Abstract

Much current research is focused on biologic enhancement of the tendon repair process. To evaluate the different methods, which include a variety of gene therapy and tissue engineering techniques, histological and biomechanical testing is often employed. Both modalities offer information on the progress and quality of repair; however, they have been historically considered as two separate entities. Histological evaluation is a less costly undertaking; however, there is no validated scoring scale to compare the results of different studies or even the results within a given study. Biomechanical testing can provide validated outcome measures; however, it is associated with increased cost and is more labor intensive. We hypothesized that a properly developed, objective histological scoring system would provide a validated outcome measure to compare histological results and correlate with biomechanics. In an Achilles tendon model, we have developed a histological scoring scale to assess tendon repair. The system grades collagen orientation, angiogenesis, and cartilage induction. In this study, histology scores were plotted against biomechanical testing results of healing tendons which indicated that a strong linear correlation exists between the histological properties of repaired tendons and their biomechanical characteristics. Concordantly, this study provides a pragmatic and financially feasible means of evaluating repair while accounting for both the histology and biomechanical properties observed in surgically repaired, healing tendon.

Keywords: Achilles tendon, Biomechanical testing, Tendon rupture, Histology

Introduction

There are four histologic stages of tendon healing, as described by Woo et al. [22]. During the first few hours following disruption of a tendon, a hemorrhagic phase ensues. A blood clot fills the gap, releasing cytokines that attract polymorphonuclear leukocytes and lymphocytes. An inflammatory phase then occurs at 24–48 h, marked by the arrival of macrophages. These cells phagocytose necrotic tissue and secrete growth factors, inducing neovascularization and the formation of granulation tissue. In the third phase, which occurs within the first week, fibroblasts arrive and begin producing collagen and matrix proteins. During the final phase, remodeling and maturation occur. There is a gradual decrease in the cellularity of the healed tissue, and the matrix becomes denser and longitudinally oriented. It is during this stage that collagen turnover, water content, and the ratio of collagen types I to III begin to approach normal levels, with type I collagen predominating. Maturation continues for many months, with a return to normal collagen concentration by 12 to 14 weeks.

Enhancement of the surgical repair of tendon tears through biological mechanisms, which directly influence the described histological phases of healing, is at the forefront of tendon repair literature. The only way to make certain that these biological methods are of value is through validated outcome measures. At this point, only biomechanical outcomes are validated via direct readings from tensile testing systems [1, 3, 9]. There are several, objective grading systems for looking at cartilage repair that include the Pineda scale [14, 15], the International Cartilage Repair Society cartilage repair assessment score [13], the O’Driscoll scale [14], and the Oswestry Arthroscopy Score [19]. However, there are no detailed, objective scoring systems that grade the success of tendon repair. Soslowsky et al. developed a subjective scale that looked at broad components of tendinosis [20]. However, this method has never been validated through biomechanical testing.

The development of a validated histological scoring system would be extremely beneficial. It would act as another reference point to comment on outcome studies and to compare various repair techniques. Additionally, animal studies are quite expensive. If there existed a histological scoring system that correlated well with biomechanical outcomes, it could justifiably be used in place of biomechanical testing, especially in studies that are financially burdensome. It was our purpose to design a validated histological scoring system sensitive enough to detect subtle differences in tendon composition that would correlate with the altered biomechanical properties.

In this report, we describe a novel histological scoring system that evaluates several different parameters of the tendon–tendon healing process. We hypothesized that the scoring system would strongly correlate with results of biomechanical testing, allowing us to formulate a Grande Histological Biomechanical Correlation Score (GHBCS), which we predict would equate a specific biomechanical score with a histological grade, ultimately achieving a score representative of a percentage of the nonruptured tendon’s biomechanical strength. We suggest that this score will provide researchers with another way to evaluate and compare outcomes of tendon healing studies.

