Abstract

This experiment examined the effects of women's relationship motivation, partner familiarity, and alcohol consumption on sexual decision making. Women completed an individual difference measure of relationship motivation, then were randomly assigned to partner familiarity condition (low, high), and to alcohol consumption condition (high dose, low dose, no alcohol, placebo). Then women read and projected themselves into a scenario of a sexual encounter. Relationship motivation and partner familiarity interacted with intoxication to influence primary appraisals of relationship potential. Participants’ primary and secondary relationship appraisals mediated the effects of women's relationship motivation, partner familiarity, and intoxication on condom negotiation, sexual decision abdication, and unprotected sex intentions. These findings support a cognitive mediation model of women's sexual decision making, and identify how individual and situational factors interact to shape alcohol's influences on cognitive appraisals that lead to risky sexual decisions. This knowledge can inform empirically-based risky sex interventions.

Keywords: relationships, cognitive appraisals, sexual risk taking, alcohol myopia

Effects of Relationship Motivation, Partner Familiarity, and Alcohol on Women's Risky Sexual Decision Making

The proportion of AIDS cases composed of women in the USA has more than tripled since 1985 from 8% to 27%. In nearly 80% of cases, women contract HIV through sexual intercourse with men (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2007). Currently the most effective and widely used method of protection against sexual HIV transmission is the male condom. This fact presents a challenge to women's self-protection for the obvious reason that women do not wear male condoms. Thus, women's condom use is predicated on their ability to ensure that their sexual partners wear them. Because of this, it is crucial to understand the process through which women decide when and how to negotiate condom use during heterosexual encounters.

A woman's condom negotiation during a sexual interaction occurs within a specific situational context. A woman also brings into the sexual encounter her own individual characteristics and motivations that are likely to influence her decision making and behavior. Thus, it is important to understand how women's traits and attitudes interact with situational factors to influence sexual decisions and behaviors during a sexual encounter. Previous research has demonstrated that women's risky sex decisions and behavior can be influenced by in-the-moment alcohol consumption (Abbey, Saenz, Buck, Parkhill, & Hayman, 2006), partner familiarity (Williams, Kimble, Covell, Weiss, Newton, & Fisher, 1992), and relationship motives (Amaro, 1995). Nonetheless, little research has addressed whether these factors synergistically influence risky sex decisions. The current study addresses how a woman's familiarity with a man can interact with her relationship motivation and alcohol consumption to influence sexual decision making and condom negotiation.

Cognitive Mediation Model of Women's Sexual Decision Making

Existing social psychological theories (e.g., the Theory of Reasoned Action, Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980; Theory of Planned Behavior, Ajzen, 1991; Health Belief Model, Rosenstock, 1974; Social Learning Theory, Bandura, 1986; and the AIDS Risk Reduction Model, Catania, Kegeles, & Coates, 1990) have been widely used to predict overall patterns of sexual risk-related behaviors such as one's frequency of condom use during a given time-frame (see Fisher & Fisher, 2000; Sheeran, Abraham, & Orbell, 1999 for reviews). Although these theories have advanced our understanding of general risky-sex behavior patterns, individuals make decisions about sexual risk behavior within a particular situation. Therefore, it is important to understand the process through which individuals make decisions during specific sexual encounters. The present study addresses gaps in existing theory and knowledge regarding in-the-moment processes through which sexual decision making and condom negotiation occur.

To address the theoretical gap, the current study tests a Cognitive Mediation Model of Women's Sexual Decision Making developed by Norris, Masters, and Zawacki (2004). This model proposes that a woman's cognitive processing of information within a sexual situation mediates the influences of background and situational factors on her decision to negotiate condom use and engage in protected sex. The model posits that a woman brings a variety of short and long term goals into a sexual situation, including sexual pleasure, sexual safety, and relationship goals. Although all of these goals are important in understanding women's sexual decisions, the present study focuses on the role of relationship goals. The Cognitive Mediation Model is rooted in Cognitive-Motivational-Relational Theory (Lazarus, 1991) in that it conceptualizes women's cognitive processing of information as a series of primary and secondary appraisals of the immediate situation. When a woman enters a sexual encounter, she makes primary appraisals through which she evaluates the situation with regard to whether it is relevant to her goals. Say, for example, a woman has a goal to develop a romantic relationship. Through primary appraisals, she determines whether her interaction with the man has the potential to develop into a relationship. Through secondary appraisals, the woman then evaluates whether the situation can lead to the realization of her goals. In terms of relationship goals, secondary appraisals involve evaluating the degree to which having sex in the situation will facilitate the goal of beginning a relationship with the man. When a woman who is highly motivated to establish a relationship enters a sexual encounter, her desire to facilitate a relationship may compete with a desire to avoid the risks of unprotected sex with a first-time partner, resulting in decisional conflict. For a relationship-motivated woman who appraises sex in the situation as facilitating a relationship with the man, this decisional conflict may be resolved by engaging in behavior that she perceives as enhancing the likelihood of a relationship, but which might be sexually risky.

Relationship Motivation and Sexual Risk Taking

Relationship concerns have been established as important determinants of women's motivation to negotiate condom use and to decline to have risky sex (Afifi, 1999; Amaro, 1995; Smith, 2003; Umphrey & Sherblom, 2007). Negotiation of condom use with a sexual partner can be influenced at least in part by how strong a woman's relationship goals are, that is, how motivated she is to pursue a relationship. A woman with strong relationship goals may be reluctant to negotiate condom use because of concern that it could threaten a potential relationship with her sexual partner by diminishing his opinion of her. She may be wary that insisting on condom use will imply that she has engaged in past risky behavior or will be interpreted by her partner as a judgment that he has (Hammer, Fisher, Fitzgerald, & Fisher, 1996; Wingood, Hunter-Gamble, & DeClemente, 1993). Further, she may wish to avoid actual discussion of her own or her partner's past sexual behavior and relationships for concern that it might damage their impressions of each other (Baxter & Wilmot, 1985; Hammer et al., 1996). She also may want to avoid violating dating gender roles by seeming too sexually forward in broaching the subject of condom use (Gavey & McPhillips, 1999; Impett, Schooler, & Tolman, 2006).

Also, it is a common belief that condoms interfere with feelings of intimacy and warmth (Juran, 1995). A woman with strong relationship goals in general may be motivated to achieve feelings of intimacy and warmth within the sexual encounter and may perceive condom negotiation and use as potential barriers to establishing feelings of intimacy. For these reasons, a woman's own motivation to pursue a relationship may shift her focus in a sexual encounter from self-protective condom negotiation to relationship facilitation. A woman's motivation to facilitate a relationship is likely to affect not only whether she is willing to negotiate condom use, but how she negotiates it. A woman who is highly relationship-motivated is likely to couch a condom request in a manner that matches her relationship goals and that she perceives as least threatening to a potential relationship.

