Abstract

We previously demonstrated that Bmi-1 extended the in vitro life span of normal human oral keratinocytes (NHOK). We now report that the prolonged life span of NHOK by Bmi-1 is, in part, due to inhibition of the TGF-β signaling pathway. Serial subculture of NHOK resulted in replicative senescence and terminal differentiation, and activation of TGF-β signaling pathway. This was accompanied with enhanced intracellular and secreted TGF-β1 levels, phosphorylation of Smad2/3, and increased expression of p15INK4B and p57KIP2. An ectopic expression of Bmi-1 in NHOK (HOK/Bmi-1) decreased intracellular and secreted TGF-β1 level, induced dephosphorylation of Smad2/3, and diminished the level of p15INK4B and p57KIP2. Moreover, Bmi-1 expression led to inhibition of TGF-β-responsive promoter activity in dose-specific manner. Knockdown of Bmi-1 in rapidly proliferating HOK/Bmi-1 and cancer cells increased the level of phosphorylated Smad2/3, p15INK4B and p57KIP2. In addition, an exposure of senescent NHOK to TGF-β receptor I kinase inhibitor or anti-TGF-β antibody resulted in enhanced replicative potential of cells. Taken together, these data suggest that Bmi-1 suppresses senescence of cells by inhibiting the TGF-β signaling pathway in NHOK.

Keywords: Bmi-1, TGF-β, senescence, lifespan extension

Introduction

Bmi-1, a member of the polycomb group (PcG) transcription repressors, is known to play an important role in carcinogenesis as it was initially identified as a c-myc-cooperating cellular oncogene in murine lymphomas [1]. Earlier studies showed that Bmi-1 inhibited senescence and extended the lifespan of normal human cells by repressing p16INK4A [2,3]. However, other recent studies demonstrated that ectopic expression of Bmi-1 was able to extend the lifespan of human cells in the absence of p16INK4A repression, suggesting that Bmi-1 may have targets other than p16INK4A [4–6]. In human mammary and nasopharyngeal epithelial cells, Bmi-1 alone has shown to induce immortalization [7,8], but not in normal human oral keratinocytes (NHOK) [9].

TGF-β is a potent growth inhibitor of epithelial cells [10]. TGF-β-induced growth arrest is primarily mediated through CDK inhibitors. In particular, TGF-β induces both p15INK4B expression and stabilization, resulting in inhibition of CDK4 and CDK6 [11,12]. TGF-β also leads to cell cycle arrest through p21WAF1 [13,14]. Although p21WAF1 is a direct target of p53, studies show that TGF-β-mediated p21WAF1 regulation is independent of p53 [14,15]. TGF-β also mediates growth arrest by increasing the activity of p27KIP1, thereby inhibiting the CDKs at G1 phase [16,17]. Recently, p57KIP2 was shown to play an important role in cell cycle arrest in response to TGF-β [18]. Therefore, TGF-β inhibits growth of epithelial cells through multiple CDK inhibitors.

The primary mediators of the TGF-β pathway are the Smads [19]. Extracellar TGF-β binds to the TGF-β type II receptor (TGFβRII), which associates with TGF-β type I receptor (TGFβRI). Formation of this receptor complex causes phosphorylation of the R-Smads, i.e., Smads 2 and 3 for TGF-β and activin receptors, and Smads 1, 5, and 8 for Bone Morphogenic Protein (BMP) receptors [20]. Phosphorylated Smad2 and Smad3 (Smad2/3) form a complex with Smad4 and translocate into nuclei and regulate the transcription of TGF-β-responsive genes [21,22]. Due to its cytostatic effects on cells, TGF-β pathway is frequently disrupted by somatic mutations in cancer [23–25].

We recently reported that Bmi-1 significantly extends the life span of normal human oral keratinocytes (NHOK) without causing cellular immortalization [9]. The cells expressing exogenous Bmi-1 continued to replicate beyond the normal replicative limit of 22 ±3 population doublings (PDs), at which time the parental NHOK exhibited accumulation of p16INK4A and cellular senescence [26]. Bmi-1 expression in NHOK did not cause notable reduction of p16INK4A level, suggesting that the repressive effects of Bmi-1 on p16INK4A alone may not be responsible for the prolonged lifespan in NHOK.

Recent findings with genomic wide analysis using polycomb group proteins suggested that Bmi-1 may target genes that are closely related to TGF-β signaling pathway [27]. An earlier study showed that the expression of TGF-β1 is elevated in terminally differentiating NHOK after completion of serial subculture [28], and that genes related to the TGF-β pathway were differentially regulated by Bmi-1 in NHOK when compared by microarray analysis [29]. Thus, in the current study, we investigated the possibility that Bmi-1 inhibits the TGF-β signaling in NHOK, thus conferring proliferative advantage leading to extended replication.

Materials and Methods

Cells, cell culture, and reagents

Primary normal human oral keratinocytes (NHOK) were prepared from keratinized oral epithelial tissues according to methods described in elsewhere [30]. Briefly, detached oral keratinocytes were seeded onto collagen-treated flasks and cultured in Keratinocyte Growth Medium (KGM) (Cambrex, East Rutherford, NJ, USA). We also established primary keratinocytes from epidermis (NHEK) using the same method. The cumulative population doublings (PDs) and replication kinetics were determined based on the number of NHOK harvested at every passage. SCC4 (squamous cell carcinoma) cancer cell line derived from tongue tumor was also included in the study.