Materials and Methods

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved the use of 96 male Sprague–Dawley rats weighing approximately 400 g for this study. The surgical procedure was performed under aseptic conditions. Midsubstance tenotomy was performed via scalpel transection. The Mason–Allen stitch technique, using the sutures coated with Recombinant Human Growth and Differentiation Factor 5 (rhGDF-5), was used to repair Achilles tendons. An average of 2.9 cm of suture was incorporated into each repair. Unoperated, contralateral tendons were used for biomechanical testing. Previous studies have shown that rhGDF-5 plays a well-documented role in the formation and healing process of tendons [5–8, 17]. We used the biomechanical and histologic data generated from two of these previous studies to develop the grading scale which was the aim of this project [7, 8].

The 96 rats were randomized into a 3-week time protocol (n = 48) and a 6-week time protocol (n = 48). The rats within each time protocol were randomly assigned to one of the four growth-factor-coated suture groups consisting of 0, 24, 55, and 556 ng/cm of rhGDF-5 (n = 12 in each suture group). Histology was evaluated in four rats within each group and biomechanics in eight rats. The personnel involved in this study were blinded to these assignments.

The animals were euthanized at either 3 or 6 weeks postoperatively. Histological sections were obtained from both the right and left limbs of the four rats killed for histology from each suture group. Each sample yielded ten slides with three specimens per slide and was stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Grading was performed using our novel histological scoring system evaluating three components: collagen grade, degree of angiogenesis, and cartilage induction. Collagen orientation and cartilage induction were graded on a scale of 0–3, and angiogenesis was graded on a scale of 0–2, with lower scores correlating to better histological results. The scoring delineation was as follows:

Collagen grade

- 0

normal collagen oriented tangentially

- 1

mild changes with collagen fibers less than 25% disorganized

- 2

moderate changes with collagen fibers between 25% and 50% disorganized

- 3

marked changes with collagen more than 50% disorganized

Degree of angiogenesis

- 0

moderate infiltration of tissue with arterioles

- 1

presence of capillaries

- 2

no vasculature infiltration

Cartilage formation

- 0

no cartilage formation

- 1

isolated hyaline cartilage nodules

- 2

moderate cartilage formation of 25% to 50%

- 3

extensive cartilage formation, more than 50% of the field involved

Assessment of each slide was performed by three independent, blinded observers (JD, DG, LW), reducing the potential for bias. All grades were assigned based on the visual field. Each specimen was graded based on a minimum of ten sections. The area that was used for grading was localized by the area between suture placements and was in the region where the transection was made. The total area used for observation and grading was typically 3 mm2. Magnification for grading was done at ×100 and ×200 using sections stained with H&E and Masson trichrome. Collagen orientation was also assessed using sections stained with Sirius red and observed under polarized light. Each specimen was assigned an average grade per variable, which was then totaled to provide an overall histological score for each rat. The total scores ranged from 0 to 8, with lower scores indicative of optimal ultimate tensile strength. The scores between treatment groups were then compared.

Mechanical behavior was tested on eight rats per treatment group using the tensile testing grips of an EnduraTec ELF 2100 (Bose Corp, Minnetonka, MN). Power studies confirmed that a sample size of eight would achieve a confidence level of 0.05 between the four groups [6]. In other words, through power analysis it was determined that a sample size of eight subjects per group yielded an 80% power to detect hypothesis differences at the 0.05 level using a two-tailed test. The dissected rat hind limbs were frozen at −80°C. At each time point, samples were thawed to 4°C and were pulled in uniaxial tension to the point of failure. A displacement rate of 0.025 mm/s was used in a closed-loop control, and the resulting load was documented to an accuracy of 0.005 N at a sampling rate of 2 Hz [8]. Time-independent load-displacement curves were created from temporal data on load and displacement. Ultimate tensile strength (maximum load supported by the sample normalized to the cross-sectional area) was calculated for each sample. Calculations of cross-sectional area were determined from measurements of the length of the major and minor axes of the tendon. Two-way ANOVA tests were performed to evaluate the effectiveness of treatment.

