Abstract

We describe the synthesis, characterization, aqueous behavior, and catalytic activity of a new generation of FeIII-TAML (TetraAmido Macrocycle Ligand) activators of peroxides (2), variants of  (2d), which have been designed to be especially suitable for purifying water of recalcitrant oxidizable pollutants. Activation of H2O2 by 2 (kI) as a function of pH was analyzed via kinetic studies of Orange II bleaching. This was compared with the known behavior of the first generation of FeIII-TAMLs (1). Novel reactivity features impact the potential for oxidant activation for water purification by 2d and its aromatic ring substituted dinitro (2e) and tetrachloro (2f) derivatives. Thus, the maximum activity for 2e occurs at pH 9, the closest yet to the EPA guidelines for drinking water (6.5–8.5) allowing 2e to rapidly activate H2O2 at pH 7.7. In water, 2e has two axial water ligands with pKas of 8.4 and 10.0 (25 °C). The former is the lowest for all FeIII-TAMLs developed to date and is key to 2e’s exceptional catalytic activity in neutral and slightly basic solutions. Below pH 7 2d was found to be quite sensitive to demetalation in phosphate buffers. This was overcome by iterative design to give 2e (hydrolysis rate 2d > 100×2e). Mechanistic studies highlight 2e’s increased stability by establishing that to demetalate 2e at a comparable rate to which H2PO4− demetalates 2d, H3PO4 is required. A critical criterion for green catalysts for water purification is the avoidance of endocrine disruptors, which can impair aquatic life. FeIII-TAMLs do not alter transcription mediated by mammalian thyroid, androgen or estrogen hormone receptors, suggesting that 2 do not bind to the receptors and reducing concerns that the catalysts might have endocrine disrupting activity.

(2d), which have been designed to be especially suitable for purifying water of recalcitrant oxidizable pollutants. Activation of H2O2 by 2 (kI) as a function of pH was analyzed via kinetic studies of Orange II bleaching. This was compared with the known behavior of the first generation of FeIII-TAMLs (1). Novel reactivity features impact the potential for oxidant activation for water purification by 2d and its aromatic ring substituted dinitro (2e) and tetrachloro (2f) derivatives. Thus, the maximum activity for 2e occurs at pH 9, the closest yet to the EPA guidelines for drinking water (6.5–8.5) allowing 2e to rapidly activate H2O2 at pH 7.7. In water, 2e has two axial water ligands with pKas of 8.4 and 10.0 (25 °C). The former is the lowest for all FeIII-TAMLs developed to date and is key to 2e’s exceptional catalytic activity in neutral and slightly basic solutions. Below pH 7 2d was found to be quite sensitive to demetalation in phosphate buffers. This was overcome by iterative design to give 2e (hydrolysis rate 2d > 100×2e). Mechanistic studies highlight 2e’s increased stability by establishing that to demetalate 2e at a comparable rate to which H2PO4− demetalates 2d, H3PO4 is required. A critical criterion for green catalysts for water purification is the avoidance of endocrine disruptors, which can impair aquatic life. FeIII-TAMLs do not alter transcription mediated by mammalian thyroid, androgen or estrogen hormone receptors, suggesting that 2 do not bind to the receptors and reducing concerns that the catalysts might have endocrine disrupting activity.

Introduction

Everyone needs an adequate supply of clean water to live a healthy life.1 Yet pure water is getting harder to come by as, among other things, contamination by synthetic chemicals increases on a global scale.2, 3 The stakes for health and the environment are compounded by findings that certain everyday chemicals we have long assumed to be safe are endocrine disruptors (EDs) that can interfere with cellular development at environmentally relevant concentrations to impair living things.4 FeIII–TAMLs (Chart 1) are small-molecule catalysts that activate hydrogen peroxide via peroxidase-like cycles to rapidly and efficiently5 purify water of many chemicals, including EDs,6–8 as well as hardy pathogens.9 The prototype (1a, Chart 1) is in commercial use and others will follow.

Chart 1.

FeIII-TAML activators of peroxides of the first (1) and second (2) generation discussed in this work. Y is usually a water molecule.

FeIII–TAML catalysis rates are significantly pH dependent, maximizing for generation 1 (the B* series) in the 10–11 range.5, 10, 11 This presents the intriguing design challenge of achieving the maximum rate in the 5–8 pH range commonly found for natural waters.12 Environmental performance also can be advanced by improving the resistance of FeIII–TAML to degradation by protic ligands (general acids)13 that are often present in polluted waters and by removing concerns in a precautionary sense that FeIII–TAML technologies might contaminate water with persistent catalyst degradation fragments. With regard to this last design target, until recently only the most aggressive first generation FeIII–TAML would rapidly oxidize persistent pollutants—all were fluorinated and one was additionally chlorinated.10, 11 So to escape the prospect of fluoride or persistent organohalogen residues arising from FeIII–TAML processes, generation 2 catalysts were successfully designed to achieve high reactivity and to be fluorine-and chlorine-free for commercially viable catalysts.14 But it has turned out that the catalysts 2 deliver other significant performance advantages for environmental applications.

On the basis of equilibrium and kinetic data, we explain here the structure-activity factors that give 2e a maximum activity closer to neutral pH than any prior FeIII–TAML and why it is much more resistant than 2d to demetalation by common, protic, water-borne ligands. From this understanding of the etiology of 2e’s superior properties, FeIII–TAML design is set up to achieve even higher performance and more environmentally beneficial homogeneous oxidation catalysts. At the scientific level, iron–TAML compounds represent the best available catalytic solution to the oxidative purification of large quantities of water. Many other oxidation catalysts exist, but their applications require non-aqueous conditions or they achieve few turnovers.15–17

Experimental

Materials and Methods

Kinetic measurements were carried out using Hewlett-Packard Diode Array spectrophotometers (models 8452A and 8453) equipped with a thermostatted cell holder and automatic 8-cell positioner using plastic poly(methyl methacrylate) 1 cm cuvettes. Measurements of the UV/Vis spectra of 2e for determining its pKa values were carried out on a Cary 5000 UV/Vis-NIR spectrophotometer (Varian) in quartz cells. 1H NMR data were collected at 300 K with a Bruker Avance 300 instrument operating at 300 MHz in d6-DMSO, the chemical shifts (δ) being referenced to the residual proton DMSO signal at δ 2.5. Combustion analyses were performed by Midwest Microlabs, LLC. Bioluminescence assays were performed using a Dynatech ML3000 microplate luminometer, colorimetric β-galactosidase assays were performed using a Molecular Devices Spectramax plate reader. The FeIII–TAML 2e was synthesized as indicated previously.14 All reagents and solvents were at least ACS reagent grade in quality and were obtained from commercial sources. They were used as received, or if noted, after purification as described elsewhere.18 Orange II was purified by column chromatography on reversed phase silica gel using SMT-Bulk C18 # BOD-35–150 resin (Separation Methods Technologies) using water as an eluent.

