Abstract

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) represents a burgeoning problem in hepatology, and is associated with insulin resistance. Exendin-4 is a peptide agonist of the glucagon-like peptide (GLP) receptor that promotes insulin secretion. The aim of this study was to determine whether administration of Exendin-4 would reverse hepatic steatosis in ob/ob mice. Ob/ob mice, or their lean littermates, were treated with Exendin-4 [10 μg/kg or 20 μg/kg] for 60 days. Serum was collected for measurement of insulin, adiponectin, fasting glucose, lipids, and aminotransferase concentrations. Liver tissue was procured for histological examination, real-time RT-PCR analysis and assay for oxidative stress. Rat hepatocytes were isolated and treated with GLP-1. Ob/ob mice sustained a reduction in the net weight gained during Exendin-4 treatment. Serum glucose and hepatic steatosis was significantly reduced in Exendin-4 treated ob/ob mice. Exendin-4 improved insulin sensitivity in ob/ob mice, as calculated by the homeostasis model assessment. The measurement of thiobarbituric reactive substances as a marker of oxidative stress was significantly reduced in ob/ob-treated mice with Exendin-4. Finally, GLP-1–treated hepatocytes resulted in a significant increase in cAMP production as well as reduction in mRNA expression of stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 and genes associated with fatty acid synthesis; the converse was true for genes associated with fatty acid oxidation. In conclusion, Exendin-4 appears to effectively reverse hepatic steatosis in ob/ob mice by improving insulin sensitivity. Our data suggest that GLP-1 proteins in liver have a novel direct effect on hepatocyte fat metabolism.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is reported in some Western countries to be the most common liver disease, surpassing the prevalence of chronic hepatitis C virus or alcoholic liver disease.1 NAFLD represents a disease spectrum ranging from simple steatosis to steatohepatitis and fibrosis. Approximately 3% of patients afflicted with NAFLD will develop cirrhosis.2,3 At present, the central pathophysiological problem in patients afflicted with NAFLD is insulin resistance. Thus, there is a clear association between NAFLD and the metabolic syndrome that includes type 2 diabetes mellitus, obesity, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. Improvement of insulin resistance, or insulin sensitivity, has therapeutic potential in preventing the progression of NAFLD because the accumulation of triglycerides in hepatocytes is believed to be the first step in the current two-hit hypothesis of the pathophysiological development of NAFLD.4 Hence, it is hypothesized that improving insulin sensitivity would reduce hepatocyte triglyceride accumulation, thereby preventing the second step of hepatocyte vulnerability to oxidative stress.4

Exendin-4 is a 39 amino acid agonist of the glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor. Exendin-4 is present in the saliva of the Gila monster, Heloderma suspectum. 5 GLP-1, a gastrointestinal hormone secreted by the L cells of the intestine, regulates blood glucose primarily via stimulation of glucose-dependent insulin release. However, the major drawback of its clinical use is its short biological half-life, necessitating continuous administration intravenously or by frequent subcutaneous injection.6 Importantly, Exendin-4 has a significantly longer half-life than GLP-1 and could be significant in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus and NAFLD.

Exendin-4 has not been used for the potential treatment of NAFLD; however, phase III clinical trials for type II diabetes have been completed by Amylin with the synthetic peptide exendintide.7 In addition to its effect as an incretin, Exendin-4 has been shown to reduce food intake in Zucker (ZDF) rats, but does not change serum leptin levels even though these animals sustained reductions in body weight, blood glucose, food intake, and subcutaneous and visceral fat after treatment.8 In addition to its insulin-releasing and appetite suppressant activity, GLP-1 is known to have direct insulin-like activity9,10; however, whether GLP-1 can act on hepatocytes directly is subject to dispute.11-14 Ob/ob mice have been extensively studied as a naturally occurring model of hepatic steatosis. These mice are leptin deficient because a mutation in the ob gene encoding leptin transcription prevents its biosynthesis.15 A recent review implicates a key enzyme component in the metabolic syndrome, stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 (SCD-1), a gene specifically repressed by leptin16,17 may be critical to the elimination of triglyceride accumulation in hepatocytes. Hence, we propose that GLP-1 not only has an indirect incretin effect that improves key parameters associated with NAFLD, but importantly demonstrate a direct insulin-like role for GLP-1 that results in repression of SCD-1 and other key regulatory genes in hepatocytes associated with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and hepatic triglyceride metabolism. Thus, synthetic GLP-1-like proteins with a prolonged half-life would be of biological and therapeutic benefit in NAFLD.

Materials and Methods

Use of ob/ob Mouse Model and Treatment With Exendin-4

Obese male (ob/ob) 6-week-old mice and their lean littermates were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). The animals were cared for in accordance with protocols approved by the Animal Care and Use Committees of Emory University. The mice were allowed ad libitum access to chow and water. Animals were on a 12-hour light, 12-hour dark cycle. Animals were acclimatized for 2 weeks.

