Abstract

The signaling pathway controlling antigen receptor-induced regulation of the transcription factor NF-κB plays a key role in lymphocyte activation and development and the generation of lymphomas. Work of the past decade has led to dramatic progress in the identification and characterization of new players in the pathway. Moreover, novel enzymatic activities relevant for this pathway have been discovered, which represent interesting drug targets for immuno-suppression or lymphoma treatment. Here, we summarize these findings and give an outlook on interesting open issues that need to be addressed in the future.

The transcription factor NF-κB plays a key role in lymphocyte activation and lymphoma formation. Scaffold proteins and the protease MALT1 link antigen receptors with NF-κB and are potential therapeutic targets.

Lymphocytes play a major role in the defense against infection and tumors through their capacity to detect specific disease-associated antigens. Triggering of lymphocyte cell-surface antigen receptors (AgR) leads to the initiation of signaling pathways that regulate the activation, proliferation and survival of the stimulated lymphocyte. One such signaling pathway that has recently gained a lot of interest is the AgR-dependent activation of the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) transcription factor family. Genetic defects in this pathway are linked to immune deficiencies, whereas aberrant constitutive NF-κB activation is associated with the development of autoimmune diseases and neoplastic disorders (Karin et al. 2002; Li and Verma 2002). The precise mechanism by which AgR triggering controls NF-κB activation in lymphocytes is therefore a focus of intense investigation.

NF-κB designates a family of heterodimeric transcription factors that share a Rel homology domain (RHD), required for DNA binding and homo- or hetero-dimerization. Transcriptionally active NF-κB dimers are composed of a member with a RHD (p50 or p52) and another member with a transcription activation domain in addition to the RHD (RelA, RelB, or c-Rel). NF-κB family members can be activated by either the classical (also called canonical) pathway, which depends upon p50, RelA, and c-Rel, or by the alternative (also called noncanonical) pathway, which is p52- and RelB-dependent (Bonizzi and Karin 2004). We will focus on the classical pathway, as the phenotype of mice deficient for functional p50, RelA or c-Rel provide strong evidence for engagement of this pathway in AgR-dependent lymphocyte activation (Li and Verma 2002).

Before activation of the classical pathway, NF-κB function is suppressed through interaction with the inhibitor of κB (IκB) family of cytoplasmic inhibitors, which block nuclear translocation of NF-κB family members. As a consequence, engagement of the classical pathway requires IκB degradation before NF-κB can enter the nucleus and drive transcription. This is achieved by the stimulus-dependent activation of the IκB kinase (IKK) complex, which phosphorylates IκBα on S32 and S36 within a conserved DSGLDS motif, thereby targeting the protein for rapid ubiquitination-dependent degradation by the proteasome (Li and Verma 2002; Bonizzi and Karin 2004). The IκB family members IκBβ and IκBε harbor similar motifs, suggesting these are also regulated by IKK-dependent mechanisms (Li and Verma 2002). Although all stimuli leading to classical NF-κB activation appear to converge on IKK-mediated IκB phosphorylation, the upstream events controlling IKK activation are distinct and specific to the individual type of NF-κB-activating stimulus. TNFα-regulated IKK activation, for example, depends upon the TRAF2 ubiquitin ligase and RIP-1 kinase, whereas lipopolysaccharide-regulated NF-κB activation requires the adaptor protein MyD88 and IRAK family kinases. Recent studies revealed that AgR-regulated IKK activation specifically requires the signaling protein CARMA1 and its binding partners BCL10 and MALT1 (Ruland et al. 2001; Egawa et al. 2003; Hara et al. 2003; Jun et al. 2003; Newton and Dixit 2003; Ruefli-Brasse et al. 2003; Ruland et al. 2003). Here, we will summarize the current state of knowledge regarding the molecular and biological function of the CBM (CARMA1, BCL10, and MALT1) proteins during lymphocyte activation, with a particular focus on T-cell activation.

STRUCTURAL FEATURES OF CBM PROTEINS

The scaffold protein CARMA1 (CARD-MAGUK1, also called CARD11 or Bimp3) is characterized by the presence of a caspase recruitment domain (CARD) and its homology to proteins of the MAGUK (membrane-associated guanylate kinase) family (Bertin et al. 2001; Gaide et al. 2001; McAllister-Lucas et al. 2001; Thome 2004). CARMA1 shares with MAGUK proteins a number of family-specific protein–protein interaction domains. These domains support the function of MAGUKs as scaffolding proteins at sites of cell–cell contact, such as for example the neuronal synapse or tight junctions (Thome 2004; Funke et al. 2005; Feng and Zhang 2009). MAGUK family members typically contain one to three PDZ domains (named after the domain-containing PSD-95, Dlg and ZO-1 proteins), followed by SH3 (src homology 3) and GUK (guanylate kinase) domains (Funke et al. 2005) (Fig. 1). PDZ domains target proteins to the plasma membrane by binding to a four amino-acid motif present in the cytoplasmic carboxyl terminus of transmembrane proteins (Ponting et al. 1997). In the case of MAGUK proteins, such interactions are thought to contribute to the structure and dynamics of synaptic cell structures (Feng and Zhang 2009). For the MAGUK protein PSD-95, the SH3 domain undergoes an unusual intramolecular interaction with the GUK domain that does not involve a typical Pro-rich SH3 target motif (McGee et al. 2001; Tavares et al. 2001). This intramolecular interaction may negatively regulate MAGUK function by keeping the protein in a closed, inactive conformation. Interaction with a regulatory ligand may be necessary for the conformational change that enables dimerization or oligomerization by intermolecular SH3-GUK interactions (Yaffe 2001; Feng and Zhang 2009). Whether such a mechanism regulates CARMA1 function is currently unclear.

Figure 1.

Molecular structure of CARMA1, BCL10, and MALT1. CARMA1 has an amino-terminal caspase-recruitment domain (CARD) that is followed by a coiled coil domain and a linker region. The carboxy-terminal region of CARMA1 contains a PDZ domain (a motif present in the Psd-95, Dlg and ZO-1 proteins), a Src homology-3 (SH3) domain and a guanylate kinase (GUK) motif characteristic of proteins of the membrane-associated guanylate kinase (MAGUK) family (Thome and Tschopp 2003). BCL10 harbors an amino-terminal CARD motif and a carboxy-terminal extension of unknown structure. The carboxy-terminal part of the BCL10 CARD and a short stretch of 13 amino acids following the CARD are required for constitutive binding to MALT1 (Lucas et al. 2001; Langel et al. 2008). MALT1 contains an amino-terminal death domain (DD) that is followed by two immunoglobulin (Ig)-like domains required for BCL10 binding (Lucas et al. 2001). The carboxy-terminal part of MALT1 contains the protease domain, a third Ig domain, and an extension of unknown structure (Uren et al. 2000).

