Abstract

We have previously demonstrated that two wild-derived stocks of mice, Idaho and Majuro, are significantly longer-lived than mice of a control stock (DC) generated as a four-way cross of commonly used laboratory strains of mice. This study provides independent confirmation of this earlier finding, as well as examining serum glucose, insulin, leptin, glycated hemoglobin (GHb), cataract severity, and glucose tolerance levels in each of the stocks. Both the mean (+20%) and maximum (+13%) life span of the Idaho mice were significantly increased relative to the DC stock, while in the Majuro mice only maximum (+15%) life span was significantly increased. In addition, Majuro mice were hyperglycemic in both the fed and fasted states compared both to laboratory-derived and Idaho stocks, had significantly elevated GHb levels and cataract scores, and were glucose intolerant although serum insulin levels did not differ between stocks. Body weight and body mass index (BMI)-corrected leptin levels were also dramatically (1.5–3-fold) higher in the Majuro mice. The longevity of Id mice was not accompanied by changes in serum glucose and insulin levels, or glucose tolerance compared to DC controls, although GHb levels were significantly lower in the Idaho mice. Taken together, these findings suggest that neither a reduction of blood glucose levels nor an increase in glucose tolerance is necessary for life span extension in mice.

Keywords: Hyperglycemia, Glucose tolerance, Glycated hemoglobin, Life span

1. Introduction

We have previously described (Miller et al., 2002) two stocks of wild-derived mice that are significantly longer-lived than a stock of mice (‘DC’) generated as a four-way cross among the common laboratory strains BALB/cJ, C57BL/6J, C3H/HeJ, and DBA/2J. Mice of the Id (‘Idaho’) stock, descendants of mice originally trapped in barnyards in North-Central Idaho (Idaho) showed significantly longer mean (+24%) and maximal (+16%) life span than DC mice. Mice of the Ma (‘Majuro’) stock, derived from progenitors originally live-trapped on the South Pacific island of Majuro, exhibited a modest but statistically significant increase (+9%) in maximum life span. In comparison to the DC stock, both the Idaho and Majuro mice are significantly smaller and exhibit a significant delay in the onset of reproductive maturation, and there are also dramatic differences in insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I), thyroxine (T4), leptin and glycated hemoglobin (GHb) levels among the stocks at 6 months of age. In particular, serum IGF-I levels were lower in both the Idaho and Majuro mice relative to the DC, Majuro mice were hypothyroid while Idaho and DC mice were euththyroid, serum leptin levels were elevated in the DC and Majuro mice relative to the Idaho stock, and GHb levels were highest in Majuro mice, followed by the DC and Idaho stocks, respectively (Miller et al., 2002).

Impaired glucose tolerance, impaired insulin secretion and decreased insulin sensitivity are commonplace with aging (Chang and Halter, 2003; Muzumdar et al., 2004) and have been associated with age-related declines in cardiovascular function (Barrett-Connor and Ferrara, 1998; Rodriguez et al., 1996, 1999), and cognitive decline (Convit et al., 2003) as well as increased cancer risk (Saydah et al., 2003) regardless of diabetic status. These changes in glucose balance are also thought to play a prominent role in the age-related accumulation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and the products of glycoxidation reactions, both of which have been implicated in protein dysfunction and DNA damage (Ulrich and Cerami, 2001).

Caloric restriction (CR), the only known intervention to consistently increase life span in mammals (Weindruch and Walford, 1988), has repeatedly been demonstrated to reduce basal glucose and insulin levels while improving glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity in rodents (Masoro, 2000), dogs (Larson et al., 2003), and non-human primates (Gresl et al., 2003). Although the mechanism(s) underlying these effects remain unknown, alterations in patterns of gene expression for key glucoregulatory pathways (Dhahbi et al., 1999, 2001), tissue specific changes in glucose utilization (Dean et al., 1998; Wetter et al., 1999), depot specific alterations in fat mass (Imbeault et al., 2003), and significant changes in circulating hormone levels, such as leptin (Gabriely et al., 2002a,b), adiponectin (Zhu et al., 2004), and the glucocorticoids (Sabatino et al., 1991) are all thought to contribute in some way to the effect of CR on glucose and insulin balance. Interestingly, in mutant and transgenic models of life span extension in mice a reduction in fasted and non-fasted glucose and insulin levels is usually seen, often in conjunction with normal or improved glucose tolerance and/or high insulin sensitivity (Hauck et al., 2001; Coschigano et al., 2003; Dominici et al., 1999, 2002, 2003; Yamaza et al., 2004). These observations suggest that low basal glucose and insulin levels, a high degree of glucose tolerance and a high degree of insulin sensitivity may play a role in these diverse models of life span regulation.

In this study, we examined insulin and leptin levels, as well as glucose levels, glucose tolerance, cataract severity, and an index of glycemic status (glycated hemoglobin, GHb) in three stocks (DC, Idaho, Majuro) of mice previously shown to exhibit significant differences in life span (Miller et al., 2002). The initial working hypothesis was that the longer-lived stocks (Idaho, Majuro) would have low glucose, insulin and GHb levels, a reduction in the incidence and severity of cataracts, as well as improved glucose tolerance relative to the DC control.

2. Methods

2.1. Mouse stocks and husbandry

The Idaho and Majuro stocks used in this study were derived from wild-caught progenitors as described in (Miller et al., 2000). Wild-caught animals were used to establish the G0 generation in captivity, from which all subsequent generations were then derived as described in (Miller et al., 2002). Mice of the G4 generation were used for the longevity study and were sampled via retro-orbital bleeding at 6 and 14 months for the quantification of non-fasting serum glucose and leptin as well as the level of hemoglobin glycation (GHb). Mice of the G6 generation (10–12 months old at the time of sampling; middle-aged) and G7 (2–4 months old; young) were used for glucose tolerance tests (GTT) as described below. The genetically heterogeneous DC control stock has been described in detail elsewhere (Miller et al., 2002); mice in this stock have equal genetic contributions from laboratory inbred strains BALB/cJ, C57BL/6J, C3H/HeJ, and DBA/2J. DC mice of the G12 generation were used as controls for the longevity study while mice of the G18 (middle aged) and G20 (young) generations were used as controls for the GTT studies. As part of a pilot study 17–20- month-old Idaho and Majuro mice of the G5 generation were tested for GTT as described, although DC mice of similar age were unavailable at the time of assay. Hence 21-month-old UM-HET3 (HET3) mice, the progenitor stock used to generate DC mice as a result of breeding a HET3 male with a HET3 female, were used as age-matched controls for this set of experiments.

2.2. Longevity experiment

Mice were entered into the study in staggered cohorts from litters born between December 2000 and August 2001. Within 2 days of their birth all litters were culled to 4 pups to ensure equal access to maternal milk. The mice were weaned at 21 days of age, and females retained for this study and housed in individual cages in the University of Michigan Cancer Center and Geriatrics Center Building vivarium until April, 2003, when they were transferred to a colony in the Kresge Building due to space constraint. Mice were inspected at least once daily to record the date of death, and they were euthanized if found to be so severely ill that in the opinion of an experienced caretaker they were thought unlikely to survive more than another few days. All mice were fed commercial rodent chow (Lab Diet 5001, PMI Nutrition International, Brentwood, MO) and were provided with tap water ad libitum. Room temperature was maintained at 72±4 °F in both buildings, with 10–15 fresh air changes per hour and a 12:12 h light:dark cycle. To evaluate the health status of the mice, groups of sentinel mice were exposed to spent bedding from the study population on a quarterly basis, and were later evaluated serologically for the presence of specific viral and bacterial pathogens. The animals were also examined for pinworm. A sentinel mouse was found to be infected with pinworm in October, 2001, and all animals in the study were therefore treated first with Ivermectin for 7 days, followed by a 6-week course of fenbendazol. Quarterly tests for pinworm were negative thereafter. In addition, some mice in the vivarium were found in February 2003 to have titers for mouse hepatitis, including mice on one of the three racks housing the animals reported in this study. The mice cannot therefore be considered to have been specific pathogen-free throughout their lives.

