Abstract

Background and objectives: Peritoneal dialysis (PD) depends on timely and skilled placement of a PD catheter (PDC). Most PDCs are placed surgically, but little is known about the residency training of surgeons in this procedure. Inadequate residency training could limit surgical expertise in PDCs, resulting in high complication rates that discourage PD use. This study assessed surgical PDC training in the United States to explore this issue.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements: A survey was sent to program directors of 248 U.S. surgery residency programs regarding the amount of PDC training, attitudes toward PDCs, and barriers to PDC training. Results were compared between academic and private centers.

Results: Ninety-three surgery programs (38%) responded: 82% provided training in PDC and 69% were academic centers. Most surgeons placed 2 to ≤5 catheters during residency. Forty-eight percent of program directors felt that PDC training was important, 61% felt PDC training affected outcomes and increased the likelihood surgeons would place PDCs in practice, and 62% of programs expressed willingness to provide more PDC training. Lack of referrals from nephrology was the most frequently cited barrier to PDC training.

Conclusions: Although many U.S. surgery residency programs provide PDC training, this training appears inadequate. Low PD use and lack of referrals limits surgical training at most centers. Nephrologists need to develop initiatives with surgeons to improve PDC training and outcomes.

The use of peritoneal dialysis (PD) in the United States is declining. Despite comparable efficacy, improving outcomes, and cost savings compared with hemodialysis (HD), only 6% of incident and 7.2% of prevalent dialysis patients are treated with PD (1–4). Although many factors determine success on PD, a well functioning PD catheter (PDC) is absolutely necessary. Placement of a PDC by an experienced operator is strongly recommended to reduce complications (5–9). Little attention has been given to the potential effect of surgical PDC training on PD use and outcomes (1–2,10). Conversely, considerable focus has been placed on improving surgical training and outcomes for HD access (11–15).

Problems with PDC placement and malfunction can disrupt efforts to grow and develop a PD program (5,9,16–18). PDC problems frustrate patients, nurses, and nephrologists alike, leading to dissatisfaction with PD and an early switch to HD (18). PDC malfunction is second only to infection as the cause of technique failure in PD (19,20). Surgeons insert most PD catheters in the United States because most nephrologists are not trained in PDC placement (5,21–23). Unfortunately, there is a shortage of surgeons interested and skilled in performing this procedure (5).

Surgical outcomes correlate strongly with training during residency (24). Reluctance by surgeons to place PDCs and suboptimal PDC outcomes might stem from inadequate residency training. Unfortunately, little is known about the training surgeons undergo in this outwardly simple, yet critical procedure. We sought to investigate PDC training in U.S. surgery residency programs and explore surgical program directors' attitudes toward this procedure.

Materials and Methods

All 248 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)-certified general surgery residency programs in the United States were surveyed. Institutional review boards at the University of Washington and the University of Rochester approved the study procedures. Questions addressed program demographics, practice patterns, attitudes toward PDC training, and barriers to PDC training. The survey was pretested by a panel chosen by the authors. Programs without ACGME certification were excluded. The survey questions are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Survey questions given to surgical program directors

|

Before the survey, each surgery program director was e-mailed detailed information about the study. The survey was e-mailed 2 weeks later with a personal reminder message sent after 2 more weeks. We then contacted nonresponding programs by phone. Recruitment efforts ended after each program director was contacted successfully. Responses were entered directly by program directors into a secure online database or returned by fax and entered by the investigators.

Characteristics of the residency programs were evaluated with χ2 or Cochran–Armitage trend testing, as appropriate. The associations of responses from academic versus private programs were assessed with univariate logistic regressions, as were the response rates in relation to the size of the residency program. All analyses were carried out using SAS software, version 9.2 (Cary, NC).

Results

Of 248 surgery programs, 93 (38%) participated. A comparison of the responding programs and nonresponding programs is shown in Table 2. Most (69%) responding programs were at academic centers. Sixty-seven percent of programs had >20 surgical residents, most of which were academic centers (P < 0.002). A higher percentage of all U.S. academic programs participated compared with private programs. This was reflected by an odds ratio of 2.56 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.45, 4.53) for response from academic versus private centers (P = 0.001). Programs with 1 to 10 residents versus those with >20 residents had odds of 7.16 (95% CI 1.73, 48.43) of responding (P = 0.015). Although highly significant, the wide CI reflects the smaller number of programs with 10 or fewer residents. No other significant differences were observed between programs.

