AGAP1/AP-3-dependent endocytic recycling of M5 muscarinic receptors promotes dopamine release

G-protein-coupled receptors, such as the M5 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor, undergo rapid internalization and thus desensitization after agonist stimulation. This study identifies a novel molecular mechanism for this internalization step that involves the direct interaction between the AP-3 adaptor complex regulator AGAP1 and M5 receptors.

Keywords: AGAP1, AP-3, dopamine, endocytic recycling, muscarinic receptors

Abstract

Of the five mammalian muscarinic acetylcholine (ACh) receptors, M5 is the only subtype expressed in midbrain dopaminergic neurons, where it functions to potentiate dopamine release. We have identified a direct physical interaction between M5 and the AP-3 adaptor complex regulator AGAP1. This interaction was specific with regard to muscarinic receptor (MR) and AGAP subtypes, and mediated the binding of AP-3 to M5. Interaction with AGAP1 and activity of AP-3 were required for the endocytic recycling of M5 in neurons, the lack of which resulted in the downregulation of cell surface receptor density after sustained receptor stimulation. The elimination of AP-3 or abrogation of AGAP1–M5 interaction in vivo decreased the magnitude of presynaptic M5-mediated dopamine release potentiation in the striatum. Our study argues for the presence of a previously unknown receptor-recycling pathway that may underlie mechanisms of G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) homeostasis. These results also suggest a novel therapeutic target for the treatment of dopaminergic dysfunction.

Introduction

The striatum, the main input nucleus of the basal ganglia, regulates motor control and motivated behaviours through the integration of dopaminergic, glutamatergic, and cholinergic neurotransmission. Whereas the striatum receives extrinsic midbrain dopaminergic and cortical glutamatergic input, tonically active giant aspiny cholinergic interneurons (TANs) provide extensive intrinsic innervation. The cellular actions of acetylcholine (ACh) are mediated both by ionotropic nicotinic receptors and by metabotropic muscarinic receptors (MRs), a family of five G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). MRs are expressed widely, with multiple subtypes present in nearly every mammalian tissue (Wess et al, 2007). Striatal MRs are expressed in a complex, overlapping pattern, where they function as post-synaptic receptors on medium spiny projection neurons, as inhibitory autoreceptors at TAN terminals, and as modulatory receptors at both glutamatergic and dopaminergic terminals (Zhang et al, 2002a, 2002b; Pisani et al, 2007). Notably, the low abundance, Gαq-coupled MR5 (M5) is the only MR subtype expressed in midbrain dopaminergic neurons (Weiner et al, 1990). Activation of these M5 receptors potentiates dopamine release in the striatum, and M5 dysfunction has been implicated in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia and drug addiction (Yamada et al, 2001; Basile et al, 2002; Forster et al, 2002; De Luca et al, 2004; Thomsen et al, 2005). However, the precise details of M5 function, regulation, and response plasticity in the basal ganglia remain obscure.

The MR family displays strong sequence similarity between subtypes across the extracellular and transmembrane regions that encompass the presumed orthosteric ACh-binding site (Wess et al, 1995). As a result, development of strongly subtype-selective MR ligands has not been successful. The poor selectivity of MR ligands, in combination with the ubiquitous, overlapping expression pattern of MRs, has complicated the study of MR physiology in vivo and slowed development of MR-targeted therapeutics. However, the MRs possess an unusually large third intracellular (i3) loop region whose sequence, in contrast to that of extracellular and transmembrane domains, is highly divergent between subtypes. As GPCR cytoplasmic domains affect receptor function through the binding of signalling, regulatory and trafficking proteins (Ritter and Hall, 2009), identification of M5 i3 loop-interacting molecules should both uncover subtype-specific functional mechanisms and offer targets for selective small-molecule modulation of M5 activity.

Among molecules known to interact with the cytoplasmic domains of integral membrane proteins, the adaptor protein (AP) complexes function as key mediators of intracellular trafficking. APs coordinate the recruitment and transport of transmembrane proteins (including GPCRs) through endosomal and secretory pathways by binding to both cargo protein targeting motifs and membrane vesicle coat proteins (Nakatsu and Ohno, 2003). Of the four characterized APs, AP-3 is unique in that in addition to a ubiquitously expressed isoform (AP-3a), a second complex (AP-3b) is expressed exclusively in neurons. Whereas AP-3a directs the traffic of membrane proteins to lysosomes and lysosome-like organelles (Dell'Angelica et al, 1999; Peden et al, 2004), AP-3b was shown to mediate the biogenesis of endosome-derived synaptic vesicles and to regulate protein sorting to these organelles (Blumstein et al, 2001; Salazar et al, 2004). Membrane recruitment of AP-3 subunits is mediated by Arf1, a small GTPase regulated by a variety of specific guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) and GTPase activating proteins (GAPs) (Lefrancois et al, 2004; Nie and Randazzo, 2006). Interestingly, one of these ArfGAPs, AGAP1, was shown to bind directly to AP-3a and to regulate both AP-3 membrane recruitment and the targeting of a lysosomal limiting membrane protein (Nie et al, 2003, 2005). However, neither AP-3b nor AGAP1 have been implicated in the trafficking of GPCRs.

In this study, we identified AGAP1 as a direct binding partner of the M5 i3 loop region. This interaction mediated the binding of the AP-3 adaptor complex to M5. We determined that M5 receptors undergo efficient activity-induced endocytic recycling in an AGAP1- and AP-3b-dependent manner. Inhibition of the AGAP1/M5 interaction or elimination of AP-3 decreased the magnitude of evoked dopamine release from striatal nerve terminal preparations and brain slices. We propose that a novel AP-3b-dependent trafficking mechanism targets presynaptic M5 receptors for recycling through an intrinsic cargo-recognition function of AGAP1. Recycling of M5 may therefore be critical for maintaining the coordination between cholinergic and dopaminergic neurotransmission in the striatum.

Results

AGAP1 interacts with the M5 i3 loop in the yeast two-hybrid system

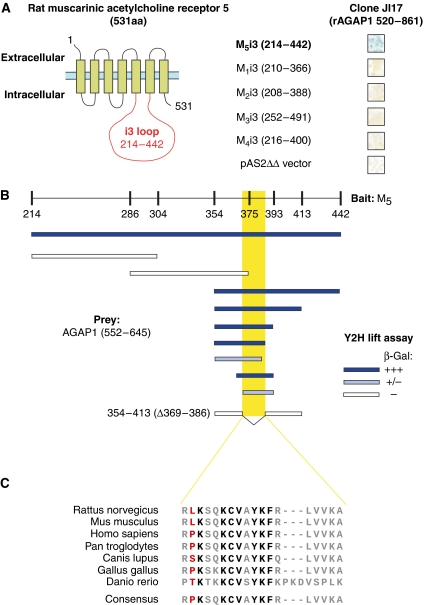

In an effort to identify M5-interacting proteins, we performed a yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) screen using the i3 loop region (residues 214–442) of the rat M5 receptor as bait. We screened 1.8 × 107 diploid clones from a rat brain pACT2 cDNA library. Out of a total of 32 clones doubly positive for the reporter genes HIS3 and lacZ, sequencing revealed four clones as encoding a C-terminal fragment of the ArfGAP protein AGAP1 (residues 520–861). To investigate the specificity of this putative interaction in the Y2H system, we rescued an AGAP1520−861-encoding prey plasmid and used it to cotransform yeast along with either empty bait plasmid or i3 loop baits from the five MRs. The interaction was subtype specific, as only the M5 i3 loop (M5i3) bait displayed lacZ activation with this clone in the X-gal filter lift assay (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

AGAP1 interacts with a defined region of the M5 i3 loop in a receptor subtype-specific manner. (A) M5 receptor topology, with the i3 loop region highlighted in red. Right, X-Gal lift assay results for Y2H interaction assay between rat MRi3-Gal4 bait proteins and the rat AGAP1 clone isolated in the M5i3 screen. Blue colour reflects LacZ reporter gene activation, indicating a positive bait/prey interaction. pAS2ΔΔ, empty bait vector negative control. (B) Summary of X-Gal lift assay results from Y2H interaction assays. M5 214−442 corresponds to the M5 i3 loop region. Truncation and deletion mutants were assayed for AGAP1542−645 interaction as indicated. Dark blue indicates strong lacZ activation; light blue indicates weak lacZ activation; white indicates no activation, and yellow box indicates identified minimum domain of interaction (residues 369–386). (C) Multiple-species alignment of the identified M5i3 domain of interaction with AGAP1. Residue colours indicate degree of conservation across the seven listed species (black, 100%; grey, >50%; red, ⩽50%).

We next used a Y2H mapping strategy to identify an 18-amino-acid region of M5i3 (residues 369–386) as critical for interaction with AGAP1. This result was confirmed by successful disruption of the AGAP1 interaction after deletion of the putative domain of interaction (Δ AGAP1-binding domain (ΔABD)) from the M5i3 bait construct (Figure 1B). Multiple-species alignment of mammalian, avian and teleost M5 sequences revealed the putative essential region of interaction to be evolutionally conserved (Figure 1C).

