Abstract

Global energy balance in mammals is controlled by the actions of circulating hormones that coordinate fuel production and utilization in metabolically active tissues. Bone-derived osteocalcin, in its undercarboxylated, hormonal form, regulates fat deposition and is a potent insulin secretagogue. Here, we show that insulin receptor (IR) signaling in osteoblasts controls osteoblast development and osteocalcin expression by suppressing the Runx2 inhibitor Twist2. Mice lacking IR in osteoblasts have low circulating undercarboxylated osteocalcin and reduced bone acquisition due to decreased bone formation and deficient numbers of osteoblasts. With age, these mice develop marked peripheral adiposity and hyperglycemia accompanied by severe glucose intolerance and insulin resistance. The metabolic abnormalities in these mice are improved by infusion of exogenous undercarboxylated osteocalcin. These results indicate the existence of a bone-pancreas endocrine loop through which insulin signaling in the osteoblast ensures osteoblast differentiation and stimulates osteocalcin production, which in turn regulates insulin sensitivity and pancreatic insulin secretion to control glucose homeostasis.

INTRODUCTION

Management of constant energy supply in an environment of variable food intake is critical for the survival of all terrestrial species. To this end, mammals have evolved intricate networks of local and circulating factors that coordinate energy expenditure by communicating metabolic information between the major organs that produce, store, and utilize energy. The skeleton is a highly metabolic tissue and is increasingly recognized as an important player in the coordination of global energy utilization through its hormonal interactions with other tissues (Fukumoto and Martin, 2009; Lee and Karsenty, 2008). As an example, leptin is a well characterized hormone produced by adipocytes that influences insulin sensitivity (Yamauchi et al., 2001) and also regulates postnatal bone acquisition (Karsenty, 2006). It is now appreciated that leptin acts indirectly on bone by activating sympathetic nerves whose efferent outputs target β2-adrenergic receptors on osteoblasts to regulate their proliferation and differentiation (Ducy et al., 2000; Takeda et al., 2002). Up-regulation of sympathetic tone by leptin has also been shown to inhibit insulin secretion via a mechanism involving the osteoblast (Hinoi et al., 2008).

Several lines of circumstantial evidence suggest that insulin also impacts bone development and physiology by regulating osteoblast function. First, a functional insulin receptor (IR) is expressed by osteoblasts and exposure of primary osteoblasts or osteoblast-like cell lines to physiological levels of insulin increases bone anabolic markers including collagen synthesis (Pun et al., 1989; Rosen and Luben, 1983), alkaline phosphatase production (Kream et al., 1985), and glucose uptake (Ituarte et al., 1989). Second, patients with Type-1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) can develop early onset osteopenia or osteoporosis (Kemink et al., 2000; Thrailkill, 2000), and have an increased risk of fragility fracture (Janghorbani et al., 2006; Nicodemus and Folsom, 2001), as well as poor bone healing and regeneration following injury (Loder, 1988). Analogous bone abnormalities are observed in animal models of T1DM which also exhibit bone loss (Herrero et al., 1998; Verhaeghe et al., 1990) due to reduced bone formation (Goodman and Hori, 1984; Shires et al., 1981; Verhaeghe et al., 1992; Verhaeghe et al., 1990). Localized insulin delivery accelerates healing in these models by enhancing osteogenesis (Gandhi et al., 2005).

For the hormonal networks described above to function effectively, it is reasonable to suggest that signals emanating from the osteoblast should regulate the action of both insulin and leptin. Osteocalcin, a factor produced only by osteoblasts (Weinreb et al., 1990), is a good candidate to fulfill such a function (Lee et al., 2007). Similar to other hormones, osteocalcin is synthesized as pre-pro-osteocalcin which is processed into pro-osteocalcin in the endoplasmic reticulum. Before being secreted by osteoblasts, osteocalcin undergoes vitamin K-dependent carboxylation on 3 Gla residues which endows the molecule with high affinity for bone matrix. A small portion of osteocalcin remains undercarboxylated and is secreted into the circulation (Delmas et al., 1983). The undercarboxylated form of osteocalcin has been proposed to act as a hormone that links bone to other regulators of glucose homeostasis, including insulin and leptin (Hinoi et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2007).

Previous attempts to demonstrate a biological role for insulin in bone have been complicated by the potentially confounding presence of IGF-1R in osteoblasts (Fulzele et al., 2007), which activates intracellular signaling pathways common to those activated by insulin. To circumvent this problem and to directly examine the function of insulin signaling in bone, we engineered mice lacking IR specifically in osteoblasts (Ob-ΔIR). Here we show that mutant Ob-ΔIR mice accumulate less trabecular bone due to a failure of osteoblast maturation and decreased bone formation. With age, the Ob-ΔIR mice developed marked peripheral adiposity and insulin resistance accompanied by decreased circulating undercarboxylated osteocalcin. These metabolic abnormalities were improved by infusion of exogenous undercarboxylated osteocalcin. Our results suggest the existence of a bone-pancreas endocrine loop through which insulin signaling in the osteoblasts stimulates osteocalcin production, which in turn regulates pancreatic insulin secretion to control glucose homeostasis.

RESULTS

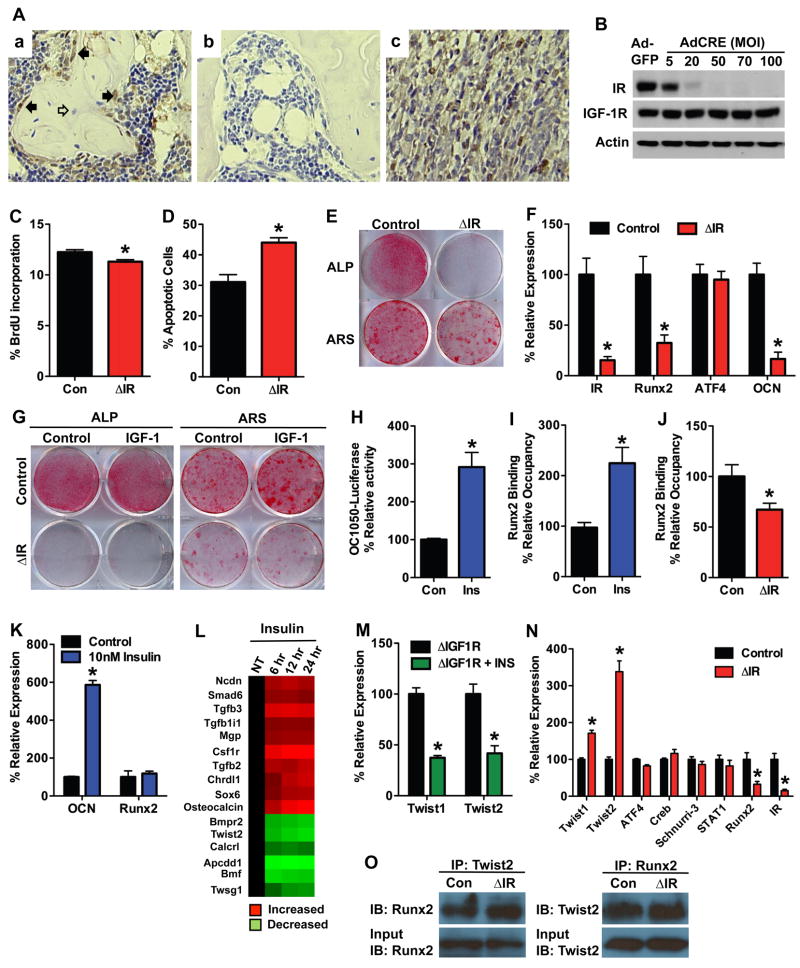

Insulin receptor (IR) is required for osteoblast proliferation, survival and differentiation

