Abstract

Background and objectives: Little is known about the risks of catheter-related infections in patients undergoing intermittent hemodialysis (IHD) as compared with continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) techniques. We compared the two modalities among critically ill adults requiring acute renal replacement therapy (RRT).

Design, setting, participants, & measurements: We used the multicenter Cathedia study cohort of 736 critically ill adults requiring RRT. Cox marginal structural models were used to compare time to catheter-tip colonization at removal (intent-to-treat, primary endpoint) among patients who started IHD (n = 470) versus CRRT (n = 266). On-treatment analysis was also conducted to take into account changes in prescription of RRT modality.

Results: Hazard rate of catheter-tip colonization did not increase within the first 10 days of catheter use. Predictors of catheter-tip colonization were higher lactate levels and hypertension, while systemic antibiotics, antiseptics-impregnated catheters, and mechanical ventilation were associated with decreased risk. The incidence of catheter-tip colonization per 1000 catheter-days was 42.7 in the IHD group and 27.7 in the CRRT group (P < 0.01). This association was no longer significant after correction for channeling bias (weighted HR, 0.96; 95% CI: 0.77 to 1.20, P = 0.73). On-treatment analysis revealed an increased risk of primary endpoint during CRRT exposure as compared with IHD exposure (weighted HR, 0.71; 95% CI: 0.56 to 0.92, P < 0.009).

Conclusions: Our results do not support the use of CRRT when IHD could be an alternative to reduce the risk of catheter-related infection.

The predominant cause of nosocomial bloodstream infection in intensive care units is catheter-related bloodstream infection (1). Critically ill patients requiring renal replacement therapy (RRT) are at greater risk for infection (2), and the risk of nosocomial bloodstream infection sharply increases after initiation of RRT (3). However, only a fraction (around 16%) of the nosocomial bloodstream infection in such patients is attributed to the vascular access (2). Data on incidence and risk factors for catheter-related infection are scarce in this population, in comparison with chronic renal failure requiring RRT or central venous catheterization.

Intermittent hemodialysis (IHD) and continuous renal replacement therapies (CRRT) are the main RRT modalities used in this acute setting. To date, no difference between CRRT and IHD with respect to mortality and renal recovery has been demonstrated (4). Consequently, RRT choice could, in part, be influenced by differences in infectious risk of IHD versus CRRT. CRRT modalities require prolonged systemic anticoagulation and may limit the number of catheter manipulations required before and after each IHD session and therefore influence the risk of vascular access infection (5). On the other hand, compared with IHD, CRRT could increase the risk of hypothermia [5% versus 17%, respectively, in the study by Vinsonneau et al. (6)] and therefore the risk of infection.

We previously investigated the effect of the anatomic site on the risk of dialysis catheter-tip colonization among critically ill adults requiring vascular access for RRT (7). Using the same data, the present study aimed to describe the epidemiology of catheter-related infection and compare the catheter-tip colonization at removal in patients with RRT by IHD versus CRRT.

Materials and Methods

Study Design, Setting, and Population

We designed a retrospective cohort study of critically ill adults who were expected to require renal support with RRT and were included in the Cathedia study between May 2004 and May 2007. Only adults who were undergoing their first temporary noncuffed venous catheterization for RTT were included.

Cathedia was a multicenter, randomized controlled trial involving nine university hospitals and three general hospitals. The study compared the risk of catheter infection (7) based on catheter insertion site (jugular or femoral) and mode of RRT. Randomization of the catheter insertion site was stratified by RRT mode. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Côte de Nacre University Hospital. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants or their proxies.

Mode of RRT

Neither institutional guidelines nor prespecified algorithms dictated the mode of RRT that was used in the participating centers. Consequently, the choice between IHD and CRRT was left to the discretion of each attending physician.

Catheter Care

As described previously (7), the insertion and handling of dialysis catheters were performed according to the 2002 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendations (8). However, disinfection of the catheter insertion site was done using alcoholic povidone iodine (9) rather than chlorhexidine. Antimicrobial locks were not used in the study.

Endpoints

Catheter-tip colonization.

The Brun-Buisson simplified technique of quantitative broth dilution culture was used to define catheter-tip colonization (10). Briefly, after removal of the catheter, the distal 4- to 5-cm catheter segment was aseptically sectioned and sent to the clinical microbiology laboratory in a sterile dry plastic tube. One milliliter sterile water was dripped on the catheter, and the tube was vortex mixed for 1 minute; 0.1 ml suspension was sampled with a calibrated pipette and plated over the whole surface of a 90-mm diameter 5% horse blood agar plate. Plates were incubated at 35°C to 37°C and examined daily for 2 days. The colonies of each species were enumerated, the counts were corrected for the initial one-tenth dilution, and quantitative results were reported as CFU/ml. Catheter-tip colonization was defined as cultures with at least 103 CFU/mm growth. The microbiologists were unaware of the mode of RRT.

Catheter-related bloodstream infection.

Catheter-related bloodstream infection was defined as catheter-tip colonization plus peripheral blood culture(s) yielding the same organisms with the same antimicrobial susceptibility as the catheter-tip within 48 hours of catheter removal, with no other apparent source of infection (8). Growth from two different peripheral blood cultures was required to define catheter-related bloodstream infection when potential skin contaminants were recovered.