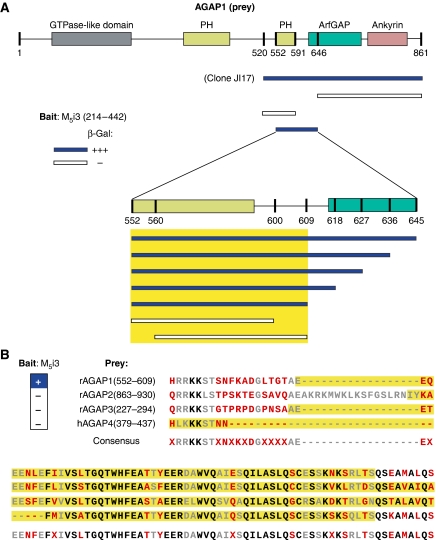

AGAP proteins contain GTP-binding protein-like, pleckstrin homology (PH), ArfGAP and ankyrin repeat domains (Nie et al, 2002). The PH domain is found in a variety of signalling and membrane-associated molecules; it is known to bind phospholipids and is also involved in protein–protein interactions with Arf1 and G-protein βγ subunits (Lodowski et al, 2003; Godi et al, 2004; Lemmon, 2004). In AGAP1, the PH domain is split by an intervening sequence into N- and C-terminal parts (Nie et al, 2002). We used a Y2H mapping strategy to determine the region of AGAP1 required for interaction with the M5 i3 loop. We identified a 59-amino-acid region of AGAP1 (residues 552–609) containing the entire C-terminal portion of the split PH domain as the minimum region sufficient for M5i3 binding (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

AGAP1 domain-of-interaction mapping. (A) Summary of X-Gal lift assay results from Y2H interaction assays. Top, AGAP1 functional domains. Below, AGAP1 truncation mutants were assayed for M5i3 interaction as indicated. Blue indicates strong lacZ activation; white indicates no activation, and yellow box indicates identified minimum domain of interaction. (B) Regions of AGAP2 and AGAP3 (rat) and AGAP4 (human) homologous to that of the rat AGAP1 critical domain of interaction defined in (A) fail to interact with the M5 i3 loop in the Y2H lift assay. Blue indicates strong lacZ activation and white indicates no activation. Residue colours indicate degree of conservation across the four proteins (black, 100%; grey, 75%; red, ⩽50%). Assayed regions are highlighted in yellow.

The AGAP family contains four characterized proteins: AGAP1, AGAP2 (centaurin γ1), AGAP3 (centaurin γ3), and AGAP4 (MRIP2/centaurin γ-like family 1), with the latter present only in humans (Kahn et al, 2008). To further examine the specificity of the M5/AGAP1 interaction, we cloned regions of AGAP family members homologous to the AGAP1 region that mediates the M5i3 interaction (AGAP1552−609) from rat (AGAP2 and AGAP3) and human (AGAP4) brain cDNA libraries, and tested them against the M5i3 bait by Y2H assay. Only AGAP1 was found to interact with the M5 i3 loop (Figure 2B).

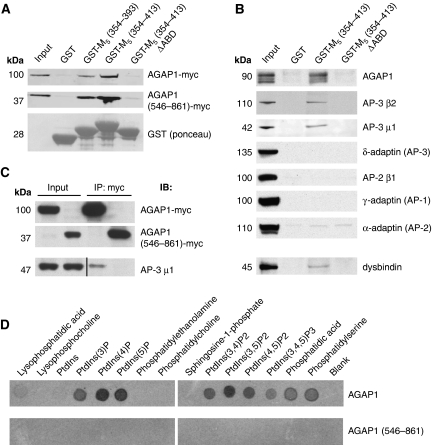

An AGAP1/AP-3 complex interacts with the M5 i3 loop

To confirm the M5i3/AGAP1 interaction, we performed in vitro binding studies using recombinant M5i3 proteins as affinity matrices. Glutathione-S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins encoding M5i3 fragments including (M5 354−393, M5 354−413) or excluding (M5 354−413ΔABD) the domain of AGAP1 interaction identified by Y2H were mixed with lysates from COS-7 cells overexpressing myc-tagged AGAP1 proteins. Pulled-down proteins were analysed by SDS–PAGE and immunoblot, revealing interaction of GST-M5 354−393 and GST-M5 354−413, but not GST-M5 354−413ΔABD, with AGAP1-myc. This pattern of interaction was also observed for the AGAP1546−861-myc protein, a truncation mutant retaining the critical domain of M5i3 interaction (Figure 3A). Using an anti-AGAP1 antibody, we also observed specific binding of endogenous AGAP1 to the M5i3 in GST-pull-down experiments performed with rat brain lysates (Figure 3B, top panel). In addition, a full-length GST-M5i3 fusion protein displayed specific interaction with in vitro transcribed/translated AGAP1520−861 (Supplementary Figure S1).

Figure 3.

AGAP1 interacts in vitro with the M5 i3 loop in a phospholipid-independent manner. (A) Lysates from COS-7 cells expressing myc-tagged rat AGAP1 proteins (full-length or C-terminal fragment) were incubated with indicated wild-type or domain-of-interaction deletion mutant M5i3-GST proteins immobilized on glutathione resin. Bound AGAP1 proteins were analysed by SDS–PAGE and myc immunoblot; molecular weights are listed in kilodaltons (kDa). GST proteins were detected by Ponceau red staining. Input, 1% of total. (B) Immobilized GST proteins were incubated with rat brain lysate (top seven panels) or human neuroblastoma SK-N-MC cell lysate (bottom panel), and bound endogenous proteins were analysed by SDS–PAGE and immunoblot with antibodies as indicated. Input, 0.25% (top panel) or 0.5% (lower panels) of total. (C) Myc-tagged rat AGAP1 proteins (full-length and C-terminal fragments) were expressed in NIH-3T3 cells and immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-myc antibodies. Immunoprecipitates were analysed by SDS–PAGE and immunoblot (IB) for myc and the AP-3a subunit protein AP-3 μ1. AP-3 μ1 lanes were analysed in parallel on a separate gel, and were cropped so as to exclude lanes irrelevant to this experiment. Input, 1% of total. (D) Phospholipid dot-blot arrays were incubated with [35S]methionine-labelled AGAP1 proteins (full-length and C-terminal fragment), and bound proteins were visualized by autoradiography. PtdIns, phosphatidylinositol.

As AGAP1 was shown to interact with the AP-3 adaptor complex (Nie et al, 2003), we next tested the hypothesis that AP-3 could interact indirectly with the M5 i3 loop through AGAP1. Subunits present in both the ubiquitous (AP-3 μ1) and neuron-specific (AP-3 β2) isoforms of the heterotetrameric AP-3 adaptor complexes were detected in pull-down assays using GST-M5 354−413, but not GST-M5 354−413ΔABD or native GST (Figure 3B). Interaction of M5i3 with δ-adaptin (a subunit common to both AP-3a and AP-3b) was not observed (Figure 3B). The association of the AP-3 adaptor complex with M5i3 appeared to be specific, as AP-1 and AP-2 complex subunits did not bind to GST-M5 354−413 (Figure 3B). The AP-3 adaptor complex is known to interact physically and functionally with other trafficking protein complexes, including BLOC-1 (Di Pietro et al, 2006; Salazar et al, 2006, 2009). The BLOC-1 subunit protein dysbindin was shown to bind directly to AP-3 through the μ1 subunit (Li et al, 2003; Taneichi-Kuroda et al, 2009). Using lysate prepared from a human neuroblastoma line, we observed specific interaction between dysbindin and GST-M5 354−413, but not GST-M5 354−413ΔABD or native GST (Figure 3B, bottom panel). Taken together, these data corroborate the Y2H results indicating a subtype-specific and domain-delineated interaction between M5 and AGAP1, and suggest that AGAP1 binding may be mediating the interaction of a larger AP-3-containing complex with the M5 i3 loop.

To confirm that the AGAP1/M5 i3 loop interaction was direct, we performed immunoprecipitations of myc-tagged AGAP1 proteins expressed in NIH-3T3 cells. Full-length AGAP1 coimmunoprecipitated the AP-3a subunit AP-3 μ1, as reported earlier (Nie et al, 2003). However, the AGAP1546−861 mutant was unable to coimmunoprecipitate AP-3 μ1 (Figure 3C). As both full-length and truncated forms of AGAP1 interacted with M5i3 in pull-down and Y2H assays, these coimmunoprecipitation data indicated that AP-3 binding was not required for the interaction of AGAP1 with M5.

Finally, we investigated the role of phospholipids in the AGAP1/M5i3 interaction by way of a lipid array overlay assay using radiolabelled AGAP1 proteins. Full-length AGAP1 bound to a variety of phospholipids, phosphatidic acid, and phosphatidylserine, with strongest binding to phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate and phosphatidylinositol-(3,5)-bisphosphate (Figure 3D). However, AGAP1546−861, in which the PH domain is disrupted but the domain of M5i3 interaction is maintained, displayed no phospholipid binding (Figure 3D). Thus, AGAP1 binds phospholipids through its split PH domain, but this activity is dispensable for binding to M5.

