Abstract

Purpose

Popular generalized equations for estimating percent body fat (BF%) developed with cross-sectional data are biased when applied to racially/ethnically diverse populations. We developed accurate anthropometric models to estimate dual X-ray absorptiometry percent body fat (DXA-BF%) that can be generalized to ethnically diverse young adults in both cross-sectional and longitudinal field settings.

Methods

This longitudinal study enrolled 705 women and 428 men (age, 17 to 35 y) for 30 weeks of exercise training (3 d/wk, 30 min/d, 65-85% predicted VO2max). The ethnicity was 37% non-Hispanic White (NHW), 29% Hispanic, and 34% African-American (AA). DXA-BF%, skinfold thicknesses, and body mass index (BMI) were collected at baseline, 15 wk, and 30 wk.

Results

Skinfolds, BMI, and race/ethnicity were significant predictors of DXA-BF% in linear mixed model regression analysis. For comparable anthropometric measures (e.g., BMI), DXA-BF% was lower in AA women and men, but higher in Hispanic women compared to NHW. Addition of BMI to the skinfold model improved the standard error of estimation (SEE) for women (3.6% vs. 4.0%), whereas BMI did not improve prediction accuracy of men (SEE = 3.1%).

Conclusion

These equations provide accurate predictions of DXA-BF% for diverse young women and men in both cross-sectional and longitudinal settings. To our knowledge, these are the first published body composition equations with generalizability to multiple time points and the SEE estimates are among the lowest published in the literature.

Keywords: body composition, percent body fat, dual energy X-ray absorptiometry, body mass index, skinfolds

Introduction

Obesity, which is characterized by an excess accumulation of body fat, is a risk factor for many chronic diseases (24-25, 27, 33). Anthropometric variables are commonly used in clinical and field settings to estimate laboratory-measured body composition (9-10, 14, 19, 21, 23). The Durnin and Womersley (10) and Jackson and Pollock (19, 21) generalized equations were designed to estimate two-component (2-C) percent fat (BF%) from combinations of skinfolds. The generalized skinfold equations were developed using cross-sectional samples of men and women who varied in age and BF%. These popular generalized equations have been cited over 4,300 times in the scientific literature.

Recent cross-validation research (2, 17) showed that the Jackson-Pollock generalized equations were highly correlated with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) (women r = 0.85, men r ≥ 0.93), but lacked accuracy, systematically underestimating DXA-BF%. In addition, BMI estimates of BF% determined using a variety of laboratory-based measures have been shown to be biased when applied to racially/ethnically diverse populations (4-9, 11-12, 16, 23). Specifically, for the same BMI, the BF% of African-American (AA) men and women is overestimated, while the BF% of Hispanics and Asians is underestimated, relative to non-Hispanic white (NHW) men and women. Jackson et al. (17) showed that this race/ethnicity bias extended to skinfold BF% estimates. Generalized skinfold equations overestimate the BF% of AA men and underestimate BF% of Hispanic men and women. Two major limitations of generalized equations (10, 19, 21) are that they were developed with samples of nearly all NHW men and women and using two-component (2-C) BF% as the referent standard. The contemporary U.S. adult population has become more obese and racially/ethnically diverse (29), and multi-component models have replaced 2-C BF% as the referent standard (15).

BF% prediction models using anthropometric measures have used cross-sectional data to develop multiple regression equations to estimate laboratory-measured BF% from combinations of anthropometric variables (2, 10, 19, 21). These equations have been shown to provide accurate estimates of BF% in cross-sectional samples of largely NHW men and women. What have not been developed to date are prediction models that can be applied to infer changes in BF% over time for diverse young men and women. The purpose of this study was to develop accurate anthropometric models to estimate dual X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) percent fat (DXA-BF%) that generalize to diverse young adults in cross-sectional and longitudinal field settings. Anthropometric prediction models were developed using the sum of three skinfold measurements (Σ3S) and body mass index (BMI) obtained on NHW, AA, and Hispanic adults who ranged in age from 17 to 35 y. Because of the well-documented sex differences in body composition, separate models were developed for men and women.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

Subjects were recruited from the Training Intervention and Genetics of Exercise Response (TIGER) study. The TIGER subjects were students enrolled at the University of Houston (Houston, Texas, USA); the study protocol was approved by the university's Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects and subjects volunteered to participate by signing informed consent. The target population consisted of sedentary women and men under the age of 35 years who exercised less than 30 minutes per week for the previous six months, and who were not actively limiting caloric intake by dietary modification. Subjects were excluded if they had a known physical or physiological contraindication to aerobic exercise or a diagnosed metabolic disorder that may alter body composition.

