Abstract

Substantial resources are invested in psychological support for children orphaned or otherwise made vulnerable in the context of HIV/AIDS (OVC). However, there is still only limited scientific evidence for greater psychological distress amongst orphans and even less evidence for the effectiveness of current support strategies. Furthermore, programmes that address established mechanisms through which orphanhood can lead to greater psychological distress should be more effective. We use quantitative and qualitative data from Eastern Zimbabwe to measure the effects of orphanhood on psychological distress and to test mechanisms for greater distress amongst orphans suggested in a recently published theoretical framework.

Orphans were found to suffer greater psychological distress than non-orphans (sex- and age-adjusted co-efficient: 0.15; 95% CI 0.03–0.26; P = 0.013). Effects of orphanhood contributing to their increased levels of distress included trauma, being out-of-school, being cared for by a non-parent, inadequate care, child labour, physical abuse, and stigma and discrimination. Increased mobility and separation from siblings did not contribute to greater psychological distress in this study. Over 40% of orphaned children in the sample lived in households receiving external assistance. However, receipt of assistance was not associated with reduced psychological distress.

These findings and the ideas put forward by children and caregivers in the focus group discussions suggest that community-based programmes that aim to improve caregiver selection, increase support for caregivers, and provide training in parenting responsibilities and skills might help to reduce psychological distress. These programmes should be under-pinned by further efforts to reduce poverty, increase school attendance and support out-of-school youth.

Keywords: OVC, psychological distress, Zimbabwe, theoretical framework, determinants

Introduction

HIV is causing enormous increases in adult mortality and orphanhood in sub-Saharan African countries with generalised epidemics (Barnett & Whiteside, 2002; Watts, Lopman, Nyamukapa, & Gregson, 2005). There is great concern, therefore, for the psychological well-being of children orphaned or otherwise made vulnerable in the context of HIV/AIDS (OVC) (Barbarin & Richter, 2007; Barnett & Blaikie, 1992) and substantial funds are being channelled into programmes of psychological support (Horizons Report, 2005; UNAIDS&UNICEF, 2004).

There is increasing scientific evidence that OVC, in general, suffer increased psychological distress in sub-Saharan African settings (Atwine, Cantor-Graae, & Banjunirwe, 2005; Basaza & Kaija, 2002; Chatterji et al., 2005; Cluver & Gardner, 2007; Foster, Makufa, Drew, & Kralovec, 1997; Makame, Ani, & Grantham-McGregor, 2002; Nampanya-Serpell, 2000; Oburu, 2004). However, less is known about the consequences of psychological distress in these contexts and understanding about the effectiveness of interventions remains limited (King, De Silva, Stein, & Patel, 2009). There is growing recognition that not all OVC require external interventions (Evans, 2005; Masten, 2001; Nyamukapa et al., 2008), and that, in some instances, inappropriately targeted interventions can be harmful (Neimeyer, 2000) and may undermine resilience acquired through effective responses to adversity including access to community support (Summerfield, 2004). Therefore, a better understanding is needed of the characteristics and circumstances of children who require support (i.e., moderating factors) as well as the factors that lie on the causal pathway between orphanhood and psychological distress (i.e., mediating factors) (Cluver & Gardner, 2007; Nyamukapa et al., 2008).

In this paper, we address this gap in understanding through an in-depth study conducted in Manicaland, Eastern Zimbabwe. We use detailed quantitative and qualitative data to test a recently published theoretical framework describing factors that moderate and mediate psychological distress amongst OVC (Nyamukapa et al., 2008) and to describe local perceptions on how these factors might be addressed.

