Abstract

Classical conditioning of eyeblink responses has been one of the most important models for studying the neurobiology of learning, with many comparative, ontogenetic, and clinical applications. The current study reports the development of procedures to conduct eyeblink conditioning in preweanling lambs and demonstrates successful conditioning using these procedures. These methods will permit application of eyeblink conditioning procedures in the analysis of functional correlates of cerebellar damage in a sheep model of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, which has significant advantages over more common laboratory rodent models. Because sheep have been widely used for studies of pathogenesis and mechanisms of injury with many different prenatal or perinatal physiological insults, eyeblink conditioning can provide a well-studied method to assess postnatal behavioral outcomes, which heretofore have not typically been pursued with ovine models of developmental insults.

Keywords: delay conditioning, associative learning in lamb, ovine model, cerebellum

Eyeblink classical conditioning involves exposing subjects to series of discrete trials in which a neutral (e.g., auditory) condi tioned stimulus (CS) is consistently presented prior to the onset of an unconditioned stimulus (US), such as an airpuff directed at the cornea. Initially, the CS does not evoke a behavioral response whereas the US reliably elicits a reflexive eyeblink, the “uncon ditioned” response (UR). With sufficient CS–US pairings, the CS comes to elicit a learned or “conditioned” response (CR), similar to the UR but timed to occur prior to the onset of the US. The classically conditioned eyeblink response has been extensively studied and validated in humans (normal and clinical populations), rabbits, rats, and normal and genetically modified mice (Woodruff-Pak & Steinmetz, 2000a, 2000b), but, to our knowl edge, there are no published reports of eyeblink conditioning in sheep.

Eyeblink conditioning is ideally suited for comparative behav ioral studies in animal models of developmental disorders. A key advantage is that the neural circuitry involved in learning and performance has been identified in multiple species. Cerebellar and brainstem circuitry is necessary and sufficient for learning the CS–US association with delay conditioning, and sites of learning-related functional and structural neuroplasticity mediating the conditioned eyeblink response have been identified (Christian & Thompson, 2003; Kleim et al., 2002; Lavond, Kim, & Thompson, 1993; Medina, Nores, Ohyama, & Mauk, 2000; Steinmetz, 1996; Thompson, 1986; Thompson & Kim, 1996). For acquisition of trace conditioning and other higher-order procedural variants, the hippocampus and related forebrain structures are additionally required (Ivkovich & Stanton, 2001; McGlinchey-Berroth, Carrillo, Gabrieli, Brawn, & Disterhoft, 1997; Solomon, Vander Schaaf, Thompson, & Weisz, 1986; Weiss, Bouwmeester, Power, & Disterhoft, 1999). The developmental emergence of eyeblink conditioning has been characterized in rodents and humans (Claflin, Stanton, Herbert, Greer, & Eckerman, 2002; Freeman, Carter, & Stanton, 1995; Freeman, Barone, & Stanton, 1995; Ivkovich, Paczkowski, & Stanton, 2000, Freeman, Spencer, Skelton, & Stanton, 1993; Stanton, Freeman, & Skelton, 1992), including characterization of correlated developmental changes in structure and function of identified eyeblink conditioning neural circuits (Freeman & Muckler, 2003; Freeman & Nicholson, 2000a, 2000b), suggesting that eyeblink conditioning may be a useful tool as an early indicator of prenatal brain damage in translational research.

Developmental alcohol-induced structural damage to the cerebellum and correlated deficits in acquisition of eyeblink conditioning were first demonstrated in rats following binge-like exposure to alcohol during the “brain growth spurt” of the early postnatal period (Green, 2004; Green, Johnson, Goodlett, & Steinmetz, 2002; Green, Rogers, Goodlett, & Steinmetz, 2000; Green, Tran, Steinmetz, & Goodlett, 2002; Stanton & Goodlett, 1998; Tran, Stanton, & Goodlett, 2007). Recent studies of eyeblink conditioning in humans with fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) or alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorders (ARND) have confirmed significant deficits in acquisition of eyeblink classical conditioning (Coffin, Baroody, Schneider, & O’Neill, 2005; Jacobson et al., submitted), consistent with the significant and disproportionately severe loss of volume in the anterior cerebellum demonstrated in structural imaging studies (Autti-Ramo et al., 2002; Johnson, Swayze, Sato, & Andreasen, 1996; Riley & McGee, 2005; Sowell et al., 1996; Swayze et al., 1997). Taken together, these findings suggest that cerebellar damage and deficits in cerebellar-dependent learning may be a common phenotype of the fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) that results from heavy prenatal alcohol exposure (Riley & McGee, 2005).

