SYNOPSIS

Objectives

We examined changes in relative disparities between racial/ethnic populations for the five leading causes of death in the United States from 1990 to 2006.

Methods

The study was based on age-adjusted death rates for four racial/ethnic populations from 1990–1998 and 1999–2006. We compared the percent change in death rates over time between racial/ethnic populations to assess changes in relative differences. We also computed an index of disparity to assess changes in disparities relative to the most favorable group rate.

Results

Except for stroke deaths from 1990 to 1998, relative disparities among racial/ethnic populations did not decline between 1990 and 2006. Disparities among racial/ethnic populations increased for heart disease deaths from 1999 to 2006, for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease deaths from 1990 to 1998, and for chronic lower respiratory disease deaths from 1999 to 2006.

Conclusions

Deaths rates for the leading causes of death are generally declining; however, relative differences between racial/ethnic groups are not declining. The lack of reduction in relative differences indicates that little progress is being made toward the elimination of racial/ethnic disparities.

Reducing racial/ethnic disparities in health has been a part of the national health promotion agenda since 1980. The first Healthy People (HP) initiative, Objectives for the Nation, included several objectives to reduce racial/ethnic disparities.1 In 1985, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) released the Report of the Secretary's Task Force on Black and Minority Health, otherwise known as the Heckler Report.2 That report focused attention on excess deaths among black and other racial/ethnic subgroups. The report made eight wide-ranging recommendations to improve the health of minority populations. In 1990, HHS adopted “reducing health disparities among Americans” as one of three overarching goals of the HP objectives for the year 2000.3 In 1999, eliminating disparities became one of two overarching goals of the HP 2010 objectives,4 and Congress directed the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality to produce an annual National Healthcare Disparities Report (NHDR) starting in 2003.5

The HP 2000 initiative targeted greater proportional improvements for special populations relative to improvements for the total population.3 The HP 2010 initiative requires reductions in relative differences as evidence of progress toward eliminating disparities,6 and the NHDR employs relative differences to assess changes in disparity.7 According to the HP 2010 Midcourse Review, there was no change in racial/ethnic disparities for 81% of the 195 objectives with the data required to assess changes in disparities. Racial/ethnic disparities decreased for 24 objectives but increased for 14 objectives.6 Based on 21 indicators of health-care quality and access in the NHDR, disparities for black, Asian, and Hispanic populations were not decreasing for more than 60% of the indicators.8

This article examines changes in death rates for the five leading causes of death (CODs) in the overall U.S. population by race/ethnicity. The relative change in rates is used to evaluate the change in disparities between 1990 and 2006.

METHODS

The five leading CODs in 2006 for the overall population were, in order of rank: diseases of the heart (heart disease), malignant neoplasms (cancer), cerebrovascular diseases (stroke), chronic lower respiratory diseases (formerly chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases and allied conditions), and accidents (unintentional injuries).10 We measured disparities in these causes for four racial/ethnic populations: Asian or Pacific Islander (API), black or African American, Hispanic or Latino, and non-Hispanic white (NHW). The five leading CODs for the NHW population were the same as the five leading causes for the total population, though not in the same order. Chronic lower respiratory disease was the sixth leading COD for the API population and the eighth for the black and Hispanic populations. Diabetes mellitus was the fifth leading COD for these three populations.

Data

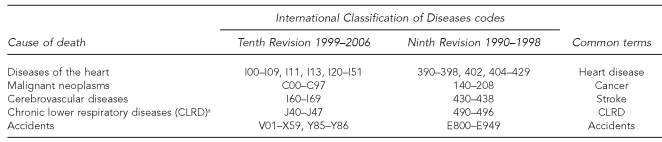

We analyzed data from the National Vital Statistics System, which includes information from all death certificates filed in the 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia. The leading CODs are based on the underlying COD, the disease or injury that initiated the train of events leading directly to death.9 CODs are ranked according to number of deaths. Rankings are based on a specific subset of all CODs.10 From 1990 to 1998, CODs were coded according to the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9); beginning in 1999, CODs were coded according to the ICD Tenth Revision (ICD-10). The five leading CODs—heart disease, cancer, stroke, chronic lower respiratory diseases, and accidents—have been the leading CODs for the U.S. population for the entire period studied in this article. We present the respective ICD-10 codes in Figure 1, along with the common terms for these CODs. Changes in the classification of diseases and new coding rules for selecting the underlying COD affect the comparability of COD coding.11 Therefore, we examined two distinct periods, 1990–1998 and 1999–2006. All rates were age-adjusted to the year 2000 standard population to compare rates among racial/ethnic groups with different age distributions.12

Figure 1.