Statistical Analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± SD, or median interquartile range (IQR) and percentage depending of the nature of the variable of interest. Differences between patients starting with IHD or CRRT were compared using χ2 or Fisher exact tests for categorical variables and two-tailed, unpaired t test or Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables, as appropriate.

The assigned mode corresponded to initial choice for RRT, regardless of the changes in prescription resulting in a change in mode of RRT (generally from CRRT to IHD) during catheterization, in accordance with the intent-to-treat principle. This strategy was complemented by an on-treatment analysis in which the mode of RRT was considered as time-varying, to take into account time on each modality.

The statistical plan had three steps: (1) investigate risk factors for time to catheter-tip colonization; (2) estimate the daily risk of colonization according to the duration of catheterization; and (3) compare the risk of colonization according to the dialysis mode.

The RRT modality and other baseline factors associated with the time to colonization were assessed by hazard ratios (HR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI), with values >1 indicating an increase probability of catheter-tip colonization. Subsequently, a multivariate Cox model was computed with a stepwise selection of variables with a P value <0.05 to remain in the model.

The daily risk of dialysis catheter-tip colonization was estimated by the hazard rate function from right-censored data using kernel-based methods (11).

Since the study was not randomized, the patients starting with CRRT could not have the same risk of catheter infection as those who started with IHD. Therefore, potential indication or “channeling” biases were adjusted for by developing a propensity score for starting with one versus another mode of RRT. A stepwise logistic regression analysis was performed to select baseline variables, including first-order interactions, that were associated with the use of IHD. Variables were entered into the model at a P value cut-off of 0.50. Consequently, clinically relevant but NS factors were also included to derive a full nonparsimonious model. Using these selected variables, a propensity score was estimated by maximum likelihood logistic regression analysis. Calibration of the final logistic model was assessed using the Hosmer-Lemeshow statistic.

We performed two different methods described in details by Robin et al. (12) and Austin et al. (13) to correct for channeling bias. First, we used the concept of marginal structural Cox models, also known as inverse probability of weighted treatment. Second, we performed a one-to-one greedy five-to-one digit technique to match one CRRT subject by one IHD subject, based on their propensity score. In this matched sample, baseline characteristics were compared by the standardized difference, as recommended (14). The probability of endpoint was modeled in a Cox model with robust covariance matrix estimation to account for the matched design.

The proportionality assumption in all Cox models was tested and met. HR >1 indicated an increase probability of catheter-tip colonization in the IHD modality as compared with the CRRT modality. A P value <0.05 was considered significant, and all P values were two-tailed without adjustment for multiple comparisons. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS statistical software, version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) and R statistical software, version 2.10.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Baseline Characteristics and Epidemiology

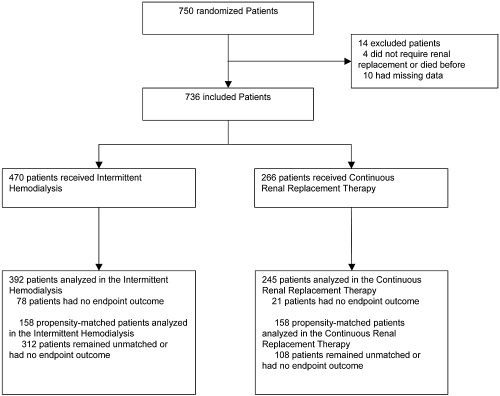

Seven hundred thirty-six consecutive patients fulfilled inclusion criteria and were enrolled prospectively into the Cathedia study (Figure 1). Among them, 266 (36.1%) patients started with CRRT and 470 (63.9%) started with IHD. A switch from CRRT to IHD occurred in 95 (12.9%) patients, while a switch from IHD to CRRT occurred in 4 (0.5%) patients. Baseline characteristics of the cohort are shown in Table 1, and most of these variables were significantly different between groups.

Figure 1.

Patients disposition.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics according to the mode of renal replacement therapy before and after propensity score matching

| Overall |

P | Propensity-Matched |

SDi | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IHD (n = 470) | CRRT (n = 266) | IHD (n = 158) | CRRT (n = 158) | |||

| Patients, n (%) | ||||||

| Age (years; mean [SD]) | 65.7 (15.0) | 63.7 (14.5) | 0.08 | 65.2 (14.3) | 65.6 (13.6) | 2.9 |

| Male | 314 (66.8) | 180 (67.7) | 0.82 | 99 (62.7) | 116 (73.4) | 23.2 |

| Body mass index (mean [SD]) | 26.5 (5.2) | 26.9 (5.5) | 0.37 | 27.1 (5.7) | 26.9 (5.3) | 3.6 |

| SAPS II score (SD) | 56.3 (19.6) | 65.6 (22.3) | <0.0001 | 59.0 (20.7) | 61.7 (22.0) | 12.6 |

| Number of organ failure (mean [SD]) | 2.2 (1.2) | 2.9 (1.1) | <0.0001 | 2.5 (1.1) | 2.5 (1.1) | 0 |

| McCabe score (mean [SD]) | 1.4 (0.7) | 1.6 (0.7) | <0.003 | 1.6 (0.8) | 1.5 (0.7) | 13.3 |

