi was calculated from [K+]i/[K+]o = [H+]i/[H+]o by assuming an intracellular [K+] of 120 mm. EIPA-inhibitable 22Na+ uptake was fitted by nonlinear least squares analysis to a Hill equation using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software Inc.), as shown in Equation 1,

where Vmax is the maximal uptake activity at very low pHi, K is the dissociation constant for H+, and n is the Hill coefficient. Data were plotted against pHi after normalization to the Vmax value. In some experiments, calphostin C (1 μm) or staurosporin (1 μm) was included throughout the preincubation and 22Na+ uptake periods. The data were normalized based on the protein concentration, which was measured using a bicinchoninic assay system (Pierce), using bovine serum albumin as a standard.

Measurement of PE Binding to Peptides

Binding of the fluorescent PE, SAPD, to peptides was quantified essentially as described previously (30) by measuring the fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) from tryptophans to the 2-(N-methylamino)benzoyl fluorophore attached at the 12-position of the phorbol moiety. The fluorescence intensities, obtained upon excitation of the tryptophan fluorophore at 280 nm, were determined using a spectrofluorimeter (Hitachi, FL4500) at 340 and 440 nm, corresponding to the emission maxima of tryptophan and SAPD, respectively. Peptides used in the experiments contain one tryptophan residue (Trp-546 of NHE1 for GP57 and GC20, Trp-663 of NHE1 for IL54). The solution (0.5 ml) consisted of 100 mm Tris/HCl, pH 7.4, 1 mm dithiothreitol, and 10 μm each peptide. In one experiment, liposomes (0.17 mg) consisting of 89% PC, 5% PS, 5% PA, and 1% PIP2 (weight %) was added to the cuvette. In some experiments, PMA, 4α-PMA, and OAG were added at the indicated concentrations. SAPD was titrated from stock solutions of the required concentration prepared from a Me2SO solution. To isolate the fluorescence signal resulting from FRET, the observed fluorescence intensities at each SAPD concentration were corrected for volume changes incurred during the titration procedure and normalized for the contribution from the direct excitation of the SAPD fluorophore according to Equation 2,

where Fi,+P and Fi,-P are the fluorescence intensities measured after each SAPD addition in the presence and absence of peptides, respectively, and F0,+P and F0,-P are the fluorescence intensities measured in the absence of SAPD in the presence and absence of peptides, respectively. The data were fitted by nonlinear least squares analysis to a Hill equation, as shown in Equation 3,

where Fmax and Fmin are the maximum and minimum corrected FRET signals, Kd is the binding constant for SAPD, cSAPD is the concentration of SAPD, and n is the Hill coefficient. In the presence of competitive chemicals, the data were fitted by the competitive binding equation, as shown by Equations 4 and 5,

where Kd,app is the apparent binding constant for SAPD in presence of competitors, C is the concentration of competitors (C) included in the cuvette, and Kd,C is the binding constant for C. After obtaining Kd,app by curve fitting, Kd,C was calculated using the Kd,SAPD value for SAPD.

Liposome Binding Assay of Peptides

For liposome preparation, a lipid mixture was made in chloroform and dried under nitrogen gas. Dried lipid mixture was agitated vigorously by vortexing in a buffer containing 100 mm Tris/HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mm dithiothreitol and sonicated for 1 min on ice in a bath-type sonicator. The resultant liposomes (0.2 mg) were mixed with peptides (140 μm) in the above Tris buffer (total volume 25 μl), incubated 10 min at room temperature, and centrifuged for 1 h at 100,000 × g. An aliquot of supernatant was subjected to PAGE with a 4–12% gradient gel (Invitrogen), together with a peptide mixture without centrifugation as a reference (total). Peptide bands were visualized by Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining and analyzed using Image-Pro Plus software (Media Cybernetics Inc.). The relative amount of peptides bound to liposomes was calculated by subtracting the amount of peptides remaining in the supernatant from the initial input as follows in Equation 6,

where Pt is the amount of total peptide without lipids, while Ps is the amount of peptide in the supernatant after centrifugation.

Reagents

In this study, the following N-terminally biotinylated peptides corresponding to the cytoplasmic regions of NHE1 were synthesized with >85% purity by GL Biochem Ltd.: GP57, GHHHWKDKLNRFNKKYVKKCLIAGERSKEPQLIAFYHKMEMKQAIELVESGGMGKIP; GP57-LI1, GHHHWKDKLNRFNKKYVKKCAAAGERSKEPQLIAFYHKMEMKQAIELVESGGMGKIP; GP57-LI2, GHHHWKDKLNRFNKKYVKKCLIAGERSKEPQAAAFYHKMEMKQAIELVESGGMGKIP; GC20, GHHHWKDKLNRFNKKYVKKC; and IL54, IRKILRNNLQKTRQRLRSYNRHTLVADPYEEAWNQMLLRRQKARQLEQKINNYL.