Table 2.

Surgery program characteristics

| Demographic Variables | Responding Programs (n = 93) | Nonresponding Programs (n = 155) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary affiliation | ||

| academic | 64 (69)a | 75 (48) |

| private hospital | 24 (26) | 72 (47) |

| military | 1 (1) | 8 (5) |

| otherb | 4 (4) | 0 (0) |

| total programs | 93 (100) | 155 (100) |

| Total number of residents | ||

| 1 to 10 | 6 (6) | 2 (1) |

| 11 to 15 | 13 (14) | 22 (14) |

| 16 to 20 | 12 (13) | 20 (13) |

| >20 | 62 (67)c | 111 (72) |

| total programs | 93 (100) | 155 (100) |

Data reported as n (%) of actual responses received. Data for nonresponding programs obtained from ACGME.

Odds ratio 2.56 (95% CI 1.45, 4.53) for response from academic versus private programs.

Responses included county hospital, hybrid, university/community hybrid, and community hospital not-for-profit.

P < 0.002 with 78% academic versus 38% private programs.

Practice patterns involving PDCs are listed in Table 3. Surgeons performed PDC placement at 90% of programs. At 76% of programs, surgeons placed most PDCs. Nephrologists placed PDCs at 15% of centers and most PDCs at only 8%. One specific surgeon placed most PDCs at 48% of centers. This was significantly more likely at private versus academic programs with an odds ratio of 3.2 (95% CI 1.03, 9.93).

Table 3.

Practice patterns at responding programs

| Question | Alla (n = 93) | Academic (n = 64) | Private (n = 24) |

|---|---|---|---|

| What service(s) place PDCs at your institution? | |||

| surgery | 83 (90) | 59 (94) | 20 (83) |

| nephrology | 14 (15) | 11 (17) | 3 (13) |

| interventional radiology | 20 (22) | 13 (21) | 6 (25) |

| I do not know | 5 (5) | 3 (5) | 1 (4) |

| not performed | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 2 (8) |

| total responses | 92 | 63 | 24 |

| Who places most PDCs at your institution? | |||

| surgery | 69 (76) | 48 (76) | 16 (70) |

| nephrology | 7 (8) | 6 (10) | 1 (4) |

| interventional radiology | 5 (5) | 2 (3) | 3 (13) |

| I do not know | 9 (10) | 7 (11) | 2 (9) |

| not performed | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) |

| total responses | 91 | 63 | 23 |

| Does one particular surgeon place most PDCs at your institution? | |||

| yes | 45 (48) | 28 (44) | 16 (67)b |

| no | 37 (40) | 29 (45) | 5 (21) |

| I do not know | 7 (8) | 6 (9) | 1 (4) |

| not applicable | 4 (4) | 1 (2) | 2 (8) |

| total responses | 93 | 64 | 24 |

| Does your program train surgical residents in PDC placement? | |||

| yes | 74 (82) | 52 (84) | 18 (75) |

| no | 16 (18) | 10 (16) | 6 (25) |

| total responses | 90 | 62 | 24 |

| On average, how many PDCs are placed by each categorical resident during training? | |||

| none at all | 3 (3) | 2 (3) | 1 (4) |

| 0 to 1 | 7 (8) | 5 (8) | 2 (9) |

| 1 to 2 | 11 (12) | 8 (13) | 1 (4) |

| 2 to 5 | 35 (38) | 21 (33) | 14 (61) |

| 5 to 10 | 23 (25) | 17 (27) | 5 (22) |

| >10 | 12 (13) | 10 (16) | 0 (0) |

| total responses | 91 | 63 | 23 |

Data reported as n (%) of actual responses.

Data for programs listed as military or other not shown.

Odds ratio 3.2 (95% CI 1.03 to 9.93) comparing private versus academic programs. All other statistical comparisons nonsignificant.