Retroviral and lentiviral vector construction and transduction of cells

Retroviruses expressing Bmi-1 were constructed from pBabe-puro containing Bmi-1 cDNA, which was kindly provided by Dr. G. Dimri (Evanston Northwestern Healthcare Research Institute, Evanston, IL). Lentivirus-based shRNA expression plasmid pLL3.7 capable of knocking down the expression of endogenous Bmi-1 (pLL3.7-Bmi-1i) was constructed using double-stranded oligonucleotide cassette containing the Bmi-1 target sequence (5’-AAGGAATGGTCCACTTCCATT-3’) [31]. Detail procedures are described previously [4, 7, 9]. Briefly, the retroviruses, RV-B0 and RV-Bmi-1, were prepared by transfecting GP2-293 universal packaging cells (Clonetech, Mountain View, CA, USA) with retroviral vectors, pBABE (insertless plasmid) or pBABE-Bmi-1, along with pVSV-G envelope plasmid using a calcium-phosphate transfection method. The lentiviruses, LV-GFP and LV-Bmi-1i, were prepared by transfecting 293T cells with the RNAi plasmids, pLL3.7 (insertless plasmid) or pLL3.7-Bmi-1i, respectively, using calcium phosphate transfection method in the presence of the packaging plasmid (pCMVΔR8.2Vprx) and the envelope plasmid (pCMV-VSV-G) [32]. Two days after transfection, the virus supernatant was collected and concentrated by ultracentrifugation. The virus pellet was resuspended in KGM and was used for infection or stored in −80°C for later use.

Secondary NHOK cultures were infected with RV-B0, RV-Bmi-1, LV-GFP and LV-Bmi-1i in the presence of 6 µg/ml polybrene for three hours. All of these viruses consistently gave more than 90% of infection efficiency [4, 7, 9]. For the retroviruses, selection of cells began at 48 hours after infection with 1 µg/ml puromycin. The drug resistant cells were maintained in subcultures as described above. For the lentiviruses, the infected cells were photographed with the inverted fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Melvill, NJ, USA).

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from the cultured cells using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and was subjected to the optional column DNA digestion with the Rnase-Free Dnase (Qiagen) to eliminate any contaminating genomic DNA. DNA-free total RNA (5 µg) was dissolved in 15 µl H2O, and the RT reaction was performed in the first strand buffer containing 300U Superscript II (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA),10mM dithiotrietol, 0.5 µg random hexamer (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and 125 µM dNTP mixture (Promega). Real-time PCR was performed in triplicates for each sample with LC480 SYBR Green I master (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA) using universal cycling conditions on LightCycler 480 from Roche. A total of 45 cycles were executed, and the second derivative Cq value determination method was used to compare fold-differences. The following primers were used for PCR amplification:

p15INK4B primers, 5’- GAGGAGAACAAGGGCATGCCCAGTG - 3’ (forward) and 5’-

GCTTCCAGGAGCTGTCGCACCTTCT - 3’ (reverse); p16INK4A primers, 5’-

GCGCTGCCCAACGCACCGAATAGTT - 3’ (forward) and 5’ -

GTCGTGCACGGGTCGGGTGAGAGTG - 3’ (reverse); p21WAF1 primers, 5’-

ACAGCAGAGGAAGACCATGTGGACC - 3’ (forward) and 5’-

CGTTTTCGACCCTGAGAGTCTCCAG - 3’ (reverse); p57KIP2 primers, 5’-

GACCTTCCCAGTACTAGTGCGCACC - 3’ (forward) and 5’-

ATGTCCTGCTGGAAGTCGTAATCCC - 3’ (reverse); TGF-β1 primers, 5’-

TGTTCTTCAACACATCAGAGCTCCG - 3’ (forward) and 5’-

CCACGTGCTGCTCCACTTTTAACTT - 3’ (reverse); and GAPDH primers, 5’-

AGCCACATCGCTCAGACAC - 3’ (forward) and 5’- GCCCAATACGACCAAATCC - 3’ (reverse).

Western Blotting

Cells were lysed using lysis buffer (1% Triton X−100, 20mM Tris-HCl (pH7.5), 150mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 1mM EGTA, 2.5mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1mM β-glycerolphosphate, 1mM sodium orthovandate and PMSF) and sonicated with 3 bursts for 10 seconds each. Lysates (40–50 µg) from cells were fractionated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and transferred onto Immobilon protein membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Immobilized membrane was incubated with primary antibodies and probed with the respective secondary antibodies. The membrane was exposed and scanned using ChemiDoc System (Bio-Rad, Hurcules, CA, USA). The following antibodies were used: p15INK4B (DCS114.11), p57KIP2 (C-20), p53 (DO-1), p-Smad2/3 (Ser 423/425), TGF-β1 (V), and β-Actin (I-19) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA); Bmi-1 (F-6) from Upstate (Charlottesville, VA, USA); p21WAF1 (Ab-1) and p16INK4A (Ab-1) from EMD Biosciences, Inc. (San Diego, CA, USA); and p-Smad2, and Smad2 (L16D3) from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA, USA). The Western results are quantitated by normalizing to β-actin using Scion Image software (Frederick, MD, USA).

TGF-β1 ELISA assay

To measure secreted TGF-β1 by NHOK, supernatants at different PDs with or without Bmi-1 transduction were collected, centrifuged to remove any particulate materials, and stored in −80°C until the HOK/B0 cells underwent senescence. TGF-β1 ELISA assay was performed according to the protocol (BD OptEIA Set Human TGF-β1, BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA). Briefly, 96-well plates were precoated with Capture antibody overnight at 4°C. The plates were then blocked with Assay Diluent for 1 hr in RT and incubated with the collected samples for 2 hrs in RT followed by Detector (Detection Ab + SAv− HRP) for 1 hr in RT. The plates were incubated with Substrate solution for 30 min in RT in dark, and substrate reaction was stopped using Stop solution. The samples were read at 450nm within 30 min with λ correction 570 nm. The standard curve was established, and the reading value was normalized with the number of cells at the time of supernatant collection. Each sample was performed in triplicate.

Analysis of TGF-β responsive reporter activity

p3TP-Lux reporter plasmid, kindly provided by Dr. Joan Massague, was used for TGF-β responsive reporter assay. Cells were plated onto a twelve-well plate with approximately 1×105 cells per well. After 24 hours, the p3TP-Lux plasmid (1 µg/well) was transfected alone or together with pBABE-Bmi-1 (1 µg/well) using Lipofectin Reagent (Invitrogen). For the better comparison among cells with different transfection efficiencies, pRL-SV40 plasmid (0.005 µg/well) was also transfected into each cell and used for normalization of the p3TP-Lux reporter activities. After 24 hours, cells were treated with or without TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml), and incubated for additional 24 hours. Cells were collected, prepared, and processed according to the protocol provided from the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega Corporation). Luciferase activity was measured using a luminometer.