In addition to its carboxy-terminal MAGUK-like features, CARMA1 contains a CARD motif and a coiled coil domain that are functionally crucial (Fig. 1). CARD motifs are protein–protein interaction domains that can mediate homotypic CARD/CARD interactions between two, or possibly even three CARD-containing binding partners (Hofmann et al. 1997; Weber and Vincenz 2001). The CARD of CARMA1 mediates homotypic interaction with the adaptor BCL10 (Bertin et al. 2001; Gaide et al. 2001; Gaide et al. 2002), which contains an amino-terminal CARD motif and a Ser/Thr-rich carboxyl terminus of unknown structure (Costanzo et al. 1999; Koseki et al. 1999; Srinivasula et al. 1999; Thome et al. 1999; Willis et al. 1999; Yan et al. 1999; Zhang et al. 1999) (Fig. 1). BCL10 constitutively forms a complex with MALT1 (Uren et al. 2000; Lucas et al. 2001); this interaction may stabilize these proteins, as knockout of BCL10 or MALT1 reduces MALT1 or BCL10 levels, respectively (Klemm et al. 2006). BCL10 interaction with MALT1 depends upon both a short stretch of amino acids following the CARD motif of BCL10 (aa 107-119), and an additional site within the CARD (Bonizzi and Karin 2004; Lucas et al. 2007).

MALT1 (also called paracaspase) contains several interesting structural features that are suggestive of its molecular functions (Fig. 1). The most striking feature of MALT1 is its protease domain, which shares homology with proteases of the caspase and metacaspase family (Uren et al. 2000; Vercammen et al. 2007). In addition to this catalytic domain, MALT1 contains an amino-terminal death domain (DD) predicted to associate with an unidentified DD-containing protein, two immunoglobulin-like domains required for BCL10 interaction (Uren et al. 2000; Lucas et al. 2007), as well as binding motifs for the ubiquitin ligase TNF receptor-associated factor-6 (TRAF6) (Sun et al. 2004; Noels et al. 2007). In the following discussion, we will outline the present understanding of the molecular function of CARMA1, BCL10, and MALT1 in lymphocyte activation, with a particular focus on the individual domain structures that enable function.

MOLECULAR FUNCTION OF CARMA1

CARMA1 contains a number of defined protein domains (Fig. 1), most of which are required for mediating activation of the NF-κB pathway. Reconstitution experiments in CARMA1-silenced cells have demonstrated that the CARD, coiled coil, SH3 and GUK domains are all essential for the NF-κB-activating function of CARMA1, whereas the PDZ domain appears dispensable (Pomerantz et al. 2002). Consistent with the known function of the CARMA1 CARD motif in mediating BCL10 interaction (Bertin et al. 2001; Gaide et al. 2001), lymphocytes expressing CARMA1 constructs with a CARD point mutation or deletion show impaired NF-κB and JNK responses (Gaide et al. 2002; Pomerantz et al. 2002; Newton and Dixit 2003). Moreover, mice expressing a CARD-deficient CARMA1 mutation are immunodeficient, probably as a consequence of impaired proliferation of lymphocytes in response to AgR or PMA/ionomycin stimulation (Newton and Dixit 2003). The CARMA1 coiled coil domain appears to mediate oligomerization (Rawlings et al. 2006; Tanner et al. 2007), a contention supported by the dominant negative activity of coiled coil-only CARMA1 mutants that inhibit NF-κB activation and IL-2 production in stimulated Jurkat T cells (Tanner et al. 2007). As the coiled coil motif bound MALT1 in a two-hybrid assay (Che et al. 2004), this domain may also contribute to the recruitment of the preformed MALT1-BCL10 complexes, CBM complex stabilization and/or to the oligomerization-dependent MALT1 activation (see later). The specific contributions of the SH3 and GUK domains to CARMA1 function are less well understood. For other MAGUK proteins such as PSD-95, it has been proposed that the SH3 and GUK domains appear to mediate auto-repression via intramolecular interaction, whereas intermolecular SH3-GUK interactions may mediate signal-induced oligomerization (Tavares et al. 2001; Yaffe 2001; Thome 2004). It remains unclear whether such mechanisms regulate CARMA1 activity. The phenotype of a fortuitous CARMA1 mutation, L808P, suggests the SH3 domain of CARMA1 regulates membrane localization and protein kinase C-θ (PKCθ), BCL10 and IKK complex recruitment to the immunological synapse (Wang et al. 2004). When overexpressed, the GUK domain binds to the Ser/Thr kinase PDK1, and PDK1 silencing affected TCR-induced NF-κB activation (Lee et al. 2005). However, these findings were contradicted in a later study, in which conditional PDK1 knockout in chicken DT40 cells did not affect BCR-induced IKK activation (Shinohara et al. 2007). Thus, it remains unclear whether PDK1 participates in AgR-stimulated IKK activation via CARMA1.

REGULATION OF CARMA1 FUNCTION BY PHOSPHORYLATION

The molecular function of CARMA1 appears to be regulated by a complex array of phosphorylation events modulating CARMA1 association with BCL10 and MALT1 in activated lymphocytes (Matsumoto et al. 2005; Sommer et al. 2005; Shinohara et al. 2007) (Table 1; Fig. 2). Although the kinases involved and the order and priority of individual phosphorylation events remain somewhat unclear, data obtained with CARMA1 point mutants, phosphorylation-specific antibodies and mass spectrometric approaches suggest the following general model for phosphorylation-dependent CARMA1 regulation. For the sake of clarity, we will refer later to human CARMA1 residue positions; the corresponding positions for mouse and chicken are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview on CARMA1 phosphorylation sites and functions

| Human CARMA1 | S109 | T110 | S551 | S552 | S555 | S565 | S608 | S637 | S645 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse CARMA1 | S116 | T117 | S563 | S564 | S567 | S577 | S620 | S649 | S657 |

| Chicken CARMA1 | S118 | T119 | – | S575 | S578 | S588 | S631 | S660 | S668 |

| Proposed kinase(s) | CaMKII | PKCβ/θ ? | HPK1 | PKCβ/θ | IKKβ | unknown | CK1α | PKCβ/θ nPKC | PKCβ/θ |

| Determined by: | |||||||||

| - in vitro kinase assay - mass spectrometry - P-specific antibodies | + | – | + | + | + | – | – | + (PKCβ/θ) | + |

| – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | + | |

| – | + | – | – | + | – | + | + | + | |

| Effect of Ala mutation: | |||||||||

| - NF-κB activation | Impaired | Impaired | Impaired | Impaired | Impaired | Impaired | Increased | normal or increased | Impaired |

| - JNK activation | n.d. | impaired | n.d. | impaired | impaired | n.d. | normal ? | n.d. | impaired |

| Effect on association with BCL10 & MALT1: | S/D increased | T/A impaired | n.d. | S/A impaired | S/A normal | S/A impaired | |||

| References | (Ishiguro et al. 2007) | (Shinohara et al. 2007) | (Brenner et al. 2009) | (Matsumoto et al. 2005; Sommer et al. 2005; Shinohara et al. 2007) | (Matsumoto et al. 2005; Shinohara et al. 2007) | (Matsumoto et al. 2005) | (Shinohara et al. 2007; Bidere et al. 2009) | (Matsumoto et al. 2005; Sommer et al. 2005; Moreno-Garcia et al. 2009) | (Matsumoto et al. 2005; Sommer et al. 2005; Shinohara et al. 2007) |

