Abstract

We previously established an Escherichia coli strain capable of re-circularizing linear plasmid DNA by expressing the Mycobacterium tuberculosis Ku (Mt-Ku) and Mycobacterium tuberculosis ligase D (Mt-LigD) proteins from the E.coli chromosome. Repair was predominately mutagenic due to deletions at the termini. We hypothesized that these deletions could be due to a nuclease activity of Mt-LigD that was previously detected in vitro. Mt-LigD has three domains: an N-terminal polymerase domain (PolDom), a central domain with 3′-phosphoesterase and nuclease activity and a C-terminal ligase domain (LigDom). We generated bacterial strains expressing Mt-Ku and mutant versions of Mt-LigD. Plasmid re-circularization experiments in bacteria showed that the PolDom alone had no re-circularization activity. However, an increase in the total and accurate repair was found when the central domain was deleted. This provides further evidence that this central domain does have nuclease activity that can generate deletions during repair. Deletion of only the PolDom of Mt-LigD resulted in a complete loss of accurate repair and a significant reduction in total repair. This is in agreement with published in vitro work indicating that the PolDom is the major Mt-Ku-binding site. Interestingly, the LigDom alone was able to re-circularize plasmid DNA but only in an Mt-Ku-dependent manner, suggesting a potential second site for Ku–LigD interaction. This work has increased our understanding of the mutagenic repair by Mt-Ku and Mt-LigD and has extended the in vitro biochemical experiments by examining the importance of the Mt-LigD domains during repair in bacteria.

Introduction

Non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) is the primary double-strand break (DSB) repair pathway in mammalian cells and is complex involving numerous proteins that bind, modify and ligate the DNA termini (1). Cells that lack components of NHEJ are more sensitive to DNA damaging agents, such as ionizing radiation (1). Prior to 2001, NHEJ was thought to only exist in eukaryotes, with homologous recombination repairing DSBs in prokaryotes. However, the existence of prokaryote Ku-dependent NHEJ in a subset of bacteria was realized with the identification of operons expressing homologs of the mammalian Ku and ligases (2–4). Examples include Bacillus subtilis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Mycobacterium smegmatis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The bacterial species with Ku-dependent NHEJ tend to have dormant phases in their life cycle: slow growth, periods with no growth or spore formation. This prokaryote DSB repair mechanism is therefore believed to be important for survival during these dormant phases, when homologous recombination cannot be used to accurately repair DSBs. In fact, loss of this pathway has been found to decrease B.subtilis spore resistance to desiccation, ultraviolet and ionizing radiation (5), while M.smegmatis has shown a preference for NHEJ to repair breaks caused by ionizing radiation and desiccation during stationary phase (6). More recently, E.coli, which do not encode a Ku-like protein, were found to perform end-joining repair and ligase A was implicated in this mechanism (7). This repair was not greater, however, in stationary phase cells compared to exponential cells, and so the authors postulate that this pathway is not just for use when homologous recombination is not functioning (7).

Work in yeast (8) and E.coli (9) demonstrated that M.tuberculosis NHEJ requires a minimum of two proteins: Ku and an adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-dependent ligase (Mt-LigD). The bacterial Ku contains the conserved domain that forms the center of the larger eukaryote Ku proteins (2). This section of the eukaryote Ku is important for dimerization and DNA binding (2,10). Bacteria expressing prokaryote Ku also express multiple ATP-dependent ligases. M.tuberculosis expresses three (ligase B, C and D), but only Mt-LigD is expressed from an operon with Mycobacterium tuberculosis Ku (Mt-Ku) (11). The presence of the other ATP-dependent ligases in bacteria may be related to their roles in DNA metabolism, such as repair, replication or recombination (12). Work in M.smegmatis has demonstrated that ligase C acts as a backup enzyme to ligase D in Ku-dependent NHEJ (13) and ligation of DSBs by Lig C2 and Lig C3 of Agrobacterium tumefaciens was stimulated by bacterial Ku (14).

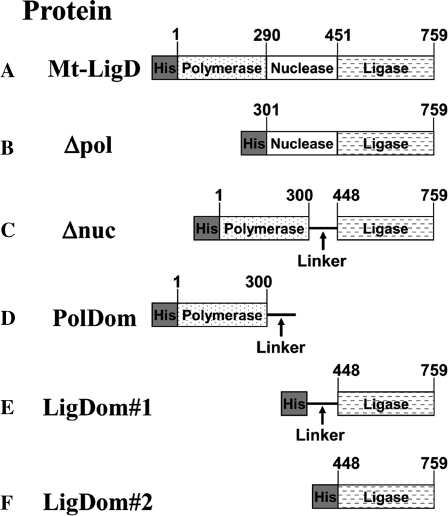

Mt-LigD has three distinct domains (Figure 1) (15,16) and each domain possesses individual activities that participate in DNA end processing or DNA ligation. The N-terminal domain, also known as the polymerase domain (PolDom), has been shown to have terminal transferase activity, DNA-dependent RNA primase and DNA-dependent DNA/RNA gap-filling polymerase functions (8,11,15–17). The central domain (NucDom) was initially identified as a potential nuclease by protein structure prediction (3,4). Mt-LigD has also been shown to have 3′–5′ single-stranded DNA exonuclease activity that requires magnesium or manganese, and this activity was eliminated by a point mutation in the nuclease domain (NucDom) (H373A) (8). Others have demonstrated that the NucDom of ligase D from P.aeruginosa has 3′-ribonuclease and 3′-phosphatase activity (18) and have so named this domain a phosphoesterase domain. It is likely that the Mt-LigD central domain also has similar nucleolytic activities, as the NucDom of M.tuberculosis has homology to the NucDom of P.aeruginosa. The C-terminal domain of Mt-LigD is the ligase domain (LigDom) and is an active adenyltransferase, catalyzing nick sealing in double-stranded DNA (8,11,15–17). By expressing and purifying each domain of Mt-LigD, in vitro work revealed the ability of the PolDom and LigDom to function independently and identified the PolDom as the Mt-Ku-binding domain (8,15). Mt-Ku therefore binds to DNA termini and is believed to recruit Mt-LigD through the PolDom (15). Mt-Ku also stimulates the activity of all three domains of Mt-LigD (15).

Fig. 1.

Fusion proteins of the Mt-LigD domains. The coding sequence of the wild-type Mt-LigD (protein A) was used to generate mutants (B–F) that are fusion proteins of the different domains of Mt-LigD. See Materials and methods for construction details. A linker [arg-gly-(thr-gly-ser)4-met-gly-leu] was added between the PolDom and LigDom to allow flexibility of these domains in the absence of the NucDom.