SAPD was purchased from Calbiochem, PMA and 4α-PMA from Sigma, OAG and other membrane lipids from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL), and 22NaCl and [14C]benzoic acid from PerkinElmer Life Science Inc. All other chemicals were of the highest purity available.

RESULTS

PEs Facilitate the Translocation of LID to the Plasma Membrane

We first determined whether PEs modulate the interaction of LID with the plasma membrane. Green fluorescent protein (GFP)-labeled LID expressed in fibroblasts (exchanger-deficient PS120 cells) targeted the plasma membrane and was located within cells (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA) greatly facilitated the translocation of LID to the plasma membrane (Fig. 1B and supplemental movie S1), which is also a characteristic of the PKC regulatory domain C1, where direct PE binding facilitates anionic membrane interactions (31). We also observed that GFP-LID and mCherry-PKCδ-C1a translocated to the plasma membrane in response to PMA over a similar time course within the same cells (Fig. 1, B and C) and finally colocalized in the plasma membrane (Fig. 1D). Such translocation did not occur in the case of the GFP-labeled 27 N-terminal residues (amino acids 542–568) of LID (Fig. 1E and supplemental movie S2), indicating that the C-terminal region is required for this phenomenon. Furthermore, LID accumulated in the plasma membrane in response to a membrane-permeable DAG analogue, 1-oleoyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycerol (OAG) (Fig. 1F and supplemental movie S3), thrombin (supplemental Fig. S1), and α1-adrenergic receptor (α1AR) agonist phenylephrine only when its receptor was expressed (Fig. 1G and supplemental movie S4). These results strongly suggest that PEs and the endogenous second-messenger DAG directly bind LID, thereby increasing the latter's affinity to plasma membranes.

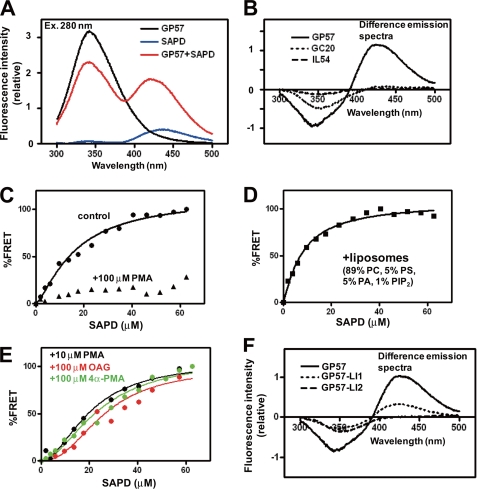

PEs Directly Bind LID in Vitro

To study the LID-PE interaction in vitro, we determined whether fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) occurs between the two. We synthesized a 57-residue peptide (GP57, Gly-542—Pro-598) spanning LID and examined whether FRET occurs between the tryptophan residue (Trp-546) of GP57 and the fluorescent PMA analogue, sapintoxin D (SAPD), as described previously (32). Inclusion of GP57 markedly increased the fluorescence intensity of SAPD with a slight blue-shift at the maximal emission wavelength of SAPD (440 nm), indicating clear FRET from tryptophan to the 2-(N-methylamino)benzoyl fluorophore of SAPD (Fig. 2A). FRET was not observed in the 20 N-terminal residues (GC20, Gly-542—Cys-561) of LID or in a control peptide (IL54, Ile-631—Leu-684 of NHE1) (Fig. 2B), and was greatly reduced by competition with 100 μm non-fluorescent PMA (Fig. 2C), suggesting that LID, particularly its 37 C-terminal residues, directly interacts with PEs. The affinity of GP57 for SAPD increased in the presence of liposomes (Kd, from 16.5 to 8.1 μm) (Fig. 2D and Table 1), suggesting that PEs may bind LID with higher affinity in membranes. Competition experiments revealed that OAG and even the inactive PE analogue 4α-PMA interact with LID, though with lower affinity (Fig. 2E and Table 1).

FIGURE 2.

PEs directly interact with LID in vitro. A, emission spectra at 280-nm excitation. FRET signals were observed between a tryptophan residue of peptide GP57 spanning LID (10 μm) and the fluorescent PE analogue SAPD (20 μm). B, difference emission spectra. In peptides GC20 and IL54, FRET signals (increment in fluorescence intensity at 440 nm) were not observed. C, FRET signals were considerably reduced in the presence of high concentrations of PMA (100 μm). D, liposomes increased SAPD affinity (see Table 1). E, PMA (10 μm), OAG (100 μm), and 4α-PMA (100 μm) decrease the apparent affinity of GP57 for SAPD, suggesting that they competitively interact with GP57. F, two mutations, particularly LI2, markedly reduced FRET signals.