To begin to define specific actions of insulin in bone, we determined the cellular localization of IR in bone from mature wild-type mice. IR immunoreactivity was abundant in osteoblasts on trabecular bone surfaces but was low or absent in osteocytes (Figure 1A). We next assessed the requirement of IR for osteoblast proliferation, survival and differentiation in vitro. Primary osteoblasts were isolated from the calvarial bones of newborn IR floxed mice (Bruning et al., 1998) and infected with adenovirus expressing Cre recombinase to disrupt IR expression (hereafter referred to as ΔIR) or with adenovirus expressing GFP as a control (Figure 1B). ΔIR osteoblasts had reduced BrdU incorporation (Figure 1C) and increased sensitivity to apoptotic signals when examined by Annexin V staining (Figure 1D) compared to controls. In addition, differentiation was severely impaired in ΔIR osteoblasts, which accords with our previous studies that demonstrated that insulin treatment increased markers for osteoblast differentiation (Fulzele et al., 2007). Alkaline phosphatase and Alizarin Red staining following culture in osteogenic media (consisting of 10% serum which contains insulin, 10mM β-glycerol phosphate and 50μg/ml ascorbic acid) were significantly decreased in ΔIR osteoblasts when compared to controls (Figure 1E), and these deficiencies were accompanied by decreased expression of Runx2 and osteocalcin mRNA (Figure 1F). Exposure of IR deficient osteoblasts to exogenous IGF-1, which elicits downstream signaling events similar to insulin, did not improve alkaline phosphatase expression or the degree of matrix mineralization in ΔIR osteoblasts (Figure 1G).

Figure 1. Insulin receptor signaling promotes osteoblast differentiation.

(A) Immunohistochemical staining for insulin receptor (a) and an isotype control (b) in trabecular bone of the distal metaphysis. Filled arrows denote osteoblasts, open arrows denote osteocytes. Muscle was used as positive control (c). (B) Western Blot analysis of the insulin receptor expression in primary osteoblasts isolated from IRflox/flox mice after infection with adenovirus expressing Cre or GFP as a control. (C) Quantification of osteoblast proliferation by BrdU uptake in control and ΔIR osteoblasts. (D) Quantification of osteoblast apoptosis via Annexin V staining in control and ΔIR osteoblasts treated with 8ng/ml staurosporine. (E–G) Examination of osteoblast differentiation following the deletion of IR. (E) Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and Alizarin Red (ARS) staining after 7 and 14 days of differentiation, respectively. (F) RT-PCR analysis of IR, Runx2, ATF4, and Osteocalcin (OCN) expression after 7 days of differentiation. (G) ALP and ARS staining after culture in the presence or absence of 13nM IGF-1. (H) Osteocalcin promoter activity assessed in Mc3t3-E1 cells transfected with OC1050-Luc and treated with insulin for 6 hours. (I) ChIP analysis of Runx2 binding to the osteocalcin promoter after 6 hours of 10nM insulin treatment. (J) ChIP analysis of Runx2 binding to the osteocalcin promoter in control and ΔIR osteoblasts. (K) RT-PCR analysis of Osteocalcin (OCN) and Runx2 expression in primary osteoblasts treated with 10nM insulin for 6 hours. (L) Microarray analysis of insulin-regulated genes 4-fold over- or under-expressed and related to bone remodeling in ΔIGF-1R osteoblasts as identified by gene ontology analysis (see also Table S1). (M) Twist1 and Twist2 expression in ΔIGF-1R osteoblasts 24 hours after 10nM insulin treatment. (N) Expression of regulators of Runx2 activity in control and ΔIR osteoblasts after 7 days of differentiation. (O) Co-immunoprecipitation of Runx2 and Twist2 in control and ΔIR osteoblasts.

Insulin promotes osteoblast differentiation by suppressing Twist2

The profound defect in differentiation observed in osteoblasts lacking IR suggested that insulin signaling influences the expression or activity of a central regulator of the osteoblast differentiation program. In this regard, Runx2 seemed an obvious candidate since the expression of this factor was decreased in differentiating ΔIR osteoblasts (Figure 1F). Insulin treatment induced a 3-fold increase in osteocalcin promoter activity (Figure 1H) and a 2.5-fold increase in Runx2 occupancy of the OSE2 element when assessed by quantitative chromatin immunoprecipitation (Figure 1I). Further, Runx2 binding to the osteocalcin promoter was decreased in osteoblasts lacking the IR (Figure 1J). However, while insulin induced a 6-fold increase in osteocalcin mRNA expression, Runx2 expression was not affected (Figure 1K). These data indicated that insulin regulates Runx2 activity via an indirect mechanism.

To identify insulin-sensitive target genes that may influence Runx2 in osteoblasts we profiled RNA isolated from insulin treated ΔIGF-1R osteoblasts (used to eliminate the possibility of IGF-1R cross-activation by insulin) by microarray (Affymetrix Murine Genome 430–2.0). This analysis revealed 543 genes that were positively and negatively regulated by 4-fold or greater in response to 12 hours of insulin treatment (Supplementary Table 1), including 16 genes known to be involved in osteoblast differentiation (Figure 1L). Among these, Twist2, an established inhibitor of Runx2 activity (Bialek et al., 2004), was downregulated. Separate studies in primary osteoblasts confirmed the inhibition of Twist2 as well as Twist1 mRNA following treatment with insulin (Figure 1M). Conversely, disruption of IR upregulated Twist2 and to a lesser extent Twist1 mRNA but did not alter other established regulators of Runx2 activity (Figure 1N). Co-immunoprecipitation experiments demonstrated a decrease in Runx2 protein levels and an increase in the fraction of Runx2 bound by Twist2 in cells lacking IR (Figure 1O). Taken together, these data suggest that insulin signaling regulates osteoblast differentiation, in part, by suppression of the Runx2 inhibitor Twist2.

