Abstract

Performance of repetitive finger movements is an important clinical measure of disease severity in patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) and is associated with a dramatic deterioration in performance at movement rates near 2 Hz and above. The mechanisms contributing to this rate-dependent movement impairment are poorly understood. Since clinical and experimental testing of these movements involve prolonged repetition of movement, a loss of force generating capacity due to peripheral fatigue may contribute to performance deterioration. This study examined the contribution of peripheral fatigue to the performance of unconstrained index finger flexion movements by measuring maximum voluntary contractions (MVC) immediately before and after repetitive finger movements in patients with PD (both off- and on-medication) and matched control subjects. Movement performance was quantified using finger kinematics, maximum force production, and electromyography (EMG). The principal finding was that peak force and EMG activity during the MVC did not significantly change from the pre- to post- movement task in patients with PD despite the marked deterioration in movement performance of repetitive finger movements. These findings show that the rate-dependent deterioration of repetitive finger movements in PD cannot be explained by a loss of force-generating capacity due to peripheral fatigue, and further suggest that mechanisms contributing to impaired isometric force production in PD are different from those that mediate impaired performance of high-rate repetitive movements.

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, repetitive movements, force, fatigue

Bradykinesia (slowness of movement) and the accompanying hypokinesia (reduced movement amplitude) have significant impact on activities of daily living in patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) [5, 23]. One of the primary clinical measures of bradykinesia is the performance of repetitive movements (Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale, UPDRS, items 23, 24, 25 and 26) [9]. During clinical assessment, patients are instructed to move as fast and wide as possible. When patients perform the task at high movement rates, the impairment is markedly worse than when it is performed at low rates. Quantitative studies have shown that deterioration of repetitive movement performance occurs when movement rate nears 2 Hz and above [18, 20, 28] and is characterized by a marked increase in movement rate, reduced movement amplitude, and increased variance in phase and inter-movement interval [6, 18, 20, 28]. These changes in performance are considered to reflect a disordered supraspinal drive to muscles due to dysfunction of the basal ganglia. However, since dopamine replacement therapy does not improve performance [20, 28], the mechanisms contributing to this impairment remain poorly understood.

Quantitative studies that assessed deterioration of repetitive movements have used tasks that require subjects to perform a long series of movements [18–20, 26, 28]. These long duration paradigms leave the possibility that the marked deterioration of repetitive movements at higher rates may be the result of a loss of force generating capacity due to peripheral fatigue. Exercise studies have shown that patients with PD fatigue earlier than matched control subjects [13, 32]. Force generating capacity in patients with PD, particularly at high movement rates, could also be exacerbated by deficits in the rate of onset, offset and peak force production [3, 12, 22, 29–30]. Moreover, impairments in the maintenance and temporal control of isometric contractions of the upper limb have been shown to be correlated with clinical measures of bradykinesia [7, 11, 22], suggesting that peripheral fatigue may contribute to impaired repetitive finger movements. Indirect evidence opposing this suggestion comes from early quantitative studies by Schwab and colleagues [26]. In these studies, patients showed a marked decrement in movement amplitude over time yet retained the capacity to return to the initial movement amplitude when urged to make a “strong effort” or with electrical stimulation of the muscle. However, the required movement rate was not specified or controlled so it is unclear if this was a rate-dependent phenomenon [26].

The purpose of this study was to examine whether a reduction in the capacity to produce maximal force accounts for rate-dependent impairments in repetitive finger movements. An incremental frequency task (IFT) [16–17, 28] was used with MVCs collected immediately preceding and following the IFT. We hypothesized: (1) patients with PD would show a marked impairment in movement performance at movement rates near 2 Hz and above, and (2) peak force in patients with PD would be lower compared to control subjects, but would not differ between pre- and post-MVC measurements.

