Abstract

The regioselective Stille cross-coupling reactions of 3-tri-n-butylstannyl-1-trimethylsilyl-1-propyne demonstrate isomerization following the initial transmetalation step resulting in allenyl palladium intermediates for reductive coupling to yield conjugated 1,1-disubstituted allenylsilanes.

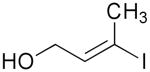

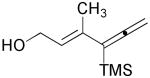

Recent studies in our laboratories have examined the development of bifunctionalized reagents which provide for sequential execution of SE′ reactions and cross-coupling processes. Conceptually, the linkage of stereocontrolled allylations for asymmetric induction in tandem with the versatility of cross-coupling reactions provides a powerful strategy for the rapid assembly of molecular complexity. In this fashion, we have described the use of bis-tri-n-butylstannyl reagents for an initial asymmetric SE′ reaction resulting in the production of an alkenylstannane for subsequent Stille reactions.1 We have also recently explored the SE′ chemistry of 3,3-bis(trimethyl)-2-methyl-1-propene and related alkenes for the stereocontrolled formation of the 3,4-anti-(E)-1-trimethylsilyl-3-methyl-4-penten-4-ol motif as a convenient precursor to the corresponding (E)-alkenyl iodides to advance cross-coupling processes.2

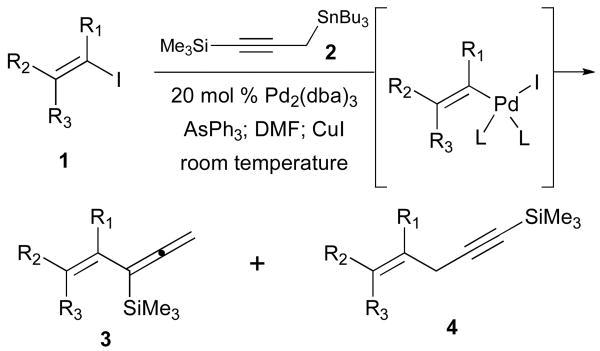

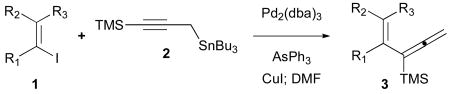

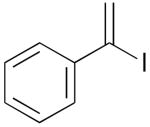

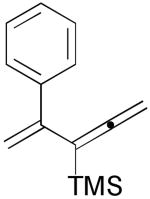

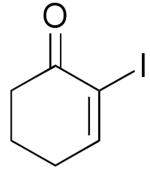

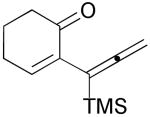

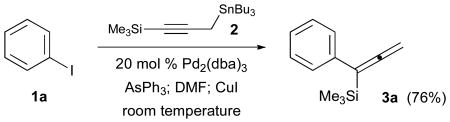

In this communication, recent studies of Stille cross-coupling reactions of alkenyl iodides 1 with bifunctional-3-tri-n-butylstannyl-1-trimethylsilyl-1-propyne (2) are described. In this process, two outcomes may be realized since allylic bond formation with respect to the propargylic stannane 2 could deliver the TMS-allene 3 via sp2–sp2 coupling whereas a direct replacement of tin in the usual fashion features the sp2–sp3 cross-coupling leading to the nonconjugated enyne 4. Our plans sought the production of the trimethylsilyl allene 3 to be employed in subsequent Sakuari SE′ reactions as a strategy toward the selective preparation of (E)- and (Z)-conjugated enynes. Rationale for the formation of 3 is based on literature precedents which have recognized the interconversions of η1-propargyl and η1-allenylpalladium complexes as well as η3-propargylpalladium(II) species.3,4 However, these studies have generally utilized propargyl chlorides and bromides for initial insertion reactions with palladium catalysts followed by transmetalations of organostannanes leading primarily to nonconjugated enyne products 4. The specific example of the Stille cross-coupling of 3-trimethylsilylpropargyl bromide with an alkenylstannane demonstrates regioselective production of the skipped enyne.5

