Abstract

Binding of pertussis toxin (PTx) was examined by glycan microarray; 53 positive hits fell into four general groups. One group represents sialylated bi-antennary compounds with an N-glycan core terminating in α2-6 linked sialic acid. The second group consists of multi-antennary compounds with a canonical N-glycan core, but lacking terminal sialic acids, which represents a departure from previous understanding of PTx binding to N-glycans. The third group consists of Neu5Acα2-3(Lactose or N-acetyllactosamine) that lack the branched mannose core found in N-glycans, thus their presentation is more similar to O-linked glycans and glycolipids. The fourth group of compounds consists of Neu5Acα2-8Neu5Acα2-8Neu5Ac, which is seen in the c series gangliosides and some N-glycans. Quantitative analysis by SPR of the relative affinities of PTx for terminal Neu5Acα2-3 versus Neu5Acα2-6, as well as the affinities for the trisaccharide Neu5Acα2-8Neu5Acα2-8Neu5Ac versus disaccharide, revealed identical global affinities, even though the amount of bound glycan varied by 4- to 5-fold. These studies suggest that the conformational space occupied by a glycan can play an important role in binding, independent of affinity. Characterization of N-terminal and C-terminal binding sites on the S2 and S3 subunits by mutational analysis revealed that binding to all sialylated compounds was mediated by the C-terminal binding sites, and binding to non-sialylated N-linked glycans is mediated by the N-terminal sites present on both the S2 and S3 subunits. A detailed understanding of the glycans recognized by pertussis toxin is essential to understand which cells are targeted in clinical disease.

Vaccination has greatly reduced whooping cough (pertussis) morbidity and mortality; alarmingly however, the number of cases has been increasing in the US since a historic low in 1976 (1, 2). Pertussis toxin (PTx) is often considered the major virulence factor of B pertussis, as PTx mutants are avirulent in mouse models, and consequently PTx is included as a component in all acellular pertussis vaccines (3). PTx alone is responsible for the systemic manifestations of lymphocytosis and hyperinsulinemia, and is the chief candidate for defense against innate and adaptive immune systems past the initial colonization (4-7).

PTx is a member of the AB5 family of bacterial toxins, which includes cholera toxin from Vibrio cholerae, heat-labile toxin from Escherichia coli, and Shiga toxin from Shigella dysenteriae and Escherichia coli. AB5 toxins are hexameric polypeptide complexes consisting of five binding (B) subunits arranged in a ring structure and a single active (A) subunit with enzymatic properties sitting atop the pore of the ring structure. Unlike other AB5 toxins, which have five identical B subunits, the PTx B-pentamer has the 4 different subunits: S2, S3, S4, and S5 in the ratio 1:1:2:1 (8). The A subunit, named S1 in PTx, is an ADP-ribosyltransferase which targets the α-subunit of some GTP-binding proteins (9). The B-pentamer is required for cell-targeting and cytosolic entry of S1 into mammalian cells, but also has activities independent of S1, such as antigen-independent T cell activation and mitogenicity (8, 10-15). The fact that the binding (B) portion of the toxin has activity independent of the enzymatic action of the active (A) portion is a relatively new concept in the A-B model of protein toxin biology.

PTx binds primarily, if not solely, to the glycan residues present on cell-surface receptors and appears to have no affinity for the protein portion. Glycoprotein Ib, Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18), CD14, and TLR-4 have been implicated as PTx receptors; however direct binding has only been demonstrated for glycoprotein Ib (16-20). It is known that PTx can bind the serum glycoproteins fetuin and haptoglobin, which are used in toxin purification strategies (21-23). The interaction of PTx and the serum glycoprotein fetuin has been most extensively studied. Fetuin has roughly equal proportion of terminal Neu5Acα2-3Gal and Neu5Acα2-6Gal tri-antennary (A3) N-linked glycans (24). Comparative analysis of N-linked glycans revealed that PTx binds with higher affinity to Neu5Acα2-6Gal compared to Neu5Acα2-3Gal (25). A recent study found A3 and tetra-antennary (A4) bound avidly to PTx while A2 and A1 structures bound only minimally. Furthermore, removal of the terminal Neu5Ac, modification to the N-glycolyl form, or fucosylating the core carbohydrate residues decreased binding (26). This suggests that PTx binding to A3 and A4 glycans likely involves multiple PTx binding sites simultaneously interacting with those glycans.

Plant lectins and other AB5 toxins typically have multiple copies of identical binding sites resulting in multivalent binding to a single glycan. In contrast, PTx recognizes multiple glycan targets, possibly diversifying both the cells targeted by PTx as well as diversifying the effects of PTx on a particular target cell. While the B-pentamer of PTx has four distinct subunits, all amino acid residues involved in binding activities have thus far been mapped to the S2 and S3 subunits of the B-pentamer (21-23, 27-35). In addition, multiple binding sites have been identified on S2 and S3, and each site has a preference for a distinct glycan. S2 and S3 contain two domains, an N-terminal Aerolysin/Pertussis toxin domain (APT) [structural classification of proteins database (SCOP) entry 56467] spanning amino acids 1-89 and a C-terminal Bacterial AB5 toxins B-subunit domain (AB5-B) [SCOP entry 50204] spanning amino acids 90-200 (Figure 1). The AB5-B-subunit domains of S2-S5, as well as the B-subunits of all other AB5 toxins, share a similar fold and are structurally constrained since they mediate both pentamer assembly and association with the enzymatically active A subunit. The AB5-B-subunit domains of S2 and S3 share 77% amino acid identity and contain two homologous sialic acid binding sites, 2SA and 3SA (amino acids 101-105, 125), respectively (Figure 1). These sialic acid binding sites are the best characterized. An X-ray crystal structure of PTx with Neu5Ac-α(2-6)Gal terminal bi-antennary (A2) bound to 2SA and 3SA has been solved (31). Interestingly, while both the sialic acid and galactose molecules appear in the crystal structure, only the terminal sialic acid appears to make contact with the protein.

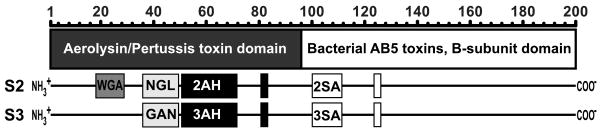

Figure 1.

Domains and putative binding sites of PTx subunits S2 and S3. Top, amino acid position number followed by boxes showing the positions of the Aerolysin/Pertussis toxin domain (dark box) and the Bacterial AB5 toxins B-subunit domain (light box). S2, representation of the putative binding sites of the S2 subunit: the wheat germ agglutinin homologous site (WGA), the neutral glycolipid binding site on S2 (NGL), the aerolysin-homologous sites on S2 (2AH), and the sialic acid binding site (2SA). S3, representation of the putative binding sites of the S3 subunit: the ganglioside binding site on S3 (GAN), the aerolysin-homologous site (3AH), and the sialic acid binding site (3SA).

The APT domains of S2 and S3 are more divergent and only share 66% identity, but share structural similarity to aerolysin and c-type lectins. APT domains encode five of the seven proposed binding sites; however, the exact number of binding sites is not entirely understood, since the sites were primarily defined by genetic mutation. Additionally, some sites may overlap. The proposed binding sites include a wheat germ agglutinin-homologous site on S2 (WGA aa18-23), a neutral glycolipid binding site on S2 (NGL aa37-51), a ganglioside binding site on S3 (GAN aa37-51), and aerolysin-homologous sites on S2 (2AH AA52-72, 82) and S3 (3AH AA52-72, 82) (Figure 1). Unfortunately, the involvement of these putative binding sites in A2 N-linked glycans binding could not be determined in the crystal structure because the APT domain sites were occluded by crystal packing contacts (31). Previous binding studies have mostly used poorly-defined natural glycan products; in this study we used highly purified, well-characterized glycans to study the binding preferences of PTx.

Materials and Methods

Glycan array

Genetically toxoided PTx (PTx 9K/129G, prepared at Chiron Bioscience and kindly provided by Rino Rappuoli (36-38) was analyzed by the Consortium for Functional Glycomics Protein-Glycan Interaction Core. Binding was analyzed at six concentrations (10, 48, 191, 476, 952, and 1,905 nM) to 320 different glycans arrayed on a glass slide (version 3.0). Toxin binding was detected by the anti-S1 monoclonal antibody 1B7 (39-41) and fluorescently labeled anti-Mouse IgG Alexa 488 which was supplied by the Consortium. The array consists of 6 replicates of each glycan and relative binding was expressed as mean relative fluorescence units (RFU) of 4 of the 6 replicates after removal of the highest and lowest values. Binding was considered positive if the RFU value was greater than the mean background RFU value plus 3 standard deviations, where mean background RFU is the mean of RFU values less than 10% of the maximum RFU value (Figure 2). Additionally, compounds with standard deviations greater than 75 percent of the mean were excluded from analysis. The dimer studies utilized a newer version of the array (version 4.1). Due to differences in the numbering of compounds between the two versions, if a compound number could refer to two different structures than a ‘(v4.1)’ is added to the compounds on the 4.1 version of the array. For example ‘55’ refers to the compound on version 3.0, while ‘55(v4.1) to the compound on version 4.1. The full data sets from the six glycan arrays, the structures of the glycans on the arrays, and detailed experimental protocols for glycan arrays can be found in a public database maintained by the CFG at their website (http://www.functionalglycomics.org).

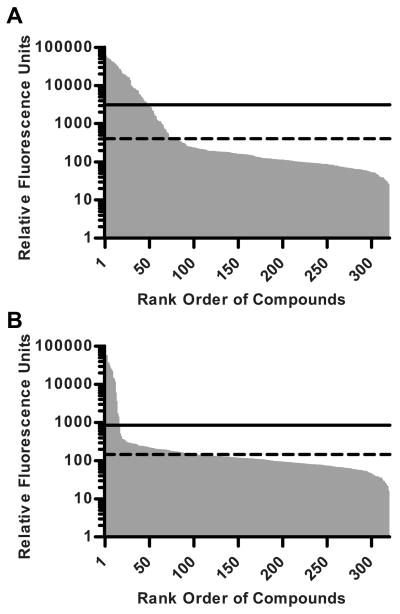

Figure 2.