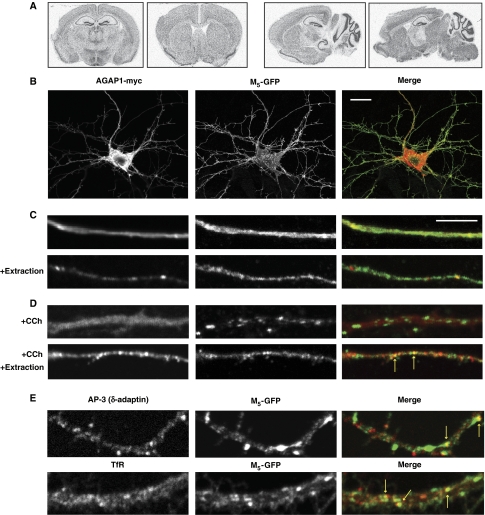

Endocytosed M5 colocalizes with AGAP1 and AP-3 in cultured neurons

AGAP1 is expressed in virtually all rodent and human tissues and cultured cell lines (Xia et al, 2003; Meurer et al, 2004; Nie et al, 2005). In mouse brain, in situ hybridization of an AGAP1 antisense riboprobe revealed widespread, uniform mRNA distribution (Figure 4A). Epitope-tagged AGAP1 expressed exogenously in NIH-3T3 and U87 tissue culture cells was previously shown to exhibit a punctate distribution pattern consistent with localization to AP-3-positive endosomes (Nie et al, 2002, 2003). Although M5 mRNA is detected at low abundance in the brain, the tissue and subcellular distribution of M5 protein has not been described. We expressed epitope-tagged proteins in cultured embryonic rat hippocampal neurons to investigate the relative subcellular distribution of M5 and AGAP1. We used a cytoplasmically tagged (C-terminal GFP) M5 receptor, as we observed that extracellular epitope fusions inhibit cell surface delivery of MRs (data not shown). Both AGAP1-myc (Figure 4B, left) and M5-GFP (Figure 4B, middle) were present in the soma and processes of transfected hippocampal neurons, with a largely diffuse staining pattern apparent in axon-like processes (Figure 4C, top row). In some cases (including that of the AGAP1-related protein ACAP1), cytosol extraction prior to fixation and immunostaining can reveal the otherwise-obscured membrane-bound pool of proteins (Morris and Cooper, 2001; Dai et al, 2004). We observed a more punctate distribution of AGAP1-myc when cells were subjected to a mild detergent extraction before fixation (Figure 4C, bottom row). In addition, subcellular fractionation of rat brain homogenates revealed a distribution of AGAP1 (with well-separated sedimentation peaks at fractions 10 and 24) similar to that of AP-3a, AP-3b and other endosome-associated rab proteins (Supplementary Figure S2).

Figure 4.

Agonist-internalized M5 colocalizes with AGAP1, AP-3, and transferrin receptor in primary cultured rat hippocampal neurons. (A) Autoradiograph of C57Bl/6 mouse brain coronal (left) and sagittal (right) sections labelled by in situ hybridization using a [33P]AGAP1 riboprobe. (B) Neurons were transfected with M5-GFP and AGAP1-myc plasmids, fixed, immunostained for myc-tag (red) and GFP (green), and imaged by confocal microscopy. Scale bar=20 μm. (C, D) Neurons were transfected with M5-GFP and AGAP1-myc plasmids and treated with or without 1 mM carbachol (CCh) for 60 min. To visualize the membrane-bound pool of exogenously expressed AGAP1-myc, cytosolic extraction with 0.03% saponin was performed before fixation as indicated. Cells were immunostained for GFP (green) and myc (red) and imaged by confocal microscopy. Yellow arrows indicate green/red puncta overlap. Scale bar=5 μm. (E) Neurons were transfected with M5-GFP and treated with 1 mM CCh for 30 (top) or 60 (bottom) min, followed by fixation and immunostaining for GFP (green) and the AP-3a/AP-3b subunit δ-adaptin (red) or the somatodendritic endosomal-recycling pathway marker transferrin receptor (TfR) (red). Yellow arrows indicate green/red puncta overlap. Scale is identical to (C).

MRs M1–M4 have been shown to undergo agonist-induced internalization from the plasma membrane to endosomes, followed by either endocytic recycling or targeting for lysosomal degradation, depending on receptor subtype and cell type (Tolbert and Lameh, 1996; Volpicelli et al, 2001; Delaney et al, 2002; Popova and Rasenick, 2004). Upon treatment with the MR agonist carbachol (CCh; 1 mM), we observed a redistribution of M5-GFP to punctate structures, consistent with endosomal sequestration (Figure 4D, top row). In detergent-extracted cells, puncta doubly positive for M5-GFP and AGAP1-myc were observed after 60 min of CCh treatment, suggesting the presence of endocytosed M5 receptors in an AGAP1-positive subcellular compartment (Figure 4D, bottom row). In support of this observation (although noting that the Z-resolution of images was not sufficient to differentiate between internal structures and overlying plasma membrane domains), quantification of detergent-extracted neuronal processes revealed a significant decrease in colocalization of M5-GFP fluorescence with AGAP1-myc-positive puncta after 15 min of CCh treatment (P=0.02), with colocalization trending upwards after extended (30 and 60 min) CCh incubation (Supplementary Figure S3).

After CCh treatment, we also observed overlap between M5-GFP and the AP-3 complex subunit δ-adaptin, as well as with the constitutively recycled somatodendritic membrane protein transferrin receptor (TfR) (Figure 4E). Our imaging data therefore indicated that physical interaction between M5 and AGAP1 could occur in endosomes and suggested a role for the interaction in the trafficking of internalized receptors through the endocytic-recycling pathway.

AGAP1 and AP-3b regulate endocytic recycling of M5 in a neuron-specific manner

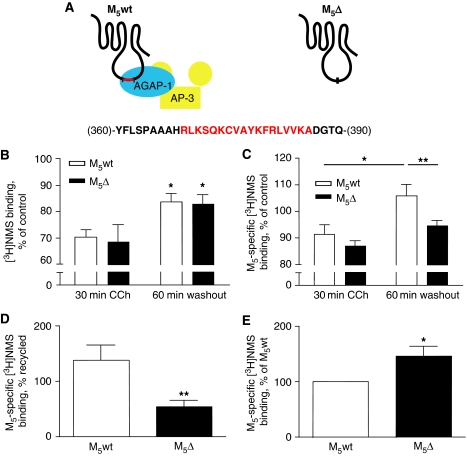

To investigate the role of AGAP1 interaction in M5 trafficking, we constructed a receptor in which the critical domain of interaction in the i3 loop was disrupted (M5ΔABD; ‘M5Δ') (Figure 5A). We used the hydrophilic, cell-impermeant muscarinic antagonist radioligand [3H]-N-methyl-scopolamine ([3H]NMS) to quantitatively monitor cell surface M5 receptor density in intact cells. We first examined internalization and endocytic recycling of agonist-internalized M5 receptors expressed in HEK-293T cells, which were left untreated, treated with CCh (0.1 mM) to induce M5 internalization or CCh-treated followed by a 1-h washout period to allow for recycling of internalized receptors. The 30-min CCh treatment was observed in time course experiments to result in a steady state of M5 sequestration (data not shown). No difference between wild-type M5 (M5wt) and M5Δ receptors was observed in the degree of internalization after CCh treatment, nor in the magnitude of receptor surface recycling after agonist washout (Figure 5B). However, basal surface density of M5Δ receptors was slightly increased as compared with M5wt (Supplementary Figure S4A).

Figure 5.

Efficient endocytic recycling of M5 receptors in cultured embryonic rat cortico-hippocampal neurons requires the presence of the AGAP1 domain of interaction region. (A) Schematic of the wild-type M5 receptor (M5wt) and the AGAP1 domain-of-interaction (ABD) deletion mutant receptor (M5Δ), with deleted residues indicated in red. (B) HEK-293T cells were transiently transfected with M5wt or M5Δ constructs. Two days later, cells were treated with 0.1 mM CCh for 30 min with or without a subsequent 60 min washout period, or were left untreated. Cell surface M5 receptors were assayed in triplicate by [3H]NMS radioligand binding as described. Data are expressed as a percent of untreated control values. *P<0.05 two-way ANOVA (treatment) (n=3). (C) Neurons were nucleofected with M5wt, M5Δ, or empty vector control plasmids and cultured for 13 days. Cells were treated as in (B), and cell surface muscarinic receptors were assayed in triplicate by [3H]NMS radioligand binding and M5-specific signal was calculated. Data are expressed as a percent of untreated control values. *,**P<0.05/P<0.01, two-way ANOVA/Bonferroni post-test (n=5). (D) Data in (C) are expressed as a percent of CCh-internalized receptors recycled after 1 h washout. **P=0.01, two-tailed paired Student's t-test (n=5). (E) Steady-state surface expression of M5wt and M5Δ receptors was assayed in untreated primary cultured neurons as in (C). Data were normalized to M5wt for each experiment. *P<0.05, one-sample Student's t-test (versus 100) (n=6). Error bars for all graphs represent s.e.m.

AP-3b mediates trafficking functions distinct from those of ubiquitous AP-3a in neurons (Blumstein et al, 2001; Nakatsu et al, 2004; Newell-Litwa et al, 2007). As we observed AGAP1-mediated binding of the neuron-specific AP-3b subunit AP-3 β2 to the M5 i3 loop, we examined trafficking of M5wt and M5Δ receptors expressed exogenously in cultured embryonic rat cortico-hippocampal neurons. In contrast to experiments performed in HEK-293T cells, we observed in neuronal cultures deficient endocytic recycling of M5Δ receptors as compared with M5wt (Figure 5C and D). Basal surface expression of M5Δ receptors was increased in comparison to M5wt in these experiments (Figure 5E). However, the deficient recycling of M5Δ receptors was independent of expression levels, as shown in experiments in which basal surface density of M5wt and M5Δ receptors was equal (Supplementary Figure S5). Importantly, the ΔABD mutation did not disrupt phospholipid, Ca2+, or mitogen-activated protein kinase signalling through M5 (Supplementary Figure S4B–D).

