Abstract

Background and objectives: Patients in ESRD on hemodialysis with latent tuberculosis (TB) infection have 10 to 25 times the risk of reactivation into active disease compared with healthy adults. This study investigates the prevalence of latent TB infection in dialysis patients from a country with an intermediate burden of TB and its associated risk factors using the QuantiFERON-TB Gold in-tube test (QGIT) and the tuberculin skin test (TST).

Design, setting, participants, & measurements: This was a prospective, cross-sectional study performed at a medical center in Taiwan on dialysis patients. Each patient underwent QGIT, two-step TST using 2 tuberculin units (TU) of PPD RT-23, a chest x-ray to exclude active TB, and an interview to determine TB risk factors.

Results: Ninety-three of 190 eligible patients were enrolled: 35 men and 58 women. 64.8% were vaccinated with the Bacille-Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination. Overall, 34.4% were positive by QGIT and 10.8% were indeterminate. Using a 10-mm TST cutoff, 53.9% were positive. There was poor correlation between TST and QGIT at any TST cutoff criteria. There was a significant increasing trend of QGIT positivity with age in those younger than 70 years, and, conversely, a decreasing trend of TST reactivity with age. Significant risk factors for QGIT positivity included age and past TB disease.

Conclusions: This study shows a high prevalence of latent TB infection in dialysis patients in a country with an intermediate burden of TB. QGIT in dialysis patients correlated better than TST with the risk of TB infection and past TB disease.

Tuberculosis (TB) remains one the world's major causes of illness and death. The World Health Organization estimates that 9.27 million new cases of TB occurred in 2007, causing approximately 1.3 million deaths (1). Taiwan has an intermediate burden of TB with a prevalence of 111 per 100,000, an incidence of 63.2 per 100,000, causing 3.4 per 100,000 deaths in 2007 (2). In 2006, Taiwan reported the highest rates of incident and prevalent ESRD requiring hemodialysis in the world at 418 and 2226 per million population, respectively (3). The annual incidence of TB in the Taiwanese dialysis population was 493.4 per 100,000 in 1997, which was 6.9 times higher than that of the general population (71.1 per 100,000) (4). Overall 1-year mortality in dialysis patients with TB was higher than in the general TB population (27.3% versus 13.0%, P < 0.05), but deaths attributable directly to TB were not different (1.7% versus 1.9%, P > 0.05) (4).

TB remains an important factor in the morbidity and mortality of hemodialysis patients. It is well known that ESRD is accompanied by disturbances of the immune system (mainly the T lymphocyte and the antigen-presenting cell), thereby increasing susceptibility to infections (5,6). The interaction between the T lymphocyte and the macrophage plays an important role in the response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis (6). Studies have shown that the relative risk for active TB in ESRD patients is increased from 7 to 25 times (4,7,8). In addition, diabetes is a major cause of ESRD (causing over 40% of incident ESRD (3)) and results in an increased risk (2 to 4 times) of active TB (9). Therefore, ESRD patients with diabetes are at dual risk of developing active TB.

Recommendations to screen dialysis patients for latent TB infection intend to reduce transmission of TB in these high-risk settings (9) where patients spend long periods together, thus increasing the transmission potential (10,11). The prevalence of latent TB infection in ESRD patients varies from 11% to 63% using the tuberculin skin test (TST) (12–14). The TST may grossly underestimate the prevalence because of the high rates of cutaneous anergy (up to 44%) (10,15–17) and is limited by a low specificity, with cross-reactions to Bacille-Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination and exposure to nontuberculous mycobacteria.

IFN-γ release assays are recently developed T cell-based whole blood tests for the diagnosis of latent TB infection (18). QuantiFERON-TB GOLD (QFT-G) (2nd generation) uses ELISA to measure the IFN-γ release of sensitized T lymphocytes in response to M. tuberculosis-specific antigen, early secreted antigenic target 6, and culture filtrate protein 10. QuantiFERON-TB Gold in-tube test (QGIT) (3rd generation) has an additional antigen, TB 7.7. These tests have many advantages over the TST (19,20) in terms of higher specificity and less cross-reactivity in the BCG-vaccinated population and nontuberculous mycobacteria infections. It also demonstrates better correlation with exposure to M. tuberculosis and better performance in immunocompromised patients, including patients with HIV infection and rheumatoid arthritis (21–23). Only a few studies have evaluated the performance of IFN-γ release assays in diagnosing M. tuberculosis infection in renal dialysis patients. These studies were done in developed countries with a low incidence of TB (24–26). One study in Japan evaluated the utility of QFT-G in the diagnosis of suspected active TB in dialysis patients (27).