The table summarizes proposed Serine (S) and Threonine (T) phosphorylation sites present in human, mouse, or chicken CARMA1, and the functional effects of corresponding CARMA1 point mutations. Abbreviations: n.d., not determined; nPKC, novel PKC; S/A or T/A, mutation of Serine or Threonine into Alanine; S/D, mutation of Serine into Aspartic acid; P-specific, phosphorylation site-specific.

Figure 2.

Phosphorylation events affecting CARMA1 function. (A) In resting cells, CARMA1 adopts an inactive conformation that is stabilized by an intramolecular interaction between the CARD and the linker region. Antigen receptor stimulation triggers the phosphorylation of the CARMA1 linker motif and the region between the CARD and coiled coil motifs. This is thought to induce a conformational change, possibly by electrostatic repulsion, which unfolds the CARMA1 conformation, allowing the CARD to bind to the CARD motif of BCL10. (B) Summary of proposed phosphorylation events proposed to positively or negatively regulate CARMA1 function. See Table 1 and text for further details.

AgR stimulation rapidly induces phosphorylation of CARMA1 within a region linking the coiled coil and the PDZ domains (Rueda and Thome 2005) (Fig. 2). Within this linker region, S552 and S645 were identified as targets of PKCβ or PKCθ in two independent studies (Matsumoto et al. 2005; Sommer et al. 2005), while phosphorylation of S555 by IKKβ was proposed in a subsequent study (Shinohara et al. 2007). S565 was identified as an in vivo phosphorylation site in activated T cells by mass spectrometry, and mutation of this site resulted in impaired NF-κB activation (Matsumoto et al. 2005). The kinase responsible for S565 phosphorylation has not yet been determined. Another site, S551, was targeted for phosphorylation by hematopoietic progenitor kinase-1 (HPK1) in vitro, consistent with the observed requirement for CARMA1 in HPK1-mediated NF-κB activation in T cells (Brenner et al. 2009). Collectively, these phosphorylation events appear to trigger a conformational change in CARMA1, allowing BCL10-MALT1 recruitment (Fig. 2A). In the inactive, closed conformation, the CARMA1 linker region may bind back to the CARD motif, thereby blocking CARD-dependent protein-protein interactions. Stimulation-induced phosphorylation of the S552 and S645 linker residues may weaken this interaction, inducing an open conformation of CARMA1. In this conformation, the CARD motif and potentially the coiled coil domain are accessible for interaction with BCL10 and MALT1, respectively (Che et al. 2004; Sommer et al. 2005). This model is mainly suggested by in vitro binding assays using recombinant constructs containing the linker and CARD motifs of CARMA1 (Sommer et al. 2005). In these assays, recombinant active PKCθ suppressed the in vitro association of the CARD with a wild-type, but not a S552/S645 double mutant linker construct (Sommer et al. 2005).

Another phosphorylation cluster at positions 109 and 110, carboxy-terminal of the CARD domain, appears to regulate CARMA1 function (Ishiguro et al. 2006; Shinohara et al. 2007). Gene silencing and inhibitor experiments suggested that calmodulin-dependent kinase II (CaMKII) contributes to TCR-regulated NF-κB activation through CARMA1 S109 phosphorylation (Ishiguro et al. 2006). In support of such a model, the CARMA1 mutant S109D, which mimics phosphorylation at S109, drives strong constitutive NF-κB activation and BCL10 interaction. However, further experimental evidence is required to confirm S109 as a bona fide phosphorylation site.

Collectively, the data discussed above suggests that initial phosphorylation at S551, S552, S555, and S645, and possibly at S109, promotes CARMA1 activation. PKCβ/θ, IKKβ, CaMKII, and HPK1 were identified as responsible for phosphorylation-dependent CARMA1 activation, but other kinases may also regulate CARMA1 function. For example, PDK1 and Akt were reported to interact with CARMA1 and their regulation of NF-κB activity was CARMA1-dependent (Lee et al. 2005; Narayan et al. 2006). Future studies are required to establish whether these kinases modulate NF-κB activity by phosphorylating CARMA1.

Recent findings suggest that phosphorylation events may also suppress CARMA1 activity, possibly during negative feedback regulation. S637, for example, is phosphorylated during the later stages of AgR signaling, and may serve to turn off CARMA1 signaling (Moreno-Garcia et al. 2009). In support of this, an S637A mutant of CARMA1 potentiated NF-κB activation. Although PKC inhibitors blocked S637 phosphorylation, this event occurred independently of PKCβ, suggesting that a member of the novel PKC family is responsible for S637 phosphorylation (Moreno-Garcia et al. 2009). The mechanism by which S637 phosphorylation inhibits CARMA1 activity remains unclear.

Another site, S608, that is likely to be a phosphorylation target of Casein kinase 1α, may inhibit CARMA1-dependent NF-κB activation (Bidere et al. 2009). The carboxyl terminus of CK1α binds to CARMA1 coiled coil and linker regions (Bidere et al. 2009), and mutation of S608 abolished CK1α-mediated phosphorylation of such a recombinant CARMA1 protein fragment in 293T cells (Bidere et al. 2009). Whether S608 is indeed phosphorylated by CK1α in vivo is still unknown, however, CARMA1 S608A mutation clearly augmented its NF-κB activating potency (Bidere et al. 2009).

Finally, CARMA1 T110 was clearly identified as a stimulation-induced phosphorylation site (Shinohara et al. 2007). In B cells, phosphorylation at T110 still occurred in the absence of IKKβ or PKCβ, suggesting that another kinase might be responsible (Shinohara et al. 2007). Interestingly, expression of a T110A mutant potentiated basal IKK activation, suggesting that phosphorylation at this site negatively regulates CARMA1 function. Similarly, an S883A mutant showed impaired inducible IKK activation, but high constitutive IKK activity (Shinohara et al. 2007). In contrast to T110, there is no evidence for in vivo phosphorylation of S883, so such findings should be interpreted with caution.