Familiarity of Partner and Sexual Risk Taking

Research on sexual risk appraisal has shown that increased familiarity with a person, that is, being better acquainted with him or her, encourages judgments that the person is low in HIV risk (Swann, Silvera, & Proske, 1995; Williams et al., 1992). For example, Swann et al. (1995) experimentally manipulated the familiarity of a videotaped target person and found that receiving one minute of information about that person, even though the information was irrelevant to HIV status, increased participants’ feelings of familiarity and liking and decreased appraisals of HIV risk (Swann et al., 1995). Similarly, in focus groups with undergraduates, Williams et al. (1992) found that potential sexual partners whom participants knew and liked were not perceived to be risky, even when participants knew nothing about their HIV risk. Familiar partners may be perceived as safe due to person perception biases and the use of incorrect heuristics to estimate a sexual partner's potential HIV risk. For example, familiarity may influence HIV risk perceptions via social projection bias, which is the tendency to expect similarities between ourselves and others, especially those who are familiar to us (Robbins & Krueger, 2005). Most young adults consider themselves at low risk of HIV infection (Fromme, D'Amico, & Katz, 1999; Hammer et al., 1996) and may socially project this perception to familiar others. This research suggests that familiarity with a potential sexual partner can act as a situational cue that the partner is low in sexual risk and therefore condom use is not warranted. The present study operationalized partner familiarity as degree of acquaintanceship as defined by duration of acquaintance, frequency of interaction, and social network familiarity (Starzyk, Holden, Fabrigar, & MacDonald, 2006).

Alcohol and Sexual Risk Taking

Alcohol has emerged as an important factor in sexually transmitted HIV infection. The relationship between alcohol consumption and sexual HIV risk has been studied extensively through survey methods. Survey studies that examine the global association between frequency of alcohol consumption and frequency of risky (i.e., unprotected) sex have found a strong, positive relationship between the two (Hines, Snowden, & Graves, 1998; Santelli, Brener, Lowry, Bhatt, & Zabin, 1998). Studies that assess drinking and unprotected sex during a specific incident have been less consistent in finding a positive relationship (Cooper, 2002; Leigh, 2002; Morrison, Gillmore, Hoppe, Gaylor, Leigh, & Rainey, 2003). Recent reviews of the event-level literature suggest that the effect of intoxication on condom use is moderated by characteristics of individuals and situational variables, such as relationship factors (Cooper, 2006).

Although survey studies have contributed valuable information about alcohol's relationship to HIV risk, experimental research is needed to establish causality of alcohol effects (Hendershot & George, 2007). Laboratory experiments in which participants are administered alcohol have established that intoxication can increase intentions to have unprotected sex (MacDonald, Fong, Zanna, & Martineau, 2000; MacDonald, Zanna, & Fong; 1996; Maisto, Carey, Carey, Gordon, Schum, & Lynch, 2004), decrease perceptions of its negative consequences (Fromme, D'Amico, & Katz, 1999), and impair verbal condom negotiation skills (Maisto, Carey, Carey, & Gordon, 2002; Maisto, Carey, et al., 2004; Maisto et al., 2004b). Previous experimental research has identified individual differences that interact with intoxication to influence sexual risk taking decisions, such as cognitive reserve (Abbey et al., 2005a) and sexual fears (Stoner, George, Peters, & Norris, 2007). Recent research also has found that individual differences such as beliefs about the risks and benefits of unsafe sex can influence attention to sexual arousal, thereby indirectly increasing the likelihood of risky sexual decisions (Davis, Hendershot, George, Norris, & Heiman, 2007).

It is theorized that alcohol influences sexual decision making and behavior by impairing the amount of information an individual can process. Alcohol myopia models (Steele & Josephs, 1990; Taylor & Leonard, 1983) posit that intoxication narrows the focus of attention to salient situational cues that impel risky behaviors such as unprotected sex. For the reasons described previously, high familiarity with a potential sexual partner is likely to act as a salient impelling cue encouraging unprotected sex. Alcohol myopia models would predict that compared to when sober, when intoxicated a woman's attention will be more narrowly focused on the salient impelling cue of high familiarity. Thus, she will be less inclined to request condom use and will be more likely to engage in unsafe sex than when sober.

In the context of a potential sexual encounter, a woman who is motivated to pursue a relationship is likely to be attentive to cues that are relevant to relationship potential, such as her degree of familiarity with the potential partner (Snyder & Stukas, 1999). Compared to women low in relationship motivation, those high in this attribute might be more impelled by familiarity cues. In this way, the combination of motivation to pursue a relationship, being highly familiar with a man, and intoxication may particularly result in risky sexual decision making.

Overview of Current Study and Hypotheses

The present study builds on previous research by integrating individual and situational factors with alcohol's effects on risky sexual decisions. Further, it examines these effects on specific cognitive appraisals that may facilitate sexual risk taking, as proposed in the Cognitive Mediation Model.

This experiment examined the effects of women's relationship motivation, partner familiarity, and alcohol consumption on women's sexual decision making and condom negotiation, using a 2 × 4 between-subjects factorial design. Relationship motivation was measured as a subject variable. Participants were randomly assigned to partner familiarity condition (low, high), and to alcohol consumption condition (high dose, low dose, no alcohol control, or placebo control). A placebo was included as an additional control condition to verify that alcohol's effects were due to actual alcohol consumption rather than expectations about alcohol's effects. Some early sexuality studies reported significant placebo effects (e.g., George & Marlatt, 1986), but the bulk of recent sexuality research has not (e.g., Abbey et al., 2000; Abbey, Zawacki, & Buck, 2005; Fromme et al.,1999; MacDonald et al., 1996; Norris & Kerr, 1993) After consuming their beverages, participants read and projected themselves into a hypothetical scenario depicting a sexual encounter with a man who was depicted as either low or high in familiarity. As the story unfolded, women were asked the likelihood that they would engage in various condom negotiation strategies and whether they would have sex when they discovered that no condom was available. The story was paused periodically to assess dependent measures.

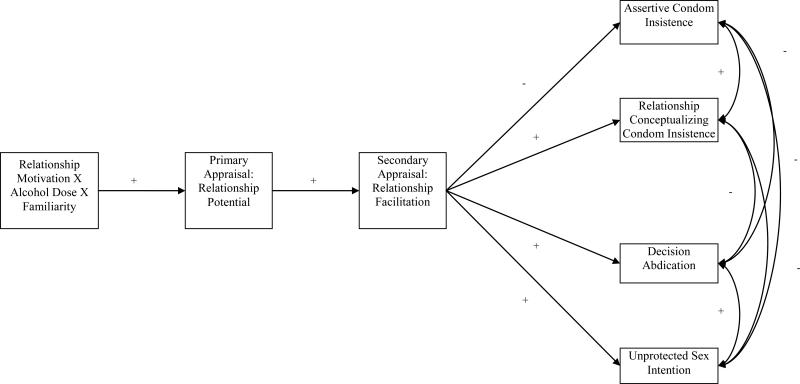

The Cognitive Mediation Model, shown in Figure 1, proposes that participants’ primary and secondary appraisals of information within the immediate sexual situation will mediate the influences of background and situational factors on the decision to negotiate condom use and engage in protected sex. The background factor of relationship motivation and the randomly assigned situational factors of familiarity level of partner and alcohol dose are hypothesized to affect primary appraisal of relationship potential. As noted earlier, women with strong relationship motivation are theorized to be attentive to cues that are relevant to relationship potential, such as familiarity. Hence, compared to women low in relationship motivation, those high in relationship motivation were hypothesized to be more influenced by the impelling high familiarity cue. This influence was hypothesized to be further exacerbated by intoxication, according to alcohol myopia models. Therefore, it was hypothesized that the independent variables of relationship motivation, partner familiarity, and alcohol dose would interact such that high motivation to pursue a relationship, high familiarity with a man, and intoxication would result in the highest primary appraisal of relationship potential.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized relationship model.

