Spatial cycles in G-protein crowd control

The importance and role of post-translational modifications in targeting signalling components to specific cellular sub-locations is reviewed by the Bastiaen's lab.

Keywords: intracellular signalling, reaction diffusion, spatial organization

Abstract

The nature of living systems and their apparent resilience to the second law of thermodynamics has been the subject of extensive investigation and imaginative speculation. The segregation and compartmentalization of proteins is one manifestation of this departure from equilibrium conditions; the effect of which is now beginning to be elucidated. This should not come as a surprise, as even a cursory inspection of cellular processes reveals the large amount of energetic cost borne to maintain cell-scale patterns, separations and gradients of molecules. The G-proteins, kinases, calcium-responsive proteins have all been shown to contain reaction cycles that are inherently coupled to their signalling activities. G-proteins represent an important and diverse toolset used by cells to generate cellular asymmetries. Many small G-proteins in particular, are dynamically acylated to modify their membrane affinities, or localized in an activity-dependent manner, thus manipulating the mobility modes of these proteins beyond pure diffusion and leading to finely tuned steady state partitioning into cellular membranes. The rates of exchange of small G-proteins over various compartments, as well as their steady state distributions enrich and diversify the landscape of possibilities that GTPase-dependent signalling networks can display over cellular dimensions. The chemical manipulation of spatial cycles represents a new approach for the modulation of cellular signalling with potential therapeutic benefits.

Spatial cycles in signaling

Biological systems are heterogeneous on all scales ranging from ecological habitats to sub-cellular compartments, with asymmetries dominating the informational landscape. However, in most cases, the asymmetries are in dynamic equilibrium, with the individual components free to transverse the boundaries. When the total number of entities in the entire system remains constant over time but there is a flux of entities between distinct locations in the system, this is considered ‘spatial cycling'.

The simplest spatial cycles of mobile entities originate due to their interactions with substantially slower supramolecular structures (Maini et al, 1992; Benson et al, 1993, 1998; Dillon et al, 1994). Cellular organelles constituted of membranes, the cytoskeleton and other relatively immobile features, although being dynamic, have a steady state presence that facilitates spatial cycles of relatively rapidly moving molecules that may interact with them. Spatial cycles may therefore be confined to specific locales in the cell, or spread across the cellscape depending on the molecules and physiochemical nature of the supramolecular structures. The interaction between mobile entities and semi-static structures need not be direct, but may be mediated by intervening molecular mediators. Furthermore, multiple structures and their respective interactions may contribute to the intertwining of different cycling systems of the same molecular species, as will be discussed in the case of Rab G-proteins later. In either case, the structural integrities and mobility may be driven by enthalpic or entropic factors. However, the net effect is the utilization of free energy to generate a kinetically maintained steady state (De Kepper et al, 1990) that entails an inhomogeneous distribution of molecules in the volume of a cell. The abundance of molecular transport processes, in combination with a ready supply of energy and the specific localization of such activities in biological systems, provides a pre-existing framework for the formation of spatial cycles.

Spatial cycles occur in the background of signalling events involved in the sustenance of living systems. In recent years, mechanistic analyses of signalling have revealed non-linear phenomena, such as bistability (Xiong and Ferrell, 2003; Angeli et al, 2004; Sabouri-Ghomi et al, 2008; Ferrell Jr, 2009; Kulkarni et al, 2010; Narula et al, 2010; To and Maheshri, 2010), temporal dynamics and hysteresis (Kramer and Fussenegger, 2005; Kholodenko et al, 2010; Takahashi et al, 2010; Weichsel and Schwarz, 2010), all of which are observed to be critical to the relevant cellular process or structure. Although molecular interactions and network topologies explain some aspects of these phenomena, models describing signalling must implicitly include assumptions relating to reaction-diffusion, compartmentalization and other geo-structural features of the cell, such as spatial cycling.

Small G-proteins constitute a superfamily of proteins with a characteristic feature: relatively minor variations in a single GTP/GDP-binding core domain have been adapted through evolution to have a role in nearly every known signalling process in cells (Bourne et al, 1991). The core ‘G-domain' has no preference for binding GTP or GDP and is an inefficient GTPase, requiring interaction with GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs) for hydrolysing GTP to GDP (Wittinghofer et al, 1997). The exchange of GDP with GTP for the next catalytic turnover requires interaction with guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs), which serve to pry the molecular structure of a G-protein to expose the guanine nucleotide-binding pocket. Effective exchange is driven by the approximately 10-fold surplus of cytoplasmic GTP with respect to GDP (Antonarakis and Van Aelst, 1998; Zhang et al, 2005). Thus, all small G-proteins have the ability to exist in either a GTP-bound (activated) or GDP-bound (inactivated) state in a catalytic GTPase cycle operated through the intervention of GEFs and GAPs that are themselves downstream effectors of signalling processes. The structurally similar core G-domain in the superfamily is extended with so called ‘hypervariable' peptide regions that confer additional unique characteristics, such as localization, different binding affinities and oligomerization properties, providing selectivity for specific effectors and signalling responses (Matallanas et al, 2003; Quinlan et al, 2008). The myriad functions of the small G-proteins thus seem to be effected through the interplay of their common GTPase cycle, with other spatio-temporal phenomena, including those mediated by their hypervariable regions. The following discussion considers the general concept of spatial cycles and its effects on other reaction cycles, focusing on intracellular signalling networks with G-proteins as a canonical example. We describe aspects of spatial cycling for three functionally distinct G-protein classes—Rab, Ran and Ras, which are well characterized at the molecular and cellular level and regulation of which has concrete medical implications. However, it may be noted that many other protein classes, including distantly related ones, such as Src family tyrosine kinases or synaptic membrane receptors, have conceptually similar forms of spatial cycling with varying degree of similarities in the molecular details.

G-proteins in vesicular targeting

The numerous isoforms of Rab G-proteins observed in eukaryotes are implicated in inter-compartmental transport through vesicles, most notably within the endosomal pathway. The GTP/GDP exchange cycle of these proteins not only controls their interaction with effectors, but is also super-imposed on their spatial cycling between the relevant compartments. Typically, GTP-loaded Rab proteins are membrane bound, and are inactivated by GAPs when the membrane, as a vesicle or otherwise, reaches its target acceptor organelle (Stenmark and Olkkonen, 2001). Aptly named guanine dissociation inhibitors (GDIs) interact strongly with GDP-bound (but not GTP bound) Rab proteins, sequestering inactive Rab proteins into a cytoplasmic pool (Nishimura et al, 1994; Wu et al, 1996; Rak et al, 2003). Membrane-bound GDI displacement factors (GDFs) such as PRA-1/Yip3 counteract this effect by dissociating GDI-Rab complexes (Sivars et al, 2003) and may localize Rab proteins to membranes (Hutt et al, 2000), thus making Rab accessible to GEFs. RabGEFs themselves seem to be sufficient to maintain sequestration of Rab molecules on membranes (Wu et al, 2010). It is exactly this coupling of the Rab guanine nucleotide state to interactions with spatially partitioned molecules that allows the Rab spatial cycle to take place. The selective localization of activated Rab proteins to vesicular membranes provides the vesicle with an identity tag as it leaves the donor membrane, whereas inactivated Rab molecules are reshuffled back the donor membrane by solubilizing factors such as GDIs.