Glycan array binding ranked by fluorescent intensity. Binding was considered positive if the RFU value was greater than the mean background RFU value (dashed line) plus 3 standard deviations where mean background RFU is the mean of RFU values less than 10% of the maximum RFU value (solid line). A, binding at 1,905 nM PTx. The maximum RFU value concentration was 59,078 (compound 199). The mean of all compounds with RFU values less than 5,907.8 (10% of the maximum RFU value) was 400±903 (Panel A-dashed line). The 48 compounds had RFU values greater than 3110 (mean background RFU value plus 3 standard deviations, Panel A-solid line). B, binding at the 191 nM PTx. Only 15 compounds had RFU values greater than 855 (mean background RFU value plus 3 standard deviations, Panel B-solid line).

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) studies

Binding to sialic acid compounds was assessed using a Biacore 2000. Streptavidin coated SA sensor chips (GE Healthcare UK Ltd.) were used for all experiments. Biotinylated synthetic carbohydrates utilized in the SPR studies were obtained either from the CFG Glycan Array Synthesis Core or synthesized as previously reported (42, 43). To prepare the SPR chips, biotinylated compounds were injected over the streptavidin chip at 20 μl/min until the desired saturation was reached, typically 400 RU. Biotinyalted PEG (MW 3500) was used as the control in flow cell 1. In order to detect PTx interactions with the carbohydrate compounds, different concentrations of the toxoid were injected at a flow rate of 20 μl/ml for 2.5 min followed by 2 injections of 50mM NaOH at 50 μL/ml to regenerate the surface. The sensogram data was analyzed using Biaeval 2.0®.

Recombinant Dimers

Primers F-NheI-AA-S2 (GCTAGCGCGGCGTCCACGCCAGGCATCGTC) and R-SpeI-Hind3-S2 (ACTAGTAAGCTTCAGCATAAGGATGATCCAG) were used to amplify the mature s2 gene and introduce a NheI site and 2×Ala codons upstream of the gene and a HindIII site and a SpeI site downstream of the gene. Primers F-NheI-AA-S3 (GCTAGCGCGGCGGTTGCGCCAGGCATCGTC) and R-SpeI-Hind3-S3 (ACTAGTAAGCTTCAGCATATCGACGCTGCC) were used to amplify the mature s3 gene and introduce a NheI site and 2×Ala codons upstream of the gene and a HindIII site and a SpeI site downstream of the gene. Primers F-NheI-AA-S4 (GCTAGCGCGGCGGACGTTCCTTATGTGCTG) and R-XhoI-S4His (AAATCTCGAGGGGGCAATCCTGCTTGCC) were used to amplify the mature s4 gene and introduce a NheI site and 2×Ala codons upstream of the gene and a XhoI site downstream of the gene. The PCR products for S2 and S3 were TA cloned into pCR2.1 (Invetrogen, Carlsbad, CA) to create plasmids pCR-S2 and pCR-S3 respectively and sequenced. The PCR product for S4 digested with NheI and XhoI and cloned into the plasmid pET21b (Novagen, Darmstadt, Germany) to create plasmid pET-S4his. The NheI-EcoRI fragment from pCR-S2 containing the S2 gene was subcloned into pET21b to create plasmid pET-S2, and the same method was used to create plasmid pET-S3 from pCR-S3. The complimentary oligonucleotides F-NdeI-DsbAsig-NheI (TATGAAAAAGATTTGGCTGGCGCTGGCTGGTTTAGTTTTAGCGTTTAGCG) and R-NdeI-DsbAsig-NheI (CTAGCGCTAAACGCTAAAACTAAACCAGCCAGCGCCAGCCAAATCTTTTTCA) containing the secretion signal fragment of the E coli gene dsbA flanked by a NdeI site upstream and a NheI site downstream was cloned into pET-S2 to create plasmid pETsecS2. The same method was used to create plasmid pETsecS3 from pET-S3 and plasmid pETsecS4his from pET-S4his. Site-directed mutagenesis of the s2 and s3 genes was carried out using the Stratagene QuikChange® II Site-Directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Life Sciences, Santa Clara, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol to create plasmids pETsecΔSA-S2 and pETsecΔSA-S3 carrying the Y102A-Y103A mutations in the s2 and s3 genes respectively. The plasmid pETsecS2S4his was created by cloning the s2 gene containing XbaI-PvuI fragment into the SpeI and PvuI sites of pETsecS4his, and the same protocol was used to create the other three dimer expression vectors. The expression plasmids (Novagen, Darmstadt, Germany) encoding the dimers or the S4 subunit were transformed into BL21(DE3)pLysS E. coli (Novagen, Darmstadt, Germany). Transformants were cultured in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth containing ampicillin (250 μg ml-1) and chloramphenicol (34 μg ml-1) at 37 °C, 250 rpm until reaching an OD600 value of 1. Cultures were cooled to 8 °C and B-subunit expression was induced with 0.1 mM IPTG and 2% ethanol, followed by shaking incubation for 16 h at 20 °C. The dimers or the S4 subunit were purified from induced culture lysates by Nickel chromatography (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden).

Results

Glycans recognized by PTx

Genetically toxoided PTx (PTx 9K/129G) was screened for binding to 320 structurally defined glycans utilizing the Consortium for Functional Glycomics (CFG) glycan microarray (version 3.0) at 1, 5, 20, 50, 100, and 200 μg/ml (10, 48, 191, 476, 952, and 1,905 nM). Positive binding occurred in 48 of the 320 glycans at the highest concentration tested (1,905 nM, Figure 2A). These 48 carbohydrate compounds fell into four general groups based on shared structural characteristics that represent different types of glycans in biological systems (Figure 3 and Table 1).

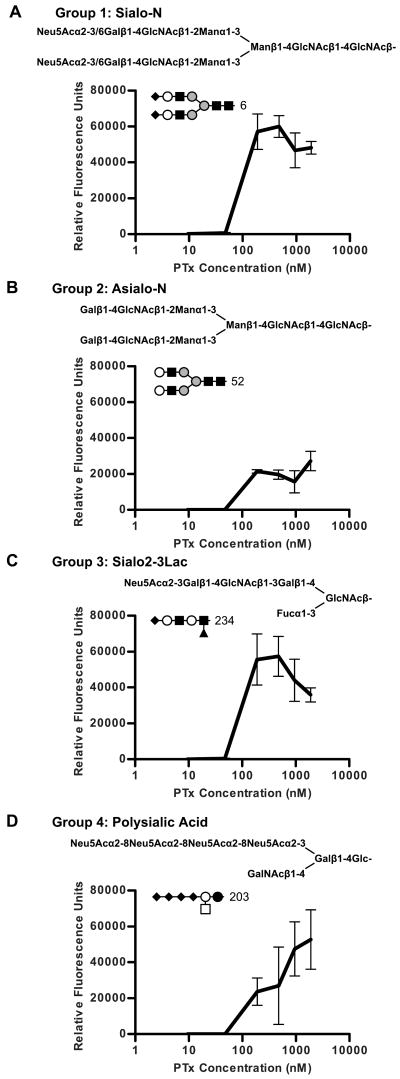

Figure 3.

Representative binding curves for four groups of compounds that bind PTx. Inset in the graph is a symbolic representation of the compounds following CFG standards: Neu5Ac (black diamond), Gal (white circle), GalNAc (white square), Glc (black circle), GlcNAc (black square), Man (grey circle), and Fuc (black triangle). A, Glycan array data for PTx binding to Group 1: Sialo-N, sialylated bi-antennary compounds, represented by Compound 6. B, Group 2: Asialo-N, non-sialylated bi-antennary compounds, represented by Compound 52. C, Group 3: Sialo2-3Lac, compounds defined by the shared pattern of Neu5Acα2-3(Lactose or N-acetyllactosamine), represented by Compound 234. D, Group 4: c Ganglioside, compounds defined by the shared pattern of Neu5Acα2-8Neu5Acα2-8Neu5Ac, represented by Compound 203.

Table 1. Glycans binding to PTx holotoxin.

| Glycan number |

Structure | Mean relative fluorescence units at 1905 nM |

Common Name | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1: Sialo-N | ||||

| 199 | Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(Neu5Acα2-3Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp12* | 59,078 | N-linked glycans | |

| 320 | Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp12 | 58,759 | N-linked glycans | |

| 54 | Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp8 | 49,990 | N-linked glycans | |

| 6 | Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp12 | 48,165 | N-linked glycans | |

| 295 | Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp12 | 47,390 | N-linked glycans | |

| 256 | Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp21 | 45,527 | N-linked glycans | |

| 319 | Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp12 | 41,746 | N-linked glycans | |

| 143 | Neu5Acα2-3Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(Neu5Acα2-3Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp12 | 40,574 | N-linked glycans | |

| 53 | Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp13 | 40,360 | N-linked glycans | |

| 318 | Neu5Acα2-3Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp12 | 37,409 | N-linked glycans | |

| 304 | GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp12 | 31,797 | N-linked glycans | |

| Group 2: Asialo-N | ||||

| 52 | Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp13 | 27,230 | N-linked glycans | |

| 51 | GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp13 | 19,442 | N-linked glycans | |

| 305 | GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp12 | 8,119 | N-linked glycans | |

| 241 | Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(Fucα1-3(Galβ1-4)GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp20 | 7,254 | N-linked glycans | |

| Group 3: Sialo2-3Lac | ||||

| 234 | Neu5Acα2-3Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-3Galβ1-4(Fucα1-3)GlcNAc-Sp0 | 35,907 | VIM-2/CDw65 | |

| 228 | Neu5Acα2-3Galβ1-4(Fucα1-3)(6OSO3)GlcNAcβ–Sp8 | 30,498 | 3′SLex | |

| 46 | Neu5Acα2-3[6OSO3]Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ–Sp8 | 25,761 | ||

