SUMMARY

The coronary vessels and epicardium arise from an extracardiac rudiment called the proepicardium. Failed fusion of the proepicardium to the heart results in severe coronary and heart defects. However, it is unknown how the proepicardium protrudes toward and attaches to the looping heart tube. Here we show that ectopic expression of BMP ligands in the embryonic myocardium can cause proepicardial cells to target aberrant regions of the heart. Additionally, misexpression of a BMP antagonist, Noggin, suppresses proepicardium protrusion and contact with the heart. Finally, proepicardium explant preferentially expands toward a co-cultured heart segment. This preference can be mimicked by BMP2/4 and suppressed by Noggin. These results support a model in which myocardium-derived BMP signals regulate the entry of coronary progenitors to the specific site of the heart by directing their morphogenetic movement.

INTRODUCTION

Integration of multiple cell populations is essential for organogenesis. The amniote four chambered heart forms from cells derived from multiple, distinct embryonic origins. The primary myocardium and endocardium, which form the beating heart tube, receive additional cells from the anterior and posterior heart fields, cardiac neural crest and proepicardium (Abu-Issa et al., 2004; Ishii et al., 2009a; Snarr et al., 2008). The signals that underlie the fusion of these populations are poorly described.

In this study we examine the fusion of the proepicardium (PE) to the heart. This is a key step to initiate coronary vessel formation but is one of the least understood processes in cardiac development. The PE forms adjacent to the sinoatrium, but despite being physically close to this region, it does not attach to the sinoatrium. Instead the PE extends mesothelial villi and attaches to the atrioventricular (AV) junction on the inner curvature (IC) of the heart, which we abbreviate AV/IC, via a tissue bridge that extends across the pericardial cavity (Manner, 1992; Nahirney et al., 2003). Several studies have searched for regulators of this process (Hatcher et al., 2004; Kwee et al., 1995; Mellgren et al., 2008; Moore et al., 1999; Pennisi and Mikawa, 2009; Sengbusch et al., 2002), but none explain how the PE protrudes and attaches specifically to the AV/IC.

Once the PE attaches to the heart myocardium it forms the epithelial covering of the heart called the epicardium. A subpopulation of PE cells undergoes epithelial to mesenchymal transformation to penetrate the wall of the heart (Dettman et al., 1998; Ratajska et al., 2008; Viragh and Challice, 1981; Viragh et al., 1993). This population gives rise to endothelial cells, fibroblast cells and smooth muscle cells that form the coronary vessels, which connect to the aorta and provide blood circulation to the metabolically active beating myocardium (Dettman et al., 1998; Gittenberger-de Groot et al., 1998; Manner, 1999;Mikawa et al., 1992; Mikawa and Gourdie, 1996; Perez-Pomares et al., 2002; Zhou et al., 2008). Interventions that ablate the PE or prevent it from reaching the heart result in failure to form coronary vessels and epicardium, and cause severe cardiovascular abnormalities (Eralp et al., 2005; Gittenberger-de Groot et al., 2000, 2004; Kwee et al., 1995;Manner, 1993; Mellgren et al., 2008; Moore et al., 1999; Yang et al., 1995). The potential of epicardial cells to generate myocardial cell types and serve as a stem cell population during cardiac injury has been suggested, making the PE an important source of stem cells for cardiovascular therapeutics (Cai et al., 2008; Chien et al., 2008; Kruithof et al., 2006; Schlueter et al., 2006; Wessels and Perez-Pomares, 2004; Zhou et al., 2008).

We report here the identification of BMP as a key molecular component of PE protrusion. Our in vitro and in vivo data demonstrate that BMP is necessary and sufficient for directed PE protrusion and site-specific attachment to the myocardium. These results suggest a role for BMP signaling during a key morphogenetic event in coronary development.

RESULTS

Physical Association of the Proepicardium and Heart During Embryonic Development

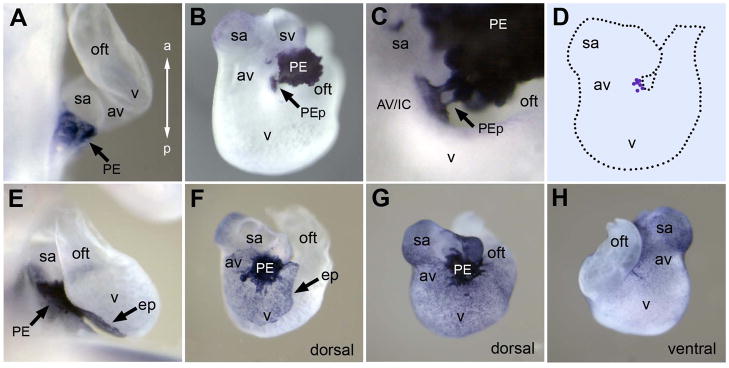

To explore underlying mechanisms of the fusion of the PE to the heart we examined avian embryos between stage 14 and 23 (embryonic day 2 to 4) when the PE protrudes, attaches and spreads over the heart (Hamburger and Hamilton, 1992). The PE and epicardium were visualized by whole-mount in situ hybridization (ISH) for Tbx18, a PE marker (Cai et al., 2008; Haenig and Kispert, 2004; Ishii et al., 2007; Schlueter et al., 2006; Schulte et al., 2007). Our data show that the PE develops adjacent to the sinoatrium (Fig 1A), but importantly does not protrude or attach to the heart at this physically closest region. Instead the PE extends villus- or finger-like protrusions that attach to the atrioventricular junction on the inner curvature (AV/IC) of the looping heart by early stage 18 (Fig 1B–1D). This preference in PE protrusion and attachment to a specific site of the heart was conserved in all 75 embryos examined. After contact with the heart, the PE cells spread over the surface of the heart, covering the dorsal surface during embryonic day 3 (stage 18–22; Fig 1F), and completely covering the dorsal and ventral surfaces by day 4 (stage 23–24; Fig 1G and 1H). Consistent with previous morphological descriptions (Manner, 1992; Nahirney et al., 2003), our molecular visualization in whole-mount demonstrated that PE protrusion precisely targets the AV/IC for attachment to the heart. In the present study we examined a potential role of paracrine signals that regulate PE morphogenesis and site-specific attachment to the heart.

Figure 1. Proepicardial Attachment and Epicardial Spreading on the Avian Heart.

(A–C,EH) Whole-mount ISH for PE and epicardial marker Tbx18. (A) Magnified lateral view of the heart at stage 14 showing PE location posterior to the heart, adjacent to the sinoatrium. (B) Dorsal view of an isolated stage 18 (early) heart showing the PE mass during attachment. Note weaker myocardial Tbx18 staining in the sinoatrium and sinus venosus that is easily discerned from the darker stained PE and epicardium. (C) Magnified view of (B) showing protrusions from the PE attached to the inner curvature of the atrioventricular junction. (D) Cartoon outline of the dorsal urface of stage 18 heart with blue dots indicating the centers of PE masses in 7 different embryos. (E–F) Stage 19 heart after PE attachment and epicardial spreading. Lateral view (E) and dorsal view (F) showing PE mass attached over the AV/IC region and epicardium spreading on the dorsal side of the heart. (G–H) Stage 23 heart with complete covering of epicardium viewed from the dorsal side (G) and ventral side (H). a, anterior; av, atrioventricular junction; AV/IC, atrioventricular junction/inner curvature; ep, epicardium; oft, outflow tract; p, posterior; PE, proepicardium; PEp, proepicardial protrusion; sa, sinoatrium; sv, sinus venosus; v, ventricle.