Proliferation curve

NHOK were plated onto the 12-well dish with 2×104 cells per well. After 24 hours, cells were treated with or without 1µM of TGF-β RI kinase inhibitor (TβRI-i), [3-(pyridine-2-yl)4-(4-quinonyl)]-1H-pyrazole (EMD Biosciences, Inc, Madison, WI, USA). Cells were either collected for cell counting or changed the medium every two days with fresh TβRI-i.

Sensecence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-Gal) staining

Senescing NHOK were treated with 1µM of TβRI-i or 10 ng/ml of α-TGF-β1 antibody (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) for 6 days. The cells were then fixed with 2% formaldehyde/0.2% glutaraldehyde for 3–5 min at the room temperature and stained for SA β-Gal activity in freshly prepared staining solution as described [33]. Dark-green colors indicating the presence of SA β-Gal activity was observed under the microscope. One thousands cells that include both β-Gal-positives and - negatives were counted in a random manner by a third person, and the percentages of β-Gal-positive cells were obtained.

Results

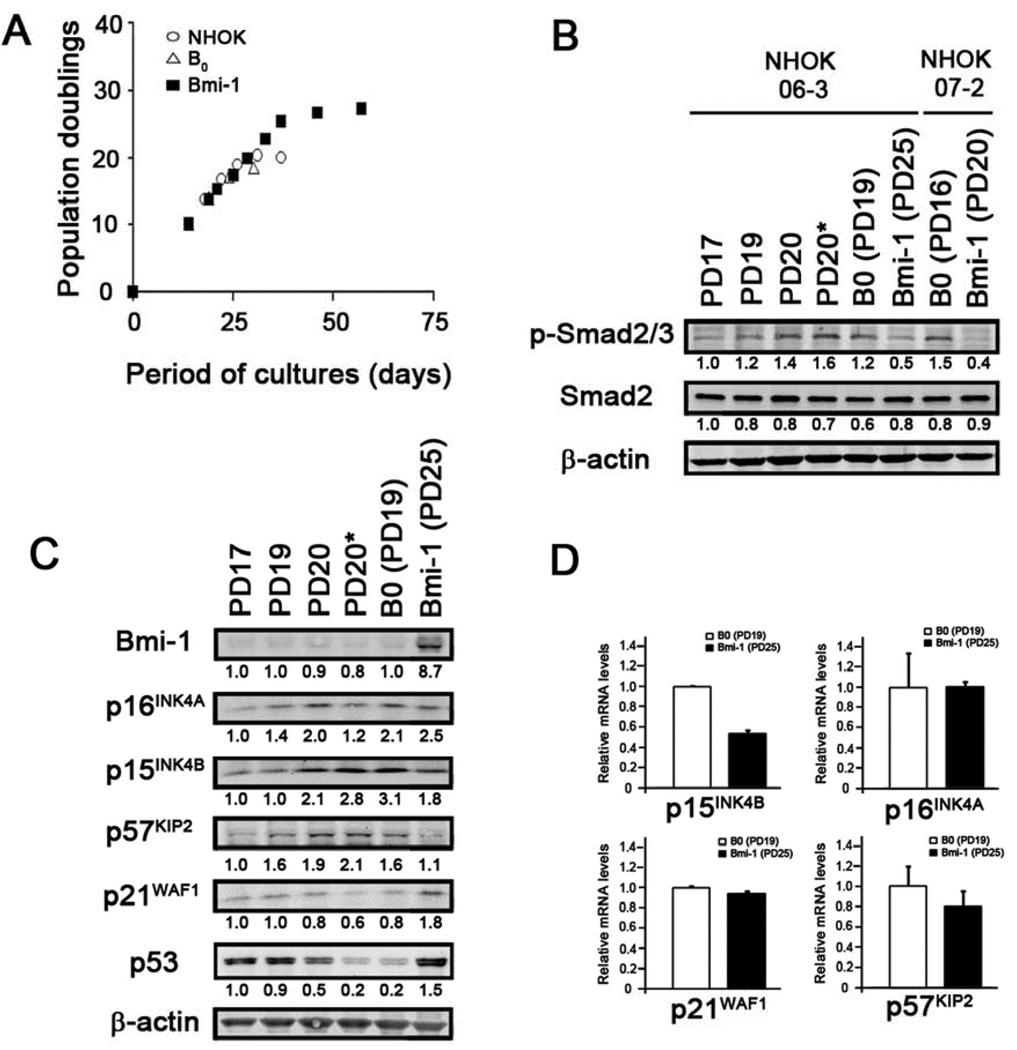

The overexpression of Bmi-1 is negatively correlated with the phosphorylation of Smad2/3 and the expression of p15INK4B and p57KIP2, but not of p16INK4A and p21WAF1

Central to the TGF-β pathway activation is the phosphorylation of Smad2 and Smad3 which leads to the translocation of activated Smad complex from cytoplasm to the nucleus and regulates TGF-β responsive genes [19]. To confirm the activation of the TGF-β signaling pathway in NHOK by serial subculture, we examined the phosphorylation status of Smad2/3. Primary NHOK were serially passaged until the cells completely underwent replication arrest and harvested at varying PD levels (Figure 1A). Western blotting was performed to determine the phosphorylation status of Smad2/3 and showed increased phosphorylation in cells with higher PD levels (Figure 1B). To determine the effects of Bmi-1 on TGF-β signaling in NHOK, we constructed a retroviral vector expressing full-length wild-type Bmi-1 (RV-Bmi-1) and infected NHOK. These cells, named HOK/Bmi-1, demonstrated reduced level of Smad2/3 phosphorylation compared with the cells infected with empty viral vector (RV-B0) (Figure 1B). We also compared the protein expression levels of several CDK inhibitors, i.e., p15INK4B, p16INK4A, p21WAF1, and p57KIP2, in NHOK at varying PD levels and with or without Bmi-1 transduction. The level of p15INK4B and p57KIP2 expression progressively increased during subcultures in the parental NHOK cultures, but not in those expressing exogenous Bmi-1 (Figure 1C). Consistent with the previous reports [4,5], Bmi-1 transduction did not alter the expression level of p16INK4A in NHOK (Figure 1C). mRNA expression levels of p15INK4B, p16INK4A and p57KIP2 were similar to the protein levels, although a marginal decrease was observed in p57KIP2 (Fig. 1D). Interestingly, the protein expression of p21WAF1 decreased as NHOK senesced and re-expressed upon Bmi-1 transduction (Figure 1C) despite the fact that mRNA of p21WAF1 was not changed by Bmi-1 (Figure 1D). When we also checked for the p53 protein level, similar expression pattern was observed as that of p21WAF1. Collectively, Bmi-1 transduction decreased expression of p15INK4B and p57KIP2, but not of p16INK4A and p21WAF1

