Abstract

Objective

To examine subjective ratings of QoL among older adults with advanced illness.

Design

Observational cohort study with interviews at least every 4 months for up to 2 years conducted between December, 1999 and December, 2002.

Setting

Participants’ homes.

Participants

185 community-dwelling individuals age 60 years or older with advanced cancer, heart failure, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Main Outcome Measure

Participants were asked, “How would you rate your overall quality of life?”

Results

Among participants who died, 46% reported good or best possible quality of life at their final interview, 21% reported improvement in QoL from their penultimate to final interview, and 39% reported no change. Nearly one-half (49%), of participants reported two or more changes in the direction of their QoL trajectories (e.g. QoL improved then declined). As measured over time in a multivariable longitudinal regression analysis, greater ADL disability (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 0.85, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.75, 0.95) and depressed mood (AOR 0.42, 95%CI 0.27, 0.66) were associated with a lower QoL while higher self-rated health (AOR 4.79, 95% CI 2.99, 7.69) and having grown closer to one’s church (AOR 1.99, 95% CI 1.17, 3.39) were associated with a higher QoL.

Conclusions

While declining QoL is not an inevitable consequence of advancing illness, individuals’ ratings of QoL are highly variable over time, suggesting that subjective QoL may be influenced by temporary factors. Functional status, depression, and connection to one’s religious community are shared determinants of QoL.

Keywords: Quality of life, longitudinal analysis, chronic disease

INTRODUCTION

In older patients with advanced illness for whom little can be done to alter disease trajectories, maintaining quality of life (QoL) becomes an increasingly important goal of care. There has been little longitudinal study of QoL among older persons with advanced disease. Evaluation of QoL has generally focused on health-related QoL. Measurement of health-related QoL is based on an assessment of physical and mental health, including such factors as physical and emotional function, symptoms, and disease processes.1 By definition, this conceptualization presumes that QoL worsens as health status declines.2, 3 However, it has also been argued that health-related QoL cannot be separated out from the broader construct of global QoL.4 Global QoL has been identified by both clinicians and patients as a multidimensional construct comprising both health-related and subjective components.5-8 It has been proposed that, because global QoL is subjective, it is best captured with the use of a single question asking respondents to rate their overall QoL.9 Although there is some evidence to support an association between health-status and global QoL,10 it has also long been recognized that persons with substantial health problems and/or disability may report experiencing a high QoL.3 This finding suggests that QoL may not be directly associated with health-status and, in turn, that decline in QoL may not be an inevitable consequence of disease progression. There have been few studies directly examining changes in subjective ratings of QoL over time among persons with serious illness, so that the data on the extent to which subjective ratings of QoL are influenced by health status is limited.

The purpose of this study was to provide a longitudinal examination of global QoL among older adults with advanced illness. We examined both changes in QoL among the study cohort as a whole and among individual participants. We also evaluated factors associated with global QoL ratings in order to determine the relationship between QoL and both health and psychosocial characteristics.

METHODS

Participants

Study participants were 60 years or older, had a primary diagnosis of cancer, chronic pulmonary obstructive disease (COPD), or heart failure (HF), and were being cared for in either subspecialty outpatient practices in greater New Haven or in one of three area hospitals: a university teaching hospital, a community hospital, and a Veteran’s Administration hospital. The human investigations committee of each of the participating hospitals approved the study protocol. All patients provided written informed consent.

Sequential charts were screened by trained research nurses_for the primary eligibility criterion, advanced illness, as defined according to either the clinical criteria used by Connecticut Hospice11 or those used in the Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment (SUPPORT).12 In order to improve prognostication with respect to advanced illness, an additional eligibility criterion, need for assistance with at least 1 instrumental activity of daily living (IADL),13 was determined by telephone screening. Patients were excluded from the study if they had cognitive impairment, as measured by the Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire and the Executive Interview, a test of executive functioning,14, 15 because the study relied on the accuracy of participant self-report or if they were not full-time residents of Connecticut because data collection was performed face-to-face. Screening and enrollment were stratified according to the diagnosis in order to enroll approximately equal numbers of patients with cancer, HF, and COPD.