| 208 | Neu5Acα2-3(6-O-Su)Galβ1-4(Fucα1-3)GlcNAcβ–Sp8 | 25,703 | 3′SLex | |

| 219 | Neu5Acα2-3Galβ1-3(Neu5Acα2-3Galβ1-4)GlcNAcβ-Sp8 | 22,556 | ||

| 221 | Neu5Acα2-3Galβ1-3(Neu5Acα2-6)GalNAcα–Sp8 | 19,807 | Sia2TF | |

| 213 | Neu5Acα2-3(Neu5Acα2-6)GalNAcα–Sp8 | 18,647 | 3,6-SiaTn | |

| 260 | Neu5Gcα2-3Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ–Sp0 | 18,505 | 3′SLec (Gc) | |

| 315 | Neu5Acα2-3Galβ1-3(Neu5Acα2-3Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-6)GalNAc–Sp14 | 17,671 | ||

| 227 | Neu5Acα2-3Galβ1-4[6OSO3]GlcNAcβ-Sp8 | 16,886 | ||

| 229 | Neu5Acα2-3Galβ1-4(Fucα1-3)GlcNAcβ1-3Galβ1-4(Fucα1-3)GlcNAcβ1-3Galβ1-4(Fucα1-3)GlcNAcβ–Sp0 | 16,408 | 3′SLex | |

| 212 | Neu5Acα2-3(Neu5Acα2-3Galβ1-3GalNAcβ1-4)Galβ1-4Glcβ-Sp0 | 13,351 | GD1a | |

| 232 | Neu5Acα2-3Galβ1-4(Fucα1-3)GlcNAcβ1-3Galβ-Sp8 | 9,644 | 3′SLex | |

| 238 | Neu5Acα2-3Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-3Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp0 | 9,309 | 3′SiaDi-LN | |

| 258 | Neu5Gcα2-3Galβ1-3GlcNAcβ-Sp0 | 8,573 | 3′SLec | |

| 226 | Neu5Acα2-3Galβ1-3GlcNAcβ–Sp8 | 8,285 | 3′SLec | |

| 257 | Neu5Gcα2-3Galβ1-3(Fucα1-4)GlcNAcβ-Sp0 | 7,895 | 3′SLea | |

| 233 | Neu5Acα2-3Galβ1-4(Fucα1-3)GlcNAcβ1-3Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp8 | 7,384 | 3′SLex | |

| 240 | Neu5Acα2-3Galβ1-4Glcβ–Sp8 | 7,061 | GM3 | |

| 239 | Neu5Acα2-3Galβ1-4Glcβ–Sp0 | 5,792 | GM3 | |

| 231 | Neu5Acα2-3Galβ1-4(Fucα1-3)GlcNAcβ–Sp8 | 5,598 | 3′SLex | |

| 236 | Neu5Acα2-3Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ–Sp0 | 4,996 | 3′SLacNAc | |

| 259 | Neu5Gcα2-3Galβ1-4(Fucα1-3)GlcNAcβ-Sp0 | 4,644 | 3′SLex | |

| 261 | Neu5Gcα2-3Galβ1-4Glcβ–Sp0 | 4,145 | GM3 (Gc) | |

| 235 | Neu5Acα2-3Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-3Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-3Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ–Sp0 | 3,736 | 3′SiaLN-LN-LN | |

| 214 | Neu5Acα2-3GalNAcα–Sp8 | 3,645 | 3-SiaTn | |

| 237 | Neu5Acα2-3Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ–Sp8 | 3,554 | 3′SLec | |

| 264 | Neu5Gcα–Sp8 | 3,174 | N-glycolylneuraminic acid | |

| Group 4: Polysialic Acid | ||||

| 203 | Neu5Acα2-8Neu5Acα2-8Neu5Acα2-8Neu5Acα2-3(GalNAcβ1-4)Galβ1-4Glcβ-Sp0 | 52,721 | GQ2 | |

| 207 | Neu5Acα2-8Neu5Acα2-8Neu5Acα-Sp8 | 34,223 | c-series gangliosides | |

| 3 | Neu5Acα2-8Neu5Acα2-8Neu5Acβ-Sp8 | 16,066 | c-series gangliosides | |

| 205 | Neu5Acα2-8Neu5Acα2-8Neu5Acα2-3Galβ1-4Glcβ–Sp0 | 15,559 | GT3 | |

| 204 | Neu5Acα2-8Neu5Acα2-8Neu5Acα2-3(GalNAcβ1-4)Galβ1-4Glcβ-Sp0 | 4,882 | GT2 | |

| Biotinylated compounds | ||||

| B80 | Galβ1-4Glcβ–Sp0-NH-LC-LC-Biotin | Lactose | ||

| B83 | Neu5Acα2-3Galβ1-4Glcβ–Sp0-NH-LC-LC-Biotin | GM3 | ||

| B86 | Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4Glcβ–Sp0-NH-LC-LC-Biotin | |||

| B81 | Galβ1-3GlcNAcβ-Sp0-NH-LC-LC-Biotin | N-acetyl-lactosamine | ||

| B84 | Neu5Acα2-3Galβ1-3GlcNAcβ-Sp0-NH-LC-LC-Biotin | 3′SLec | ||

| B87 | Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-3GlcNAcβ-Sp0-NH-LC-LC-Biotin | 6′SLec | ||

| B108 | Neu5Acα2-8Neu5Acα2-8Neu5Acα2-3Galβ1-4Glcβ–Sp0-NH-LC-LC-Biotin | GT3 | ||

| B107 | Neu5Acα2-8Neu5Acα2-3Galβ1-4Glcβ–Sp0-NH-LC-LC-Biotin | GD3 | ||

Spacers (Sp) used to couple the glycans to the array surface matrix: Sp0 (-CH2CH2NH2), Sp8 (-CH2CH2CH2NH2), Sp12 (N=Asp), Sp13 (G), Sp14 (T), Sp20 (GENR), and Sp21 (-NHOCH2CH2NH2)

The first group represents sialylated bi-antennary compounds, which we have termed Sialo-N, where N stands for N-linked. These compounds are bi-antennary, with one or both of the branches possibly containing sialic acid. The structural characteristics of this group are common in complex N-linked glycans. The glycan co-crystallized with PTx in receptor binding studies was a member of this class (31). The Sialo-N group had 11 different glycans with an average RFU of 45,527 and included both Neu5Acα2-3 and Neu5Acα2-6 terminal linkages.

The second group consists of non-sialylated bi-antennary compounds, termed Asialo-N. The structural characteristics of this group are also commonly found in complex N-linked glycans. This group had 4 members with an average RFU of 15,511. The defining characteristic of this group is the lack of a terminal sialic acid. The Asialo-N group represents a departure from previous understanding of PTx binding to N-linked glycans, which was thought to be restricted to glycans bearing terminal sialic acid (21, 22, 24-26, 31, 44-47). Binding of PTx to Asialo-N compounds implies the existence of another binding mechanism which is both independent of the sialic acid binding and specific for components in complex N-linked glycans, which would explain the apparent preference seen in the literature for N-linked glycans despite the ubiquitous presence of sialic acid on mammalian cell surfaces.

The third group of compounds is defined by the shared pattern of Neu5Acα2-3(Lactose or N-acetyllactosamine), termed Sialo2-3Lac. This oligosaccharide sequence is sometimes found at the non-reducing end of sialylated bi-antennary N-linked glycans, but can also be found in O-linked glycans and glycolipids. The defining characteristics of this group of compounds are the distinctive α2-3 linkage for sialic acid and the lack of a branched mannose core found in N-linked glycans; thus their presentation as a ligand is more similar to O-linked glycans and glycolipids. This group had 22 members with an average RFU of 14,191. Variants of this group included six compounds with the N-glycolylneuraminic acid form of sialic acid. Each had an identical N-acetylneuraminic acid form also present on the array, for example compound 261 (Neu5Gcα2-3Galβ1-4Glcβ–Sp0) versus compound 239 (Neu5Acα2-3Galβ1-4Glcβ–Sp0). The RFU values of these two groups were not statistically different by Student's t-test (p=0.17), suggesting it is unlikely that these groups differ in binding mechanism. Additionally, as B pertussis is a strict human pathogen and since humans do not produce N-glycolylneuraminic acid (48, 49), the glycolyl subgroup is clinically irrelevant.

The fourth group of compounds, termed Polysialic Acid, is defined by the shared pattern of Neu5Acα2-8Neu5Acα2-8Neu5Ac which is seen in the c series gangliosides and polysialic acid-modified N-glycans. This group had 5 members with an average RFU of 24,690. A tri-sialic acid sequence appeared to be essential because the array included five compounds containing the di-sialic acid sequence, Neu5Acα2-8Neu5Ac, which did not display binding.

Concentration dependent binding of glycans

While positive binding at high concentrations of PTx (1,905 nM) provides a useful screening tool, concentration studies with the glycan array provides more relevant information on rank order throughout the dilution series. Pertussis toxin can reach 25 nM in static culture when grown in defined media (50); however, the achievable concentration of the toxin in the bloodstream is unknown. Positive binding for PTx occurred for 19 of 320 glycans at the 952 nM concentration, 17 at 476 nM, 15 at 191 nM (Figure 2B), and 3 at 48 nM. Useful data was not obtained at 10 nM. Members from all four groups exhibited binding down to 191 nM PTx concentration, but only Sialo-N compounds bound at 48 nM PTx. The binding profiles of the most avid compound in each of the four groups are shown in Figure 3.

Binding to Sialo-N and Asialo-N

Since binding to the Sialo-N group cannot be entirely distinguished from binding to the Asialo-N group, comparing a series of truncated bi-antennary compounds with identical linkers was informative (Figure 4). Compound 53, a bi-antennary glycan containing two terminal sialic acids (compound 53, Di-Neu5Acα2-6Gal) exhibited positive binding down to the 48 nM concentration (Figure 4A). Compound 52, lacking terminal sialic acids, displayed decreased binding compared to compound 53 at all concentrations. Similarly, compound 51, lacking the terminal galactose moieties, displayed less binding than compound 52, while compound 50, which consists of only the branched mannose core, did not display significant binding even at the highest concentration tested. This suggests that in addition to the terminal sialic acid residue, both the galactose and the N-acetylglucosamine are involved in binding. The involvement of these two carbohydrate residues is supported by the earlier work of Witvliet et al, which demonstrated the ability of galactose, N-acetylglucosamine, and disaccharides of both to inhibit PTx binding to the bovine serum glycoprotein fetuin (47).