For both ob/ob mice and their lean littermates the we followed the same treatment strategy. All animals were treated for 60 days. The Exendin-4 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) treatment groups were treated with 10 μg/kg every 24 hours for the first 14 days. This treatment was the induction phase. Respective control mice (lean and ob/ob) received saline every 24 hours. After 14 days Exendin-4–treated mice were randomly divided into two groups: one group received high dose Exendin-4 (20 μg/kg) every 12 hours, while the second group continued with low dose Exendin-4 (10 μg/kg) every 12 hours. The control mice continued to receive saline every 12 hours. The mice were weighed daily for the 60-day treatment period. At the completion of the study, fasting blood samples were obtained for glucose and insulin concentrations and homeostasis model of assessment (HOMA).18 Additional sera were obtained to measure serum glucose, triglycerides, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and adiponectin. Insulin and adiponectin levels were measured by enzyme immunoassay at Linco Research (St. Charles, MO). Total hepatectomy was performed at the time of euthanasia and liver samples were divided for histopathology and other analyses (see next section). To achieve statistical power of data outcome, 32 mice were used for the experiment and eight animals were included in each treatment arm.

Histological Aanalysis of Liver Tissue and Stain With Oil Red O

Formalin fixed tissue was processed and 5 μm–thick paraffin sections were stained with Oil Red O for histological analysis. Slides were viewed with a Nikon E1000M microscope (Melville, NY), and photographed with a Cool Snap color digital camera (Roper Scientific, Tucson, AZ). Quantitative analysis of Oil Red O–stained hepatic lipid was performed by morphometric analysis. Staining was quantified using Image-ProPlus version 4.5, software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD). All sections were examined by the same person who was blinded to treatment status. Ten random areas of interest were examined per liver section and were identified by computer-generated field identification. At least five different liver sections were examined for eight individual animals for each treatment group. Data for Oil Red O staining were expressed as the mean percentage of total hepatic area in the tissue sections: the total area stained was divided by the total area of the slide (μm2) and multiplied by 100 to give the percentage of area stained.

Assessment of Liver Lipid Content

Portions of the liver samples from each treatment group of mice were weighed and homogenized in 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, containing 150 mmol/L NaCl, 1 mmol/LM EDTA, 1 mmol/L DTT, and 1 μmol/L PMSF using a glass Dounce homogenizer. Liver lipid content of liver homogenates was measured by a spectrophotometric procedure as described elsewhere19 and expressed as lipid (mg)/g wet liver weight (g).

Assessment of Thiobarbituric Acid-Reactive Substances (TBARS)

Liver homogenates prepared for the analysis of liver lipid were centrifuged at 600 × g at 4°C, and the supernatants were used to assess TBARS by a spectrophotometric procedure and expressed as malondialdehyde produced (nmol)/protein (mg).

Reverse Transcription and Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR) of Whole Liver RNA

Complementary DNA (cDNA) was prepared by reverse transcription of total hepatic RNA or rat hepatocytes as previously described.20 Real-time PCR analysis was performed with the GeneAmp Sequence Detection System and software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using SYBR green detection (SREBP-1c, SCD-1, peroxisome proliferator activator receptor alpha [PPAR] α [see Table 1]). Ribosomal protein L19 (RPL19) was chosen as an internal standard. All samples were run in triplicate in 96-well reaction plate (MicroAmp Optical, Applied Biosystems) using appropriate primers. PCR products of each sample were normalized to their respective RPL19 (liver) expression values.

Table 1. Primer Pairs for Real-Time PCR of Genes Associated with Hepatic Fatty Acid Metabolism.

| Gene Name |

Accession # | Forward | Reverse | Product Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCD-1 | NM_139192 | GGGCGAGTCCTGATAAAACA | GTCTGCAGGAAAACCTCTGC | 125 |

| AOX | NM_017340 | GTTGATCACGCACATCTTGG | TGGCTTCGAGTGAGGAAGTT | 123 |

| SREBP-1c | XM_213329 | CAGGCTGAGAAAGGATGCTC | TCAGTGCCAGGTTAGAAGCA | 125 |

| PPARα | NM_013196 | CTCCCTCCTTACCCTTGGAG | GCCTCTGATCACCACCATTT | 124 |

| ACC | J03808 | GCCTCTTCCTGACAAACGAG | TCCATACGCCTGAAACATGA | 101 |

Hepatocyte Isolation, Culture, and Treatment With GLP-1

Single cell suspensions of hepatocytes were obtained from perfusions of Sprague–Dawley rats using the procedure of Berry and Friend21 and the perfusion mixture described elsewhere.22 Following collagenase perfusion, the hepatocyte cell suspension was mixed with a 15-mL Percoll (Sigma)-Hanks Buffered Salt Solution (HBSS, Gibco, Grand Island, NY) and spun at 470 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C. The final pellet was resuspended in 20 mL of RPMI after two centrifugations before plating into 24-well collagen-coated culture plates (BD-Biosciences, Bedford, MA), at a density of 0.15 mL cells/0.5 mL media, including 10% fetal bovine serum in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 2-mmol/L glutamine and penicillin-streptomycin. Cells were initially treated with 10 nmol/L or 100 nmol/L GLP-1 (Sigma) in accordance with previously published reports for 15 minutes, 30 minutes, 1 hour, or 3 hours.23,24 Exendin-4–treated hepatocytes were used as a positive control. A fraction of each cell preparation was analyzed for albumin (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA) by subjecting cell lysate to SDS-PAGE25 and immunoblot. Following treatment, hepatocytes were harvested, lysed, and probed for GLP-1 receptor (GLP-1R) using rabbit polyclonal-GLP-1R (a kind gift from Dr. Joel Hebener, Howard Hughes Institute, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) by Western blot as previously described.26 Cell lysates were also probed for Akt, pAkt, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), and pMAPK, (Cell Signaling). Total hepatocyte RNA was harvested from the cell cultures to conduct real-time RT-PCR for acetyl-CoA oxidase (AOX), PPARα, SCD-1, SREBP-1c, and acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) as described. Results were normalized to 18s RNA and studies were performed twice in triplicate.