The initial study population consisted of 40 DC, 40 Idaho and 41 Majuro mice. Of these, 2 Majuro females were euthanized for humane reasons due to self-inflicted bite wounds and were excluded from the final analyses. As of 27 October 2004, all of the DC mice had died while 6 Idaho and 2 Majuro mice were still alive. These eight surviving mice were included in the final life span analyses and were treated as censored observations.

Beginning at 1 month of age mice were weighed once per month until 4 months, then weighed again at 6, 8, 12, and 15 months. Beginning at 18 months all mice were weighed monthly until the time of their death. At 6 months the total body length (tip of snout to base of tail) of each mouse was determined, and used to estimate the body mass index (BMI) of each mouse at 6, 12, 15, 18, and 24 months whereby BMI=(body weight (g)/body length at 6 months2). At 6 months each mouse was also bled once for the quantification of non-fasting serum glucose, GHb and leptin levels. In the context of another study, each mouse was immunized at the age of 14 months using turkey erythrocytes, and then bled 2 weeks later. Blood from these samples was used for the quantification of GHb and leptin. Mice were also bled again at 18 months for the determination of T cell subset distributions, and were subjected to cataract exams at 18 and 24 months as described below.

All blood samples were collected between 0900 and 1200 h via puncture of the retro-orbital sinus without anesthesia. After collection, samples were transferred to 1.5 mL unheparinized microfuge tubes and allowed to clot for 2–4 h at 4 °C prior to collecting sera for the glucose and leptin assays. Whole blood was used for the determination of total GHb.

2.3. Glucose tolerance testing

Only male mice were used for this part of the study. Mice in the young and middle-aged age groups were virgins while those in the old age group were retired breeders. All mice were housed with 1–4 animals per cage in the University of Michigan Cancer Center and Geriatrics Center Building and were provided with commercial rodent chow (Lab Diet 5001, PMI Nutrition International, Brentwood, MO) and tap water ad libitum. Room temperature was maintained at 74± 4°F, with 10–15 fresh air changes per hour and a 12:12 h light:dark cycle. Monitoring of the infectious status of the colony was as described above, and all tests were negative.

Prior to assessing their glucose tolerance, mice were fasted overnight (18–24 h) prior to receiving a single intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of glucose at a concentration of 2 mg/g of body weight as a 25% D-glucose (Sigma, St Louis, MO) solution. Immediately prior to injection a small volume of blood (~40 μL) was collected from each mouse (Time 0), and additional samples of the same size were withdrawn again at 15, 30, 60, and 180 min after the glucose injection in the young and middle-aged mice, or at 0, 15, 45, 90 and 180 min in the old mice, and tested for glucose and insulin levels (0–60 min only). Integrated areas under the curves (AUC) were calculated for glucose and insulin using the trapezoidal rule. For each experiment approximately equal numbers of individuals per stock (2–4) were injected and sampled in parallel.

2.4. Hormone assays and glycated hemoglobin

Serum glucose levels were quantified in 6.25–12.5 μL of serum using a glucose oxidase based assay system (Procedure No. 510; Sigma Diagnostics, St Louis, MO). All samples were processed in duplicate according to the manufacturer’s instructions at one-half (non-fasting glucose) or one-quarter (GTT) volume except that a linear standard curve (range 25–400 mg/dL) was used to calculate the glucose concentration of the samples using simple linear regression. Samples from approximately equal numbers of individuals per stock were assayed in parallel.

Non-fasting glucose levels were determined in February 2002, while the GTT was performed between June and August 2004. During each time period, two pooled serum controls were run in each assay, and indicated that the mean (±SD) intra-assay coefficients of variation (CV) were 2.85±1.78% (n=6) and 1.78±1.91% (n=5) for February 2002, and June–August 2004, respectively, and that the inter-assay CV was less than 6% for each control during both time periods.

Serum insulin levels were quantified via a solid phase two-site enzyme immunoassay (ALPCO Diagnostics, Windham, NH). Each serum sample (5 μL) was assayed in duplicate according to the manufacturer’s instructions using dilutions up to 1:2 with assay buffer if necessary to achieve adequate sample volume. Unknown sample concentrations were determined using Softmax Pro software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) after fitting a cubic spline regression to the calibration curve as recommended by the assay manufacturer. Pooled serum controls indicated that the mean (±SD) intra-assay coefficient of variation (CV) was 2.56±2.16% (n=6), and the inter-assay CV was approximately 32% for each control. Samples from approximately equal numbers of individuals per stock were assayed in parallel.

Serum leptin levels were quantified via a commercially available double antibody mouse leptin RIA (Linco Research, Inc., St Charles, MO) according to the manufacturer’s instructions except that sample volumes were reduced by a factor of 4. All samples were run in duplicate and were diluted up to 1:5.2 with assay buffer to ensure adequate sample volume. Inclusion of four pooled serum controls indicated that the mean±SEM intra-assay CV was 10.1±4.2% and that the average interassay CV was approximately 19%.

Total GHb was determined in 50 μL of whole blood via affinity chromatography (Procedure 422; Sigma Diagnostics). All samples were processed in duplicate according to the manufacturer’s instructions using the materials provided.

2.5. Assessment of cataract severity

Mice were tested at the ages of 18 and 24 months for lens turbidity using a hand-held slit lamp after pupillary dilation with one drop of a solution of containing equal parts of 1% tropicamide and 2.5% phenylephrine. Turbidity was scored on a scale from 0 (no evidence of cataract) to 4 (severe) for each eye separately, and the mean score from both eyes was used as an index of cataract severity.

2.6. Statistical analyses

The effects of stock, age, and the stock×age interaction on body weight and body mass index (BMI) were evaluated using a multiple regression model. Non-fasting glucose, absolute and relative leptin, GHb levels and cataract scores, as well as mean and maximum life span, were all evaluated by ANOVA followed by the Tukey–Kramer post hoc test. A repeated measures ANOVA followed by the Tukey–Kramer post hoc test was used to evaluate the effect of stock, time, and the stock×time interaction on serum glucose and insulin levels following glucose challenge. Survival curves were constructed using the Kaplan–Meier method, and differences between stocks were evaluated using the log-rank test.