| Ventilated (mean [SD]) | 289 (61.5) | 237 (89.1) | <0.0001 | 128 (81.0) | 132 (83.5) | 6.6 |

| Coma Glasgow scale (mean [SD]) | 11.4 (4.9) | 10.1 (5.3) | <0.002 | 11.2 (4.9) | 11.0 (5.0) | 4.0 |

| Cardiac rhythm (mean [SD]) | 98 (38) | 108 (41) | <0.001 | 109.0 (38.3) | 105.3 (40.5) | 9.4 |

| Arterial pressure (mmHg; mean [SD]) | 70.4 (28.2) | 59.1 (24.9) | <0.0001 | 64.7 (26.0) | 63.1 (27.2) | 6.0 |

| Days from admission to inclusion (mean [SD]) | 2.4 (5.8) | 3.1 (7.7) | 0.24 | 3.8 (5.7) | 3.7 (9.5) | 1.3 |

| Body temperature (°C; mean [SD]) | 36.8 (1.9) | 36.9 (2.5) | 0.43 | 36.9 (2.1) | 37.0 (2.4) | 4.4 |

| White blood cell count (cells/μl; mean [SD]) | 13,889 (9525) | 14,879 (10,037) | 0.2 | 14,479 (10,201) | 13,999 (8158) | 5.2 |

| Platelets count (cells/ml; mean [SD]) | 191,190 (127,190) | 161,410 (134,740) | <0.004 | 163,030 (117,520) | 173,030 (114,990) | 8.6 |

| Prothrombin rate (%; mean [SD]) | 58.3 (22.7) | 47.4 (23.5) | <0.0001 | 53.7 (22.4) | 53.8 (23.8) | 0.4 |

| pH (mean [SD]) | 7.274 (0.154) | 7.227 (0.175) | <0.0005 | 7.267 (0.167) | 7.262 (0.160) | 3.1 |

| Kaliemia (mmol/L; mean [SD]) | 4.7 (1.4) | 4.5 (1.2) | 0.07 | 4.54 (1.28) | 4.50 (1.18) | 4.1 |

| Lactate levels (mean [SD]) | 4.3 (4.0) | 6.2 (5.1) | <0.0001 | 4.6 (3.9) | 4.7 (4.0) | 2.5 |

| Bicarbonates (mean [SD]) | 17.2 (6.2) | 18.0 (7.1) | 0.16 | 18.6 (7.7) | 18.5 (6.9) | 1.4 |

| Urea (mmol/L; mean [SD]) | 24.6 (15.6) | 17.7 (10.6) | <0.0001 | 19.8 (13.0) | 19.6 (11.8) | 1.6 |

| Serum creatinine (μmol/L; mean [SD]) | 366.9 (304.7) | 252.6 (144.4) | <0.0001 | 256.8 (154.8) | 267.9 (158.0) | 7.1 |

| Urine output (ml/d; mean [SD]) | 991 (1009) | 826 (924) | <0.03 | 962 (768) | 922 (942) | 4.7 |

| Hematocrit (%; mean [SD]) | 30.8 (8.3) | 29.9 (8.2) | 0.15 | 31.0 (8.3) | 31.2 (8.0) | 2.5 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl: mean [SD]) | 10.36 (2.90) | 10.13 (3.29) | 0.37 | 10.36 (2.64) | 10.33 (2.58) | 1.5 |

| Received systemic antibiotics (n [%]) | 247 (52.6) | 205 (77.1) | <0.0001 | 116 (73.4) | 115 (72.8) | 4.1 |

| Vasopressive support | 274 (58.3) | 216 (81.2) | <0.0001 | 106 (67.1) | 109 (69.0) | 4.1 |

| Immunosuppression | 86 (18.3) | 41 (15.4) | 0.32 | 31 (19.6) | 21 (13.3) | 17.1 |

| Diabetes | 131 (27.9) | 61 (22.9) | 0.15 | 45 (28.5) | 41 (26.0) | 5.7 |

| Hypertension | 238 (50.6) | 120 (45.1) | 0.15 | 81 (51.3) | 80 (50.6) | 1.3 |

| Catheter (n [%]) | ||||||

| Antiseptic-impregnated catheter | 150 (31.9) | 11 (4.1) | <0.0001 | 10 (6.3) | 10 (6.3) | 0 |

| catheter site | ||||||

| Femoral (versus jugular) | 232 (49.4) | 138 (51.9) | 0.52 | 74 (46.8) | 85 (53.8) | 14.0 |

| Days of insertion | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 6.3 (6.2) | 6.6 (6.0) | 0.53 | 8.6 (7.9) | 7.2 (6.0) | 20.0 |

| Median (IQR) | 5 (2 to 8) | 5 (2 to 9) | 0.31 | 6 (3 to 11) | 6 (3 to 10) | NA |

| Conditional probability to receive IHD | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.76 (0.23) | 0.42 (0.23) | <0.0001 | 0.54 (0.19) | 0.53 (0.20) | NA |

| Median (IQR) | 0.83 (0.60 to 0.95) | 0.40 (0.24 to 0.59) | <0.0001 | 0.52 (0.40 to 0.65) | 0.52 (0.40 to 0.66) | NA |

Sdi, standardized difference; NA, not applicable.