cAMP Assay for GLP-1 and Exendin-4–treated Rat Hepatocytes

To determine whether either GLP-1 or Exendin-4 could promote a sustained increase in hepatocyte cAMP production, rat hepatocytes were isolated in the laboratory or purchased (Cambrex Bioscience Walkersville Inc., Walkersville, MD) and plated on collagen coated 6-well plates. After overnight serum starvation, cells were treated with GLP-1 (10 nmol/L) or Exendin-4 (10 nmol/L) for 3 hours. Forskolin (10μmol/L) was used a positive control, while in other experiments the Exendin Fragment 9-39 (1μmol/L), a competitive antagonist for GLP-1 or Exendin-4 receptor binding was used for 20 minutes, followed by GLP-1 or Exendin-4 for 3 hours. cAMP measurements were done in whole cell lysates using a competitive cAMP immunoassay kit (Applied Biosystems, Belford, MA) as per manufacturer’s instructions. Luminescence was measured with Luminoscan Ascent Thermo Labsystems (Needham Heights, MA).27 The results were expressed as cAMP production in pM/106 cells.

Statistical Analysis

The data are presented as the mean ± SE. Statistical analysis was performed using Graphpad Instat 3 software (www.graphpad.com). Groups were compared using parametric tests (paired Student t test or one-way ANOVA with posttest following statistical standards). P values of less than .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Exendin-4 Treatment Improved Serum ALT, Glucose and HOMA Scores in ob/ob Mice Compared to Saline-Treated Animals

Both low- and high-dose Exendin-4 treatment in ob/ob mice improved serum ALT and reduced serum glucose, insulin levels and calculated HOMA scores compared with saline-treated ob/ob mice (Table 2). Exendin-4–treated lean mice did not develop hypoglycemia or significantly lower HOMA scores compared with saline-treated lean mice (data not shown). Exendin-4 also significantly increased serum circulating adiponectin compared with saline-treated ob/ob control mice.

Table 2. Outcome Metabolic Parameters From Exendin-4–Treated ob/ob Mice.

| Lean-Saline | ob/ob-Saline | ob/ob-Exendin 4 (10μg/kg) | ob/ob-Exendin 4 (20μg/kg) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALT (U/L) | 46.5 ± 6.5 | 123.2 ± 18.9 | 100.0 ± 6.3 | 57.6 ± 4.8* |

| Insulin (iU/mL) | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 13.4 ± 1.8 | 5.5 ± 0.6** | 3.3 ± 0.4** |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 7.66 ± 0.4 | 18.1 ± 2.0 | 14.7 ± 1.3 | 10.5 ± 0.6* |

| HOMA | 0.65 ± 0.07 | 10.8 ± 1.2 | 3.6 ± 0.3 | 1.54 ± 0.1* |

| Adiponectin | 15.7 ± 1.0 | 27.5 ± 0.1 | 32.1 ± 0.1 | 34.7 ± 1.0* |

P < .05 (Student t test) between online and exendin ob/ob mice.

P < .001 (Student t test) between online and exendin-4 ob/ob mice.

Exendin-4 Treatment Reduced the Net Weight Gain in ob/ob Mice

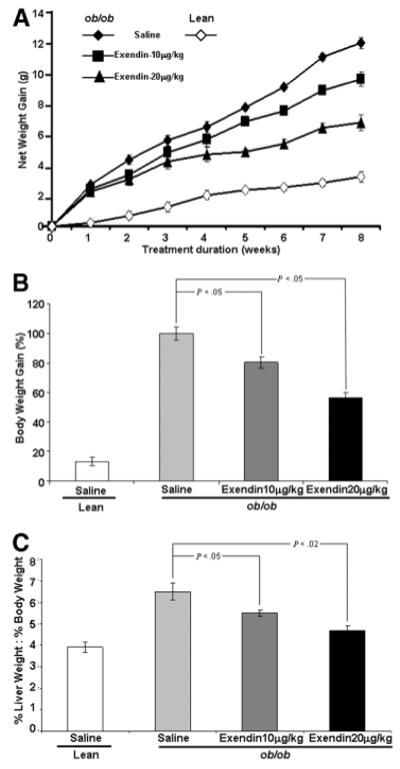

At the conclusion of the study, there was a significant difference in the weight of Exendin-4–treated ob/ob mice in either the low- or high-dose treatment groups compared with ob/ob saline-treated mice (Fig. 1A). In particular, Exendin-4–treated ob/ob mice sustained a marked reduction in the net weight gain in the final 4 weeks of the study period. Low-dose Exendin-4–treated ob/ob mice sustained a reduction of 7% body weight; high-dose–treated animals sustained a net weight reduction of 14% compared with saline-treated ob/ob mice (Fig. 1B). The ratio of liver weight to body weight was significantly reduced in the Exendin-4–treated ob/ob mice compared with saline-treated ob/ob mice (Fig. 1C). These data are in keeping with the overall effect of improved insulin resistance and release of adiponectin from adipocytes that leads to a reduction in hepatic lipid content.30-32

Fig. 1.

