Abstract

The objective of this study was to determine the brain stem nuclei and physiological responses activated by esophageal acidification. The effects of perfusion of the cervical (ESOc), or thoracic (ESOt) esophagus with PBS or HCl on c-fos immunoreactivity of the brain stem or on physiological variables, and the effects of vagotomy were examined in anesthetized cats. We found that acidification of the ESOc increased the number of c-fos positive neurons in the area postrema (AP), vestibular nucleus (VN), parabrachial nucleus (PBN), nucleus ambiguus (NA), dorsal motor nucleus (DMN), and all subnuclei of the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS), but one. Acidification of the ESOt activated neurons in the central (CE), caudal (CD), dorsomedial (DM), dorsolateral (DL), ventromedial (VM) subnuclei of NTS, and the DMN. Vagotomy blocked all c-fos responses to acid perfusion of the whole esophagus (ESOw). Perfusion of the ESOc or ESOt with PBS activated secondary peristalsis (2P), but had no effect on blood pressure, heart rate, or respiratory rate. Perfusion of the ESOc, but not ESOt, with HCL activated pharyngeal swallowing (PS), profuse salivation, or physiological correlates of emesis. Vagotomy blocked all physiological effects of ESOw perfusion. We conclude that acidification of the ESOc and ESOt activate different sets of pontomedullary nuclei and different physiological responses. The NTSce, NTScom, NTSdm, and DMN are associated with activation of 2P, the NTSim and NTSis, are associated with activation of PS, and the AP, VN, and PBN are associated with activation of emesis and perhaps nausea. All responses to esophageal fluid perfusion or acidification are mediated by the vagus nerves.

Keywords: medulla, pons, esophagus, hydrochloric acid, c-fos, cat

1. Introduction

Prior studies (Shuai, et al., 2004; Suwanprathes, et al., 2003) have found that perfusion of the esophagus with HCl and pepsin in anesthetized animals caused activation of neurons in various brain nuclei. However, in these studies no attempt was made to prevent esophageal reflux of the perfusate to the pharynx or larynx. In one study (Suwanprathes, et al., 2003) evidence of such reflux occurred as the investigators observed brief periods of aspiration, breathing difficulty, and accumulation of fluid in the pharynx. Therefore, it is difficult to be certain in these prior studies whether the observed brain responses were due to stimulation of acid sensitive receptors in the esophagus, pharynx, or larynx. A difference in the distribution of the perfusate in these studies could also account for the observed differences in brain responses.

The only prior studies of the effects of acid in the esophagus on activation of the central nervous system were conducted in rats (Shuai, et al., 2004; Suwanprathes, et al., 2003). However, the esophagus of rats is anatomically and functionally significantly different from that of humans. Unlike humans, rats have not been found to have physiological processes, i.e. emesis, eructation or regurgitation, that produce retrograde transport of contents through the esophagus. These processes are centrally mediated (Bredenrood et al., 2007; Lang and Sarna, 1987) and some are triggered by activation of acid-sensitive esophageal receptors (Baron et al., 1993; Milla, 1990). Therefore, the stimulation of the rat esophagus is not likely to activate the same physiological processes and areas of the brain as would occur with similar stimulation in humans.

In all of the prior studies of the effects of acid-pepsin exposure of the esophagus on the activation of brain nuclei (Shuai, et al., 2004; Suwanprathes, et al., 2003), the entire esophagus was exposed. However, prior studies have found that the proximal and distal portions of the esophagus have different functions especially related to luminal stimuli. The distal esophagus is commonly exposed to acidic gastric reflux (Grossi et al., 2001; Mittal et al. 1995) secondary to spontaneous transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations and in normal individuals most of these episodes are not sensed (Grossi et al., 2001; Singh et al., 1993). On the other hand in adults, the proximal esophagus is less often exposed to acidic gastric reflux (Emerenziani et al., 2009; Oelschalger et al., 2006) and when it is in adults (Emerenziani et al., 2009; Oelschalger et al., 2006) or infants (Milla 1990), it often causes nausea, vomiting, or regurgitation. In addition, esophagitis of the upper but not lower esophagus is associated with swallow-related emesis (Baron et al. 1993). One of the main functions of the distal esophagus is to promote transport of contents to the stomach whereas the primary function of the proximal esophagus is to prevent reflux to the pharynx and larynx. Therefore, it is highly likely that the proximal and distal esophagus may project different types of afferent information to different portions of the brain.

The aim of this study was to investigate the effects of hydrochloric acid in the cervical and thoracic portions of the esophagus on the activation of neurons in the brain stem of an animal model, i.e. the cat, with an esophagus similar to that of humans. Prior studies have found that the cat esophagus is both structurally (Crouch 1969; Goyal and Paterson, 1989) and functionally (Goyal and Paterson, 1989; Lang et al., 2001) very similar to that of humans. In addition, considering the significant functional differences between the proximal and distal esophagus, we hypothesized that acid exposure of each area may have different effects on the brain. The correlation of specific anatomically defined esophageal functions with specific brain activation patterns could provide important information for understanding the function of specific brain areas.

2. Results

2.1 Effects of esophageal acidification on physiological function

2.1.1 Secondary peristalsis

We found that the perfusion of the whole esophagus with PBS or HCl had no significant effects on femoral arterial blood pressure, heart rate, or respiratory rate (Table 1). Perfusion of the whole esophagus with PBS increased the rate of activation of secondary peristalsis above control levels, and HCL perfusion had no additive affects (Fig 1). Similarly, the perfusion of the cervical or thoracic esophagus with HCl significantly increased the rate of secondary peristalsis above control levels, but the response to HCl was not significantly greater than the response to PBS (Fig 2,3).

Table 1. The effects of perfusion of various regions of the esophagus with PBS or HCl on cardiovascular and respiratory variables.

| Cervical Esophagus | Thoracic Esophagus | Whole Esophagus | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | PBS | HCl | None | PBS | HCl | None | PBS | HCl | |

| MAP | 110 ± 5 | 110 ± 6 | 109 ± 5 | 105 ± 7 | 104 ± 5 | 109 ± 7 | 108 ± 6 | 106 ± 4 | 108 ± 4 |

| HR | 204 ± 11 | 198 ± 14 | 195 ± 18 | 201 ± 12 | 197 ± 15 | 208 ± 9 | 195 ± 7 | 189 ± 13 | 191 ± 12 |

| RR | 18± 4 | 20± 6 | 20± 4 | 20± 3 | 20± 4 | 20± 3 | 23± 4 | 23± 3 | 24± 5 |

N=4, None, no fluid administered; PBS, 0.1 M PBS; HCl, 0.1N HCl; MAP, mean arterial pressure; HR, heart rate; RR, respiratory rate. PBS and HCl groups within each esophageal perfusion category, i.e. cervical, thoracic, and whole, were compared to the control group, i.e. None, using ANOVA with repeated measures and no comparisons were significantly different at P<0.05. This table excludes cardiorespiratory activity that occurred during bouts of nausea and vomiting.

Figure 1.

The effects of perfusion of the whole esophagus with PBS and HCl. N, no fluid; PBS, phosphate buffered saline; HCl, 0.1 N hydrochloric acid. N=4; *, P < 0.05 compared with N; **, P< 0.05 compared with PBS. Note that both PBS and HCl caused a significant increase in the rate of secondary peristalsis, but only HCL caused a significant increase in pharyngeal swallows

Figure 2.

