Abstract

The circadian rhythm of the cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus is controlled by three proteins, KaiA, KaiB, and KaiC. In a test tube, these proteins form complexes of various stoichiometry and the average phosphorylation level of KaiC exhibits robust circadian oscillations in the presence of ATP. Using mathematical modeling, we were able to reproduce quantitatively the experimentally observed phosphorylation dynamics of the KaiABC clockwork in vitro. We thereby identified a highly non-linear feedback loop through KaiA inactivation as the key synchronization mechanism of KaiC phosphorylation. By using the novel method of native mass spectrometry, we confirm the theoretically predicted complex formation dynamics and show that inactivation of KaiA is a consequence of sequestration by KaiC hexamers and KaiBC complexes. To test further the predictive power of the mathematical model, we reproduced the observed phase synchronization dynamics on entrainment by temperature cycles. Our model gives strong evidence that the underlying entrainment mechanism arises from a temperature-dependent change in the abundance of KaiAC and KaiBC complexes.

Keywords: biological network modeling, circadian clock, cyanobacteria, native mass spectrometry, temperature entrainment

Introduction

Circadian clocks coordinate daily repeating environmental patterns within many organisms and make important contributions to their fitness. Among the simplest organisms using circadian rhythms is the cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942. In this organism, most genes show rhythmic expression. Mutant strains of this organism have revealed that three genes, kaiA, kaiB, and kaiC, are the essential components of the circadian oscillator (Ishiura et al, 1998). In a pioneering work, Kondo and colleagues showed that the circadian rhythm of S. elongatus does not require any transcriptional or translational feedbacks to function (Tomita et al, 2005), and circadian oscillations can be reconstituted in vitro by mixing Kai proteins and ATP (Nakajima et al, 2005).

The apparent simplicity of an oscillator involving only three components is in strong contrast to the outstanding precision of the bacterial circadian clockwork, showing in-phase oscillations over >1 week (Mihalcescu et al, 2004). Moreover, cells that are exposed to constant low-light conditions divide synchronously and hand over their circadian phase to the daughter cells, without measurable phase shifts. A similar stability of the circadian oscillations has been observed in vitro for the phosphorylation kinetics of the KaiABC system (Ito et al, 2007). The question arises what benefit phototrophic organisms gain from a circadian oscillator whose phase is stable over several generations. Intuitively, much simpler mechanisms—like the synthesis of a specific molecule in the presence of light followed by overnight degradation—should be sufficient to give an approximate prediction for the duration of the night and the time of sunrise. However, if we assume the more realistic scenario that cyanobacteria gain an evolutionary advantage by orchestrating their metabolic activity to the day light intensity in a most reliable way, a highly robust but entrainable oscillator is likely the optimal solution. This is evident from the fact that day light intensity and temperature fluctuate on time scales of hours and days. A perfectly stable 24 h oscillator, whose phase changes only to very small extend under day-to-day variations in external zeitgebers, naturally averages over short-term fluctuations. However, a deficiency arises, as the phase of a biochemical oscillator cannot be perfectly robust against intracellular perturbations. This follows from the fact that noise in molecular reactions and stochasticity in the expression of clock genes can induce a significant phase drift on the time scale of weeks. From this viewpoint, we expect the evolved entrainment mechanism to account for this tradeoff and that it is fast enough to stabilize noise-induced phase drift but slow enough to allow for averaging over light intensity for several days.

In the following, we elucidate the mechanistic design of the KaiABC oscillator and shed light on the selective forces that shaped robustness and entrainability of the bacterial circadian clock. This requires a detailed mathematical understanding of the interplay between the clock components. Like any chemical oscillator, the KaiABC clock requires at least one negative feedback loop that rhythmically alternates the net transition rates between the dynamical states of the system (Novák and Tyson, 2008). A number of different molecular mechanisms have been proposed to generate sufficiently strong negative feedbacks to arrive at the experimentally observed high amplitude of total KaiC phosphorylation (Emberly and Wingreen, 2006; Mehra et al, 2006; Clodong et al, 2007; Mori et al, 2007; Yoda et al, 2007; van Zon et al, 2007). An approach that accounts for the different KaiC phospho-forms has been introduced by Rust et al (2007), in which it has been shown experimentally that KaiA is globally inactivated whenever the amount of serine phosphorylated KaiC is sufficiently high. However, the underlying molecular mechanism of KaiA inactivation has not been identified so far.

Here, we show by mathematical modeling in combination with measurements of the KaiABC complex formation dynamics using native mass spectrometry that oscillations in the Kai system are a consequence of KaiA sequestration by KaiC hexamers and KaiBC complexes. The sequestration dynamics show thereby a highly non-linear dependency on the phosphorylation state of KaiC. This biochemical mechanism reveals how the bacterial circadian clock has evolved both a compensatory mechanism to assure the robustness of the circadian phase against perturbations and the ability for entrainment by environmental cues, for example abrupt changes in the ambient temperature.

Results

Biochemical properties determine the quantitative KaiABC model

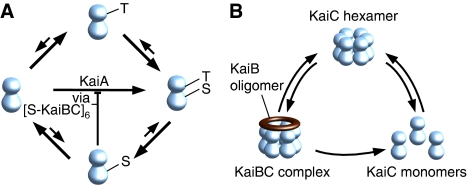

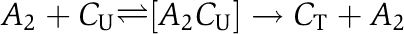

The KaiC proteins form hexamers (Mori et al, 2002), and can autophosphorylate (Nishiwaki et al, 2000) and autodephosphorylate (Xu et al, 2003) at the residues serine 431 (S431) and threonine 432 (T432) (Nishiwaki et al, 2004; Xu et al, 2004). KaiA proteins form stable dimers (Uzumaki et al, 2004; Ye et al, 2004) and enhance autophosphorylation activity of KaiC (Iwasaki et al, 2002), whereas KaiB oligomers attenuate the activity of KaiA (Xu et al, 2003). The circadian rhythm of KaiC phosphorylation is dominated by the subsequent modifications of the two residues S431 and T432 from unphosphorylated (U), threonine phosphorylated (T) to both residues phosphorylated (D), and dephosphorylation through the serine phosphorylated state (S) to the unphosphorylated form (see Figure 1A) (Nishiwaki et al, 2007; Rust et al, 2007). There is strong experimental evidence that the percentage of phosphorylated KaiC is the relevant output signal of the clockwork (Ito et al, 2007). Furthermore, KaiC hexamers show, besides slow phosphorylation dynamics on the hours time scale, a rapid exchange of monomers that has been conjectured to serve as a synchronization mechanism for the individual hexamer phosphorylation levels (Kageyama et al, 2006; Ito et al, 2007; Mori et al, 2007).

Figure 1.