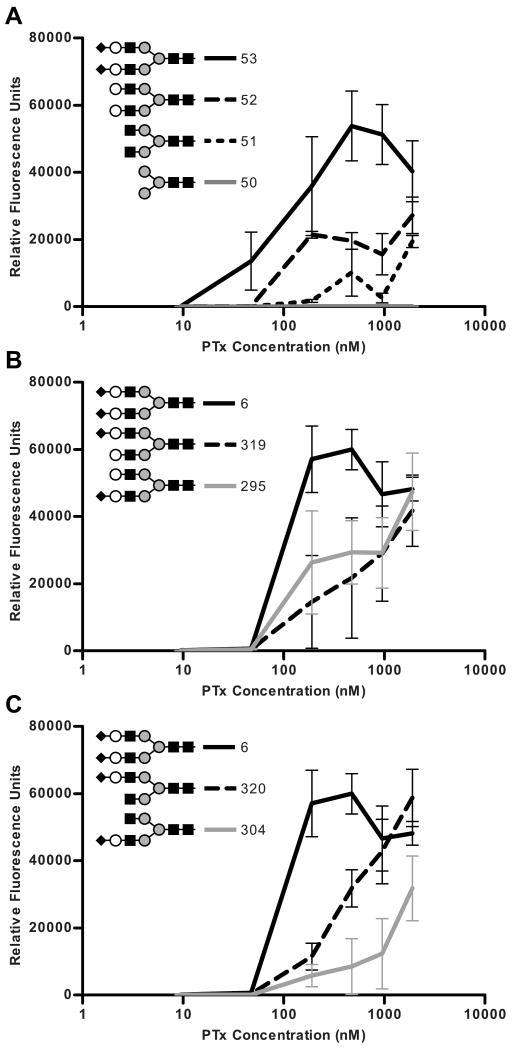

Figure 4.

Role of the terminal sialic acid and penultimate galactose in binding to Sialo-N group and Asialo-N group compounds. A, Glycan array data of PTx binding to compounds with progressive truncations occurring on both mannose branches. B, PTx binding to compounds with the terminal sialic acid truncated on only one mannose branch. C, PTx binding to compounds with both the terminal sialic acid and penultimate galactose truncated on only one mannose branch. All compounds were attached using the same linker.

Comparison of branch differences within the Sialo-N group can give insight into the recognition process. Removal of the sialic acid from either of the α1-6 mannose branch (compound 319) or the α1-3mannose branch (compound 295) resulted in equivalent reductions in binding (Figure 4B). Interestingly, while the removal of the galactose from the α1-6 mannose branch (compound 320) did not result in a further reduction in binding, the removal of the galactose from the α1-3 mannose branch (compound 304) did result in an additional reduction in binding (Figure 4C). This suggests that for Sialo-N compounds, the terminal sialic acids contribute to equally to binding, but the galactose from the α1-3 mannose branch contributes more to binding than the galactose from the α1-6 mannose branch.

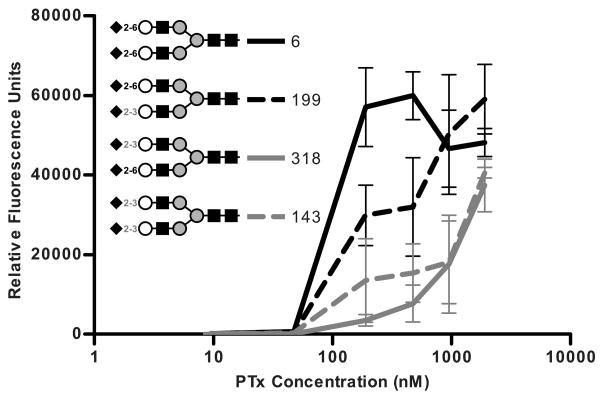

The presentation of the terminal sialic acid also appears to influence binding (Figure 5). The strongest binding (as defined by binding at 191 nM) occurred when both terminal sialic acids displayed α2-6 linkages (Figure 5, compound 6). Binding was somewhat reduced when the α1-3 mannose branch contained sialic acid in a α2-6 linkage and the α1-6 mannose branch contained sialic acid in a α2-3 linkage (Figure5, compound 199), but the presence of sialic acid in the α2-3 linkage on α1-6 mannose branch caused a severe decrease in binding regardless of the linkage on the α1-3 mannose branch (Figure 5, compounds 318 and 143). Taken together, the data suggests that at least two different modes of binding occur in Sialo-N compounds.

Figure 5.

Influence of the terminal sialic acid linkage in PTx binding to Sialo-N group compounds. Glycan array data of PTx binding to compounds with either α2-6 or α2-3 sialic acid linkages. All compounds were attached using the same linker.

Characterization of binding to synthetic Sialo-N analogs by surface plasmon resonance (SPR)

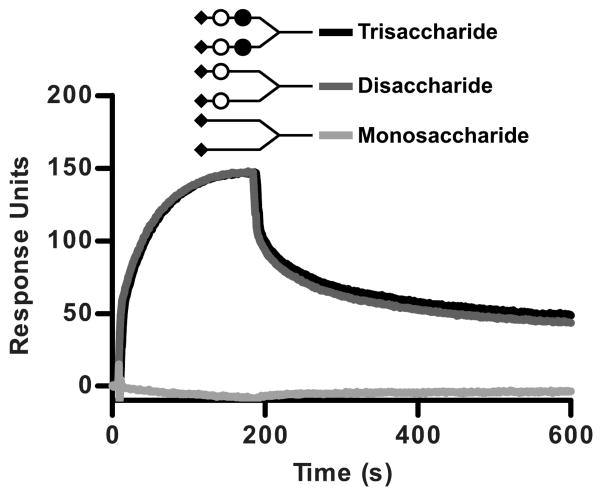

A reductive synthetic approach was used to examine the role of the non-terminal glycans in binding to the Sialo-N / Asialo-N groups. A series of synthetic bivalent glycans terminating in either a monosaccharide (Neu5Ac), a disaccharide (Neu5Acα2-6[S-linked]Gal), or a trisaccharide (Neu5Acα2-6[S-linked]Galβ1-4Glc) were attached to a commercially available streptavidin-coated sensor chip via a biotin molecule (Figure 6). Injection of PTx at 105 nM produced a robust binding response to both the disaccharide and the trisaccharide, while no binding to the monosaccharide was detected (Figure 6). These results support the findings in Figure 4A suggesting that both the sialic acid and the penultimate galactose are important determinants in the Sialo-N group.

Figure 6.

PTx binding to truncated Sialo-N group analogs by SPR. Sensograms of the monosaccharide (Neu5Ac), disaccharide (Neu5Acα2-6[S-linked]Gal), and trisaccharide (Neu5Acα2-6[S-linked]Galβ1-4Glc) synthetic bivalent glycan ligands with PTx (105 nM) injected as the analyte.

Kinetic analysis was attempted with the disaccharide and the trisaccharide using the data from several concentrations of PTx (13, 26, 52, and 105 nM); however, the 1:1, 1:2 and the 2:1 mathematical models supplied by Biaeval 2.0® software do not adequately fit the data, suggesting multivalent binding to sites with different affinities may be occurring.

Binding to Sialo2-3Lac

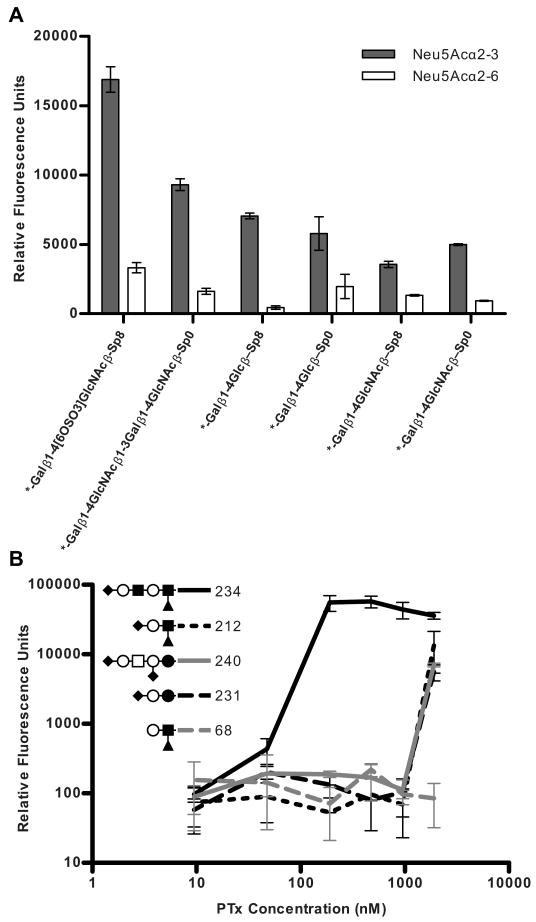

The compounds in the Sialo2-3Lac group included carbohydrates found on both O-linked glycans and a-series gangliosides. Unlike the Sialo-N group, the Sialo2-3Lac compounds lack the branched mannose core structure found in N-linked glycans, limiting the opportunity for multimodal interactions involving both sialic acid and the core structure. The sialyl LewisX blood group antigen (Neu5Acα2-3Galβ1-4(Fucα1-3)GlcNAc) was present in 8 of these compounds, including the sialyl LewisX isoform VIM-s/CDw65 (Table I). The terminal sialic acid is critical for binding, as none of the 15 asialyl LewisX compounds represented in the array bind PTx (for example, Figure 7B, compound 68).

Figure 7.

Influence of the terminal sialic acid in PTx binding to Sialo2-3Lac group compounds. A, Glycan array data of PTx (1,905 nM) binding to a series of paired compounds which only differ in the terminal sialic acid linkage at 1,905nM PTx. Grey bars represent compounds with a terminal α2-3 sialic acid linkage. White bars represent compounds with a terminal α2-6 sialic acid linkage. B, Glycan array data of PTx binding to several Sialo2-3Lac group compounds.

