Abstract

Objective To review trials of nurse led interventions for hypertension in primary care to clarify the evidence base, establish whether nurse prescribing is an important intervention, and identify areas requiring further study.

Design Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Data sources Ovid Medline, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, British Nursing Index, Cinahl, Embase, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, and the NHS Economic Evaluation Database.

Study selection Randomised controlled trials of nursing interventions for hypertension compared with usual care in adults.

Data extraction Systolic and diastolic blood pressure, percentages reaching target blood pressure, and percentages taking antihypertensive drugs. Intervention effects were calculated as relative risks or weighted mean differences, as appropriate, and sensitivity analysis by study quality was undertaken.

Data synthesis Compared with usual care, interventions that included a stepped treatment algorithm showed greater reductions in systolic blood pressure (weighted mean difference −8.2 mm Hg, 95% confidence interval −11.5 to −4.9), nurse prescribing showed greater reductions in blood pressure (systolic −8.9 mm Hg, −12.5 to −5.3 and diastolic −4.0 mm Hg, −5.3 to −2.7), telephone monitoring showed higher achievement of blood pressure targets (relative risk 1.24, 95% confidence interval 1.08 to 1.43), and community monitoring showed greater reductions in blood pressure (weighted mean difference, systolic −4.8 mm Hg, 95% confidence interval −7.0 to −2.7 and diastolic −3.5 mm Hg, −4.5 to −2.5).

Conclusions Nurse led interventions for hypertension require an algorithm to structure care. Evidence was found of improved outcomes with nurse prescribers from non-UK healthcare settings. Good quality evidence from UK primary health care is insufficient to support widespread employment of nurses in the management of hypertension within such healthcare systems.

Introduction

Essential hypertension is a major cause of cardiovascular morbidity.1 In 2003 the prevalence of hypertension in England was 32% in men and 30% in women.2 Since the prevalence of hypertension increases with age it is a growing public health problem in the Western world faced with ageing populations.3 The lowering of raised blood pressure in drug trials has been associated with a reduction in stroke of 35-40%, heart attack of 20-25%, and heart failure of over 50%.4 To achieve these benefits, aggressive and organised treatment to attain blood pressure targets is required, yet often contacts with health professionals do not trigger changes in antihypertensive therapy5; a phenomenon termed “clinical inertia.”6

Most patients require a combination of antihypertensive drugs to reach target blood pressure. Guidelines advocate logical drug combinations,7 and in England the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence has published a treatment algorithm for clinicians to follow.8 Hypertension is a condition almost entirely managed in primary care, and in the United Kingdom is an important component of the Quality and Outcomes Framework, which rewards practices for achievement of blood pressure standards set by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence.9 Achievement between practices, however, varies considerably10 and knowledge of guidelines among general practitioners does not necessarily translate into their implementation.11

Doubt persists about how best to organise effective care and interventions to control hypertension by the primary care team. In 2005 a Cochrane review classified 56 trials of interventions into six categories: self monitoring, education of patients, education of health professionals, care led by health professionals (nurses or pharmacists), appointment reminder systems, and organisational interventions. The review concluded that an organised system of regular review allied to vigorous antihypertensive drug therapy significantly reduced blood pressure and that a stepped care approach for those with blood pressure above target was needed.12 Nurse or pharmacist led care was suggested to be a promising way forward but required further evaluation. Another review found that appropriately trained nurses can produce high quality care and good health outcomes for patients, equivalent to that achieved by doctors, with higher levels of patient satisfaction.13 Nurse led care is attractive as it has been associated with stricter adherence to protocols, improved prescribing in concordance with guidelines, more regular follow-up, and potentially lower healthcare costs. Without associated changes in models of prescribing, however, there seems to be little effect on blood pressure level.14 At present the usual model of care is shared between general practitioners and practice nurses, with general practitioners prescribing. Our local survey of Devon and Somerset found that of 79 responding practices (n=182; response rate 43%) 53 were using this model, with only four using nurse led care, including nurse prescribing (unpublished observation). In the light of these uncertainties over models of care and whether blood pressure reduction with nurse led care can be achieved, we explored further the trial evidence for efficacy of nurse led interventions through a systematic review. To elucidate whether nurse prescribing is an important component of this complex intervention and to identify areas in need of further study, we reviewed the international evidence base for such an intervention and its applicability to primary care in the United Kingdom.

Methods

We searched the published literature for randomised controlled trials that included an intervention delivered by nurses, nurse prescribers, or nurse practitioners designed to improve blood pressure, compared with usual care. The population of interest was adults aged 18 or over with newly diagnosed or established hypertension above the study target, irrespective of whether or not they were taking antihypertensive drugs. Primary outcome measures were systolic and diastolic blood pressure at the end of the study, changes in systolic and diastolic blood pressure compared with baseline, percentage of patients reaching target blood pressure, and percentage taking antihypertensive drugs. The secondary outcome was cost or cost effectiveness of interventions.

Data sources and extraction

We searched Ovid Medline, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, British Nursing Index, Cinahl, Embase, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, and the NHS Economic Evaluation Database. Using a strategy modified from the previous review of 2005 we searched for randomised controlled trials in original English language and published between January 2003 and November 2009.12 We identified older citations from this review, hence the choice of cut-off date for the search (see web extra). We also corresponded with authors to identify missed citations.

Two authors (CEC, LFPS) independently selected potentially relevant studies by screening retrieved citations and abstracts. Trials assessed as definite or uncertain for inclusion were retrieved as full papers. Differences were resolved by discussion; arbitration from a third author (JLC) was planned but not required. Two authors (CEC, LFPS) independently extracted details of the studies and data using a standardised electronic form, with differences resolved by discussion. Risk of bias in the generation of the randomisation sequence, allocation concealment, and blinding (participants, carers, assessors) was assessed as adequate, uncertain, or inadequate using Cochrane criteria.15 One author (LFPS) checked the reference lists of all included studies for further potentially relevant citations, and two authors (CEC, LFPS) reviewed this list and agreed on further potentially relevant papers to retrieve in full. Searches were undertaken in June 2009 and repeated in November 2009 before final writing up.

Statistical analysis

Data were pooled and analysed using RevMan v5.0.16 We carried out separate analyses for each intervention and outcome measure compared with usual care. Intervention effects were calculated as relative risks with 95% confidence intervals for dichotomous data. For continuous data we used a conservative random effects meta-analysis model to calculate mean differences and weighted mean differences with 95% confidence intervals. When a study included more than one intervention group with a single comparator arm, we included both intervention groups and split the number of patients in the common comparator arm across the separate intervention arms.15 Where required we calculated standard deviations from standard errors or confidence intervals presented within papers. Heterogeneity was quantified using the I2 statistic and the χ2 test of heterogeneity. Using sensitivity analysis we explored heterogeneity by excluding single outlying results or restricting analysis to studies of good quality. We reported pooled data only when heterogeneity was not significant (P>0.05). Two authors (CEC, RST) reviewed the data from cluster randomised controlled trials and either extracted the data as presented when the authors were deemed to have taken account of cluster effects or first adjusted using a design factor,15 with intraclass correlation coefficients for systolic and diastolic blood pressure derived from cluster studies in primary care.17

Results

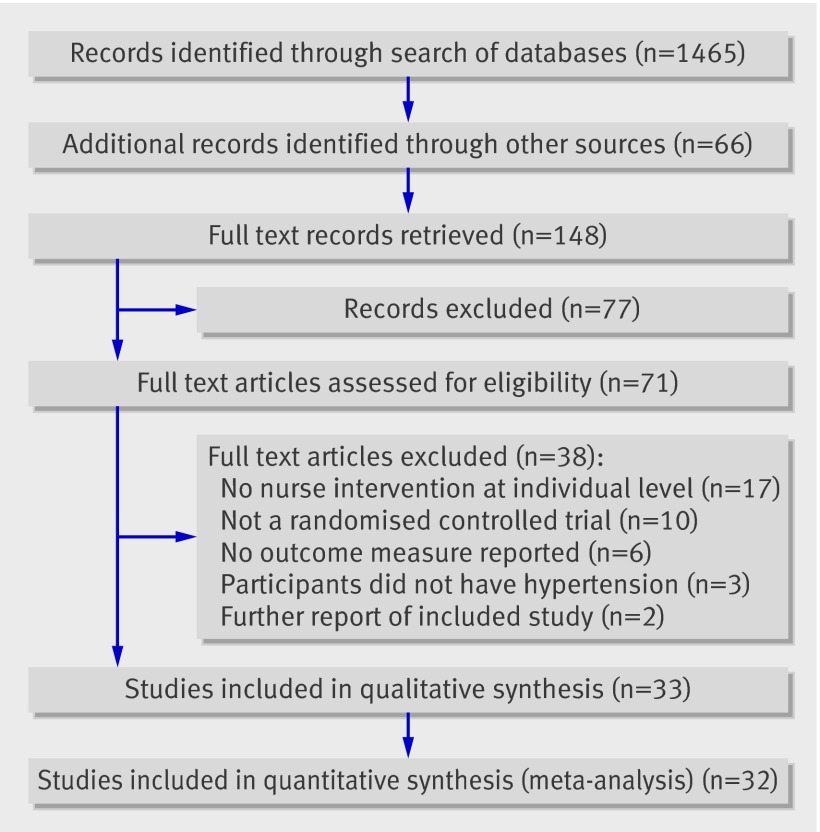

Searches identified 1465 potential citations. A further 66 potential studies were identified from citations in retrieved papers. After initial screening of the titles and abstracts 71 full studies were assessed for possible inclusion in the review and 33 met the inclusion criteria (fig 1).