Essential states of the KaiABC system included in our modeling approach. (A) Simplified picture of the major transitions between the four phosphorylation states of the KaiC protein, unphosphorylated (U), serine phosphorylated (S), threonine phosphorylated (T), and both residues phosphorylated (D). Autophosphorylation of KaiC is enhanced by KaiA whose activity is inhibited by only serine phosphorylated KaiBC complexes [S-KaiBC]6. (B) Rapid assembly and disassembly of KaiC hexamers and KaiBC complexes.

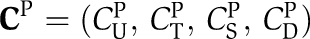

By accounting for these biochemical constraints of KaiABC assembly and phosphorylation, we introduce a quantitative mathematical description of the KaiABC core clock. Oscillatory behavior of a multistate reaction system can be realized in numerous ways by defining molecular interactions that result in at least one negative feedback loop (Novák and Tyson, 2008). In this sense, oversimplified mathematical models are not helpful in elucidating the underlying molecular mechanisms of the KaiABC clock. The experimentally derived detail that KaiA is globally inactivated during the dephosphorylation phase (Rust et al, 2007) implies that the proportions of the KaiC phospho-forms at a given time determine the subsequent phosphorylation dynamics (Ito et al, 2007; Rust et al, 2007). Thus, the in vitro KaiABC clockwork can be described on the circadian time scale by a differential equation that depends exclusively on the actual phospho-form distribution

Here, f(C) denotes the as yet unknown phospho-flux vector that describes the dynamic interplay between the KaiC phospho-forms. C(t) constitutes the phosphorylation state vector, which includes the concentrations of the four KaiC phospho-forms, unphosphorylated (U), threonine residue phosphorylated (T), serine residue phosphorylated (S), and both residues phosphorylated (D) (Figure 1A). These four phospho-forms have to be assigned to three different pools (Figure 1B) giving a 3 × 4-dimensional model. The transition from KaiC hexamers to KaiBC complexes (Figure 1B) requires the binding of KaiB to both serine or double phosphorylated KaiC to arrive at quantitative agreement between model and experimental data. We therefore introduced effective transition rates for both serine and double phosphorylated KaiC to enter KaiBC complexes by cS and cD, respectively. The decay rate of KaiBC complexes is determined by the disassembly rate of KaiC hexamers (see Figure 1B). The decay of KaiC hexamers into KaiC monomers with subsequent reassembly has been observed experimentally (Mori et al, 2007).

In a first step, we used data from the time course experiments of the O'Shea laboratory (Rust et al, 2007) to determine the unknown parameters of the KaiABC in vitro system. First, the transient dynamics of the KaiC phospho-forms in the absence of KaiB was used to identify the phosphorylation and dephosphorylation rates for all KaiC phospho-forms by a least squares fit (Figure 2). The transient behavior of phospho-KaiC with KaiB added at different times (Figure 3) allowed us then to determine the transition kinetics from KaiC hexamers to KaiBC complexes and the inactivation of KaiA by serine phosphorylated KaiC. To this end, we used a global optimization algorithm to scan an orders of magnitude range of parameter values. To ensure that the found optimum is not local, we repeated the parameter search from many different initial conditions. As for each initial condition, the same set of parameters was obtained—up to the default tolerance—we confirmed that the algorithm found a global optimum.

Figure 2.

Phosphorylation dynamics of KaiC in the absence of KaiB. The symbols represent experimental data from Rust et al (2007), and the solid lines result from a least square fit to the mathematical model. Shown are the fraction of the different KaiC phospho-forms, threonine phosphorylated (green upward triangles), serine phosphorylated (red downward triangles), double phosphorylated (violet circles), and the total amount of phosphorylated KaiC (black squares). (A) Autonomous dephosphorylation of KaiC in the absence of KaiA. (B) KaiC phosphorylation in the presence of KaiA.

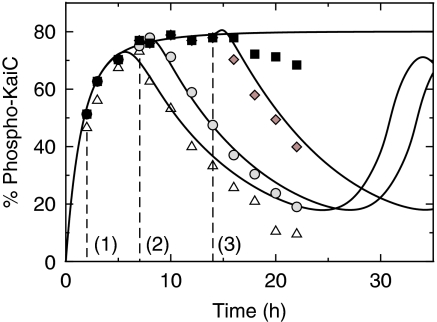

Figure 3.

Transient KaiC phosphorylation dynamics in the presence of KaiA and ATP. Experimental data are taken from Rust et al (2007). KaiB is added at times, 2 h ((1), triangles), 7 h ((2), circles), and 14 h ((3), diamonds) after incubation, indicated by dashed lines. Phosphorylation dynamics in the absence of KaiB is shown by black squares. Solid lines are the corresponding predictions of the mathematical model.

As shown in the Materials and methods section, we reduced the parameters to be identified to the smallest possible amount, whereas retaining the degrees of freedom to achieve a quantitative agreement with the experimental data. After a reduction of the parameter space, three effective binding constants of KaiA to KaiC turned out to be essential, with two of them driving inactivation of KaiA. First, binding of KaiA to all KaiC proteins—regardless of their phosphorylation states—with a sufficiently small dissociation constant KACD is necessary to satisfy dynamic invariance of the phosphorylation dynamics (see Materials and methods section). By dynamic invariance, we refer to the experimentally observed robustess of phase, frequency, and amplitude of the test tube system (Figure 6) on concerted changes of the Kai protein concentrations over one order of magnitude (Kageyama et al, 2006; Rust et al, 2007). Second, the dissociation constant, KASD, quantifies the strength of the negative feedback loop of KaiA inactivation, mediated by serine phosphorylated KaiC. The Michaelis–Menten constant, KiM, associated with the enhanced autophosphorylation of KaiC in phospho-state i, characterizes the third KaiA–KaiC interaction. From the least squares fit to the data, it follows that KaiA increases the autophosphorylation rate from S-KaiC to double phosphorylated KaiC, which is a strong contrast to experiments involving phosphomimetic mutants (Nishiwaki et al, 2007). However, as the corresponding KaiC hexamers of these mutants are all phosphorylated at their serine residues, it is questionable whether the phosphomimetic mutant reflect phosphorylation kinetics of the heterogeneously phosphorylated hexamers.

The response experiment of Figure 3 (Rust et al, 2007) turned out to be crucial for identifying the mechanism by which individual KaiC hexamers can be synchronized in their phosphorylation dynamics. A sudden addition of KaiB 2 h after incubation of KaiC with KaiA and ATP did not lead to an immediate effect on phosphorylation kinetics. Instead, the dephosphorylation phase was entered after a time delay of several hours by an abrupt change from the phosphorylation phase to the dephosphorylation phase. This can only be explained by a strong non-linear dependency of the KaiBC complex formation on the actual phosphorylation state. A simple way to recover this strongly non-linear transient behavior quantitatively is to allow only KaiBC complexes with exclusively serine phosphorylated KaiC, [S-KaiBC]6, to inactivate KaiA with a high efficiency (see Materials and methods).

Simulations and comparison to existing data

To show the quantitative accuracy of the mathematical model, simulations are performed and compared with diverse wet-laboratory experiments beginning with the comprehensive dataset of Rust et al (2007).

