Abstract

Injury to the skin causes a breach in the protective layer surrounding the body. Many pathogens are resistant to antibiotics, rendering conventional treatment less effective. This led to the use of alternative antimicrobial compounds, such as silver ions, in skin treatment. In this review nanofibers, and the incorporation of natural antimicrobial compounds in these scaffolds, are discussed as an alternative way to control skin infections. Electrospinning as a technique to prepare nanofibers is discussed. The possibility of using these structures as drug delivery systems is investigated.

1. Introduction

Severe skin damage and loss of the protective layer exposes underlying tissue to secondary infections [1, 2]. In the United States, treatment of fire and burn wound infections amount to more than 7.5 billion US dollars per annum [3]. From one million patients, an estimated 10 000 die from secondary microbial infections [2, 4–9]. If wounds are not treated effectively, pathogens form biofilms, rendering them resistant to antibiotics [10–13]. In severe cases, biofilms need to be surgically removed to prevent further infection [14].

Staphylococcus aureus, including methicillin resistant strains (MRSA), are the most prevalent in skin infections. Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, Acinetobacter spp., and coagulase-negative staphylococci have also been isolated from skin lesions [15–19]. More than 95% of S. aureus strains are resistant to penicillin and 60–70% are resistant to methicillin [20–22]. Methicillin resistance is attributed to the mec A gene encoding penicillin binding proteins [20, 23]. These proteins occur in the cell wall and play a role in the synthesis of peptidoglycan and are usually inactivated by beta-lactam antibiotics. However, in MRSA the mec A gene encodes a low-antibiotic affinity penicillin binding protein, known as PBP2a, conferring methicillin resistance to the cells [20]. Some MRSA strains are also resistant to tetracyclines, sulphonamides, trimethoprim, macrolides, aminoglycosides, mupirocin, mafenide acetate, silver sulphadiazine, bacitracin, ciprofloxacin, and vancomycin [24–29]. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci and P. aeruginosa strains resistant to several antibiotics have also been reported [30].

This review focuses on the treatment of skin infections and open wounds and the biomedical application of electrospun nanofibers, with specific emphasis on antimicrobial delivery systems. Antimicrobials other than antibiotics are discussed.

2. Current Treatment of Skin Infections and Drawbacks

Most data on skin infections are from publications on burn wounds. Several treatments have been proposed. Silver sulfadiazine, a combination of silver nitrate and sodium sulfadiazine, has been used to treat invasive burn wound sepsis [6, 14, 32, 33]. With prolonged use, silver ions may be toxic, as it binds to DNA and prevents replication [34, 35]. Furthermore, some pathogens have developed resistance to silver [36–38].

Mafenide acetate and chlorexidine digluconate creams have been used to treat burn wound infections [14, 39]. The disadvantage of these topical creams is that they have to be applied twice daily. If incorporated in wound dressings, the bandages have to be changed daily, which may expose the wound to further infection [40]. As in the case of many other antimicrobials, pathogens with resistance to mafenide acetate have been reported, especially when used over an extended period [27]. Mupirocin has also been used in the treatment of burn wound infections [41].

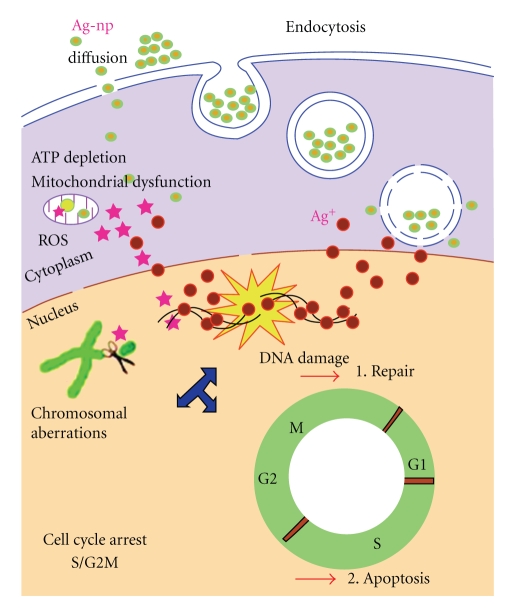

Nanotechnology offers the latest alternatives to wound dressings, of which Acticoat A.B, Silverlon, and Silvasorb with nanoparticles are good examples. Supporters of this technology claim that the nanocrystalline silver particles are released in a controlled manner, inhibiting the growth of a broad spectrum of pathogens [43–45]. Entrance of the nanoparticles into cells and their mode of action is summarized in Figure 1. Endosomes, filled with silver nanoparticles, lysosomes, and silver nanoparticles in the nucleus of treated cells, have been observed. Cells may also take up silver nanoparticles via endocytosis.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the uptake of silver nanoparticles, via endocytosis, and the mechanisms by which they cause toxicity to cells [31].

Some concerns exist regarding the medical use of silver particles, as they form reactive oxygen species (ROS), reduce ATP, and damage mitochondria and DNA [31, 46]. Furthermore, silver nanoparticles caused an inflammatory response in a murine model system [47]. Silver nanoparticles are, however, less toxic compared to gold nanoparticles, as observed in experiments with J774 A1 murine macrophages [48].

3. Production of Nanofibers

Nanofibers are produced from polymers treated in a specific manner to form threads of a few micrometers to nanometers in diameter. The large surface to volume ratio, and manipulation of surface properties, renders nanofibers the ideal matrix to develop super fine structures [49–51]. The possibility to immobilize antibiotics, enzymes, antimicrobial peptides, and growth hormones to nanofibers, or encapsulation into fiber matrixes, opens a new field in biomedical engineering [52–60].