Candidate Paracrine Factors That Influence PE Expansion

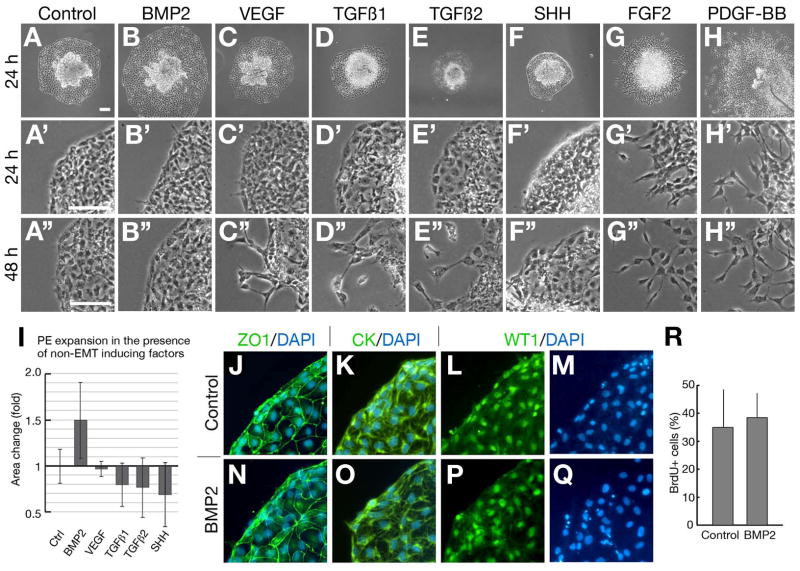

To examine potential paracrine factors that signal oriented protrusion of the PE to the heart, we undertook a survey of candidate myocardial-expressed factors. Factors we tested were chosen based on the following criteria: (i) capability to influence PE/epicardial behavior, (ii) implication in coronary vessel development, and (iii) enrichment in the AV/IC region of the heart. Myocardial expressed factors that satisfied multiple criteria include BMP2, VEGF, TGFβ1, TGFβ2, SHH, FGF2 and PDGF-BB (Danesh et al., 2009;Guadix et al., 2006;Kruithof et al., 2006;Mellgren et al., 2008;Morabito et al., 2001;Nesbitt et al., 2009;Olivey et al., 2006;Pennisi and Mikawa, 2009; Rutenberg et al., 2006;Schlueter et al., 2006;Somi et al., 2004a;Tomanek et al., 2002; Tomanek et al., 2006). Additionally, we examined several epicardial-derived mitogens (Erythropoietin, FGF9 and WNT9b) (Lavine et al., 2005;Merki et al., 2005;White et al., 2007)(Fig. S1). Since protrusion of PE villi and extension of a tissue bridge (Manner, 1992; Nahirney et al., 2003) must involve expansion of the external mesothelial epithelium, we examined whether any of these factors promote epithelial expansion of the PE in culture. Our culture system models three dimensional protrusion in two dimensions using a substrate, whereby the epithelial nature of the PE is maintained, while the vesicular nature of in vivo PE protrusion is lost. Of the 7 myocardial-expressed factors we examined only BMP2 increased the radial expansion of the PE as an epithelial sheet (Fig 2B) compared to control PE (Fig 2A). PEs treated with FGF2 and PDGF-BB underwent mesenchymal transformation (Fig 2F, 2G), which is not associated with PE protrusion in vivo, and were excluded from further analysis. Quantification of PE expansion after 24 hr shows that BMP2-treated explants spread ~50% farther than control explants, whereas other factors did not increase expansion (Fig 2I). Furthermore, no overt mesenchymal transformation was detected in control and BMP2- treated PE explants even after 48 hr of culture (Fig 2B″), whereas those treated with VEGF, TGFβ1 and TGFβ2, but not SHH, generated mesenchymal cells at the periphery (Fig 2C″–2H″). Thus, BMP2 has a distinct action on PE cells to promote their expansion without causing detectable mesenchymal transformation.

Figure 2. BMP2 Promotes in vitro PE Expansion without Mesenchymal Transformation.

PE explants cultured for 24 hr (A–H) and magnified view of the leading edge of spreading PE after 24 hr (A′–H′) and 48 hr (A″–H″) culture on a plastic dish in the presence of BSA only (A–A″), BMP2 (B–B″), VEGF (C–C″), TGFs1 (D–D″), TGFs2 (E–E″), SHH (F–F″), FGF2 (G–G″) and PDGF–BB (H–H″). (I) Quantification of PE expansion at 24 hr. BMP2 promoted expansion was significant by t-test (p=0.03). Antibody markers of tight junctions (ZO1) (J,N), epithelia (Cytokeratin) (K,O), and PE identity (Wt1) (L,P) show no difference between control (J–M) and BMP2-treated (N–Q) PEs. (R) Graph showing BrdU incorporation in control and BMP2-treated PE to measure cell proliferation. Bars: 100μm. A–H and A′–H″ are the same magnification. Error bars represent S.D.

BMP2 Signals PE Expansion Independent of Cell Proliferation Increases

To further address if BMP2-induced expansion occurred as a result of epithelial spreading, we examined localization of ZO1 (tight junction marker) and cytokeratin (epithelial marker) in the leading edge of PE expansion in BMP2 treatments (Fig 2J, 2K and 2N, 2O) (Olivey et al., 2006; Vrancken Peeters et al., 1995). There was no detectable difference in localization of these markers showing that PE explants spread as epithelia in response to BMP2. Additionally, Wilms’ tumor 1 (Wt1) antibody showed that expanding cells of PE explants were entirely of proepicardial origin (Fig 2L, 2M and 2P, 2Q) (Moore et al., 1999). Lastly, BrdU incorporation to measure cell proliferation did not increase significantly in BMP2-treated PE explants. These data show that BMP2 signals PE expansion as an epithelia by altering cell behavior without increasing cell proliferation.

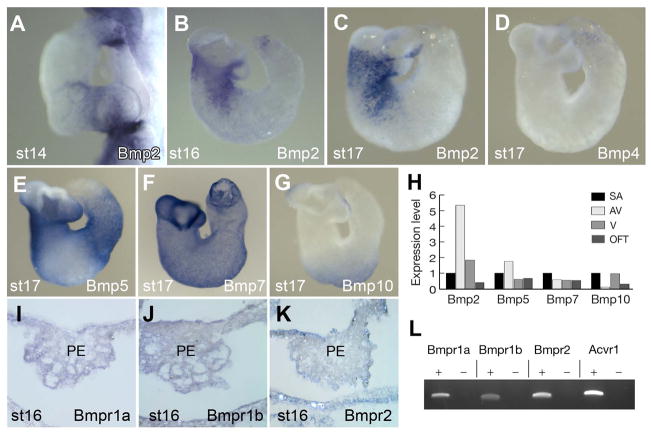

Expression Patterns of BMP Ligands in the AV/IC Myocardium

If BMP ligands play a role in directing PE protrusion toward the AV/IC, they must be expressed in this specific region of the heart. To test this possibility we examined BMP ligand expression in the heart. Of the five BMP family members expressed in the avian heart at stages of active PE protrusion (Somi et al., 2004a; Somi et al., 2004b; Teichmann and Kessel, 2004), we detected Bmp2, Bmp5 and Bmp7 in the AV/IC region (Fig 3A–C, 3E, and 3F) with Bmp2 being highly enriched in this region and absent from the sinoatrium. Bmp2 is expressed in the heart as the PE forms (Figure 3A) and is localized to the AV region prior to attachment (Fig 3B and 3C). Bmp5 showed preferential expression in the AV junction, but expression was also detected in the sinoatrium, ventricle and outflow tract at lower levels (Fig 3E). Bmp7 was detected broadly in the heart throughout the myocardial wall (Fig 3F). In our hands, Bmp4 was not detected in the heart at this stage (Fig 3D). Bmp10 was detected weakly in the sinoatrium and ventricle (Fig 3G). Using real time PCR analysis we examined the levels of Bmp transcripts in the AV junction compared to the sinoatrium, ventricle and outflow tract (Fig 3H). The data show that the AV junction expresses over five times more Bmp2 transcripts than the sinoatrium. Real time PCR data supported the ISH expression analysis that Bmp5, Bmp7 and Bmp10 were not substantially enriched in the AV junction compared to the sinoatrium. In addition to high BMP ligand expression in the AV junction, expression of type-1 and type-2 BMP receptors was detected in the PE by whole-mount ISH analysis and endpoint PCR (Fig 3I–L). The data are consistent with the model in which myocardium-derived BMP signal orients PE protrusion toward the AV/IC.