The TIGER study subjects engaged in 30 weeks (two consecutive semesters) of exercise training, three days per week for 30 minutes per day at 65-85% of heart-rate defined VO2max (22). The data came from five yearly cohorts. For this analysis, the subject sample consisted of 705 women and 428 men, age 17-35 y and was limited to NHW, AA, and Hispanics. While the TIGER study included young men and women who self-identified as Asian or Asian-Indian, the sample sizes for those groups were deemed too small to include in the development of the prediction equations. Each subject had from one to three measurement visits over the 9-month study duration. The measurement visits were at baseline, after 15 weeks, and at the end of the 30-week exercise program. The race/ethnicity distribution of the subject sample was 423 NHW (37%), 324 Hispanic (29%), and 386 AA (34%); race/ethnicity was self-selected by the subjects.

Measurements

Height was determined with a stadiometer (SECA Road Rod; Hanover, MD), and weight was measured with a digital scale (SECA 770; Hanover, MD). Subjects self-reported their birth date and sex and selected one category from a list of race/ethnicity groups using a standard, coded demographic form. Skinfold thicknesses at the triceps, iliac crest, and thigh for the women, and at the chest, abdomen and thigh for the men were measured using Lange (Beta Technology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) or Lafayette (Lafayette Instruments, Inc., Lafayette, LA) skinfold calipers by trained technicians following standardized procedures (3, 20). The sex-specific sum of the three skinfold measurements (Σ3S) were from the same sites used to develop the Jackson-Pollock generalized equations (19, 21). Previous research (18) showed the three skinfolds measured the same common source of body fat. Each year skinfolds were taken by 3 to 5 different individuals. Prior to collecting skinfold data all testers were trained by one of the authors (ASJ). For quality control, reliability analyses were conducted. Each year the intraclass (between-testers) reliability estimates were ≥0.95. This is further supported by our previously published TIGER study data.(17) The correlation between skinfold estimated percent fat and DXA percent fat for over 1100 subjects was 0.91, among the highest reported in the literature.

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) was used to measure BF%. Whole body DXA scans were completed on a Hologic Delphi-A unit (adult whole body software v.11.2) and a Hologic Discovery W instrument (adult whole body software QDR v.12.3). The same trained technicians administered the DXA scans throughout the study. The instruments were calibrated daily with a spine standard and weekly with a step calibrator, as described by the manufacturer. The manufacturer's recommended procedures and software was used to calculate whole body fat mass, lean mass and bone mineral mass. Total DXA weight was computed by summing the DXA component measures and used to compute DXA-BF%. As recommended by Lohman and Chen (28), total DXA weight and scale measured body weight were compared with linear regression. The R2 between measured and DXA weight was >0.99. The slope of the measured-versus-DXA weight regression line of 1.01 (95% CI = 1.00, 1.02) and the intercept of -0.08 (95% CI = -0.37, 0.20) were within chance variation of 1.0 and 0, respectively. The standard error of estimate using DXA to estimate scale-measured weight was 1.5 kg. The test-retest measurement error of DXA-BF% in our sample was 1.3% for men and 1.2% for women, similar to previous reports.(13)

The DXA data for the first two cohorts were only measured at baseline and 30-week time points. DXA data were available for all three test visits for cohorts three to five if the subject completed the exercise program. All 1133 subjects had baseline data, 457 subjects (40%) had repeat tests at 15 weeks, and 247 subjects (22%) had repeat tests at 30 weeks. The total number of observations used for data analysis was 1837.

Statistics

Maximum likelihood, linear mixed models regression with random intercepts were utilized to estimate the prediction equations (30) using the Stata xtmixed program (Stata 10.1, StataCorp, College Station, TX). Due to the well-documented sex differences in the relation of anthropometric measures to body composition (19, 21, 23), the analyses were stratified by sex. The dependent variable was DXA-BF%. The independent variables were the Σ3S, BMI, and race/ethnic group membership, which comprised the fixed part of the model. Race/ethnic group was coded as a categorical variable using NHW as the referent group. A top-down strategy (34) was used to build the field models. The relationship between the Σ3S and 2-C BF% is known to be nonlinear (19, 21), so both the linear (Σ3S) and quadratic (Σ3S2) skinfold terms were examined.