3. Results

3.1. Growth and adiposity

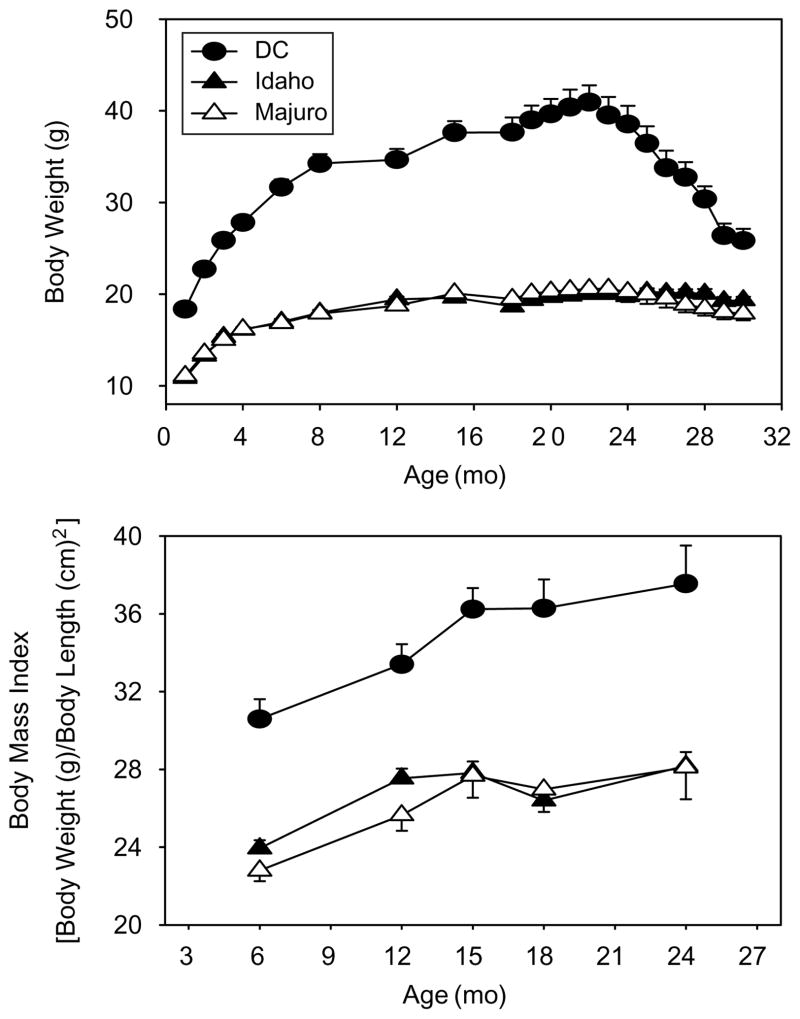

Multiple regression analysis revealed a significant main effect for stock (p<0.0001), age (p<0.0001) and the stock×age interaction (p<0.0001) on body weight. Weight increased with age for all mice, but the DC mice were larger, and grew significantly faster, than both the Idaho and Majuro stocks (Fig. 1, top), consistent with previous studies of these stocks (Miller et al., 2002). Similarly, the mean BMI score was approximately 30% greater in the DC mice versus both the Idaho and Majuro stocks at all ages tested (p<0.001, Fig. 1, bottom), but the rate at which the degree of adiposity, indicated by BMI, increased did not differ between stocks (p=0.14).

Fig. 1.

Weight (top panel) and body mass index (BMI, body panel) as a function of age in wild-derived (Idaho, Majuro) mouse stocks and in a genetically heterogeneous laboratory stock (DC) of mice. Each point represents the mean (±SEM) of each stock. For body weight N=40, 40, and 41 mice at 1 month for the DC, Idaho, and Majuro mice, respectively; due to natural deaths sample sizes decreased with time such that N=7, 21, and 13 at 30 months. For BMI, N=39, 40, and 38 at 6 months and N=24, 31, and 27 at 24 months.

3.2. Longevity experiment

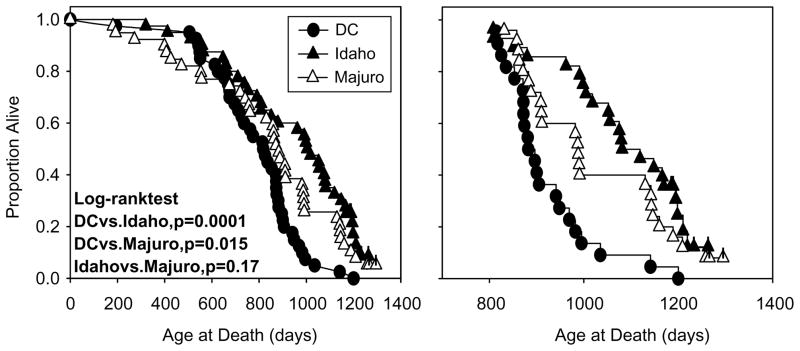

Fig. 2 (left) shows survival curves for each stock of mice, and includes all mice still alive as of 15 October 2004 (0 DC, 7 Idaho, 2 Majuro). As seen previously (Miller et al., 2002), mice of the Idaho stock are long-lived relative to the DC mice (p=0.0001). The Majuro survival curve is significantly different from that for DC mice (p=0.015), but the Majuro mice seem to have higher mortality risks in the first third of the life span and lower risks thereafter, with a crossover point at 800 days with respect to DC mice. A similar trajectory was noted in a separate longevity study of Majuro mice, in which Majuro mice had higher maximal longevity but similar mean and median survival times compared to DC mice (Miller et al., 2002). The right panel of Fig. 2 illustrates survival curves for mice that were alive at 800 days of age. The survival curves for the Idaho and Majuro mice were not significantly different (p=0.17).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for DC, Idaho, and Majuro mice before (left panel) and after (right panel) the removal of individuals that died a natural death before the age of 800 days. Each point represents a single mouse. Statistical significance was calculated by log-rank test, and individual marks on each plot indicate mice that were still alive on 27 October 2004 (censored observations; N=6 Idaho, 2 Majuro).

Table 1 collects summary statistics from these life tables. If all mice of each stock are considered (including the censored observations), the mean lifespan of the Idaho mice is at least 20% greater than the DC mice while the mean life span of the Majuro stock is increased by at least 7%. Median life span is increased by 23 and 7% in the Idaho and Majuro mice, respectively, and maximum lifespan is increased 13–15%. These data are remarkably similar to those obtained in our initial life span study (Miller et al., 2002), and similar to the initial study the Majuro mice also appear to have a higher mortality risk in the first third of the life span and a lower risk thereafter, with a crossover point between 800 and 900 days. Hence, if the mice that died prior to 800 days are removed from the analysis for each stock in this study, the decline in mortality risk in 800-plus old Majuro mice relative to the DC stock becomes more apparent with mean and median life spans increasing to values approximately 11% greater than that in the DC mice. The life tables of the Idaho mice were generally unaffected by deaths prior to 800 days, and removing early deaths from the analysis would have no effect on the estimated maximum life span of any of the stocks.

Table 1.

Mean, median and maximal lifespan of dc, Idaho and Majuro mice

| Stock | N | Mean (±SEM) lifespana | % Different from DC | Median life- span | % Different from DC | Max (±SEM) lifespanb | % Different from DC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All mice | DC | 40 | 787 (±30) | – | 825 | – | 1093 (±47) | – |

| Idaho | 40 | 942 (±41)c | 20 | 1018 | 23 | 1231 (±12)c | 13 | |

| Majuro | 39 | 840 (±49) | 7 | 883 | 7 | 1257 (±18)c | 15 | |

| Mice alive after 800 days | DC | 22 | 923 (±21) | – | 896 | – | ||

| Idaho | 28 | 1084 (±25)c | 17 | 1119 | 25 | |||

| Majuro | 25 | 1036 (±30)c | 12 | 988 | 10 |

All lifespan data are reported in days.

Maximum lifespan was calculated as the mean lifespan of the longest-lived 10% for each stock. Please note this is a minimum estimate for the Idaho mice as more than 10% are currently alive.

Indicates that the value is significantly different from the DC stock at p≤0.05 by one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey–Kramer post hoc test.

