Abstract

Background

There is significant interest in new loci for the inherited condition hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) because the known disease genes encode proteins involved in vascular transforming growth factor (TGF)-β signalling pathways, and the disease phenotype appears to be unmasked or provoked by angiogenesis in man and animal models. In a previous study, we mapped a new locus for HHT (HHT3) to a 5.7 Mb region of chromosome 5. Some of the polymorphic markers used had been uninformative in key recombinant individuals, leaving two potentially excludable regions, one of which contained loci for attractive candidate genes encoding VE Cadherin-2, Sprouty4 and FGF1, proteins involved in angiogenesis.

Methods

Extended analyses in the interval-defining pedigree were performed using informative genomic sequence variants identified during candidate gene sequencing. These variants were amplified by polymerase chain reaction; sequenced on an ABI 3730xl, and analysed using FinchTV V1.4.0 software.

Results

Informative genomic sequence variants were used to construct haplotypes permitting more precise citing of recombination breakpoints. These reduced the uninformative centromeric region from 141.2-144 Mb to between 141.9-142.6 Mb, and the uninformative telomeric region from 145.2-146.9 Mb to between 146.1-146.4 Mb.

Conclusions

The HHT3 interval on chromosome 5 was reduced to 4.5 Mb excluding 30% of the coding genes in the original HHT3 interval. Strong candidates VE-cadherin-2 and Sprouty4 cannot be HHT3.

Background

Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β superfamily signalling is of fundamental importance to developmental and physiological regulation. In these pathways (reviewed in [1,2]), ligands such as TGF-βs, bone morphogenetic proteins (BMP)s, activins, nodals, growth/differentiation factors (GDF)s and inhibins bind to receptor complexes of paired type I and type II transmembrane receptor serine/threonine kinases. Activated type I receptors (ALKs 1-7) phosphorylate receptor-associated Smad proteins in complex-specific patterns [3-5]. There is increasing recognition of the role of alternative signalling pathways for particular ligands within designated cell types. In endothelial cells (ECs), signalling through the TGF-β type II receptor, TβRII, can be propagated not only through ALK-5 via SMAD2/3 as in other cell types, but also through ALK-1 via SMAD1/5/8, providing two mutually antagonistic pathways [6,7]. The transmembrane glycoprotein endoglin is an accessory TGF-β receptor, highly expressed on ECs, and is one factor modulating the balance between ALK-1 and ALK-5 pathways [8].

The inherited vascular condition hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) [9] is of significant relevance to TGF-β signalling because the genes for endoglin, ALK-1 and SMAD4 (a co-Smad and downstream effector of the TGF-β signalling pathway), are mutated in different HHT families [10-12]. HHT is transmitted as an autosomal dominant trait due to a single mutation in either ENG encoding endoglin (HHT type 1); ACVRL1 encoding ALK-1 (HHT type 2) or SMAD4 (HHT in association with juvenile polyposis). Perturbation of TGF-β signalling pathways is therefore implicated in HHT pathogenesis.

HHT serves not only as a vascular model of aberrant TGF-β superfamily signalling, but also as a model of aberrant angiogenesis [13,14]. The abnormal blood vessels develop only in selected vascular beds (telangiectasia particularly in mucocutaneous and gastrointestinal sites; arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) most commonly in pulmonary, hepatic and cerebral circulations) [9,15]. At each site, only a small proportion of vessels are abnormal. The context in which HHT mutations are deleterious, when allowing apparently normal endothelial function for most vessels, now appear to be angiogenic in origin. Early studies modelling HHT in transgenic animals provided evidence of aberrant angiogenesis. Heterozygous mice developed HHT-like features; Eng and Alk1 null mice died by E11.5 with normal vasculogenesis but abnormal angiogenesis [7,16-20]. The zebrafish violet beauregarde (vbg), an Alk1 mutant, was also homozygous embryonic lethal, with mutant embryos displaying dilated cranial vessels attributed to an increased number of endothelial cells [21]. More recent studies have demonstrated that an Alk1 deletion in adult mouse subdermal blood vessels resulted in AVM formation in wounded areas displaying angiogenesis [22]; that angiogenic stimuli promoted AVM formation in endothelial specific endoglin knockout mice, accompanied by an abnormal increase in EC proliferation [23] which was also observed in Eng-/- mouse embryonic ECs [8], and that Alk1 knockout mice had defective smooth muscle differentiation and recruitment and excessive angiogenesis [7]. These data from animal models have been accompanied by clinical reports that Bevacizumab, an antibody against vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-A, and thalidomide, appear to have efficacy in treating clinical manifestations of HHT in man [24,25].