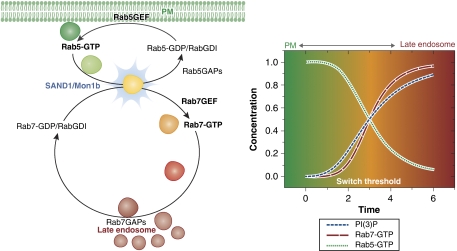

Although the Rab cycle remains valid for all canonical members of the family, the identity of the Rab proteins changes with that of the donor and acceptor membranes. Activated, that is, GTP-loaded Rab5, for example, is recruited to early endocytic vesicles derived from the plasma membrane. Its enrichment on the early endosomes is then maintained by a positive feedback loop between Rab5 and RabX5, a Rab5 GEF. The Rab5 cycle is terminated on various acceptor membranes that contain GAPs for Rab5. Endocytic vesicles may also merge to form late endosomes and transform to lysosomes (Spang, 2009). Recent studies conclusively prove that the sorting of vesicles into either pathway is attributed to Rab conversion—in which, for example, Rab5 enrichment is converted to Rab7 enrichment on vesicular membranes through a series of steps. Rab7-enriched vesicles merge with the late endosomal compartments, and the Rab7 cycle between early endosomes and the late endosomal/lysosomal membranes mirrors that of Rab5 between early endosomes and the plasma membrane (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of Rab5–Rab7 conversion on endocytic vesicles (coloured spheres). Rab5GEFs on donor membranes activate Rab5 and the activated GTP-loaded Rab5 is recruited to the endocytic vesicular membrane. As PI(3)P levels on the vesicular membrane build up, Mon1b recruitment occurs (blue flash), thereby driving the activation and recruitment of Rab7 and inhibition of the Rab5 positive feedback. Rab5GAPs inactivate Rab5 by catalysing GTP hydrolysis and Rab5-GDIs sequester inactivated Rab5 into the cytosol, allowing its diffusion to the PM, in which it may once more be activated on newly formed vesicles. Similarly, as the vesicles reach the late endosomal structures, Rab7GAPs on these membranes inactivate Rab7, and Rab7GDIs sequester it into the cytosol, allowing it to diffuse to vesicles undergoing the Rab5–Rab7 conversion event. Inset: schematic representation showing time dependence of Rab5 and Rab7 activation (and thus vesicular recruitment) in relation to PI(3)P levels. The reaction progression of PI(3)P generation is correlated with the spatial coordinates of vesicles.

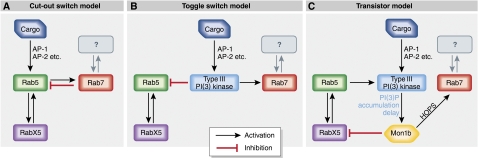

The Rab5–Rab7 conversion system has been proposed to operate like a cut-out switch (Del Conte-Zerial et al, 2008), based on comparisons with a ‘toggle-switch' model, both of which exhibit bistability (Figure 2A and B). In the ‘cut-out switch' model, Rab5 exhibits positive feedback as well as indirectly activates Rab7, whereas Rab7 displays positive feedback and indirectly inhibits Rab5. Thus, Rab5 is exchanged for Rab7 after a threshold level of Rab5 activity has been achieved on the vesicular membrane. Furthermore, as the inactive Rab5-GDP is essentially sequestered into the cytosol by GDIs, and Rab7 reaches a high activity level due to its positive feedback, the switch is essentially irreversible. This coupling mode of the Rab5 and Rab7 spatial cycles provides a mechanistic explanation for Rab conversion, although, it does not illustrate how spatio-temporal effects and cargo identity influence vesicle sorting—which is presumably the primary function of the Rab conversion. The ‘toggle-switch' model, however, implies the presence of a master controller, which responds to signals emanating from cargo proteins and drives Rab conversion. Simulations and experimental data on Rab5/Rab7 recruitment based on a ‘cut-out switch' model, or the competing ‘toggle-switch' model, do not agree well, implying that decisions for Rab conversion do not follow either model precisely. Recent work by the same group that proposed the switch models provides evidence for an alternative logic (Poteryaev et al, 2010), in which a dual-role protein SAND1/Mon1b, which inhibits Rab5 activation and enhances Rab7 activation, controls the levels of Rab5 and Rab7 enrichment based on a cargo-influenced timer.

Figure 2.

Schematic representations of Rab5–Rab7 conversion models. A Rab5–RabX5 positive feedback and the presence of a cargo-mediated signal through adaptor proteins, such as AP-1, are common features of all models. (A) Cut-out switch model: Rab5 is activated by a cargo-mediated signal. A negative feedback between Rab5 and Rab7 competes with, and eventually overrides the positive feedback between Rab5 and RabX5, thus facilitating Rab conversion (B) Toggle-switch model: cargo-activated Type III PI(3) kinases generate PI(3)P on the vesicular membrane and act as master controllers. Here, PI(3)P inhibits Rab5 and activates Rab7, leading to Rab conversion. (C) Transistor model: The cargo-mediated and Rab5-mediated activation of Type III PI(3) kinases generates PI(3)P on the vesicular membrane. Accumulation of PI(3)P recruits Mon1b, which inhibits RabX5, thereby interrupting the Rab5–RabX5 positive feedback. Mon1b simultaneously activates Rab7 through the HOPS complex. This dual effect of Mon1b causes Rab conversion. The Rab7GEF that maintains activation and enrichment of Rab7 is as yet unknown, but could be the HOPS complex itself.

The conversion from Rab5-‘tagged' to Rab7-‘tagged' endosomes begins with the accumulation of PI(3)P in the vesicular membrane through the action of Type III PI(3)-kinases. Numerous adaptor proteins facilitate activation of PI(3) kinases through signals originating partially from cargo proteins in the vesicle (Cowles, 1997; Keyel et al, 2008). As PI(3)P levels increase to a certain threshold level, the Mon1b protein (SAND1 in Caenorhabditis elegans) is recruited to the vesicular membrane. Mon1b disrupts the vesicular localization of the Rab5GEF (RabX5), thereby preventing its activation by Rab5-GTP and interrupting the Rab5 positive feedback. Rab5-GTP levels from this point would start to decrease through the action of RabGAPs and subsequent sequestration of Rab-GDP into the cytosol by RabGDIs. Further, Mon1b is known to interact with the HOPS complex, resulting in recruitment and activation of Rab7. The net effect is a loss of Rab5 along with concomitant increase in Rab7-GTP on the vesicular membrane. However, it is known that Rab5 itself will also activate the aforementioned Type III PI(3) kinases (Panaretou et al, 1997; Spang, 2009). This implies that Rab5 is part of an indirect negative feedback through the recruitment of Mon1b, which depends on the amount of time required to build up sufficient PI(3)P levels on the vesicular membrane (Figure 1). When the Rab5–Rab7 conversion will occur, most probably depends on the relative strengths of the Rab5–RabX5 positive feedback versus the Rab5–Mon1b negative feedback. The cargo-mediated activation of Type III PI(3) kinases seems to potentiate the negative feedback on Rab5, ultimately leaving the decision of the fate of the vesicle to the nature of the cargo it is carrying. On the basis these facts, the Rab5–Rab7 conversion seems to operate in a mixed mode in which coupling between Rab5 and Rab7 activity exists, while still integrating signals originating from cargo molecules. In keeping with the analogy with electronic circuits used by the previous researchers, Rab conversion seems to be neither a cut-out switch, nor a toggle switch, but is reminiscent of a transistor in gain-amplification mode (Figure 2C). Here, activation of Type III PI(3) kinases by cargo is the base current in the transistor analogy, which opens the PI(3)P/Mon1b-based ‘gate' for conversion of Rab5 (emitter current) enrichment to Rab7 (collector current) enrichment. Thus, like a transistor, the system may exist in two states: Rab5-activated (and enriched) and Rab7-activated (and enriched) depending on the nature of the cargo. We note that a transistor model is also inherently bistable and therefore in agreement with the intuitive fundamental assumptions that led to the testing of the simpler ‘cut-out switch' and ‘toggle-switch' models.

Whether such Rab conversions occur for other Rab G-proteins, such as Rab9 that targets vesicles towards the Golgi (Barbero et al, 2002), Rab3 that has a role in exocytosis (Lledo et al, 1994), or Rab4 and Rab11, which recycle vesicles to the plasma membrane (de Wit et al, 2001; Peden et al, 2004), remains an open question. Considering that numerous similarities dominate the mechanism of vesicular transport in these regimes, it is likely that the Rab conversion model represents a general paradigm in vesicular transport processes.