Data were collected from 9 patients with idiopathic PD (65 ± 8 years), and 9 control subjects (65 ± 8 years) matched in age (± 3 years), gender, and handedness. Inclusion criteria for patients with PD were: 1) history of a good response to levodopa, 2) akinetic rigidity in the upper limb (score of 2 or greater on items 23–25 of the UPDRS), 3) little to no resting tremor (UPDRS resting or action tremor score less than 2), and 4) no history of additional neurological, cognitive, psychological or musculoskeletal conditions. Patients were tested after a 12-hour withdrawal from antiparkinson medications and again one hour after taking 1 ½ times their normal morning dose of levodopa. The motor section of the UPDRS was used to assess disease severity prior to data collection in both medication states. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and all subjects gave their written informed consent prior to inclusion into the study. The Institutional Review Board of Northwestern University approved the procedures.

Subjects were seated with their forearm and hand supported by a brace positioning the arm horizontal, palm downward, and restricting movement of the thumb and fingers 3 through 5. Subjects with PD used their most affected hand, and control subjects used the same hand as their matched counterpart. A force transducer secured to a movable block was placed in the optimal flexion position for each subject. Subjects were instructed to press down on the force transducer as hard as possible with the index finger using only the finger muscles for the duration of a 5 second tone (500 Hz, 80 dB) (pre-MVC). The force transducer was removed, and the series of tones (50 ms, 500 Hz, 80 dB) for the IFT were immediately initiated. Immediately following the IFT, a second MVC, identical to the first, was performed (post-MVC) (Figure 1). The IFT consisted of 15 tones presented at a starting rate of 1 Hz, incremented by 0.25 Hz and maintained for 15 intervals until reaching 3 Hz [16–17, 28]. A total of 135 tones within 75 seconds were presented for each trial. Two IFT conditions were tested: listen and move. For the listen condition, subjects listened to the tones, and for the move condition, subjects performed an index finger flexion movement on each tone. No constraints were placed on movement amplitude, and no external feedback was given. Eight listen and move trials were collected and conditions were alternated between trials. Subjects were given 1–3 practice trials and 2 minutes of rest between trials.

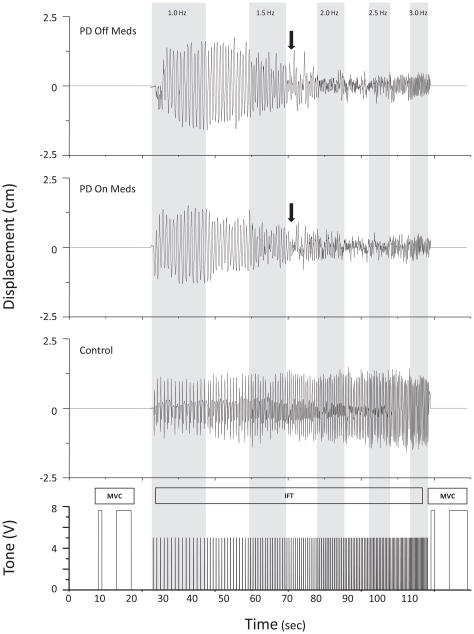

FIG. 1.

Paradigm and raw position data shown from one subject with PD off and on levodopa, and one control subject. Arrows indicate where movement performance deteriorated.

Bipolar surface EMG were recorded from the first dorsal interossieous (FDI) and extensor digitorum communis (EDC). EMG signals were amplified (gain of 2000) and filtered (30–1000 Hz) (Grass P511, Grass Technologies). Force was measured using a load cell (range = 0–50N, Entran ELFS-50N-C10003) and amplified (Entran PS-30A, output 0–10V). Finger movement was measured using a tri-axial accelerometer placed on the dorsum of the middle phalanx of the index finger (Measurement Specialties EGAXT3-15-/L2M) and amplified (gain of 200) (Measurement Specialties Model 101). All signals were digitized with a 16-bit analogue-to-digital converter and sampled at 2000 Hz using a data acquisition system (Power 1401 and Signal 2 software, Cambridge Electronic Design, UK).

Peak force was measured by selecting the point of maximum steady state force output during each MVC. EMG signals were DC corrected and full-wave rectified. The area under the curve was integrated from 500 msec before and after peak force and normalized to EMG activity during the listen/pre condition. Both peak force and normalized EMG activity was averaged across trials for listen/pre, listen/post, move/pre, and move/post trials.