Methods

Theoretical framework

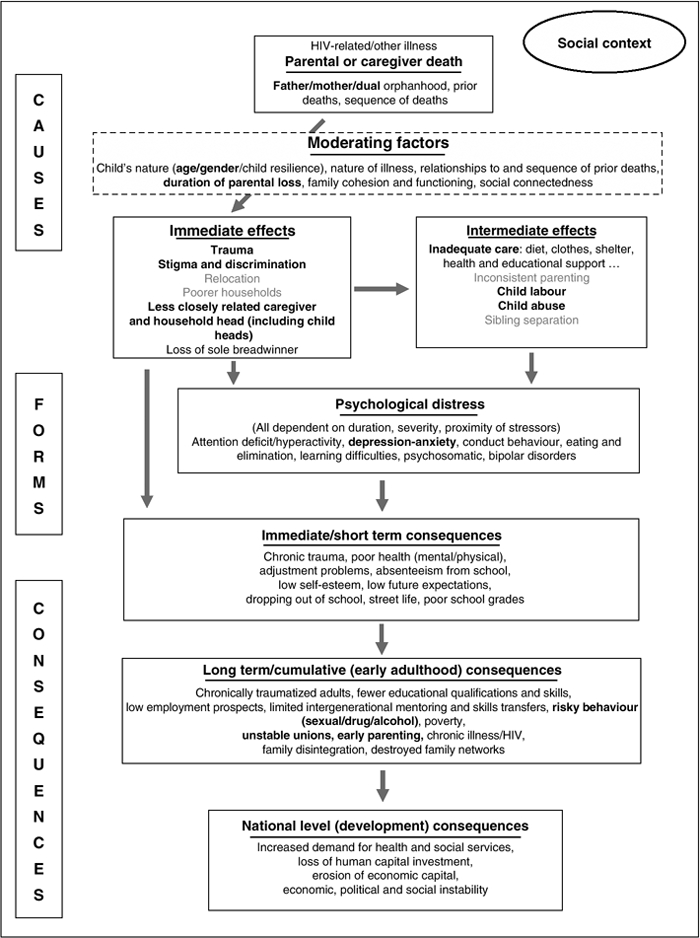

The theoretical framework used in the study is shown in Figure 1. A full description of the framework and its derivation has been published (Nyamukapa et al., 2008). In brief, the effect of orphanhood on psychological distress depends on the social context. Within a given social context, children may be more or less likely to suffer from psychological distress (or to develop resilience) depending on “moderating” factors such as their sex, age, nature, social background, and form and timing of parental loss. Orphanhood can result in immediate, possibly short-term, effects (e.g., trauma) as well as intermediate effects that develop over time and have a more gradual effect on psychological well-being (e.g., poor clothing). These “mediating” factors can cause psychological distress and are more common in orphaned children. Psychological distress, in turn, can have a number of consequences including a greater propensity to engage in risky sexual behaviour.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework on the causes and consequences of psychological distress amongst orphans in the context of a large-scale HIV/AIDS epidemic.

Note: Adapted from Nyamukapa et al. (2008). Bold type indicates effects for which evidence was found in the study. Grey type indicates effects tested in the study for which no evidence was found. Standard type indicates effects not tested in the current study.

A number of different forms of psychological distress can result from losing a parent or caregiver. However, in the current study, we focus on depression and anxiety.

Quantitative data

A sample of 1469 children aged 0–18 years, stratified to give roughly equal numbers of paternal, maternal and double orphans and non-orphans, was drawn at random from the second round of a phased household survey in eight rural locations in Manicaland province, Eastern Zimbabwe between February 2002 and March 2003. One thousand and three (68.3%) of these children were traced and agreed to be interviewed approximately one year later in each location (December 2002 to March 2004). Interviews were conducted by qualified social workers and questions on psychological distress were asked to 551 children aged 12–18 years (272 male and 279 female); 527 (96%) children provided complete data – 185 double orphans, 109 maternal orphans, 150 paternal orphans and 83 non-orphans. The questions were adapted from the World Health Organisation Self-Report Questionnaire on depression and anxiety which has been validated in Zimbabwe and 12 other African countries (Beusenberg & Orley, 1994).

A psychological distress variable was constructed using factor analysis. Because the factor analysis suggested a single factor solution without great variability on factor loadings, an outcome score was created by summing all variables with factor loadings ≥0.3. Seventeen items with factor loadings of ≥0.3 were obtained from the 20 questions asked to children relating to psychological distress (Table 1). Based on these 17 items, the Cronbach alpha reliability coefficient was 0.73.