In conclusion, the available data support a model in which CARMA1 phosphorylation at multiple sites by the S/T kinases PKC β/θ, IKKβ, HPK1 and CaMKII trigger CARMA1 activation by regulating the accessibility of the effector CARD motif. Phosphorylation at residues T110, S608, and S637 may mediate autorepression, as mutation of these sites augmented the constitutive or inducible CARMA1-mediated IKK activity; the inhibitory mechanisms responsible for such an effect remain to be explored.

MULTIPLE FUNCTIONS OF BCL10 IN LYMPHOCYTE ACTIVATION

Genetic evidence suggests that the adaptor protein BCL10 performs non-redundant functions in a number of disparate biological pathways, such as normal development of B1 and marginal zone B cells (Ruland et al. 2001; Xue et al. 2003; Li et al. 2009), AgR-dependent activation of naïve lymphocytes (Ruland et al. 2001), and neural tube closure and normal brain development in mice (Ruland et al. 2001). Some of these BCL10 functions appear to be independent of association with CARMA1 and MALT1 (Thome and Weil 2007) (Fig. 3). For example, AgR triggering results in rapid BCL10 phosphorylation at S138 and another, unidentified residue (Rueda et al. 2007). These phosphorylation events are required for TCR-induced actin polymerization, cellular spreading and the stabilization of the immunological synapse, but occur independently of CARMA1 and MALT1 (Rueda et al. 2007) (Fig. 3A). It is also likely that BCL10 performs additional, CARMA1- and MALT1- independent functions in neuronal development, which is normal in mice deficient for CARMA1 or MALT1 (Egawa et al. 2003; Hara et al. 2003; Ruefli-Brasse et al. 2003; Ruland et al. 2003). Cooperation of all three proteins is required for AgR-dependent engagement of the NF-κB and JNK signaling pathways in lymphocytes (Fig. 3B and C). While the relevance of AgR-dependent JNK activation is not yet precisely understood (Rincon and Pedraza-Alva 2003; Blonska et al. 2006), numerous studies support the critical function of activated NF-κB in the adaptive immune response (Li and Verma 2002; Thome 2004), and several recent studies document the contribution of CBM proteins to NF-κB activation (Rawlings et al. 2006; Schulze-Luehrmann and Ghosh 2006; Thome and Weil 2007; Thome 2008). Molecular events directing BCL10 and MALT1 activation are still somewhat unclear, but several lines of evidence suggest that T cell triggering via both, the TCR/CD3 complex and CD28 mobilizes the pool of BCL10 constitutively associated with MALT1 (Uren et al. 2000; Gaide et al. 2002; Shinohara et al. 2005; Su et al. 2005; Wegener et al. 2006; Oeckinghaus et al. 2007). This is likely to require a phosphorylation-regulated conformational change in CARMA1 that exposes its CARD motif and allows interaction with the BCL10 CARD motif (Matsumoto et al. 2005; Rueda and Thome 2005; Sommer et al. 2005). The resulting CARMA1-BCL10-MALT1 (CBM) complex may be stabilized by interaction between the CARMA1 coiled coil motif and a C-terminal MALT1 region that lacks the DD and first two Ig domains (Che et al. 2004). Mechanisms by which CBM-associated BCL10 supports lymphocyte activation are not completely understood. Ubiquitination of BCL10 by the MALT1-binding ubiquitin ligase TRAF6 may regulate this function (Wu and Ashwell 2008). Ubiquitinated BCL10 may recruit the IKK complex via the ubiquitin-binding domain of the IKK subunit IKKγ, and this may promote further IKK activation by TRAF6-dependent ubiquitination (Sun et al. 2004; Wu and Ashwell 2008) (Fig. 3B). Additional BCL10 ubiquitination events may target BCL10 for lysosomal or proteasomal degradation upon its IKK mediated phosphorylation (Scharschmidt et al. 2004; Lobry et al. 2007). Together with CARMA1, BCL10 is required for the activation of the protease activity of MALT1 (Rebeaud et al. 2008), which contributes to NF-κB activation in an IKK-independent manner (see below). Finally, work from our laboratory demonstrated that MALT1-dependent cleavage of BCL10 affects β1 integrin-dependent T-cell adhesion by an unknown mechanism (Rebeaud et al. 2008) (Fig. 3C). This suggests that CBM proteins may participate not only in modulating NF-κB-dependent gene regulation, but also in efficient immune synapse formation and lymphocyte retention, positioning, migration and extravasation (Sixt et al. 2006).

Figure 3.

Overview of the multiple functions of BCL10 and its binding partners. (A) T-cell receptor (TCR) triggering leads to the rapid phosphorylation of BCL10, which is likely to control TCR-induced actin polymerization in a CARMA1- and MALT1-independent manner. (B) TCR/CD28 costimulation induces formation of the CBM complex, which controls IKK mediated NF-κB activation by promoting the activation of the IKK complex. Within this complex, MALT1-bound TRAF6 is thought to mediate K63-linked ubiquitination of BCL10 and MALT1, promoting recruitment of the IKK complex via the ubiquitin-binding IKKγ subunit. Additionally, TRAF6-mediated ubiquitination of IKKγ may contribute to IKK activation. (C) CBM complex formation is required for the activation of MALT1 protease function. BCL10 serves as a substrate of MALT1; its cleavage may regulate β1 integrin-mediated T-cell adhesion.