G-proteins in nuclear transport

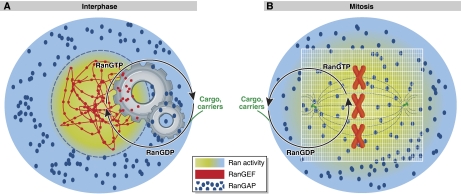

Ran is a small GTPase with a major role in the transport of proteins between the nucleus and cytoplasm in the cell. Proteins bearing a nuclear localization signal (NLS; Kalderon et al, 1984) bind to the Importin-α/β complex, forming a ternary complex that can permeate through the nuclear pore (Görlich et al, 1994; Goldfarb et al, 2004). Ran-GTP binding with Importin-β causes dissociation of this ternary complex, liberating the NLS-bearing protein (Pemberton and Paschal, 2005; Lonhienne et al, 2009). However, proteins bearing a nuclear export signal (NES) bind to the karyopherin exportin, and this complex is exported when bound by Ran-GTP (Brownawell and Macara, 2002; Calado et al, 2002). This basic selectivity is complemented by the distributions of proteins affecting the activation state of Ran. The only known RanGEF RCC1 (Cole and Hammell, 1998) is bound to chromatin through all phases of the cell cycle (Seki et al, 1996; England et al, 2010). This results in the continuous generation of Ran-GTP in the nucleus, causing Importin-NLS complexes to dissociate and leading to the increased concentration of free NLS-bearing proteins in the nucleus with respect to the cytoplasm. Correspondingly, RanGAPs are localized to the cytosol and cytoplasmic face of the nuclear envelope (Matunis et al, 1998), generating Ran-GDP from the Ran-GTP bound to Exportin-NES complexes arriving from the nucleus, thereby dissociating the complex. This results in the net transport of NES-bearing proteins into the cytosol, with exportin acting as a shuttle (Mattaj and Englmeier, 1998). The Ran protein is free to diffuse between the two compartments. As the compartmental separation between RanGEFs and RanGAPs is essentially provided by the nuclear membrane, a sharp Ran activity gradient results between the nucleus and cytoplasm (Kalab et al, 2002). The GTPase cycle of Ran is spatially segregated and drives the vectorial movement of cargo proteins. The role of the coupling between localization and activity for Ran seems to be subtly different than that of Rab proteins. In the case of Rab proteins, the spatial localization superimposes a finer level of control onto its GTPase cycle, allowing the Rab protein to function as a high-fidelity identity tag on mobile membranes. Ran, by contrast, functions as an energy transducer; the GTPase cycle drives the localization of Ran and by tertiary influence that of nuclear cargo (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Ran gradients in the two states of the cell cycle. (A) RanGEF activity (red) is localized on chromatin, generating activated RanGTP in its vicinity. As RanGAP activity is excluded from the nucleus in interphase cells, Ran shuttles between the nucleus and cytoplasm in its GTPase cycle. Interactions of RanGTP with karyopherins allow the Ran GTPase cycle to function as a motor driving vectorial nuclear transport of cargo using the free energy of GTP hydrolysis. (B) During mitosis, the nuclear envelope is lost, and RanGAP activity is homogenously spread throughout the mitotic cytosol. RanGEF remains chromatin bound, generating high local RanGTP concentrations. This RanGTP is converted to RanGDP as it diffuses away from chromatin and stochastically encounters homogeneously distributed RanGAPs. The Ran cycle thus forms a gradient-based positioning system around chromatin, providing cues for guidance and self-assembly of the spindle and its regulatory processes.

One of the salient features of the Ran reaction cycle is that the RanGEF RCC1 is itself a NLS-containing protein (Nemergut and Macara, 2000; Talcott and Moore, 2000), creating a positive feedback for the activation of Ran in the vicinity of chromatin. This positive feedback provides robustness to the symmetry violation, allowing it to persist even in the absence of a physical barrier such as the nuclear envelope. Indeed, the Ran reaction cycle has a major organizational role during mitosis and is an example of how the context of a spatial reaction cycle defines its function (Askjaer et al, 2002; Figure 3B). In mitosis, the same system exemplifies an aspect of spatial cycles, in which they not only shuttle proteins between compartments, but may actually induce the creation of compartments, in which activity gradients rather than physico-chemical barriers, are the primary anisotropic features. During mitosis, the nuclear envelope is disassembled. However, the RanGEF RCC1 remains bound to chromatin, with a local concentration that is probably higher than that of interphase chromatin due to condensation of the latter. The mitotic cytosol still contains RanGAPs, which are now homogenously distributed. This leads to the formation of a dynamically maintained Ran activity gradient, with high concentrations of Ran-GTP near the chromatin, and higher concentrations of Ran-GDP at greater distances (Kalab et al, 2002). Although the Ran GTPase reaction seems to be a thermodynamically futile cycle, the resulting Ran activity gradient emanating from the condensed chromatin serves the same purpose as the RanGTP in the nucleus of interphase cells: the release of NLS-bearing proteins in the vicinity of chromatin (Caudron et al, 2005). The subset of NLS-bearing proteins released in the vicinity of chromatin during mitosis consists of proteins involved in the regulation of spindle formation: chromosome tethering (Arnaoutov and Dasso, 2005), microtubule stabilizers (Yokoyama et al, 2008) and nucleators (Mishra et al, 2010). Even re-assembly of the nuclear envelope in daughter cells after cell division seems to use the Ran gradient. The Ran gradient system has thus been shown to serve as a positioning system (Kalab and Heald, 2008) for self-assembly of the spindle (Caudron et al, 2005) and subsequent mitotic processes, allowing necessary factors to ‘home in' around chromatin as mitosis progresses.

G-proteins in growth factor signalling

The small G-protein Ras was the first oncogene to be identified (Malumbres and Barbacid, 2003), with mutations in Ras genes having prevalence as high as 20–30% in human cancers (Bos, 1989). Subsequent studies have elucidated the role of Ras as a central node in the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade, as well as numerous other signalling pathways (Goodsell, 1999). The human genome contains three versions of the Ras gene, named Harvey (H)-Ras, Neuroblastoma (N)-Ras and Kirsten (K)-Ras. H-, N- and K-Ras have >90% similarity in their G-domains, and differ mostly in their hypervariable regions (Chang et al, 1982). Microscopic imaging of cellular distributions showed fluorescently tagged H- and N-Ras enriched on the Golgi apparatus and the plasma membrane, albeit with quantitative difference in partitioning, whereas K-Ras was enriched only on the plasma membrane. Moreover, the H- and N-Ras cellular distributions were shown to be dynamically maintained, with Ras molecules being continuously exchanged between the Golgi and the plasma membrane at a relatively fast rate, revealing that H- and N-Ras operated within a spatial cycle (Rocks et al, 2005). The spatial cycle of H/N-Ras is now known to be dependent on the reversible S-palmitoylation of cysteine residues in the hypervariable region (Rocks et al, 2005). K-Ras, which has a polybasic stretch of lysine residues instead of palmitoylatable cysteines, was shown to change its localization on phosphorylation of a serine residue next to the polybasic stretch in its hypervariable region (Quatela et al, 2008). It is therefore likely that its localization is also maintained by a spatial cycle.

In contrast to Rab and Ran, spatial cycling of Ras proteins does not seem to be dependent on their guanine nucleotide state, but rather the activity state is modulated by the spatial cycle. For example, for palmitoylated Ras proteins a continuous spatial cycle is maintained between the Golgi apparatus and the plasma membrane that super-imposes on the GTPase cycle, and thereby overlays temporal characteristics of the spatial cycle onto the Ras signalling response.

The palmitoylatable H- and N-Ras proteins, similar to most of the Ras family proteins, are farnesylated at their C-terminus, providing them weak membrane affinity. Farnesylated Ras molecules rapidly diffuse throughout the cell, quickly reaching an equilibrium state that shows unspecific, but highly dynamic partitioning to all cellular membranes (Rocks et al, 2010). This is expected from a simple entropic viewpoint. However, H- and N-Ras proteins also reversibly acquire palmitoyl groups at cysteine residues close to the farnesylation site, conferring additional hydrophobicity, and thereby higher stability on cellular membranes (Dudler and Gelb, 1996). Switching between these high- and low-membrane-affinity states along with disparately localized acylation/de-acylation activities forms the basic spatial reaction cycle for H- and N-Ras.