The starting model (full model) included all independent variables (Σ3S, BMI, and race/ethnic group). Restricted models were then developed using only Σ3S and race/ethnic group. Random intercepts were included to accommodate the multiple measurements over time within subjects and comprised the random part of the model. A modified Bland-Altman (1) plot of the residuals was examined to evaluate the fit for both the fixed and random models. Regression coefficients were tested for statistical significance with a z-statistic (30). The accuracy of the field models was defined by the standard error of estimate (SEE) for the fixed model, which was computed as the square root of the sum of the variances for the random intercepts and residuals (30, 34).

Results

Table 1 summarizes the sample's characteristics contrasted by sex and race/ethnicity. The mean Σ3S of the women did not differ by race/ethnic group (p=0.523). Mean weight of AA women was significantly higher than the NHW and Hispanic women (p=0.001). The mean BMI of AA women was significantly higher than NHW women (p=0.001). The DXA-BF% of Hispanic women was significantly higher than NHW and AA women (p<0.001). Weight (p=0.404) and BMI (p=0.583) of the men did not differ significantly among the race/ethnic groups, while the Σ3S (p=0.001) and DXA-BF% (p<0.001) of AA men was significantly lower than NHW and Hispanic men. For men and women, height was significantly (p<0.001) lower in Hispanics compared to other two race/ethnic groups.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics by gender and race/ethnic group.

| NHW | Hispanic | AA | All Ethnicities | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Women | (n = 232) | (n = 195) | (n = 278) | (n = 428) | ||||

| Age, y | 21.6 | 3.1 | 21.6 | 2.9 | 21.1 | 3.2 | 21.4 | 3.1 |

| Height, cm | 164.4 | 6.5 | 159.1* | 5.9 | 164.2 | 6.5 | 162.9 | 6.8 |

| Weight, kg | 68.0 | 16.6 | 67.3 | 15.9 | 73.1* | 19.6 | 69.8 | 17.8 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.2 | 5.9 | 26.6 | 6.0 | 27.1† | 6.7 | 26.3 | 6.3 |

| Sum of 3 Skinfolds, mm | 77.0 | 26.0 | 79.9 | 24.7 | 79.2 | 29.9 | 78.7 | 27.2 |

| DXA Fat, % | 30.9 | 7.4 | 34.3* | 6.6 | 31.3 | 7.9 | 32.0 | 7.5 |

| Men | (n = 191) | (n = 129) | (n = 108) | (n = 428) | ||||

| Age, y | 22.4 | 3.6 | 21.7 | 2.8 | 21.1† | 2.9 | 21.8 | 3.2 |

| Height, cm | 177.1 | 6.0 | 173.4* | 6.5 | 177.6 | 6.6 | 176.1 | 6.5 |

| Weight, kg | 83.4 | 17.6 | 82.2 | 18.8 | 86.0 | 20.9 | 83.7 | 18.9 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.6 | 5.1 | 27.3 | 5.5 | 27.2 | 5.9 | 27.0 | 5.5 |

| Sum of 3 Skinfolds, mm | 69.3 | 34.9 | 71.0 | 35.7 | 57.0* | 38.8 | 69.7 | 35.7 |

| DXA Fat, % | 20.3 | 7.5 | 21.4 | 6.8 | 17.0* | 8.5 | 19.8 | 7.7 |

NHW = Non-Hispanic White.

AA = African American.

Significantly different (p<0.05) from the other two race/ethnic groups.

Significantly different (p<0.05) from NHW.

Table 2 gives the women and men's linear mixed model analysis for the full model, including the regression coefficient estimates (Est.), standard errors (SE) of the coefficients and p-values for tests of statistical significance. The linear and quadratic skinfold regression coefficients for both the men and women were statistically significant confirming that the relation between skinfold fat and DXA-BF% was nonlinear. The coefficient for BMI for both men and women was significant (p<0.001). In the women, the coefficients for the AA and Hispanic race/ethnic groups were both significantly different from NHW. Controlling for skinfold fat and BMI, DXA-BF% was 1.34% (95% CI -1.97, -0.71) lower for AA women and 1.89% (95% CI 1.20, 2.57) higher for Hispanic women relative to NHW women. In the men, only the coefficient for the AA ethnic group was significantly different from zero. In the men, after controlling for skinfold fat and BMI, the DXA-BF% for AA was 2.40% (95% CI -3.15, -1.66) lower than for NHW. Validation analyses using a jackknife (“leave-one-out”) estimation, similar to the predicted residual sum of squares (PRESS) technique, resulted in the 95% CI for the SEE for the fixed model increasing only slightly from 3.40-3.88% to 3.36-3.93% for the women and from 2.81-3.42% to 2.70-3.54% for the men. This clinically inconsequential difference supports the validity of the equations in these populations.