We have successfully generated an E.coli model of heterologous mycobacterial NHEJ that allows investigations into the interaction between Mt-Ku and Mt-LigD in bacteria that do not have a Ku-dependent end-joining mechanism. Since the Mt-Ku and Mt-LigD proteins are only expressed when arabinose is added to the culture, our model is able to distinguish Ku-dependent repair above the low background from the host end-joining system. This model previously confirmed that the repair of linearized plasmid DNA requires the presence of both Mt-Ku and Mt-LigD and excluded the involvement of RecA and RecB in this repair mechanism (9). During the analysis of the repair products from this model, it was revealed that the products were predominately inaccurate and contained deletions (9). This differs from results obtained from other groups in studies using M.smegmatis, and following expression of Mt-Ku and Mt-LigD in yeast, where repair products were also found to contain insertions (8,13,19). This difference suggests that other mycobacterial proteins may be required for correct processing or timely DNA ligation to prevent extensive deletions. Previous studies with M.smegmatis (19) have suggested that there is a mycobacterium template-dependent polymerase that also functions in a Ku-dependent mechanism to introduce insertions, independent of the PolDom of Mt-LigD. We hypothesized that in our model, the NucDom within Mt-LigD contributes to deletions in the repair products. We, therefore, generated E.coli strains expressing Mt-Ku and Mt-LigD deleted in the central domain. This easily manipulated model is also useful to examine the interaction of Mt-Ku and the domains of the Mt-LigD in bacteria. We also created Mt-LigD mutants deleted in only the PolDom, or the PolDom and NucDom, to determine whether repair was possible in the absence of domains known in vitro to bind Mt-Ku. Using this model, we have extended the previous in vitro experiments and enhanced our understanding of Mt-Ku and Mt-LigD.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains

A wild-type E.coli strain [BW35-Hfr KL16(PO-45) thi-1 relA1 spoT1 e14− λ−], previously obtained from Dr Susan S. Wallace (University of Vermont, Burlington, VT, USA), provides the background for the strains generated in this work. Previously developed strains, BWKuLig#2, BWLig and BWKu (9) express Mt-Ku and Mt-LigD, Mt-LigD and Mt-Ku, respectively. BW23474 (9,20) was obtained from Coli Genetics Stock Center (Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA) and used to propagate the derivatives of pAH143.

Plasmids

The pET16b vector containing the sequence for RV0938 (Mt-LigD) was used as the template for polymerase chain reaction (PCR). pAHMCS#6 (9) (a derivative of the CRIM vector pAH143 that integrates into the HK022 site in the E.coli genome) (20) and pAH-HisLigase (9) were used to prepare Mt-LigD expression constructs. These constructs and their derivatives were propagated in BW23474 at 15 μg/ml gentamicin. The two plasmids used in the end-joining assay were pBestluc (Promega Inc., Madison, WI, USA) that expresses firefly luciferase and confers carbenicillin resistance (100 μg/ml) and pACYC184 (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA, USA) that encodes chloramphenicol and tetracycline resistance genes. Bacteria containing pACYC184 were grown on Luria-Bertani medium (LB) containing 34 μg/ml chloramphenicol.

Oligodeoxyribonucleotides

The oligodeoxyribonucleotides (oligonucleotides) used were purchased from Operon Technologies Inc. (Alameda, CA, USA) or the DNA facility at Iowa State University. The oligonucleotides His3, His4, His5, His6, Kpn1 and Kpn2 contained 5′ phosphates. The sequences for the oligonucleotides were as follows: His3, d(TATGGGCCATCATCATCATCATCATCATCATCATCACAGCAGCGGCCATATCGAAGGTCGTCA); His4, d(TATGACGACCTTCGATATGGCCGCTGCTGTGATGATGATGATGATGATGATGATGATGGCCCA); His5, d(TATGGGCCATCATCATCATCATCATCATCATCATCACAGCAGCGGCCATATCGAAGGTCGTCAT); His6, d(CTAGATGACGACCTTCGATATGGCCGCTGCTGTGATGATGATGATGATGATGATGATGATGGCCCA); Kpn1, d(CCGCGGCACGGGTAGCACGGGTAGCACGGGTAGCACGGGTAGCATGGGTCTAGACTAGGGTAC) and Kpn2, d(CCTAGTCTAGACCCATGCTACCCGTGCTACCCGTGCTACCCGTGCTACCCGTGCCGCGGGTAC).

The primers used to PCR the PolDom were Poldom1 d(ATCGAAGGTCGTCATATGGGTTCGGCG) and Poldom2, d(TGCTACCCGTGCCGCGGTATCGGGTCAACCGG). The primers used to PCR the LigDom were Ligdom1 d(TAGCATGGGTCTAGACCAGAAGGTGTTCGAGTTC) and Ligdom2 d(TACCCTAGTCTAGACTCATTCGCGCACCACCTCAC). Primer1 d(ACGACCTUCGATATGGCCGCTGCT) and Primer2 d(AAGGTCGUCGCCGCATGCGCGAC) were used to amplify the construct expressing Mt-LigD and introduce a deletion of the PolDom to produce a construct to express the Δpol protein (Figure 1).

The following primers were used to sequence the Mt-LigD expression constructs: CRIM1, d(ATCCATAAGATTAGCGG); CRIM3, d(CGGATATTATCGTGAGG); Lig1, d(GTTAGCTAGGGTTTCGAGCAG); Lig2, d(TGGTGCTGGACGGCGAGG); Lig3, d(ACTGGAACACCCAGGAAG) and Lig4, d(TAAAGGCCAGCCAGTGGG).

The primers (20) used for PCR to check for integration of the pAH143 derivatives and to confirm the presence of the Mt-Ku expression construct were as follows: P1λ, d(GGCATCACGGCAATATAC); P4λ, d(TCTGGTCTGGTAGCAATG); P1HK, d(GGAATCAATGCCTGAGTG); P4HK, d(GGCATCAACAGCACATTC); P2, d(ACTTAACGGCTGACATGG) and P3, d(ACGAGTATCGAGATGGCA).

The following primers were used to sequence or PCR the repair products to determine the size of deletions: Luc 1, d(TGGATGGCTACATTCTG); Luc 5, d(GCCTGGTATCTTTATAG); Hind 3, d(GAACGTGACGGACGTAAC); Luc 3, d(ATGTGGATTTCGAGTCGTCT) and R, d(TCATCGTCTTTCCGTGCT).

Generating constructs to express Mt-LigD mutants

The amplification of the polymerase and ligase domains was performed using Hot Start Phusion High-Fidelity DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs) in accordance with the manufacturer's recommendations. To PCR each domain, reactions were initiated with 5 μM of the appropriate primers, buffer HF and pET16b RV0938 as the template. After 30 cycles, excess primers and dNTPs were removed using a Montage PCR clean-up column (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The product was digested to obtain the appropriate restriction termini and the fragments purified following electrophoresis through an agarose gel. At each step in the development of the expression vectors, successful ligation of the domains was determined by restriction enzyme digest. The accuracy of domain sequences and the orientation of the fragments within the parent vector were confirmed by sequencing by the DNA Facility at Iowa State University.

pAHMCS#6 (9) (a pAH143 derivative) (20) was used to generate the Mt-LigD expression constructs. This plasmid contains the araB promoter and so is only able to express downstream protein coding sequences in the presence of arabinose. Since this plasmid contains the γ replication origin of R6K, it was necessary to propagate the constructs in the bacterial strain BW23474. The Kpn1 and Kpn2 oligonucleotides were annealed as described previously (9) and inserted into the KpnI site of pAHMCS#6, which generated pAHMCS#7. The DNA fragment inserted using these oligonucleotides encodes the amino acid sequence (arg-gly [thr gly ser]4 met-gly-leu) and was used to link the polymerase and ligase domains to allow movement and flexibility of the individual domains. The core amino acid sequence ([thr gly ser]4 met-gly) was previously used to link the BRCA2 BRC type 4 sequence to the N-terminus of the RAD51 sequence (21).