TABLE 1.

Summary of FRET data obtained with GP57

Concentration dependence of SAPD on FRET signals was measured in the presence or absence of additional chemicals. The apparent dissociation constant Kd,app for SAPD was obtained by curve-fitting to a Hill equation as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Using the Kd,app value for SAPD in the absence of other chemicals, intrinsic Kd,C for the added competitors was calculated by assuming competition. Data are expressed as the best-fit values ± S.E.

| Added chemicals | Kd,app for SAPD | Calculated Kd,C for added competitors | Hill coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|

| μm | μm | ||

| None | 16.5 ± 3.1 | 1.36 ± 0.25 | |

| PMA (10 μm) | 24.0 ± 3.8 | 22.3 | 1.90 ± 0.42 |

| OAG (100 μm) | 26.0 ± 6.4 | 174.7 | 2.30 ± 0.81 |

| 4α-PMA (100 μm) | 24.3 ± 5.1 | 213.4 | 1.83 ± 0.49 |

| Liposomes | 8.07 ± 1.1 | 1.16 ± 0.16 |

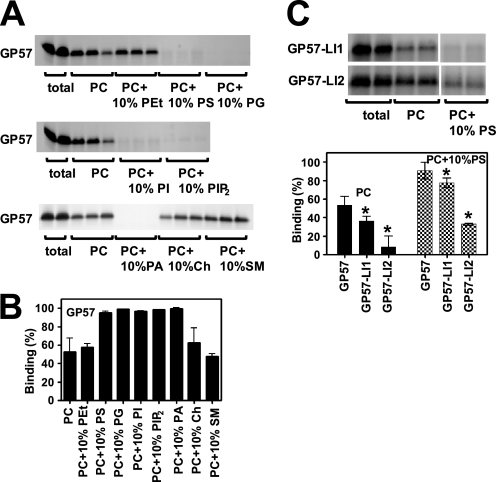

Besides these lipophilic compounds, we also examined the interaction of LID with membrane lipids by testing for direct binding. GP57 was incubated with liposomes consisting of various membrane lipids and then centrifuged; the unbound supernatant was analyzed using gel electrophoresis followed by Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining. We found that LID interacts with multiple membrane lipids, particularly, acidic phospholipids such as PIP2, phosphatidylserine (PS), and phosphatidic acid (PA) (Fig. 3, A and B). GP57 exhibited the following order of binding strength: PIP2 > PS, phosphatidylinositol (PI), PA > phosphatidylglycerol (PG) > phosphatidylcholine (PC) (supplemental Fig. S2).

FIGURE 3.

Multiple phospholipids can interact with LID. A, CBB-stained patterns of peptide GP57 spanning LID. Liposomes containing various lipids (weight %, adjusted to 100% with PC) were mixed with GP57 and centrifuged. Peptides before centrifugation (total) and an aliquot of each supernatant were subjected to PAGE. It was difficult to obtain the reliable data for interaction of DAG with peptides using this method because DAG inhibited the stable liposome formation. B, relative amount of GP57 bound to liposomes was calculated as described under “Experimental Procedures.” GP57 preferentially binds to acidic phospholipids such as PS, PG, PI, PIP2, and PA. Approximately 50% of peptides also bind to liposomes consisting of only PC under these conditions, suggesting that GP57 is capable of binding various membrane lipids. C, binding of peptides containing replaced residues to PC or PC + PS liposomes. CBB-stained patterns of peptides GP57-LI1 and GP57-LI2 from total input and the supernatant. Summarized data are represented in the lower panel. One amino acid substitution (GP57-LI2) markedly inhibited lipid binding, whereas another substitution (GP57-LI1) had a small inhibitory effect. Means ± S.D. (n = 3–4). *, p < 0.05 versus GP57.