Figure 3. Expression of BMP Ligands in the Heart During PE Protrusion and Attachment.

(A–G) Whole-mount ISH for Bmp2 (A–C), Bmp4 (D), Bmp5 (E), Bmp7 (F) and Bmp10 (G). (H) Real time PCR analysis of BMP ligands expressed within heart regions (stage 17). Expression levels are relative to detection in the SA. (I–K) Section of PE showing expression of Bmpr1a (I), Bmpr1b (J), and Bmpr2 (K). (L) Expression of BMP receptors in the PE detected by PCR. The reverse transcription reaction was carried out with (+) or without (−) reverse transcriptase. av, atrioventricular junction; oft, outflow tract; PE, proepicardium; PEp, proepicardial protrusion; sa, sinoatrium; v, ventricle.

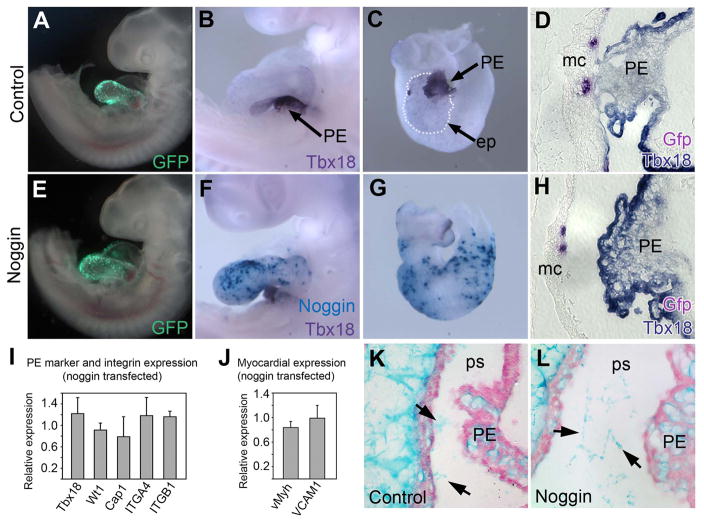

BMP Antagonist Noggin Can Block PE Protrusion and Attachment to the Heart in vivo

If BMP signal plays a role in oriented PE protrusion, a BMP antagonist would block or diminish this process. Noggin is a well-established BMP antagonist which binds BMP2 and BMP4, and to a lesser degree BMP7, to antagonize ligand and receptor interactions (Zimmerman et al., 1996). Chick Noggin and enhanced green fluorescent protein (Gfp) were co-expressed (or Gfp alone as control) in the myocardium at stage 13–14 prior to initiation of oriented PE protrusion. The resulting embryos displayed substantial transfection in the myocardium but not other tissues, including the epicardium (Fig 4A, 4E and S2). Real time PCR analysis detected between 170 and 270 times more Noggin in a transfected heart compared to a control heart (not shown) consistent with ISH data (Fig 4B, 4C, 4F and 4G). Whole-mount ISH for Tbx18 revealed that, while all control embryos showed normal PE attachment (n=51; Fig 4B–D), 30% of Noggin-transfected embryos had failed PE attachment to the heart (n=10; Fig 4F–H). The remaining PEs in Noggin-transfected embryos attached to the AV/IC region of the heart, but exhibited less prominent epicardial development than control hearts (Fig S3A–S3G), perhaps due to delayed PE attachment to the heart. In two other separate experiments Noggin transfection resulted in 38% and 18% fewer PE attachments (n=16 and n=15, respectively). Taken together the data show that ectopic Noggin expression in the heart myocardium is capable of diminishing PE protrusion and attachment to the heart.

Figure 4. Misexpression of Noggin in the Myocardium Disrupts PE Attachment.

(A–H) Stage 17 embryos following transfection with Gfp only (control; A–D) or Gfp and Noggin (E–H) by pericardial injection of Lipofectamine solution. (A,E) Visualization of transfection by fluorescence microscopy. (B,C,F,G) Whole-mount double ISH for Tbx18 (purple) and Noggin (light blue). (B,C) Control embryo shows normal PE attachment and epicardial spreading (dotted line). (F,G) Noggin-transfected heart shows failed PE attachment to heart. (D,H) Sections of control (D) and Noggin-transfected (H) hearts stained by double ISH for Tbx18 (purple) and Gfp (magenta). (I,J) Real time PCR analysis of Noggin-transfected samples (2 cDNA pools, 4 samples each) relative to controls (control level equals 1). (I) PE marker genes (Tbx18, Wt1, Cap1) and integrins (ITGA4, ITGB1). (J) Myocardial expression of VCAM1 (with vMyh as comparison). (K,L) Alcian blue/nuclear fast red stained sections of stage 16 control (K) (n=12) and Noggin-transfected (L) (n=11) hearts showing intact pericardial ECM bridges (arrows) between the PE and heart. ep, epicardium; mc, myocardium; PE, proepicardium; ps, pericardial space. Error bars represent S.D.

Suppression of PE protrusion and attachment in Noggin-transfected hearts can possibly be explained by alterations in PE cell identity, decreases in cell adhesion factors or loss of ECM bridges (Kruithof et al., 2006; Kwee et al., 1995; Nahirney et al., 2003; Schlueter et al., 2006; van Wijk et al., 2009; Yang et al., 1995). To test the possibility that PE cell identify was altered we quantified the level of Tbx18 and two other well established PE marker genes Wt1 and Capsulin (Cap1, also called Tcf21) (Lu et al., 1998; Moore et al., 1999), by real time PCR in control and Noggin-transfected embryos (Fig 4I). In our hands no notable changes in the expression of any PE markers were detectable in two separate pools of PE cDNA (n=4). We similarly were unable to detect changes in PE expression of essential integrins (ITGA4 and ITGB1) (Fig 4I) or VCAM1 in Noggin-transfected myocardium (Fig 4J). Lastly, Noggin transfection had no apparent effect on pericardial matrix bridges detected by Alcian blue staining (Fig 4K and 4L). Furthermore, no noggin-induced changes in compact myocardial thickness, PE matrix production, myocardial conversion, changes in cell proliferation or apoptosis were observed (Fig S3). These data suggest that noggin-induced suppression of PE attachment is not easily explained by known autonomous mechanisms.

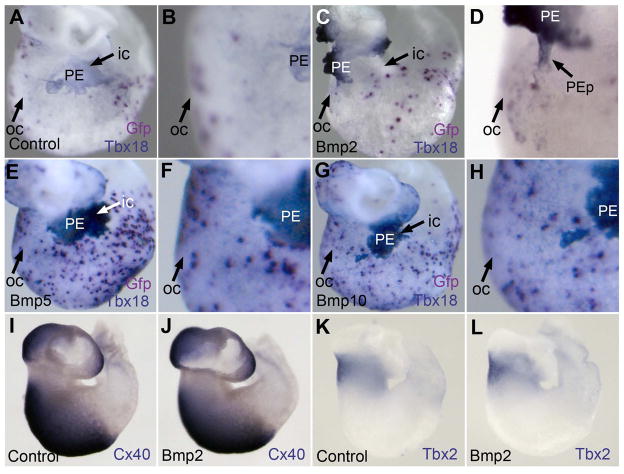

BMP2 Misexpression Creates Ectopic PE Attachment Sites on the Myocardium

The above inhibitory effect of Noggin on PE protrusion and attachment in vivo suggests that BMP signaling is necessary for these morphogenetic processes. To test if localized BMP is required for directed PE protrusion and attachment to the AV/IC we misexpressed BMP ligands broadly over the myocardial surface to override the endogenous signal. Bmp2, Bmp4, Bmp5 or Bmp10 was misexpressed in the myocardium and PE attachment sites were mapped in the resulting embryos. Control embryos misexpressing only Gfp displayed normal PE protrusion and specific attachment to the AV/IC (Fig 5A and 5B; n=51). When the PE properly attached to the AV/IC, this region was physically obscured from view by the attached PE mass (Fig 5A). In striking contrast, in Bmp2-transfected hearts 38% of PE attachments were outside of the AV/IC region (n=26). Of these Bmp2-misexpressing embryos, the PE protrusions often attached to ectopic sites, such as the ventricle posterior and distal to the AV/IC region. For example, the Bmp2-transfected embryo shown in Figures 5C and 5D exhibited a PE protrusion attached to the outer curvature rather than the inner curvature. In this Bmp2-transfected heart the inner curvature of the heart was exposed and could be clearly seen (compare Fig 5A and 5C) since the PE attached away from this region. Real time PCR analysis shows five to ten times the level of Bmp2 transcripts (n=8; 7.3+/−2.3) in Bmp2-transfected hearts compared to control hearts.