The PolDom was amplified by PCR using Poldom1 and Poldom2 primers with an annealing temperature of 65°C. The product was digested with NdeI and SacII and inserted into NdeI–SacII-linearized pAHMCS#7. Oligonucleotides His3 and His4 were annealed and ligated into the NdeI site of this vector to generate pAHPolDom. This construct expresses an N-terminal histidine-tagged fusion of the PolDom and the linker (protein PolDom, Figure 1).

To generate a construct to express a His-tagged fusion protein of the PolDom and LigDom of Mt-LigD (pAHΔnuc), the LigDom of Mt-LigD was amplified using Ligdom1 and Ligdom2 with a 65°C annealing temperature. The DNA fragment was then digested with XbaI and inserted into the XbaI site of pAHPoldom, generating a construct to express the Δnuc fusion protein (Figure 1).

In order to develop a construct to express a His-tagged LigDom that contained the linker sequence (LigDom#1, Figure 1), the His-tag was ligated into the NdeI site in pAHMCS#7 prior to inserting the LigDom at the XbaI site resulting in pAHLigDom#1. To obtain a vector expressing Ligdom#2 (Figure 1), which is the LigDom without the linker sequence, His5 and His6 were annealed and inserted into NdeI–XbaI-linearized pAHMCS#7, creating pAHMCS#8. pAHLigDom#1 was digested with XbaI, and the fragment containing the LigDom was isolated and inserted into pAHMCS#8 at the XbaI restriction site.

To produce pAHΔpol, (construct to express the Δpol protein, Figure 1), pAHHisLigase (9) was used as a DNA template to amplify the whole vector using primers 1 and 2 (oligonucleotides section) using Pfu Turbo Cx Hotstart DNA polymerase from Stratagene (LaJolla, CA, USA). The annealing temperature was 72°C. Primers were designed to amplify a linear vector deleted in the PolDom. These primers produced a PCR product containing a uracil 8 bp from the end of each DNA terminus. The PCR product was isolated from an agarose gel and purified using Qiaquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA, USA) before treatment with USER enzyme (New England Biolabs) according to manufacturer’s recommendations. This removed the uracils and created a single-strand break at the resulting abasic site. Loss of the 8 bp single-strand DNA fragments resulted in a linear piece of DNA with compatible 8 bp overhangs. The vector was ligated using T4 ligase (Promega Inc.) and transformed into BW23474. Following selection on solid medium containing 15 μg/ml gentamicin, DNA was prepared from colonies and screened by restriction enzyme digest for the correct construct. The Mt-LigD coding region was then sequenced prior to integration of the construct.

Integration of the pAH-constructs into the E.coli chromosome

Integrating the constructs into the E.coli chromosome was performed as described by Haldimann and Wanner (20). Briefly, the bacteria (BWKu or BW35) were first transformed with pAH69 by electroporation. pAH69 expresses an integrase, which corresponds to the HK022 phage attachment site. This plasmid can only replicate at 30°C, and bacterial strains containing this plasmid were therefore grown at 30°C on solid medium or in liquid culture containing 100 μg/ml carbenicillin during all preparations of the bacteria for electroporation. For each strain created, the bacteria were transformed with 100 ng of the pAH vector and grown at 37°C for 1 h, followed by 42°C for 30 min. Growth at these temperatures prevents the replication of pAH69 and activates the integrase, which allows integration of the pAH vectors into the host chromosome. A portion of the culture was then plated on solid medium containing 5 μg/ml gentamicin and grown overnight at 37°C. To ensure the antibiotic resistance gene was integrated, the colonies were then grown on solid medium without antibiotic before re-plating again on the solid medium containing 5 μg/ml gentamicin. Each strain was tested for carbenicillin resistance to ensure that pAH69 had been ‘cured’ from the bacteria.

Primers P1, P2, P3 and P4 were used to PCR the new strains to determine successful single-copy pAH vector integration at the HK022 site. In BWKu strains, the presence of the Mt-Ku vector at the λ site in the genome was also confirmed by PCR. PCR was performed as previously described (9,20).

Western analysis

The bacteria were grown in a 5 ml LB culture without antibiotic overnight at 37°C at 250 r.p.m. This culture was diluted 100 times in LB and grown at 37°C and 300 r.p.m. for ∼1.5 h. The L-arabinose was added to a final concentration of 0.2% and the bacteria were allowed to grow for an additional hour during which time the absorbance of the culture at 600 nm wavelength (OD600) of ∼0.5. The bacteria were then harvested by centrifugation at 4°C and resuspended in 0.5 ml lysis buffer (0.1 mg/ml lysozyme, 45 mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid, pH 7.8, 80 mM KCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 2 μg/ml pepstatin A). The samples were sonicated and centrifuged at 4°C and 13 000 r.p.m. for 10 min to remove the cell debris. The protein concentration of the cell-free extract was then determined according to the Bradford method using the Bio-Rad Protein Assay reagent (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Protein (50 μg) was electrophoresed through a Tris-glycine 4–20% gradient sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel and transferred by electroblotting to 0.2 μm nitrocellulose membrane. An anti-His-tag monoclonal antibody (final concentration 0.2 μg/ml; Novagen, Madison, WI, USA) was used to probe the membrane according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. A secondary horseradish peroxidase antibody (diluted 1:3000; Amersham, Piscataway, NJ, USA) and chemiluminescent substrate (ECL-plus substrate; Amersham) was subsequently used to visualize the His-tagged protein using autoradiography.

End-joining assay

The end-joining assay was performed using PacI- or ClaI-linearized pBestluc. The digested DNA was purified twice through a 0.8% agarose gel using the Qiaquick Gel Extraction kit (Qiagen Inc.). To prepare electrocompetent bacteria, the strains were grown as described above for western analysis. Following growth of the cultures with and without the addition of L-arabinose to a final OD600 of ∼0.5, the bacteria were harvested and prepared for electroporation as described previously (22). Linearized pBestluc (50 ng) and 0.1 ng pACYC184 were co-transformed into the bacteria using the Bio-Rad Gene Pulser Xcell Electroporation System (Hercules, CA, USA) at 2.5 kV, 200 Ω and 25 μF, transferred to 1.5 ml LB and grown for 1.5 h at 37°C and 250 r.p.m. A portion of the cultures was plated in triplicate on solid medium containing either 100 μg/ml carbenicillin or 34 μg/ml chloramphenicol and grown overnight at 37°C. The colonies were counted and a ratio of the carbenicillin-resistant (CarbR) colonies/chloramphenicol-resistant (CmR) colonies was calculated for each transformation. Since pACYC184 encodes chloramphenicol resistance, calculating this ratio enables each sample to be normalized for transformation efficiency. This ratio corresponds to the total repair. The CarbR colonies were then transferred to nylon membranes and sprayed with firefly luciferase substrate to determine the number of colonies that either expressed active (Luc+) or inactive (Luc−) firefly luciferase. A ratio of CarbR:CmR was determined for each transformation for the Luc+ and Luc− colonies.