Mutations in LID Abolish PE- and Hormone-induced Activation of NHE1

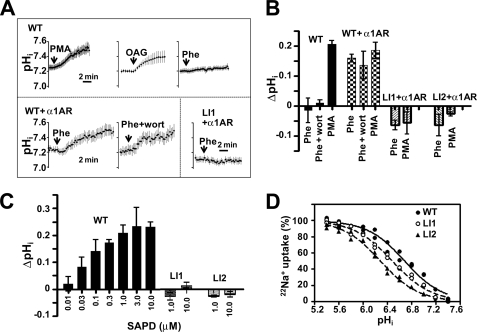

To study the role of LID in the regulation of NHE1 activity, we generated alanine-scanning mutations. Six mutations of conserved residues (Fig. 1A and supplemental Fig. S3) abrogated PE-promoted translocation of LID to the plasma membrane (Fig. 1H and supplemental Fig. S3 and movie S5), suggesting that the whole region of LID is important for membrane interaction. Mutations (particularly LI2, in which Leu-573 and Ile-574 were replaced with two alanine residues) also markedly inhibited the interaction of LID with PEs and phospholipids (Figs. 2F and 3C). Rapid and persistent cytoplasmic alkalinization, a consequence of increased cytosolic H+ affinity, has been used as a reliable indicator of NHE1 activation (3, 28). PMA, OAG, and SAPD induced such alkalinization in cells expressing wild-type full-length NHE1 (Fig. 4, A–C). PE-induced alkalinization occurred at relatively low concentrations (>0.03 μm SAPD) (Fig. 4C). Phenylephrine also induced alkalinization only in cells co-expressing α1ARs (Fig. 4, A and B). Interestingly, such alkalinization was dramatically inhibited by LI1, LI2 (Fig. 4, A–C), and other mutations (supplemental Fig. S3) incorporated into the entire NHE1 molecule, suggesting that the PE/DAG-promoted interaction of LID with the plasma membrane may be essential for NHE1 activation.

FIGURE 4.

Effect of LID mutation on NHE1 activity and regulation. A, change in pHi was measured using the pHi indicator BCECF-AM. PS120 cells were stably transfected with WT NHE1 (upper), WT + α1AR (lower left), or LI1 + α1AR (lower right). Cells were stimulated with PMA (1 μm), OAG (100 μm), or phenylephrine (Phe) (1 μm). In one experiment, cells were preincubated for 15 min with wortmannin (wort) (10 μm) and then stimulated with phenylephrine in the presence of wortmannin. Means ± S.E. (n > 20 cells). B, change in pHi 15 min after stimulation was measured using the [14C]benzoic acid equilibration method. Means ± S.D. (n = 3). C, SAPD-induced cytoplasmic alkalinization measured in cells expressing WT or mutant NHE1 by using the 14C-benzoic acid equilibration method. This alkalinization was abolished by mutations in LID. Means ± S.D. (n = 3). D, LID mutations induced an acidic shift of pHi dependence (decreased cytosolic H+ affinity).

Moreover, these mutations decreased cytosolic H+ affinity for NHE1 as shown by the acidic shift of pHi dependence (Fig. 4D and Table 2) as well as the maximal activity at acidic pHi (supplemental Fig. S4), thus reducing the basal exchange activity particularly in neutral pHi range. These observations suggest that LID-membrane interaction is also required for optimal NHE1 function in the resting state. PIP2 would be the most important lipid for this function (20, 21). However, under rapid PIP2 breakdown after receptor stimulation, most LID probes remain in the plasma membrane (supplemental Fig. S5 and movie S6), and exchange activity is uninhibited (no decrease in pHi) even when PIP2 re-synthesis is blocked by wortmannin (Fig. 4, A and B, supplemental Fig. S6 and movie S7), suggesting that basal activity is preserved even under conditions of reduced PIP2, possibly because of interactions between LID and predominant acidic lipids within membranes. Thus, the broad lipid specificity of LID may facilitate rapid NHE1 activation after receptor stimulation.

TABLE 2.

Summary for 22Na+ uptake activity (Fig. 4D) measured in cells expressing the NHE1 variants

The EIPA-inhibitable 22Na+ uptake was fitted by nonlinear least squares analysis to a Hill equation. Vmax is the 22Na+ uptake activity at a very low pHi and normalized by the amount of total protein expression. Mutation LI2 reduced both Vmax and pK values, while LI1 reduced the pK value. Data are the best-fitted values ± S.E.

| Mutant | Vmax | Expression-normalized Vmax | pK for pHi | Hill coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nmol/mg/min | % | |||