Fig 1 Flow of papers through study

Included studies

Table 1 summarises the characteristics of the included studies. Seven cluster randomised controlled trials were randomised at practice18 19 20 21 22 23 or family level.24 Five described adjustment for clustering effects but two did not seem to have done so, therefore these were adjusted for cluster size.23 24 One study used a two level nested design of interventions at provider and patient level; combined patient level outcomes were extracted where possible, or as separate intervention and control groups for each provider intervention.25 Four studies had three arms. Three compared telephone monitoring and face to face nurse monitoring with usual care26 27 28 and outcomes were extracted as separate groups; one compared nurse and general practitioner interventions with usual care and only the nurse and control outcomes were extracted.21 The remaining randomised controlled trials were two armed studies randomised at individual patient level.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Study and setting | Study type (duration) | Participants | Sample size (intervention/controls) | Subgroups analysed | Interventions | Quality judgment* | Outcome measures extracted† | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artinian 2001,*26 family community centre, Detroit, USA | Pilot randomised controlled trial (three months) | African Americans aged >18 years with systolic blood pressure >140 mm Hg or diastolic 90 mm Hg (>130 mm Hg or >85 mm Hg if diabetes or previous myocardial infarction) | 6/6/9 | Telephone monitoring, community. monitoring, and ethnicity | Group 1: two nurse visits and then weekly telephone feedback to nurse on home blood pressure measurements (home telemonitoring plus usual care); group 2: 12 weekly nurse visits to feedback home blood pressure measurements (community monitoring plus usual care); group 3: usual doctor care with blood pressure measured twice with automated monitor (UA 767PC; A&D Medical, San Jose, CA, USA), five minutes apart after five minutes’ rest. Mean blood pressure recorded | Sequence generation adequate, allocation concealment unclear (not described), blinding adequate | Systolic and diastolic blood pressure | Systolic: group 1, 124.1 (SD 13.8) mm Hg; group 2, 142.3 (SD 12.1) mm Hg, group 3, 143.3 (SD 12.7) mm Hg. Diastolic: group 1, 75.65 (SD 11.4) mm Hg; group 2, 78.3 (SD 6.9) mm Hg; group 3, 89.1 (SD 10.6) mm Hg |

| Artinian 2007,*29 Detroit, USA | Randomised controlled trial (12 months) | African Americans aged >18 years with systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg or diastolic ≥90 mm Hg (>130 mm Hg or >80 mm Hg if diabetes or renal disease) | 167/169 | Telephone monitoring and ethnicity | Self monitoring blood pressure at home sent over telephone to nurse; trained nurse visited patient twice at home to teach about, deliver, and set up blood pressure equipment. When telephone data received, nurse telephoned patient about lifestyle and adherence to treatment. Blood pressure measured twice with automated monitor (HEM-737; Omron, Japan) after five minutes’ rest. Mean blood pressure recorded | Sequence generation adequate, allocation concealment adequate, blinding: adequate | Systolic and diastolic blood pressure | Systolic: 145.0 (SD 21.0) mm Hg for intervention, 148.1 (SD 22.3) mm Hg for control. Diastolic: 83.8 (SD 12.1) mm Hg for intervention, 83.5 (SD 13.6) mm Hg for control |

| Bebb 2007,18 42 general practices, Nottingham, England | Cluster randomised controlled trial; randomised at practice level (12 months) | People with type 2 diabetes aged 18-80, with blood pressure ≥140/90 mm Hg | 20/22 clusters, 797/737 participants | Algorithm | Treatment algorithm for management of hypertension in type 2 diabetes followed by practice nurses and general practitioners. Blood pressure measured twice with automated monitor (HEM-705CP; Omron, Japan) after five minutes’ rest, and repeated third time if >10% difference. Mean of last two readings recorded | Sequence generation adequate, allocation concealment adequate, blinding inadequate (could not blind clinicians to intervention) | Systolic and diastolic blood pressure; blood pressure target <140/80 mm Hg with treatment or <140/90 mm Hg; and proportion receiving treatment | Systolic: 143.0 (SD 19.5) mm Hg for intervention, 143.1 (SD 17.7) mm Hg for control. Diastolic: 78.2 (SD 10.2) mm Hg for intervention, 77.9 (SD 10.4) mm Hg for control. Target blood pressure: 272/743 for intervention, 232/677 for control. Treatment received: 526/743 for intervention, 471/677 for control |

| Becker 2005,24 Baltimore, USA | Cluster randomised controlled trial; randomised at family level (12 months) | African Americans aged 30-59. Siblings of probands with coronary heart disease aged <60 identified at admission | 92/102 clusters, 196/168 participants | Algorithm, community monitoring, nurse prescribing, and ethnicity | Group 1: community based care, in a non-healthcare setting, 30 minute sessions with blood pressure measurement and evaluation of treatment by nurse practitioner, and diet, exercise, and smoking counselling by community health worker. Nurse responsible for communicating changes of treatment and decisions on application of guidelines. Group 2: enhanced primary care (control), family physicians and patients given information from baseline assessment and same guidelines but left to usual care of family physician. Method of blood pressure measurement not described | Sequence generation adequate, allocation concealment adequate, blinding inadequate (could not blind nurse practitioners to delivery of community based care) | Systolic and diastolic blood pressure and use of antihypertensive drugs | Systolic: 130 (SD 14) mm Hg for intervention, 134 (SD 17) mm Hg for control. Diastolic: 84 (SD 9) mm Hg for intervention, 85 (SD 10) mm Hg for control. Antihypertensive drugs: 102/196 for intervention, 69/168 for control |

| Bellary 2008,19 21 general practices in Coventry and Birmingham, England | Cluster randomised controlled trial; randomised at practice level (24 months) | South Asian adults with type 2 diabetes | 9/12 clusters, 868/618 participants | Algorithm and ethnicity | Common treatment algorithms for control of blood pressure, diabetes, and lipid levels. Intervention group practice nurses received additional time (four hours per week) to run clinics and implement protocols, training in diabetes, and support from diabetes specialist nurses. All participants were supported by link workers able to provide interpretation and input in local languages. Method of blood pressure measurement not described | Sequence generation unclear (not described), allocation concealment unclear (not described), blinding inadequate (could not blind nurses to intervention) | Systolic and diastolic blood pressure, use of antihypertensive drugs, and blood pressure target 130/80 mm Hg, or 125/75 mm Hg if proteinuria present | Systolic: 134.3 (SD 21.1) mm Hg for intervention, 136.4 (SD 20.3) mm Hg for control. Diastolic: 78.4 (SD 11.0) mm Hg for intervention, 81.0 (SD 11.1) mm Hg for control. Antihypertensive drugs: 660/868 for intervention, 459/618 for control. Target blood pressure: 310/868 for intervention, 191/618 for control |

| Bosworth 2009,*25 primary care clinic, Durham, USA | Two level nested cluster randomised controlled trial; randomised at provider and patient level (24 months) | White (50%) or African American (43%) participants (98% men) with hypertension or taking antihypertensive drugs in previous 12 months | Group 1, 150/151; group 2, 144/143; pooled groups, 294/294 | Telephone monitoring | Providers randomised to decision support (group 1) or hypertension reminders (group 2). Their patients were randomised to nurse telephone support for behavioural change every two months (intervention) or usual care. Systolic blood pressure for patient telephone support versus usual care extracted for each group. Target achievement reported pooled across both groups. Blood pressure measurement by “trained clinic healthcare providers according to Veterans’ Affairs standards.” Clinic blood pressure readings used for study | Sequence generation adequate, allocation concealment adequate, blinding adequate | Systolic blood pressure and blood pressure target 140/90 mm Hg, or 135/85 mm Hg with diabetes | Systolic: group 1, 136.9 (SD 19.7) mm Hg for intervention, 136.8 (SD 20.8) mm Hg for control; group 2, 136.3 (SD 19.2) mm Hg for intervention, 136.8 (SD 19.1) mm Hg for control. Target blood pressure: 160/294 for intervention, 129/294 for control |

| Campbell 1998,39 Scotland | Randomised controlled trial (12 months) | Participants with known coronary heart disease | 593/580 | Nurse led clinic (primary care) | Nurse run blood pressure clinics with 2-6 monthly follow-up in accordance with British Hypertension Society guidelines (1993), and referral to general practitioner if treatment needed. Method of blood pressure measurement not described | Sequence generation adequate, allocation concealment adequate, blinding inadequate (nurses not blinded) | Blood pressure target <160/90 mm Hg and use of antihypertensive drugs | Target blood pressure: 524/573 for intervention, 475/559 for control. Antihypertensive drugs: 572/593 for intervention, 510/580 for control |

