Abstract

Background and objectives: The association of social support with outcomes in ESRD, overall and by peritoneal dialysis (PD) versus hemodialysis (HD), remains understudied.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements: In an incident cohort of 949 dialysis patients from 77 US clinics, we examined functional social support scores (scaled 0 to 100 and categorized by tertile) both overall and in emotional, tangible, affectionate, and social interaction subdomains. Outcomes included 1-year patient satisfaction and quality of life (QOL), dialysis modality switching, and hospitalizations and mortality (through December 2004). Associations were examined using overall and modality-stratified multivariable logistic, Poisson, and Cox proportional hazards models.

Results: We found that mean social support scores in this population were higher in PD versus HD patients (overall 80.5 versus 76.1; P < 0.01). After adjustment, highest versus lowest overall support predicted greater 1-year satisfaction and QOL in all patients (odds ratio 2.47 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.18 to 5.15] and 2.06 [95% CI 1.31 to 3.22] for recommendation of center and higher mental component summary score, respectively). In addition, patients were less likely to be hospitalized (incidence rate ratio 0.86; 95% CI 0.77 to 0.98). Results were similar with subdomain scores. Modality switching and mortality did not differ by social support in these patients, and associations of social support with outcomes did not generally differ by dialysis modality.

Conclusions: Social support is important for both HD and PD patients in terms of greater satisfaction and QOL and fewer hospitalizations. Intervention studies to possibly improve these outcomes are warranted.

Social support is widely thought to have the potential to improve patients' health outcomes. Perceived social support has been shown to be associated with improved health outcomes in a variety of chronic health conditions (1), including heart disease (2,3) and diabetes (4); however, the association of social support with health outcomes remains an understudied problem in chronic kidney disease and ESRD, with little previous evidence of an association of social support with improved outcomes (5–8). Most previous studies of social support have focused on mortality alone, and results have been contradictory (7,8).

Better social support could increase dialysis patients' satisfaction with their care and their overall perceived health-related quality of life (HRQOL). In addition, social support could provide the means for better treatment, medication adherence, and nutrition, leading to better clinical outcomes. Among those receiving dialysis, levels of social support and associations of social support with outcomes may differ between the dialysis modalities, because hemodialysis (HD) and peritoneal dialysis (PD) differ dramatically in the amount of self-care required.

In a national cohort of incident HD and PD patients, we assessed the level of social support overall and by dialysis modality. We also examined the associations of social support with patient satisfaction, HRQOL, and clinical outcomes, including modality switching, hospital admissions, and all-cause mortality. Finally, we assessed whether these associations differed by dialysis modality.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

Our cohort for this study consisted of 949 incident dialysis patients (enrolled October 1995 through June 1998) who were treated at 77 not-for-profit, free-standing outpatient dialysis clinics in 19 states throughout the United States. The study cohort was assembled from the previously described Choices for Healthy Outcomes in Caring for End-Stage Renal Disease (CHOICE) study (9) cohort.

Data Collection

Social Support.

Patients' social support was assessed by a validated cross-sectional, self-reported questionnaire, the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Social Support Survey (10), at study enrollment. The survey consists of 19 items that measure functional social support in four dimensions: Emotional/informational, tangible, affectionate, and positive social interaction (Table 1). Overall and domain-specific scores were calculated by averaging across all and domain-specific items, respectively, and transforming the average scores to a 100-point scale: 100 * [(average score − minimum possible score)/(maximum possible score − minimum possible score)]. At least two item responses within each subdomain were required to calculate subdomain scores, and scores in all four dimensions were required to calculate an overall functional support score.

Table 1.

MOS social support survey instrument items

| Support Domain | Items |

|---|---|

| Emotional/informational | Someone you can count on to listen to you when you need to talk |

| Someone to give you information to help you understand a situation | |

| Someone to give you good advice about a crisis | |

| Someone to confide in or talk to about yourself and your problems | |

| Someone whose advice you really want | |

| Someone to share your most private worries and fears with | |

| Someone to turn to for suggestions about how to deal with a personal problem | |

| Someone who understands your problems | |

| Tangible | Someone to help you if you were confined to bed |

| Someone to take you to the doctor if you needed it | |

| Someone to prepare your meals if you were unable to do it yourself | |

| Someone to help with daily chores if you were sick | |

| Affectionate | Someone who shows you love and affection |

| Someone to love and make you feel wanted | |

| Someone who hugs you | |

| Positive social interaction | Someone to have a good time with |

| Someone to get together with for relaxation | |

| Someone to do something enjoyable with | |

| Additional itema | Someone to do things with to help you get your mind off things |

The overall question was phrased, “How often is each of the following kinds of support available to you if you need it?” Possible responses were “none of the time,” “a little of the time,” “some of the time,” “most of the time,” and “all of the time.” Adapted from reference (10), with permission.

Included in overall social support score calculation.

Patient Satisfaction.