Of the 548 patients identified as eligible by chart review, 30 had physicians who did not grant approval for further contact, 6 could not be reached for telephone screening, 24 died before they were called, and 18 declined the telephone screen. Of the 470 patients receiving the telephone screen, 108 were excluded because they required no assistance with IADLs, 77 because of cognitive impairment, and 6 because they were not full-time Connecticut residents. Of the 279 eligible participants, 2 died before enrollment and 51 refused participation. The final sample consisted of 226 patients. Comparative analysis did not detect significant differences between participants and non-participants according to age or sex. Among eligible patients with HF, 8% refused participation as compared with 19% of patients with cancer and 25% of patients with COPD (p = 0.02). Of the 226 participants, 8 (4%) withdrew after the initial interview, 26 (12%) died before completing a follow-up interview, and 7 (4%) were unable to complete full follow-up interviews. The 185 patients who underwent at least 2 interviews were included in the current study.

Data Collection

Participants were interviewed in their homes at least every four months for two years or until they either became too sick to participate or died. If a participant experienced a decline in health status, as determined during a monthly telephone call, the next interview was scheduled immediately. We defined decline in health status as a new disability in a basic activity of daily living (ADL),16 a prolonged hospitalization (≥7 days), a hospitalization resulting in discharge to a nursing home or rehabilitation facility, or the introduction of hospice services. This interview schedule allowed us to minimize respondent burden while continuing to obtain interviews as participants’ illnesses progressed. All variables were obtained by self-report.

Of the 185 participants, 83% participated in at least 3 interviews, 66% in at least 4 interviews and 31% participated in 7 or more interviews. In the 51% of patients who died, final interviews were performed a median of 87 days prior to death (interquartile range 42, 112).

The outcome measure, assessed at each interview, was a global QoL question: “How would you rate your overall quality of life?” Response choices included best possible, good, fair, poor, or worst possible.

Independent variables included measures of sociodemographic, health, and psychosocial status. Sociodemographic variables included age, education, sex, race/ethnicity, sufficiency of monthly income,17 living arrangement, and marital status. Health status variables included self-rated health18 (response choices: excellent, very good, or good vs. fair or poor); extent of ADL disability16 (range 0-14); self-rated life-expectancy; pain and shortness of breath in the past 24 hours (response choices: none vs. mild, moderate, or severe). Psychosocial variables included depressed mood measured using the 2-item PRIME-MD (Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders) instrument;19 anxiety (question: “How would you describe your feelings of anxiety during the last 24 hours?” response choices: not anxious vs. mildly, moderately, or very anxious); instrumental support (question: “Could you use more help with daily tasks than you receive?” response choices: none vs. a little, some, or a lot); emotional support (question: “Could you use more emotional support than you receive?” response choices no vs. a little, some, or a lot); number of close family / friend interactions (question: “How many close friends or relatives do you see at least once a month?” response examined in quartiles); primary caregiver (response choices: spouse, child, or other); and five questions related to spirituality/religiosity (degree of religiosity, extent to which religion was a source of strength and comfort, whether participants had, as a result of their illness: a) grown closer to God, b) grown closer to church, and c) experienced spiritual growth.20 Health and psychosocial variables were obtained at each interview.

Data Analysis

We examined both the change in distribution of QoL ratings in the study cohort as a whole and among individual participants. To evaluate the former, we characterized the frequency of QoL ratings at baseline and at the final interview and compared the distribution of paired responses using Bowker’s test of symmetry. To evaluate the latter, we examined QoL ratings at each interview and characterized the frequency of four different trajectories of individuals’ responses. These trajectories were defined as: improving (QoL rating in at least one interview was higher than that at the previous interview and either improved or remained the same at each of the subsequent interviews); worsening (QoL rating in at least one interview was lower than that at the previous interview and either declined further or remained the same at each of the subsequent interviews); no change (QoL ratings at each time point were the same); variable (there were two or more changes in the direction of the trajectory over time; e.g. QoL improved then worsened or vice versa).

To evaluate QoL at the end of life, we examined two QoL outcomes according to whether the patient lived or died in bivariate analysis using the chi-square statistic. The first outcome was the QoL rating at the patient’s final interview. For this analysis, QoL responses were dichotomized as best possible/good versus fair/poor/worst possible.2, 10 The second outcome was the change in QoL from the penultimate to last interviews as described by three trajectories: improved, worsened, or no change.