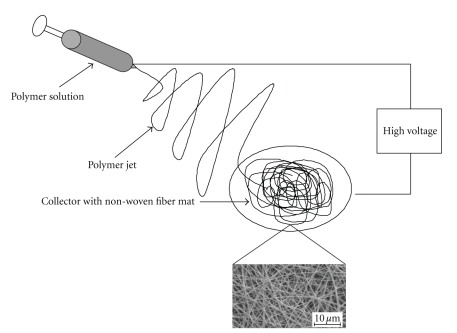

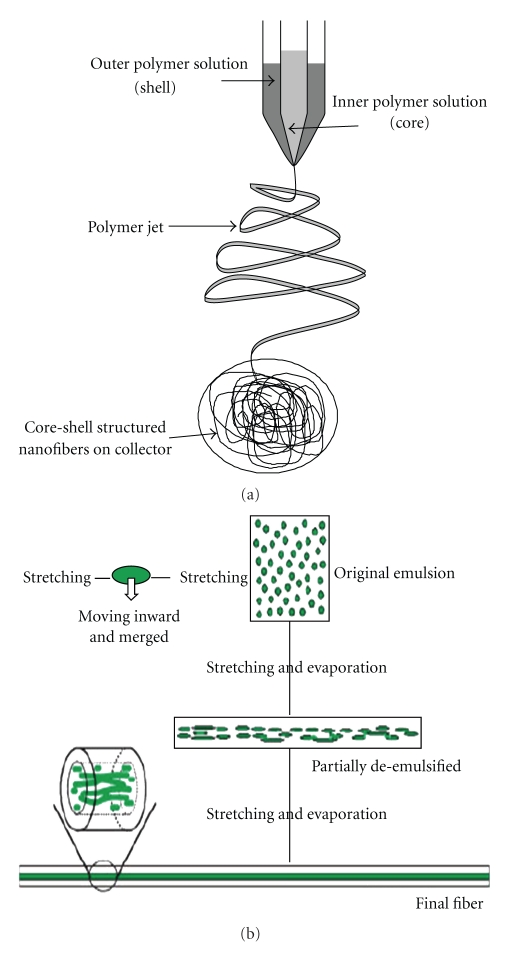

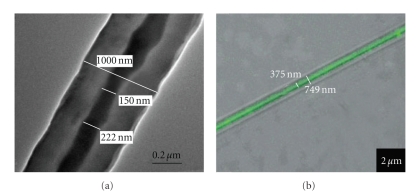

Several methods are used to produce ultra fine fibers, for example, self assembly of polymers, template synthesis, phase separation, and electrospinning [49, 62–66]. Electrospinning, schematically presented in Figure 2, is the most cost effective and easiest way to produce large volumes of nanofibers. One electrode is placed in a polymer solution and the other electrode is linked to a collector, which is usually a stationary or rotating metal screen, plate, or wheel. The electrically charged polymer forms a Taylor cone at the tip of the needle and is ejected at a specific charge. As the polymer solution accelerates, the solvent evaporates and nanofibers are formed. Fibers are aligned by using a rotating collector, an auxiliary electrical field, or a rotating collector with a sharp edge and a rapidly oscillating frame [67–71]. Coaxial electrospinning (Figure 3(a)) is used to produce nanofibers with a core-shell structure (Figure 4(a)), which is ideal for encapsulating hydrophilic molecules. Coaxial spun fibers have a high loading efficiency [56, 72]. Emulsion electrospinning is also used to produce core-shell-structured nanofibers (Figures 3(b) and 4(b)). An emulsion is prepared by emulsifying an aqueous phase, which contains a hydrophilic polymer or molecule to be encapsulated, into an organic phase containing a polymer that forms the shell [42, 61]. The emulsion is then electrospun into core-shell-structured nanofibers (Figure 4(b)).

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the electospinning process.

Figure 3.

(a) Schematic representation of the needle setup used in coaxial electrospinning and (b) representation of the formation of core-shell structured nanofibers by emulsion electrospininng [42].

Figure 4.

Core-shell structured nanofibers produced from (a) coaxial electrospun PEO and poly-dodecyl thiophene (PDT), with PDT forming the core structure [23] and (b) emulsion electrospun poly(ethylene glycol)-poly(L-lactic acid) diblock copolymer (PEG750-PLA) and PEO (the core is visible by labeling PEO with fluorescein isothiocyanate, FITC) [24].

4. Parameters That Influence Nanofiber Formation and the Electrospinning Process

The quality and characteristics of the final product are determined by the temperature, viscosity, elasticity, conductivity, and surface tension of the solution, strength of the electric field, distance between the needle tip and collector, and humidity [49, 73, 74]. Larger fibers (bigger diameter) are obtained by increasing the concentration of the polymer in solution. Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) at 4% (w/w) in a 50 : 50 (w/w) dimethylformamide : ethanol solution is used to produces fibers of 20 nm in diameter [75]. However, PVP at 8% (w/w) in the same solution produces fibers of 50 nm in diameter, and PVP at 10% (w/w) produce fibers of 300 nm in diameter. Electrospinning different concentrations of poly L-lactic acid (PLLA) in a chloroform solution produce nanofibers with different morphologies (Figure 5). PLLA of 1% (w/w) produces a “bead on a string” structure whereas 3% (w/w) PLLA forms nanofibers with a smooth structure [61].

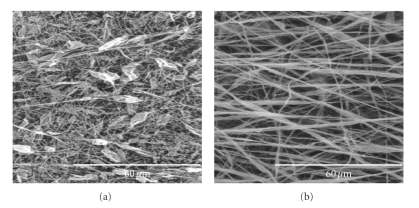

Figure 5.

Fibers produced from electrospinning with (a) 1% (w/w) PLLA (the “bead on a string” morphology is clearly visible) and (b) 3% (w/w) PLLA, showing a smooth structure [61].

Solvents influence the surface tension and viscosity of the solution and affect the morphology of fibers [75, 76]. PVP (4%, w/w) dissolved in dichloromethane (MC) forms fibers with spindle-like beads and hollow or solid structures whereas the same concentration PVP in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) forms sphere-like beads with solid structures. PVP dissolved in ethanol yields smooth fibers with a diameter ranging from 100 to 625 nm [75]. The PVP/DMF and PVP/MC solutions have a high surface tension (47.1 and 38.7 centipoise, resp.) and low viscosity (9.8 and 13.0 centipoise, resp.). A PVP/ethanol solution, on the other hand, has a low surface tension (29.3 centipoise) and high viscosity (17.3 centipoise). Different solvents evaporate at different speeds and affect the structure of the fibers [76]. Changes in current may also affect the morphology of fibers, as observed with polyethylene oxide (PEO). An increase from 5.5 kV to 9.0 kV changed the morphology of the PEO fibers from smooth to a “bead on a string” structure [74]. The importance of processing variables that influence fiber morphology during electrospinning is reviewed by Deitzel et al. [74].