To examine the inaccurate repair products, Luc− CarbR colonies were analysed by PCR using primers to determine the presence of deletions or insertions: Hind 3 and Luc 5 with an annealing temperature of 50°C; Luc 3 and Luc 5 with an annealing temperature of 47°C and Luc 1 and R with an annealing temperature of 55°C. Each sample analysed was compared to the predicted full-length product for pBestluc: 2.6 kb for Hind 3-Luc 5, 1.6 kb for Luc 3 and 5 and 236 bp for Luc1 and R. The sequence across the junction was determined by isolating plasmid from the bacteria using the Wizard Plus Miniprep DNA purification system (Promega Inc.) and sequencing was performed by the DNA Facility at Iowa State University (Ames, IA, USA).

Statistical analysis

The CarbR:CmR ratios from the end-joining assay were compared to the corresponding BWKuLig#2 data using the Instat3 program and the Mann–Whitney test.

To determine whether there was an equal distribution of deletion sizes for the size categories (<50 bp, 51–500 bp, 501–1000 bp and >1001 bp), samples were tested to determine whether each size category contained 25% of the total population by using a Chi-Square test. Tests were conducted separately for the repair of either 3′ or 5′ overhangs for each group (BWKuLig#2, BWKuΔnuc and BWKuLigDom#1). The distribution of deletion sizes was compared between the termini types (3′ and 5′ overhangs) for each strain analysed (BWKuLig#2, BWKuΔnuc and BWKuLigDom#1) separately by using Chi-Square test. All analyses were performed by using the SAS 9.13 program (SAS Inc, Gary, NC, USA). All P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results and discussion

Generation of bacteria expressing mutants of Mt-LigD

The CRIM vector system (20) is designed to express proteins from vectors integrated into phage attachments sites in the E.coli genome. Vectors are available that integrate into different phage attachments sites and so more than one ‘foreign’ protein can be expressed from the genome in the same bacterial strain. The integration of the vectors also allows assays to be performed using plasmids, as the expression vectors do not interfere with plasmid replication. This was therefore a good system to examine the interaction of Mt-Ku and Mt-LigD during plasmid re-circularization. Expression of the proteins is also under the control of an arabinose-inducible promoter, allowing the Mt-NHEJ to be switched on and off in the same bacterial strain. We previously (9) generated bacterial strains expressing His-tagged Mt-Ku from the lambda phage attachment site (BWKu) or His-tagged Mt-LigD from the HK022 site (BWLig). A strain (BWKuLig#2) was also created using pAHHisLigase to express Mt-LigD (Figure 1) in combination with Mt-Ku (9). For this present study, BWKuLig#2 was the wild-type Mt-LigD, and strains carrying mutants of Mt-LigD were compared to this wild-type strain.

To generate constructs expressing proteins B–F (Figure 1), we used derivatives of the pAH143 vector (20) or pAHHisLigase (9). Each construct was designed with a sequence that encoded an N-terminus His-tag to allow visualization of the proteins by western analysis. These vectors were integrated into the HK022 phage attachment site of the BWKu bacterial strain or BW35 (parental strain). Following the integration procedure, colonies were checked by PCR to select only those containing a single copy of the expression vector integrated at the correct site (data not shown).

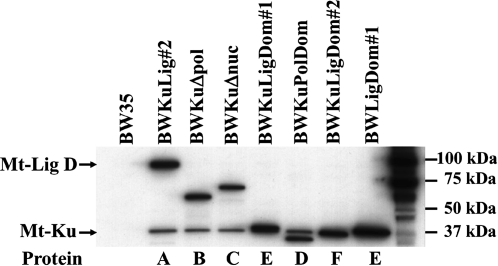

Expression of the mutant Mt-LigD proteins and Mt-Ku was checked by growing the strains in 0.2% L-arabinose for 1 h prior to preparing cell-free extracts from the exponential phase cultures. The His-tagged proteins are not expressed in cultures that are not treated with arabinose (9 and data not shown). The 1-h induction time was previously found to be optimal for expressing the proteins and also mimics the growth conditions for preparation of electrocompetent cells for the end-joining assay. Western analysis using an anti-His-tag antibody detected the Mt-Ku protein and the wild-type and mutant forms of Mt-LigD (Figure 2). As previously found, Mt-LigD was expressed at a higher level than the Mt-Ku in BWKuLig#2. This was also seen for the strains expressing the mutant LigD proteins B–F. There were small variations in expression levels of the mutant LigD proteins compared to the wild-type Mt-LigD. Mutants Δnuc and PolDom were expressed at ∼60% of the wild-type, Δpol was ∼80% of the wild-type, while LigDom#1 was expressed at equivalent levels to the wild-type Mt-LigD. The LigDom#1 and LigDom#2 proteins electrophoresis at a similar size to Mt-Ku. To examine the expression level of LigDom#1, it was necessary to use the strain that did not express Mt-Ku (BWLigDom#1). A comparison of the LigDom#2 and the wild-type Mt-LigD could not be performed as it was not possible to distinguish this mutant from Mt-Ku.

Fig. 2.

Western blot analysis. Bacterial strains were generated by integrating constructs encoding B–F into the genome of the previously generated BwKu strain (9). LigDom#1 was also integrated into BW35 to generate a strain BWLigdom#1 that did not express Mt-Ku. BWKuLig#2 expresses the wild-type Mt-Ku and Mt-LigD. Western analyses were performed on cell-free extracts prepared from exponential phase cultures grown in 0.2% L-arabinose for 1 h. Membranes were probed using an anti-His-tag monoclonal antibody that recognizes proteins containing five consecutive histidines. The Ligdom#1 and #2 proteins are approximately the same size as Mt-Ku.

Deletion of the central domain of Mt-LigD results in greater repair capacity

Previous studies (15) identified histidine 373 in the central domain of Mt-LigD as the amino acid essential for the 3′–5′ single-stranded DNA exonuclease. However, when this central domain (amino acids 271–459) was expressed in vitro as a separate protein, no activity was detected (15). It was speculated that this may have been due to the lack of ability of the central domain to bind the DNA termini or due to mis-folded protein in the absence of the rest of the Mt-LigD protein. Repaired DNA break junctions of Mt-Ku and Mt-LigD from E.coli also previously showed large deletions (9). We therefore hypothesized that the nuclease activity of the central domain was contributing to the deletions during plasmid re-circularization in E.coli. To clarify whether the central domain had nuclease activity that functioned in bacteria during repair, we developed a construct to express the Δnuc protein (Figure 1). Published studies have shown that the PolDom and LigDom can be individually expressed and still maintain functional activity in vitro (15). We therefore added a 17 amino acid linker [arg-gly [thr gly ser]4 met-gly-leu] between the two domains, deleting amino acids 301–447 of Mt-LigD, to produce Δnuc. This linker region was added to allow flexibility and movement of the domains. A similar linker was previously used to join the BRCA2 BRC type 4 sequence to the N-terminus of the RAD51 sequence (21).