In fact, Ma and Zhang6 have reported analogous Negishi couplings of allenic/propargylic zinc species with aryl and alkenyl iodides resulting in major adducts corresponding to enynes 4, and related studies by Jamison7 have described similar results for cross-coupling reactions of alkenyl iodides with propargyl copper intermediates. In these studies, transmetalations of propargyllithium reagents are assumed to provide access to an equilibration of allenic and propargylic copper and zinc species, respectively. On the other hand, site-selective Stille reactions of tri-n-butylallenylstannanes have afforded an effective route to substituted allenes.8 Alternatively, Nakamura and coworkers have recently reported palladium-catalyzed hydrogen-transfer reactions of N,N-dialkyl propargyl amines for the synthesis of allenes.9

Our initial cross-coupling experiments of iodobenzene (1a) with 3-tri-n-butylstannyl-1-trimethylsilyl-1-propyne (2) cleanly produced the allenylsilane 3a in 76% isolated yield.10 The observation of an allylic transposition which affords selective coupling to give 3a is unprecedented based on the results of the prior art. Further efforts have examined the generality of this reaction, and our results are compiled in Table 1.

Table 1.

Allenylsilanes via Pd-catalyzed Stille Reactions

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Iodide | Producta | Yieldb | ||

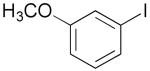

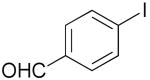

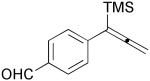

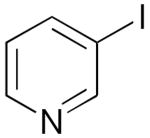

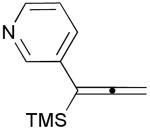

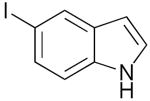

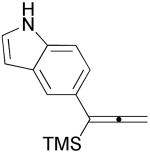

| 1 | 1b |  |

3b |  |

82% |

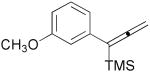

| 2 | 1c |  |

3c |  |

61% |

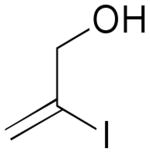

| 3c | 1d |  |

3d |  |

46% |

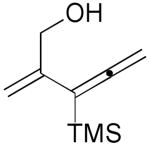

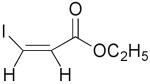

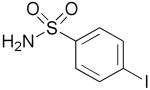

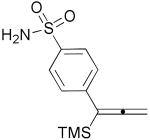

| 4 | 1e |  |

3e |  |

64% |

| 5 | 1f |  |

3f |  |

51% |

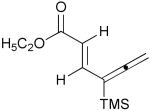

| 6 | 1g |  |

3g |  |

50% |

| 7 | 1h |  |

3h |  |

77% |

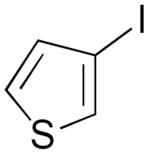

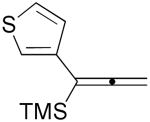

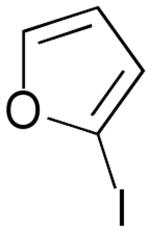

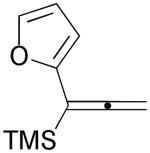

| 8 | 1i |  |

3i |  |

65% |

| 9 | 1j |  |

3j |  |

62% |

| 10 | 1k |  |

3k |  |

72% |

| 11 | 1l |  |

3l |  |

54% |

| 12 | 1m |  |

3m |  |

71% |

Reaction Conditions: Starting iodides 1 (1.0 eq) were combined with propargyl stannane 2 (1.3 eq) and AsPh3 (0.8 eq) followed by addition of Pd2(dba)3 (20 mol %) and CuI (0.8 eq). Stirring under N2 at 22 °C for 8–15 h led to the complete consumption of 1. For entry 1, iodide 1b was reacted at 45 °C, and for entry 11, iodide 1l was reacted at 70 °C. For entry 2, we have found that tri-(2-furyl)phosphine (0.8 eq) is effectively used in place of AsPh3.

Yields are given for purified products isolated via flash silica gel chromatography.