Table 2.

Maximum likelihood random intercept growth linear mixed models regression results.

| Women | Men | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Est. | SE | p | Est | SE | p |

| Constant (ß) | 1.260 | 0.797 | 0.114 | -5.832 | 0.346 | <0.001 |

| Σ3S (ß) | 0.169 | 0.039 | <0.001 | 0.195 | 0.012 | <0.001 |

| Σ3S2 (ß) | -0.0007 | 0.0001 | <0.001 | -0.0005 | 0.0001 | <0.001 |

| BMI (ß) | 0.849 | 0.026 | <0.001 | 0.608 | 0.038 | <0.001 |

| AA (ß) | -1.338 | 0.320 | <0.001 | -2.399 | 0.377 | <0.001 |

| Hispanic (ß) | 1.886 | 0.797 | <0.001 | 0.053 | 0.346 | 0.877 |

| SEE (Fixed) | 3.643 | 0.123 | 3.116 | 0.157 | ||

| SEE (Random) | 1.241 | 0.049 | 1.369 | 0.074 | ||

AA = African American.

Σ3S = sum of three gender-specific skinfold sites (mm).

BMI = body mass index (kg/m2).

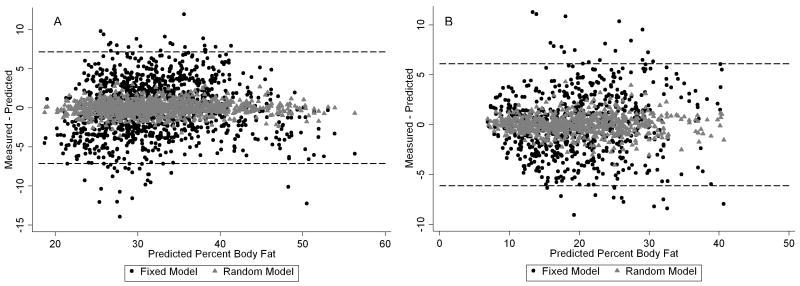

Figure 1 shows the modified Bland-Altman bivariate plots of the residuals by estimated DXA-BF% with the residuals of the random model superimposed on those of the fixed model. A graphic analysis of these residuals showed that they were normally distributed (not shown). The difference in variability between the fixed and random residuals is due to the variance of the random intercept part of the models, which includes variation unique to the individual but not due to Σ3S, BMI or race/ethnic group membership. This variance component is included in the fixed residuals, but not in the random model residuals. The SEE estimates for the random intercepts model of 1.2% (95% 1.1, 1.3) for women and 1.4% (95% CI 1.2, 1.5) for men were approximately equal to the test-retest precision of DXA-BF% estimation alone.

Figure 1.

Modified Bland-Altman plots showing residuals (predicted – observed) for the fixed and random models by estimated DXA-BF% for women (A) and men (B).

Table 3 provides the sex and race/ethnic group specific linear mixed model regression equations that include the Σ3S, BMI and significant race/ethnic group terms as well as models that include just Σ3S and race/ethnic group effects. The significant race/ethnic group was accounted for by adjusting the NHW constant by the significant race/ethnic group regression coefficient. These data show that, while the regression coefficient for BMI was significant, it does not improve the accuracy for men, whereas it does for women. The accuracy of these equations for use in field and clinical settings is defined by the fixed effects SEE (the square root of the sum of the variances for the random intercepts and residuals) and the 95% CI of the SEE provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Field models for estimating DXA percent body fat (BF%-DXA) by gender and race/ethnicity.