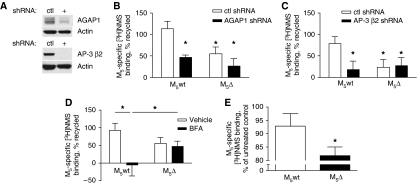

To confirm a role for AGAP1 and AP-3b in the endocytic recycling of M5 in neurons, we performed [3H]NMS trafficking experiments in which endogenous AGAP1 and AP-3 β2 proteins were knocked down through expression of short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) (Figure 6A). In both cases, recycling of M5wt, but not M5Δ receptors, was reduced compared with neuronal cultures expressing non-targeting shRNA (Figure 6B and C). Basal cell surface expression of M5wt and M5Δ receptors was not affected by either AGAP1 or AP-3 β2 knockdown, whereas knockdown of the AP-3a/AP-3b subunit δ-adaptin reduced surface expression of both M5wt and M5Δ receptors (Supplementary Figure S6). To provide further evidence for an AP-3-dependent mechanism of endocytic recycling for M5 receptors, we used the Arf GEF inhibitor brefeldin-A (BFA; 10 μg/ml) to acutely inhibit the function of AP-3 (Donaldson et al, 1992; Ooi et al, 1998; Salazar et al, 2004). BFA pre-incubation abolished endocytic recycling of the M5wt receptor, but had no effect on M5Δ (Figure 6D). Finally, in neuronal cultures subjected to chronic agonist stimulation (10 μM CCh, 4 days), we observed a significantly greater reduction in the density of cell surface M5Δ receptors as compared with M5wt (Figure 6E). This result suggested that in neurons, AGAP1/AP-3b-mediated endocytic recycling is required for the maintenance of surface M5 expression under conditions of sustained receptor stimulation.

Figure 6.

AGAP1 and AP-3b are required for efficient endocytic recycling of M5 receptors in cultured embryonic rat cortico-hippocampal neurons. (A) Representative immunoblots of AGAP1 and AP-3 β2 knockdown by target-specific (+) or non-targeting control (ctl) shRNA in nucleofected primary neuron cultures. Lower panels, actin loading controls. (B–D) Neurons were nucleofected with M5wt, M5Δ, or empty vector control plasmids and cultured for 13 days. Cells were treated with 0.1 mM CCh for 30 min with or without a subsequent 60 min washout, or were left untreated. Cell surface muscarinic receptors were assayed by [3H]NMS radioligand binding and M5-specific signal was calculated. Data are expressed as a percent of CCh-internalized receptors recycled after 1 h washout. *P<0.05, one-tailed Student's t-test. (B, C) Neurons were conucleofected with targeting or non-targeting control shRNA plasmids in addition to M5 expression plasmids (B) n=4; (C) n=5. (D) Nucleofected neurons were pre-treated with brefeldin-A (BFA; 10 μg/ml) or vehicle for 2 h before CCh treatment (n=6). (E) Neurons were nucleofected as in (D). Cultures were treated for 4 days with or without 10 μM CCh and were assayed for cell-surface M5 receptor binding as described. M5 surface density data are expressed as percent of untreated control. *P<0.05, two-tailed paired Student's t-test (n=3). Error bars for all graphs represent s.e.m.

Potentiation of striatal dopamine release by presynaptic M5 receptors is AGAP1 and AP-3 dependent

The striatum is characterized by the presence of tonically active, extensively arborized cholinergic interneurons (TANs), and has the highest ACh tone found in the CNS (Zhou et al, 2002; Pisani et al, 2007). Activation of M5 receptors localized to dopaminergic neuron terminals in the striatum functions to potentiate dopamine release (Zhang et al, 2002b; Martire et al, 2007). We hypothesized that, as a result of deficient endocytic recycling, disruption of the AGAP1/M5 interaction would lead to downregulation of M5 surface density at dopaminergic neuron terminals, and in turn inhibit ACh's potentiation of activity-dependent dopamine release. As elimination of AGAP1 expression in vivo would likely result in a generalized perturbation of Arf1-dependent secretory pathway function (D'Souza-Schorey and Chavrier, 2006), we tested this hypothesis by generating a mutant ‘knock-in' mouse (CHRM5Δ/Δ) in which the M5Δ receptor was expressed in place of wild-type M5. CHRM5Δ/Δ animals were healthy and viable, and M5Δ mRNA was expressed in the ventral midbrain, as expected (Supplementary Figure S7).

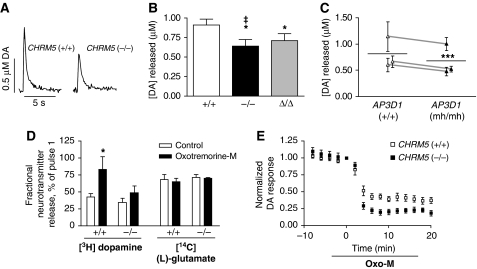

We used fast-scan cyclic voltammetry (CV) to study the evoked release of endogenous dopamine from wild-type and mutant (CHRM5−/− and CHRM5Δ/Δ) mouse brain slices, a preparation in which local cytoarchitecture is intact and the tonic activity of TANs is maintained (Bennett and Wilson, 1998). Stimulated release of dopamine in the dorsolateral striatum of CHRM5−/− animals was reduced as compared with wild-type controls, consistent with a release-potentiating function of dopaminergic terminal M5 receptors (Figure 7A and B). Notably, we also observed decreased dopamine release in CHRM5Δ/Δ animals compared with controls (Figure 7B). We next investigated the role of AP-3 in stimulated dopamine release through use of the spontaneous AP3D1 null-mutant mocha (mh) mouse, in which lack of δ-adaptin results in the absence of all AP-3a and AP-3b subunits (Kantheti et al, 1998) (Supplementary Figure S8A). We observed a significant decrease in evoked dopamine release in dorsolateral striatum of mh/mh animals as compared with wild-type controls (Figure 7C). Taken together, these data support a model in which AGAP1/AP-3-mediated endocytic recycling is required for the long-term maintenance of presynaptic M5 function in the striatum.

Figure 7.

M5-mediated potentiation of striatal dopamine release requires AGAP1 interaction and AP-3 activity. (A) Representative dopamine (DA) release traces as measured by fast-scan cyclic voltammetry after electrical stimulation. (B) Evoked dopamine release from CHRM5−/−, CHRM5Δ/Δ or wild-type control mouse striatal slices was measured by fast-scan cyclic voltammetry. Data are displayed as peak instantaneous dopamine concentrations, and represent 12–28 readings from 3 to 8 animals. ‡,*P<0.05, two-tailed Student's t-test versus wild-type; *P<0.05, one-tailed Student's t-test versus wild-type. (C) Evoked dopamine release from mocha (AP3D1mh/mh) or wild-type control mouse striatal slices was measured by fast-scan cyclic voltammetry. Data are displayed as mean peak instantaneous dopamine concentrations from three pairs of mh/mh and age-matched +/+ animals (top to bottom: age=4, 10, and 3 months; n=3–4 for each animal). ***P<0.001, paired two-tailed Student's t-test. Error bars for all graphs represent s.e.m. (D) Striatal synaptosomes prepared from CHRM5−/− or wild-type control mice were simultaneously loaded with [3H]dopamine and [14C](L)-glutamate. Stimulated neurotransmitter outflow was measured after two K+ pulses, the second in the presence or absence of 100 μM oxotremorine-M (oxo-M). Data are displayed as percentage ratios of pulse 2/pulse 1. *P<0.05, two-way ANOVA/Bonferroni post-test (n⩾3). (E) Evoked dopamine release from CHRM5−/− or wild-type control mouse striatal slices was measured at 2-min intervals by fast-scan cyclic voltammetry before and after addition of 10 μM oxo-M to the perfusion bath. Data are normalized to release at time=0 and represent data from seven slices for each genotype derived from 3–4 animals.

To address the specificity of M5's stimulatory action on dopamine release, we measured neurotransmitter outflow from isolated striatal nerve terminals (synaptosomes) prepared from wild-type and CHRM5−/− mice. As expected, incubation of wild-type, but not CHRM5−/− synaptosomes with the non-selective muscarinic agonist oxotremorine-M (oxo-M; 100 μM) significantly potentiated K+-stimulated release of [3H]dopamine, whereas release of the excitatory neurotransmitter [14C](L)-glutamate was not affected by either genotype or oxo-M incubation (Figure 7D). In contrast, bath application of oxo-M (10 μM) to striatal brain slices resulted in a strong, persistent decrease in evoked dopamine release as measured by CV (Figure 7E; Supplementary Figure S8B). The magnitude of this decrease was enhanced in CHRM5−/− animals as compared with wild-type controls, consistent with the dopamine release-potentiating function of presynaptic M5 receptors (Figure 7E; Supplementary Figure S8B). However, oxo-M treatment did not differentially depress stimulated dopamine release in CHRM5Δ/Δ or mh/mh striata as compared with wild-type controls in CV experiments (Supplementary Figure S8C and D).

