Cancer is the second-leading cause of death among Hispanic people in the United States and accounts for roughly 20% of all deaths in the U.S. In 2006, breast cancer remained the leading cause of new cancer cases and cancer deaths among Hispanic women. However, the incidence of breast cancer among Hispanic women was roughly 40% lower than the incidence among non-Hispanic white women. Explanations for this trend include variations in reproductive patterns and lower use of hormone replacement therapy, as well as underdiagnosis due to lower rates of mammography.1

While incidence rates are lower, Hispanic women are less likely than non-Hispanic white women to be diagnosed at the local stage of disease (54% vs. 63% of cases, respectively) and 20% more likely to die of breast cancer than non-Hispanic white women even at the same age and stage of diagnosis.1 In 2005, 58.8% of Hispanic women aged 40 years and older had a mammogram within the last two years compared with 68.4% of non-Hispanic white women.2 Both lower rates of mammography screening and delay in follow-up for abnormal results may contribute to the higher rates of breast cancer deaths among Hispanic women. A multitude of socioeconomic factors may influence these rates as well, including lower levels of education, higher rates of poverty, inadequate or no health insurance, and lack of transportation. These factors are compounded by cultural and linguistic barriers.1

Community-based initiatives to provide culturally appropriate mobile mammography services may hold promise in reducing screening disparities among Hispanic/Latina women. This article reports findings of a community-academic partnership to conduct a pilot project providing mobile mammography services in the majority Latino city of Lawrence, Massachusetts. The project was a collaboration of the YWCA of Greater Lawrence, the Lawrence Mayor's Health Task Force (MHTF), Boston's Mammography Van (BMV)—operated by the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI) in partnership with the City of Boston—and the Harvard School of Public Health (HSPH). It was conducted as part of a community-based participatory research network called MassCONECT (Massachusetts Community Networks to Eliminate Cancer Disparities through Education, Research and Training), which is funded by the National Cancer Institute.

MOBILE MAMMOGRAPHY

Prior studies on implementing mobile mammography services have focused on financial barriers, such as costs exceeding running expenses3–5 and logistical challenges (e.g., high loss to follow-up of women with abnormal mammograms after van screening).6 At the same time, there is evidence of higher receptivity to use of mobile mammography among Hispanic/Latina women.7,8 A study conducted in Los Angeles found that Spanish-speaking Latinas, uninsured women, and those who reported no mammogram in the previous 24 months were more receptive to the use of mobile mammography than were white women, insured women, and women who reported a previous mammogram. In fact, 93% of Spanish-speaking Latinas said they would probably or definitely use mobile mammography services compared with 33% of English-speaking white women.7

Identifying effective ways to increase mammography screening rates among Latinas is important to improving their breast cancer outcomes, and mobile mammography may play a role in increasing access to screening. Combined with strong outreach and involvement of trusted community-based organizations, such programs may be effective in reaching the Latina women who are most in need. This analysis presents an example of a community-based program that combined mobile mammography and community outreach to provide mammography screening to medically underserved and low socioeconomic status (SES) women.

PROJECT PLANNING AND IMPLEMENTATION

Community background

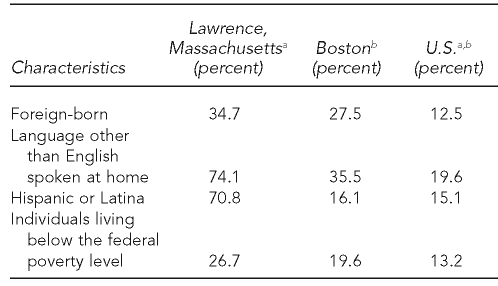

The setting for the pilot project was Lawrence, Massachusetts, a city with a total population of 71,234 according to the 2006–2008 American Community Survey.9 Lawrence is characterized demographically by majority Hispanic ethnicity, majority non-English speakers, and disproportionately low income and high poverty (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of residents in Lawrence, Massachusetts; Boston; and the U.S.: 2006–2008

aCensus Bureau (US). 2006–2008 American Community Survey. 3-year estimates, fact sheet, Lawrence, Massachusetts. Washington: Census Bureau; 2010.

bCensus Bureau (US). 2006–2008 American Community Survey. 3-year estimates, fact sheet, Boston, Massachusetts. Washington: Census Bureau; 2010.