A pilot study done in Taiwan by our group in 2004 (28) showed a high prevalence of latent TB infection by TST (62.5%), QFT-G (40.0%), and the ELISPOT test (46.9%). This study aims to (1) investigate the prevalence of latent TB infection in dialysis patients in a country with an intermediate burden of TB using the 3rd generation QGIT and the TST, and (2) determine risk factors associated with QGIT and TST positivity.

Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional study was approved by the hospital institutional review board and recruited hemodialysis patients attending one outpatient hemodialysis unit at the Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital, a medical center in southern Taiwan, in October 2008. Of the 190 patients eligible for the study, 93 (49.0%) consented. Patients with active TB were excluded from the study.

An interview and questionnaire collected basic demographic information, BCG vaccination, past TB disease, and TB contact data and recorded serum albumin levels drawn within 3 months. Whole blood (3 ml) was drawn before intradermal testing. The QFT-G test (Cellestis Limited, Melbourne, Australia) was performed according to manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 1 ml of blood was drawn into vacutainer tubes coated with saline (negative control), peptides of early secreted antigenic target 6, culture filtrate protein 10, TB 7.7, or phytohemagglutinin (PHA, a positive mitogen control). Tubes were incubated for 16 to 24 hours at 37°C, centrifuged, and plasma was frozen until ELISA for IFN-γ production was done. QFT-G Analysis Software, available for download from the Cellestis Ltd. website (29), was used to for quality control assessment and to calculate the test results. A positive result was defined as an IFN-γ response to TB antigen of ≥0.35 IU/ml above the background level and at least 25% of the background IFN-γ level in the absence of high background level (≤8.0 IU/ml). Indeterminate results were defined as IFN-γ response to TB antigen of <0.35 IU/ml or <25% of the background level, and either a background IFN-γ level of >8.0 IU/ml or an IFN-γ response of <0.5 IU/ml above the background level to PHA (30).

A two-step TST was performed using 2 tuberculin units (TU) of tuberculin RT-23 (PPD RT-23 SSI, Statens Serum Institut, Copenhagen, Denmark) according to the Mantoux method. One experienced study nurse read the reactions after 48 to 72 hours. A positive TST was defined as an induration of ≥10 mm. If an initial TST was negative, a second TST was placed 1 to 3 weeks later to detect a booster response. The booster phenomenon is thought to represent remote TB infection among elderly persons (31,32) in which waning of immunological response with age initially results in a false-negative TST. The first TST reawakens the immune response so that a second TST will become positive. A two-step approach can reduce the likelihood that a boosted reaction to a subsequent TST will be misinterpreted as a recent infection or new conversion (9). All chest x-rays were reviewed by one radiologist blinded to clinical information and the test results.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using STATA version 10 (STATA Corporation, College Station, TX). The t test or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used for comparisons of continuous variables between groups. Categorical variables were compared using the Pearson's χ2 test or Fisher's exact test as appropriate. A P value <0.05 was considered significant. All reported P values were two-sided.

Concordance was calculated as the overall percent agreement between TST and QGIT using 2 × 2 contingency tables. The strength of this agreement was assessed using the kappa (κ) statistic (33). Multivariable analysis of risk factors was done by logistic regression. The final model was selected using the forward selection method and likelihood ratio test. Age and sex were included in the model a priori.