The effects of perfusion of the cervical or thoracic esophagus with PBS and HCl. See Figure 1 for definition of symbols and identification of statistical analysis. Note that PBS perfusion of only the cervical esophagus caused an increase in the rate of activation of secondary peristalsis. Perfusion of the cervical or thoracic esophagus with HCl caused an increase in secondary peristalsis. However, perfusion of the cervical but not thoracic esophagus caused a significant increase in pharyngeal swallows

Figure 3.

The effects of perfusion of the cervical esophagus with PBS and HCl. FABP, femoral arterial blood pressure, ESO#, esophageal pressure # cm from the CP; GH, geniohyoideus, TH, thyrohyoideus, CP, cricopharyngeus; CT, cricothyroideus; 2P secondary peristalsis; Ph Sw, pharyngeal swallow, PBS, phosphate buffered saline; HCl, hydrochloric acid at 0.1N. Note that with no fluid perfusion through the cervical esophagus no responses occurred in the esophagus, pharynx or larynx. On the other hand PBS perfusion caused activation of 2P and with perfusion with HCl did not increase the rate of 2P, but did increase the rate of pharyngeal swallows.

2.1.2 Pharyngeal swallows

Perfusion of the whole (Fig 1) or cervical (Fig 2,3) esophagus with PBS had no effects on activation of pharyngeal swallows above control levels, but subsequent perfusion with HCL significantly increased the rate of activation of pharyngeal swallows above control levels as well as that activated by PBS. Perfusion of the thoracic esophagus with PBS or HCl had no effect on pharyngeal swallows (Fig 2). Pharyngo-esophageal swallows, i.e. pharyngeal swallow followed in temporal sequence by esophageal peristalsis, were not observed.

2.1.3 Physiological correlates of emesis

The physiological responses associated with nausea and/or vomiting occurred in 75% of animals in which the whole esophagus was perfused with HCl at a mean time delay of 21+ 6 minutes (Fig 4), and 50% of the animals in which the cervical esophagus was perfused with HCl at a mean time delay of 30+6 minutes. None of the physiological responses associated with nausea or vomiting occurred in any animal in which the thoracic esophagus was perfused with HCl or the whole esophagus was perfused with only PBS or with HCL after vagotomy.

Figure 4.

The effects of perfusion of the whole esophagus with HCl. See Figure 3 for definition of symbols. Note that after 10 minutes of HCl perfusion the above bout of digestive, respiratory and cardiovascular responses occurred over a period of about 1 minute. These responses included an increase in swallowing, increase in basal esophageal pressure and CP EMG activity (at arrow), retrograde esophageal peristalsis, rhythmical increased ventilation (at bar), and significant change in blood pressure. All of these responses have previously been found to be physiological correlates of nausea and vomiting (Lang et al., 1987; Lang et al., 1993).

2.1.4 Condition of the esophagus

The esophagus was not examined histologically after perfusion, but was examined visually and there were no lesions or erosions visible.

2.2. Effects of Esophageal Acidification on Brain Stem Neurons

2.2.1 Cervical Esophageal Acidification

We found that acidification of the cervical esophagus significantly increased the number of c-fos positive neurons in numerous pontomedullary nuclei (Figs 5-8) including the following subnuclei of the NTS (Figs 5, 6) that are listed in order of greatest magnitude of response: caudal (NTScd (Fig 9)), central (NTSce (Fig 9)), interstitial (NTSis) (Fig 10), intermediate (NTSim (Fig 10)), dorsomedial (NTSdm), medial (NTSmed), dorsolateral (NTSdl), ventral (NTSv), and ventromedial (NTSvm). In addition, the following medullary nuclei were found to have increased number of c-fos positive neurons (Fig 7, 8): area postrema (AP) (Fig 11), caudal (DMNc) and rostral (DMNr (Fig 11)) dorsomotor nucleus of the vagus, and the rostral (NAr) and caudal (NAc) nucleus ambiguous. This stimulus also increased the number of c-fos positive neurons in the following rostral medullary and pontine nuclei (Fig 8): the vestibular nucleus (VN) (Fig 12), and parabrachial nucleus (PBN) (Fig 12). However, the greatest increase in the number of c-fos positive neurons was found in the NTScd (Fig 5, 9), AP (Fig 8,11), VN Figs 8,12), and PBN (Figs 8, 12).

Figure 5.

The effects of selective perfusion of the esophagus with HCl on the number of c-fos positive neurons in six subnuclei of the NTS. CE, central MED, medial; IM, intermediate; IS, interstitial; COM, commissural; CD, caudal subnuclei of the NTS. Control, PBS perfusion of the whole esophagus; Cervical, HCL perfusion of the cervical esophagus; Thoracic, HCL perfusion of the thoracic esophagus; Vagotomy, HCL perfusion of the whole esophagus after vagotomy. Note that cervical esophageal acidification caused a significantly greater number of c-fos immunoreactive neurons in NTSmed, NTSim, NTS, is than thoracic esophageal acidification.

Figure 8.

The effects of selective perfusion of the esophagus with HCl on the number of c-fos positive neurons in various pontomedullary nuclei. Raphe, raphe magnus; VN, vestibular nucleus; PBN, parabrachial nucleus; AP, area postrema. See Fig 5 for identification of groups. Note that cervical but not thoracic esophageal acidification increased the number of c-fos immunoreactive neurons in the VN, PBN and AP.

Figure 6.

The effects of selective perfusion of the esophagus with HCl on the number of c-fos positive neurons in five subnuclei of the NTS. DM, dorsomedial; DL, dorsolateral; V, ventral; VL, ventrolateral; and VM, ventromedial subnuclei of the NTS. See Fig 5 for identification of groups. Note that cervical or thoracic esophageal acidification increased the number of c-fos immunoreactive neurons in the NTSdm and NTSvm.

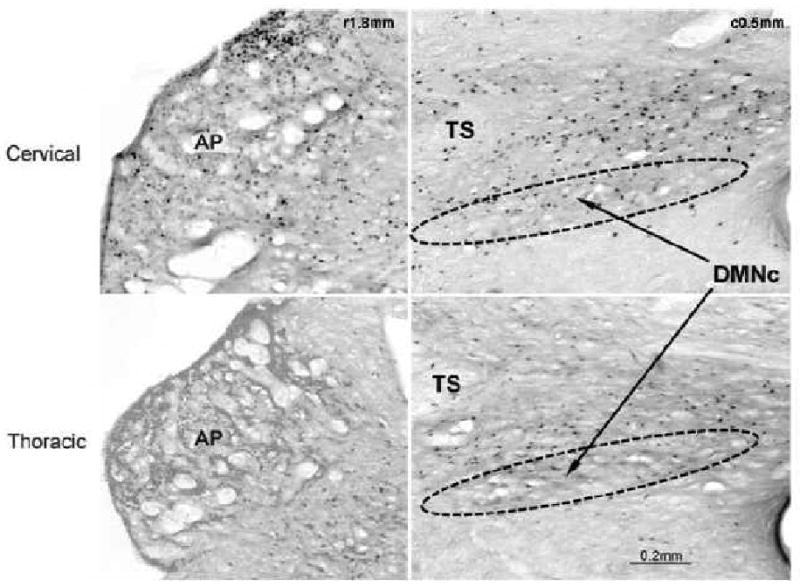

Figure 9.