Patient satisfaction was measured as part of the CHOICE Health Experience Questionnaire (CHEQ) (11), a patient self-report questionnaire that was administered at study enrollment and at 1 year. Patients were asked, “How would you rate the quality of care you have received as a dialysis patient, overall?” and, “Would you recommend your dialysis center to a friend or relative who needs dialysis?” Patients responded on a five-point scale with categories of excellent/definitely yes, very good/probably yes, good/not sure, fair/probably not, or poor/definitely not.

HRQOL.

HRQOL scores at baseline and 1 year were also obtained from the CHEQ (11), which included the SF-36 health survey items (12). Physical component summary (PCS) and mental component summary (MCS) scores were calculated from the scores on the SF-36 domains (12).

Modality Switching.

Baseline dialysis modality was defined as the modality (PD or HD) in use at 4 weeks after enrollment in the study and was obtained from clinic records. Patients were considered to have switched modality when they remained on the new modality for at least 30 days (13). Patients were censored for time to switch at death, transplantation, or last date of follow-up (December 31, 2004).

Hospitalization.

Number of hospital admissions was determined from US Renal Data System inpatient files. Follow-up time was calculated from study enrollment or start of Medicare coverage to death, transplantation, or last date of follow-up (December 31, 2004); time during hospital admissions was excluded.

All-Cause Mortality.

All-cause mortality information was ascertained from National Death Index records, clinic reports, medical records, and Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (death notification forms and Social Security records). Follow-up for mortality continued until death, transplantation, or the last follow-up date (December 31, 2004).

Other Variables.

Data on patients' demographics (age, gender, and race) and socioeconomic status (education, employment, and marital status) were collected from a baseline self-report questionnaire. Presence and severity of comorbid conditions were assessed at baseline using the Index of Coexistent Disease (14,15). Laboratory values (albumin, creatinine, and hemoglobin) and height and weight (used to calculate body mass index) were obtained from patients' records at baseline and from Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Form 2728, respectively. Referral to a nephrologist was obtained as described previously (16).

Statistical Analysis

The overall distributions of social support domain scores were obtained and compared by dialysis modality using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. Patient characteristics were examined by tertile of baseline social support score, using Pearson χ2 tests for categorical variables and ANOVA for continuous variables. For associations of social support with outcomes, we compared highest and lowest tertiles of social support. Satisfaction scores at 1 year were dichotomized as highest versus other ratings, and HRQOL scores at 1 year were dichotomized by the median score; odds ratios from logistic regression models were used to assess the relationships between social support and these outcomes. Cox proportional hazards models were used to obtain relative hazards of modality switching and all-cause mortality for social support scores; Poisson models were used to obtain incidence rate ratios (IRRs). Variables were chosen as covariates for the adjusted models when they were potential confounders. Because some variables could be considered in the causal pathway (e.g., marital status, dialysis modality, baseline satisfaction/HRQOL scores), variables were added stepwise. Sensitivity analyses, including interactions by modality; examination of hospitalizations, mortality, and modality switching within the first 6 months and first year; and examination of change from baseline to 1 year in HRQOL and satisfaction, were also performed. We accounted for possible dependence of observations within clinics by performing modeling on the basis of robust variance–covariance matrices. All analyses were performed using Stata 10.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX).

Results

Participant Characteristics and Social Support Scores

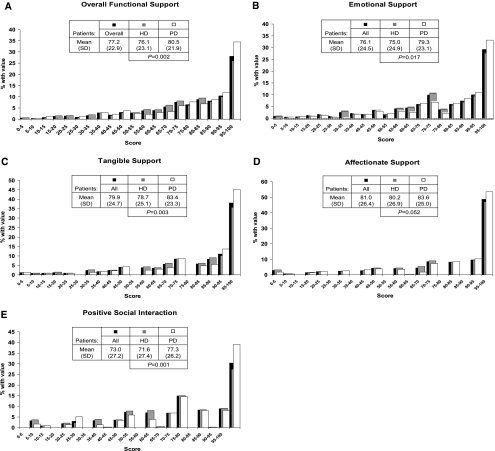

A total of 949 (91.2%) of 1041 patients who were treated at 77 clinics in 19 states provided sufficient information to compute both an overall social support score and all four social support subdomain scores. Figure 1 shows the distributions of social support scores in our cohort. Scores of both overall functional social support (Figure 1A) and all four subdomains of social support (Figure 1, B through E) were highly right-skewed, with mean (95% confidence interval [CI]) social support scores as follows: Overall 77.2 (75.7 to 78.6), emotional 76.1 (74.5 to 77.6), tangible 79.9 (78.3 to 81.4), affectionate 81.0 (79.3 to 82.7), and social interaction 73.0 (71.3 to 74.8). Scores were higher for PD versus HD patients for all social support domains; for affectionate support, the difference was marginally significant (P = 0.05).

Figure 1.