5. Electrospun Nanofibers in Biomedical Engineering as Drug Delivery Vehicles

Natural and synthetic polymers have been spun into nanofibers for potential use in biomedical engineering [53, 54, 61, 76–79]. Chitin, a structural polysaccharide from arthropods, yielded fibers ranging from 40 to 600 nm in diameter [79]. A combination of water-soluble carboxyethyl chitosan and poly-vinyl alcohol (PVA) was electrospun to produce a wound dressing. The nanofibers revealed no toxicity when tested with a mouse fibroblast L929 cell line, and promoted cell attachment and proliferation [78]. Chitosan acetate bandages proved effective as an antimicrobial dressing when tested on BALB/c mice with burn wounds that have been infected with P. aeruginosa and Proteus mirabilis [80].

Hydrophilic and hydrophobic polymer blends have also been spun into biodegradable nanofibers. The hydrophobic polymer provides the structure or “backbone” and degrades over a long period whereas the more hydrophilic polymer degrades or dissolves faster. The choice of polymer or polymer blends play an important role in devices aimed at controlled release. Examples of using hydrophilic and/or hydrophobic polymers for the controlled release of molecules, for example, antibiotics, plasmids, growth factors, proteins, silver particles, bacteria and viruses will be discussed in more detail [54, 61, 82, 83, 89, 93].

5.1. Antibiotics

Rifampin, encapsulated in PLLA during electrospinning, and incubated in a 0.05 M Tris-HCl buffer, was only released when proteinase K was added to the solution. This suggests that the release of rifampin was initiated by the degradation of PLLA and not by normal diffusion [81]. In another experiment, doxorubicin hydrochloride and paclitaxil were encapsulated into PLLA nanofibers [81]. Doxorubicin hydrochloride was detected on the surface of the nanofibers but paclitaxil remained encapsulated. Rifampin and paclitaxil were more soluble in the chloroform/acetone solvent compared to doxorubicin hydrochloride. The solubility of the molecule to be encapsulated in the polymer solvent plays an important role in its distribution throughout the nanofibers. Tetracycline hydrochloride (5%, w/w) encapsulated in poly-ethylene-co-vinyl acetate (PEVA), or in a blend of PEVA and PLLA, has a relatively slow and consistent release rate [60]. The PEVA and PEVA/PLLA blend containing 5% (w/w) tetracycline hydrochloride had a similar release rate to Actisite, a commercial drug delivery system, following the initial high burst release. The antibiotic Mefoxin (cefoxitin sodium) was encapsulated in poly-lactate-co-glycolide (PLGA) fibers and in fibers consisting of a poly-lactate-co-glycolide/polyethylene glycol-block-poly(L-lactide) copolymer (PLGA/PEG-b-PLLA). Mefoxin released from the fibers inhibited the growth of S. aureus in culture and on an agar surface. PEG-b-PLLA prolonged the drug release for up to one week [82].

5.2. Plasmid DNA

The feasibility of encapsulating plasmid DNA in electrospun nanofibers and to use these nanofibers as gene delivery vehicles has also been shown [83]. PLGA and a PLA-PEG block copolymer was electrospun with a 7164 bp plasmid (pCMVβ), encoding β-galactosidase. The majority of plasmid DNA was released over 20 days. The bioactivity of pCMVβ was evaluated by conducting transfection experiments with preosteoblastic MC3T3 cells. The β-galactosidase gene was successfully expressed by preosteoblastic MC3T3 cells that have taken up the plasmid.

5.3. Growth Factors

Human β-nerve growth factor (NGF) was encapsulated into fibers consisting of a copolymer of poly ε-caprolactone and ethyl ethylene phosphate (PCLEEP) through electrospinning [54]. The bioactivity of NGF was evaluated by incubating rat pheochromocytoma (PC 12) cells in the supernatant of nanofibers containing encapsulated NGF and searching for differentiation into neurons. Bioactivity was recorded for up to three months. Human glialcell-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), encapsulated into PCLEEP nanofibers, was released in active form for up to two months [84]. A 15 mm nerve lesion was made in the left sciatic nerve of 3.5 month-old Sprague–Dawley rats. The rats then received longitudinally aligned fibers impregnated with GDNF. Longitudinally or circumferentially aligned fibers with no GDNF encapsulated within served as controls. In rats that received encapsulated GDNF, a bridge formed across the lesion and the nerve was regenerated after three months. However, the nerve system in only half the number of rats that received control fibers was regenerated. The stimulation of bone regeneration in nude mice that have been treated with bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2) encapsulated in PLGA-hydroxyapatite (HAp) nanofibers was also shown in [85]. Bioactive BMP-2 was released from the nanofibers over four weeks.

5.4. Proteins

Lysozyme was encapsulated in biodegradable poly-ε-caprolactone (PCL) and PEO fibers [53]. The highest release of lysozyme (87% over 12 days) was recorded in a PEO/PCL nanofiber with a 90/10 ratio. The released lysozyme maintained 90% of its catalytic activity. Cytochrome C has been encapsulated in nanofibers by emulsion electrospinning [61]. This was done by emulsifying an aqueous solution of cytochrome C in a chloroform solution containing PLLA. High encapsulation efficiencies (85% to 95%) were recorded after spinning. However, low levels of cytochrome C were released. Controlled release was obtained when PLLA was blended with poly(L-lysine) (PLL) and poly(ethylene imine) (PEI), hydrophilic polymers. A blend containing 50% PLL released most of the protein (75%) with a high initial burst release.