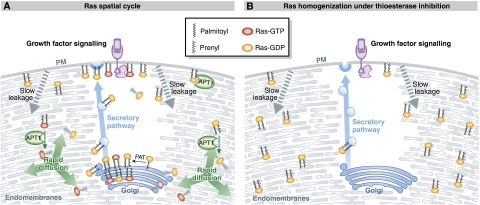

Palmitoyl transferase (PAT) activity has been attributed to the zDHHC proteins in yeast and mammalian systems, which use palmitoyl-CoA as acyl-donors, catalysing the transfer of the palmitoyl group from CoA to the sulphydryl group of a cysteine residue on proteins (Bartels et al, 1999; Bijlmakers and Marsh, 2003; Fukata et al, 2004; Goytain et al, 2008; Matakatsu and Blair, 2008; Iwanaga et al, 2009). Whatever the identity of the PAT activity, it is clear that the relevant palmitoylation reaction is confined to the cytoplasmic face of the Golgi apparatus, thereby locally trapping rapidly diffusing farnesylated Ras molecules by increasing their membrane affinity (Rocks et al, 2010). Consequently, the increased stability of Ras-membrane interactions at the Golgi subjects palmitoylated Ras to slower transport processes on vesicles in the secretory pathway. The directional transport of Ras on these vesicles causes an enrichment of Ras on the plasma membrane. Although the enrichment of Ras on the plasma membrane makes it available for several signalling pathways, such enrichment is slowly lost through leakage to all cellular endomembranes, also owing to the dynamic nature of the plasma membrane. As plasma membrane regions fuse and mix with intracellular membranes, stably anchored Ras molecules will be transferred to these other membranes, eventually leading to aspecific localization over all cellular membranes. Such (mis)-localization of palmitoylated Ras over all membranes represents the tendency of the system to reach thermodynamic equilibrium and is indistinguishable from the distribution seen for solely farnesylated Ras molecules. The situation is rectified through the action of thioesterases, which depalmitoylate Ras molecules, thereby returning them to the rapidly diffusing low-membrane-affinity farnesylated form. In effect, depalmitoylation increases the probability per unit time of stochastically encountering the Golgi apparatus by increasing the diffusion speed of Ras. Here, Ras molecules get trapped by re-palmitoylation, thus completing a single turn of the acylation cycle. The enrichment of Ras at the plasma membrane is thus a result of the dynamic trapping of Ras at the Golgi, which is then conveyed to the plasma membrane by the secretory pathway.

For such a correction mechanism for mislocalized protein to function, depalmitoylation activity must be spread throughout the cytoplasm of the cell. Indeed, acyl protein thioesterase-1 (APT1), a protein known to depalmitoylate Ras is present ubiquitously in the cytosol (Hirano et al, 2009). Incidentally, APT1 and its close homologue APT2 are the only two candidates that may mediate such a depalmitoylation reaction, and are seen to be rather promiscuous in their substrate specificity for the peptide chain and the acyl chain. This promiscuity is expected, considering that several other proteins besides Ras undergo a similar acylation cycle, but there do not seem to be any other soluble thioesterases in the cytosol. In summary, this ‘acylation cycle' maintains a non-equilibrium partitioning of palmitoylatable Ras by the asymmetric distribution of the palmitoylation and thioesterase activities, with the secretory pathway providing vectorial transport necessary to cause enrichment on the plasma membrane (Dekker et al, 2010; Figure 4). This model for the spatial organization of Ras has been verified in experiments in which palmitoylation is blocked with inhibitors of palmitate synthesis, such as 2-bromopalmitate (Coleman et al, 1992). Under these conditions, there is a net conversion of Ras to the low-membrane-affinity unpalmitoylated form, that distributes aspecifically over all membranes of the cell. When depalmitoylation is blocked, all Ras is now converted to the palmitoylated form, whose equilibrium distribution is indistinguishable from that of a non-palmitoylated but farnesylated Ras mutant (Dekker et al, 2010). Under physiological conditions, the slow entropic processes of Ras leakage from membranes and membrane mixing processes are overruled by the far more efficient thioesterase reaction that converts Ras to the solely prenylated form that is rapidly trapped at the Golgi. The spatial cycling of Ras through acylation and deacylation therefore counters the entropic homogenization of Ras over the cell, ensuring that Ras remains enriched in compartments that are most relevant to its function. It is worth noting that such a system does not involve receptors on membrane compartments that recognize lipidation states of molecules. Both PATs and thioesterases are promiscuous with respect to their substrates and require only a membrane-proximal cysteine. Evolution, it seems, can cast a spatial cycle onto a peripheral membrane protein with as little as a point mutation.

Figure 4.

The H/N-Ras spatial cycle uses an acylation cycle and vectorial transport to maintain localization and counter entropy increase. (A) Golgi-confined palmitoylation of Ras and transport to the PM through the secretory pathway, account for enrichment of H/N-Ras at the Golgi and PM, respectively. This palmitoylated Ras will slowly redistribute to all membranes (leakage). Ubiquitous depalmitoylation by thioesterases, such as APT1, converts mislocalized palmitoylated Ras to the fast-diffusing solely farnesylated form. Diffusion increases the probability of a Golgi encounter, in which it is (re)-palmitoylated and transported to the PM through the secretory pathway. (B) Perturbation of the spatial cycle through thioesterase inhibition, leads to eventual leakage from the PM, and equilibrium binding of palmitoylated Ras on all cellular membranes, effectively diluting Ras on the plasma membrane and attenuating its signalling response.

Similar to all G-proteins, Ras proteins also have a GTP/GDP cycle and are activated in response to a variety of stimuli: the most commonly studied being growth factor signalling. Transport to the plasma membrane (PM), PM enrichment, rapid diffusion and trapping at the Golgi are all features of the Ras spatial cycle, which convolute with its activation mechanisms, conferring it with unique signal propagation characteristics. For example, the canonical RasGEF Son of Sevenless (SOS) requires Ras to be membrane tethered before it can be activated (Freedman et al, 2006). In addition, SOS contains binding domains towards adaptor proteins, such as Grb2 that bind to activated receptor tyrosine kinases (Jang et al, 2010) through phosphotyrosines and towards plasma membrane lipids, such as phosphatidic acid (Zhao et al, 2007) and phosphatidylinositol. Combined, these specificities indicate that SOS almost exclusively activates Ras at the plasma membrane (Innocenti et al, 2002). The localized activation of Ras is further amplified due to a positive feedback mediated by the allosteric activation of SOS by Ras-GTP, and to some extent due to further membrane recruitment of SOS by Ras. For example, dampening effects on the MAPK response due to abolished allosteric binding in SOS mutants have been shown to be rescued by independent membrane targeting of such SOS mutants through recombination with the Ras C-terminus, subjecting them to the same acylation cycle as Ras. These experiments highlight the role the acylation cycle has in the generation of robust Ras activation on the plasma membrane. Ras activity on the plasma membrane, however, is transient despite the amplifying effects of the positive feedback on SOS. The adaptive response of Ras activity on the plasma membrane may be attributed to several factors such as recruitment of RasGAPs (Smida et al, 2007; Ding and Lengyel, 2008), internalization of the growth factor receptor over longer time scales (Goh et al, 2010), or negative feedback on SOS through its phosphorylation by Erk (Waters et al, 1995; Chen et al, 1996). On short time scales, the acylation cycle exerts a modulatory effect. As Ras is constantly being depalmitoylated and thus diffuses away, its total concentration on the plasma membrane is maintained at a certain steady-state level, while allowing the spread of active Ras in other regions of the cell (Harvey et al, 2008). Such a system clearly contributes to the non-linear MAPK response characteristics observed on stimulation with different growth factors in living cells (Santos et al, 2007). In addition to these processes, phenomena such as activity-dependent clustering of Ras proteins in the plasma membrane (Tian et al, 2007), or specific partitioning to lipid rafts (Prior et al, 2001) add an additional layer of spatial complexity to Ras signalling dynamics.

In the context of Ras effectors that are not located on the plasma membrane, the dynamic cycling of Ras molecules allows for a ‘clutch and gear' framework, in which activity is transmitted via the energy used to maintain the spatial cycle. Transmission of Ras signals after growth factor activation to different cellular locations can occur by the generation of an activated Ras pulse into the pre-existing spatially cycling population. The acylation cycle allows the rapid diffusion of activated Ras throughout the cytoplasm until it is enriched at the Golgi through (re-)palmitoylation, enabling access to effectors spread throughout the cytoplasm. As Golgi encounters are stochastic, the pulse-like Ras activation response at the plasma membrane is widened at the Golgi, whereas its amplitude is reduced (Lorentzen et al, 2010). Ras effectors, such as RIG1(Tsai et al, 2007), and MAPK scaffolds, such as Sef and BIT1(Philips, 2004; Yi et al, 2010), which are restricted to the ER or Golgi complex, teliologically imply a function for Ras-mediated signalling in these cellular compartments. The precise nature of this signalling remains open for study but multiple lines of evidence indicate that phenotypic effects on cells require Ras activation on specific cellular compartments (Chiu et al, 2002; Inder et al, 2008). In the context of the acylation cycle there is little doubt that effectors on internal membranes experience a Ras temporal activation profile that is substantially different from that seen by effectors on the plasma membrane.