To examine associations between health and psychosocial factors and QoL, as assessed at each interview, we used generalized linear mixed effects models. Variables associated with QoL over time in bivariate analysis with p < 0.10 were entered into a multivariable model. Time was included in the model regardless of significance. The correlation among variables measuring similar constructs was examined. When the correlation was > 0.3, the single variable that demonstrated the strongest association in bivariate analysis was entered into the model. All significance tests were two-sided and were regarded as statistically significant if they yielded a p-value < 0.05.

All statistical analysis was performed using SAS Version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Study Population

Table 1 provides a description of the 185 participants at the start of the study. In the previous year, 45% had been hospitalized ≥ 2 times and 34% had been admitted to an intensive care unit. Only 39% rated their health as excellent, very good, or good. In contrast to their poor health ratings, 65% of patients reported their QoL to be best possible or good. During the two year follow-up period, 95 participants (51%) died.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 185 Participants at Baseline

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Diagnosis: n (%) | |

| Cancer | 54 (29) |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | 74 (40) |

| Heart Failure | 57 (31) |

| Age, years (mean ± SD) | 73 ± 7 |

| ≥ High school education: n (%) | 120 (65) |

| White race: n (%) | 168 (91) |

| Female sex: n (%) | 85 (46) |

| Married: n (%) | 104 (56) |

| Self-rated health: excellent, very good, good: n (%) | 72 (39) |

| Depressed: n (%) | 89 (48) |

| Pain: n (%) | 89 (48) |

| Self-rated life expectancy: n (%) | |

| < 2 years | 22 (12) |

| ≥ 2 years | 87 (47) |

| Uncertain | 76 (41) |

| ≥ 2 hospitalizations in the past year: n (%) | 83 (45) |

| ≥ 1 activity of daily living disability: n (%) | 63 (34) |

| Intensive care unit admission in the past year: n (%) | 63 (34) |

| Quality of life: best possible or good: n (%) | 120 (65) |

Description of QoL Trajectories

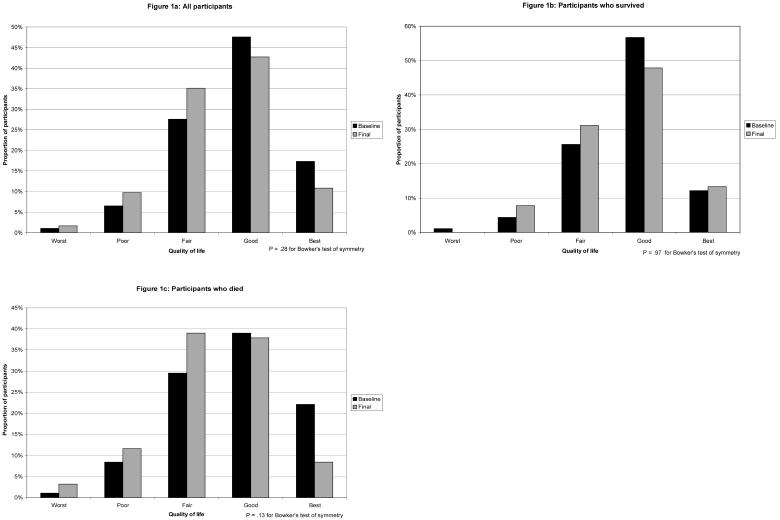

As shown in Figure 1a, at both the baseline and final interviews, a larger proportion of participants reported a best possible or good as compared to a worst possible, poor, or fair QoL. Participants’ responses were not significantly different at the final as compared to the baseline interview, although, as compared to baseline, fewer participants rated their QoL as best possible or good at the final interview, and more participants rated their QoL as fair, poor, or worst possible. .

Figure 1.

Distribution of QoL ratings at baseline interview (black bars) and final interview (gray bars). Figure 1a represents all participants, Figure 1b represents participants who survived, and Figure 1c represents participants who died.