5.5. Bacteria and Viruses

Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus albus, and bacteriophages T7, T4, and λ were encapsulated in PVA nanofibers with water as solvent [88]. The encapsulated cells and bacteriophages survived the electrospinning process and remained viable for three months at −20 and −55°C. M13 viruses were encapsulated into PVP nanofibers [91]. The fibers were dissolved in a tris-buffered saline solution (pH 7.5). The released viruses were still able to infect bacterial cells. Micrococcus luteus and E. coli were encapsulated into PEO nanofibers with water as solvent [89]. Up to 74% of the M. luteus cells, but only 0.1% of the E. coli cells, survived the electrospinning process. We recently reported on the encapsulation of a probiotic lactic acid bacterium in electrospun PEO nanofibers [90]. Only 2% of the Lactobacillus plantarum cells survived the electrospinnig process. However, the cells that survived were still able to produce the antimicrobial peptide (bacteriocin) and inhibited the growth of E. faecium HKLHS that served as target strain.

5.6. Silver Nanoparticles

Silver nanoparticles were incorporated in cellulose acetate nanofibers by electrospinning cellulose acetate with 0.5 wt% AgNO3 [94]. Silver particles were generated on the surface of the nanofibers after irradiation at 245 nm. Almost all viable cells (99.9%) of Gram-positive bacteria, E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and P. aeruginosa were killed after 18 hours of exposure to the encapsulated silver particles. Silver-loaded zirconium phosphate was spun into poly ε-caprolactone fibers [86]. Growth inhibition of up to 99.27% of S. aureus and up to 98.44% of E. coli was recorded when the strains were cultured in the presence of these nanofibers. Human dermal fibroblasts that attached to the nanofibers continued to proliferate, suggesting that the fibers may be used as wound dressings. Similar findings have also been reported by Rujitanaroj et al. [95]. However, some authors have reported that silver may elicit toxic side effects on human cells as discussed elsewhere in this paper. Table 1 summarizes various molecules that have been encapsulated into synthetic and natural polymers, or blends thereof, by electrospinning to facilitate their release.

Table 1.

Molecules and organisms encapsulated into electrospun nanofibers.

| Encapsulated molecules | Polymer/polymer blends | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Antibiotics | ||

| Rifampin | PLLA | [81] |

| Doxorubicin hydrochloride | PLLA | [81] |

| Paclitaxil | PLLA | [81] |

| Tetracycline hydrochloride | PEVA | [60] |

| Mefoxin | PLGA/PEG-b-PLLA | [82] |

| Plasmid DNA | ||

| pCMVb encoding a β-Galactosidase | PLGA and PLA-PEG | [83] |

| Growth Factors | ||

| Human β-nerve growth factor (NGF) | PCLEEP | [54] |

| Human glialcell-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) | PCLEEP | [84] |

| Bone morfogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2) | PLGA-Hap | [85] |

| Antimicrobial compounds | ||

| Silver nanoparticles | Cellulose acetate | [72] |

| PCL/silver-loaded zirconium phosphate | [86] | |

| Proteins | ||

| BSA | PEO | [87] |

| Lysozyme | PCL/PEO | [53] |

| Lysozyme | PCL/PEG | [77] |

| Cytochrome C | PLLA/PLL | [61] |

| Bacteria | ||

| Eschericia coli | ||

| Staphylococcus albus | PVA | [88] |

| Micrococcus luteus | ||

| Eschericia coli | PEO | [89] |

| Lactobacillus plantarum | PEO | [90] |

| Bacteriophages | ||

| T7 | ||

| T4 | ||

| λ | PVA | [88] |

| M13 | PVP | [91] |

PLLA: poly (L-lactide); PEVA: poly-ethylene-co-vinyl acetate; PLGA: poly-lactate-co-glycolide; PEG: polyethylene glycol; PLGA/PEG-b-PLLA: poly-lactate-co-glycolide/polyethylene glycol-block-poly(L lactide); PCL: poly ε-caprolactone; PCLEEP: poly ε-caprolactone ethyl ethylene phosphate; Hap: Hydroxyapatite; PEO: polyethylene oxide; PDLA: poly(D,L-lactide); PLL: poly(L-lysine); PVA: poly(vinyl alcohol); PVP: polyvinylpyrrolidone.

6. Natural Alternatives to Antibiotics

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) are a diverse group of organisms with GRAS (generally regarded as safe) status and have been consumed over decades [96]. Most species produce bacteriocins, that is, ribosomally synthesized proteins or protein complexes with bacteriostatic or bactericidal activity against closely related species [97, 98]. The peptides have a net positive charge (cationic) and are amphiphilic or rather more hydrophobic. They intercalate into the cell membrane of sensitive cells, form pores and disrupt the proton motive force (PMF) [99–101].

Bacteriocins are classified into two major classes. Class I contains the lantibiotics that are small peptides that undergo posttranslational modifications and have lanthionine or β-methyllanthionine residues, for example, nisin, merscadin [102, 103]. Class II contains the nonlanthionine-containing bacteriocins that are small (<10 kDa) heat-stable peptides that do not undergo extensive post-translational modifications [92]. Examples include pediocin PA-1/AcH, plantaricin S, enterocin AS-48, and lactococcin A [104–107]. The classes and subclasses of bacteriocins are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Classification system for bacteriocins [92].

| Classes | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Class I | Lantibiotics |

| Class Ia | Small (19–38 amino acids), elongated, positively charged peptides that form pores |

| Class Ib | Globular peptides that interfere with essential enzymes |

| Class II | Nonlanthionine containing-bacteriocins |

| Class IIa | Pediocin-like peptides that contain the YGNGVXCXXXXVXV consensus sequence in their N-terminal |

| Class IIb | Two-peptide bacteriocins, require both peptides for activity |

| Class IIc | Cyclic peptides, N- and C-terminal of peptides are covalently linked |

| Class IId | Single non-pediocin like peptides |

Some bacteriocins, such as mersacidin, have shown activity towards MRSA that have been associated with various hospital acquired infections [108]. Nisin F was also investigated as treatment for subcutaneous skin infections caused by S. aureus [109]. Bacteriocins are thus attractive natural alternatives to antibiotics, which can be used in the treatment of bacterial infections. A localized delivery system is, however, required to control the level and rate of bacteriocins delivered to the wound. A novel approach would be to encapsulate bacteriocins into electrospun nanofibers and use this as wound dressings for burned victims.