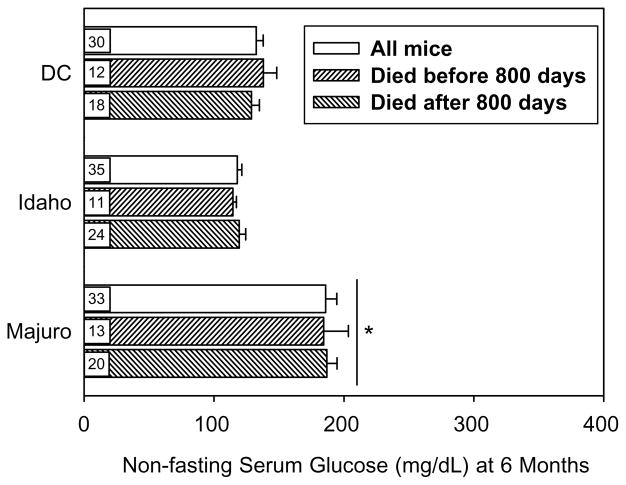

3.3. Serum glucose, glycated hemoglobin and cataract severity

As shown in Fig. 3, mean non-fasting glucose levels in DC and Idaho mice ranged between 120 and 130 mg/dL, but Majuro mice had higher levels (~190 mg/dL) at 6 months of age. One-way ANOVA indicated a significant main effect of stock (p<0.00001), and a post hoc analysis (Tukey-Kramer test) demonstrated that Majuro mice had significantly higher levels than both the DC and Idaho mice (p< 0.01). Importantly, the difference in non-fasting glucose levels was maintained between stocks regardless of whether the calculation involved mice dying prior to 800 days (p< 0.01) or those that died after 800 days (p<0.01). Moreover, the fasting glucose level in a small subset of these mice (n= 4 per stock) at 6 months was (mean±SEM) 170±7, 93± 20, and 118±8 mg/dL, for the Majuro, Idaho and DC mice, respectively. One-way ANOVA indicated the effect of stock was significant (p=0.006), and that the Majuro mice had a significantly higher fasting glucose level than both the Idaho and DC mice (p≤0.04). The difference between DC and Idaho mice was not significant (p=0.4).

Fig. 3.

Mean (±SEM) non-fasting serum glucose levels in 6-month-old DC, Idaho, and Majuro mice. Three sets of values are given for each stock; i.e. prior to removing any individuals based upon age at death (all mice), as well as after removing those individuals that died after or before 800 days of age. Numbers in boxes indicate sample sizes. (*) indicates a significance difference for Majuro versus DC and Idaho mice at p<0.01 for each comparison.

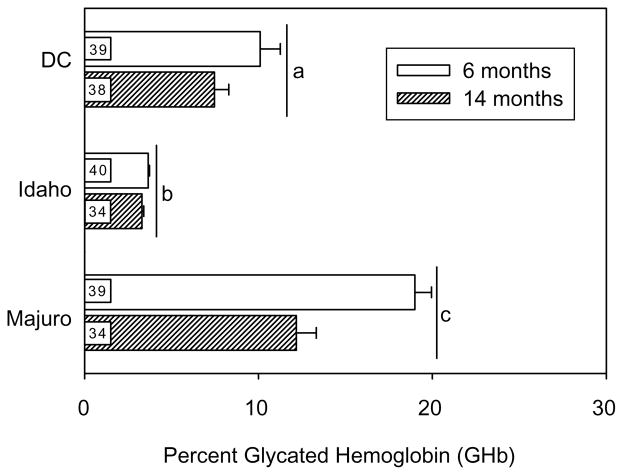

At 6 months of age, GHb levels in DC, Idaho, and Majuro mice were, 10, 3, and 19%, respectively, with similar levels in subgroups that died before or after 800 days of age (see Fig. 4). The differences among these stocks were of similar magnitude in samples taken at 14 months of age, and two-way ANOVA indicated significant main effects of stock and age on GHb levels (p<0.00001). Majuro mice had significantly higher levels of GHb relative to both the Idaho and DC mice at 6, as well as 14 months of ages (p<0.01), and GHb levels declined with age when averaged across all three stocks. A significant age×stock interaction term (p< 0.0001) indicated that the age-related change in GHb levels differed between stocks. Specifically, GHb levels were significantly lower in 14 versus 6-month-old Majuro mice, but there was no age-related change in either Idaho or DC mice. Interestingly, GHb levels at both 6 and 14 months were also significantly lower in the Idaho mice relative to the DC stock (p<0.01). The age at death (i.e. died before or after 800 days) had no effect on GHb levels within each of the stocks (p≥0.17; not shown).

Fig. 4.

Mean (±SEM) glycated hemoglobin (GHb) levels in 6 and 14-month-old DC, Idaho, and Majuro mice. Different letters indicate significance differences among stocks at p≤0.05 for all.

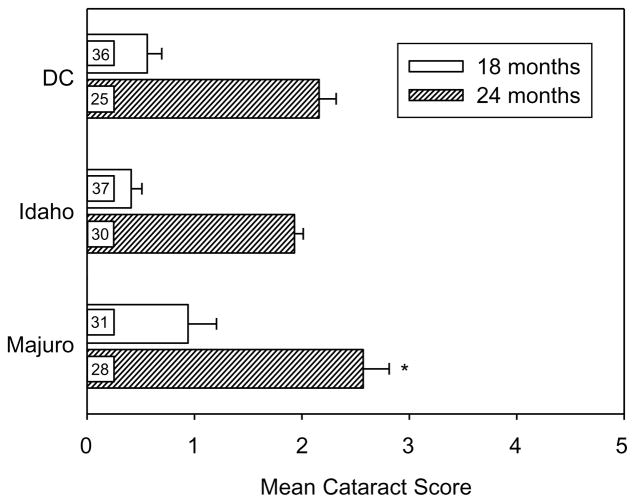

As shown in Fig. 5, mice of each stock showed an increase in average cataract severity between 18 and 24 months of age (p<0.00001). At 18 months of age, cataract severity tended to be higher in the Majuro mice than in DC or Idaho mice, but the difference among stocks was not significant (one-way ANOVA, p=0.10). However, by 24 months the difference between stocks was significant (p= 0.03), and the mean cataract score in the Majuro mice was significantly greater (p<0.05) than the cataract score in both the DC and Idaho mice, which were not significantly different from one another.

Fig. 5.

Mean (±SEM) cataract scores in 18 and 24-month-old DC, Idaho, and Majuro mice. (*) indicates a significance difference between stocks at p≤0.05 for all.

3.4. Glucose tolerance

Glucose tolerance tests were conducted on a group of DC, Idaho, and Majuro mice not included in the longevity study. Table 2 presents data on weight, fasting glucose, and fasting insulin levels for these tested mice at the ages of 2–4 (young), 10–14 (middle-aged), and 17–21 months (old). There were no significant differences among the groups in the ages at which these values were obtained, and as expected, DC and HET3 mice were significantly heavier (p<0.001) than the Idaho or Majuro mice at each age. In addition, there were significant differences among stocks for fasted glucose levels in both young (p<0.001) and middle-aged (p<0.0001) mice; Majuro mice had higher levels than DC and Idaho mice at both ages (p<0.05; Table 2). Idaho mice also had significantly higher fasted glucose levels than the DC mice at 10–14 (p<0.05), but not 2–4 months of age. However, there was no significant difference in fasted glucose levels between 17 and 20 month-old Idaho and Majuro and 21-month-old HET3 mice (p>0.3). Surprisingly, the fasted glucose level was significantly higher in middle-aged mice relative to both the young and old age groups (p<0.05). There were no statistically significant differences in fasting insulin levels among the three stocks at each of the three ages (p≥0.06), but the fasting insulin level did increase significantly with age (p<0.0001).

Table 2.

Fasting glucose and insulin of mice used for GTT

| Stock | 2–4 Month |

10–14 Month |

17–21 Month |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (g) | Glucose (mg/dL) | Insulin (μU/mL) | Weight (g) | Glucose (mg/Dl) | Insulin (μU/mL) | Weight (g) | Glucose (mg/dL) | Insulin (μU/mL) | |

| DC/HET3 | 27.3±4.8a (9)b | 110.8±32.8 (9) | 24.0±3.2 (9) | 29.1±2.4 (7) | 110.4±17.7 (7) | 27.3±7.3 (4) | 36.8±1.5 (5) | 121.2±5.3 (5) | 76.3±9.1 (5) |

| Idaho | 16.2±1.6 (10)c | 96.9±26.7 (10) | 23.5±2.7 (8) | 21.9±2.1 (7)c | 159.9±47.6 (7)c,d | 26.7±2.1 (7) | 25.9±0.7 (4)c | 118.6±7.3 (5) | 56.2±7.8 (5) |

| Majuro | 19.2±2.5 (10)c | 153.8±30.5 (10)c | 31.8±9.4 (10) | 22.7±3.7 (3)c | 269.7±10.8 (3)c | 30.7±15.1 (3) | 21.9±0.9 (6)c | 143.6±24.3 (5) | 44.1±12.8 (4) |

Value indicates mean±SEM.