Table 1.

Psychological distress variable items factor-loading results: children's responses (12–18 years olds).

| Question items | Factor loadings | |

| 1. | Do you cry more than usual? | 0.55 |

| 2. | Do you feel tense, nervous or worried? | 0.54 |

| 3. | Do you feel tired all the time? | 0.54 |

| 4. | Do you have uncomfortable feelings in your stomach? | 0.48 |

| 5. | Do you find it difficult to make decisions? | 0.47 |

| 6. | Is your appetite poor? | 0.46 |

| 7. | Do you feel more unhappy than usual? | 0.45 |

| 8. | Do you feel a worthless person? | 0.44 |

| 9. | Do your hands shake? | 0.43 |

| 10. | Do you sleep badly? | 0.43 |

| 11. | Is your digestion poor? | 0.40 |

| 12. | Are you easily frightened? | 0.40 |

| 13. | Do you get tired easily? | 0.39 |

| 14. | Do you have trouble thinking clearly? | 0.38 |

| 15. | Do find it difficult to enjoy your daily activities? | 0.37 |

| 16. | Has the thought of ending your life been in your mind? | 0.31 |

| 17. | Do you often have headaches? | 0.31 |

| Question items with <0.3 factor loadings: not used | ||

| 18. | Is your daily work suffering? | |

| 19. | Are you able to play a useful part in life? | |

| 20. | Have you lost interest in things? | |

Dichotomous variables were created for each moderating factor and immediate and intermediate effect of orphanhood. Moderating factors investigated were sex, age (12–15 years versus ≥16 years), form of orphanhood (double, maternal and paternal) and duration of parental loss (0–1 year, 2–4 years, 5–17 years, and ≥18 years). Immediate effects of orphanhood investigated were trauma from living in a household with a death in the last three years or a sick adult member, stigma and discrimination (being treated worse than other children in the household), frequent residence changes (> 1 move) and residence in a poorer household (poorest quintile of households based on ownership of assets). Intermediate effects examined were care by a less closely related caregiver (non-parent), inadequate provision of basic needs (health care, school fees and clothing by carer), inconsistent parenting (> 1 change), child labour (waged labour outside the household or >20 hours work per week on the family land), physical abuse (beaten by an adult household member in the last month), living apart from siblings and not being enrolled in school. The effect of external support (targeted to the household or direct to the OVC) was investigated as a possible mitigating factor for the effect of orphanhood on psychological distress.

Finally, possible consequences of psychological distress were assessed using two variables describing risk behaviours for the 280 children aged 15 years and over – commencement of sexual activity and substance abuse (alcohol and other drugs).

The psychological distress scores were “count” data and were therefore modelled using poisson regression. Psychological distress scores were compared for orphans versus non-orphans and the possible moderating effects of sex and age on the relationship between orphanhood and psychological distress were evaluated. Multivariate models were developed to: (a) measure associations between the hypothesised moderating and mediating factors and psychological distress; and (b) establish whether increased exposure to these determinants accounted for the greater psychological distress observed in orphaned children. Logistic regression was used to investigate associations between psychological distress and risky behaviours controlling for sex and age.

Qualitative methods

Qualitative investigations were conducted to identify locally acceptable intervention strategies that addressed the mediating factors associated with psychological distress. Thirteen focus group discussions (FGDs) were held with children (n = 4) and caregivers (n = 4), local community members (n = 2), adults orphaned during childhood (n = 2) and survey interviewers (n = 1). Village community workers recruited 8–13 participants for each FGD with roughly equal numbers of males and females. The FGDs were held within the community and were facilitated by CN with help from another qualified social worker. The discussions were held in the local language (Shona) and were recorded on tape and flipcharts. The topics covered in the FGDs included the local understandings of psychological distress, the relevance and suitability of the study methods, the evolution and adequacy of the extended family orphan care system, and measures that might reduce children's psychological distress. Only findings on the last of these topics are presented in this paper.

The data were translated from Shona into English and analysed manually (by CN) using content theme analysis. This involved coding recurring themes and interpreting the coded data. Reports from the different groups were compared and differences and similarities were noted.