| Women Σ3S Model: SEE = 4.01% (95%CI = 3.62, 4.36) | |

| NHW | BF%-DXA = (0.387 × Σ3S) – (0.0011 × Σ3S2) + 8.341 |

| Hispanic | BF%-DXA = (0.387 × Σ3S) – (0.0011 × Σ3S2) + 8.321 |

| AA | BF%-DXA = (0.387 × Σ3S) – (0.0011 × Σ3S2) + 10.861 |

| Women Σ3S and BMI Model: SEE = 3.64% (95%CI = 3.41, 3.89) | |

| NHW | BF%-DXA = (0.169 × Σ3S) – (0.0007 × Σ3S2) + (0.849 × BMI) + 1.260 |

| Hispanic | BF%-DXA = (0.169 × Σ3S) – (0.0007 × Σ3S2) + (0.849 × BMI) + 3.146 |

| AA | BF%-DXA = (0.169 × Σ3S) – (0.0007 × Σ3S2) + (0.849 × BMI) – 0.078 |

| Men Σ3S Model: SEE = 3.07% (95%CI = 2.77, 3.40) | |

| NHW, Hispanic | BF%-DXA = (0.272 × Σ3S) – (0.0005 × Σ3S2) + 4.972 |

| AA | BF%-DXA = (0.272 × Σ3S) – (0.0005 × Σ3S2) + 3.860 |

| Men Σ3S and BMI Model: SEE = 3.12% (95%CI = 2.82, 3.44) | |

| NHW, Hispanic | BF%-DXA = (0.190 × Σ3S) – (0.0005 × Σ3S2) + (0.604 × BMI) – 5.377 |

| AA | BF%-DXA = (0.206 × Σ3S) – (0.0005 × Σ3S2) + (0.604 × BMI) – 1.987 |

NHW = Non-Hispanic White.

AA = African American.

Σ3S = sum of three gender-specific skinfold sites (mm).

BMI = body mass index (kg/m2).

Discussion

These generalized field equations can be used to estimate accurately DXA-BF% of diverse young men and women in both cross-sectional and longitudinal field settings across the wide range of DXA-BF% (6% to 53%) observed in this investigation. The finding of the non-linear relationship between Σ3S and DXA-BF% is consistent with the results reported with generalized equation studies using cross-sectional data (2, 10, 19, 21). A major difference found with these TIGER men and women was the race/ethnic group bias. Compared with NHW individuals, the DXA-BF% of Hispanic women was underestimated by 1.9% and AA women and men were overestimated by about 1.3% and 2.4%, respectively, as indicated by the regression coefficients for the respective ethnic groups in Table 2. The race/ethnic group bias is well documented for several BMI prediction models (4-9, 11, 16, 23), and these results confirm that the race/ethnic group bias extends to skinfold fat prediction models.

The final fixed model SEE estimates of 3.64% (95% CI 3.41, 3.89) for women and 3.12% (95% CI 2.82, 3.44) for men were slightly lower but within sampling error of those reported in Jackson and Pollock's original cross-sectional study (women = 3.9%, men = 3.4%) (19, 21). The error estimates for these new equations are higher than the SEE of 2.2% reported for men by Ball and associates (2). The Ball et al. equation used the quadratic sum of seven skinfolds to estimate DXA-BF% with cross-sectional data and did not examine race/ethnic group bias. Gallagher et al. (12) reported a correlation of 0.95 between four-component (4-C) and DXA BF% using a cross-sectional sample of 1,626 NHW, AA and Asian men and women. The SEE of the Gallagher et al. cross-sectional regression model was 3.2% and the 4-C data provided an accurate fit of DXA BF% (intercept = -1.7, slope = 1.06). The 95% CI of the women's field Σ3S model (3.62, 4.36%) in Table 3 confirmed that the women's equation was slightly less accurate than the laboratory 4-C measured BF% while the men's Σ3S equation (95% CI 2.77, 3.40) was within chance variation. It is also important to note that this is the first body composition validation study that reports the 95% CI of the standard error. The random errors of 1.2% and 1.4% in our model—the errors after accounting for subject-to-subject variability—are extremely low. These random error estimates are only slightly higher than the expected DXA-BF% test-retest error estimates. The low random estimates and the low fixed SEE estimates compared to the Gallagher et al. SEE for 4-C BF%, demonstrates that skinfold fat and BMI of women and men can be reliably measured. Future studies using independent samples need to cross-validate the accuracy of our models' estimates.