Eighty-two percent of surgical programs reported training residents in PDC placement. As shown in Table 3, the highest percentage of residents (38%) place 2 to 5 PD catheters, with only 13% of residents placing >10 PD catheters during training and only at academic centers. Open mini-laparotomy (38%) was the most frequent technique, followed by laparoscopy (30%), peritoneoscope-assisted (11%), unknown (11%), and blind insertion (5%) (data not shown).

Fifty percent of program directors felt that surgeons with 2 to ≤5 years in practice were most likely to place PDCs (data not shown). Several indicated that existing practice patterns were the largest determinant of a surgeon's likelihood to place PDCs (data not shown).

Table 4lists surgery program directors' attitudes. Forty-eight percent felt training in PDC placement was important or very important. Most (61%) believed residency training affected PDC outcomes after trainees entered practice. Similarly, 61% felt residency training increased the likelihood that surgeons would place PDCs in practice. Sixty-two percent of program directors felt their programs could provide more PDC training. This did not differ significantly between academic (65%) and private programs (59%).

Table 4.

Attitudes of surgery program directors toward PDC training

| Question | Alla (n = 93) | Academic (n = 64) | Private (n = 24) |

|---|---|---|---|

| How would you rank the importance of training surgical residents in PDC placement? | |||

| very important | 3 (3) | 2 (3) | 1 (4) |

| important | 41 (45) | 28 (44) | 10 (42) |

| neutral | 31 (34) | 24 (38) | 6 (25) |

| not important | 14 (15) | 8 (13) | 5 (21) |

| completely irrelevant | 3 (3) | 1 (2) | 2 (8) |

| total responses | 92 | 63 | 24 |

| Do you believe that residency training in PDC placement affects PDC outcomes after trainees enter practice? | |||

| strongly agree | 11 (12) | 7 (11) | 4 (17) |

| agree | 46 (49) | 36 (56) | 9 (38) |

| neutral | 29 (31) | 17 (27) | 8 (33) |

| disagree | 6 (7) | 4 (6) | 2 (8) |

| strongly disagree | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) |

| total responses | 93 | 64 | 24 |

| Do you feel that placing PDCs in residency increases the likelihood that surgeons will place PDCs after they enter practice? | |||

| strongly agree | 15 (16) | 10 (16) | 4 (17) |

| agree | 42 (45) | 30 (47) | 11 (46) |

| neutral | 28 (30) | 18 (28) | 7 (29) |

| disagree | 8 (9) | 6 (9) | 2 (8) |

| strongly disagree | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| total responses | 93 | 64 | 24 |

| Do you feel your program could provide more training in surgical PDC placement if asked? | |||

| yes | 56 (62) | 41 (65) | 13 (59) |

| no | 34 (38) | 22 (35) | 9 (41) |

| total responses | 90 | 63 | 22 |

Data reported as n (%) of actual responses.

Data for programs listed as military or other not shown individually.

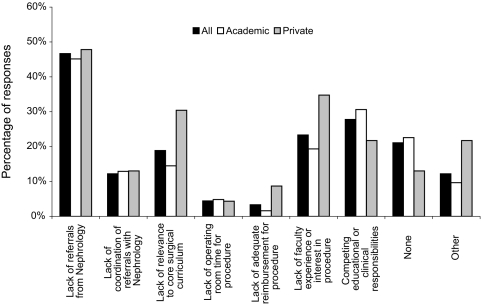

There were no statistical differences between academic and private programs for questions 14 and 15. Figure 1 displays barriers limiting PDC training. Academic (46%) and private (48%) programs cited lack of referrals from nephrology as a barrier to PDC training. Competing educational or clinical responsibilities were identified by 27% as a barrier, followed by lack of faculty experience or interest (23%), lack of relevance to core surgical curriculum (19%), coordination of referrals with nephrology (12%), lack of operating room time (4%), and inadequate reimbursement (3%). There was a nonsignificant trend for private versus academic programs to cite lack of relevance, insufficient interest, or inadequate reimbursement. Appendix 1 lists other factors, including negative attitudes toward PD and low PD use by nephrologists.

Figure 1.

Reported barriers limiting surgical training in PDC placement.