The third major isoform of Ras in mammalian cells, K-Ras, is farnesylated like H/N-Ras, but does not contain a palmitoylatable cysteine. K-Ras displays a specific enrichment only on the plasma membrane, but not on the Golgi. The enrichment of K-Ras on the PM is attributed to electrostatic interactions between the lysine-rich polybasic stretch in its hyper variable region, and the negative surface charges on the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane, contributed mainly by headgroups of phosphatidylserine and phosphatidylinositols (Leventis and Silvius, 1998). The lack of enrichment of K-Ras on the Golgi is in concordance with the evidence from studies on H/N-Ras, showing that Golgi enrichment is primarily a result of a Golgi-localized palmitoylation reaction. Phosphorylation of a serine residue next to the polybasic stretch is reported to partially neutralize its net positive charges, causing K-Ras to repartition to the mitochondria (Bivona et al, 2006). Other processes cause its partitioning to the ER or late endosomes (Yeung et al, 2008; Lu et al, 2009)—KRas therefore reaches most endomembranes. Furthermore, de novo synthesized K-Ras is reported to ‘exit' the sequence of post-translational modifications on the surface of the ER at an unknown stage and reach the plasma membrane through an anomalous route (Apolloni et al, 2000). In the context of the minimum requirements for a spatial cycle discussed earlier—a fast moving species and a relatively immobile trapping structure, a model for the maintenance of K-Ras localization may be proposed. The plasma membrane, which is a relatively static feature, provides a thermodynamically favoured trapping interaction with the polybasic stretch on K-Ras through its negative charge. If the plasma membrane would be a completely static structure, maintaining only its bilayer asymmetry, de novo synthesized K-Ras would eventually be enriched at the plasma membrane after slowly reaching equilibrium. However, the vesicular dynamics of the plasma membrane contribute entropic factors that will cause K-Ras to redistribute to endomembranes. For palmitoylated H/N-Ras, depalmitoylation provides a resetting mechanism that allows rapid diffusion and kinetic trapping at the Golgi (far from equilibrium). In the case of K-Ras, it is likely that certain proteins may solubilize K-Ras from endomembranes, thus increasing its effective diffusion in the cytoplasm, and thereby increasing the chances for encounter with the plasma membrane to reinstate equilibrium. Solubilizing molecules are known, in general as chaperone proteins (Ben-Zvi et al, 2004; Mayer and Bukau, 2005; Scholz et al, 2005; Malki et al, 2008), and also in the case of other Ras family proteins, in which GDIs solubilize the respective GDP-bound forms (Soldati et al, 1993). However, such solubilizing proteins need not be specific to the GTP- or GDP-loaded form of their targets, but may simply bind hydrophobic regions, such as the prenyl group, thus shielding them from the hydrophilic cytosol. A protein that binds K-Ras, and functions as a diffusion facilitator, will cause mixing and solubilization of molecules that are prenylated, hastening the approach to equilibrium, in which K-Ras molecules are enriched on the plasma membrane. Confirmatory evidence for the action of such solubilizing factors will solve discrepancies concerning the diffusion and membrane residence times of prenylated Ras proteins, which seem to be far more rapid and transient respectively in vivo, than what is observed in vitro (Schroeder et al, 1997).

Modulation of spatial cycles in potential therapeutic applications

Conventional cancer drug therapy in particular depends either on inactivation of hyper-activated molecules, as is seen in the case of inhibitors of tyrosine kinases (Klohs et al, 1997) or, at the other extreme, on essentially harnessing a pleiotropic effect to cause apoptotic death, as is the case with cytoskeleton targeting drugs (Calligaris et al, 2010). The manipulation of spatial cycles to alter signalling presents an exciting opportunity to control cellular dynamics in a rational manner. Although the approach is not devoid of pleiotropic phenomena, the fact that the intended target molecule is far removed in the interaction network from the site of drug action allows for fine-tuning of the inhibition to reduce oncogenic signalling below a certain threshold level. As spatial cycles work in tandem with activation cycles of proteins, and exert an indirect effect, they present the opportunity for finer control of signalling activities at the expense of sensitivity—the so-called ‘Hormetic dose-response' (Calabrese and Baldwin, 2003; Scott, 2004; Preston, 2005). In particular contexts, in which basal activities of signalling molecules are essential for cell survival, as is often the case for neurological and oncogenic diseases, the manipulation of spatial cycles provides a gentler approach in manipulating cellular signalling network states.

The intimate relationships between spatial cycles of G-proteins and their activity in signalling networks reveals an avenue for signalling response manipulation by altering the steady state localization of such molecules. Strategies to interfere with pathological cellular signalling have focussed largely on inhibition of hyperactive signalling pathways. However, as conserved cellular signalling modules such as the MAPK cascade are used for the transmission of multiple signalling cues to various effectors (Roberts et al, 2000; Chavel et al, 2010), complete inhibition of signalling leads to several undesirable effects due to the acute perturbation of important branches of a signalling network. For example, the potent Mek inhibitor UO126 effectively terminates downstream MAPK signalling, but results in widespread toxicity (Finegan et al, 2009; Cheng and Force, 2010) due to the collateral inhibition of survival signalling. Modulation of spatial cycles, however, may allow leveraging of non-linear signalling responses to nudge signalling networks into a desirable parameter regime (Gomez-Uribe et al, 2007), to selectively attenuate pathological phenotypic effects on the cell. Such a strategy was reported in the attenuation of oncogenic Ras signalling in transformed tumour-like cells. The presence of the constitutively active G12D/V mutation in a single allele of a Ras gene can catapult the MAPK cascade into a permanent ‘on' state due to positive feedbacks that activate even the wild-type (WT) Ras expressed from the other allele. The ‘gain-of-function' mutant Ras generates an offset in the Ras dose–response relationship that might trigger full activation of the WT Ras dependent on its expression level. By downmodulating the amount of mutant Ras that can effectively couple into effectors, the feedback strength is weakened, thereby putting the system into a regime with only partially activated Ras and a phenotype that still has regulated growth factor responses. Inhibition of constitutively active signalling on the level of Ras is extremely challenging, as is evidenced by the complete lack of any known Ras inhibitors. Therefore, the Ras spatial cycle is a lucrative target for the modulation of oncogenic Ras signalling. As is described previously, ubiquitous depalmitoylation has a crucial role in Ras localization and thereby signalling responses. Palmostatin B is a recently developed drug (Dekker et al, 2010), affecting the palmitoyl protein thioesterases APT1 and 2, the Ras-depalmitoylating enzymes. Treatment of cells with Palmostatin B leads to accumulation of permanently palmitoylated Ras, which ‘leaks' from the plasma membrane into all cellular membranes to reach equilibrium, unable to diffuse rapidly and re-enter the spatial cycle through trapping at the Golgi. The net result of thioesterase inhibition is to reduce the amount of Ras at the plasma membrane and thereby to reduce the interaction of oncogenic Ras with its effectors. This might substantially weaken the positive feedback loop with SOS and thereby the activity of WT Ras. These dual effects attenuate the MAPK activity significantly, bringing its activation state into a growth factor controllable regime. On the phenotypic level, the molecular effects of Palmostatin B manifest themselves as a partial reversion of a tumour-like phenotype to a normal phenotype in H-RasG12V-transformed MDCK cells (Dekker et al, 2010). This is evidenced by restoration of E-cadherin to the plasma membrane indicating contact inhibition (Onder et al, 2008), and morphological changes of the cell from an elongated spindle-like shape to a typical cuboidal shape of untransformed MDCK cells (Karaguni et al, 2002).

Palmostatin B treatment of untransformed MDCK cells shows no apparent toxicity or morphological changes. It should be noted that although oncogenic Ras redistributes over all membranes after Palmostatin B treatment, it is still GTP loaded. It is, however, unable to effectively couple into the downstream MAPK cascade, indicating that oncogenic MAPK signalling originates primarily from the oncogenic factors on the plasma membrane (Matallanas et al, 2006). The fact that several oncogenic proteins reside on the plasma membrane seems to corroborate this hypothesis.