Among included patients, catheter-tip culture at removal was available for 392 (83.4%) in the IHD group and 245 (92.1%) in the CRRT group. The overall cumulative incidence of catheter-tip colonization was 162/637 (25.4%) corresponding to an incidence of 38.9 per 1000 catheter-days (exact 95% CI: 27.6 to 53.2). The most frequently isolated organism was Staphyloccocus epidermidis (71/162 [43.8%]). Details of the microbiologic findings of catheter-tip culture are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Microbiological findings

| Overall (n = 637) | IHD (n = 392) | CRRT (n = 245) | Pa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catheter-tip colonization | ||||

| n (%) | 162 (25.4) | 114 (29.1) | 48 (19.6) | <0.009b |

| Incidence per 1000 catheter-days | 38.9 | 42.7 | 27.7 | <0.02c |

| Microorganism characteristics (n) | ||||

| Gram positive | 92 | 73 | 19 | <0.005 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 71 | 57 | 14 | <0.02 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 10 | 6 | 4 | 0.49 |

| Enterococcus spp. | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0.19 |

| Other | 5 | 4 | 1 | >0.99 |

| Gram negative | 45 | 29 | 16 | 0.41 |

| Escherichia coli | 11 | 8 | 3 | >0.99 |

| Proteusspp. | 5 | 3 | 2 | 0.64 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 13 | 7 | 6 | 0.21 |

| Enterobacter spp. | 8 | 5 | 3 | 0.70 |

| Other | 8 | 6 | 2 | >0.99 |

| Fungi | 16 | 5 | 11 | <0.0008 |

| Polymicrobial | 9 | 7 | 2 | >0.99 |

| CRBSI | ||||

| n (%) | 8 (1.3) | 6 (1.5) | 2 (0.8) | >0.99b |

| CRBSI per 1000 catheter-days | 1.9 | 2.6 | 1.2 | 0.43c |

| Microorganism characteristics (n) | ||||

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 4 | 3 | 1 | >0.99 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 4 | 3 | 1 | >0.99 |

CRBSI, catheter-related bloodstream infection.

Comparing IHD versus CRRT in case of catheter-tip colonization, otherwise specified.

Comparing IHD versus CRRT by Fisher exact test.

Comparing IHD versus CRRT by Poisson regression.

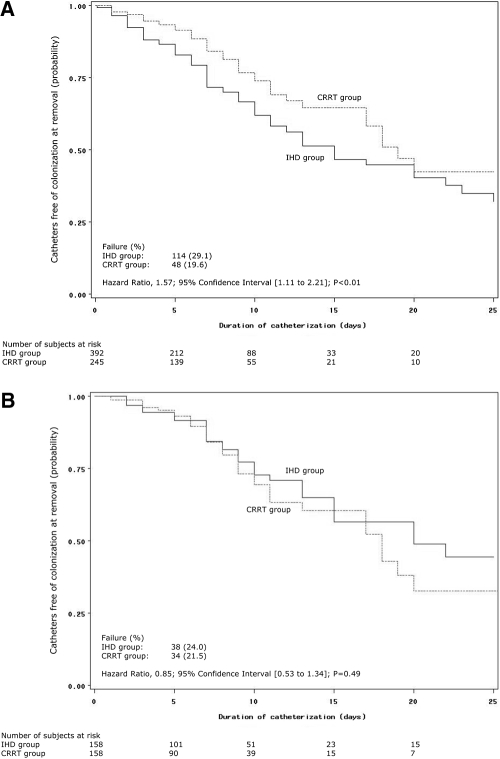

The risk of catheter-tip colonization at removal was significantly higher (Figure 2A) in the group starting with IHD (42.7 per 1000 catheter-days versus 27.7 in the group starting with CRRT; HR, 1.6; 95% CI: 1.1 to 2.2, P < 0.01). Other baseline characteristics associated with time to catheter-tip colonization were receipt of antimicrobials at the time of insertion, the use of antiseptics-impregnated catheters, mechanical ventilation, higher lactate levels, higher uremia levels, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension. In the Cox model, independent risk factors for RRT catheter-tip colonization were receipt of antimicrobials at the time of catheter insertion (HR, 0.54; 95% CI: 0.38 to 0.76, P < 0.0004), the use of antiseptics-impregnated catheters (HR, 0.50; 95% CI: 0.34 to 0.71, P < 0.0003), mechanical ventilation (HR, 0.51; 95% CI: 0.35 to 0.74, P < 0.0003), higher lactate levels (HR, 1.07; 95% CI: 1.02 to 1.11, P < 0.002), and hypertension (HR, 1.6; 95% CI: 1.1 to 2.2, P < 0.006).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves of time to catheter-tip colonization at removal in the overall cohort (A) and after propensity-matching (B) by initial renal replacement mode.

In the on-treatment analysis (Table 3), the risk of catheter-tip colonization at removal was nonsignificantly higher during exposure to IHD compared with CRRT (HR, 1.44; 95% CI: 0.94 to 2.20, P = 0.10).

Table 3.