Primary appraisal of relationship potential was hypothesized to be positively related to secondary appraisal of relationship facilitation, i.e., whether having sex with the man would facilitate a relationship with him. In turn, secondary appraisal of relationship facilitation was hypothesized to be negatively related to the likelihood of assertive condom requests and positively related to the likelihood of making condom requests that are couched in terms of a relationship, abdication of sexual decision making to the partner, and intentions to engage in unprotected sex.

Method

Participants

Participants were 161 women ages 21 to 35 (M = 25.02 years, SD = 3.85) recruited from the community as well as a university located in a large Pacific Northwest city. Thirty-four percent were full- or part-time students. The majority of the sample (64.6%) identified their race as European American/White, 14.3% as African American/Black, 12.4% as multiracial, 2.5% as Asian American/Pacific Islander, and 6.2% as “other.” Of the total sample 10.6% identified their ethnicity as Hispanic or Latina. Sixty three percent were employed, 53% of these full-time. Most (71.5%) had annual incomes of less than $21,000.

Posted flyers and advertisements in local newspapers recruited single female social drinkers between the ages of 21 and 35 to participate in a study on social interactions between men and women. Potential participants who called the telephone number provided were screened to ensure they fit the study's criteria. In order to ensure that participants would find the experimental story relevant to their current dating status and lifestyle, women were excluded who were in a committed, exclusive relationship, had no interest in a relationship with a man, or had never had consensual vaginal sex with a man. Participants also were required to meet federal ethical guidelines regarding alcohol administration to human subjects (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [NIAAA], 2005). Participants were excluded for medical conditions and medication usage that contraindicate alcohol consumption. Women who reported a history of problem drinking or drank more than forty drinks per week were excluded, as were women who drank less than one drink per week. Participants reported drinking an average of 10.19 (SD = 7.83) drinks per week. Participants were instructed not to eat for three hours prior to the session and not to drive to the laboratory. Study compensation was increased from $10 to $15 per hour partway through data collection in order to increase participant recruitment, and this increase was distributed equally across experimental conditions.

Procedure

The session consisted of two parts. First participants completed a set of background questionnaires, then completed the experimental protocol. A female experimenter greeted each participant, seated her in a private room with a desk-top computer, checked her photo identification to verify her identity and age, and administered her a breathalyzer test (Alco-Sensor IV) to document that her blood alcohol level (BAL) was at .00%. The experimenter then obtained informed consent and left the room so that the participant could complete the computerized questionnaires in privacy. After the participant finished the questionnaires, the experimenter debriefed her about the questionnaires and obtained informed consent for the experimental part of the study.

After the participant completed the beverage administration procedure (described below), she read the stimulus story and completed the dependent measures in privacy. Then the participant was fully debriefed, paid, given resource materials on STDs and HIV, and released. Participants who drank alcohol were situated in a comfortable room until their BAL fell below .03%. Approximately two weeks after the laboratory session, participants were offered an additional $5 for returning a mailed follow-up survey that assessed the effects of participation. No participants reported adverse effects.

Beverage administration

Participants were randomly assigned to one of four alcohol conditions: high dose alcohol (target BAL .08%), low dose alcohol (target BAL .04%), control, or placebo. Alcohol doses were .682 g/kg body weight for the .08% target BAL and.325g ethanol/kg for the .04% target BAL. One-hundred proof vodka was mixed with orange juice in a 1:4 ratio. Control participants drank an equivalent amount of pure orange juice. To prevent experimenter bias, in the alcohol and placebo conditions a supervisor instructed the experimenter to use one of four vodka bottles the contents of which were unknown to the experimenter. Each vodka bottle contained either 100-proof vodka (alcohol conditions) or flat tonic water plus a small amount of vodka (placebo condition). Lime juice laced with a small amount of vodka was added to the beverages, and beverage cups were misted with 100-proof vodka. The beverage was mixed in full view of the participant who was requested to consume each of three cups of the beverage in three minutes. Prior to drinking, the participant rinsed with mint mouthwash under the pretext that this would allow a more accurate breathalyzer reading. This procedure aimed to prevent placebo participants from recognizing the lack of alcohol in their beverage, but was standardized across all beverage conditions. In the alcohol conditions, after a 4 to 5 minute blood alcohol absorption period, participants were breathalyzer tested every 2 to 5 minutes until they reached a criterion BAL of .025 (low dose) or .055 (high dose). These criterion BALs ensured that participants began reading the story while their BALs were ascending and near the target. Each control participant was temporally “yoked” to an alcohol participant to control for individual variation in time to reach criterion BAL. The yoked control participant was breathalyzer tested at the same time point and began reading the story after the same number of minutes as her counterpart in the alcohol condition (Giancola & Zeichner, 1997). Each placebo participant was yoked to low alcohol participant. A yoked placebo was not included for the high alcohol participants because successful placebo deception is difficult for high doses (Sayette, Breslin, Wilson, & Rosenblum, 1994). The alcohol condition cell sizes were as follow: low dose n = 32; high dose n = 32; low dose control n = 34; high dose control n = 30; placebo n = 33.

Materials

Experimental story

Women were randomly assigned to read an experimental story that culminated in a sexual encounter with a man who was depicted as either low (n = 80) or high in familiarity (n = 81). The story depicted a social interaction between a woman and a man to whom the woman was very attracted, but with whom she had never had sex. The story was approximately 2200 words long and was written in the second person - “Your good friend Anita invites you...” - to encourage the participant to experience the encounter as if it were actually happening to her. Participants were instructed to project themselves into the story at their current level of intoxication. The beverages consumed by the woman and the man in the story matched the participant's alcohol condition. That is, the story couple was depicted as drinking soft drinks for participants in the control condition, and alcoholic drinks for participants in the two alcohol conditions and the placebo condition.

The story opened with a conversation between the woman (i.e., the participant) and a female friend in which the friend invited the woman to the friend's boyfriend's place to watch movies. The friend mentioned that Nick, the boyfriend's roommate, would be there and the woman responded by saying she found him attractive and was interested in getting to know him. The evening continued with Nick and the woman watching movies, talking, and drinking either alcoholic or nonalcoholic beverages depending on the participant's alcohol condition. This first part of the story provided the background for the woman's interactions with Nick later in the story.

Women's level of familiarity with Nick was experimentally manipulated in the stimulus story. The familiarity manipulation reflected three dimensions of acquaintanceship: social network familiarity, frequency of interaction, and duration of acquaintance (Starzyk et al., 2006). In the high familiarity condition the story depicted that Nick was a long-established roommate and best friend of the friend's boyfriend, that the woman in the story had met and chatted with Nick on several occasions, and that the woman and Nick discovered they went to the same high school during which time they had never met personally, but had mutual classes and acquaintances. In the low familiarity condition, it was depicted that Nick was the new roommate of her friend's boyfriend and that the woman in the story had met Nick and chatted with him on one previous occasion.