| WT | 30.0 ± 1.0 | 100 ± 3.4 | 6.69 ± 0.03 | 1.41 ± 0.12 |

| LI1 | 12.0 ± 0.5 | 88.2 ± 3.8 | 6.49 ± 0.03 | 1.38 ± 0.10 |

| LI2 | 10.9 ± 0.4 | 36.9 ± 1.4 | 6.30 ± 0.06 | 1.33 ± 0.17 |

PKC Inhibitors, except Staurosporin, Are Ineffective in Blocking NHE1 Activation

We next examined the possible involvement of PKC in NHE1 regulation by using PKC inhibitors. PMA induced the translocation of myristoyl alanine-rich protein kinase C substrate (MARCKS) from the plasma membrane to the cytoplasm (Fig. 5A) in response to PKC-mediated phosphorylation (33), and five known PKC inhibitors almost completely inhibited this PMA-induced MARCKS translocation, indicating that the test compounds could inhibit PKC. However, under similar conditions, bisindolylmaleimide I, calphostin C, Go-6976, and Ro-32–0432 had only a marginal inhibitory effect on alkalinization, but staurosporin completely inhibited alkalinization (Fig. 5B). These results suggest that PKC is not majorly involved in PE- or hormone-induced NHE1 activation. We next determined why only staurosporin completely inhibited NHE1 activation. Similar to LID mutations and unlike calphostin C, staurosporin by itself decreased cytosolic H+ affinity (Fig. 5C and Table 3), suggesting that staurosporin directly acts on the NHE1 molecule. Furthermore, staurosporin completely blocked PMA-induced translocation of LID to the plasma membrane, possibly through competition with PMA at LID (Fig. 6, A and D and supplemental movie S8). Similar inhibition by staurosporin was observed in the case of OAG- and phenylephrine-induced translocation of LID (data not shown). In contrast, calphostin C, which does not inhibit NHE1, had no effect on LID, although it completely inhibited PMA-mediated PKCδ-C1a translocation (Fig. 6, B and D and supplemental movie S9). The opposing translocation effects of staurosporin and calphostin C on PKCδ-C1a are attributable to their different competition sites; staurosporin binds to the ATP-binding site of PKC, whereas calphostin C binds to the PKCδ-C1a domain. Staurosporin itself at least partly reduced membrane localization of LID (supplemental Fig. S7), suggesting that it can inhibit lipid binding of LID. These results indicate that both staurosporin-induced reduction in H+ affinity and abolishment of NHE1 activation occur via interactions between staurosporin and LID, not via inhibition of PKC. Like staurosporin but with a weaker effect, the PE analogue 4α-PMA inhibited both PMA-induced NHE1 activation and LID recruitment to the plasma membrane, apparently in competition with PMA (Figs. 5D and 6, C and D and supplemental Fig. S7 and movie S10). Partial inhibition of PMA-induced translocation was also observed for Go-6976 structurally related compound of staurosporin (supplemental Fig. S7), which appears to slightly inhibit NHE1 activation (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5.

Effect of PKC inhibitors and 4α-PMA on PE-induced NHE1 activation. A, effect of PKC inhibitors on the translocation of myristoylated alanine-rich C kinase substrate (MARCKS) from the plasma membrane to the cytoplasm. Cells transiently expressing the MARCKS-GFP protein were preincubated with PKC inhibitors (1 μm each) for 15 min, and then PMA (1 μm) together with these inhibitors were added at time 0. These PKC inhibitors almost completely abrogated the translocation of MARCKS from the plasma membrane to the cytoplasm, confirming that they inhibited PKC. BIM, bisindolylmaleimide I; CalC, calphostin C; Go, Go-6976; Ro, Ro-32–0432; and St, staurosporin, Scale, 10 μm. B, under conditions similar to those in the experiment of MARCKS translocation, the effect of PKC inhibitors on PMA- or phenylephrine (Phe)-induced NHE1 activation was examined. Except for staurosporin (St), all other PKC inhibitors tested had only a marginal inhibitory effect on NHE1 activation. C, staurosporin, but not calphostin C, decreased cytosolic H+ affinity in WT-NHE1-expressing cells. D, 4α-PMA competitively inhibited PMA-induced cytoplasmic alkalinization. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

TABLE 3.

Summary for 22Na+ uptake activity (Fig. 5C) measured in cells expressing wild-type NHE1 in the presence of calphostin C or staurosporin

The EIPA-inhibitable 22Na+ uptake was fitted by nonlinear least squares analysis to a Hill equation. Vmax is the 22Na+ uptake activity at a very low pHi and normalized by Vmax in the absence of inhibitors. Although calphostin C and staurosporin did not affect Vmax, St significantly reduced the pK value. Data are the best-fitted values ± S.E.

| Treatment | Vmax | Normalized Vmax | pK for pHi | Hill coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nmol/mg/min | % | |||