Comparisons of catheter-tip colonization risk according to renal replacement therapy modalities (CRRT versus IHD)

| Intent-to-Treata |

On-Treatmentb |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRc | 95% CI | P | HRc | 95% CI | P | |

| Unadjusted | 1.57 | (1.11 to 2.21) | <0.01 | 1.44 | (0.94 to 2.20) | 0.10 |

| Marginal structural models | 0.96 | (0.77 to 1.20) | 0.73 | 0.71 | (0.56 to 0.92) | <0.009 |

| Propensity-score matched | 0.85 | (0.53 to 1.34) | 0.49 | 0.84 | (0.47 to 1.50) | 0.56 |

Groups were defined by initial modality of renal replacement therapy, regardless of change in modality prescription.

Groups were varying according to change in modality prescription.

HR > 1 indicates an increase risk in the IHD modality as compared CRRT to modality.

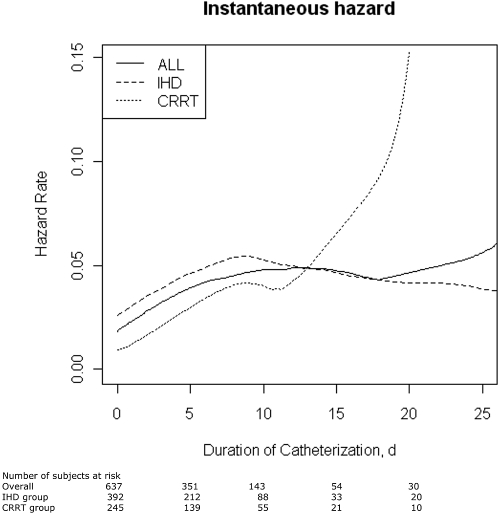

The mean duration of catheterization was longer for colonized catheters (7.9 days versus 6.3 days for the remaining catheters, P < 0.007). As shown in Figure 3, the overall instantaneous hazard of RRT catheter-tip colonization did not increase according to the range of catheter duration. When this analysis was stratified by initial mode of RRT (Figure 3), the instantaneous hazard of RRT catheter-tip colonization sharply increase after 10 days among patients starting with CRRT and was constant among patients starting with IHD.

Figure 3.

Daily hazard rate of catheter-tip colonization at removal in the overall cohort and stratified by initial renal replacement mode.

The overall cumulative incidence of catheter-related bloodstream infection was 8 to 637 (1.3%) corresponding to an incidence of 1.9 per 1000 catheter-days (exact 95% CI: 0.2 to 7.1) and did not significantly differed by mode of RRT (Table 2).

Propensity Analysis

The 29 variables associated with the use of CRRT at P < 0.5 (Table 1) and five first order interactions were used to compute the propensity score. The final logistic model had a concordance index (c-index) of 0.84 and a nonsignificant Hoshmer-Lemeshow test (P = 0.52), indicating a strong ability to differentiate between patients receiving or not receiving IHD and good calibration, respectively. As expected, variables associated with the use of IHD in the overall cohort were well-balanced after matching on the propensity score, as shown in Table 1. The results of the risk comparison between modalities with propensity-score adjustments are reported in Table 3 and Figure 2B. In the propensity-matched subgroup (n = 316), catheter-related bloodstream infection occurred in three patients in the IHD group and two patients in the CRRT group.

Discussion

In this large cohort study, we found an overall incidence density of colonization and bloodstream infection of 38.9 for and 1.9 per 1000 catheter-days, respectively. Hypertension, mechanical ventilation, antibiotic use at the time of insertion, antiseptic-impregnated catheters, and lactate levels were independently associated with catheter-tip colonization at removal. Duration of catheterization did not influence the daily hazard rate of catheter-tip colonization among patients starting with IHD, which argues against systematic RRT catheter replacement after a predetermined amount of time to prevent catheter-related infection in this group. In contrast, this risk increased after 10 days among patients starting CRRT. In addition, although initial use IHD versus CRRT was associated with increased risk of catheter-tip colonization, this association was highly confounded and was no longer significant after correction for channeling bias. Moreover, compared with IHD, CRRT mode was associated with an increased risk of catheter-tip colonization when baseline differences and time on each modalities were taken into account.

We found a higher incidence of colonization than for non-RRT catheters [e.g., 11.1 per 1000 catheter-days were reported in Lucet et al. (15)], but paradoxically the incidence of clinically important catheter-related bloodstream infection was proportionally low. Using the equation derived from 29 papers of non-RRT catheters (16): BSI = 0.73 + 0.17 CTC (where BSI denotes bloodstream infection and CTC denotes colonization incidences), we would have expected 7.3 catheter-related bloodstream infection per 1000 catheter-days, which lies outside our 95% CI. Consequently, acute RRT catheter-tip colonization may be less prone to lead to bloodstream infection than non-RRT catheters. This hypothesis is supported by two small single-center studies by Souweine et al. (17,18), which compared dialysis and non-RRT catheter-related infection rates. Although not statistically significant, both studies (17,18) reported higher rates of colonization but lower rates of catheter-related bloodstream infection in dialysis versus non-RRT catheters. Whether this observation is related to differences in catheter use, population characteristics, or both is unclear. The higher mortality in this population may compete with catheter-related bloodstream infection.

