Abstract

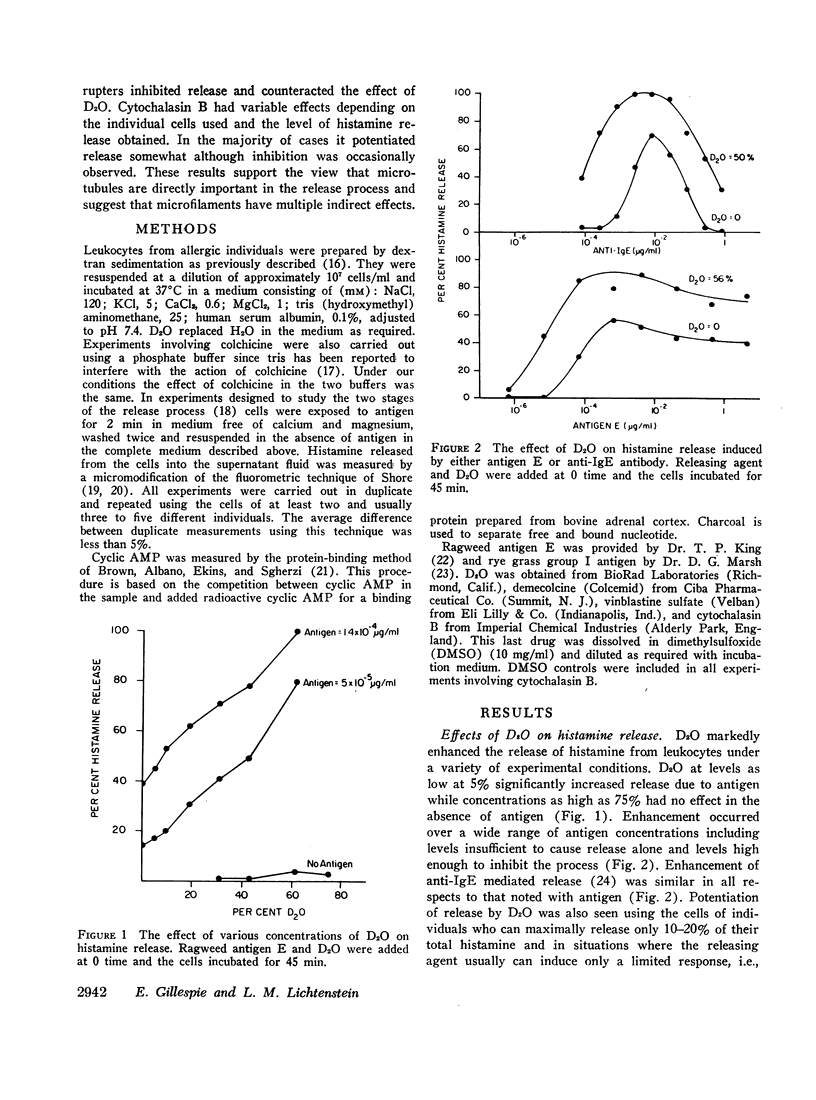

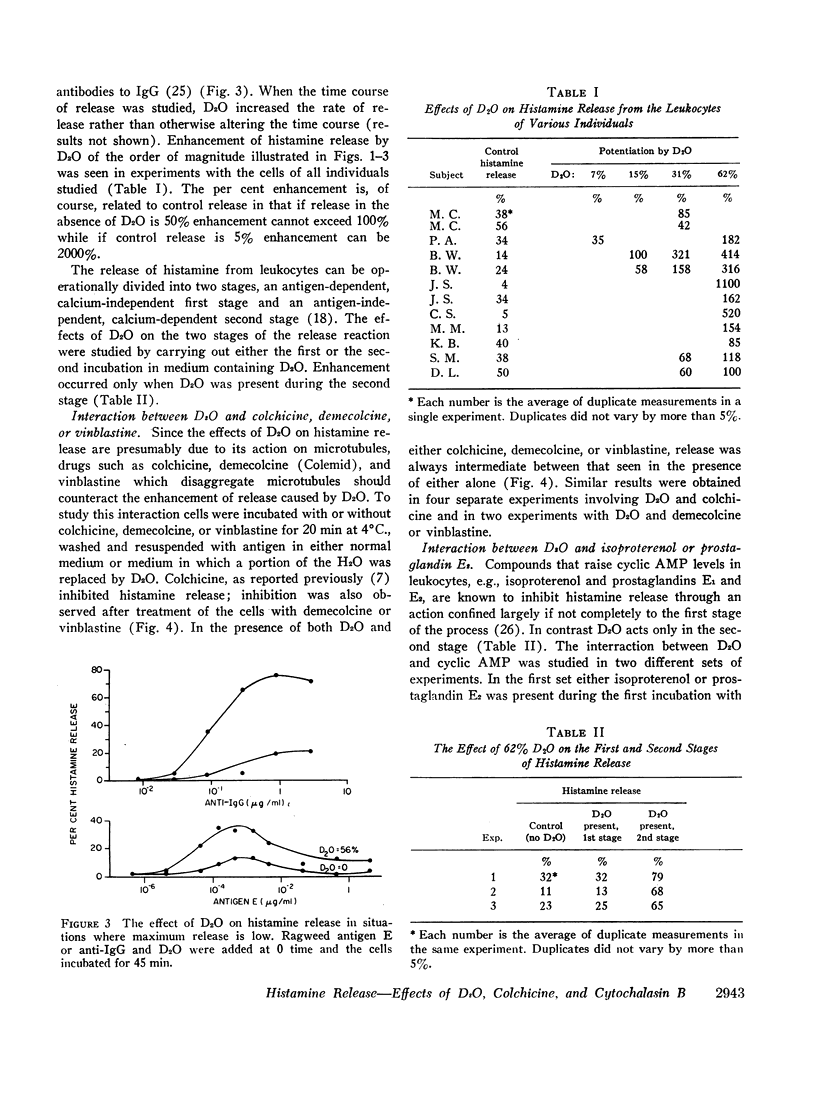

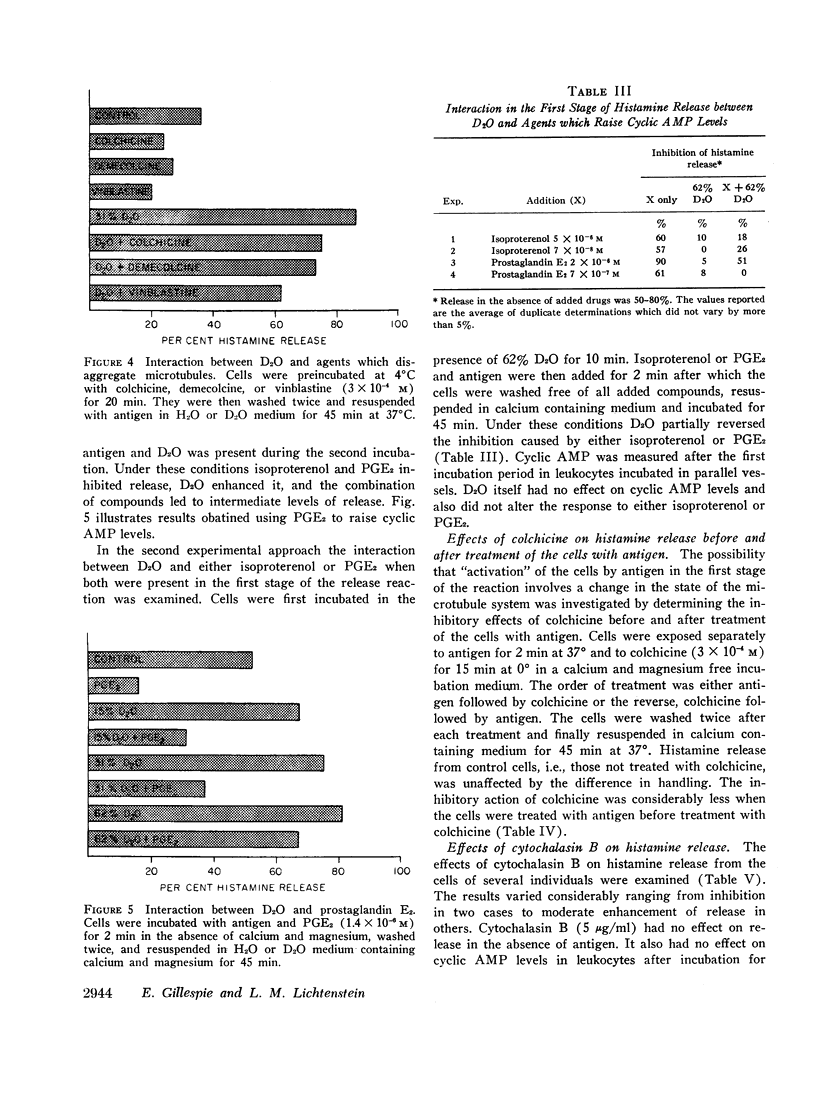

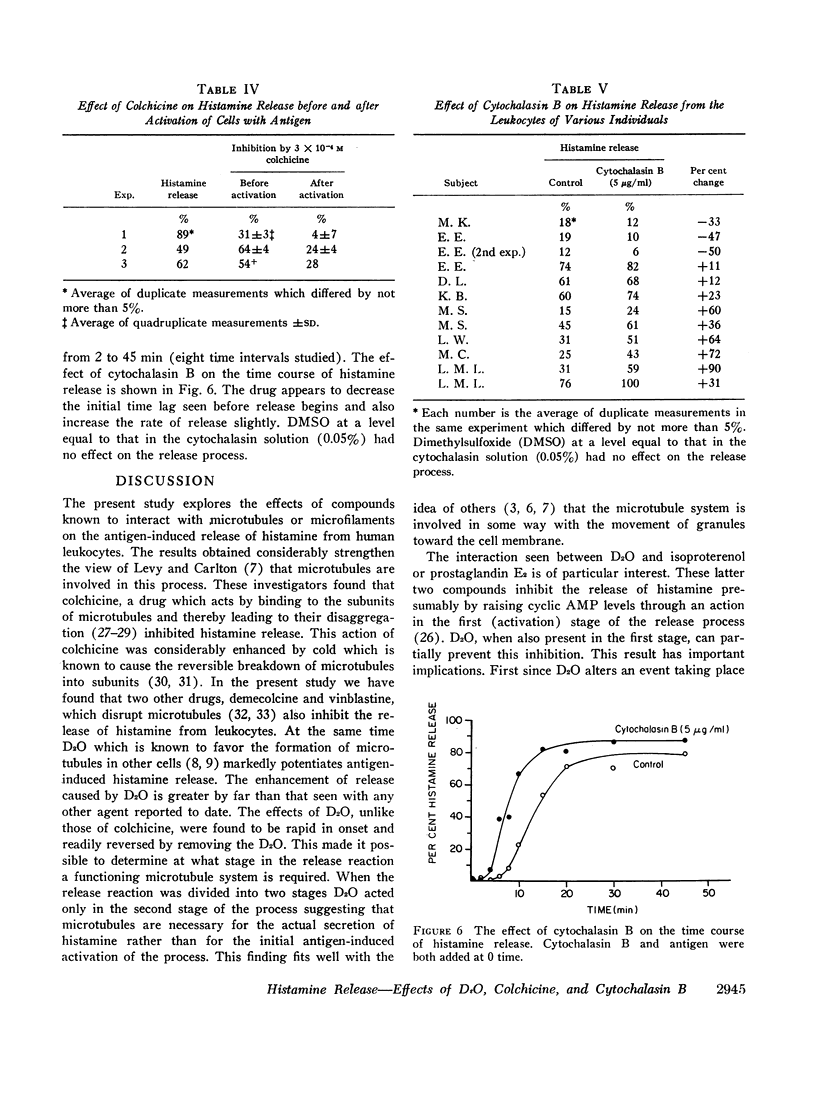

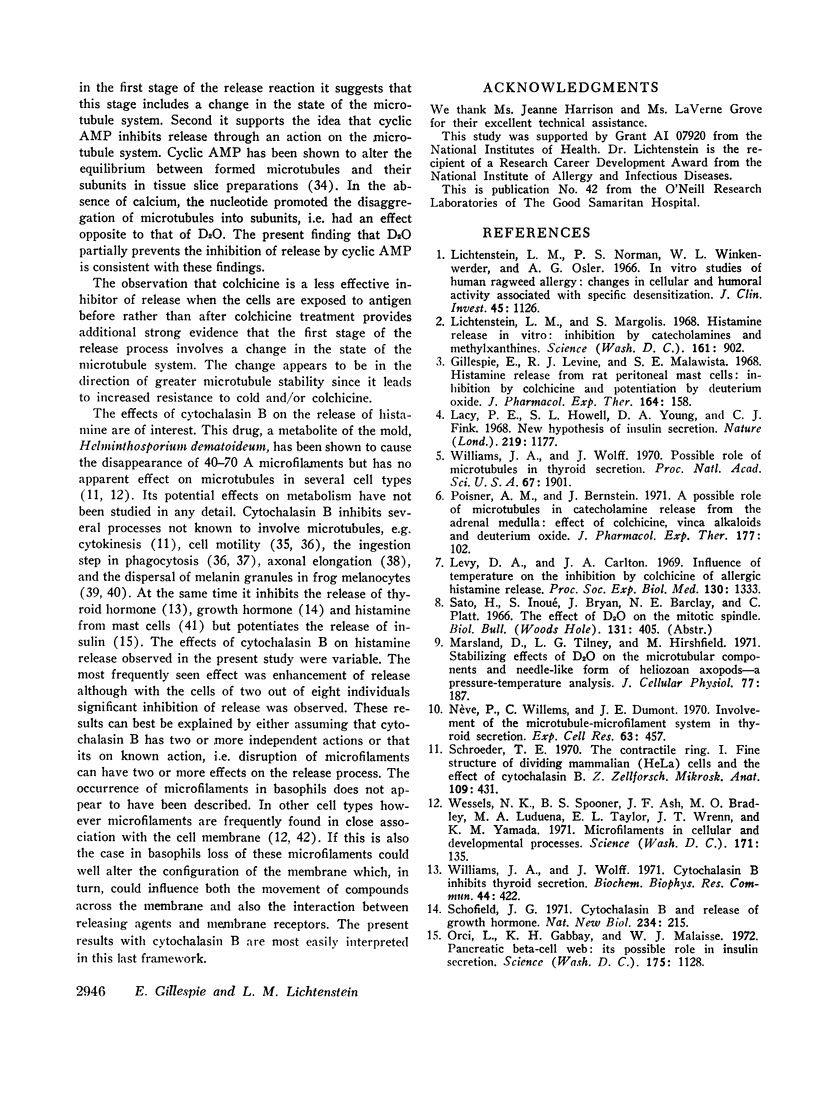

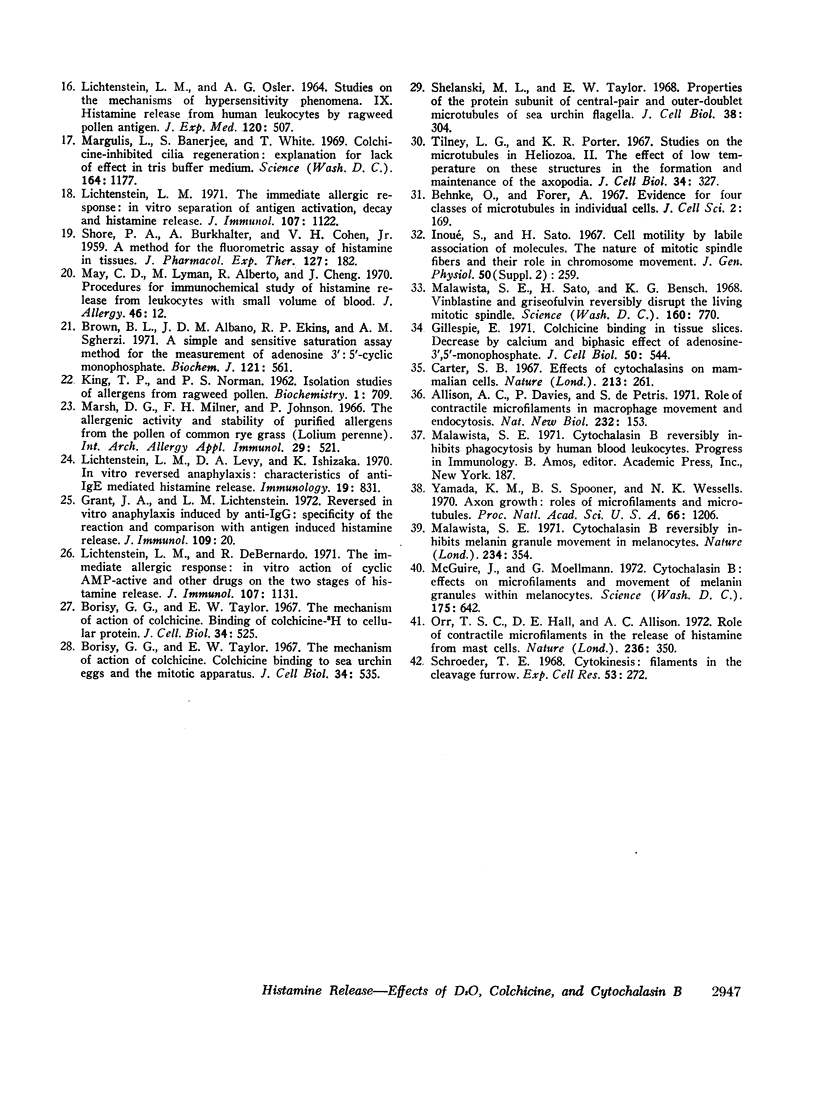

Agents known to interact with either microtubules or microfilaments influenced the antigen-induced release of histamine from the leukocytes of allergic individuals. Deuterium oxide (D2O) which stabilizes microtubules and thereby favors their formation enhanced histamine release markedly. Concentrations as low as 5% increased antigen-induced release somewhat while concentrations as high as 75% had no effect on release in the absence of antigen. Enhancement occurred over a wide range of antigen concentrations and was also seen when release was initiated by antibody to IgE or IgG. When the release process was divided into two stages a D2O activity could be demonstrated only in the second stage. However, when D2O was present in the first stage together with agents which raise cyclic AMP levels and thereby inhibit release it partially reversed this inhibition. Colchicine, demecolcine, and vinblastine, compounds known to disaggregate microtubules, i.e., have an effect opposite to that of D2O, inhibited the release of histamine and counteracted the effects of D2O. The inhibitory action of colchicine was greater if cells were treated with colchicine before rather than after activation with antigen. Cytochalasin B, a compound which causes the disappearance of microfilaments, had variable effects on histamine release. The most frequently seen response was slight enhancement. Neither D2O nor cytochalasin