Results

Of the 190 patients attending one hemodialysis center, 93 (49.0%) entered the study. None had active TB by chest x-rays or symptoms of fever, cough, or body weight loss. The mean age was 58.3 years (SD = 14.9, range 16.8 to 93.5 years) with 35 men and 58 women (Table 1). Over half (64.8%) had received BCG vaccination. Twenty-two (23.7%) patients had diabetes mellitus. Common causes of ESRD included chronic interstitial nephritis (n = 38, 40.9%), chronic GN (n = 15, 16.1%), and diabetic nephropathy (n = 17, 18.3%). The median dialysis vintage was 6 years (interquartile range [IQR] 4 to 10 years). Only three (3.2%) patients admitted to contact with cases of active TB who were family members, and another one (1.2%) had a nonhousehold family member who had active TB. Nine (10.8%) patients had past TB disease, and six (6.5%) had evidence of past pulmonary TB on chest x-ray. Over one-quarter of patients (24 of 88, 27.3%) had malnutrition, defined as a body mass index <20. Patients with malnutrition were less likely to have a positive TST (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 0.44, P = 0.39) and QGIT result (adjusted OR 0.46, P = 0.21), although not reaching statistical significance and not associated with indeterminate responses. Only 13.2% (12 of 91) had a lowered albumin level (<3.7 g/dl). Patients with hypoalbuminemia tended to have an indeterminate response (25.0% versus 8.9%, P = 0.12, OR = 3.43, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.75 to 15.7, P = 0.11), although this did not reach statistical significance.

Table 1.

Basic demographic characteristics of ESRD patients at one hemodialysis center that entered the study (n = 93)

| Basic Characteristics | Study Group (n = 93) |

|---|---|

| Age in years, mean ± SD (range) | 58.3 ± 14.9 (16.8 to 93.5) |

| Male gender, n (%) | 35 (37.6) |

| BCG vaccination, yes, n (%) | 57 (64.8) |

| Dialysis vintage in years, median (IQR) (range) | 6 (4 to 10) (0.3 to 20) |

| Cause of chronic renal failure, n (%) | |

| chronic GN | 15 (16.1) |

| chronic interstitial nephritis | 38 (40.9) |

| diabetic nephropathy | 17 (18.3) |

| others | 7 (7.5) |

| unknown | 16 (17.2) |

| BMI, median, (IQR) | 21.5 (19.8 to 23.5) |

| Diabetes mellitus, yes, n (%) | 22 (23.7) |

| Family history of TB, n (%) | 4 (4.3) |

| History of TB disease, n (%) | 9 (10.8) |

| History of TB contact, n (%) | 3 (3.2) |

| Radiographic evidence of old TB, n (%) | 6 (6.5) |

BMI, body mass index.

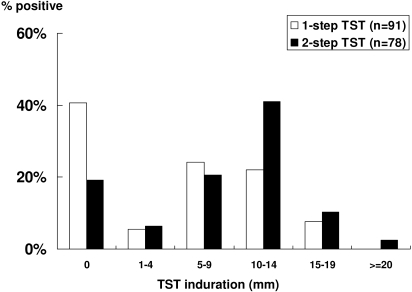

TST

TST was done in 91 patients and was positive in 27 (29.7%) patients using a 10-mm cutoff (one-step TST). Of the 64 (70.3%) who had a negative TST, only 51 patients completed a second TST (two-step TST). Overall, TST was positive in 53.9% (42 of 78) after a second TST was done. A booster effect occurred in 15 of 51 (29.4%) patients, halving the proportion having a nonreactive (0 mm) response from 40.7% to 19.2% (Figure 1). The median one-step TST induration was 5.3 mm (IQR 0.0 to 10.5), and the median two-step TST induration was 6.5 mm (IQR 0.0 to 10.0). TST reactivity was not influenced by BCG vaccination (P = 0.60), but QGIT positivity tended to be lower in BCG-vaccinated persons (50.0% versus 34.0%, P = 0.17).

Figure 1.

Distribution of TST induration and the booster effect of a two-step TST in dialysis patients.

QGIT

Overall, 32 patients (34.4%, 95% CI 24.9 to 45.0) were positive by QGIT, and 10 patients (10.8%, 95% CI 5.3 to 18.9%) were indeterminate. The test was indeterminate in nine subjects because of insufficient response to PHA and in one subject because of a high background of IFN-γ level. Excluding those with indeterminate results, 38.6% (95% CI 28.1 to 49.9) were positive by QGIT. QGIT was positive in all three patients who were in contact with TB patients, and in six of nine patients who had past TB disease. TB disease occurred >6 years previously in the three patients with a negative QGIT. Four patients with a history of TB disease had a false-negative TST.

