Abstract

Diagnosis of PIOL can be challenging. It requires a high degree of clinical suspicion and differential diagnosis includes infectious and non-infectious etiologies particularly the common masquaraders sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, viral retinitis and syphilis. The definitive diagnosis depends on demonstration of malignant lymphoma cells in ocular specimens or CSF. Ocular specimen could include vitreous, aqueous or chorioretinal biopsy. Ocular pathologist should be consulted prior to the diagnostic procedure to help handle and process the specimen appropriately. In addition to cytology, flow cytometry, immunohistochemistry, molecular analysis and cytokines may be used as adjuncts in facilitating the diagnosis.

Keywords: intraocular lymphoma, diagnosis, cytology, cytokines, immunohistochemistry

INTRODUCTION

Primary intraocular lymphoma (PIOL), which was known as reticulum cell sarcoma in the past, is a subset of PCNSL, which initially presents in the eye with or without simultaneous CNS involvement. Most PIOL is extranodal non-Hodgkin, diffuse large B-cell lymphomas.1–6 Diagnosis of PIOL requires a high degree of clinical suspicion that eventually leads to a series of diagnostic procedures. The diagnosis of PIOL can be difficult to make and requires malignant cells or tissue for diagnosis. The atypical lymphoid cells are large with a scant basophilic cytoplasm and a high nuclear:cytoplasmic ratio, and prominent nucleoli. Flow cytometry, immunohistochemistry, cytokine analysis, and gene rearrangements are also used as adjuncts in the diagnosis. Definitive diagnosis of PIOL requires histopathologic evidence of malignant lymphoma cells in ocular specimens. Such specimens can include vitreous, aqueous or chorioretinal biopsy. It is crucial to plan how to handle the specimen prior to obtaining the tissue. Ocular pathologist who will receive the biopsy specimen should be involved in the patient’s preparation for the diagnostic procedure to help determine which affected intraocular structure may provide the best opportunity to result in the highest yield of lymphoma cells.1,7 Approximately 60–80% of patients with PIOL will develop CNS lymphoma.8,9 Therefore once PIOL is suspected the patient should undergo a thorough CNS evaluation including MRI and lumbar puncture with cytologic examination of the CSF. PCNSL can disseminate within the CSF and lymphoma cells can be identified in about 25% patients.10 When lymphoma cells are identified in the CSF, it is not necessary to pursue any further diagnostic procedures to document the presence of lymphoma cells in the eye. When brain involvement has been ruled out one may focus on the involved eye from which to make a diagnosis. In this article we will review diagnostic procedures required to obtain the tissue and handling and processing of the tissue including cytology, cytokine analysis and molecular techniques.

Diagnostic Approach

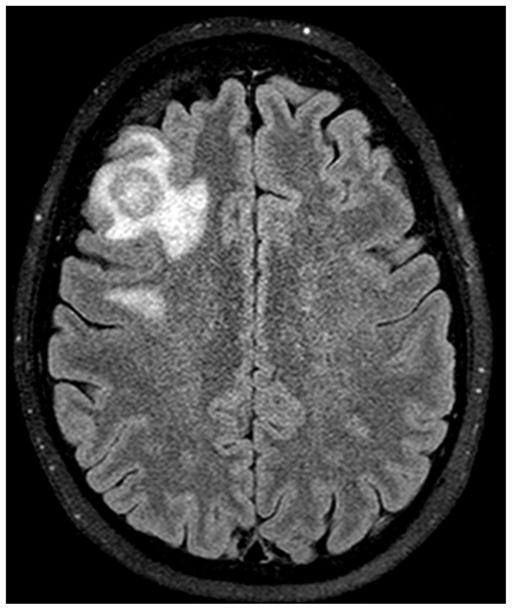

The diagnosis of PIOL is based on the identification of atypical lymphoid cells in the eye. However, it is possible to make the diagnosis by demonstrating lymphoma cells in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) because PIOL is a subset of PCNSL. CNS lesions can be ruled out through neuroimaging, such as with a computed tomography scan (CT scan) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Figure 1). We recommend that a lumbar puncture for CSF evaluation be performed prior to a diagnostic vitrectomy or a vitreous or aqueous aspiration, as it is less invasive with the caveat that it may be non-contributory in cases with no obvious CNS involvement.3,7 Brain biopsy could be considered in select cases, however early diagnosis through ocular involvement may obviate the need for brain biopsy. Regardless, definitive tissue diagnosis is required for initiation of treatment. The processing and examination of CSF and vitreous are the same and include cytology, immunocytochemistry, flow cytometry, cytokine, and molecular analyses. The diagnostic approach to patients with PIOL has changed considerably in recent years with more experts utilizing immunocytochemistry, immunohistochemistry, cytokines and molecular analysis for the diagnosis.