Building relationships among stakeholder organizations

The MHTF played an integral role in facilitating a connection and eventual collaboration among the multiple organizations involved in the BMV pilot project. In December 2006, the MassCONECT Working Group (“Working Group”), a subgroup of organizations within the MHTF, was approached about potentially hosting the BMV. The impetus for the BMV approaching the Working Group was a financial donation to DFCI designated for use in Lawrence. After an initial meeting between the BMV Program Director and the Working Group, local and state public health providers, national and local nonprofit organizations, area hospitals, and a federally qualified health center came together to plan and subsequently implement the “van days,” or the BMV pilot project.

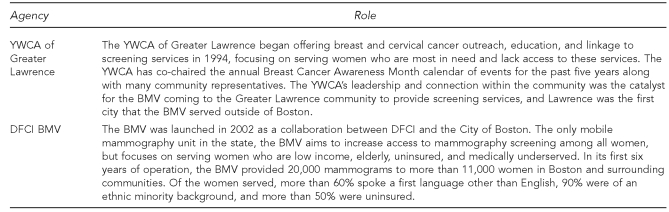

At a subsequent MHTF meeting, the YWCA was chosen unanimously to act as the lead community agency for the BMV pilot project. This selection was based on the YWCA's previous experience with mobile mammography services and its history of outreach, education, and linkage in the greater Lawrence community. The BMV and YWCA developed and signed a written contract to clarify the goals of the collaboration and each agency's respective roles vis-à-vis the planning and implementation of van days (Figure).

Figure.

Roles of key agencies in the 2007–2008 mobile mammography pilot in Lawrence, Massachusetts

BMV = Boston's Mammography Van

DFCI = Dana-Farber Cancer Institute

Although the BMV was centered in Boston, it was well positioned to use its experience to increase mammography screening among low SES and medically underserved women of Lawrence (28 miles north of Boston). Because the BMV program had not worked in the Lawrence area prior to this collaboration, it had not established rapport, trust, or credibility with the community. This made the role of the YWCA vital to the recruitment of eligible patients and the success of the screening days. As the lead community agency, the YWCA staff also served to bridge any cultural, ethnic, or linguistic barriers between patients and the mammography van staff.

Project planning and coordination

Once organizational involvement and roles were established, the emphasis on developing a community-based, culturally appropriate screening project began. The goal of this project was to identify and serve the hardest-to-reach women; therefore, YWCA staff recommended that the van days be hosted on Saturdays. The staff knew that many of the women who needed screening were unable to attend a mammogram appointment on weekdays due to work conflicts, and they felt that hosting the van on Saturdays would also rule out any risk of duplicating services already available within the community.

It was decided that the project would host five screening days at three different sites in the first year: one at the Lawrence Senior Center, one at the International Institute of Greater Lawrence, Inc., and three at the YWCA. Planning staff from the YWCA and BMV were in constant communication with staff from these two additional agencies to discuss the logistics, recruitment, and marketing efforts for the van days. The initial donation to fund the pilot project was supplemented with an additional $10,000 grant to cover screening costs for uninsured women as well as promotional media for the project.

The staff of the BMV maintained close contact with the YWCA staff in the two months prior to each van day; they provided technical assistance to the YWCA staff in their logistical and technical efforts and retrieved patients' mammography films (when they existed) in advance of their appointment. In addition to the van day planning, staff at the HSPH led the process of drafting an evaluation tool, including objectives for the events and data measures for each objective.

The YWCA recruited local agencies to assist in on-site health insurance eligibility verification and enrollment during van days. The organizers also recruited many community volunteers to participate in the project. This aligned the van days with the YWCA's mission of rooting all events firmly in the community and providing a warm, inviting atmosphere. Volunteers included individuals from a range of community organizations, HSPH, as well as local high school students, seniors from the community, and trained YWCA peer leaders.

Project implementation

Once the dates of the van days were agreed upon by all parties—May 12, 2007; August 25, 2007; November 3, 2007; March 29, 2008; and May 3, 2008—the process of recruiting and enrolling women began. The group marketed the van days via press releases and paid advertisements through a multipronged media campaign that included a variety of Spanish-language print and radio sources. Planning agencies also recruited three women from local media outlets to serve as spokespeople. After receiving a mammogram at van days, each spokesperson talked about it personally on the radio or in a newspaper editorial.