The five leading causes of death in the United States in 2006 and their classification codes

aFormerly classified as chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases in the Ninth Revision

Throughout the periods studied, race was classified according to standards issued by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) in 1977: white, black, API, and American Indian or Alaska Native (AI/AN).13 Beginning in 2003, some states began reporting multiple-race data for decedents and distinguishing Asian from Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander decedents in compliance with revised standards issued by OMB in 1997.14 Because not all states have completed the transition to the new standards on their death certificates, multiple-race data have been bridged back to the 1977 racial categories.15,16 Information about Hispanic origin is collected independently from race. Although people identified as Hispanic can be of any race, they comprise very small proportions of races other than white. In this article, death rates are presented separately for the Hispanic and NHW populations. The categories API and black include small numbers of people reported to be of Hispanic origin; therefore, these three categories are not mutually exclusive.

A recent study compared self-reported race/ethnicity in the Current Population Survey (CPS) with race/ethnicity subsequently reported on death certificates for the same individuals between 1990 and 1998.17 Agreement was nearly perfect for the white and black populations. However, as a result of misclassification of race/ethnicity on death certificates, for the years 1999–2001, the total age-adjusted death rate was underestimated for the AI/AN population by 31%, for the API population by 6%, and for the Hispanic population by 5%. The effect of misclassification on death rates for the period 1999–2006 is unknown; however, misclassification declined for the API population between 1979–1989 and 1990–1998. Because of the high level of underestimation of age-adjusted death rates for the AI/AN population, we excluded data for this population from this analysis of racial/ethnic disparities.

Measures of disparity

Disparities can be measured in absolute or relative terms at a point in time, or as change over time. However, conclusions about changes in disparities depend on whether differences are measured in absolute or relative terms.18 The absolute difference is obtained by subtracting the rate for a reference population from the rate for the other populations. The relative difference is obtained by dividing the absolute difference by the rate for the reference population; the result is expressed as a percentage of the rate for the reference population.

While both absolute and relative differences can be used to assess change in disparities over time, the choice of measure is important because absolute and relative measures of disparity can lead to different conclusions about the size and direction of changes in disparities over time. When rates are declining, a reduction in the absolute difference between group rates can occur without a reduction in the relative difference. Therefore, in this study, we measured disparities according to the principles adopted in HP 2010.6,19 Specifically, we used the most favorable age-adjusted cause-specific death rate as a reference point, and we measured disparities in terms of relative differences (i.e., percentage differences) from the most favorable rate. The percent difference is calculated between the most favorable racial/ethnic group rate and each of the other racial/ethnic group rates. When the relative difference from the most favorable group rate declines, this shows that the rate for the other group is improving faster than the rate for the group with the most favorable rate, thereby representing progress toward the elimination of the disparity.

We computed an index of disparity among racial/ethnic groups by taking the mean of the percentage differences from the most favorable group rate. With four racial/ethnic group rates, the mean is based on three differences from the most favorable group rate. We assessed changes in disparities among the four racial/ethnic groups in terms of absolute changes in the index of disparity. We computed standard errors for the index using a bootstrap procedure based on the underlying age-adjusted rates and their standard errors.20 We also assessed changes in disparities by comparing changes over time in group-specific rates. If, for example, the rate for a population with a less favorable rate declines by a greater proportion than the most favorable population rate, the relative disparity will decrease. On the other hand, if the most favorable population rate declines by a greater proportion than the rate for a population with a less favorable rate, the relative disparity will increase. We tested absolute changes in the index of disparity and in age-adjusted death rates for statistical significance at the p<0.05 level, with no adjustment for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