The study was approved by the St. Mary's Research Ethics Committee (reference number: 04/Q0403/130), the Biomedical Research and Training Institute (reference number AP65/05), and the Medical Research Council of Zimbabwe (reference number MRCZ/A/990).

Results

Associations between orphanhood and psychological distress

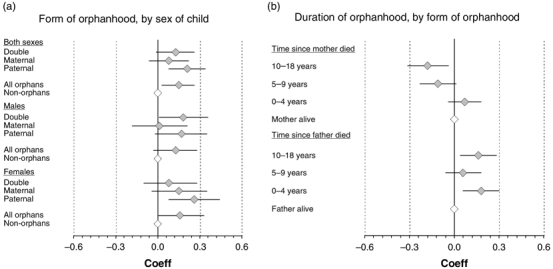

Girls reported more psychological distress than boys (Coeff: 0.22; 95% CI 0.15–0.31). Older children reported less psychological distress than younger children, but the difference was only statistically significant for boys (Coeff: −0.27; 95% CI−0.50-− 0.05). After controlling for sex and age, orphans showed greater psychological distress than non-orphans (Coeff: 0.15; 95% CI 0.03–0.26; P = 0.013) (Figure 2a). This was also true for girls and boys separately. For girls, the heightened psychological distress was most evident in paternal orphans. In boys, paternal and double orphans were worst affected.

Figure 2.

Associations between orphanhood and psychological distress by sex and form and duration of orphanhood. (a) Form of orphanhood, by sex of child. (b) Duration of orphanhood, by form of orphanhood.

For paternal orphans, greater psychological distress was seen for all durations of parental loss (Figure 2b). Maternal orphans who lost their parents >4 years ago reported less psychological distress than those whose mothers were still alive, suggesting high levels of resilience.

Causal pathways between orphanhood and psychological distress

The frequencies of experiencing the effects of orphanhood hypothesised to lie on the causal pathway between orphanhood and greater psychological are shown in Table 2, for all children in the study sample. All categories of orphan were more likely than non-orphans to live in households with a recent death (69% for all orphans vs. 5% for non-orphans; P<0.001) and to be cared for by a non-parent (61% vs. 19%; P<0.001). Paternal orphans were the most likely to live with a seriously ill household member (57%) and to experience child labour (36%). Maternal orphans were five times more likely to experience stigma than non-orphans (10% vs. 2%; P = 0.05). More maternal and double orphans than non-orphans had experienced relocation (14% and 14% vs. 4%; P<0.05), changes in caregiver (23% and 28% vs. 4%; P<0.01), and separation from siblings (25% and 24% vs. 12%; P <0.05). Residence in a poorer household and child abuse were equally common in the orphan and non-orphan groups (P >0.05).

Table 2.

Hypothesised determinants and observed effects on psychological distress in 527 children aged 12–18 years.

| Effect on psychosocial distress |

||||||

| Test for difference |

||||||

| Effects of orphanhood | Information source | Number | Percentage (%) | Coeff | 95% CI | P-value |

| Immediate effects | ||||||

| Trauma - death in household | Caregiver | 312 | 59 | 0.10 | 0.02–0.18 | 0.014 |

| Trauma - illness in household | Caregiver | 266 | 50 | 0.10 | 0.03–0.18 | 0.010 |

| Stigma and discrimination | Child | 29 | 6 | 0.41 | 0.27–0.56 | <0.001 |

| Relocation | Child and caregiver | 56 | 11 | 0.10 | − 0.03–0.22 | 0.121 |

| Residence in poorest quintile of households | Caregiver | 178 | 34 | 0.00 | − 0.08–0.08 | 0.988 |

| Less closely related caregiver (non-parent) | Child and caregiver | 360 | 68 | 0.04 | − 0.04–0.12 | 0.327 |

| Intermediate effects | ||||||

| Inadequate care | Child and caregiver | 417 | 79 | 0.24 | 0.14–0.35 | <0.001 |

| Not enrolled in school | Child | 76 | 14 | 0.26 | 0.14–0.38 | <0.001 |

| Inconsistent parenting | Child and caregiver | 86 | 16 | − 0.02 | − 0.12–0.09 | 0.774 |