The terminal α2-3 linkage of the sialic acid was important for binding, since reduced binding was observed for compounds containing α2-6 linked sialic acid (Figure 7A). The most avid binder in the Sialo2-3Lac group was compound 234, VIM-s/CDw65 (Figure 7B). Binding to compound 231, the minimal sialyl LewisX unit and two glycans representative of the a-series gangliosides GD1a (212) and GM3 (240), was only detected at the highest concentration of PTx. Previous studies have reported that PTx can bind to ganglioside GD1a (51), although our studies suggest this is not a preferred ligand.

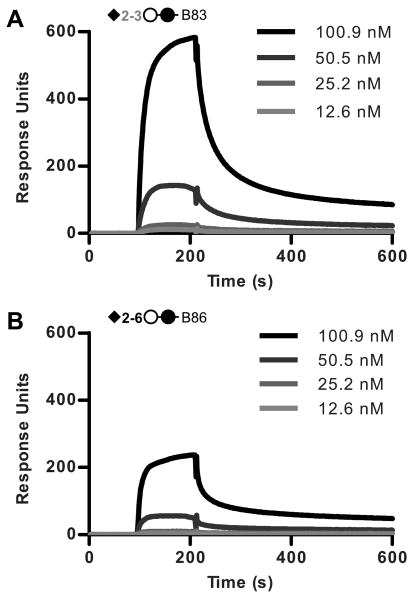

To verify the binding of positive hits in the glycan array, several of the synthetic carbohydrates utilized in the glycan array were obtained from the CFG Glycan Array Synthesis Core and binding was examined by SPR (Figure 8). Binding to the asialo compounds (Table I) B80 (Galβ1-4Glcβ) and B81 (Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ) was not detected and these compounds were used as negative controls on the chip. Injection of PTx at 100.9 nM produced strong binding responses to both the α2-3 linked sialic acid (B83) and the α2-6 linked sialic acid (B86) (Figure 8, A and B respectively).

Figure 8.

Influence of the terminal sialic acid linkage in PTx binding to Sialo2-3Lac group compounds by SPR. A, sensograms of PTx binding to compound B83 (Neu5Acα2-3Galβ1-4Glcβ). B, sensograms of PTx binding to compound B86 (Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4Glcβ).

The amount of toxin bound by Neu5Acα2-3Lactose was consistently 2.5-fold higher than that bound by Neu5Acα2-6Lactose at all concentrations of PTx tested (1.6, 3.2, 6.3, 12.6, 25.2, 50.5, and 100.9 nM). The N-acetyllactosamine containing compounds (B81, B84, and B87) were found to be similar to their lactose counterparts (B80, B83, and B86 respectively) (data not shown). Similar to the synthetic bivalent glycans, we could not fit the data to mathematical models to obtain quantitative values, and we could not obtain a stable equilibrium.

Binding to Polysialic Acid

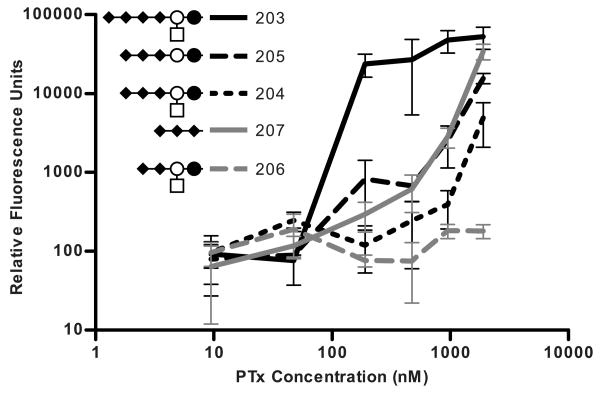

The compounds in the Polysialic Acid group included carbohydrates found on c-series gangliosides, but similar carbohydrate structures can be found on polysialic acid modified N-glycans. The c-series gangliosides are characterized by a succession of three sialic acid units joined together by α2-8 linkages attached to a lactoceramide core. The third linked sialic acid appears to be necessary for binding, as none of the compounds representative of the b-series gangliosides (containing two linked sialic acid residues) such as GD2 (compound 206) bound to PTx (Figure 9). Glycans representative of the c-series ganglioside derivatives, GQ2 (compound 203), GT3 (compound 205), GT2 (compound 204), and compound 207 bound to PTx (Figure 9). The most avid binder in the Polysialic Acid group was compound 203, the carbohydrate found on GQ2. RFU values at the 191 nM concentration for compound 203 were over 80-fold higher than compound 207, the minimal binding unit.

Figure 9.

Influence of the tri-sialic acid motif in PTx binding to c Ganglioside group compounds by glycan array.

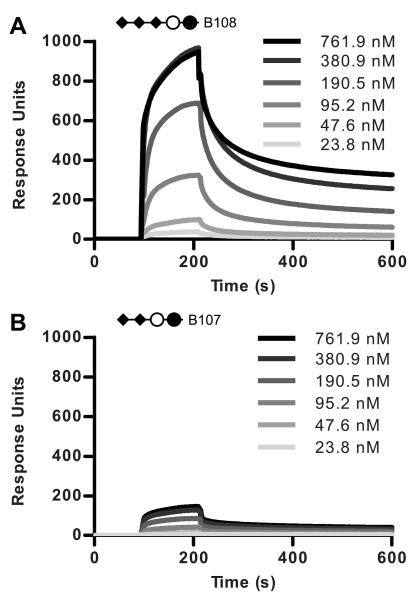

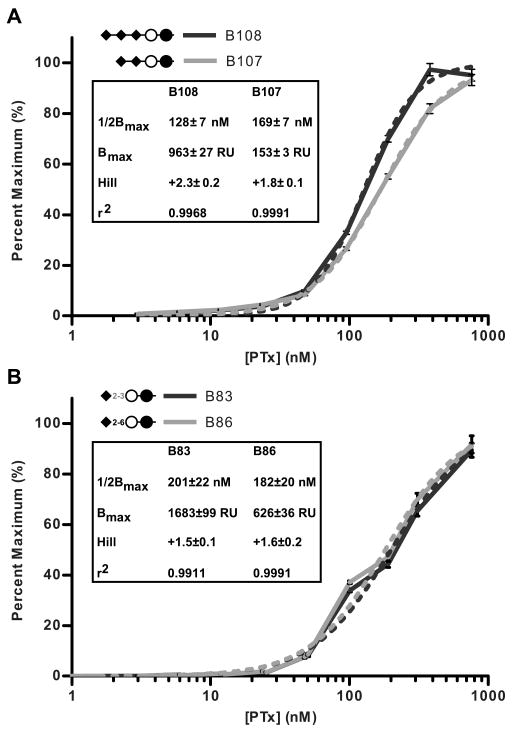

To verify the role of the third sialic acid in binding, compound B107 from the ganglioside b-series and compound B108 from the c-series were obtained from the CFG. Asialo compound B80 (Galβ1-4Glcβ-Sp0-Biotin) served as a negative control. In contrast to the array studies, injection of PTx at 100.9 nM produced clear binding responses to both the b-series di-sialic acid compound B107 (Figure 10B) and the c-series tri-sialic acid compound B108 (Figure 10A); however, the amount of toxin bound to the chip coupled with the c-series compound was over 4-fold higher than that bound by the b-series compound at all concentrations of PTx tested (3, 6, 12, 24, 48, 95, 191, 381, and 762 nM). Kinetic analysis could not be modeled with an appropriate fit. Analysis of the dissociation rates using the methods of Winzor (52) does strongly suggest that multivalent interactions are occurring, which is also true for the other compounds analyzed by SPR. Interestingly, when the data are plotted as percent maximum binding as a function of PTx concentration, the binding curves for the two compounds are very similar (Figure 11A). While true equilibrium was not achieved, pseudo-equilibrium analysis, performed by averaging of 50 second intervals approaching equilibrium, yielded binding curves which fit models with positive Hill coefficients (nH). Averaged intervals were fitted to a one-site specific binding model with Hill slope (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) to give a global affinity of 128±7 nM for B108, the c-series tri-sialic acid compound (r2=0.9968, nH=2.3) and 169±7 nM for B107, the b-series di-sialic acid compound (r2=0.9991, nH=1.8) (Figure 11A, insert). While these values can only be considered to be an approximation of global affinity, the data indicated that the global affinities of the c-series compound and the b-series compound for PTx were similar. In addition, when the data from SPR comparing the α2-3 and α2-6 linked compounds were also plotted as percent maximal binding as a function of PTx concentration, identical binding curves were obtained (Figure 11B), suggesting the global affinities for these two compounds were also similar. In support of the pseudo-equilibrium technique, when sequential 10-second interval averages beginning at the point of injection were analyzed, the calculated global affinity value obtained stabilized at the values reported above well before the 50-second interval used in the final analysis (data not shown). The fact that two compounds can bind with the same global affinity but have different binding capacities suggests that how the terminal sialic acid is displayed can influence the probability of the toxin encountering the carbohydrate in a conformation competent for binding.

Figure 10.

Influence of the tri-sialic acid motif in PTx binding to c Ganglioside group compounds by SPR. A, sensograms of PTx binding to compound B108 (Neu5Acα2-8Neu5Acα2-8Neu5Acα2-3Galβ1-4Glcβ) ligand. B, sensograms of PTx binding to compound B107 (Neu5Acα2-8Neu5Acα2-3Galβ1-4Glcβ).

Figure 11.

Para-equilibrium analysis of Sialo2-3Lac group and c Ganglioside group SPR experiments. Binding curves were generated by averaging of 50 second intervals approaching equilibrium from SPR sensograms. Curves were fit to a one site specific binding model with positive Hill coefficients (nH). Solid lines represent experimental data while dashed lines of the same color represent the fitted model for that data. The inset box lists parameters calculated from the model the coefficient of determination (r2), the Hill coefficients (nH), the calculated maximum bound (Bmax), and the global affinity (1/2Bmax). A, binding curves for compounds B108 (Neu5Acα2-8Neu5Acα2-8Neu5Acα2-3Galβ1-4Glcβ) and B107 (Neu5Acα2-8Neu5Acα2-3Galβ1-4Glcβ). B, binding curves for compounds B83 (Neu5Acα2-3Galβ1-4Glcβ) and B86 (Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4Glcβ).