Synthesis of 2d (Scheme 1S)

1,2-Diaminobenzene (9 g, 0.083 mole) was dissolved in freshly distilled THF (100 mL) and triethylamine (15 mL) was added. Di-tert-butyl dicarbonate (Boc2O) (18 g, 0.082 mol) was dissolved in THF (50 mL) and placed in a dropping funnel. The solution was added dropwise to the 1,2-diaminobenzene solution with rapid stirring and was then stirred overnight. The THF was removed by the rotary evaporation to yield yellow viscous residue, which yielded yellow-brown crystals in the freezer (−25 °C). The crystals were separated and recrystallized from hot ethanol to yield (2-aminophenyl)carbamic acid 1,1-dimethylethyl ester (A; 10.5 g, 61%). 1H NMR (d6-DMSO): 1.45 (s, 9H, tBu), 4.8 (s, 2H, NH2), 6.55 (td, 1H, ArH), 6.7(dd, 1H, ArH), 6.85(td, 1H, ArH), 7.2 (dd, 1H, ArH), 9.65 (br s, 1H, CONHBoc). Anal. Calcd. For C11H16N2O4 (208.26): C 63.44; H 7.74; N 13.45. Found: C 63.53; H 7.7; N 13.7%. Compound A (4 g, 0.0192 mol) was dissolved in dry THF (100 mL) and pyridine (2 mL) was added. Dimethylmalonyl dichloride (1.31 mL, 0.00958 mol) dissolved in dry THF (50 mL) was added at a rate of 1 drop every 3 s using a dropping funnel. A white precipitate of pyridinium chloride formed and was removed by filtration. Removal of THF from the filtrate under vacuum gave a viscous oil, which was placed in the freezer (−25 °C) to form a precipitate which was further purified by sonication in hexane for 10 min. Solid 2-[[3-[[2-[[(1,1-dimethylethoxy)carbonyl]amino]phenyl]amino]-2,2-dimethyl-1,3-dioxopropyl]amino]phenyl]carbamic acid-1,1-dimethylethyl ester (B) was collected by filtration in greater than 90% yield. 1H NMR (d6-DMSO): 1.4 (s, 18H, tBu), 1.55 (s, 6H, CH3), 7.15 (m, 4H, ArH), 7.5 (m, 4H, ArH), 8.7 (s, 2H, CONH), 9.3 (s, 2H, CONH). Aqueous 12 N HCl (45 mL) was added slowly to solution of B (2.5 g, 0.0049 mol) in ethyl acetate (150 mL) with rapid mixing. After stirring for 5 min, the mixture was quenched with aqueous NaOH (20 g in 500 mL) in an ice bath with rapid stirring. The pH of the aqueous layer was raised to 11 with NaOH and the organic and aqueous layers were separated. The aqueous layer was extracted three times with CH2Cl2 (100 mL each). All organic layers were combined, dried over MgSO4 and filtered. The volume was reduced to 4 mL and the residue was sonicated in diethyl ether (15 mL) to afford solid N1,N3-bis(2-aminophenyl)-2,2-dimethylpropanediamide (C; 1.12 g, 74%). 1H NMR (d6-DMSO): 1.55 (s, 6H, CH3), 4.9 (br s, 4, NH2), 6.55 (m, 2H, ArH), 6.73 (m, 2H, ArH), 6.97 (m, 2H, ArH), 9.0 (s, 2H, CONH). Anal. Calcd. For C17H20N4O2 (312.37): C 65.37; H 6.45; N 17.94. Found: C 64.95; H 6.36; N 17.8 %. Compound C (128 mg, 0.410 mmol) was dissolved in dry THF (50 mL) and NEt3 (0.115 mL, 0.903 mmol). Oxalyl chloride (0.205 mL of 2 M solution in CH2Cl2; 0.410 mmol) in dry THF (30 mL) was added overnight at a rate of 1 drop each 5 s using a dropping funnel with stirring. A precipitate formed over 12 h. After addition of CH2Cl2 (125 mL), the mixture was treated with 0.1 M KHSO4 (100 mL), 0.1 M NaHCO3 (100 mL), and H2O (100 mL) in a separation funnel. A white solid in the organic phase was filtered through a sintered glass crucible, washed with diethyl ether (5 mL) and petroleum ether (5 mL) to give a first crop of the macrocycle, 15,15-dimethyl-5,8,13,17-tetrahydro-5,8,13,17-tetraazadibenzo[a,g]cyclotridecene -6,7,14,16-tetraone (D; 41 mg, 25%). The filtrate was dried over MgSO4 and the volume was reduced to ca. 3 mL. A precipitate formed upon trituration with petroleum ether, which was filtered to yield a second crop of D (72.5 mg, 44%). 1H NMR (d6-DMSO): 9.65 (s, 2H, CONHα), 9.55 (s, 2H, CONHβ), 7.625 (m, 2H, ArH), 7.35 (m, 6H, ArH), 1.56 (s, 6H, CH3). Anal. Calcd. For C19H18N4O4 (366.37): C 62.3; H 4.95; N 15.29. Found: C 61.83; H 5.12; N 14.51 %. Metalation of D to yield 2d was performed as previously described.14 ESI-MS (negative mode) for PPh4[2d(H2O)]: 418.1 m/z; isotopic peaks 419.09(23%), 416.17(4%) m/z.

Synthesis of 2f

The corresponding sodium salt was prepared using a slightly modified procedure to that employed for 2e.14 Removal of Boc from N,N'-bis(2-carbamic acid tert-butyl ester-4,5-dichlorophenyl)-2,2-dimethylmalonamide to yield N,N'-bis(2-amino-4,5-dichlorophenyl)-2,2-dimethylmalonamide was performed in acetic acid (instead of ethyl acetate as with 2e) using 3 M HCl. The macrocyclic precursor was isolated by precipitation as the dihydrochloride salt using ice-cold diethyl ether. The macrocyclization and metalation steps were performed as described for 2e. The sodium cation was metathetically exchanged with the bis(triphenylphosphoranylidene)ammonium ([PNP+]) cation. The salt Na[2f] (4 mg) was dissolved in water (2 mL) and mixed dropwise with excess [PNP]Cl (ca. 80 mg dissolved in 4 mL of a 1/1 v/v MeOH/H2O) with stirring. The reddish orange precipitate was collected by filtration and was recrystallized from MeOH/H2O. X-ray quality crystals of [PNP]2f (Y = H2O) were obtained by slow evaporation of methanol from water. Anal. Calcd for [PNP]2f·(H2O)3, C55H46Cl4FeN5O7P2 (1148.59): C, 57.51; H, 4.04; N, 6.10 %. Found: C, 57.04; H, 3.84; N, 5.93 %.

Demetalation of 2

Compound 2d (20 mg) was dissolved in phosphate buffer (2 mL, 0.5 M, pH 8). The solution was kept overnight at 22 °C. Colorless needlelike crystals formed which were contaminated by an amorphous brown precipitate. These were separated manually, washed with water, and air dried. The 1H NMR data (δ, d6-DMSO) confirmed the material to be the macrocyclic ligand expected from hydrolysis of 2d: 9.65s, 2H (NH); 9.55s, 2H (NH), 7.7−7.2, m, 8H (ArH), 1.56s, 6H (CH3).

Kinetic Measurements

A: Demetalation. The kinetics of demetalation of 2d,e was measured at phosphate concentrations 0.1, 0.3, and 0.5 M at 25 °C as described previously.13 A stock solution of 2d in MeCN (0.005 M) was added to the phosphate buffer in a 1 cm plastic cuvette to give a [2d] of ca. 4.5×10−5 M and changes in absorbance were recorded at 350 nm. Measurements were performed in the pH range of 4.0−9.5. Pseudo-first-order rate constants (kobs) were calculated by fitting the absorbance (A) versus time (t) traces to the equation A = A∞ − (A∞ − Ao)×exp(−kobst) where Ao and A∞ are absorbances at t = 0 and ∞, respectively. Satisfactory first-order kinetics holds for at least 4–5 half-lives. The rate constants kobs, which are mean values of at least three determinations, were plotted against total phosphate concentration to obtain k1,eff as the slope of the linear plot. Measurements for 2e were performed at 385 nm as described for 2d, but the pH range of 1−5 was also covered. Calculations were performed using a Sigma Plot 2007 package (version 10.0), or Mathematica 7.0. B: Bleaching of Orange II. Initial rates of bleaching of Orange II by H2O2 catalyzed by 2 were measured essentially as described in detail previously19 in the range of H2O2 concentrations 0.0003–0.0015 M at an [Orange II] of 4×10−5 M. Solutions of H2O2 were standardized daily by measuring the absorbance at 230 nm (ε = 72.8 M−1 cm−1).20 In this work, extinction coefficients (ε) of Orange II were measured at each pH used in the kinetic experiments giving values of 19,000 M−1 cm−1 at pH 6.0−10.0 and 17,700, 15,500, 14,100, and 11,500 M−1 cm−1 at pH 10.5, 11.0, 11.5, and 12.0, respectively. C: Comparative Bleaching of Orange II at pH 7.7. A 1.5 mL aliquot of a stock solution of Orange II (4.9×10−5 M) in 0.01 M phosphate buffer added was added to a cuvette. Stock solutions of [PPh4]2d, [PPh4]2e, and [PNP]2f were made in acetonitrile and approximately 10 µL were added into the cuvette to make the concentration of iron of 2×10−7 M. An aliquot of H2O2 was added such that the concentration in the cuvette was 4.4×10−4 M. The absorbance of Orange II was monitored at 485 nm.