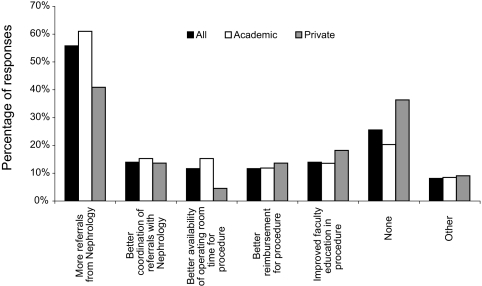

Most programs (56%) identified more referrals as a factor that would improve resident PDC training (Figure 2). No other variable was cited as often, including reimbursement (11%), availability of operating room time (11%), coordination of referrals (14%), or improved faculty education (14%). Other responses, some illustrating misconceptions about PDCs, are listed in Appendix 1.

Figure 2.

Reported factors that would improve surgery programs' ability to train residents in PDC placement.

Discussion

Although many factors contribute to the low PD prevalence in the United States, the problem of inadequate training of surgeons in PDCs has not been investigated (1,2,10,16,25,26). This study is the first attempt to evaluate surgical residency training in PDC placement. Timely PDC placement and minimization of complications are necessary to encourage use of PD (5–9,17,18,27,28). Inadequate residency training, resulting in a shortage of surgeons skilled or interested in placing PDCs, may be an underrecognized contributor to PD underutilization and why PDC complications remain a leading cause of technique failure.

In HD, surgeon expertise, willingness, and availability to perform access procedures are viewed as essential (11–15). The Fistula First Initiative, a national effort to improve HD access and outcomes (11–15), embodies this belief. In the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS), the rate of primary fistula failure was substantially lower for surgeons who performed a higher number of fistula procedures during residency (15). Moreover, the likelihood of surgeons placing a fistula was strongly related to case load and degree of emphasis on vascular access during residency (15). In contrast, the importance of surgical training in PD access and how this might influence outcomes and practice has not been studied.

Intuitively, surgeons with adequate training should feel more comfortable placing PDCs and experience fewer complications. However, as shown in Appendix 1, PDC placement may be relegated to the least-experienced trainees with no provision to maintain this skill later in residency. Furthermore, the attitude among some surgeons that PDC placement is an entirely straightforward procedure not requiring much technical skill or special attention is at odds with expert recommendations (5,6,18,28). Better PDC education must be provided to surgeons to correct these misconceptions (5,6,27).

Repetition of procedures during residency is needed for surgical proficiency (24,29). Although no studies have defined the number of PDC insertions needed by surgeons to attain competence, surgical residents may require 20 to 40 patients before reaching an acceptable level of skill in many abdominal surgeries (5,29). We found that most residents placed 2 to ≤5 PDCs during training. This represents a major obstacle to adequate education. Given that 77% of U.S. PD programs start 10 or fewer patients yearly, it is highly improbable that surgery programs can provide enough patients for all residents to be adequately trained in PDCs (5,20). Low PD utilization seems to be the major factor driving inadequate PDC training, a sentiment shared by most program directors.

Approximately half of U.S. programs rely on one specific surgeon to place most PDCs. Given the role of a single designated PDC surgeon in supporting many PD programs, the loss of this one individual could be disastrous if no other similarly skilled or interested surgeon is available. It seems logical that if we do not train more surgeons to place PDCs, fewer will be available to ensure the growth and stability of PD programs. However, training all surgeons in PDCs would be impractical and inefficient given low case volumes and the fact that many surgeons will not be interested in PDCs, regardless of the opportunity. There should be a focus on PDC training only when there is an interest and ability to do so. Ideally, each center should designate two surgeons to perform and teach PDC placement. This would ensure adequate surgical support in case one surgeon is unavailable or leaves. Concentrating efforts on a designated few would help compensate for low referrals and would provide enough patients for these surgeons to maintain expertise and teach PDC placement to trainees.