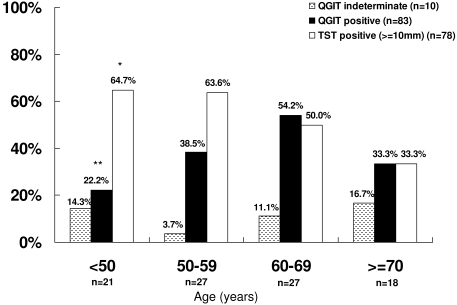

There was a significantly increasing trend of a positive QGIT with increasing age by decade when excluding those >70 years (OR 1.93, 95% CI 1.04 to 3.58, P = 0.04) (Figure 2). Although not reaching statistical significance, we observed that indeterminate results increased with increasing age by decade when excluding those <50 years of age (OR 2.09, 95% CI 0.77 to 5.63, P = 0.15) (Figure 2) and were seen more frequently in patients with diabetes (18.2% versus 8.5%, P = 0.24).

Figure 2.

Association of age with the prevalence of latent TB infection in dialysis patients using the QGIT and the TST and association of age with indeterminate responses of QGIT. *Test for trend: OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.43 to 0.99, P = 0.05. **Test for trend excluding age ≥70 years: OR 1.93, 95% CI 1.04 to 3.58, P = 0.04. Overall agreement between QGIT and TST excluding indeterminate results: 57.8%, κ = 0.16.

There was poor correlation between TST and QGIT at any cutoff criteria of TST (Table 2). In the 15 patients with nonreactive (0 mm) response in TST, 12 (80.0%) were also negative by QGIT, but 1 (6.7%) was positive and 2 (13.3%) were indeterminate.

Table 2.

Correlation between QGIT and the TST in dialysis patients

| TST Cutoff (mm) | Overall Agreement (%) | κ | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| One-step TST | |||

| 5 | 57.5 | 0.17 | −0.04 to 0.38 |

| 10 | 67.5 | 0.28 | 0.06 to 0.50 |

| 15 | 62.5 | 0.08 | −0.07 to 0.23 |

| 18 | 60.0 | −0.02 | −0.09 to 0.04 |

| Two-step TST | |||

| 5 | 58.9 | 0.24 | 0.05 to 0.42 |

| 10 | 57.8 | 0.16 | −0.07 to 0.39 |

| 15 | 65.6 | 0.23 | 0.03 to 0.44 |

| 18 | 63.8 | 0.12 | −0.04 to 0.27 |

Excluded from analysis are those with indeterminate responses (n = 10) and those without TST results (n = 3).

Risk Factors for TST Positivity

On multivariable analysis, TST was less likely to be reactive in elderly patients >70 years of age (adjusted OR 0.18, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.89, P = 0.04) (Table 3). There was a decreasing trend of a reactive TST (≥10 mm) with increasing age by decade when compared with patients <50 years of age (OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.43 to 0.99, test for trend, P = 0.05) (Figure 2). A significant increase in the frequency of a nonreactive TST (0 mm) was observed with increasing age (OR 1.97 per decade increase in age, 95% CI 1.14 to 3.40, test for trend, P = 0.02).

Table 3.

Risk factors for a positive TST in dialysis patients (n = 83)

| Risk Factor | Crude OR | 95% CI | P | Adjusted ORa | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||||||

| <50 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| 50 to 59 | 0.95 | 0.25 to 3.58 | 0.95 | 0.76 | 0.18 to 3.13 | 0.70 |

| 60 to 69 | 0.55 | 0.15 to 1.96 | 0.35 | 0.56 | 0.14 to 2.23 | 0.41 |

| ≥70 | 0.27 | 0.06 to 1.18 | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.03 to 0.84 | 0.03 |

| Gender, male | 0.78 | 0.31 to 1.94 | 0.59 | 0.98 | 0.35 to 2.75 | 0.98 |

| BCG vaccination | 1.29 | 0.50 to 3.27 | 0.60 | 0.78 | 0.23 to 2.64 | 0.70 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.24 | 0.44 to 3.53 | 0.68 | 1.62 | 0.42 to 6.29 | 0.49 |

| Malnutrition with BMI < 20 | 0.63 | 0.23 to 1.77 | 0.39 | 0.44 | 0.13 to 1.46 | 0.18 |

| Dialysis vintage, years | ||||||

| <4 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| 4 to 9 | 0.31 | 0.09 to 1.05 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0.06 to 0.96 | 0.04 |

| ≥10 | 0.82 | 0.24 to 2.81 | 0.75 | 0.62 | 0.16 to 2.37 | 0.49 |

| Past TB disease | 0.62 | 0.13 to 2.95 | 0.54 | 1.03 | 0.18 to 6.03 | 0.97 |

| Evidence of past TB on chest x-ray | 0.40 | 0.07 to 2.32 | 0.31 | 0.60 | 0.08 to 4.49 | 0.62 |

| QGIT positive | 1.94 | 0.75 to 5.02 | 0.18 | 2.33 | 0.73 to 7.43 | 0.15 |

Adjusted for age, gender, and dialysis vintage. A positive TST was defined as a two-step TST with a 10-mm cutoff.