The feasibility of encapsulating bacteriocins into electrospun nanofibers was recently reported in [90]. The bacteriocin plantaricin 423 retained activity after electrospinning and inhibited the growth of E. faecium HKLHS and Lactobacillus sakei DSM 20017 that served as target strains. Nisin, a bacteriocin produced by Lactococcus lactis, was successfully loaded in PLLA nanoparticles by using semicontinuous compressed CO2 antisolvent precipitation [110]. Nisin was released in the active form and exerted its antibacterial activity up to 45 days, when incubated with a culture of Lactobacillus delbrueckeii.

7. Conclusion and Future Trends

Electrospinning is a versatile and relatively easy technique to produce large amounts of nanofibers with diverse molecules encapsulated within. The large surface to volume ratio of nanofibers allows the encapsulation of high concentrations of bacteriocins and direct delivery to sites of skin infection. The use of bacteriocins to control infections may help to prevent further increase in antibiotic resistance amongst bacteria and may prevent negative side effects some current medication has on patients. Release of bacteriocins from nanofibers can be controlled by selecting polymers of specific composition. Furthermore, specific nanofiber scaffolds can be designed that are oxygen permeable and structurally similar to the extracellular matrix (EM) in skin.

Ideally, nanofiber wound dressings should not only contain antimicrobial agents, but a combination of compounds that would accelerate the healing process and alleviate discomfort. Such compounds may include anti-inflammatory and tissue repairing drugs. Although anti-inflammatory drugs have been encapsulated into nanofibers, no reports have been published on the encapsulation of combined compounds.

Future research has to focus on developing nanofber wound dressings containing a combination of antimicrobial compounds, anti-inflammatory drugs, and painkillers. Furthermore, the nanofiber scaffold has to be designed to allow controlled released of the drugs over an extended period to avoid frequent changes of wound dressings. The toxicity of nanofibers needs to be researched, that is, much more in vivo studies need to be performed.

References

- 1.Shelby J, Merrell SW. In vivo monitoring of postburn immune response. The Journal of Trauma. 1987;27(2):213–216. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198702000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altoparlak U, Erol S, Akcay MN, Celebi F, Kadanali A. The time-related changes of antimicrobial resistance patterns and predominant bacterial profiles of burn wounds and body flora of burned patients. Burns. 2004;30(7):660–664. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fire Deaths and Injuries: Fact Sheet, http://www.cdc.gov/HomeandRecreationalSafety/Fire-Prevention/fires-factsheet.html.

- 4. American Burn Associations. Burn Incidence Fact Sheet, 2002.

- 5. CDC Mass Casualties fact sheet, 2006, http://www.bt.cdc.gov/masscasualties/pdf/burns-masscasualties.pdf.