Discussion

MRs undergo rapid desensitization through endocytic sequestration following activation by agonists (Tolbert and Lameh, 1996; Volpicelli et al, 2001; Delaney et al, 2002; Popova and Rasenick, 2004). Without a mechanism capable of efficiently recycling internalized MRs to the plasma membrane, sustained stimulatory action could result in long-term downregulation of signalling potency by virtue of decreased cell surface receptor density. In the striatum, the function of M5 receptors present at dopaminergic neuron terminals is particularly dependent on such recycling, as cholinergic tone is high. Here, we identify a novel AGAP1 interaction-dependent mechanism responsible for the endocytic recycling of M5 receptors in neurons. As M5-specific antibodies are not available, we developed an exogenous expression system in cultured neurons in which cell-surface M5 density was monitored by radioligand binding. Our experiments revealed a 10–20% reduction in surface M5 density after agonist treatment. Washout resulted in a complete return of surface M5 sites, and was inhibited by elimination of AGAP1/M5 binding, knockdown of AGAP1 or AP-3 β2, or blockade of AP-3 function. As agonist treatment was assayed at an equilibrium time point, these data are consistent with an AGAP1/AP-3b-dependent recycling mechanism, the rate of which is sufficient to counterbalance activity-induced endocytosis in this system. We also observed that basal surface density of exogenously expressed M5Δ receptors was larger than that of M5wt. This increase was apparently unrelated to activity of AGAP1, AP-3a or AP-3b. The mechanisms responsible for this quantitative phenotype (as opposed to the qualitative recycling phenotype) have not been determined, but may be related to either an increased synthetic rate or differential transfection/nucleofection efficiency of M5Δ compared with M5wt in our overexpression systems.

Our model of M5 recycling implies that AGAP1, in addition to its characterized Arf1GAP activity, possesses an intrinsic cargo-recognition ability and functions as part of an AP-3-containing membrane vesicle coat complex. Such activity has not previously been reported for AGAP1. In support of this model, other ArfGAPs have been shown to function as coat complex members (Nie and Randazzo, 2006); ACAP1, for example, was found to promote the recycling of internalized TfRs through recognition of sorting signals (Dai et al, 2004). Although it is unclear whether AGAP1 binds to the M5 i3 loop as part of a pre-existing, membrane-associated AP-3 complex, or if AGAP1 association with M5 serves to recruit AP-3 to the receptor, the latter possibility offers an intriguing functional parallel to β-arrestin. Stimulation-dependent phosphorylation of plasma membrane GPCRs induces binding of β-arrestin; β-arrestin, in turn, is able to recruit binding of the adaptor complex AP-2, which leads to clathrin coat assembly and receptor endocytosis (Lohse et al, 1990; Moore et al, 2007). This mechanism has a major function in GPCR desensitization and downregulation, and can be regulated, by virtue of β-arrestin binding strength, through alterations in GPCR phosphorylation levels (Premont and Gainetdinov, 2007; Hanyaloglu and von Zastrow, 2008). The M5 ABD contains a predicted serine phosphorylation substrate (Blom et al, 1999); although alanine mutation of this residue did not effect AGAP1 binding in the Y2H system (Supplementary Figure S9A), investigation of the phosphorylation dependence of AGAP1/M5 binding in vivo may yield important insights into the regulation of AGAP1/AP-3-mediated M5 traffic.

Our results indicate that the ABD present in the M5 i3 loop comprises an endocytic recycling signal sequence. This region displayed no homology with sequences present in the other four MRs, and binding of AGAP1 to the i3 loops of M1 through M4 was not observed, suggesting that this recycling mechanism is specific to the M5 MR subtype. In addition, known recycling motifs from other GPCRs were absent from the ABD region (Hanyaloglu and von Zastrow, 2008). Interestingly, alanine mutation of two groups of highly conserved residues within the ABD region eliminated or decreased binding of AGAP1 in Y2H and in vitro assays (Supplementary Figure S9). The sequence of these motifs resembled, but did not exactly conform to recognized [D/E]XXXL[L/I] and YXXΦ targeting signals commonly present on GPCR i3 loop or C-terminal tail regions (Bonifacino and Traub, 2003). To date, relatively few recycling signal sequences have been identified; thus, further examination of the AGAP1-binding motif will expand our understanding of the structural determinants of GPCR recycling, and could help identify other GPCRs whose endocytic traffic is AGAP1 dependent.

As AGAP1-dependent recycling of M5 was neuron specific and was inhibited by AP-3 β2 knockdown, we propose that AP-3b possesses a previously unrecognized function in the endocytic recycling pathway. The following observations suggest that this recycling mechanism may have an important function in axons, a compartment in which non-somatodendritic trafficking pathways are present (Yap et al, 2008): (1) AP-3b is known to target proteins to synaptic vesicles and to presynaptic compartments (Nakatsu et al, 2004; Salazar et al, 2005), (2) AP-3-positive puncta were observed in synapse-adjacent compartments of axons in cultured hippocampal neurons (as well as in soma and dendrites) (Supplementary Figure S10A), and (3) colocalization of endocytosed M5-GFP receptors with AGAP1 was observed mainly in axon-like processes. We speculate that M5 is targeted to the recycling pathway by sorting from the endocytic recycling compartment to AGAP1/AP-3b-positive endosomes, similar to the mechanism observed for sorting of LAMP-1 to lysosomes by AP-3a (Peden et al, 2004). Delivery of M5 receptors to the plasma membrane is not likely to proceed through synaptic vesicles, as M5-GFP protein was not detected in synaptic vesicles isolated by subcellular fractionation (data not shown).

Stimulation by ACh of Gαq-coupled M5 receptors located at dopaminergic terminals in the striatum potentiates dopamine release through phosphatidylinositol bisphosphate hydrolysis, leading to KCNQ2/3 channel inhibition and membrane depolarization (Yamada et al, 2001; Zhang et al, 2002b, 2003; Martire et al, 2007). We hypothesized that, in the absence of AGAP1/AP-3b-mediated endocytic recycling, reduced cell surface M5 levels would result in decreased M5 signalling magnitude and a subsequent reduction in ACh-potentiated dopamine release. Because of a lack of available tools capable of quantitating M5 receptors in vivo, we could not directly address cell surface M5 receptor density. Similarly, examination of desensitization characteristics of proximal M5-mediated signalling events in neurons was precluded by the absence of M5-selective agonists and poor signal-to-background characteristics of cortico-hippocampal neurons exogenously expressing M5 receptors (data not shown). Nevertheless, we indeed observed a decrease in stimulated dopamine release in the striata of CHRM5Δ/Δ and mh/mh animals as compared with controls, consistent with a greater surface density of M5 receptors in wild-type animals.

We found stimulation of M5 receptors with oxo-M to potentiate evoked dopamine release in both striatal synaptosome superfusion and brain slice CV experiments. In the latter case, this potentiation was observed in the context of strong oxo-M-induced reduction of evoked dopamine release. As ACh release from TANs provides a tonic excitation of DA release (Zhou et al, 2001; Zhang and Sulzer, 2004), this reduction appears to result from inhibition of TAN activity by non-M5 MRs (Yan and Surmeier, 1996; Zhang et al, 2002a). The overall oxo-M-induced reduction in striatally evoked dopamine release, despite the excitatory M5 component, was most likely because of the preserved local synaptic environment, as glutamate, nicotinic and GABAergic receptors affect the probability of synaptic vesicle fusion from dopamine terminals (Schmitz et al, 2003). However, application of oxo-M did not differentially inhibit evoked dopamine release in CHRM5Δ/Δ and mh/mh striatal slices. Thus, although as expected, the M5 null mouse shows no oxo-M facilitation, the lower number of active presynaptic M5 receptors remaining in CHRM5Δ/Δ animals decreases tonic ACh excitation but can still provide proportional levels of agonist response.

We note that although AP-3-positive puncta were present in the axons of cultured midbrain dopaminergic neurons (Supplementary Figure S10B), M5 recycling may require retrograde transport. As our preparations did not include intact nigrostriatal neurons, acute recycling events may have been blocked. In addition, mocha mice exhibit alterations in presynaptic morphology and defective GABA neurotransmission (Nakatsu et al, 2004; Newell-Litwa et al, 2010), potentially complicating interpretation of our dopamine release data. Finally, M5 receptors localized to somatodendritic compartments of midbrain dopaminergic neurons also function to stimulate dopamine release (Yeomans et al, 2001; Forster et al, 2002; Miller and Blaha, 2005). Indeed, activation of somatodendritic M5 receptors expressed in ventral tegmental area neurons results in prolonged release of dopamine (Forster et al, 2002), suggesting that M5 endocytic recycling may have a role in sustaining sensitivity to ACh.

The CHRM5−/− mouse exhibits decreased sensitivity to amphetamine and morphine, reduced cocaine self-administration and altered sensorimotor gating behaviours (Basile et al, 2002; Wang et al, 2004; Thomsen et al, 2005; Araya et al, 2006). Our results suggest that, by reducing cell surface M5 receptor density, abrogation of AGAP1/AP-3b-mediated M5 recycling (as occurs in the CHRM5Δ/Δ mouse) may result in a similar hypodopaminergic phenotype. Inhibition of M5/AGAP1 interaction could serve as a pharmacologic target for the reduction of hyperactive dopamine release, which in the mesolimbic system has been linked to symptoms of schizophrenia (Guillin et al, 2007). Conversely, agents capable of potentiating the M5/AGAP1 interaction could, by increasing striatal dopamine release, prove useful in the treatment of Parkinson's disease. As M5 receptors also function in cerebral arteries and arterioles to regulate blood flow (Yamada et al, 2001), modulation of neuron-specific AGAP1/AP-3b-mediated M5 recycling should offer greater therapeutic selectivity over M5-targeted drugs for the treatment of dopamine system disorders.