The acceleration signal was notch filtered (60 Hz) and high-pass filtered (2nd-order dual-pass Butterworth, 2 Hz cut-off). Finger displacement was derived by double integrating the acceleration signal using Simpson’s rule. Movement rate was calculated from the timing of each peak flexion displacement. Peak-to-peak amplitude of the displacement signal was calculated for each movement and normalized to data at 1 Hz, allowing for comparisons of the relative change in movement amplitude across rates and between subjects. Movement phase was determined from the time of peak flexion displacement to the nearest tone. The standard deviation (SD) of phase was calculated with respect to a mean phase of zero degrees. All measures were averaged across each tone rate and across subjects.

To analyze MVCs, a three-factor repeated measures analysis of variance was used to determine differences between groups (PDOFF vs. PDON; PDOFF vs. controls; PDON vs. controls), across conditions (move, listen, medication), and across time (pre-, post-MVC) for each dependent measure (peak force, EMG area). To analyze IFT move trials, a two-factor repeated measures analysis of variance was used to determine differences between groups (PDOFF vs. PDON; PDOFF vs. controls; PDON vs. controls) and across tone rates (1–3 Hz) for each dependent measure (movement rate, amplitude, SD of phase). Interaction effects were tested using Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference tests. Paired samples t-tests were completed for UPDRS comparisons.

There was a significant effect of levodopa (t = 4.608, p = 0.002) on the UPDRS total motor score (mean ± SE Off-Meds = 31.4 ± 2.4; ON-Meds = 23.2 ± 2.1), but there was no effect of medication on UPDRS measure of finger taps (t = 1.000, p = 0.347; OFF-Meds = 1.9 ± 0.3; ON-Meds = 1.8 ± 0.3).

Examples of movement performance for the IFT are shown in Figure 1 for one subject with PD and one control subject. In both medication states, the subject with PD showed intermittent periods of decreased movement amplitude and loss of phase at 1.75 Hz. Once reaching 2.0 Hz, there was marked deterioration in movement performance characterized by increased movement rate, decreased movement amplitude, and loss of phase. In contrast, the control subject was able to maintain the appropriate movement rate, amplitude, and phase up to 3.0 Hz.