B altered cyclic AMP levels in leukocytes. These observations support and strengthen the view that an intact and functioning microtubule system is directly important for the secretion of histamine from leukocytes and suggest that microfilaments might have multiple indirect effects.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Allison A. C., Davies P., De Petris S. Role of contractile microfilaments in macrophage movement and endocytosis. Nat New Biol. 1971 Aug 4;232(31):153–155. doi: 10.1038/newbio232153a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behnke O., Forer A. Evidence for four classes of microtubules in individual cells. J Cell Sci. 1967 Jun;2(2):169–192. doi: 10.1242/jcs.2.2.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borisy G. G., Taylor E. W. The mechanism of action of colchicine. Binding of colchincine-3H to cellular protein. J Cell Biol. 1967 Aug;34(2):525–533. doi: 10.1083/jcb.34.2.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borisy G. G., Taylor E. W. The mechanism of action of colchicine. Colchicine binding to sea urchin eggs and the mitotic apparatus. J Cell Biol. 1967 Aug;34(2):535–548. doi: 10.1083/jcb.34.2.535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown B. L., Albano J. D., Ekins R. P., Sgherzi A. M. A simple and sensitive saturation assay method for the measurement of adenosine 3':5'-cyclic monophosphate. Biochem J. 1971 Feb;121(3):561–562. doi: 10.1042/bj1210561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter S. B. Effects of cytochalasins on mammalian cells. Nature. 