A current model to explain these observations, discussed in more detail in [26], is based on the EC-mural cell axis defined by Sato and Rifkin [27]. In angiogenesis, HHT mutations (endoglin and ALK-1) appear to impair recruitment of mural cells to the angiogenic sprout [7,28] at least in part via reduced EC secretion of TGF-β1 [29,30] and/or reduced TGF-β1 induced responses [7,29] resulting in defective mural cell stabilisation of the nascent vessel and persistent, excessive, EC proliferation. Thalidomide, which induced vessel maturation in Eng+/- mice which normally suffer from excessive angiogenesis, appears to target mural cell recruitment, by increasing endothelial expression of PDGF-B at the endothelial tip cell, thus facilitating recruitment of pericytes that express PDGFR-b, associated with increasing pericyte proliferation [25].

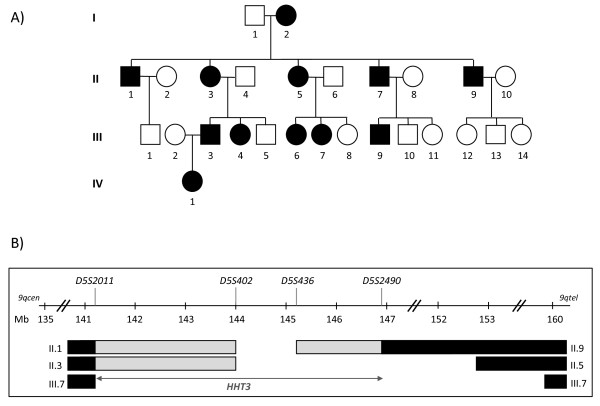

Further HHT genes were therefore predicted to identify new components or regulators of TGF-β/BMP signalling pathways of particular relevance to angiogenesis. More than 80% of HHT patients carry a sequence variation in endoglin or ALK-1 [31], most (but not all [32,33]) disease-causing, whilst 1-2% carry a mutation in SMAD4 [34]. HHT patients in whom no mutations have been detected in endoglin, ALK-1 or SMAD4 may have mutations in unsequenced intronic regions, or undetected large rearrangements of these genes, but importantly, they may have a mutation in a different gene. A third gene for pure HHT, HHT3, was mapped in our laboratory, using the pedigree illustrated in Figure 1A, to chromosome 5q [35] (Figure 1B), and a fourth, HHT4, to chromosome 7p [36].

Figure 1.

Previous HHT3 interval. A) HHT3 linked Family S pedigree (black symbols represent HHT-affected individuals; white symbols represent unaffected individuals; squares represent males and circles represent females. Individuals are denoted by their generation number, such that the oldest male is I.1, oldest female I.2). B) Published HHT3 interval on chromosome 5 between microsatellite markers D5S2011 and D5S2490 [35], identifying the region shared by all affected individuals (open interval between D5S402 and D5S436); regions where the designated individuals had inherited their affected parent's non disease-gene bearing allele (black bars), and regions in which the transition from the non disease-gene bearing allele (black bars) to disease-gene bearing allele (open interval) had occurred, but the exact sites of the meiotic recombination event was not definable using the markers studied in [35] (grey bars; uninformative markers). It was possible that the interval could be reduced to a minimum of D5S402-D5S436, according to where the recombination breakpoints had occurred in individuals II.1, II.3 and II.9. cen: centromere; tel: telomere; Mb: mega bases.

The published chromosome 5 HHT3 interval which contains the HHT3 gene, is 5.7 Mb long, between microsatellite markers D5S2011 and D5S2490 (Figure 1B) [35]. This interval contains 38 genes according to the Ensembl genome browser http://www.ensembl.org. There were two groups of potentially very attractive candidate genes. The first encode proteins involved in angiogenesis: PCDH12 and SPRY4 (discussed further below), and FGF1 encoding the proangiogenic fibroblast growth factor 1 [37]). A second group of interval genes encode proteins involved in signalling by serine/threonine kinases: PPP2R2B which encodes the B regulatory subunit of protein phosphatase 2A [38], and STK32A, encoding a serine/threonine kinase [39]. While these genes had been sequenced with no disease-causing mutations found ([35], Govani and Shovlin unpublished), this did not exclude the genes as disease-causing, due to the possibility of undetected intronic mutations. Importantly PCDH12 (141.3 Mb), SPRY4 (141.6 Mb) and FGF1 (142 Mb) were at the centromeric extreme of the HHT3 interval, and PPP2R2B (146.4 Mb) and STK32A (146.6 Mb) at the telomeric extreme, all within potentially excludable regions of the interval [35].

Excluding any of these genes from the HHT3 interval was important not only to assist the identification of HHT3 itself, but also to inform scientists working on the relevant proteins, particularly VE-Cadherin-2 (encoded by PCDH12) and Sprouty4 (encoded by SPRY4): VE-Cadherin-2, primarily expressed on ECs [40], was shown to be down-regulated in HHT1 and HHT2 blood outgrowth ECs [41] with a role in angiogenesis [42]. Furthermore, a close family member (VE-cadherin), associates with endoglin and ALK-1 in cell surface complexes, and promotes TGF-β1 signalling by facilitating the recruitment of TGF-β receptor II (TβRII) into the active signalling complex [43]. Sprouty family members are involved in branching morphogenesis [44]. Overexpression of Spry4 in ECs of embryonic day (E)9 mice inhibited angiogenesis [45], whereas surviving Spry4 knockout mice [46] demonstrated enhanced angiogenesis [47].