Figure 5. Altered PE Attachment Site in Bmp2 Misexpressing Heart.

(A–H) Double ISH for Tbx18 (blue/purple) and/or Gfp (magenta) demonstrating sites of PE attachment to the heart. B, D, F and H are magnified views of A, C, E and G, respectively. (A,B) Dorsal view of control heart transfected only with Gfp (C,D) Bmp2-transfected heart showing attachment of PE protrusion near the outer curvature at a site of transfection. (E,F) Bmp5-transfected heart. (G,H) Bmp10-transfected heart. Blue dots of Tbx18 expression over the myocardium are from the spreading epicardium. (I–L) Whole-mount ISH for regional heart markers Cx40 (I,J) and Tbx2 (K,L) in Gfp controls (I,K) and Bmp2-transfected hearts (J,L). ic, inner curvature; oc, outer curvature; PE, proepicardium; PEp, proepicardial protrusion.

In Bmp5- (n=22; Fig 5E and 5F) and Bmp10- (n=8; Fig 5G and 5H) transfected hearts the PE mass was located over the AV/IC region in all embryos as observed in controls. Misexpression of Bmp4, which is closely related to Bmp2 sharing 96% protein sequence similarity in the mature peptide, resulted in hearts with exposed AV/IC regions in 28% of embryos (n=18; Fig S4B and S4C), indicating a mislocation of PE attachment. This set of data shows that Bmp2 misexpression, and to a lesser degree Bmp4, is sufficient to create an ectopic PE attachment site on the myocardium.

The aberrant locations of PE attachment in Bmp2-misexpressing hearts could be explained by misshaped hearts due to altered patterning of the heart (Yamada et al., 2000). However, morphological inspection of Bmp2- and Bmp4-misexpressing hearts in whole-mount revealed no overt effect in heart positioning or looping (n=17; Figures S4D–S4I). To further investigate the possibility that Bmp2 misexpression altered heart patterning, we analyzed expression of region specific genes Tbx2 and Connexin 40 (Cx40) in transfected hearts. Tbx2 is a marker of the AV junction myocardium and Cx40 is expressed in fast conducting myocytes and the sinoatrium and ventricle but not the AV junction (Minkoff et al., 1993; Yamada et al., 2000). Whole-mount ISH revealed no detectable misregulation of Tbx2 or Cx40 in Bmp2-misexpressing hearts (Fig 5I–5L). Similarly no misregulation in Tbx2 or Cx40 was evident in hearts misexpressing Bmp4 (Fig S4J–Q), which also showed ectopic sites of PE attachment. Lastly, Bmp2 transfection did not alter pericardial ECM bridges detected by Alcian blue staining (Fig S4S and S4T). These data suggest that changes in heart morphology or patterning do not play a major role in BMP-induced mislocation of PE attachment to the heart. Thus, BMP2 and BMP4 appear to be sufficient to attract PE cells to an ectopic site of the myocardium.

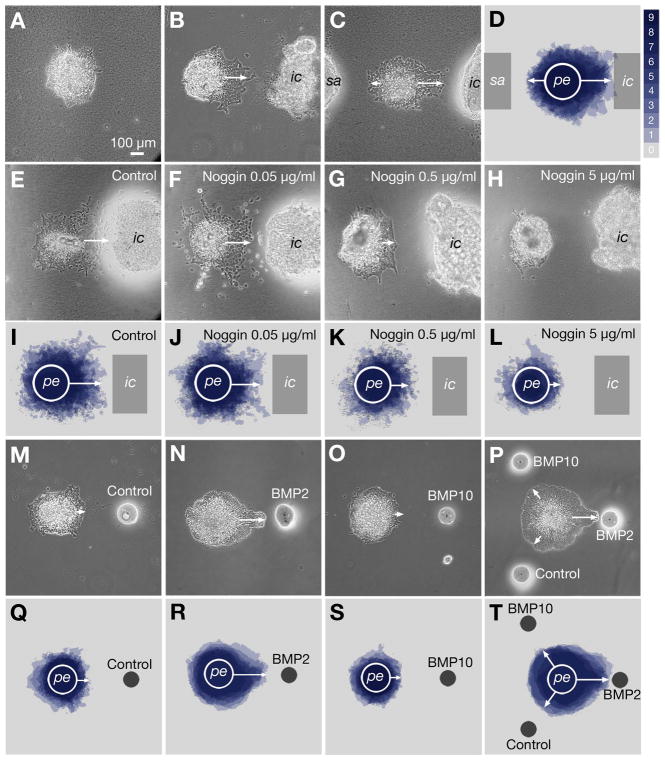

Myocardial Explants and BMP-Soaked Beads Can Direct PE Protrusion

While the above data show that oriented PE protrusion and attachment to the heart in vivo is regulated by BMP signaling, it is unclear whether BMP signals from the myocardium act directly on the PE. To test this possibility we co-cultured PEs and heart segments. A PE cultured alone on collagen gel showed no significant orientation in epithelial expansion (Fig 6A). However, when an AV/IC segment was co-cultured, the PE expanded toward the heart explant (Fig 6B). Time-lapse movies of the co-culture show that PE cells maintained an epithelial-like organization as they underwent directional migration (see Supplemental movie). The data show that the PE can directly respond to a co-cultured heart fragment and undergo directed protrusion toward it.

Figure 6. BMP-Dependent Directional PE Expansion to the Heart Explant in vitro.

(A–D) PE explants co-cultured with sinoatrium and/or AV/IC explants on collagen gels. (A) PE demonstrates a weak activity to expand in all directions, if cultured alone. (B,C) PE preferentially expands toward a co-cultured AV/IC explant. (D) Peripheries of 9 explants complied into an overlay. (E–L) Noggin peptide blocks directional PE expansion dose-dependently. (M–T) PE responds and preferentially expands to a source of BMP2. PE was co-cultured with a bead soaked with BSA only (control; M,Q), BMP2 (N,R), BMP10 (O,S) or all three beads for comparison (P,T). ic, AV/IC explant; pe, proepicardium; sa, sinoatrial explant. Bar: 100μm.

Importantly, the PE preferentially expanded toward the AV/IC rather than the SA (Fig 6C and 6D). The data is consistent with our in vivo observation that the PE protrudes to the AV/IC region of the heart (Fig 1B–1D). To test if BMP signaling is involved in this preference, Noggin peptide was added to the culture. Addition of Noggin inhibited oriented PE expansion to the AV/IC explant dose dependently (Fig 6E–L). These results show that oriented PE protrusion to the AV/IC explant is Noggin sensitive, suggesting involvement of BMP signaling.

To test if BMP acts directly on the PE to orient its protrusion, a BMP2-soaked bead was co-cultured with a PE explant. No significant PE expansion was detected with a control bead (Fig 6M and 6Q). In contrast, the PE expanded toward a BMP2-soaked bead (Fig 6N and 6R). Similar oriented expansion was seen with BMP4 (Figures S5A and S5D). However, BMP6 (Fig S5B and S5E), BMP7 (Fig S5C and S5F), nor BMP10 (Fig 6O and 6S) showed significant effects. When co-cultured with three beads, BMP2, BMP10 and control, the PE preferentially protruded toward the BMP2 bead (Fig 6P and 6T). Taken together, the data show that the PE expands toward the AV/IC segment that expresses the highest level of BMP2 and this effect can be mimicked by BMP2 alone.