The YWCA staff instituted an intensive process for registering women for a mammogram prior to the van day. This process included collecting information from the women on insurance status, medical history, previous mammography screening, and demographic characteristics. After registration, a letter was sent to participants with details on physician appointment time for their physical exam as well as meeting time to complete an application for health insurance. A reminder call was made prior to the appointment. As needed, the YWCA arranged transportation and provided childcare so that the women would be able to attend their appointments.

On the van days, to ensure the warm, inviting, community-friendly atmosphere they sought, the YWCA staff provided food and beverages, raffle prizes, hand massages, and, at two of the van days, single roses in observation of Mother's Day. Staff from the participating organizations disseminated educational materials to the women about breast cancer, clinical breast exam, and self-breast exam, and information on prostate cancer was provided to the men who accompanied women. These personal touches are a hallmark of the YWCA, and planning group members attributed the success of the van days in part to this approach, as well as the strong connection and trust between community clients and YWCA staff.

The primary objective of the van days was to increase mammography screening capacity among medically underserved women, yet this venue also provided a unique opportunity to increase enrollment in the Women's Health Network (WHN) Program and MassHealth (Massachusetts' Medicaid program). The availability of onsite enrollment was an opportunity to insure as many women as possible, and was a critical step in meeting the objective of ensuring continuity of care for women who did not already have insurance or a regular health-care provider.

To ensure the effectiveness of their collaboration, YWCA and BMV staff debriefed following each van day. This debriefing allowed staff to discuss their experiences, raise any concerns, and identify ways to address issues prior to the next van day.

RESULTS

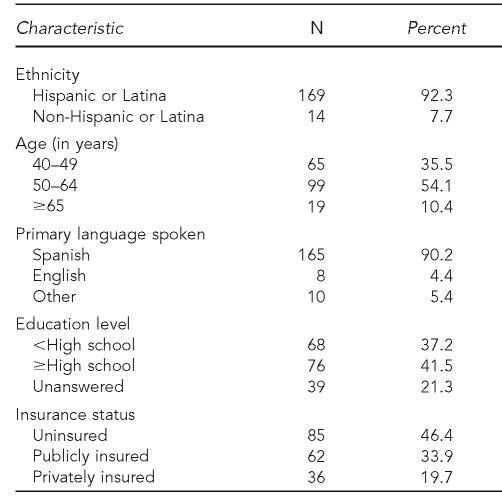

Of the 183 women who received mammography screening during one of the five van days, 92% were Hispanic/Latina, 90% spoke Spanish as their primary language, 42% had at least a high school education, and 46% were uninsured at the time of registration (Table 2). Of the women without any form of insurance, 92% were enrolled into the WHN Program, providing them with access to free services for diagnostic follow-up, subsequent mammograms, as well as free Pap smears and other preventive services.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of women screened on Boston's Mammography Van in Lawrence, Massachusetts: 2007–2008 (n=183)

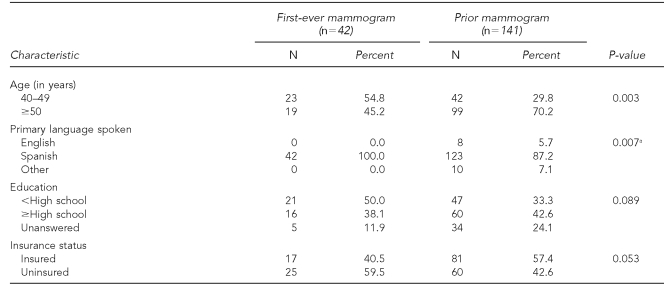

Demographic characteristics of participants varied by prior mammography status (Table 3). Women who had never received a mammogram were more likely to be younger, less educated, and uninsured than women who had received a prior mammogram. We would reasonably expect to see the difference in prior mammogram status by age, given that older women would have had more potential opportunities and prompts to receive a mammogram than younger women. However, the results also clearly showed the trend toward lower education and lack of insurance status being associated with first-ever mammography screening, though these did not achieve statistical significance. Finally, while 90% of all participants spoke Spanish as their first language, 100% of the women coming in for their first mammogram spoke Spanish.

Table 3.