Human studies (Coles, 1994; May et al., 2005; Rosett & Weiner, 1984; Rosett et al., 1983; Smith, Coles, Lancaster, Fernhoff, & Falek, 1986) and experimental animal studies (Maier, Chen, & West, 1996; Tran & Kelly, 2003) indicate that the severity of brain damage and neurobehavioral dysfunction increases if episodic (binge) drinking continues into the third trimester. The rat studies that first identified alcohol-induced eyeblink conditioning deficits involved heavy, binge-like exposure during the early postnatal period of rapid brain development, a stage of brain development in rats roughly comparable to that of the human third trimester (Bayer, Altman, Russo, & Zhang, 1993; Dobbing & Sands, 1979). Rodent models of binge alcohol exposure during this “third-trimester equivalent” must administer alcohol to pups after birth, and are thereby limited because they cannot include potentially important maternal/placental/fetal interactions that may influence the type and extent of damage to the developing brain (see Cudd, 2005). Thus, an important consideration for translational research on FASD is the development of animal models in which alcohol exposure can extend into the third-trimester equivalent of brain development while the fetus is still in utero. In this regard, a crucial feature of the ovine model is that stages of brain development that occur over the three trimesters of human pregnancy also occur entirely prenatally in fetal sheep (Cudd, 2005; West, 1987). Manipulations of dose, timing, duration, and daily patterns of alcohol exposure in fetal sheep can be accomplished with greater temporal precision across different stages of brain development entirely in utero, while the maternal-fetal unit remains intact. Timed-mated ewes can be instrumented with catheters that can be maintained throughout pregnancy with relatively limited stress to the ewe (Cudd, Chen, & West, 2002; Ramadoss, Hogan, Given, West, & Cudd, 2006), permitting controlled alcohol dosing via infusions and sampling of arterial blood for monitoring blood alcohol levels. Sheep also share many features in common with humans with respect to maternal–fetal physiology, for which there is a large scientific literature (Back, Riddle, & Hohimer, 2006; Harding & Bloomfield, 2004; McClaine et al., 2007; Reynolds et al., 1996; Wood & Chen, 1989). Consequently, to study the relative risk for prenatal alcohol-induced brain damage related to differences in the dose and timing of exposure throughout pregnancy, the sheep model provides many compelling advantages over rodents.

The impetus to establish eyeblink conditioning in the sheep was stimulated both by the evidence that cerebellar damage appears to be an important component of the FASD phenotype, and by our recent findings that binge-like maternal exposure in sheep, either during the third-trimester equivalent or during the first-trimester equivalent of fetal sheep brain development, induces significant loss of Purkinje cells (Ramadoss, Lunde, Pina, Chen, & Cudd, 2007; West, Parnell, Chen, & Cudd, 2001). As part of our ongoing effort to assess the functional consequences of prenatal exposure to alcohol in a sheep model of FASD, we sought to establish procedures for evaluating acquisition of eyeblink conditioning in preweanling lambs. If eyeblink classical conditioning is feasible in sheep, it can likely provide an important behavioral tool to evaluate the functional status and development of the neural systems mediating learning—one that should be useful in assessing factors affecting risk for prenatal alcohol-induced brain damage, and that would translate relatively directly to the human condition. Given its relevance to FASD phenotypes, and likely to other neurodevelopmental disorders, we report here the initial efforts assessing acquisition of eyeblink conditioning in sheep.

Method

Subjects

All procedures were done with approval of the Texas A&M University Laboratory Animal Care Committee. Suffolk lambs from timed pregnancies were weighed, ear-tagged, and given a subcutaneous 5-ml B-vitamin injection within a day of birth. Body weights were obtained weekly, and coccidia vaccinations were given at 4 and 8 weeks of age. Lambs remained with lactating maternal ewes at all times except during 1-hr daily eyeblink training sessions, which began at 6 weeks of age.

Modification of Eyeblink Conditioning System for Use With Lambs

An eyeblink conditioning system (Model 6200–0001-F, San Diego Instruments, San Diego, CA) designed for use with human subjects was modified for use with lambs. Pneumatic tubing for delivery of the corneal airpuff US (10-foot length [3-meter], 1/16-in [1.6-mm] inner diameter) and a cable with an attached infrared light-sensitive diode for detecting changes in corneal reflectance indicative of eyelid movement were positioned in close proximity to one another inside a 4.5-cm length of vinyl tubing (3/4-in inner diameter, 1-in outer diameter, product No. 60985–572, VWR, West Chester, PA) such that the diode and nozzle at the end of the pneumatic tubing were flush with the end of the vinyl tube. The vinyl tubing was filled with two-part quick-setting epoxy, with care taken to maintain the position of the nozzle and diode relative to one another and to avoid occluding the end of either with epoxy. After the epoxy hardened, the vinyl tubing was cut away, leaving a 4.5-cm epoxy plug with the nozzle and diode protruding from one end and the pneumatic tubing and diode cable extending from the other.

Goggle Construction

The left eyepiece was detached from a pair of welding/chipping goggles (model VGC, Fiber-Metal, Concordville, PA). The glass lens was replaced with copolyester sheeting (5-cm diameter, Pet-G Vivak thermoplastic, US Plastic Corp., Lima, OH) with a hole (2.3-cm diameter) cut in the center. A 2.5-cm length of vinyl tubing (3/4-in inner diameter, 1-in outer diameter) was inserted into the hole in the copolyester replacement lens and held in place by a groove cut around the outer circumference, 0.5-cm from the inserted end. The 4.5-cm epoxy plug containing the airpuff nozzle and diode was then inserted into the 2.5-cm vinyl tubing mounted in the lens.

Two slots (2-mm long) were cut in the outer (temporal) edge of the left eyepiece, 0.5 cm from the edge, 1 cm on either side of a preexisting center slot containing an elastic band. Velcro (Velcro USA, Inc., Manchester, NH) strips were passed through these slots, and 5-cm lengths were doubled over and secured with staples and/or glue. Both ends of an 8-cm length of ball-chain were secured in a preexisting slot on the inner (nasal) side of the eyepiece. Two more Velcro straps and the other end of the elastic band were secured to the loop of ball-chain (Figure 1A).