| Denver 2003,44 London, England | Randomised controlled trial (six months) | People with type 2 diabetes and hypertension (defined as blood pressure ≥140/80 mm Hg) and already receiving antihypertensive treatment | 59/56 | Nurse led clinic (secondary care), nurse prescribing, and ethnicity | Nurse led secondary care (outpatient) hypertension clinic. Blood pressure measured twice with automated monitor (Omron HEM-705CP, Japan) after five minutes’ rest according to British Hypertension Society guidelines. Second reading was used. Both arms checked and left arm used if no difference between arms | Sequence generation inadequate, alternate case randomisation, allocation concealment unclear (not described), blinding: inadequate (nurses and participants not blinded) | Systolic and diastolic blood pressure and blood pressure targets 140/80, or 120/70 mm Hg if renal impairment | 141.1 (SD 19.3) mm Hg for intervention, 151.0 (SD 21.9) mm Hg for control; 79.9 (SD 10.6) mm Hg for intervention, 82.2 (SD 12.4) mm Hg for control: 20/59 for intervention, 6/56 for control |

| Garcia- Pena 2001,*32 Mexico | Randomised controlled trial (six months) | Participants aged ≥60 with systolic blood pressure ≥160 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg at screening | 345/338 | Community monitoring | Group 1: regular nurse visits (fortnightly to monthly) at home to measure blood pressure, discuss lifestyle changes, and review drugs and adherence, plus usual physician care. Group 2: postal pamphlet about hypertension plus usual physician care. Blood pressure measured twice seated and once standing with mercury sphygmomanometer as per British Hypertension Society guidance | Sequence generation adequate, allocation concealment adequate, blinding: adequate | Systolic and diastolic blood pressure, reduction in systolic and diastolic blood pressure, use of antihypertensive drugs, and blood pressure target <160/90 mm Hg | Systolic: 155.1 (SD 17.3) mm Hg for intervention, 158.2 (SD 16.6) mm Hg for control. Diastolic: 87.4 (SD 8.6) mm Hg for intervention, 90.8 (SD 10.4) mm Hg for control. Reduction in systolic: −6.8 (SD 19.9) mm Hg for intervention, −3.5 (SD 20.2) mm Hg for control. Reduction in diastolic: −3.7 (SD 9.5) mm Hg for intervention, 0 (SD 11.3) mm Hg for control. Antihypertensive drugs: 290/345 for intervention, 247/338 for control. Target blood pressure: 125/345 for intervention, 22/338 for control |

| Guerra- Riccio 2004,4 Sao Paulo, Brazil | Randomised controlled trial (six months) | Participants with hypertension attending outpatient hypertension clinic | 48/52 | Nurse led clinic (secondary care) | Group 1: visited nurse clinic every 15 days for blood pressure measurement and reinforcement of adherence to therapy, plus usual three monthly physician care. Group 2: visited nurse clinic every 90 days for blood pressure measurement and reinforcement of adherence to therapy, plus usual three monthly physician care. Blood pressure measured three times supine with mercury sphygmomanometer as per National Committee on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (fifth report) guidance | Sequence generation unclear (not described), allocation concealment adequate, blinding inadequate (nurses and participants not blinded) | Reduction in systolic and diastolic blood pressure | Reduction in systolic: −36.0 (SD 41.6) mm Hg for intervention, −17.0 (SD 28.8) mm Hg for control. Reduction in diastolic: −21.0 (SD 27.7) mm Hg for intervention, −10.0 (SD 14.4) mm Hg for control |

| Hill 2003,*40 Baltimore, USA | Randomised controlled trial (36 months) | African American men aged 21-54 with blood pressure >140/90 mm Hg | 125/106 | Algorithm, nurse led clinic (primary care), nurse prescribing, and ethnicity | Group 1: comprehensive individualised intervention by nurse practitioner community health worker and physician. Nurse practitioner was visited every 1-3 months and treatment changed according to protocol based on National Committee on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (sixth report) guidelines. Group 2: referred to sources of hypertension care in community. Both groups received telephone reminders every six months and annual face to face reminders of importance of hypertension control, and education about benefits. Blood pressure measured using random zero sphygmomanometer three times at one minute intervals after five minutes seated. Mean of second and third measurements recorded | Sequence generation adequate, allocation concealment unclear (not described), blinding adequate | Systolic and diastolic blood pressure, reduction in systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and blood pressure target <140/90 mm Hg | Systolic: 139.3 (SD 22.2) mm Hg for intervention, 150.9 (SD 25.0) mm Hg for control. Diastolic: 89.3 (SD 15.8) mm Hg for intervention, 94.8 (SD 18.6) mm Hg for control. Reduction in systolic: −7.5 (SD 22.2) mm Hg for intervention, 3.4 (SD 25.0) mm Hg for control. Reduction in diastolic −10.1 (SD 15.8) mm Hg for intervention, −3.7 (SD 18.6) mm Hg for control. Target blood pressure: 55/125 for intervention, 33/106 for control |

| Jewell 1988,38 Southampton, England | Randomised controlled trial (12 months) | Patients aged 30-64 with new (diastolic blood pressure >100 mm Hg aged 30-39 or >105 mm Hg aged >40) or uncontrolled hypertension (diastolic blood pressure >95 mm Hg after three readings while receiving treatment) | 15/19 | Algorithm and nurse led clinic (primary care) | Nurse clinic with 15 minute appointments compared with usual general practitioners’ 10 minute appointments, implementing common protocol. Blood pressure measured using random zero sphygmomanometer | Sequence generation unclear (not described), allocation concealment inadequate (not concealed), blinding inadequate (nurse and doctor not blinded) | Target diastolic blood pressure ≤90 mm Hg | 10/15 for intervention, 12/19 for control |

| Jiang 2007,*33 Chengdu, China | Randomised controlled trial (six months) | Participants admitted to tertiary medical centres with angina or myocardial infarction | 83/84 | Community monitoring and ethnicity | 12 week home delivered cardiac rehabilitation programme based on American Heart Association 2000 secondary prevention guidelines setting goals for activity, diet, and blood pressure <140/90 mm Hg. Method of blood pressure measurement not described | Sequence generation adequate, allocation concealment adequate, blinding adequate | Systolic and diastolic blood pressure | Systolic: 129.8 (SD 12.1) mm Hg for intervention, 130.7 (SD 15.0) mm Hg for control. Diastolic: 78.3 (SD 8.6) mm Hg for intervention, 79.4 (SD 9.9) mm Hg for control |

| Jolly 1999,*20 Southampton, England | Cluster randomised controlled trial; randomised at practice level (12 months) | Participants with diagnosis of angina or myocardial infarction in district general hospitals | 33/34 clusters, 277/320 participants | Nurse led clinic (primary care) | Structured follow-up by practice nurses, trained and given ongoing telephone support by specialist cardiac liaison nurses. Method of blood pressure measurement not described | Sequence generation adequate, allocation concealment adequate, blinding unclear (not clear if research nurse aware of allocation status) | Systolic and diastolic blood pressure and use of antihypertensive drugs | Systolic: 136.9 (SD 19) mm Hg for intervention, 19.1 (SD 21) mm Hg for control. Diastolic: 83.7 (SD 13) mm Hg for intervention, 85.0 (SD 14) mm Hg for control. Antihypertensive drugs: 210/262 for intervention, 230/297 for control |

| Kastarinen 2002,41 eastern Finland | Open randomised controlled trial (two years) | Adults aged 25-74 with systolic blood pressure 140-179 mm Hg or diastolic 90-109 mm Hg or taking antihypertensive drugs | Group 1, 175/166; group 2, 185/189 | Nurse led clinic (primary care) | Visits to local public health nurses at 1, 3, 6, 9, 15, 18, and 21 months after randomisation, for systematic instruction in to change of individual health behaviours, with measurement of blood pressure and weight. Plus two group sessions at six and 18 months targeting reduction in salt intake and weight. Group 1: antihypertensive treatment compared with usual care. Group 2: no antihypertensive treatment compared with usual care. Blood pressure measured twice in right arm with mercury sphygmomanometer according to WHO MONICA protocol | Sequence generation adequate, allocation concealment inadequate, open allocation, blinding: inadequate (open study) | Reduction in systolic and diastolic blood pressure | Systolic: group 1, −6.0 (SD 17.3) mm Hg for intervention, −4.7 (SD 14.0) mm Hg for control; group 2, −2.0 (SD 11.5) mm Hg for intervention, 0.4 (SD 10.8) mm Hg for control. Diastolic: group 1, −3.8 (SD 8.7) mm Hg for intervention, −3.7 (SD 8.1) mm Hg for control; group 2, −2.4 (SD 6.7) mm Hg for intervention, −0.4 (SD 6.6) mm Hg for control |

| Ko 2004,*46 Hong Kong | Randomised controlled trial (12 months) | People with type 2 diabetes and haemoglobin A1c >8%, recruited from three regional diabetes centres | 90/88 | Nurse led clinic (secondary care) and ethnicity | Thirty minute educational sessions delivered by diabetes education nurses directly after each physician appointment, with five visits per participant during study period. Method of blood pressure measurement not described | Sequence generation adequate, allocation concealment unclear (not described), blinding adequate | Systolic and diastolic blood pressure and use of antihypertensive drugs | Systolic: 139 (SD 21) mm Hg for intervention, 138 (SD 19) mm Hg for control. Diastolic: 76 (SD 11) mm Hg for intervention, 77 (SD 10) mm Hg for control. Antihypertensive drugs: 61/90 for intervention, 60/88 for control |