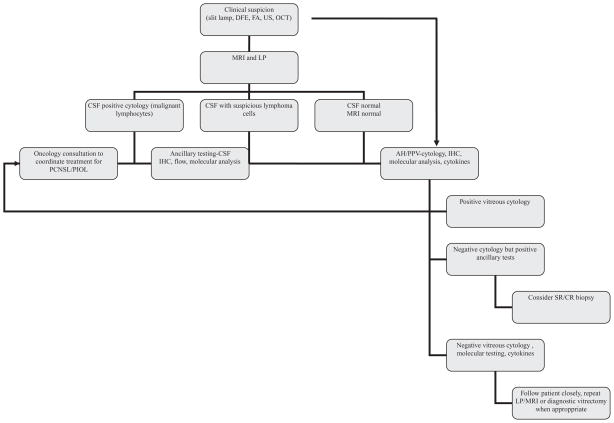

Figure 1.

CNS involvement in a patient with primary intraocular lymphoma. Note the enhancing mass slightly larger than 1.5 cm in the right middle frontal gyrus surrounded by modest amount of vasogenic edema.

Vitreous Biopsy

Chorioretinal biopsies and enucleated eyes showed that lymphoma cells are typically located between RPE and Bruchs membrane but may invade the vitreous.4,11 Although ocular tissue can be obtained via vitreous or aqueous aspiration, external chorioretinal biopsy, transvitreal retinal, subretinal, or chorioretinal biopsy, a complete diagnostic vitrectomy is the preferred method.7,8,12 Chorioretinal biopsy may be associated with more complications 7 whereas vitreous or anterior chamber taps may lead to insufficient and hypocellular samples leading to low diagnostic yield.13,14 For eyes with solitary subretinal lesions without vitreous cells, a subretinal aspiration biopsy could be considered.15 Prior to the development of pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) in 1970s the only way to make a diagnosis of PIOL was enucleation. However, today enucleation is not an ideal diagnostic procedure in an eye with PIOL and visual potential but could be considered in severe cases where there is no visual potential to obtrain definite diagnosis.4 Klingele and Hogan and Michels et al were the first to report cases where the diagnosis of PIOL was made by cytologic examination of the vitreous.16,17 Since then vitrectomy has been more frequently employed in the diagnosis of PIOL, in fact, when there is a suspicion of PIOL PPV and LP are the two important diagnostic procedures used.

Vitrectomy is typically done in the eye with the more severe “vitritis” and poorer visual acuity. Cytologic examination of the vitreous sample is the mainstay in the diagnosis of PIOL. While modern vitrectomy techniques dramatically decreased adverse events it is not without imperfections. There have been occasions where vitrectomy fails to disclose tumor cells when CSF shows lymphoma cells or vice versa. It should not be surprising to find lymphoma cells only in the vitreous and not in CSF as in its initial phase PIOL may not have CNS involvement.1 Because the lymphoma cells are often fragile and easily degenerate in the vitreous, it is critical to handle and process the specimen appropriately.18,19 It is crucial that the ocular pathologist who will receive the specimen is aware of the diagnosis and when the specimen is to be delivered.

Obtaining an adequate vitreous sample starts with a standard three-port pars plana vitrectomy. A complete core vitrectomy is recommended.7 Undiluted fresh vitreous (1–2 ml) is first obtained using the vitrector with infusion off for cytological analysis and placed into cell culture medium, RPMI (Roswell Park Memorial Institute, Buffalo, NY) for a total of 3–5 mL of fluid and immediately transported to the awaiting cytology laboratory for appropriate handling and rapid processing. The cells are then isolated by the ocular pathologist using cytocentrifuge and the supernatant is gently pipetted off for cytokine analysis and possibly for viral PCR. Cytocentrigugation allows for a higher yield of cellular material. If cytokine assay is not available at the site of vitrectomy the supernatant can be frozen and sent to a facility where this can be done. A dilute specimen is then obtained by removing the remaining vitreous with the infusion on. The vitreous wash in the cassette should also be sent for microbiologic cultures.7,20,21

One other consideration prior to any tissue sampling is the steroid treatment patient has received. It is known that prior treatment with steroids, and possibly any immunosuppressive, may lower diagnostic yield.8 A quick taper to allow better yield should be considered in such cases. In a recent survey of several experts it was the opinion of nearly all experts that the risk for a negative first vitrectomy biopsy or tap is higher when patients are receiving treatment with corticosteroids.22 A study at the National Eye Institute of 12 patients demonstrated that 30% of cases of PIOL had had previous false-negative sampling.3,8 Other authors have also noted that in some cases more than one vitreous biopsy was needed to make the diagnosis.7 Some centers chose to perform an AC or vitreous tap before proceeding with a vitrectomy. Taken together these highlight the importance of repeating the diagnostic procedure (tap, vitrectomy or LP) where there is a strong clinical suspicion. As mentioned above it is essential to involve the ocular pathologist early in the process so that the diagnostic plan can be made appropriately and the specimen handled accordingly.