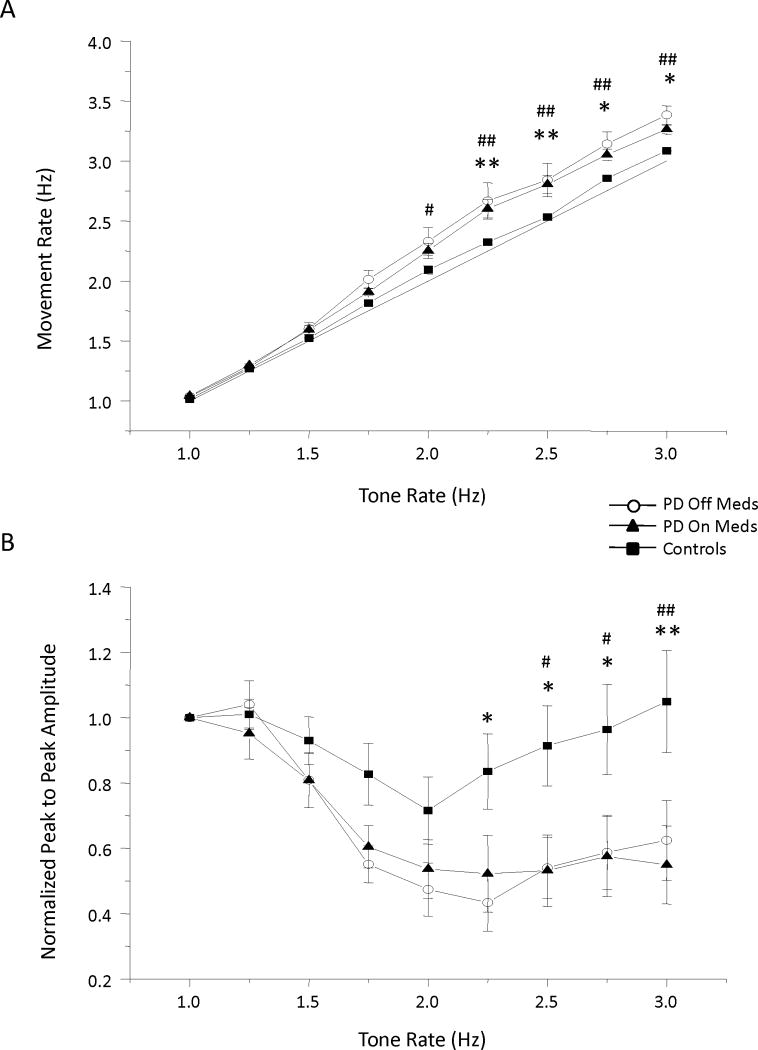

Across all subjects with PD, movement rate, amplitude, and phase deteriorated at approximately 1.75 Hz and were not improved with levodopa. The deficits in movement rate amplitude are shown in Figure 2. Significant main effects of group (F (1) > 5.247, p < 0.025) and tone rate (F (8) > 7.21, p <0.001) were observed for comparisons between both PD groups and the control group for the variables of movement rate, amplitude and SD of phase. Significant interaction effects for movement rate and amplitude were also observed (F (8) > 2.65, p < 0.01). Post-hoc analysis revealed that the PDOFF group significantly differed from the control group at 2.25 Hz and above for both movement rate (Figure 2A) and amplitude (Figure 2B) (p < 0.05), and the PDON group significantly differed from controls at 2.0 Hz and above for movement rate (Figure 2A) and 2.5 Hz and above for movement amplitude (Figure 2B) (p < 0.05). Comparisons between the PDOFF and PDON groups revealed a main effect of tone rate (F (8) > 6.401, p < 0.001) and no main effect of levodopa (F (1) < 1.67, p > 0.233) for all three measures.

FIG. 2.

Mean and standard error for (A) movement rate, and (B) normalized peak to peak amplitude. * = PDOFF and controls, # = PDON and controls, */# p < 0.05, **/## p < 0.01.

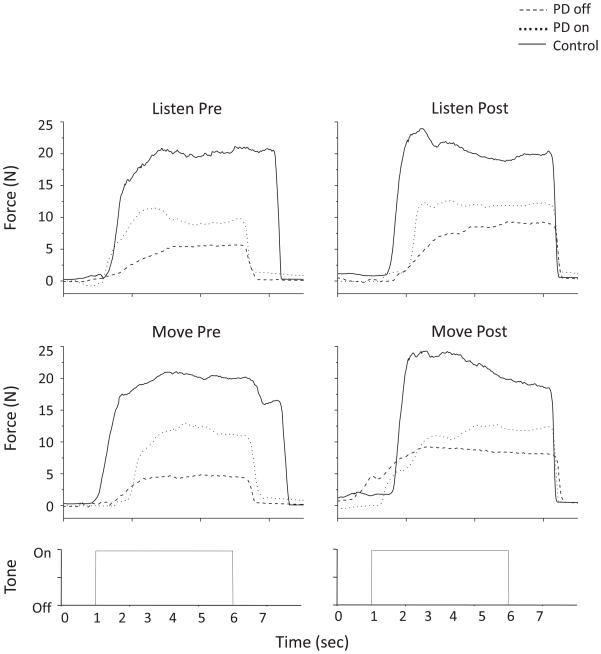

Figure 3 shows isometric MVC force trace examples for each condition for one subject with PD and one control subject. In the off medication state, the level of force produced by the subject with PD was much lower compared to the control subject. Levodopa moderately improved the level of force but not to the level of the control subject. However, force production was relatively consistent across all conditions (listen/pre, listen/post, move/pre, move/post) for both subjects.

FIG. 3.

Force trace data shown from one subject with PD off and on levodopa, and one control subject for each condition.