Number in parentheses indicates sample size.

Indicates that the value is significantly different from the DC stock at p≤0.05 by one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey–Kramer post hoc test.

Indicates that the value is significantly different from the Majuro stock at p≤0.05 by one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey–Kramer post hoc test.

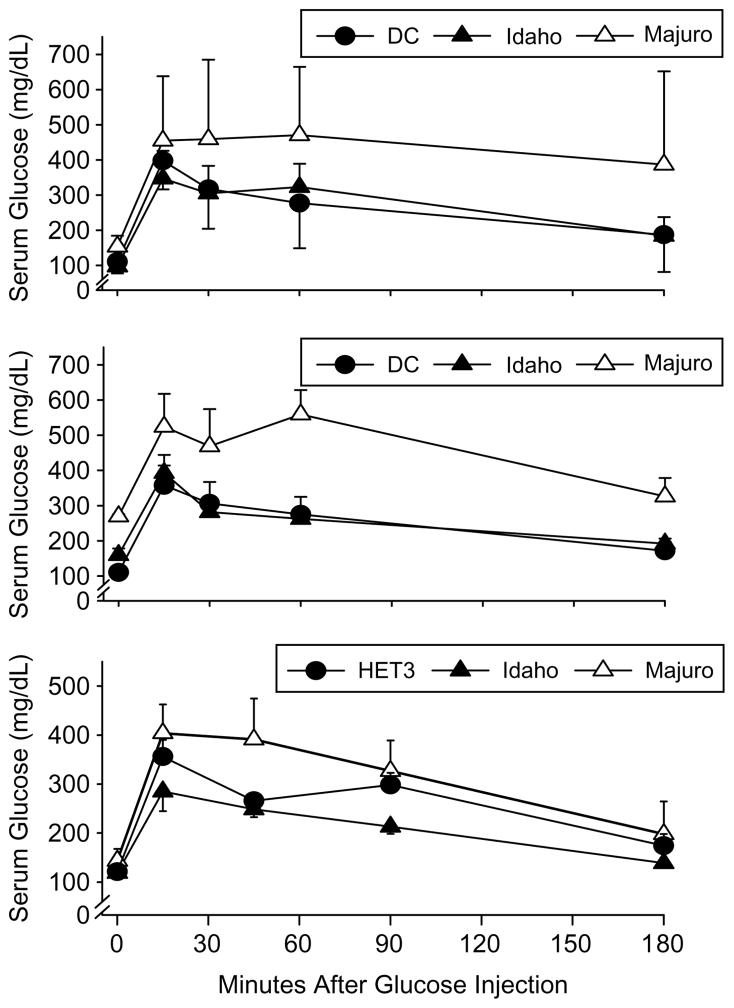

As shown in Fig. 6, Majuro mice have impaired glucose tolerance compared to either the DC or Idaho mice, both as young and as middle-aged adults. As expected, circulating glucose levels were significantly elevated above baseline in response to the glucose challenge in all three stocks (p< 0.0001), and mean glucose levels were significantly higher in the Majuro versus DC and Idaho stocks at both ages (p≤0.02; upper and middle panels). In the old mice glucose tolerance was significantly impaired in the Majuro stock relative to the Idaho, but not compared to HET3 mice (p< 0.05; lower panel). Furthermore, in young mice the mean± SEM glucose AUC for the Majuro mice (7.68×104± 11148) was 60 and 67% greater than the AUC for the Idaho (4.81×104±9403) and DC mice (4.59×104±18573), respectively. In the middle-aged adults the AUC for the Majuro mice (8.2×104±18635) was approximately 85% greater than the AUC for both the Idaho mice (4.47×104± 3082) and DC (4.37×104±18454) mice. These differences are all significant at p≤0.04. The mean glucose AUC for the old mice did not differ among stocks (p>0.6).

Fig. 6.

Serum glucose levels 0–180 min after an intraperitoneal glucose challenge (2 mg/g body weight) in DC, Idaho, and Majuro mice at 2–4 (top panel), 10–14 (middle panel), and 17–21 (bottom panel) months of age. Each point indicates the mean (±SEM) for each stock and time after injection. N=9, 10, and 10 (2–4-month-old); 7, 7, and 3 (10–14-month-old); and 5, 5, and 5 at 0, 15, 45, and 90 min and 3, 2, and 3 at 180 min (17–21-month-old) mice for the DC, Idaho, and Majuro stocks respectively.

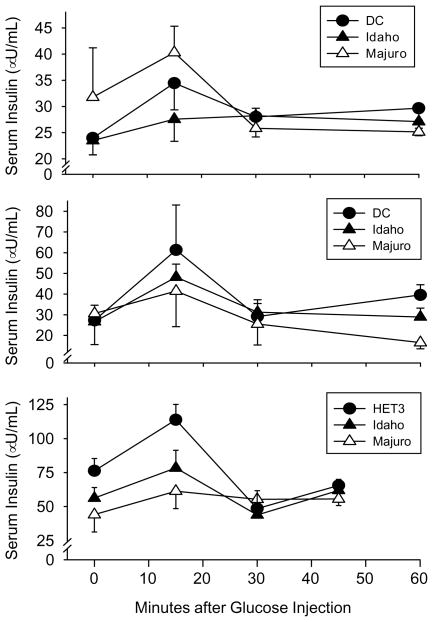

Despite the dramatic differences in glucose tolerance, there were no significant differences in insulin levels among the three mouse stocks in either young (p>0.7) or middle-aged (p>0.8) mice up to 60 min after an intraperitoneal glucose challenge (Fig. 7). Moreover, in young mice there was no significant change (p>0.3) in insulin levels during the GTT, although they did tend to increase in the first 15 min of the glucose challenge. On the other hand, insulin levels did change significantly with time in both the middle-aged and old mice (p≤0.02), and were significantly elevated at 15 min after the injection was delivered versus the 0 and 60-minute time points in the middle-aged mice, and versus the 0, 30, and 45-minute time points in the old mice (p<0.03). The insulin AUC did not vary among the stocks in either the young or middle-aged mice (p>0.68), but it was significantly greater in the old HET3 mice relative to the Majuro, but not the Idaho, stocks (p<0.02).

Fig. 7.

Serum insulin levels 0–60 min after an intraperitoneal glucose challenge (2 mg/g body weight) in DC, Idaho, and Majuro mice. Other details as in Fig. 6 except that N=5, 5, and 4 mice for the old HET3, Idaho, and Majuro stocks, respectively.