The story was paused at several timepoints to assess participants’ responses. The first timepoint - assessment of primary relationship potential appraisals - occurred when the woman and Nick were alone in Nick's room, and Nick kissed her on the cheek. The second timepoint – assessment of secondary appraisals concerned with relationship facilitation - occurred when the couple engaged in petting while partially clothed. At this point the story mentioned that the woman was on the Pill to remove pregnancy risk as the main reason for condom use. The third section of the story depicted progressing sexual acts until the couple was undressed, and the couple realized they could not find a condom. At the end of the story, Nick suggested that they engage in vaginal penetration without a condom. Here the woman's responses were assessed regarding condom use insistence, abdicating the condom use decision to the man, and unprotected sex intentions.

Measures

Relationship motivation

The Social Dating Goals Scale (Sanderson & Cantor, 1995), a 13-item questionnaire that assesses goals to establish and maintain intimate romantic relationships, was used to measure relationship motivation. All items began with the stem “In my dating relationships I try to...” and included items such as: consistently date someone, and date people with whom I might fall in love. Items were rated on 5-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) with higher scores indicating stronger relationship motivation. Reliability analyses indicated that dropping a single item, “determine what I want in a future relationship” increased alpha from .59 to .69. The revised 12-item scale correlated with the original scale r = .98, p < .001, and was retained for analyses (M = 3.25; SD = 0.47).

Primary cognitive appraisal: Relationship potential

Primary cognitive appraisals were assessed after Nick first kissed the woman on the cheek but they had not proceeded to fondling or disrobing. These questions focused on the early expectations and desires of the women envisioning a potential relationship with Nick. This measure was composed of two items (M = 2.98; SD = 1.39; Cronbach's α = .89): How interested are you in a long-term relationship with Nick?; and How likely are you to have a long-term relationship with Nick? Responses options were 0 (Not at all interested) to 6 (Extremely interested) for the first item and 0 (Definitely unlikely) to 6 (Definitely likely) for the second item.

Secondary cognitive appraisal: Relationship facilitation

These items were designed to assess women's relationship-based reasons for having sex. The assessment occurred after Nick and the woman had engaged in partially clothed petting, but had not yet realized no condom was available. This measure consisted of three items (M = 1.85; SD = 1.43; Cronbach's α = .75) assessed on 7-point scales from 0 (I would not consider it at all) to 6 (I would consider it extremely): We could end up being boyfriend and girlfriend if we have sex now, Maybe this is the right guy for me so we should go ahead and have sex now, and He'll like me more if we have sex now.

Assertive condom insistence

Participants’ endorsement of assertively insisting upon the use of a condom in the story was assessed after the couple realized that there was no condom available and the man suggested having sex without one. Three subscales adapted from the Condom Influence Strategy Scale (Noar, Morokoff, & Harlow, 2002) assessed likelihood of using three different assertive condom insistence strategies, rated on 7-point scales ranging from 0 (definitely unlikely) to 6 (definitely likely): direct request (e.g., Ask that we use condoms during sex), withholding sex (e.g., Tell Nick that I will not have sex with him if we do not use condoms, and providing STD risk information (e.g., Tell Nick that we need to use condoms to protect ourselves from AIDS). Each subscale was composed of three items. Scores across all nine items were averaged to obtain an overall measure of assertive condom insistence (M = 4.45; SD = 1.53; Cronbach's α = .93).

Relationship conceptualizing condom insistence

Participants endorsement of providing relationship based reasons for using a condom in the story were assessed after the couple realized that there was no condom available and the man suggested having sex without one. Relationship conceptualizing items were rated on 7-point scales ranging from 0 (definitely unlikely) to 6 (definitely likely): Tell Nick that using a condom would really show how he cares for me; Tell Nick that if we want to trust one another, that we should use condoms; Let Nick know that using a condom would show respect for my feelings; and Tell Nick that it would really mean a lot to me if he would use a condom. Scores were averaged across the four items (M = 3.23; SD = 1.94; Cronbach's α = .88).

Decision abdication

Two questions assessed the extent to which participants would let Nick decide what to do next after he suggested having sex without a condom (M = 1.10; SD = 1.50; Cronbach's α = .82) on 7-point scales ranging from 0 (definitely unlikely) to 6 (definitely likely): Let Nick decide how far to go, and Go along with what Nick wants.

Unprotected sex intention

Three questions assessed the likelihood of having unprotected sex after Nick suggested doing so (M = 1.84; SD = 1.79; Cronbach's α = .85) rated on 7-point scales from 0 (definitely unlikely) to 6 (definitely likely): At this point in your encounter with Nick, how likely are you to have sex with Nick?; How likely are you to rub your clitoris against Nick's penis without a condom?; and How likely are you to allow Nick to put his penis inside your vagina without a condom?

Results

Manipulation Checks

Two questions, rated on 0-6 scales, assessed the realism of the experimental story: How realistic was the story? (M = 4.73, SD = 1.73); and How well were you able to project yourself into the story? (M = 4.24, SD = 1.38). Participants seemed to find the story realistic and were able to relate well to it. To ensure that participants understood the familiarity manipulation, women were asked, “How familiar with Nick were you at the beginning of the story?” rated on a 7-point scale from 0 (not at all) to 6 (extremely familiar). Participants in the high familiarity condition (M = 2.59, SD = 1.03) reported significantly higher familiarity than participants in the low familiarity condition (M = 0.93, SD = 0.78), t(159) = -11.56, p < .001.

Two one-way ANOVAs were conducted to check the alcohol manipulations. First, a one-way ANOVA of achieved BAL by beverage condition was significant, F(4, 156) = 29.62, p < .001. Post-hoc LSD comparisons found that low dose participants (M = .034, SD = .008) achieved a higher BAL than control and placebo participants (Ms = .000, SDs = .000) and that high dose participants (M = .064, SD = .009) achieved a higher BAL than low dose, control, and placebo participants. Second, to check the placebo manipulation, perceived intoxication was assessed just before participants began reading the experimental story with the question “How intoxicated do you feel right now?” rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all intoxicated) to 6 (extremely intoxicated). A one-way ANOVA of perceived intoxication by beverage condition was significant, F(4, 156) = 113.92, p < .001. Results of post-hoc LSD comparisons found each of the four alcohol conditions significantly different from one another in descending order: high dose (M = 3.91, SD = 0.93), low dose (M = 3.09, SD = 1.07), placebo (M = 2.09, SD = 1.16), and control (M = 0.05, SD = 0.38).

Overview of Data Analytic Strategy

First, correlations among variables were conducted to assess bivariate relations. Then, to test for the hypothesized interaction between alcohol dose, placebo condition, level of familiarity, and relationship motivation on the primary appraisal of relationship potential, a hierarchical multiple regression was performed. Based on these preliminary analyses, a path analysis model (Figure 1) was tested to examine the theoretical model.