The perturbation of spatial cycles for manipulating cellular processes may be expanded beyond Ras proteins. The ensemble of proteins displaying spatial cycling is large. Heterotrimeric G-proteins, most Src family kinases, secreted enzymes, signalling molecules, such as Sonic Hedgehog, the Huntington protein, several proteins involved in synaptic trafficking display the Ras-like palmitoylation-based spatial cycle. Transmembrane receptors have spatial cycles based on endocytic sorting. Arf-GTPases that modulate ER–Golgi traffic seem to have spatial cycles akin to that of Rab, although spatiotemporal dynamics are not well understood. Rho, Rac and Cdc42 GTPases have activity gradients and GDI proteins akin to Rab, the effects of which have been discussed previously (Rajnicek et al, 2006). Indeed, the effect of cellular size and shape has been theoretically postulated to have a substantial effect on signalling activities due to the relative scale of activity gradients and cycles and their respective temporal properties (Meyers et al, 2006). The modulation of the activities of these proteins has implications in oncogenesis, development, neuropathology, immune responses and possibly on several biological phenomena that remain to be discovered. As probing and detection methods have improved over the last 10 years in their temporal and spatial resolution, at the same time becoming more and more non-invasive, empirical observation of spatial cycles of proteins in living cells has become more accessible. The development of high-throughput adaptations of advanced microscopy techniques (Grecco et al, 2010), coupled with similar high-throughput detection of signalling activities and networks (Olsen et al, 2010), along with progress in the mathematical modelling of cellular processes (Bressloff, 2006) sets the stage for the exploitation of spatial cycles in tinkering with biology.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Angeli D, Ferrell JE, Sontag ED (2004) Detection of multistability, bifurcations, and hysteresis in a large class of biological positive-feedback systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 1822–1827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonarakis S, Van Aelst L (1998) Mind the GAP, Rho, Rab and GDI. Nat Genet 19: 106–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apolloni A, Prior IA, Lindsay M, Parton RG, Hancock JF (2000) H-ras but not K-ras traffics to the plasma membrane through the exocytic pathway. Mol Cell Biol 20: 2475–2487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnaoutov A, Dasso M (2005) Ran-GTP regulates kinetochore attachment in somatic cells. Cell Cycle 4: 1161–1165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Askjaer P, Galy V, Hannak E, Mattaj IW (2002) Ran GTPase cycle and importins alpha and beta are essential for spindle formation and nuclear envelope assembly in living Caenorhabditis elegans embryos. Mol Biol Cell 13: 4355–4370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbero P, Bittova L, Pfeffer SR (2002) Visualization of Rab9-mediated vesicle transport from endosomes to the trans-Golgi in living cells. J Cell Biol 156: 511–518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels DJ, Mitchell DA, Dong X, Deschenes RJ (1999) Erf2, a novel gene product that affects the localization and palmitoylation of Ras2 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 19: 6775–6787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson DL, Maini PK, Sherratt JA (1993) Analysis of pattern formation in reaction diffusion models with spatially inhomogenous diffusion coefficients. Math Comput Modelling 17: 29–34 [Google Scholar]

- Benson DL, Maini PK, Sherratt JA (1998) Unravelling the Turing bifurcation using spatially varying diffusion coefficients. J Math Biol 37: 381–417 [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Zvi A, De Los Rios P, Dietler G, Goloubinoff P (2004) Active Solubilization and Refolding of Stable Protein Aggregates By Cooperative Unfolding Action of Individual Hsp70 Chaperones. J Biol Chem 279: 37298–37303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bijlmakers M, Marsh M (2003) The on–off story of protein palmitoylation. Trends Cell Biol 13: 32–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bivona TG, Quatela SE, Bodemann BO, Ahearn IM, Soskis MJ, Mor A, Miura J, Wiener HH, Wright L, Saba SG (2006) PKC egulates a farnesyl-electrostatic switch on K-Ras that promotes its association with Bcl-Xl on mitochondria and induces apoptosis. Mol Cell 21: 481–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos JL (1989) Ras oncogenes in human cancer: a review. Cancer Res 49: 4682–4689 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne HR, Sanders DA, McCormick F (1991) The GTPase superfamily: conserved structure and molecular mechanism. Nature 349: 117–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bressloff PC (2006) Stochastic model of protein receptor trafficking prior to synaptogenesis. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys 74: 031910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownawell AM, Macara IG (2002) Exportin-5, a novel karyopherin, mediates nuclear export of double-stranded RNA binding proteins. J Cell Biol 156: 53–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese EJ, Baldwin LA (2003) The hormetic dose-response model is more common than the threshold model in toxicology. Toxicol Sci 71: 246–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calado A, Treichel N, Müller E, Otto A, Kutay U (2002) Exportin-5-mediated nuclear export of eukaryotic elongation factor 1A and tRNA. EMBO J 21: 6216–6224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calligaris D, Verdier-Pinard P, Devred F, Villard C, Braguer D, Lafitte D (2010) Microtubule targeting agents: from biophysics to proteomics. Cell Mol Life Sci 67: 1089–1104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caudron M, Bunt G, Bastiaens P, Karsenti E (2005) Spatial coordination of spindle assembly by chromosome-mediated signaling gradients. Science 309: 1373–1376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang EH, Gonda MA, Ellis RW, Scolnick EM, Lowy DR (1982) Human genome contains four genes homologous to transforming genes of Harvey and Kirsten murine sarcoma viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 79: 4848–4852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavel CA, Dionne HM, Birkaya B, Joshi J, Cullen PJ (2010) Multiple signals converge on a differentiation MAPK pathway. PLoS Genet 6: e1000883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Waters SB, Holt KH, Pessin JE (1996) SOS phosphorylation and disassociation of the Grb2–SOS complex by the ERK and JNK signaling pathways. J Biol Chem 271: 6328–6332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H, Force T (2010) Molecular mechanisms of cardiovascular toxicity of targeted cancer therapeutics. Circ Res 106: 21–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu VK, Bivona T, Hach A, Sajous JB, Silletti J, Wiener H, Johnson RL, Cox AD, Philips MR (2002) Ras signalling on the endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi. Nat Cell Biol 4: 343–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole CN, Hammell CM (1998) Nucleocytoplasmic transport: driving and directing transport. Curr Biol 8: R368–R372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman RA, Rao P, Fogelsong RJ, Bardes ES (1992) 2-Bromopalmitoyl-CoA and 2-bromopalmitate: promiscuous inhibitors of membrane-bound enzymes. Biochim Biophys Acta 1125: 203–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowles C (1997) The AP-3 adaptor complex is essential for cargo-selective transport to the yeast vacuole. Cell 91: 109–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Kepper P, Ouyang Q, Boissonade J, Roux JC (1990) Sustained coherent spatial structures in a quasi-1D reaction-diffusion system. React Kinet Catal Lett 42: 275–288 [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H, Lichtenstein Y, Kelly RB, Geuze HJ, Klumperman J, van der Sluijs P (2001) Rab4 regulates formation of synaptic-like microvesicles from early endosomes in PC12 cells. Mol Biol Cell 12: 3703–3715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker FJ, Rocks O, Vartak N, Menninger S, Hedberg C, Balamurugan R, Wetzel S, Renner S, Gerauer M, Schölermann B, Rusch M, Kramer JW, Rauh D, Coates GW, Brunsveld L, Bastiaens PIH, Waldmann H (2010) Small-molecule inhibition of APT1 affects Ras localization and signaling. Nat Chem Biol 6: 449–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Conte-Zerial P, Brusch L, Rink JC, Collinet C, Kalaidzidis Y, Zerial M, Deutsch A (2008) Membrane identity and GTPase cascades regulated by toggle and cut-out switches. Mol Syst Biol 4: 206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon R, Maini PK, Othmer HG (1994) Pattern formation in generalized Turing systems. J Math Biol 32: 345–393 [Google Scholar]