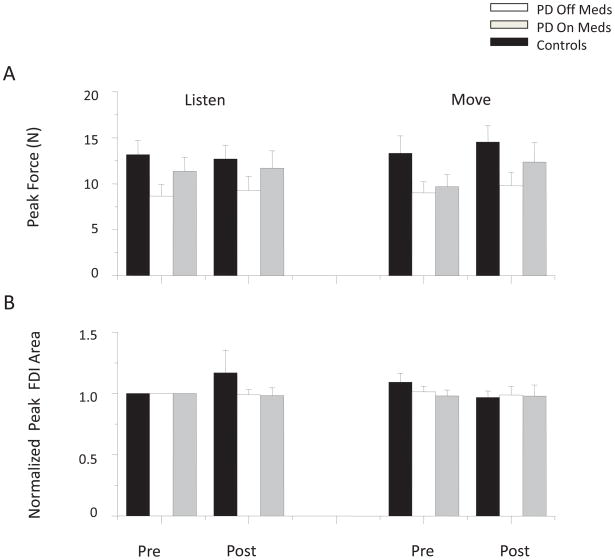

Average peak force during MVC and EMG area for the FDI muscle across PD groups and the control group are shown in Figure 4. No main effects of group (F (1) = 4.081, p = 0.06) or time (F (1) = 3.064, p = 0.099) were observed in average peak force comparisons between the PDOFF and control groups, however there was a main effect of condition (F (1) = 5.420, p = 0.033). Peak force comparisons between the PDON and control groups revealed no significant main effects of group (F (1) = 0.839, p = 0.373) or condition (F (1) = 0.592, p = 0.453), but there was an effect of time (F (1) = 5.905, p = 0.027). Post hoc analysis revealed that significant differences in condition (PDOFF and control groups) and time (PDON and control groups) reflect a significant increase in peak force in the move/post condition for all groups (p < 0.05). Although the mean peak forces were higher in the ON medication states, no significant main effects were observed between PD groups for the factors of medication, condition, or time (F(1) < 5.028, p > 0.055). Similarly, there were no significant differences in normalized FDI or EDC peak EMG area across groups, conditions, or times (F (1) < 2.77, p > 0.134).

FIG. 4.

Mean and standard error for (A) peak force, and (B) peak FDI area.

The principal finding was that impairments in performance of repetitive finger movements near and above 2 Hz in the patients with PD could not be attributed to a loss of force generating capacity. This finding supports the hypothesis that disordered supraspinal drive, not peripheral fatigue, contributes to the rate-dependent impairment in repetitive finger movements in patients with PD.

Our results are in keeping with observations from Schwab and colleagues [26]. During finger abduction movement against a load, movement amplitude decreased over time, but was substantially restored when subjects were instructed to make a “strong effort”. Moreover, decrements in movement amplitude during voluntary repetitive movements were greater than those observed with repetitive electrical stimulation of the muscle. These findings suggest that weakness was not the cause of movement impairment. However, movement rate was not reported so it is difficult to discern if the impairment was rate-dependent [26].

Contributions of peripheral fatigue to the control of high-rate finger movements have been studied in healthy adults. Rodrigues and colleagues [24] showed marked decrements in performance occurring shortly after the initiation of index finger flexion-extension movements performed “as fast as possible”. Unlike patients with PD, reduced performance was observed in healthy adults at movement rates near 5 Hz. Similar to our findings, MVCs measured within 1 second after completion of the task did not change from baseline. This would suggest that a similar breakdown in supraspinal drive, and not peripheral fatigue, may account for the change in movement performance in patients with PD but at considerably lower movement rates.

Previous studies have shown that isometric force production is impaired in patients with PD, is improved following the administration of levodopa, and is associated with improved clinical measures of bradykinesia [1–3, 7, 11, 22, 25]. In contrast, the administration of levodopa was associated with an increase in peak isometric force production of 23%, but the differences did not reach significance. In keeping with our previous study [28], the performance of high-rate finger movements also did not significantly improve with levodopa. This is in contrast to a study showing that levodopa improved both force generation and performance of finger tapping in patients with PD [13]. However, this discrepancy is likely explained by differences in task and outcome measures. Patients were required to perform two movement tasks, tapping two targets as fast as possible and repeated cycles of force generation using wrist extensors, a muscle not highly involved in finger tapping. Performance in both tasks was improved with levodopa, but there was no direct measure of fatigue following the tapping task [13].