Distributions of functional social support scores, overall and by dialysis modality: Overall functional social support (A), emotional support (B), tangible support (C), affectionate support (D), and positive social interaction (E). All scores are scaled 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating higher level of social support in domain indicated. P for HD versus PD, by Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Baseline patient characteristics by tertile of overall social support score are shown in Table 2. Having social support scores in the highest tertile was statistically significantly associated with female gender, white race, married status, greater chance of being treated with PD, greater satisfaction with care, and higher MCS score; conversely, these participants also had greater comorbidity than those with lower scores. These associations were similar for the subdomains of social support (data not shown).

Table 2.

Baseline dialysis patient characteristics, overall and by tertile of overall functional social support score

| Baseline Characteristic | n | All | Tertile of Functional Support Score |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Middle | High | Pa | |||

| Range of overall functional support score | – | 0.0 to 100.0 | 0.0 to 72.4 | 73.6 to 92.1 | 92.2 to 100.0 | – |

| Demographic | ||||||

| age (years; mean ± SD) | 949 | 57.7 ± 14.8 | 58.2 ± 14.5 | 57.4 ± 15.0 | 57.5 ± 14.9 | 0.76 |

| male gender (%) | 949 | 54.1 | 58.9 | 48.2 | 55.0 | 0.03 |

| white race (%) | 949 | 66.9 | 62.0 | 67.4 | 71.3 | 0.04 |

| graduated high school (%) | 942 | 70.7 | 71.9 | 70.1 | 70.1 | 0.85 |

| employed (%) | 949 | 13.7 | 13.0 | 11.8 | 16.3 | 0.24 |

| married (%) | 948 | 56.2 | 42.1 | 56.9 | 69.6 | <0.001 |

| Clinical | ||||||

| ICED (% score of 3) | 948 | 29.5 | 25.6 | 26.5 | 36.4 | 0.01 |

| BMI (mean ± SD) | 884 | 27.2 ± 6.8 | 27.4 ± 6.8 | 26.6 ± 6.9 | 27.6 ± 6.6 | 0.14 |

| HD (%) | 949 | 75.2 | 80.1 | 75.1 | 70.6 | 0.02 |

| late evaluation (% <4 months from first nephrologist visit to dialysis) | 790 | 30.1 | 31.8 | 33.5 | 25.4 | 0.10 |

| Laboratory | ||||||

| albumin (g/dl; mean ± SD) | 927 | 3.63 ± 0.38 | 3.65 ± 0.37 | 3.62 ± 0.35 | 3.62 ± 0.40 | 0.37 |

| creatinine (mg/dl; mean ± SD) | 927 | 7.29 ± 2.59 | 7.40 ± 2.51 | 7.24 ± 2.69 | 7.21 ± 2.58 | 0.63 |

| hemoglobin (g/dl; mean ± SD) | 920 | 10.8 ± 1.3 | 10.8 ± 1.3 | 10.7 ± 1.2 | 10.8 ± 1.4 | 0.81 |

| Satisfaction and HRQOL | ||||||

| definite recommendation (%) | 884 | 81.8 | 74.1 | 85.2 | 86.1 | <0.001 |

| excellent overall care (%) | 884 | 65.7 | 56.7 | 68.4 | 72.0 | <0.001 |

| MCS score (mean ± SD) | 843 | 46.6 ± 11.6 | 44.3 ± 11.7 | 45.9 ± 11.2 | 49.4 ± 11.3 | <0.001 |

| PCS score (mean ± SD) | 843 | 32.7 ± 10.0 | 32.5 ± 9.4 | 32.1 ± 10.0 | 33.5 ± 10.5 | 0.21 |

ICED, Index of Coexistent Disease.

By ANOVA (continuous variables) or χ2 test (categorical variables) across tertile of functional social support score.

Association of Social Support with Dialysis Patient Satisfaction and HRQOL

Table 3 shows the association of highest versus lowest social support scores with patient satisfaction and HRQOL at 1 year. Those with overall functional social support scores in the highest tertile were approximately 1.5 times more likely to rate their quality of care at 1 year as “excellent”; among the four subdomains of social support, only higher positive social interaction was statistically significantly associated with excellent ratings of care. For recommendation of center, those with scores in the highest tertile were 2.5 times more likely “definitely” to recommend their center at 1 year, and this association held for overall functional social support and all four subdomains (Table 3). For HRQOL, the highest level of social support was associated with greater MCS scores (approximately twice as likely to have higher MCS at 1 year) for overall support and all four subdomains. For PCS, results were not statistically significant, except for highest level of tangible support being associated with 1.7-fold greater chance of having a high PCS score at 1 year (Table 3).

Table 3.