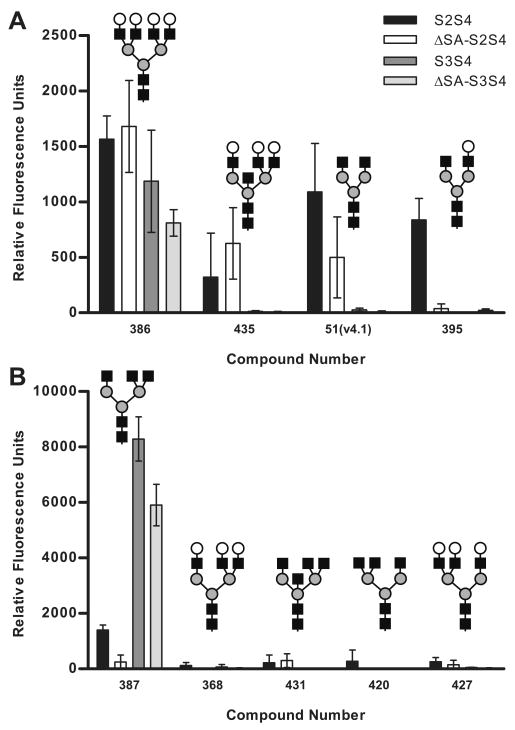

Glycans recognized by PTx subunit dimers

While the C-terminal sialic acid binding sites are well-characterized, the N-terminal binding sites are less well-defined. The fact that both S2 and S3 have nearly identical sialic acid binding sites has been a complication to understanding the evolutionary advantage for the bacterium to produce such a complex toxin. To determine the ligands for the N-terminal domains of S2 and S3, the following recombinant protein complexes were independently expressed in E coli: S2S4 dimer, S3S4 dimer, mutant ΔSA-S2S4 dimer, mutant ΔSA-S3S4 dimer, and S4 monomer. The ΔSA mutants of S2 and S3 carry the Y102A-Y103A mutation which eliminates the well-characterized sialic acid binding sites 2SA on S2 and 3SA on S3 (Figure 1)(27). Elimination of the sialic acid binding sites in the ΔSA mutants allows for the detection of binding mediated by other sites. Preliminary studies established that S2 and S3 were not efficiently expressed alone (data not shown), so the S2 and S3 subunits were co-expressed with the S4 subunit in order to stabilize S2 and S3, as well as to provide a uniform method for detection via a C-terminal 6×His tag introduced on S4. The co-expressed proteins migrated at 34 kDa by size exclusion chromatography, consistent with heterodimer formation, and bound to fetuin, suggesting proper folding and expression of the S2/S3 binding sites had occurred (data not shown).

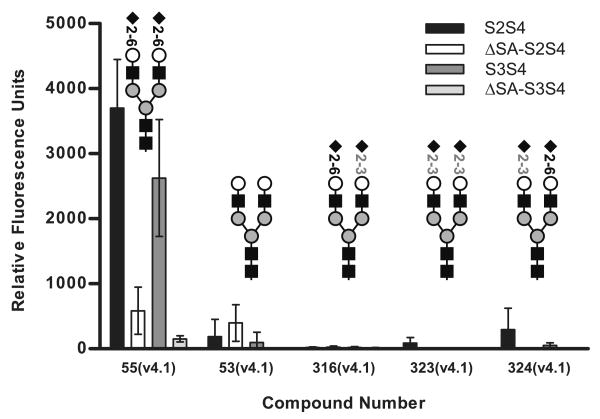

The four recombinant dimers and the S4 monomer were screened for binding to 465 structurally defined glycans utilizing the CFG glycan microarray (version 4.1) at 200 μg/ml (∼5,700 nM). Significant binding to the S4 monomer was not observed at 15,242 nM, and it served as a negative control. Overall the RFU values were reduced compared to the holotoxin (maximum for dimers = 8,287 RFU, maximum for holotoxin = 59,965 RFU), likely due to the loss of avidity associated with reduced binding sites. Positive binding to compounds representing 8 unique carbohydrate structures was observed (Table 2). All of these compounds possessed a branched mannose core, thus representing complex-type N-linked glycans. Binding occurred to both Sialo-N group and Asialo-N group compounds. Of the 8 Asialo-N compounds, 4 were bi-antennary, 2 were tri-antennary, and 2 were tetra-antennary. Except for the four A3 and A4 compounds, which were not represented on the 3.0 version of the array used for the holotoxin studies, all of the positive hits were also positive for the holotoxin. No significant binding to compounds in either the Sialo2-3Lac group or the Polysialic Acid group was observed, even though 3-fold more dimer was used than holotoxin, suggesting that recognition of these structures requires the full complement of binding sites.

Table 2. Glycans binding to PTx dimers.

| Glycan number |

Structure | Mean relative fluorescence units at 5700 nM |

Group | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S2S4 | ||||

| 55(v4.1) | Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp8* | 3702 | Sialo-N | |

| 57(v4.1) | -Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp13 | 2563 | Sialo-N | |

| 56(v4.1) | Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp12 | 557 | Sialo-N | |

| 54(v4.1) | Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-N(LT)AVL | 427 | Sialo-N | |

| 386 | Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2(Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4)Manα1-3(Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2(Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-6)Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp21 | 1566 | Asialo-N | |

| 387 | GlcNAcβ1-2(GlcNAcβ1-4)Manα1-3(GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAc-Sp21 | 1402 | Asialo-N | |

| 51(v4.1) | GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp12 | 1091 | Asialo-N | |

| 395 | Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAc-Sp12 | 838 | Asialo-N | |

| 427 | Galβ1-3GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(Galβ1-3GlcNAcβ1-2(Galβ1-3GlcNAcβ1-6)Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp19 | 256 | Asialo-N | |

| 52(v4.1) | GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp13 | 252 | Asialo-N | |

| ΔSA-S2S4 | ||||

| 55(v4.1) | Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp8 | 584 | Sialo-N | |

| 57(v4.1) | Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp13 | 403 | Sialo-N | |

| 56(v4.1) | Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp12 | 338 | Sialo-N | |

| 54(v4.1) | Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-N(LT)AVL | 160 | Sialo-N | |

| 386 | Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2(Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4)Manα1-3(Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2(Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-6)Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp21 | 1681 | Asialo-N | |

| 435 | Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4(Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2)Manα1-3(GlcNAcβ1-4)(Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAc-Sp21 | 627 | Asialo-N | |

| 51(v4.1) | GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp12 | 501 | Asialo-N | |

| 53(v4.1) | Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp12 | 398 | Asialo-N | |

| S3S4 | ||||

| 55(v4.1) | Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp8 | 2626 | Sialo-N | |

| 57(v4.1) | Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp13 | 1439 | Sialo-N | |

| 54(v4.1) | Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-N(LT)AVL | 880 | Sialo-N | |

| 387 | GlcNAcβ1-2(GlcNAcβ1-4)Manα1-3(GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAc-Sp21 | 8287 | Asialo-N | |

| 386 | Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2(Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4)Manα1-3(Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2(Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-6)Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp21 | 1187 | Asialo-N | |

| ΔSA-S3S4 | ||||

| 57(v4.1) | Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp13 | 158 | Sialo-N | |

| 55(v4.1) | Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp8 | 152 | Sialo-N | |

| 387 | GlcNAcβ1-2(GlcNAcβ1-4)Manα1-3(GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAc-Sp21 | 5905 | Asialo-N | |

| 386 | Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2(Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4)Manα1-3(Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2(Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-6)Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp21 | 812 | Asialo-N | |

Spacers (Sp) used to couple the glycans to the array surface matrix: Sp8 (-CH2CH2CH2NH2), Sp12 (N), Sp13 (G), Sp19 (EN or NK), Sp21 (-NHOCH2CH2NH2), and N(LT)AVL

All of the dimers bound to a series of compounds possessing the same glycan structure, a bi-antennary compound with sialic acid in a 2-6 linkage (Table 2). However binding varied considerably depending on the linker used to couple the glycan to the array surface matrix, for example 8-times more S2S4 dimer bound to compound 55(v4.1) attached with the Sp8 linker (-CH2CH2CH2NH2) compared to compound 54(v4.1) attached with the N(LT)AVL linker (Table 2). The dimers with mutations in the sialic acid binding sites, ΔSA-S2S4 and ΔSA-S3S4, bound this glycan (e.g. 55(v4.1)) less efficiently than the wild type dimers (Figure 12), but still achieved statistical significance. When binding to compound 53(v4.1), the asialo version of compound 55(v4.1) was examined, wild type dimers did not display increased binding compared to the mutants, however binding of the mutants was unaffected. These results suggest that the ability to engage the sialic acid was not essential for binding, but it could mediate increased binding. The improved binding of the wild type dimers is likely due to avidity, since the wild type dimer can engage more than one glycan. PTx holotoxin demonstrated a preference for terminal α2-6 linked sialic acid only in N-linked glycans, which also holds true for the dimers. Compounds 316, 323, and 324 which have a terminal α2-3linkage on one or both mannose branches bound over 10-fold less S2S4 and S3S4 than compound 55(v4.1) (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Influence of the terminal sialic acid linkage in recombinant dimers binding to Sialo-N group compounds. Glycan array data of PTx binding to compounds with either α2-6 or α2-3 sialic acid linkages.

The observation that PTx holotoxin, the wild type dimers, and the mutant dimers all have the capacity to bind non-sialylated complex-type N-linked glycans (Figure 13) demonstrates that the N-terminal binding sites of both S2 and S3 recognize a motif specific to complex-type N-linked glycans exclusive of sialic acid, and S2 and S3 possess slightly different binding preferences. All four dimers bound the asialo-tetra-antennary compound 386 with similar efficiently (Figure 13A), however dimers containing S2 bound to compound 435 and 51(v4.1) better than dimers containing S3, while only the wild type S2 dimer bound to compound 395. In contrast, glycan 387, an A3 compound in the Asialo-N group terminating in a mannose residues, displayed a preference for dimers containing either wild type or mutant S3 (Figure 13B), and this interaction was particularly strong. This binding could be impacted by minor structural alterations such as the addition of terminal Gal (compound 368), the addition of another GlcNAc (compound 431), or moving the third GlcNAc from the α1-3 branch to the α1-6 branch (compound 420). Understanding the differences in binding between S2 and S3 provide a foundation for the future exploration of the different roles of these subunits in human disease.