Risk Factors for QGIT Positivity

Multivariable analysis showed that patients between 60 and 69 years of age (adjusted OR 5.10, 95% CI 1.07 to 24.28, P = 0.04) and those with past TB disease (adjusted OR 5.32, 95% CI 1.01 to 28.03, P = 0.05) had significantly higher risks of a positive QGIT after controlling for age, sex, and dialysis vintage (Table 4). Dialysis vintage (≥4 years) was associated with a negative QGIT result (adjusted OR 0.21, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.82, P = 0.03). There was no difference in the distribution of age in those with different dialysis vintage (P = 0.66).

Table 4.

Risk factors for a positive QGIT in dialysis patients (n = 83)

| Risk Factor | Crude OR | 95% CI | P | Adjusted ORa | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yearsb | ||||||

| <50 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| 50 to 59 | 2.19 | 0.56 to 8.55 | 0.26 | 2.61 | 0.58 to 11.68 | 0.21 |

| 60 to 69 | 4.14 | 1.05 to 16.29 | 0.04 | 5.10 | 1.07 to 24.28 | 0.04 |

| ≥70 | 1.75 | 0.37 to 8.20 | 0.48 | 1.91 | 0.34 to 10.81 | 0.47 |

| Gender, male | 1.31 | 0.53 to 3.22 | 0.56 | 1.32 | 0.47 to 3.66 | 0.60 |

| BCG vaccination | 0.52 | 0.20 to 1.32 | 0.17 | 0.50 | 0.16 to 1.62 | 0.25 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.83 | 0.64 to 5.24 | 0.26 | 0.58 | 0.15 to 2.21 | 0.43 |

| Malnutrition with BMI < 20 | 0.54 | 0.18 to 1.58 | 0.26 | 0.46 | 0.14 to 1.54 | 0.21 |

| Dialysis vintage, yearsc | ||||||

| <4 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| 4 to 9 | 0.32 | 0.09 to 1.09 | 0.07 | 0.21 | 0.05 to 0.82 | 0.03 |

| ≥10 | 0.25 | 0.07 to 0.86 | 0.03 | 0.22 | 0.06 to 0.81 | 0.02 |

| Past TB disease | 3.69 | 0.85 to 15.99 | 0.08 | 5.32 | 1.01 to 28.03 | 0.05 |

| Evidence of past TB on chest x-ray | 2.53 | 0.40 to 16.07 | 0.32 | 5.18 | 0.68 to 39.65 | 0.11 |

| TST ≥10 mm | 1.94 | 0.75 to 5.02 | 0.18 | 2.39 | 0.75 to 7.62 | 0.14 |

Adjusted for age, gender, and dialysis vintage.

Test for trend excluding those aged <70 years: OR 1.93, 95% CI 1.04 to 3.58, test for trend P = 0.04.

Test for trend: OR 0.53, 95% CI 0.30 to 0.96, test for trend P = 0.04.

There was a trend toward a positive QGIT with increasing age in those <70 years (OR 1.93, 95% CI 1.04 to 3.58, test for trend P = 0.04) (Figure 2), and a trend toward a negative QGIT with increasing dialysis vintage (OR 0.53, 95% CI 0.30 to 0.96, test for trend P = 0.04).

Discussion

This study showed that hemodialysis patients from a country with an intermediate burden of TB has a high prevalence of latent TB using the QGIT (34.4%) and the two-step TST at a cutoff of 10 mm (53.9%). These results are consistent with our previous report (28) and use a newer version of QFT tests. A positive QGIT was significantly associated with age and those with past TB disease in dialysis patients, whereas the TST was not.

In contrast to previous studies done in dialysis patients in low-incidence countries (25,26) where aging was associated with a positive TST, we found that older patients were more likely to have a negative TST. However, we also found that QGIT positivity correlated with aging (test for trend: OR 1.93, P = 0.04), in patients <70 years of age, whereas TST reactivity displayed a negative trend with increasing age (OR 0.65, P = 0.05). It appears that in elderly dialysis patients the QGIT was more frequently positive and the TST was less frequently positive.