REGULATION OF LYMPHOCYTE ACTIVATION BY MALT1

MALT1 is a scaffold protein that activates the NF-κB-regulating IKK complex by physically bridging activated CARMA1 with BCL10 and TRAF6 (Thome 2008). The first evidence indicating a role for MALT1 in NF-κB activation came from two studies showing MALT1 and BCL10 synergistically activated NF-κB in 293T cell reporter assays (Uren et al. 2000; Lucas et al. 2001). Studies with MALT1 knock-out mice revealed that MALT1 controls AgR-dependent NF-κB activation in B- and T cells (Ruefli-Brasse et al. 2003; Ruland et al. 2003), as well as NF-κB activity downstream of other receptors with immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs, such as Fc and NK receptors and of some G-protein coupled receptors (Wegener and Krappmann 2007; Thome 2008). Moreover, MALT1 plays an important pathogenic role in the development of specific types of B-cell lymphomas (see below). The molecular mechanism engaged by MALT1 to control NF-κB activation in normal and malignant lymphocytes is thus a matter of considerable interest. Recent studies suggest that MALT1-dependent NF-κB activation is mediated by both scaffold and a protease functions (Thome 2008). The scaffold function of MALT1 depends upon its multiple protein-protein interaction domains (Uren et al. 2000; Lucas et al. 2001; Sun et al. 2004; Noels et al. 2007) (Figs. 1 and 3). MALT1 contains a central caspase-like domain, together with a death domain (DD), three immunoglobulin domains and a C-terminal extension. The MALT1 C-terminal Ig domain and extension contain two binding motifs for TRAF6 (Sun et al. 2004). Presently no binding partner of the DD has been identified, however, the two immunoglobulin (Ig)-like domains following the DD are required for constitutive binding to BCL10 (Lucas et al. 2001) (Fig. 1). The C-terminal Ig domain and the remaining C-terminal extension contain two binding motifs for TRAF6 (Sun et al. 2004; Noels et al. 2007). A third TRAF6 binding site within the second immunoglobulin-like domain of MALT1 was recently identified in a MALT1 fusion protein present in MALT lymphoma (Noels et al. 2007). TRAF6 is a ubiquitin ligase that plays a central role in the IKK-dependent canonical NF-κB pathway (Deng et al. 2000; Kobayashi et al. 2004; Sun et al. 2004). It may activate NF-κB signaling compounds by K63-linked (non degradative) polyubiquitination (Deng et al. 2000; Kobayashi et al. 2004). Interestingly, the MALT1 region C-terminal to its protease domain contains multiple ubiquitination sites that can be ubiquitinated by TRAF6 and thereby contribute to the physical recruitment of the IKK complex (Oeckinghaus et al. 2007) (Fig. 3B). A two-hybrid approach demonstrated MALT1 directly binds to the coiled-coil domain of CARMA1 (Che et al. 2004), suggesting such an interaction aids in formation or stabilization of the CBM complex. Within the frame of the CBM complex, MALT1 also bound to caspase-8 and FADD (Su et al. 2005; Misra et al. 2007), but the exact nature and functional relevance of such interactions remains poorly understood (Hailfinger et al. 2009b).

MALT1 PROTEASE ACTIVITY AND NF-κB ACTIVATION

MALT1 was originally identified through a caspase homology search, and called paracaspase because of its homology to mammalian caspases and to an additional family of caspase-like proteins known as metacaspases that are found in yeast, plants and parasites (Uren et al. 2000). MALT1 shares with these protease families the presence of conserved Cys and His residues predicted to be important for catalytic activity (Uren et al. 2000). Attempts to demonstrate MALT1 protease activity were initially unsuccessful (Uren et al. 2000; Snipas et al. 2004), but such activity was recently demonstrated using MALT1 oligomerization-inducing conditions and optimized substrates (Coornaert et al. 2008; Rebeaud et al. 2008). These studies established that, in contrast to caspases, which cleave their substrates after a negatively-charged Asp residue, MALT1 cleaves protein or peptide substrates after a positively-charged Arg residue. In this respect, MALT1 more closely resembles members of the metacaspase family, that cleave substrates after Arg or Lys residues (Vercammen et al. 2007). In keeping with this, MALT1 shares with metacaspases the presence of amino-acid residues directing Arg or Lys specificity (Vercammen et al. 2007).

The mechanism by which MALT1 protease activity regulates lymphocyte activation is a matter of intense investigation. Initial over-expression experiments in 293T cells showed that mutation in the predicted MALT1 active site Cys 464 reduced its ability to activate an NF-κB reporter (Uren et al. 2000; Lucas et al. 2001), suggesting that MALT1-dependent cleavage of unknown substrate(s) may be required for optimal NF-κB activation. Surprisingly however, treatment with a cell-permeable MALT1 protease inhibitor did not affect IκB phosphorylation by the IKK complex (Rebeaud et al. 2008; Duwel et al. 2009). This suggests that the protease activity of MALT1 potentiates NF-κB activation in an IKK-independent manner, at a crucial step downstream of, or parallel to, the IKK complex. The two known MALT1 substrates, BCL10 and A20, are unlikely to mediate this effect. BCL10 cleavage regulated T-cell adhesion but was largely dispensable for NF-κB activation (see above) (Rebeaud et al. 2008). The exact role of A20 cleavage is not well understood. A20 inhibits TCR-mediated IKK activation (Duwel et al. 2009), most likely via its ability to remove K63-linked poly-ubiquitination from the ubiquitin ligase TRAF6, the IKKγ subunit and MALT1 itself (Heyninck and Beyaert 2005; Duwel et al. 2009). MALT1 activity was required for the cleavage of a small fraction of total A20, but dispensable for down-modulation of total A20 levels in activated T cells (Coornaert et al. 2008; Duwel et al. 2009). Thus, both the predominant role of A20 in IKK-dependent NF-κB activation and the small proportion of A20 cleavage argue against a major role for A20 in the IKK-independent control of NF-κB activity by MALT1 protease activity.

Therefore, the substrate responsible for MALT1 protease-dependent NF-κB activation remains to be identified. It is possible that this substrate specifically affects c-Rel but not RelA activation, as a recent study using MALT1 deficient B cells demonstrated impaired c-Rel activation in B cells (Ferch et al. 2007). Surprisingly, this correlated with reduced IκBβ but not IκBα degradation (Ferch et al. 2007), implying a role for MALT1 in IκBβ-dependent c-Rel activation, but the exact role of the MALT1 protease activity in this process remains to be tested.

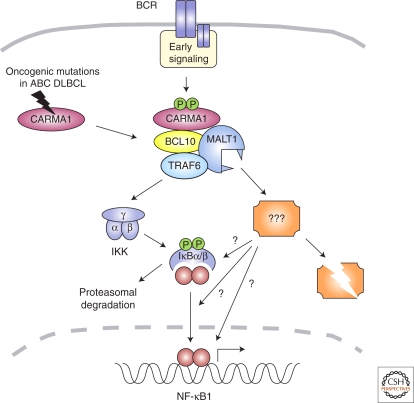

In conclusion, the presently available experimental evidence suggests that the protease activity of MALT1 controls NF-κB activation in an IKK-independent manner, either by affecting IκBβ stability, or by controlling other events required for the nuclear translocation or transcriptional activity of NF-κB1 complexes (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Proposed model for MALT1 function in NF-κB activation. B-cell receptor (BCR) stimulation induces formation of the CBM complex, which controls NF-κB activation through at least two different mechanisms. The scaffold function of BCL10 and MALT1 are required for TRAF6 recruitment and ubiquitination-dependent activation of the IKK complex, which phosphorylates IκB proteins. The protease activity of MALT1 also contributes to NF-κB activation in an IKK-independent manner, through cleavage of an unknown substrate (???). This might control IκBβ degradation, which occurs with slower kinetics than IκBα degradation and is sustained (Whiteside and Israel 1997), possibly because it depends on additional signaling events. Alternatively, MALT1 protease activity might control NF-κB1 activation at the level of its nuclear translocation or transcriptional activity. The presence of oncogenic mutations in CARMA1 or its upstream regulators may render this pathway constitutively active in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the activated B-cell type (ABC DLBCL) (see text for details).