Cytology

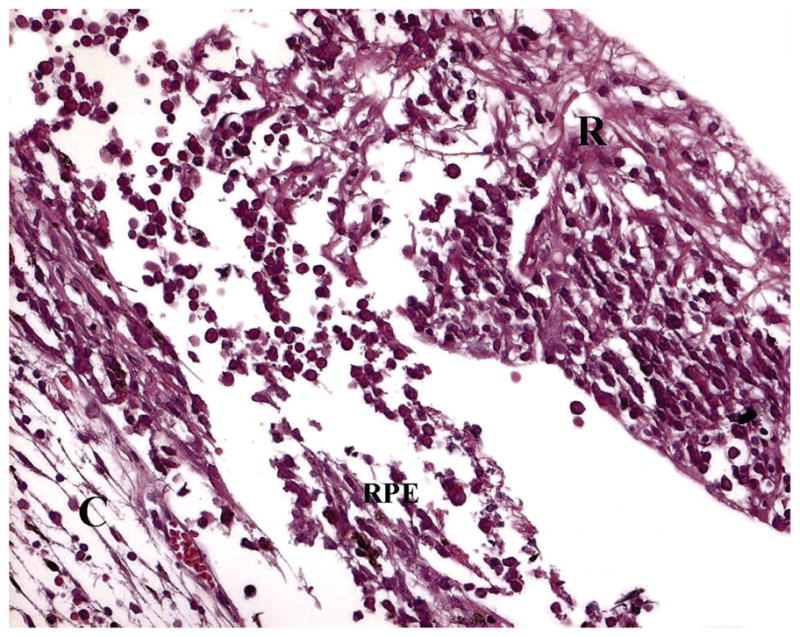

Light microscopic examination of PIOL specimen reveals a population of atypical lymphoid cells tightly packed in sub-RPE space.3,4,23,24 The cells are high-grade lymphoma cells that exhibit a variable number of mitoses. Although sub-RPE space is most typical, these atypical cells can be found in vitreous, retina and optic nerve (Figure 2). Alterations in the RPE and retina such as RPE atrophy and detachment, retinal detachment and necrosis can also be observed.25,26 Reactive lymphocytes that are smaller than PIOL cells can also be seen.

Figure 2.

Lymphoma cells located both in the sub-RPE space and invading into the retina (H&E) (C: choroid, RPE: retinal pigment epithelium, R: retina).

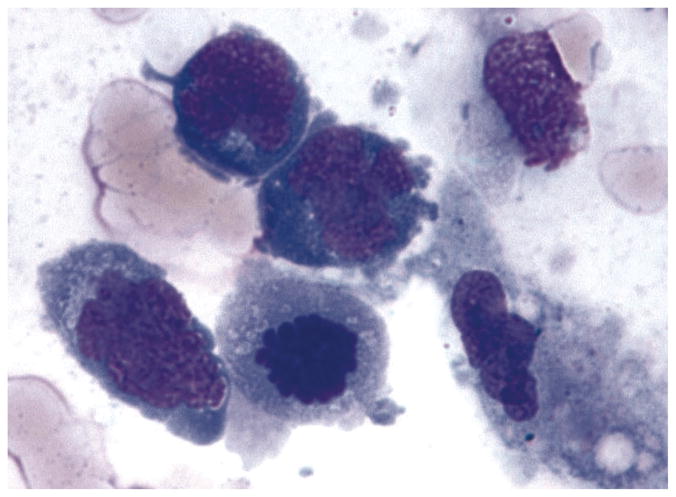

Lymphoma cells can be identified using the hematoxylin and eosin or Pap stain, however Giemsa or Diff Quick staining are better in revealing the characteristics of the malignant B cells.7 Typical lymphoma cells are large lymphoid cells with scanty basophilic cytoplasm and large nuclei (Figure 3). These cells may have round, oval, bean-shaped or hypersegmented nuclei with prominent nucleoli and mitoses.8,17,27 The nuclear chromatin is heterogeneous and coarse and unevenly distributed granules can be found throughout the nucleus. Merle-Beral et al showed that the recognition of lymphoma cells by cytology with or without immunophenotyping on slides generated a strong suspicion of the diagnosis in 94% of the cases.28 Necrotic lymphoma cells can also be identified among the viable PIOL cells. Under electron microscopy lymphoma cells show lack of cellular cohesion or cytoplasmic processes that distinguish this tumor from metastatic non-lymphoid tumors.27 Often, vitreous specimen contains reactive T lymphocytes, necrotic cells, fibrin, and debris along with lymphoma cells, thus examination of the specimen requires an experienced ocular pathologist.3,7

Figure 3.

Photomicropgraph showing lymphoma cells from the vitreous of a patient with PIOL. Note the lymphoma cells are large with scanty basophilic cytoplasm and large hyper-segmented nuclei and prominent nucleoli (Giemsa).