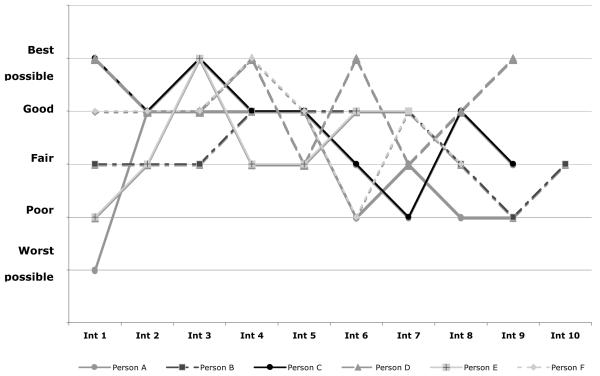

In contrast to the small change in ratings in the cohort overall from initial to final interview, there was great variability in ratings by individuals over time. While 22% of participants had an unchanging trajectory, 16% reported improving, and 13% reported worsening trajectories. Almost one-half (49%) of participants had variable trajectories. Figure 2 shows randomly selected examples of individual variable QoL trajectories. The variability in QoL ratings by individuals over time did not reflect small changes in response among a narrow range of ratings; rather ratings spanned the full range of response categories and could change by several categories from one interview to the next. Among the 91 participants with variable trajectories, 34 (37%) had a change of at least two categories from one interview to the next, and 48 (53%) had a difference of at least two categories between their lowest and highest QoL ratings.

Figure 2.

Examples of Individual QoL Trajectories Over Time

Characterization of QoL at the End of Life

The shift from higher toward lower QoL ratings from baseline to final interview was more pronounced among participants who died as compared to those who survived (Figures 1b and 1c). Although a larger proportion of the participants who died, as compared to those who survived, rated their QoL as fair, poor, or worst possible in their final interview (Table 2), almost one-half (46%) of those who died reported a best possible or good QoL. Twice as many participants (40%) who died reported a decline in their QoL from next to last to last interview as compared to those who survived (21%); however, approximately equal proportions of those who survived (19%) and who died (21%) reported an improved QoL.

Table 2.

Final QoL Of Participants Who Survived To The End Of The Study And Who Died During 2-Year Follow-Up Period

| Survived (n=90) |

Died (n=95) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | P-value | ||

| Rating at final interview best possible or good |

55 (61%) | 44 (46%) | 0.04 |

| Change in rating from penultimate to final interview: |

|||

| Improved | 17 (19%) | 20 (21%) | 0.008 |

| Worsened | 19 (21%) | 38 (40%) | |

| No change | 54 (60%) | 37 (39%) | |

Factors Associated With QoL

In bivariate analysis, participants with greater ADL disability, pain, depressed mood, anxiety, and self-rated life expectancy of less than 2 years were significantly more likely to report lower QoL (Table 3). Participants reporting excellent, very good or good self-rated health, sufficient instrumental support, greater number of close family/friend interactions, and having grown closer to their church were significantly more likely to have higher QoL. One additional measure of social support, sufficient emotional support, was significantly associated with higher QoL but was also correlated with the presence of sufficient instrument support. Three additional measures of greater religiosity--degree of religiosity, religion as a source of strength and comfort, and having grown spiritually --were significantly associated with higher QoL but were also correlated with having grown closer to church. Time was not associated with QoL ratings. Additional variables not associated with QoL in bivariate analysis included demographics (age, race, gender, education, sufficiency of monthly income, living arrangement, marital status), diagnosis, and relationship to primary caregiver.

Table 3.

Factors Associated with QoL Ratings Among 185 Participants in Bivariate & Multivariable Analysis

| Best possible/Good Quality of Life | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Bivariate | Multivariable | Multivariable* | |

| Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | |||

| Self-rated health excellent /very good /good |

6.07 (3.89, 9.46) | 4.79 (2.99, 7.69) | -- |

| Greater ADL disability | 0.73 (0.65, 0.82) | 0.85 (0.75, 0.95) | 0.79 (0.70, 0.89) |

| Depression | 0.27 (0.18, 0.40) | 0.42 (0.27, 0.66) | 0.38 (0.24, 0.58) |

| Grown closer to church as a result of illness |

2.45 (1.49, 4.03) | 1.99 (1.17, 3.39) | 2.09 (1.23, 3.55) |

| Has sufficient instrumental support | 2.21 (1.39, 3.52) | 1.32 (0.80, 2.18) | 1.63 (.99, 2.67) |

| Number of family/close friend interactions | 1.29 (1.06, 1.56) | 1.14 (0.92, 1.41) | 1.10 (.89, 1.36) |

| Moderate to severe pain | 0.56 (0.38, 0.82) | 0.77 (0.51, 1.17) | 0.76 (0.51, 1.14) |

| Moderate to severe anxiety | 0.62 (0.43, 0.91) | 0.95 (0.62, 1.44) | 0.92 (0.61, 1.39) |

| Moderate to severe shortness of breath | 0.68 (0.44, 1.07) | 1.14 (0.71, 1.85) | 1.05 (0.65, 1.69) |

| Self-rated life expectancy <2 yrs | 0.56 (0.33, 0.97) | 0.83 (0.47, 1.47) | 0.77 (0.43, 1.35) |

| Time | 0.98 (0.96, 1.01) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.02) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.03) |