X-Ray Crystallography Details for 2f

C55H42Cl4FeN5O6P2; Mr = 1128.6, crystal dimensions 0.20×0.29×0.37 mm3, triclinic, P−1, a = 10.7084(9) Å, b = 16.545(2) Å, c = 16.912(2) Å, α = 116.991(8)°, β = 99.824(9)°, γ = 94.007(9)°, V = 2593.5(5) Å3, Z = 2, ρcalc = 1.445 Mg·m−3, µ = 0.62 mm−1, Mo-Kα, λ = 0.71073Å, T = 299K, 2θmax = 55°, 55 025 measured reflections, 11 780 independent reflections, Rint = 0.045, R = 0.046 (7777 observed reflections), wR2 = 0.114, S = 1.04, residual electron density 0.70/−0.54. Refinement on F2 with anisotropic displacement parameters for all non-H atoms.

Luciferase Reporter Assays of Receptor Activation

COS7 cells were cultured in phenol-red-free Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% bovine calf serum. Twenty-four hours before transfection, the cells were seeded at a density of 5×105 cells per 96-well plate. Plasmids expressing either the full-length receptors (AR, ERα), or a chimeric protein where the ligand binding domain of the receptor is fused to the DNA binding domain of GAL4 (TRβ), were co-transfected with their respective reporter constructs and pCMX-β-galactosidase control plasmid using calcium-phosphate mediated transfection as previously described.21 The expression plasmids and their reporter constructs have been described elsewhere.22 The test compounds were initially dissolved in doubly distilled water (FeIII-TAML) or DMSO (control ligands), and subsequently diluted in DMEM supplemented with 10% charcoal-resin stripped fetal bovine serum (FBS) to a final solvent concentration of 0.5%. After 24 h of ligand exposure, 50 µL aliquots of cell lysates were assayed for luciferase and β-galactosidase activity by standard protocols.22 Luciferase activity was normalized to β-galactosidase activity to control for transfection efficiency and reported as fold activation relative to the vehicle control.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis, Characterization and Pre-Screening of Catalytic Activity of D* TAML Catalysts 2

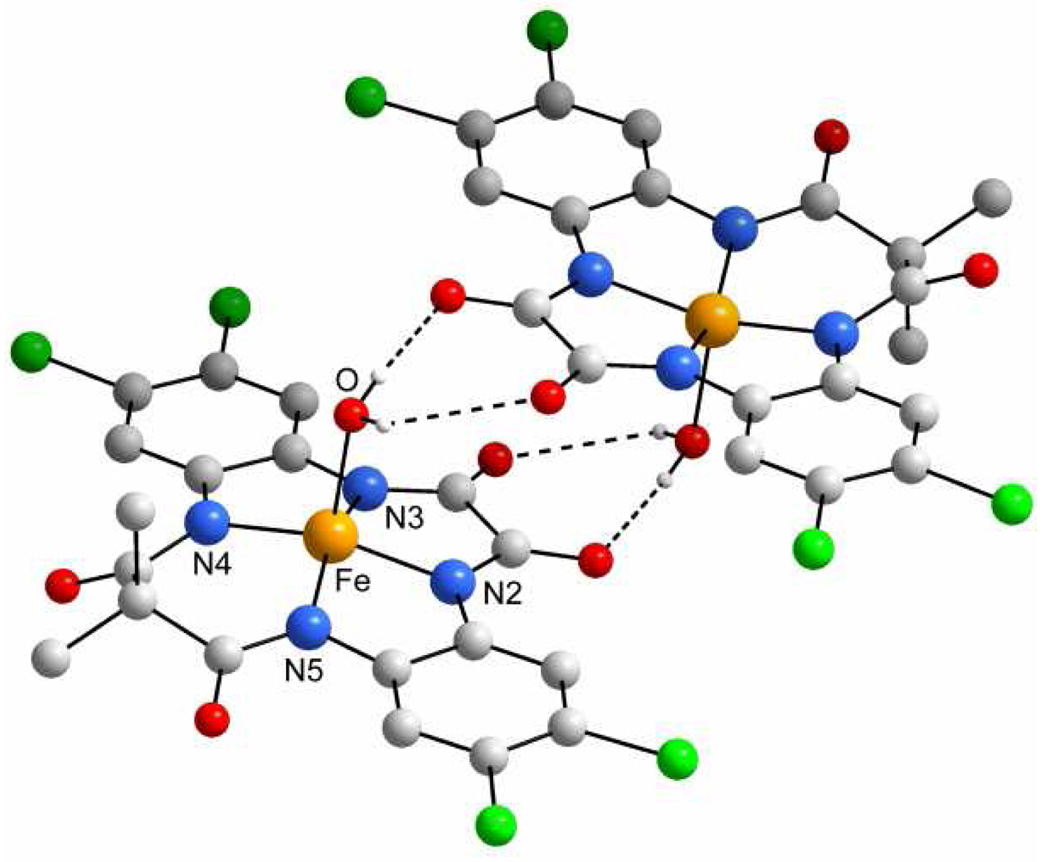

Usually FeIII-TAML activators of peroxides substituted with electron-withdrawing chloro and nitro groups show advantageous reactivity (higher oxidative reactivity and hydrolytic stability) compared with similar catalysts with electron-donating fragments.5 This explains why FeIII-TAMLs 2d–f were chosen for synthesis and comparative evaluation. The preparation of the tetrachlorinated catalyst 2f was carried out similarly to 2e.14 A minor variation involved using HCl in acetic acid as a medium for deprotection of the macrocyclic precursor, which was isolated as a diamine dihydrochloride salt. The study of 2f by X-ray crystallography revealed a square pyramidal geometry, which is typical of these small molecule peroxidase replicas.5 A new hydrogen bond system found in the structure of 2f is noteworthy. The axial water ligand of a first FeIII-TAML anion forms two hydrogen bonds with amide oxygens of the second FeIII-TAML anion, the aqueous ligand of which, in turn, forms two H-bonds with the first FeIII-TAML anion. Thus, four H··· O interactions produce a dimeric motif in the solid state structure of 2f.