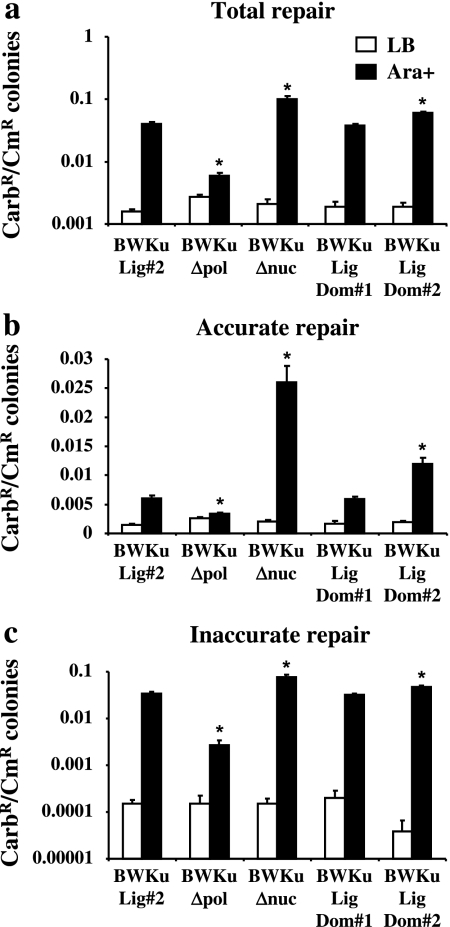

To test activity, an end-joining assay was used where the plasmid (pBestluc) was linearized with either PacI or ClaI. The plasmid is carbenicillin resistant (CarbR) and expresses firefly luciferase from the tac promoter. PacI and ClaI are unique sites located in the 3′ end of the luciferase coding region. Accurate repair is therefore required for active luciferase to be synthesized from the plasmid sequence. A second chloramphenicol resistant (CmR) vector (pACYC184) was co-transformed with the linear pBestluc into the bacteria that were grown in the presence (Ara+) or absence (LB) of L-arabinose. pACYC184 was used to normalize for transformation efficiency and an increase in the ratio of CarbR colonies to the CmR colonies for the Ara+ samples versus the LB samples is an indication of repair. Bacteria expressing Δnuc and Mt-Ku (BWKuΔnuc) were able to rejoin the Pacl (2 bp 3′ AT overhang, Figure 3a) as well as ClaI (2 bp 5′ GC overhang, Figure 4a) linearized pBestluc. A significant increase in the total repair for both types of DNA termini was found for the strain expressing Δnuc (BWKuΔnuc) compared to wild-type Mt-LigD (BWKuLig#2). For DNA termini containing PacI 3′ overhangs, the CarbR:CmR ratio for the Ara+ samples was 0.071 ± 0.006 for BWKuΔnuc and 0.047 ± 0.006 for BWLuLig#2 (Figure 3a), which is a 1.5 times increase. This increase was also seen in the Ara+:LB ratio, which was 309 for BWKuΔnuc and 241 for BWKuLig#2. For DNA termini with ClaI 5′ overhangs, there was an ∼2-fold increase in total repair for BWKuΔnuc compared to BWKuLig#2; the CarbR:CmR ratio for the Ara+ samples was 0.10 ± 0.01 for BWKuΔnuc and 0.04 ± 0.0003 for BWLuLig#2 (Figure 4a), while the Ara+:LB ratio was 48 for BWKuΔnuc compared to 24 for BWKuLig#2. This increase in repair was detected even though Δnuc is expressed at a slightly lower level in BWKuΔnuc than Mt-LigD in BWKuLig#2 (Figure 2).

Fig. 3.

DNA repair of termini with 3′ overhangs by the PolDom and NucDom mutants of Mt-LigD. Bacteria were grown in LB or LB supplemented with 0.2% L-arabinose (Ara+) prior to the preparation of electrocompetent bacteria. Bacteria were then electroporated with PacI-linearized pBestluc (50 ng) and 0.1 ng pACYC184. The ratio of CarbR:CmR colonies was calculated for the total number of CarbR colonies (a), the CarbR Luc+ colonies (b) and the CarbR Luc− colonies (c). The average and standard error are shown graphically from at least six transformations. Asterisks represent a statistical difference of P < 0.05 for the arabinose-induced experiments of the individual bacterial strains compared to BWKuLig#2.

Fig. 4.

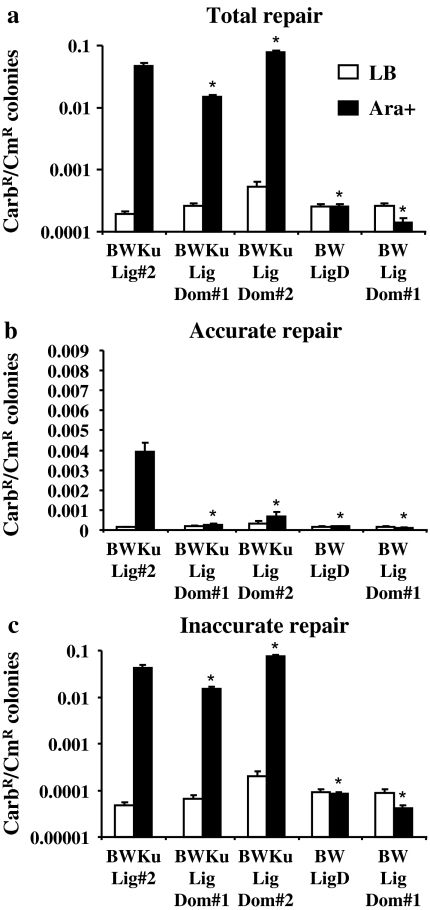

DNA repair of termini with 5′ overhangs by mutants of Mt-LigD. Bacteria were grown in LB or LB supplemented with 0.2% L-arabinose (Ara+) prior to the preparation of electrocompetent bacteria. Bacteria were then electroporated with ClaI-linearized pBestluc (50 ng) and 0.1 ng pACYC184. The ratio of CarbR:CmR colonies was calculated for the total number of CarbR colonies (a), the CarbR Luc+ colonies (b) and the CarbR Luc− colonies (c). The average and standard error are shown graphically from at least six transformations. Asterisks represent a statistical difference of P < 0.05 for the arabinose-induced experiments of the individual bacterial strains compared to BWKuLig#2.