Dialysis patients are not only at higher risk for reactivation of TB disease, but also more subject to patient-to-patient transmission within dialysis centers. Previous studies involved dialysis patients in countries with a low incidence of TB. In Geneva, Switzerland, QGIT positivity rate was 21% and 19% by TST (26). In the United States, within the setting of contact investigation, QFT-G positivity was 22% and 26% by TST (25). A study done in Tokyo, Japan (34) used QFT-G to evaluate dialysis patients with suspected active TB and found a positive rate of 17.9%. The high prevalence of latent TB infection in dialysis patients in this study supports the recommendations by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control that routine screening and treatment of latent TB infection should be done for dialysis patients (9). This is especially important for foreign-born individuals from countries endemic for TB.

Patients in ESRD have high rates of cutaneous anergy when using the TST (10,17). A nonreactive TST (0 mm) may indicate that a patient did not have latent TB infection or had TB infection but was anergic. In our study, most (80.0%) patients with a nonreactive response were negative by QGIT; however, one (6.7%) had a positive QGIT and two (13.3%) were indeterminate. With increasing age, there was a significantly increased frequency of a positive test by QGIT, but, in contrast, the TST demonstrated a significantly increased proportion with a nonreactive (0 mm) result. Because the prevalence of latent TB infection is expected to increase with age, and older people lived in a time when TB was much more prevalent than in later generations (35,36), this finding suggests that QGIT better reflected the increased risk of TB infection with aging. Winthrop et al. (25) also found during a contact investigation of dialysis patients that a positive QFT-G, but not a positive TST, was associated with increasing age.

The reduced prevalence of QGIT positivity in those aged ≥70 years compared with those younger along with an increased proportion showing an indeterminate response (16.7%), all because of lack of mitogen response, infer that impaired immune response to testing (i.e., anergy) may be a possible explanation. Another explanation would be survivor bias, in which selection bias of older people occurs in association with a high death rate in younger patients with TB. Cross-sectional studies done in countries with decreasing incidence of TB demonstrated the highest mortality in the older age groups, which reflected the higher risk of TB disease experienced by these cohorts when they were young (36). However, for each birth cohort, mortality is highest in the young (aged 20 to 30 years) (35,36). Therefore, it is possible that individuals who survived to old age include those who did not contract TB in their youth and die, thus resulting in a lowered prevalence of latent TB infection in those >70 years of age.

In this study, a longer dialysis vintage (≥4 years) was associated with a negative QGIT response. Hemodialysis itself may contribute to immune deficiency in ESRD patients through a proapoptotic effect due to direct blood contact with dialysis membranes that may affect the cell-mediated immune reactions (37).

The significance of indeterminate tests is not clear but may represent anergy in the case in which there is insufficient response to PHA (positive mitogen control). Indeterminate responses may occur up to 10.2% in routine clinical practice (38) and are associated with elderly and immunocompromised patients, such as those with HIV/AIDS, lymphocytopenia, and hypoalbuminemia (38). In our study, patients with hypoalbuminemia, but not malnutrition, tended to have an indeterminate response. In children, indeterminate results correlated with age and immune status (39). In dialysis patients, indeterminate results occurred in 8% of QFT and 11% of T-SPOT-TB (26), and up to 24.1% using QFT in those with suspected TB in Japan (27). Indeterminate results occurred in only 6.3% of dialysis patients compared with none of the healthy controls in a small study done by our group (28). The study presented here showed an indeterminate response in 10.8% of dialysis patients. We also observed increasing indeterminate results with increasing age by decade when excluding those <50 years of age, although this did not reach statistical significance (OR 2.09, P = 0.15). The reason why a high proportion of indeterminate results occurred in those <50 years of age was not immediately apparent.

The limitations of this study include the lack of a gold standard for the diagnosis of latent TB infection, which will require long-term follow-up for development of active TB disease. Up to February 2010 (16 months of follow-up), none of the patients developed active TB. Another limitation is that history of contact with TB patients was subject to recall bias, and contact may have occurred unbeknown to the patient. However, past and active TB disease was ascertained using the hospital TB database.