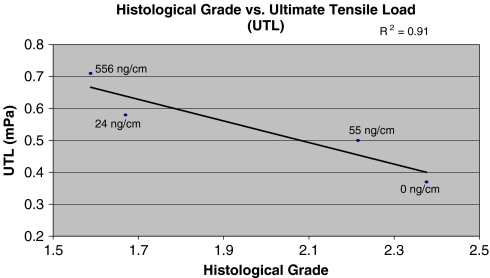

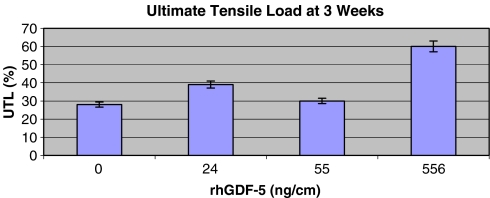

The coefficients of determination (R2) were determined through a Microsoft® Excel scatter plot analysis. This value was calculated as the square of the correlation coefficient. Biomechanical results from the experimental and control groups were compared, with the control tendon being the contralateral, unoperated tendon. Considering that the control tendon should exhibit optimal ultimate tensile load (UTL), we calculated a percentage of optimal UTL biomechanics using the experimental, surgically repaired groups. Histology scores were graphed against the UTL function for each treatment protocol, and the coefficients of determination (R2) were determined. Each UTL value that was plotted as a y-coordinate in Fig. 2 correlated with a percentage of optimal UTL for a given rhGDF-5 coated suture (Fig. 1). We also attempted to correlate the UTL data with each individual histology parameter.

Fig. 2.

Combined mean histological grade (collagen development/orientation, angiogenesis, and chondrogenesis) as a function of ultimate tensile load at 3 weeks postoperation. The R2 is 0.91, indicative of a strong linear correlation between the two variables.

Fig. 1.

Experimental ultimate tensile load as a percentage of the UTL of the unoperated, contralateral tendon at 3 weeks postoperation. The x-axis correlates to each type of rhGDF-5 suture used

Additionally, we determined histological intervals at which different biomechanical scores were evident based on the strong relationship between the variables. This determined the correlation score which we designate the Grande Histological Biomechanical Correlation Score. It equates a specific biomechanical score with a histological grade, ultimately achieving a score representative of a percentage of the nonruptured tendon’s ultimate tensile strength (Table 2).

Table 2.

The Grande Histological Biomechanical Correlation Score

| Histologic score | UTL (as percentage of unoperated control) |

|---|---|

| >2.2 | <30 |

| 2.1–2.2 | 30–31.5 |

| 2.0–2.1 | 31.5–33 |

| 1.9–2 | 33–34.5 |

| 1.8–1.9 | 34.5–36 |

| 1.7–1.8 | 36–37.5 |

| 1.6–1.7 | 37.5–39 |

| <1.6 | >50 |

Results

Sutures treated with both the low-dose (24 ng/cm) and high-dose (556 ng/cm) GDF-5 exhibited improvements in collagen orientation at postoperative week 3 as compared to controls. At 6 weeks, regardless of treatment, results were similar [8]. Isolated hyaline cartilage was found under all suture protocols in tendons at week 3. An increased presence of de novo cartilage formation was observed at 6 weeks postoperatively. Most of this chondrogenesis occurred in regions associated with suture placement. Neovascularization was greater in treated tendons than in the controls (Table 1). Ultimate tensile load data indicated that repaired tendons were weaker than the contralateral, unoperated tendons (P < .001). However, there was a significant difference between the UTL of the growth factor treated sutures and the control group (P < .01). The experimental tendons were more similar to the unoperated tendons, although there was still a significant difference between them (P < .02). The UTL biomechanics of the 3-week tendons were half that of the 6-week samples.

Table 1.