Finally, our observation of a physical interaction between M5, AGAP1 and the AP-3-associated BLOC-1 protein dysbindin offers an intriguing connection to schizophrenia, as the genes encoding these proteins (CHRM5, AGAP1/CENTG2, and DTNBP1) have been linked to susceptibility to this disorder (Schwab et al, 2003; De Luca et al, 2004; Talbot et al, 2004; Shi et al, 2009). Given the role of M5 in the regulation of dopamine release and the long-hypothesized connection between aberrant dopaminergic system function and schizophrenia, further study of AGAP1/AP-3b-mediated M5 trafficking in the context of this disorder is warranted.

Materials and methods

Rodent strains

All procedures involving animals were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Rockefeller University, Columbia University and Weill Cornell Medical College Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees. Female adult (3–6 months old) timed pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats were obtained from Charles River Labs or Taconic Labs. C57Bl/6 mice were obtained from Charles River Labs. The CHRM5−/− strain was a kind gift from Jürgen Wess (Yamada et al, 2001) (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease, Bethesda, MD) and was extensively backcrossed (>10 generations) onto the C57Bl/6 background before use. STOCK gr+/+ Ap3d1mh/J mice carrying the mocha allele (mh), a spontaneous null mutation of the AP3D1 gene (Lane and Deol, 1974; Kantheti et al, 1998), were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. In this strain, the mh allele is maintained on a mixed background in repulsion to the pigmentation mutant grizzled (gr) allele. Mice were maintained as heterozygotes, as mh homozygotes were observed to be infertile. The CHRM5Δ/Δ strain was generated by Ozgene Pty. Ltd (Bentley, Australia) as described in Supplementary data.

Yeast two-hybrid analysis

Yeast two-hybrid protein–protein interaction experiments were performed in a GAL4-based system as described earlier (Flajolet et al, 2000). For the M5 screen, the yeast strain CG1945 was transformed with a pAS2-derived bait plasmid containing the full-length M5 i3 loop cDNA, and was mated with Y187 strain yeast transformed with pACT2-rat brain cDNA library prey plasmid (Clontech). Diploid cells were cultured on selective agar media, and after 4 days, lacZ reporter gene activity was detected in HIS3+ colonies by 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl β-D-galactoside (X-Gal; Calbiochem) overlay assay. For binary yeast two-hybrid experiments, Y187 yeast was cotransformed with bait and prey plasmids and lacZ activity was detected by X-Gal membrane lift assay.

GST pull-down assays

Recombinantly expressed GST fusion proteins were purified and immobilized on Glutathione Sepharose 4B resin (GE Life Sciences) and used as baits in pull-down experiments with tissue culture cell or rat brain lysates, or with in vitro synthesized [35S]-AGAP1520−861 protein essentially as described earlier (Flajolet et al, 2008) and as detailed in Supplementary data.

Coimmunoprecipitation

Coimmunoprecipitation of AP-3 components with myc-tagged AGAP1 was performed as described earlier (Nie et al, 2003). NIH-3T3 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% (v/v) bovine calf serum and transfected with expression plasmids encoding full-length or truncated AGAP1-myc using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Cells were lysed in 3T3 buffer (25 mM Tris, pH=8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 1% (v/v) protease inhibitor cocktail III (Calbiochem), 0.5 mM PMSF) with three freeze-thaw cycles in LN2. Lysates were cleared by centrifugation, and then incubated with anti-myc 9E10 agarose (Covance) for 14 h at 4°C. The affinity matrix was washed three times with 3T3 buffer and proteins were eluted with LDS sample buffer, separated by SDS–PAGE, and detected by immunoblot.

Immunoblotting

Proteins were analysed using standard SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting techniques as described in Supplementary data. The following primary antibodies and dilutions were used: actin (1:10 000, Abcam); α-adaptin (1:1000, BD Transduction Labs); γ-adaptin (1:5000, BD); AP-3 σ1/adaptin σ3A (1:250, BD); δ-adaptin SA4 (1:1000, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank); AP-2 β1/adaptin β2 (1:10 000, BD); AP-3 β2/β-NAP (1:500, BD); AP-3 μ1/p47A (1:250, BD); AGAP1 (1:1000, a kind gift from S Meurer, University of Frankfurt School of Medicine); or c-Myc 9E10 (1:1000, Covance).

Phospholipid-binding assay

The TNT T7 Quick coupled transcription/translation system (Promega) was used to synthesize in vitro [35S]methionine-labelled full-length and truncated AGAP1 proteins from AGAP1 cDNAs (full-length and 552–861 truncation mutant) cloned in the T7 promoter-containing pcDNA3.1 vector. Phospholipid dot-blot arrays (PIP strips; Echelon Biosciences) were blocked 1 h at 24°C in PIP-blocking buffer (TBS pH=8, 3% (w/v) fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin, 0.1% (v/v) Tween-20). Arrays were incubated with [35S]methionine-labelled proteins in PIP-blocking buffer for 3 h, washed six times for 5 min in PIP-blocking buffer, dried, and imaged by storage phosphor autoradiography.

In situ hybridization

Expression of AGAP1 mRNA in wild-type C57Bl/6 mouse brain slices was analysed by in situ hybridization as described earlier (Zhou et al, 2010) and as detailed in Supplementary data. A 772-bp region of the AGAP1 3′ UTR was amplified from a mouse brain cDNA library by PCR (forward 5′-AAG TTG CAA CCA CCA CGT GAG TCC CTC AGT TCC CTC, reverse 5′-CCA AGT AAG GGG ACT GAA GTC AAA TAA TAC CCA GC) and used as template to prepare the [33P]-labelled riboprobe.

Immunocytochemistry

Primary embryonic rat hippocampal neurons were prepared and transfected with expression plasmids as described in Supplementary data. After treatment with or without 1 mM CCh, neurons were fixed in 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde/4% (w/v) sucrose in PBS for 30 min at 24°C. For immunostaining of AGAP1-myc, neurons were pre-extracted before fixation with 0.03% (w/v) saponin in cytosolic buffer (25 mM HEPES-KOH, pH=7.4, 25 mM KCl, 2.5 mM Mg acetate, 5 mM EGTA, 150 mM K-glutamate) (Morris and Cooper, 2001) for 30 sec at 37°C, rinsed at 37°C with intracellular buffer, and fixed for 30 min at 24°C with 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde in cytosolic buffer. Fixed cells were permeabilized with 0.25% (v/v) Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min, rinsed in PBS, and blocked for 30 min in antibody diluent (2% (w/v) BSA, 0.05% (v/v) Triton X-100, 0.02% (w/v) NaN3 in PBS), followed by incubation with the following primary antibodies diluted in antibody diluent: c-Myc 9E10 (1:500); δ-adaptin SA4 (1:100); rabbit GFP (1:10 000, Abcam); synapsin I (1:500, Abcam); or TfR (1:500, Zymed). Coverslips were then incubated with appropriate Alexa 488 or Alexa 568 (Invitrogen), or Cy3 (Jackson Immunoresearch)-conjugated secondary antibodies. After washing, coverslips were mounted in Fluoromount-G (Southern Biotech) and imaged with an LSM510 confocal system (Zeiss Microimaging) using either 40 × 1.3NA or 100 × 1.4NA oil objectives. Quantification of M5-GFP and AGAP1-myc colocalization was performed in NIH ImageJ using the intensity correlation analysis and colocalization threshold plugins as described in Supplementary data.

Radioligand-binding assays

Surface density of M5-binding sites in intact HEK-293T or primary cortico-hippocampal neurons was assayed by radioligand binding using the cell-impermeant muscarinic antagonist [N-methyl-3H]-scopolamine (Perkin Elmer) as described in Supplementary data. The muscarinic antagonist AF-DX 384, which displays at least 10-fold lower affinity for M5 compared with M1–M4 receptors (Dorje et al, 1991), was included in the cortico-hippocampal neuron-binding assays at 5 μM to distinguish exogenously expressed M5 from endogenous MRs (predominantly M1/M2 subtype) (Oki et al, 2005) (Supplementary Figure S11). RNAi-mediated knockdown in embryonic cortico-hippocampal cultures was performed using gene-specific shRNAs expressed from the pSUPER.puro vector (Oligoengine) followed by puromycin selection (1 μg/ml).

Dopamine release experiments

Experiments examining stimulated release of [3H]dopamine from striatal synaptosomes used a superfusion system previously described (Westphalen and Hemmings, 2003), which measured dual pulses of K+-evoked release of [3H]dopamine and [14C](L)-glutamate (Perkin Elmer) in the absence (first pulse) or presence (second pulse) of 100 μM oxotremorine-M (Tocris). Fast-scan cyclic voltammetric measurement of endogenous dopamine release was performed as previously described (Zhang and Sulzer, 2003). Measurements were performed in dorsolateral striatum areas of coronal brain slices prepared from CHRM5−/−, CHRM5Δ/Δ, mocha (mh+/mh+) or wild-type control (C57Bl/6 or +gr/+gr) animals as indicated. Details of dopamine release experimental procedures are included in Supplementary data.