| None | 30.1 ± 0.4 | 100 ± 1.3 | 6.62 ± 0.03 | 1.46 ± 0.13 |

| Calphostin C | 29.8 ± 1.1 | 99.3 ± 3.7 | 6.70 ± 0.02 | 1.70 ± 0.10 |

| Staurosporin | 29.8 ± 2.9 | 99.3 ± 9.7 | 6.40 ± 0.04 | 1.70 ± 0.21 |

DISCUSSION

We analyzed the biochemical properties of LID, a critical regulatory region of NHE1, to gain insights into the molecular mechanism underlying the hormonal activation of NHE1. We found that (i) PEs directly interact with the LID of NHE1 in vitro, (ii) GFP-LID translocates to the plasma membrane in response to PEs, OAG, and α1AR agonists, suggesting that the direct interaction of PEs/DAG with LID increases LID affinity to the plasma membrane. Furthermore, mutations affecting LID (particularly LI2) markedly inhibit the above interactions and abolish PE- or α1AR agonist-induced NHE1 activation, supporting the view that NHE1 is activated through the direct interaction of LID with PEs/DAG, followed by stronger interaction with the plasma membrane (see Fig. 6E for the schematic model). Compared with LI2, LI1 mutation had a weak inhibitory effect on lipid binding (Fig. 3C), but resulted in complete abrogation of NHE1 activation (Fig. 4, B and C). NHE1 activation may occur via multiple sequential steps including PEs/DAG binding, conformational change of LID and subsequent increased association of LID with membranes. LI1 mutation partially inhibited PE binding and completely inhibited membrane translocation of LID. Thus complete abrogation of NHE1 activation would be due to an overall consequence resulting from inhibitions of multiple events by LI1 mutation.

Experimental evidence indicated that the C terminus (∼40 residues) of LID is required for its interaction with PEs. Further, we observed that the N-terminal peptide of LID (GC20) preferentially interacted with acidic lipids (data not shown), supporting a previous report that positive charge clusters in the LID N terminus may be important for electrostatic interactions (20). However, the interaction of LID with the plasma membrane was abrogated by mutations in the C terminus (LI2 etc.) as well as those in the N terminus (mutations of basic residues, etc., see supplemental Fig. S3), indicating that the entire region encoding the LID is important for the association of this domain with cell membranes. Further experiments will be required for elucidating whether LID is separated into several functional subdomains and how PEs/DAG increase the interaction with membrane lipids via possible structural coupling between these subdomains.

We identified several residues, for example, Leu-573 and Ile-574 that were important for the binding of PEs to LID. Unlike LID, the C1 domains of PKC and other “nonkinase” proteins such as chimerins and Munc13 coordinate two Zn2+ ions with conserved cysteine and histidine residues (34, 35). Although the amino acid sequences of the LID and PKC-C1 domain exhibit partial homology, LID does not possess residues coordinating Zn2+ ions (supplementary Fig. S8). Thus, LID is a previously unrecognized motif of PE binding. Because of the marked differences between the LID sequence and the sequences of known PE targets, the existence of this domain may have been overlooked in many membrane proteins, despite its functional importance. PE binding to LID occurs at micromolar concentrations of PEs, at least, in vitro. Thus, the affinity of PEs to LID may not be sufficiently high for their interaction with NHE1 in cells. However, we observed that despite the apparent low affinity, submicromolar concentrations of PEs were capable of activating NHE1: alkalinization was detectable at 0.03 μm SAPD (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, (i) incubation of GP57 with membrane lipids increased the affinity of PEs to LID (Table 1), and (ii) SAPD fluorescence in the medium was observed to rapidly and strongly accumulate within the cells (data not shown). The latter observation suggests that the concentration of PEs in the cells is much higher than that in the medium, and that the low concentration of added PEs is sufficient for PE interaction with the LID of NHE1 within the cells, despite the low affinity of PEs.

Stimulation of G protein-coupled receptors induces hydrolysis of PIP2 by phospholipase C, which in turn produces two second messengers: DAG, which is a potent PKC activator, and inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate, which releases the calcium stored in the endoplasmic reticulum (36). We previously reported that the released calcium activates NHE1 through the direct binding of calcium/calmodulin to the autoinhibitory cytoplasmic domain of NHE1 in the early phase (∼1 min) after receptor stimulation (37, 38). In addition to such regulation, our present findings indicate that DAG directly contributes to the prolonged activation of NHE1. It should be noted that NHE1 activity is not inhibited even under the conditions of reduced PIP2 levels after receptor stimulation. This finding can be best explained by the broad lipid specificity of LID and the predominant presence of acidic phospholipids like phosphatidylserine in the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane (39). By interacting with different lipids, LID would be able to preserve basal exchange activity and render NHE1 further activatable despite PIP2 breakdown. However, this hypothesis appears to contradict previous findings that NHE1 activity is robustly inhibited under conditions of PIP2 depletion either by cellular ATP depletion (20) or overexpression of lipid phosphatase from salmonera (40). We cannot rule out the possibility that receptor stimulation produces different effects on PIP2 hydrolysis from those produced by ATP depletion or treatment with exogenous phosphatase: for instance, some localized PIP2 bound to NHE1 may not be completely hydrolyzed upon receptor stimulation and thus the NHE1 activity may be preserved, whereas localized PIP2 may be dephosphorylated by other treatments, leading to robust inhibition of NHE1 activity.