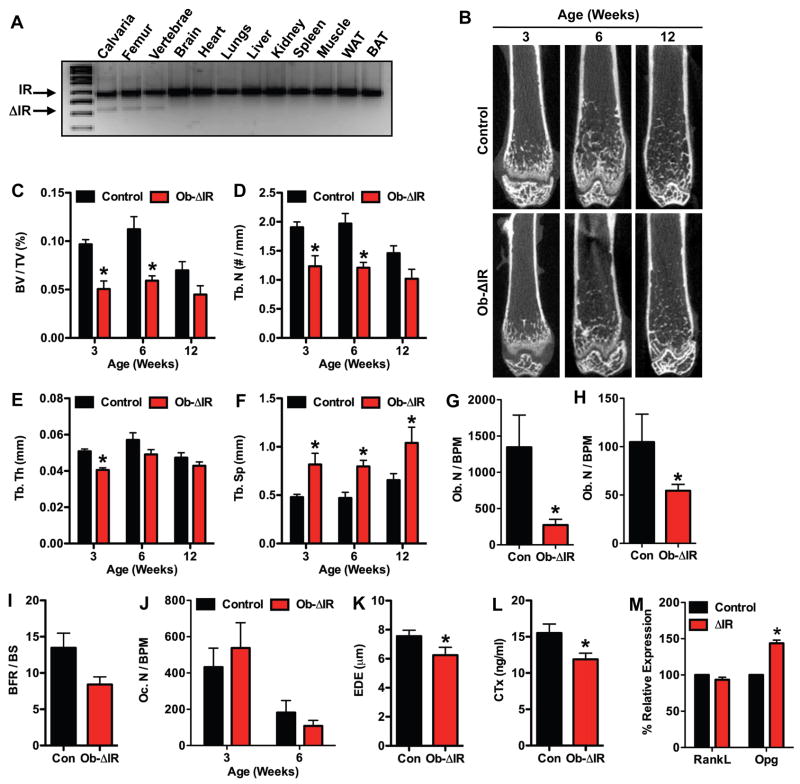

Mice lacking IR in osteoblasts have reduced postnatal bone acquisition

To determine the importance of insulin signaling in bone development in vivo, we analyzed the skeletal phenotype of mice lacking the IR in osteoblasts. Male progeny from matings between OC-CreTG/+ IRflox/flox and IRflox/flox mice (Bruning et al., 1998) with the genotype OC-CreTG/+ IRflox/flox (hereafter, referred to as Ob-ΔIR) were selected for detailed analysis. Allele specific PCR performed on DNA isolated from tissues of Ob-ΔIR mice revealed that recombination of IR alleles occurred only in skeletal tissues (i.e. calvaria, femur, and vertebrae) (Figure 2A). Male littermates lacking the OC-Cre transgene and, therefore, wild-type for IR gene function served as controls.

Figure 2. Insulin receptor signaling is necessary for postnatal bone acquisition.

(A) PCR analysis of insulin receptor (IR) allele recombination in tissues for Ob-ΔIR mice. (B–F) Quantitative micro-CT analysis of the distal femur in control and Ob-ΔIR mice at 3-, 6-, and 12-weeks of age (n=4–5mice). (B) Representative images. (C) Bone volume/tissue volume, BV/TV (%). (D) Trabecular number, Tb. N (no./mm), (E) Trabecular thickness, Tb. Th (μm). (F) Trabecular spacing, Tb. Sp (μm). (G–K) Static and Dynamic histomorphometric analysis of the distal femoral metaphysis in control and Ob-ΔIR mice at 3- and 6-weeks of age (n=5–7mice). (G) Osteoblast Number per bone perimeter, Ob. N/BPM (no./100mm) at 3-weeks of age. (H) Osteoblast Number per bone perimeter at 6 weeks of age. (I) Bone formation rate per bone surface, BFR/BS, mm3/cm2/yr. (J) Osteoclast number per bone perimeter, Oc. N/BPM (no./100mm) (K) Erosion Depth, EDE (μm) (L) Serum CTx (ng/ml). (M) RankL and Opg expression in control and ΔIR osteoblasts after 7 days of differentiation.

The loss of IR in osteoblasts dramatically impaired postnatal trabecular bone acquisition. Whereas control mice accumulated trabecular bone to maximal levels by 6 weeks, mice lacking IR failed to accumulate trabecular bone; trabecular bone volume (BV/TV) was decreased by more that 47% in Ob-ΔIR mice compared to controls at both 3- and 6-weeks of age (Figures 2B and C). This defect in bone acquisition was characterized by significant decreases in trabecular numbers (Tb. N, Figure 2D) and thickness (Tb. Th, Figure 2E), and significant increases in trabecular spacing (Tb. Sp, Figure 2F).

Static and dynamic histomorphometric analyses performed at 3- and 6-weeks of age showed that the decrease in bone volume in Ob-ΔIR mice was secondary to a reduction in the number of osteoblasts. Osteoblast numbers per bone perimeter (Ob. N/BPM) in Ob-ΔIR mice were decreased by 79% at 3-weeks of age (Figure 2G) and 47% at 6-weeks of age (Figure 2H) when compared to controls. This decrease in osteoblast numbers was accompanied by a 30% reduction in bone formation rate (BFR/BS, 13.46 ± 2.02 vs. 9.34 ± 0.92, mean ± SE, p = 0.06) at 6-weeks of age (Figure 2I). Osteoclast numbers per bone perimeter (Oc. N/BPM) were unchanged in Ob-ΔIR mice when compared to controls (Figure 2J). However, erosion depth was decreased at 3-weeks of age in Ob-ΔIR mice (Figure 2K), indicating a decrease in osteoclast activity. Consistent with this, the serum levels of CTx were significantly decreased (Figure 2L) in Ob-ΔIR mice and differentiating ΔIR osteoblasts expressed significantly more Opg than controls (Figure 2M). These histomorphometric data contrast to the phenotype of mice lacking the IGF-1R that have increased osteoblast numbers and more bone matrix which is undermineralized (Zhang et al., 2002). When considered together with our in vitro data, these results suggest that IR is required for normal postnatal bone acquisition, and that the bone phenotype in these mice is likely due to a failure of normal osteoblast differentiation resulting from increased Twist2 expression and a suppression of Runx2.