Mean histology grades and ultimate tensile load data, with standard deviations, for each type of rhGDF-5 suture used as observed at postoperative week 3

| Suture protocol (ng/cm) | Mean collagen score with standard deviation | Mean angiogenesis with standard deviation | Mean cartilage with standard deviation | Mean total histology score with standard deviation | Mean UTL with standard deviation (mPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2.0484 ± 0.72 | 0.2857 ± 0.65 | 0.04167 ± 0.18 | 2.376 | 0.37 ± 0.025 |

| 24 | 0.95833 ± 0.36 | 0.5382 ± 0.32 | 0.1736 ± 0.20 | 1.670 | 0.58 ± 0.041 |

| 55 | 1.5970 ± 0.69 | 0.5418 ± 0.11 | 0.07639 ± 0.35 | 2.215 | 0.50 ± 0.040 |

| 556 | 0.97770 ± 0.40 | 0.3725 ± 0.39 | 0.2379 ± 0.28 | 1.588 | 0.71 ± 0.030 |

The experimental groups consistently received better histology grades and ultimate tensile load measurements than the control group

The results from each suture protocol demonstrated that there was a direct relationship between reparative histology (low histology scores) and the ratio of ultimate tensile strength of the experimental groups over the controls (Fig. 2). Histological scores greater than 2.2 correlate with ultimate tensile loads less than 30% of that of an unoperated control. Scores below 1.6 are associated with ultimate tensile loads greater than 50% of that of an unoperated control and indicate a threshold for optimal repair conditions (Table 2). At histological scores greater than 2.2, disorganized collagen is observed in sections, little to no angiogenesis has occurred, and moderate to extensive cartilage formation is present. Collectively, these characteristics correlate to poor UTL biomechanics of less than 30% (Fig. 2). At histological scores of less than 1.6, normal collagen that is oriented tangentially is observed, a moderate infiltration of new vessels has occurred, and little to no chondrogenesis is present. Such characteristics are indicative of tendon with a greater biomechanical strength. This tendon possesses a biomechanical strength of greater than 50% of that of unoperated controls. The coefficient of determination of 0.91 seen in Fig. 2 is illustrative of the strong correlation between the histological properties and the biomechanical characteristics of the healing tendon (Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7). Additionally, the specific correlation coefficients obtained for collagen orientation, angiogenesis, and cartilage induction as compared to ultimate tensile strength were 0.59, 0.013, and 0.89, respectively (Table 3).