Correlations

Bivariate correlations among the variables appear in Table 1. Relationship motivation was positively associated with primary appraisal of relationship potential, which was positively associated with secondary appraisal of relationship facilitation. Secondary appraisal was differentially related to condom insistence strategies, and was positively associated with decision abdication and intention to have unprotected sex. Assertive condom use insistence, relationship conceptualizing condom insistence, decision abdication and unprotected sex intention were intercorrelated in the expected directions.

Table 1.

Bivariate Correlations among Measured Variables (N = 161)

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Relationship Motivation | -- | .27*** | .16* | .01 | .01 | .13 | .09 |

| 2. Primary Appraisal: Relationship Potential | -- | .33*** | -.05 | .03 | .11 | .10 | |

| 3. Secondary Appraisal: Relationship Facilitation | -- | -.05 | .18* | .32*** | .21** | ||

| 4. Assertive Condom Insistence | -- | .65*** | -.48*** | -.61*** | |||

| 5. Relationship Conceptualizing Condom Insistence | -- | -.18* | -.26*** | ||||

| 6. Decision Abdication | -- | .65*** | |||||

| 7. Unprotected Sex Intention | -- |

Note:

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Multiple regressions

According to the Cognitive Mediation Model, the independent variables of alcohol consumption, placebo, familiarity, and relationship motivation were hypothesized to influence primary appraisal. A hierarchical multiple regression was conducted to examine main effects and interactions between the manipulated variables and relationship motivation on the primary appraisal of relationship potential. Alcohol dose, placebo, familiarity condition, and relationship motivation were entered on Step 1, five two-way interaction terms between either alcohol dose or placebo, familiarity condition, and relationship motivation were entered on Step 2, and two three-way interaction terms between alcohol dose or placebo, familiarity condition, and relationship motivation were entered on Step 3.

Step 1 containing the main effects was significant, R2 = .08, F(4, 155) = 3.49, p < .01, with a significant coefficient for the main effect of relationship motivation (β = .27, p < .001). Step 2 containing the two-way interactions was not significant, R2 = .10, F(9, 150) = 1.87, p = n.s., and failed to predict additional variance, ΔR2 = .02, ΔF(5, 150) = 0.60, p = n.s.. Step 3 containing the three-way interactions was significant, R2 = .14, F(11, 148) = 2.19, p < .05, and predicted significant additional variance, ΔR2 = .04, ΔF(2, 148) = 3.39, p < .05, with a significant coefficient for the relationship motivation by alcohol dose by familiarity interaction term (β = .36, p < .05).

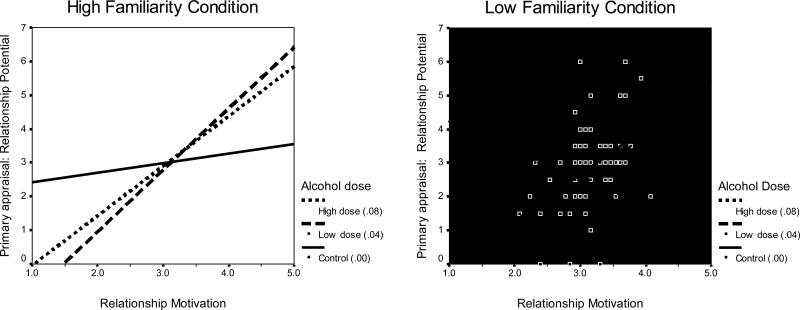

The pattern of the three-way interaction between alcohol dose, relationship motivation, and familiarity condition on primary appraisal of relationship potential is presented in Figure 3. Post-hoc analyses found a significant positive association between primary appraisal of relationship potential and relationship motivation among women who received a low or high dose of alcohol in the high familiarity condition, and among women in the low familiarity/no alcohol condition. No effect for relationship motivation was found among women in the low familiarity/low dose alcohol condition or the high familiarity/no alcohol condition. There was a negative association between primary appraisal of relationship potential and relationship motivation among women in the high alcohol dose/low familiarity condition.

Figure 3.

Graph of interaction among relationship motivation, alcohol dose, and familiarity condition

Model testing

Path analysis using Mplus statistical modeling software for Windows (version 4.0, Muthén & Muthén, 2004) with maximum likelihood estimation (ML estimator) was used to test the hypothesized model shown in Figure 1. No significant effects involving the placebo condition were found in preliminary analyses, thus the placebo control term was not included in model testing.

Based on preliminary analyses, the following path model was tested: the outcome responses of assertive condom insistence, relationship conceptualizing condom insistence, decision abdication, and unprotected sex intention were regressed on the secondary appraisal of relationship facilitation. The secondary appraisal of relationship facilitation was regressed on the primary appraisal of relationship potential. Finally, the primary appraisal of relationship was regressed on the interaction between relationship motivation, familiarity level, and alcohol dose. The primary appraisal of relationship was also regressed on the main effects and two-way interactions between relationship motivation, familiarity level, and alcohol dose. Estimation of these effects allowed for adequately assessing the effect of the three-way interaction in the presence of lower level effects and replicating the three-way interaction effect found in the preliminary multiple regression results. Correlations were estimated among the outcome variables of assertive condom insistence, relationship conceptualizing condom insistence, decision abdication, and unprotected sex intention.

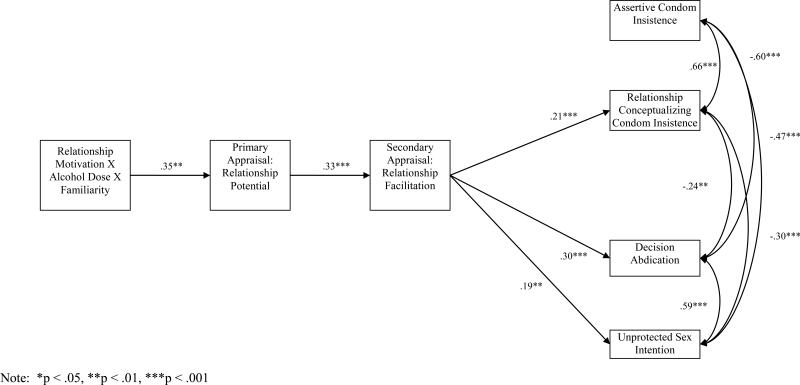

The structural path model in Figure 1 fit the data well, χ2(39) = 46.087, p = .21, CFI = .978, TLI = .968, RMSEA = .034, SRMR = .051. The non-significant path between secondary appraisal of relationship facilitation and assertive condom insistence was fixed to zero in the final model (Figure 2). All main effects and two-way interaction paths between relationship motivation, familiarity level, and alcohol dose on the primary appraisal of relationship potential were left free to vary to ensure proper estimation of the effect of the three-way interaction on the primary appraisal. The significant higher order three-way interaction subsumed interpretation of lower order effects (Cohen, Cohen, Aiken, & West, 2003). The final model fit the data well, χ2(40) = 46.477, p = .22., CFI = .980, TLI = .971, RMSEA = .032, SRMR = .052. Chi-square difference testing was used to compare the first model tested to the final model. Results indicated that the final model fit the data as well as the hypothesized model, χ2(1) = 0.390, p = .53. All of the paths that were free to vary in the final model remained significant. Inspection of modification indices indicated that there were no significant areas of misfit.