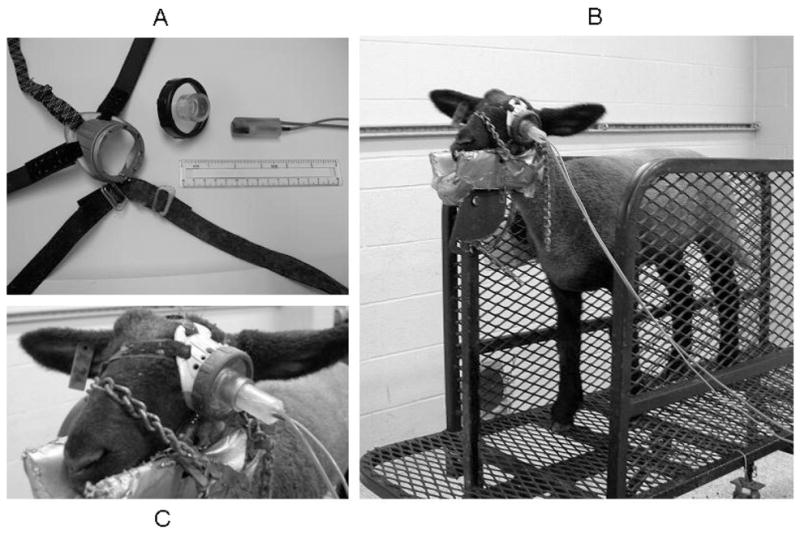

Figure 1.

(A) Components of goggle used for eyeblink conditioning in lambs: goggle body with Velcro straps and elastic band, removable copolyester lens with vinyl tubing mounted in center, and epoxy plug containing pneumatic tubing and infrared light-sensitive diode. Six-in ruler included for scale. (B) Lamb secured in trim stand with goggle in place. Speakers normally mounted on lamb’s left side removed for visual clarity, right-side speakers still in place. (C) Close-up of assembled goggle, in place over left eye.

Eyeblink Conditioning Training Procedures

Lambs were gradually habituated to separation from the maternal ewe and to restraint in the experimental apparatus during the week prior to the first session of eyeblink training. Lambs were placed on a trim stand (model VSEBSC, Show Stopper Equipment, Vittetoe Inc., Keota, IA) and short lengths of chain over the nose and behind the head were used to secure the head and nose in a padded cradle to minimize movement during training (Figure 1B).

The goggle was placed directly over the left eye and secured in place with an elastic band (caudal to orbit of right eye) and two pairs of Velcro straps, one around the nose, the other behind the right ear and under the neck, with the hole in the center of the lens centered over the eye. The epoxy plug was inserted into the vinyl tubing in the center of the lens and adjusted so that the airpuff nozzle and diode were directed at the cornea from a distance of approximately 2 cm (Figure 1C).

CS and US Conditioning Parameters

We were unable to find any prior references to eyeblink classical conditioning in sheep in the experimental literature. Data are presented for normal male and female lambs trained on a delay conditioning procedure similar to one used in human infants (Claflin et al., 2002; Ivkovich, Eckman, Krasnegor, & Stanton, 2000). Lambs received 150 trials/session, using a 650-ms auditory CS, with a 600-ms interstimulus interval (ISI) before onset of the US, a 50-ms airpuff (source pressure 15 psi [1.055 kgf/cm2]) that coterminated with the CS. The white noise CS (~74 dB) was projected bilaterally via pairs of PC speakers mounted on the sides of the trim stand (1–2 ft from lamb’s head); ambient noise levels ranged from approximately 55 to 60 dB. The tactile US was controlled by a solenoid and air pressure regulator interfaced with the computer running the eyeblink training software and connected to a pressurized tank of nitrogen. (Compressed air would work just as well, but would additionally require an air compressor; small tanks of compressed nitrogen are readily available commercially and provide a long-lasting, inexpensive source of clean, inert, compressed gas.) Every tenth trial was a CS-alone probe trial, permitting periodic recordings of eyeblink responses throughout the trial period in the absence of a US or UR. Trials were separated by intertrial intervals of random duration with a mean of 20 s and a range of 10 to 30 s. Individual daily training sessions lasted less than one hour (~50–60 min/session). Daily training sessions continued for six consecutive days beginning when lambs were six weeks of age.

Data Analysis

San Diego Instruments eyeblink software reports moment-to-moment infrared-reflectance data (1-kHz sampling rate) in arbitrary units of reflectance; data are stored for later offline analysis. For each session, all trials were scanned prior to scoring to identify the peak amplitude for the whole session (i.e., single highest peak on any trial, 100%). For each trial, changes in infrared reflectance indicative of eyelid movement were scored as a behavioral response if the amplitude exceeded 10% of the amplitude of the predetermined maximal response, and trials were discarded from behavioral analyses if eyelid activity during the 350-ms pre-CS baseline period exceeded this threshold. Behavioral responses initiated during the first 100 ms of the ISI were scored as alpha (nonassociative startle) responses. On probe trials, all responses initiated after the alpha response period until the end of the 1200-ms trial epoch were scored as CRs. On paired trials, responses initiated after the alpha response period but before US onset were scored as CRs, and responses initiated during the 350-ms period after US onset were scored as URs. CR frequencies (percentage of trials with a CR) from Sessions 1 to 6 from four male and four female lambs were analyzed with a 2 × 2 × 6 repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), treating session (repeated measure) and trial type (paired or probe) as within-subject factors and sex as a between subjects factor.