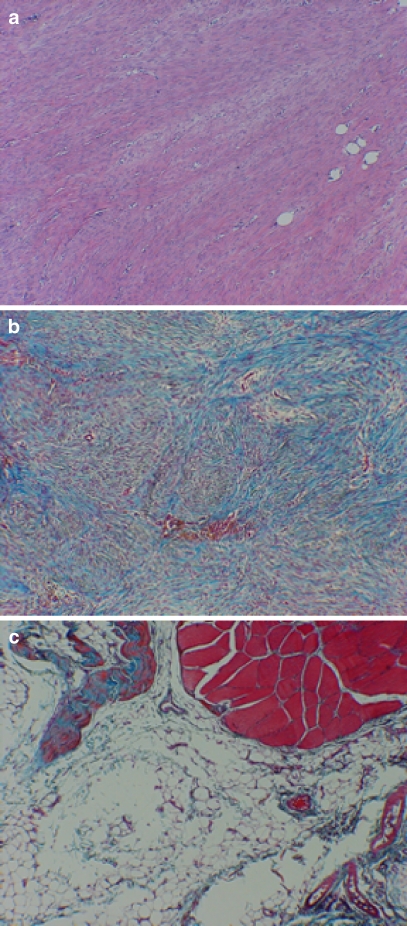

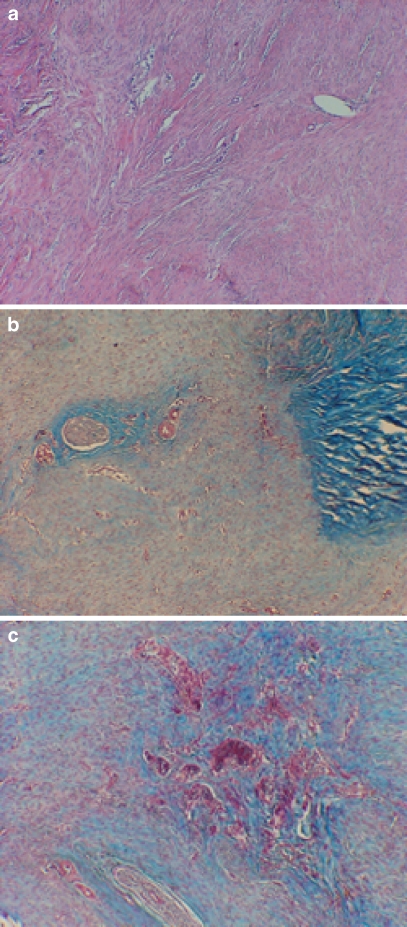

Fig. 3.

Representative light micrographs of collagen grade. a Experimentally repaired tendon with a collagen grade of 0–0.5. It has well-aligned parallel bundles of collagen. Suture holes are present in the lower right half of the frame. H&E, original magnification ×200. b Light micrograph of control suture-only repaired tendon which received a grade of 2.0. Note the relatively disorganized whorls of collagen bundles in a nonparallel arrangement. Masson trichrome, original magnification ×200. c Micrograph which illustrates a collagen score of 3. note complete lack of tendon bridging and fatty degeneration. Masson trichrome, original magnification ×100

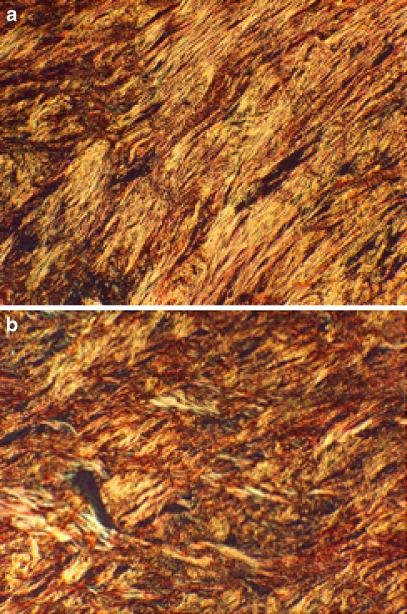

Fig. 4.

Polarized light micrographs used for collagen orientation scoring. a This specimen received a score of 0–0.5. The collagen alignment is clearly visible with tangentially arranged collagen bundles. Sirius red, original magnification ×200. b This specimen received a score of 2–2.5. Note the crisscross pattern of collagen more reminiscent of scar formation. Sirius red, original magnification ×200

Fig. 5.

This panel of light micrographs illustrates the range of scoring for the criteria for angiogenesis. a This specimen scored between 0 and 0.5, demonstrating normal to mild increases in vascular supply. H&E, original magnification ×100. b Specimen with generalized increased angiogenesis, scored a grade of 1. Numerous vessels can be seen in the repair tissue between the native cut tendon (right side of field). Masson trichrome, original magnification ×100. c A specimen with highly increased vascular invasion and scored a 2. Masson trichrome, original magnification ×100

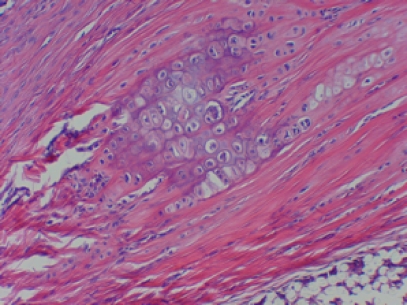

Fig. 6.