The model reproduces accurately the time delay between the addition of KaiB and the initiation of the dephosphorylation phase (Figure 3). As the initial phosphorylation dynamics with and without KaiB is almost identical, KaiA has to be fully active within the first 6–7 h. As shown in Figure 4, this follows from the fact that the abundance of [S-KaiBC]6—promoting KaiA inactivation—is constantly low during the phosphorylation phase. The sudden transition to the dephosphorylation phase with a time delay of several hours after incubation can be explained by the sudden increase of only serine phosphorylated KaiBC complexes (Figure 4) that inactivates KaiA rapidly and thereby stops transitions to higher phosphorylation states, S↛D and T↛D. This mechanism also explains the observed high amplitude of phospho-KaiC oscillations. Alternative models that reproduced the observed high amplitude in phosphorylation kinetics had to introduce additional time scales in the system, for example by defining stable KaiABC complexes throughout the dephosphorylation phase (Mehra et al, 2006; Clodong et al, 2007; Mori et al, 2007; van Zon et al, 2007). However, as shown by Rust et al, the dynamics of the KaiABC clock is set by its phospho-form distribution, and contributions from additional long-lived states have not been observed.

Figure 4.

Oscillations in the abundance of only serine phosphorylated KaiBC complexes, [S-KaiBC]6, (red line), in comparison to the phosphorylation dynamics of total phospho-KaiC (black line).

Although we have not used any direct constraints to arrive at the characteristic shape of the oscillations in phospho-KaiC, we find excellent agreement between model predictions and the experimentally found dynamic behavior (Figure 5). Besides reproduction of the correct peak-to-peak time distances of the four phospho-forms, we also recovered the asymmetry of the amplitude peak of phospho-KaiC, resulting in phosphorylation and dephosphorylation phases of ∼9.5 and 18.5 h, respectively. Here, the in vitro experiments of Rust et al showed a period of 28 h, whereas other in vitro experiments recover the circadian 24 h rhythm (Ito et al, 2007). In our model, the different periods can be adjusted by changing the transition rates to KaiBC complexes, cS and cD (see Supplementary information).

Figure 5.

Oscillations of the KaiC phospho-forms, threonine phosphorylated (green upward triangles), serine phosphorylated (red downward triangles), double phosphorylated (violet circles), and the total amount of phosphorylated KaiC (black squares). The different durations of the phosphorylation phase (τ1≈9.5 h) and dephosphorylation phase (τ2≈18.5 h) lead to an asymmetric position of the peak maximum. (A) Experimental data taken from Rust et al (2007). (B) Corresponding phosphorylation dynamics are from the mathematical model.

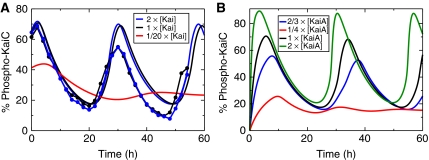

Our mathematical model also reproduces the observed dynamic invariance of KaiC phosphorylation under concerted changes of all Kai proteins (Figure 6A). The necessary requirement, Equation (5), is met by demanding a constant amount of free diffusible KaiA under concerted KaiABC concentration changes and the monomer pool to be sufficiently small. To this end, the maximum amount of free KaiA has been limited to 15% of its total concentration, A2tot, by adjusting the associated KaiA–KaiC binding constant, KACD. In agreement with experiments (Kageyama et al, 2006), a concerted 10-fold decrease in the concentration of KaiABC proteins violates dynamic invariance, as on dilution of the sequestration substrate KaiC, the amount of free KaiA is not constant any more (see Materials and methods Equation (16)).

Figure 6.

Behavior of KaiC phosphorylation dynamics against concentration changes of all Kai proteins. (A) Dynamic invariance of phospho-KaiC against a two-fold concentration change of all proteins as measured by Rust et al (2007) (filled circles), and the predictions of the mathematical model (solid lines). Loss of oscillatory behavior is found after a 20-fold decrease in Kai concentrations. (B) Sensitivity of KaiC phosphorylation dynamics against changes in KaiA concentrations as predicted from our mathematical model with KaiB and KaiC kept at their standard values.

Mass spectrometry validation

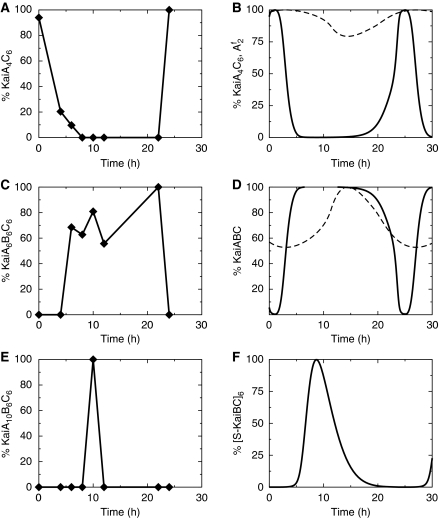

Our theoretical predictions are confirmed by native mass spectrometry (Heck, 2008), generating semi-quantitative time courses of the KaiABC complex formation dynamics (see Materials and methods). Native mass spectrometry is a novel, highly sensitive method to resolve the stoichiometry of large protein complexes. Our experiments show the existence of a significant amount of both free KaiC hexamers (KaiC6) and KaiA2C6 complexes at every stage of the circadian cycle, with the observed signal for KaiA2C6 only exceeding that for KaiC6 in the initial phosphorylation phase (see Supplementary Figure S2). We interpret the constant sequestration of free KaiA by the KaiA2C6 complexes as the molecular realization of the dynamic invariance condition that requires most of the KaiA to be inactive at every instant of time, regardless of the phosphorylation state. As theoretically predicted, the experiments indicate the existence of two different binding sites for KaiA dimers on a KaiC hexamer, which is supported by both the observation of KaiA4C6 complexes and the absence of higher order complexes, KaiA2nC6, with n>2. The second binding site would then reflect the KaiA-binding domain at the catalytic active center of the KaiC hexamer. Thus, the concentration relation of the low abundance complex KaiA4C6 to the total amount of KaiC estimates the relative enhancement of the KaiC autophosphorylation activity. This hypothesis is confirmed by comparison of the mass spectrometry signal for KaiA4C6 with predictions from the mathematical model (Figure 7A and B). In the late phosphorylation phase, KaiBC complexes rapidly start to build up and lead to sequestration of KaiA (Figure 7C). Transient KaiABC complexes involving KaiB2C6 and KaiB4C6 are observed (data not shown) but only KaiB6C6 remains present throughout the whole dephosphorylation phase. Comparison of Figure 7C with A shows that the amount of KaiA bound with low affinity to the active center, KaiA4C6, decreases abruptly if the amount KaiA6B6C6 raises, thereby confirming the sequestration hypotheses. The time of maximum sequestration—as defined by the appearance of the largest observed sequestration complex KaiA10B6C6 (Figure 7E)—agrees with the theoretical expected sequestration maximum (Figure 7F), where [S-KaiBC]6 is maximal. We speculate that a hexameric KaiBC complex can sequester up to six KaiA dimers. The abrupt inactivation of KaiA supports our hypothesis that a non-linear sequestration mechanism is the key driving force of the KaiABC circadian clock.