| Child labour | Child | 172 | 33 | 0.19 | 0.10–0.27 | <0.001 |

| Physical abuse | Child | 75 | 14 | 0.27 | 0.17–0.38 | <0.001 |

| Sibling separation | Caregiver | 102 | 19 | − 0.08 | − 0.19–0.02 | 0.114 |

| Mitigating factors | ||||||

| Household received external support | Caregiver | 196 | 37 | 0.03 | − 0.05–0.11 | 0.498 |

Tests for associations between immediate and intermediate effects of orphanhood and psychological distress showed strong positive associations for: (a) living in a household with a recent death; (b) living in a household with a seriously ill adult member; (c) suffering stigma; (d) inadequate care; (e) child labour; (f) physical abuse; and (g) being out of school (Table 2). Multiple changes in residence and care-giver, residence in a poorer household, care by a non-parent and sibling separation were not associated with greater psychological distress.

In the multivariate models of orphanhood and psychological distress, the effects of orphanhood (overall) and double orphanhood seen in the sex- and age-adjusted models became non-significant after controlling for the effects of orphanhood, suggesting that these factors do lie on the causal pathway (Table 3). For paternal orphans, the effect of orphanhood weakened but remained borderline statistically significant. Trauma, stigma, inadequate care, child labour, child abuse and being out of school contributed to orphans’ greater psychological distress.

Table 3.

Multivariate Poisson regression tests for experiences on the causal pathway between orphanhood and psychological distress, by form of orphanhood, in children aged 12–18 years.

| Orphans (444) |

Double orphans (185) |

Maternal orphans (109) |

Paternal orphans (150) |

|||||

| Test for difference |

Test for difference |

Test for difference |

Test for difference |

|||||

| Model/effects of orphanhood | Coeff | P-value | Coeff | P-value | Coeff | P-value | Coeff | P-value |

| Sex- and age-adjusted model | 0.15 | 0.013 | 0.13 | 0.040 | 0.08 | 0.245 | 0.21 | 0.001 |

| Full multivariate model | 0.07 | 0.339 | -0.04 | 0.712 | -0.02 | 0.873 | 0.17 | 0.044 |

| Immediate effects | ||||||||

| Trauma – death in household | 0.10 | 0.040 | 0.11 | 0.214 | 0.17 | 0.063 | 0.02 | 0.767 |

| Trauma – illness in household | 0.09 | 0.028 | 0.08 | 0.157 | -0.02 | 0.837 | 0.22 | 0.001 |

| Stigma and discrimination | 0.26 | <0.001 | 0.23 | 0.066 | 0.42 | 0.001 | 0.31 | 0.027 |

| Relocation | 0.10 | 0.151 | 0.14 | 0.167 | 0.17 | 0.192 | -0.07 | 0.636 |

| Residence in poorest quintile of households | -0.08 | 0.090 | -0.01 | 0.928 | -0.20 | 0.011 | -0.05 | 0.432 |

| Less closely related caregiver (non-parent) | 0.09 | 0.046 | - | - | 0.02 | 0.842 | 0.11 | 0.137 |

| Intermediate effects | ||||||||

| Inadequate care | 0.19 | 0.001 | 0.23 | 0.007 | 0.30 | 0.001 | 0.14 | 0.110 |

| Not enrolled in school | 0.17 | 0.009 | 0.24 | 0.009 | -0.03 | 0.808 | 0.16 | 0.089 |

| Inconsistent parenting | -0.03 | 0.611 | -0.08 | 0.249 | 0.11 | 0.345 | 0.19 | 0.207 |

| Child labour | 0.13 | 0.006 | 0.16 | 0.015 | 0.14 | 0.122 | 0.13 | 0.061 |

| Physical abuse | 0.21 | <0.001 | 0.20 | 0.010 | 0.22 | 0.026 | 0.34 | <0.001 |

| Sibling separation | -0.11 | 0.044 | 0.00 | 0.963 | -0.24 | 0.018 | -0.04 | 0.711 |

| Mitigating factors | ||||||||

| Household received external support | 0.00 | 0.994 | 0.16 | 0.017 | -0.13 | 0.140 | 0.17 | 0.044 |

Note: Bold values signify statistically significant at p <0.1 level.