Cartilage induction in a space formerly occupied by a suture. The chondrocytes located within basophilic lacunae. This specimen received a score of 1. More extensive cartilage induction was prevalent in the higher doses of GDF-5 but was also present in the suture-alone specimens. H&E, original magnification ×400

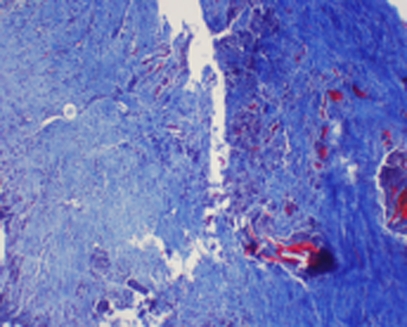

Fig. 7.

Control tendon showing poor tendon-to-tendon healing with obvious gap. This specimen received a collagen grade of 3. Masson trichrome, original magnification ×200

Table 3.

The correlation coefficients of the individual histological properties and the ultimate tensile strength observed for a given tendon

| Histological property | Correlation coefficient (R2) |

|---|---|

| Collagen orientation | 0.59 |

| Angiogenesis | 0.013 |

| Chondrogenesis | 0.89 |

The average histological score for each parameter was determined, as was the average ultimate tensile strength. The higher the coefficient, the greater the correlation between the two variables

Discussion

Through the use of a rat Achilles tendon model, we attempted to develop a means of quantifying postoperative biomechanical strength via analysis of histological cross sections. This has been accomplished via the creation of the Grande Histological Biomechanical Correlation Score.

While the experimental tendons experienced enhanced tendon healing in the 3-week study, data between the control and experimental groups in the 6-week groups were indistinguishable [8]. Despite the differences between the 3- and 6-week studies, data from all rats were applicable to the development of the GHBCS. In our previous report, the 6-week experimental and control groups had similar histological properties, and they had a similar correlation between their biomechanical properties. These data served to confirm what had been determined in the 3-week evaluation. That is, there is a strong connection between histology and biomechanics. Furthermore, this system will become increasingly useful as more biologic studies are performed in animal models.

The histological grading scale was in part developed with the goal of reducing subjectivity that has existed in previous grading systems, yet the subjectivity has not been completely eliminated. However, we were successful in showing a correlation between histology and biomechanics using the results of three independent observers. A PhD research scientist specializing in cartilage biology, an orthopedic surgeon, and a medical student participated in the histological evaluation. All of these individuals had a background in histology to ensure proper application of the scale and to maximize its implementation objectively. This method yielded the best correlation between histology and biomechanics. One of the benefits of showing the correlation between histology and biomechanics is that the researcher can achieve a reliable estimation of biomechanical performance without having to follow through with the costly endeavor. It is for this reason that we recommend that three observers grade the histological sections.

We chose to evaluate the relationship between histology and UTL via determination of the coefficient of determination (R2). This value is a statistical measure of how well a regression line approximates real data points so that an R2 value of 1.0 implies that the regression line perfectly fits the data. The coefficient of determination, like all statistical analyses investigating correlation, must be used cautiously. Correlation does not provide definitive proof that a relationship exists but helps to support such a notion. In this study, the high correlation observed between UTL and histology grade (R2 = 0.91) does not ensure that whenever one of these two variables changes, the other will also concordantly change. However, it implies that it is very likely to. As previously stated, this must be considered whenever one is attempting to prove a correlation between two variables and does not solely apply to our study.

Many of these processes associated with tendon healing are part of the natural physiologic response to injury and occur regardless of increased concentrations of growth factor. Some may argue that a score of 2.376 (control suture group) on the histology scale should not be indicative of a poor biomechanical rating, considering that 8 is the worst possible grade. However, when considering the body’s intrinsic ability to heal along with the data obtained from the 24 control subjects, the possibility of obtaining scores significantly above 2.376 seems unlikely.

We determined correlation coefficients between ultimate tensile load and the individual histological properties. When comparing collagen with UTL, the coefficient of determination of 0.59 suggested that grading of collagen histology alone was insufficient to determine UTL. In other words, the collagen characteristics observed did not strongly correlate with the UTL. Studies have stated that disorganized collagen fibrils are indicative of poorly healed tendon and contribute to poor biomechanics [11]. Additionally, it is known that the parallel arrangement of collagen fibers is, in a large part, responsible for its tensile strength [4, 21]. This we do not refute, as such statements properly emphasize the importance of collagen in tendon healing. However, we believe that consideration of collagen characteristics is only one of several criteria necessary for accurate determination of tendon healing as measured by UTL. Thus, we also include angiogenesis and chondrogenesis in our histological study.