In conclusion, we found a high prevalence of latent TB infection in dialysis patients in a country with an intermediate burden of TB using TST and QGIT. QGIT in dialysis patients correlated better than TST with the risk of TB infection (e.g., age) and past TB disease.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Yi-Ting Lee for technical assistance. This work was supported by a grant from the National Health Research Institutes, Department of Health, Executive Yuan, Republic of China (NHRI-97 A1-CLCO-07-0709-1) and the Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital in Kaohsiung, Taiwan (VGHKS 97-33). This work was presented in part as an abstract/poster at the 49th Annual Meeting of the Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy (ICAAC); September 12 through 15, 2009; San Francisco, CA.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Global Tuberculosis Control, 2009: Epidemiology, Strategy, Financing, Geneva, Switzerland, World Health Organization Press, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taiwan Tuberculosis Control Report, 2009, Taipei, Taiwan, Centers for Disease Control, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Renal Data System: USRDS 2008 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States, Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chou KJ, Fang HC, Bai KJ, Hwang SJ, Yang WC, Chung HM: Tuberculosis in maintenance dialysis patients. Nephron 88: 138–143, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eleftheriadis T, Antoniadi G, Liakopoulos V, Kartsios C, Stefanidis I: Disturbances of acquired immunity in hemodialysis patients. Semin Dial 20: 440–451, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Newport MJ, Huxley CM, Huston S, Hawrylowicz CM, Oostra BA, Williamson R, Levin M: A mutation in the interferon-gamma-receptor gene and susceptibility to mycobacterial infection. N Engl J Med 335: 1941–1949, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lundin AP, Adler AJ, Berlyne GM, Friedman EA: Tuberculosis in patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis. Am J Med 67: 597–602, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chia S, Karim M, Elwood RK, FitzGerald JM: Risk of tuberculosis in dialysis patients: A population-based study. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2: 989–991, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control: Targeted tuberculin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 161: S221–S247, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smirnoff M, Patt C, Seckler B, Adler JJ: Tuberculin and anergy skin testing of patients receiving long-term hemodialysis. Chest 113: 25–27, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tuberculosis transmission in a renal dialysis center—Nevada, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 53: 873–875, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sester U, Junker H, Hodapp T, Schutz A, Thiele B, Meyerhans A, Kohler H, Sester M: Improved efficiency in detecting cellular immunity towards M. tuberculosis in patients receiving immunosuppressive drug therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 21: 3258–3268, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fang HC, Lee PT, Chen CL, Wu MJ, Chou KJ, Chung HM: Tuberculosis in patients with end-stage renal disease. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 8: 92–97, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yanai M, Uehara Y, Takeuchi M, Nagura Y, Hoshino T, Hayashi K, Kumasaka K: Evaluation of serological diagnosis tests for tuberculosis in hemodialysis patients. Ther Apher Dial 10: 278–281, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sester M, Sester U, Clauer P, Heine G, Mack U, Moll T, Sybrecht GW, Lalvani A, Kohler H: Tuberculin skin testing underestimates a high prevalence of latent tuberculosis infection in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 65: 1826–1834, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woeltje KF, Mathew A, Rothstein M, Seiler S, Fraser VJ: Tuberculosis infection and anergy in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 31: 848–852, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shankar MS, Aravindan AN, Sohal PM, Kohli HS, Sud K, Gupta KL, Sakhuja V, Jha V: The prevalence of tuberculin sensitivity and anergy in chronic renal failure in an endemic area: Tuberculin test and the risk of post-transplant tuberculosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 20: 2720–2724, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Menzies D, Pai M, Comstock G: Meta-analysis: New tests for the diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection: Areas of uncertainty and recommendations for research. Ann Intern Med 146: 340–354, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pai M, Zwerling A, Menzies D: Systematic review: T-cell-based assays for the diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection: An update. Ann Intern Med 149: 177–184, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pai M, Riley LW, Colford JM, Jr: Interferon-gamma assays in the immunodiagnosis of tuberculosis: A systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis 4: 761–776, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richeldi L, Losi M, D'Amico R, Luppi M, Ferrari