Hispanic and AA individuals are the two prominent minority groups in the United States. A strength of this study is that these racial/ethnic groups, along with NHW, were each represented with large samples that were all similar in size. Research has shown that, compared to NHW individuals, BMI underestimates the BF% of Asian and Asian-Indian men and women (4-8, 16). To examine the potential bias of the equations, we applied the equations (Table 3) to the data of the self-selected 107 Asian and 57 Asian-Indian women and men from the TIGER study, none of whom provided data used to develop the equations. Provided in Table 4 are the total number of observations and means and standard deviations of the residuals (i.e., measured – estimated DXA-BF%). All race-specific equations underestimated the measured DXA-BF% of Asian-Indian women and men, with substantial mean errors ranging from 2.2% to nearly 7%. In contrast, the men's NHW and Hispanic equations accurately predicted DXA-BF% for Asian men. The mean differences were near 0 and the error estimates of 2.80 and 2.91% were within the equations' 95% SEE confidence intervals. The Hispanic Σ3S and BMI equation provided a reasonable fit for Asian women. The mean error was just 0.07% and the error estimate of 3.44% was within the 95% SEE confidence interval of the women's full model. These results suggest that these equations can be accurately applied to Asian women and men but not to Asian-Indian young adults. These Asian-Indian cross-validation results are consistent with BMI research (6, 9, 16) showing that, compared to NHW, the BF% of Asian-Indian men and women is substantially underestimated from BMI. Asian-Indians need to be studied more closely in future investigations.

Table 4.

Mean and standard deviations of the differences between measured and estimated DXA-BF% for Asian-Indian and Asian men and women.

| Asian-Indian | Asian | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equation Applied | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| Men Total Observations | 37 | 78 | ||

| Σ3S NHW, Hispanic | 2.31 | 3.76 | 0.07 | 2.91 |

| Σ3S AA | 3.43 | 3.76 | 1.19 | 2.91 |

| Σ3S BMI NHW, Hispanic | 3.17 | 3.61 | -0.29 | 2.80 |

| Σ3S BMI AA | 6.02 | 3.61 | 2.57 | 2.80 |

| Women Total Observations | 43 | 103 | ||

| Σ3S NHW | 4.75 | 3.96 | 1.11 | 3.30 |

| Σ3S Hispanic | 4.77 | 3.96 | 1.13 | 3.30 |

| Σ3S AA | 2.23 | 3.96 | -1.41 | 3.30 |

| Σ3S, BMI NHW | 5.60 | 3.49 | 1.96 | 3.44 |

| Σ3S, BMI Hispanic | 3.72 | 3.49 | 0.07 | 3.44 |

| Σ3S, BMI AA | 6.94 | 3.49 | 3.30 | 3.44 |

NHW = Non-Hispanic White.

Σ3S = sum of three gender-specific skinfold sites (mm).

BMI = body mass index (kg/m2).

The cross-sectional data used to develop other generalized equations (2, 10, 19, 21) limits statistical inference to just one measurement occasion or point in time; the lack of ethnic diversity in those data also limit inference to NHW men and women. A strength of this study was the inclusion of multiple measures of individuals involved in a longitudinal study of exercise. A major advantage of mixed effects regression modeling is that it accommodates unbalanced, unevenly-spaced observations, making it an ideal tool for analyzing repeated measures data when subjects do not have the same number of observations or observations that recur at different intervals (30, 32, 34). Accounting for the repeat tests in the random part of the model allows for the valid generalization of the error estimates over multiple measurement occasions. These equations provide prediction models that estimate BF% at one point in time and have the capacity to evaluate changes over time within individuals. These equations have the same limitations as all such equations that use anthropometric measures in that estimates of body fat may be inaccurate in that individuals who have atypical body composition, such weight lifters or persons who are non-ambulatory.

A limitation of this study is that these TIGER subjects ranged in age from 17 to 35 y. The age range of the samples used to develop prior generalized prediction equations was from 17 to > 60 y. Age was included as an independent variable in these previous studies to account for the variation in age, and the age effect was statistically significant (2, 19, 21). These cross-sectional studies reported that the age-effect ranged from 0.07 to 0.12% per year. A stronger aging effect, 0.14 to 0.23% per year, has been reported for equations estimating BF% from BMI (23). In our preliminary analyses, we examined the influence of age with the TIGER subjects, found it was not statistically significant for either men (p = 0.328) or women (p = 0.752), and so did not include age in the final equations. These results suggest that these equations will likely underestimate DXA-BF% if applied to individuals older than 35 y. Since the criterion for these models was DXA percent fat and not body density, the effect of aging needs to be examined with cross-validation of these equations with older men and women. NHANES data (29) suggests that young adults are an important group to consider. Ogden et al. reported that 31.1% of men and 33.2% of women of all ages were obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) and the origin of the obesity is linked to young adulthood. The NHANES data showed that 28.0% of men and 28.9% of women, age 20 to 39 y, were obese. While these TIGER subjects are not a random sample of the United States population, a comparison with the NHANES BMI data shows the TIGER samples are reasonably representative of the U.S. population of young adults. The NHANES 2003-2004 data (29) showed that 51.7% (95% CI = 46.5, 56.9) of women and 62.2% (95% CI = 58.0, 66.4) of men age 20 to 39 years were overweight or obese (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2). The prevalence of a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 was 56% and 59% in these TIGER women and men, respectively.