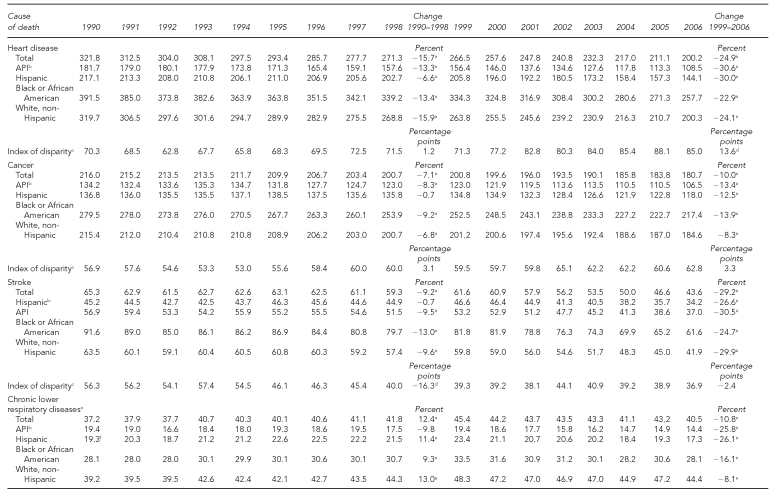

We present age-adjusted death rates by race and Hispanic origin for the five leading CODs in the U.S. from 1990 to 2006 in the Table. Two distinct intervals—1990–1998 and 1999–2006—are shown because of the change in rules for classifying CODs from ICD-9 to ICD-10. Death rates declined during the entire period for deaths due to heart disease, cancer, and stroke. Death rates due to chronic lower respiratory disease were higher from 1999 to 2006 than rates for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease from 1990 to 1998. The age-adjusted death rate for accidents was almost unchanged during the earlier period, and then increased by 13% between 1999 and 2006.

Table.

Age-adjusted death rates (per 100,000 standard population) for the five leading causes of death, by race and Hispanic origin: U.S., 1990–2006

Source: National Vital Statistics System: Mortality. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics (US).

aThe absolute change in the age-adjusted death rate is statistically significant at p<0.05.

bThe racial/ethnic population with the most favorable rate from 1990 to 2006

cThe index of disparity is the mean of the percent differences between the most favorable population rate and the other population rates.

dThe absolute (percentage point) change in the index of disparity is statistically significant at p<0.05.

eThe classification category in the Ninth Revision of the International Classification of Diseases for the years 1990–1998 was chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

fThe Hispanic population had the most favorable rate in 1990 and is used as the reference point for computing the index of disparity in that year.

API = Asian or Pacific Islander

Heart disease

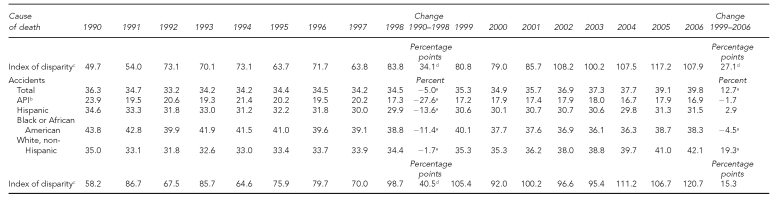

Between 1990 and 1998, the age-adjusted death rate for heart disease (the leading COD for the total population) declined for all four racial/ethnic groups (Figure 2). Reductions ranged from 7% for the Hispanic population to 16% for the NHW population (Table). Between 1999 and 2006, heart disease death rates continued to decline by 23% or more for all four populations. The API population had the most favorable age-adjusted heart disease death rate during both periods. Except for the Hispanic population during the period 1990–1998, absolute differences between the most favorable group rate and the rates for the other groups tended to decline from 1990 to 2006. Reductions in absolute differences over time are reflected in a narrowing of the differences between trend lines in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Age-adjusted heart disease death rates by race/ethnicity: U.S., 1990–2006