Comparison of cervical and thoracic esophageal acidification on the number of c-fos immunoreactive neurons in the NTScd and NTSce. TS, tractus solitaries; NTScd, caudal subnucleus of the nucleus tractus solitaries; NTSce, central subnucleus of the NTS; r#, distance rostral to obex; c# distance caudal to obex. Note that cervical and thoracic esophageal acidification had similar effects on the number of c-fos immunoreactive neurons in the NTScd and NTSce.

Figure 10.

Comparison of cervical and thoracic esophageal acidification on the number of c-fos immunoreactive neurons in the NTSis and NTSim. TS, tractus solitaries; NTSis, interstitial subnucleus of the nucleus tractus solitaries; NTSim, intermediate subnucleus of the NTS; r#, distance rostral to obex. Note that cervical esophageal acidification had significantly greater effects on the number of c-fos immunoreactive neurons in the NTSis and NTSim than thoracic esophageal acidification.

Figure 7.

The effects of selective perfusion of the esophagus with HCl on the number of c-fos positive neurons in vagal motor nuclei. DMNc, caudal dorsal motor nucleus, DMNr, rostral dorsal motor nucleus; NAr, rostral nucleus ambiguus; NAc caudal nucleua ambiguous. See Fig 5 for identification of groups. Note that cervical esophageal acidification increased the number of c-fos immunoreactive neurons in all of the vagal motor nuclei, but thoracic esophageal acidification only increased the number of c-fos positive neurons in the dorsal motor nuclei.

Figure 11.

Comparison of cervical and thoracic esophageal acidification on the number of c-fos immunoreactive neurons in the AP and DMNr. AP, area postrema; TS, tractus solitaries; DMNr, rostral division of the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus; c#, distance caudal to obex; r#, distance rostral to obex. Note that cervical esophageal acidification had significantly greater effects on the number of c-fos immunoreactive neurons in the AP than thoracic esophageal acidification, but there was no difference in the DMNr.

Figure 12.

Comparison of cervical and thoracic esophageal acidification on the number of c-fos immunoreactive neurons in the PBN and VN. PBN, parabrahcial nucleus; VN, vestibular nucleus; r# distance rostral to obex; P#, plane number corresponding to section in atlas of Berman (Berman 1968). Note that cervical esophageal acidification had significantly greater effects on the number of c-fos immunoreactive neurons in the PBN and VN than thoracic esophageal acidification.

2.2.2 Thoracic Esophageal Acidification

We found that acidification of the thoracic esophagus significantly increased the number of c-fos positive neurons in the following subnuclei of the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) and they are listed in order of greatest magnitude (Figs 5-7): NTScd (Fig 5,9), NTSce (Fig 5, 9), NTSdm, NTSdl and NTSvm. In addition, thoracic esophageal acidification increased the number of c-fos positive neurons in the DMNc and DMNr (Figs 7, 11).

2.2.3 Effects of vagotomy on the brain stem responses to esophageal acidification

We found that prior bilateral cervical vagotomy blocked all responses of the brain stem activated by acidification of the esophagus (Figs 5-8).

3. Discussion

3.1 Methodological considerations

We found that exposure of the esophagus to acid activated neurons throughout the medulla and pons in the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS), dorsal motor nucleus (DMN), nucleus ambiguous (NA), area postrema (AP), vestibular nucleus (VN), and parabrachial nucleus (PBN). These findings were similar to those observed in a prior study in rats of the effects of acid-pepsin infusion into the esophagus (Shuai et al., 2004) on c-fos activation in the brain. However, the results of this rat study were obtained after infusion of acid-pepsin into the distal esophagus 3 cm above the esophago-gastric junction, whereas we found this activation pattern after stimulation of cervical, but not thoracic esophagus. Given that in this rat study (Shuai et al., 2004) no attempt was made to confine the infusate to the distal esophagus, it is highly likely that the infusate was refluxed to the upper esophagus and perhaps beyond. Such reflux of esophageal infusate even as far orad as the pharynx or larynx was observed in another similar c-fos study using rats (Suwanprathes et al., 2003). These investigators found that infusion of acid-pepsin at 2cm above the esophago-gastric junction sometimes caused accumulation of fluid in the pharynx and signs of breathing difficulty or aspiration. Furthermore, the results from these two very similar rat studies were very different. One study (Suwanprathes et al., 2003) found activation primarily in the amygdala, NTS, NA and RVLM while the other (Shuai et al., 2004) found activation primarily in the amygdala, PVN, PBN, NTS, DMN and APO. Therefore, given the relatively uncontrolled nature of these two prior rat studies, and the significantly different results obtained between them, we find it difficult to make conclusions based on these prior rat studies. In addition, our studies were not prone to this technical problem, because we cannulated the esophagus at both ends to ensure that the perfusate was applied only to the targeted sites.

The technique that we used, i.e. perfusion of the esophagus with acid for one hour, could have had effects on the brain mediated locally by activating receptors in the esophagus or systemically by absorption into the circulation. In a prior study (Lang et al., 2008) we found that a 30 minute perfusion of the esophagus with HCl did not result in absorption of HCl into the circulation in concentrations that were not fully buffered by the blood. In addition, in this current study we found that all brain and physiological responses to perfusion of the esophagus with HCl were prevented by prior transection of the cervical vagus nerves indicating that the activated receptors were localized to the receptive field of the vagus nerves. Therefore, it is highly unlikely that HCl was absorbed into the vascular system activating the brain by its effects outside of the esophagus.

We found that the pharyngeal swallows were independent of esophageal peristalsis, which confirmed our prior observation (Lang et al., 2001) that these events are physiologically connected by peripheral feedback and not central neural processes. That is, esophageal peristalsis never accompanies a swallow unless the esophageal peristalsis is reflexly activated by a bolus stimulating the esophageal receptors. In the current studies, the esophagus was cannulated just caudal to the CP so that the pharyngeal swallows could never transport their boluses to the esophagus and as such never activate esophageal peristalsis. This physiological phenomenon assisted our interpretation of results, because in these studies esophageal peristalsis could always be quantified independently of pharyngeal swallows. Thus, the brain nuclei controlling each event could be considered separately.

3.2 Correlation of brain stem and physiological responses to perfusion of selective areas of the esophagus

The primary finding of this study was the large difference between the effects of acidification of the cervical as compared to the thoracic esophagus on activation of pontomedullary neurons. Acidification of the cervical esophagus significantly activated all subnuclei of the NTS, but one, as well as the DMN, NA, AP, VN, and PBN. On the other hand, acidification of the thoracic esophagus activated neurons in only a few of the NTS subnuclei and the DMN. This finding suggests that the cervical esophagus contains a greater number or variety of receptors and afferent pathways that project to the pons or medulla than does the thoracic esophagus, and this was reflected in our physiological studies as well. We found that perfusion of the cervical esophagus with HCl was associated with activation of secondary peristalsis, pharyngeal swallowing, and the physiological responses associated with nausea or vomiting while only secondary peristalsis was activated by perfusion of the thoracic esophagus.

Prior studies have also observed that the proximal esophagus is more sensitive to stimulation of some reflexes than the distal esophagus. While stimulation of secondary peristalsis (Chen and Cook, 2009) is activated at similar thresholds in both the proximal and distal esophagus, studies (Aslam et al., 2003) have found that the thresholds for activation of the esophago-UES relaxation reflex and belching are lower for the proximal than the distal esophagus. In addition, emesis has only been associated with stimulation of the proximal but not the distal esophagus (Baron et al., 1993), and the proximal esophagus is more sensitive to acid reflux than the distal esophagus (Emerenziani et al., 2009).