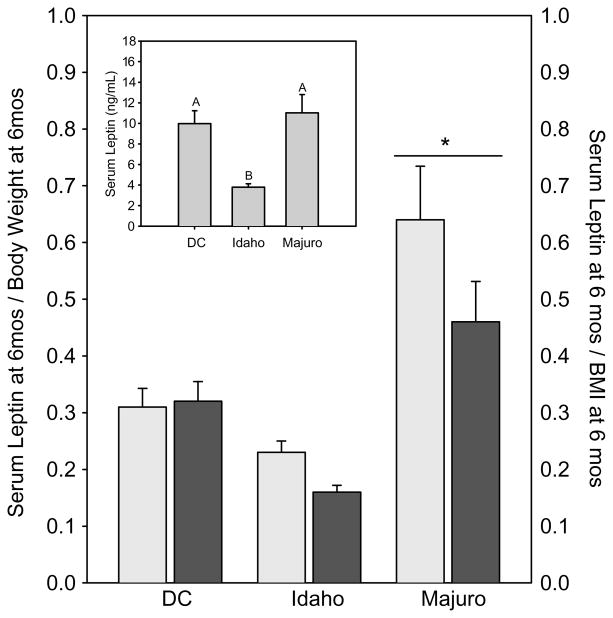

3.5. Serum leptin levels

At 6 months serum leptin levels (Fig. 8) differed significantly among the stocks (p<0.001) and were lower in the Idaho mice than in either the DC and Majuro stocks; leptin levels in Majuro and DC mice did not differ (Fig. 8 inset). As expected, serum leptin levels were significantly and positively correlated with 6-month body weight and BMI in both the Majuro and DC stocks (Spearman R≥0.58, p≤0.01 for each case); although these correlations were not significant in the Idaho stock (R<0.33, p>0.10). Due to the dramatic differences in body weight and BMI (Fig. 1), as well as the relationship between circulating leptin levels and the body weight and BMI measures, serum leptin levels were re-evaluated as a function of either total body weight or BMI at 6 months. From this perspective (Fig. 8), Majuro mice exhibited a dramatically higher serum leptin level, relative to weight or BMI, than either the DC or Idaho mice (body weight adjusted, p≤0.0005; BMI adjusted, p≤0.0005). Idaho and DC mice did not differ from one another (p≥0.60; Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Basal circulating serum leptin levels (inset), and leptin levels relative to weight (light bars) or BMI (dark bars) in 6-month old fed DC, Idaho, and Majuro mice. Each bar represents the mean±SEM for each stock. N=27, 25, and 27 for the DC, Idaho, and Majuro mice respectively. Different letters above bars indicate a significant difference among stocks at p≤0.05. * indicates a significant difference at p≤0.05.

Similar relationships were also noted in mice examined at 14 months age, i.e. low serum leptin concentrations in Idaho mice compared to the other two stocks, and high levels in the Majuro stock when adjusted either for weight or BMI (data not shown). At this age serum leptin levels were significantly correlated with 15-month body weights and BMIs in all three stocks (R≥0.33, p<0.05).

4. Discussion

The objectives of this study were twofold. First, we wanted to replicate our earlier finding (Miller et al., 2002) documenting significant differences in life span between descendants of wild-caught progenitor mice (Idaho, Majuro) and a stock of mice generated as a four-way cross of common laboratory strains (DC). Second, we wanted to assess whether the extended longevity in the wild-derived stocks was attributable lower glucose and insulin levels, because modulations in insulin production and glucose tolerance have been postulated to contribute to longevity in long-lived mutant and calorie restricted mice.

In our previous study (Miller et al., 2002) we demonstrated that the descendants of wild-caught progenitors (Idaho, Majuro) were significantly longer-lived than a laboratory-derived (DC) control stock. The test populations were composed of equal numbers of males and females of each stock, and survival analyses indicated that the life span curves of male and female Idaho and Majuro mice were indistinguishable within each stock (log-rank, p≥0.16), although male DC mice were significantly longer-lived than females (p=0.0006). In this study, only female mice were used for the life span, and for the Idaho stock both the estimated mean (+19%) and maximum (+10%) life span was significantly greater than the mean and maximum life span of the DC stock. Majuro mice have a longer maximum life span (+13%) without increases in mean life span; hence these results are consistent with our previous report (Miller et al., 2002). As in the previous study, Majuro mice also have a higher mortality risk in the first third of the life span and a lower risk thereafter, with a crossover point between 800 and 900 days with respect to the DC. The estimates of maximal life span are calculated as the average for the longest-lived 10% of mice; the death of the 6 Idaho and 2 Majuro mice still alive as of 27 October 2004 may lead to increased divergence between these wild-derived populations and the DC stock, in which all mice are now dead.

In 6-month-old female Majuro mice, fasting and non-fasting glucose levels were significantly higher than in Idaho and DC mice (G4) of the same age, and similarly, fasting glucose levels measured in male mice that were between 2–4 (G7) and 10–14 (G6) months old were significantly higher in the Majuro mice relative to the Idaho and DC stocks, although this difference was no longer apparent in the 17–20 (G5) month old mice (Table 2). Not unexpectedly, GHb levels were also dramatically (up to 5×) higher in Majuro females at both 6 and 14 months, which confirms and extends our earlier report (Miller et al., 2002). Lastly, male Majuro mice have profoundly impaired glucose tolerance in young and middle-aged mice (Fig. 6; upper and middle panels) although the insulin response to a glucose challenge is similar among stocks (Fig. 7; upper and middle panels). By 21 months of age a marked shift in glucose tolerance and the pattern of insulin secretion in response to the glucose challenge was evident in the HET3 control stock, and was suggestive of the onset of insulin resistance in these mice. Specifically, these mice had a glucose level similar to that in the Majuro mice despite their having a high level of circulating insulin (Figs. 6 and 7; lower panel). This finding is not unexpected, however, since impaired insulin signaling is a hallmark of aging (Chang and Halter, 2003; Muzumdar et al., 2004). Importantly, glucose tolerance in the old Majuro mice was still significantly impaired relative to the Idaho stock (Fig. 6; lower panel).

The relationship between circulating glucose and insulin levels is not always straightforward due to differences in genetic background, environmental conditions and gender (Goren et al., 2004). In this study the presence of elevated glucose levels in the face of an insulin profile similar to that of control mice at all three ages suggests that male Majuro mice may have a pancreatic deficiency that renders them unable to meet the demand for insulin produced by high glucose levels. The similarity in fasting glucose levels in 2–4 month-old male (154 mg/dL) versus 6-month-old female (170 mg/dL) Majuro mice suggests such a defect may apply to female mice as well. Whether this deficiency is due to differences in islet numbers, β-cell mass, and/or insulin production itself remains to be seen.

Caloric restriction restores the pattern of insulin secretion to youthful levels (Muzumdar et al., 2004), and has been well documented to reduce circulating glucose and insulin levels while significantly increasing insulin sensitivity in rodents (Masoro, 2000), dogs (Larson et al., 2003), and non-human primates (Gresl et al., 2003), although glucose and insulin levels are not always changed (Kemnitz et al., 1994; Cefalu et al., 1997). In mutant and transgenic models of extended life span a significant increase in insulin sensitivity has been noted as well (Dominici et al., 1999, 2002; Coschigano et al., 2003; Yamaza et al., 2004), which has led to the speculation that an increase in insulin sensitivity, and not a reduction glucose and insulin levels per se, is critical for lifespan extension. The results of this study, however, do not support this notion as neither of the long-lived mouse stocks seemed to exhibit a superior level of insulin sensitivity relative to the control stocks.

A clear association between hyperglycemia, impaired glucose tolerance and increased morbidity and mortality has been shown for human populations (Barrett-Connor and Ferrara, 1998; Rodriguez et al., 1996, 1999) as well as a variety of animal species (Mooradian and Thurman, 1999) with the formation of advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs) thought to play a prominent role. AGEs are the result of the non-enzymatic reaction of proteins with reducing sugars, such as glucose, whose importance in vivo was first realized in the 1970’s when it was that discovered that diabetics had significantly elevated levels of hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), a post-translational adduct of glucose with the β chain of the Hb molecule (Ulrich and Cerami, 2001). Since then, AGEs and AGE precursors such as GHb have been implicated in many of the sequelae common to diabetes, for example diabetic nephropathy (Cooper et al., 1998) and an increased incidence and severity of cataracts (Klein et al., 1998). It has also been suggested that the accumulation of AGEs with advancing age on long-lived proteins (e.g. collagen) is an important mediator of many of the complications of aging (Ulrich and Cerami, 2001). In this context, it is interesting that in C57BL/6 mice high indices of glycation have been associated with a significant decline in life expectancy (Sell et al., 2000), and that CR significantly reduces glycation products in rodents (Sell et al., 2000), as well as in non-human primates (Sell et al., 2003). AGEs can also promote oxidation-induced damage to proteins and have been implicated in the induction of DNA rearrangements (Ulrich and Cerami, 2001).