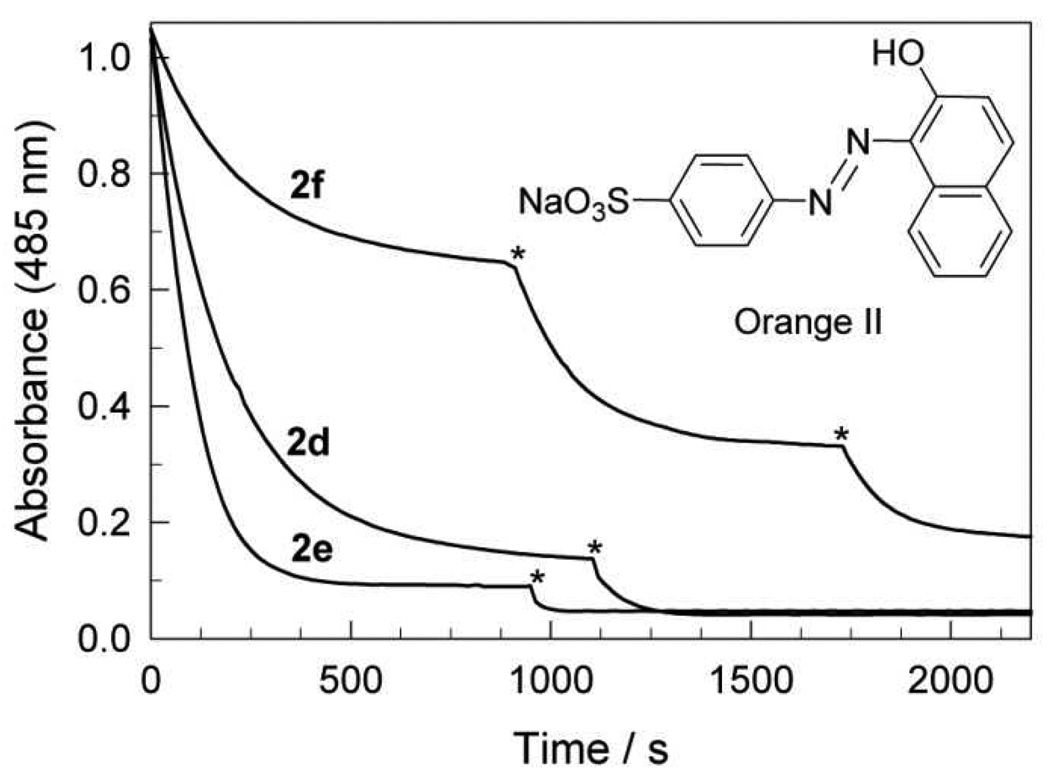

Orange II is a convenient dye for preliminary screening of FeIII–TAML/H2O2 catalysis. It has been successfully used by us5 and by other researchers as an easy-to-follow substrate in catalyzed oxidation reactions.23, 24 The data in Figure 2 compare the catalytic performance of 2d–f at neutral pH using aliquots of 2 (each time to return the solution to the 200 nM starting concentration) with >200 molar equivalents of Orange II. As can be seen, a single aliquot of the dinitro-substituted catalyst 2e caused the fastest and the deepest bleaching. More than 90% of Orange II was degraded in less than 500 s. The catalyst 2d is slightly less aggressive under the same conditions. The catalytic performance of the tetrachloro derivative 2f is significantly less in terms of both the speed and conversion. One aliquot of the catalyst destroyed less than 40% of the dye. The bleaching was still incomplete after adding two more aliquots of 2f. This screening revealed the superiority in bleaching of 2d and 2e.

Figure 2.

Bleaching of Orange II (4.9×10−5 M) by H2O2 (4.4×10−4 M) catalyzed by complexes 2d–f (2×10−7 M); asterisks indicate points of addition of a new aliquot of 2 (2×10−7 M). Conditions: pH 7.7, 0.01 M phosphate, 25 °C.

Demetalation by General Acids: Remarkable Changeover

The stability of 1a in aqueous solution is decreased in the presence of proton donors, e.g., H2PO4 −, HSO4 − and HCO3 − —a mechanism for the hydrolysis process has been proposed.13 While the rate of iron ejection is orders of magnitude slower than oxidation catalysis,10, 11, 13, 25 long-term storage of 1a in pH ≤ 8 aqueous solutions buffered by such ions is prohibited by this intrinsic property.13 Moreover, since these ions are often present in environmental waters, there is considerable potential for interruption of trace contaminant purification because, at the ultralow concentrations of catalyst, peroxide, and the targeted contaminants, any catalyst must perform for many hours to be effective. The buffer-ion induced ‘coordinative’ demetalation of 1a manifests experimentally in linear dependencies of the pseudo-first order demetalation rate constants kobs on the total phosphate concentration (with the slopes of the linear plots giving the second-order rate constants k1,eff). The rate constants k1,eff increase hyperbolically with increasing proton concentration.13

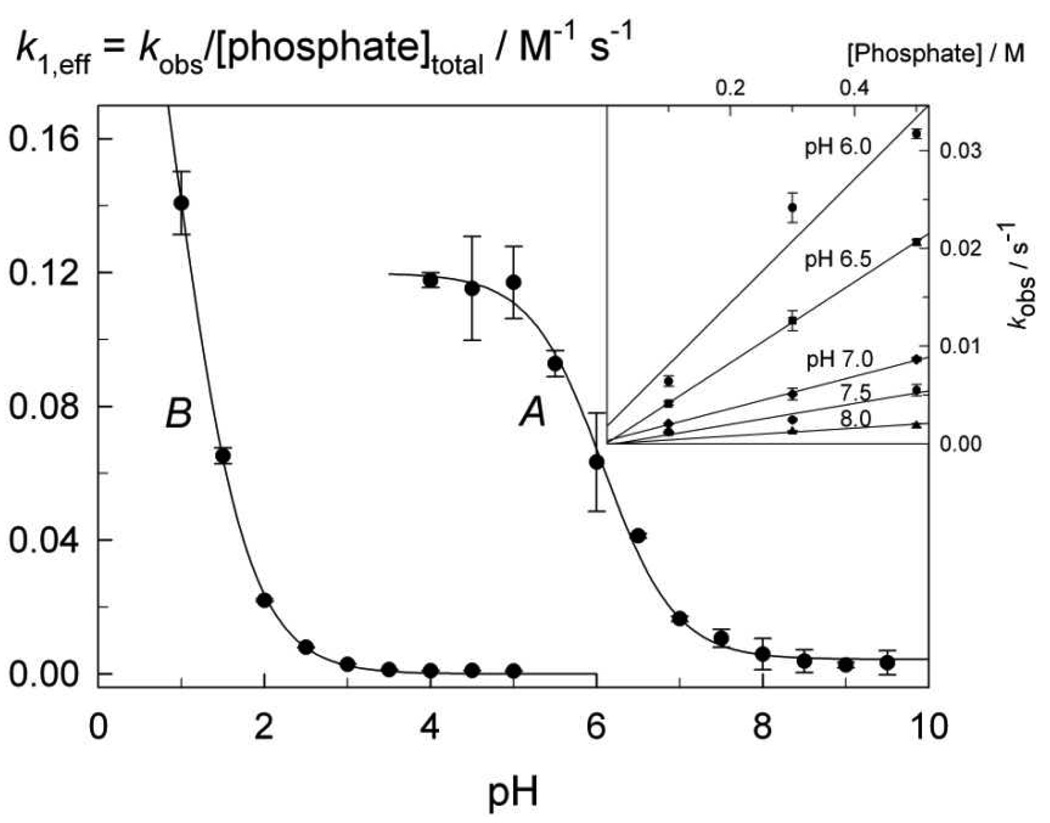

The second-generation catalyst, 2d, exhibits similar behavior. The values of kobs depend linearly on the total phosphate concentration (Inset to Figure 3), whereas the second-order rate constant k1,eff exhibits a sigmoid dependence on pH with the inflection point around 6.5 (Figure 3A). This behavior is fully accountable in terms of the ‘coordinative’ demetalation reaction mechanism (Scheme 1) with the active demetalating species being dihydrogen phosphate, H2PO4 −, and the rate expression 1 for k1,eff being,13

| (1) |

Here kα is the second-order rate constant proposed for proton delivery from the demetalating ion (general acid) to an amido nitrogen atom of FeIII-TAML and Ka is the dissociation constant under discussion.13 Obviously, kα is a composite value and equals KAHkAH in terms of the mechanism in Scheme 1, because the equilibrium for ligation by AH is strongly shifted to the left. Fitting the experimental data in Figure 3A to eq 1 gave the values of kα and pKα summarized in Table 1. The values for 1a are included for comparison. It is noteworthy that the rate constant kα for 2d is larger than that for 1a13 and therefore we decided to enhance the stability of the second generation catalysts 2 by introducing the electron-withdrawing nitro substituents as in 2e. The choice of the nitro groups was dictated by two previously discovered observations―the nitro substituents increase both the catalytic performance11 and the operational stability (resistance to suicidal inactivation)25 of FeIII-TAMLs. It might be more reasonable to anticipate that a more powerful oxidant would have a higher tendency for the self-oxidation such that findings are consistent with suicidal inactivation proceeding at the aromatic rings since the nitro groups would locally protect the rings from oxidation even while globally activating the iron reactive intermediates.25

Figure 3.

Second order rate constants k1,eff as a function of pH for the phosphate-induced demetalation of 2d (A) and 2e (B) at 25 °C. Inset shows the dependence of kobs on total phosphate concentration for demetalation of 2d.