- 6.Pruitt BA, Jr., McManus AT, Kim SH, Goodwin CW. Burn wound infections: current status. World Journal of Surgery. 1998;22(2):135–145. doi: 10.1007/s002689900361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Erol S, Altoparlak U, Akcay MN, Celebi F, Parlak M. Changes of microbial flora and wound colonization in burned patients. Burns. 2004;30(4):357–361. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2003.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vindenes H, Bjerknes R. Microbial colonization of large wounds. Burns. 1995;21(8):575–579. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(95)00047-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruck HM, Nash G, Stein JM, Lindberg RB. Studies on the occurrence and significance of yeasts and fungi in the burn wound. Annals of Surgery. 1972;176(1):108–110. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197207000-00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Costerton JW, Stewart PS, Greenberg EP. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science. 1999;284(5418):1318–1322. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edwards R, Harding KG. Bacteria and wound healing. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 2004;17(2):91–96. doi: 10.1097/00001432-200404000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ceri H, Olson ME, Stremick C, Read RR, Morck D, Buret A. The Calgary biofilm device: new technology for rapid determination of antibiotic susceptibilities of bacterial biofilms. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1999;37(6):1771–1776. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.1771-1776.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Beer D, Stoodley P, Lewandowski Z. Liquid flow in heterogeneous biofilms. Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 1994;44(5):636–641. doi: 10.1002/bit.260440510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Church D, Elsayed S, Reid O, Winston B, Lindsay R. Burn wound infections. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2006;19(2):403–434. doi: 10.1128/CMR.19.2.403-434.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santucci SG, Gobara S, Santos CR, Fontana C, Levin AS. Infections in a burn intensive care unit: experience of seven years. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2003;53(1):6–13. doi: 10.1053/jhin.2002.1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guggenheim M, Zbinden R, Handschin AE, Gohritz A, Altintas MA, Giovanoli P. Changes in bacterial isolates from burn wounds and their antibiograms: a 20-year study (1986–2005) Burns. 2009;35(4):553–560. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taylor GD, Kibsey P, Kirkland T, Burroughs E, Tredget E. Predominance of staphylococcal organisms in infections occurring in a burns intensive care unit. Burns. 1992;18(4):332–335. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(92)90158-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lesseva MI, Hadjiiski OG. Staphylococcal infections in the Sofia Burn Centre, Bulgaria. Burns. 1996;22(4):279–282. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(95)00144-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chim H, Tan BH, Song C. Five-year review of infections in a burn intensive care unit: high incidence of Acinetobacter baumannii in a tropical climate. Burns. 2007;33(8):1008–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim JY. Understanding the evolution of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clinical Microbiology Newsletter. 2009;31(3):17–23. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hackbarth CJ, Chambers HF. Methicillin-resistant staphylococci: genetics and mechanisms of resistance. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 1989;33(7):991–994. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.7.991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fraise AP, Mitchell K, O’Brien SJ, Oldfield K, Wise R. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in nursing homes in a major UK city: an anonymized point prevalence survey. Epidemiology and Infection. 1997;118(1):1–5. doi: 10.1017/s0950268896007182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hiramatsu K. Molecular evolution of MRSA. Microbiology and Immunology. 1995;39(8):531–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1995.tb02239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cook N. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus versus the burn patient. Burns. 1998;24(2):91–98. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(97)00114-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Slocombe B, Perry C. The antimicrobial activity of mupirocinan update on resistance. Journal of Hospital Infection. 1991;19(supplement 2):19–25. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(91)90198-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Udo EE, Pearman JW, Grubb WB. Emergence of high-level mupirocin resistance in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Western Australia. Journal of Hospital Infection. 1994;26(3):157–165. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(94)90038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smoot EC, Kucan JO, Graham DR, Barenfanger JE. Susceptibility testing of topical antimicrobials against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Journal of Burn Care & Research. 1992;13(2):198–202. doi: 10.1097/00004630-199203000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scheel O, Lyon DJ, Rosdahl VT, Adeyemi-Dora FAB, Ling TKW, Cheng AFB. In-vitro susceptibility of isolates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus 1988–1993. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 1996;37(2):243–251. doi: 10.1093/jac/37.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hiramatsu K, Hanaki H, Ino T, Yabuta K, Oguri T, Tenover FC. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clinical strain with reduced vancomycin susceptibility. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 1997;40(1):135–136. doi: 10.1093/jac/40.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neu HC. The crisis in antibiotic resistance. Science. 1992;257(5073):1064–1073. doi: 10.1126/science.257.5073.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.AshaRani PV, Mun GLK, Hande MP, Valiyaveettil S. Cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of silver nanoparticles in human cells. ACS Nano. 2009;3(2):279–290. doi: 10.1021/nn800596w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsumura H, Yoshizawa N, Narumi A, Harunari N, Sugamata A, Watanabe K. Effective control of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a burn unit. Burns. 1996;22(4):283–286. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(95)00145-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pruitt BA, Jr., O’Neill JA, Jr., Moncrief JA, Lindberg RB. Successful control of burn-wound sepsis. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1968;203(12):1054–1056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poon VKM, Burd A. In vitro cytotoxity of silver: implication for clinical wound care. Burns. 2004;30(2):140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2003.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lansdown AB. Silver. 2: toxicity in mammals and how its products aid wound repair. Journal of Wound Care. 2002;11(5):173–177. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2002.11.5.26398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bridges K, Kidson A, Lowbury EJL, Wilkins MD. Gentamicin- and silver-resistant Pseudomonas in a burns unit. British Medical Journal. 1979;1(6161):446–449. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6161.446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li X-Z, Nikaido H, Williams KE. Silver-resistant mutants of Escherichia coli display active efflux of Ag+ and are deficient in porins. Journal of Bacteriology. 1997;179(19):6127–6132. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.19.6127-6132.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silver S, Phung LT, Silver G. Silver as biocides in burn and wound dressings and bacterial resistance to silver compounds. Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2006;33(7):627–634. doi: 10.1007/s10295-006-0139-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pegg SP. Multiple resistant Staphylococcus aures. Annals of the Academy of Medicine Singapore. 1992;21(5):664–666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stefanides MM, Sr., Copeland CE, Kominos SD, Yee RB. In vitro penetration of topical antiseptics through eschar of burn patients. Annals of Surgery. 1976;183(4):358–364. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197604000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rode H, Hanslo D, de Wet PM, Millar AJW, Cywes S. Efficacy of mupirocin in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus burn wound infection. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 1989;33(8):1358–1361. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.8.1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu X, Zhuang X, Chen X, Wang X, Yang L, Jing X. Preparation of core-sheath composite nanofibers by emulsion electrospinning. Macromolecular Rapid Communications. 2006;27(19):1637–1642. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dunn K, Edwards-Jones V. The role of ActicoatTM with nanocrystalline silver in the management of burns. Burns. 2004;30(supplement 1):S1–S9. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(04)90000-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heggers J, Goodheart RE, Washington J, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of three silver dressings in an infected animal model. Journal of Burn Care and Rehabilitation. 2005;26(1):53–56. doi: 10.1097/01.bcr.0000150298.57472.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Greenhalgh K, Turos E. In vivo studies of polyacrylate nanoparticle emulsions for topical and systemic applications. Nanomedicine. 2009;5(1):46–54. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hsin Y-H, Chen C-F, Huang S, Shih T-S, Lai P-S, Chueh PJ. The apoptotic effect of nanosilver is mediated by a ROS- and JNK-dependent mechanism involving the mitochondrial pathway in NIH3T3 cells. Toxicology Letters. 2008;179(3):130–139. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2008.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sung JH, Ji JH, Yoon JU, et al. Lung function changes in Sprague-Dawley rats after prolonged inhalation exposure to silver nanoparticles. Inhalation Toxicology. 2008;20(6):567–574. doi: 10.1080/08958370701874671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yen H-J, Hsu S-H, Tsai C-L. Cytotoxicity and immunological response of gold and silver nanoparticles of different sizes. Small. 2009;5(13):1553–1561. doi: 10.1002/smll.200900126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang Z-M, Zhang Y-Z, Kotaki M, Ramakrishna S. A review on polymer nanofibers by electrospinning and their applications in nanocomposites. Composites Science and Technology. 2003;63(15):2223–2253. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yoon K, Kim K, Wang X, Fang D, Hsiao BS, Chu B. High flux ultrafiltration membranes based on electrospun nanofibrous PAN scaffolds and chitosan coating. Polymer. 2006;47(7):2434–2441. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Theron J, Walker JA, Cloete TE. Nanotechnology and water treatment: applications and emerging opportunities. Critical Reviews in Microbiology. 2008;34(1):43–69. doi: 10.1080/10408410701710442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Agarwal S, Wendorff JH, Greiner A. Use of electrospinning technique for biomedical applications. Polymer. 2008;49(26):5603–5621. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim TG, Lee DS, Park TG. Controlled protein release from electrospun biodegradable fiber mesh composed of poly(ε-caprolactone) and poly(ethylene oxide) International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 2007;338(1-2):276–283. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2007.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chew SY, Wen J, Yim EKF, Leong KW. Sustained release of proteins from electrospun biodegradable fibers. Biomacromolecules. 2005;6(4):2017–2024. doi: 10.1021/bm0501149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Quaglia F. Bioinspired tissue engineering: the great promise of protein delivery technologies. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 2008;364(2):281–297. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2008.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jiang H, Hu Y, Li Y, Zhao P, Zhu K, Chen W. A facile technique to prepare biodegradable coaxial electrospun nanofibers for controlled release of bioactive agents. Journal of Controlled Release. 2005;108(2-3):237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Porter JR, Henson A, Popat KC. Biodegradable poly(ε-caprolactone) nanowires for bone tissue engineering applications. Biomaterials. 2009;30(5):780–788. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aluigi A, Varesano A, Montarsolo A, et al. Electrospinning of keratin/poly(ethylene oxide) blend nanofibers. Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 2007;104(2):863–870. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tabesh H, Amoabediny GH, Nik NS, et al. The role of biodegradable engineered scaffolds seeded with Schwann cells for spinal cord regeneration. Neurochemistry International. 2009;54(2):73–83. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kenawy E-R, Bowlin GL, Mansfield K, et al. Release of tetracycline hydrochloride from electrospun poly(ethylene-co-vinylacetate), poly(lactic acid), and a blend. Journal of Controlled Release. 2002;81(1-2):57–64. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(02)00041-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Maretschek S, Greiner A, Kissel T. Electrospun biodegradable nanofiber nonwovens for controlled release of proteins. Journal of Controlled Release. 2008;127(2):180–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nagai Y, Unsworth LD, Koutsopoulos S, Zhang S. Slow release of molecules in self-assembling peptide nanofiber scaffold. Journal of Controlled Release. 2006;115(1):18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hartgerink JD, Beniash E, Stupp SI. Self-assembly and mineralization of peptide-amphiphile nanofibers. Science. 2001;294(5547):1684–1688. doi: 10.1126/science.1063187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pender MJ, Sneddon LG. An efficient template synthesis of aligned boron carbide nanofibers using a single-source molecular precursor. Chemistry of Materials. 2000;12(2):280–283. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tan EPS, Lim CT. Physical properties of a single polymeric nanofiber. Applied Physics Letters. 2004;84(9):1603–1605. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Huczko A. Template-based synthesis of nanomaterials. Applied Physics A. 2000;70(4):365–376. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Boland ED, Wnek GE, Simpson DG, Pawlowski KJ, Bowlin GL. Tailoring tissue engineering scaffolds using electrostatic processing techniques: a study of poly(glycolic acid) electrospinning. Journal of Macromolecular Science, Part A. 2001;38(12):1231–1243. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Theron A, Zussman E, Yarin AL. Electrostatic field-assisted alignment of electrospun nanofibres. Nanotechnology. 2001;12(3):384–390. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fong H, Reneker DH. Electrospinning and formation of nano-fibers. In: Salem DR, editor. Structure Formation in Polymeric Fibers. Munich, Germany: Hanser; 2001. pp. 225–246. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wu Y, Carnell LA, Clark RL. Control of electrospun mat width through the use of parallel auxiliary electrodes. Polymer. 2007;48(19):5653–5661. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fong H, Liu W, Wang C-S, Vaia RA. Generation of electrospun fibers of nylon 6 and nylon 6-montmorillonite nanocomposite. Polymer. 2002;43(3):775–780. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sun Z, Zussman E, Yarin AL, Wendorff JH, Greiner A. Compound core-shell polymer nanofibers by co-electrospinning. Advanced Materials. 2003;15(22):1929–1932. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liang D, Hsiao BS, Chu B. Functional electrospun nanofibrous scaffolds for biomedical applications. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2007;59(14):1392–1412. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Deitzel JM, Kleinmeyer J, Harris D, Beck Tan NC. The effect of processing variables on the morphology of electrospun nanofibers and textiles. Polymer. 2001;42(1):261–272. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yang Q, Zhenyu LI, Hong Y, et al. Influence of solvents on the formation of ultrathin uniform poly(vinyl pyrrolidone) nanofibers with electrospinning. Journal of Polymer Science. 2004;42(20):3721–3726. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fong H, Chun I, Reneker DH. Beaded nanofibers formed during electrospinning. Polymer. 1999;40(16):4585–4592. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li Y, Jiang H, Zhu K. Encapsulation and controlled release of lysozyme from electrospun poly(ε-caprolactone)/poly(ethylene glycol) non-woven membranes by formation of lysozyme-oleate complexes. Journal of Materials Science. 2008;19(2):827–832. doi: 10.1007/s10856-007-3175-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhou Y, Yang D, Chen X, Xu Q, Lu F, Nie J. Electrospun water-soluble carboxyethyl chitosan/poly(vinyl alcohol) nanofibrous membrane as potential wound dressing for skin regeneration. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9(1):349–354. doi: 10.1021/bm7009015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Min B-M, Lee SW, Lim JN, et al. Chitin and chitosan nanofibers: electrospinning of chitin and deacetylation of chitin nanofibers. Polymer. 2004;45(21):7137–7142. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dai T, Tegos GP, Burkatovskaya M, Castano AP, Hamblin MR. Chitosan acetate bandage as a topical antimicrobial dressing for infected burns. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2009;53(2):393–400. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00760-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zeng J, Xu X, Chen X, et al. Biodegradable electrospun fibers for drug delivery. Journal of Controlled Release. 2003;92(3):227–231. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(03)00372-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kim K, Luu YK, Chang C, et al. Incorporation and controlled release of a hydrophilic antibiotic using poly(lactide-co-glycolide)-based electrospun nanofibrous scaffolds. Journal of Controlled Release. 2004;98(1):47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Luu YK, Kim K, Hsiao BS, Chu B, Hadjiargyrou M. Development of a nanostructured DNA delivery scaffold via electrospinning of PLGA and PLA-PEG block copolymers. Journal of Controlled Release. 2003;89(2):341–353. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(03)00097-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chew SY, Mi R, Hoke A, Leong KW. Aligned protein-polymer composite fibers enhance nerve regeneration: a potential tissue-engineering platform. Advanced Functional Materials. 2007;17(8):1288–1296. doi: 10.1002/adfm.200600441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fu Y-C, Nie H, Ho M-L, Wang C-K, Wang C-H. Optimized bone regeneration based on sustained release from three-dimensional fibrous PLGA/HAp composite scaffolds loaded with BMP-2. Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 2008;99(4):996–1006. doi: 10.1002/bit.21648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Duan Y-Y, Jia J, Wang S-H, Yan W, Jin L, Wang Z-Y. Preparation of antimicrobial poly(e-caprolactone) electrospun nanofibers containing silver-loaded zirconium phosphate nanoparticles. Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 2007;106(2):1208–1214. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kowalczyk T, Nowicka A, Elbaum D, Kowalewski TA. Electrospinning of bovine serum albumin optimization and the use for production of biosensors. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9(7):2087–2090. doi: 10.1021/bm800421s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Salalha W, Kuhn J, Dror Y, Zussman E. Encapsulation of bacteria and viruses in electrospun nanofibres. Nanotechnology. 2006;17(18, article 25):4675–4681. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/17/18/025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gensheimer M, Becker M, Brandis-Heep A, Wendorff JH, Thauer RK, Greiner A. Novel biohybrid materials by electrospinning: nanofibers of poly (ethylene oxide) and living bacteria. Advanced Materials. 2007;19(18):2480–2482. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Heunis TDJ, Botes M, Dicks LMT. Encapsulation of Lactobacillus plantarum 423 and its bacteriocin in nanofibers. Probiotics and Antimicrobial Proteins. 2010;2(1):46–51. doi: 10.1007/s12602-009-9024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lee S-W, Belcher AM. Virus-based fabrication of micro- and nanofibers using electrospinning. Nano Letters. 2004;4(3):387–390. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cotter PD, Hill C, Ross RP. Bacteriocins: developing innate immunity for food. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2005;3(10):777–788. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wang Y, Yang Q, Shan G, et al. Preparation of silver nanoparticles dispersed in polyacrylonitrile nanofiber film spun by electrospinning. Materials Letters. 2005;59(24-25):3046–3049. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Son WK, Youk JH, Park WH. Antimicrobial cellulose acetate nanofibers containing silver nanoparticles. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2006;65(4):430–434. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rujitanaroj P-O, Pimpha N, Supaphol P. Wound-dressing materials with antibacterial activity from electrospun gelatin fiber mats containing silver nanoparticles. Polymer. 2008;49(21):4723–4732. [Google Scholar]