DISCUSSION

Here we describe a paracrine interaction between two separate organ rudiments, the PE and heart tube, which directs their contact and eventual fusion. The present study has identified BMP signaling as a regulator of this process. Our data support a model in which paracrine factors from the AV/IC attract PE cells to target a specific entry site on the heart.

Previous loss-of-function studies have identified several genes necessary for proper recruitment of PE cells to the heart. These include transcription factors and cell adhesion molecules that primarily regulate cell autonomous events or direct cell-cell interactions (Dettman et al., 2003; Hatcher et al., 2004; Kwee et al., 1995; Moore et al., 1999; Yang et al., 1995). These studies, however, did not identify a mechanism for targeting of the PE to a specific site on the heart since none of these factors are localized to the target myocardium. The present in vivo and in vitro studies show that the AV/IC myocardium directs PE protrusion and that BMP signaling mediates this role of the myocardium. Consistent with this idea, Bmp2 is highly expressed in the AV/IC myocardium, and PE cells express BMP receptors. Furthermore, only BMP2 and closely related BMP4, but not other BMP members expressed more broadly in the heart, showed an activity to direct PE protrusion. Although we cannot completely rule out autocrine functions for BMPs in the PE, requirement of a localized Bmp2 source to the AV/IC myocardium, as demonstrated by in vivo myocardial misexpression of Bmp2 and its antagonist Noggin, and capability of BMP2 to act directly on PE cells to orient their morphogenetic movement, favors a role for myocardium-derived BMP as a paracrine cue that attracts PE cells to the heart.

Our loss of function data do not distinguish between permissive vs instructive roles for BMP signals. However, our gain of function in vivo misexpression data clearly show that ectopic BMP2 in the myocardium indeed reorients the direction of PE extension resulting in ectopic entry sites to the heart in vivo. Similarly, PE explants extend toward BMP2 alone in vitro. The data are consistent with an instructive role for BMP signaling in PE extension, although the data do not exclude a permissive role for BMP signaling in PE cell activity. Our proposed role for BMP2 to orient PE extension also implies signaling across the pericardial space. However, it is currently unclear how myocardium-derived BMP ligands signal PE cells as the heart continues beating. We have previously reported that the pericardial space contains an ECM scaffold between the myocardium and PE and that the pericardial ECM is necessary for PE extension and attachment (Nahirney et al., 2003). While BMP factors have a high affinity with heparin sulfate proteoglycans found in the pericardial ECM, we have to await further studies to determine if the pericardial ECM plays any role in BMP signaling between the PE and myocardium (Ruppert et al., 1996; Sampath et al., 1987; Wang et al., 1988).

The modified transfection method with Lipofectamine used in this study allowed us to restrict gene transduction both in time and space. In ovo pericardial injection of unmodified Lipofectamine reagent achieved substantial transfection efficiency in the myocardium. Further characterization of our method using in vitro hanging drop culture showed that Lipofectamine preferentially transfects myocardium over surface ectoderm and neural tube, which is a significant difference from pegylated Lipofectamine-based transfection (Decastro et al., 2006) (see Figures S2J–S2M). The precision of gene transfection allowed us to analyze the effect of myocardium-derived BMPs on PE development without defects in cardiac patterning that would be caused by altered BMP activities at earlier stages (Schultheiss et al., 1997; van Wijk et al., 2007).

The proepicardial progenitors are recognizable in divergent species, from fish through humans, because they share morphology, gene expression and developmental function (Jahr et al., 2008; Pombal et al., 2008; Ratajska et al., 2008; Reese et al., 2002; Rodgers et al., 2008; Serluca, 2008). Similarly, common mechanisms that guide PE/myocardial interaction also likely exist. In chick, we show that the AV and inner curvature region is the site of attachment and expresses Bmp2 to guide initial PE/myocardial contact. Chick shares features of PE attachment with many vertebrates including shark, frog, rat and human (Hirakow, 1992; Jahr et al., 2008; Manner, 1993; Nesbitt et al., 2006; Pombal et al., 2008). In particular, the proepicardium in all of these species forms stable tissue bridges that bind to the heart near the atrioventricular junction, typically the site of Bmp2 and/or Bmp4 expression (Danesh et al., 2009; Jiao et al., 2003; Lee and Saint-Jeannet, 2009). Thus, it is possible that myocardial BMP2/4 serves as an evolutionarily conserved mechanism of PE recruitment. This possibility, however, is put into question as mouse PE recruitment does not utilize stable tissue bridges, and PE attachment, which occurs over a broad region of the heart, appears to be non-selective. This broad PE binding has led to speculation that mouse coronary recruitment can occur by non-specific contact and subsequent adhesion (Rodgers et al., 2008). Although mechanisms of mouse PE recruitment remain theoretical, the close proximity of the PE and heart in mouse may negate the need for signaling across the pericardial space. A strictly contact-driven model of PE adhesion can explain PE binding, but does not explain why the PE initially protrudes toward myocardium of the AV region rather than migrating along the sinoatrial myocardium, which expresses necessary PE adhesion molecules (Kwee et al., 1995; Rodgers et al., 2008). Further comparative study is required to understand major mechanisms of PE binding.

This study identified a signaling interaction between two distinct heart rudiments, the PE and myocardium. Although interactions between closely associated tissues have been studied extensively (Capdevila and Izpisua Belmonte, 2001; Chow and Lang, 2001; Streit and Stern, 1999; Yasugi and Mizuno, 2008), much less is known about interactions across the body cavity. The PE-myocardium fusion provides a useful model system to study signaling involved in longrange tissue interactions. Further study of cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying integration of PE cells to the heart would significantly advance our understanding of the exact roles of PE cells in normal heart development and provide a basis for future therapeutic approaches for targeting coronary vessel precursors to the heart. Understanding the mechanism of PE derived cell integration is particularly important because it has been suggested that PE derived cells can generate various cardiac cell types and serve as a stem cell population during cardiac injury (Cai et al., 2008; Chien et al., 2008; Kruithof et al., 2006; Schlueter et al., 2006; Wessels and Perez-Pomares, 2004; Zhou et al., 2008).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

PE culture

Chick (Gallus gallus domesticus) embryos were incubated at 38°C in a humidified incubator and staged according to Hamburger and Hamilton (1992). Stage 17 embryos were placed ventralside up and “grape-like” clusters of cells described previously (Manner et al., 1992; Nahirney et al., 2001) were isolated from the coelomic wall with pulled glass capillary needles (World Precision Instruments) or No. 5 forceps (Dumont). Isolated cell clusters were cultured in serumfree M199 on uncoated plastic petridishes (Becton Dickinson, #351008) or drained collagen gel. The former was used to examine PE expansion in response to paracrine factors including recombinant BMP2, TGFβ1, TGFβ2, SHH, FGF2, PDGF-BB, EPO, WNT9B, FGF9 (R&D systems) and VEGF-164 (Sigma). Each factor was added to a final concentration of 10ng/ml. Bovine serum albumin (BSA) was used as a control. PE expansion was quantified digitally using Photoshop as described elsewhere (Reese et al., 2002; Wei and Mikawa, 2000) or manually by weighing printed images of explants. To examine mitotic activity bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU; Sigma) was added at 50 μM one hour prior to the fixation. Culture on drained collagen gel was used to test directional PE expansion in response to a co-cultured heart segment or BMPsoaked bead. Drained collagen gels were prepared with 150 μl of a 20:2:1 mixture of rat tail Type I collagen (Becton Dickinson), 10x phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and 7.5% NaHCO3 in a 35 mm plastic dish. Gel was solidified in a 38°C humidified incubator, rinsed with serum free M199 three times and drained. To test effects of BMPs on directional PE expansion, beads of Affi-Gel Blue Gel (Bio-Rad) were incubated for 30 min in PBS containing a growth factor (1μg/μl). BSA was used as a control. A PE and a heart segment or a growth factor-soaked bead(s) were placed on the gel 300–400 μm apart. Directional PE expansion was not evident with a distance greater than 500 μm or less than 250 μm under our culture conditions. The cultured PEs were photographed at 24 and 48 hr of incubation using phase contrast light microscopy. To quantify this preference, we traced the periphery of each explant using Photoshop software and compiled these images into an overlay using the centers of the PE and heart explants as landmarks to align.