In agreement with previous reports (17,19), the most frequently cultured microorganism was Staphylococcus epidermidis. Predominance of fungi may be, in part explained by greater broad-spectrum, predominantly antibacterial, antibiotic use in CRRT patients than IHD, as suggested by greater antimicrobial use noted in the Table 1. Of note, differences in the microbial findings could not be explained by anatomic site differences, since the mode of RRT served as a blocking variable in the jugular versus femoral randomization process (Table 1). Also, Gram positive bacteria were responsible for all catheter-related bloodstream infection, as previously reported (17).

Hypertension was identified as an independent risk factor for colonization, as previously reported for catheter-related bloodstream infection in chronic dialysis (20) and for surgical site infection (21). Potential reasons for this finding are as follows: (1) hypertension could be associated with comorbidities, such as diabetes mellitus or atherosclerosis, which also increased the risk of infection (22); (2) previous exposure to antihypertensive drugs may contribute to increase infectious risk, as suggested for community-acquired pneumonia (23); and (3) hypertension itself could be associated with rarefaction of skin capillarities (24), lower peripheral blood supply, and thus accelerate extraluminal colonization. The causative nature of the associations between systemic antibiotics (25) or antiseptic-impregnated catheter (26) and the risk of catheter infection remains speculative, since those factors were not randomized and may interfere with the catheter microbiological culture used as the primary endpoint. Mechanical ventilation, a surrogate for respiratory failure, was negatively associated with the risk of colonization. This association lacks of any physiologic rationale and should therefore be interpreted with caution. Higher lactate levels were also identified as an independent risk factor for catheter-related infectious risk. Acidosis may impair immune function by depressant effects on polymorphonuclear and lymphocyte function (27). Acidosis also has important inflammatory effects (27,28).

Systematic catheter replacement as a mean of limiting infectious risk has been a subject of controversy, including in the field of RRT catheters (29). Based on our results and the results of others (19,30), we recommend against this practice for critical patients admitted in intensive care units who still require acute vascular access for IHD. However, the CRRT group demonstrated an increased risk after 10 days. Therefore, physicians should be aware of the increased risk of catheter-related infection in this subgroup of patients receiving CRRT as initial mode who survived 10 days with the first catheter used for CRRT in place. Nevertheless, cumulative exposure increased the risk of catheter-related infection and confirms that RRT catheter, like any other intravascular device, should be removed as soon as possible when no longer indicated (8).

To our knowledge, our study is the first to compare the frequency of catheter-tip colonization in IHD and CRRT. One randomized study had compared catheter infection (6) with similar risks between modes. If their intent-to-treat data are combined with our intent-to-treat propensity-matched subgroup, the cumulative incidences of catheter-related bloodstream infection are 5 in 342 (1.4%) for IHD and 5 in 333 (1.5%) for CRRT (relative risk: 1.03, 95% CI: 0.30 to 3.52, P = 0.99) in accordance with the inverse probability weighted catheter-tip colonization HR in our study. We found discrepancies between intent-to-treat and on-treatment weighted analyses. Intent-to-treat approach can attenuate the effect of an intervention when the percentage of crossover increases between groups.

We are aware of limitations in our work. Only tips of RRT catheters were cultured on removal. Catheter lumens can be cultured using endoluminal brush either in situ or after removal in the laboratory or by culturing sections of the catheter (31). Consequently, the rate of endoluminal colonization could have been underestimated. Regarding the estimations of catheter-related bloodstream infection rates, we cannot exclude that the timing of blood cultures, performed when clinically indicated, failed to diagnose asymptomatic catheter-related bloodstream infection. Because catheter-related bloodstream infection was a rare observed event, we were not able to investigate risk factors for this outcome. The estimations of daily hazard rate for colonization are uncertain after 15 days of catheterization, because of the small number of subjects at risk. Consequently, our results are compatible with an increased risk beyond that time. Also, patients were bedbound and critically ill. Therefore, our results should not be extrapolated to different settings, such as chronic renal failure. All comparisons between IHD and CRRT should be interpreted carefully, in the absence of initial randomization. Also, on-treatment analyses were only adjusted for baseline characteristics, did not account for modifications of risk factors that may have occurred over time, and should therefore be considered as hypothesis generating.

In conclusion, we described a high incidence of catheter-tip colonization at removal supporting current efforts to limit that risk in this population, but a relatively low incidence of catheter-related bloodstream infection. The risk of catheter-related infection remained unchanged with time, except after 10 days among patients starting with CRRT. The initial mode of RRT did not influence the incidence of catheter-colonization at removal. However, exposure to CRRT compared with exposure to IHD may increase the risk of catheter-tip colonization. Therefore, our results do not support the use of CRRT when IHD could be an alternative to reduce the risk of catheter-related infection.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the dedication of the nursing and medical staff members of all the participating centers and the generosity of the study participants or family members, without whom this study could not have been completed. We also thank Nelly Chaillot for her expertise in graphic design support.

This study was funded by the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Caen and supported by an unrestricted academic grant from the French Health Ministry (Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique National 2003).