The differential performance on isometric contraction and repetitive movements in patients with PD may be due to separate cortical and subcortical networks involved in these tasks. Control of graded force tasks may predominantly involve the primary motor cortex [15], while rate-dependent tasks may involve greater contribution from premotor regions [14, 24]. Moreover, fast ballistic force production requires less metabolic demand from the basal ganglia when compared to movements that require internal regulation of rate of force change (i.e. repetitive movements) [31]. EMG evidence has also shown that the frequency structure of neuromuscular organization differs between low-rate and high-rate repetitive movements [27], suggesting a differential control of force during repetitive movements. Thus in patients with PD, isometric force production and low-rate repetitive movements may be controlled by a system that requires less demand on the basal-ganglia thalamocortical pathways. When reaching a movement rate that requires a greater demand on the impaired system, movement performance dramatically deteriorates. If basal ganglia-thalamocortical and premotor pathways play an important role in high-rate repetitive movements, then antiparkinson medications that improve movement-related activity in these areas in patients with PD [4, 8, 10] should be associated with improvements in repetitive finger movements near or above 2 Hz. However, similar to our previous work [28], repetitive finger movements near or above 2 Hz did not significantly improve with levodopa. In contrast, Penn and colleagues [21] have shown that inhibiting the globus pallidus internal with muscimol improves performance of repetitive hand movements over time. This would suggest that impaired basal-ganglia thalamocortical pathways may be involved with repetitive movement tasks but may not be fully restored with medication.