Iodide 1d is somewhat unstable and slowly leads to decomposition at room temperature.

A convenient preparation of the starting stannane 2 utilized 1-trimethylsilyl-1-propyne for deprotonation at −78 °C in THF solution with tert-butyllithium (1.7 M in Hexanes) followed by addition of tri-n-butylstannyl chloride. Nearly quantitative yields of 2 were isolated after flash silica gel chromatography using pentane. Alkyne 2 was stored in the freezer under N2 without evidence of decomposition or isomerization. Subsequent cross-coupling reactions of 2 have been optimized using Pd2(dba)3 in dry DMF containing triphenylarsine and purified cuprous iodide. Examples of alkenyl iodides, aryl iodides and heteroaromatic iodides (entries 1–12) are generally consumed within eight to fifteen hours under the reaction conditions. Attempts using the corresponding alkenyl and aryl bromides proceed to allene products with much slower reaction rates. The reactions of Table 1 (entries 1–12) are standardized using 20 mol % Pd2(dba)3 based on starting iodide. Efforts utilizing 10 mol % catalyst and 5 mol % catalyst led to incomplete (50–70%) consumption of 1 after 24 h, and subsequent sequential additions of catalyst in small quantities provided only modest improvement. We examined several ligands and found that AsPh3 provided the most effective reaction rates. Some success was achieved with the addition of tri-2-furylphosphine, whereas triphenylphosphine led to very slow rates of consumption of 1, and Fu conditions11 using P(tBu)3 and cesium fluoride afforded similar results. Finally, we have found that the addition of small amounts of CuI produced further enhancement of the rates of our reactions without altering the observed regioselectivity.12 Aryl iodides (entries 1, 7 and 12) have efficiently produced good yields of allenes 3. The thiophene and furan examples (entries 8 and 10) also proceeded readily to give 3i and 3k, respectively, although the isolated yields are somewhat diminished by the volatility of these products. Slower reactions are observed in the case of entries 5, 6 and 11, and small amounts of unreacted alkenyl iodides (approximately 10%) are recovered after 15 hours. Isomerization to the more stable E-unsaturated ester 3g occurs after the cross-coupling event since the corresponding E-iodide of 1g demonstrates a very slow rate of coupling with 2. On the other hand, the progress of reactions with 1g was monitored by 1H NMR studies using DMF(d6) and clearly indicated the production of the trans-ester 3g prior to isolation by flash chromatography.

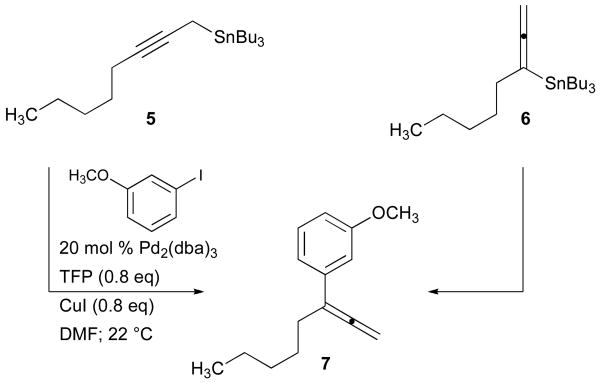

Preliminary investigations have been undertaken to gain mechanistic insight into these processes. For example, the Stille coupling of 1-tri-n-butylstannyl-2-octyne (5) with aryl iodide 1b gave allene 7 in high yield (95%) (Scheme 2). Under identical reaction conditions, an enriched mixture of stannane isomers 6 and 5 (70:30 ratio) exclusively led to the production of 7 (72%). Thus, the allylic transposition observed for reactions of 5 is not apparent in the reactions of allenylstannane 6. In addition, the formation of 7 precludes specific electronic or steric considerations due to the presence of TMS substitution in 2, and suggests substrate generality for our reaction conditions.

Scheme 2.

Stille reactions of propargyl and allenylstannanes 5 and 6.