Data Monitoring Task Force: A. Gauneau (clinical research assistant, CHU de Caen); J.J. Dutheil (clinical research assistant, CHU de Caen); E. Vastel (clinical research assistant, CHU de Caen); F. Chaillot (administrator, CHU Caen).

Participating Centers and Cathedia Investigators: Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Caen, Réanimations Médicale: J.J. Parienti (principal investigator), M. Ramakers, D. du Cheyron, C. Daubin, P. Charbonneau, N. Terzi, B. Bouchet, S. Chantepie, A. Seguin, S. Chevalier, D. Guillotin, X. Valette, T. Dessieux, W. Grandin, S. Lammens, C. Buleon, V. Pottier, C. Quentin, S. Thuaudet, C. Le Hello; Réanimations Chirurgicale: A. Ouchikhe (principal investigator), D. Samba, C. Jehan, G. Viquesnel, G. Leroy, E. Frostin, C. Eustratiades, M.O. Fischer, M.R. Clergeau, F. Michaux; Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Cochin-Port-Royal, Assistance Publique- Hôpitaux de Paris, Réanimation Médicale: J.P. Mira (principal investigator), S. Marqué, M. Thirion, S. Buyse, E. Clapson, J.D. Chiche, A. Soummer, B. Planquette, C. Baklini, D. Grimaldi, T. Braun, O. Huet, S. Perbet, J. Medrano, N. Verroust, A. Mathonnet, N. Joram, E. Lopez, D. Grimaldi, G. Colin; Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Lariboisière, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, Réanimation Médicale: B. Megarbane (principal investigator), F.J. Baud, N. Deye, D. Résière, G. Guerrier, J. Theodore, S. Rettab, P. Brun, S. Karyo, S. Delerme, A. Abdelwahab, J.M. Ekhérian, I. Malissin, A. Mohebbi-Amoli; Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Clermont-Ferrand, Réanimation Médicale et Néphrologie: N. Gazui (principal investigator), B. Souweine, F. Thiollière, A. Lautrette, J. Liotier; Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Sainte Marguerite, Assistance Publique- Hôpitaux de Marseille, Réanimation Médicale: J.M. Forel (principal investigator), S. Gayet, N. Embriaco, D. Demory, J. Allardet-Servent, F. Michel; Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Garches, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, Réanimation Médicale: A. Polito (principal investigator), D. Annane, V. Maxime; Centre Hospitalier General, Argentueil, Réanimation Médicale: M. Thirion (principal investigator), E. Bourgeois, I. Rennuit, R. Hellmann, J. Beranger; Fondation Hôpital Saint-Joseph, Paris, Réanimation Médicale: B. Misset (principal investigator), V. Willems, F. Philippart, A. Tabah; Centre Hospitalier Universitaire d'Amiens, Service de Néphrologie Réanimation Médicale: B. de Cagny (principal investigator), M. Slama, N. Airapetian, J. Maizel, B. Gruson, A. Sarraj, F. Lengelle; Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Croix Rousse, Hospices Civils de Lyon: C. Guérin (principal investigator); Centre Hospitalier Général, Pau: P. Badia (principal investigator); Centre Hospitalier Général, Saint-Malo: L. Auvray (principal investigator). All centers are in France.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Mermel LA: Prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. Ann Intern Med 132: 391–402, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoste EA, Blot SI, Lameire NH, Vanholder RC, De Bacquer D, Colardyn FA: Effect of nosocomial bloodstream infection on the outcome of critically ill patients with acute renal failure treated with renal replacement therapy. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 454–462, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reynvoet E, Vandijck DM, Blot SI, Dhondt AW, De Waele JJ, Claus S, Buyle FM, Vanholder RC, Hoste EA: Epidemiology of infection in critically ill patients with acute renal failure. Crit Care Med 37: 2203–2209, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rabindranath K, Adams J, Macleod AM, Muirhead N: Intermittent versus continuous renal replacement therapy for acute renal failure in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3: CD003773, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Randolph AG, Cook DJ, Gonzales CA, Andrew M: Benefit of heparin in central venous and pulmonary artery catheters: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Chest 113: 165–171, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vinsonneau C, Camus C, Combes A, Costa de Beauregard MA, Klouche K, Boulain T, Pallot JL, Chiche JD, Taupin P, Landais P, Dhainaut JF: Hemodiafe Study Group Continuous venovenous haemodiafiltration versus intermittent haemodialysis for acute renal failure in patients with multiple-organ dysfunction syndrome: A multicentre randomised trial. Lancet 368: 379–385, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parienti JJ, Thirion M, Megarbane B, Souweine B, Ouchikhe A, Polito A, Forel JM, Marqué S, Misset B, Airapetian N, Daurel C, Mira JP, Ramakers M, du Cheyron D, Le Coutour X, Daubin C, Charbonneau P: Members of the Cathedia Study Group. Femoral vs jugular venous catheterization and risk of nosocomial events in adults requiring acute renal replacement therapy: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 299: 2413–2422, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Grady NP, Alexander M, Dellinger EP, Gerberding JL, Heard SO, Maki DG, Masur H, McCormick RD, Mermel LA, Pearson ML, Raad II, Randolph A, Weinstein RA: Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Recomm Rep 51: 1–29, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parienti JJ, du Cheyron D, Ramakers M, Malbruny B, Leclercq R, Le Coutour X, Charbonneau P: Members of the NACRE Study Group Alcoholic povidone-iodine to prevent central venous catheter colonization: A randomized unit-crossover study. Crit Care Med 32: 708–713, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brun-Buisson