To accomplish this, we first must address the barriers identified in this study. Attempts to improve training will fail if nephrologists do not refer more patients to PD. Nephrologists must take the initiative to educate surgeons about the negative clinical and economic effect of PDC complications, including the need for HD catheters and hospitalization. A standardized, high-quality PDC training curriculum must be established and made available to interested residents (6). Trainees in surgical specialties with ties to nephrology (e.g., vascular or transplant surgery) should also be encouraged to participate. This curriculum would be accompanied by regular, multidisciplinary audits of PDC outcomes by nephrologists and surgeons together to ensure performance and quality of care (6). If surgeons have better insight into the needs of PD patients and receive regular feedback about their results, there will be impetus for improvement. The current situation in the United States leaves far too much of this to chance.

Other factors in addition to residency training may influence a surgeon's willingness to place PDCs. Because PDCs will at best comprise only a small part of surgical practice, it may be viewed as a poorly reimbursed, time-consuming activity, particularly by private practice surgeons. The observation that only 25% of private centers participated versus nearly 50% of academic centers may support this notion. Thus, arguments for changing payment schemes to create financial incentives for surgeons to place PDCs make sense (5). Surgeons in practice, much like nephrologists, could benefit from sponsored activities such as Peritoneal Dialysis University (PDU) to compensate for lack of PD knowledge. An inaugural surgeon PDU will take place in November 2010 and could represent an important first step in establishing a national forum for surgical PDC training (personal communication, Dr. John Crabtree, March 2010).

What about nephrologists assuming more responsibility for PDC placement (22,27)? Centers using interventional nephrologists to place PDCs have reported excellent outcomes and improved PD utilization, particularly in areas where surgical expertise is unavailable or unsatisfactory (30–33). PDC placement by interventional nephrologists can be accomplished with fewer delays, which may encourage PD utilization by reducing wait times (27,30–33). The American Society of Diagnostic and Interventional Nephrology (ASDIN) has established criteria for certification in PDC insertion to ensure minimum competency for nephrologists (34).

However, relying on the recent generation of nephrologists to place PDCs may have serious limitations. Only 14% of U.S. nephrology fellowship programs provide instruction in PDC placement, and only 9% of nephrology programs teach interventional nephrology using standards suggested by the ASDIN (5,21,22). Although PDC placement by nephrologists can be very successful, the fact remains that only 20.3% of recent U.S. nephrology graduates felt training in PDC placement was important to their career or practice, and only 3.8% of those trained felt competent enough to place PDCs (35).

The ASDIN requires six supervised and ten unsupervised PDC insertions to attain certification (34). Nephrology trainees in one study required at least 23 PDC insertions to reach acceptable skill (36). It remains a challenge then for nephrologists and surgeons to obtain sufficient case volume for PDC training. One consideration when referrals are limited is that technical skills derived from performing other procedures may help surgeons become proficient in PDCs faster than nephrologists (5). Another argument favoring surgical PDC placement is that even with training nephrologists may not attain skill or outcomes comparable to surgeons, particularly if laparoscopic techniques are used (5,18,22).

The strengths and limitations of our study design merit discussion. Because PDC placement is not considered part of the surgical curriculum, performance of this procedure by residents is not routinely reported to ACGME (personal communication, ACGME, August 2008). Furthermore, the lack of specificity of the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 49421 for PDC placement (which includes all types of peritoneal catheters and drains) precluded accurate analysis of the ACGME database (personal communication, ACGME, August 2008). Thus, in the absence of existing data, we felt that surveying program directors would provide the best available account of resident PDC training. Because program directors are responsible for implementing and modifying curriculum, we felt their responses would reflect a program's involvement and willingness to train residents in PDCs. We did not specifically target surgeons who placed PDCs because they likely do so based on their skill or interest and would likely be biased.

Substantial effort was made to encourage participation. Each program director received personalized e-mails and was phoned directly. Both of these strategies have been shown to increase responses, and our rate of 38% is similar to other survey studies (25,27,35,37). Nearly 50% of U.S. academic programs participated, and the sizes of responding versus nonresponding programs appeared similar. Still, nonresponse bias remains a concern. It is likely that responding program directors had more interest in PDC placement. Centers with little experience with PDC placement were probably less inclined to respond. Responses were not verified, so recall bias could be present. Therefore, our results likely overestimate the extent of and support for surgical PDC training. Nonetheless, there seems to be support at a sizeable number (n = 56) of surgery programs for more PDC training, highlighting existing opportunities for collaboration with surgeons.