| Lee 2007,*34 Taiwan, China | Randomised controlled trial (six months) | People aged ≥60 with known hypertension (defined as systolic blood pressure 140-179 mm Hg) | 91/93 | Community monitoring and ethnicity | Community based walking intervention delivered by public health nurse, with telephone and face to face support, to motivate frequency and time spent walking. Blood pressure measured three times with mercury sphygmomanometer as per National Committee on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (fifth report) guidance | Sequence generation adequate, allocation concealment adequate, blinding adequate | Systolic and diastolic blood pressure and reduction in systolic and diastolic blood pressure | Systolic: 136.2 (SD 16.7) mm Hg for intervention, 143.6 (SD 15.3) mm Hg for control. Diastolic: 76.7 (SD 12.3) mm Hg for intervention, 75.7 (SD 11.6) mm Hg for control. Reduction in systolic: −15.4 (SD 9.5) mm Hg for intervention, −8.4 (SD 15.8) mm Hg for control. Reduction in diastolic: −6.5 (SD 9.5) mm Hg for intervention, −4.7 (SD 8.5) mm Hg for control |

| Litaker 2003,47 Cleveland, Ohio, USA | Randomised controlled trial (12 months) | People with type 2 diabetes and established hypertension (defined as stage 1 or 2, JNC 1993 guidelines) recruited from tertiary centre | 79/78 | Algorithm, nurse led clinic (secondary care), and nurse prescribing | Nurse practitioner run clinics in hospital using treatment algorithms based on guidance from American Diabetes Association and for blood pressure, National Committee on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (1997) and UKPDS (1998). Method of blood pressure measurement not described | Sequence generation unclear (not described), allocation concealment unclear (not described), blinding inadequate (participants and nurses not blinded) | Blood pressure target 130/85 mm Hg | 9/79 for intervention, 8/78 for control |

| Logan 1979,35 Toronto, Canada | Randomised controlled trial (six months) | Participants aged 18-69 with diastolic blood pressure ≥95 or 90-94 mm Hg with systolic blood pressure >140 mm Hg not receiving treatment, selected from voluntary workplace based screening | 206/204 | Algorithm, community monitoring, and nurse prescribing | Nurses in workplace managed blood pressure according to structured protocol with treatment algorithm. Blood pressure measured three times after five minutes seated | Sequence generation unclear (not described), allocation concealment unclear (not described), blinding adequate | Diastolic blood pressure, reduction in diastolic blood pressure, blood pressure target (diastolic blood pressure <90 or >5 mm Hg fall if diastolic blood pressure ≤95 at entry), and use of antihypertensive drugs | Diastolic: 90.3 (SD 7.2) mm Hg for intervention, 94.3 (SD 8.6) mm Hg for control. Reduction in diastolic: −9.9 (SD 8.6) mm Hg for intervention, −6.1 (SD 8.6) mm Hg for control. Target blood pressure: 100/206 for intervention, 56/204 for control. Antihypertensive drugs: 177/206 for intervention, 108/204 for control |

| McHugh 2001, 50 Glasgow, Scotland | Randomised controlled trial (mean eight months) | Patients added to coronary artery bypass waiting list | 49/49 | Nurse led clinic (primary care), community monitoring | Monthly health education sessions delivered alternately at home by cardiac liaison nurses and in general practices by practice nurses. Multiple risk factors addressed with behavioural change models and blood pressure assessed against Joint British Societies guidelines (1998) with reference to general practitioner if change to treatment needed. Mean of two blood pressure measurements recorded in accordance with British Heart Society guidelines | Sequence generation unclear (not described), allocation concealment unclear (not described), blinding inadequate (practices invited to deliver intervention) | Systolic and diastolic blood pressure and systolic blood pressure target <140 mm Hg | Systolic: 126.2 (SD 13.5) mm Hg for intervention, 138.9 (SD 16.5) mm Hg for control. Diastolic: 69.2 (SD 8.5) mm Hg for intervention, 74.6 (SD 10.7) mm Hg for control. Target blood pressure: 36/49 for intervention, 22/49 for control |

| McLean 2008,36 Edmonton, Alberta, Canada | Randomised controlled trial (24 weeks) | Adults aged ≥18 with type 1 or type 2 diabetes and blood pressure >130/80 mm Hg at two visits two weeks apart | 115/112 | Community monitoring | Nurse and pharmacist teams at pharmacies delivered cardiovascular risk reduction education with documentation of blood pressure and support materials. Blood pressure readings and suggestions for change according to Canadian hypertension education programme guidelines faxed to primary care physician, and participants encouraged to see physician. Participants were seen by nurse-pharmacist team every six weeks. Blood pressure measured by Bp-Tru monitor (Coquitlam, Canada) as mean of five readings taken one minute apart | Sequence generation adequate, allocation concealment adequate, blinding inadequate (not blinded) | Reduction in systolic blood pressure, use of antihypertensive drugs, and blood pressure target <130/80 mm Hg | Reduction in systolic: −10.1 (SD 21.2) mm Hg for intervention, −5.0 (SD 21.9) mm Hg for control. Antihypertensive drugs: 76/115 for intervention, 81/112 for control. Blood pressure target: 54/115 for intervention, 37/112 for control |

| Moher 2001,21 21 general practices in Warwickshire, England | Cluster randomised controlled trial; randomised at practice level (18 months) | Participants aged 55-75 with established coronary heart disease identified from practice records | 7/7 clusters, 665/559 participants | Algorithm, nurse led clinic (primary care) | Group 1: patients recalled to nurse clinic running agreed secondary prevention protocols. Nurses supported by nurse facilitator. Group 2: general practitioners agreed secondary prevention guidelines supported by investigator (not extracted), Group 3: usual care; practices received no further support after audit feedback. Method of blood pressure measurement not described | Sequence generation adequate, allocation concealment adequate, blinding inadequate (practices could not be blinded) | Use of antihypertensive drugs and blood pressure target <160/100 mm Hg | Antihypertensive drugs: 439/665 for intervention, 391/559 for control. Target blood pressure: 555/641 for intervention, 394/478 for control (group 1 intervention compared with group 3 usual care) |

| Mundinger 2000*42 New York, USA | Randomised controlled trial (six months) | Hypertensive subgroup in study of nurse practitioner compared with physician run primary care clinics | 211/145 | Not included in meta-analyses | Allocation to usual nurse practitioner or usual family physician care. Method of blood pressure measurement not described | Sequence generation adequate, allocation concealment adequate, blinding unclear if nurses were blinded | Systolic and diastolic blood pressure | Systolic: 137 mm Hg for intervention, 139 mm Hg for control (no standard deviation reported). Diastolic: 82 mm Hg for intervention, 85 mm Hg for control (no standard deviation reported) |

| New 2003*48 Salford, England | Randomised controlled trial (12 months) | People with diabetes recruited at annual hospital review, if blood pressure ≥140 or ≥80 mm Hg | 506/508 | Algorithm, nurse led clinic (secondary care), and nurse prescribing | Specialist nurse clinics attended every four to six weeks until target achieved; advice on lifestyle given, and treatment changes by protocol in accordance with British Heart Society 1999 guidelines. Blood pressure measured three times at one minute intervals with automated monitor (HEM-705CP Omron, Japan). Mean of last two readings recorded | Sequence generation adequate, allocation concealment adequate, blinding adequate | Reduction in systolic and diastolic blood pressure and blood pressure target <140/80 mm Hg | Reduction in systolic: −2.0 (SD 29.2) mm Hg for intervention, control not reported. Reduction in diastolic: −0.8 (SD 16.0) mm Hg for intervention, control not reported. Target blood pressure: 315/506 for intervention, 261/508 for control |

| New 2004*22 Salford, England | Cluster randomised controlled trial; randomised at practice level (12 months) | People with diabetes and blood pressure >140/80 mm Hg | 2474/2531 | Algorithm and nurse led clinic (primary care) | Practice nurses and general practitioners visited by specialist diabetes care nurses, with support materials to refresh local diabetes protocols and targets, and list of patient poorly controlled at last annual review. Method of blood pressure measurement not described | Sequence generation adequate, allocation concealment adequate, blinding adequate | Reduction in systolic and diastolic blood pressure and blood pressure target <140/80 mm Hg | Reduction in systolic: −0.2 (SD 34.3 mm Hg for intervention, control not reported. Reduction in diastolic: −0.1 (SD 11.4) mm Hg for intervention, control not reported. Target blood pressure: 1192/2474 for intervention, 1212/2531 for control |

| O’Hare 2004,23 West Midlands, England | Cluster randomised controlled trial; randomised at practice level (12 months) | South Asian people with type 2 diabetes and either raised blood pressure (>140 or >80 mm Hg) or haemoglobin A1c >7 or total cholesterol >5.0 | 3/3 cluster, 165/160 participants | Algorithm and nurse led clinic (primary care) | Enhanced care with Asian link workers, an additional practice nurse session per week, and community diabetic nurse support working to local protocols. Method of blood pressure measurement not described | Sequence generation adequate, allocation concealment adequate, blinding inadequate (practice not blinded) | Reduction in systolic and diastolic blood pressure and use of antihypertensive drugs | Reduction in systolic: −6.7 (SD 21.2) mm Hg for intervention, −2.1 (SD 17.5) mm Hg for control. Reduction in diastolic: −3.1 (SD 10.6) mm Hg for intervention, 0.3 (SD 10.0) mm Hg for control. Antihypertensive drugs: 56/165 for intervention, 40/160 for control |