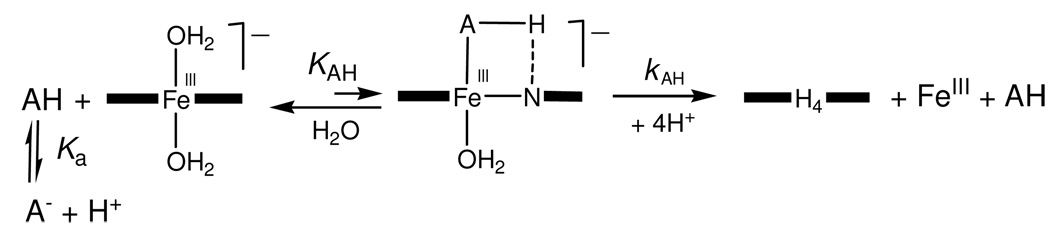

Scheme 1.

Mechanism of the buffer (general acid) promoted ‘coordinative’ iron ejection from FeIII-TAMLs.

Table 1.

Kinetic (kα= KAHkAH) and thermodynamic (pKa) parameters of eq 1 and Scheme 1 responsible for the buffer (general acid) promoted ‘coordinative’ iron ejection form FeIII-TAMLs.

| FeIII-TAML | T / °C | AH | kα / M−1 s−1 | pKα / M | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | 25 | H2PO4− | 1.3×10−3 a) | 6.55 | 14 |

| 2d | 25 | H2PO4− | 0.12±0.03 | 6.12±0.14 | This work |

| 2e | 40 | H2PO4− | (6.3±1.2)×10−3 b) | 5.5±0.5 | |

| 50 | H2PO4− | (1.5±0.1)×10−2 | 6.1±0.2 | ||

| 60 | H2PO4− | (2.0±0.1)×10−2 | 5.8±0.1 | ||

| 70 | H2PO4− | (3.0±0.2)×10−2 | 6.1±0.1 | ||

| 25 | H2PO4− | 3.0×10−3 c) | |||

| 2e | 25 | H3PO4 | 0.31±0.01 | 0.91±0.05 | This work |

ΔH≠ 47 kJ mol−1, ΔS≠ −143 J K−1 mol−1 14;

ΔH≠ 42±7 kJ mol−1, ΔS≠ −150±20 J K−1 mol−1;

extrapolated value.

The very first measurements with nitro-substituted 2e indicated its significantly higher resistance to the phosphate-induced demetalation compared to 2d. The reaction rate was very low at pH 6 and 25 °C. Rates comparable to those of 2d were observed at markedly lower pH, specifically, below 2.5 where the free proton (specific acid) catalyzed demetalation of FeIIITAMLs 1 could come into play.26 Therefore, the H+- and phosphate-catalyzed pathways for iron ejection were carefully separated for 2 catalysts. This was achieved by plotting kobs vs [total phosphate] at constant pH for a variety of pHs. The slope of the line delivers rate information for the phosphate dependent demetalation. The intercept delivers information on all other demetalating processes, including those brought about by the specific acid (see inset to Fig. 3 as an example).26 Calculation of the k1,eff values for 2e over pH 1.0 to 5.0 resulted in the pH profile shown in Figure 3B, which clearly shows that dihydrophosphate (H2PO4 −) is much less reactive toward 2e and that coordination of the more acidic phosphoric acid (H3PO4) is needed for the ejection of iron(III) from the macrocyclic cavity of 2e at a similar rate that which H2PO4 − produces for 2d. The data in Figure 3B were also fitted to eq 1 and the best-fit values are included in Table 1. The pKa value of 0.91 suggests the involvement of trihydrogenphosphate (pKa 1.7027) in the demetalation process.

In order to compare the reactivity of H2PO4 − toward 2d and 2e, the measurements with 2e in the pH range of 5.0–7.5 were performed at higher temperatures, viz. 40–70 °C. Equation 1 was found to be operative in all cases and the corresponding values of kα and Ka are included in Table 1. The Eyring equation was applied to kα in this temperature range (Figure 1S). The values of the activation parameters ΔH≠ and ΔS≠ were calculated and the value of kα was extrapolated to 25 °C (Table 1). This switch from H2PO4 − (with 2d) to H3PO4 (with 2e) as the demetalating species is quite remarkable.

The data for kα in Table 1 show that the values of kα for H2PO4 − and complexes 1a and 2e are close and 1a is even slightly more resistant to the demetalation by H2PO4 −. The enthalpies and entropies of activation, ΔH≠ and ΔS≠ are also similar (Table 1). These similarities suggest that 1 and 2 adopt similar reaction mechanisms. Large and negative enthalpies of activation are consistent with an ordered transition state. Thus, the model of ‘coordinative’ proton delivery by a general acid at the Fe–N bond of the FeIII-TAML in the rate-limiting step as previously proposed13 is fully consistent with the data reported here. However, because 2d is less stable in buffered aqueous solutions, 2e became the focus of more detailed studies.

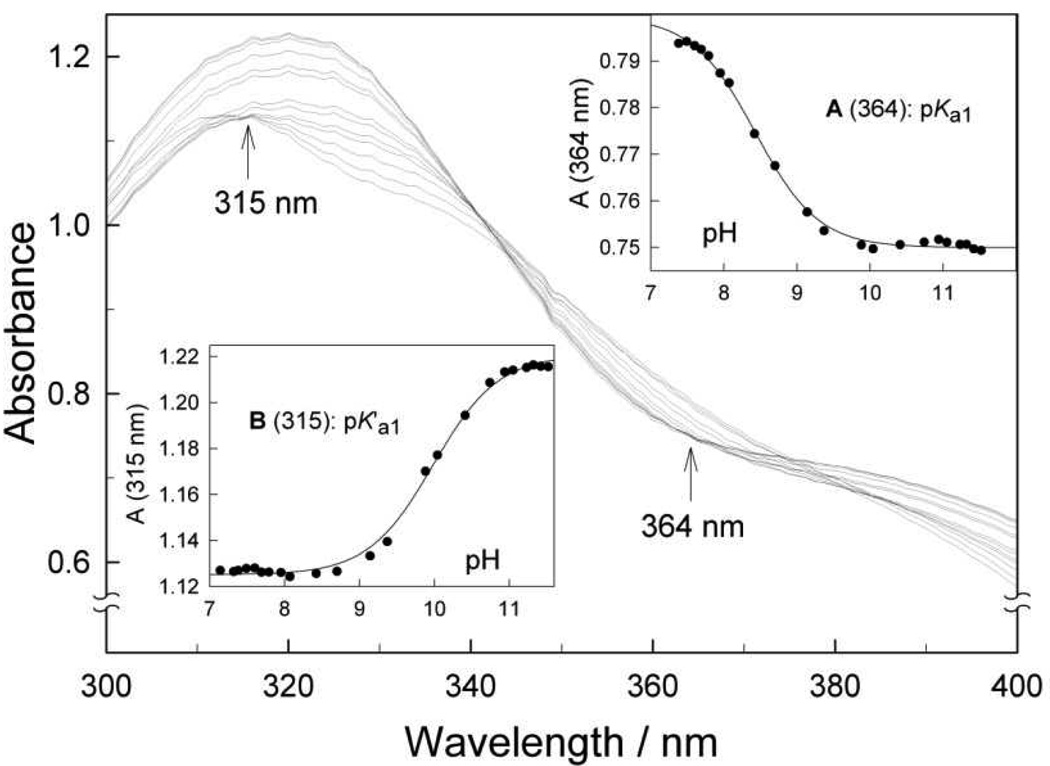

pH Titration of 2e: Evidence for Octahedral Coordination in Water

Solid FeIIITAMLs are five-coordinated square-pyramidal species as in Figure 1.5 In water, they become octahedral with two axial aqua ligands.26 The pKa values for the deprotonation of the first coordinated water in 1 fall in the range of 9.3−10.5.10, 11, 26 Since these values determine the catalytic oxidation activity of the 1 FeIII-TAMLs,5 the spectrophotometric pH titration of 2e was carried out. The deprotonation of 1 induces large changes in the UV/Vis spectrum. The spectrum of 2e is less sensitive to the pH variation in the range of 7.1−11.5 (Figure 4). But unlike with the 1 catalysts, there are no clear-cut isosbestic points over the entire pH range, though the absorbance is pH invariant at 315 and 364 nm at lower and higher pH values, respectively. The changes in absorbance at these two wavelengths are shown in Figure 4 in Insets B and A, respectively. Spectral variations in each correspond to a typical acid-base equilibrium involving one proton. Therefore, we conclude that both axial aqua ligands of the octahedral species 2e in water undergo deprotonation in this pH range as shown in the boxed part of Scheme 2.