The effect of Exendin-4 administration on the rate of net weight gain in ob/ob and their lean littermates. (A) All mice were weighed daily and administration of Exendin-4 is as described in the text for a total of 8 weeks. The data are mean weight in grams (g) for animals in each group (8 animals/group) outlined ± SE. (B) represents the percent reduction of weight gained at the completion of the experiment and compares mean body weight of treated ob/ob mice to their respective treated saline controls. (C) Effect of Exendin-4 administration on the ratio of liver weight to body weight for the respective animals at the time of sacrifice.

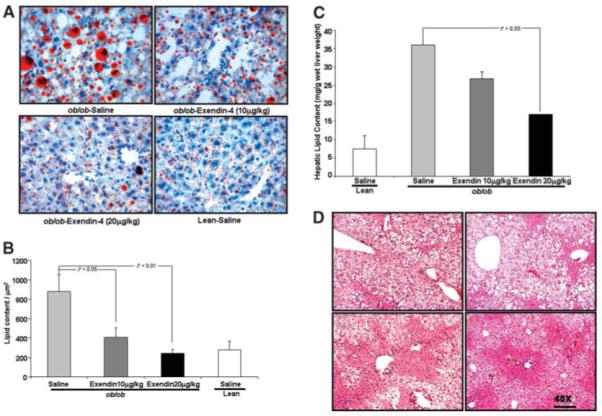

Exendin-4 Treatment Resulted in Histological Improvement in Fat Content of Liver Tissue in ob/ob Mice

Exendin-4–treated ob/ob mice had a significant reduction of fat content as assessed by Oil-Red O staining (Fig. 2A), confirmed by quantitative histomorphometry (Fig. 2B). Data shown reveal a dose-dependent reduction in hepatic lipid content/μm2. Similarly, there was reduction in total hepatic lipid content/g of wet-liver-weight for both doses of Exendin-4 treatment in ob/ob mice compared with saline treatment. These findings correlated with the histological data (Fig. 2C). Hematoxlyn and Eosin–stained tissue from respective treatment groups confirms improvement in hepatic histology following treatment (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Assessment of lipid content and hepatic histology in the liver of ob/ob mice and their lean littermates after Exendin-4 treatment. (A) Representative hepatic histology of saline-treated ob/ob mice, mice treated with low-dose and high-dose Exendin-4, and lean littermates treated with saline. Liver sections were stained with Oil Red O and Giemsa stain for nuclei. Original magnification: 40×. (B) Quantitative histomorphometric analysis for total lipid content of all hepatic histology for each treatment group; statistical analysis is with respect to saline-treated ob/ob histology. Histomorphometric analysis employed ImageProPlus as described in Materials and Methods. (C) Quantitation of lipid content per gram (wet weight) of liver from ob/ob mice was performed as described in Materials and Methods. Data are mean values performed in triplicate on eight specimens and reveal a significant decrease following high-dose Exendin-4 treatment. (D) Hematoxylin and Eosin staining of liver sections from ob/ob mice and their lean littermates following Exendin-4 treatment; panels are displayed exactly as in (A). Original magnification: 40×.

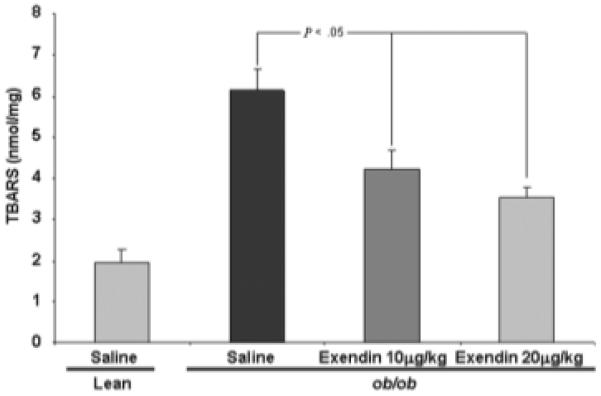

Exendin-4 Reduces TBARS in ob/ob Mice

Exendin-4-treated ob/ob mice exhibited a significant decrease in hepatic TBARS concentration compared with saline-treated ob/ob mice (Fig. 3), indicating that Exendin-4 treatment reduced one key parameter assessing hepatic oxidative stress, a putative factor in the progression of NAFLD and NASH.

Fig. 3.

TBAR measurements following Exendin-4 treatment reveals that high-dose therapy resulted in significant reduction in oxidative stress. The experiment was designed as described in Materials and Methods and Figs. 1 and 2. The data displayed are mean values ± SE for ob/ob mice treated with low-dose and high-dose Exendin-4 and saline. Values are compared with those of saline-treated ob/ob mice.

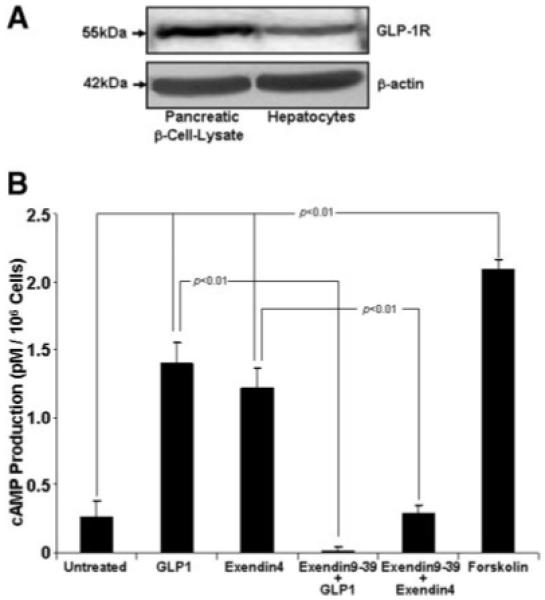

Identification of GLP-1R in Hepatocytes and Stimulation of Hepatocyte cAMP Production by GLP-1 or Exendin-4