Immunohistochemistry and Flow Cytometry

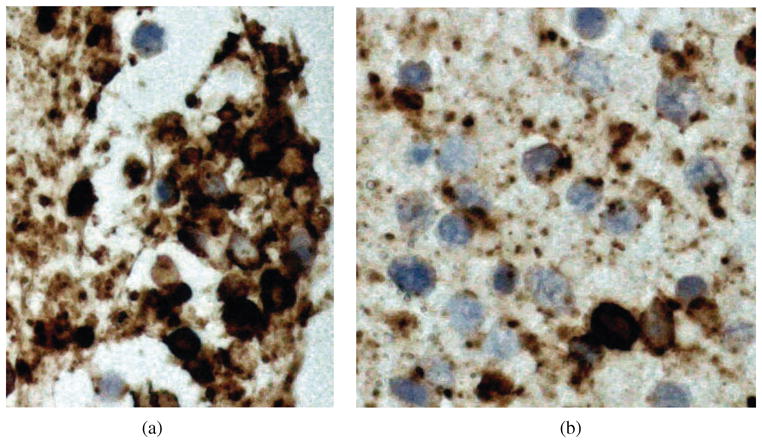

The immunophenotype of monoclonality supports the cytological diagnosis of lymphoma. Although immunophenotyping of PCNSL started in the late 1970s, the immunohistochemical studies of POL did not begin until late 1980s.18,29,30 Most PIOL are monoclonal B cell lymphomas that stain positively for B cell markers, such as CD19, CD20, and CD22 (Fig 4A), and show restricted expression of either kappa or lambda chain.1 Germinal center markers can also be expressed, such as BCL6 and CD10. Concomitant expression of BCL-6 and MUM1 has been reported in 5 patients with PIOL.3 Cytologic examination can reveal malignant lymphocytes but it can not distinguish between B-cell or T-cell origin. While most PIOLs are of large B-cell origin, very rarely they can be of T-cell origin and can simulate reactive inflammatory process. Immunohistochemistry for T-cell markers such as CD3 and PCR for TCR gene rearrangements can help identify such rare cases (Figure 4B). However due to lack of immunocytochemical markers for T-cell PIOL, diagnosis of T-cell PIOL is often more difficult than B-cell PIOL.31–33

Figure 4.

Figure 4A and B. Immunohistochemistry of lymphoma cells can help differentiate B- and T-cell lymphomas. Majority of PIOL are monoclonal B-cell lymphomas that stain positively for B-cell markers, such as CD20 (A), however there may be some reactive T-cells that stain positively for T-cell markers, such as CD3 (B).

Although a cytological diagnosis is still the gold standard, immunophenotyping obtained from flow cytometry can be very helpful in making the diagnosis. This technique has been used in detection of newly diagnosed aggressive B cell lymphoma at risk for CNS involvement.34 Flow cytometry can analyze several different markers simultaneously and has been used to confirm monoclonality in both B cell and T cell PIOL.2 The problem with flow cytometry is the background “noise” that may obscure the signal of the lymphoma cells when there are only few cells of interest, which is usually the case in PIOL. Davis et al noted that flow cytometry was helpful in 7 out of 10 cases in making the diagnosis of ocular lymphoma.35 Not all B-cell lymphomas produce surface immunoglobulins, preventing flow cytometric recognition of these cells. Identification of T-cells via flow cytometry could indicate an inflammatory reaction or the rare T-cell lymphoma; confirming the monoclonality of these T-cells would require molecular analysis. Despite its imperfections flow cytometry is a useful adjunct.

Cytokines

B-cells secrete high amounts of IL-10, an immunosuppressive cytokine. On the other hand, in uveitis the vitreous is typically rich in IL-6, a pro-inflammatory cytokine commonly secreted by macrophages and T-cells. IL-10 to IL-6 ratios greater than 1.0 are highly suggestive of PIOL.36 Wolf et al. showed that intravitreal IL-10/IL-6 >1.0 was used to correctly distinguish PIOL from uveitis with approximately 75% sensitivity and specificity.37 The mean IL-10 to IL-6 ratio in 35 PIOL vitreous specimens was 5.23 whereas it was 0.23 for uveitis patients.21 IL-10 levels in the aqueous have also been found to be significantly elevated in PIOL patients 12,38 Cassoux et al. have shown that a cutoff of 50 pg/mL in the AH was associated with a sensitivity of 0.89 and a specificity of 0.93. In the vitreous, a cut-off value of 400 pg/mL yielded a specificity of 0.99 and a sensitivity of 0.8.12 Low IL-10 levels may be particularly helpful when a T-cell lymphoma is suspected.28 Although it is not diagnostic cytokine analysis is a useful adjunct to aforementioned diagnostic methods and the advantage is that the supernatant of the vitreous specimen can be used for this purpose.