CBM PROTEINS AND LYMPHOMAS

Given the critical role for CBM proteins and the NF-κB pathway in the control of lymphocyte survival and proliferation, it is not surprising to find altered expression and/or function of CBM proteins in specific types of B-cell lymphomas (Isaacson and Du 2004; Zhou et al. 2005; Noels et al. 2007; Sagaert et al. 2007; Coornaert et al. 2008; Lenz et al. 2008; Compagno et al. 2009; Ferch et al. 2009; Hailfinger et al. 2009a). Lymphomas of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphomas) are derived from extranodal marginal zone B cells and arise typically in mucosal or non-mucosal sites as a result of chronic infection or inflammation (Sagaert et al. 2007). Such lymphomas were associated with chromosomal translocations of the genes encoding BCL10 or MALT1. These are thought to result in overexpression of BCL10 or MALT1 or in the generation of fusion proteins containing the C-terminal part of MALT1 and the N-terminal part of the cellular inhibitor of apoptosis protein-2 (cIAP2) (Isaacson and Du 2004; Sagaert et al. 2007). Interestingly, the resulting cIAP2-MALT1 fusion proteins showed both constitutive MALT1 protease activity and NF-κB inducing capacity (Uren et al. 2000; Lucas et al. 2007; Coornaert et al. 2008), suggesting aberrant MALT1 activity drives the growth of these lymphomas. Altered CBM functions were also identified in another type of B-cell lymphoma, the diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) (Lenz et al. 2008; Compagno et al. 2009; Ferch et al. 2009; Hailfinger et al. 2009a). Constitutive activation of NF-κB is characteristic of the activated B-cell (ABC) subtype of DLBCL, which depends on NF-κB signals for survival and/or proliferation (Staudt and Dave 2005). Silencing of the expression of CARMA1, BCL10 or MALT1 led to reduced growth and induction of apoptosis in cell lines derived from ABC DLBCL (Ngo et al. 2006). Recently, two studies identified oncogenic CARMA1 mutations in patients with ABC DLBCL (Lenz et al. 2008; Compagno et al. 2009) and, less frequently, DLBCL of the germinal center B-cell type (Lenz et al. 2008; Compagno et al. 2009). We and others showed constitutive MALT1 activity in cell lines derived from ABC DLBCL (Ferch et al. 2009; Hailfinger et al. 2009a). Treatment of these cell lines with a MALT1 inhibitor specifically affected cellular growth by blocking NF-κB activity (Ferch et al. 2009; Hailfinger et al. 2009a), and in particular the nuclear translocation of c- Rel (Ferch et al. 2009). This suggests that constitutive CBM activity, induced by activating mutations in CARMA1 or its upstream regulators, drives constitutive NF-κB activity in these lymphomas (Fig. 4). Thus, the CBM signaling pathway, and in particular the protease activity of MALT1, reveals to be an interesting target for the development of specific anti-lymphoma drugs.

CONCLUSIONS

The past decade has witnessed dramatic progress in the characterization of signaling mechanisms controlling AgR-induced NF-κB signaling and downstream lymphocyte activation, development and tumorigenesis. A number of open questions remain and will be fertile ground for future studies. For example, the identification and characterization of additional MALT1 substrates, and further delineation of mechanisms directing MALT1 activity are currently hot topics. Further dissection of mechanisms that positively or negatively regulate pathway signaling components, and the precise regulation and function of individual NF-κB family members present other interesting aspects. Ultimately, novel enzymatic activities relevant to this pathway will require validation as new drug targets for immuno-suppression or treatment of lymphomas.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Kate Schroder for critical review of the manuscript. Research in the lab is supported by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation, the Swiss Cancer League and the foundations Leenaards, Pierre Mercier and Emma Muschamp. J.E.C. is supported by a PhD fellowship from the Faculty of Biology and Medicine of the University of Lausanne.

Footnotes

Editors: Lawrence E. Samelson and Andrey Shaw

Additional Perspectives on Immunoreceptor Signaling available at www.cshperspectives.org