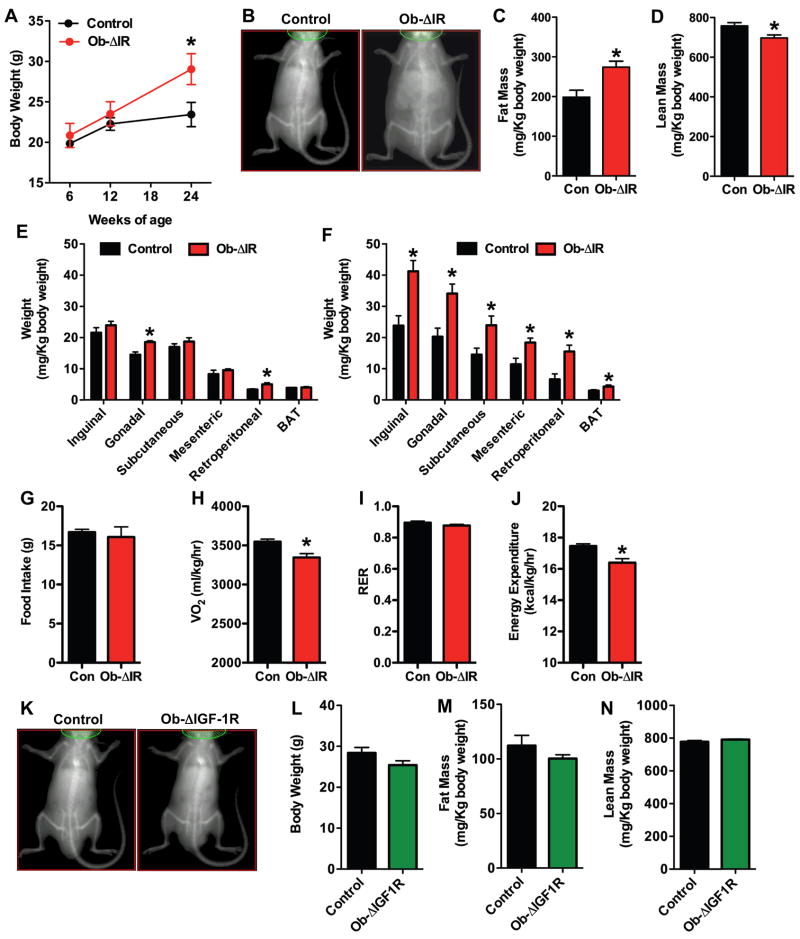

Mice lacking IR develop increased adiposity and insulin resistance

Ob-ΔIR mice had normal longitudinal growth but developed an unanticipated increase in total body mass relative to control littermates (Figures 3A and B). Measurements of body composition at 24-weeks by qMR revealed a 40% increase in fat mass (Figure 3C) and an 8% decrease in lean mass in Ob-ΔIR mice relative to controls (Figure 3D). At necropsy the weights of the major fat pads were increased by 12-weeks in Ob-ΔIR mice (Figure 3E) and were further increased at 24-weeks of age (Figure 3F). The accumulation of peripheral fat did not result from changes in feeding behavior as food intake, measured at 12-weeks, was similar in control and Ob-ΔIR mice (Figure 3G). Indirect calorimetry demonstrated that Ob-ΔIR mice had decreased rates of oxygen consumption compared with controls (VO2, Figure 3H), without a change in the respiratory exchange ratio (RER, Figure 3I). Thus, the decreased rate of oxidative metabolism resulted in overall decreased rates of energy expenditure (Figure 3J). By contrast, body weights (Figures 3K and 3L) and composition (Figures 3M and 3N) of mice lacking the IGF-1R in osteoblasts were similar to control littermates.

Figure 3. Ob-ΔIR mice, but not Ob-ΔIGF-1R mice, have increased peripheral adiposity.

(A–E) Assessment of body composition in control and Ob-ΔIR mice (n=5–7mice). (A) Body weight. (B) Representative DEXA images at 24-weeks. (C) Fat Mass by qMR. (D) Lean Mass by qMR. (E) Mass of individual fat pads at 12-weeks. (F) Mass of individual fat pads at 12-weeks. (G) Food intake over 4 days at 12-weeks (n=4). (H–I) Indirect calorimetry at 12-weeks (n=4). (H) VO2 (ml/kg/hr). (I) Respiratory exchange ratio (RER). (J) Energy expenditure (kcal/kg/hr). (K–N) Assessment of body composition in control and Ob-ΔIGF-1R mice at 24-weeks of age (n=5–11mice). (K) Representative DEXA images. (L) Body weight. (M) Fat mass by qMR. (N) Lean mass by qMR.

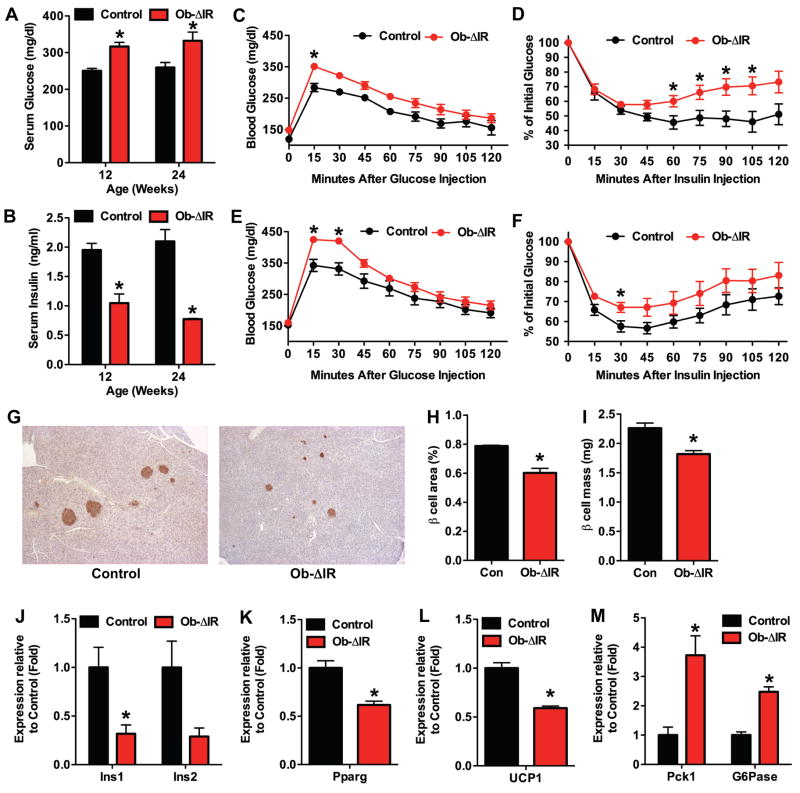

The peripheral adiposity in Ob-ΔIR mice suggested that the increase in body fat occurred secondary to alterations in glucose homeostasis and/or insulin dynamics. In accordance with this idea, non-fasting serum glucose levels were significantly increased in Ob-ΔIR mice (Figure 4A) while serum insulin (Figure 4B) was decreased. To assess total body sensitivity to glucose and insulin, we performed standard glucose tolerance test (GTT) and insulin tolerance test (ITT) at both the 12-week and 24-week time-points. Baseline, fasting-glucose concentrations were similar in Ob-ΔIR and control mice. However, glucose excursions in glucose-challenged Ob-ΔIR mice were significantly higher than controls (Figure 4C and 4E). In addition, insulin administration did not lower glucose concentrations to the extent seen in control mice (Figure 4D and 4F).

Figure 4. Ob-ΔIR mice are insulin insensitive and glucose intolerant.

Measurements of non-fasted serum glucose (A) and serum insulin (B) in 12- and 24-week old control and Ob-ΔIR mice (n=4–5mice). Glucose tolerance test after fasting overnight at 12-weeks (C) and 24-weeks (E) (n=4–6mice). (E) Insulin tolerance test after fasting for 4 hours at 12-weeks (D) and 24-weeks (F) (n=4–6mice). (G–I) Histomorphometric analysis of pancreatic β-cells in control and Ob-ΔIR mice (n=4–5mice). (G) Representative images of islets stained for insulin. (H) β-cell area. (I) β-cell mass. (J–M) qPCR in tissues isolated from control and Ob-ΔIR mice (n=3). (J) Ins1 and Ins2 expression in pancreas. (K) Pparg expression in white adipose. (L) UCP1 expression in brown adipose. (M) Pck1 and G6pase expression in the liver.