Double (45%), maternal (41%) and paternal (40%) orphans were all more likely than non-orphans (12%) to live in households that received external support (PB0.001). However, whilst residence in a household receiving support had a (non-significant) protective effect against psychological distress for maternal orphans, this was associated with higher distress amongst double and paternal orphans and had no effect for orphans overall (Table 3).

Consequences of psychological distress for early sexual risk behaviour and substance abuse in adolescence

Relatively few children in the study had started sex (8%) or taken alcohol or other drugs (7%). Psychological distress is a standardised variable (Mean (M) = 0, Standard deviation (SD) = 1) so the odds ratios in this analysis can be interpreted as increased odds of engaging in risk behaviour associated with a 1 SD increase in psychological distress. Psychological distress was not associated with having engaged in sex (OR: 1.05, 95% CI 0.88–1.26; P = 0.5) or having drunk alcohol or smoked cigarettes (OR: 1.16, 0.97–1.39; P = 0.1).

Measures to reduce children's psychological distress (qualitative research findings)

Most of the factors associated with psychological distress in the survey data related to the nature and quality of care. In the qualitative data, concerns were frequently expressed about the characteristics of caregivers and it was suggested that more careful selection of caregivers might help to address these problems.

A carer should be someone who volunteers …They should be sociable, not mean, and able to guide the child morally and provide food and clothes. Ideally, they should be a relative but …they could be anybody with these qualities. Even among relatives, some do and some do not. Those who don't will ill-treat orphans by giving them hard chores or chores that are inappropriate for their age, refuse them food, or fail to send them to school or to buy them good clothes. Only those who can treat orphans well …and do things that help the child forget the pain of the loss should take in children. (Children's focus group discussion (mixed OVC and non-OVC), subsistence farming area)

Adults agreed with these suggestions and, generally, grandparents were preferred as caregivers for orphaned children because of their maturity, wisdom in understanding children's emotional needs, experience with raising children, and fewer responsibilities. There was less agreement, however, about whether children themselves should be involved in selecting their caregivers.

The qualitative data also suggested that more support for caregivers might (indirectly) reduce orphans’ psychological distress. Often, caregivers had also suffered the loss of close relatives and their own grief sometimes caused them to be withdrawn, irritable and insensitive.

…They (caregivers) need to be trained on childcare issues to prevent them from ill-treating children in their care. They too are grieving and, like us, need help. They should get somebody to sit down with them and comfort them …to help them understand the consequences of their loss …and the implications of their being emotionally drained on the children they are looking after …(Female, paternal orphan, aged 16 years, Children's focus group discussion, forestry estate)

Regular school attendance was seen as another way of minimising orphans’ psychological distress. Orphaned children viewed school as a safe haven for acquiring life skills (including handling emotional problems), for grieving (through sharing experiences with others in similar situations) and for creating social networks. The school environment offered children time to be children.

If we don't go to school, we miss the chance to learn a lot of knowledge about life and skills. You may not be good in school but just being in school opens your mind to a lot of things like how to make use of available resources (e.g., agriculture) and how to solve problems. Bible teaching and teacher instructions help to mould behaviour and give direction. (Male, paternal orphan, aged 17 years, Children's focus group discussion, subsistence farming area)

Discussion

As in a number of studies now in sub-Saharan Africa, we found associations between orphanhood and psychological distress in populations in eastern Zimbabwe where HIV prevalence in adults exceeds 20% (Gregson et al., 2006) and orphan levels continue to rise (Watts, Lopman, Nyamukapa, & Gregson, 2005). However, unlike in a larger national study in Zimbabwe (Nyamukapa et al., 2008), we did not find evidence that greater psychological distress might contribute to the earlier sexual risk behaviour reported for orphans in this population (Gregson et al., 2005) and elsewhere (Birdthistle et al., 2008; Kang, Dunbar, Laver, & Padian, 2008; Thurman, Brown, Richter, Maharaj, & Magnani, 2006).