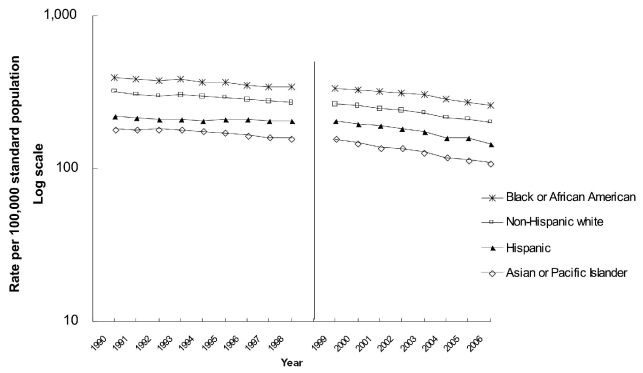

However, an examination of relative differences shows a contrasting pattern of change over time. In Figure 3, the same age-adjusted heart disease death rates are plotted with a log scale on the vertical axis. The vertical distance between trend lines is indicative of the relative difference between population rates at each point in time. From 1990 to 1998, the rate for the API population declined by 13% and the rate for the Hispanic population declined by 7%. The relative difference between the two groups, therefore, increased. The vertical distance between the rates for the Hispanic and API populations was greater in 1998 than in 1990. The heart disease death rate for the black and NHW populations declined by 13% and 16%, respectively. Because the rates for these two populations declined by about the same percentage as the decline in the reference population, relative differences remained similar. There was no significant change in the index of disparity.

Figure 3.

Age-adjusted heart disease death rates by race/ethnicity: U.S., 1990–2006a

aWhen plotted on a log scale, vertical distances between rates at each point in time are indicative of relative differences.

Between 1999 and 2006, the rate for the reference group (API) declined by about the same percentage as the rate for the Hispanic group. The relative difference between the two groups, therefore, remained about the same. By contrast, rates for the black and NHW groups declined by smaller percentages, so relative differences from the best group rate increased. These changes are reflected by increases in the vertical distance between the rate for the reference group and the rates for the black and NHW groups in Figure 3. The increase in relative differences from the most favorable group rate is also reflected by the increase in the index of disparity, from 71% in 1999 to 85% in 2006 (Table). We focused on relative differences for the remaining CODs.

Cancer

All cancers combined are the second leading COD. The API population also had the most favorable age-adjusted cancer death rate from 1990 to 2006. The rate for this population declined by 8% between 1990 and 1998 (Table). The rates for the black and NHW populations declined by similar percentages. The rate for the Hispanic population was almost unchanged during this period; therefore, the relative difference from the most favorable group rate increased. The index of disparity increased from 57% in 1990 to 60% in 1998; however, this increase was not statistically significant.

Between 1999 and 2006, the age-adjusted cancer death rate declined by 13% for the API population and by 8% to 14% for the other three populations. Because rates improved by similar proportions, there was little change in the relative difference between each of the other racial/ethnic groups and the most favorable group rate, and there was no significant change in the index of disparity.

Stroke

From 1990 to 2006, the Hispanic population had the most favorable stroke death rate. Between 1990 and 1998, the rate for the Hispanic population changed very little. Stroke death rates declined by 9% to 13% for the other three populations (Table). Relative differences from the most favorable rate, therefore, declined, and the index of disparity decreased from 56% in 1990 to 40% in 1998. Between 1999 and 2006, stroke death rates declined by similar percentages for the four racial/ethnic groups; consequently, there was no significant change in the index of disparity.

Chronic lower respiratory disease

Between 1990 and 1998, the API population had the most favorable rate in each year except 1990, when the Hispanic population had the most favorable rate. There was no significant change in the chronic obstructive pulmonary disease death rate for the API population. The rates for the black, Hispanic, and NHW populations increased. Consequently, the index of disparity increased substantially from 50% in 1990 to 84% in 1998 (Table).

From 1999 to 2006, chronic lower respiratory disease death rates declined by 26% for the API and Hispanic populations. Rates declined by smaller percentages for the other racial/ethnic populations: by 16% for the black population and 8% for the NHW population. Greater reduction in rates for the reference group relative to the two latter groups was associated with an increase in the index of disparity, from 81% in 1999 to 108% in 2006.

Accidents

The API population had the most favorable accident death rate from 1990 to 2006. In 1998, the rate for this population was 28% lower than the rate in 1990. However, the rate for 1990 appears to be unusually high (Table). Based on the years 1991–1998, there was little change in the accident death rate for the API population. Accident death rates for the Hispanic and black populations declined by more than 10%, and the rate for the NHW population declined by less than 2%. The index of disparity increased and decreased from one year to the next, with no definitive trend despite the fact that the increase between 1990 and 1998 was statistically significant.