Model excluded self-rated health (see text for further explanation)

In multivariable analysis, four variables remained statistically significant. Depressed mood was strongly associated with lower QoL ratings (adjusted odds ratio 0.42, 95% confidence interval 0.27, 0.66) (Table 3). Greater ADL disability was also significantly associated with lower QoL ratings while higher self-rated health and feeling closer to one’s religious community were significantly associated with higher QoL ratings. In order to examine whether self-rated health, a construct that encompasses a range of more specific measures of health,21 was accounting for the relationship between the social support and symptom variables and QoL, the multivariable model was rerun without self-rated health. None of the social support or physical symptom variables was significantly associated with QoL when self-rated health was excluded from the model, although the relationship between sufficiency of instrumental support and QoL became stronger and approached significance (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

In this study of community-dwelling older persons with advanced illness we used a subjective, global measure – “How would you rate your overall quality of life?” – to explore the longitudinal ratings of and to evaluate factors associated with QoL over a two-year period. Participant ratings illustrate that decline in QoL is not an inevitable consequence of advancing illness. Whereas QoL ratings in the population overall showed only a small shift toward worsening ratings from the beginning to the end of the study period, individual QoL trajectories were highly variable. Although the final QoL ratings of participants who died during follow-up were lower than those who survived to the end of the study, a substantial proportion of participants who died had preserved QoL. Greater ADL disability and depressed mood were associated with lower QoL while higher self-rated health and having grown closer to one’s church were associated with higher QoL.

Several prior studies have assessed subjective ratings of QoL among small selected cohorts of persons with advanced illness. Previous cross-sectional studies, conducted among patients receiving hospice services,22 and among patients with advanced cancer,23 have demonstrated preserved QoL despite impaired function and bothersome symptoms. Previous longitudinal studies, examining mean QoL ratings among study populations of hospice patients24 and patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis,25 have found relatively stable QoL ratings over time. The current study expands similar findings to a larger cohort of persons with a variety of advanced chronic illnesses studied over a longer period of time. The preservation of QoL despite advancing illness lends further empirical support for the phenomenon of response shift, or a change in individuals’ internal values, standards, or conceptualizations of QoL as health declines.26

By examining QoL trajectories among individual participants, the current study also demonstrates that small changes in QoL ratings on the population level mask highly variable individual QoL ratings over time. A similar pattern of individual variability in will to live has been described among older, terminally ill cancer patients in a palliative care setting.27 This variability suggests that subjective determinations of QoL may be influenced by temporary factors. Although temporary, these factors may play an important role in individuals’ valuations of their QoL, as elucidated in a prior study that asked persons with cancer to indicate the most important influences on their QoL over the last two days. These influences included good and bad news and weather, enjoying family and friends, and surprises. In addition, the influence of more traditional domains, such as symptoms and function, were described in terms of change; e.g.: pain or mobility being better or worse.4 Self-rated health, the single factor most strongly associated with QoL in the present study, has similarly been shown to be influenced by changes in affect and symptoms from the previous day.21 Taken together, these findings suggest that subjective QoL is an intrinsically unstable construct, affected by how the person is feeling and what they are experiencing now, in relationship to how they felt and what they experienced in the recent past.

In addition to self-rated health, depression, functional status, and religiosity, measured in terms of closeness to one’s church, were associated with QoL in a multivariable model. These factors are amenable to intervention, and these associations highlight the importance of maximizing function,28 addressing spiritual concerns,29 and treating depression30 among persons with advanced illness, even as they experience individual influences on their QoL.