Molecular Analysis

Microdissection allows for selection of a relatively pure cell population from cytological or histopathological slides that can then be subjected to DNA, RNA and protein analysis to characterize these cells. Laser capture or manual technique using a fine gauge (30 gauge) needle has been used successfully for microdissection.39,40 Monoclonality can be confirmed in these cells using PCR through demonstration of rearrangement of the Ig heavy chain (IgH). Chan and colleagues have shown that 100% of 85 cases of PIOL had rearrangement of the IgH gene using microdissection and PCR.24,41 This technique improves the diagnosis for those samples that are composed of few PIOL cells admixed with many reactive inflammatory cells 39 Similar to studies of systemic non-Hodgkin lymphomas, ocular specimens from patients with B-cell PIOL have revealed similar IgH rearrangements, particularly in the third complementarity-determining region (CDR3) of the IgH variable region (Figure 5). Monoclonality of B-cell populations can be detected using FR2, FR3, and/or CDR3 primers.41 The immunoscope technique may also be used to differentiate between a polyclonal and a monoclonal infiltrate.42 Monoclonality of rare T-cell PIOL can be demonstrated through TCR gene rearrangements.

Figure 5.

Micro-dissection and PCR of a lymphoma cell from vitreous reveals IgH gene rearrangement using the third complementarity-determining region (CDR3) as primer.

A frequent problem with PIOL specimens is the “paucity”. We recommend that the cytology be given priority on vitreous specimens and the supernatant be used for cytokine analysis (IL-10 and IL-6). The adjunctive tests such as IHC, flow cytometry and molecular analysis should be performed if there is sufficient amount of specimen.

Differential Diagnosis

Primary intraocular lymphoma is one of the most challenging masquerade syndromes. Due to heterogeneous clinical features, diagnosis is made late in most of cases, inducing delayed therapeutic management with poor visual prognosis and life threatening complications.43 Differential diagnosis must take into account the age of the patient and the clinical presentation. Further investigations will be mandatory to confirm the diagnosis, when possible.

Infectious Entities

Most of the following conditions are rapidly progressive and patients are usually addressed without delay to a tertiary eye care centre. However, when the disease is atypical and resists to specific antimicrobial agents, PIOL may become an important condition to exclude, using the aforementioned techniques. Moreover, molecular analysis of ocular fluids to exclude an infectious origin becomes an important issue.44

Viral Retinitis

PIOL may masquerade as an acute retinal necrosis syndrome. Acute retinal necrosis (ARN), caused by herpes virus family, typically occurs in immunecompetent patients, involves the retinal periphery and progresses rapidly towards the posterior pole. Anterior uveitis is quite particular with viral keratic precipitates in most cases. Necrosis is associated with vasculitis and dense vitritis. Retinal detachment may occur in 30 to 75% of cases during the course of the disease. CMV retinitis on the other hand typically occurs in immunecompromised patients. Necrotic areas and hemorrhages in both conditions may mimic PIOL. Diagnosis is confirmed with anterior chamber or vitreous tap and PCR analysis with a positivity rate of 85 to 95%.45

Extensive Retinochoroidal Toxoplasmosis

Even though the majority of toxoplasma lesions are easily diagnosed with an thorough ophthalmic exam, some diffuse forms may occur in immunecompromised patients and may be difficult to differentiate from PIOL. The presence of RPE alterations in PIOL may mimic toxoplasmic scars. Dense vitritis and anterior segment inflammation are often associated. Bilateral disease may happen depending on the degree of immunosuppression. Diagnosis in atypical cases is based on the analysis of ocular fluids. Furthermore, Toxoplasma gondii has been isolated in certain forms of PIOL.46

Syphilitic Retinitis

Retinitis is usually diagnosed at the retinal periphery even though macular forms may occur. Vitritis remains moderate, associated with anterior segment and retinal vascular involvement. Evolution is relatively slow and diagnosis is confirmed by serological analysis. Interestingly retinitis resolves without scars after specific antibiotic therapy in most cases.

Whipple Disease

Caused by Tropheryma whipplei whipple disease is rarely associated with ocular manifestations and they usually occur late in the course of the disease.47 A large spectrum of ocular manifestations has been reported, including mostly uveitis, retinitis, retinal hemorrhages, choroiditis; persistent vitritis along with retinitis may mimic PIOL. Various neuroophthalmological manifestations have also been reported, such as ophthalmoplegia, supranuclear gaze palsy, nystagmus, myoclonus, ptosis, papilledema, or optic nerve atrophy. Specific antibiotics may cure the disease without corticosteroids.

Non-Infectious Entities

Frequency of non-infectious uveitis in the elderly is relatively high.48,49 Diagnosis is usually delayed in patients with PIOL as most of them undergo different sets of diagnostic investigations and corticosteroid regimens. In some cases, resistance to corticosteroids may encourage the clinician to propose the use of immunosuppressive agents including biologics. However, these strategies usually fail within a few months. PIOL or an infectious entity must be excluded in all cases of uveitis resisting to systemic or periocular corticosteroids, before considering steroid sparing agents. However one has to keep in mind that PIOL may initially respond, at least to some extent, to steroids as well.