Figure 7.

Trends of KaiABC complex formation over a circadian period derived from semi-quantitative native mass spectrometry measurements (left panels) in comparison with theoretical predictions (right panels, solid lines). The abundances of complexes are drawn relative to their maxima within the circadian cycle. (A, B) The phosphorylation phase is determined by the occupancy of the catalytic active site of KaiC hexamers with KaiA as measured by the abundance of KaiA4C6, which scales linearly with the amount of freely diffusible KaiA dimers, A2f. (C, D) The dephosphorylation phase is determined by KaiA sequestration due to KaiABC complexes. (E) Time of the KaiA sequestration maximum as indicated by the complex of highest mass, KaiA10B6C6. (F) Theoretical prediction of the KaiA sequestration maximum by the peak position of [S-KaiBC]6 at ∼9.5 h. (A, C, E) The fractional abundance of complexes relates to the relative mass spectrometry signal. In the alternative model (Rust et al, 2007), the amount of free KaiA and of sequestrated KaiA depends on the concentration of S-KaiC (dashed line). Source data is available for this figure at www.nature.com/msb.

Temperature compensation and entrainment

A fundamental characteristic of circadian clocks is their anticipation to cyclic changes in the environment such as light or temperature. That even the in vitro KaiABC clockwork adapts to environmental cues has been shown by entrainment of the KaiC phosphorylation kinetics by temperature cycles (Yoshida et al, 2009). Here, the response to a sudden temperature change results in a phase shift of phospho-KaiC, whereas the circadian period does not show any temperature dependency within a physiologically relevant range.

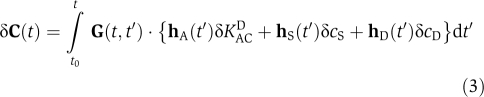

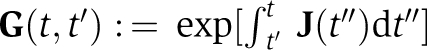

As phosphorylation and dephosphorylation dynamics of KaiC alone and incubated with KaiA do not show significant temperature dependence (Tomita et al, 2005), phase entrainment is likely a consequence of temperature-induced changes in binding constants associated with the various KaiABC complexes. From thermodynamic arguments, we expect that an increasing temperature will enhance dissociation of KaiA and KaiB from KaiC. Indeed, a reduction in the net complex formation rate for KaiBC and KaiAC on temperature increase results in the experimentally observed differences in phase response (Figure 8A). Here, a sudden temperature increase at the end of the phosphorylation phase leads to a negative phase shift, whereas a temperature increase within the dephosphorylation phase leads to a positive phase shift, as shown by the corresponding phase response curve for positive temperature steps (Figure 8C). This difference leads to phase synchronization of the circadian oscillations that agree excellently with the experimental observations (Yoshida et al, 2009), where the maximum KaiC phosphorylation level aligns with the end of the high-temperature phase (Figure 9). To understand the underlying molecular mechanisms in detail, we expand the time evolution equation of the KaiC phospho-form distribution, Equation (1), to first order in changes in effective binding constants for KaiBC and KaiAC complexes

Here, δC(t), denotes the resulting change of KaiC phosphorylation states on a temperature-mediated change in the effective KaiA sequestration constant, δKACD, and a change in the rates to enter KaiBC complexes, δcS and δcD, of serine and double phosphorylated KaiC, respectively (see Materials and methods). The corresponding time-dependent expansion coefficients result in the Jacobi matrix J(t) and the flux vectors hA(t), hS(t), and hD(t). The formal solution of Equation (2) is given by

|

with t0 as the time when the temperature step has occurred. In Equation (3), effects of changes in δKACD, δcS, and δcD at time t′ on the current deviation in phospho-form distribution, δC(t), are determined by the time-ordered matrix propagator  . If temperature changes would affect only one of the three rate constants, then a change in period would be the consequence, as the time integral in Equation (3) shifts the phase by the same distance for any subsequent circadian cycle. For example, a temperature-induced reduction in the amount of only serine phosphorylated KaiBC complexes, δcS<0, shortens the dephosphorylation phase as KaiA inactivation terminates earlier and thereby reduces the circadian period (see Figure 8A). As the circadian period is an invariant system property within the range of physiological temperatures, Equation (3) must satisfy the relation δC(t1)=δC(t1+nTC) for all cycles n∈{1,2,…}, where t1 denotes the time when the resulting transients from a temperature change have declined and TC denotes the circadian period. This relation demands that on temperature increase, the shortened circadian period, resulting from both dissociation of KaiA from KaiC, δKACD>0, and from the reduction in serine phosphorylated KaiBC complexes, δcS<0, must be precisely compensated by the prolonged circadian period, resulting from a reduction of double phosphorylated KaiBC complexes, δcD<0. The prolonged phase can be explained by the fact that KaiBC complexes can only dephosphorylate and a reduced transition to double phosphorylated KaiBC complexes results in a reduced amount of only serine phosphorylated KaiC and thus transition to the dephosphorylation phase is delayed. It is interesting to see that the rate cD that had to be introduced in our mathematical model (see Materials and methods) to arrive at a quantitative description of the experimental data now turns out to be essential to explain the observed temperature independence of the circadian period. We emphasize that the temperature dependence of the three rates, KACD, cS, and cD are fixed by the experimentally determined maximum and minimum phase shifts and the temperature invariance of the period. The excellent agreement of the theoretically predicted phosphorylation dynamics (Figure 8B) is therefore an inherent property of the mathematical model. Thus, the temperature compensation of the KaiABC circadian clock follows one of the earliest proposed mechanisms—the cancellation of opposing effects on the circadian period (Hastings and Sweeney, 1957).