Overall association of high versus low level of social support with dialysis patient satisfaction and HRQOL at 1 year

| Domain/Model | Highest versus Lowest Tertile of Social Support (OR [95% CI]) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-Year Patient Satisfaction |

1-Year Patient HRQOL |

|||

| Overall Care “Excellent” versus Other Rating | Recommending Center “Definitely” versus Other Rating | MCS High (>Median) versus Low Score | PCS High (>Median) versus Low Score | |

| Overall functional social support | ||||

| unadjusted | 1.62 (1.15 to 2.28)a | 2.08 (1.17 to 3.68)a | 1.77 (1.19 to 2.63)a | 1.29 (0.90 to 1.85) |

| model 1 | 1.58 (1.12 to 2.23)a | 2.09 (1.18 to 3.68)a | 1.87 (1.26 to 2.76)a | 1.28 (0.91 to 1.80) |

| model 2 | 1.64 (1.13 to 2.37)a | 2.49 (1.24 to 4.97)a | 2.24 (1.48 to 3.40)a | 1.34 (0.91 to 1.98) |

| model 3 | 1.64 (1.10 to 2.43)a | 2.44 (1.21 to 4.93)a | 2.20 (1.42 to 3.42)a | 1.37 (0.91 to 2.06) |

| model 4 | 1.45 (0.97 to 2.16) | 2.47 (1.18 to 5.15)a | 2.06 (1.31 to 3.22)a | 1.53 (1.02 to 2.30)a |

| Emotional/informational support | ||||

| unadjusted | 1.59 (1.12 to 2.20)a | 2.46 (1.40 to 4.33)a | 1.76 (1.04 to 2.99)a | 1.28 (0.86 to 1.89) |

| model 1 | 1.53 (1.08 to 2.17)a | 2.46 (1.41 to 4.31)a | 1.87 (1.13 to 3.07)a | 1.31 (0.88 to 1.95) |

| model 2 | 1.50 (1.06 to 2.13)a | 2.62 (1.38 to 4.98)a | 1.99 (1.20 to 3.31)a | 1.34 (0.88 to 2.06) |

| model 3 | 1.51 (1.01 to 2.25)a | 2.66 (1.38 to 5.12)a | 1.94 (1.13 to 3.33)a | 1.32 (0.88 to 1.99) |

| model 4 | 1.28 (0.85 to 1.94) | 2.78 (1.42 to 5.46)a | 1.82 (1.08 to 3.10)a | 1.46 (0.99 to 2.16) |

| Tangible support | ||||

| unadjusted | 1.27 (0.87 to 1.86) | 1.83 (1.12 to 2.97)a | 1.83 (1.26 to 2.65)a | 1.51 (1.02 to 2.22)a |

| model 1 | 1.24 (0.87 to 1.78) | 1.87 (1.13 to 3.10)a | 1.56 (1.16 to 2.11)a | 1.59 (1.11 to 2.27)a |

| model 2 | 1.18 (0.83 to 1.66) | 2.10 (1.22 to 3.61)a | 1.78 (1.31 to 2.42)a | 1.59 (1.07 to 2.36)a |

| model 3 | 1.14 (0.79 to 1.65) | 2.01 (1.16 to 3.49)a | 1.74 (1.27 to 2.37)a | 1.62 (1.09 to 2.41)a |

| model 4 | 1.06 (0.69 to 1.63) | 2.19 (1.21 to 3.98)a | 1.65 (1.17 to 2.32)a | 1.73 (1.15 to 2.60)a |

| Affectionate support | ||||

| unadjusted | 1.79 (1.32 to 2.41)a | 1.98 (1.35 to 2.91)a | 1.51 (1.11 to 2.04)a | 0.91 (0.67 to 1.24) |

| model 1 | 1.71 (1.23 to 2.38)a | 1.92 (1.30 to 2.83)a | 1.56 (1.16 to 2.11)a | 0.91 (0.69 to 1.21) |

| model 2 | 1.70 (1.15 to 2.51)a | 2.11 (1.34 to 3.32)a | 1.78 (1.31 to 2.42)a | 0.93 (0.67 to 1.30) |

| model 3 | 1.77 (1.19 to 2.63)a | 2.14 (1.33 to 3.43)a | 1.74 (1.27 to 2.37)a | 0.94 (0.66 to 1.35) |

| model 4 | 1.60 (0.96 to 2.64) | 2.01 (1.24 to 3.24)a | 1.65 (1.17 to 2.32)a | 0.94 (0.66 to 1.35) |

| Positive social interaction | ||||

| unadjusted | 1.81 (1.33 to 2.45)a | 1.76 (1.04 to 2.99)a | 1.70 (1.22 to 2.38)a | 1.18 (0.83 to 1.67) |

| model 1 | 1.72 (1.24 to 2.39)a | 1.76 (1.02 to 3.05)a | 1.80 (1.30 to 2.51)a | 1.11 (0.80 to 1.56) |

| model 2 | 1.73 (1.19 to 2.50)a | 1.99 (1.08 to 3.67)a | 2.09 (1.55 to 2.50)a | 1.08 (0.76 to 1.55) |

| model 3 | 1.69 (1.14 to 2.49)a | 1.92 (1.02 to 3.63)a | 2.06 (1.52 to 2.79)a | 1.10 (0.78 to 1.54) |

| model 4 | 1.62 (1.05 to 2.50)a | 2.17 (1.11 to 4.27)a | 1.93 (1.39 to 2.68)a | 1.14 (0.82 to 1.59) |

Model 1: Age, gender, and race (white versus nonwhite); model 2: Model 1 + marital status; model 3: Model 2 + baseline dialysis modality and comorbidity; model 4: Model 3 + baseline satisfaction/HRQOL score. OR, odds ratio.