Results

The percentage of trials with CRs increased significantly across training sessions, as confirmed by a main effect of session (F[5,30] = 25.330, p < .001). There were no main or interactive effects of sex (Figure 2A) or trial type (Figure 2B) on CR frequencies, nor were significant changes across sessions apparent for CR amplitudes (on paired or probe trials), or for probe trial measures of latency to CR onset or peak amplitude (see Table 1).

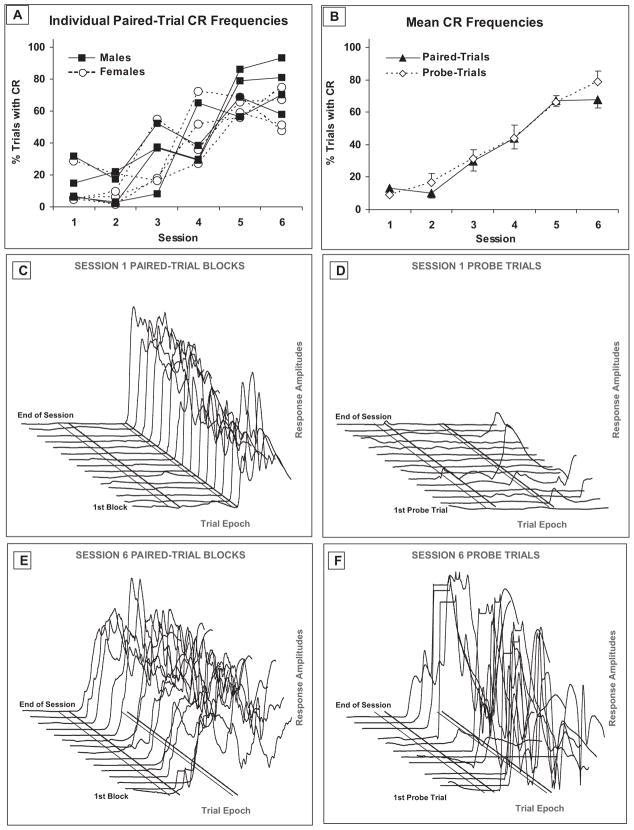

Figure 2.

(A) Individual paired-trial conditioned response (CR) frequencies from eight lambs (four males and four females), Sessions 1–6. (B) Combined mean (± SEM) CR frequencies for paired-trial and probe-trials, Sessions 1–6. Corneal reflectance data from one lamb during the first (C, D) and the sixth (E, F) daily eyeblink training sessions. Graphs show eyeblink activity for each of the fifteen 10-trial blocks per session. On each trial, corneal reflectance data were recorded for 1.5 s (1-kHz sampling rate) and presented here as 5-ms bins of mean activity. Diagonal lines in each graph indicate (from left to right): end of baseline period/onset of audible CS (first solid line), end of alpha (startle) response period/beginning of CR period (first dotted line), onset of airpuff US/beginning UR period (second solid line), and CS/US termination (second dotted line). Each of the tracings in Figures 2C and 2E is a composite, an average of all the CS–US paired trials within that block that were not discarded because of excessive pre-CS baseline activity (≤ 9 trials/block), whereas the tracings in Figure 2D and 2F show responses on individual probe trials. (Averaging the activity of multiple trials has the effect of “smoothing” the block tracings relative to the individual probe trials.) For this lamb, the fifth and eleventh probe trials were excluded from analysis on Session 6 because of excessive activity during baseline period.

Table 1.

Means (± SEM) for Eyeblink Conditioned Response (CR), Unconditioned Response (UR), and Alpha Response (AR) Performance Measures Across Training Sessions

| Session |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| CR | ||||||

| Onset latenciesa | 729 ( ± 67) | 744 ( ± 43) | 820 (± 38) | 746 ( ± 31) | 672 (± 9) | 715 ( ± 25) |

| Latencies to peak amplitudea | 840 ( ± 65) | 846 ( ± 50) | 901 (± 43) | 829 ( ± 33) | 767 (± 11) | 807 ( ± 25) |

| Peak amplitudesa | 32.6 (±4.2) | 30.7 (±5.6) | 25.8 (± 2.6) | 34.5 (±4.4) | 36.5 (± 4.1) | 42.5 (±6.9) |

| Peak amplitudes | 36.8 (±4.9) | 40.1 (±4.1) | 38.1 (± 4.5) | 39.1 (±3.8) | 39.3 (± 3.3) | 46.6 (±6.8) |

| UR | ||||||

| Peak amplitudes | 52.9 (±6.6) | 55.0 (±7.9) | 48.0 (± 5.7) | 48.2 (±7.2) | 42.4 (± 4.9) | 44.1 (±5.9) |

| Frequencies | 86.4 (±5.7) | 85.8 (±4.9) | 77.4 (± 5.4) | 74.7 (±2.1) | 62.2 (± 5.1) | 58.8 (±5.6) |

| AR | ||||||

| Peak amplitudes | 17.1 (±2.5) | 20.0 (±3.0) | 32.4 (± 6.0) | 29.7 (±6.1) | 28.7 (± 5.9) | 41.9 (±7.0) |

| Frequencies | 1.6 (±0.6) | 1.5 (±1.1) | 1.9 (± 0.7) | 1.8 (±0.6) | 2.1 (± 0.6) | 3.3 (±0.9) |

Note. Separate analyses of individual daily means for each of these measures (one-way analysis of variance with session as a repeated measure, p < .05) revealed no significant change in performance across sessions for any measure.