GLP-1 receptor was detected by immunoblot analysis in isolated rat hepatocytes (Fig. 4A). Exendin-4 or GLP-1 ligand-receptor binding failed to significantly increase hepatocyte MAPK and Akt phosphorylation, as indicated in recent studies,33 when compared with untreated cell lysates (data not shown); however, GLP-1, and Exendin-4 treatment resulted in a marked increase in cAMP production (Fig. 4B). cAMP activity was significantly reduced to below basal levels (untreated hepatocytes) when hepatocytes were pretreated with the GLP-1R receptor antagonist Exendin fragment 9-39 (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Glucagon-like protein-1 receptor (GLP-1) detection and signaling through cAMP. (A) Immunoblot for rat hepatocyte lysates was performed as described in Materials and Methods. Anti-GLP-1R was a kind gift of Dr. Joel Hebener, Howard Hughes Institute; antibody titer (1:500). Pancreatic βcells were used as a positive control. The representative immunoblot is from three independent experiments. (B) Hepatocyte treatment with either GLP-1 or Exendin-4 significantly increased cAMP production. Shown are the mean cAMP production in pM/106 cells ± SE and compared with untreated hepatocytes. Pretreatment with the GLP-1 antagonist, Exendin fragment 9-39, abolished cAMP production by either GLP-1 or Exendin-4 in rat hepatocytes. Statistical analysis compares mean cAMP values ± SE vs. respective treatments alone. Forskolin served as a positive control. These experiments were performed three times in triplicate.

Exendin-4 Improved PPARα but Reduced SCD-1 and SREBP-1c mRNA in Whole Liver and in Hepatocytes

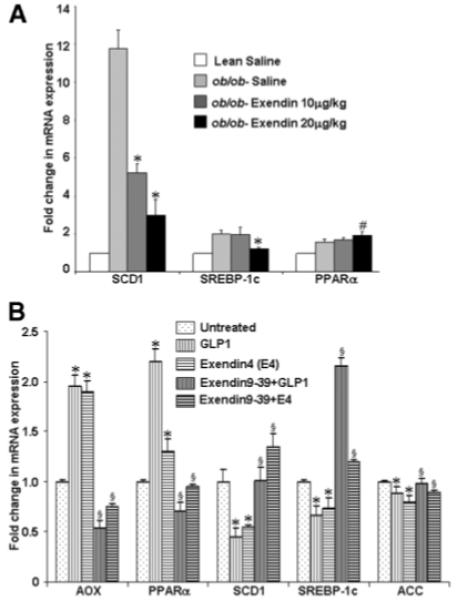

Real-time RT-qPCR revealed that Exendin-4 treatment significantly reduced hepatic mRNA expression levels of SREBP-1c and SCD1, key regulators of de novo hepatic lipogenesis, compared with saline-treated ob/ob mice. PPARα mRNA, a key element in β-oxidation of free fatty acids was significantly increased (Fig. 5A). In either GLP-1 or Exendin-4–treated rat hepatocytes there was a significant reduction in ACC, SCD-1, and SREBP-1c mRNA along with a significant increase in PPARα and AOX (Fig. 5B). GLP-1 receptor antagonism by pretreatment with Exendin fragment 9-39 (1μmol/L) in cultured hepatocytes failed to reduce mRNA expression of SCD-1, ACC, and SREBP-1c, while PPARα, and AOX mRNA were not significantly increased from basal levels (Fig. 5B). Taken together, blockade of GLP-1R abolished the net positive effects of either Exendin-4 or GLP-1 on expression of key genes that would result in a net reduction of hepatic fatty acid either by increased oxidation or inhibition of de novo lipogenesis.

Fig. 5.

The effect of Exendin-4 on mRNA expression of genes encoding SCD-1, SREBP-1c, and PPARα from whole livers in lean and ob/ob mice. (A) Total RNA extracted from liver tissues was used for mRNA expression analysis of SCD-1, SREBP-1c, and PPARα by RT-qPCR as described in Materials and Methods. Level of mRNA expression observed in lean mice treated with saline was set as 100% control; ob/ob mice treated with low-dose Exendin-4 and high-dose Exendin-4 were compared with the ob/ob mice that were treated with saline. Results are expressed as mean ± SE; n = 4 for each group. Each experiment was performed on three separate occasions in triplicate, *P < .01, #P < .05. (B) GLP-1– or Exendin-4–treated cultured rat hepatocytes were harvested for total RNA as described in Materials and Methods. cDNA primers were employed as detailed in Table 1. RT-qPCR was performed for each experiment three times in triplicate for AOX, PPARα, SCD1, SREBP-1c, and ACC. Data represent significant increases in genes associated with oxidation of fatty acids (*P < .05) with concomitant decreases in genes associated with fatty acid and triglyceride synthesis (*P < .05). Data presented are mean values ± SE. Data for GLP-1 and Exendin-4 are compared to untreated rat hepatocytes in serum free-media; data for GLP-1 or Exendin-4 pretreated with Exendin-9-39 are compared with data from respective treatments alone. Pretreatment with Exendin-9-39 abolished the positive effects of either GLP-1 or Exendin-4 on the mRNA for the genes outlined in (B) when compared with their respective treatments alone, §P < .05.