Figure 1. Bmi-1 transduction in NHOK is negatively correlated with the phosphorylation of Smad2/3 and the expression of p15INK4B and p57KIP2, but not of p16INK4A and p21WAF1.

(A) Secondary NHOK cultures (06-3) were infected with RV-B0 (not shown) or RV-Bmi-1, selected with puromycin (1 µg/ml), and maintained in serial subcultures. Replication kinetics were determined as described previously. (B) Cells harvested at each passage were subjected to Western blot analysis using antibody specific to phosphorylated Smad2/3 at Ser423 and Ser425 residues. Intracellular level of Smad2 was also determined. β-actin was used as a loading control. Another independent strain of NHOK (07-2) was also included for comparison. PD20 indicates senescent NHOK, whereas PD20* indicates terminally differentiated, non-dividing NHOK harvested 4 days after the onset of senescence. (C) Western blotting was performed with NHOK (06-3) for Bmi-1, p53, and various CDK inhibitors. β-actin was used as a loading control. (D) NHOK (06-3) infected with either RV-B0 or RV-Bmi-1 at PD19 and PD25, respectively, were harvested for qRT-PCR analysis. GAPDH was used to normalize the values. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

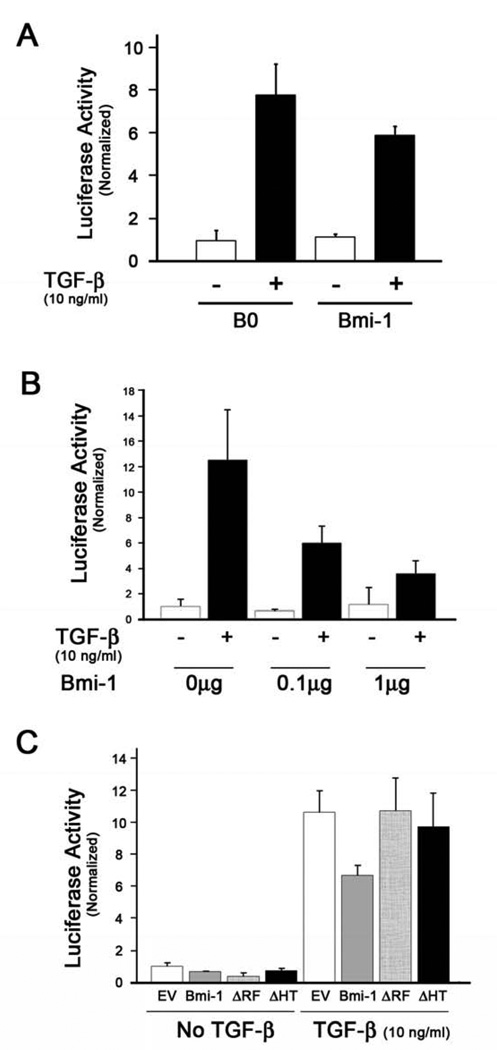

Bmi-1 attenuates the TGF-β-induced p3TP-lux activities in NHOK

To further confirm the inhibitory effects of Bmi-1 on TGF-β signaling, we tested the effects of Bmi-1 on TGF-β-dependent promoter activity. For this purpose, we used the p3TP-lux reporter plasmid, which contains three copies of a tetradecanoyl phorbol acetate (TPA)-responsive element from the human collagenase promoter region and a TGF-β-responsive element from the human plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1) promoter region [34]. Upon exposure to 10 ng/ml TGF-β1, p3TP-Lux promoter activity was markedly increased compared to the untreated control (Figure 2A). However, the extent of the TGF-β-dependent promoter activity was significantly reduced in cells after Bmi-1 transduction compared with the B0 control. To further confirm this finding, different amounts of plasmids containing Bmi-1 were transiently transfected in NHOK, and p3TP-Lux activity was measured with or without TGF-β1 treatment. When the plasmid containing Bmi-1 was introduced at varying amounts from 0, 0.1 and 1 µg, the promoter activity decreased in dose-dependent manner in cells treated with 10 ng/ml TGF-β1 (Figure 2B). We also compared the promoter inhibitory effects of two mutant variants of Bmi-1, Bmi-1ΔRF and Bmi-1ΔHT, which lack the ring finger and helix-turn-helix-turn domains, respectively [7]. Compared with the empty vector (EV) control, transfection of wild-type Bmi-1 led to approximately 40% reduction in the TGF-β-dependent promoter activity, while the Bmi-1 mutants did not show notable reduction in promoter activity (Figure 2C). These data suggest the requirement of both RF and HT domains of Bmi-1 for its inhibitory effects on the TGF-β-induced p3TP-lux activity.

Figure 2. Bmi-1 transduction attenuates the TGF-β-induced p3TP-Lux activities in dose-dependent manner.

(A) HOK/B0 and HOK/Bmi-1 cells were transfected with p3TP-Lux reporter plasmid. After 24 hours, TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml) was treated for additional 24 hours, and cells were harvested to measure luciferase activity. (B) Different amounts of RV-Bmi-1 were transiently cotransfected with the p3TP-Lux reporter plasmid in NHOK. pRL-SV40 plasmid was also transfected to normalize the transfection efficiency. After 24 hrs post-transfection, the cells were treated with or without TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml) for additional 24 hrs. Cells were harvested and the luciferase activity was measured. (C) Different mutants of Bmi-1 (ΔRF and ΔHT) were transiently cotransfected with the p3TP-Lux reporter plasmid in NHOK. pRL-SV40 plasmid was also transfected to normalize the transfection efficiency. After 24 hrs post-transfection, the cells were treated with or without TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml) for additional 24 hrs. Cells were harvested and the luciferase activity was measured.