P < 0.05.

Overall, adjustment for demographics, marital status, dialysis modality, and comorbidity did not change the associations seen; adjustment for the baseline satisfaction or HRQOL did often render the results nonstatistically significant, but the magnitude of the associations remained (Table 3). Changes in score from baseline to 1 year for satisfaction and HRQOL were modest and not associated with baseline social support (data not shown). Further adjustment for late evaluation (referred to a nephrologist <4 months before dialysis) did not substantially change any of the associations of social support with patient satisfaction or HRQOL (data not shown).

Association of Social Support with Clinical Outcomes in Dialysis Patients

Of the clinical patient outcomes examined, only hospitalization was significantly associated with social support, with a nearly 15% decreased risk for hospital admission among those with highest versus lowest social support scores (Table 4). This association was statistically significant for overall, emotional, and affectionate support. Adjustment for demographics, marital status, dialysis modality, comorbidity, and albumin did not change the associations seen; again, further adjustment for late evaluation did not substantially change the associations of social support with decreased risk for hospitalization (data not shown). The association was consistent when hospitalizations were examined in the first 6 months (IRR 0.77; 95% CI 0.56 to 1.06) and the first year (IRR 0.83; 95% CI 0.67 to 1.02) only. Modality switching and all-cause mortality were not associated with social support either before or after adjustment for confounders (Table 4). A nonstatistically significant association of higher social support with lower first-year mortality only was seen (relative hazard 0.67; 95% CI 0.40 to 1.13), whereas the association of switching with social support was not different at 6 months or 1 year from that seen over the entire follow-up. Dialysis modality–stratified analyses of the association of patient outcomes with overall functional social support provided little evidence of effect modification by modality for any outcome, with the exception of a marginally significant (Pinteraction = 0.07) effect for recommendation of center at 1 year, with HD patients being more than three times more likely to recommend their center with higher social support but no association among PD patients.

Table 4.

Overall association of high versus low level of social support with dialysis patient clinical outcomes

| Model | Highest versus Lowest Tertile of Social Support |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Modality Switching (RH [95% CI]) | Hospitalization (IRR [95% CI]) | Mortality (RH [95% CI]) | |

| Overall functional social support | |||

| unadjusted | 1.36 (0.73 to 2.54) | 0.83 (0.73 to 0.94)a | 0.97 (0.75 to 1.25) |

| model 1 | 1.23 (0.65 to 2.32) | 0.82 (0.72 to 0.92)a | 0.91 (0.75 to 1.10) |

| model 2 | 1.26 (0.66 to 2.41) | 0.85 (0.75 to 0.96)a | 0.93 (0.75 to 1.41) |

| model 3 | 1.07 (0.56 to 2.04) | 0.86 (0.76 to 0.97)a | 0.91 (0.73 to 1.13) |

| model 4 | 1.03 (0.57 to 1.83) | 0.86 (0.77 to 0.98)a | 0.94 (0.76 to 1.16) |

| Emotional support | |||

| unadjusted | 1.13 (0.65 to 1.98) | 0.86 (0.76 to 0.98)a | 1.01 (0.78 to 1.31) |

| model 1 | 1.01 (0.57 to 1.81) | 0.85 (0.75 to 0.96)a | 0.97 (0.79 to 1.19) |

| model 2 | 0.99 (0.55 to 1.80) | 0.86 (0.76 to 0.98)a | 0.99 (0.80 to 1.22) |

| model 3 | 0.89 (0.48 to 1.65) | 0.88 (0.77 to 0.99)a | 0.99 (0.78 to 1.27) |

| model 4 | 0.83 (0.48 to 1.45) | 0.87 (0.77 to 0.98)a | 1.00 (0.79 to 1.27) |

| Tangible support | |||

| unadjusted | 1.44 (0.83 to 2.52) | 0.89 (0.77 to 1.02) | 1.09 (0.91 to 1.30) |

| model 1 | 1.44 (0.83 to 2.51) | 0.88 (0.75 to 1.02) | 0.98 (0.84 to 1.14) |

| model 2 | 1.49 (0.83 to 2.59) | 0.90 (0.77 to 1.06) | 1.01 (0.87 to 1.18) |

| model 3 | 1.37 (0.76 to 2.45) | 0.91 (0.78 to 1.08) | 1.01 (0.86 to 1.19) |

| model 4 | 1.26 (0.75 to 2.12) | 0.91 (0.77 to 1.08) | 1.03 (0.87 to 1.21) |

| Affectionate support | |||

| unadjusted | 1.27 (0.67 to 2.41) | 0.85 (0.76 to 0.96)a | 0.90 (0.74 to 1.08) |