3.2.1 Nucleus tractus solitarius

The patterns of activation of pontomedullary nuclei and our physiological studies suggest specific roles for these brain areas in controlling various functions. Thus acid exposure of the cervical and thoracic esophagus activated the following nuclei in common and listed in descending order of magnitude: NTSce, NTScd, DMN, NTSdm, and NTSvm. The activation of the NTSce is consistent with numerous prior anatomical and physiological studies. The NTSce is the primary premotor nucleus of the both cervical and thoracic esophagus (Atlschuler at al., 1989; Barrett et al., 1994; Katz and Karten 1983; Wank and Neuhuber 2001), and the NTSce is the primary NTS subnucleus activated during the esophageal phase of swallowing, i.e. secondary peristalsis (Lang et al. 2004). In addition, prior studies in humans found that the sensitivity to activate secondary peristalsis is the same in both proximal and distal esophagus (Chen and Cook 2009). Similarly in our physiological studies, we found that the responses of the cervical and thoracic esophagus to either PBS or HCL were similar. Therefore, is it likely that the NTCce may be the primary relay for the specific set of esophageal receptors that mediates secondary peristalsis as well as perhaps other esophageal reflexes, e.g. esophago-UES contractile reflex (Lang et al. 2001). In a prior study (Lang et al. 2001) we found evidence that these receptors may be the slowly adapting muscular tension receptors.

We found that the NTScd (referred to by some as the caudal portion of the NTSmed (Dean and Seagard, 1997; Finley and Katz, 1992; Takakura et al, 2007) or the NTScom (Frysak et al. 1984; Kalia and Mesulam, 1980; Katz and Karften, 1983)) and NTSdm were strongly activated by stimulation of the cervical or thoracic esophagus and these responses were absent after vagotomy. These NTS subnuclei are the primary cardiovascular related NTS subnuclei that receive input from the carotid body and are activated by stimulation of the carotid body (Dean and Seagard, 1997; Finley and Katz, 1992; Takakura et al., 2007). However, we did not observe any cardiovascular effects of esophageal perfusion with either PBS or HCl, except for at most one short lasting change in blood pressure in each animal that received HCL perfusion of either the whole or cervical esophagus. Although the function of this nucleus in our studies is unknown, the anatomical connection between the esophagus and the NTScd is well established as the NTScd has been found to receive strong termination of vagal afferents from the esophagus in pigeons (Katz and Karten, 1983), rats (Frysak et al., 1984) and cats (Kalia and Mesulam, 1980).

The primary NTS subnuclei selectively activated by HCl perfusion of the cervical esophagus were the NTSis and NTSim. From both anatomical and physiological studies these NTS subnuclei have been associated with the pharynx. The NTSis and NTSim are the primary premotor nuclei of the pharynx (Altschuler et al., 1989; Bao, et al. 1995; Broussard et al., 1998) and these are the primary NTS subnuclei activated during the pharyngeal phase of swallowing (Lang et al. 2004). Although, a pharyngeal response to esophageal stimulation is not a common finding in the literature, one has been reported. It was found in decerebrate cats that the slow distension of the mid esophagus that activated secondary peristalsis 83% of the time also activated the pharyngeal phase of swallowing 2% of the time (Lang et al., 2004). Our current studies suggest that esophageal distension may not be the optimum stimulus and the mid esophagus may not be the optimum location, because we found that perfusion of the cervical but not thoracic esophagus significantly activated pharyngeal swallowing. The specific receptor mediating this pharyngeal response is unknown, but it is probably one of the two mucosal mechanoreceptors. The rapidly adapting mucosal touch receptor has previously been found to be associated with activation of belching (Lang et al., 2001), but the role of the slowly adapting mucosal tension receptor has not been defined. These studies suggest that this mucosal tension receptor may function in part to stimulate swallowing.

The NTSvl was the only NTS subnucleus not significantly activated by esophageal acidification, but this was likely due to variability in the mean values, because acid in the cervical esophagus more than doubled the number of c-fos positive neurons observed in the NTSvl. The source of this variability is unknown.

3.2.2 Dorsal motor nucleus and nucleus ambiguous

The only motor nucleus activated in common in response to perfusion of the cervical and thoracic esophagus with HCl was the DMN. The DMN is the motor nucleus of the smooth muscle portion of the esophagus (Collman et al., 1993) including the lower esophageal sphincter (Rossiter et al., 1990; Sang and Goyal, 2000; Niedringhaus et al. 2008) as well as the crural diaphragm (Niedringhaus et al. 2008) which participates in the function of the LES (Boyle et al 1985). Studies suggest that the DMNr is primarily involved in excitation of the esophagus (Lang et al., 2004), lower esophageal sphincter (Rosssiter et al., 1990; Niedringhaus et al. 2008), and the crural diaphragm (Niedringhaus et al. 2008), as occurs during esophageal peristalsis, whereas the DMNc is primarily involved in inhibition of the esophagus and lower esophageal sphincter (Rossiter et al., 1990; Lang et al., 2004; Niedringhaus et al. 2008), as in response to pharyngeal stimulation (Lang et al., 1998; Trifan et al. 1995) or deglutitive inhibition (Goyal and Paterson, 1989). We found that the DMNc and DMNr were equally activated by cervical and thoracic esophageal acidification, yet in our prior study (Lang et al., 2004) we found that distension of the mid esophagus that caused secondary peristalsis was associated with greater activation of DMNr than DMNc. It is likely that the equal activation of DMNr and DMNc in the current studies was due to the added response of pharyngeal swallows, because in our prior study (Lang et al. 2004) we found that pharyngeal swallows were associated with greater activation of DMNc than DMNr.

Acidification of the cervical esophagus activated neurons in the NA. The NA is the location of the motor neurons of the striated muscle esophagus in cats (Collman et al., 1993) as well as the pharyngeal (Collman et al., 1993; Holstege et al., 1983) and laryngeal (Lawn et al., 1966) motor neurons in most species. Thus it was not surprising that the pharyngeal swallows, secondary peristalsis, and physiological correlates of emesis activated by perfusion of the cervical esophagus with acid was associated with an increase in the number of c-fos immunoreactive neurons in the NA. In addition in our prior study (Lang et al., 2004), we found that both secondary peristalsis and pharyngeal swallows were associated with activation of the NA. Other studies have also found that vomiting is associated with activation of the NA (De Jonghe and Horn, 2009; Miller and Ruggiero, 1994; Ray, et al., 2009).

3.2.3. Area postrema

Acidification of the cervical, but not thoracic, esophagus strongly activated neurons in the area postrema (AP) and activated bouts of physiological responses associated with nausea or vomiting. Vagotomy blocked both the activation of neurons in the AP as well as all of the physiological responses associated with nausea or vomiting. Prior studies have found in humans that esophageal mucosal irritation causes nausea and vomiting (Baron et al., 1993) and many studies (Boissonade and Davsion, 1996; Boissonade et al., 1994; Borison 1989; Miller and Ruggiero, 1994) have found a strong correlation between the AP and emesis. Therefore, we conclude that the cervical esophagus contains receptors sensitive to acid that cause emesis and this emetic response is associated with activation of the AP. Whether the AP is essential for initiation of this form of emesis as it is for some other forms of emesis (Borison 1989), e.g. cisplatin-induced (McCarthy and Borison, 1984), is unknown.