The lower circulating insulin levels in non-fasted Ob-ΔIR mice, together with their exaggerated glucose excursions (GTT) and insulin insensitivity (ITT), suggested the development of insulin resistance in the face of reduced insulin secretory reserves. In accordance with this scenario, β-cell area and mass were decreased at 12-weeks (data not shown) and 24-weeks in Ob-ΔIR mice when compared to controls (Figure 4G–I), and this was accompanied by reduced expression of Ins1 and Ins2 (Figures 4J). Additionally, the expression of gene markers for insulin sensitivity was reduced in white and brown adipose tissue, while genes associated with gluconeogenesis were enhanced in the liver (Figures 4K–O). Taken together, these results suggest that loss of insulin signaling in osteoblasts results in increased fat accumulation accompanied by both glucose intolerance and target tissue insulin resistance.

Metabolic dysregulation in Ob-ΔIR mice is caused by reduced undercarboxylated osteocalcin

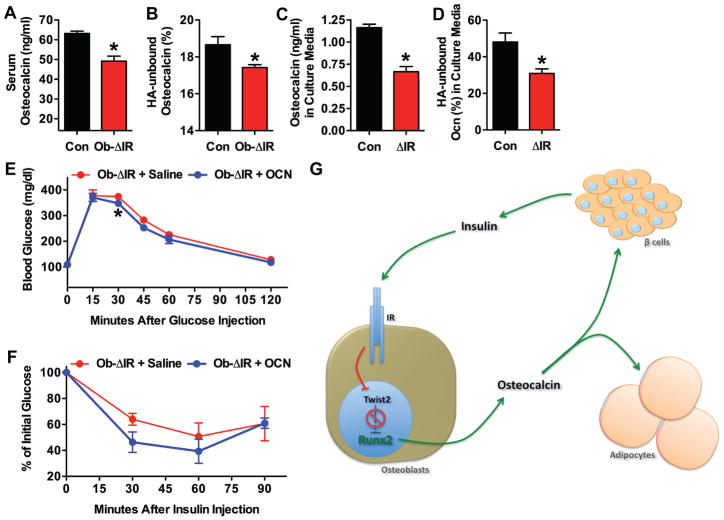

The accumulation of peripheral fat, glucose intolerance, and insulin resistance, together with decreased insulin levels in the Ob-ΔIR mice, are reminiscent of the alterations in serum biochemistry and body composition seen previously in osteocalcin deficient mice (Lee et al., 2007). Moreover, osteoblast-derived undercarboxylated osteocalcin is a potent secretogogue for insulin (Ferron et al., 2008). These observations, together with our current demonstration that insulin potently stimulates osteocalcin expression in osteoblasts, suggested the possibility that osteocalcin might function as a circulating factor responsible for the increased fat accumulation and changes in insulin sensitivity in the Ob-ΔIR mice. To investigate this possibility, we measured total and undercarboxylated osteocalcin in the serum of control and Ob-ΔIR mice. Total and undercarboxylated osteocalcin serum levels were decreased significantly in the Ob-ΔIR mice compared to controls (Figures 5A and 5B, respectively). Total and undercarboxylated osteocalcin levels were also lower in conditioned media of ΔIR osteoblasts than in that of controls (Fig. 5C and 5D, respectively), suggesting that the lower levels of undercarboxylated osteocalcin in Ob-ΔIR mice were not related to renal clearance (Delmas et al., 1983).

Figure 5. Undercarboxylated osteocalcin improves glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity in Ob-ΔIR mice.

Measurements of total (A) and undercarboxylated osteocalcin (B) in the serum of 24-week old control and Ob-ΔIR mice (n=5mice). (C) Total and (D) undercarboxylated osteocalcin in media conditioned by control and ΔIR osteoblasts. (E) Glucose tolerance test and (F) insulin tolerance test in Ob-ΔIR mice infused with saline or undercarboxylated osteocalcin (30ng/g BW/h) for 2 weeks (n=3). (G) Model for the regulation of bone acquisition and body composition by insulin. Insulin signaling stimulates osteoblast differentiation and osteocalcin expression by relieving Twist2’s suppression of Runx2. Undercarboxylated osteocalcin increases tissue insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion.

To provide additional evidence that osteocalcin deficiency underlies the metabolic disturbances in the Ob-ΔIR mice, we measured the effect of a two-week infusion of undercarboxylated osteocalcin on glucose and insulin sensitivity measured by GTT and ITT. When infused with undercarboxylated osteocalcin and challenged with glucose, Ob-ΔIR mice had blunted glucose excursions and more pronounced reductions in serum glucose following a bolus of insulin relative to controls, indicating an improved sensitivity to insulin (Figures 5E and F). Collectively, these results suggest a model in which insulin signaling in osteoblasts activates transcriptional events that promote osteoblast differentiation and control the production and bioavailability of osteocalcin. The undercarboxylated form of osteocalcin, in turn, acts as a circulating hormone to regulate fat accumulation and insulin production and sensitivity (Figure 5G).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we uncovered two previously unappreciated roles for insulin in bone that are both achieved by the ability of the hormone to activate a common osteoblast transcriptional pathway. First, insulin suppresses the Runx2 inhibitor Twist2, which promotes osteoblast differentiation necessary for normal bone formation. Second, insulin induces production of the insulin secretagogue osteocalcin, which influences glucose utilization. These results suggest the existence of a novel endocrine regulatory loop in which insulin signaling in the osteoblast controls postnatal bone development and simultaneously regulates insulin sensitivity and pancreatic insulin secretion to regulate glucose homeostasis.

Insulin regulates osteoblast function and postnatal bone acquisition

The reduced bone mass and osteoblast numbers in the Ob-ΔIR mice, together with the lower proliferation and differentiation capacity of IR deficient osteoblasts in vitro, demonstrate that insulin signaling is critical for osteoblast function. This bone phenotype is strikingly different from that observed in mice lacking the IGF-1R in osteoblasts, which exhibit normal or even elevated numbers of mature osteoblasts (Zhang et al., 2002). Transcriptional profiling and immunoprecipitation experiments conducted in insulin-treated ΔIR osteoblasts indicated that insulin signaling regulates osteoblast differentiation by suppression of Twist2, a known inhibitor of Runx2 (Bialek et al., 2004). Precisely how IR signaling is coupled to transcriptional control of osteoblast function deserves further study. A good candidate is the forkhead protein FoxO1 which is know to be downstream of IR and serves to suppress insulin action in many target tissues (Accili and Arden, 2004; Kitamura et al., 2002; Nakae et al., 2002; Nakae et al., 2003). FoxO1 activity is associated with decreased proliferation and increased sensitivity to apoptosis inducing signals (Paik et al., 2007), a phenotype identical to that observed in osteoblasts lacking IR, which should have increased FoxO1 activity. Unfortunately firm conclusions regarding potential IR/FoxO1 interactions in bone cannot be made due to the fact that a large percentage of mice lacking FoxO1 in osteoblasts die shortly after birth (Rached et al., 2009). However, the portion of mice lacking FoxO1 in osteoblasts that survive have increased glucose tolerance and increased insulin sensitivity, metabolic features opposite from the Ob-ΔIR mice described in this paper.