However, the results of this study clearly argue against the notion that a reduction in glucose and insulin levels, superior glucose tolerance and enhanced insulin sensitivity are required to achieve unusually long life span, at least in mice. Although modest, the life span extension seen in the Majuro stock is significant, and is accompanied by glucose and GHb levels that are far above those typically seen even in diabetic humans (Norris et al., 2002; Botas et al., 2003) and in other laboratory stocks of mice (Miller et al., 2002; Farhangkhoee et al., 2003). Indeed, Majuro mice display a profound impairment of glucose tolerance at as early as 3 months of age, an impairment that persists through at least 20 months of age (Fig. 6). While the increase in cataract severity (Fig. 5) does suggest that the Majuro mice are not totally resistant to the damaging effects of high blood glucose, the survival curve does not support the idea that lethal illness in late life is driven by glucose-induced damage in this stock. We also think it is unlikely that abnormalities in glucose regulation contribute to the increased rate of mortality observed in Majuro mice prior to 800 days, because there was no difference in mean glucose or GHb levels between those Majuro mice that died prior to reaching 800 days of age and those that lived to be greater than 800 days old.

Leptin has been reported both to inhibit (Sweeney et al., 2001; Perez et al., 2004) and in some circumstances to stimulate (Yaspelkis, et al., 2004; Haap et al., 2003) basal and insulin-stimulated glucose uptake. The direction of the effect seems to depend on the species, cell/tissue type, age of the animal tested and the duration of leptin exposure (Tajmir et al., 2003). In this study we found that basal, non-fasted leptin levels were similar in the DC and Majuro stocks, and were high relative to leptin levels in Idaho mice (Fig. 8, inset). Adjustments for differences in body weight and BMI among stocks, however, leads to a different picture. After adjustment for BMI or weight, leptin levels were dramatically (between 1.5 and 3-fold) higher in the Majuro mice relative to both the Idaho and DC stocks, which were indistinguishable from one another at both 6 (Fig. 8) and 14 months (data not shown). The significance of this difference currently remains unclear, but the effects of leptin on glucose uptake (Tajmir et al., 2003) may contribute to the impaired glucose tolerance of the Majuro stock.

Recent evidence suggests that the degree of visceral versus subcutaneous adiposity may play an important role in the determination of glucose tolerance (Barzilai and Gupta, 1999). In particular, reduction of visceral fat by surgical removal (Gabriely et al., 2002a,b; Gabriely and Barzilai, 2003) or as a result of CR (Gabriely et al., 2002a,b) is associated with a significant improvement in glucose tolerance in mice. Interestingly, there are dramatic differences in the gene expression profiles of visceral versus subcutaneous fat suggesting that each depot has a unique physiological role (Atzmon et al., 2002). In this study we used BMI as a surrogate measure of adiposity, and noted a disparity between glucose tolerance and adiposity, in that Majuro mice resembled Idaho mice in their low BMI, but were less glucose tolerant than either Idaho or the relatively obese DC mice. We do not, however, have information that would allow us to estimate the degree of visceral versus subcutaneous adiposity, which might differ among these stocks. Differences in distribution of adipose tissue could, in principle, influence circulating levels of adipocyte-derived cytokines (adipokines) such as adiponectin (Zhu et al., 2004) and resistin (Steppan and Lazar, 2004), which modulate insulin sensitivity.

Even though we do not know the basis for the profound impairment in glucose control in the Majuro stock, the data clearly show that their long life is achieved despite poor control of serum glucose levels. We also note that the Idaho stock, which exhibits an even more dramatic life span extension than the Majuro mice, does not seem to gain its survival advantage over the DC stock as a result of improved glucose control since the degree of glucose tolerance is indistinguishable between the two stocks in early-to-middle life, although this may become more important with increasing age. These results thus imply, contrary to suggestions derived from analyses of caloric restriction and of mutants with mutations in the GH/IGF axis, that a diminution of blood glucose and indices of glycation may not be a prerequisite for increased life span in mice.

Acknowledgments

We thank Gretchen Buehner, Maggie Vergara and Jessica Sewald for their technical assistance and Cameron Dingwall for his assistance in developing the glucose tolerance protocol. We thank Steve Austad and Robert Dysko for their continuing advice on this project. This work was supported by NIH Grants AG16699, AG11687, and AG08808 (to RA Miller).