Discussion

To date, the two-hit hypothesis has emerged as a framework from which investigators are working to unravel how NAFLD may progress beyond steatosis and hepatitis to cirrhosis. At present, the most promising therapy for NASH appears to involve the use of PPARγ agonists, or thiazolidenediones. The most compelling rationale to date for this therapy was a 48-week clinical trial that demonstrated improvement during the treatment period. Follow-up data after discontinuation of therapy, however, abolished therapeutic benefits, including serum ALT reduction.34,35 Also, patients treated for this period gained an average of 3.5 kg. Metformin has also been shown to reduce hepatic steatosis in ob/ob mice36 but its effects in a recently published pilot trial were associated with transient improvement in liver chemistries; a progressive, sustainable reduction in insulin sensitivity was not noted.37

We reasoned that if insulin resistance was a fundamental problem in the genesis of hepatic steatosis, then using an agent that improves insulin resistance would optimize elimination of liver fat. GLP-1 is known to improve insulin resistance as an incretin and it has already been tested in humans for toxicity and side effects. GLP-like proteins are even more attractive because they have anorexigenic potential, which the thiazolidenediones or other potential treatments do not appear to possess. A growing body of literature suggests that gut peptides, GLP-1, and gastrointestinal inhibitory peptide have numerous effects on the cells of other organs, aside from pancreatic β-cells.38 The data regarding GLP-1 action on hepatocytes have not been convincing, however. Furthermore, compound knock-out mice lacking gastrointestinal inhibitory peptide and GLP-1 appear to have only a modest effect on glucose metabolism.

Our data suggest that Exendin-4 improves insulin resistance in ob/ob mice as assessed by glucose and HOMA scores, and significantly reduces hepatic lipid stores. Clearly there are histological improvement and improved ALT values. Finally, consistent with the anorexigenic property of Exendin-4, treated ob/ob mice sustain a marked reduction in net weight gain and a reduced liver weight/body weight ratio. We have also demonstrated that adiponectin levels in the Exendin-4–treated ob/ob mice also increased, which may be hepatoprotective, as indicated by other recent reports in this journal and elsewhere.39-41 TBARs were also reduced in the high-dose (20μg/kg) Exendin-4–treated animals that received Exendin-4 twice daily, indicating that even short-term therapy has a potentially important biological effect.

Exendin-4 appears to have a considerably longer half-life in humans, 33 ± 4 min, compared with the biologically active intact GLP-1 of 1-3 minutes42; and human data are available regarding potential benefits of Exendin-4, along with a reasonably safe profile with side effects such as nausea43 reported. Other attractive properties of GLP-1, including reduced food intake and body weight in rats,44,45 have also been demonstrated in human studies.7,46-48 Although the effect on satiety may be due to GLP-1–induced delayed gastric emptying,49 a direct satiety effect of Exendin-4 has not yet been shown.7 Studies in other animal models of NASH and clinical pilot studies in humans will need to be conducted. While we employed weight-based dosing, the 20μg/kg dose was clearly more effective. Our data are in agreement with a recent human study that demonstrated that Exendin-4 improved glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes who failed sulfonylurea monotherapy, using a maximal dose of 20μg/day.50

As previously indicated, improved insulin resistance could account for a significant reduction in SCD-1 mRNA in treated ob/ob mice. The most exciting findings presented here are those associated with a direct action of GLP-1 or Exendin-4 on hepatocytes, including the enhanced production of cAMP, which is abolished by a competitive receptor antagonist for GLP-1R. This study shows that either GLP-1 or Exendin-4 has direct action on hepatocytes and subsequently results in a gene profile that is conducive to reduction in fatty acid synthesis and triglyceride storage in hepatocytes. Importantly, the resultant gene profile from GLP-1–treated hepatocytes—increased mRNA for both PPARα and AOX—along with decreased mRNA expression for SCD-1, SREBP-1c, and ACC, raises the speculation that GLP-1 impairs hepatocyte de novo lipogenesis and/or enhances β-oxidation of fatty acids. While these findings are novel, they merit further and careful testing because it is unclear whether the ligand GLP-1 is actually binding its respective receptor in liver. Whether another GLP-1R isoform exists is subject to speculation. In conjunction with our in vivo data, we can assert, however, that GLP-1 does have a direct effect on hepatocyte fat metabolism.

It could be argued that by failing to measure caloric intake in the Exendin-4–treated obese animals, we could not accurately assess whether Exendin-4 acted more as an appetite suppressant and thereby accounted for these improved physiological parameters. In clinical settings, patient food intake can rarely be controlled, and reduced caloric intake in the treatment of metabolic syndrome is worthwhile. Another valid criticism is that of the animal model we chose as representative of NAFLD. Although there are many putative animal models for NAFLD and NASH, all have shortcomings.

In summary, Exendin-4 has several benefits over other recent medical therapies for NASH. It does not appear to be hepatotoxic, it is an appetite suppressant, and it functions as an incretin without development of hypoglycemia. GLP-1 possesses potential for a direct lipid-lowering effect on hepatocytes, which would be tremendously beneficial in the treatment of NAFLD. Future work should be undertaken to confirm and expand these potentially important therapeutic and novel biologic findings.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants AA12933, DK062092, and the Emory Digestive Disease Research Development Center DK064399.