Vascular infiltration was chosen as the second parameter because an augmented blood supply is needed to facilitate healing in an injured tendon. Injury to a tendon may disrupt the cells lining the tenosynovium and should induce angiogenesis [10]. A deficit in blood bringing nutrients and growth factors to the healing site has negative effects on repair. In fact, the initial healing of a tendon is dependent on blood-derived mesenchymal cells and fibroblasts [12]. Despite this, we did not observe a strong correlation between angiogenesis and UTL (Table 3). Similar to collagen formation, this parameter must be looked at in the context of all of the histological properties, in that they too impact tendon healing.

In injured tendons, it has been shown that there is an upregulation of cartilage-inducing genes. Cartilage phenotype has been found in tendons of rat models subjected to overuse protocols that induce tendinopathy [3]. Other studies have shown that the rats are prone to forming cartilage in their Achilles tendon following an insult [16, 18]. For our model, we used the presence of cartilage as an indication of an inferior repair process and poorer biomechanics. Our study confirmed that the presence of cartilage adversely impacts UTL and, subsequently, tendon healing. A strong coefficient of determination (R2 = 0.89) existed between chondrogenesis histology grades and UTL (Table 3); the less cartilage formation, the greater the UTL. When considering the correlation of individual histological parameters with the UTL, only cartilage formation had a significant connection. Although these data validate the results of previous studies elucidating the relationship between tendon injury and chondrogenesis, it must be analyzed in the context of collagen formation and angiogenesis as well.

It is only when we correlate the total histological grade, which incorporates scores from each of the three parameters, with UTL, that the strongest coefficient of determination is evident (Fig. 2). This serves as additional justification for the effectiveness of the scale in that in isolation, no single parameter correlates as well with biomechanics as does the total histological score. Furthermore, previous studies have placed a large emphasis on using collagen as a foundation for grading tendon repair [20] when, in fact, the use of two additional parameters (as described above) provides a better analysis of the state of the healing tendon.

The significance of a scoring system that enables a quantitative evaluation of biomechanical strength as a function of histological properties provides an efficient, thorough and financially attractive means of assessing tendon repair. In this model, we were able to prove that a strong correlation exists between a novel histological scoring scale and biomechanical properties of tendon repair in a rat model.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g., consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article. Of note, Johnson and Johnson Regeneratvie Therapeutics provided the rhGDF-5 for this study.