3.2.4 Parabrachial nucleus

Another area of the brain activated strongly by acidification of the cervical, but not thoracic, esophagus is the PBN. The PBN receives afferents from numerous NTS subnuclei as well as the AP (Herbert et al., 1990), and projects to the amygdala and forebrain forming a viscerosensory pathway from hindbrain to forebrain (Jia et al., 1994; Balaban 1996). One of the primary functions of the PBN is to process afferent information from various chemoreceptors including those of the cardiovascular system (Hayward and Felder, 1995) and the tongue (Miyaoka et al., 1997; Scott and Small, 2009). Perhaps acid sensitive receptors of the cervical esophagus that activate vomiting also project to the PBN or perhaps there are other types of chemoreceptors in the cervical esophagus. Regardless, prior studies have found that the PBN is strongly activated by the administration of emetic agents (De Jonghe and Horn, 2009), and lesions of the PBN disrupt conditioned taste aversion in rats (Mungarndee et al., 2006). Conditioned taste aversion in rats is considered analogous to emesis in animals capable of emesis (Grant 1987; Rabin et al., 1986). Thus, the activation of PBN in our experiments may be related to its role in emesis activated by chemical stimulation of the esophageal mucosa.

3.2.5 Vestibular nucleus

The other pontomedullary structure strongly activated by cervical, but not thoracic, esophageal acidification, was the VN. The VN has also been associated with emesis, but motion- not chemical-induced sickness (Cai et al. 2007; Pompeiano et al., 2002). However, the VN has extensive projections to and from the PBN (Balaban, 2002) and combined with the viscerosensory connections of the PBN discussed above and our findings that proximal esophageal acidification activated physiological correlates of nausea and vomiting suggest that perhaps the VN and PBN may participate in the observed autonomic correlates of nausea and vomiting. While the VN has not previously been associated with emesis or nausea other than that produced by unusual motion, our study is not the first to find activation of neurons in the VN with a physiological stimulus other than what may stimulate the vestibular system. It has been found that high pressure distension of the stomach in rats caused increased c-fos immunoreactivity in the VN, PBN as well as the AP. Therefore, the VN along with the PBN may not just serve to mediate vegetative functions and anxiety associated with balance control (Balaban, 2002), but these nuclei may also act in concert to mediate similar responses, behaviors and sensations to other emetic or non-emetic stimuli. One such response may be nausea.

3.3 Conclusions

Acid exposure of the cervical esophagus activates far more pontomedullary nuclei and physiological responses than does acid exposure of the thoracic esophagus, suggesting that the cervical esophagus is the source of more reflexes and reflex responses. All of the effects stimulated by esophageal acidification are mediated by the vagus nerves, indicating that the observed responses are mediated by physiological receptors and afferent pathways of the esophagus. The acid-insensitive slowly adapting muscular tension receptors of the esophagus probably initiate secondary peristalsis that is mediated by the central subnucleus of the NTS. The acid-sensitive slowly adapting mucosal tension receptors of the esophagus may initiate pharyngeal swallows that are mediated by the interstitial and intermediate subnuclei of the NTS. Unknown acid-sensitive receptors of the esophagus initiate nausea and emesis that is probably mediated by the AP, PBN and VN. These studies provide a physiological basis for prior clinical observations in humans that acid reflux into the cervical esophagus only causes nausea and vomiting.

4. Experimental Procedures

4.1 Animal Preparation

We studied 42 cats of either sex weighing from 2.1 to 4.3Kg. The surgical and experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Medical College of Wisconsin. The cats were anesthetized using alpha-chloralose and the dose was titrated to provide a surgical plane of anesthesia while minimizing the drug dose. The cats were first injected IP with 55mg/kg of alpha-chloralose and one hour later their anesthetic plane was assessed. Those animals requiring more anesthesia were administered IP an additional 25% of the original dose. We waited another hour and if the cats still required more anesthesia they were administered Nembutal at 3mg/kg IV. Most animals did not require Nembutal. The anesthetic plane was determined by lack of consciousness and lack of response to noxious stimulation. In this plane, the animals also had diminished palpebral, corneal, and pupillary light reflexes; and we estimate that the cats were in Stage III, plane 2 of anesthesia. The noxious stimuli used to test the anesthetic plane were pinching of the skin over various parts of the body using a hemostat, cutting the skin in the femoral region, and blunt dissection of subcutaneous tissues. The cats were instrumented to allow selective perfusion of the whole (N=20), cervical (N=11), or thoracic (N=11) esophagus in order to determine the effects of selective esophageal acidification on the activation pattern of c-fos in neurons of the brain stem or on relevant physiological systems, i.e. upper digestive, cardiovascular, and respiratory. The goal was to not only determine the effects of selective esophageal acidification on neurons of the brain stem, but also to relate these changes to specific physiological functions. The animals used for c-fos studies received no further surgical preparation in order to avoid additional unwanted sensory activation, but those animals used for physiological studies were instrumented further to record femoral arterial blood pressure, esophageal manometry, and EMG activity of appropriate pharyngeal, laryngeal and hyoid muscles. In some cats (N=9) the role of the vagus nerves in mediating the c-fos or physiological responses to stimulation of the whole esophagus was determined. In all cats the trachea was cannulated to prevent aspiration and the femoral vein cannulated to allow hydration using 0.9% NaCl.

In all studies the esophagus was prepared similarly. The proximal esophagus just below the cricopharyngeus muscle (CP) was cannulated using polyethylene tubing (PE 260). The ventral midline of the neck was opened, the CP identified, and a suture was placed around the proximal cervical esophagus just distal to the CP. The cannula was inserted through the mouth into the esophagus and the cannula was ligated in place. The distal esophagus was cannulated through the abdominal wall and stomach. The abdomen was opened ventrally along the midline and the gastric cardia identified. A small incision was made at the border of the cardia and fundus and a 4.0 Fr endotracheal tube was inserted into the cardia and through the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) such that the end of the catheter rested in the distal esophagus. The esophageal catheter was held in place by suturing to the wall of the stomach. The stomach was cannulated to allow suction of gastric contents thereby preventing accumulation of acid gastric juice. For studies of selective perfusion of the esophagus, the esophagus was ligated as far distally in the neck as possible without entering the thoracic cavity to form cervical and thoracic portions that were isolated from each other. For studies of the effects of vagotomy, a bilateral cervical vagotomy was performed before perfusion of the whole esophageal with fluids.

The cats used for the physiological recording studies had solid state pressure transducers placed in the esophagus through the perfusion cannulas to record esophageal pressure, bipolar stainless steel wires (Cooner Wire Co AS363) sewn into the cricopharyngeus (CP), geniohyoideus (GH), thyrohyoideus (TH), and cricothyroideus (CT) muscles to record EMG activities, and the femoral artery cannulated using PE50 tubing to record arterial blood pressure.

4.2. Protocols

Four experimental groups for examining the effects of esophageal acidification were used for both the c-fos and the physiological studies: 1. perfusion of the cervical esophagus, 2. perfusion of the thoracic esophagus, 3. perfusion of the whole esophagus, and 4. perfusion of the whole esophagus after vagotomy. However, the manner in which the stimuli were applied differed between the c-fos and physiological studies.