In conclusion, although many surgery programs train residents in PDC placement, this training appears inadequate and may affect a surgeon's willingness and ability to perform this procedure. Although low PD use by nephrologists is the primary problem, we postulate that inadequate surgical PDC training leads to more frequent complications, further discouraging PD referrals. Fewer referrals prevent surgeons from ever gaining enough experience in PDCs, perpetuating a vicious cycle of mediocre outcomes, dissatisfaction with PD, and low PD utilization.

Nephrologists should develop coordinated efforts with surgeons and institutions to prioritize and support PDC training for designated surgeons and trainees who want to learn this procedure. Related quality improvement measures are also needed to monitor performance, provide feedback, and encourage surgeon accountability for PDC outcomes (6). In areas without surgical interest, interventional nephrologists need to assume responsibility for placing PDCs. Given federal mandates encouraging the use of PD, the availability of PDC expertise in future years becomes even more pertinent (38). This problem deserves more attention and should be considered when discussing strategies to address the trend of declining PD use in the United States.

Disclosures

Dr. Wong has served as a consultant for Baxter Healthcare.

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible in part by grant no. 1 UL1 RR024160-01 from the National Center for Research Resources, a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. An abstract of this study was presented in August 2009 at the North American Chapter Meeting of the International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis in Vancouver, Canada. We appreciate the assistance of the participating program directors and Rebecca Miller, Vice President of Applications and Data Analysis, ACGME, in August 2008.

Appendix 1. Other responses to survey questions

Question 14: What barriers or potential barriers limit training in PDC placement in your surgical residency program? (n = 12)

|

Question 15: What factors would help improve your surgery program's ability to train residents in PDC placement? (n = 7)

|

Reported and listed parenthetically from actual responses with occasional edits.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Mehrotra R, Kermah D, Fried L, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Khawar O, Norris K, Nissenson A: Chronic peritoneal dialysis in the United States: Declining utilization despite improving outcomes. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 2781–2788, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khawar O, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Lo WK, Johnson D, Mehrotra R: Is the declining use of long-term peritoneal dialysis justified by outcome data? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2: 1317–1328, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neil N, Guest S, Wong L, Inglese G, Bhattacharyya SK, Gehr T, Walker DR, Golper T: The financial implications for Medicare of greater use of peritoneal dialysis. Clin Ther 31: 880–888, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. Renal Data System: 2009 USRDS Annual Data Report. Bethesda, MD, U.S. Department of Public Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crabtree JH: Who should place peritoneal dialysis catheters? Perit Dial Int 30: 142–150, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Renal Association: U.K. guidelines—Peritoneal access: Available at: http://www.renal.org/pages/pages/guidelines/current/peritoneal-access.php Accessed March 13, 2010

- 7.Flanigan M, Gokal R: Peritoneal catheters and exit-site practices toward optimum peritoneal access: A review of current developments. Perit Dial Int 25: 132–139, 2005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gokal R, Alexander S, Ash S, Chen TW, Danielson A, Holmes C, Joffe P, Moncrief J, Nichols K, Piraino B, Prowant B, Slingeneyer A, Stegmayr B, Twardowski Z, Vas S: Peritoneal catheters and exit-site practices toward optimum peritoneal access: 1998 update. (Official report from the International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis). Perit Dial Int 18: 11–33, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nichols WK: Observations on chronic peritoneal dialysis catheter placement. Perit Dial Int 19: 309–310, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mehrotra R: Peritoneal dialysis penetration in the United States: March towards the fringes? Perit Dial Int 26: 419–422, 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lacson E, Jr, Lazarus JM, Himmelfarb J, Ikizler TA, Hakim RM: Balancing Fistula First with Catheters Last. Am J Kidney Dis 50: 379–395, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agarwal AK, Asif A.Interventional nephrology. NephSAP 8338,339, 343–345, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fistula First breakthrough initiative change concepts. Available online at http://www.fistulafirst.org Accessed October 31, 2009