In this study we report the fine mapping of the published HHT3 interval using genomic sequence variants detected during candidate gene sequencing, and exclusion of key genes.

Methods

Pedigree

Ethics approval was obtained from the Multicentre Research Ethics Committee for Scotland (MREC/98/0/42; 07/MRE00/19), by the Hammersmith, Queen Charlotte's, Chelsea, and Acton Hospital Research Ethics Committee (LREC 99/5637M) and in 2007 by the Hammersmith Hospitals Trust (SHOV1022, 2007). The study is registered on http://www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT00230620). The pedigree (Family S, Figure 1A) and DNA extractions were as described in [35].

PCR and sequencing

Oligonucleotide primers were ordered from Eurofins MWG-Biotech and amplified in informative members of Family S by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Genomic primers spanning exons and > 30 bp of flanking intronic sequences were amplified by PCR using Phusion Hotstart (New England Biolabs) or AmpliTaq Gold (Applied Biosystems) DNA polymerases. Reactions were performed as recommended by the manufacturers using 35-40 cycles of denaturation, annealing (at primer specific Ta) and extension. PCR products were treated with an ExoSAP mix containing SAP enzyme and buffer (Promega) and ExoI enzyme (New England Biolabs) as previously described [48]; gel purified with Wizard SV gel and PCR clean-up system (Promega) following the manufacturer's protocol; or gel purified and ethanol precipitated using Costar Spin-X column centrifuge tubes [49] followed by ethanol precipitation [50]. Purified PCR products were sequenced in 10 μl reactions with 25 ng (≅ 3.2 pM) of the sequencing primer on an ABI 3730xl DNA analyzer (MRC CSC DNA core laboratory, Imperial College London, Hammersmith). The results were analysed using FinchTV V1.4.0 software (Geospiza, Inc).

Fine mapping

Non-disease causing genomic sequence variants found during HHT3 candidate gene sequencing were used to fine map the interval, by providing further polymorphisms to track known recombination events through the uninformative part of the interval. Previously studied microsatellite polymorphisms had not been able to distinguish between disease and non-disease alleles (Figure 1B; grey bars), predominantly due to homozygosity in individual I.2 (Figure 1A). New sequence variants where individual I.2 was heterozygous (Figure 2) were sequenced in the interval-defining members of the pedigree (Figure 3). Adjacent genes (such as NR3C1, mutations in which cause glucocorticoid resistance [51]), were also sequenced to identify further polymorphisms to define the precise centromeric recombination event. The alleles inherited by each pedigree member were then assessed and assigned to maternal or paternal origin using Mendelian principles. Haplotypes were then constructed to minimise the number of recombination events that would be required to generate the segments of DNA in each offspring. NCBI dbSNP http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP/ and SNPbrowser™ V3.5 (Applied Biosystems) were used to determine if the genomic sequence variants were previously known (when they were allocated the relevant rs dbSNP RefSNP label), or novel.

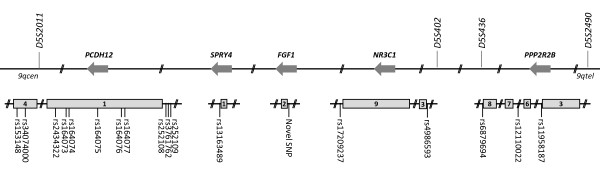

Figure 2.

Informative genomic sequence variants used in fine mapping. Locations of genomic variants where individual I.2 was heterozygous, potentially allowing her disease associated and non-disease associated alleles to be tracked. Sequence variants are illustrated in relation to candidate gene exons (grey boxes) and original microsatellite markers. By chance, all five genes are on the reverse strand of chromosome 5, designated by reverse arrows. rs; as on NCBI dbSNP.

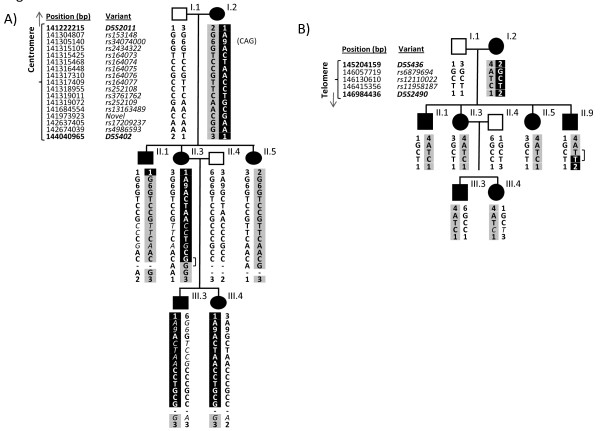

Figure 3.