On average, boys and girls experiencing all forms of orphanhood had higher levels of psychological distress than their non-orphaned counterparts. However, a substantial minority of orphans did not exhibit higher than average distress and maternal orphans whose mothers had died more than five years previously tended to have lower levels of psychological distress than non-orphans at any given age. This finding is consistent with suggestions that orphaned children may acquire resilience over time (Masten, 2001) although a similar result was not obtained for paternal orphans.

Being out of school was associated with greater psychological distress in childhood and was more common in orphans, as has been found in Zimbabwe nationally (Nyamukapa et al., 2008) and in South Africa (Cluver & Gardner, 2007). Inadequate care, in the form of basic needs not being met, was also associated with greater psychological distress; a finding which is consistent with data from a national survey in Zimbabwe showing a positive association between extreme poverty and psychological distress (Nyamukapa et al., 2008). In addition, being cared for by someone other than a parent, child labour, physical abuse, and (less commonly reported) stigma and discrimination were associated with psychological distress and more common in orphans. After adjusting for these experiences, the statistical associations between orphanhood and psychological distress disappeared or weakened, suggesting that they contribute to the higher levels of distress observed in orphans.

The study is limited by its relatively small sample size and use of cross-sectional data. Associations found in the data, such as those between psychological distress and risky behaviours, may be due to reverse causation. The study relied on self-reports by children; thus, we were unable to investigate psychological distress in children under 12 years of age and the data may be subject to reporting bias. Children –and orphaned children in particular – may tend to under-report (to avoid disclosure of their orphan status) or exaggerate (to obtain assistance) their levels of psychological distress. The study design did not permit investigation of the effects of community level factors that might moderate the effects of orphanhood.

In a study that purposefully oversampled orphans, 37% of children lived in households receiving external OVC support. As in a national survey in Zimbabwe (Nyamukapa et al., 2008), psychological distress in children reached by external support programmes remained high even after adjusting for other factors including extreme poverty. Longitudinal studies are needed to scientifically evaluate the impact of these programmes particularly since they typically target those in greatest need and the benefits of support may take time to show through. However, our findings could also reflect limitations in these programmes. Addressing factors that lie on the causal pathway between orphanhood and psychological distress could increase the effectiveness of these programmes. Many of these factors relate closely to the quality of care for orphaned children and focus group participants in the study suggested that this might be improved by addressing shortcomings in the selection of caregivers and the support made available to them. Thus, specific programmes might include community-based counselling and support for caregivers and courses in parenting skills and responsibilities – which, in turn, could include modules on caregiver selection and support, children's rights (e.g., in relation to child labour, abuse, basic needs and school attendance), and stigma.

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by the World Bank through the Partnership for Child Development.

References

- Atwine B., Cantor-Graae E., Banjunirwe F. Psychological distress among AIDS orphans in rural Uganda. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61:555–564. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbarin O.A., Richter L. Economic status, community danger and psychological problems among South African children. Childhood. 2007;8(1):115–133. doi: 10.1177/0907568201008001007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett T., Blaikie P. AIDS in Africa: Its present and future impact. London: Belhaven Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett T., Whiteside A. AIDS in the 21st century: Disease and globalization. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Basaza R., Kaija D. Chapter 2: The impact of HIV/AIDS on children: Lights and shadows in the “Successful Case” of Uganda. In: Cornia Florence G.A., editor. AIDS, public policy & child well-being. Florence: UNICEF-IRC; 2002. pp. 1–73. [Google Scholar]

- Beusenberg M., Orley J. A user's guide to the self reporting questionnaire (SRQ). Division of Mental Health World Health Organisation. WHO/MNH/PSF/94. 1994;8:1–75. [Google Scholar]