Sarcoidosis and Tuberculosis

Both conditions may occur in the elderly and may raise the suspicion for PIOL. Presence of posterior synechiae and cystoid macular edema may help differentiate sarcoidosis or tuberculosis (TB) from PIOL however in the presence of significant posterior segment involvement differentiation may be difficult 50 Ancillary tests are necessary to confirm the diagnosis. Analysis of ocular specimen may be necessary in challenging cases1.

Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare, potentially multisystemic disease with a large clinical spectrum. It usually affects bone, skin, lungs, lymph nodes, spleen, thymus, hypothalamus and pituitary gland. Ocular involvement in LCH includes orbital, neuroophthalmological, and lid changes. Orbital involvement occurs in 20% of patients with lytic lesions of the orbital wall and is usually a unifocal granuloma. Ophthalmic manifestations, which may include choroidal involvement, have been reported in 10% of cases. LCH is a neoplastic proliferation of Langerhans cells with expression of CD1a, S100 protein and the presence of Birbeck granules on ultrastructural examination.51

Behçet’s Disease

It occurs in young males more than females and is associated with oral or genital ulcers. Retinal necrosis is associated with dense vitritis, retinal vasculitis and retinal vascular occlusion. Foci of retinitis may mimic areas of infiltration by PIOL and may resolve spontaneously. Papillitis should be distinguished from papilledema due to sinus thrombophlebitis or other intracranial pathology. Diagnosis is based on a set of criteria defined by the International Study Group for Behçet’s disease.52 HLA-B51 may be supportive but is not among the diagnostic criterion.

Atypical Fuchs Heterochromic Iridocyclitis

Fuchs heterochromic cyclitis (FHC) is typically a unilateral disease that occurs in young adults.53 It is characterized by non-granulomatous diffuse stellate fine KPs distributed on the corneal surface, mild to moderate anterior chamber inflammation, heterochromia, presence of posterior subcapsular cataract and absence of posterior synechia. Even though KPs are quite typical in patients with FHC, they may also be associated with different types of intermediate uveitis as well as PIOL. Therefore, PIOL must be considered in atypical forms of FHC, especially if there is bilateral involvement and lack of heterochromia.

Idiopathic Uveitis

This is probably the most common situation. Intermediate or posterior uveitis of unknown etiology in the elderly remains a challenging issue and PIOL needs to be excluded, especially before aggressive immunosuppressive regimens.48

Other Entities

Hodgkin’s lymphoma may masquerade as chronic posterior uveitis with variable visual outcome.54 Vitreous infiltration is significantly less impressive than what is typically seen with PIOL. Atypical forms of uveomeningitis simulating Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease and resisting to conventional anti inflammatory drugs may be due to intravascular lymphoma with CNS and ocular involvement.55 HTLV-1 associated uveitis can also mimic PIOL with mild to moderate vitritis, necrotizing retinal vasculitis and chorioretinal infiltrates; similarly cytology and molecular analyses are helpful in diagnosis.56

CONCLUSION

As evidenced by the long list of differential diagnoses, diagnosis of PIOL is a challenging task for the ophthalmologist. The most important step towards the diagnosis is clinical suspicion and a thorough ophthalmic exam aided by appropriate ancillary testing as indicated by the clinical setting depending on patient’s immune status, age, risk factors and characteristics of intraocular inflammation. Once the decision for the need for tissue diagnosis is made then appropriate steps should be taken in collaboration with the ocular pathologist, vitreo-retinal surgeon, neurologist and the oncologist (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Flowchart representing diagnostic approach by the authors. (DFE: dilated fundus exam, FA: fluorescein angiography, US: ultrasound, OCT: optical coherence tomography, IHC: immunohistochemistry, AH: aqueous humor, PPV: pars plana vitrectomy, CSF: cerebrospinal fluid, MRI: magnetic resonance imaging).

Contributor Information

H. Nida Sen, National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Bahram Bodaghi, Department of Ophthalmology, Pierre & Marie Curie University, Pitie-Salpetriere Hospital, Paris, France.

Phuc Le Hoang, Department of Ophthalmology, Pierre & Marie Curie University, Pitie-Salpetriere Hospital, Paris, France.