CR values obtained from probe trials, insuring measurements free of potential US influence and UR artifact.

Behavioral data from the first and sixth sessions are shown for one lamb in Figure 2, C–F, displayed separately for paired-trial blocks (Figures 2C, 2E) and CS-alone probe trials (Figures 2D, 2F). During the first session, there was very little eyeblink activity on paired trials prior to the onset of the US (Figure 2C) and very little activity at all on probe trials (Figure 2D). On the majority of paired trials, robust URs were seen in response to the US. This was important for several reasons. The pattern and frequency of responses during early sessions (primarily URs) showed that our goggle attachment provided reliable delivery of the airpuff, that lambs responded to the US with the expected reflexive UR, and that the diode was sensitive to changes in corneal reflectance indicative of eyelid movement. The significant increase in CR frequencies across sessions confirmed acquisition of the learned eyeblink response; corresponding changes in AR and UR frequencies (see Table 1) across sessions were not observed. AR and UR peak amplitudes did not differ significantly across sessions. CRs were clearly evident by Session 6, as eyelid movement was frequently initiated prior to the US in response to the CS on paired trials (Figure 2E), and probe trials showed the emergence of frequent, well-timed CRs that reached peak amplitude around the time when the US was presented on paired trials (Figure 2F).

Discussion

These results demonstrate an effective eyeblink conditioning preparation that reliably evokes URs and detects eyelid movement in preweanling lambs. We confirmed that lambs can show signif icant increases in CR frequencies across daily training sessions, indicative of a learned association between the CS and US, ulti mately producing CRs on 75% to 80% of all trials after six sessions. To our knowledge, this is the first report of eyeblink conditioning in sheep. Lambs can be tested at least as young as six weeks of age and at any age thereafter, potentially permitting early detection of associative learning deficits and/or longitudinal eval uation of treatment regimens designed to improve neurological functioning. By six weeks age, the extensive myelination and expansion of the neuropil associated with brain development dur ing human infancy has already occurred in the lamb, but in terms of sexual maturity, lambs at this age are still several months away from reproductive competency (>6 months age). Albeit lacking the specificity of a direct age-equivalence, for purposes of equating sheep and human development, the 6-week-old lamb is perhaps best characterized as being at a postinfancy, prepubescent, “child hood” stage of development. In terms of rodent development, 6-week-old lambs are most comparable to periweanling rats, be tween postnatal days 20 to 30.

The immediate objective in using eyeblink conditioning is to assess the effects of prenatal alcohol exposure in the sheep model of FASD, in which binge-like alcohol exposure can be given during gestation during defined periods of fetal brain development (first trimester equivalent; third trimester equivalent; all three trimesters equivalent). This effort will help provide data from in utero ovine models that can provide conclusive evidence concern ing whether there are critical periods of vulnerability to prenatal alcohol-induced damage to cerebellar functional development, and whether cessation of binge exposure after the first trimester equiv alent significantly improves outcomes (Goodlett, Horn, & Zhou, 2005).

The scientific study of sheep behavior is relatively undeveloped (Johnston, Ferriero, Vannucci, & Hagberg, 2005), especially com pared with laboratory rodents. There are some notable exceptions, however, such as the analyses of neural systems underlying facial recognition memory (Kendrick, da Costa, Leigh, Hinton, & Peirce, 2001; Tate, Fischer, Leigh, & Kendrick, 2006) and filial recogni tion and bonding by maternal ewes (Ferreira et al., 2000; Keller, Meurisse, & Levy, 2005; Keller et al., 2003). Development of eyeblink conditioning in the sheep can help advance the under standing of sheep behavior in general, by providing a well established, well-characterized behavioral preparation that can be integrated into a very large scientific literature drawn from decades of behavioral neuroscience research. Developing this methodology can help provide a means to incorporate functional behavioral analyses, linked to specific neural systems, to study the neurobi ology of learning and memory in sheep.

Studies of eyeblink conditioning in sheep may be particularly relevant for ovine models of perinatal insults, which have been ex tensively used to characterize prenatal and perinatal physiological insults but for which analysis of behavioral or functional outcomes have been notably lacking (Bennet, Dean, Wassink, & Gunn, 2007; Hutton et al., 2007; Milley, 1997; Rees, Stringer, Just, Hooper, & Harding, 1997). Thus, eyeblink conditioning in sheep could have many important applications in research beyond our intended use in the sheep model of FASD. For example, there is a large literature on use of sheep to study perinatal hypoxia-ischemia that documents cerebellar injury and mechanisms of brain pathology (Dorrepaal et al., 1997; Hope et al., 1987; Hutton et al., 2007; Roohey, Raju, & Moustogiannis, 1997; Shadid, Hiltermann, Monteiro, Fontijn, & Van Bel, 1999). Further development of eyeblink conditioning methodology can provide important opportunities to assess postnatal functional and behavioral consequences in these and other sheep models of prenatal insults and developmental pathologies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIAAA Grant R21 AA015339 to Timothy A. Cudd. The authors thank Kristin Haase, Alison Gonsalves, John Paul Regan, Justin Box, Ashli Burns, and Michelle Miller for assisting with data collection, and Rachel Zanek, Jessica Williams, and Emilie Lunde for providing technical assistance.