1967 Jan 21;213(5073):261–264. doi: 10.1038/213261a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie E. Colchicine binding in tissue slices. Decrease by calcium and biphasic effect of adenosine-3', 5'-monophosphate. J Cell Biol. 1971 Aug;50(2):544–549. doi: 10.1083/jcb.50.2.544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie E., Levine R. J., Malawista S. E. Histamine release from rat peritoneal mast cells: inhibition by colchicine and potentiation by deuterium oxide. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1968 Nov;164(1):158–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant J. A., Lichtenstein L. M. Reversed in vitro anaphylaxis induced by anti-IgG: specificity of the reaction and comparison with antigen-induced histamine release. J Immunol. 1972 Jul;109(1):20–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoué S., Sato H. Cell motility by labile association of molecules. The nature of mitotic spindle fibers and their role in chromosome movement. J Gen Physiol. 1967 Jul;50(6 Suppl):259–292. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KING T. P., NORMAN P. S. Isolation studies of allergens from regweed pollen. Biochemistry. 1962 Jul;1:709–720. doi: 10.1021/bi00910a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LICHTENSTEIN L. M., OSLER A. G. STUDIES ON THE MECHANISMS OF HYPERSENSITIVITY PHENOMENA. IX. HISTAMINE RELEASE FROM HUMAN LEUKOCYTES BY RAGWEED POLLEN ANTIGEN. J Exp Med. 1964 Oct 1;120:507–530. doi: 10.1084/jem.120.4.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacy P. E., Howell S. L., Young D. A., Fink C. J. New hypothesis of insulin secretion. Nature. 1968 Sep 14;219(5159):1177–1179. doi: 10.1038/2191177a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy D. A., Carlton J. A. Influence of temperature on the inhibition by colchicine of allergic histamine release. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1969 Apr;130(4):1333–1336. doi: 10.3181/00379727-130-33786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein L. M., DeBernardo R. The immediate allergic response: in vitro action of cyclic AMP-active and other drugs on the two stages of histamine release. J Immunol. 1971 Oct;107(4):1131–1136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein L. M., Levy D. A., Ishizaka K. In vitro reversed anaphylaxis: characteristics of anti-IgE mediated histamine release. Immunology. 1970 Nov;19(5):831–842. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein L. M., Margolis S. Histamine release in vitro: inhibition by catecholamines and methylxanthines. Science. 1968 Aug 30;161(3844):902–903. doi: 10.1126/science.161.3844.902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein L. M., Norman P. S., Winkenwerder W. L., Osler A. G. In vitro studies of human ragweed allergy: changes in cellular and humoral activity associated with specific desensitization. J Clin Invest. 1966 Jul;45(7):1126–1136. doi: 10.1172/JCI105419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein L. M. The immediate allergic response: in vitro separation of antigen activation, decay and histamine release. J Immunol. 1971 Oct;107(4):1122–1130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malawista S. E. Cytochalasin B reversibly inhibits melanin granule movement in melanocytes. Nature. 1971 Dec 10;234(5328):354–355. doi: 10.1038/234354a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malawista S. E., Sato H., Bensch K. G. Vinblastine and griseofulvin reversibly disrupt the living mitotic spindle. Science. 