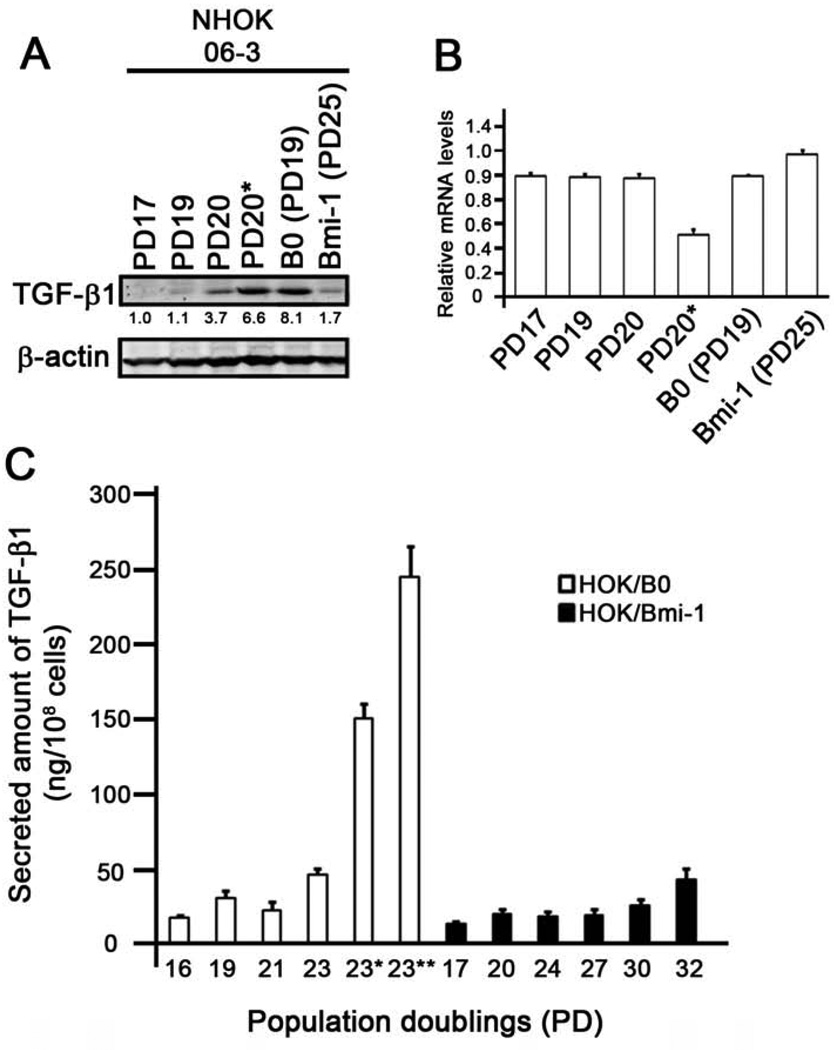

Bmi-1 decreases the protein, but not mRNA, of TGF-β1

We previously showed that subcultured NHOK undergo distinct phases of replication including the exponential, senescing, and the senescent phases [26]. The senescent phase is non-replicative state during which time the cells undergo terminal differentiation. TGF-β1 expression is elevated in terminally differentiating NHOK after completion of serial subculture [28]. Also, TGF-β1 expression is drastically induced in differentiating culture of NHEK after exposure to 1.5 mM Ca++ and paralleled the induction of involucrin (data not shown). Since our data demonstrated that Bmi-1 has suppressive effects on TGF-β1 signaling in NHOK, we checked for the possibility that Bmi-1 inhibits TGF-β1 expression. The levels of TGF-β1 was determined in NHOK at varying PD levels until replicative senescence and terminal differentiation, and in those cells infected with RV-Bmi-1 by Western blotting. Intracellular TGF-β1 protein level increased in non-replicative NHOK during terminal differentiation, and was drastically reduced in cells after Bmi-1 transduction compared with the control (B0) (Figure 3A). Interestingly, these changes in TGF-β1 expression was not detected at the mRNA level as determined by qRT-PCR (Figure 3B). Consistent with this finding, the level of secreted TGF-β1 increased in terminally differentiating NHOK, but such increase was not observed in the HOK/Bmi-1 cells (Figure 3C). These data suggest that Bmi-1 inhibits the intracellular accumulation and secretion of TGF-β1 in NHOK.

Figure 3. Bmi-1 decreases the expression levels of protein, but not mRNA, of TGF-β1.

(A) NHOK (06-3) at varying PD levels and after Bmi-1 transduction were harvested for Western blotting to determine the intracellular TGF-β1 protein level. β-actin was used as a loading control. PD20 indicates senescent NHOK, whereas PD20* indicates terminally differentiated, non-dividing NHOK harvested 4 days after the onset of senescence. (B) qRT-PCR for TGF-β1 mRNA was performed using the same cells. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (C) NHOK (10-2) at varying PD levels with or without Bmi-1 were serially subcultured. The supernatants at the every passage were obtained, and the secreted TGF-β1 were measured using ELISA assay. The secreted amounts of TGF-β1 were normalized with the number of cells, and the experiment was performed in triplicate. PD23 indicates senescent NHOK, whereas PD23* and PD23** indicates terminally differentiating, non-dividing NHOK harvested 4 and 8 days after the onset of senescence, respectively.