Between 1999 and 2006, there was little change in accident death rates for the API and Hispanic populations, and a small decrease in rates for the black population. However, the accident death rate for the NHW population increased by 19%, from 35 deaths per 100,000 population in 1999 to 42 deaths per 100,000 population in 2006. This increase in disparity relative to the best group rate was associated with a non-significant increase in the index of disparity between 1999 and 2006.

DISCUSSION

For the five leading CODs, aggregate disparity generally increased or remained unchanged during 1990–1998 and 1999–2006. Only stroke between 1990 and 1998 had a significant decline in disparity. These trends in disparity occurred even though substantial declines in cause-specific mortality rates were observed for most racial/ethnic groups.

Racial/ethnic disparities in heart disease death rates were unchanged between 1990 and 1998, then increased between 1999 and 2006. Disparities in cancer death rates were unchanged during both intervals. Racial/ethnic disparities in stroke death rates decreased between 1990 and 1998 and then remained constant during 1999–2006. Disparities in chronic lower respiratory disease death rates increased during both intervals. Disparities in accident death rates fluctuated without a discernable trend. Except for stroke deaths during 1990–1998, there was no consistent evidence of reductions in relative disparities among these racial/ethnic populations for the five leading CODs.

An observer looking at Figure 2 might well conclude that progress is being made toward the elimination of racial/ethnic disparities in heart disease death rates. Heart disease death rates for the four racial/ethnic populations are declining, absolute differences from the most favorable population rate are generally declining, and the gaps between rates for the four racial/ethnic populations are narrowing. However, reductions in relative differences are required as evidence of progress toward eliminating disparities in HP 2010. Rates can improve and absolute differences can decline without any reduction in relative disparities.21

Changes in relative differences are shown in Figure 3, where the vertical axis is on a log scale. Relative differences from the most favorable group rate are not declining. Between 1990 and 1998, the relative difference from the most favorable group rate increased for the Hispanic population. Between 1999 and 2006, relative differences in heart disease death rates increased for the black and NHW populations. There has been no progress toward eliminating racial/ethnic disparities in heart disease deaths.

When changes in disparity are assessed relative to the most favorable group rate, changes in the most favorable group rate itself can have a substantial effect on the index of disparity. Between 1990 and 1998, the stroke death rate for the Hispanic population was essentially unchanged. Reductions in the rates for the other three populations resulted in a decrease in the index. Greater reductions in the reference group rate for heart disease deaths between 1999 and 2006, for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease deaths between 1990 and 1998, and for chronic lower respiratory disease deaths between 1999 and 2006 also contributed to increases in the index of disparity. However, in these instances relative differences between each pair of racial/ethnic population rates either remained the same or increased. Increases in the index of disparity were not solely the result of greater improvements in the most favorable group rate.

The API population had the most favorable age-adjusted rates for heart disease, cancer, chronic lower respiratory disease, and accident deaths, and the Hispanic population had the most favorable age-adjusted stroke death rates. As noted previously, for the period 1999–2001, it is estimated that age-adjusted death rates for the API population were understated by 6%, and the rates for the Hispanic population were understated by 5%.17 If rates for the API and Hispanic populations, as reference groups, were increased accordingly, the magnitude of the index of disparity would be reduced; however, disparities would not be eliminated and conclusions about changes in relative disparities over time would not be affected. It is unlikely that systematic changes in racial/ethnic misclassification account for the persistence of the racial/ethnic disparities observed in this study.

CONCLUSIONS

We examined trends in age-adjusted death rates for the five leading CODs in the U.S. Age-adjusted death rates for four of the five leading CODs generally declined, with reductions for each of four racial/ethnic populations. Despite significant reductions in rates, relative disparities have not been reduced. Since 1999, the overall accident death rate increased, due largely to an increase in the rate for the NHW population, without any significant change in the racial/ethnic disparity. Despite continuing reductions in rates for specific racial/ethnic populations, there is very little evidence of reductions in relative disparities between these populations.

Examination of trends for more specific CODs might lead to different conclusions. When specific cancers are examined, for example, both increases and decreases in relative disparities are evident for particular racial/ethnic groups.6 Similarly, when data are disaggregated into smaller geographic units (e.g., Chicago), both increases and decreases in disparity are evident.22 In the current analysis, as in Chicago, increases in disparity are more common than decreases in disparity. Without reductions in relative differences, there is no progress toward eliminating racial/ethnic disparities. To eliminate disparities in the leading CODs, populations with less favorable death rates must improve by greater proportions than populations with more favorable rates. These results indicate that reductions in racial/ethnic disparities do not necessarily occur when death rates decline.