To examine the accuracy of repair, the colonies were sprayed with luciferase substrate. The increase in the CarbR:CmR for the colonies expressing active luciferase (Luc+) is a measure of the accurate repair, while the CarbR:CmR for the colonies inactive for luciferase (Luc−) is a measure of inaccurate repair. As can be seen in Figures 3 and 4, the deletion of the central domain (Δnuc in BWKuΔnuc) significantly increased the accurate and inaccurate repair. For DNA termini containing PacI 3′ overhangs, the Luc+CarbR:CmR ratio for the Ara+ samples was 0.0075 ± 0.0008 for BWKuΔnuc and 0.0039 ± 0.0005 for BWKuLig#2 (Figure 3b) and the Luc− CarbR:CmR ratio for the Ara+ samples was 0.064 ± 0.005 for BWKuΔnuc and 0.043 ± 0.006 for BWKuLig#2 (Figure 3c). For ClaI-DNA termini, inaccurate repair increased by 2-fold (Luc− CarbR:CmR was 0.076 ± 0.009 for BWKuΔnuc and 0.034 ± 0.003 for BWKuLig#2, Figure 4c) and compared to the wild-type Mt-LigD, Δnuc repair was three to four times more accurate (Figure 4b): the Luc+CarbR:CmR ratio for the Ara+ samples was 0.026 ± 0.003 for BWKuΔnuc and 0.006 ± 0.0005 for BWKuLig#2 and the Ara+:LB ratio was 13 (BWKuΔnuc) compared to 4 (BWLuLig#2). By calculating how much of the total repair for a particular strain was accurate, it was also evident that Δnuc demonstrated an increased amount of accurate repair: 25% of the total repair for ClaI-linearized DNA was accurate for Δnuc as compared to 15% for the wild-type Mt-LigD.

These results indicate that the central domain does influence the products of repair and loss of this domain increased the total repair, as well as the accuracy of repair. This therefore supports the idea that this domain has nuclease activity and that it is involved in deletion formation. Since total as well as accurate and inaccurate repair increased, it is possible that the lack of the central domain and nuclease activity resulted in a greater stability of the linear plasmid DNA allowing more time for repair. Deletion of recB and hence loss of the RecBCD nuclease was also found to increase the level of total, accurate and inaccurate repair in this model (9). Previous studies in M.smegmatis did not see a change in deletions when the catalytic histidine 336 was mutated to an alanine (19). It is therefore possible that in our system, the remainder of the central domain may also be involved in deletion formation.

The PolDom of Mt-LigD is required for efficient and accurate repair

The PolDom containing the 17 amino acid linker (PolDom) was expressed with Mt-Ku in strain BWKuPolDom. This domain was unable to re-circularize plasmid DNA (Figure 3). This therefore agrees with the in vitro studies (15), which indicate that this domain does not have DNA ligase activity.

Previously, in vitro studies demonstrated that the Mt-Ku binds to Mt-LigD through the N-terminal PolDom. We therefore generated a construct that produces a mutated Mt-LigD deleted in the first 300 amino acids of the protein (Δpol, Figure 1). Total repair activity was dramatically decreased in BWKuΔpol compared to BWKuLig#2 (Figures 3a and 4a, CarbR:CmR was 0.006 ± 0.002 for Δpol and 0.047 ± 0.006 for wild-type with PacI-linearized DNA and 0.006 ± 0.0007 for Δpol and 0.04 ± 0.003 for wild-type with ClaI-linearized DNA). Repair was not, however, completely eliminated as seen by the Ara+:LB ratio: the ratio decreased from 25 for wild-type to 2 for BWKuΔpol for total repair of ClaI-linearized DNA, and from 241 to 24 for PacI-linearized DNA. The slight decrease in expression of Δpol compared to wild-type Mt-LigD (Figure 2) cannot account for this dramatic loss in repair activity. It is likely that this loss of repair was due to deletion of the major Ku-binding site and the inability of the Mt-Ku to ‘load’ the mutated Mt-LigD onto the DNA termini. Inaccurate repair also decreased by ∼10–30 times (Figures 3c and 4c): the CarbR:CmR was 0.005 ± 0.002 for Δpol and 0.043 ± 0.006 for wild-type with PacI-linearized DNA and 0.003 ± 0.0007 for Δpol and 0.034 ± 0.003 for wild-type with ClaI-linearized DNA, while the Ara+:LB ratios were 33 for Δpol and 894 for wild-type with PacI-linearized DNA and 18 compared to 244 with ClaI-linearized DNA. A similar dramatic decrease in repair efficiency was seen by deletion of the PolDom of the M.smegmatis LigD (19). Interestingly, in our work, loss of the PolDom completely eliminated accurate repair (Figures 3b and 4b). It is possible that in this E.coli model, the PolDom works to insert nucleotides that have been removed by nucleases and hence improve accuracy. Deletion of the PolDom in the LigD in M.smegmatis actually altered the fidelity of repair depending on the types of DNA termini: a 10-fold decrease was found for blunt termini and an increase in fidelity was found for termini with 5′ overhangs (19). Loss of the PolDom in this M.smegmatis study did not result in the elimination of the addition of templated nucleotides, and the authors suggest that there is another template-dependent polymerase that is able to function in a Ku-dependent manner on termini with 5′ overhangs in M.smegmatis. Since our E.coli system does not have interference from other Ku-dependent NHEJ proteins, it is possible to conclude from this study that the PolDom of Mt-LigD is involved in the accuracy of repair in this system, as well as play an important structural role in binding to Mt-Ku.

The LigDom of Mt-LigD can function in Ku-dependent repair

Previous studies (15) demonstrated that the LigDom was able to function as a DNA ligase in vitro, and in this work, loss of the PolDom (Δpol) substantially reduced but did not eliminate inaccurate repair (Figures 3 and 4). We therefore produced two constructs to determine whether the LigDom could function independently of the PolDom and NucDom in bacteria to re-circularize plasmid DNA. The LigDom#2 protein contains only the LigDom (amino acids 448–759), while LigDom#1 consists of the LigDom with the 17 amino acid linker attached (Figure 1). Both proteins were able to perform inaccurate repair with only about a 2-fold variation in levels compared to the wild-type Mt-LigD with ClaI (Figure 4c, CarbR:CmR ratio was 0.034 ± 0.003, 0.032 ± 0.002 and 0.048 ± 0.003 for BWKuLig#2, BWKuLigDom#1 and BWKuLigDom#2, respectively) and PacI-linearized DNA (Figure 5c, CarbR:CmR ratio was 0.043 ± 0.006, 0.015 ± 0.002 and 0.076 ± 0.005 for BWKuLig#2, BWKuLigDom#1 and BWKuLigDom#2, respectively) when Mt-Ku was also expressed in the bacteria. Wild-type Mt-LigD cannot function in bacteria independent of Mt-Ku (9 and Figure 5) and similarly, expression of LigDom#1 in BW35 without Mt-Ku resulted in no re-circularization of plasmid DNA (Figure 5). There are two possible explanations for why the LigDom could ligate DNA in a Ku-dependent manner: firstly, the Mt-Ku could bind to the termini of the linear DNA and prevent degradation by nucleases, so increasing the half-life of the DNA, allowing the LigDom time to interact and ligate the termini, and secondly, there is an interaction of Mt-Ku with the LigDom. If the Mt-Ku was merely enhancing the chance of a ligase interacting with the linear DNA, it would be expected that when Mt-Ku was expressed in the absence of Mt-LigD that an increase in repair would be seen due to E.coli ligase A ligating the now stabilized linear DNA. This was not seen in our previous study (9). Our results are therefore consistent with a physical interaction between Mt-Ku and the LigDom that aids in LigDom re-circularizing the plasmid DNA in E.coli. Interestingly, the addition of the linker reduced the repair activity of the LigDom (Figure 4a, CarbR:CmR ratio with ClaI-linearized DNA was 0.038 ± 0.003 and 0.06 ± 0.003 for BWKuLigDom#1 and BWKuLigDom#2, respectively, and was 0.016 ± 0.002 and 0.078 ± 0.005 for BWKuLigDom#1 and BWKuLigDom#2, respectively, for PacI-linearized DNA Figure 5a). When LigDom#2 was compared to Δpol (Figures 3–5), it was clear that the addition of the NucDom to the LigDom also decreased repair activity. It is possible that this potential Mt-Ku-binding site on the LigDom plays a minor role, if any, in recruitment of the wild-type Mt-LigD to the DSB. The decreased repair capability of the LigDom as protein is added to the N-terminus suggests that this potential Mt-Ku site is hidden or weakened by the wild-type structure of Mt-LigD. The mycobacterium ligase C only consists of a LigDom and this too is believed to act with Ku in a ‘back-up’ NHEJ pathway (13,19). It would be interesting for future studies to compare the structures of Mt-LigC and the Mt-LigD LigDom to try to reveal similarities that could identify potential Mt-Ku interaction sites.