- Ding B, Lengyel P (2008) p204 protein is a novel modulator of ras activity. J Biol Chem 283: 5831–5848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudler T, Gelb MH (1996) Palmitoylation of Ha-Ras facilitates membrane binding, activation of downstream effectors, and meiotic maturation in xenopus oocytes. J Biol Chem 271: 11541–11547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- England JR, Huang J, Jennings MJ, Makde RD, Tan S (2010) RCC1 uses a conformationally diverse loop region to interact with the nucleosome: a model for the RCC1-nucleosome complex. J Mol Biol 398: 518–529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell JE Jr (2009) Signaling Motifs and Weber's Law. Molecular Cell 36: 724–727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finegan KG, Wang X, Lee E, Robinson AC, Tournier C (2009) Regulation of neuronal survival by the extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase 5. Cell Death Differ 16: 674–683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman TS, Sondermann H, Friedland GD, Kortemme T, Bar-Sagi D, Marqusee S, Kuriyan J (2006) A Ras-induced conformational switch in the Ras activator Son of sevenless. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 16692–16697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukata M, Fukata Y, Adesnik H, Nicoll RA, Bredt DS (2004) Identification of PSD-95 palmitoylating enzymes. Neuron 44: 987–996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh LK, Huang F, Kim W, Gygi S, Sorkin A (2010) Multiple mechanisms collectively regulate clathrin-mediated endocytosis of the epidermal growth factor receptor. J Cell Biol 189: 871–883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldfarb DS, Corbett AH, Mason DA, Harreman MT, Adam SA (2004) Importin [alpha]: a multipurpose nuclear-transport receptor. Trends Cell Biol 14: 505–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Uribe C, Verghese GC, Mirny LA (2007) Operating regimes of signaling cycles: statics, dynamics, and noise filtering. PLoS Comput Biol 3: e246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodsell DS (1999) The molecular perspective: the ras oncogene. Oncologist 4: 263–264 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Görlich D, Prehn S, Laskey RA, Hartmann E (1994) Isolation of a protein that is essential for the first step of nuclear protein import. Cell 79: 767–778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goytain A, Hines RM, Quamme GA (2008) Huntingtin-interacting proteins, HIP14 and HIP14L, mediate dual functions, palmitoyl acyltransferase and Mg2+ transport. J Biol Chem 283: 33365–33374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grecco HE, Roda-Navarro P, Girod A, Hou J, Frahm T, Truxius DC, Pepperkok R, Squire A, Bastiaens PIH (2010) In situ analysis of tyrosine phosphorylation networks by FLIM on cell arrays. Nat Methods 7: 467–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey CD, Yasuda R, Zhong H, Svoboda K (2008) The spread of Ras activity triggered by activation of a single dendritic spine. Science 321: 136–140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano T, Kishi M, Sugimoto H, Taguchi R, Obinata H, Ohshima N, Tatei K, Izumi T (2009) Thioesterase activity and subcellular localization of acylprotein thioesterase 1/lysophospholipase 1. Biochim Biophys Acta 1791: 797–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutt DM, Da-Silva LF, Chang L, Prosser DC, Ngsee JK (2000) PRA1 inhibits the extraction of membrane-bound Rab GTPase by GDI1. J Biol Chem 275: 18511–18519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inder K, Harding A, Plowman SJ, Philips MR, Parton RG, Hancock JF (2008) Activation of the MAPK module from different spatial locations generates distinct system outputs. Mol Biol Cell 19: 4776–4784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innocenti M, Tenca P, Frittoli E, Faretta M, Tocchetti A, Fiore PPD, Scita G (2002) Mechanisms through which Sos-1 coordinates the activation of Ras and Rac. J Cell Biol 156: 125–136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwanaga T, Tsutsumi R, Noritake J, Fukata Y, Fukata M (2009) Dynamic protein palmitoylation in cellular signaling. Prog Lipid Res 48: 117–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang IK, Zhang J, Chiang YJ, Kole HK, Cronshaw DG, Zou Y, Gu H (2010) Grb2 functions at the top of the T-cell antigen receptor-induced tyrosine kinase cascade to control thymic selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 10620–10625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalab P, Heald R (2008) The RanGTP gradient—a GPS for the mitotic spindle. J Cell Sci 121: 1577–1586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalab P, Weis K, Heald R (2002) Visualization of a Ran-GTP gradient in interphase and mitotic Xenopus egg extracts. Science 295: 2452–2456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalderon D, Roberts BL, Richardson WD, Smith AE (1984) A short amino acid sequence able to specify nuclear location. Cell 39: 499–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karaguni I, Herter P, Debruyne P, Chtarbova S, Kasprzynski A, Herbrand U, Ahmadian M, Glusenkamp K, Winde G, Mareel M, Möröy T, Müller O (2002) The new sulindac derivative IND 12 reverses Ras-induced cell transformation. Cancer Res 62: 1718–1723 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyel PA, Thieman JR, Roth R, Erkan E, Everett ET, Watkins SC, Heuser JE, Traub LM (2008) The AP-2 adaptor {beta}2 appendage scaffolds alternate cargo endocytosis. Mol Biol Cell 19: 5309–5326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kholodenko BN, Hancock JF, Kolch W (2010) Signalling ballet in space and time. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 11: 414–426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klohs WD, Fry DW, Kraker AJ (1997) Inhibitors of tyrosine kinase. Curr Opin Oncol 9: 562–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer BP, Fussenegger M (2005) Hysteresis in a synthetic mammalian gene network. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 9517–9522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni VV, Kareenhalli V, Malakar P, Pao LY, Safonov MG, Viswanathan GA (2010) Stability analysis of the GAL regulatory network in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Kluyveromyces lactis. BMC Bioinformatics 11(Suppl 1): S43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventis R, Silvius JR (1998) Lipid-binding characteristics of the polybasic carboxy-terminal sequence of K-ras4B. Biochemistry 37: 7640–7648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lledo PM, Johannes L, Vernier P, Zorec R, Darchen F, Vincent JD, Henry JP, Mason WT (1994) Rab3 proteins: key players in the control of exocytosis. Trends Neurosci 17: 426–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonhienne TG, Forwood JK, Marfori M, Robin G, Kobe B, Carroll BJ (2009) Importin-beta is a GDP-to-GTP exchange factor of Ran: implications for the mechanism of nuclear import. J Biol Chem 284: 22549–22558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorentzen A, Kinkhabwala A, Rocks O, Vartak N, Bastiaens P (2010) Spatial regulation of Ras reveals a novel mode of intracellular signal propagation (submitted) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lu A, Tebar F, Alvarez-Moya B, López-Alcalá C, Calvo M, Enrich C, Agell N, Nakamura T, Matsuda M, Bachs O (2009) A clathrin-dependent pathway leads to KRas signaling on late endosomes en route to lysosomes. J Cell Biol 184: 863–879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maini PK, Benson DL, Sherratt JA (1992) Pattern formation in reaction-diffusion models with spatially inhomogeneous diffusion coefficients. Math Med Biol 9: 197–213 [Google Scholar]