Figure 2.

Final relationship model with standardized estimates.

The final model accounted for 4% of the variance in unprotected sex intention, 9% of the variance in decision abdication, 5% of the variance in relationship conceptualizing condom insistence, 11% of the variance in secondary appraisal of relationship facilitation, and 12% of the variance in the primary appraisal of relationship potential.

Following procedures outlined by Bryan and colleagues (Bryan, Schmiege, & Broaddus, 2007), we tested the significance of the indirect effects of the interaction term between alcohol dose, familiarity level, and relationship motivation on the outcomes through the primary and secondary appraisals. The indirect effect for the path from the interaction predictor to relationship conceptualizing condom insistence through the cognitive appraisals was significant (β = .03, p < .05). Likewise, there was a significant indirect effect for the path from the interaction predictor to decision abdication through the cognitive appraisals (β = .03, p <.05). Finally, there was a trend for the indirect effect from the interaction predictor through the cognitive appraisals to unprotected sex intention (β = .02, p = .06).

Discussion

This study tested the recently developed Cognitive Mediation Model of Women's Sexual Decision Making (Norris et al., 2004), specifically with regard to the influences of relationship motivation, partner familiarity, and alcohol consumption on the cognitive mediation process. The study's hypotheses were largely supported. Participants’ primary and secondary relationship appraisals mediated the combined effects of women's relationship motivation, partner familiarity, and intoxication on condom insistence, sexual decision abdication, and unprotected sex intention. Alcohol intoxication interacted with relationship motivation and partner familiarity level to influence primary appraisal of relationship potential. These findings advance theory in the areas of sexual decision making and risk taking by providing support for the Cognitive Mediation Model, and by demonstrating that particular combinations of individual and situational differences can moderate alcohol's influence on specific cognitive appraisals that facilitate risky sexual decisions.

In the path model, relative to lower primary appraisal, greater primary relationship potential appraisal resulted in increased secondary appraisal regarding whether having sex in the situation would facilitate a relationship, which in turn led to more abdication of sexual decisions to the man, and increased intention to engage in unprotected sex. Women's initial assessment of a potential sexual risk-taking situation triggered a chronology of appraisals and decisions that resulted in risky sex intentions. Primary appraisals provide a key phenomenon for future study as a potential risky-sex intervention point. Unprotected sex intentions were positively related to sexual decision abdication but negatively related to relationship-oriented condom insistence. This pattern suggests that pathways of both sexual risk and protection exist for highly relationship-motivated women, and that these pathways may diverge at the decision to negotiate condom use versus deferring to a partner's preference. Research determining what factors differentially influence women's sexual decision abdication versus relationship-oriented condom negotiation can build on the present findings.

Results also revealed an interesting pattern of results regarding women's intentions to engage in different types of condom negotiation strategies. Consistent with hypotheses, stronger secondary relationship appraisal increased women's intention to engage in condom insistence that was framed in terms of a relationship, such as telling the man that using a condom would really show how he cared for her. This suggests that women's relationship motivations indirectly influence not only their overall likelihood to negotiate condoms, but also their selection of condom negotiation strategies. Although relationship-motivated women may refrain from engaging in condom negotiation strategies that they are wary will undermine their relationship goals, perhaps they are likely to use strategies that communicate relationship interest and potential. Contrary to hypotheses, women's secondary relationship appraisal did not decrease endorsement of assertive insistence on condom use directly although it was positively related to relationship-oriented condom insistence. This indicates that women who use relationship-oriented condom insistence strategies may view these strategies as an effective means of convincing their partners to use condoms. Research is needed to further elucidate nuances in women's selection, use, and effectiveness of different condom negotiation strategies.

Intoxicated women who were strongly motivated to pursue a relationship perceived the most relationship potential when projecting themselves into an interaction with a highly familiar man. As predicted by alcohol myopia models, intoxication appeared to influence women's reaction to a salient, impelling potential relationship cue: high familiarity of partner. Intoxicated women's reactions to a low familiarity partner were more complex. There was a significant, negative relationship motivation effect among high-dose drinkers – those with stronger relationship motivation perceived less relationship potential with a relatively unfamiliar man than did women with weaker relationship motivation. One interpretation is that these women may have perceived that sex with a relatively unfamiliar partner after drinking was unlikely to result in a relationship. Interpreted through the lens of alcohol myopia theory this may indicate that, compared to sober women, highly intoxicated women with strong relationship motivation reacted more extremely to a salient cue inhibiting relationship potential in the situation: low familiarity of partner. That is, within the high-alcohol group, women with high relationship motivation focused on the decreased relationship potential of the less familiar man. There was no significant relationship motivation effect in the low alcohol dose condition, perhaps because the lower level of intoxication was not sufficient to induce alcohol myopia. The extent to which level of intoxication interacts with individual and situational factors in impairment of women's sexual decision making is an important question for future research. Among sober women judging the low familiarity man, results were in line with what might generally be expected: those with stronger relationship motivation perceived more relationship potential compared to women with weaker relationship motivation.

Theoretical Contributions

These findings contribute to current theory and literature regarding risky sexual decisions in several ways. First, these findings and their support of the proposed Cognitive Mediation Model demonstrate that researchers need to consider additional theoretical models to better understand risky sex behavior. Existing theories (e.g., the Health Belief Model Theory of Planned Behavior and the AIDS Risk Reduction Model) have focused on predicting the outcomes of general tendency to use condoms and overall patterns of sexually risky behavior such as lifetime number of unprotected sexual partners or frequency of condom use in the past three months. Further, they have concentrated on person variables such as attitudes, perceived social norms, behavioral intentions, and perceived self-efficacy as predictors. Although these existing theories have enhanced our understanding of how individual differences affect general patterns of risky behavior, they leave theoretical gaps in understanding sexually risky behavior within particular situations and the in vivo processes through which sexual decision making and condom negotiation occur. They also overlook important physiological states, like intoxication, in which many of these decisions are made. The present study helps to fill this knowledge gap by providing empirical support for a model explicating women's cognitive processing of information within a sexual situation and how it mediates the influences of her background, situation, and physiological state on unfolding decisions to negotiate condom use and engage in unprotected sex.

In order to further understanding of risky sex decisions and behavior, future research is needed that integrates person-centered theories such as the Theory of Planned Behavior with situation and state-focused theories like the Cognitive Mediation Model. Specifically, research is needed that examines the ways in which person-centered theory constructs may operate within specific situational contexts and physiological states. To do this, researchers need to employ study designs that incorporate assessment of person-centered theory variables with experimental protocols manipulating situational and physiological state factors. This approach can address unanswered research questions about how person-centered factors such as attitudes and normative beliefs interact with alcohol intoxication in determining risky sex decisions. Interactions with other physiological states such as sexual arousal and mood also need to be investigated. The Cognitive Mediation Model makes an important theoretical contribution by providing a theoretical framework for investigating these new research topics.

Second, these findings contribute to the risky sex literature by building our understanding of relationship factors. Although the sexual risk literature has suggested that relationship factors play an important role in women's risky sexual behavior, the mechanisms underlying their role remain unclear. This study explicates the role of a particular relationship factor – relationship motivation – in risky sexual decisions by women, and how the situational factors of intoxication and partner characteristics can potentiate the effect of relationship motivation.