4.2.1 C-fos studies

In the c-fos studies, HCl was administered for one hour followed by two hours of PBS in all groups, but the control group. In the control group, Group 3, PBS (pH 7.4) was perfused for all three hours of the study.

4.2.2. Physiological studies

The physiological studies were designed to not only relate the brain areas activated by esophageal acidification to the physiological responses, but also to distinguish between the effects of HCl and the effects of perfusion itself. Therefore, for all four groups studied the physiological responses before perfusion (30 minutes), during PBS (pH 7.4) perfusion (30 minutes), and during HCl perfusion (60 minutes) were compared. We recorded physiological responses for 30 minutes before and during PBS (pH 7.4) perfusion in order to obtain stable baseline recordings and we recorded physiological responses during HCl perfusion for 60 minutes in order to duplicate the stimulus used for the c-fos studies.

The physiological variables quantified included mean arterial blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, secondary peristalsis rate, pharyngeal swallowing rate, and the number of bouts of physiological responses associated nausea and vomiting (Lang and Sarna, 1987; Lang et al., 1993). The physiological responses associated with or unique to emesis include increased swallowing rate, increased tone of the esophagus and CP, retrograde peristalsis of the esophagus, rhythmical ventilation of retching, constant elevated tone of the CT an GH, rhythmical simultaneous activation of TH and CP out of phase with retching movements, profuse salivation (Lang and Sarna, 1987; Lang et al., 1993). The mean arterial blood pressure, heart rate, and respiratory rates during the last 10 minutes of each time period were compared. The heart rate was determined from the blood pressure tracing. Respiratory rate was determined from changes in esophageal pressure caused by the changes in intrathoracic pressure during ventilation. The physiological responses associated with nausea and vomiting occurred in bouts lasting from 1-2 minutes that included increased rate of swallowing, profuse salivation, elevated basal esophageal pressure, retrograde esophageal peristalsis, increased basal CP EMG activity, short term (less than 30s) but significant change in blood pressure, and rapid, rhythmical, and elevated ventilation. Profuse salivation was observed as pooling of saliva in the oral cavity and/or an overflow of saliva out of the oral cavity.

4.3 Techniques

4.3.1 Manometric recording of esophageal pressure

The intraluminal pressure of the esophagus was measured using three channel solid state manometric catheter (Gaeltec, Medical Measurements and Millar Instruments). The individual recording sites were 3cm apart and they were positioned in mid organ. The pressures were recorded using DC preamplifier (P122) of a Grass polygraph (Model 7) and stored on computer.

4.3.2 EMG recording

Bipolar Teflon coated stainless steel wire (AS 632, Cooner Wire, Chatsworth, CA) bared for 2-3 mm were placed in each muscle and the wires were fed into a differential amplifier (AM Systems 1800). The electrical activity was filtered (bandpass of 01-3.0KHz) and amplified (1000×) before feeding into the computer.

4.3.3 C-fos immunoreactivity

At the end of the experiments the animals were administered Nembutol (30mg/kg) and 20ml of Heparin (1000U/ml) intravenlusly, and ties were placed around the jugular veins. The animals were then placed on a ventilator (20/min; 15ml/kg) and the chest opened. The jugular veins were ligated and cut toward the head, and the descending aorta clamped. A 14 gauge needle was inserted into the left ventricle and the heart infused with 0.1M PBS at about 50ml/min at a mean infusion pressure of 80-100mmHg. All vessels at the base of the heart except for the aorta were then ligated with a single tie. After infusion of 3L of 0.1M PBS, the infusion was changed to 4% paraformaldehyde fixative in 0.1 M PBS. The brainstem was removed and stored in 0.1M PBS containing 30% sucrose at 4°C for 24-36 hrs. Transverse sections through the brain stem (40 um) were cut, floated in 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4), and divided into three sequential groups. Two groups were processed immunohistochemically for c-fos immunoreactivity using an avidin-biotin technique with one set of sections incubated in c-fos antibody and a second set of control sections incubated in pre-immune sheep serum. A third set of sections were stained with thionin for histological comparison. Sections for immunohistochemical processing were rinsed thoroughly in 0.1M PBS (2 × 15 mins) and then pretreated for 30 mins in 10% (w/v) heat-inactivated normal rabbit serum (Vector Labs.) containing 0.1% Triton X-100. Sections were washed in 0.1M PBS (2 × 15 mins) and transferred to the appropriate treatment set containing either sheep anti-c-fos protein primary antisera (Genosys; 1:6000) or dilute pre-immune sheep serum (Sigma Immunochemicals; (1:6000) for 18-24 hrs at room temperature. After rinsing with 0.1M PBS (2 × 15 mins), sections were incubated with biotinylated anti-sheep IgG secondary antibody for 60 mins followed by ABC reagent (Vector Labs.). Sections were again washed in 0.1M PBS (2 × 15 mins) and reaction incubated with hydrogen peroxide and diaminobenzidine using a nickel intensification procedure. Sections were washed in two additional changes of PBS, floated onto gelatin-coated slides and air dried, after which sections were dehydrated and cover-slipped with DPX mounting medium. Sections were examined under a light microscope (Olympus BH-2) to visualize staining for c-fos immunoreactivity and adjacent thionin stained sections were compared for histological localization of brain stem nuclei. Homologous absorption controls (10 uM solutions) were performed to examine the specificity of the c-fos antibody with the c-fos antibody pre-absorbed with c-fos peptide (Genosys).

4.3.4. Microscopic analysis

The c-fos is confined to the nucleus of activated cells, visualized in immunopositive cells as a dark, rounded or oval structure. Each subnucleus was identified from corresponding thionin stained sections by comparison with the prior studies (Kalia and Mesulam, 1980; Lang et al., 2004), except for the caudal and commissural subnuclei of the NTS (NTScd). In this study we only considered the nuclear region just caudal to obex that spanned the two halves of the brainstem to be the NTScom. All of the remainder of the NTS caudal to the obex was referred to as the NTScd. Nuclei staining positive for c-fos in each brainstem subnucleus were digitally recognized, counted and measured. The c-fos positive neurons were quantified in single sections at 0.5 mm intervals from 1.0 mm caudal to 5.0 mm rostral to obex for each animal using a Spot RT digital microscope camera on an Olympus BH-2 microscope. We chose the most representative slice within each 0.5 mm for each cat to accommodate differences in brainstem size and technical artifacts. The sections taken from the medulla were referenced to obex whereas the pontine structures were referenced to corresponding sections from the sterotaxic atlas of Berman (Berman, 1968).