. If temperature changes would affect only one of the three rate constants, then a change in period would be the consequence, as the time integral in Equation (3) shifts the phase by the same distance for any subsequent circadian cycle. For example, a temperature-induced reduction in the amount of only serine phosphorylated KaiBC complexes, δcS<0, shortens the dephosphorylation phase as KaiA inactivation terminates earlier and thereby reduces the circadian period (see Figure 8A). As the circadian period is an invariant system property within the range of physiological temperatures, Equation (3) must satisfy the relation δC(t1)=δC(t1+nTC) for all cycles n∈{1,2,…}, where t1 denotes the time when the resulting transients from a temperature change have declined and TC denotes the circadian period. This relation demands that on temperature increase, the shortened circadian period, resulting from both dissociation of KaiA from KaiC, δKACD>0, and from the reduction in serine phosphorylated KaiBC complexes, δcS<0, must be precisely compensated by the prolonged circadian period, resulting from a reduction of double phosphorylated KaiBC complexes, δcD<0. The prolonged phase can be explained by the fact that KaiBC complexes can only dephosphorylate and a reduced transition to double phosphorylated KaiBC complexes results in a reduced amount of only serine phosphorylated KaiC and thus transition to the dephosphorylation phase is delayed. It is interesting to see that the rate cD that had to be introduced in our mathematical model (see Materials and methods) to arrive at a quantitative description of the experimental data now turns out to be essential to explain the observed temperature independence of the circadian period. We emphasize that the temperature dependence of the three rates, KACD, cS, and cD are fixed by the experimentally determined maximum and minimum phase shifts and the temperature invariance of the period. The excellent agreement of the theoretically predicted phosphorylation dynamics (Figure 8B) is therefore an inherent property of the mathematical model. Thus, the temperature compensation of the KaiABC circadian clock follows one of the earliest proposed mechanisms—the cancellation of opposing effects on the circadian period (Hastings and Sweeney, 1957).

Figure 8.

Phase shift of the KaiC phosphorylation dynamics after a sudden temperature increase from 30 to 45°C within the dephosphorylation phase as indicated by the dashed line. (A) Experimental data (Yoshida et al, 2009) for 30°C (black line) and 45°C (red line). (B) Corresponding phosphorylation dynamics of panel (A) as predicted by the mathematical model. (C) Theoretically predicted phase response curve, calculated from phase shifts in the peak maxima for a 28-h period. The peaks of phospho-KaiC can be found on the circadian time scale at 18.5 h for a 28-h period (Rust et al, 2007) and 16 h for a 24-h period (Yoshida et al, 2009).

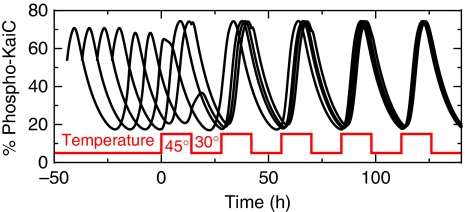

Figure 9.

Phase synchronization dynamics of the KaiC phosphorylation level due to rhythmic temperature changes given by 12 h phases of low temperature (30°C) and high temperature (45°C), respectively. Shown are the trajectories as predicted by the mathematical model for four different initial phases.

Strikingly, the rapid phase shift observed in experiments and theory around the circadian time 19 h (Figure 8C) has the same origin as the sudden switching from the phosphorylation phase to the dephosphorylation phase after KaiB addition (Figure 3). In both cases, the non-linear feedback of KaiA inactivation results in an all-or-none behavior that in our model is attributed to only serine phosphorylated KaiBC complexes. Thus, the existence of a non-linear feedback follows also from Figure 8A and B, where a sudden temperature increase leads to an abrupt change in phosphorylation dynamics after a time delay of several hours.

Discussion

Mathematical modeling of interacting protein networks suffers from the huge space of potential molecular states and interaction mechanisms. It is therefore necessary to include experimental data in the modeling process that put the most stringent constraints on a set of plausible reaction networks such as transient behavior and dynamic invariant systems properties. In case of the in vitro KaiABC system of S. elongatus, the invariance of the KaiC phosphorylation dynamics under order of magnitude concentration changes is such a systems property that strongly narrows the set of potential reactions among the Kai proteins. Another important constraint is the absence of any additional long-lived states on the hours time scale besides the phospho-form distribution. As a consequence, the observed sudden transition into the dephosphorylation phase (Figure 3), resulting from global KaiA inactivation, must be driven by a highly non-linear dependency on the gradually changing phospho-form distribution (Figure 2). In our modeling approach, we attributed this non-linearity to the abundance of only serine phosphorylated KaiBC complexes in the system. So far, we have provided very strong evidence for the existence of a highly non-linear feedback mechanism by reproducing the phosphorylation dynamics of Figures 3 and 8 and the KaiABC complex formation dynamics, Figure 7, as measured by native mass spectrometry. A possible molecular realization of this sequestration mechanism can be seen in the strong KaiA binding affinity to KaiB6C6. This complex formation in turn is strongly enhanced for the [S-KaiBC]6 phosphorylation state.

The occurrence of the largest complex, KaiA10B6C6, in native mass spectra at ∼10 h fits perfectly to the time of maximum of KaiA sequestration as predicted by the model (Figure 7). Further, the existence and dynamics of KaiA2C6 and KaiA4C6 complexes supports the prediction of two different binding sites for KaiA dimers on an KaiC hexamer providing a site for constant KaiA sequestration and another site for catalytic binding.

However, the realization of KaiA sequestration by only serine phosphorylated hexamers lacks direct experimental confirmation. Therefore, alternative non-linear mechanisms of KaiABC complex formation cannot be ruled out at this stage, but these mechanisms are strongly constrained by the dynamic invariance of phospho-KaiC against concerted changes in all Kai proteins. A possible reason for a strong non-linearity in the KaiABC system to have evolved can be a sufficiently fast adaptation of the phase to external cues and to changes in phospho-form distribution, resulting from protein synthesis and decay. A further reason can be seen in the very high observed amplitude of phospho-KaiC oscillations that might require a non-linear feedback mechanism. The quantitative agreement of the mathematical model with the measured phosphorylation dynamics allowed us to propose a molecular mechanism responsible for temperature entrainment based on changes in binding constants of KaiAC and KaiBC complexes. We thereby showed that the entrainment of the KaiABC clock by experimentally observed phase shifts on sudden temperature changes (Yoshida et al, 2009) is a consequence of temperature dependencies in the reaction parameters.

Putting our results together, we have shown that the circadian core clock of cyanobacteria shows an outstanding design for the precision in phase and period in the presence of intracellular and extracellular perturbations. This confirms the hypothesis that circadian oscillators of phototrophic organisms have evolved to average over randomly fluctuating zeitgeber signals—like light or temperature—to coordinate their metabolic activity, according to the expected duration of night and day.

In cyanobacteria, the KaiABC phosphorylation oscillator works in concert with the circadian changes in the synthesis rate of KaiB and KaiC proteins. Circadian oscillation of the genome-wide expression level persisted even when KaiC was arrested in a highly phosphorylated state (Kitayama et al, 2008). Thus, the KaiABC clockwork investigated here is part of a larger clockwork system and does not operate completely autonomously in vivo. From this viewpoint, it is even more surprising to see that the in vitro KaiABC oscillator is already a highly robust module, compensating for temperature fluctuations and concerted changes in protein concentrations but allowing entrainment by temperature cycles.

Materials and methods

Computational methods

To find the missing molecular mechanisms that will eventually allow for a quantitative description of the in vitro KaiABC clock, we have to narrow the large space of hypothetical interactions of the Kai proteins. As for any dynamical system, the most natural way to identify all intrinsic time scales is by studying the transient behavior from well-defined initial states, as has been done extensively for the KaiABC system (Kageyama et al, 2006; Rust et al, 2007). However, additional mechanistic constraints on a reaction system can be obtained by identifying systems properties that are invariant under orders of magnitude changes in one or more systems parameters. The unchanged oscillatory KaiC phosphorylation dynamics under concerted elevation of all Kai protein concentrations is such an invariant systems property and its associated molecular constraints will be investigated in the following section.