Genomic variant haplotypes in interval-defining members of the pedigree. A) Allele inheritance and haplotypes for the inheritance of the key microsatellite markers, and new genomic sequence variants, across PCDH12, SPRY4, FGF1 and NR3C1 genes in eight members of Family S. For each sequence variant, offspring inherit one allele from their mother and one from their father. Occasional alleles where it was not possible to determine parental origin (and which were therefore not used for haplotype construction) are denoted in non-bold italics. Individual II.5 demonstrates the disease haplotype across the interval, a haplotype which is now shared by II.1, but not II.3 and her descendants until rs17209237 in NR3C1. Therefore II.3 excludes the centromeric region between rs153148 and the novel SNP in FGF1. B) Haplotypes for the inheritance of the new genomic sequence variants across the PPP2R2B gene in nine members of Family S. Affected individuals II.1, II.3, II.5, III.3 and III.4 demonstrate the disease haplotype which is not shared by II.9 at rs 11958187, but is shared at rs12110022, rs 6879694, and the remainder of the HHT3 interval. Therefore II.9 excludes rs11958187 and beyond from the telomeric extreme of the interval.]: uninformative regions; bp: base pairs.

For confirmations of genotypes, SNPs rs153148, rs34074000, rs164075, rs164077, rs6879694, rs12110022 and rs11958187 were sequenced in two separate PCR reactions in two or more key individuals.

Genome analysis

Chromosome 5 positions of genomic sequence variants are based on NCBI Reference build 36 (hg18) assembly.

Results

The HHT3 interval [35] was defined by recombination events in three affected individuals of Family S, II.1, II.3, and II.9 (Figure 1). At each end of the interval, there were regions illustrated by grey bars, in which it was not possible to state which maternal chromosome 5 allele sequences these individuals had inherited, due to homozygosity in individual I.2. New non-microsatellite genomic sequence variants were identified during candidate gene sequencing and analysed to assess if they could be used to track the inheritance of the sequences derived from the two different alleles of chromosome 5 from individual I.2 in the regions between D5S2011 and D5S402, and between D5S436 and D5S2490. A total of 89 genetic sequence variations were found (75 SNPs, 4 indels and 10 repeats) of which 73 were present on dbSNP (2010, build 131). Eighteen potentially informative genomic sequence variants where I.2 was a heterozygote (seventeen SNPs; one triplet repeat) were identified within the regions of interest (Figure 2).

Figure 3 tracks the inheritance of alleles at these SNPs and triplet repeat in the centromeric (Figure 3A), and telomeric (Figure 3B) extremes of the interval. Although I.2 shared three genotypes with I.1, it was possible to definitely state which of I.2's alleles had been inherited by each of their children at all sites except rs164077, rs252108 and rs252109 where genotypes were shared. Sites where the inheritance of the affected parent's alleles could definitely be determined were used to generate haplotypes.

As shown in Figure 3A, sequencing 15 of these markers allowed better definition of the centromeric regions where II.1 and II.3 had inherited the disease-gene associated allele, and indicated that the site of the recombination breakpoint differed in the two individuals. In individual II.1, the breakpoint had occurred close to D5S2011 such that he had inherited the maternal disease allele from rs153148 (within PCDH12) at 141.3 Mb and onwards. However, in individual II.3, the recombination event had occurred further into the HHT3 interval: II.3 continued to inherit a different maternal allele to her affected siblings from rs153148 to a novel SNP (within FGF1) at 141.9 Mb. By 142.6 Mb (rs17209237 and rs4986593 within NR3C1), II:3 had inherited the same maternal allele as her affected siblings, siting the recombination event between 141.9 Mb and 142.6 Mb (novel SNP and rs17209237)