References

- 1.Ahmad CS, Wing D, Gardner TR, Levine WN, Bigliani LU. Biomechanical evaluation of subscapularis repair used during shoulder arthroplasty. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16(3 Suppl):S59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Archambault JM, Jelinsky SA, Lake SP, Hill AA, Glaser DL, Soslowsky LJ. Rat supraspinatus tendon expresses cartilage markers with overuse. J Orthop Res. 2007;25(5):617–624. doi: 10.1002/jor.20347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baskies MA, Tuckman D, Paksima N, Posner MA. A new technique for reconstruction of the ulnar collateral ligament of the thumb. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(8):1321–5. doi: 10.1177/0363546507303663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bi X, Li G, Doty SB, Camacho NP. A novel method for determination of collagen orientation in cartilage by Fourier transform infrared imaging spectroscopy (FT-IRIS) Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2005;13(12):1050–8. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chhabra A, Tsou D, Clark RT, Gaschen V, Hunziker EB, Mikic B. Gdf-5 deficiency in mice delays Achilles tendon healing. J Orthop Res. 2003;21(5):826–35. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(03)00049-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dines JS, Grande DA, Dines DM. Tissue engineering and rotator cuff tendon healing. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16(5 Suppl):S204–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dines JS, Grande DA, ElAttrache N, Dines DM. Biologics in shoulder surgery: suture augmentation and coating to enhance tendon repair. Techniques in Orthop. 2007;22(1):20–5. doi: 10.1097/01.bto.0000261867.07628.80. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dines JS, Weber L, Razzano P, Prajapati R, Timmer M, Bowman S, Bonasser L, Dines DM, Grande DA. The effect of growth differentiation factor-5-coated sutures on tendon repair in a rat model. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16(5 Suppl):S215–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Domb BG, Ehteshami JR, Shindle MK, Gulotta L, Zoghi-Moghadam M, MacGillivray JD, Altchek DW. Biomechanical comparison of 3 suture anchor configurations for repair of type II SLAP lesions. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(2):135–40. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fowble VA, Vigorita VJ, Bryk E, Sands AK. Neovascularity in chronic posterior tibial tendon insufficiency. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;450:225–30. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000218759.42805.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galatz LM, Sandell LJ, Rothermich SY, Das R, Mastny A, Havlioglu N, Silva MJ, Thomopoulos S. Characteristics of the rat supraspinatus tendon during tendon-to-bone healing after acute injury. J Orthop Res. 2006;24(3):541–50. doi: 10.1002/jor.20067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kajikawa Y, Morihara T, Watanabe N, Sakamoto H, Matsuda K, Kobayashi M, Oshima Y, Yoshida A, Kawata M, Kubo T. GFP chimeric models exhibited a biphasic pattern of mesenchymal cell invasion in tendon healing. J Cell Physiol. 2007;210(3):684–91. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kleeman RU, Krocker D, Cedraro A, Tuischer J, Duda GN. Altered cartilage mechanics and histology in knee osteoarthritis: relation to clinical assessment (ICRS Grade) Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2005;13(11):958–63. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moojen DJ, Saris DB, Auw Yang KG, Dhert WJ, Verbout AJ. The correlation and reproducibility of histological scoring systems in cartilage repair. Tissue Eng. 2002;8(4):627–34. doi: 10.1089/107632702760240544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pineda S, Pollack A, Stevenson S, Goldberg V, Caplan A. A semiquantitative scale for histologic grading of articular cartilage repair. Acta Anat (Basel). 1992;143(4):335–40. doi: 10.1159/000147272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rickert M, Wang H, Wieloch P, Lorenz H, Steck E, Sabo D, Richter W. Adenovirus-mediated gene transfer of growth and differentiation factor-5 into tenocytes and the healing rat Achilles tendon. Connect Tissue Res. 2005;46(4–5):175–83. doi: 10.1080/03008200500237120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodeo S, Potter HG, Turner S, Campbel D, Kim HJ, Atkinson B. Augmentation of rotator cuff tendon healing using an osteoinductive growth factor. Presented at Orthopaedic Research Society Annual Meeting, Dallas, TX; 2002

- 18.Shim JW, Elder SH. Influence of cyclic hydrostatic pressure on fibrocartilaginous metaplasia of achilles tendon fibroblasts. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2006;5(4):247–52. doi: 10.1007/s10237-005-0013-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith GD, Taylor J, Almqvist KF, et al. Arthroscopic assessment of cartilage repair: a validation study of 2 scoring systems. Arthroscopy. 2005;12:1462–7. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soslowsky LJ, Carpenter JE, DeBano CM, Banjeri I, Moalli M. Development and use of an animal model for investigations of rotator cuff disease. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1996;5:383–92. doi: 10.1016/S1058-2746(96)80070-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomopoulos S, Marquez JP, Weinberger B, Birman V, Genin GM. Collagen fiber orientation at the tendon to bone insertion and its influence on stress concentrations. J Biomech. 2006;39(10):1842–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woo S, Hildebrand K, Watanabe N, Fenwick J, Papageorgiou C, Wang J. Tissue engineering of ligament and tendon healing. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 1999;367(S):312–23. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199910001-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]