| model 1 | 1.15 (0.61 to 2.15) | 0.82 (0.75 to 0.93)a | 0.83 (0.71 to 0.96) |

| model 2 | 1.14 (0.61 to 2.14) | 0.84 (0.73 to 0.96)a | 0.83 (0.71 to 0.98) |

| model 3 | 1.11 (0.63 to 1.96) | 0.86 (0.74 to 0.98)a | 0.85 (0.73 to 0.99) |

| model 4 | 1.10 (0.63 to 1.93) | 0.86 (0.75 to 0.99)a | 0.89 (0.77 to 1.04) |

| Positive social interaction | |||

| unadjusted | 1.19 (0.71 to 2.00) | 0.83 (0.71 to 0.97)a | 0.96 (0.76 to 1.20) |

| model 1 | 1.06 (0.58 to 1.92) | 0.84 (0.72 to 0.98)a | 0.89 (0.71 to 1.12) |

| model 2 | 1.05 (0.57 to 1.94) | 0.84 (0.72 to 0.99)a | 0.92 (0.72 to 1.17) |

| model 3 | 0.87 (0.53 to 1.41) | 0.87 (0.75 to 1.02) | 0.92 (0.71 to 1.18) |

| model 4 | 0.85 (0.52 to 1.39) | 0.87 (0.75 to 1.02) | 0.95 (0.77 to 1.19) |

Model 1: Age, gender, and race (white versus nonwhite); model 2: Model 1 + marital status; model 3: Model 2 + baseline dialysis modality and comorbidity; model 4: Model 3 + baseline albumin. IRR, incidence rate ratio; RH, relative hazard.

P < 0.05.

Discussion

We found that social support scores were high in our cohort and that scores were higher in PD than in HD patients. Higher social support, regardless of domain, was associated with patient-centered outcomes, including greater patient satisfaction and HRQOL and reduced hospitalization; however, mortality and modality switching were not associated with social support.

The mean scores in our cohort were generally higher (by 7 to 10 points) than the scores reported in the cohort of 19- to 95-year-olds who had one of four chronic conditions (coronary heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, and depression) and with whom the MOS survey was developed (10). The higher scores in our cohort may be due to more thoughtful consideration of all aspects of social support by those who were undergoing an intensive treatment such as dialysis, or it could be that higher social support may have provided a survival advantage to those with earlier stage disease. It also possible that the higher scores seen here reflect a “healthy cohort” effect. As expected, level of social support at baseline was higher for those who were treated with PD versus HD; this is likely due to the strong influence of perceived social support on patient selection of dialysis modality (17,18).

Previous studies have shown that social support is an important determinant of perceived HRQOL in patients with ESRD (19,20). Similarly, we found that, even after adjustment, having the highest versus lowest level of social support was associated with greater 1-year satisfaction and HRQOL. These associations generally persisted after adjustment for baseline satisfaction and HRQOL, showing that the association of social support with these measures continues over time. In light of these results and because patients believe lack of psychosocial support to be a top priority for both clinical care and research in chronic kidney disease (21,22), interventions to increase support could potentially provide dramatic benefits for satisfaction and HRQOL among those with ESRD.

Among the clinical outcomes examined, lower hospitalization rates were associated with highest versus lowest levels of social support (15% reduction associated with greater overall social support). Many hospitalizations of dialysis patients are due to infections, fluid overload, and other issues that could be treated on an outpatient basis if caught early, which may be more likely for patients whose social networks are likely to recognize health changes and encourage treatment-seeking behavior. Also, patients with greater levels of social support may be more likely to adhere to treatment, medications, and diet, as has been shown for postacute coronary syndrome (23), which could prevent certain complications that lead to hospitalization. Lower hospitalization rates could result in substantial cost savings for an already overburdened health care system, given that inpatient admissions of patients with ESRD from 2003 to 2007 cost the US health care system approximately $33 billion, approximately 35% of the total Medicare expenditure for ESRD during the same period (24).

Modality switching was not influenced by social support in this cohort. Those who were on PD had higher social support scores than did those who were on HD, likely reflecting the influence of social support on initial modality selection (17,18); however, it may be that the reasons for switching over time, such as recurrent infections, may be more strongly biologically mediated, particularly for PD patients; in fact, patient choice was not cited as one of the reasons for switching among PD patients in this cohort (13).