Fig. 5.

DNA repair of termini with 3′ overhangs by the LigDom of Mt-LigD. Bacteria expressing Lig D proteins Mt-LigD, LigDom#1 or LigDom#2 with or without Mt-Ku were grown in LB or LB supplemented with 0.2% L-arabinose (Ara+). Following electroporation with PacI-linearized pBestluc (50 ng) and 0.1 ng pACYC184, the ratio of CarbR:CmR colonies was calculated for the total number of CarbR colonies (a), the CarbR Luc+ colonies (b) and the CarbR Luc− colonies (c). The average and standard error are shown graphically from at least six transformations. The data for BWKuLig#2 is the same data shown in Figure 3 and is included here for comparison. Asterisks represent a statistical difference of P < 0.0001 for the arabinose-induced experiments of the individual bacterial strains compared to BWKuLig#2.

Accurate repair was also examined for LigDom#1 and LigDom#2. When Mt-Ku was expressed in the bacteria, accurate repair of ClaI DNA termini was detected (Figure 4b), but negligible accurate repair was found for these LigDoms when PacI-linearized DNA was examined (Figure 5b). This difference may be related to the hydrogen bonding capacity of the different termini: ClaI forms a GC overhang, while PacI generates an AT overhang.

Analysis of the junctions of NHEJ repaired DSBs

Inaccurate repair results in Luc− CarbR colonies. PCR analysis was performed to determine the size of deletions or insertions. As previously found, no insertions were detected and the deletions ranged in size from <50 bp to >1000 bp for both the PacI and ClaI-linearized plasmid (Table I). Analysis of the distribution of the number of colonies within each deletion size group showed that generally each size group did not contain 25% of the colonies, which would have been expected if deletions were introduced in a random way. When the distribution was compared for the PacI and ClaI-linearized DNA for the BWKuLig#2 strain, there was a significant change in the pattern with the re-circularization of the ClaI-digested plasmid resulting in a greater number of smaller deletions. This indicates that Mt-LigD tended to introduce larger deletions when re-circularizing PacI-linearized DNA. This may be related to the preference of the Mt-NHEJ proteins for a particular type of DNA substrate. Previous studies (19) have shown that the more ‘natural’ substrates for the M.smegmatis NHEJ proteins are DNA termini that are blunt or that contain 5′ overhangs. Interestingly, the distribution of deletions for the BWKuLigDom#1 was not different for the PacI and ClaI-linearized DNA: repair products for the ClaI-digested DNA still tended to have a higher percentage of larger deletions as found for the PacI-linearized DNA. It is possible that loss of the PolDom in LigDom#1 resulted in larger deletions, which otherwise would have been partially corrected by the insertion of nucleotides by the polymerase activity.

Table I.

PCR analysis of repair products

| DNA termini | Strain | Number of colonies analysed | Approximate deletion sizes |

|||

| <50 | 51–500 | 501–1000 | >1000 | |||

| PacI | BWKuLig#2 | 114 | 10 (9%) | 27 (24%) | 24 (21%) | 53 (46%) |

| BWKuΔnuc | 115 | 24 (21%) | 33 (29%) | 12 (10%) | 46 (40%) | |

| BWKuLigDom#1 | 122 | 16 (13%) | 37 (30%) | 20 (17%) | 49 (40%) | |

| ClaI | BWKuLig#2 | 110 | 25 (23%) | 33 (30%) | 23 (21%) | 29 (26%) |

| BWKuΔnuc | 101 | 35 (35%) | 33 (33%) | 10 (10%) | 23 (22%) | |

| BWKuLigDom#1 | 99 | 17 (17%) | 28 (28%) | 11 (11%) | 43 (44%) | |

Following transformation of linearized DNA, the CarbR colonies were tested for firefly luciferase activity. PCR was used to test for plasmid containing deletions in Luc- colonies. The PCR product was subjected to electrophoresis and the deletion size determined.

Deletion of the NucDom resulted in a significant shift (P = 0.0125) from deletions in the range of 501–1000 bp to <50 bp compared to BWKuLig#2 for repair of the PacI-linearized DNA. A similar trend was also seen for the ClaI-digested DNA. This again suggests that the central NucDom of Mt-LigD does play a role in the generation of deletions during repair. Since deletions of all sizes were still detected even when the NucDom was absent from the Mt-LigD (Table 1) and no other domains of the Mt-proteins have been found to have nuclease activity, it is likely the remaining deletions were introduced prior to binding of Mt-Ku by the many exonucleases in E.coli. In our previous study (9), a dramatic increase in repair was seen in the absence of RecB, so demonstrating that the nucleases in E.coli can influence the repair of the linear DNA by the Mt-NHEJ proteins. It was concluded that this increase in repair was due to an increase in half-life of the linear DNA due to a lack of degradation by the RecBCD nuclease.

We previously demonstrated that end joining with this model generated products where joining occurred at regions of microhomology (9). Plasmid DNA was isolated from the colonies and sequenced (Table II). The repair junctions for LigDom#1 and Δnuc still occurred at regions of microhomology (1–4 bp). There was also no bias for the generation of the deletions in a particular direction with the bacterial strains examined.

Table II.