Self-selection of race/ethnic group membership was another study limitation. Self-report does not allow for determination of whether the observed effects on prediction of BF% using anthropometric measures were due to race, which is considered primarily a biological factor, or ethnicity, which is influenced by culture and heritage (26). Despite these limitations, self-reported race/ethnicity was a significant predictor of BF% in our study after controlling for Σ3S and BMI; what remains unclear is how much of the variance attributed to this effect was produced by common biological and genetic factors or a result of shared sociocultural values and behaviors for subjects self-identifying in the same race/ethnic group. The genetic technique of admixture mapping provides an objective method of defining racial heritage, including individuals with multiple racial ancestries. Research has shown that admixture mapping can both localize and fine map a phenotypically important variant (31). Yaeger et al. reported that self-identified race correlated well with ancestry clusters but could not predict individual admixture (35). Genetic examination of admixture in these TIGER data in our next level of analysis should provide a clearer understanding of the potential source of bias attributed to race/ethnicity in these diverse young men and women.

The generalized equations presented here provide accurate models for estimating DXA-BF% of diverse young women and men. The standard errors of the fixed model equations are among the lowest published in the literature. The mixed model results documented a race/ethnic group bias for men and women. When using common anthropometric measurements in prediction models, the DXA-BF% of AA men and women is overestimated and underestimated for Hispanic women. This bias is controlled in our new models by using race/ethnic group as an independent variable. A major strength of these prediction equations is that the accuracy can be inferred to diverse young adults in both cross-sectional and longitudinal settings. To our knowledge, these are the first published body composition equations with generalizability to multiple time points.

Acknowledgments

Support: This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (DK062148) and a grant from the USDA Agricultural Research Services (6250-51000-046).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: None of the authors has a conflict of interest to declare. The results of the present study do not constitute endorsement by ACSM