Contributor Information

Timothy B. Johnson, Department of Veterinary Physiology and Pharmacology and Michael E. DeBakey Institute, College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, Texas A&M University

Mark E. Stanton, Department of Psychology, University of Delaware

Charles R. Goodlett, Department of Psychology, Indiana University Purdue University Indianapolis

Timothy A. Cudd, Department of Veterinary Physiology and Pharmacology and Michael E. DeBakey Institute, College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, Texas A&M University

References

- Autti-Ramo I, Autti T, Korkman M, Kettunen S, Salonen O, Valanne L. MRI findings in children with school problems who had been exposed prenatally to alcohol. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 2002;44:98–106. doi: 10.1017/s0012162201001748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Back SA, Riddle A, Hohimer AR. Role of instrumented fetal sheep preparations in defining the pathogenesis of human periventricular white-matter injury. Journal of Child Neurology. 2006;21:582–589. doi: 10.1177/08830738060210070101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer SA, Altman J, Russo RJ, Zhang X. Timetables of neurogenesis in the human brain based on experimentally determined patterns in the rat. Neurotoxicology. 1993;14:83–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennet L, Dean JM, Wassink G, Gunn AJ. Differential effects of hypothermia on early and late epileptiform events after severe hypoxia in preterm fetal sheep. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2007;97:572–578. doi: 10.1152/jn.00957.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian KM, Thompson RF. Neural substrates of eyeblink conditioning: Acquisition and retention. Learning and Memory. 2003;10:427–455. doi: 10.1101/lm.59603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claflin DI, Stanton ME, Herbert J, Greer J, Eckerman CO. Effect of delay interval on classical eyeblink conditioning in 5-month-old human infants. Developmental Psychobiology. 2002;41:329–340. doi: 10.1002/dev.10050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffin JM, Baroody S, Schneider K, O’Neill J. Impaired cerebellar learning in children with prenatal alcohol exposure: A comparative study of eyeblink conditioning in children with ADHD and dyslexia. Cortex. 2005;41:389–398. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(08)70275-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles C. Critical periods for prenatal alcohol exposure: Evidence from animal and human studies. Alcohol Health and Research World. 1994;18:22–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cudd TA. Animal model systems for the study of alcohol teratology. Experimental Biology and Medicine. 2005;230:389–393. doi: 10.1177/15353702-0323006-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cudd TA, Chen WJ, West JR. Fetal and maternal thyroid hormone responses to ethanol exposure during the third trimester equivalent of gestation in sheep. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research. 2002;26:53–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbing J, Sands J. Comparative aspects of the brain growth spurt. Early Human Development. 1979;3:79–83. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(79)90022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorrepaal CA, van Bel F, Moison RM, Shadid M, van de Bor M, Steendijk P, et al. Oxidative stress during post-hypoxic-ischemic reperfusion in the newborn lamb: The effect of nitric oxide synthesis inhibition. Pediatric Research. 1997;41:321–326. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199703000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira G, Terrazas A, Poindron P, Nowak R, Orgeur P, Levy F. Learning of olfactory cues is not necessary for early lamb recognition by the mother. Physiology and Behavior. 2000;69:405–412. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(00)00211-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman JH, Carter CS, Stanton ME. Early cerebellar lesions impair eyeblink conditioning in developing rats: Differential effect of unilateral lesions on postnatal day 10 or 20. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1995;109:893–902. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.109.5.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman JH, Jr, Barone S, Jr, Stanton ME. Disruption of cerebellar maturation by an antimitotic agent impairs the ontogeny of eyeblink conditioning in rats. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15:7301–7314. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-11-07301.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman JH, Jr, Muckler AS. Developmental changes in eyeblink conditioning and neuronal activity in the pontine nuclei. Learning and Memory. 2003;10:337–345. doi: 10.1101/lm.63703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman JH, Jr, Nicholson DA. Developmental changes in eye-blink conditioning and neuronal activity in the cerebellar interpositus nucleus. Journal of Neuroscience. 2000a;20:813–819. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-02-00813.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman JH, Jr, Nicholson DA. Developmental changes in the neural mechanisms of eyeblink conditioning. Behavioral and Cognitive Neuroscience Reviews. 2000b;3:3–14. doi: 10.1177/1534582304265865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman JH, Spencer CO, Skelton RW, Stanton ME. Ontogeny of eyeblink conditioning in the rat: Effect of US intensity and interstimulus interval on delay conditioning. Psychobiology. 1993;21:233–242. [Google Scholar]