Our findings of reduced trabecular bone in the Ob-ΔIR mice contrast to previous reports of normal bone mass in a mouse globally deficient in IR (Irwin et al., 2006). In these mice, postnatal lethality due to ketoacidosis was genetically rescued by transgenic re-expression of the IR in the pancreas, liver, and brain (tTr-IRKO mice) (Okamoto et al., 2004). However, since bone volume in these mice was measured at a single time point (6 months) we suspected that changes in bone mass due to loss of the insulin receptor might have been missed, particularly since the changes observed in our Ob-IR deficient mice were most pronounced at early post-natal time points. Micro-CT measurements in these mice conducted by our laboratory revealed a reduced trabecular bone volume compared to control animals at 3-weeks of age (data not shown). Therefore, the loss of IR in osteoblasts in two mouse models created using different genetic strategies produced a remarkably similar bone phenotype, thus confirming the importance of IR in normal bone acquisition.

In addition to controlling osteocalcin gene transcription, insulin also appears to regulate posttranslational modification of osteocalcin since the proportion of undercarboxylated osteocalcin was decreased in both the conditioned media from IR-null differentiated osteoblasts and in serum from Ob-ΔIR mice. Neither of these events were observed in osteoblasts exposed to IGF-1, clearly indicating that insulin and not IGF-1 is a primary regulator of osteocalcin mRNA expression and possibly post-translational processing. Also, whereas loss of IGF-1R in osteoblasts could be partially rescued by insulin (Fulzele et al., 2007), osteoblasts lacking IR were not rescued by IGF-1. Together, these results indicate that signals derived from the IR are even more critical for osteoblast development than those generated by IGF-1 and cannot be compensated by other factors at least during early bone development.

Insulin stimulates osteocalcin to regulate glucose homeostasis

The metabolic phenotype in mice lacking IR in their osteoblasts suggests the development of tissue resistance to insulin coupled with deficient insulin secretory reserves, a phenotype virtually identical to that observed in osteocalcin deficient mice (Lee et al., 2007). These observations fit with an emerging body of data which implicate circulating undercarboxylated osteocalcin as a bone-derived hormone that helps coordinate glucose homeostasis and body composition (Lee and Karsenty, 2008). Thus, osteocalcin induces insulin production by pancreatic β-cells and adiponectin secretion from adipocytes (Lee et al., 2007). Moreover, osteocalcin increased basal and insulin stimulated glucose transport in adipocytes (Ferron et al., 2008). The current study identifies insulin as a critical regulator of osteocalcin production. Levels of osteocalcin were reduced in serum of Ob-ΔIR knockout mice and medium conditioned by their osteoblasts. Moreover, the observation that infusion of osteocalcin improved glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity strongly suggests that the metabolic and body composition alterations in the Ob-ΔIR mice are due to the loss of insulin’s ability to stimulate osteocalcin expression in osteoblasts.

The hormonal activity of osteocalcin with respect to its secretion and actions on fat and pancreas appear to be regulated by post-translational γ-carboxylation which we predict is also controlled by insulin. In this regard, the percentage of circulating undercarboxylated osteocalcin was decreased in the Ob-ΔIR mice. We anticipated that insulin might control γ-carboxylation of osteocalcin by regulating osteotesticular protein tyrosine phosphatase (OST-PTP), the product of the Esp gene known to be required for osteocalcin carboxylation (Lee et al., 2007). Thus, Esp-deficient mice produce more undercarboxylated osteocalcin and exhibit increased insulin secretion, hypoglycemia, and increased insulin sensitivity, whereas overexpression of Esp produces the opposite phenotype. However, it should be noted that a homolog for the Esp gene has so far not been identified in humans. Therefore, other genes and/or mechanisms, such as vitamin K-dependent γ-carboxylase, are likely to play a role in the regulation of osteocalcin γ-carboxylation by insulin.

While additional studies will be required to fully establish the exact physiological relevance of our findings, several existing studies in humans are consistent with the insulin-osteocalcin endocrine loop suggested here. Serum levels of undercarboxylated osteocalcin correlate with improved glucose tolerance in men (Hwang et al., 2009). Moreover, serum osteocalcin concentrations have been found to be inversely associated with blood markers of dysmetabolic phenotype and measures of adiposity (Pittas et al., 2009). On a more fundamental level, our work supports a growing body of data that indicates that the skeleton plays an integrative role in regulating energy expenditure and fuel utilization (Karsenty, 2006).

In summary, the results presented in this paper suggest the existence of a novel bone-pancreas feedback loop through which insulin signaling in the osteoblast promotes postnatal bone acquisition and simultaneously stimulates osteocalcin production, which in turn, regulates pancreatic insulin secretion to control glucose homeostasis. These observations should have immediate impact on our understanding of the global control of energy balance and theoretically guide new approaches for treatment of bone disease and diabetes.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animal models

All procedures involving mice were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Alabama at Birmingham and Johns Hopkins University. Mice lacking IR in osteoblasts were generated by crossing osteocalcin-Cre (OC-Cre) transgenic mice (Zhang et al., 2002) with IRflox/flox mice (Bruning et al., 1998). The following primer pairs which amplify exons 3–5 were used to assess tissue-specific recombination: 5′-GCTGCACAGCTGAAGGCCTGT-3′ and 5′-CTCCTCGAATCAGATGTAGCT-3′. Ob-ΔIGF-1R mice have been described previously (Zhang et al., 2002). Genotyping strategies are available upon request.

Culture of primary osteoblasts

Osteoblasts were isolated from calvaria of newborn mice by serial digestion in 1.8 mg/ml of collagenase. For in vitro deletion of the IR and IGF-1R, osteoblasts containing floxed alleles were infected with adenovirus encoding Cre recombinase or green fluorescent protein (Vector Biolabs) as previously described (Fulzele et al., 2007). Infection with 100 MOI was used in all experiments. Osteoblast differentiation was induced by supplementing αMEM media with 10% serum (which contains insulin), 10mM β-glycerol phosphate and 50μg/ml Ascorbic Acid. Alkaline phosphatase and Alizarin Red S staining were carried out according to standard techniques.