In ovo lipofection

Preparation of expression constructs is described in Supplemental Experimental Procedures. Control experiments utilized pEGFP-N1 (Clontech) or a LacZ plasmid pCXIZ (Mima et al., 1995). Day 2 embryos (stage 13–14) were made accessible by creating a 20–30 mm diameter opening in the egg shell at the blunt end and removing shell and vitelline membranes directly over the embryo. For improved contrast and visualization, India ink (Koh-I-Noor Radiograph Rapidraw) was injected under the embryo using an insulin syringe. Transfection mixture was prepared as follows: 2 μg DNA and 2 μl Lipofectamine (per 50 μl of Opti-MEM I media) were combined per the manufacturer’s instruction (Invitrogen) and colored with 0.075% Fast Green. This transfection reagent was loaded into a pulled borosilicate glass capillary tube and injected into the pericardial space using a microinjector (Femtojet, Eppendorf). 10–15 injections of approximately 3 nl each of transfection reagent were distributed around the heart. Using an 18- gauge syringe, 1–3 ml of albumin was removed to lower the embryo, and a few drops of PBS containing 20 units/ml Penicillin and Streptomycin. The opening in the shell was sealed with parafilm and incubated at 38°C until the desired stage was reached. After 20 hr of culture transgene expression was evident in the heart region of all embryos with survival rates of 40–80%. Embryos transfected with all constructs exhibited similar survival rates in sibling experiments, with the exception of Bmp10-transfections, which exhibited twice the mortality. See Supplemental Data (Figure S2 and Supplemental Experimental Procedures) for full details.

In situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry

Whole-mount ISH of chicken hearts was performed as previously described (Hurtado and Mikawa, 2006) with antisense probes using Digoxigenin- or Fluorescein-labeled UTP (Roche) for synthesis of RNA probes from linearized DNA templates (Megascript, Ambion). Probes used in this study were chicken Tbx18, Noggin, Bmp2, Bmp4, Bmp5, Bmp7, Bmp10, Cx40, Tbx2, Bmpr1A, Bmpr1B, Bmpr2 and Gfp. To generate probes, the full length coding regions of chick Noggin, Bmp5, Bmp10, Tbx2 and Gfp were PCR amplified from cDNA or plasmid and cloned into pCRII using a TOPO cloning kit (Invitrogen). For color development, NBT/BCIP (dark purple, Roche), BCIP alone (light blue) or magenta-phosphate/red tetrazolium (magenta, Sigma) was used as substrate. Stained embryos were post fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS and paraffin sectioned by standard procedures. Rabbit primary antibodies used were: anticytokeratin (Bt-571, Biomedical Technologies), anti-Wt1 (C19, Santa-Cruz Biotechnologies), and anti-ZO1 (Zymed) detected with Alexa-Fluor-488 goat anti-rabbit IgG (Molecular Probes). BrdU was detected as described previously (Ishii et al., 2009b). Alcian blue 8GX (Sigma) was used to make a 1% staining solution in 3% acetic acid, final pH 2.5. Rehydrated paraffin sections were stained for 1 hour, rinsed in tap water, then PBS and counterstained in nuclear fast red solution (0.1% NFR, 5% aluminum sulfate) and rinsed in PBS before EtOH dehydration and mounting with permount (Fisher).

Real time PCR

Total RNAs were isolated using the RNasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) or Trizol (Invitrogen) and reverse transcribed using the SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Invitrogen) with an oligo-dT primer. Real time PCR used SYBR Green detection on a Bio-Rad iQ5 multicolor detection system as described by the iQ5 manufacturer’s application guide. Primer pairs were designed to amplify 120–200 bp exon spanning regions. For all primer pairs analysis of melt curve and amplification efficiency were performed (Bio-Rad). Relative expression levels were determined from cycle threshold (CT) values (Bio-Rad Optical System Software v2.0) using the 2iDDCT (Livak) method with ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) and/or (Gapdh) CT values as a reference. Primer sequences are available in Supplemental Table S1. Endpoint PCR described in Supplementary Data.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Related to Figure 2. This figure demonstrates effects of epicardial factors on PE expansion in vitro, supplementing the data of myocardial factors shown in Figure 2.

Figure S2 Related to Figure 4. This figure provides information of control experiments for lipofectamine transfection-mediated expression of exogenous genes in the myocardium in a tissue type selective and temporal specific manner.

Figure S3. Related to Figure 4. This figure demonstrates effects of Noggin-misexpression in the myocardium on various aspects of PE and myocardial cells during PE extension to the heart including myocardial marker expression, ECM, cell proliferation and apoptosis.

Figure S4. Related to Figure 5. This figure provides the data of gain-of-function experiments, showing that Bmp4-misexpression gives rise to mislocation of PE attachment sites to hearts. The data also present morphology, regional markers and ECM in Bmp2-misexpressing hearts.

Figure S5. Related to Figure 6. This figure shows in vitro activities of BMP4, BMP6 and BMP7 to orient PE expansion, supplementing the data of Fig 6.

Table S1. This table provides a list of PCR primers used for real time and end point PCR analyses, supplementing Materials and Methods.

Movie S1. Related to Figure 6. Supplementing the still image data in Fig 6, this movie provides a live image of directional cellular movement of PE cells in culture towards a AVJ explant, as a in vitro model mimicking a oriented PE extension.

Acknowledgments

We thank the lab of Dr. Cliff Tabin for providing the chicken Bmp2, Bmp4 and Bmp7 cDNAs; Dr. Jeanette Hyer for Bmpr1A, Bmpr1B, and Bmpr2; Dr. Kimiko Takebayashi-Suzuki for Cx40 cDNA; Dr. Thomas Brand for Tbx18 cDNA; and Mr. Romulo Hurtado for Tbx2 cDNA. Our thanks extend to Drs. Donald A. Fischman and Bettye Ridley for their collagen gel culture methods and to Kelley Rosborough and Jonathan Langberg for their technical assistance.