Figure 1.

An ORTEP diagram of the anionic part of [PNP]2f with Y = water. (Fe in yellow, O in red, N in blue, and Cl in green; only H atoms of the aqua ligand are shown for clarity). Selected bond distances: Fe–N2, 1.8701(23); Fe–N3, 1.8637(22); Fe–N4, 1.8943(20); and Fe–N5, 1.8912(25) Å. The Fe–O bond distance is 2.1026(22) Å.

Figure 4.

Spectral variations of 2e (5×10−5 M) in the pH range 7.1−11.5. Insets A and B show the spectral changes at 364 and 315 nm, respectively, selected for calculating pKa1 and pK'a1. Solid lines in the insets are calculated using the best-fit parameters of eq 2. See text for details.

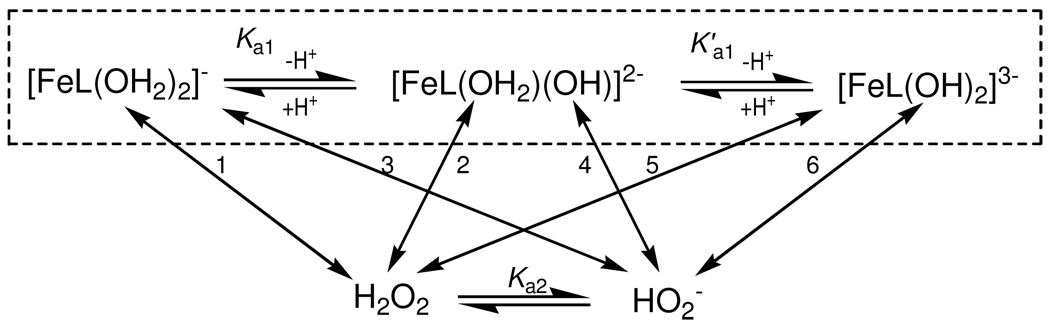

Scheme 2.

Acid-base equilibria involving 2e (in the box) and hydrogen peroxide to produce species that react pairwise to afford Oxidized TAML (see Scheme 3). Numerals at the two-sided arrows 1–6 correspond to the rate constants k1–k6, respectively.

We propose that the wavelengths of 315 and 364 nm correspond to the isosbestic points for the first (Ka1) and the second (K'a1) equilibria, respectively. The spectral changes at these wavelengths can be used for a separate evaluation of the K'a1 and Ka1 values, respectively. The data shown in insets A and B to Figure 4 were fitted to eq 2 (ε1 and ε2 are the extinction coefficients for the protonated and deprotonated forms, respectively; see SI).

| (2) |

The values of pKa1 and pK'a1 thus obtained equal 8.4±0.1 and 10.0±0.1, respectively. The former is the lowest pKa value observed for any FeIII-TAML investigated to date, suggesting that 2e has the highest effective positive charge at iron. Achieving this low pKa1 of 8.4 has been a long-term goal of the FeIII-TAML design program because the most rapidly reacting species with H2O2, the dianion [FeL(OH2)(OH)]2-,10 can now be generated at a pH that lies closer to 7 and within the pH regime of environmental and even drinking waters. The value of the second pK'a1 of 10.0 represents the first case where a second pKa has been measured because it occurs at a low enough pH to be distinctively observed. The protonation/deprotonation impacts the charge and aggressiveness of the catalytic intermediates in industrially significant mildly basic pH region. It therefore provides a possible way to alter selectivity over a rather narrow pH range.

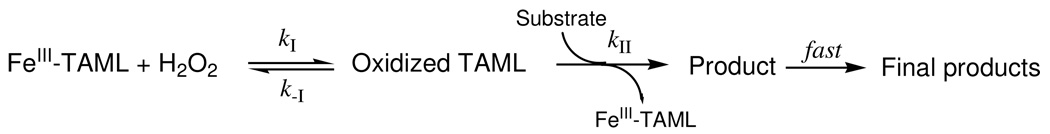

Moving the Peak of Catalytic Activity to Neutral pH

Mechanistically, FeIII-TAMLs are functional replicas of peroxidase enzymes adopting the minimalistic mechanism of catalysis shown in Scheme 3.5, 10 This mechanism is consistent with eq 3 which becomes eq 4 because k−I is usually negligible.