The conceptualization of QoL as generally preserved despite worsening health but also variable among older persons with advanced illness has several implications for the care of these persons. First, preservation of QoL accounts in part for the persistence of preferences to receive invasive therapies with a risk of adverse outcomes in the face of advancing illness.31 The ability to adapt to worsening health status and recalibrate conceptions of QoL may in part be responsible for the difficulty many patients have in coming to terms with a shift in treatment goals away from life extension and toward comfort or other outcomes that are commonly referred to as focusing on “quality of life.”32 The variability in QoL ratings may also be responsible for inconsistencies in preferences. The same temporary factors associated with assessments of QoL may be associated with variability in patients’ willingness to undergo burdensome or risky therapies.33 Second, while understanding QoL as a highly personal and mutable construct supports the use of subjective global measures to assess QoL, it also raises questions about the utility of such measures as targets for intervention. To the extent that QoL is influenced by factors that are intrinsically unstable and/or cannot be externally influenced, it is an outcome that may not reflect the effects of interventions aimed at improving health or psychosocial status. Moreover, high QoL ratings in the face of symptom burden or psychosocial concerns demonstrate that patients can adapt to factors that are amenable to intervention22 and that patients with high QoL ratings may nonetheless have unmet health-related and psychosocial needs. Despite the limitations of global QoL measures, however, inquiries by clinicians about patients’ global QoL, if accompanied by questions designed to understand the factors affecting an individual’s assessment, may help to strengthen the clinician-patient relationship and help clinicians to understand patient preferences and decision making.

The study results are limited by a lack of ethnic and racial variability, which may affect their generalizability. Because of the relatively long time period between final interviews and death among participants who died, there may have been further changes in QoL that were not captured in the study. Because the study examined QoL among patients with advanced illness, missing data are unavoidable. The largest cause of missing data in the study was mortality. It is unclear if these data are missing in the sense that this term is frequently used because these data, along with the data from participants who became cognitively impaired or more severely ill, are not recoverable.34 However, there were also missing data from participants who dropped out of the study for other reasons or who failed to consent to a second year of participation and, therefore, we cannot know whether these missing data introduce bias into the results. We elected to examine factors associated with QoL as a dichotomous variable because of the limitations in alternative approaches. The response categories could not appropriately be considered as ordinal, given the potential for uneven intervals between them. Although the cut-point we used to create the two levels of QoL is a plausible one, distinguishing between QoL rated as good or better versus less than good, and has been used previously, it must be recognized that it was nonetheless a somewhat arbitrary decision, and our results may have been different if we had chosen a different cut-point.

While demonstrating that decline in QoL was not an inevitable consequence of advancing illness, this study also illustrates the highly variable nature of subjectively assessed QoL. Although a subjective measure may provide the most accurate assessment of self-perceived QoL, a more directed survey of modifiable factors may prove more helpful to clinicians wishing to identify potential points of intervention for persons with advanced disease.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Supported by: Summer Training in Aging Research Topics – Mental Health (START-MH, a program of the NIMH), P30 AG21342 from the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center at Yale University and R01 AG19769 from the National Institute on Aging. Dr Fried is supported by grant K24 AGAG028443 from the National Institute on Aging.

Sponsors’ role: The sponsors had no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collection, or analysis and preparation of the paper.

Footnotes

Presented at the 2007 annual meeting of the American Geriatrics Society.

Conflict of interest:

| Elements of Financial/Personal Conflicts |

RS | PK | PHVN | JO’L | TRF | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Employment or Affiliation | x | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Grants/Funds | x | x | X | X | x | |||||

| Honoraria | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Speaker Forum | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Consultant | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Stocks | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Royalties | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Expert Testimony | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Board Member | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Patents | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Personal Relationship | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