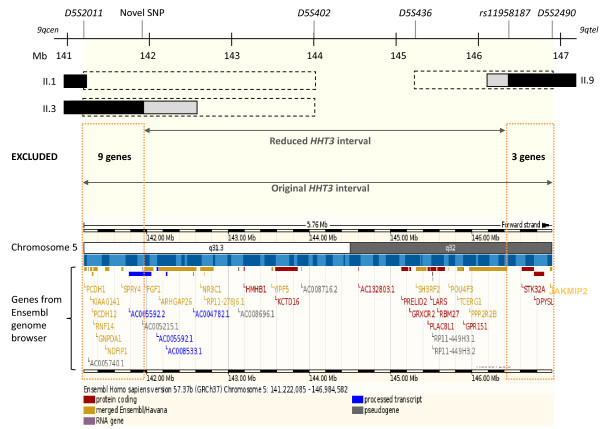

These data in individual II.3 indicated that in addition to the definite D5S402-D5S436 region (Figure 1B), the maximal centromeric extent of the disease gene-bearing chromosome 5 that could have been inherited by all affected individuals in the pedigree extended not from D5S2011 at 141.2 Mb, but from the FGF SNP at 141.9 Mb (Figure 4). This reduction of the uninformative centromeric region by 0.7 Mb excluded 9 Ensembl interval genes (Figure 4). PCDH12 and SPRY4 were amongst the group of genes excluded (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The refined HHT3 interval. The original HHT3 interval was between microsatellite markers D5S2011 and D5S2490, and uninformative between D5S2011-D5S402 and D5S2490-D5S436 (black dotted bars) in key individuals II.1, II.3 and II.9 [35]. Informative genomic variations used in fine mapping reduced the extent of the uninformative regions (grey bars, see Figure 1B). The refined HHT3 interval is sited between a novel SNP within FGF1 intron 1, and rs11958187 within PPP2R2B intron 4. Black bars indicate the definite recombination events that defined the interval in the denoted individuals. Fine mapping, by reducing the interval, excluded 12 interval genes as shown in the lower Ensembl genome browser image of candidate genes (genes no longer in the interval are denoted by orange dotted boxes; Mb: mega bases).

The telomeric border of the HHT3 interval was defined by a recombination event in affected individual II.9. This individual had inherited a non-disease allele at microsatellite markers up to and including D5S2490 (146.9 Mb), and was uninformative at microsatellite markers up to D5S436 (145.2 Mb) [35] (Figure 1B). Figure 3B demonstrates the results of sequencing genomic sequence variants within genes in the potentially excludable telomeric extreme of the interval. II.9 had inherited the maternal disease allele from rs6879694 to rs12110022, but a different maternal allele to his affected siblings at rs11958187 (within PPP2R2B). This sited the recombination event between 146.1-146.4 Mb, excluding a further 3 Ensembl interval genes; JAKMIP2, DPYSL, and STK32A (Figure 4).

Discussion

Identification of further HHT genes is predicted to provide new insights into TGF-β/BMP signalling and angiogenesis pathways. The previously published HHT3 interval included several highly attractive candidate genes. As further evidence accumulated regarding the roles of particularly VE-cadherin and Sprouty family members, the possibility that one of these may be mutated in HHT increased their interest to endothelial cell biologists. While these genes had been sequenced with no disease-causing mutations found in the coding or untranslated regions in affected members of the chromosome 5 linked family ([35], Govani and Shovlin unpublished), such sequencing did not exclude the genes as disease-causing, due to the possibility of undetected mutations in intronic or poorly characterised regulatory regions.

It was recognised that fine mapping of the genomic variants found during candidate gene sequencing could help define the critical recombination events and exclude certain genes, including those for VE-cadherin-2 and Sprouty4. Hence candidate gene sequence variants were examined in the interval-defining members of the Family S pedigree that included the crucial individuals whose recombination events had defined the centromeric and telomeric borders of the HHT3 interval.

To optimise PCR fidelity, candidate genes and genomic sequence variants were amplified with AmpliTaq Gold or Phusion Hotstart DNA polymerases, enzymes that are inactive until they undergo heat activation to generate polymerase activity, thus providing an automated 'hot start' [52-54]. To further confirm key genotypes, SNPs rs153148, rs34074000, rs164075, rs164077, rs6879694, rs12110022 and rs11958187 were sequenced in two separate PCR reactions in two or more key individuals.

Confirmed genotypes allowed construction of haplotypes across the centromeric and telomeric extremes of the HHT3 interval. The recombination events were then sited more precisely, leading to findings which excluded 12 interval genes such as strong candidates PCDH12, SPRY4 and STK32A. FGF1 and PPP2R2B could not be fully excluded as the centromeric and telomeric defining recombination events (SNPs 'novel' and rs11958187) are within the introns of both genes. It should be noted that the siting of a recombination breakpoint in a single affected member of the pedigree does not carry any pathogenic implications for the genes in question, unlike disease-causing chromosomal rearrangements when the causative rearrangement is shared by all of the affected individuals in the pedigree.

The original interval contained 38 genes according to the Ensembl genome browser. Twelve have been excluded in this study. The 26 genes that remain include 10 pseudogenes or processed transcripts with no known protein products; two genes of potential functional relevance to angiogenesis or TGF-β signalling (FGF1 and PPP2R2B); three protein coding genes associated with other genetic disease (ARHGAP26; NR3C1 and POU4F3) and 11 protein coding genes not associated with a genetic disease but whose gene product had no obvious function in TGF-β signalling and/or angiogenesis (HMHB1; YIPF5; KCTD16; PRELID2; LARS; TCERG1; SH3RF2; GRXCR2; RBM27; PLAC8L1 and GPR151).

Conclusions

Further examination of key recombination events in a known HHT3 pedigree has reduced the published HHT3 gene interval. Crucially, the PCDH12 and SPRY4 genes were amongst twelve genes no longer in the reduced interval. Therefore VE-cadherin-2 and Sprouty4, proteins of significant interest to angiogenesis researchers due to their respective roles in pathophysiological angiogenesis and relationship to known interactors with the HHT gene products, are not mutated in HHT3 [55]. Reduction of the interval has facilitated HHT3 gene identification studies.