Figure 13.

Glycan array analysis of the recombinant dimers. Glycan array data of S4 monomer (15,242), S2S4, ΔSA-S2S4, S3S4, and ΔSA-S2S4 dimers (5,700 nM) binding to a series of Asialo-N group compounds. A, comparison of the binding to the remaining Asialo-N group compounds. B, comparison of the binding of compound 387 which strongly binds S3 to a set of similar compounds.

Discussion

PTx is able to bind several very distinct glycan ligands, including compounds representing both sialylated and non-sialylated N-glycans, sialylated O-glycans, and sialylated gangliosides. While PTx binding to sialic acid has been well described, our discovery of non-sialylated complex-type N-linked glycan binding sites on the S2 and S3 subunits furthers our understanding of PTx binding and activity. It has been known for decades that PTx seems to have a higher affinity for sialylated N-glycans compared to other sialylated glycans, which a sialic acid-only binding model fails to explain (21, 22, 24-26, 31, 44-47). The asialo N-glycan binding sites are likely located on the N-terminal APT domains of S2 and S3 (Figure 1), as the homologous domain of aerolysin has been shown to mediate N-glycan binding (53, 54); however, further experimentation is needed to determine the amino acids involved in mediating asialo N-glycan binding. Similarly to aerolysin, which can bind both N-glycans and GPI-anchored proteins by different domains, PTx also shows an intermediate level of toxicity to Lec1 CHO cells, which lack the N-acetylglucosamine transferase required for maturation of complex and hybrid-type N-glycans from oligomannose-type N-glycan precursors (44, 45, 47, 54). It is likely that the limitation to only sialic acid binding reduces the efficiency of intoxication compared to when N-glycan mediated binding is also available.

Remarkably, PTx shows distinct preferences for sialic acid residues with various glycosidic linkages, depending on the type of glycan: α2-6 linkages are preferred in N-glycans, α2-3 linkages in O-glycans/short glycolipids, and extended polyα2-8 linkages in higher order gangliosides. To our knowledge, this is the first report of such a high degree of pan-specificity for different types of glycans in a single lectin-like protein. The crystal structure of the 2SA and 3SA sites, occupied by Neu5Acα2-6Gal, fails to explain this level of complexity in sialic acid binding, as the penultimate galactose does not contact the toxin, and would not participate in binding. Modeling reveals that binding of a Neu5Acα2-3Gal disaccharide in these sites is possible (data not shown); however there are more restrictions to the torsion angles around the glycosidic bond for an α2-3 linkage than an α2-6 linkage. Likewise modeling of α2-8 linked sialic acid to the 2SA and 3SA sites is possible and would have even more flexibility than the α2-6 linkage (data not shown). Several lines of evidence suggest that these apparent differences in binding preference are not simply due to intrinsic affinity, but rather due to glycan presentation, or the conformational space occupied by a glycan. For example, the choice of linker used to immobilize the glycan on the array can have a major influence on binding to otherwise identical glycans. The effect of linker length and flexibility on binding capacity is well documented using synthetic glycans (43) and can be seen in the glycan array data (Tables 1 and 2).

The strongest support for the role of presentation comes from quantitative SPR studies (Figures 8 and 10), which demonstrate that while one ligand displays significantly higher maximum binding plateaus compared to the other, the normalized data revealed nearly identical global affinities (Figure 11). Given that binding is multivalent and each site requires the ligand to assume a specific conformation, we believe that differences in flexibility or conformational space explored by the various glycans can influence how many sites are available for binding. Specifically, PTx binding will occur only at those discrete locations where ligand conformational states simultaneously satisfy the requirements for multiple sites within the toxin. The α2-3 linked glycan shows higher PTx binding plateaus in SPR (Figure 8), and this glycan must present the critical binding epitope in a binding-competent configuration more often than the α2-6 linked glycan. Similarly, the additional flexibility or the longer length of the tri-sialic glycan chain results in more binding to the c-series compound B108 compared to the b-series compound B107 (Figure 10). This may be particularly important in SPR, since the biotinylated glycans were bound to streptavidin, which imposes a fixed distance between the reducing ends of adjacent glycans.

The preference for α2-3 linked versus α2-6 linked sialic acid is particularly interesting. While the more rigid α2-3 linkage is preferred in O-linked glycans and glycolipids which lack the N-glycan core structure (Figure 8, Figure 5), the flexible α2-6 linkage is preferred in N-linked glycans. The preference of N-linked glycans for α2-6 linked sialic acid in N-linked glycans can be explained by our discovery of additional, non-sialic acid binding sites that recognize the complex-type N-glycan core. In the case of N-linked glycans where both the sialic acid binding sites and N-glycan core binding sites can be engaged, the added flexibility of the α2-6 linkage is more conducive to multivalent interactions. This model is supported by the fact that only Sialo-N compounds bound at 48 nM in the PTx glycan array study, likely due to avidity effect of potential tetravalent interactions. Further, differences in the structures of the α1-3 mannose branch and the α1-6 mannose branch can also play a role in binding (Figure 12).

PTx acts as a lectin with remarkable plasticity. Significant specificity for various glycan types is achieved by judicious positioning of its four glycan binding sites: two sialic acid sites on the C-terminus of S2 and S3, and asialo N-glycan sites on the N-terminus of S2 and S3. While the N-terminal binding sites of S2 and S3 appear to have somewhat distinct preferences, the C-terminal sites engage only a single sialic acid residue, and presentation of the terminal sialic acid impacts the probability of PTx binding. These preferences have likely evolved to aid pathogenesis by directing PTx to useful target cell types. For example, the sialyltransferase ST6Gal-I, responsible for adding α2–6 linked sialic acid to N-glycans, is highly expressed in B cells (55). In addition, although most polysialic acid structures are confined to neural cells, sialyltransferase ST8Gal-I, responsible for adding α2–8 linked sialic acid to gangliosides, is expressed in T cells, and sialyltransferase ST8Gal-IV, responsible for adding α2–8 linked sialic acid to N-glycans, is expressed in most classes of leukocytes (56). PTx appears to be capable of intoxicating any mammalian cell type and has been used as a standard tool to study the role of G-protein coupled receptors in mammalian signaling processes. While the toxin may be capable of intoxicating almost any host cell type, it may be more probable for the toxin to affect cell types beneficial to the bacterium, such as those of the immune system.

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate the resources and collaborative efforts provided by The Consortium for Functional Glycomics funded by National Institute of General Medical Sciences [GM62116].

Abbreviations

- PTx

pertussis toxin

- Neu5Ac

N-Acetylneuraminic Acid

- Gal

galactose

- GalNAc

N-Acetylgalactosamine

- Glc

glucose

- GlcNAc

N-Acetylglucosamine

- Man

mannose

- Fuc

fucose

- RFU

relative fluorescence units

- SPR

surface plasmon resonance

- RU

response units

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 AI 064893 (A.A.W.), U01 AI 075498 (A.A.W. and S.S.I.), and NSF CAREER CHE-0845005 (S.S.I.).