References

- Atzmon G, Yang XM, Muzumdar R, Ma XH, Gabriely I, Barzilai N. Differential gene expression between visceral and subcutaneous fat depots. Horm Metab Res. 2002;34:622–628. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-38250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett-Connor E, Ferrara A. Isolated postchallenge hyperglycemia and the risk of fatal cardiovascular disease in older women and men. The Rancho Bernardo Study Diabetes Care. 1998;21:1236–1239. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.8.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barzilai N, Gupta G. Revisiting the role of fat mass in the life extension induced by caloric restriction. J Gerontol Biol Med Sci. 1999;54A:B89–B96. doi: 10.1093/gerona/54.3.b89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botas P, Delgado E, Castano G, Diaz dG, Prieto J, Diaz-Cadorniga FJ. Comparison of the diagnostic criteria for diabetes mellitus, WHO-1985, ADA-1997 and WHO-1999 in the adult population of Asturias (Spain) Diabetic Med. 2003;20:904–908. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2003.01006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cefalu WT, Wagner JD, Wang ZQ, Bell-Farrow AD, Collins J, Haskell D, Bechtold R, Morgan T. A study of caloric restriction and cardiovascular aging in cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis): a potential model for aging research. J Gerontol Biol Med Sci. 1997;52:B10–B19. doi: 10.1093/gerona/52a.1.b10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang AM, Halter JB. Aging and insulin secretion. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;284:E7–12. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00366.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Convit A, Wolf OT, Tarshish C, de Leon MJ. Reduced glucose tolerance is associated with poor memory performance and hippocampal atrophy among normal elderly. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2003;100:2019–2022. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0336073100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ME, Gilbert RE, Epstein M. Pathophysiology of diabetic nephropathy. Metab Clin Exp. 1998;47:3–6. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(98)90362-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coschigano KT, Holland AN, Riders ME, List EO, Flyvberg ALLA, Kopchick JJ. Deletion, but not antagonism, of the mouse growth hormone receptor results in severely decreased body weights, insulin and IGF-I levels and increased lifespan. Endocrinology. 2003;174:3799–3810. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean DJ, Brozinick JT, Jr, Cushman SW, Cartee GD. Calorie restriction increases cell surface GLUT-4 in insulin-stimulated skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:E957–E964. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1998.275.6.E957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhahbi JM, Mote PL, Wingo J, Tillman JB, Walford RL, Spindler SR. Calories and aging alter gene expression for gluconeogenic, glycolytic, and nitrogen-metabolizing enzymes. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:E352–E360. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1999.277.2.E352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhahbi JM, Mote PL, Wingo J, Rowley BC, Cao SX, Walford RL, Spindler SR. Caloric restriction alters the feeding response of key metabolic enzyme genes. Mech Ageing Dev. 2001;122:1033–1048. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(01)00230-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominici FP, Cifone D, Bartke A, Turyn D. Alterations in the early steps of the insulin-signaling system in skeletal muscle of GH-transgenic mice. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:E447–E454. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1999.277.3.E447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominici FP, Hauck S, Argentino DP, Bartke A, Turyn D. Increased insulin sensitivity and upregulation of insulin receptor, insulin receptor substrate (IRS)-1 and IRS-2 in liver of Ames dwarf mice. J Endocrinol. 2002;173:81–94. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1730081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominici FP, Argentino DP, Bartke A, Turyn D. The dwarf mutation decreases high dose insulin responses in skeletal muscle, the opposite of effects in liver. Mech Ageing Dev. 2003;124:819–827. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(03)00136-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhangkhoee H, Khan ZA, Mukherjee S, Cukiernik M, Barbin YP, Karmazyn M, Chakrabarti S. Heme oxygenase in diabetes-induced oxidative stress in the heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2003;35:1439–1448. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriely I, Barzilai N. Surgical removal of visceral adipose tissue: effects on insulin action. Curr Diabetes Rep. 2003;3:201–206. doi: 10.1007/s11892-003-0064-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriely I, Ma XH, Yang XM, Atzmon G, Rajala MW, Berg AH, Scherer P, Rossetti L, Barzilai N. Removal of visceral fat prevents insulin resistance and glucose intolerance of aging: an adipokine-mediated process? Diabetes. 2002a;51:2951–2958. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.10.2951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriely I, Ma XH, Yang XM, Rossetti L, Barzilai N. Leptin resistance during aging is independent of fat mass. Diabetes. 2002b;51:1016–1021. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.4.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goren HJ, Kulkarni RN, Kahn CR. Glucose homeostasis and tissue transcript content of insulin signaling intermediates in four inbred strains of mice: C57BL/6, C57BLKS/6, DBA/2, and 129X1. Endocrinology. 2004;145:3307–3323. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresl TA, Colman RJ, Havighurst TC, Byerley LO, Allison DB, Schoeller DA, Kemnitz JW. Insulin sensitivity and glucose effectiveness from three minimal models: effects of energy restriction and body fat in adult male rhesus monkeys. Am J Physiol Regul Integrat Comp Physiol. 2003;285:R1340–R1354. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00651.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haap M, Houdali B, Maerker E, Renn W, Machicao F, Hoffmeister HM, Haring HU, Rett K. Insulin-like effect of low-dose leptin on glucose transport in Langendorff rat hearts. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2003;111:139–145. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-39786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauck S, Hunter WS, Danilovich N, Kopchick JJ, Bartke A. Reduced levels of thyroid hormones, insulin, and glucose, and lower body core temperature in the growth hormone receptor/binding protein knockout mouse. Exp Biol Med. 2001;226:552–558. doi: 10.1177/153537020122600607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imbeault P, Prins JB, Stolic M, Russell AW, O’Moore-Sullivan T, Despres JP, Bouchard C, Tremblay A. Aging per se does not influence glucose homeostasis: in vivo and in vitro evidence. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:480–484. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.2.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemnitz JW, Roecker EB, Weindruch R, Elson DF, Baum ST, Bergman RN. Dietary restriction increases insulin sensitivity and lowers blood glucose in rhesus monkeys. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:E540–E547. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1994.266.4.E540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein BE, Klein R, Lee KE. Diabetes, cardiovascular disease, selected cardiovascular disease risk factors, and the 5-year incidence of age-related cataract and progression of lens opacities: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;126:782–790. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(98)00280-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson BT, Lawler DF, Spitznagel EL, Jr, Kealy RD. Improved glucose tolerance with lifetime diet restriction favorably affects disease and survival in dogs. J Nutr. 2003;133:2887–2892. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.9.2887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masoro EJ. Caloric restriction and aging: an update. Exp Gerontol. 2000;35:299–305. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(00)00084-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RA, Dysko R, Chrisp C, Seguin R, Linsalata L, Buehner G, Harper JM, Austad S. Mouse (Mus musculus) stocks derived from tropical islands: New models for genetic analysis of life history traits. J Zool. 2000;250:95–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7998.2000.tb00580.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RA, Harper JM, Dysko R, Durkee SJ, Austad SN. Longer life spans and delayed maturation in wild-derived mice. Exp Biol Med. 2002;227:500–508. doi: 10.1177/153537020222700715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooradian AD, Thurman JE. Glucotoxicity: potential mechanisms. Clin Geriatr Med. 1999;15:255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzumdar R, Ma X, Atzmon G, Vuguin P, Yang X, Barzilai N. Decrease in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion with aging is independent of insulin action. Diabetes. 2004;53:441–446. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.2.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris SL, Lau J, Smith SJ, Schmid CH, Engelgau MM. Self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of the effect on glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1159–1171. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.7.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez C, Fernandez-Galaz C, Fernandez-Agullo T, Arribas C, Andres A, Ros M, Carrascosa JM. Leptin impairs insulin signaling in rat adipocytes. Diabetes. 2004;53:347–353. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.2.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez BL, Curb JD, Burchfiel CM, Huang B, Sharp DS, Lu GY, Fujimoto W, Yano K. Impaired glucose tolerance, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease risk factor profiles in the elderly. The Honolulu Heart Program Diabetes Care. 1996;19:587–590. doi: 10.2337/diacare.19.6.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez BL, Lau N, Burchfiel CM, Abbott RD, Sharp DS, Yano K, Curb JD. Glucose intolerance and 23-year risk of coronary heart disease and total mortality: the Honolulu Heart Program. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:1262–1265. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.8.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatino F, Masoro EJ, McMahan CA, Kuhn RW. Assessment of the role of the glucocorticoid system in aging processes and in the action of food restriction. J Gerontol. 1991;46:B171–B179. doi: 10.1093/geronj/46.5.b171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saydah SH, Loria CM, Eberhardt MS, Brancati FL. Abnormal glucose tolerance and the risk of cancer death in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:1092–1100. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sell DR, Kleinman NR, Monnier VM. Longitudinal determination of skin collagen glycation and glycoxidation rates predicts early death in C57BL/6NNIA mice. FASEB J. 2000;14:145–156. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.14.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sell DR, Lane MA, Obrenovich ME, Mattison JA, Handy A, Ingram DK, Cutler RG, Roth GS, Monnier VM. The effect of caloric restriction on glycation and glycoxidation in skin collagen of nonhuman primates. J Gerontol Biol Med Sci. 2003;58:508–516. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.6.b508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steppan CM, Lazar MA. The current biology of resistin. J Intern Med. 2004;255:439–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney G, Keen J, Somwar R, Konrad D, Garg R, Klip A. High leptin levels acutely inhibit insulin-stimulated glucose uptake without affecting glucose transporter 4 translocation in l6 rat skeletal muscle cells. Endocrinology. 2001;142:4806–4812. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.11.8496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajmir P, Kwan JJ, Kessas M, Mozammel S, Sweeney G. Acute and chronic leptin treatment mediate contrasting effects on signaling, glucose uptake, and GLUT4 translocation in L6-GLUT4myc myotubes. J Cell Physiol. 2003;197:122–130. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich P, Cerami A. Protein glycation, diabetes, and aging. Recent Prog Horm Res. 2001;56:1–21. doi: 10.1210/rp.56.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weindruch R, Walford R. The Retardation of Aging and Disease by Dietary Restriction. Charles C. Thomas; Springfield, IL: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Wetter TJ, Gazdag AC, Dean DJ, Cartee GD. Effect of calorie restriction on in vivo glucose metabolism by individual tissues in rats. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:E728–E738. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1999.276.4.E728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaza H, Komatsu T, Chiba T, Toyama H, To K, Higami Y, Shimokawa I. A transgenic dwarf rat model as a tool for the study of calorie restriction and aging. Exp Gerontol. 2004;39:269–272. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaspelkis BB, III, Singh MK, Krisan AD, Collins DE, Kwong CC, Bernard JR, Crain AM. Chronic leptin treatment enhances insulin-stimulated glucose disposal in skeletal muscle of high-fat fed rodents. Life Sci. 2004;74:1801–1816. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu M, Miura J, Lu LX, Bernier M, deCabo R, Lane MA, Roth GS, Ingram DK. Circulating adiponectin levels increase in rats on caloric restriction: the potential for insulin sensitization. Exp Gerontol. 2004;39:1049–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2004.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]