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

REFERENCES

- 1.Department of Health and Human Services (US) Promoting health/preventing disease: objectives for the nation. Washington: Public Health Service (US); 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Department of Health and Human Services (US) Report of the Secretary's Task Force on black and minority health. Washington: HHS; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Health and Human Services (US) Healthy People 2000: national health promotion and disease prevention objectives. Washington: HHS, Public Health Service (US); 1991. DHHS publication no. (PHS) no. 91-50212. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Department of Health and Human Services (US) Healthy People 2010: understanding and improving health. 2nd ed. Washington: HHS; 2000. [cited 2009 Apr 20]. Also available from: URL: http://www.healthypeople.gov/publications. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Healthcare Research and Quality Act of 1999. Public Law 106-129. 1999. Dec,

- 6.Department of Health and Human Services (US) Healthy People 2010 midcourse review. Washington: Government Printing Office (US); 2006. [cited 2009 Apr 20]. Also available from: URL: http://www.healthypeople.gov/data/midcourse/default.htm#pubs. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US) National healthcare disparities report, 2005. Rockville (MD): AHRQ; 2005. [cited 2009 Apr 22]. AHRQ Pub. No. 06-0017. Also available from: URL: http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/Nhdr05/nhdr05.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US) 2007 national healthcare disparities report. Rockville (MD): AHRQ; 2008. [cited 2009 Apr 20]. AHRQ Pub. No. 08-0041. Also available from: URL: http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/qrdr07.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heron M, Hoyert DL, Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD, Tejada-Vera B. Deaths: final data for 2006. [cited 2009 Apr 27];Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2009 Apr 17;57:1–134. Also available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr57/nvsr57_14.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heron M. Deaths: leading causes for 2006. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2010 Mar 31;58:1–100. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson RN, Miniño AM, Hoyert DL, Rosenberg HM. Comparability of cause of death between ICD-9 and ICD-10: preliminary estimates. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2001 May 18;49:1–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson RN, Rosenberg HM. Age standardization of death rates: implementation of the year 2000 standard. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 1998 Oct 7;47:1–16. 20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Census Bureau (US) Race and ethnic standards for federal statistics and administrative reporting. Statistical Policy Directive 15. Washington: Office of Management and Budget (US); 1977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Office of Management and Budget (US) Revisions to the standards for the classification of federal data on race and ethnicity. [cited 2009 May 14];Federal Register 62. 1997 Oct 30;58:781–90. Also available from: URL: http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/fedreg_1997standards. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ingram D, Weed J, Parker J, Hamilton B, Schenker N, Arias E, et al. U.S. Census 2000 population with bridged race categories. Vital Health Stat 2. 2003;(135) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schenker N, Parker JD. From single-race reporting to multiple-race reporting: using imputation methods to bridge the transition. Stat Med. 2003;22:1571–87. doi: 10.1002/sim.1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arias E, Schauman WS, Eschbach K, Sorlie PD, Backlund E. The validity of race and Hispanic origin reporting on death certificates in the United States. Vital Health Stat 2. 2008;(148) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keppel KG, Pearcy JN, Klein RJ. Measuring progress in Healthy People 2010. Statistical Notes. 2004;25:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anand S, Diderichsen F, Evans T, Shkolnikov VM, Wirth M. Measuring disparities in health: methods and indicators. In: Evans T, Whitehead M, Diderichsen F, Bhuiya A, Wirth M, editors. Challenging inequalities in health: from ethics to action. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. pp. 48–67. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keppel KG, Pearcy JN, Wagener DK. Trends in racial and ethnic-specific rates for the health status indicators: United States, 1990–98. Statistical Notes. 2002;23:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keppel K, Garcia T, Hallquist S, Ryskulova A, Agress L. Comparing racial and ethnic populations based on Healthy People 2010 objectives. Healthy People Stat Notes. 2008;26:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Margellos H, Silva A, Whitman S. Comparison of health status indicators in Chicago: are black-white disparities worsening? Am J Public Health. 2004;94:116–21. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.1.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]