Gene expression studies

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol, reverse transcribed using iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad) and amplified by real-time PCR using SYBR GREEN PCR Master Mix (Bio-Rad). Primer sequences were from PrimerBank (http://pga.mgh.harvard.edu/primerbank/index.html). For microarray analysis, RNA was hybridized to Affymetrix Murine Genome 430-2.0 Array chips and subsequently analyzed at the Microarray Core Facility at University of Alabama at Birmingham. Data have been deposited in NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus (Accession number GSE21710). Antibodies for IR, IGF-1R, and Twist2 were obtained from Santa Cruz. Mc3t3-E1 cells were transfected with the OC1050-Luc using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Chromatin immunoprecipitation was performed using the Magna ChIP A kit (Millipore) with a Runx2 antibody obtained from MBL International.

Imaging and histomorphometry

Male control and Ob-ΔIR mice were sacrificed at the indicated age and bone volume in the distal femoral metaphysis was assessed using a desktop microtomographic imaging system (MicroCT40; Scanco Medical). Histological analyses, using a semi-automatic method (Osteoplan II, Kontron) were carried out on 3 and 6 week old mice injected with 1% calcein (w/v) 3 and 2 days prior to sacrifice, and 5 and 3 days prior to sacrifice, respectively (Zhang et al., 2002). Histomorphometric parameters follow the recommended nomenclature of the American Society of Bone and Mineral Research (Parfitt et al., 1987). Body composition was measured by DEXA (Lunar PIXImus II GE Healthcare) and qMR (3-in-1 Composition Analyzer, Echo Medical Systems) at 24-weeks of age. Pancreata were fixed and stained, and islet morphometry was performed as previously described (Hussain et al., 2006). IR expression was examined in mouse long bones using an antibody from Upstate Biotechnology after tissue was fixed in 10% buffered formalin, decalcified in 10% Na2EDTA, paraffin embedded, and then processed for immuno-staining according to standard techniques.

Metabolic studies and bioassays

For glucose tolerance test, glucose (1.5 g/kg BW) was injected IP after an overnight fast. For insulin tolerance test, mice were fasted for 4 hr and then injected IP with insulin (0.2 U/kg BW). Glucose was measured using a Glucose 201 analyzer (Hemocue, Lake Forest, CA, USA). For serum chemistries, insulin and glucose were measured with the Ektachem DT II System (Johnson & Johnson Clinical Diagnostics). Indirect calorimetry was conducted in a open-flow indirect calorimeter (Oxymax Equal Flow System; Columbus Instruments). Calorimetry, daily body weight and daily food intake data were acquired during a 4-experimental period. Data from the first 3 days was used to confirm acclimation to the calorimetry chamber, and the fourth day was used for analyses. Rates of oxygen consumption (VO2, ml/kg/hr) and carbon dioxide production (VCO2) were measured for each chamber every 8 minutes throughout the study. Respiratory exchange ratio (RER = VCO2/VO2) was calculated by Oxymax software (v. 4.02) to estimate relative oxidation of carbohydrate (RER = 1.0) versus fat (RER approaching 0.7), not accounting for protein oxidation. Energy expenditure was calculated as EE = VO2 × (3.815 + (1.232 × RER)) (Lusk, 1928), and normalized for subject body mass (kcal/kg/hr). Osteocalcin levels were measured by IRMA assay (Immunotopics). Hydroxyapatite resin, which binds the carboxylated form, was used to assess percentages of carboxylated and undercarboxylated osteocalcin (Lee et al., 2007). Bacterially produced mouse recombinant undercarboxylated osteocalcin or saline control was infused at 30ng/g BW/h using Alzet mini-osmotic pumps implanted s.c. (Ferron et al., 2008)

Statistics

All results are presented as means ± standard errors of the mean. Statistical analyses were performed using unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t or ANOVA tests followed by post hoc tests. In all figures, * ≤0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the assistance of the Small Animal Phenotyping Core and Metabolism Core Laboratory at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. We thank Dr. D. Accili for providing the tTR-IRKO mice and Dr. M. Bouxsein for assistance in analyzing the skeletal phenotype by micro-CT. We also thank Drs. T. Nagy and T. Garvey for helpful suggestions during the completion of this work. Support was provided by a Merit Review Grant from the Veterans Administration (T.C) and grants from the NIH (M.H., DK081472), the Baltimore Diabetes Research and Training Center (M.H., DK079637), and DFG (J.C., Br1492/7-1). Dr. Clemens is also the recipient of a Research Career Scientist Award from the Veterans Administration.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Accili D, Arden KC. FoxOs at the crossroads of cellular metabolism, differentiation, and transformation. Cell. 2004;117:421–426. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00452-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bialek P, Kern B, Yang X, Schrock M, Sosic D, Hong N, Wu H, Yu K, Ornitz DM, Olson EN, et al. A twist code determines the onset of osteoblast differentiation. Dev Cell. 2004;6:423–435. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00058-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruning JC, Michael MD, Winnay JN, Hayashi T, Horsch D, Accili D, Goodyear LJ, Kahn CR. A muscle-specific insulin receptor knockout exhibits features of the metabolic syndrome of NIDDM without altering glucose tolerance. Mol Cell. 1998;2:559–569. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80155-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delmas PD, Wilson DM, Mann KG, Riggs BL. Effect of renal function on plasma levels of bone Gla-protein. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1983;57:1028–1030. doi: 10.1210/jcem-57-5-1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducy P, Amling M, Takeda S, Priemel M, Schilling AF, Beil FT, Shen J, Vinson C, Rueger JM, Karsenty G. Leptin inhibits bone formation through a hypothalamic relay: a central control of bone mass. Cell. 2000;100:197–207. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81558-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferron M, Hinoi E, Karsenty G, Ducy P. Osteocalcin differentially regulates beta cell and adipocyte gene expression and affects the development of metabolic diseases in wild-type mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:5266–5270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711119105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukumoto S, Martin TJ. Bone as an endocrine organ. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2009;20:230–236. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulzele K, DiGirolamo DJ, Liu Z, Xu J, Messina JL, Clemens TL. Disruption of the insulin-like growth factor type 1 receptor in osteoblasts enhances insulin signaling and action. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:25649–25658. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700651200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi A, Beam HA, O’Connor JP, Parsons JR, Lin SS. The effects of local insulin delivery on diabetic fracture healing. Bone. 2005;37:482–490. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman WG, Hori MT. Diminished bone formation in experimental diabetes. Relationship to osteoid maturation and mineralization. Diabetes. 1984;33:825–831. doi: 10.2337/diab.33.9.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrero S, Calvo OM, Garcia-Moreno C, Martin E, San Roman JI, Martin M, Garcia-Talavera JR, Calvo JJ, del Pino-Montes J. Low bone density with normal bone turnover in ovariectomized and streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Calcif Tissue Int. 1998;62:260–265. doi: 10.1007/s002239900427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinoi E, Gao N, Jung DY, Yadav V, Yoshizawa T, Myers MG, Jr, Chua SC, Jr, Kim JK, Kaestner KH, Karsenty G. The sympathetic tone mediates leptin’s inhibition of insulin secretion by modulating osteocalcin bioactivity. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:1235–1242. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200809113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain MA, Porras DL, Rowe MH, West JR, Song WJ, Schreiber WE, Wondisford FE. Increased pancreatic beta-cell proliferation mediated by CREB binding protein gene activation. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:7747–7759. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02353-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang YC, Jeong IK, Ahn KJ, Chung HY. The uncarboxylated form of osteocalcin is associated with improved glucose tolerance and enhanced beta-cell function in middle-aged male subjects. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2009;25:768–772. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin R, Lin HV, Motyl KJ, McCabe LR. Normal bone density obtained in the absence of insulin receptor expression in bone. Endocrinology. 2006;147:5760–5767. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ituarte EA, Halstead LR, Iida-Klein A, Ituarte HG, Hahn TJ. Glucose transport system in UMR-106-01 osteoblastic osteosarcoma cells: regulation by insulin. Calcif Tissue Int. 1989;45:27–33. doi: 10.1007/BF02556657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janghorbani M, Feskanich D, Willett WC, Hu F. Prospective study of diabetes and risk of hip fracture: the Nurses’ Health Study. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1573–1578. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karsenty G. Convergence between bone and energy homeostases: leptin regulation of bone mass. Cell Metab. 2006;4:341–348. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemink SA, Hermus AR, Swinkels LM, Lutterman JA, Smals AG. Osteopenia in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus; prevalence and aspects of pathophysiology. J Endocrinol Invest. 2000;23:295–303. doi: 10.1007/BF03343726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura T, Nakae J, Kitamura Y, Kido Y, Biggs WH, 3rd, Wright CV, White MF, Arden KC, Accili D. The forkhead transcription factor Foxo1 links insulin signaling to Pdx1 regulation of pancreatic beta cell growth. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1839–1847. doi: 10.1172/JCI200216857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kream BE, Smith MD, Canalis E, Raisz LG. Characterization of the effect of insulin on collagen synthesis in fetal rat bone. Endocrinology. 1985;116:296–302. doi: 10.1210/endo-116-1-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee NK, Karsenty G. Reciprocal regulation of bone and energy metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2008;19:161–166. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee NK, Sowa H, Hinoi E, Ferron M, Ahn JD, Confavreux C, Dacquin R, Mee PJ, McKee MD, Jung DY, et al. Endocrine regulation of energy metabolism by the skeleton. Cell. 2007;130:456–469. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loder RT. The influence of diabetes mellitus on the healing of closed fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988:210–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lusk G. The elements of the science of nutrition. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1928. [Google Scholar]