References

- 1.CDC. Pertussis - United States, 1997-2000. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2002;51:73–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.CDC. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Vol. 54. 2005. Pertussis - United States, 2001-2003; pp. 1283pp. 1212–1286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiss AA, Hewlett EL, Myers GA, Falkow S. Pertussis toxin and extracytoplasmic adenylate cyclase as virulence factors of Bordetella pertussis. J Infect Dis. 1984;150:219–222. doi: 10.1093/infdis/150.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pittman M. Pertussis toxin: the cause of the harmful effects and prolonged immunity of whooping cough. A hypothesis, Rev Infect Dis. 1979;1:401–412. doi: 10.1093/clinids/1.3.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pittman M. The concept of pertussis as a toxin-mediated disease. Pediatr Infect Dis. 1984;3:467–486. doi: 10.1097/00006454-198409000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morse SI, Morse JH. Isolation and properties of the leukocytosis- and lymphocytosis-promoting factor of Bordetella pertussis. J Exp Med. 1976;143:1483–1502. doi: 10.1084/jem.143.6.1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lagergren J. The white blood cell count and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate in pertussis. Acta Paediatr. 1963;52:405–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1963.tb03798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tamura M, Nogimori K, Murai S, Yajima M, Ito K, Katada T, Ui M, Ishii S. Subunit structure of islet-activating protein, pertussis toxin, in conformity with the A-B model. Biochemistry. 1982;21:5516–5522. doi: 10.1021/bi00265a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katada T, Tamura M, Ui M. The A protomer of islet-activating protein, pertussis toxin, as an active peptide catalyzing ADP-ribosylation of a membrane protein. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1983;224:290–298. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(83)90212-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tamura M, Nogimori K, Yajima M, Ase K, Ui M. A role of the B-oligomer moiety of islet-activating protein, pertussis toxin, in development of the biological effects on intact cells. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:6756–6761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kong AS, Morse SI. The mitogenic responce of mouse lyphocytosis to the lymphocytosis-promoting factor (LPF) of Bordetella pertussis. Fed Proc. 1975;34:951. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosoff PM, Walker R, Winberry L. Pertussis toxin triggers rapid second messenger production in human T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1987;139:2419–2423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strnad CF, Carchman RA. Human T lymphocyte mitogenesis in response to the B oligomer of pertussis toxin is associated with an early elevation in cytosolic calcium concentrations. FEBS Lett. 1987;225:16–20. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)81123-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gray LS, Huber KS, Gray MC, Hewlett EL, Engelhard VH. Pertussis toxin effects on T lymphocytes are mediated through CD3 and not by pertussis toxin catalyzed modification of a G protein. J Immunol. 1989;142:1631–1638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stewart SJ, Prpic V, Johns JA, Powers FS, Graber SE, Forbes JT, Exton JH. Bacterial toxins affect early events of T lymphocyte activation. J Clin Invest. 1989;83:234–242. doi: 10.1172/JCI113865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sindt KA, Hewlett EL, Redpath GT, Rappuoli R, Gray LS, Vandenberg SR. Pertussis toxin activates platelets through an interaction with platelet glycoprotein Ib. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3108–3114. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.8.3108-3114.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu Q, Younson J, Griffin GE, Kelly C, Shattock RJ. Pertussis Toxin and Its Binding Unit Inhibit HIV-1 Infection of Human Cervical Tissue and Macrophages Involving a CD14 Pathway. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:1547–1556. doi: 10.1086/508898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang ZY, Yang D, Chen Q, Leifer CA, Segal DM, Su SB, Caspi RR, Howard ZO, Oppenheim JJ. Induction of dendritic cell maturation by pertussis toxin and its B subunit differentially initiate Toll-like receptor 4-dependent signal transduction pathways. Exp Hematol. 2006;34:1115–1124. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong WS, Simon DI, Rosoff PM, Rao NK, Chapman HA. Mechanisms of pertussis toxin-induced myelomonocytic cell adhesion: role of Mac-1(CD11b/CD18) and urokinase receptor (CD87) Immunology. 1996;88:90–97. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1996.d01-646.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li H, Wong WS. Mechanisms of pertussis toxin-induced myelomonocytic cell adhesion: role of CD14 and urokinase receptor. Immunology. 2000;100:502–509. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2000.00064.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Capiau C, Petre J, Van Damme J, Puype M, Vandekerckhove J. Protein-chemical analysis of pertussis toxin reveals homology between the subunits S2 and S3, between S1 and the A chains of enterotoxins of Vibrio cholerae and Escherichia coli and identifies S2 as the haptoglobin-binding subunit. FEBS Lett. 1986;204:336–340. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(86)80839-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sekura RD, Zhang Y. Pertussis toxin: structural elements involved in the interaction with cells. In: Sekura RD, Moss J, Vaughan M, editors. Pertussis Toxin. Academic Press, Inc.; Orlando, FL: 1985. pp. 45–64. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Francotte M, Locht C, Feron C, Capiau C, De Wilde M. Monoclonal antibodies specific for pertussis toxin subunits and identification of the haptoglobin-binding site. In: Lerner RA, Ginsberg H, Chanock RM, Brown F, editors. Vaccines. Vol. 89. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1989. pp. 243–247. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cumming DA, Hellerqvist CG, Harris-Brandts M, Michnick SW, Carver JP, Bendiak B. Structures of asparagine-linked oligosaccharides of the glycoprotein fetuin having sialic acid linked to N-acetylglucosamine. Biochemistry. 1989;28:6500–6512. doi: 10.1021/bi00441a051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heerze LD, Armstrong GD. Comparison of the lectin-like activity of pertussis toxin with two plant lectins that have differential specificities for alpha (2-6) and alpha (2-3)-linked sialic acid. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;172:1224–1229. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)91579-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gomez SR, Xing DK, Corbel MJ, Coote J, Parton R, Yuen CT. Development of a carbohydrate binding assay for the B-oligomer of pertussis toxin and toxoid. Anal Biochem. 2006;356:244–253. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loosmore S, Zealey G, Cockle S, Boux H, Chong P, Yacoob R, Klein M. Characterization of pertussis toxin analogs containing mutations in B-oligomer subunits. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2316–2324. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.6.2316-2324.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmidt W, Schmidt MA. Mapping of linear B-cell epitopes of the S2 subunit of pertussis toxin. Infect Immun. 1989;57:438–445. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.2.438-445.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmidt MA, Schmidt W. Inhibition of pertussis toxin binding to model receptors by antipeptide antibodies directed at an antigenic domain of the S2 subunit. Infect Immun. 1989;57:3828–3833. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.12.3828-3833.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmidt MA, Raupach B, Szulczynski M, Marzillier J. Identification of linear B-cell determinants of pertussis toxin associated with the receptor recognition site of the S3 subunit. Infect Immun. 1991;59:1402–1408. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.4.1402-1408.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stein PE, Boodhoo A, Armstrong GD, Heerze LD, Cockle SA, Klein MH, Read RJ. Structure of a pertussis toxin-sugar complex as a model for receptor binding. Nat Struct Biol. 1994;1:591–596. doi: 10.1038/nsb0994-591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lobet Y, Feron C, Dequesne G, Simoen E, Hauser P, Locht C. Site-specific alterations in the B oligomer that affect receptor-binding activities and mitogenicity of pertussis toxin. J Exp Med. 1993;177:79–87. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.1.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rozdzinski E, Burnette WN, Jones T, Mar V, Tuomanen E. Prokaryotic peptides that block leukocyte adherence to selectins. J Exp Med. 1993;178:917–924. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.3.917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sandros J, Rozdzinski E, Zheng J, Cowburn D, Tuomanen E. Lectin domains in the toxin of Bordetella pertussis: selectin mimicry linked to microbial pathogenesis. Glycoconj J. 1994;11:501–506. doi: 10.1007/BF00731300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saukkonen K, Burnette WN, Mar VL, Masure HR, Tuomanen EI. Pertussis toxin has eukaryotic-like carbohydrate recognition domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:118–122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.1.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pizza M, Bartoloni A, Prugnola A, Silvestri S, Rappuoli R. Subunit S1 of pertussis toxin: mapping of the regions essential for ADP-ribosyltransferase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:7521–7525. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.20.7521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pizza M, Covacci A, Bartoloni A, Perugini M, Nencioni L, De Magistris MT, Villa L, Nucci D, Manetti R, Bugnoli M, et al. Mutants of pertussis toxin suitable for vaccine development. Science. 1989;246:497–500. doi: 10.1126/science.2683073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zocchi MR, Contini P, Alfano M, Poggi A. Pertussis toxin (PTX) B subunit and the nontoxic PTX mutant PT9K/129G inhibit Tat-induced TGF-beta production by NK cells and TGF-beta-mediated NK cell apoptosis. J Immunol. 2005;174:6054–6061. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sato H, Ito A, Chiba J, Sato Y. Monoclonal antibody against pertussis toxin: effect on toxin activity and pertussis infections. Infect Immun. 1984;46:422–428. doi: 10.1128/iai.46.2.422-428.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sato H, Sato Y. Protective activities in mice of monoclonal antibodies against pertussis toxin. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3369–3374. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.10.3369-3374.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sato H, Sato Y, Ito A, Ohishi I. Effect of monoclonal antibody to pertussis toxin on toxin activity. Infect Immun. 1987;55:909–915. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.4.909-915.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kale RR, Mukundan H, Price DN, Harris JF, Lewallen DM, Swanson BI, Schmidt JG, Iyer SS. Detection of intact influenza viruses using biotinylated biantennary S-sialosides. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:8169–8171. doi: 10.1021/ja800842v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lewallen DM, Siler D, Iyer SS. Factors affecting protein-glycan specificity: effect of spacers and incubation time. Chembiochem. 2009;10:1486–1489. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brennan MJ, David JL, Kenimer JG, Manclark CR. Lectin-like binding of pertussis toxin to a 165-kilodalton Chinese hamster ovary cell glycoprotein. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:4895–4899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.el Baya A, Bruckener K, Schmidt MA. Nonrestricted differential intoxication of cells by pertussis toxin. Infect Immun. 1999;67:433–435. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.1.433-435.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Francotte M, Locht C, Feron C, Capiau C, de Wilde M. Monoclonal antibodies specific for pertussis toxin subunits and identification of the haptoglobin-binding site. In: Lerner RA, Ginsberg H, Chanock RM, Brown F, editors. Vaccines. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: 1989. pp. 243–247. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Witvliet MH, Burns DL, Brennan MJ, Poolman JT, Manclark CR. Binding of pertussis toxin to eucaryotic cells and glycoproteins. Infect Immun. 1989;57:3324–3330. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.11.3324-3330.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chou HH, Takematsu H, Diaz S, Iber J, Nickerson E, Wright KL, Muchmore EA, Nelson DL, Warren ST, Varki A. A mutation in human CMP-sialic acid hydroxylase occurred after the Homo-Pan divergence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:11751–11756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Irie A, Koyama S, Kozutsumi Y, Kawasaki T, Suzuki A. The molecular basis for the absence of N-glycolylneuraminic acid in humans. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:15866–15871. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.25.15866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rambow-Larsen AA, Weiss AA. Temporal expression of pertussis toxin and Ptl secretion proteins by Bordetella pertussis. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:43–50. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.1.43-50.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hausman SZ, Burns DL. Binding of pertussis toxin to lipid vesicles containing glycolipids. Infect Immun. 1993;61:335–337. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.1.335-337.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kalinin NL, Ward LD, Winzor DJ. Effects of solute multivalence on the evaluation of binding constants by biosensor technology: studies with concanavalin A and interleukin-6 as partitioning proteins. Anal Biochem. 1995;228:238–244. doi: 10.1006/abio.1995.1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hong Y, Kang JY, Kim YU, Shin DJ, Choy HE, Maeda Y, Kinoshita T. New mutant Chinese hamster ovary cell representing an unknown gene for attachment of glycosylphosphatidylinositol to proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;335:1060–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.07.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hong Y, Ohishi K, Inoue N, Kang JY, Shime H, Horiguchi Y, van der Goot FG, Sugimoto N, Kinoshita T. Requirement of N-glycan on GPI-anchored proteins for efficient binding of aerolysin but not Clostridium septicum alpha-toxin. Embo J. 2002;21:5047–5056. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Crocker PR, Paulson JC, Varki A. Siglecs and their roles in the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:255–266. doi: 10.1038/nri2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Avril T, North SJ, Haslam SM, Willison HJ, Crocker PR. Probing the cis interactions of the inhibitory receptor Siglec-7 with alpha2,8-disialylated ligands on natural killer cells and other leukocytes using glycan-specific antibodies and by analysis of alpha2,8-sialyltransferase gene expression. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80:787–796. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1005559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]