4.3. 5. Image analysis

Grayscale microscopic images were digitized at 1600×1200 pixels and stored on computer and analyzed. The contrast of the images was first maximized and the dark areas marked and an overlay created by setting the threshold sufficient to fill the nuclear profiles of the darkest nuclei. This level of detection closely approximated 1/3 of maximum intensity. The number and shape factor ((4 × Pi × area)/perimeter2) of the neuronal nuclei were measured for each brainstem subnucleus using Image J software. The brainstem images contained sections of spherical nuclei cut at various orientations such that the nuclei appeared round to various oval shapes and sizes. The images also contained darkened areas which were not neuronal nuclei, and may have been microglia or histological artifacts. The artifacts were usually elongated objects and the microglia were usually very small and round. We excluded these objects from the analysis by setting the following exclusion criteria. Firstly, all objects with a shape factor greater than 1.0 or less than 0.2 were eliminated. A shape factor of 1 is a circle and 0 is a straight line, therefore anything above 1.0 was considered an artifact, and anything less than 0.2 was considered too long and narrow to represent a neuronal cell nucleus. A shape factor of less than 0.2 was rare. Objects with an area of less than 15um2 were considered too small to be neuronal cell nuclei. This exclusion criterion probably eliminated some real cell nuclei and resulted in an undercount, but this error was applied consistently across brain sections and therefore was not likely to cause differences among groups. The total number of nuclei with areas of less than 15um2 was less than 5% for any subnuclear region examined. Sometimes neuronal cell nuclei overlapped one another or the threshold procedure picked up only part of the cell nucleus. In both cases the problems were fixed by hand. The overlapping nuclei were separated and the incomplete nuclei were completed. These situations occurred at most twice per subnuclear region examined. After correction of the too large, small, and irregular objects the total count and mean measurements were taken for each subnuclear region of interest. Considering that the sections were 40um thick and the nuclei less than 20um in diameter and that we did not count nuclei in adjacent sections, there was no chance for counting the same nuclei twice in different sections. This automated analysis technique was used successfully in our prior study (Lang et al., 2004).

4.4 Physiological analysis

The physiological recordings were digitized and stored on computer using CODAS hardware and software. The magnitudes of the defined physiological events at the end of each experimental recording period were quantified. The motor responses quantified included heart rate, respiratory rate, mean arterial blood pressure, rate of esophageal peristalsis, rate of pharyngeal swallows, and the number of bouts of physiological correlates of nausea and vomiting.

4.5. Statistics

The average values of the number of c-fos positive nuclei were compared among experimental groups for each responsive brain nucleus. We used one-way ANOVA and Dunnett's multiple comparisons test for assessing differences of the individual experimental groups from control. For physiological studies in which the data was correlated in time, we used ANOVA with repeated measures and Newman-Keuls multiple comparison's test for assessing differences among all groups A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH grant RO1 DK-25731

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- AP

area postrema

- CP

cricopharyngeus

- CT

cricothyroideus

- DMN

dorsomedial nucleus

- DMNc

caudal DMN

- DMNr

rostral DMN

- EMG

electromyography

- ESOc

cervical esophagus

- ESOt

thoracic esophagus

- ESOw

whole esophagus

- GH

geniohyoideus

- HCl

hydrochloric acid

- HR

heart rate

- IP

intraperitoneal

- LES

lower esophageal sphincter

- MAP

mean arterial pressure

- NA

nucleus ambiguous

- NAc

caudal NA

- NAr

rostral NA

- NaCl

sodium chloride

- NTS

nucleus tractus solitareus

- NTScd

caudal subnucleus of NTS

- NTSce

central subnucleus of NTS

- NTScom

commisural subnucleus of NTS

- NTSdl

dorsolateral subnucleus of NTS

- NTSdm

dorsomedual subnucleus of NTS

- NTSim

intermediate subnucleus of NTS

- NTSis

interstitial subnucleus of NTS

- NTSmed

medial subnucleus of NTS

- NTSv

ventral subnucleus of NTS

- NTSvm

ventromedial subnucleus of NTS

- PBN

parabrachial nucleus

- PVN

paraventricular nucleus

- RR

respiratory rate

- RVLM

rostral ventrolateral medulla

- UES

upper esophageal sphincter

- VN

vestibular nucleus

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

5. Literature References

- Altschuler SM, Bao X, Bieger D, Hopkns DA, Miselis RR. Viscerotopic representation of the upper alimentary tract in the rat: sensory ganglia and nuclei of the solitary and spinal trigeminal tracts. J Comp Neurol. 1989;283:248–268. doi: 10.1002/cne.902830207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslam M, Kern M, Shaker R. Modulation of oesophago-UOS contractile reflex: effect of proximal and distal esophageal distension and swallowing. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2003;15:323–329. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2982.2003.00415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaban CD. Vestibular nucleus projections to the parabrachial nucleus in rabbits: implications for vestibular influences on the autonomic nervous system. Exp Brain Res. 1996;108:367–381. doi: 10.1007/BF00227260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaban CD. Neural substrates linking balance control and anxiety. Physiol Behav. 2002;77:469–475. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(02)00935-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao X, Wiedner EB, Altschuler SM. Transynaptic localization of pharyngeal premotor neurons in rat. Brain Res. 1995;696:246–249. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00817-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron TH, Richter JE, Singh S, Tennyson GS, Andres JM. Unusual presentation of mucosal hypersensitivity secondary to gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:289–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett RT, Bao X, Miselis RR, Altschuler SM. Brain stem localization of rodent esophageal premotor neurons revealed by transneuronal passage of pseudorabies virus. Gastroenterol. 1994;107:728–737. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90120-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman AL. The brainstem of the cat. The University of Wisconsin Press; Madison, WI: 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Boissonade FM, Davison JS. Effect of vagal and splanchnic nerve section on Fos expression in ferret brain stem after emetic stimuli. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:R228–R236. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.271.1.R228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boissonade FM, Sharkey KA, Davison JS. Fos expression in ferret dorsal vagal complex after peripheral emetic stimuli. Am J Phsyiol. 1994;266:R1118–R1126. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.266.4.R1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borison HL. Area postrema: chemoreceptor circumventricular organ of the medulla oblongata. Progress in Neurobiology. 1989;32:351–390. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(89)90028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle JT, Altschuler SM, Nixon TE, Tuchman DN, Pack AI, Cohen S. Role of the diaphragm in the genesis of lower esophageal sphincter pressure in the cat. Gastroenterology. 1985;88:723–730. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(85)90143-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bredenrood A, Smout J, Andre JPM. Physiology and pathologic belching. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:772–775. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broussard DL, Lynn RB, Wiedner EB, Altschuler SM. Solitarial premotor neuron projections to the rat esophagus and pharynx: implications for control of swallowing. Gastroenterol. 1998;114:1268–1275. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70433-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai YL, Ma WL, Guo JS, Li YQ, Wang LG, Wang WZ. Glutaminergic vestibular neurons express Fos after vestibular stimulation and project to the NTS and the PBN in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2007;417:132–137. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.01.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CL, Cook IJ. Proximal versus distal oesophageal motility as assessed by combined impedance and manometry. Dig Liver Dis. 2009;41:104–109. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collman PI, Tremblay L, Diamant NE. The central vagal efferent supply to the esophagus and lower esophageal sphincter of the cat. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:1430–1438. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90352-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crouch JE. Text-Atlas of cat anatomy. Lea and Febiger; Philadelphia: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Dean C, Seagard JL. Mapping of carotid baroreceptor subtype projections to the nucleus tractus solitarius using c-fos immunohistochemistry. Brain Res. 1997;758:201–208. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00245-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jonghe BC, Horn CC. Chemotherapy agent cisplatin induces 48-h Fos expression in the brain of a vomiting species, the house musk shrew (Suncus murinus) Am J Physiol. 2009;296:R902–R911. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90952.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerenziani S, Ribolsi M, Sifrim D, Blondeau K, Cicala M. Regional oesophageal sensitivity to acid and weakly acidic reflux in patients with non-erosive reflux disease. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21:253–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2008.01203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finley JC, Katz DM. The central organization of carotid body afferent projections to the brain stem of the rat. Brain Res. 1992;572:108–116. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90458-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frysak T, Zenker W, Kantner Afferent and efferent innervating of the rat esophagus. Anat Embryol. 1984;170:63–70. doi: 10.1007/BF00319459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal RK, Paterson WG. Handbook of Physiology. Part 2 Chapter 22. The American Physiological Society; 1989. Esophageal motility; pp. 865–908. [Google Scholar]