Bmi-1 knockdown induced phosphorylation of Smad2/3 in NHOK/Bmi-1 cells

Since Smad2/3 phosphorylation was inhibited by Bmi-1 transduction in NHOK, we questioned whether knockdown of Bmi-1 by RNA interference (RNAi) could restore phosphorylation of Smad2/3. We previously constructed the lentiviral vector expressing short hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting Bmi-1 [4]. We utilized this viral vector (LV-Bmi-1i) or the empty control (LV-EGFP) to knockdown the Bmi-1 expression in the HOK/Bmi-1 cells (Figure 4A). The cells were harvested for Western blot analysis three days after infection during which time no phenotypic alteration was noted. We confirmed efficient knockdown of Bmi-1 in cells infected with LV-Bmi-1i, which also exhibited the restoration of Smad2/3 phosphorylation while the intracellular level of Smad2 remained constant (Figure 4B). This was also observed in an independent strain of NHOK and an oral squamous cell carcinoma cell line (SCC4) which expresses high level of Bmi-1 (Figure 4C). Furthermore, Bmi-1 knockdown led to increased expression of p15INK4B and p57KIP2 in NHOK and SCC4 cells, indicating the restoration of the TGF-β signaling.

Figure 4. Bmi-1 knockdown induces phosphorylation of Smad2/3 in NHOK and SCC4 cells.

(A) HOK/Bmi-1 cells were infected with lentiviruses capable of knocking down Bmi-1. The photographs were taken using the inverted fluorescence microscope (Nikon). Original magnification, 100×. (B) Three days after infection during which cells exhibited no phenotypic alterations, the cells were harvested for Western blotting analysis to determine the level of Bmi-1, p-Smad2/3, and Smad2. (C) Similar experiment was performed using different strain of HOK/Bmi-1 (07-2) cells and SCC4 cell line. Bmi-1, p-Smad2, p15INK4B, p57KIP2, and p16INK4A were also probed. β-Actin was used in all experiments as a loading control.

Inhibition of TGF-β signaling pathway causes the bypass of senescence in NHOK

In the next experiment, we tested whether inhibiting TGF-β signaling would bypass the the replication arrest during serial subcultures. Senescent NHOK were cultured in the presence of TGF-β type I receptor inhibitor (TβRI-i) and anti-TGF-β1 antibody, and cells were examined for the phenotypic alterations. At 1 µM TβRI-i, the cells exhibited undifferentiated morphology, enhanced replication, and reduced senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA β-Gal) activity compared with those exposed to DMSO as control (Figures 5A, 5B and 5C). Similar findings were also noted in cells treated with the anti-TGF-β1 antibody (Figure 5B and 5C). These results are in agreement with a previous study showing that defects in TGF-β signaling bypassed oncogene-induced premature senescence in mouse keratinocytes [35]. Since Bmi-1 transduction significantly extended the life span in NHOK [9], our data indicate that inhibition of intracellular and extracellular TGF-β accumulation and downstream signaling involving Smad 2/3 phosphorylation by Bmi-1 may be one underlying mechanism

Figure 5. TGF-β inhibition in senescent NHOK enhances the cell proliferation capacity by lowering the senescence response.

(A) Senescent NHOK were treated with DMSO or 1µM of TβRI-I 24 hours after plating. Every 2 days, NHOK were collected for cell counting or changed the medium containing the fresh TβRI-i. The experiments were performed in triplicates. (B) Senescent NHOK were treated with DMSO, 1 µM of TβRI-i or 10 ng/ml of anti-TGF-β Ab for 6 days and stained for SA β-Gal. One thousands cells were randomly selected and counted for the SA β-Gal positives. The percentage of SA β-Gal staining is shown in the bar graph. (C) Senescent NHOK were exposed to 1µM TβRI-i or 10 ng/ml of anti-TGF-β Ab for 6 days, and stained for SA β-Gal. Original magnification, 100×.

Discussion

Recent findings suggested that Bmi-1 may have a role in regulating in the TGF-β signaling pathway [27]. An earlier study showed that defects in TGF-β signaling overcome oncogene-induced premature senescence in mouse keratinocytes [35], and Bmi-1 mediates the bypass of replicative senescence in normal human keratinocytes [9]. We now report that Bmi-1 extends the replicative life span of NHOK by inhibiting TGF-β signaling pathway via two mode of actions; one by suppressing the expression of TGF-β1 (Figure 3), and the other by attenuating the TGF-β signal transduction (Figure 1 and 2).

Previous studies showed that the growth inhibitory effects of TGF-β are linked to the intracellular induction of p15INK4B p21WAF1, and p57KIP2 [11,14,18,36]. We previously observed increase in p16INK4A expression during senescence in NHOK [37]. However, when Bmi-1 was transduced in NHOK, marked increase in replicative lifespan occurred in the absence of notable change in p16INK4A repression [9]. This was also evident in the current study, which showed comparable level of p16INK4A expression in NHOK after Bmi-1 transduction or infection with the empty viral vector B0 (Figure 1C). While the role of p16INK4A in senescence is well documented [7,8], whether its repression is the cause of Bmi-1-mediated extension of lifespan in NHOK is questionable. We previously reported the loss of p21WAF1 and p53 expression levels during replicative senescence in NHOK [30]. Thus, restoration of these two protein expression levels in NHOK after Bmi-1 transduction is not surprising. This observation is also in accordance with others’ finding in which p21WAF1 was shown to have a minor contribution to senescence in HMEC [12].

For other CDK inhibitors, we consistently observed reduction of p15INK4B and p57KIP2 in cells expressing exogenous Bmi-1 or induction after knockdown of Bmi-1 (Figures 1C and 4C). These results support a notion that Bmi-1 may inhibit TGF-β signaling via p15INK4B and p57KIP2. It remains unknown, however, whether Bmi-1 directly interferes with expression of p15INK4B and/or p57KIP2, or indirectly through dysregulating the protein stability because a marginal change was observed at least in p57KIP2 at the mRNA level (Figure 1D).

Our data showed that both RF and HT domains of Bmi-1 are required to attenuate the TGF-β-responsive promoter activity (Figure 2C). The RF domain is required for the sublocalization of Bmi-1 to the rim of the nucleus and for its interactions with other PcG proteins, whereas the HT domain is necessary for transcriptional repression function [38,39]. These notions suggest that inhibition of TGF-β signaling requires nuclear translocation of Bmi-1 and possible interaction with other PcG proteins. Since Bmi-1 is a transcription repressor, it is also possible that Bmi-1 mediates its inhibitory effects through other unknown proteins yet to be found.