- Goodlett CR, Horn KH, Zhou FC. Alcohol teratogenesis: Mechanisms of damage and strategies for intervention. Experimental Biology and Medicine. 2005;230:394–406. doi: 10.1177/15353702-0323006-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green JT. The effects of ethanol on the developing cerebellum and eyeblink classical conditioning. Cerebellum. 2004;3:178–187. doi: 10.1080/14734220410017338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green JT, Johnson TB, Goodlett CR, Steinmetz JE. Eyeblink classical conditioning and interpositus nucleus activity are disrupted in adult rats exposed to ethanol as neonates. Learning and Memory. 2002;9:304–320. doi: 10.1101/lm.47602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green JT, Rogers RF, Goodlett CR, Steinmetz JE. Impairment in eyeblink classical conditioning in adult rats exposed to ethanol as neonates. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research. 2000;24:438–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green JT, Tran TD, Steinmetz JE, Goodlett CR. Neonatal ethanol produces cerebellar deep nuclear cell loss and correlated disruption of eyeblink conditioning in adult rats. Brain Research. 2002;956:302–311. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03561-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding JE, Bloomfield FH. Prenatal treatment of intra-uterine growth restriction: Lessons from the sheep model. Pediatric Endocrinology Reviews. 2004;2:182–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hope PL, Cady EB, Chu A, Delpy DT, Gardiner RM, Reynolds EO. Brain metabolism and intracellular pH during ischaemia and hypoxia: An in vivo 31P and 1H nuclear magnetic resonance study in the lamb. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1987;49:75–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1987.tb03396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutton LC, Yan E, Yawno T, Castillo-Melendez M, Hirst JJ, Walker DW. Injury of the developing cerebellum: A brief review of the effects of endotoxin and asphyxial challenges in the late gestation sheep fetus. The Cerebellum, E-pub ahead of print. 2007 doi: 10.1007/s12311-014-0602-3. Retrieved August 01, 2007, from http://www.informaworld.com/2010.1080/14734220701358556. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ivkovich D, Paczkowski CM, Stanton ME. Ontogeny of delay versus trace eyeblink conditioning in the rat. Developmental Psychobiology. 2000;36:148–160. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2302(200003)36:2<148::aid-dev6>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivkovich D, Stanton ME. Effects of early hippocampal lesions on trace, delay, and long-delay eyeblink conditioning in developing rats. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2001;76:426–446. doi: 10.1006/nlme.2001.4027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivkovich, Eckman, Kresnegor, Stanton . Using eyeblink conditioning to assess neurocognitive development in human infants. In: Woodruff-Pak DS, Steinmetz JE, editors. Eyeblink classical conditioning: Volume I–Applications in humans. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson SW, Stanton ME, Molteno CD, Burden MJ, Fuller DS, Hoyme HE, et al. Impaired eyeblink conditioning in children with fetal alcohol syndrome. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00585.x. (submitted) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson VP, Swayze VW, II, Sato Y, Andreasen NC. Fetal alcohol syndrome: Craniofacial and central nervous system manifestations. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 1996;61:329–339. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960202)61:4<329::AID-AJMG6>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston MV, Ferriero DM, Vannucci SJ, Hagberg H. Models of cerebral palsy: Which ones are best? Journal of Child Neurology. 2005;20:984–987. doi: 10.1177/08830738050200121001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller M, Meurisse M, Levy F. Mapping of brain networks involved in consolidation of lamb recognition memory. Neuroscience. 2005;133:359–369. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller M, Meurisse M, Poindron P, Nowak R, Ferreira G, Shayit M, et al. Maternal experience influences the establishment of visual/auditory, but not olfactory recognition of the newborn lamb by ewes at parturition. Developmental Psychobiology. 2003;43:167–176. doi: 10.1002/dev.10130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendrick KM, da Costa AP, Leigh AE, Hinton MR, Peirce JW. Sheep don’t forget a face. Nature. 2001;414:165–166. doi: 10.1038/35102669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleim JA, Freeman JH, Jr, Bruneau R, Nolan BC, Cooper NR, Zook A, et al. Synapse formation is associated with memory storage in the cerebellum. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2002;99:13228–13231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202483399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavond DG, Kim JJ, Thompson RF. Mammalian brain substrates of aversive classical conditioning. Annual Review of Psychology. 1993;44:317–342. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.44.020193.001533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier SE, Chen W-J, West JR. The effects of timing and duration of alcohol exposure on development of the fetal brain. In: Abel EL, editor. Fetal alcohol syndrome: From mechanism to prevention. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1996. pp. 27–50. [Google Scholar]