Third, these results bear on contemporary theoretical controversy regarding alcohol's involvement in sexual risk taking behavior. Many event-level studies examining the effect of drinking on condom use during a specific sex event find no direct association between the two (Cooper, 2006; Gillmore et al., 2002; Morrison et al., 2003). The current findings, and the Cognitive Mediation Model that they support, elucidate this theoretical controversy in two ways. First, this study suggests that alcohol does not directly increase women's unprotected sex intentions, rather increases them indirectly through effects on women's appraisal of the situation's relevance to her social goals. Thus the relationship between alcohol use and risky sex may not be direct, but instead may reflect underlying indirect processes. Second, this study suggests that even the direct, causal portion of alcohol's effect is complex, and is moderated by the personal characteristics one brings into a situation, as well as characteristics of that situation. These findings support a growing body of sexual risk taking research indicating that both personal and situational characteristics shape alcohol's effects on attention and resulting sexual decisions (Davis et al., 2007; Stoner et al., 2007). This study's explication of alcohol's complex influence on risky sex intentions allows researchers to build more sophisticated hypotheses to further understand alcohol's role in sexual risk behavior. For example, perhaps other short and long term goals that women possess, such as sexual safety and sexual pleasure, act interactively with intoxication to influence sexual decisions. Further, this work informs general alcohol myopia theory by integrating individual differences in relationship motivation with myopia effects on attention to explicate alcohol's effects on risk-taking behavior. Current conceptualizations of alcohol myopia theory largely focus on explaining how intoxicated individuals react to salient situational cues. This study increases the explanatory power of the theory by elucidating how background characteristics influence what situational cues will be salient when intoxicated. This opens as a future topic of alcohol myopia research the delineation of other relevant background factors and situational cues.

Study Limitations

The study's experimental design was complex, in order to reflect the multiply-determined, dynamic process of sexual risk taking. The story line was developed based on focus groups to depict a prototypic sexual risk taking context that is realistic to young women (Norris, 2005). Recent research on vignette methodology underscores the importance of developing and tailoring scenarios to specific populations (Noel, Maisto, Johnson, Jackson, Goings, & Hagman 2008). Nonetheless, no single study can comprehensively reflect all young women's sexual risk taking experiences, and the present study was circumscribed to one constellation of factors within one particular type of sexual encounter. Research is needed investigating the constructs of the Cognitive Mediation Model operationalized within different sexual risk taking contexts, such as established and renewed relationships. In addition researchers should use survey and interview methods to investigate the Cognitive Mediation Model via women's recollections of their cognitions and behaviors during real sexual encounters. Also, the present study focused on participants’ early appraisal of relationship potential in the scenario, which may not be a static cognition: This assessment may be continually updated during sexual encounters. Research assessing relationship potential at multiple scenario time-points to examine ongoing processes can clarify this process further.

One-third of our respondents identified as minority ethnicities, but we were not able to examine race or ethnic group differences explicitly. Given that relationship orientation and alcohol use are at least in part culturally governed, it is essential to replicate these findings with samples that include greater representation of Latinas and African Americans for whom HIV and other STIs have emerged as ethnic/racial health disparities (CDC, 2007).

Risky Sex Prevention Implications

Despite its limitations, our findings hold useful prevention implications. The combination of women's relationship motivation, partner familiarity, and intoxication exerted its effect directly on primary relationship appraisal, which was assessed early in the portrayed sexual encounter, before intense sexual contact began. Women can be taught how alcohol and their relationship goals can affect their relationship appraisals early in a social interaction with a man, which in turn can affect their cognitions during a sexual encounter, and ultimately lead to risky sexual decisions. These results are highly amenable to development of prevention skills training. Ordinary, nonsexual circumstances of primary relationship appraisals can be closely replicated in group role-playing exercises that can be conducted in settings such as health education classes or in the media where group role-plays of more intensely sexual situations such as condom negotiations may be difficult or inappropriate. Sexual safety skills trainings should also include more explicit treatments of the role of relationship motivations and intoxication in coloring one's assessment of relationship potential, and how this may influence one to make compromises about sexual safety to facilitate relationship building.

One type of condom negotiation strategy – relationship conceptualizing – was increased rather than decreased by secondary relationship appraisal in the model. This finding suggests that relationship motivated women may be more open to learning condom negotiation strategies that accurately reflect their relationship motivations and appraisals of relationship potential in the situation. Prevention programs can use this information to tailor condom negotiation training so that women view their condom negotiation and protected sex behavior as means of facilitating their own motives for sex, rather than as barriers to them. Among highly relationship motivated women, teaching relationship-oriented condom negotiation could be one way to decrease abdicating to a partner who wants to engage in unprotected sex.

In summary, the current findings advance existing risky sex research and theory by clearly identifying one causal chronology of how relationship factors and alcohol together can drive unsafe sex intentions for women. They identify how individual and situational factors interact to shape alcohol's influences on specific, unfolding, cognitive appraisals that lead to risky sexual decisions. Ultimately, this knowledge can be translated into empirically-based interventions designed to reduce sexual risk taking.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant AA014512 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism to the second author.

References

- Abbey A, Zawacki T, Buck PO. The effects of past sexual assault perpetration and alcohol consumption on men's reactions to women's mixed signals. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2005;24:129–155. doi: 10.1521/jscp.24.2.129.62273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, Zawacki T, McAuslan P. Alcohol and sexual perception. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61:688–697. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, Saenz C, Buck PO, Parkhill MR, Hayman LW., Jr. The effects of acute alcohol consumption, cognitive reserve, partner risk, and gender on sexual decision making. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:113–121. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afifi WA. Harming the ones we love: Relational attachment and perceived consequences as predictors of safe-sex behavior. Journal of Sex Research. 1999;36:198–206. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Prentice-Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Amaro H. Love, sex, and power: Considering women's realities in HIV prevention. American Psychologist. 1995;50:437–447. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.50.6.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter LA, Wilmot WW. Taboo topics in close relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1985;2:253–269. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan A, Schmeige SJ, Broaddus MR. Mediation analysis in HIV/AIDS research: Estimating multivariate path analytic models in structural equation modeling framework. AIDS and Behavior. 2007;11:365–383. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania JA, Kegeles SM, Coates TJ. Towards an understanding of risk behavior: An AIDS risk reduction model (ARRM). Health Education Quarterly. 1990;17:53–72. doi: 10.1177/109019819001700107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [December 28, 2007];HIV/AIDS among Women. 2007 from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/women/print/overview_partner.htm.