Dynamic invariance

We first denote by Atot and Btot the total wild-type concentrations of KaiA and KaiB, respectively. The KaiC concentrations of the four phospho-forms, unphosphorylated (U), threonine residue phosphorylated (T), serine residue phosphorylated (S), both residues phosphorylated (D), constitute the phosphorylation state vector, C, with elements Ci. We use in the following the symbols of the corresponding phospho-forms as indices, i∈{U,T,S,D}, for clarity. The time evolution equations for the KaiC phospho-form concentration are determined in the limit of high protein copy numbers by the differential equation

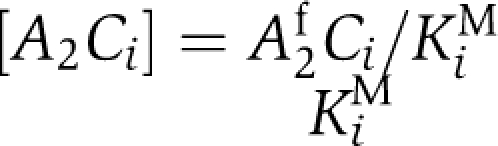

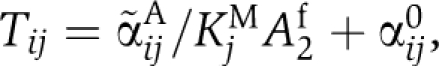

Here, T is the transition matrix whose elements Tij contain the net transition rates from the KaiC phosphorylation state j to i, with i, j∈{U,T,S,D}. The experimentally observed dynamic invariance (Kageyama et al, 2006; Rust et al, 2007) of the relative KaiC phosphorylation levels, ci(t):=Ci(t)/Ctot, with  as the total KaiC concentration, demands that the transition rates Tij are invariant under a λ-fold change in total protein concentrations

as the total KaiC concentration, demands that the transition rates Tij are invariant under a λ-fold change in total protein concentrations

This scaling relation results from the fact that dynamic invariance of the physiologically relevant quantity ci requires the transformation Ci(t) → λCi(t) to arrive at the relation ci(t) → λCi(t)/(λCtot)=ci(t). Experiments suggest that enhanced KaiC phosphorylation is the result of a bimolecular reaction with KaiA dimers, for example  (Rust et al, 2007). The experimental fact that KaiA frequently binds and unbinds on the hours time scale (Kageyama et al, 2006) allows KaiAC complexes,

(Rust et al, 2007). The experimental fact that KaiA frequently binds and unbinds on the hours time scale (Kageyama et al, 2006) allows KaiAC complexes,  to be resolved by introducing the Michaelis–Menten constants KiM. In the absence of KaiB, we obtain

to be resolved by introducing the Michaelis–Menten constants KiM. In the absence of KaiB, we obtain  where KaiC in state i carries one phospho-group more than KaiC in state j. Here, αij0 represents a constant autophosphorylation rate and

where KaiC in state i carries one phospho-group more than KaiC in state j. Here, αij0 represents a constant autophosphorylation rate and  the rate of KaiC phosphorylation by KaiA. From Equations (4 and 5), it follows that the concentration of active and free diffusible KaiA dimers, A2f, has to be independent of the concentration-scaling factor, λ. A simple mechanism to arrive at a λ-independent expression for A2f is given by strong sequestration of KaiA by KaiC regardless of its phosphorylation state,

the rate of KaiC phosphorylation by KaiA. From Equations (4 and 5), it follows that the concentration of active and free diffusible KaiA dimers, A2f, has to be independent of the concentration-scaling factor, λ. A simple mechanism to arrive at a λ-independent expression for A2f is given by strong sequestration of KaiA by KaiC regardless of its phosphorylation state,  (Clodong et al, 2007; Rust et al, 2007; van Zon et al, 2007). Invariance of A2f arises if the dissociation constant KACD is sufficiently small as both A2tot and Ci scale with the factor λ on a concerted change in protein concentration. Further, it has been shown experimentally that a moderate change in the total concentration of KaiB around its native value does not change the phophorylation dynamics (Kageyama et al, 2006; Clodong et al, 2007). This is an indication that KaiC hexamers being able to bind KaiB oligomers are always saturated with KaiB throughout the circadian cycle. Therefore, any concerted change of total KaiB and KaiC in system does not alter the fraction of KaiBC complexes and invariance of ci is preserved.

(Clodong et al, 2007; Rust et al, 2007; van Zon et al, 2007). Invariance of A2f arises if the dissociation constant KACD is sufficiently small as both A2tot and Ci scale with the factor λ on a concerted change in protein concentration. Further, it has been shown experimentally that a moderate change in the total concentration of KaiB around its native value does not change the phophorylation dynamics (Kageyama et al, 2006; Clodong et al, 2007). This is an indication that KaiC hexamers being able to bind KaiB oligomers are always saturated with KaiB throughout the circadian cycle. Therefore, any concerted change of total KaiB and KaiC in system does not alter the fraction of KaiBC complexes and invariance of ci is preserved.

So far, the experimentally observed formation of KaiC hexamers and KaiBC complexes have been ignored in our considerations. In the following we denote by H(n) the concentration of hexamers with phospho-form distribution characterized by the occupation vector  . Here, ni is the number of KaiC monomers that occupy phosphorylation state i, under the constraint

. Here, ni is the number of KaiC monomers that occupy phosphorylation state i, under the constraint  . Invariance of the KaiC phosphorylation dynamics on total protein abundance also puts severe constraints on the molecular mechanism for the experimentally observed KaiC monomer exchange among hexamers if we imply that monomer exchange affects phosphorylation dynamics. Assuming bimolecular interactions between KaiC hexamers to be responsible for monomer exchange, the scaling relation Equation (5) is violated, as exchange rates scale with the encounter probability of exchange partners. However, violation of the dynamic invariance can be avoided if bimolecular monomer exchange equilibrates fast in comparison to phosphorylation dynamics

. Invariance of the KaiC phosphorylation dynamics on total protein abundance also puts severe constraints on the molecular mechanism for the experimentally observed KaiC monomer exchange among hexamers if we imply that monomer exchange affects phosphorylation dynamics. Assuming bimolecular interactions between KaiC hexamers to be responsible for monomer exchange, the scaling relation Equation (5) is violated, as exchange rates scale with the encounter probability of exchange partners. However, violation of the dynamic invariance can be avoided if bimolecular monomer exchange equilibrates fast in comparison to phosphorylation dynamics  . As a consequence monomer fluxes are balanced at every instant of time,

. As a consequence monomer fluxes are balanced at every instant of time,

with forward and backward exchange rates given by  and

and  and hexamer state vectors before and after the monomer exchange given by

and hexamer state vectors before and after the monomer exchange given by  , and

, and  , respectively. As both sides of this equation share the same dependence on the concentration-scaling factor,

, respectively. As both sides of this equation share the same dependence on the concentration-scaling factor,  , the factor λ cancels and thereby conserves dynamic invariance.