- 14.Lok CE: Fistula First Initiative: Advantages and pitfalls. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2: 1043–1053, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saran R, Elder SJ, Goodkin DA, Akiba T, Ethier J, Rayner HC, Saito A, Young EW, Gillespie BW, Merion RM, Pisoni RL: Enhanced training in vascular access creation predicts arteriovenous fistula placement and patency in hemodialysis patients: Results from the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study. Ann Surg 247: 885–891, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finkelstein FO: Structural requirements for a successful chronic peritoneal dialysis program. Kidney Int Suppl 103: S118–S121, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blake PG: The critical importance of good peritoneal catheter placement. Perit Dial Int 28: 111–112, 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crabtree JH: Selected best practices in peritoneal dialysis access. Kidney Int Suppl 103: S27–S37, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo A, Mujais S: Patient and technique survival on peritoneal dialysis in the United States: Evaluation in large incident cohorts. Kidney Int Suppl 64: S3–S12, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mujais S, Story K: Peritoneal dialysis in the U.S.: Evaluation of outcomes in contemporary cohorts. Kidney Int Suppl 103: S21–S27, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berns JS, O'Neill WC: Performance of procedures by nephrologists and nephrology fellows at U.S. nephrology training programs. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 941–947, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kohan DE: Procedures in nephrology fellowships: time for change. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 931–932, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Negoi D, Prowant BF, Twardowski ZJ: Current trends in the use of peritoneal dialysis catheters. Adv Perit Dial 22: 147–152, 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bell RH, Jr, Biester TW, Tabuenca A, Rhodes RS, Cofer JB, Britt LD, Lewis FR, Jr: Operative experience of residents in U.S. general surgery programs: A gap between expectations and experience. Ann Surg 249: 719–724, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mehrotra R, Blake P, Berman N, Nolph KD: An analysis of dialysis training in the United States and Canada. Am J Kidney Dis 40: 152–160, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pulliam J, Hakim R, Lazarus JM: Peritoneal dialysis in large dialysis chains. Perit Dial Int 26: 435–437, 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilkie M, Wild J: Peritoneal Dialysis Access - Results from a UK Survey. Perit Dial Int 29: 355–357, 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Danielsson A: The controversy of placement of peritoneal dialysis catheters. Perit Dial Int 27: 153–154, 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Rij AM, McDonald JR, Pettigrew R, Petterill M, Reddy C, Wright J: CUSUM as an aid to early assessment of the surgical trainee. Br J Surg. 82: 1500–1503, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zaman F, Pervez A, Atray NK, Murphy S, Work J, Abreo KD: Fluoroscopy-assisted placement of peritoneal dialysis catheters by nephrologists. Semin Dial 18: 247–251, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gadallah MF, Ramdeen G, Torres-Rivera C, Ibrahim ME, Myrick S, Andrews G, Quin A, Fang C, Crossman A: Changing the trend: A prospective study on factors contributing to the growth rate of peritoneal dialysis programs. Adv Perit Dial 17: 122–126, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Asif A, Pflederer TA, Vieira CF, Diego J, Roth D, Agarwal A: Does catheter insertion by nephrologists improve peritoneal dialysis utilization? A multicenter analysis. Semin Dial 18: 157–160, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goh BL, Ganeshadeva YM, Chew SE, Dalimi MS: Does peritoneal dialysis catheter insertion by interventional nephrologists enhance peritoneal dialysis penetration? Semin Dial 21: 561–566, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.The American Society of Diagnostic and Interventional Nephrology Requirements for Certification in Interventional Nephrology - Placement of Permanent Peritoneal Dialysis Catheters: Available online at http://www.asdin.org> Accessed March 13, 2010

- 35.Berns JS: A survey-based evaluation of self-perceived competency after nephrology fellowship training. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 490–496, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goh BL, Ganeshadeva Yudisthra M, Lim TO: Establishing learning curve for Tenckhoff catheter insertion by interventional nephrologist using CUSUM analysis: How many procedures and in which situation? Semin Dial 22: 199–203, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.VanGeest JB, Johnson TP, Welch VL: Methodologies for improving response rates in surveys of physicians: A systematic review. Eval Health Prof 30: 303–321, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Department of Health and Human Services: Medicare and Medicaid programs: Conditions for coverage for end-stage renal disease facilities; Final Rule. Fed Regist 73: 20471, 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]