Sequence of repair products

| Strain | DNA termini | Deletion size | Sequence before repair | Sequence after repair | Microhomology region |

| BWKu Lig#2 | PacI | 48 | GAAGTC—TCGATAT | GAAGTCGATAT | TC |

| 600 | TCGAAG—AAGTACC | TCGAAGTACC | AAG | ||

| ClaI | 14 | CCCCCG—CGATATTG | CCCCCGATATTG | CG | |

| 281 | TTGACAA—ACAACC | TTGACAACC | ACAA | ||

| BWKu Δnuc | PacI | 4 | GTCTTT—TTAAATA | GTCTTTAAATAC | TT |

| 768 | TGACCG—CCGGCAG | TGACCGGCAG | CCG | ||

| ClaI | 54 | CCCCGC—GCAGGTC | CCCCGCAGGTC | GC | |

| 247 | TACACCC—CCCCAA | TACACCCCAA | CCC | ||

| BWKu LigDom#1 | PacI | 102 | AGGATG—GCCCCCG | AGGATGCCCCG | G |

| 522 | GATCCC—CCCCCGC | GATCCCCCGC | CCC | ||

| ClaI | 29 | CCCCGC—CCCAACA | CCCCGCCCAACA | C | |

| 200 | AGGACC—ACCCCAA | AGGACCCCAA | ACC |

After transformation of linearized DNA, the CarbR colonies were tested for firefly luciferase activity. PCR was used to test for plasmid containing deletions in Luc− colonies. Plasmid was then isolated and sequenced to identify the repair junction. Representative examples are shown. Microhomology sequences are in bold.

Summary

In summary, we provide evidence to indicate that the central NucDom does play a role in wild-type Mt-LigD reducing total and accurate repair and increasing deletions in re-circularized plasmid DNA when expressed with Mt-Ku in E.coli. The PolDom of Mt-LigD is unable to ligate DNA but is very important for initiating repair. We also provide evidence that is consistent with the existence of a potential Mt-Ku interaction/binding site on the LigDom of Mt-LigD, as the LigDom could perform plasmid re-circularization but only in a Ku-dependent manner. Our studies with the different deletion mutants of Mt-LigD indicate that this Ku-binding site appears to be minor or very weak in the wild-type Mt-LigD.

This work has therefore extended the previous studies of Mt-NHEJ and has demonstrated that this E.coli model is useful for examining the interaction of Mt-Ku and Mt-LigD. Since there is no interference from host Ku-dependent NHEJ proteins, this model could be used in the future to examine more detailed mutations of the PolDom for interaction with Mt-Ku. Future studies are also planned to try to identify other proteins that modify the M.tuberculosis NHEJ repair pathway and result in more accurate repair.

Funding

National Cancer Institute, the National Institutes of Health (CA 85693).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Reneau Castore for technical assistance and Dr Tak Yee Aw for help with manuscript preparation.

Conflict of interest statement: None declared.

References

- 1.Weterings E, van Gent DC. The mechanism of non-homologous end-joining: a synopsis of synapsis. DNA Repair (Amst.) 2004;3:1425–1435. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doherty AJ, Jackson SP, Weller GR. Identification of bacterial homologues of the Ku DNA repair proteins. FEBS Lett. 2001;500:186–188. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02589-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aravind L, Koonin EV. Prokaryotic homologs of the eukaryotic DNA-end-binding protein Ku, novel domains in the Ku protein and prediction of a prokaryotic double-strand break repair system. Genome Res. 2001;11:1365–1374. doi: 10.1101/gr.181001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weller GR, Doherty AJ. A family of DNA repair ligases in bacteria? FEBS Lett. 2001;505:340–342. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02831-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moeller R, Stackebrandt E, Reitz G, Berger T, Rettberg P, Doherty AJ, Horneck G, Nicholson WL. Role of DNA repair by nonhomologous-end joining in Bacillus subtilis spore resistance to extreme dryness, mono- and polychromatic UV, and ionizing radiation. J. Bacteriol. 2007;189:3306–3311. doi: 10.1128/JB.00018-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pitcher RS, Green AJ, Brzostek A, Korycka-Machala M, Dziadek J, Doherty AJ. NHEJ protects mycobacteria in stationary phase against the harmful effects of desiccation. DNA Repair (Amst.) 2007;6:1271–1276. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chayot R, Montagne B, Mazel D, Ricchetti M. An end-joining repair mechanism in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:2141–2146. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906355107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Della M, Palmbos PL, Tseng HM, et al. Mycobacterial Ku and ligase proteins constitute a two-component NHEJ repair machine. Science. 2004;306:683–685. doi: 10.1126/science.1099824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malyarchuk S, Wright D, Castore R, Klepper E, Weiss B, Doherty AJ, Harrison L. Expression of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Ku and Ligase D in Escherichia coli results in RecA and RecB-independent DNA end-joining at regions of microhomology. DNA Repair (Amst.) 2007;6:1413–1424. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dynan WS, Yoo S. Interaction of Ku protein and DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit with nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:1551–1559. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.7.1551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gong C, Martins A, Bongiorno P, Glickman M, Shuman S. Biochemical and genetic analysis of the four DNA ligases of mycobacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:20594–20606. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401841200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilkinson A, Day J, Bowater R. Bacterial DNA ligases. Mol. Microbiol. 2001;40:1241–1248. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gong C, Bongiorno P, Martins A, Stephanou NC, Zhu H, Shuman S, Glickman MS. Mechanism of nonhomologous end-joining in mycobacteria: a low-fidelity repair system driven by Ku, ligase D and ligase C. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005;12:304–312. doi: 10.1038/nsmb915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu H, Shuman S. Characterization of Agrobacterium tumefaciens DNA ligases C and D. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:3631–3645. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pitcher RS, Tonkin LM, Green AJ, Doherty AJ. Domain structure of a NHEJ DNA repair ligase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;351:531–544. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pitcher RS, Brissett NC, Picher AJ, Andrade P, Juarez R, Thompson D, Fox GC, Blanco L, Doherty AJ. Structure and function of a mycobacterial NHEJ DNA repair polymerase. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;366:391–405. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weller GR, Kysela B, Roy R, et al. Identification of a DNA nonhomologous end-joining complex in bacteria. Science. 2002;297:1686–1689. doi: 10.1126/science.1074584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu H, Shuman S. Novel 3′-ribonuclease and 3′-phosphatase activities of the bacterial non-homologous end-joining protein, DNA ligase D. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:25973–25981. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504002200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aniukwu J, Glickman MS, Shuman S. The pathways and outcomes of mycobacterial NHEJ depend on the structure of the broken DNA ends. Genes Dev. 2008;22:512–527. doi: 10.1101/gad.1631908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haldimann A, Wanner BL. Conditional-replication, integration, excision, and retrieval plasmid-host systems for gene structure-function studies of bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 2001;183:6384–6393. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.21.6384-6393.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pellegrini L, Yu DS, Lo T, Anand S, Lee M, Blundell TL, Venkitaraman AR. Insights into DNA recombination from the structure of a RAD51-BRCA2 complex. Nature. 2002;420:287–293. doi: 10.1038/nature01230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seidman CE, Struhl K, Sheen J, Jessen T. Introduction of plasmid DNA into cells. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. 1997;32:1.8.4–1.8.5. doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb0108s37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]