References

- 1.Altman DG, Bland JM. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;I:307–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ball SD, Altena TS, Swan PD. Comparison of anthropometry to DXA: a new prediction equation for men. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2004;58:1525–31. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baumgartner TA, Jackson AS, Mahar MT, Rowe DA. Measurement for Evaluation in Physical Education and Exercise Science. 8th. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2007. p. 544. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang CJ, Wu CH, Chang CS, Yao WJ, Yang YC, Wu JS, Lu FH. Low body mass index but high percent body fat in Taiwanese subjects: implications of obesity cutoffs. Int J Obes. 2003;27:253–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.802197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chung S, Song J, Shin H, et al. Korean and Caucasion overweight premenopausal women have different relationship of body mass index to percent body fat wit age. J Appl Physiol. 2005;99:103–7. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01153.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deurenberg-Yap M, Schmidt G, vanStaveren WA, Deurenberg P. The paradox of low body mass index and high body fat percentage among Chinese, Malays and Indians in Singapore. Int J Obes. 2000;24:1011–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deurenberg P. Invited commentary: Universal cut-off BMI points for obesity are not appropriate. Br J Nutr. 2001;85:135–6. doi: 10.1079/bjn2000273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deurenberg P, Deurenberg-Yap M. Validity of body composition methods across ethnic population groups. Forum Nutr. 2003;56:299–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deurenberg P, Weststrate JA, Seidell JC. Body mass index as a measure of body fatness: age- and sex-specific prediction formulas. Br J Nutr. 1991;65(2):105–14. doi: 10.1079/bjn19910073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Durnin JVGA, Wormsley J. Body fat assessed from total body density and its estimation from skinfold thickness: Measurements on 481 men and women aged from 16 to 72 years. Br J Nutr. 1974;32:77–92. doi: 10.1079/bjn19740060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fernandez JR, Heo M, Heymsfield SV, Pierson RN, Jr, Pi-Sunyer FX, Wang ZM, Wang J, Hayes M, Allison DB, Gallagher D. Is percentage body fat differentially related to body mass index in Hispanic Americans, African Americans, and European Americans. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:71–5. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gallagher D, Heymsfield SB, Heo M, Jebb SA, Murgatroyd PR, Sakamoto Y. Healthy percentage body fat ranges: an approach for developing guidelines based on body mass index. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72(3):694–701. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.3.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haarbo J, Gotfredsen A, Hassager C, Christiansen C. Validation of body composition by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) Clin Physiol. 1991;11(4):331–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-097x.1991.tb00662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hannan WJ, Wrate RM, Cowen SJ, Freeman CP. Body mass index as an estimate of body fat. Int J Eat Disord. 1995;18(1):91–7. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199507)18:1<91::aid-eat2260180110>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heymsfield SB, Lohnman TG, Wang Z, Going SB. Human Body Composition. 2nd. Champaign: Human Kinetics; 2005. pp. 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackson AS, Ellis KJ, McFarlin BK, Sailors MH, Bray MS. Body mass index bias in defining obesity of diverse young adults: the Training Intervention and Genetics of Exercise Response (TIGER) Study. Br J Nutr. 2009;6:1–7. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509325738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jackson AS, Ellis KJ, McFarlin BK, Sailors MH, Bray MS. Cross-validation of generalised body composition equations with diverse young men and women: the Training Intervention and Genetics of Exercise Response (TIGER) Study. Br J Nutr. 2009;101(6):871–8. doi: 10.1017/S0007114508047764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jackson AS, Pollock ML. Factor analysis and multivariate scaling of anthropometric variables for the assessment of body composition. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1976;8:196–203. doi: 10.1249/00005768-197600830-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jackson AS, Pollock ML. Generalized equations for predicting body density of men. Br J Nutr. 1978;40:497–504. doi: 10.1079/bjn19780152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson AS, Pollock ML. A practical approach for assessing body composition of men, women, and athletes. Phys Sportsmed. 1985;13:195–206. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jackson AS, Pollock ML, Ward A. Generalized equations for predicting body density of women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1980;12:175–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jackson AS, Ross RM. Understanding Exercise for Health and Fitness. Dubuque, IA: Kendall Hunt; 1997. p. 182. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jackson AS, Stanforth PR, Gagnon J, et al. The effect of sex, age, and race on estimating percent body fat from BMI: the HERITAGE Family Study. Int J Obes. 2002;26:789–96. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Janssen I, Katzmarzyk PT, Ross R. Body mass index, waist circumference, and health risk: evidence in support of current National Institutes of Health guidelines. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(18):2074–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.18.2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Janssen I, Katzmarzyk PT, Ross R. Waist circumference and not body mass index explains obesity-related health risk. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79(3):379–84. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.3.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaplan JB, Bennett T. Use of race and ethnicity in biomedical publication. JAMA. 2003;289(20):2709–16. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.20.2709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lean ME. Pathophysiology of obesity. Proc Nutr Soc. 2000;59(3):331–6. doi: 10.1017/s0029665100000379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lohman TG, Chen Z. Dual Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry. In: Heymsfield SB, Lohnman TG, Wang Z, Going SB, editors. Human Body Composition. Champaign: Human Kinetics; 2005. pp. 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ogden CL, Carrol MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999-2004. JAMA. 2006;295:1549–55. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rabe-Hesketh S, Skrondal A. Multilevel and Longitudinal Modeling Using Stata. 2nd. College Station, TX: Stata Press; 2008. p. 553. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reich D, Patterson N, Ramesh V, et al. Admixture mapping of an allele affecting interleukin 6 soluble receptor and interleukin 6 levels. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80(4):716–26. doi: 10.1086/513206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Twisk J. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis for Epidemiology: A Practical Guide. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2003. p. 320. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Welborn TA, Dhaliwal SS. Preferred clinical measures of central obesity for predicting mortality. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2007;61(12):1373–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.West BT, Welch KB, Galecki AT. Linear Mixed Models. New York: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2007. p. 353. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yaeger R, Avila-Bront A, Abdul K, et al. Comparing genetic ancestry and self-described race in African Americans born in the United States and in Africa. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(6):1329–38. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]