REFERENCES

- 1.Hickey A, Barker M, McGee H, et al. Measuring health-related quality of life in older patient populations: a review of current approaches. Pharmacoeconomics. 2005;23:971–93. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200523100-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Somogyi-Zalud E, Zhong Z, Lynn J, et al. Elderly persons’ last six months of life: findings from the Hospitalized Elderly Longitudinal Project. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:S131–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albrecht GL, Devlieger PJ. The disability paradox: high quality of life against all odds. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48:977–88. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00411-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen SR, Mount BM. Living with cancer: “good” days and “bad” days--what produces them? Can the McGill quality of life questionnaire distinguish between them? Cancer. 2000;89:1854–65. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001015)89:8<1854::aid-cncr28>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farquhar M. Elderly people’s definitions of quality of life. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41:1439–46. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00117-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lawton MP. A multidimensional view of quality of life in frail elders. In: Birren J, Lubben J, Rowe J, Detchman D, editors. The Concept and Measurement of Quality of Life in the Frail Elderly. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 1991. pp. 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowling A, Gabriel Z, Dykes J, et al. Let’s ask them: a national survey of definitions of quality of life and its enhancement among people aged 65 and over. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2003;56:269–306. doi: 10.2190/BF8G-5J8L-YTRF-6404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Netuveli G, Blane D. Quality of life in older ages. Br Med Bull. 2008;85:113–26. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldn003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gill TM, Feinstein AR. A critical appraisal of the quality of quality-of-life measurements.[see comment] JAMA. 1994;272:619–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Covinsky KE, Wu AW, Landefeld CS, et al. Health status versus quality of life in older patients: does the distinction matter? Am J Med. 1999;106:435–40. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Connecticut Hospice Inc. Summary Guidelines for Initiation of Advanced Care. John Thompson Institute; Branford, CT: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murphy DJ, Knaus WA, Lynn J. Study population in SUPPORT: patients (as defined by disease categories and mortality projections), surrogates, and physicians. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43:11S–28S. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(90)90213-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pfeiffer E. A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1975;23:433–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1975.tb00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Royall DR, Mahurin RK, Gray KF. Bedside assessment of executive cognitive impairment: the executive interview. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1992;40:1221–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb03646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, et al. Studies of illness in the aged: the index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185:914–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pearlin LI, Lieberman MA, Menaghan EG, et al. The stress process. J Health Soc Behav. 1981;22:337–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Idler EL, Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav. 1997;38:21–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whooley MA, Avins AL, Miranda J, et al. Case-finding instruments for depression. Two questions are as good as many. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:439–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00076.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pargament KI, Ensing DS, Falgout K, et al. God help me: I. Religious coping efforts as predictors of the outcomes to significant negative life events. Am J Community Psychol. 1990;18:793–824. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Winter L, Lawton MP, Langston CA, et al. Symptoms, affects, and self-rated health: evidence for a subjective trajectory of health. J Aging Health. 2007;19:453–69. doi: 10.1177/0898264307300167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kutner JS, Nowels DE, Kassner CT, et al. Confirmation of the “disability paradox” among hospice patients: preservation of quality of life despite physical ailments and psychosocial concerns. Palliative & Supportive Care. 2003;1:231–7. doi: 10.1017/s1478951503030281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waldron D, O’Boyle CA, Kearney M, et al. Quality-of-life measurement in advanced cancer: assessing the individual. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:3603–11. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.11.3603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bretscher M, Rummans T, Sloan J, et al. Quality of life in hospice patients. A pilot study. Psychosomatics. 1999;40:309–13. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(99)71224-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robbins RA, Simmons Z, Bremer BA, et al. Quality of life in ALS is maintained as physical function declines. Neurology. 2001;56:442–4. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.4.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sprangers MAG, Schwartz CE. Integrating response shift into health-related quality of life research: a theoretical model. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48:1507. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chochinov HM, Tataryn D, Clinch JJ, et al. Will to live in the terminally ill. Lancet. 1999;354:816–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)80011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reuben DB. Principles of Geriatric Assessment. In: Hazzard WR, Blass JP, Halter JB, Ouslander JG, Tinetti ME, editors. Principles of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology. McGraw-Hill; New York: 2003. pp. 99–110. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Balboni TA, Vanderwerker LC, Block SD, et al. Religiousness and spiritual support among advanced cancer patients and associations with end-of-life treatment preferences and quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:555–60. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Block SD. Assessing and managing depression in the terminally ill patient. ACP-ASIM End-of-Life Care Consensus Panel. American College of Physicians - American Society of Internal Medicine. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:209–18. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-3-200002010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fried TR, Van Ness PH, Byers AL, et al. Changes in preferences for life-sustaining treatment among older persons with advanced illness. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:495–501. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0104-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Finucane TE. How gravely ill becomes dying: a key to end-of-life care. JAMA. 1999;282:1670–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.17.1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fried TR, O’Leary J, Van Ness P, et al. Inconsistency over time in the preferences of older persons with advanced illness for life-sustaining treatment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:1007–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01232.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. 2nd edition John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ: 2002. [Google Scholar]