| Rudd 2004*30 Stanford, California, USA | Randomised controlled trial (six months) | Participants with mean blood pressure ≥150/95 mm Hg after two screening visits at least one week apart | 69/68 | Algorithm, telephone monitoring, and nurse prescribing | Nurse instructed participants in use of automated home blood pressure monitor, followed up with telephone calls at one week and one, two, and four months, and changed doses of drugs (or initiated new drug in consultation with physician) according to management algorithm based on National Committee on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (sixth report) guideline. Blood pressure measured at home twice daily with automated monitor (UA 751, A&D Medical, San Jose, CA, USA), posted to nurse each fortnight | Sequence generation adequate, allocation concealment adequate, blinding adequate | Reduction in systolic and diastolic blood pressure and use of antihypertensive drugs | Reduction in systolic: −14.2 (SD 17.2) mm Hg for intervention, −5.7 (SD 18.7) mm Hg for control. Reduction in diastolic: −6.5 (SD 10.0) mm Hg for intervention, −3.4 (SD 8.0) mm Hg for control. Antihypertensive drugs: 66/69 for intervention, 53/68 for control |

| Schroeder 200543 Bristol, England | Randomised controlled trial (six months) | Participants with uncontrolled hypertension defined as ≥150 or ≥90 mm Hg | 110/94 | Nurse led clinic (primary care) | Nurse delivered session on adherence support (20 minutes) with follow-up session (10 minutes) after two months. Method of blood pressure measurement not described | Sequence generation adequate, allocation concealment adequate, blinding inadequate (nurses not blinded) | Systolic and diastolic blood pressure | Systolic: 142.9 (SD 17.6) mm Hg for intervention, 147.7 (SD 20.9) mm Hg for control. Diastolic: 80.4 (SD 10.1) mm Hg for intervention, 79.9 (SD 9.7) mm Hg for control |

| Taylor 200331 Santa Clara, California, USA | Randomised controlled trial (12 months) | People with diabetes aged ≥18, with haemoglobin A1c >10% and one of hypertension, dyslipidaemia, or cardiovascular disease | 61/66 | Algorithm, telephone monitoring, and nurse prescribing | 90 minute meeting with nurse to review care and develop self management programme, 1-2 hour group sessions weekly for four weeks, then follow-up telephone calls until 52 weeks. Nurse care managers used treatment algorithms for diabetic blood pressure and lipid treatment according to national guidelines (American Diabetes Association 2000). Blood pressure measured with a “standardised mercury sphygmomanometer and protocol” | Sequence generation unclear (not described), allocation concealment unclear (not described), blinding adequate | Systolic and diastolic blood pressure and blood pressure target <130 mm Hg systolic | Systolic: 130.9 (SD 14.8) mm Hg for intervention, 137.1 (SD 19.5) mm Hg for control. Diastolic: 75.5 (SD 10.9) mm Hg for intervention, 74.2 (SD 12.2) mm Hg for control. Target blood pressure: 32/61 for intervention, 28/66 for control |

| Tobe 2006,37 Canada | Randomised controlled trial (12 months) | “First nations” American Indian people ≥aged 18 with type 2 diabetes and hypertension (blood pressure >130/80 mm Hg) | 48/47 | Algorithm, community monitoring, and nurse prescribing | Home care nurse delivered structured advice on lifestyle and nurse managed, changed drugs for hypertension according to local protocol, and encouraged adherence. Nurse follow-up appointments at six weeks and three, six, nine, and 12 months. Blood pressure measured with BpTRU (Coquitlam, Canada) automated oscillometric cuff after seated for 30 minutes | Sequence generation adequate, allocation concealment adequate, blinding inadequate (open study) | Reduction in systolic and diastolic blood pressure | Reduction in systolic: −24.0 (SD 13.5) mm Hg for intervention, −17.0 (SD 18.6) mm Hg for control. Reduction in diastolic: −11.6 (SD 10.6) mm Hg for intervention, −6.8 (SD 11.1) mm Hg for control |

| Tonstad 2007,49 Oslo; Norway | Randomised controlled trial (six months) | Adults aged 30-69 with hypertension (systolic blood pressure 140-169 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure 90-99 mm Hg) recruited from Oslo Health Study | 147/143 | Nurse led clinic (secondary care) | Initial 60 minute session and subsequent monthly 30 minute sessions with nurse promoting lifestyle behaviours according to individual risk profile, based on behavioural self management seven stages of change model. Blood pressure measured after five minutes seated | Sequence generation adequate, allocation concealment unclear (not described), blinding inadequate (nurse not blinded) | Systolic and diastolic blood pressure | Systolic: 147 (SD 9) mm Hg for intervention, 143 (SD 10) mm Hg for control. Diastolic: 91 (SD 8) mm Hg for intervention, 92 (SD 8) mm Hg for control |

| Woollard 1995,28 Perth, Australia | Randomised controlled trial (18 weeks) | Treated hypertensive patients recruited in primary care | 52/46/48 | Telephone monitoring (group 1) and nurse led clinic (primary care) (group 2) | Group 1: single face to face 15 minute session discussing risk factors, supported by educational manual, followed by five 15 minute telephone counselling sessions. Group 2: as group 1 but given six 45 minute face to face sessions instead. Group 3: usual care. Blood pressure was mean of three measurements at three minute intervals after being seated for 10 minutes with automated monitor (DINAMAP 1846SX; GE Healthcare, UK) | Sequence generation unclear (not described), allocation concealment unclear (not described), blinding inadequate (nurse and participants not blinded) | Reduction in systolic and diastolic blood pressure | Reduction in systolic: group 1, −6.0 (SD 25.8) mm Hg; group 2, −8.0 (SD 31.1) mm Hg; group 3, −4.0 (SD 16.8) mm Hg. Reduction in diastolic: group 1, −1.0 (SD 10.9) mm Hg; group 2, −2.0 (SD 8.7) mm Hg; group 3, 1.0 (SD 8.8) mm Hg |

| Woollard 2003 27 Perth, Australia | Randomised controlled trial with block randomisation (12 months) | Adults aged 20-75 with hypertension (defined as systolic >140 mm Hg or diastolic >90 mm Hg while receiving treatment), or with type 2 diabetes or coronary heart disease, recruited from general practices | 49/54/57 | Telephone monitoring (group 1) and nurse led clinic (primary care) (group 2) | Group 1: initial face to face session discussing risk factors, followed by monthly 10-15 minute telephone consultations for one year. Group 2: counselled in face to face monthly sessions lasting up to one hour, for one year. Group 3: usual care. Blood pressure measured with automated monitor (DINAMAP 1846 SX/P; GE Healthcare, UK) every two minutes for 10 minutes after resting seated for five minutes | Sequence generation unclear (not described), allocation concealment unclear (not described), blinding: adequate | Reduction in systolic and diastolic blood pressure and blood pressure target <130/85 mm Hg | Reduction in systolic: group 1, −0.9 (SD 11.5) mm Hg; group 2, −3.1 (SD 10.0) mm Hg; group 3, 0.2 (SD 15.9) mm Hg. Reduction in diastolic: group 1, −2.0 (SD 8.7) mm Hg; group 2, −1.8 (SD 8.7) mm Hg; group 3, −0.7 (SD 8.0) mm Hg. Target blood pressure: group 1, 26/49, group 2, 33/54, group 3, 24/57 |

WHO MONICA=World Health Organization Monitoring Trends and Determinants in Cardiovascular Disease ; UKPDS= United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study.

*Good quality studies.

Interventions were categorised as nurse support delivered by either telephone (seven studies),25 26 27 28 29 30 31 community monitoring (defined as home or other non-healthcare setting; eight studies),24 26 32 33 34 35 36 37 or nurse led clinics. These were held in either primary care (13 studies)20 21 22 23 27 28 35 38 39 40 41 42 43 or secondary care (six studies).44 45 46 47 48 49 One study used alternate sessions with nurses at home and in general practice.50 Fourteen studies included a stepped treatment algorithm18 19 21 22 23 24 30 31 35 37 38 40 47 48 and nine included nurse prescribing in their protocol.24 30 31 35 37 40 44 47 48

Although most of the studies recruited participants with hypertension, 11 also recruited participants with diabetes,18 19 22 23 31 36 37 44 46 47 48 five with coronary heart disease,20 21 33 39 50 and one the siblings of patients with coronary heart disease.24 Most studies recruited predominantly white participants. Four studied hypertension care provided to African Americans,24 26 29 40 three to Chinese,33 34 46 two to South Asians,19 23 one to American Indians,37 and two to mixed non-white populations.44 45 Thirty eight studies were excluded after review of the full paper (fig 1).

Risk of bias in included studies

Overall, study quality was moderate; random sequence generation was adequate in 70% (23/33) of studies, allocation concealment in 58% (19/33), and blinding of data collection in 43% (14/33); one study was described as an open (unblinded) randomised controlled trial.41 Thirteen studies were assessed as adequate in two of the three domains and adequate or unclear for the third.20 22 25 26 29 30 32 33 34 40 42 46 48 These studies were defined as of “good quality” and were used for sensitivity analysis by study quality. Only three of these reported UK trials; one of patients with ischaemic heart disease and hypertension20 and two of people with diabetes and hypertension.22 48 The method of blood pressure measurement was not described in 12 studies,19 20 21 22 23 24 33 39 42 43 46 47 10 used automated monitors,18 26 27 28 29 30 36 37 44 48 and seven referred to authoritative guidelines for measurement.25 32 34 41 44 45 50

Effects of interventions

Pooling of data across different types of interventions was limited by noticeable statistical heterogeneity between studies, which was not explained by restriction to good quality studies. Consequently the results are presented as subgroup analyses by type of intervention (table 2). (See web extra for forest plots for all comparisons; summary statistics were omitted if significant heterogeneity was present; see table 2). One study did not report any estimates of variance and did not contribute data to the meta-analyses.42

Table 2.