- 96.De Vuyst L, Vandamme EJ. Nisin, a lantibiotic produced by Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis: properties, biosynthesis, fermentation and application. In: De Vuyst L, Vandamme EJ, editors. Bacteriocins of Lactic acid Bacteria. Boca Raton, Fla, USA: Chapman & Hall; 1994. pp. 151–221. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jack RW, Tagg JR, Ray B. Bacteriocins of gram-positive bacteria. Microbiological Reviews. 1995;59(2):171–200. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.2.171-200.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Klaenhammer TR. Genetics of bacteriocins produced by lactic acid bacteria. FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 1993;12(1–3):39–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1993.tb00012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Moll GN, Konings WN, Driessen AJM. Bacteriocins: mechanism of membrane insertion and pore formation. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 1999;76(1–4):185–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Abee T, Krockel L, Hill C. Bacteriocins: modes of action and potentials in food preservation and control of food poisoning. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 1995;28(2):169–185. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(95)00055-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.McAuliffe O, Ross RP, Hill C. Lantibiotics: structure, biosynthesis and mode of action. FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 2001;25(3):285–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2001.tb00579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sahl H-G, Bierbaum G. Lantibiotics: biosynthesis and biological activities of uniquely modified peptides from gram-positive bacteria. Annual Review of Microbiology. 1998;52:41–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.52.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Altena K, Guder A, Cramer C, Bierbaum G. Biosynthesis of the lantibiotic mersacidin: organization of a type B lantibiotic gene cluster. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2000;66(6):2565–2571. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.6.2565-2571.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chikindas ML, Garcia-Garcera MJ, Driessen AJM, et al. Pediocin PA-1, a bacteriocin from Pediococcus acidilactici PAC1.0, forms hydrophilic pores in the cytoplasmic membrane of target cells. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1993;59(11):3577–3584. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.11.3577-3584.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Jiménez-Díaz R, Rios-Sénchez RM, Desmazeaud M, Ruiz-Barba JL, Piard - JC. Plantaricins S and T, two new bacteriocins produced by Lactobacillus plantarum LPCO10 isolated from a green olive fermentation. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1993;59(5):1416–1424. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.5.1416-1424.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Galvez A, Gimenez-Gallego G, Maqueda M, Valdivia E. Purification and Amino 574 Acid Composition of Peptide AntibioticAS-48 Produced by Streptococcus (Enterococcus) faecalis subsp. liquefaciens S-48. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 1989;33(4):437–441. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.4.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Holo H, Nilssen O, Nes IF. Lactococcin A, a new bacteriocin from Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris: isolation and characterization of the protein and its gene. Journal of Bacteriology. 1991;173(12):3879–3887. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.12.3879-3887.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kruszewska D, Sahl H-G, Bierbaum G, Pag U, Hynes SO, Ljungh Å. Mersacidin eradicates methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in a mouse rhinitis model. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2004;54(3):648–653. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.De Kwaadsteniet M, Van Reenen CA, Dicks LMT. Evaluation of nisin F in the treatment of subcutaneous skin infections, as monitored by using a bioluminescent strain of Staphylococcus aureus. Probiotics and Antimicrobial Proteins. 2010;2(2):61–65. doi: 10.1007/s12602-009-9017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Salmaso S, Elvassore N, Bertucco A, Lante A, Caliceti P. Nisin-loaded poly-L-lactide nano-particles produced by CO2 anti-solvent precipitation for sustained antimicrobial activity. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 2004;287(1-2):163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]