Abbreviations

- NAFLD

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- GLP-1

glucagon-like peptide-1

- SCD-1

stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1

- NASH

nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- HOMA

homeostasis model assessment

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- cDNA

complementary DNA

- SREBP-1c

sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1

- GLP-1R

glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- PPARα

peroxisome proliferator activator receptor alpha

- AOX

acetyl-CoA oxidase

- ACC

Acetyl-CoA carboxylase

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- RPL19

ribosomal protein L19

- RT-qPCR

real-time quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

- TBARS

thiobarbituric reactive substances

Footnotes

Xiaokun Ding and Neeraj K. Saxena contributed equally to this work.

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

References

- 1.Clark JM, Brancati FL, Diehl AM. The prevalence and etiology of elevated aminotransferase levels in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:960–967. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCullough AJ. Update on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34:255–262. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200203000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neuschwander-Tetri BA. Evolving pathophysiologic concepts in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2002;4:31–36. doi: 10.1007/s11894-002-0035-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Day C, James O. Steatohepatitis: a tale of two “hits”. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:842–845. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70599-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Egan J, Clocquet A, Elahi D. The insulinotropic effect of acute Exendin-4 administered to humans: comparison of non-diabetic state to type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:1282–1290. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.3.8337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kieffer TJ, McIntosh CH, Pederson RA. Degradation of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide and truncated glucagon-like peptide 1 in vitro and in vivo by dipeptidyl peptidase IV. Endocrinology. 1995;136:3585–3596. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.8.7628397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edwards CM, Stanley SA, Davis R, Brynes AE, Frost GS, Seal LJ, et al. Exendin-4 reduces fasting and postprandial glucose and decreases energy intake in healthy volunteers. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2001;281:E155–E161. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.281.1.E155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Szayna M, Doyle M, Betkey J, Holloway H, Spencer R, Greig N, et al. Exendin-4 decelerates food intake, weight gain, and fat deposition in Zucker rats. Endocrinology. 2000;141:1936–1941. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.6.7490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valverde I, Morales M, Clemente F, Lopez-Delgado MI, Delgado E, Perea A, et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1: a potent glycogenic hormone. FEBS Lett. 1994;349:313–316. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00699-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.D’Alessio DA, Kahan SE, Leusner CR, Ensinck JW. Glucagon-like peptide 1 enhances glucose tolerance both by stimulation of insulin release and by increasing insulin-independent glucose disposal. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:2263–2266. doi: 10.1172/JCI117225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ikezawa Y, Yamatani K, Ohnuma H, Daimon M, Manaka H, Sasaki H. Glucagon-like peptide-1 inhibits glucagon-induced glycogenolysis in perivenous hepatocytes specifically. Regulatory Peptides. 2003;111:207–210. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(02)00287-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lopez-Delgado MI, Morales M, Villanueva-Penacarrillo ML, Malaisse WJ, Valverde I. Effect of glucagon-like peptide 1 on the kinetics of glycogen synthase a in hepatocytes from normal and diabetic rats. Endocrinology. 1998;139:2811–2817. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.6.6045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murayama Y, Kawai K, Suzuki S, Ohashi S, Yamashita K. Glucagon-like peptide-1(7-37) does not stimulate either hepatic glycogenolysis or ketogenesis. Endocrinol Jpn. 1990;37:293–297. doi: 10.1507/endocrj1954.37.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blackmore PF, Mojsov S, Exton JH, Hebener JF. Absence of insulinotropic glucagon-like peptide-I(7-37) receptor isolated rat liver hepatocytes. FEBS Lett. 1991;283:7–10. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80541-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedman JM, Leibel RL, Siegerl DS, Walsh J, Bahary N. Molecular mapping of the mouse ob mutation. Genomics. 1991;11:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(91)90032-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen P, Friedman M. Leptin and the control of metabolism: role for stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 (SCD-1) J Nutr. 2004;134:2455S–2463S. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.9.2455S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen P, Miyazaki M, Socci ND, Hagge-Greenberg A, Liedtke W, Soukas AA, et al. Role for stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 in leptin-mediated weight loss. Science. 2002;297:240–243. doi: 10.1126/science.1071527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28:412–419. doi: 10.1007/BF00280883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Briaud I, Harmon JS, Kelpe CL, Segu VBG, Poitout V. Lipotoxicity of pancreatic β-cell is associated with glucose-dependent esterification of fatty acids into neutral lipids. Diabetes. 2001;50:315–321. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.2.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;132:6–13. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berry MN, Friend DS. High-yield preparation of isolated rat liver parenchymal cells: a biochemical and fine structural study. J Cell Biol. 1969;43:506–520. doi: 10.1083/jcb.43.3.506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rippe RA, Brenner DA, Leffert HL. DNA-mediated gene transfer into adult rat hepatocytes in primary culture. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:689–695. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.2.689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kemp DM, Hebener JF. Insulinotropic hormone glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) activation of insulin gene promoter inhibited by p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Endocrinology. 2001;142:1179–1187. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.3.8026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vila Petroff MG, Egan JM, Wang X, Sollott SJ. Glucagon-like peptide-1 increases cAMP but fails to augment contraction in adult rat cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 2001;89:445–452. doi: 10.1161/hh1701.095716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saxena NK, Titus MA, Ding X, Floyd J, Srinivasan S, Sitaraman SV, et al. Leptin as a novel profibrogenic cytokine in hepatic stellate cells: mitogenesis and inhibition of apoptosis mediated by extracellular regulated kinase (Erk) and Akt phosphorylation. FASEB J. 2004;18:1612–1614. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1847fje. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kolachala V, Asamoah V, Wang L, Srinivasan S, Merlin D, Sitaraman SV. Interferon-gamma down-regulates adenosine 2b receptor-mediated signaling and short circuit current in the intestinal epithelia by inhibiting the expression of adenylate cyclase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:4048–4057. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409577200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kullmann M, Gopfert U, Siewe B, Hengst L. ELAV/Hu proteins inhibit p27 translation via an IRES element in the p27 5′UTR. Genes Dev. 2002;16:3087–3099. doi: 10.1101/gad.248902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rajendran RR, Nye AC, Frasor J, Balsara RD, Martini PG, Katzenellenbogen BS. Regulation of nuclear receptor transcriptional activity by a novel DEAD box RNA helicase (DP97) J Biol Chem. 2003;278:4628–4638. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210066200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maeda K, Ishihara K, Miyake K, Kaji Y, Kawamitsu H, Fujii M, et al. Inverse correlation between serum adiponectin concentration and hepatic lipid content in Japanese with type 2 diabetes. Metabolism. 2005;54:775–780. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2005.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taskinen MR. Type 2 diabetes as a lipid disorder. Curr Mol Med. 2005;5:297–308. doi: 10.2174/1566524053766086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rangwala SM, Rhoades B, Shapiro JS, Rich AS, Kim JK, Shulman GI, et al. Genetic modulation of PPARγ phosphorylation regulates insulin sensitivity. Dev Cell. 2003;5:657–663. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00274-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Redondo A, Trigo MV, Acitores A, Valverde I, Villaneuva-Penacarrillo ML. Cell signalling of the GLP-1 action in rat liver. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2003;204:43–50. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(03)00146-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Promrat K, Lutchman G, Uwaifo GI, Freedman RJ, Soza A, Heller T, et al. A pilot study of pioglitazone treatment for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2004;39:188–196. doi: 10.1002/hep.20012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Brunt EM, Wehmeier KR, Oliver D, Bacon BR. Improved nonalcoholic steatohepatitis after 48 weeks of treatment with the PPAR-gamma ligand rosiglitazone. Hepatology. 2003;38:1008–1017. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin HZ, Yang SQ, Chuckaree C, Kuhajda F, Ronnet G, Diehl AM. Metformin reverses fatty liver disease in obese, leptin-deficient mice. Nat Med. 2000;6:998–1003. doi: 10.1038/79697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nair S, Diehl AM, Wiseman M, Farr GH, Perrillo RP. Metformin in the treatment of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: a pilot open label trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:23–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yip RG, Wolfe MM. GIP and fat metabolism. Life Sci. 2000;66:91–103. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00314-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaser S, Moschen A, Cayon A, Kaser A, Crespo J, Pons-Romero F, et al. Adiponectin and its receptors in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Gut. 2005;54:117–121. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.037010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kamada Y, Tamura S, Kiso S, Matsumoto H, Saji Y, Yoshida Y, et al. Enhanced carbon tetrachloride-induced liver fibrosis in mice lacking adiponectin. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1796–1807. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu A, Wang Y, Keshaw H, Xu LY, Lam KS, Cooper GJ. The fat-derived hormone adiponectin alleviates alcoholic and nonalcoholic fatty liver diseases in mice. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:91–100. doi: 10.1172/JCI17797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lindsay JR, Duffy NA, McKillop AM, Ardill J, O’Harte FP, Flatt PR, et al. Inhibition of dipeptidyl peptidase IV activity by oral metformin in type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2005;22:654–657. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nauck MA, Meier JJ. Glucagon-like peptide 1 and its derivatives in the treatment of diabetes. Regul Pept. 2005;128:135–148. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2004.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meeran K, O’Shea D, Edwards CM, Turton MD, Heath MM, Gunn I, et al. Repeated intra-cerebro-ventricular administration of glucagon-like peptide-1(7-36) amide or Exendin (9-39) alters body weight in the rat. Endocrinology. 1999;40:244–250. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.1.6421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Turton MD, O’Shea D, Gunn I, Beak SA, Edwards CM, Meeran K, et al. A role for glucagon-like peptide-1 in the central regulation of feeding. Nature. 1996;379:69–72. doi: 10.1038/379069a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Edwards CM, Todd JF, Mahmoudi M, Wang Z, Wang RM, Ghatei MA, et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 has a physiological role in the control of postprandial glucose in man. Studies with the antagonist Exendin 9-39. Diabetes. 1999;48:86–93. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Flint A, Raben A, Astrup A, Holst JJ. Glucagon-like peptide 1 promotes satiety and suppresses energy intake in humans. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:515–520. doi: 10.1172/JCI990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Naslund E, Barkeling B, King N, Gutniak M, Blundell JE, Holst JJ, et al. Energy intake and appetite are suppressed by glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) in obese men. Int J Obes. 1999;23:304–311. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schirra J, Goke B. The physiological role of GLP-1 in human: incretin, ileal brake or more? Regul Pept. 2005;128:109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2004.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Buse JB, Henry RR, Han J, Kim DD, Fineman MS, Baron AD, the Exenatide-113 Clinical Study Group Effects of exenatide (exendin-4) on glycemic control over 30 weeks in sulfonylurea-treated patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2628–2635. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.11.2628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]