Summary of meta-analyses of studies using nurse led interventions to manage hypertension. Values are for weighted mean differences unless stated otherwise

| Study characteristics | Good quality studies | All studies | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (95% CI) | Heterogeneity* | Mean (95% CI) | Heterogeneity* | ||

| Use of algorithm: | |||||

| SBP at follow-up | NR (n=1) | NR | NR (n=5) | P=0.003; I²=75% | |

| DBP at follow-up | NR (n=1) | NR | NR (n=6) | P<0.001; I²=83% | |

| Change in SBP (mm Hg) from baseline | −9.7 (−14.0 to −5.4) (n=2) | P=0.58; I²=0% | −8.2 (−11.5 to −4.9) (n=4) | P=0.66; I²=0% | |

| Change in DBP (mm Hg) from baseline | −4.3 (−7.4 to −1.2) (n=2) | P=0.23; I²=30% | NR (n=5) | P<0.001; I²=88% | |

| Achievement of study blood pressure target (relative risk) | 1.09 (0.93 to 1.27) (n=3) | P=0.12; I²=53% | NR (n=10) | P=0.006; I²=61% | |

| Use of antihypertensive drugs (relative risk) | NR (n=1) | NR | NR (n=6) | P<0.001; I²=91% | |

| Nurse led clinics in primary care: | |||||

| SBP at follow-up | NR (n=2) | P=0.008; I²=86% | NR (n=4) | P=0.004; I²=77% | |

| DBP at follow-up | −2.9 (−6.9 to 1.1) (n=2) | P=0.10; I²=63% | NR (n=4) | P=0.03; I²=66% | |

| Change in SBP from baseline (WMD) | NR (n=1) | NR | −3.5 (−5.9 to −1.1) (n=6) | P=0.16; I²=36% | |

| Change in DBP from baseline | NR (n=1) | NR | −1.9 (−3.4 to −0.5) (n=6) | P=0.12; I²=43% | |

| Achievement of study blood pressure target (relative risk) | 1.14 (0.83 to 1.57) (n=2) | P=0.06; I²=72% | NR (n=7) | P=0.02; I²=61% | |

| Use of antihypertensive drugs (relative risk) | NR (n=1) | NR | NR (n=4) | P<0.001; I²=90% | |

| Nurse led clinics in secondary care: | |||||

| SBP at follow-up | NR (n=1) | NR | NR (n=3) | P=0.01; I²=76% | |

| DBP at follow-up | NR (n=1) | NR | −1.4 (−3.6 to 0.86) (n=3) | P=0.88; I²=0% | |

| Change in SBP from baseline | NR (n=0) | NR | NR (n=1) | NR | |

| Change in DBP from baseline | NR (n=0) | NR | NR (n=1) | NR | |

| Achievement of study blood pressure target (relative risk) | NR (n=1) | NR | 1.47 (0.79 to 2.74) {3} | P=0.06; I²=65% | |

| Use of antihypertensive drugs (relative risk) | NR (n=1) | NR | NR (n=1) | NR | |

| Nurse prescribing: | |||||

| SBP at follow-up | NR (n=1) | NR | −7.2 (−10.9 to −3.5) (n=4) | P=0.14; I²=45% | |

| DBP at follow up | NR (n=1) | NR | NR (n=5) | P=0.03; I²=63% | |

| Change in SBP from baseline | −9.7 (−14.0 to −5.4) (n=2) | P=0.58; I²=0% | −8.9 (−12.5 to −5.3) (n=3) | P=0.69; I²=0% | |

| Change in DBP from baseline | −4.3 (−7.4 to −1.2) (n=2) | P=0.23; I²=30% | −4.0 (−5.3 to −2.7) (n=4) | P=0.66; I²=0% | |

| Achievement of study blood pressure target (relative risk) | 1.20 (0.96 to 1.50) (n=2) | P=0.24; I²=27% | NR (n=6) | P=0.04; I²=57% | |

| Use of antihypertensive drugs (relative risk) | NR (n=1) | NR | NR (n=3) | P=0.01; I²=78% | |

| Telephone monitoring: | |||||

| SBP at follow-up | −2.9 (−7.5 to 1.6) (n=4) | P=0.05; I²=62% | −3.5 (−7.4 to 0.4) (n=5) | P=0.05; I²=58% | |

| DBP at follow-up | NR (n=2) | P=0.02; I²=81% | −1.1 (−5.8 to 3.6) (n=3) | P=0.06; I²=65% | |

| Change in SBP from baseline | NR (n=1) | NR | −3.9 (−8.9 to 1.0) (n=3) | P=0.17; I²=44% | |

| Change in DBP from baseline | NR (n=1) | NR | −2.1 (−4.1 to −0.3) (n=3) | P=0.72; I²=0% | |

| Achievement of study blood pressure target (relative risk) | NR (n=1) | NR | 1.24 (1.08 to 1.43) (n=3) | P=1.00; I²=0% | |

| Use of antihypertensive drugs (relative risk) | NR (n=1) | NR | NR (n=1) | NR | |

| Community monitoring: | |||||

| SBP at follow-up | −3.4 (−6.1 to −0.7) (n=4) | P=0.21; I²=33% | NR (n=6) | P=0.03; I²=60% | |

| DBP at follow-up | NR (n=4) | P=0.02; I²=69% | NR (n=7) | P=0.01; I²=64% | |

| Change in SBP from baseline | −4.8 (−8.3 to −1.2) (n=2) | P=0.18; I²=44% | −4.8 (−7.0 to −2.7) (n=4) | P=0.51; I²=0% | |

| Change in DBP from baseline | −3.1 (−4.8 to −1.3) (n=2) | P=0.22; I²=33% | −3.5 (−4.5 to −2.5) (n=4) | P=0.54; I²=0% | |

| Achievement of study blood pressure target (relative risk) | NR (n=1) | NR | NR (n=4) | P<0.001; I²=90% | |

| Use of antihypertensive drugs (relative risk) | NR (n=1) | NR | NR (n=4) | P<0.001; I²=90% | |

| Ethnic minority analyses | |||||

| SBP at follow-up: | |||||

| African American | −7.8 (−14.6 to −0.9) (n=4) | P=0.05; I²=63% | −6.3 (−10.7 to −1.9 (n=5) | P=0.06; I²=56% | |

| Chinese | −2.6 (−7.5 to 2.3) (n=3) | P=0.04; I²=68% | −2.6 (−7.5 to 2.3) (n=3) | P=0.04; I²=68% | |

| Pooled minority groups | NR (n=7) | P=0.009; I²=65% | NR (n=10) | P=0.009; I²=59% | |

| DBP at follow-up: | |||||

| African American | NR (n=4) | P=0.02; I²=71% | NR (n=5) | P=0.03; I²=62% | |

| Chinese | −0.5 (−2.3 to 1.3) (n=3) | P=0.61; I²=0% | −0.5 (−2.3 to 1.3) (n=3) | P=0.61; I²=0% | |

| Pooled minority groups | −1.7 (−3.9 to 0.6) (n=7) | P=0.06; I²=51% | −1.7 (−3.0 to −0.4) (n=10) | P=0.07; I²=43% | |

| Change in SBP from baseline: | |||||

| African American | NR (n=1) | NR | NR (n=1) | NR | |

| Chinese | NR (n=1) | NR | NR (n=1) | NR | |

| Mixed non-white | NR (n=0) | NR | −17.1 (−29.5 to −4.8) (n=2) | P=0.59; I²=0% | |

| Pooled minority groups | −8.4 (−12.0 to −4.7) (n=2) | P=0.32; I²=1% | −8.1 (−11.0 to −5.2) (n=6) | P=0.53; I²=0% | |

| Change in DBP from baseline: | |||||

| African American | NR (n=1) | NR | NR (n=1) | NR | |

| Chinese | NR (n=1) | NR | NR (n=1) | NR | |

| Mixed non-white | NR (n=0) | NR | −7.9 (−16.3 to 0.6) (n=2) | P=0.26; I²=21% | |

| Pooled minority groups | −3.7 (−8.2 to 0.7) (n=2) | P=0.08; I²=67% | −4.1 (−6.4 to −1.8) (n=6) | P=0.27; I²=22% | |

| Achievement of study blood pressure target (relative risk): | |||||

| Pooled minority groups | NR (n=1) | NR | NR (n=3) | P=0.04; I²=68% | |

| Use of antihypertensive drugs (relative risk) | |||||

| South Asian | NR (n=0) | NR | 1.22 (0.90 to 1.65) (n=2) | P=0.22; I²=34% | |

| Pooled minority groups | NR (n=1) | NR | 1.22 (1.02 to 1.47) (n=4) | P=0.33; I²=12% | |

SBP=systolic blood pressure; DBP=diastolic blood pressure; NR=not reported as pooling not undertaken due to significant heterogeneity or absence of data.