, the factor λ cancels and thereby conserves dynamic invariance.

Indeed, monomer shuffling has been observed in experiments at all phosphorylation stages (Mori et al, 2007), with significantly enhanced exchange rates during the dephosphorylation phase. However, the observed autocorrelation time of ∼2 h cannot be considered as infinitely fast and therefore brings into question a monomer exchange based on rapid hexamer–hexamer interaction. Also, complexes involving two or more hexamers have not been observed in experiments so far (Clodong et al, 2007). Another scenario of monomer exchange is given by the experimentally measured small amount of free monomers (Clodong et al, 2007; Mori et al, 2007) that is likely a consequence of hexamer decay and reassembly. As the amount of KaiC forming the free monomer pool, CtotP, is small compared with the total amount of KaiC, Ctot, we have the relation  throughout the circadian cycle. This relation is a simple consequence of the fact that the flux balance between KaiC assembly and disassembly is strongly biased toward the hexameric state, CtotH∼1/6Ctot. Note that the existence of monomeric KaiC adds a synthesis and a decay term to the time evolution of KaiC phospho-forms in hexamers, Equation (4). As the reaction flux of diffusion limited assembly of hexamers scales to first order with (CtotP)6 and that of hexamer decay with the concentration of hexamers, CtotH, the resulting monomer exchange does not violate dynamic invariance as both fluxes scale linearly with the concentration factor λ. Note that the elimination of higher order concentration dependencies in reaction networks by saturated binding of reaction partners or strong time scale separations are very generic concepts to conserve dynamic invariance of the network output.

throughout the circadian cycle. This relation is a simple consequence of the fact that the flux balance between KaiC assembly and disassembly is strongly biased toward the hexameric state, CtotH∼1/6Ctot. Note that the existence of monomeric KaiC adds a synthesis and a decay term to the time evolution of KaiC phospho-forms in hexamers, Equation (4). As the reaction flux of diffusion limited assembly of hexamers scales to first order with (CtotP)6 and that of hexamer decay with the concentration of hexamers, CtotH, the resulting monomer exchange does not violate dynamic invariance as both fluxes scale linearly with the concentration factor λ. Note that the elimination of higher order concentration dependencies in reaction networks by saturated binding of reaction partners or strong time scale separations are very generic concepts to conserve dynamic invariance of the network output.

Quantitative mathematical model of the Kai system

The phosphorylation dynamics are characterized by the monomer concentration vectors of KaiBC complexes,  , free hexamers,

, free hexamers,  , and a small pool of KaiC monomers,

, and a small pool of KaiC monomers,  . Within our mathematical model, Equations (7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13), we allow only hexamers with either all KaiC serine phosphorylated, all double phosphorylated or all unphosphorylated to undergo the transition between KaiC hexamers and KaiBC complexes with rates cS, cD and cU, respectively. This strong simplification is possible as the phospho-form composition of KaiC hexamers is given by a multinomial distribution at every instant of time, assuming undirected monomer exchange. Any information about the allowed hexameric states involved in the transition to KaiBC complexes is therefore immediately lost. From the above assumptions and constraints, we can set up effective rate equations for the phosphorylation and complex formation dynamics given by

. Within our mathematical model, Equations (7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13), we allow only hexamers with either all KaiC serine phosphorylated, all double phosphorylated or all unphosphorylated to undergo the transition between KaiC hexamers and KaiBC complexes with rates cS, cD and cU, respectively. This strong simplification is possible as the phospho-form composition of KaiC hexamers is given by a multinomial distribution at every instant of time, assuming undirected monomer exchange. Any information about the allowed hexameric states involved in the transition to KaiBC complexes is therefore immediately lost. From the above assumptions and constraints, we can set up effective rate equations for the phosphorylation and complex formation dynamics given by

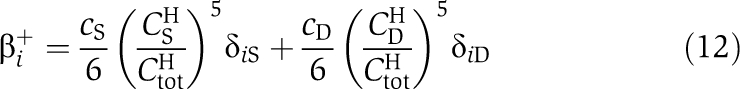

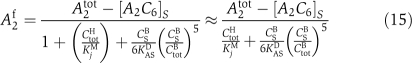

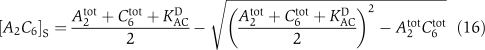

Here, β+ and β− are the binding rates and dissociation rates of KaiB to KaiC hexamers. The transition matrices TH and TB include the hexamer decay rate, γ−, to the free monomer pool, CP. Assembly of monomers to hexamers increases the concentrations of CH with rate γ+CP. The transition rates of Equations (7, 8, 9) are then given by

|

|

|

|

|

|

Here, αij0 are the basal transition rates between the four phosphorylation states of KaiC. KaiA enhances phosphorylation of KaiC from state j to state i with rate  . We denoted by δij the Kronecker δ. The total concentration of the KaiC monomer pool is given by

. We denoted by δij the Kronecker δ. The total concentration of the KaiC monomer pool is given by  and has been fixed to an amount of 5% Ctot. The hexamer assembly is characterized by the Michaelis–Menten constant KP.

and has been fixed to an amount of 5% Ctot. The hexamer assembly is characterized by the Michaelis–Menten constant KP.

Experimental methods

Purification of recombinant Kai proteins

The recombinant Kai proteins from S. elongatus PCC 7942 were produced in Escherichia coli BL21 strains kindly provided by T Kondo (Nagoya University, Japan). The recombinant GST fusion proteins KaiA, KaiB, KaiC were purified using Glutathione Sepharose and PreScission Protease (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) as described (Iwasaki et al, 2002; Nishiwaki et al, 2004). Cleaved Kai proteins were further purified using a Resource Q anion exchange chromatography. Protein concentrations were estimated according to Lowry et al (1951), as well as by a visual comparison of the different protein amounts on Coomassie-stained SDS-gels.

In vitro KaiC phosphorylation assay

The reconstitution of KaiC phosphorylation cycle in vitro was performed as described (Nakajima et al, 2005).

Analysis of Kai-complex distribution by native mass spectrometry

For native MS analysis, 0.1 μg μl−1 KaiA, 0.05 μg μl−1 KaiB, and 0.2 μg μl−1 KaiC were incubated in 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ATP buffer for different time intervals between 0 and 24 h. Before the analysis, the reaction buffer was exchanged for MS-compatible buffer (100 mM CH3COONH4, pH 7.0) by spin dilution/concentration using 5 kDa MWCO spin filter columns (Millipore) at 4°C.

Samples were loaded into gold-plated borosilicate capillaries (made in-house) for analysis by nano-electrospray ionization MS. Mass spectra were acquired over an m/z range of 500–20 000 on an LCT 1 MS (Waters Corp.) with enhanced pressure in the source region to allow improved transmission of non-covalent complexes (van den Heuvel et al, 2006).