Abbreviations

HHT: hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia; TGF-β: transforming growth factor-beta; ALK: activin receptor-like kinase; AVMS: arteriovenous malformations; SNP: single nucleotide polymorphism; PCR: polymerase chain reaction; ECS: endothelial cells.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

CLS and FSG designed the study. All experimental work was performed by FSG, with advice from CLS. The manuscript was co-written by CLS and FSG; both authors approved the final version.

Contributor Information

Fatima S Govani, Email: fatima.govani05@imperial.ac.uk.

Claire L Shovlin, Email: c.shovlin@imperial.ac.uk.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the British Heart Foundation. We are also grateful for support from the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre Funding Scheme. The study sponsors played no part in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication. The authors thank Dr Gillian Wallace and Dr Stewart Cole for DNA extractions; Dr Mick Jones and Dr Carol Shoulders for helpful discussions; and the family for their willing participation in these studies.

References

- Massague J, Gomis RR. The logic of TGFbeta signaling. FEBS Lett. 2006;580(12):2811–2820. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piek E, Heldin CH, Ten Dijke P. Specificity, diversity, and regulation in TGF-beta superfamily signaling. FASEB J. 1999;13(15):2105–2124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly AC, Randall RA, Hill CS. Transforming growth factor beta-induced Smad1/5 phosphorylation in epithelial cells is mediated by novel receptor complexes and is essential for anchorage-independent growth. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28(22):6889–6902. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01192-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SO, Lee YJ, Seki T, Hong KH, Fliess N, Jiang Z, Park A, Wu X, Kaartinen V, Roman BL, Oh SP. ALK5- and TGFBR2-independent role of ALK1 in the pathogenesis of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia type 2. Blood. 2008;111(2):633–642. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-107359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upton PD, Davies RJ, Trembath RC, Morrell NW. Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) and activin type II receptors balance BMP9 signals mediated by activin receptor-like kinase-1 in human pulmonary artery endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(23):15794–15804. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.002881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goumans MJ, Valdimarsdottir G, Itoh S, Lebrin F, Larsson J, Mummery C, Karlsson S, ten Dijke P. Activin receptor-like kinase (ALK)1 is an antagonistic mediator of lateral TGFbeta/ALK5 signaling. Mol Cell. 2003;12(4):817–828. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00386-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh SP, Seki T, Goss KA, Imamura T, Yi Y, Donahoe PK, Li L, Miyazono K, ten Dijke P, Kim S, Li E. Activin receptor-like kinase 1 modulates transforming growth factor-beta 1 signaling in the regulation of angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(6):2626–2631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.6.2626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pece-Barbara N, Vera S, Kathirkamathamby K, Liebner S, Di Guglielmo GM, Dejana E, Wrana JL, Letarte M. Endoglin null endothelial cells proliferate faster and are more responsive to transforming growth factor beta1 with higher affinity receptors and an activated Alk1 pathway. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(30):27800–27808. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503471200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govani FS, Shovlin CL. Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia: a clinical and scientific review. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009;17(7):860–871. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2009.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllister KA, Grogg KM, Johnson DW, Gallione CJ, Baldwin MA, Jackson CE, Helmbold EA, Markel DS, McKinnon WC, Murrell J, McCormick MK, Pericak-Vance MA, Heutink P, Oostra BA, Haitjema T, Westermann CJJ, Porteous ME, Guttmacher AE, Letarte M, Marchuk DA. Endoglin, a TGF-beta binding protein of endothelial cells, is the gene for hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia type 1. Nat Genet. 1994;8(4):345–351. doi: 10.1038/ng1294-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DW, Berg JN, Baldwin MA, Gallione CJ, Marondel I, Yoon SJ, Stenzel TT, Speer M, Pericak-Vance MA, Diamond A, Guttmacher AE, Jackson CE, Attisano L, Kucherlapati R, Porteous ME, Marchuk DA. Mutations in the activin receptor-like kinase 1 gene in hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia type 2. Nat Genet. 1996;13(2):189–195. doi: 10.1038/ng0696-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallione CJ, Repetto GM, Legius E, Rustgi AK, Schelley SL, Tejpar S, Mitchell G, Drouin É, Westermann CJJ, Marchuk DA. A combined syndrome of juvenile polyposis and hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia associated with mutations in MADH4 (SMAD4) The Lancet. 2004;363(9412):852–859. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15732-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ten Dijke P, Goumans MJ, Pardali E. Endoglin in angiogenesis and vascular diseases. Angiogenesis. 2008;11(1):79–89. doi: 10.1007/s10456-008-9101-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David L, Feige JJ, Bailly S. Emerging role of bone morphogenetic proteins in angiogenesis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2009;20(3):203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shovlin CL, Guttmacher AE, Buscarini E, Faughnan ME, Hyland RH, Westermann CJJ, Kjeldsen AD, Plauchu H. Diagnostic Criteria for Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia (Rendu-Osler-Weber Syndrome) American Journal of Medical Genetics. 