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3rd ed. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Alcohol use and risky sexual behavior among college students and youth: Evaluating the evidence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;14:101–117. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Does drinking promote risky sexual behavior? A complex answer to a simple question. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2006;15:19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Davis KC, Hendershot CS, George WH, Norris J, Heiman JR. Alcohol's effects on sexual decision making: An integration of alcohol myopia and individual differences. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:843–849. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JD, Fisher WA. Theoretical approaches to individual-level change in HIV risk behavior. In: Peterson JL, DiClemente RJ, editors. Handbook of HIV Prevention, AIDS Prevention and Mental Health. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; New York: 2000. pp. 3–55. [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K, D'Amico EJ, Katz EC. Intoxicated sexual risk taking: An expectancy or cognitive impairment explanation? Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60:54–63. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavey N, McPhillips K. Subject to romance: Heterosexual passivity as an obstacle to women initiating condom use. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1999;23:349–367. [Google Scholar]

- George WH, Marlatt GA. The effects of alcohol and anger on interest in violence, erotica, and deviance. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1986;95:150–158. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.95.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR, Zeichner A. The biphasic effects of alcohol on human physical aggression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:598–607. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.4.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillmore MR, Morrison DM, Leigh BC, Hoppe MJ, Gaylord J, Rainey DT. Does “high = high risk”? An event-based analysis of the relationship between substance use and unprotected anal sax among gay and bisexual men. AIDS and Behavior. 2002;6:361–370. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer JC, Fisher JD, Fitzgerald P, Fisher WA. When two heads aren't better than one: AIDS risk behavior in college-age couples. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1996;26:375–397. [Google Scholar]

- Hendershot CS, George WH. Alcohol and sexuality research in the AIDS era: Trends in publication activity, target populations and research design. AIDS and Behavior. 2007;11:217–226. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9130-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hines A, Snowden LR, Graves KL. Acculturation, alcohol consumption and AIDS-related risky sexual behavior among African American women. Women and Health. 1998;27:17–35. doi: 10.1300/J013v27n03_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Impett EA, Schooler D, Tolman DL. To be seen and not heard: Femininity ideology and adolescent girls’ sexual health. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2006;35:131–144. doi: 10.1007/s10508-005-9016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juran S. The 90's: Gender differences in AIDS-related sexual concerns and behaviours, condom use and subjective condom experience. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality. 1995;7:39–60. doi: 10.1300/J056v07n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS. Progress on a cognitive motivational relational theory of emotion. American Psychologist. 1991;46:819–834. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.46.8.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh BC. Alcohol and condom use: A meta-analysis of event-level studies. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2002;29:476–482. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200208000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald TK, Fong GT, Zanna MP, Martineau AM. Alcohol myopia and condom use: Can alcohol intoxication be associated with more prudent behavior? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:605–619. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.4.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald TK, Zanna MP, Fong GT. Why common sense goes out the window: Effects of alcohol on intentions to use condoms. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1996;22:763–775. [Google Scholar]

- Maisto SA, Carey MP, Carey KB, Gordon CM. The effects of alcohol and expectancies on risk perception and behavioral skills relevant to safer sex among heterosexual young adult women. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:476–485. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisto SA, Carey MP, Carey KB, Gordon CM, Schum JL. Effects of alcohol and expectancies on HIV-related risk perception and behavioral skills in heterosexual women. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2004a;12:288–297. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.12.4.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisto SA, Carey MP, Carey KB, Gordon CM, Schum JL, Lynch KG. The relationship between alcohol and individual differences variables on attitudes and behavioral skills relevant to sexual health among heterosexual young adult men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2004b;33:571–584. doi: 10.1023/B:ASEB.0000044741.09127.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison DM, Gillmore MR, Hoppe MJ, Gaylord J, Leigh BC, Rainey D. Adolescent drinking and sex: Findings from a daily diary study. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2003;35:162–168. doi: 10.1363/psrh.35.162.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus Users Guide. 4th ed. Muthen & Muthen; Los Angeles, CA: 1998-2007. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [December 28, 2007];National Advisory Council on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism - Recommended Council Guidelines on Ethyl Alcohol Administration in Human Experimentation. 2005 from http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/Resources/ResearchResources/job22.htm.

- Noar SM, Morokoff PJ, Harlow LL. Condom negotiation in heterosexually active men and women: Development and validation of a condom influence strategy questionnaire. Psychology and Health. 2002;17:711–735. [Google Scholar]

- Noel NE, Maisto SA, Johnson JD, Jackson LA, Goings CD, Hagman BT. Development and validation of videotaped scenarios: A method for targeting specific participant groups. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23:419–436. doi: 10.1177/0886260507312941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris J, Kerr KL. Alcohol and violent pornography: Responses to permissive and nonpermissive cues. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement. 1993;11:118–127. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1993.s11.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris J, Masters NT, Zawacki T. The cognitive mediation of women's sexual decision making: A theoretical framework. Annual Review of Sex Research. 2004;15:258–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins JM, Krueger JI. Social projection to ingroups and outgroups: A review and meta-analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2005;9:32–47. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0901_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstock IM. The health belief model and preventive health behavior. Health Education Monographs. 1974;2:354–386. [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson CA, Cantor N. Social dating goals in late adolescence: Implications for safer sexual activity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;68:1121–1134. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.68.6.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santelli JS, Brener ND, Lowry R, Bhatt A, Zabin LS. Multiple sexual partners among U.S. adolescents and young adults. Family Planning Perspectives. 1998;30:271–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayette MA, Breslin FC, Wilson GT, Rosenblum GD. An evaluation of the balanced placebo design in alcohol administration research. Addictive Behaviors. 1994;19:333–342. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(94)90034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeran P, Abraham C, Orbell S. Psychosocial correlates of heterosexual condom use: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1999;125:90–132. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LA. Partner influence on noncondom use: Gender and ethnic differences. The Journal of Sex Research. 2003;40:346–350. doi: 10.1080/00224490209552200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder M, Stukas AA., Jr. Interpersonal processes: The interplay of cognitive, motivational, and behavioral activities in social interaction. Annual Review of Psychology. 1999;50:273–303. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starzyk KB, Holden RR, Fabrigar LR, MacDonald TK. The personal acquaintance measure: A tool for appraising one's acquaintance with any person. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;90:833–847. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Josephs RA. Alcohol myopia: Its prized and dangerous effects. American Psychologist. 1990;45(8):921–933. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.8.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoner SA, George WH, Peters LM, Norris J. Liquid courage: Alcohol fosters risky sexual decision making in individuals with sexual fears. AIDS and Behavior. 2007;11:227–237. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9137-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann WB, Silvera DH, Proske CU. On knowing your partner: Dangerous illusions in the age of AIDS. Personal Relationships. 1995;2:173–186. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SP, Leonard KE. Alcohol and human physical aggression. In: Green RG, Donnerstein EI, editors. Aggression: Theoretical and Empirical Reviews. Vol. 2. Harper Collins; New York: 1983. pp. 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Umphrey L, Sherblom J. Relational commitment and threats to relationship maintenance goals: Influences on condom use. Journal of American College Health. 2007;56:61–67. doi: 10.3200/JACH.56.1.61-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams SS, Kimble DL, Covell NH, Weiss LH, Newton KJ, Fisher JD, et al. College students use implicit personality theory instead of safer sex. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1992;22:921–933. [Google Scholar]

- Wingood GM, Hunter-Gamble D, DiClemente RJ. A pilot study of sexual communication and negotiation among young African American women: Implications for HIV prevention. The Journal of Black Psychology. 1993;19:190–203. [Google Scholar]