| (3) |

| (4) |

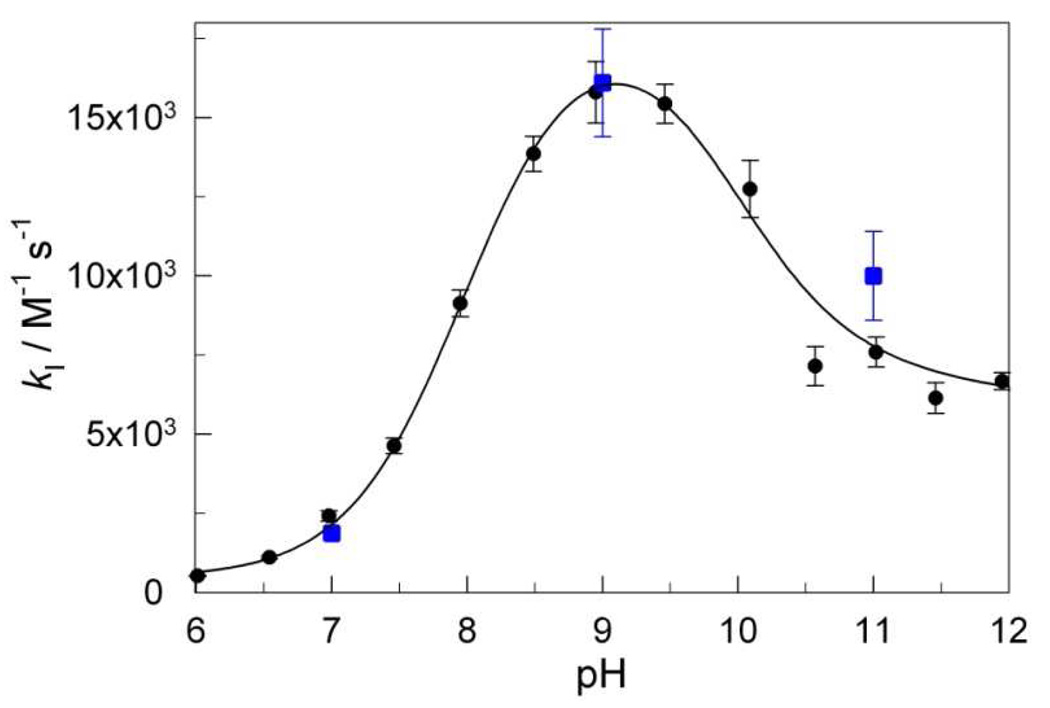

As with the majority of artificial low-molecular weight catalysts for activation of H2O2,10 the relation kI[H2O2] < kII[S] holds for FeIII-TAMLs such that the activation of H2O2 is usually the rate-limiting step. Therefore, to achieve more effective catalysts, the kI step should be positively impacted by design changes in the macrocycle. Our previous studies5, 10 have demonstrated that among the FeIII-TAML species coexisting in water, the most reactive is [FeL(OH2)(OH)]2+ (Scheme 2), making any acquired ability to alter the value of pKa1 into a tool for deliberately increasing or decreasing the catalytic reactivity with pH.11 This explains why the lowest value of pKa1, described here for 2e, promised higher values of kI at neutral pH for 2e. Therefore in order to build up detailed pH profiles for kI and kII, we investigated the initial rate of Orange II bleaching as a function of [H2O2] concentration in the range of 0.0003–0.0015 M at [Orange II] = 4×10−5 M in the pH range of 6–12. The hyperbolic dependencies of the rate vs. [H2O2] were analyzed in terms of eq 4 using four different routines: (i) by calculating the slope of a linear portion of the rate vs. [H2O2] plot at lower peroxide concentrations, which corresponds to kI, (ii) by fitting the experimental data to eq 4 using the non-linear least squares, and by linearizing the experimental data using the Lineweaver-Burk (iii) and Eadie-Hofstee (iv) routines.28 In all four cases, consistent values of kI and kII were obtained revealing the highest values for both rate constants at pH around 9 (Figures 5 and 2S). However, it should be mentioned that the Lineweaver-Burk and the Eadie-Hofstee routines provide higher values for kI by a factor of 1.5–1.7. The rate constants kI obtained using routine i were the closest to those determined previously at pH 7, 9, and 11 from the 3D plots with many more data points14 and therefore this particular set of data shown in Figure 4 was further used for the quantitative analysis. The data in Figure 5 demonstrate that 2e shows remarkable activity at pH 7.5–8.0 in terms of kI. This is of exceptional practical value because the rate constants kII for FeIII-TAMLs (and other artificial activators of peroxides) are usually larger than kI such that the latter controls the process time in water purification applications.5 The rule holds for 2e in the studies described here (Figure 2S).

Scheme 3.

General mechanism of catalysis by FeIII-TAML activators of peroxides.

Figure 5.

Rate constants kI calculated using i routine as a function of pH for activation of H2O2 by 2e (circles). Blue squares show data obtained previously from 3D regressions.15 The solid line is calculated using the best-fit parameters of eq 5. See text for details.

The pH profiles for kI in the range of 6–12 for FeIII-TAMLs of the first generation, such as in Figure 5, were rationalized in terms of Scheme 2 neglecting the second ionization of an aqua ligand of the 1 catalysts driven by K'a1 10 because this event was not observed at pH below 12. However, it must be taken into consideration for the 2 catalysts. This implies that six parallel pathways with the rate constants k1−k6 may contribute the overall kI pathway. Therefore, the expression for kI appears as eq 5 with the pathways k2 and k3 as well as k4 and k5 being kinetically indistinguishable.

| (5) |

There is no doubt that eq 5 with cubic terms in [H+] could be used to fit the data in Figure 4, because such asymmetric bell-shaped plots can be satisfactorily fitted using similar equations with just square terms in [H+].10, 11 This creates the concern that the calculated rate constants might not represent unique solutions. However, the three Ka values in eq 5 have been experimentally determined independently. Thus, confidence in the calculated rate constants can be increased if the best fit Kas are close in value to the experimentally numbers as reported below. Fitting of the data in Figure 5 to eq 5 was performed by allowing all variables to float as combined terms, i.e., the data were fitted to the equation (a1x3 + a2x2 + a3x + a4)/(x3 + b1x2 + b2x + b3). Then, the individual equilibrium constants were obtained by solving a system of three equations consisting of the three bi terms of the denominator. Those values were further used to calculate rate constants k1–k6 from the values of ai. It should be noted that for the kinetically indistinguishable pathways (k2 or k3, and k3 or k4), the rate constants were calculated by assuming that the corresponding counterpart equals zero. The thus-derived best-fit values for the equilibrium and the rate constants (M−1 s−1) are as follows: pKa1 = 8±1, pK'a1 = 10±1, pKa2 = 11.8±0.9, K1 = (5±5)×102, K2 = (2.0±0.4)×104, K3 ~ 1.2×108, K4 > 4.8×105, K5 = (7.6±1.7)×103, and K6~ 6.2×102. Importantly, there is a good agreement between the values of pKa1 and pK'a1 measured spectrophotometrically by the UV/Vis titration of 2e (Figure 4) and obtained by fitting the kinetic data. The pKa2 value for H2O2 (11.8) also agrees reasonably well with those reported in the literature (11.2–11.6).29 Note again that the rate constants for the kinetically indistinguishable pathways were estimated on the assumption that the corresponding counterpart is negligible, thus making the reported values of K2– K5 upper limits. While the calculated rate constants K1–K6 are high, it is worth noting that K3 is the largest. It exceeds the rate constant for formation of compound I from resting state horseradish peroxidase and H2O2 under optimal conditions (1.2×107 M−1 s−1).30

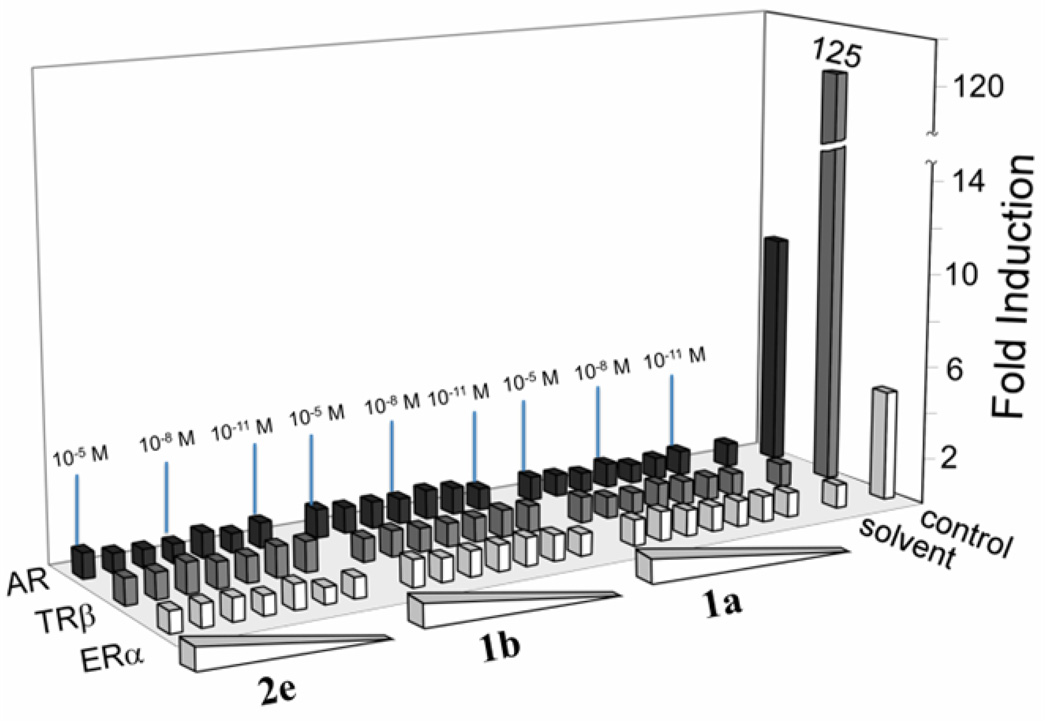

Assessing the Potential for Endocrine Disrupting Activity

Finally, because all chemists must learn how to pre-empt endocrine disruption in chemical products and processes in accordance with green chemistry principles, we began an exploration for possible endocrine disrupting activity by examining whether 1a,b or 2e activate transcription mediated by the human thyroid receptor (TRβ), human estrogen receptor (ERα), and rat androgen receptor (AR). The data in Figure 6 were obtained over a concentration range for each FeIII-TAML that include process conditions (1×10−8–1×10−5 M) and anticipated values for environmental receiving waters (1×10−11–1×10−9 M). The data show that none of the FeIII–TAML compounds induced reporter gene activity above what was observed by water alone, whereas the control ligands for each of the receptors induced reporter gene activity as expected. The results demonstrate that 1a,b and 2e do not activate transcription mediated by these nuclear hormone receptors, suggesting that they do not bind to the receptors. While endocrine disrupting effects can arise via numerous mechanisms,31 activation of nuclear hormone receptors, and particularly AR, ER and TR, is associated with many observed endocrine disruption effects. Thus, the inability of FeIII-TAML to activate these receptors is an important finding.