2000;91(1):66–67. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(20000306)91:1<66::AID-AJMG12>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdeau A, Dumont DJ, Letarte M. A murine model of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. J Clin Invest. 1999;104(10):1343–1351. doi: 10.1172/JCI8088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li DY, Sorensen LK, Brooke BS, Urness LD, Davis EC, Taylor DG, Boak BB, Wendel DP. Defective angiogenesis in mice lacking endoglin. Science. 1999;284(5419):1534–1537. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5419.1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthur HM, Ure J, Smith AJ, Renforth G, Wilson DI, Torsney E, Charlton R, Parums DV, Jowett T, Marchuk DA, Burn J, Diamond AG. Endoglin, an ancillary TGFbeta receptor, is required for extraembryonic angiogenesis and plays a key role in heart development. Dev Biol. 2000;217(1):42–53. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urness LD, Sorensen LK, Li DY. Arteriovenous malformations in mice lacking activin receptor-like kinase-1. Nat Genet. 2000;26(3):328–331. doi: 10.1038/81634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan S, Hanes MA, Dickens T, Porteous ME, Oh SP, Hale LP, Marchuk DA. A mouse model for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) type 2. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12(5):473–482. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman BL, Pham VN, Lawson ND, Kulik M, Childs S, Lekven AC, Garrity DM, Moon RT, Fishman MC, Lechleider RJ, Weinstein BM. Disruption of acvrl1 increases endothelial cell number in zebrafish cranial vessels. Development. 2002;129(12):3009–3019. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.12.3009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SO, Wankhede M, Lee YJ, Choi EJ, Fliess N, Choe SW, Oh SH, Walter G, Raizada MK, Sorg BS, Oh SP. Real-time imaging of de novo arteriovenous malformation in a mouse model of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(11):3487–3496. doi: 10.1172/JCI39482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud M, Allinson KR, Zhai Z, Oakenfull R, Ghandi P, Adams RH, Fruttiger M, Arthur HM. Pathogenesis of arteriovenous malformations in the absence of endoglin. Circ Res. 2010;106(8):1425–1433. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.211037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell A, Adams LA, MacQuillan G, Tibballs J, vanden Driesen R, Delriviere L. Bevacizumab reverses need for liver transplantation in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Liver Transpl. 2008;14(2):210–213. doi: 10.1002/lt.21417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebrin F, Srun S, Raymond K, Martin S, van den Brink S, Freitas C, Breant C, Mathivet T, Larrivee B, Thomas JL, Arthur HM, Westermann CJ, Disch F, Mager JJ, Snijder RJ, Eichmann A, Mummery CL. Thalidomide stimulates vessel maturation and reduces epistaxis in individuals with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Nat Med. 2010;16(4):420–428. doi: 10.1038/nm.2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shovlin CL. Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia: Pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. Blood Reviews. 2010. in press . [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sato Y, Rifkin DB. Inhibition of endothelial cell movement by pericytes and smooth muscle cells: activation of a latent transforming growth factor-beta 1-like molecule by plasmin during co-culture. J Cell Biol. 1989;109(1):309–315. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.1.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancini ML, Terzic A, Conley BA, Oxburgh LH, Nicola T, Vary CP. Endoglin plays distinct roles in vascular smooth muscle cell recruitment and regulation of arteriovenous identity during angiogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2009;238(10):2479–2493. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho RL, Itoh F, Goumans MJ, Lebrin F, Kato M, Takahashi S, Ema M, Itoh S, van Rooijen M, Bertolino P, Ten Dijke P, Mummery CL. Compensatory signalling induced in the yolk sac vasculature by deletion of TGFbeta receptors in mice. J Cell Sci. 2007;120(Pt 24):4269–4277. doi: 10.1242/jcs.013169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letarte M, McDonald ML, Li C, Kathirkamathamby K, Vera S, Pece-Barbara N, Kumar S. Reduced endothelial secretion and plasma levels of transforming growth factor-beta1 in patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia type 1. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;68(1):155–164. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards-Yutz J, Grant K, Chao EC, Walther SE, Ganguly A. Update on molecular diagnosis of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Hum Genet. 2010;128(1):61–77. doi: 10.1007/s00439-010-0825-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayrak-Toydemir P, McDonald J, Mao R, Phansalkar A, Gedge F, Robles J, Goldgar D, Lyon E. Likelihood ratios to assess genetic evidence for clinical significance of uncertain variants: hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia as a model. Exp Mol Pathol. 2008;85(1):45–49. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald J, Gedge F, Burdette A, Carlisle J, Bukjiok CJ, Fox M, Bayrak-Toydemir P. Multiple sequence variants in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia cases: illustration of complexity in molecular diagnostic interpretation. J Mol Diagn. 2009;11(6):569–575. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2009.080148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallione C, Aylsworth AS, Beis J, Berk T, Bernhardt B, Clark RD, Clericuzio C, Danesino C, Drautz J, Fahl J, Fan Z, Faughnan ME, Ganguly A, Garvie J, Henderson K, Kini U, Leedom T, Ludman M, Lux A, Maisenbacher M, Mazzucco S, Olivieri C, Ploos van Amstel JK, Prigoda-Lee N, Pyeritz RE, Reardon W, Vandezande K, Waldman JD, White RI, Williams CA, Marchuk DA. Overlapping spectra of SMAD4 mutations in juvenile polyposis (JP) and JP-HHT syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A(2):333–339. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole SG, Begbie ME, Wallace GMF, Shovlin CL. A new locus for hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT3) maps to chromosome 5. Journal of Medical Genetics. 2005;42:577–582. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.028712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayrak-Toydemir P, McDonald J, Akarsu N, Toydemir RM, Calderon F, Tuncali T, Tang W, Miller F, Mao R. A fourth locus for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia maps to chromosome 7. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140(20):2155–2162. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayrabedyan S, Kyurkchiev S, Kehayov I. FGF-1 and S100A13 possibly contribute to angiogenesis in endometriosis. J Reprod Immunol. 2005;67(1-2):87–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer RE, Hendrix P, Cron P, Matthies R, Stone SR, Goris J, Merlevede W, Hofsteenge J, Hemmings BA. Structure of the 55-kDa regulatory subunit of protein phosphatase 2A: evidence for a neuronal-specific isoform. Biochemistry. 1991;30(15):3589–3597. doi: 10.1021/bi00229a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning G, Whyte DB, Martinez R, Hunter T, Sudarsanam S. The protein kinase complement of the human genome. Science. 2002;298(5600):1912–1934. doi: 10.1126/science.1075762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig D, Lorenz J, Dejana E, Bohlen P, Hicklin DJ, Witte L, Pytowski B. cDNA cloning, chromosomal mapping, and expression analysis of human VE-Cadherin-2. Mamm Genome. 2000;11(11):1030–1033. doi: 10.1007/s003350010186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez LA, Garrido-Martin EM, Sanz-Rodriguez F, Pericacho M, Rodriguez-Barbero A, Eleno N, Lopez-Novoa JM, Duwell A, Vega MA, Bernabeu C, Botella LM. Gene expression fingerprinting for human hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16(13):1515–1533. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallez Y, Vilgrain I, Huber P. Angiogenesis: the VE-cadherin switch. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2006;16(2):55–59. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudini N, Felici A, Giampietro C, Lampugnani M, Corada M, Swirsding K, Garre M, Liebner S, Letarte M, ten Dijke P, Dejana E. VE-cadherin is a critical endothelial regulator of TGF-beta signalling. Embo J. 2008;27(7):993–1004. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrita MA, Christofori G. Sprouty proteins: antagonists of endothelial cell signaling and more. Thromb Haemost. 2003;90(4):586–590. doi: 10.1160/TH03-04-0217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SH, Schloss DJ, Jarvis L, Krasnow MA, Swain JL. Inhibition of angiogenesis by a mouse sprouty protein. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(6):4128–4133. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006922200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi K, Ayada T, Ichiyama K, Kohno R, Yonemitsu Y, Minami Y, Kikuchi A, Maehara Y, Yoshimura A. Sprouty2 and Sprouty4 are essential for embryonic morphogenesis and regulation of FGF signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;352(4):896–902. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.11.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi K, Ishizaki T, Ayada T, Sugiyama Y, Wakabayashi Y, Sekiya T, Nakagawa R, Yoshimura A. Sprouty4 deficiency potentiates Ras-independent angiogenic signals and tumor growth. Cancer Sci. 2009;100(9):1648–1654. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01214.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JB, Blackshaw S. One-step enzymatic purification of PCR products for direct sequencing. Curr Protoc Hum Genet. 2001;Chapter 11 doi: 10.1002/0471142905.hg1106s30. Unit 11 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz H, Whitton JL. A rapid, inexpensive method for eluting DNA from agarose or acrylamide gel slices without using toxic or chaotropic materials. Biotechniques. 1992;13(2):205–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore D. Purification and concentration of DNA from aqueous solutions. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2001;Chapter 10 doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im1001s8. Unit 10 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray PJ, Cotton RG. Variations of the human glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1): pathological and in vitro mutations and polymorphisms. Hum Mutat. 2003;21(6):557–568. doi: 10.1002/humu.10213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moretti T, Koons B, Budowle B. Enhancement of PCR amplification yield and specificity using AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase. Biotechniques. 1998;25(4):716–722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phusion™ Hot Start High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (manual) http://www.neb.com/nebecomm/ManualFiles/manualF-540.pdf

- Chou Q, Russell M, Birch DE, Raymond J, Bloch W. Prevention of pre-PCR mis-priming and primer dimerization improves low-copy-number amplifications. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20(7):1717–1723. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.7.1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govani FS. PhD thesis. Imperial College London, NHLI Cardiovascular Sciences department; 2009. Regulation of endothelial cell gene expression: insights from HHT3 candidate gene studies. [Google Scholar]