Masses of the different species present were determined from series of m/z peaks, to allow identification of the complexes present at each time point. Mass calibration was performed using CsI clusters. The fraction of total peak area related to each complex was used to estimate the relative increase or decrease of population of the different species at different time points (Rose et al, 2008). For each complex, these data were normalized to the maximum fraction peak area observed.

Supplementary Material

This is a matlab archive with the model of the oscillator in a machine-readable format.

The document with detailed explanations.

Acknowledgments

We thank Pål O Westermark and Hanspeter Herzel for careful reading of the manuscript. This work was financially supported by the Emmy Noether-Progamm, K0 3442/1-1 (to MK), the Netherlands Proteomics Centre (to RR and AH), the European Commission, FP7-ICT-2009-4, BACTOCOM, Project Number 248919, the BMBF, FORSYSPartner Project, Grant 0315294 (to SH and IMA) and by the Collaborative Research Center (SFB 618). We are also thankful to the O'Shea laboratory for providing the raw data.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Clodong S, Dühring U, Kronk L, Wilde A, Axmann I, Herzel H, Kollmann M (2007) Functioning and robustness of a bacterial circadian clock. Mol Syst Biol 3: 90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emberly E, Wingreen NS (2006) Hourglass model for a protein-based circadian oscillator. Phys Rev Lett 96: 038303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heck AJR (2008) Native mass spectrometry: a bridge between interactomics and structural biology. Nat Methods 5: 927–933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings JW, Sweeney BM (1957) On the mechanism of temperature independence in a biological clock. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 43: 804–811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiura M, Kutsuna S, Aoki S, Iwasaki H, Andersson CR, Tanabe A, Golden SS, Johnson CH, Kondo T (1998) Expression of a gene cluster KaiABC as a circadian feedback process in cyanobacteria. Science 281: 1519–1523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito H, Kageyama H, Mutsuda M, Nakajima M, Oyama T, Kondo T (2007) Autonomous synchronization of the circadian KaiC phosphorylation rhythm. Nat Struct Mol Biol 14: 1084–1088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki H, Nishiwaki T, Kitayama Y, Nakajima M, Kondo T (2002) KaiA-stimulated KaiC phosphorylation in circadian timing loops in cyanobacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 15788–15793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kageyama H, Nishiwaki T, Nakajima M, Iwasaki H, Oyama T, Kondo T (2006) Cyanobacterial circadian pacemaker: Kai protein complex dynamics in the KaiC phosphorylation cycle in vitro. Mol Cell 23: 161–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama Y, Nishiwaki T, Terauchi K, Kondo T (2008) Dual KaiC-based oscillations constitute the circadian system of cyanobacteria. Genes Dev 22: 1513–1521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ (1951) Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem 193: 265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehra A, Hong CI, Shi M, Loros JJ, Dunlap JC, Ruoff P (2006) Circadian rhythmicity by autocatalysis. PLoS Comput Biol 2: e96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihalcescu I, Hsing W, Leibler L (2004) Resilient circadian oscillator revealed in individual cyanobacteria. Nature 430: 81–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori T, Saveliev SV, Xu Y, Stafford WF, Cox MM, Inman RB, Johnson CH (2002) Circadian clock protein KaiC forms ATP-dependent hexameric rings and binds DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 17203–17208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori T, Williams DR, Byrne MO, Qin X, Egli M, Mchaourab HS, Stewart PL, Johnson CH (2007) Elucidating the ticking of an in vitro circadian clockwork. PLoS Biol 5: 4e93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima M, Imai K, Ito H, Nishiwaki T, Murayama Y, Iwasaki H, Oyama T, Kondo T (2005) Reconstitution of circadian oscillation of cyanobacterial KaiC phosphorylation in vitro. Science 308: 414–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiwaki T, Iwasaki H, Ishiura M, Kondo T (2000) Nucleotide binding and autophosphorylation of the clock protein KaiC as a circadian timing process of cyanobacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 495–499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiwaki T, Satomi Y, Nakajima M, Lee C, Kiyohara R, Kageyama H, Kitayama Y, Temamoto M, Yamaguchi A, Hijikata A, Go M, Iwasaki H, Takao T, Kondo T (2004) Role of KaiC phosphorylation in the circadian clock system of synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 13927–13932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiwaki T, Satomi Y, Kitayama Y, Terauchi K, Kiyohara R, Takao T, Kondo T (2007) A sequential program of dual phosphorylation of KaiC as a basis for circadian rhythm in cyanobacteria. EMBO J 26: 4029–4037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novák B, Tyson JJ (2008) Design principles of biochemical oscillators. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 9: 981–991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose RJ, Verger D, Daviter T, Remaut H, Paci E, Waksman G, Ashcroft AE, Radford SE (2008) Unraveling the molecular basis of subunit specificity in P pilus assembly by mass spectrometry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 12873–12878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rust MJ, Markson JS, Lane WS, Fisher DS, O'Shea EK (2007) Ordered phosphorylation governs oscillation of a three-protein circadian clock. Science 318: 809–812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita J, Nakajima M, Kondo T, Iwasaki H (2005) No transcription-translation feedback in circadian rhythm of KaiC phosphorylation. Science 307: 251–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzumaki T, Fujita M, Nakatsu T, Hayashi F, Shibata H, Itoh N, Kato H, Ishiura M (2004) Crystal structure of the c-terminal clock-oscillator domain of the cyanobacterial KaiA protein. Nat Struct Mol Biol 11: 623–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Heuvel RH, van Duijn E, Mazon H, Synowsky SA, Lorenzen K, Versluis C, Brouns SJ, Langridge D, van der Oost J, Hoyes J, Heck AJ (2006) Improving the performance of a quadrupole time-of-flight instrument for macromolecular mass spectrometry. Anal Chem 78: 7473–7483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Zon JS, Lubensky DK, Altena PRH, Rein ten Wolde P (2007) An allosteric model of circadian KaiC phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 7420–7425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Mori T, Johnson CH (2003) Cyanobacterial circadian clockwork: roles of KaiA, KaiB and the KaiBC promoter in regulating KaiC. EMBO J 22: 2117–2126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Mori T, Pattanayek R, Pattanayek S, Egli M, Johnson CH (2004) Identification of key phosphorylation sites in the circadian clock protein KaiC by crystallographic and mutagenetic analyses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 13933–13938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye S, Vakonakis I, Ioerger TR, LiWang AC, Sacchettini JC (2004) Crystal structure of circadian clock protein KaiA from synechococcus elongatus. J Biol Chem 279: 20511–20518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoda M, Eguchi K, Terada TP, Sasai M (2007) Monomer-shuffling and allosteric transition in KaiC circadian oscillation. PLoS ONE 2: e408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida T, Murayama Y, Ito H, Kageyama H, Kondo T (2009) Nonparametric entrainment of the in vitro circadian phosphorylation rhythm of cyanobacterial KaiC by temperature cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 1648–1653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

This is a matlab archive with the model of the oscillator in a machine-readable format.

The document with detailed explanations.