Mortality was not associated with level of social support in this cohort. Again, it is likely that biological factors that lead to the progression of cardiovascular disease (the leading cause of death in dialysis patients) and to death may outweigh the effects of social support over time. Previous studies of social support in Chinese PD patients (25) and of perceived family support in a small study (n = 78) of in-center HD patients (26) showed significant associations with lower mortality; however, a larger US study showed that giving, not receiving, social support was associated with lower mortality (27). Similarly, a Dutch study showed that the discrepancy between expected and received social support but not level of social interaction was associated with lower mortality (8). Thus, our results do not contradict many of the previous studies of the association of similarly measured social support with mortality. Studies of other life-limiting conditions, including digestive system (28) and lung (29) cancers, also showed no association of social support with mortality, despite positive associations with HRQOL.

In general, we found no differences in the association of outcomes, including mortality, with social support between HD and PD patients, which has been shown previously in the Dutch Netherlands Cooperative Study on the Adequacy of Dialysis 2 (NECOSAD-2) study (8). The lack of difference in outcomes suggests that social support plays its most important role in selection of modality but thereafter does not affect outcomes differently by dialysis modality.

Because improving social support is likely to improve satisfaction and HRQOL drastically and to reduce hospitalizations and associated costs for dialysis patients, possible interventions should be considered and tested. Although support from family and friends would be difficult to modify, certain types of support, including peer and religious (30) support, could be provided or encouraged by the medical team. Caregiver interventions may be more effective than patient-level interventions in populations with limited life expectancy, including patients with dementia (31).

This study has several limitations. First, our social support scores may not represent the average US dialysis patient; however, because we examined highest versus lowest social support in association with outcomes, we believe that we have captured the extremes of social support that the average dialysis provider is likely to see and recognize. Second, we know that depression is common in patients with ESRD—prevalence of 10 to 30% (32)—and likely has a mediating, bidirectional association with both social support and outcomes, but we did not have adequate data to examine this issue. Third, social support, which may not remain stable over time, was measured only once; however, analyses of outcomes more proximal to measurement of social support showed generally similar results. Fourth, we examined functional social support only. Structural support, such as having a spouse or number of friends, may affect outcomes as well, although we found that adjustment for marital status did not change the associations that we found. Fifth, the study may lack the statistical power to detect small differences in associations by dialysis modality. Finally, the study was observational; therefore, cause cannot be established and possible residual bias cannot be excluded.

Conclusions

Overall, higher levels of support at the start of dialysis were associated with lower risk for hospitalization as well as greater satisfaction and HRQOL at 1 year; however, social support was not associated with modality switching or all-cause mortality, and associations of social support with outcomes generally did not differ by dialysis modality. Because both HD and PD patients could benefit substantially in terms of QOL with greater social support and because such support could lead to substantially reduced hospitalization-associated costs, all dialysis patients should be targeted for social support intervention studies.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by award R01DK080123 from the National Institute Of Diabetes And Digestive And Kidney Diseases. N.R.P. was supported by grant K24DK02643 from the National Institute Of Diabetes And Digestive And Kidney Diseases.

This study was presented in part at the annual meeting of the American Society of Nephrology, October 27 through November 1, 2009; San Diego, CA.

We thank the patients, staff, laboratories, and medical directors of the participating clinics at DCI, New Haven CAPD, and St. Raphael's Hospital who contributed to the study.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute Of Diabetes And Digestive And Kidney Diseases or the National Institutes of Health.

Access to UpToDate on-line is available for additional clinical information at http://www.cjasn.org/