Demographic characteristics of women screened on Boston's Mammography Van in Lawrence, Massachusetts, by prior mammography status: 2007–2008

aFisher's exact test used because of small expected cell sizes.

Among all women who received screening, 23% had never had a previous mammogram, and of those scheduled, only 14% missed their appointment (Table 4). Using data on women who had received BMV services in fiscal year 2007 in Boston as an external comparison group, the percentage of Lawrence participants receiving their first-ever mammogram was nearly twice as high, and the percentage of registered participants who did not show up for their appointments (“no shows”) was about half the Boston rate.

Table 4.

Mammography service data from a 2007–2008 mobile mammography pilot in Lawrence, Massachusetts, and from Boston's Mammography Van for fiscal year 2007

NA = not applicable

Characteristics of women with abnormal findings

Of the 183 women screened, 25 (14%) had abnormal findings that required follow-up care (Table 5). Among women with an abnormal finding, 92% were Hispanic/Latina, representative of the total group screened, and 52% were aged 40–49 years, reflecting a younger age distribution than among all women screened. The percentage of women reporting a first-ever mammogram was similar between women with an abnormal finding (24%) and the total group screened (23%). Of the 25 women who had an abnormal finding, 22 (88%) entered the health-care system to receive follow-up services. As of May 2009, 17 (68%) had completed their follow-up, four (16%) were receiving short-term (three-month) follow-up, three had been officially lost to follow-up, and one had received a diagnosis of breast cancer (Table 5).

Table 5.

Demographic characteristics and follow-up results of the women who had abnormal mammogram findings in a 2007–2008 mobile mammography pilot in Lawrence, Massachusetts (n=25)

DISCUSSION

The mobile mammography pilot project in Lawrence was successful in its outreach and recruitment efforts—as indicated by the low no-show rate—and in identifying and registering the women most in need—as seen in the high percentages of first-ever mammograms among all recipients and women with abnormal findings. The initiative developed an effective collaboration between new and existing partners to leverage the use of the BMV service, while creating a unique, culturally sensitive, culturally appropriate screening experience in community-based settings. The results of the pilot indicate that the project served as an important linkage between medically underserved women and the health-care system, as indicated by the high percentages of women who enrolled into the WHN Program and entered the health-care system to receive follow-up care for abnormal mammograms.

Each organization involved in the planning and execution of the van days played an important role in meeting the project objective to reach underserved women, focusing on their respective strengths and using their prior experience either to serve the Greater Lawrence community or to provide mammography services. Based on the conclusions of the planning group and stakeholders, key elements of the program's success included community outreach and recruitment strategies accompanying the mobile mammography unit,7 personalized services during the events, and dedicated follow-up by all partners.

While the DFCI BMV has not conducted any formal cost-effectiveness analyses, mobile mammography is considered to offer the same cost-effective advantages as screening mammography or mobile health programs in general. This is due to the fact that they screen asymptomatic women at regular intervals with the goal of detecting cancers early, when they are easiest to treat and the most treatment options are available, thereby reducing treatment costs. Mobile mammography has special value for disenfranchised and underserved women who might not otherwise go to a hospital or medical facility to be screened, and, thus, are at greater risk for late detection and, by extension, higher treatment costs.

Compliance with follow-up recommendations has been cited as a concern with women screened at a mobile mammography unit;6 however, the relationships established between the staff at the YWCA and the clients seen on the van may be a reason for the relatively low level (3/25) of noncompliance among women with abnormal findings. The BMV program invests substantial time and effort in ensuring that women who receive a recommendation for follow-up after their screening mammogram get the care they need in a timely manner and do not fall through the cracks. Each abnormal result was closely tracked until there was a definitive negative (return to annual screening) or positive (breast cancer diagnosis) outcome, working closely with staff at the YWCA to track and monitor unresolved cases. A staff member at the YWCA was the point of contact for patients and worked closely with each patient to identify any barriers to follow-up care and offer resources and emotional support as needed. Women were not considered lost to follow-up until all contact was broken or the women themselves refused services after extensive discussions regarding the significance of the recommendation. We believe that the role of the YWCA in all phases of the van days, including community outreach, combined with the dedication of the BMV staff in tracking follow-up appointments, was a factor in the high rate of follow-up care received among women with abnormal findings.