A, Mussini C, Codeluppi M, Cocchi S, Prati F, Paci V, Meacci M, Meccugni B, Rumpianesi F, Roversi P, Cerri S, Luppi F, Ferrara G, Latorre I, Gerunda GE, Torelli G, Esposito R, Fabbri LM: Performance of tests for latent tuberculosis in different groups of immunocompromised patients. Chest 136: 198–204, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stephan C, Wolf T, Goetsch U, Bellinger O, Nisius G, Oremek G, Rakus Z, Gottschalk R, Stark S, Brodt HR, Staszewski S: Comparing QuantiFERON-tuberculosis gold, T-SPOT tuberculosis and tuberculin skin test in HIV-infected individuals from a low prevalence tuberculosis country. AIDS 22: 2471–2479, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ponce de Leon D, Acevedo-Vasquez E, Alvizuri S, Gutierrez C, Cucho M, Alfaro J, Perich R, Sanchez-Torres A, Pastor C, Sanchez-Schwartz C, Medina M, Gamboa R, Ugarte M: Comparison of an interferon-gamma assay with tuberculin skin testing for detection of tuberculosis (TB) infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in a TB-endemic population. J Rheumatol 35: 776–781, 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Passalent L, Khan K, Richardson R, Wang J, Dedier H, Gardam M: Detecting latent tuberculosis infection in hemodialysis patients: A head-to-head comparison of the T-SPOT.TB test, tuberculin skin test, and an expert physician panel. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2: 68–73, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Winthrop KL, Nyendak M, Calvet H, Oh P, Lo M, Swarbrick G, Johnson C, Lewinsohn DA, Lewinsohn DM, Mazurek GH: Interferon-gamma release assays for diagnosing Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in renal dialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 1357–1363, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Triverio PA, Bridevaux PO, Roux-Lombard P, Niksic L, Rochat T, Martin PY, Saudan P, Janssens JP: Interferon-gamma release assays versus tuberculin skin testing for detection of latent tuberculosis in chronic haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 1952–1956, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inoue T, Nakamura T, Katsuma A, Masumoto S, Minami E, Katagiri D, Hoshino T, Shibata M, Tada M, Hinoshita F: The value of QuantiFERON TB-Gold in the diagnosis of tuberculosis among dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 2252–2257, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee SS, Chou KJ, Su IJ, Chen YS, Fang HC, Huang TS, Tsai HC, Wann SR, Lin HH, Liu YC: High prevalence of latent tuberculosis infection in patients in end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis: Comparison of QuantiFERON-TB GOLD, ELISPOT, and tuberculin skin test. Infection 37: 96–102, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.QuantiFERON®-TB Gold Analysis Software, Carnegie, Australia, Cellestis Ltd., 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 30.QuantiFERON®-TB Gold In-Tube [package insert]. Carnegie, Australia, Cellestis Ltd., 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Menzies R, Vissandjee B, Rocher I, St Germain Y: The booster effect in two-step tuberculin testing among young adults in Montreal. Ann Intern Med 120: 190–198, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Menzies D: Interpretation of repeated tuberculin tests. Boosting, conversion, and reversion. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 159: 15–21, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Landis JR, Koch GG: An application of hierarchical kappa-type statistics in the assessment of majority agreement among multiple observers. Biometrics 33: 363–374, 1977 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Inoue T, Nakamura T, Katsuma A, Masumoto S, Minami E, Katagiri D, Hoshino T, Shibata M, Tada M, Hinoshita F: The value of QuantiFERON(R)TB-Gold in the diagnosis of tuberculosis among dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant, 24: 2605–2606, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frost WH: The age selection of mortality from tuberculosis in successive decades. Am J Hygiene 30: 91–96, 1939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nelson KE: Epidemiology of infectious diseases: General principles. In: Infectious Disease Epidemiology: Theory and Practice, edited by Nelson KE, Williams CM.Sudbury, MA, Jones and Bartlett Publishers, 2007:52–53 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martin-Malo A, Carracedo J, Ramirez R, Rodriguez-Benot A, Soriano S, Rodriguez M, Aljama P: Effect of uremia and dialysis modality on mononuclear cell apoptosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 936–942, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kobashi Y, Sugiu T, Mouri K, Obase Y, Miyashita N, Oka M: Indeterminate results of QuantiFERON TB-2G test performed in routine clinical practice. Eur Respir J 33: 812–815, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haustein T, Ridout DA, Hartley JC, Thaker U, Shingadia D, Klein NJ, Novelli V, Dixon GL: The likelihood of an indeterminate test result from a whole-blood interferon-gamma release assay for the diagnosis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in children correlates with age and immune status. Pediatr Infect Dis J 28: 669–673, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]