References

- 1.House JS, Landis KR, Umberson D: Social relationships and health. Science 241: 540–545, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luttik ML, Jaarsma T, Moser D, Sanderman R, van Veldhuisen DJ: The importance and impact of social support on outcomes in patients with heart failure: An overview of the literature. J Cardiovasc Nurs 20: 162–169, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lett HS, Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, Strauman TJ, Robins C, Sherwood A: Social support and coronary heart disease: Epidemiologic evidence and implications for treatment. Psychosom Med 67: 869–878, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Dam HA, van der Horst FG, Knoops L, Ryckman RM, Crebolder HF, van den Borne BH: Social support in diabetes: A systematic review of controlled intervention studies. Patient Educ Couns 59: 1–12, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cukor D, Cohen SD, Peterson RA, Kimmel PL: Psychosocial aspects of chronic disease: ESRD as a paradigmatic illness. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 3042–3055, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirchgessner J, Perera-Chang M, Klinkner G, Soley I, Marcelli D, Arkossy O, Stopper A, Kimmel PL: Satisfaction with care in peritoneal dialysis patients. Kidney Int 70: 1325–1331, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kimmel PL: Psychosocial factors in adult end-stage renal disease patients treated with hemodialysis: Correlates and outcomes. Am J Kidney Dis 35[Suppl 1]: S132–S140, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thong MS, Kaptein AA, Krediet RT, Boeschoten EW, Dekker FW: Social support predicts survival in dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 22: 845–850, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Powe NR, Klag MJ, Sadler JH, Anderson GA, Bass EB, Briggs WA, Fink NE, Levey AS, Levin NW, Meyer KB, Rubin HA, Wu AW, CHOICE Study: Choices for healthy outcomes in caring for end stage renal disease. Semin Dial 9: 9–10, 11, 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL: The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med 32: 705–714, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu AW, Fink NE, Cagney KA, Bass EB, Rubin HR, Meyer KB, Sadler JH, Powe NR: Developing a health-related quality-of-life measure for end-stage renal disease: The CHOICE health experience questionnaire. Am J Kidney Dis 37: 11–21, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ware JE, Jr: SF-36 Health Survey: Manual & Interpretation Guide, Boston, Health Institute, New England Medical Center, 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jaar BG, Plantinga LC, Crews DC, Fink NE, Hebah N, Coresh J, Kliger AS, Powe NR: Timing, causes, predictors and prognosis of switching from peritoneal dialysis to hemodialysis: A prospective study. BMC Nephrol 10: 3, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Athienites NV, Miskulin DC, Fernandez G, Bunnapradist S, Simon G, Landa M, Schmid CH, Greenfield S, Levey AS, Meyer KB: Comorbidity assessment in hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis using the index of coexistent disease. Semin Dial 13: 320–326, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miskulin DC, Martin AA, Brown R, Fink NE, Coresh J, Powe NR, Zager PG, Meyer KB, Levey AS, Medical Directors, Dialysis Clinic, Inc.: Predicting 1 year mortality in an outpatient haemodialysis population: A comparison of comorbidity instruments. Nephrol Dial Transplant 19: 413–420, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kinchen KS, Sadler J, Fink N, Brookmeyer R, Klag MJ, Levey AS, Powe NR: The timing of specialist evaluation in chronic kidney disease and mortality. Ann Intern Med 137: 479–486, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whittaker AA, Albee BJ: Factors influencing patient selection of dialysis treatment modality. ANNA J 23: 369–375, discussion 376–377, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jager KJ, Korevaar JC, Dekker FW, Krediet RT, Boeschoten EW: Netherlands Cooperative Study on the Adequacy of Dialysis (NECOSAD) Study Group: The effect of contraindications and patient preference on dialysis modality selection in ESRD patients in the Netherlands. Am J Kidney Dis 43: 891–899, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tovbin D, Gidron Y, Jean T, Granovsky R, Schnieder A: Relative importance and interrelations between psychosocial factors and individualized quality of life of hemodialysis patients. Qual Life Res 12: 709–717, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kimmel PL, Emont SL, Newmann JM, Danko H, Moss AH: ESRD patient quality of life: Symptoms, spiritual beliefs, psychosocial factors, and ethnicity. Am J Kidney Dis 42: 713–721, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Chadban S, Walker RG, Harris DC, Carter SM, Hall B, Hawley C, Craig JC: Patients' experiences and perspectives of living with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 53: 689–700, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Carter SM, Hall B, Harris DC, Walker RG, Hawley CM, Chadban S, Craig JC: Patients' priorities for health research: Focus group study of patients with chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 23: 3206–3214, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Molloy GJ, Perkins-Porras L, Bhattacharyya MR, Strike PC, Steptoe A: Practical support predicts medication adherence and attendance at cardiac rehabilitation following acute coronary syndrome. J Psychosom Res 65: 581–586, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.US Renal Data System: USRDS 2009 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States, Bethesda, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szeto CC, Chow KM, Kwan BC, Law MC, Chung KY, Leung CB, Li PK: The impact of social support on the survival of Chinese peritoneal dialysis patients. Perit Dial Int 28: 252–258, 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Christensen AJ, Wiebe JS, Smith TW, Turner CW: Predictors of survival among hemodialysis patients: Effect of perceived family support. Health Psychol 13: 521–525, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McClellan WM, Stanwyck DJ, Anson CA: Social support and subsequent mortality among patients with end-stage renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 1028–1034, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tian J, Chen ZC, Hang LF: The effects of psychosocial status of the patients with digestive system cancers on prognosis of the disease. Cancer Nurs 32: 230–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saito-Nakaya K, Nakaya N, Fujimori M, Akizuki N, Yoshikawa E, Kobayakawa M, Nagai K, Nishiwaki Y, Tsubono Y, Uchitomi Y: Marital status, social support and survival after curative resection in non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Sci 97: 206–213, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spinale J, Cohen SD, Khetpal P, Peterson RA, Clougherty B, Puchalski CM, Patel SS, Kimmel PL: Spirituality, social support, and survival in hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 1620–1627, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mitrani VB, Czaja SJ: Family-based therapy for dementia caregivers: Clinical observations. Aging Ment Health 4: 200–209, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wuerth D, Finkelstein SH, Finkelstein FO: The identification and treatment of depression in patients maintained on dialysis. Semin Dial 18: 142–146, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]