- May PA, Gossage JP, Brooke LE, Marais AS, Hendricks LS, Snell CL, et al. Maternal risk factors for fetal alcohol syndrome in the Western Cape Province of South Africa: A population-based study. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:1190–1199. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.037093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClaine RJ, Uemura K, McClaine DJ, Shimatzu K, de la Fuente SG, Manson RJ, et al. A description of the preterm fetal sheep systemic and central responses to maternal general anesthesia. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2007;104:397–406. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000252459.43933.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlinchey-Berroth R, Carrillo MC, Gabrieli JD, Brawn CM, Disterhoft JF. Impaired trace eyeblink conditioning in bilateral, medial-temporal lobe amnesia. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1997;111:873–882. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.111.5.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina JF, Nores WL, Ohyama T, Mauk MD. Mechanisms of cerebellar learning suggested by eyelid conditioning. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2000;10:717–724. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00154-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milley JR. Ovine fetal leucine kinetics and protein metabolism during acute metabolic acidosis. American Journal of Physiology Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1997;272:E275–E281. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1997.272.2.E275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramadoss J, Hogan HA, Given JC, West JR, Cudd TA. Binge alcohol exposure during all three trimesters alters bone strength and growth in fetal sheep. Alcohol. 2006;38:185–192. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramadoss J, Lunde ER, Pina KB, Chen WJA, Cudd TA. All three trimester binge alcohol exposure causes fetal cerebellar Purkinje cell loss in the presence of maternal hypercapnea, acidemia, and normoxemia: Ovine model. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31:1252–1258. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees S, Stringer M, Just Y, Hooper SB, Harding R. The vulnerability of the fetal sheep brain to hypoxemia at mid-gestation. Brain Research Developmental Brain Research. 1997;103:103–118. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(97)81787-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds JD, Penning DH, Dexter F, Atkins B, Hardy J, Poduska D, et al. Ethanol increases uterine blood flow and fetal arterial blood oxygen tension in the near-term pregnant ewe. Alcohol. 1996;13:251–256. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(95)02051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley EP, McGee CL. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: An overview with emphasis on changes in brain And Behavior. Experimental Biology and Medicine. 2005;230:357–365. doi: 10.1177/15353702-0323006-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roohey T, Raju TN, Moustogiannis AN. Animal models for the study of perinatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: A critical analysis. Early Human Development. 1997;47:115–146. doi: 10.1016/s0378-3782(96)01773-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosett HL, Weiner L. Alcohol and the fetus. New York: Oxford University Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Rosett HL, Weiner L, Lee A, Zuckerman B, Dooling E, Oppenheimer E. Patterns of alcohol consumption and fetal development. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1983;61:539–546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadid M, Hiltermann L, Monteiro L, Fontijn J, Van Bel F. Near infrared spectroscopy-measured changes in cerebral blood volume and cytochrome aa3 in newborn lambs exposed to hypoxia and hypercapnia, and ischemia: A comparison with changes in brain perfusion and O2 metabolism. Early Human Development. 1999;55:169–182. doi: 10.1016/s0378-3782(99)00024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith IE, Coles CD, Lancaster J, Fernhoff PM, Falek A. The effect of volume and duration of prenatal ethanol exposure on neonatal physical and behavioral development. Neurobehavioral Toxicology and Teratology. 1986;8:375–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon PR, Vander Schaaf ER, Thompson RF, Weisz DJ. Hippocampus and trace conditioning of the rabbit’s classically conditioned nictitating membrane response. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1986;100:729–744. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.100.5.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowell ER, Jernigan TL, Mattson SN, Riley EP, Sobel DF, Jones KL. Abnormal development of the cerebellar vermis in children prenatally exposed to alcohol: Size reduction in Lobules I.–V. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1996;20:31–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton ME, Freeman JH, Skelton RW. Eyeblink conditioning in the developing rat. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1992;106:657–665. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.106.4.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton ME, Goodlett CR. Neonatal ethanol exposure impairs eyeblink conditioning in weanling rats. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1998;22:270–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmetz JE. The brain substrates of classical eyeblink conditioning in rabbits. In: Bloedel J, Ebner T, Wise S, editors. Acquisition of motor behavior in vertebrates. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1996. pp. 89–114. [Google Scholar]

- Swayze VW, 2nd, Johnson VP, Hanson JW, Piven J, Sato Y, Giedd JN, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of brain anomalies in fetal alcohol syndrome. Pediatrics. 1997;99:232–240. doi: 10.1542/peds.99.2.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tate AJ, Fischer H, Leigh AE, Kendrick KM. Behavioural and neurophysiological evidence for face identity and face emotion processing in animals. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B: Biological Sciences. 2006;361:2155–2172. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RF. The neurobiology of learning and memory. Science. 1986;233:941–947. doi: 10.1126/science.3738519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RF, Kim JJ. Memory systems in the brain and localization of a memory. Proceedings of the national Academy of Science. 1996;93:13438–13444. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran TD, Kelly SJ. Critical periods for ethanol-induced cell loss in the hippocampal formation. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 2003;25:519–528. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(03)00074-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran TD, Stanton ME, Goodlett CR. Binge-like ethanol exposure during the early postnatal period impairs eyeblink conditioning at short and long CS–US intervals in rats. Developmental Psychobiology. 2007;49:589–605. doi: 10.1002/dev.20226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss C, Bouwmeester H, Power JM, Disterhoft JF. Hippocampal lesions prevent trace eyeblink conditioning in the freely moving rat. Behavioural Brain Research. 1999;99:123–132. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(98)00096-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West JR. Fetal alcohol-induced brain damage and the problem of determining temporal vulnerability: A review. Alcohol and Drug Research. 1987;7:423–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West JR, Parnell SE, Chen W-J, Cudd TA. Alcohol-mediated Purkinje cell loss in the absence of hypoxemia during the third trimester in an ovine model system. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2001;25:1051–1057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood CE, Chen HG. Acidemia stimulates ACTH, vasopressin, and heart rate responses in fetal sheep. American Journal of Physiology. 1989;257:R344–R349. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1989.257.2.R344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff-Pak DS, Steinmetz JE, editors. Applications in humans. I. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2000a. Eyeblink classical conditioning. [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff-Pak DS, Steinmetz JE, editors. Animal models. II. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2000b. Eyeblink classical conditioning. [Google Scholar]