Figure 6.

Activation studies showing that FeIII-TAMLs do not activate the nuclear hormone receptors, human TRβ human ERα and rat AR. The abilities of solvent (H2O), control ligands [TRβ (triiodothyronine, 10 nM), ERα (17-β-estradiol, 10 nM), and AR (dihydrotestosterone, 10 nM)] and FeIII-TAMLs, 1a, 1b and 2e (1×10−5 M, 1×10−6 M, …, 1×10−11 M) to induce receptor-dependent transcription from reporter gene constructs were tested in transient transfection assays. The data presented are based on three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate (N = 9) (see Supporting Information).

In conclusion, this study shows that mechanistically monitored green oxidation catalyst design, focusing on fundamental properties such as the pKas of the catalyst’s aqua ligands, can be used to shift the pH-dependent reactivity profile such that the maximum reactivity moves nearer to the pH region of environmental waters where there is a pressing need for improved water purification technologies. FeIII-TAMLs of the second generation (2) have acquired much higher peroxide activation reactivity in the pH range of 7.5–8.0 than their 1 progenitors. In addition, catalysts 2d and 2e represent a design evolution that has succeeded in bringing about an active species changeover in the demetalation chemistry―while 2d is destroyed by H2PO4 −, the much stronger acid H3PO4 is needed to eject iron from 2e at a similar rate. Kinetic studies of 2e-catalyzed H2O2 bleaching of Orange II indicate the catalyst is the optimal peroxidase replica to date in terms of the speed of peroxide activation (KI) and further oxidation of the test dye (KII) making it all the more promising for use in the oxidative purification of contaminated waters.

This study also highlights what is nothing less than an ethical imperative for not only green but all chemists. Prior to commercial development, at best available standards, any new green chemical product or process should not contain or lead to an endocrine disruptor, or if the benefit is so great that ED activity must be accepted, there should be a strategy in place for mitigating the environmental consequences. To this end, we have taken initial steps toward exhibiting the kind of collaboration that will be needed to evaluate the endocrine disrupting potential of the 2 catalysts. Assays of the type presented here, in combination with others under development, should become routine analytical procedures, just as with elemental analysis and appropriate spectroscopic characterization, as a practical component of honoring Paul Anastas’ definition of green chemistry as “the design chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate the use and generation of hazardous substances”.32

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Support is acknowledged from the Heinz Endowments (T.J.C), the Charles E. Kaufman Foundation (T.J.C.), the R.K. Mellon Foundation (W.C.E.), the National Institutes of Environmental Health Sciences (B.B., 5R01-ES015849), the Norwegian Research Council (Miljø 2015: 181888), and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute for support of undergraduate researchers (C.T.T. and R.R.). We thank Roberto Gil for assistance with NMR and the NSF for NMR Instrumentation (CHE-0130903).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Scheme 1S; crystal structure data for 2f; the Eyring plot for the rate constants Kα for in interaction between 2e and H2PO4 −; Table with the extinction coefficients and Ka for 2e; pH profiles for the rate constants KI and KII calculated using the Eadie-Hofstee and Lineweaver-Burke routines for the 2e-catalyzed oxidation of Orange II; and raw data for luciferase assays. This material is free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Geneva: World Health Organization; Guidelines for Drinking Water Quality. (3rd ed.) 2008

- 2.U.S.GeologicalSurvey. WaterQuality. http://www.usgs.gov/science/science.php?term=1306.

- 3.Daughton CG. Compr. Anal. Chem. 2007;50:1–58. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Bourguignon J-P, Giudice LC, Hauser R, Prins GS, Soto AM, Zoeller RT, Gore AC. Endocr. Rev. 2009;30:293–342. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ryabov AD, Collins TJ. Adv. Inorg. Chem. 2009;61:471–521. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chanda A, Khetan SK, Banerjee D, Ghosh A, Collins TJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:12058–12059. doi: 10.1021/ja064017e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sen Gupta S, Stadler M, Noser CA, Ghosh A, Steinhoff B, Lenoir D, Horwitz CP, Schramm K-W, Collins TJ. Science. 2002;296:326–328. doi: 10.1126/science.1069297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shappell NW, Vrabel MA, Madsen PJ, Harrington G, Billey LO, Hakk H, Larsen GL, Beach ES, Horwitz CP, Ro K, Hunt PG, Collins TJ. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008;42:1296–1300. doi: 10.1021/es7022863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Banerjee D, Markley AL, Yano T, Ghosh A, Berget PB, Minkley EG, Jr, Khetan SK, Collins TJ. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006;45:3974–3977. doi: 10.1002/anie.200504511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghosh A, Mitchell DA, Chanda A, Ryabov AD, Popescu DL, Upham E, Collins GJ, Collins TJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:15116–15126. doi: 10.1021/ja8043689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Popescu D-L, Chanda A, Stadler MJ, Mondal S, Tehranchi J, Ryabov AD, Collins TJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:12260–12261. doi: 10.1021/ja805099e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.EPA. Website: http://www.epa.gov/safewater/consumer/2ndstandards.html.

- 13.Polshin V, Popescu D-L, Fischer A, Chanda A, Horner DC, Beach ES, Henry J, Qian Y-L, Horwitz CP, Lente G, Fabian I, Münck E, Bominaar EL, Ryabov AD, Collins TJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:4497–4506. doi: 10.1021/ja7106383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ellis WC, Tran CT, Denardo MA, Fischer A, Ryabov AD, Collins TJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:18052–18053. doi: 10.1021/ja9086837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meunier B. Biomimetic Oxidations Catalyzed by Transition Metal Complexes. London: Imperial College Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meunier B. Models of heme peroxidases and catalases. London: Imperial College Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marques HM. Dalton Transactions. 2007:4371–4385. doi: 10.1039/b710940g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perrin DD, Armarego WLF. Purification of Laboratory Chemicals. 3 ed. Oxford, New York: Pergamon Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chahbane N, Popescu D-L, Mitchell DA, Chanda A, Lenoir D, Ryabov AD, Schramm K-W, Collins TJ. Green Chem. 2007;9:49–57. [Google Scholar]

- 20.George P. Biochem. J. 1953;54:267–276. doi: 10.1042/bj0540267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grun F, Venkatesan RN, Tabb MM, Zhou C, Cao J, Hemmati D, Blumberg B. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:43691–43697. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206553200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blumberg B, Sabbagh W, Jr, Juguilon H, Bolado J, Jr, Van Meter CM, Ong ES, Evans RM. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3195–3205. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.20.3195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ember E, Rothbart S, Puchta R, van Eldik R. New J. Chem. 2009;33:34–49. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Theodoridis A, Maigut J, Puchta R, Kudrik EV, Van Eldik R. Inorg. Chem. 2008;47:2994–3013. doi: 10.1021/ic702041g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chanda A, Ryabov AD, Mondal S, Alexandrova L, Ghosh A, Hangun-Balkir Y, Horwitz CP, Collins TJ. Chem. Eur. J. 2006;12:9336–9345. doi: 10.1002/chem.200600630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ghosh A, Ryabov AD, Mayer SM, Horner DC, Prasuhn DE, Jr, Sen Gupta S, Vuocolo L, Culver C, Hendrich MP, Rickard CEF, Norman RE, Horwitz CP, Collins TJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:12378–12378. doi: 10.1021/ja0367344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith RM, Martell AE. Critical Stability Constants. Vol. 4. NY: Plenum Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fersht A. Structure and mechanism in protein science: a guide to enzyme catalysis and protein folding. NY: Freeman; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones CW. Applications of hydrogen peroxide and derivatives. Cambridge: The Royal Society of Chemistry; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dunford HB. Heme Peroxidases. NY, Chichester, Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gore AC. Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals: From Basic Research to Clinical Practice. Totowa, N. J.: Humana Press Inc.; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 32.EPA. Website: http://www.epa.gov/greenchemistry.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.