Limitations

While the pilot project was clearly successful in reaching Latina women in need of services, the study had several limitations. First, this was not a randomized study; it targeted and enrolled all interested women. Therefore, generalizability is limited because we do not have information that might be helpful in understanding how the women who participated might be different from other underserved women in the community.

There were also some limitations in the data collection process. Although a strength of the project was that both the YWCA and BMV had strongly established protocols for collecting information about the women for purposes of recruitment, registration, treatment, and linkage to services, in some cases, confusion occurred when the two agencies defined data indicators differently. During the review of the data, the group found inconsistencies in some of the reported data indicators. In most cases, differences in data reported were reconciled successfully, but this process took extra time and effort that could have been prevented. For future initiatives, we recommend that partners clarify precise definitions of data collection indicators and which agency will collect them.

Commonly raised concerns about mobile mammography include quality control, cost-effectiveness, and patients' compliance with follow-up recommendations. Mobile mammography units, including the BMV, are subject to the same strict oversight and guidelines for breast screening provided by the Mammography Quality Standards Act and Program as any mammography facility. The DFCI BMV is inspected annually by the Massachusetts Department of Public Health as well as the American College of Radiology. The quality of the mammograms conducted on the BMV can be shown in their callback rate, which, for technical rather than diagnostic reasons, was extremely low during the time period of the Lawrence pilot program.

CONCLUSION

Providing mobile mammography services through trusted, community-based service organizations can be effective in increasing access and decreasing barriers to screening hard-to-reach populations. This can be most effective if utilizing a collaborative partnership approach that includes input from all invested stakeholders, including community-based organizations, academic institutions, state and local government, and the medical community. It also requires considerable resource allocation of staff time from a trusted community-based organization to provide personalized support and repeated communication for recruitment and follow-up. Working with a well-established mobile mammography van program with rigorous procedures in place for assuring continuity of care is essential. We recommend that cancer centers with mobile mammography units partner with communities interested in piloting the use of this mobile service to serve low SES and medically underserved women in their communities.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Boston's Mammography Van, in particular Ivannia Giraldo, Kerline Saint-Fleur, Kayla Zaremksi, and other members of their staff, as well as Sarah Oppenheimer from the Harvard School of Public Health, for their valuable support in preparing this article.

Footnotes

Articles for From the Schools of Public Health highlight practice- and academic-based activities at the schools. To submit an article, faculty should send a short abstract (50–100 words) via e-mail to Allison Foster, ASPH Deputy Executive Director, at afoster@asph.org.

This article was supported in part by MassCONECT, funded under grant #5 U01 CA114644 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NCI's Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures for Hispanics/Latinos, 2006–2008. Atlanta: ACS; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Center for Health Statistics (US) Health, United States, 2007, with chartbook on trends in the health of Americans. Hyattsville (MD): NCHS; 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolk RB. Hidden costs of mobile mammography: is subsidization necessary? Am J Roentgenol. 1992;158:1243–5. doi: 10.2214/ajr.158.6.1590115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeBruhl ND, Bassett LW, Jessop NW, Mason AM. Mobile mammography: results of a national survey. Radiology. 1996;201:433–7. doi: 10.1148/radiology.201.2.8888236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naeim A, Keeler E, Bassett LW, Parikh J, Bastani R, Reuben DB. Cost-effectiveness of increasing access to mammography through mobile mammography for older women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:285–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pisano ED, Yankaskas BC, Ghate SV, Plankey MW, Morgan JT. Patient compliance in mobile screening mammography. Acad Radiol. 1995;2:1067–72. doi: 10.1016/s1076-6332(05)80517-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Derose KP, Duan N, Fox SA. Women's receptivity to church-based mobile mammography. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2002;13:199–213. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reuben DB, Bassett LW, Hirsch SH, Jackson CA, Bastani R. A randomized clinical trial to assess the benefit of offering on-site mobile mammography in addition to health education for older women. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:1509–14. doi: 10.2214/ajr.179.6.1791509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Census Bureau (US) 3-year estimates, fact sheet, Lawrence, Massachusetts. Washington: Census Bureau; 2010. 2006–2008 American Community Survey. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Census Bureau (US) 3-year estimates, fact sheet, Boston, Massachusetts. Washington: Census Bureau; 2010. 2006–2008 American Community Survey. [Google Scholar]