- Grant VL. Do conditioned taste aversions result from activation of emetic mechanisms? Psychopharmacology. 1987;93:405–415. doi: 10.1007/BF00207227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossi L, Ciccaglione AF, Travaglini N, Marzio L. Transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations and gastroesophageal reflux episode in healthy subject and GERD patients during 24 hours. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:815–821. doi: 10.1023/a:1010708602777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward LF, Felder RB. Peripheral chemoreceptor inputs to the parabrachial nucleus of the rat. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:R707–R714. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1995.268.3.R707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert H, Margaret MM, Saper CB. Connections of the parabrachial nucleus with the nucleus of the solitary tract and medullary reticular formation in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1990;293:540–580. doi: 10.1002/cne.902930404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holstege G, Graveland G, Bijker-Biemond C, Scuddeboom I. Location of motoneurons innervating soft palate, pharynx, and upper esophagus. Anatomical evidence for a possible swallowing center in the pontine reticular formation. Brain Behav Evol. 1983;23:47–62. doi: 10.1159/000121488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia HG, Rao ZR, Shi JW. An indirect projection from the nucleus of the solitary tract to the central nucleus of the amygdala via the parabrachial nucleus in the rat: a light and electron microscopic study. Brain Res. 1994;663:181–190. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91262-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalia M, Mesulam MM. Brain stem projections of sensory and motor components of the vagus complex in the cat: The cervical vagus and nodose ganglion. J Comp Neurol. 1980;193:435–465. doi: 10.1002/cne.901930210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz DM, Karten HJ. Visceral representation within the nucleus of the tractus solitarius in the pigeon, Columba livia. J Comp Neurol. 1983;218:42–73. doi: 10.1002/cne.902180104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang IM, Dean C, Medda BK, Aslam M, Shaker R. Differential activation of medullary vagal nuclei during different phases of swallowing in the cat. Brain Res. 2004;1014:145–163. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang IM, Haworth ST, Medda BK, Roerig DL, Forster HV, Shaker R. Airway responses to esophageal acidification. Am J Physiol. 2008;294:R211–R219. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00394.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang IM, Medda BK, Ren J, Shaker R. Characterization and mechanism of the pharyng-esophageal inhibitory reflex. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:G1127–G1136. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.275.5.G1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang IM, Medda BK, Shaker R. Mechanisms of reflexes induced by esophageal distension Am. J Physiol. 2001;281:G1246–G1263. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.5.G1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang IM, Sarna SK. Handbook of Physiology. Chapter 32. America Physiological Society; 1987. Motor and myoelectric activity associated with vomiting, regurgitation and nausea; pp. 1179–1198. [Google Scholar]

- Lang IM, Sarna SK, Dodds WJ. Pharyngeal, esophageal and proximal gastric responses associated with vomiting. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:G963–G972. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1993.265.5.G963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawn AM. The localization by means of electrical stimulation of the origin and path in the medulla oblongata of the motor fibers of the rabbit oesophagus. J Physiol. 1964;174:232–244. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1964.sp007484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy LE, Borison HL. Cisplatin-induced vomiting eliminated by ablation of the area postrema in cats. Cancer Treatment reports. 1984;68:401–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milla PJ. Reflux vomiting. Arch Dis Childhood. 1990;65:996–999. doi: 10.1136/adc.65.9.996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AD, Ruggiero DA. Emetic reflex arc revealed by expression of the immediate-early gene c-fos in the cat. J Neurosci. 1994;14:871–888. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-02-00871.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal RK, Holloway RH, Penajini R, Blackshaw LA, Dent J. Transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxation. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:601–610. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90351-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyaoka Y, Shingai T, Takahashi Y, Yamada Y. Responses of parabrachial nucleus neurons to chemical stimulation of posterior tongue in chorda tympani-sectioned rats. Neurosci Res. 1997;28:201–207. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(97)00044-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mungarndee SS, Lundy RF, Jr, Norgren R. Central gustatory lesions and learned taste aversions: unconditioned stimuli. Physiol Behav. 2006;87:542–551. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedringhaus M, Jackson PG, Evans SRT, Verbalis JG, Gillis RA, Sahibzada N. Dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus: a site for evoking simultaneous changes in crural diaphragm activity, lower esophageal sphincter pressure, and fundus tone. Am J Physiol. 2008;294:R121–R131. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00391.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oelschlager BK, Quiroga E, Isch JA, Cuenca-Abente F. Gastroesophageal and pharyngeal reflux detection using impedance and 24-hour pH monitoring in asymptomatic subjects: Defining and normal environment. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pompeiano O, d' Ascanio P, Centini C, Pompeiano M, Balaban E. Gene expression in rat Vestibular and reticular structures during and after space flight. Neurosci. 2002;114:135–155. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00202-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabin BM, Hunt WA, Bakarich AC, Chedester AL, Lee J. Angiotensin II-induced taste aversion learning in cats and rats and the role of the area postrema. Physiol Behav. 1986;36:1173–1178. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(86)90496-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray AP, Chebolu S, Darmani NA. Receptor-selective agonists induce emesis and Fos expression in the brain and enteric nervous system of the least shrew. Pharmacol Biochem and Behav. 2009;94:211–218. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossiter CD, Norman WP, Jain M, Hornby PJ, Benjamin S, Gillis RA. Control of lower esophageal sphincter pressure by two sites in dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:G899–G906. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1990.259.6.G899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sang Q, Goyal RK. Lower esophageal sphincter relaxation and activation of medullary neurons by subdiaphragmatic vagal stimulation in the mouse. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1600–1609. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.20234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott TR, Small DM. The role of the prarabrachial nucleus in taste processing and feeding. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2009;1170:372–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.03906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuai XW, Xie PY. Expression and localization of c-Fos and NOS in the central nervous system following esophageal acid stimulation in rats. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:2287–2291. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i15.2287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S, Richter JE, Bradley JE, Haile LA. The symptom index. Differential usefulness in suspected acid-related complaints of heartburn and chest pain. Dig Dis Sci. 1903;38:1402–1408. doi: 10.1007/BF01308595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suwanprathes P, Ngu M, Ing A, Hunt G, Seow F. C-Fos Immunoreactivity in the brain after esophageal acid stimulation. Am J Med. 2003;115:31S–38S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00190-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takakura CA, Santos MT, Menani JV, Campos RR, Colombari E. Commissural nucleus of the solitary tract is important for cardiovascular responses to caudal pressor area activation. Brain Res. 2007;1116:32–37. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.05.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trifan A, Shaker R, Ren J, Mittal RK, Saeian K, Dua K, Kusano M. Inhibition of resting lower esophageal sphincter pressure by pharyngeal water stimulation in humans. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:441–446. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90072-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wank M, Neuhuber WL. Local differences in vagal afferent innervation of the rat esophagus are reflected by neurochemical differences at the level of the sensory ganglia and by different brain stem projections. J Comp Neurol. 2001;435:41–59. doi: 10.1002/cne.1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]