*P value from χ2 test.

Use of a treatment algorithm

Fourteen studies included a stepped treatment algorithm in their intervention18 19 21 22 23 24 30 31 35 37 38 40 47 48 and for nine it was the main focus of the intervention.18 19 21 22 35 37 38 47 48 Two studies of good quality30 40 showed greater magnitudes of reductions in blood pressure with the use of an algorithm compared with usual care: weighted mean difference, systolic −9.7 mm Hg (95% confidence interval −14.0. to −5.4 mm Hg) and diastolic −4.3 mm Hg (−7.4 to −1.2 mm Hg). Pooling of all four studies also showed a greater magnitude of reduction in systolic blood pressure (−8.2 mm Hg, −11.5 to −4.9; fig 2)23 30 37 40 with the use of an algorithm compared with usual care.

Fig 2 Change in systolic blood pressure with nurse led use of algorithm compared with usual care

Pooling of three good quality studies22 40 48 showed no significant difference in achievement of study blood pressure targets in favour of an intervention including an algorithm (relative risk 1.09, 95% confidence interval 0.93 to 1.27). Although a total of 10 studies reported this outcome,18 19 22 31 35 38 40 42 47 48 statistical and clinical heterogeneity between them was significant.

Nurse prescribing

Nine studies included nurse prescribing in their protocol; three in secondary care settings,44 47 48 three using community interventions,24 35 37 two using telephone monitoring,30 31 and one based in primary care.40

Two good quality studies30 40 showed greater magnitudes of blood pressure reductions for nurse prescribing than for usual care: weighted mean difference, systolic −9.7 mm Hg (95% confidence interval −14.0 to −5.4) and diastolic −4.3 mm Hg (−7.4 to −1.2). Pooling of all studies showed similar reductions: systolic −8.9 mm Hg (−12.5 to −5.3) and diastolic −4.0 mm Hg (−5.3 to −2.7; fig 3).

Fig 3 Changes in blood pressure with interventions including nurse prescribing compared with usual care

Only one good quality study reported absolute blood pressure as an outcome, but pooling of four studies showed a significantly lower absolute outcome systolic blood pressure in favour of nurse prescribing: weighted mean difference −7.2 mm Hg (95% confidence interval −10.9 to −3.5).30 31 37 40

Two good quality studies showed no difference in achievement of study blood pressure target (relative risk 1.20, 95% confidence interval 0.96 to 1.50).40 48 Significant statistical and clinical heterogeneity precluded further pooled analysis.

Telephone monitoring

Seven studies included telephone monitoring of blood pressure by nurses.25 26 27 28 29 30 31 Meta-analysis of four groups from three good quality studies showed no significant difference in outcome systolic blood pressure (weighted mean difference −2.9 mm Hg, 95% confidence interval −7.5 to 1.6).25 26 29 Pooling of all studies gave a similar result (−3.5 mm Hg, −7.4 to 0.4; fig 4), and pooling of three studies also showed no difference for outcome diastolic blood pressure (−1.1 mm Hg, −5.8 to 3.6).26 29 31

Fig 4 Absolute systolic blood pressure after nurse led telephone monitoring compared with usual care

Pooled data from three studies25 27 31 (one of good quality25) showed a higher achievement of study blood pressure targets with telephone monitoring than with usual care (relative risk 1.24, 95% confidence interval 1.08 to 1.43).

Community monitoring

Eight studies involved nurse interventions delivered outside of healthcare settings. Locations included the home,32 33 37 50 community centres,24 26 or a choice of both.34 One study was set in the workplace35 and one in a pharmacy.36 Pooled data from four good quality studies26 32 33 34 showed a lower outcome systolic blood pressure in favour of monitoring in the community (weighted mean difference −3.4 mm Hg, 95% confidence interval −6.1 to −0.7; fig 5) and two good quality studies showed greater magnitudes of blood pressure reduction with community monitoring than with usual care: systolic −4.7 mm Hg (−8.3 to −1.2) and diastolic −3.1 mm Hg (−4.8 to −1.3).32 34 Pooling of data from all four studies also showed a greater magnitude of reductions in favour of the intervention: systolic −4.8 mm Hg (−7.0 to −2.7)32 34 36 37 and diastolic −3.5 mm Hg (−4.5 to −2.5).32 34 35 37

Fig 5 Absolute systolic blood pressure after community nurse led interventions compared with usual care for good quality studies

Four studies,32 35 36 50 including one of good quality,32 reported significantly better achievement of blood pressure targets in favour of the intervention, but significant heterogeneity precluded pooled analysis.

Nurse led clinics

Fourteen studies were of nurse led clinics in primary care20 21 22 23 27 28 35 38 39 40 41 42 43 50 and six in secondary care settings.44 45 46 47 48 49 For primary care studies, two of good quality showed no difference in diastolic blood pressure (−2.9 mm Hg, −6.9 to 1.1).20 40 Pooling of all studies showed a greater magnitude of reduction in blood pressure for nurse led clinics compared with usual care (systolic −3.5 mm Hg, −5.9 to −1.1 and diastolic −1.9 mm Hg, −3.4 to −0.5; fig 6),23 27 28 40 41 and two good quality studies showed no difference in achievement of blood pressure targets with nurse led clinics (relative risk 1.14, 95% confidence interval 0.83 to 1.57).22 40

Fig 6 Changes in blood pressure with primary care nurse led clinics compared with usual care

For secondary care clinics, only two were of good quality and did not report comparable outcomes.46 48 For all studies, pooling of data from three studies showed no difference in outcome diastolic blood pressure (weighted mean difference −1.4 mm Hg, −3.6 to 0.86)44 46 49 and no greater achievement of study blood pressure targets (relative risk 1.47, 95% confidence interval 0.79 to 2.74)44 47 48 in nurse led clinics compared with usual care.

Ethnicity

Significantly lower systolic blood pressure was achieved for any nurse led intervention for four groups from three good quality studies recruiting African American participants (weighted mean difference −7.8 mm Hg, 95% confidence interval −14.6 to −0.9) 24 29 40 but neither systolic nor diastolic blood pressure was lower on pooling of three good quality studies of Chinese participants (systolic −2.6 mm Hg, −7.5 to 2.3 and diastolic −0.5 mm Hg, −2.3 to 1.3; fig 7).33 34 46 Pooling of two studies, neither of good quality, showed no significant increase in the use of antihypertensive drugs in South Asian participants (relative risk 1.22, 95% confidence interval 0.90 to 1.65),19 23 but pooling of four studies across different ethnic groupings did show a small increase in favour of any nurse led intervention compared with usual care (1.22, 1.02 to 1.47).19 23 24 44

Fig 7 Systolic blood pressure readings for participants from ethnic minority groups

Cost and cost effectiveness

Only four studies presented any data. From the United Kingdom one study reported a cost per patient of £434 (€525, $632) over two years to provide additional nurse clinics and support from specialist nurses, representing £28 933 per quality adjusted life year gained19 and another study found that primary care costs were £9.50 per patient compared with £5.08 for usual care.43 In the United States a study reported a 50% higher total cost of staff at $134.68 (£92.65, €111.90) per patient treated in a nurse led clinic compared with $93.70 for usual care,47 but a Mexican study reported $4 (£2.75, €3.32) per patient or $1 per 1 mm Hg reduction of systolic blood pressure.32

Discussion

In comparison with usual patterns of care, nurse led interventions that included a stepped treatment algorithm showed significantly greater reductions of systolic and diastolic blood pressure, but this was not associated with higher achievement of blood pressure targets. Studies incorporating nurse led prescribing also showed bigger reductions of systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Telephone monitoring was associated with higher achievement of study targets for blood pressure. Community monitoring showed lower outcome systolic blood pressure, greater reductions in systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and, although pooling of data was not possible, greater achievement of study blood pressure targets. Nurse led clinics in primary care achieved greater reductions in systolic and diastolic blood pressure compared with usual care. No clear beneficial effects on our primary outcomes were observed from secondary care clinics.

Pooled interventions showed significantly lower systolic blood pressure in African American participants with nurse led interventions than with usual care, but little difference for other ethnic minority groups.

Strengths and limitations of this review

Since blood pressure was reported variously as final blood pressure or change from baseline for systolic or diastolic readings, less pooling of results was possible than may have been anticipated.

Thirteen of the 33 included randomised controlled trials met our quality criteria. Only three of these were from the United Kingdom20 22 48 and none investigated an unselected primary care hypertensive population. Therefore the evidence base for nurse led care of hypertension in the United Kingdom relies on generalisation of findings from other, principally American, healthcare systems. In total, 12 trials were identified from the United Kingdom, of which six studied blood pressure control in people with diabetes18 19 22 23 44 48, four in patients with ischaemic heart disease,20 21 39 50 and two in people with uncontrolled hypertension.38 43

We restricted our search to articles in English, which may have excluded some potential international data; however, we consider it unlikely that significant evidence applicable to UK health care would have only been published in another language.

The usual reason for judging a trial’s quality as inadequate was weakness of blinding. As it was not possible for the participants to always be blinded to whether they were seeing a doctor, nurse, or other health professional, this limitation must be accepted for any face to face intervention. We aimed to assess blinding of the researchers collecting outcome data to the intervention; these were often the same nurses who delivered the intervention and therefore were open to bias. This lack of formal blinding in trials is recognised as a methodological challenge51 but need not be seen as a limitation because implementation of these findings would also necessarily be unblinded, so a pragmatic approach to studying these interventions can be relevant.52 Future trials will, however, need careful design to minimise bias.