Although many studies have used PKC inhibitors to validate the involvement of PKC in NHE1 regulation (41–44), the effectiveness of these inhibitors are variable. Therefore, in this study, we assessed NHE1 regulation by using only those inhibitors that completely inhibited MARCKS translocation under similar conditions. Our data suggest that PKC is not largely involved in either PE- or hormone-induced NHE1 activation; however, we cannot rule out the involvement of PKC isoforms that do not phosphorylate MARCKS. In this study, we identified staurosporin as a new type of NHE1 inhibitor. Interestingly, staurosporin inhibited NHE1 activity only by reducing its affinity to H+ without altering the maximal exchange activity at acidic pHi (Table 3), in sharp contrast to amiloride derivatives, which completely inhibit NHE1 activity. Importantly, the NHE1 inhibition by staurosporin was mediated through LID, which is distant from the putative amiloride-binding sites, the transmembrane-spanning segments (45, 46). This observation is consistent with our previous findings that the juxtamembrane cytoplasmic domain including LID is crucial for pHi sensing (22, 47).

LID appears to bind various lipids or lipophilic compounds with broad specificity and to serve as an essential module to differentially regulate NHE1 activity, depending on the interacting molecules. For example, 4α-PMA was a weak inhibitor of PMA-induced NHE1 activation (Fig. 5D). Surprisingly, okadaic acid, a phosphatase inhibitor and known potent NHE1 activator (48), promoted LID translocation to the plasma membrane,3 probably via direct interaction between the two. This broad specificity of LID is advantageous for NHE1, which is regulated by a variety of signals, and explains the diverse regulatory mechanisms of different NHE isoforms. For example, NHE1 and NHE2 are activated by PEs (49), whereas NHE3 and NHE5 are inhibited by PEs (49, 50). Despite the relatively high homology of LIDs among NHE isoforms, subtle differences exist in the primary structure of these isoforms (supplemental Fig. S8). These differences may lead to differences between the regulatory effects of PE binding on NHE1/2 and NHE3/5. This testable hypothesis will be analyzed in the future.

Many studies have reported that NHE1 is regulated by phosphorylation-dependent pathways (6, 51–54). However, the role of phosphorylation of the NHE1 molecule itself is rather controversial; in our hands, no significant inhibition of PMA- or hormone-induced NHE1 activation was detected upon Ala-substitution mutations of several Ser residues including the ones reported to be phosphorylated (data not shown, but see Ref. 23). In conclusion, we propose a novel phosphorylation-independent mechanism for transporter regulation via “non-C1”-type PE receptors, which may be distributed in many membrane proteins. Our findings may help develop new LID-based therapies for cancer and heart failure since drugs targeting LIDs are expected to selectively block increments in NHE1 activity in response to various stimuli.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Prof. Munekazu Shigekawa (Senri Kinran University) for the critical reading of this manuscript.

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas 18077015 and Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) 19390080, a grant for the Promotion of Fundamental Studies in Health Sciences from the National Institute of Biomedical Innovation (NIBIO), research grants for Cardiovascular Diseases (20C-3 and 21A-13), and a grant (nano-006) for Research on Advanced Medical Technology from the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare of Japan.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S8 and movies S1–S10.