Footnotes

Supplemental Data include five figures, one table, one movie and Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abu-Issa R, Waldo K, Kirby ML. Heart fields: one, two or more? Dev Biol. 2004;272:281–285. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai CL, Martin JC, Sun Y, Cui L, Wang L, Ouyang K, Yang L, Bu L, Liang X, Zhang X, et al. A myocardial lineage derives from Tbx18 epicardial cells. Nature. 2008;454:104–108. doi: 10.1038/nature06969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capdevila J, Izpisua Belmonte JC. Patterning mechanisms controlling vertebrate limb development. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2001;17:87–132. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.17.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien KR, Domian IJ, Parker KK. Cardiogenesis and the complex biology of regenerative cardiovascular medicine. Science. 2008;322:1494–1497. doi: 10.1126/science.1163267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow RL, Lang RA. Early eye development in vertebrates. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2001;17:255–296. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.17.1.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danesh SM, Villasenor A, Chong D, Soukup C, Cleaver O. BMP and BMP receptor expression during murine organogenesis. Gene Expr Patterns. 2009;9:255–265. doi: 10.1016/j.gep.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decastro M, Saijoh Y, Schoenwolf GC. Optimized cationic lipid-based gene delivery reagents for use in developing vertebrate embryos. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:2210–2219. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dettman RW, Denetclaw W, Jr, Ordahl CP, Bristow J. Common epicardial origin of coronary vascular smooth muscle, perivascular fibroblasts, and intermyocardial fibroblasts in the avian heart. Dev Biol. 1998;193:169–181. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dettman RW, Pae SH, Morabito C, Bristow J. Inhibition of alpha4-integrin stimulates epicardial-mesenchymal transformation and alters migration and cell fate of epicardially derived mesenchyme. Dev Biol. 2003;257:315–328. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00064-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eralp I, Lie-Venema H, DeRuiter MC, van den Akker NM, Bogers AJ, Mentink MM, Poelmann RE, Gittenberger-de Groot AC. Coronary artery and orifice development is associated with proper timing of epicardial outgrowth and correlated Fas-ligandassociated apoptosis patterns. Circ Res. 2005;96:526–534. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000158965.34647.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Eralp I, Lie-Venema H, Bartelings MM, Poelmann RE. Development of the coronary vasculature and its implications for coronary abnormalities in general and specifically in pulmonary atresia without ventricular septal defect. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 2004;93:13–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2004.tb00234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Vrancken Peeters MP, Bergwerff M, Mentink MM, Poelmann RE. Epicardial outgrowth inhibition leads to compensatory mesothelial outflow tract collar and abnormal cardiac septation and coronary formation. Circ Res. 2000;87:969–971. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.11.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Vrancken Peeters MP, Mentink MM, Gourdie RG, Poelmann RE. Epicardium-derived cells contribute a novel population to the myocardial wall and the atrioventricular cushions. Circ Res. 1998;82:1043–1052. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.10.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guadix JA, Carmona R, Munoz-Chapuli R, Perez-Pomares JM. In vivo and in vitro analysis of the vasculogenic potential of avian proepicardial and epicardial cells. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:1014–1026. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haenig B, Kispert A. Analysis of TBX18 expression in chick embryos. Dev Genes Evol. 2004;214:407–411. doi: 10.1007/s00427-004-0415-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamburger V, Hamilton HL. A series of normal stages in the development of the chick embryo. 1951. Dev Dyn. 1992;195:231–272. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001950404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher CJ, Diman NY, Kim MS, Pennisi D, Song Y, Goldstein MM, Mikawa T, Basson CT. A role for Tbx5 in proepicardial cell migration during cardiogenesis. Physiol Genomics. 2004;18:129–140. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00060.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirakow R. Epicardial formation in staged human embryos. Kaibogaku Zasshi. 1992;67:616–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado R, Mikawa T. Enhanced sensitivity and stability in two-color in situ hybridization by means of a novel chromagenic substrate combination. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:2811–2816. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii Y, Langberg J, Rosborough K, Mikawa T. Endothelial cell lineages of the heart. Cell Tissue Res. 2009a;335:67–73. doi: 10.1007/s00441-008-0663-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii Y, Langberg JD, Hurtado R, Lee S, Mikawa T. Induction of proepicardial marker gene expression by the liver bud. Development. 2007;134:3627–3637. doi: 10.1242/dev.005280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii Y, Weinberg K, Oda-Ishii I, Coughlin L, Mikawa T. Morphogenesis and cytodifferentiation of the avian retinal pigmented epithelium require downregulation of Group B1 Sox genes. Development. 2009b;136:2579–2589. doi: 10.1242/dev.031344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahr M, Schlueter J, Brand T, Manner J. Development of the proepicardium in Xenopus laevis. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:3088–3096. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao K, Kulessa H, Tompkins K, Zhou Y, Batts L, Baldwin HS, Hogan BL. An essential role of Bmp4 in the atrioventricular septation of the mouse heart. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2362–2367. doi: 10.1101/gad.1124803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruithof BP, van Wijk B, Somi S, Kruithof-de Julio M, Perez Pomares JM, Weesie F, Wessels A, Moorman AF, van den Hoff MJ. BMP and FGF regulate the differentiation of multipotential pericardial mesoderm into the myocardial or epicardial lineage. Dev Biol. 2006;295:507–522. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwee L, Baldwin HS, Shen HM, Stewart CL, Buck C, Buck CA, Labow MA. Defective development of the embryonic and extraembryonic circulatory systems in vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM-1) deficient mice. Development. 1995;121:489–503. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.2.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavine KJ, Yu K, White AC, Zhang X, Smith C, Partanen J, Ornitz DM. Endocardial and epicardial derived FGF signals regulate myocardial proliferation and differentiation in vivo. Dev Cell. 2005;8:85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YH, Saint-Jeannet JP. Characterization of molecular markers to assess cardiac cushions formation in Xenopus. Dev Dyn. 2009;238:3257–3265. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Richardson JA, Olson EN. Capsulin: a novel bHLH transcription factor expressed in epicardial progenitors and mesenchyme of visceral organs. Mech Dev. 1998;73:23–32. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manner J. The development of pericardial villi in the chick embryo. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1992;186:379–385. doi: 10.1007/BF00185988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manner J. Experimental study on the formation of the epicardium in chick embryos. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1993;187:281–289. doi: 10.1007/BF00195766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manner J. Does the subepicardial mesenchyme contribute myocardioblasts to the myocardium of the chick embryo heart? A quail-chick chimera study tracing the fate of the epicardial primordium. Anat Rec. 1999;255:212–226. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0185(19990601)255:2<212::aid-ar11>3.3.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellgren AM, Smith CL, Olsen GS, Eskiocak B, Zhou B, Kazi MN, Ruiz FR, Pu WT, Tallquist MD. Platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta signaling is required for efficient epicardial cell migration and development of two distinct coronary vascular smooth muscle cell populations. Circ Res. 2008;103:1393–1401. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.176768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merki E, Zamora M, Raya A, Kawakami Y, Wang J, Zhang X, Burch J, Kubalak SW, Kaliman P, Belmonte JC, et al. Epicardial retinoid X receptor alpha is required for myocardial growth and coronary artery formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:18455–18460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504343102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikawa T, Borisov A, Brown AM, Fischman DA. Clonal analysis of cardiac morphogenesis in the chicken embryo using a replication-defective retrovirus: I. Formation of the ventricular myocardium. Dev Dyn. 1992;193:11–23. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001930104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikawa T, Gourdie RG. Pericardial mesoderm generates a population of coronary smooth muscle cells migrating into the heart along with ingrowth of the epicardial organ. Dev Biol. 1996;174:221–232. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mima T, Ueno H, Fischman DA, Williams LT, Mikawa T. Fibroblast growth factor receptor is required for in vivo cardiac myocyte proliferation at early embryonic stages of heart development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:467–471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.2.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkoff R, Rundus VR, Parker SB, Beyer EC, Hertzberg EL. Connexin expression in the developing avian cardiovascular system. Circ Res. 1993;73:71–78. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore AW, McInnes L, Kreidberg J, Hastie ND, Schedl A. YAC complementation shows a requirement for Wt1 in the development of epicardium, adrenal gland and throughout nephrogenesis. Development. 1999;126:1845–1857. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.9.1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morabito CJ, Dettman RW, Kattan J, Collier JM, Bristow J. Positive and negative regulation of epicardial-mesenchymal transformation during avian heart development. Dev Biol. 2001;234:204–215. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahirney PC, Mikawa T, Fischman DA. Evidence for an extracellular matrix bridge guiding proepicardial cell migration to the myocardium of chick embryos. Dev Dyn. 2003;227:511–523. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesbitt T, Lemley A, Davis J, Yost MJ, Goodwin RL, Potts JD. Epicardial development in the rat: a new perspective. Microsc Microanal. 