- Malki A, Le H, Milles S, Kern R, Caldas T, Abdallah J, Richarme G (2008) Solubilization of protein aggregates by the acid stress chaperones HdeA and HdeB. J Biol Chem 283: 13679–13687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malumbres M, Barbacid M (2003) RAS oncogenes: the first 30 years. Nat Rev Cancer 3: 459–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matakatsu H, Blair SS (2008) The DHHC palmitoyltransferase approximated regulates fat signaling and Dachs localization and activity. Curr Biol 18: 1390–1395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matallanas D, Arozarena I, Berciano MT, Aaronson DS, Pellicer A, Lafarga M, Crespo P (2003) Differences on the inhibitory specificities of H-Ras, K-Ras, and N-Ras (N17) dominant negative mutants are related to their membrane microlocalization. J Biol Chem 278: 4572–4581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matallanas D, Sanz-Moreno V, Arozarena I, Calvo F, Agudo-Ibanez L, Santos E, Berciano MT, Crespo P (2006) Distinct utilization of effectors and biological outcomes resulting from site-specific Ras activation: Ras functions in lipid rafts and Golgi complex are dispensable for proliferation and transformation. Mol Cell Biol 26: 100–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattaj IW, Englmeier L (1998) Nucleocytoplasmic transport: the soluble phase. Annu Rev Biochem 67: 265–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matunis MJ, Wu J, Blobel G (1998) SUMO-1 modification and its role in targeting the Ran GTPase-activating protein, RanGAP1, to the nuclear pore complex. J Cell Biol 140: 499–509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer M, Bukau B (2005) Hsp70 chaperones: cellular functions and molecular mechanism. Cell Mol Life Sci 62: 670–684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers J, Craig J, Odde DJ (2006) Potential for control of signaling pathways via cell size and shape. Curr Biol 16: 1685–1693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra RK, Chakraborty P, Arnaoutov A, Fontoura BMA, Dasso M (2010) The Nup107-160 complex and gamma-TuRC regulate microtubule polymerization at kinetochores. Nat Cell Biol 12: 164–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narula J, Smith AM, Gottgens B, Igoshin OA (2010) Modeling reveals bistability and low-pass filtering in the network module determining blood stem cell fate. PLoS Comput Biol 6: e1000771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemergut ME, Macara IG (2000) Nuclear import of the ran exchange factor, RCC1, is mediated by at least two distinct mechanisms. J Cell Biol 149: 835–850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura N, Nakamura H, Takai Y, Sano K (1994) Molecular cloning and characterization of two rab GDI species from rat brain: brain-specific and ubiquitous types. J Biol Chem 269: 14191–14198 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen JV, Vermeulen M, Santamaria A, Kumar C, Miller ML, Jensen LJ, Gnad F, Cox J, Jensen TS, Nigg EA, Brunak S, Mann M (2010) Quantitative phosphoproteomics reveals widespread full phosphorylation site occupancy during mitosis. Sci Signal 3: ra3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onder TT, Gupta PB, Mani SA, Yang J, Lander ES, Weinberg RA (2008) Loss of E-Cadherin promotes metastasis via multiple downstream transcriptional pathways. Cancer Res 68: 3645–3654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panaretou C, Domin J, Cockcroft S, Waterfield MD (1997) Characterization of p150, an adaptor protein for the human phosphatidylinositol (PtdIns) 3-Kinase. J Biol Chem 272: 2477–2485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peden AA, Schonteich E, Chun J, Junutula JR, Scheller RH, Prekeris R (2004) The RCP-Rab11 complex regulates endocytic protein sorting. Mol Biol Cell 15: 3530–3541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pemberton LF, Paschal BM (2005) Mechanisms of receptor-mediated nuclear import and nuclear export. Traffic 6: 187–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philips MR (2004) Sef: a MEK/ERK catcher on the Golgi. Mol Cell 15: 168–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteryaev D, Datta S, Ackema K, Zerial M, Spang A (2010) Identification of the switch in early-to-late endosome transition. Cell 141: 497–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston RJ (2005) Bystander effects, genomic instability, adaptive response, and cancer risk assessment for radiation and chemical exposures. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 207: 550–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prior IA, Harding A, Yan J, Sluimer J, Parton RG, Hancock JF (2001) GTP-dependent segregation of H-ras from lipid rafts is required for biological activity. Nat Cell Biol 3: 368–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quatela SE, Sung PJ, Ahearn IM, Bivona TG, Philips MR (2008) Analysis of K-Ras phosphorylation, translocation, and induction of apoptosis. Meth Enzymol 439: 87–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan MP, Quatela SE, Philips MR, Settleman J (2008) Activated Kras, but Not Hras or Nras, may initiate tumors of endodermal origin via stem cell expansion. Mol Cell Biol 28: 2659–2674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajnicek AM, Foubister LE, McCaig CD (2006) Temporally and spatially coordinated roles for Rho, Rac, Cdc42 and their effectors in growth cone guidance by a physiological electric field. J Cell Sci 119: 1723–1735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rak A, Pylypenko O, Durek T, Watzke A, Kushnir S, Brunsveld L, Waldmann H, Goody RS, Alexandrov K (2003) Structure of Rab GDP-dissociation inhibitor in complex with prenylated YPT1 GTPase. Science 302: 646–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts CJ, Nelson B, Marton MJ, Stoughton R, Meyer MR, Bennett HA, He YD, Dai H, Walker WL, Hughes TR, Tyers M, Boone C, Friend SH (2000) Signaling and circuitry of multiple MAPK pathways revealed by a matrix of global gene expression profiles. Science 287: 873–880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocks O, Gerauer M, Vartak N, Koch S, Huang Z, Pechlivanis M, Kuhlmann J, Brunsveld L, Chandra A, Ellinger B, Waldmann H, Bastiaens PIH (2010) The palmitoylation machinery is a spatially organizing system for peripheral membrane proteins. Cell 141: 458–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocks O, Peyker A, Kahms M, Verveer PJ, Koerner C, Lumbierres M, Kuhlmann J, Waldmann H, Wittinghofer A, Bastiaens PIH (2005) An acylation cycle regulates localization and activity of palmitoylated Ras isoforms. Science 307: 1746–1752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabouri-Ghomi M, Ciliberto A, Kar S, Novak B, Tyson JJ (2008) Antagonism and bistability in protein interaction networks. J Theor Biol 250: 209–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos SDM, Verveer PJ, Bastiaens PIH (2007) Growth factor-induced MAPK network topology shapes Erk response determining PC-12 cell fate. Nat Cell Biol 9: 324–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz C, Schaarschmidt P, Engel AM, Andres H, Schmitt U, Faatz E, Balbach J, Schmid FX (2005) Functional solubilization of aggregation-prone HIV envelope proteins by covalent fusion with chaperone modules. J Mol Biol 345: 1229–1241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder H, Leventis R, Rex S, Schelhaas M, Nagele E, Waldmann H, Silvius JR (1997) S-Acylation and plasma membrane targeting of the farnesylated carboxyl-terminal peptide of N-ras in mammalian fibroblasts. Biochemistry 36: 13102–13109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott B (2004) A biological-based model that links genomic instability, bystander effects, and adaptive response. Mutat Res/Fundam Mol Mech Mutagen 568: 129–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki T, Hayashi N, Nishimoto T (1996) RCC1 in the Ran pathway. J Biochem 120: 207–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivars U, Aivazian D, Pfeffer SR (2003) Yip3 catalyses the dissociation of endosomal Rab-GDI complexes. Nature 425: 856–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smida M, Posevitz-Fejfar A, Horejsi V, Schraven B, Lindquist JA (2007) A novel negative regulatory function of the phosphoprotein associated with glycosphingolipid-enriched microdomains: blocking Ras activation. Blood 110: 596–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldati T, Riederer M, Pfeffer S (1993) Rab GDI: a solubilizing and recycling factor for rab9 protein. Mol Biol Cell 4: 425–434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spang A (2009) On the fate of early endosomes. Biol Chem 390: 753–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenmark H, Olkkonen V (2001) The Rab GTPase family. Genome Biol 2: reviews3007.1–reviews3007.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, tilde;nase-Nicola S, ten Wolde PR (2010) Spatio-temporal correlations can drastically change the response of a MAPK pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107: 2473–2478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talcott B, Moore MS (2000) The nuclear import of RCC1 requires a specific nuclear localization sequence receptor, Karyopherin α3/Qip. J Biol Chem 275: 10099–10104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian T, Harding A, Inder K, Plowman S, Parton RG, Hancock JF (2007) Plasma membrane nanoswitches generate high-fidelity Ras signal transduction. Nat Cell Biol 9: 905–914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- To T, Maheshri N (2010) Noise can induce bimodality in positive transcriptional feedback loops without bistability. Science 327: 1142–1145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai F, Shyu R, Jiang S (2007) RIG1 suppresses Ras activation and induces cellular apoptosis at the Golgi apparatus. Cell Signal 19: 989–999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters SB, Holt KH, Ross SE, Syu L, Guan K, Saltiel AR, Koretzky GA, Pessin JE (1995) Desensitization of Ras activation by a feedback disassociation of the SOS-Grb2 complex. J Biol Chem 270: 20883–20886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weichsel J, Schwarz US (2010) Two competing orientation patterns explain experimentally observed anomalies in growing actin networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 6304–6309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittinghofer A, Scheffzek K, Ahmadian MR (1997) The interaction of Ras with GTPase-activating proteins. FEBS Lett 410: 63–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu SK, Zeng K, Wilson IA, Balch WE (1996) Structural insights into the function of the Rab GDI superfamily. Trends Biochem Sci 21: 472–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Oesterlin LK, Tan K, Waldmann H, Alexandrov K, Goody RS (2010) Membrane targeting mechanism of Rab GTPases elucidated by semisynthetic protein probes. Nat Chem Biol 6: 534–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong W, Ferrell JE (2003) A positive-feedback-based bistable/‘memory module/' that governs a cell fate decision. Nature 426: 460–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung T, Gilbert GE, Shi J, Silvius J, Kapus A, Grinstein S (2008) Membrane phosphatidylserine regulates surface charge and protein localization. Science 319: 210–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi P, Nguyen DT, Higa-Nishiyama A, Auguste P, Bouchecareilh M, Dominguez M, Bielmann R, Palcy S, Liu JF, Chevet E (2010) MAPK scaffolding by BIT1 in the Golgi complex modulates stress resistance. J Cell Sci 123: 1060–1072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama H, Gruss OJ, Rybina S, Caudron M, Schelder M, Wilm M, Mattaj IW, Karsenti E (2008) Cdk11 is a RanGTP-dependent microtubule stabilization factor that regulates spindle assembly rate. J Cell Biol 180: 867–875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Zhang Y, Shacter E, Zheng Y (2005) Mechanism of the guanine nucleotide exchange reaction of Ras GTPase—evidence for a GTP/GDP displacement model. Biochemistry 44: 2566–2576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C, Du G, Skowronek K, Frohman MA, Bar-Sagi D (2007) Phospholipase D2-generated phosphatidic acid couples EGFR stimulation to Ras activation by Sos. Nat Cell Biol 9: 706–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]