C, Abrouk F, Legrand P, Huet Y, Larabi S, Rapin M: Diagnosis of central venous catheter-related sepsis. Critical level of quantitative tip cultures. Arch Intern Med 147: 873–877, 1987 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muller HG, Wang JL: Hazard rate estimation under random censoring with varying kernels and bandwidths. Biometrics 50: 61–76, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robins JM, Hernan MA, Brumback B: Marginal structural models and causal inference in epidemiology. Epidemiology 11: 550–560, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Austin PC, Grootendorst P, Anderson GM: A comparison of the ability of different propensity score models to balance measured variables between treated and untreated subjects: A Monte Carlo study. Stat Med 26: 734–753, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Austin PC: Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat Med 28: 3083–3107, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lucet JC, Bouadma L, Zahar JR, Schwebel C, Geffroy A, Pease S, Herault MC, Haouache H, Adrie C, Thuong M, Français A, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Timsit JF: Infectious risk associated with arterial catheters compared with central venous catheters. Crit Care Med 38: 1030–1035, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rijnders BJ, Van Wijngaerden E, Peetermans WE: Catheter-tip colonization as a surrogate end point in clinical studies on catheter-related bloodstream infection: How strong is the evidence? Clin Infect Dis 35: 1053–1058, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Souweine B, Traore O, Aublet-Cuvelier B, Badrikian L, Bret L, Sirot J, Gazuy N, Laveran H, Deteix P: Dialysis and central venous catheter infections in critically ill patients: Results of a prospective study. Crit Care Med 27: 2394–2398, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Souweine B, Liotier J, Heng AE, Isnard M, Ackoundou-N'Guessan C, Deteix P, Traoré O: Catheter colonization in acute renal failure patients: Comparison of central venous and dialysis catheters. Am J Kidney Dis 47: 879–887, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wester JP, de Koning EJ, Geers AB, Vincent HH, de Jongh BM, Tersmette M, Leusink JA: Analysis of Renal Replacement Therapy in the Seriously Ill (ARTIS) Investigators. Catheter replacement in continuous arteriovenous hemodiafiltration: The balance between infectious and mechanical complications. Crit Care Med 30: 1261–1266, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lemaire X, Morena M, Leray-Moragues H, Henriet-Viprey D, Chenine L, Defez-Fougeron C, Canaud B: Analysis of risk factors for catheter-related bacteremia in 2000 permanent dual catheters for hemodialysis. Blood Purif 28: 21–28, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schneid-Kofman N, Sheiner E, Levy A, Holcberg G: Risk factors for wound infection following cesarean deliveries. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 90: 10–15, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gress TW, Nieto FJ, Shahar E, Wofford MR, Brancati FL: Hypertension and antihypertensive therapy as risk factors for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. N Engl J Med 342: 905–912, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mukamal KJ, Ghimire S, Pandey R, O'Meara ES, Gautam S: Antihypertensive medications and risk of community-acquired pneumonia. J Hypertens 28: 401–405, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Antonios TF, Rattray FM, Singer DR, Markandu ND, Mortimer PS, MacGregor GA: Rarefaction of skin capillaries in normotensive offspring of individuals with essential hypertension. Heart 89: 175–178, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Souweine B, Heng AE, Aumeran C, Thiolliere F, Gazuy N, Deteix P, Traoré O: Do antibiotics administered at the time of central venous catheter removal interfere with the evaluation of colonization? Intensive Care Med 34: 286–291, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rupp ME, Lisco SJ, Lipsett PA, Perl TM, Keating K, Civetta JM, Mermel LA, Lee D, Dellinger EP, Donahoe M, Giles D, Pfaller MA, Maki DG, Sherertz R: Effect of a second-generation venous catheter impregnated with chlorhexidine and silver sulfadiazine on central catheter-related infections: A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 143: 570–580, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kellum JA, Song M, Li J: Science review: Extracellular acidosis and the immune response: Clinical and physiologic implications. Crit Care 8: 331–336, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Unno N, Hodin RA, Fink MP: Acidic conditions exacerbate interferon-gamma-induced intestinal epithelial hyperpermeability: Role of peroxynitrous acid. Crit Care Med 27: 1429–1436, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oliver MJ, Callery SM, Thorpe KE, Schwab SJ, Churchill DN: Risk of bacteremia from temporary hemodialysis catheters by site of insertion and duration of use: A prospective study. Kidney Int 58: 2543–2545, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harb A, Estphan G, Nitenberg G, Chachaty E, Raynard B, Blot F: Indwelling time and risk of infection of dialysis catheters in critically ill cancer patients. Intensive Care Med 31: 812–817, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Catton JA, Dobbins BM, Kite P, Wood JM, Eastwood K, Sugden S, Sandoe JA, Burke D, McMahon MJ, Wilcox MH: In situ diagnosis of intravascular catheter-related bloodstream infection: A comparison of quantitative culture, differential time to positivity, and endoluminal brushing. Crit Care Med 33: 787–791, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]