1968 May 17;160(3829):770–772. doi: 10.1126/science.160.3829.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margulis L., Banerjee S., White T. Colchicine-inhibited cilia regeneration: explanation for lack of effect in tris buffer medium. Science. 1969 Jun 6;164(3884):1177–1178. doi: 10.1126/science.164.3884.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh D. G., Milner F. H., Johnson P. The allergenic activity and stability of purified allergens from the pollen of common rye grass (lolium perenne). Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1966;29(6):521–535. doi: 10.1159/000229739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsland D., Tilney L. G., Hirshfield M. Stabilizing effects of D2O on the microtubular components and needle-like form of heliozoan axopods: a pressure-temperature analysis. J Cell Physiol. 1971 Apr;77(2):187–194. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1040770209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May C. D., Lyman M., Alberto R., Cheng J. Procedures for immunochemical study of histamine release from leukocytes with small volume of blood. J Allergy. 1970 Jul;46(1):12–20. doi: 10.1016/0021-8707(70)90056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire J., Moellmann G. Cytochalasin B: effects on microfilaments and movement of melanin granules within melanocytes. Science. 1972 Feb 11;175(4022):642–644. doi: 10.1126/science.175.4022.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nève P., Willems C., Dumont J. E. Involvement of the microtubule-microfilament system in thyroid secretion. Exp Cell Res. 1970 Dec;63(2):457–460. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(70)90238-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orci L., Gabbay K. H., Malaisse W. J. Pancreatic beta-cell web: its possible role in insulin secretion. Science. 1972 Mar 10;175(4026):1128–1130. doi: 10.1126/science.175.4026.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr T. S., Hall D. E., Allison A. C. Role of contractile microfilaments in the release of histamine from mast cells. Nature. 1972 Apr 14;236(5346):350–351. doi: 10.1038/236350a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poisner A. M., Bernstein J. A possible role of microtubules in catecholamine release from the adrenal medulla: effect of colchicine, vinca alkaloids and deuterium oxide. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1971 Apr;177(1):102–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHORE P. A., BURKHALTER A., COHN V. H., Jr A method for the fluorometric assay of histamine in tissues. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1959 Nov;127:182–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield J. G. Cytochalasin B and release of growth hormone. Nat New Biol. 1971 Sep 15;234(50):215–216. doi: 10.1038/newbio234215a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder T. E. Cytokinesis: filaments in the cleavage furrow. Exp Cell Res. 1968 Oct;53(1):272–276. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(68)90373-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder T. E. The contractile ring. I. Fine structure of dividing mammalian (HeLa) cells and the effects of cytochalasin B. Z Zellforsch Mikrosk Anat. 1970;109(4):431–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelanski M. L., Taylor E. W. Properties of the protein subunit of central-pair and outer-doublet microtubules of sea urchin flagella. J Cell Biol. 1968 Aug;38(2):304–315. doi: 10.1083/jcb.38.2.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilney L. G., Porter K. R. Studies on the microtubules in heliozoa. II. The effect of low temperature on these structures in the formation and maintenance of the axopodia. J Cell Biol. 1967 Jul;34(1):327–343. doi: 10.1083/jcb.34.1.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessells N. K., Spooner B. S., Ash J. F., Bradley M. O., Luduena M. A., Taylor E. L., Wrenn J. T., Yamada K. Microfilaments in cellular and developmental processes. Science. 1971 Jan 15;171(3967):135–143. doi: 10.1126/science.171.3967.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J. A., Wolff J. Cytochalasin B inhibits thyroid secretion. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1971 Jul 16;44(2):422–425. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(71)90617-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J. A., Wolff J. Possible role of microtubules in thyroid secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1970 Dec;67(4):1901–1908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.67.4.1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K. M., Spooner B. S., Wessells N. K. Axon growth: roles of microfilaments and microtubules. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1970 Aug;66(4):1206–1212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.66.4.1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]