2006;12:390–398. doi: 10.1017/S1431927606060533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesbitt TL, Roberts A, Tan H, Junor L, Yost MJ, Potts JD, Dettman RW, Goodwin RL. Coronary endothelial proliferation and morphogenesis are regulated by a VEGF-mediated pathway. Dev Dyn. 2009;238:423–430. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivey HE, Mundell NA, Austin AF, Barnett JV. Transforming growth factor-beta stimulates epithelial-mesenchymal transformation in the proepicardium. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:50–59. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennisi DJ, Mikawa T. FGFR-1 is required by epicardium-derived cells for myocardial invasion and correct coronary vascular lineage differentiation. Dev Biol. 2009;328:148–159. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Pomares JM, Carmona R, Gonzalez-Iriarte M, Atencia G, Wessels A, Munoz- Chapuli R. Origin of coronary endothelial cells from epicardial mesothelium in avian embryos. Int J Dev Biol. 2002;46:1005–1013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pombal MA, Carmona R, Megias M, Ruiz A, Perez-Pomares JM, Munoz-Chapuli R. Epicardial development in lamprey supports an evolutionary origin of the vertebrate epicardium from an ancestral pronephric external glomerulus. Evol Dev. 2008;10:210–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2008.00228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratajska A, Czarnowska E, Ciszek B. Embryonic development of the proepicardium and coronary vessels. Int J Dev Biol. 2008;52:229–236. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.072340ar. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reese DE, Mikawa T, Bader DM. Development of the coronary vessel system. Circ Res. 2002;91:761–768. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000038961.53759.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers LS, Lalani S, Runyan RB, Camenisch TD. Differential growth and multicellular villi direct proepicardial translocation to the developing mouse heart. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:145–152. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruppert R, Hoffmann E, Sebald W. Human bone morphogenetic protein 2 contains a heparin-binding site which modifies its biological activity. Eur J Biochem. 1996;237:295–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0295n.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutenberg JB, Fischer A, Jia H, Gessler M, Zhong TP, Mercola M. Developmental patterning of the cardiac atrioventricular canal by Notch and Hairy-related transcription factors. Development. 2006;133:4381–4390. doi: 10.1242/dev.02607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampath TK, Muthukumaran N, Reddi AH. Isolation of osteogenin, an extracellular matrix-associated, bone-inductive protein, by heparin affinity chromatography. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:7109–7113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.20.7109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlueter J, Manner J, Brand T. BMP is an important regulator of proepicardial identity in the chick embryo. Dev Biol. 2006;295:546–558. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte I, Schlueter J, Abu-Issa R, Brand T, Manner J. Morphological and molecular left-right asymmetries in the development of the proepicardium: a comparative analysis on mouse and chick embryos. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:684–695. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultheiss TM, Burch JB, Lassar AB. A role for bone morphogenetic proteins in the induction of cardiac myogenesis. Genes Dev. 1997;11:451–462. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.4.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengbusch JK, He W, Pinco KA, Yang JT. Dual functions of [alpha]4[beta]1 integrin in epicardial development: initial migration and long-term attachment. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:873–882. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200203075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serluca FC. Development of the proepicardial organ in the zebrafish. Dev Biol. 2008;315:18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snarr BS, Kern CB, Wessels A. Origin and fate of cardiac mesenchyme. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:2804–2819. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somi S, Buffing AA, Moorman AF, Van Den Hoff MJ. Dynamic patterns of expression of BMP isoforms 2, 4, 5, 6, and 7 during chicken heart development. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol. 2004a;279:636–651. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.20031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somi S, Buffing AA, Moorman AF, Van Den Hoff MJ. Expression of bone morphogenetic protein-10 mRNA during chicken heart development. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol. 2004b;279:579–582. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.20052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streit A, Stern CD. Neural induction. A bird’s eye view. Trends Genet. 1999;15:20–24. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(98)01620-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teichmann U, Kessel M. Highly restricted BMP10 expression in the trabeculating myocardium of the chick embryo. Dev Genes Evol. 2004;214:96–98. doi: 10.1007/s00427-003-0380-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomanek RJ, Holifield JS, Reiter RS, Sandra A, Lin JJ. Role of VEGF family members and receptors in coronary vessel formation. Dev Dyn. 2002;225:233–240. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomanek RJ, Ishii Y, Holifield JS, Sjogren CL, Hansen HK, Mikawa T. VEGF family members regulate myocardial tubulogenesis and coronary artery formation in the embryo. Circ Res. 2006;98:947–953. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000216974.75994.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Wijk B, Moorman AF, van den Hoff MJ. Role of bone morphogenetic proteins in cardiac differentiation. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;74:244–255. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Wijk B, van den Berg G, Abu-Issa R, Barnett P, van der Velden S, Schmidt M, Ruijter JM, Kirby ML, Moorman AF, van den Hoff MJ. Epicardium and Myocardium Separate From a Common Precursor Pool by Crosstalk Between Bone Morphogenetic Protein- and Fibroblast Growth Factor-Signaling Pathways. Circ Res. 2009 doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.203083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viragh S, Challice CE. The origin of the epicardium and the embryonic myocardial circulation in the mouse. Anat Rec. 1981;201:157–168. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092010117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viragh S, Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Poelmann RE, Kalman F. Early development of quail heart epicardium and associated vascular and glandular structures. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1993;188:381–393. doi: 10.1007/BF00185947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrancken Peeters MP, Mentink MM, Poelmann RE, Gittenberger-de Groot AC. Cytokeratins as a marker for epicardial formation in the quail embryo. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1995;191:503–508. doi: 10.1007/BF00186740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang EA, Rosen V, Cordes P, Hewick RM, Kriz MJ, Luxenberg DP, Sibley BS, Wozney JM. Purification and characterization of other distinct bone-inducing factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:9484–9488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.24.9484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y, Mikawa T. Formation of the avian primitive streak from spatially restricted blastoderm: evidence for polarized cell division in the elongating streak. Development. 2000;127:87–96. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessels A, Perez-Pomares JM. The epicardium and epicardially derived cells (EPDCs) as cardiac stem cells. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol. 2004;276:43–57. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.10129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White AC, Lavine KJ, Ornitz DM. FGF9 and SHH regulate mesenchymal Vegfa expression and development of the pulmonary capillary network. Development. 2007;134:3743–3752. doi: 10.1242/dev.004879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada M, Revelli JP, Eichele G, Barron M, Schwartz RJ. Expression of chick Tbx-2, Tbx-3, and Tbx-5 genes during early heart development: evidence for BMP2 induction of Tbx2. Dev Biol. 2000;228:95–105. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang JT, Rayburn H, Hynes RO. Cell adhesion events mediated by alpha 4 integrins are essential in placental and cardiac development. Development. 1995;121:549–560. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.2.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasugi S, Mizuno T. Molecular analysis of endoderm regionalization. Dev Growth Differ. 2008;50(Suppl 1):S79–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2008.00984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou B, Ma Q, Rajagopal S, Wu SM, Domian I, Rivera-Feliciano J, Jiang D, von Gise A, Ikeda S, Chien KR, Pu WT. Epicardial progenitors contribute to the cardiomyocyte lineage in the developing heart. Nature. 2008;454:109–113. doi: 10.1038/nature07060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman LB, De Jesus-Escobar JM, Harland RM. The Spemann organizer signal noggin binds and inactivates bone morphogenetic protein 4. Cell. 1996;86:599–606. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80133-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Related to Figure 2. This figure demonstrates effects of epicardial factors on PE expansion in vitro, supplementing the data of myocardial factors shown in Figure 2.

Figure S2 Related to Figure 4. This figure provides information of control experiments for lipofectamine transfection-mediated expression of exogenous genes in the myocardium in a tissue type selective and temporal specific manner.

Figure S3. Related to Figure 4. This figure demonstrates effects of Noggin-misexpression in the myocardium on various aspects of PE and myocardial cells during PE extension to the heart including myocardial marker expression, ECM, cell proliferation and apoptosis.

Figure S4. Related to Figure 5. This figure provides the data of gain-of-function experiments, showing that Bmp4-misexpression gives rise to mislocation of PE attachment sites to hearts. The data also present morphology, regional markers and ECM in Bmp2-misexpressing hearts.

Figure S5. Related to Figure 6. This figure shows in vitro activities of BMP4, BMP6 and BMP7 to orient PE expansion, supplementing the data of Fig 6.

Table S1. This table provides a list of PCR primers used for real time and end point PCR analyses, supplementing Materials and Methods.

Movie S1. Related to Figure 6. Supplementing the still image data in Fig 6, this movie provides a live image of directional cellular movement of PE cells in culture towards a AVJ explant, as a in vitro model mimicking a oriented PE extension.