- Nakae J, Biggs WH, 3rd, Kitamura T, Cavenee WK, Wright CV, Arden KC, Accili D. Regulation of insulin action and pancreatic beta-cell function by mutated alleles of the gene encoding forkhead transcription factor Foxo1. Nat Genet. 2002;32:245–253. doi: 10.1038/ng890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakae J, Kitamura T, Kitamura Y, Biggs WH, 3rd, Arden KC, Accili D. The forkhead transcription factor Foxo1 regulates adipocyte differentiation. Dev Cell. 2003;4:119–129. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00401-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicodemus KK, Folsom AR. Type 1 and type 2 diabetes and incident hip fractures in postmenopausal women. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1192–1197. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.7.1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto H, Nakae J, Kitamura T, Park BC, Dragatsis I, Accili D. Transgenic rescue of insulin receptor-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:214–223. doi: 10.1172/JCI21645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paik JH, Kollipara R, Chu G, Ji H, Xiao Y, Ding Z, Miao L, Tothova Z, Horner JW, Carrasco DR, et al. FoxOs are lineage-restricted redundant tumor suppressors and regulate endothelial cell homeostasis. Cell. 2007;128:309–323. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parfitt AM, Drezner MK, Glorieux FH, Kanis JA, Malluche H, Meunier PJ, Ott SM, Recker RR. Bone histomorphometry: standardization of nomenclature, symbols, and units. Report of the ASBMR Histomorphometry Nomenclature Committee. J Bone Miner Res. 1987;2:595–610. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650020617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittas AG, Harris SS, Eliades M, Stark P, Dawson-Hughes B. Association between serum osteocalcin and markers of metabolic phenotype. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:827–832. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pun KK, Lau P, Ho PW. The characterization, regulation, and function of insulin receptors on osteoblast-like clonal osteosarcoma cell line. J Bone Miner Res. 1989;4:853–862. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650040610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rached MT, Kode A, Silva BC, Jung DY, Gray S, Ong H, Paik JH, Depinho RA, Kim JK, Karsenty G, et al. FoxO1 expression in osteoblasts regulates glucose homeostasis through regulation of osteocalcin in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009 doi: 10.1172/JCI39901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen DM, Luben RA. Multiple hormonal mechanisms for the control of collagen synthesis in an osteoblast-like cell line, MMB-1. Endocrinology. 1983;112:992–999. doi: 10.1210/endo-112-3-992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shires R, Teitelbaum SL, Bergfeld MA, Fallon MD, Slatopolsky E, Avioli LV. The effect of streptozotocin-induced chronic diabetes mellitus on bone and mineral homeostasis in the rat. J Lab Clin Med. 1981;97:231–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda S, Elefteriou F, Levasseur R, Liu X, Zhao L, Parker KL, Armstrong D, Ducy P, Karsenty G. Leptin regulates bone formation via the sympathetic nervous system. Cell. 2002;111:305–317. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01049-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrailkill KM. Insulin-like growth factor-I in diabetes mellitus: its physiology, metabolic effects, and potential clinical utility. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2000;2:69–80. doi: 10.1089/152091599316775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhaeghe J, Suiker AM, Visser WJ, Van Herck E, Van Bree R, Bouillon R. The effects of systemic insulin, insulin-like growth factor-I and growth hormone on bone growth and turnover in spontaneously diabetic BB rats. J Endocrinol. 1992;134:485–492. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1340485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhaeghe J, van Herck E, Visser WJ, Suiker AM, Thomasset M, Einhorn TA, Faierman E, Bouillon R. Bone and mineral metabolism in BB rats with long-term diabetes. Decreased bone turnover and osteoporosis. Diabetes. 1990;39:477–482. doi: 10.2337/diab.39.4.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinreb M, Shinar D, Rodan GA. Different pattern of alkaline phosphatase, osteopontin, and osteocalcin expression in developing rat bone visualized by in situ hybridization. J Bone Miner Res. 1990;5:831–842. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650050806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi T, Kamon J, Waki H, Terauchi Y, Kubota N, Hara K, Mori Y, Ide T, Murakami K, Tsuboyama-Kasaoka N, et al. The fat-derived hormone adiponectin reverses insulin resistance associated with both lipoatrophy and obesity. Nat Med. 2001;7:941–946. doi: 10.1038/90984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Xuan S, Bouxsein ML, von Stechow D, Akeno N, Faugere MC, Malluche H, Zhao G, Rosen CJ, Efstratiadis A, et al. Osteoblast-specific knockout of the insulin-like growth factor (IGF) receptor gene reveals an essential role of IGF signaling in bone matrix mineralization. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:44005–44012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208265200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.