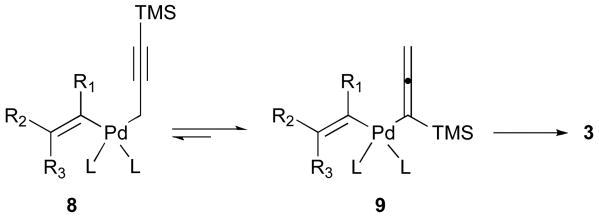

Finally, reaction mixtures lacking alkenyl iodide were constituted in anhydrous DMF(d6). Under these conditions, 1H NMR spectroscopy documented the stability of 2 with no evidence of isomerization to the corresponding allenylstannane over 24 hours at 22 °C. These observations suggest intriguing possibilities that initial transmetalation following the oxidative insertion of alkenyl iodide 1 may lead to the propargylic η1-palladium species 8 which undergoes isomerization to the η1-allenyl complex 9 via an η3-Pd intermediate (Scheme 3). Formation of the allene product 3 indicates a dynamic equilibration favoring the more stable palladium(II) complex 9 prior to reductive elimination. Alternatively, the mechanism for transmetalation of 2 may directly produce the η1-allenyl complex 9. In view of prior art leading to skipped enynes, we postulate that the transmetalation of propargylstannanes may be an important factor leading to the production of allenes 3.

Scheme 3.

Mechanistic considerations.

In summary, our studies of Stille reactions, involving 3-tri-n-butylstannyl-1-trimethylsilyl-1-propyne with aryl and alkenyl iodides, lead to the regioselective formation of allenylsilanes. This novel cross-coupling event generates useful reactive functionality which may be generally applicable. The examples of Table 1 have shown that preexisting functionality in starting alkenyl iodides is well tolerated, and this variant of the Stille reaction may have potential for applications in complex molecule synthesis.

Scheme 1.

Stille reactions of propyne (2).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the financial support of Indiana University and partial support by the National Institutes of Health (GM042897).

Notes and references

- 1.(a) Williams DR, Meyer KG. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:765. doi: 10.1021/ja005644l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Williams DR, Fultz MW. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:14550. doi: 10.1021/ja054201k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams DR, Morales-Ramos AI, Williams CM. Org Lett. 2006;8:4393. doi: 10.1021/ol0613160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Elsevier CJ, Kleijn H, Boersma J, Vermeer P. Organometallics. 1986;5:716. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tsutsumi K, Kawase T, Kakiuchi K, Ogoshi S, Okada Y, Kurosawa H. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1999;72:2687. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsutsumi K, Ogoshi S, Kakiuchi K, Nishiguchi S, Kurosawa H. Inorg Chim Acta. 1999;296:37. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsubuki M, Takahashi K, Sakata K, Honda T. Heterocycles. 2005;65:531. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma S, Zhang A. J Org Chem. 2002;67:2287. doi: 10.1021/jo0111098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heffron TP, Trenkle JD, Jamison TF. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:8913. [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Huang CW, Shanmugasundaram M, Chang HM, Cheng CH. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:3635. [Google Scholar]; (b) Mukai C, Takahashi Y. Org Lett. 2005;7:5793. doi: 10.1021/ol052179u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakamura H, Kamakura T, Ishikura M, Biellmann JF. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:5958. doi: 10.1021/ja039175+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.For leading references that describe the formation of allene 3a: Kjellgren J, Sundén H, Szabó KJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:1787. doi: 10.1021/ja043951b.Westmuze H, Vermeer P. Synthesis. 1979:390.

- 11.Littke AF, Schwarz L, Fu GC. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:6343. doi: 10.1021/ja020012f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.For background on Stille coupling, including Cu(I)-mediated reactions, see: Farina V, Krishnamurthy V, Scott WJ. Org React. 1997;50:1.Liebeskind LS, Fengl R. J Org Chem. 1990;55:5359.Han X, Stoltz BM, Corey EJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:7600.Bellina F, Carpita A, De Santis M, Rossi R. Tetrahedron. 1994;50:12029.