S. Wakabayashi, unpublished observations.

- PE

- phorbol ester

- FRET

- fluorescence resonance energy transfer

- SAPD

- sapintoxin D

- PC

- phosphatidylcholine

- PEt

- phosphatidylethanolamine

- PG

- phosphatidylglycerol

- PA

- phosphatidic acid

- PI

- phosphatidylinositol

- PIP2

- phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate

- Ch

- cholesterol

- SM

- sphingomyelin

- LID

- lipid-interacting domain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nishizuka Y. (1992) Science 258, 607–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Griner E. M., Kazanietz M. G. (2007) Nat. Rev. Cancer 7, 281–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moolenaar W. H., Tertoolen L. G., de Laat S. W. (1984) Nature 312, 371–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grinstein S., Cohen S., Goetz J. D., Rothstein A. (1985) J. Cell Biol. 101, 269–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Besterman J. M., Cuatrecasas P. (1984) J. Cell Biol. 99, 340–343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wakabayashi S., Shigekawa M., Pouyssegur J. (1997) Physiol. Rev. 77, 51–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pedersen S. F., Cala P. M. (2004) J. Exp. Zoolog. A. Comp. Exp. Biol. 301, 569–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zachos N. C., Tse M., Donowitz M. (2005) Annu. Rev. Physiol. 67, 411–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fliegel L. (2005) Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 37, 33–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orlowski J., Grinstein S. (2004) Pflugers Arch. 447, 549–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karmazyn M., Sawyer M., Fliegel L. (2005) Curr. Drug Targets Cardiovasc Haematol. Disord. 5, 323–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakamura T. Y., Iwata Y., Arai Y., Komamura K., Wakabayashi S. (2008) Circ. Res. 103, 891–899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cardone R. A., Casavola V., Reshkin S. J. (2005) Nat. Rev. Cancer 5, 786–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paris S., Pouysségur J. (1984) J. Biol. Chem. 259, 10989–10994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lacroix J., Poët M., Maehrel C., Counillon L. (2004) EMBO Rep. 5, 91–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pang T., Su X., Wakabayashi S., Shigekawa M. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 17367–17372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsushita M., Sano Y., Yokoyama S., Takai T., Inoue H., Mitsui K., Todo K., Ohmori H., Kanazawa H. (2007) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 293, C246–C254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ammar Y. B., Takeda S., Hisamitsu T., Mori H., Wakabayashi S. (2006) EMBO J. 25, 2315–2325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mishima M., Wakabayashi S., Kojima C. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 2741–2751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aharonovitz O., Zaun H. C., Balla T., York J. D., Orlowski J., Grinstein S. (2000) J. Cell Biol. 150, 213–224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuster D., Moe O. W., Hilgemann D. W. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 10482–10487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wakabayashi S., Fafournoux P., Sardet C., Pouysségur J. (1992) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 2424–2428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wakabayashi S., Bertrand B., Shigekawa M., Fafournoux P., Pouysségur J. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 5583–5588 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wakabayashi S., Pang T., Su X., Shigekawa M. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 7942–7949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stauffer T. P., Ahn S., Meyer T. (1998) Curr. Biol. 8, 343–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pouysségur J., Sardet C., Franchi A., L'Allemain G., Paris S. (1984) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 81, 4833–4837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hisamitsu T., Ben Ammar Y., Nakamura T. Y., Wakabayashi S. (2006) Biochemistry 45, 13346–13355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.L'Allemain G., Paris S., Pouysségur J. (1984) J. Biol. Chem. 259, 5809–5815 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wakabayashi S., Hisamitsu T., Pang T., Shigekawa M. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 11828–11835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Slater S. J., Ho C., Kelly M. B., Larkin J. D., Taddeo F. J., Yeager M. D., Stubbs C. D. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 4627–4631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosse C., Linch M., Kermorgant S., Cameron A. J., Boeckeler K., Parker P. J. (2010) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 103–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Slater S. J., Taddeo F. J., Mazurek A., Stagliano B. A., Milano S. K., Kelly M. B., Ho C., Stubbs C. D. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 23160–23168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ohmori S., Sakai N., Shirai Y., Yamamoto H., Miyamoto E., Shimizu N., Saito N. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 26449–26457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang G., Kazanietz M. G., Blumberg P. M., Hurley J. H. (1995) Cell 81, 917–924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kazanietz M. G. (2002) Mol. Pharmacol. 61, 759–767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taylor C. W. (2002) Cell 111, 767–769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bertrand B., Wakabayashi S., Ikeda T., Pouysségur J., Shigekawa M. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 13703–13709 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wakabayashi S., Bertrand B., Ikeda T., Pouysségur J., Shigekawa M. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 13710–13715 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Meer G., Voelker D. R., Feigenson G. W. (2008) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 112–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mason D., Mallo G. V., Terebiznik M. R., Payrastre B., Finlay B. B., Brumell J. H., Rameh L., Grinstein S. (2007) J. Gen. Physiol. 129, 267–283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Snabaitis A. K., Yokoyama H., Avkiran M. (2000) Circ. Res. 86, 214–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maly K., Strese K., Kampfer S., Ueberall F., Baier G., Ghaffari-Tabrizi N., Grunicke H. H., Leitges M. (2002) FEBS Lett. 521, 205–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aharonovitz O., Granot Y. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 16494–16499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu F., Gesek F. A. (2001) Am. J. Physiol. Renal. Physiol. 280, F415–F425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Counillon L., Franchi A., Pouysségur J. (1993) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 4508–4512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Orlowski J., Kandasamy R. A. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 19922–19927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ikeda T., Schmitt B., Pouysségur J., Wakabayashi S., Shigekawa M. (1997) J. Biochem. 121, 295–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sardet C., Fafournoux P., Pouysségur J. (1991) J. Biol. Chem. 266, 19166–19171 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kandasamy R. A., Yu F. H., Harris R., Boucher A., Hanrahan J. W., Orlowski J. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 29209–29216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Attaphitaya S., Nehrke K., Melvin J. E. (2001) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 281, C1146–C1157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takahashi E., Abe J., Gallis B., Aebersold R., Spring D. J., Krebs E. G., Berk B. C. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 20206–20214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meima M. E., Webb B. A., Witkowska H. E., Barber D. L. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 26666–26675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Coccaro E., Karki P., Cojocaru C., Fliegel L. (2009) Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 297, H846–H858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Snabaitis A. K., Cuello F., Avkiran M. (2008) Circ. Res. 103, 881–890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.