In conclusion, the results of this study show that impairments in quantitative measures of bradykinesia cannot be accounted for by a loss of force generating capacity due to peripheral muscle fatigue. These findings further support a differential motor control of isometric force production and high frequency repetitive movements.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by NIH Grant R01 NS054199. We thank the study volunteers and Christopher Robinson for help in the construction of the hand orthoses.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Brown P. Cortical drives to human muscle: the Piper and related rhythms. Prog Neurobiol. 2000;60:97–108. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(99)00029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown P, Corcos D, Rothwell JC. Does parkinsonian action tremor contribute to muscle weakness in Parkinson’s disease? Brain. 1997;120:401–408. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.3.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corcos D, Chen CM, Quinn NP, McAuley J, Rothwell JC. Strength in Parkinson’s disease: relationship to rate of force generation and clinical status. Annals of Neurology. 1996;39:79–88. doi: 10.1002/ana.410390112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dick JPR, Rothwell JC, Day BL, Cantello R, Buruma O, Gioux M, Benecke R, Berardelli A, Thompson PD, Marsden CD. The bereitschafts potential is abnormal in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 1989;112:233–244. doi: 10.1093/brain/112.1.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diederich NJ, Moore CG, Leurgans SE, Chmura TA, Goetz CG. Parkinson disease with old-age onset - A comparative study with subjects with middle-age onset. Archives of Neurology. 2003;60:529–533. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.4.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Espay A, Beaton DE, Morgante F, Gunraj CA, Lang AE, Chen R. Impairments of speed and amplitude of movement in Parkinson’s disease: a pilot study. Movement Disorders. 2009;24:1001–1008. doi: 10.1002/mds.22480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grasso M, Mazzini L, Schieppati M. Muscle relaxation in Parkinson’s disease: a reaction time study. Movement Disorders. 1996;11:411–420. doi: 10.1002/mds.870110410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haslinger B, Erhard P, Kampfe N, Boecker H, Rummeny E, Schwaiger M, Conrad B, Ceballos-Baumann AO. Event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging in Parkinson’s disease before and after levodopa. Brain. 2001;124:558–570. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.3.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Homann C, Quehenberger F, Petrovic K. Influence of age, gender, education and dexterity on upper limb motor performance in Parkinsonian patients and healthy controls. Journal of Neural Transmission. 2003;110:885–897. doi: 10.1007/s00702-003-0009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jenkins IH, Fernandez W, Playford ED, Lees AJ, Frackowiak RSJ, Passingham RE, Brooks DJ. Impaired activation of the supplementary motor area in Parkinson’s disease is reversed when akinesia is treated with apomorphine. Annals of Neurology. 1992;32:749–757. doi: 10.1002/ana.410320608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jordan N, Sagar HJ, Cooper JA. A component analysis of the generation and release of isometric force in Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 1992;55:572–576. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.55.7.572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kunesh E, Schnitzler A, Tyercha C, Knecht S, Stelmach G. Altered force release control in Parkinson’s disease. Behavioral Brain Research. 1995;67:43–49. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(94)00111-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lou J, Kearns G, Benice T, Oken B, Sexton G, Nutt J. Levodopa improves physical fatigue in Parkinson’s disease: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Movement Disorders. 2003;18:1108–1114. doi: 10.1002/mds.10505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luders H. The supplementary sensorimotor area. An overview. Adv Neurol. 1996;70:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maier M, Bennett KM, Hepp-Reymond MC, Lemon RN. Contribution of the monkey cortico motor neuron system to the control of force in precision grip. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1993;69:772–785. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.69.3.772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mayville JM, Bressler S, Fuchs A, Kelso JAS. Spatiotemporal reorginization of electrical activity in the human brain associated with a timing transition in rhythmic auditory-motor coordination. Experimental Brain Research. 1999;127:371–381. doi: 10.1007/s002210050805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mayville JM, Fuchs A, Ding M, Cheyne D, Deecke L, Kelso JAS. Event-related changes in neuromagnetic activity association with syncopation and synchronization timing tasks. Human Brain Mapping. 2001;14:65–80. doi: 10.1002/hbm.1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakamura R, Nagasaki H, Narabayashi H. Disturbances of rhythm formation in patients with Parkinson’s disease. 1. Characteristics of tapping response to periodic signals. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 1978;46:63–75. doi: 10.2466/pms.1978.46.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Boyle D, Freeman JS, Cody FW. The accuracy and precision of timing or self-paced, repetitive movements in subjects with Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 1996;119 doi: 10.1093/brain/119.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pastor MA, Jahanshahi M, Artieda J, Obeso JA. Performance of repetitive wrist movements in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 1992;115:875–891. doi: 10.1093/brain/115.3.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Penn RD, Kroin JS, Reinkensmeyer A, Corcos DM. Injection of GABA-agonist into globus palidus in patient with Parkinson’s disease. Lancet. 1998;351:340–341. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)78336-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robichaud JA, Pfann KD, Vaillancourt DE, Comella CL, Corcos DM. Force control and disease severity in Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders. 2005;20:441–450. doi: 10.1002/mds.20350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rocchi L, Chiari L, Horak FB. Effects of deep brain stimulation and levodopa on postural sway in Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 2002;73:267–274. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.73.3.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodrigues J, Mastaglia F, Thickbroom G. Rapid slowing of maximal finger movement rate: fatigue of central motor control? Experimental Brain Research. 2009;196:557–563. doi: 10.1007/s00221-009-1886-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salenius S, Avikainen S, Kaakkola S, Hari R, Brown P. Defective cortical drive to muscle in Parkinson’s disease and its improvement with levodopa. Brain. 2002;125:491–500. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwab RS, England AC, Peterson E. Akinesia in Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 1959;9:65–72. doi: 10.1212/wnl.9.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sosnoff J, Vaillancourt D, Larsson L, Newell K. Coherence of EMG activity and single motor unit discharge patterns in human rhythmical force production. Behavioral Brain Research. 2005;158:301–310. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stegemöller EL, Simuni T, MacKinnon CD. Timing and frequency barriers during repetitive finger movements in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders. 2009;24:1162–1169. doi: 10.1002/mds.22535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stelmach G, Teasdale N, Phillips J, Worringham CJ. Force production characteristics in Parkinson’s disease. Experimental Brain Research. 1989;76:165–172. doi: 10.1007/BF00253633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stelmach G, Worringham CJ. The preparation and production of isometric force in Parkinson’s disease. Neuropsychologia. 1988;26:93–103. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(88)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vaillancourt D, Mayka M, Thulborn K, Corcos D. Subthalamic mucleus and internal globus pallidus scale with the rate of change of force production in humans. Neuroimage. 2004;23:175–186. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ziv I, Avraham M, Michaelov Y, Djaldetti R, Dressler R, Zoldan J, Melamed E. Enhanced fatigue during motor performance in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 1998;51:1583–1586. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.6.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]