- Birdthistle I., Floyd S., Machingura A., Mudziwapasi N., Gregson S., Glynn J.R. From affected to infected? Orphanhood and HIV risk among female adolescents in urban Zimbabwe. AIDS. 2008;22(6):759–766. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f4cac7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterji M., Dougherty L., Ventimiglia T., Mulenga Y., Jones A., Mukaneza A., et al. The well-being of children affected by HIV/AIDS in Lusaka, Zambia and Gitarama Province, Rwanda: Findings from a study (Community REACHWorking Paper No. 2) Washington, DC: Community REACH Program, Pact; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cluver L., Gardner F. The mental health of children orphaned by AIDS: A review of international and South African Research. Journal of Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2007;19(1):1–7. doi: 10.2989/17280580709486631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans P. Social networks, migration and care in Tanzania-caregivers’ and children's resilience to coping with HIV/AIDS. Journal of Children and Poverty. 2005;11(2):111–129. [Google Scholar]

- Foster G., Makufa C., Drew R., Kralovec E. Factors leading to the establishment of childheaded households: The case of Zimbabwe. Health Transition Review. 1997;7(Suppl. 2):155–168. [Google Scholar]

- Gregson S., Garnett G.P., Nyamukapa C.A., Hallett T.B., Lewis J.J.C., Mason P.R., et al. HIV decline associated with behaviour change in Eastern Zimbabwe. Science. 2006;311:664–666. doi: 10.1126/science.1121054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregson S., Nyamukapa C.A., Garnett G.P., Wambe M., Lewis J.J.C., Mason P.R., et al. HIV infection and reproductive health in teenage women orphaned and made vulnerable by AIDS in eastern Zimbabwe. AIDS Care. 2005;17:785–794. doi: 10.1080/09540120500258029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horizons Report. Horizons Report June 2005: Providing psychological support to AIDS-affected children: Operations research informs programs in Zimbabwe and Rwanda. 2005. Horizons Report: HIV/AIDS Operations Research.

- Kang M., Dunbar M., Laver S., Padian N.S. Maternal versus paternal orphans and HIV/STI risk among adolescent girls in Zimbabwe. AIDS Care. 2008;20:214–217. doi: 10.1080/09540120701534715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King E., De Silva M., Stein A., Patel V. Interventions for improving the psychological well-being of children affected by HIV/AIDS. 2009. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009(2). doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006733.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Makame V., Ani C., Grantham-McGregor S. Psychological well-being of orphans in Dar El Salaam, Tanzania. Acta Paediatrica. 2002;91:455–464. doi: 10.1080/080352502317371724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten A. Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist. 2001;36(3):227–238. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.56.3.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nampanya-Serpell N. Social and economic risk factors for HIV/AIDS-affected families in Zambia. 2000, 7-8 July. AIDS & Economics Symposium, Durban.

- Neimeyer R.A. Searching for the meaning of meaning: Grief therapy and the process of reconstruction. Death Studies. 2000;24:541–558. doi: 10.1080/07481180050121480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyamukapa C., Gregson S., Lopman B., Saito S., Watts H.J., Monasch R., et al. HIV-associated orphanhood and children's psychological distress: Theoretical framework tested with data from Zimbabwe. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(1):133–141. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.116038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oburu P.O. Social adjustment of Kenyan orphaned grandchildren, perceived caregiving stresses and discipline strategies used by their fostering grandparents (Doctoral dissertation) Göteborg, Sweden: Göteborg University; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Summerfield D. Cross cultural perspectives on the medicalisation of human suffering. In: Rosen G., editor. Posttraumatic distress disorder. London: John Wiley; 2004. pp. 233–245. [Google Scholar]

- Thurman T.R., Brown L., Richter L., Maharaj P., Magnani R. Sexual risk behaviour among South African adolescents: Is orphan status a factor? AIDS and Behaviour. 2006;10:627–635. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9104-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS, & UNICEF. A framework for the protection, care and support of orphans and vulnerable children living in a world with HIV and AIDS. New York: UNICEF; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Watts H.J., Lopman B., Nyamukapa C.A., Gregson S. Rising incidence and prevalence of orphanhood in Manicaland, Zimbabwe, 1998 to 2003. AIDS. 2005;19:717–725. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000166095.62187.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]