Statistical analysis

Statistical differences were determined by Student's t-test or two-way ANOVA as indicated. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to A Nairn, Y Sagi and H Rebholz for critical reading of the manuscript, M Zhou for assistance with in situ hybridization experiments and to M Kazmi for assistance with Ca2+ signalling measurements. This work was supported in part by US National Institutes of Health grant DA 10044 (to PG) and Department of Defense/US Army Medical Research Acquisition Activity Grant W81XWH-08-1-0111 (to PG). Funding for JEL-O was provided in part by NIDA-Basic Neuroscience Training Grant T32DA016224.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Araya R, Noguchi T, Yuhki M, Kitamura N, Higuchi M, Saido TC, Seki K, Itohara S, Kawano M, Tanemura K, Takashima A, Yamada K, Kondoh Y, Kanno I, Wess J, Yamada M (2006) Loss of M5 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors leads to cerebrovascular and neuronal abnormalities and cognitive deficits in mice. Neurobiol Dis 24: 334–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basile AS, Fedorova I, Zapata A, Liu X, Shippenberg T, Duttaroy A, Yamada M, Wess J (2002) Deletion of the M5 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor attenuates morphine reinforcement and withdrawal but not morphine analgesia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 11452–11457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett BD, Wilson CJ (1998) Synaptic regulation of action potential timing in neostriatal cholinergic interneurons. J Neurosci 18: 8539–8549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom N, Gammeltoft S, Brunak S (1999) Sequence and structure-based prediction of eukaryotic protein phosphorylation sites. J Mol Biol 294: 1351–1362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumstein J, Faundez V, Nakatsu F, Saito T, Ohno H, Kelly RB (2001) The neuronal form of adaptor protein-3 is required for synaptic vesicle formation from endosomes. J Neurosci 21: 8034–8042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonifacino JS, Traub LM (2003) Signals for sorting of transmembrane proteins to endosomes and lysosomes. Annu Rev Biochem 72: 395–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Souza-Schorey C, Chavrier P (2006) ARF proteins: roles in membrane traffic and beyond. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 7: 347–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai J, Li J, Bos E, Porcionatto M, Premont RT, Bourgoin S, Peters PJ, Hsu VW (2004) ACAP1 promotes endocytic recycling by recognizing recycling sorting signals. Dev Cell 7: 771–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Luca V, Wang H, Squassina A, Wong GW, Yeomans J, Kennedy JL (2004) Linkage of M5 muscarinic and alpha7-nicotinic receptor genes on 15q13 to schizophrenia. Neuropsychobiology 50: 124–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney KA, Murph MM, Brown LM, Radhakrishna H (2002) Transfer of M2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors to clathrin-derived early endosomes following clathrin-independent endocytosis. J Biol Chem 277: 33439–33446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell'Angelica EC, Shotelersuk V, Aguilar RC, Gahl WA, Bonifacino JS (1999) Altered trafficking of lysosomal proteins in Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome due to mutations in the beta 3A subunit of the AP-3 adaptor. Mol Cell 3: 11–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Pietro SM, Falcon-Perez JM, Tenza D, Setty SR, Marks MS, Raposo G, Dell'Angelica EC (2006) BLOC-1 interacts with BLOC-2 and the AP-3 complex to facilitate protein trafficking on endosomes. Mol Biol Cell 17: 4027–4038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson JG, Finazzi D, Klausner RD (1992) Brefeldin A inhibits Golgi membrane-catalysed exchange of guanine nucleotide onto ARF protein. Nature 360: 350–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorje F, Wess J, Lambrecht G, Tacke R, Mutschler E, Brann MR (1991) Antagonist binding profiles of five cloned human muscarinic receptor subtypes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 256: 727–733 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flajolet M, Rotondo G, Daviet L, Bergametti F, Inchauspe G, Tiollais P, Transy C, Legrain P (2000) A genomic approach of the hepatitis C virus generates a protein interaction map. Gene 242: 369–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flajolet M, Wang Z, Futter M, Shen W, Nuangchamnong N, Bendor J, Wallach I, Nairn AC, Surmeier DJ, Greengard P (2008) FGF acts as a co-transmitter through adenosine A(2A) receptor to regulate synaptic plasticity. Nat Neurosci 11: 1402–1409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster GL, Yeomans JS, Takeuchi J, Blaha CD (2002) M5 muscarinic receptors are required for prolonged accumbal dopamine release after electrical stimulation of the pons in mice. J Neurosci 22: RC190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godi A, Di Campli A, Konstantakopoulos A, Di Tullio G, Alessi DR, Kular GS, Daniele T, Marra P, Lucocq JM, De Matteis MA (2004) FAPPs control Golgi-to-cell-surface membrane traffic by binding to ARF and PtdIns(4)P. Nat Cell Biol 6: 393–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillin O, Abi-Dargham A, Laruelle M (2007) Neurobiology of dopamine in schizophrenia. Int Rev Neurobiol 78: 1–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanyaloglu AC, von Zastrow M (2008) Regulation of GPCRs by endocytic membrane trafficking and its potential implications. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 48: 537–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn RA, Bruford E, Inoue H, Logsdon JM Jr, Nie Z, Premont RT, Randazzo PA, Satake M, Theibert AB, Zapp ML, Cassel D (2008) Consensus nomenclature for the human ArfGAP domain-containing proteins. J Cell Biol 182: 1039–1044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantheti P, Qiao X, Diaz ME, Peden AA, Meyer GE, Carskadon SL, Kapfhamer D, Sufalko D, Robinson MS, Noebels JL, Burmeister M (1998) Mutation in AP-3 delta in the mocha mouse links endosomal transport to storage deficiency in platelets, melanosomes, and synaptic vesicles. Neuron 21: 111–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane PW, Deol MS (1974) Mocha, a new coat color and behavior mutation on chromosome 10 of the mouse. J Hered 65: 362–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefrancois S, Janvier K, Boehm M, Ooi CE, Bonifacino JS (2004) An ear-core interaction regulates the recruitment of the AP-3 complex to membranes. Dev Cell 7: 619–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmon MA (2004) Pleckstrin homology domains: not just for phosphoinositides. Biochem Soc Trans 32 (Part 5): 707–711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Zhang Q, Oiso N, Novak EK, Gautam R, O'Brien EP, Tinsley CL, Blake DJ, Spritz RA, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Amato D, Roe BA, Starcevic M, Dell'Angelica EC, Elliott RW, Mishra V, Kingsmore SF, Paylor RE, Swank RT (2003) Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome type 7 (HPS-7) results from mutant dysbindin, a member of the biogenesis of lysosome-related organelles complex 1 (BLOC-1). Nat Genet 35: 84–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodowski DT, Pitcher JA, Capel WD, Lefkowitz RJ, Tesmer JJ (2003) Keeping G proteins at bay: a complex between G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 and Gbetagamma. Science 300: 1256–1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohse MJ, Benovic JL, Codina J, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ (1990) beta-Arrestin: a protein that regulates beta-adrenergic receptor function. Science 248: 1547–1550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martire M, D'Amico M, Panza E, Miceli F, Viggiano D, Lavergata F, Iannotti FA, Barrese V, Preziosi P, Annunziato L, Taglialatela M (2007) Involvement of KCNQ2 subunits in [3H]dopamine release triggered by depolarization and pre-synaptic muscarinic receptor activation from rat striatal synaptosomes. J Neurochem 102: 179–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meurer S, Pioch S, Wagner K, Muller-Esterl W, Gross S (2004) AGAP1, a novel binding partner of nitric oxide-sensitive guanylyl cyclase. J Biol Chem 279: 49346–49354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AD, Blaha CD (2005) Midbrain muscarinic receptor mechanisms underlying regulation of mesoaccumbens and nigrostriatal dopaminergic transmission in the rat. Eur J Neurosci 21: 1837–1846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore CA, Milano SK, Benovic JL (2007) Regulation of receptor trafficking by GRKs and arrestins. Annu Rev Physiol 69: 451–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris SM, Cooper JA (2001) Disabled-2 colocalizes with the LDLR in clathrin-coated pits and interacts with AP-2. Traffic 2: 111–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatsu F, Ohno H (2003) Adaptor protein complexes as the key regulators of protein sorting in the post-Golgi network. Cell Struct Funct 28: 419–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatsu F, Okada M, Mori F, Kumazawa N, Iwasa H, Zhu G, Kasagi Y, Kamiya H, Harada A, Nishimura K, Takeuchi A, Miyazaki T, Watanabe M, Yuasa S, Manabe T, Wakabayashi K, Kaneko S, Saito T, Ohno H (2004) Defective function of GABA-containing synaptic vesicles in mice lacking the AP-3B clathrin adaptor. J Cell Biol 167: 293–302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newell-Litwa K, Chintala S, Jenkins S, Pare JF, McGaha L, Smith Y, Faundez V (2010) Hermansky-Pudlak protein complexes, AP-3 and BLOC-1, differentially regulate presynaptic composition in the striatum and hippocampus. J Neurosci 30: 820–831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newell-Litwa K, Seong E, Burmeister M, Faundez V (2007) Neuronal and non-neuronal functions of the AP-3 sorting machinery. J Cell Sci 120 (Part 4): 531–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie Z, Boehm M, Boja ES, Vass WC, Bonifacino JS, Fales HM, Randazzo PA (2003) Specific regulation of the adaptor protein complex AP-3 by the Arf GAP AGAP1. Dev Cell 5: 513–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie Z, Fei J, Premont RT, Randazzo PA (2005) The Arf GAPs AGAP1 and AGAP2 distinguish between the adaptor protein complexes AP-1 and AP-3. J Cell Sci 118 (Part 15): 3555–3566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie Z, Randazzo PA (2006) Arf GAPs and membrane traffic. J Cell Sci 119 (Part 7): 1203–1211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie Z, Stanley KT, Stauffer S, Jacques KM, Hirsch DS, Takei J, Randazzo PA (2002) AGAP1, an endosome-associated, phosphoinositide-dependent ADP-ribosylation factor GTPase-activating protein that affects actin cytoskeleton. J Biol Chem 277: 48965–48975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oki T, Takagi Y, Inagaki S, Taketo MM, Manabe T, Matsui M, Yamada S (2005) Quantitative analysis of binding parameters of [3H]N-methylscopolamine in central nervous system of muscarinic acetylcholine receptor knockout mice. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 133: 6–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooi CE, Dell'Angelica EC, Bonifacino JS (1998) ADP-Ribosylation factor 1 (ARF1) regulates recruitment of the AP-3 adaptor complex to membranes. J Cell Biol 142: 391–402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peden AA, Oorschot V, Hesser BA, Austin CD, Scheller RH, Klumperman J (2004) Localization of the AP-3 adaptor complex defines a novel endosomal exit site for lysosomal membrane proteins. J Cell Biol 164: 1065–1076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisani A, Bernardi G, Ding J, Surmeier DJ (2007) Re-emergence of striatal cholinergic interneurons in movement disorders. Trends Neurosci 30: 545–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popova JS, Rasenick MM (2004) Clathrin-mediated endocytosis of m3 muscarinic receptors. Roles for Gbetagamma and tubulin. J Biol Chem 279: 30410–30418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Premont RT, Gainetdinov RR (2007) Physiological roles of G protein-coupled receptor kinases and arrestins. Annu Rev Physiol 69: 511–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter SL, Hall RA (2009) Fine-tuning of GPCR activity by receptor-interacting proteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 10: 819–830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar G, Craige B, Love R, Kalman D, Faundez V (2005) Vglut1 and ZnT3 co-targeting mechanisms regulate vesicular zinc stores in PC12 cells. J Cell Sci 118 (Part 9): 1911–1921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar G, Craige B, Styers ML, Newell-Litwa KA, Doucette MM, Wainer BH, Falcon-Perez JM, Dell'Angelica EC, Peden AA, Werner E, Faundez V (2006) BLOC-1 complex deficiency alters the targeting of adaptor protein complex-3 cargoes. Mol Biol Cell 17: 4014–4026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar G, Love R, Werner E, Doucette MM, Cheng S, Levey A, Faundez V (2004) The zinc transporter ZnT3 interacts with AP-3 and it is preferentially targeted to a distinct synaptic vesicle subpopulation. Mol Biol Cell 15: 575–587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar G, Zlatic S, Craige B, Peden AA, Pohl J, Faundez V (2009) Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome protein complexes associate with phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase type II alpha in neuronal and non-neuronal cells. J Biol Chem 284: 1790–1802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz Y, Benoit-Marand M, Gonon F, Sulzer D (2003) Presynaptic regulation of dopaminergic neurotransmission. J Neurochem 87: 273–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab SG, Knapp M, Mondabon S, Hallmayer J, Borrmann-Hassenbach M, Albus M, Lerer B, Rietschel M, Trixler M, Maier W, Wildenauer DB (2003) Support for association of schizophrenia with genetic variation in the 6p22.3 gene, dysbindin, in sib-pair families with linkage and in an additional sample of triad families. Am J Hum Genet 72: 185–190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J, Levinson DF, Duan J, Sanders AR, Zheng Y, Pe′er I, Dudbridge F, Holmans PA, Whittemore AS, Mowry BJ, Olincy A, Amin F, Cloninger CR, Silverman JM, Buccola NG, Byerley WF, Black DW, Crowe RR, Oksenberg JR, Mirel DB et al. (2009) Common variants on chromosome 6p22.1 are associated with schizophrenia. Nature 460: 753–757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbot K, Eidem WL, Tinsley CL, Benson MA, Thompson EW, Smith RJ, Hahn CG, Siegel SJ, Trojanowski JQ, Gur RE, Blake DJ, Arnold SE (2004) Dysbindin-1 is reduced in intrinsic, glutamatergic terminals of the hippocampal formation in schizophrenia. J Clin Invest 113: 1353–1363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taneichi-Kuroda S, Taya S, Hikita T, Fujino Y, Kaibuchi K (2009) Direct interaction of Dysbindin with the AP-3 complex via its mu subunit. Neurochem Int 54: 431–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen M, Woldbye DP, Wortwein G, Fink-Jensen A, Wess J, Caine SB (2005) Reduced cocaine self-administration in muscarinic M5 acetylcholine receptor-deficient mice. J Neurosci 25: 8141–8149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolbert LM, Lameh J (1996) Human muscarinic cholinergic receptor Hm1 internalizes via clathrin-coated vesicles. J Biol Chem 271: 17335–17342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpicelli LA, Lah JJ, Levey AI (2001) Rab5-dependent trafficking of the m4 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor to the plasma membrane, early endosomes, and multivesicular bodies. J Biol Chem 276: 47590–47598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Ng K, Hayes D, Gao X, Forster G, Blaha C, Yeomans J (2004) Decreased amphetamine-induced locomotion and improved latent inhibition in mice mutant for the M5 muscarinic receptor gene found in the human 15q schizophrenia region. Neuropsychopharmacology 29: 2126–2139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner DM, Levey AI, Brann MR (1990) Expression of muscarinic acetylcholine and dopamine receptor mRNAs in rat basal ganglia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87: 7050–7054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wess J, Blin N, Mutschler E, Bluml K (1995) Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors: structural basis of ligand binding and G protein coupling. Life Sci 56: 915–922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wess J, Eglen RM, Gautam D (2007) Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors: mutant mice provide new insights for drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov 6: 721–733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westphalen RI, Hemmings HC Jr (2003) Selective depression by general anesthetics of glutamate versus GABA release from solated cortical nerve terminals. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 304: 1188–1196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia C, Ma W, Stafford LJ, Liu C, Gong L, Martin JF, Liu M (2003) GGAPs, a new family of bifunctional GTP-binding and GTPase-activating proteins. Mol Cell Biol 23: 2476–2488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada M, Lamping KG, Duttaroy A, Zhang W, Cui Y, Bymaster FP, McKinzie DL, Felder CC, Deng CX, Faraci FM, Wess J (2001) Cholinergic dilation of cerebral blood vessels is abolished in M(5) muscarinic acetylcholine receptor knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 14096–14101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Z, Surmeier DJ (1996) Muscarinic (m2/m4) receptors reduce N- and P-type Ca2+ currents in rat neostriatal cholinergic interneurons through a fast, membrane-delimited, G-protein pathway. J Neurosci 16: 2592–2604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yap CC, Wisco D, Kujala P, Lasiecka ZM, Cannon JT, Chang MC, Hirling H, Klumperman J, Winckler B (2008) The somatodendritic endosomal regulator NEEP21 facilitates axonal targeting of L1/NgCAM. J Cell Biol 180: 827–842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeomans J, Forster G, Blaha C (2001) M5 muscarinic receptors are needed for slow activation of dopamine neurons and for rewarding brain stimulation. Life Sci 68: 2449–2456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Craciun LC, Mirshahi T, Rohacs T, Lopes CM, Jin T, Logothetis DE (2003) PIP(2) activates KCNQ channels, and its hydrolysis underlies receptor-mediated inhibition of M currents. Neuron 37: 963–975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Sulzer D (2003) Glutamate spillover in the striatum depresses dopaminergic transmission by activating group I metabotropic glutamate receptors. J Neurosci 23: 10585–10592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Sulzer D (2004) Frequency-dependent modulation of dopamine release by nicotine. Nat Neurosci 7: 581–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Basile AS, Gomeza J, Volpicelli LA, Levey AI, Wess J (2002a) Characterization of central inhibitory muscarinic autoreceptors by the use of muscarinic acetylcholine receptor knock-out mice. J Neurosci 22: 1709–1717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Yamada M, Gomeza J, Basile AS, Wess J (2002b) Multiple muscarinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes modulate striatal dopamine release, as studied with M1-M5 muscarinic receptor knock-out mice. J Neurosci 22: 6347–6352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou FM, Liang Y, Dani JA (2001) Endogenous nicotinic cholinergic activity regulates dopamine release in the striatum. Nat Neurosci 4: 1224–1229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou FM, Wilson CJ, Dani JA (2002) Cholinergic interneuron characteristics and nicotinic properties in the striatum. J Neurobiol 53: 590–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M, Rebholz H, Brocia C, Warner-Schmidt JL, Fienberg AA, Nairn AC, Greengard P, Flajolet M (2010) Forebrain overexpression of CK1delta leads to down-regulation of dopamine receptors and altered locomotor activity reminiscent of ADHD. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 4401–4406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.