Robert Nussenblatt, National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

References

- 1.Chan CC, Gonzalez JA. Primary Intraocular Lymphoma. Hackensack, NJ: World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coupland SE, Damato B. Understanding intraocular lymphoma. Clin Experiment Opthalmol. 2008;26(6):564–578. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2008.01843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan CC, Wallace DJ. Intraocular lymphoma: update on diagnosis and management. Cancer Control. 2004;11(5):285–295. doi: 10.1177/107327480401100502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barr CC, Green WR, Payne JW, et al. Intraocular reticulum-cell sarcoma: clinicopathologic study of four cases and review of the literature. Surv Ophthalmol. 1975;19(4):224–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaplan HJ, Meredith TA, Aaberg TM, et al. Reclassification of intraocular reticulum cell sarcoma (histiocytic lymphoma). Immunologic characterization of vitreous cells. Arch Ophthalmol. 1980;98:707–710. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1980.01020030701010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freeman LN, Schachat AP, Knox DL, et al. Clinical features, laboratory investigations, and survival in ocular reticulum cell sarcoma. Ophthalmology. 1987;94:1631–1639. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(87)33256-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonzales JA, Chan CC. Biopsy techniques and yields in diagnosing primary intraocular lymphoma. Int Ophthalmol. 2007;27(4):241–250. doi: 10.1007/s10792-007-9065-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whitcup SM, de Smet MD, Rubin BI, et al. Intraocular lymphoma. Clinical and histopathologic diagnosis. Ophthalmology. 1993;100(9):1399–1406. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(93)31469-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peterson K, Gordon KB, Heinemann MH, et al. The clinical spectrum of ocular lymphoma. Cancer. 1993;72:843–849. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930801)72:3<843::aid-cncr2820720333>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeAngelis LM. Primary central nervous system lymphoma. Curr Opin Neurol. 1999;12:687–691. doi: 10.1097/00019052-199912000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dean JM, Novak MA, Chan CC, et al. Tumor detachments of the retinal pigment epithelium in ocular/central nervous system lymphoma. Retina. 1996;16:47–56. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199616010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cassoux N, Giron A, Bodaghi B, et al. IL-10 measurement in aqueous humor for screening patients with suspicion of primary intraocular lymphoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48(7):3253–3259. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park SS, D’Amico DJ, Foster CS. The role of invasive diagnostic testing in inflammatory eye diseases. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1994;34(3):229–38. doi: 10.1097/00004397-199403430-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siegel MJ, Dalton J, Friedman AH, et al. Ten-year experience with primary ocular ‘reticulum cell sarcoma’ (large cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma) Br J Ophthalmol. 1989;73(5):342–346. doi: 10.1136/bjo.73.5.342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levy-Clarke GA, Byrnes GA, Buggage RR, et al. Primary intraocular lymphoma diagnosed by fine needle aspiration biopsy of a subretinal lesion. Retina. 2001;21(3):281–284. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200106000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klingele TG, Hogan MJ. Ocular reticulum cell sarcoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1975;79(1):39–47. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(75)90453-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Michels RG, Knox DL, Erozan YS, et al. Intraocular reticulum cell sarcoma. Diagnosis by pars plana vitrectomy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1975;93(12):1331–1335. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1975.01010020961005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis JL, Solomon D, Nussenblatt RB, et al. Immunocytochemical staining of vitreous cells: indications, techniques, and results. Ophthalmology. 1992;99:250–256. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(92)31984-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whitcup SM, Chan CC, Buggage RR, et al. Improving the diagnostic yield of vitrectomy for intraocular lymphoma [letter; comment] Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dworkin LL, Gibler TN, Van Gelder Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction diagnosis of infectious posterior uveitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120(11):1534–1539. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.11.1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gupta V, Gupta A, Rao NA. Intraocular tuberculosis — an update. Surv Ophthalmol. 2007;52(6):561–587. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wakefield D, Zierhut M. Intraocular lymphoma: more questions than answers. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2009 Jan-Feb;17(1):6–10. doi: 10.1080/09273940902834413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tuaillon N, Chan CC. Molecular analysis of primary central nervous system and primary intraocular lymphomas. Curr Mol Med. 2001;1(2):259–272. doi: 10.2174/1566524013363915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buggage RR, Chan CC, Nussenblatt RB. Ocular manifestations of central nervous system lymphoma. Curr Opin Oncol. 2001;13(3):137–142. doi: 10.1097/00001622-200105000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gass JD, Sever RJ, Grizzard WS, et al. Multifocal pigment epithelial detachments by reticulum cell sarcoma. A characteristic funduscopic picture. Retina. 1984;4(3):135–143. doi: 10.1097/00006982-198400430-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coupland SE, Bechrakis NE, Anastassiou G, et al. Evaluation of vitrectomy specimens and chorioretinal biopsies in the diagnosis of primary intraocular lymphoma in patients with Masquerade syndrome. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2003 Oct;241(10):860–870. doi: 10.1007/s00417-003-0749-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chan CC, Buggage RR, Nussenblatt RB. Intraocular Lymphoma. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2002;13(6):411–418. doi: 10.1097/00055735-200212000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merle-Béral H, Davi F, Cassoux N, et al. Biological diagnosis of primary intraocular lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2004;124(4):469–473. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Char DH, Ljung BM, Deschênes J, et al. Intraocular lymphoma: immunological and cytological analysis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1988;72(12):905–911. doi: 10.1136/bjo.72.12.905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilson DJ, Braziel R, Rosenbaum JT. Intraocular lymphoma. Immunopathologic analysis of vitreous biopsy specimens. Arch Ophthalmol. 