One third of studies gave no description of the method used to measure blood pressure and only seven referred to published guidelines on blood pressure measurement, therefore the reliability of reported outcome measures cannot be judged easily.

Although interventions such as use of algorithms and nurse prescribing were associated with meaningful blood pressure reductions there was not a concomitant rise in achievement of target blood pressure. Although apparently inconsistent this could be a sample size effect, with some studies underpowered to show differences in dichotomous outcomes. It may also be explained by the noticeable variation in individual blood pressure targets in the studies, which were sometimes composite or multiple.18 19 35 44 Therefore reporting of absolute blood pressure reductions may be the more robust outcome measure for comparison in future reviews.

Many studies combined the use of a treatment algorithm with the nurse intervention; therefore the results contributed to both analyses. It was not possible within this review to separate out thoroughly the components of each intervention that were or were not effective.

For most studies the duration of follow-up was relatively short; only five followed participants for more than 12 months.19 21 25 40 41 Therefore it is not possible to extrapolate the findings as sustained benefits of the interventions.

We present evidence of benefit in some studies of ethnic minority groups because hypertension is recognised to carry higher levels of morbidity and mortality in some such populations.8 These findings, however, pool different types of intervention so cannot identify specific nurse led interventions of benefit in these groups. Furthermore, the “usual care” arm of some studies, predominantly from America,24 26 29 40 represented minimal care; therefore the benefits shown may be larger than could be expected if introduced to more inclusive healthcare systems, such as are found in the United Kingdom.

We included cost and cost effectiveness as a secondary outcome measure. It is, however, possible that other papers discussing this outcome (that is, non-randomised controlled trials) were not retrieved by our search strategy. Therefore a more thorough primary review of cost data may be needed.

Comparison with existing literature

The traditional view of the nurse’s role in hypertension care is to educate, advise, measure blood pressure,51 and enhance self management.53 Previous reviews have suggested that nurse led care may achieve better outcomes by increased adherence to protocols and guidelines, but we found insufficient evidence to confirm this.14 The most recent review12 identified an organised system of regular review and stepped care as essential components of successful interventions. This updated review supports this view, showing benefits in blood pressure reduction with the use of a treatment algorithm. No previous review has found sufficient evidence to support the assertion that nurse prescribing should be a key component of nurse interventions for hypertension14; however, this review has shown better blood pressure outcomes in favour of nurse prescribing based on studies in American healthcare systems.

Interventions varied greatly in intensity and presumably therefore in cost. Lack of information on cost effectiveness has been identified previously,54 and although this was only a secondary outcome measure for this review we noted that only four studies, including one of good quality,32 reported on costs.19 32 43 47 All four showed higher costs for the intervention, approaching 50% higher in two cases.43 47 Only one study seemed to be cost effective,32 but costs depend on the healthcare system within which the intervention is delivered, so we were unable to show any cost benefit that could be generalised across differing systems. Although nurses may save on salary costs, the evidence is conflicting, with potential savings being offset by an increased length of consultation.55 Evidence of cost benefit in acute self limiting conditions56 cannot be assumed to translate to the management of chronic disease, so future trials should incorporate a formal cost effectiveness analysis within their design.

Hypertension is identified with higher prevalence and morbidity levels in some ethnic minority groups such as African Americans and South Asians.57 Studies recruiting from these populations found significant reductions in blood pressures with any nurse led intervention. For studies from non-UK healthcare systems, “usual care” represented minimal or absent care.29 40 We therefore interpret this with caution.

Implications for clinical practice

The delivery of nurse led care in chronic conditions is a complex intervention. This review suggests that such care can improve on doctor led or usual care of hypertension. The key component of an intervention seems to be a structured treatment algorithm, and we have found evidence in favour of nurse prescribing. Although no clear benefits were seen for secondary care clinics improvements were found in both primary care and community based settings, suggesting that these findings can be applied to primary care clinics in the United Kingdom, or equivalent community settings in other healthcare systems. Although the absolute differences in blood pressure seem small—for example, a 4 mm Hg greater reduction in diastolic blood pressure with nurse prescribing than with usual care, a 2 mm Hg reduction in diastolic blood pressure is associated with a 15% reduction in risk of stroke or transient ischaemic attack in primary prevention.58 Similarly a 20-30% reduction in frequency of stroke, coronary heart disease, major cardiovascular events, and cardiovascular death is seen with a 3 mm Hg reduction in systolic blood pressure,59 and differences of this magnitude or greater are seen with nurse led clinics, nurse prescribing, and the use of an algorithm.

Implications for future research

In this review we found international evidence of benefit from nurse led interventions but no evidence of good quality was derived from an unselected UK population with hypertension in primary care. Evidence from other healthcare systems cannot necessarily be generalised, therefore further studies relevant to the United Kingdom are needed. Such studies should ideally include a structured algorithm, examine the role of nurse led prescribing, and include a robust economic assessment. They should report absolute measures of blood pressure as this would best permit comparison with the existing literature and take care to minimise bias by blinding outcome assessors to the intervention.

Conclusions

Nurse led interventions for hypertension in primary care should include an algorithm to structure care and can deliver greater blood pressure reductions than usual care. There is some evidence of improved outcomes with nurse prescribers, but there is no evidence of good quality from United Kingdom studies of essential hypertension in primary care. Therefore, although this review has found evidence of benefit for nurse led interventions in the management of blood pressure, evidence is insufficient to support the widespread use of nurses in hypertension management within the UK healthcare systems.

What is already known on this topic

Nurses are integral members of the primary healthcare team and are involved in the management of hypertension

Previous literature reviews have suggested that nurse led care may be beneficial in the care of hypertension but the data are conflicting

What this study adds

This review presents evidence to support structured algorithm driven nurse led care of hypertension, and nurse prescribers

There is little directly applicable evidence for benefits of nurse involvement in hypertension within the UK National Health Service

We thank Kate Quinlan (East Somerset Research Consortium) for carrying out the searches and retrieving articles, Joy Choules (Primary Care Research Group) for helping retrieve articles, and Liam Glynn (Cochrane Hypertension Group) for sharing citation lists.

Contributors: CEC and LFP reviewed the literature search results, identified papers for retrieval, reviewed full papers for inclusion, and extracted data for meta-analysis. CEC and RST undertook the meta-analysis. JLC acted as study supervisor. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the findings and drafting of the manuscript. CEC is guarantor for the study.

Funding: This research was supported by the Scientific Foundation Board of the Royal College of General Practitioners and by the South West GP Trust.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any company for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any companies that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2010;341:c3995

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Search strategy

Forest plots for all comparisons

References

- 1.Ezzati M, Lopez AD, Rodgers A, Vander Hoom S, Murray CJL, and the Comparative Risk Assessment Collaborating Group. Selected major risk factors and global and regional burden of disease. Lancet 2002;360:1347-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Centre for Social Research. Health survey for England 2003. Department of Health, 2004.

- 3.Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, Muntner P, Whelton PK, He J. Global burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide data. Lancet 2005;365:217-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL Jr, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension 2003;42:1206-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Inkster M, Montgomery A, Donnan P, MacDonald T, Sullivan F, Fahey T. Organisational factors in relation to control of blood pressure: an observational study. Br J Gen Pract 2005;55:931-7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Phillips LS, Branch WT, Cook CB, Doyle JP, El Kebbi IM, Gallina DL, et al. Clinical inertia. Ann Intern Med 2001;135:825-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mancia G, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, Cifkova R, Fagard R, Germano G, et al. 2007 guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2007;28:1462-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Hypertension: management of hypertension in adults in primary care: partial update. Royal College of Physicians, 2006.

- 9.Confederation NHS, British Medical Association. New GMS contract 2003: investing in general practice. British Medical Association/NHS Confederation, 2003.

- 10.NHS Information Centre. Practice level QOF tables 2008/09—clinical domain—hypertension. 2009. www.ic.nhs.uk/statistics-and-data-collections/supporting-information/audits-and-performance/the-quality-and-outcomes-framework/qof-2008/09/data-tables/practice-level-data-tables.

- 11.Heneghan C, Perera R, Mant D, Glasziou P. Hypertension guideline recommendations in general practice: awareness, agreement, adoption, and adherence. Br J Gen Pract 2007;57:948-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fahey T, Schroeder K, Ebrahim S, Glynn L. Interventions used to improve control of blood pressure in patients with hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;1:CD005182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laurant M, Reeves D, Hermens R, Braspenning J, Grol R, Sibbald B. Substitution of doctors by nurses in primary care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;2:CD001271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oakeshott P, Kerry S, Austin A, Cappuccio F. Is there a role for nurse-led blood pressure management in primary care? Fam Pract 2003;20:469-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions 5.0.2 [updated September 2009]. Cochrane Collaboration, 2009. www.cochrane-handbook.org.

- 16.Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 5.0. Copenhagen: Nordic Cochrane Centre, Cochrane Collaboration, 2008.

- 17. Adams G, Gulliford MC, Ukoumunne OC, Eldridge S, Chinn S, Campbell MJ. Patterns of intra-cluster correlation from primary care research to inform study design and analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 2004;57:785-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]