During replicative senescence and terminal differentiation, NHOK exhibited no correlation in between mRNA and protein levels of TGF-β1; TGF-β1 mRNA levels remained constant until the terminally differentiated stage (PD20*), during which intracellular and extracellular protein levels increased significantly in spite of a decrease in TGF-β1 mRNA level by half (Figure 3A, 3B and 3C). Interestingly, Bmi-1 transduction led to marked loss of intracellular and secretory TGF-β1 protein level, but not the mRNA level (Figures 3A, 3B and 3C). Although it should be further examined experimentally, the effects of Bmi-1 on TGF-β1 expression level appears to be at the post-translation level, and it is unlikely for Bmi-1 to directly impact the reduced level of TGF-β at the transcriptional level.

Although TGF-β1 is a potent inhibitor of primary epithelial cells, a large number of reports convincingly show that TGF-β1 promotes proliferation of the cells in late stages of cancer development [40–42]. In many cancer cell lines and tissues, Bmi-1 is shown to be highly expressed [43–45]. Based upon the current knowledge, it is difficult to explain how, if there are any, Bmi-1 and TGF-β pathway intervene each other to promote tumor-promoting activities in cancer cells. On the other hand, it is tempting to speculate that the effects of Bmi-1 on TGF-β pathway play a role at the early steps in carcinogenesis because enhanced Bmi-1 expression was also detected in the mild epithelial dysplastic lesions [4]. Further studies on the role of Bmi-1 in TGF-β pathway in cancer cells warrant closer examination.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This study was supported in part by the grants (K08DE17121 to R.H.K.; K02DE18959 and R01DE18295 to M.K.K.; R01DE14147 to N.H.P.) from NIDCR/NIH. M.K.K. was also supported by the Jack Weichman Endowment Fund.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.van Lohuizen M, Verbeek S, Scheijen B, Wientjens E, van der Gulden H, Berns A. Identification of cooperating oncogenes in E mu-myc transgenic mice by provirus tagging. Cell. 1991;65:737–752. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90382-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacobs JJ, Kieboom K, Marino S, DePinho RA, van Lohuizen M. The oncogene and Polycomb-group gene bmi-1 regulates cell proliferation and senescence through the ink4a locus. Nature. 1999;397:164–168. doi: 10.1038/16476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacobs JJ, Scheijen B, Voncken JW, Kieboom K, Berns A, van Lohuizen M. Bmi-1 collaborates with c-Myc in tumorigenesis by inhibiting c-Myc-induced apoptosis via INK4a/ARF. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2678–2690. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.20.2678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kang MK, Kim RH, Kim SJ, Yip FK, Shin KH, Dimri GP, Christensen R, Han T, Park N-H. Elevated Bmi-1 expression is associated with dysplastic cell transformation during oral carcinogenesis and is required for cancer cell replication and survival. Br. J. Cancer. 2006;96:126–133. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee K, Adhikary G, Balasubramanian S, Gopalakrishnan R, McCormick T, Dimri GP, Eckert RL, Rorke EA. Expression of Bmi-1 in Epidermis Enhances Cell Survival by Altering Cell Cycle Regulatory Protein Expression and Inhibiting Apoptosis. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2007;128:9–17. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Douglas D, Hsu JH, Hung L, Cooper A, Abdueva D, van Doorninck J, Peng G, Shimada H, Triche TJ, Lawlor ER. BMI-1 promotes ewing sarcoma tumorigenicity independent of CDKN2A repression. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6507–6515. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dimri GP, Martinez JL, Jacobs JJ, Keblusek P, Itahana K, Van M M, Campisi J, Wazer DE, Band V. The Bmi-1 oncogene induces telomerase activity and immortalizes human mammary epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4736–4745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Song LB, Zeng MS, Liao WT, Zhang L, Mo HY, Liu WL, Shao JY, Wu QL, Li MZ, Xia YF, Fu LW, Huang WL, Dimri GP, Band V, Zeng YX. Bmi-1 is a novel molecular marker of nasopharyngeal carcinoma progression and immortalizes primary human nasopharyngeal epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6225–6232. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim RH, Kang MK, Shin KH, Oo ZM, Han T, Baluda MA, Park N-H. Bmi-1 cooperates with human papillomavirus type 16 E6 to immortalize normal human oral keratinocytes. Exp. Cell Res. 2007;313:462–472. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quintanilla M, Perez-Gomez E, Romero D, Pons M, Renart J. Molecular mechanisms of basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma: TGF-beta pathway and carcinogenesis of epithelial skin tumors. Landes Bioscience and Springer Science + Business Media. 2006:80–93. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reynisdottir I, Polyak K, Iavarone A, Massague J. Kip/Cip and Ink4 Cdk inhibitors cooperate to induce cell cycle arrest in response to TGF-beta. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1831–1845. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.15.1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sandhu C, Garbe J, Bhattacharya N, Daksis J, Pan CH, Yaswen P, Koh J, Slingerland JM, Stampfer MR. Transforming growth factor beta stabilizes p15INK4B protein, increases p15INK4B-cdk4 complexes, and inhibits cyclin D1-cdk4 association in human mammary epithelial cells. Mol. Cell Biol. 1997;17:2458–2467. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.5.2458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li CY, Suardet L, Little JB. Potential role of WAF1/Cip1/p21 as a mediator of TGF-beta cytoinhibitory effect. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:4971–4974. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.10.4971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Datto MB, Li Y, Panus JF, Howe DJ, Xiong Y, Wang XF. Transforming growth factor beta induces the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 through a p53-independent mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1995;92:5545–5549. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elbendary A, Berchuck A, Davis P, Havrilesky L, Bast RC, Jr, Iglehart JD, Marks JR. Transforming growth factor beta 1 can induce CIP1/WAF1 expression independent of the p53 pathway in ovarian cancer cells. Cell Growth Differ. 1994;5:1301–1307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Polyak K, Kato JY, Solomon MJ, Sherr CJ, Massague J, Roberts JM. p27Kip1, a cyclin-Cdk inhibitor, links transforming growth factor-beta and contact inhibition to cell cycle arrest. Genes Dev. 1994;8:9–22. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ciarallo S, Subramaniam V, Hung W, Lee JH, Kotchetkov R, Sandhu C, Milic A, Slingerland JM. Altered p27(Kip1) phosphorylation, localization, and function in human epithelial cells resistant to transforming growth factor beta-mediated G(1) arrest. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002;22:2993–3002. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.9.2993-3002.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scandura JM, Boccuni P, Massague J, Nimer SD. Transforming growth factor beta-induced cell cycle arrest of human hematopoietic cells requires p57KIP2 up-regulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:15231–15236. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406771101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Massagué J. How cells read TGF-beta signals. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000;1:169–178. doi: 10.1038/35043051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Massagué J. TGF-beta in Cancer. Cell. 2008;134:215–230. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moustakas A, Pardali K, Gaal A, Heldin CH. Mechanisms of TGF-beta signaling in regulation of cell growth and differentiation. Immunol. Lett. 2002;82:85–91. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(02)00023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shi Y, Massague J. Mechanisms of TGF-beta signaling from cell membrane to the nucleus. Cell. 2003;113:685–700. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00432-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Derynck R, Akhurst RJ, Balmain A. TGF-beta signaling in tumor suppression and cancer progression. Nat. Genet. 2001;29:117–219. doi: 10.1038/ng1001-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Massague J, Blain SW, Lo RS. TGF-beta signaling in growth control, cancer, and heritable disorders. Cell. 2000;103:295–309. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wakefield LM, Roberts AB. TGF-beta signaling: positive and negative effects on tumorigenesis. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2002;12:22–29. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(01)00259-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kang MK, Bibb C, Baluda MA, Rey O, Park N-H. In vitro replication and differentiation of normal human oral keratinocytes. Exp. Cell Res. 2000;258:288–297. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bracken AP, Dietrich N, Pasini D, Hansen KH, Helin K. Genome-wide mapping of Polycomb target genes unravels their roles in cell fate transitions. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1123–1136. doi: 10.1101/gad.381706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Min BM, Woo KM, Lee G, Park N-H. Terminal differentiation of normal human oral keratinocytes is associated with enhanced cellular TGF-beta and phospholipase C-gamma 1 levels and apoptotic cell death. Exp. Cell Res. 1999;249:377–385. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yip FK, Kang MK, Park N-H. Microarray analysis of Bmi-1 downstream genes in normal human oral keratinocytes. J. Calif. Dent. Assoc. 2007;35:858–864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kang MK, Guo W, Park N-H. Replicative senescence of normal human oral keratinocytes is associated with the loss of telomerase activity without shortening of telomeres. Cell Growth Differ. 1998;9:85–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bracken AP, Pasini D, Capra M, Prosperini E, Colli E, Helin K. EZH2 is downstream of the pRB-E2F pathway, essential for proliferation and amplified in cancer. EMBO J. 2003;22:5323–5335. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Naldini L, Blomer U, Gallay P, Ory D, Mulligan R, Gage FH, Verma IM, Trono D. In vivo gene delivery and stable transduction of nondividing cells by a lentiviral vector. Science. 1996;272:263–267. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5259.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dimri GP, Lee X, Basile G, Acosta M, Scott G, Roskelley C, Medrano EE, Linskens M, Rubelj I, Pereira-Smith O, Peacocke M, Campisi J. A biomarker that identifies senescent human cells in culture and in aging skin in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1995;92:9363–9367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wrana JL, Attisano L, Carcamo J, Zentella A, Doody J, Laiho M, Wang XF, Massague J. TGF beta signals through a heteromeric protein kinase receptor complex. Cell. 1992;71:1003–1014. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90395-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tremain R, Marko M, Kinnimulki V, Ueno H, Bottinger E, Glick A. Defects in TGF-beta signaling overcome senescence of mouse keratinocytes expressing v-Ha-ras. Oncogene. 2000;19:1698–1709. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hannon GJ, Beach D. p15INK4B is a potential effector of TGF-beta-induced cell cycle arrest. Nature. 1994;371:257–261. doi: 10.1038/371257a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kang MK, Kameta A, Shin KH, Baluda MA, Kim HR, Park N-H. Senescence-associated genes in normal human oral keratinocytes. Exp. Cell Res. 2003;287:272–281. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alkema MJ, Bronk M, Verhoeven E, Otte A, van 't Veer LJ, Berns A, van Lohuizen M. Identification of Bmi1-interacting proteins as constituents of a multimeric mammalian polycomb complex. Genes Dev. 1997;11:226–240. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.2.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cohen KJ, Hanna JS, Prescott JE, Dang CV. Transformation by the Bmi-1 oncoprotein correlates with its subnuclear localization but not its transcriptional suppression activity. Mol. Cell Biol. 1996;16:5527–5535. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.10.5527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rahimi RA, Leof EB. TGF-beta signaling: A tale of two responses. J. Cell. Biochem. 2007;102:593–608. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leivonen SK, Kahari VM. Transforming growth factor-beta signaling in cancer invasion and metastasis. Int. J. Cancer. 2007;121:2119–2124. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Buck MB, Knabbe C. TGF-beta signaling in breast cancer. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006;1089:119–126. doi: 10.1196/annals.1386.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vonlanthen S, Heighway J, Altermatt HJ, Gugger M, Kappeler A, Borner MM, van Lohuizen M, Betticher DC. The bmi-1 oncoprotein is differentially expressed in non-small cell lung cancer and correlates with INK4A-ARF locus expression. Br. J. Cancer. 2001;84:1372–1376. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim JH, Yoon SY, Jeong SH, Kim SY, Moon SK, Joo JH, Lee Y, Choe IS, Kim JW. Overexpression of Bmi-1 oncoprotein correlates with axillary lymph node metastases in invasive ductal breast cancer. Breast. 2004;13:383–388. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Breuer RH, Snijders PJ, Sutedja GT, Sewalt RG, Otte AP, Postmus PE, Meijer CJ, Raaphorst FM, Smit EF. Expression of the p16(INK4a) gene product, methylation of the p16(INK4a) promoter region and expression of the polycomb-group gene BMI-1 in squamous cell lung carcinoma and premalignant endobronchial lesions. Lung Cancer. 2005;48:299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2004.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]