1992;110(10):1455–1458. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1992.01080220117032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.White VA, Gascoyne RD, Paton KE. Use of the polymerase chain reaction to detect B- and T-cell gene rearrangements in vitreous specimens from patients with intraocular lymphoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117(6):761–765. doi: 10.1001/archopht.117.6.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoffman PM, McKelvie P, Hall AJ, et al. Intraocular lymphoma: a series of 14 patients with clinicopathological features and treatment outcomes. Eye. 2003;17(4):513–521. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coupland SE, Anastassiou G, Bornfeld N, et al. Primary intraocular lymphoma of T-cell type: report of a case and review of the literature. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2005;243(3):189–197. doi: 10.1007/s00417-004-0890-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hegde U, Filie A, Little RF, et al. High incidence of occult leptomeningeal disease detected by flow cytometry in newly diagnosed aggressive B-cell lymphomas at risk for central nervous system involvement: the role of flow cytometry versus cytology. Blood. 2005;105(2):496–502. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davis JL, Viciana AL, Ruiz P. Diagnosis of intraocular lymphoma by flow cytometry. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;124(3):362–372. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70828-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Benjamin D, Park CD, Sharma V. Human B cell interleukin 10. Leuk Lymphoma. 1994;12(3–4):205–210. doi: 10.3109/10428199409059591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wolf LA, Reed GF, Buggage RR, et al. Vitreous cytokine levels. Ophthalmology. 2003;110(8):1671–1672. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00811-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sen HN, Chan CC, Byrnes G, et al. Intravitreal methotrexate resistance in a patient with primary intraocular lymphoma. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2008;16(1):29–33. doi: 10.1080/09273940801899764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shen DF, Zhuang Z, LeHoang P, et al. Utility of microdissection and polymerase chain reaction for the detection of immunoglobulin gene rearrangement and translocation in primary intraocular lymphoma. Ophthalmology. 1998;105(9):1664–1669. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(98)99036-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Emmert-Buck MR, Bonner RF, Smith PD, et al. Laser capture microdissection. Science. 1996 Nov 8;274:5289, 998–1001. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5289.998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chan CC. Molecular pathology of primary intraocular lymphoma. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2003;101(0):275–292. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gorochov G, Parizot C, Bodaghi B, et al. Characterization of vitreous B-cell infiltrates in patients with primary ocular lymphoma, using CDR3 size polymorphism analysis of antibody transcripts. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44(12):5235–5241. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cassoux N, Merle-Beral H, Leblond V, et al. Ocular and central nervous system lymphoma: clinical features and diagnosis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2000;8:243–250. doi: 10.1076/ocii.8.4.243.6463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Drancourt M, Berger P, Terrada C, et al. High prevalence of fastidious bacteria in 1520 cases of uveitis of unknown etiology. Medicine (Baltimore) 2008;87:167–176. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e31817b0747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Balansard B, Bodaghi B, Cassoux N, et al. Necrotising retinopathies simulating acute retinal necrosis syndrome. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89:96–101. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.042226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shen DF, Herbort CP, Tuaillon N, et al. Detection of Toxoplasma gondii DNA in primary intraocular B-cell lymphoma. Mod Pathol. 2001;14:995–999. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Drancourt M, Raoult D, Lepidi H, et al. Culture of Tropheryma whippelii from the vitreous fluid of a patient presenting with unilateral uveitis. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:1046–1047. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-12-200312160-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gupta R, Murray PI. Chronic non-infectious uveitis in the elderly: epidemiology, pathophysiology and management. Drugs Aging. 2006;23:535–558. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200623070-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reeves SW, Sloan FA, Lee PP, et al. Uveitis in the elderly: epidemiological data from the National Long-term Care Survey Medicare Cohort. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:302–307. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Evans M, Sharma O, LaBree L, et al. Differences in clinical findings between Caucasians and African Americans with biopsy-proven sarcoidosis. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:325–333. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.05.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim I, LEE S. Choroidal Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2000;78:97–100. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.2000.078001097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Criteria for diagnosis of Behcet’s disease. International Study Group for Behcet’s Disease. Lancet. 1990;335:1078–1080. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mohamed Q, Zamir E. Update on Fuchs’ uveitis syndrome. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2005;16:356–363. doi: 10.1097/01.icu.0000187056.29563.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Towler H, de la Fuente M, Lightman S. Posterior uveitis in Hodgkin’s disease. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol. 1999;27(5):326–330. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1606.1999.00224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pahk PJ, Todd DJ, Blaha GR, et al. Intravascular lymphoma masquerading as Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2008;16:123–126. doi: 10.1080/09273940802023810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Buggage RR. Ocular manifestations of human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 infection. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2003;14(6):420–425. doi: 10.1097/00055735-200312000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]