REFERENCES

- Bertin J, Wang L, Guo Y, Jacobson MD, Poyet JL, Srinivasula SM, Merriam S, DiStefano PS, Alnemri ES 2001. CARD11 and CARD14 are novel caspase recruitment domain (CARD)/membrane- associated guanylate kinase (MAGUK) family members that interact with BCL10 and activate NF-kappa B. J Biol Chem 276: 11877–11882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidere N, Ngo VN, Lee J, Collins C, Zheng L, Wan F, Davis RE, Lenz G, Anderson DE, Arnoult D, et al. 2009. Casein kinase 1alpha governs antigen-receptor-induced NF-kappaB activation and human lymphoma cell survival. Nature 458: 92–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blonska M, Pappu BP, Matsumoto R, Li H, Su B, Wang D, Lin X 2006. The CARMA1-Bcl10 Signaling Complex Selectively Regulates JNK2 Kinase in the T Cell Receptor-Signaling Pathway. Immunity 26: 55–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonizzi G, Karin M 2004. The two NF-kappaB activation pathways and their role in innate and adaptive immunity. Trends Immunol 25: 280–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner D, Brechmann M, Rohling S, Tapernoux M, Mock T, Winter D, Lehmann WD, Kiefer F, Thome M, Krammer PH, et al. 2009. Phosphorylation of CARMA1 by HPK1 is critical for NF-kappaB activation in T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106: 14508–14513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Che T, You Y, Wang D, Tanner MJ, Dixit VM, Lin X 2004. MALT1/paracaspase is a signaling component downstream of CARMA1 and mediates T cell receptor-induced NF-kappaB activation. J Biol Chem 279: 15870–15876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compagno M, Lim WK, Grunn A, Nandula SV, Brahmachary M, Shen Q, Bertoni F, Ponzoni M, Scandurra M, Califano A, et al. 2009. Mutations of multiple genes cause deregulation of NF-kappaB in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Nature 459: 717–721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coornaert B, Baens M, Heyninck K, Bekaert T, Haegman M, Staal J, Sun L, Chen ZJ, Marynen P, Beyaert R 2008. T cell antigen receptor stimulation induces MALT1 paracaspase-mediated cleavage of the NF-kappaB inhibitor A20. Nature Immunol 9: 263–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costanzo A, Guiet C, Vito P 1999. c-E10 is a caspase-recruiting domain-containing protein that interacts with components of death receptors signaling pathway and activates nuclear factor-kappaB. J Biol Chem 274: 20127–20132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng L, Wang C, Spencer E, Yang L, Braun A, You J, Slaughter C, Pickart C, Chen ZJ 2000. Activation of the IkappaB kinase complex by TRAF6 requires a dimeric ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme complex and a unique polyubiquitin chain. Cell 103: 351–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duwel M, Welteke V, Oeckinghaus A, Baens M, Kloo B, Ferch U, Darnay BG, Ruland J, Marynen P, Krappmann D 2009. A20 negatively regulates T cell receptor signaling to NF-kappaB by cleaving Malt1 ubiquitin chains. J Immunol 182: 7718–7728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egawa T, Albrecht B, Favier B, Sunshine MJ, Mirchandani K, O’Brien W, Thome M, Littman DR 2003. Requirement for CARMA1 in antigen receptor-induced NF-kappa B activation and lymphocyte proliferation. Curr Biol 13: 1252–1258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng W, Zhang M 2009. Organization and dynamics of PDZ-domain-related supramodules in the postsynaptic density. Nat Rev Neurosci 10: 87–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferch U, Kloo B, Gewies A, Pfander V, Duwel M, Peschel C, Krappmann D, Ruland J 2009. Inhibition of MALT1 protease activity is selectively toxic for activated B cell-like diffuse large B cell lymphoma cells. J Exp Med 206: 2313–2320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferch U, zum Buschenfelde CM, Gewies A, Wegener E, Rauser S, Peschel C, Krappmann D, Ruland J 2007. MALT1 directs B cell receptor-induced canonical nuclear factor-kappaB signaling selectively to the c-Rel subunit. Nature Immunol 8: 4–991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funke L, Dakoji S, Bredt DS 2005. Membrane-associated guanylate kinases regulate adhesion and plasticity at cell junctions. Annual review of biochemistry 74: 219–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaide O, Favier B, Legler DF, Bonnet D, Brissoni B, Valitutti S, Bron C, Tschopp J, Thome M 2002. CARMA1 is a critical lipid raft-associated regulator of TCR-induced NF-kappa B activation. Nat Immunol 3: 836–843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaide O, Martinon F, Micheau O, Bonnet D, Thome M, Tschopp J 2001. Carma1, a CARD-containing binding partner of Bcl10, induces Bcl10 phosphorylation and NF-kappaB activation. FEBS Lett 496: 121–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hailfinger S, Lenz G, Ngo V, Posvitz-Fejfar A, Rebeaud F, Guzzardi M, Penas EM, Dierlamm J, Chan WC, Staudt LM, et al. 2009a. Essential role of MALT1 protease activity in activated B cell-like diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106: 19946–19951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hailfinger S, Rebeaud F, Thome M 2009b. Adapter and enzymatic functions of proteases in T-cell activation. Immunol Rev 232: 334–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara H, Wada T, Bakal C, Kozieradzki I, Suzuki S, Suzuki N, Nghiem M, Griffiths EK, Krawczyk C, Bauer B, et al. 2003. The MAGUK family protein CARD11 is essential for lymphocyte activation. Immunity 18: 763–775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyninck K, Beyaert R 2005. A20 inhibits NF-kappaB activation by dual ubiquitin-editing functions. Trends in biochemical sciences 30: 1–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann K, Bucher P, Tschopp J 1997. The CARD domain: a new apoptotic signalling motif. Trends in biochemical sciences 22: 155–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacson PG, Du MQ 2004. MALT lymphoma: from morphology to molecules. Nat Rev Cancer 4: 644–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiguro K, Ando T, Goto H, Xavier R 2007. Bcl10 is phosphorylated on Ser138 by Ca(2+)/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Mol Immunol 44: 2105–2110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiguro K, Green T, Rapley J, Wachtel H, Giallourakis C, Landry A, Cao Z, Lu N, Takafumi A, Goto H, et al. 2006. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II is a modulator of CARMA1-mediated NF-kappaB activation. Mol Cell Biol 26: 5497–5508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jun JE, Wilson LE, Vinuesa CG, Lesage S, Blery M, Miosge LA, Cook MC, Kucharska EM, Hara H, Penninger JM, et al. 2003. Identifying the MAGUK protein Carma-1 as a central regulator of humoral immune responses and atopy by genome-wide mouse mutagenesis. Immunity 18: 751–762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin M, Cao Y, Greten FR, Li ZW 2002. NF-kappaB in cancer: from innocent bystander to major culprit. Nat Rev Cancer 2: 301–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klemm S, Gutermuth J, Hultner L, Sparwasser T, Behrendt H, Peschel C, Mak TW, Jakob T, Ruland J 2006. The Bcl10-Malt1 complex segregates Fc epsilon RI-mediated nuclear factor kappa B activation and cytokine production from mast cell degranulation. J Exp Med 203: 337–347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T, Walsh MC, Choi Y 2004. The role of TRAF6 in signal transduction and the immune response. Microbes Infect 6: 1333–1338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koseki T, Inohara N, Chen S, Carrio R, Merino J, Hottiger MO, Nabel GJ, Nunez G 1999. CIPER, a novel NF kappaB-activating protein containing a caspase recruitment domain with homology to Herpesvirus-2 protein E10. J Biol Chem 274: 9955–9961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langel FD, Jain NA, Rossman JS, Kingeter LM, Kashyap AK, Schaefer BC 2008. Multiple protein domains mediate interaction between Bcl10 and MALT1. J Biol Chem 283: 32419–32431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KY, D’Acquisto F, Hayden MS, Shim JH, Ghosh S 2005. PDK1 nucleates T cell receptor-induced signaling complex for NF-kappaB activation. Science 308: 114–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenz G, Davis RE, Ngo VN, Lam L, George TC, Wright GW, Dave SS, Zhao H, Xu W, Rosenwald A, et al. 2008. Oncogenic CARD11 Mutations in Human Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma. Science. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Verma IM 2002. NF-kappaB regulation in the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol 2: 725–734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Wang H, Xue L, Shin DM, Roopenian D, Xu W, Qi CF, Sangster MY, Orihuela CJ, Tuomanen E, et al. 2009. Emu-BCL10 mice exhibit constitutive activation of both canonical and noncanonical NF-kappaB pathways generating marginal zone (MZ) B-cell expansion as a precursor to splenic MZ lymphoma. Blood 114: 4158–4168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobry C, Lopez T, Israël A, Weil R 2007. Negative feed back loop in T-cell activation through IkappaB kinase-induced phosphorylation and degradation of Bcl10. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104: 908–913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas PC, Kuffa P, Gu S, Kohrt D, Kim DS, Siu K, Jin X, Swenson J, McAllister-Lucas LM 2007. A dual role for the API2 moiety in API2-MALT1-dependent NF-kappaB activation: heterotypic oligomerization and TRAF2 recruitment. Oncogene 26: 5643–5654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas PC, Yonezumi M, Inohara N, McAllister-Lucas LM, Abazeed ME, Chen FF, Yamaoka S, Seto M, Nunez G 2001. Bcl10 and MALT1, independent targets of chromosomal translocation in malt lymphoma, cooperate in a novel NF-kappa B signaling pathway. J Biol Chem 276: 19012–19019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto R, Wang D, Blonska M, Li H, Kobayashi M, Pappu B, Chen Y, Lin X 2005. Phosphorylation of CARMA1 plays a critical role in T Cell receptor-mediated NF-kappaB activation. Immunity 23: 575–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllister-Lucas LM, Inohara N, Lucas PC, Ruland J, Benito A, Li Q, Chen S, Chen FF, Yamaoka S, Verma IM, et al. 2001. Bimp1, a MAGUK family member linking protein kinase C activation to Bcl10-mediated NF-kappaB induction. J Biol Chem 276: 30589–30597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee AW, Dakoji SR, Olsen O, Bredt DS, Lim WA, Prehoda KE 2001. Structure of the SH3-guanylate kinase module from PSD-95 suggests a mechanism for regulated assembly of MAGUK scaffolding proteins. Mol Cell 8: 1291–1301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misra RS, Russell JQ, Koenig A, Hinshaw-Makepeace JA, Wen R, Wang D, Huo H, Littman DR, Ferch U, Ruland J, et al. 2007. Caspase-8 and c-FLIPL associate in lipid rafts with NF-kappaB adaptors during T cell activation. J Biol Chem 282: 19365–19374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Garcia ME, Sommer K, Haftmann C, Sontheimer C, Andrews SF, Rawlings DJ 2009. Serine 649 phosphorylation within the protein kinase C-regulated domain down-regulates CARMA1 activity in lymphocytes. J Immunol 183: 7362–7370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayan P, Holt B, Tosti R, Kane LP 2006. CARMA1 is required for Akt-mediated NF-kappaB activation in T cells. Mol Cell Biol 26: 2327–2336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton K, Dixit VM 2003. Mice lacking the CARD of CARMA1 exhibit defective B lymphocyte development and impaired proliferation of their B and T lymphocytes. Curr Biol 13: 1247–1251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngo VN, Davis RE, Lamy L, Yu X, Zhao H, Lenz G, Lam LT, Dave S, Yang L, Powell J, et al. 2006. A loss-of-function RNA interference screen for molecular targets in cancer. Nature 441: 106–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noels H, van Loo G, Hagens S, Broeckx V, Beyaert R, Marynen P, Baens M 2007. A Novel TRAF6 Binding Site in MALT1 Defines Distinct Mechanisms of NF-kappaB Activation by API2-MALT1 Fusions. J Biol Chem 282: 10180–10189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oeckinghaus A, Wegener E, Welteke V, Ferch U, Arslan SC, Ruland J, Scheidereit C, Krappmann D 2007. Malt1 ubiquitination triggers NF-kappaB signaling upon T-cell activation. EMBO J 26: 4634–4645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantz JL, Denny EM, Baltimore D 2002. CARD11 mediates factor-specific activation of NF-kappaB by the T cell receptor complex. EMBO J 21: 5184–5194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponting CP, Phillips C, Davies KE, Blake DJ 1997. PDZ domains: targeting signalling molecules to sub-membranous sites. Bioessays 19: 469–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawlings DJ, Sommer K, Moreno-Garcia ME 2006. The CARMA1 signalosome links the signalling machinery of adaptive and innate immunity in lymphocytes. Nature reviews 6: 799–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebeaud F, Hailfinger S, Posevitz-Fejfar A, Tapernoux M, Moser R, Rueda D, Gaide O, Guzzardi M, Iancu EM, Rufer N, et al. 2008. The proteolytic activity of the paracaspase MALT1 is key in T cell activation. Nature Immunol 9: 272–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rincon M, Pedraza-Alva G 2003. JNK and p38 MAP kinases in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Immunol Rev 192: 131–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueda D, Gaide O, Ho L, Lewkowicz E, Niedergang F, Hailfinger S, Rebeaud F, Guzzardi M, Conne B, Thelen M, et al. 2007. Bcl10 controls TCR- and FcgammaR-induced actin polymerization. J Immunol 178: 4373–4384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueda D, Thome M 2005. Phosphorylation of CARMA1: the link(er) to NF-kappaB activation. Immunity 23: 551–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruefli-Brasse AA, French DM, Dixit VM 2003. Regulation of NF-kappaB-dependent lymphocyte activation and development by paracaspase. Science 302: 1581–1584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruland J, Duncan GS, Elia A, del Barco Barrantes I, Nguyen L, Plyte S, Millar DG, Bouchard D, Wakeham A, Ohashi PS, et al. 2001. Bcl10 is a positive regulator of antigen receptor-induced activation of NF-kappaB and neural tube closure. Cell 104: 33–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruland J, Duncan GS, Wakeham A, Mak TW 2003. Differential requirement for Malt1 in T and B cell antigen receptor signaling. Immunity 19: 749–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagaert X, De Wolf-Peeters C, Noels H, Baens M 2007. The pathogenesis of MALT lymphomas: where do we stand? Leukemia 21: 389–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharschmidt E, Wegener E, Heissmeyer V, Rao A, Krappmann D 2004. Degradation of Bcl10 induced by T-cell activation negatively regulates NF-kappa B signaling. Mol Cell Biol 24: 3860–3873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze-Luehrmann J, Ghosh S 2006. Antigen-receptor signaling to nuclear factor kappa B. Immunity 25: 701–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara H, Maeda S, Watarai H, Kurosaki T 2007. IkappaB kinase beta-induced phosphorylation of CARMA1 contributes to CARMA1 Bcl10 MALT1 complex formation in B cells. J Exp Med 204: 3285–3293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara H, Yasuda T, Aiba Y, Sanjo H, Hamadate M, Watarai H, Sakurai H, Kurosaki T 2005. PKC beta regulates BCR-mediated IKK activation by facilitating the interaction between TAK1 and CARMA1. J Exp Med 202: 1423–1431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sixt M, Bauer M, Lammermann T, Fassler R 2006. Beta1 integrins: zip codes and signaling relay for blood cells. Curr Opin Cell Biol 18: 482–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snipas SJ, Wildfang E, Nazif T, Christensen L, Boatright KM, Bogyo M, Stennicke HR, Salvesen GS 2004. Characteristics of the caspase-like catalytic domain of human paracaspase. Biol Chem 385: 1093–1098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer K, Guo B, Pomerantz JL, Bandaranayake AD, Moreno-Garcia ME, Ovechkina YL, Rawlings DJ 2005. Phosphorylation of the CARMA1 linker controls NF-kappaB activation. Immunity 23: 561–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasula SM, Ahmad M, Lin JH, Poyet JL, Fernandes-Alnemri T, Tsichlis PN, Alnemri ES 1999. CLAP, a novel caspase recruitment domain-containing protein in the tumor necrosis factor receptor pathway, regulates NF-kappaB activation and apoptosis. J Biol Chem 274: 17946–17954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staudt LM, Dave S 2005. The biology of human lymphoid malignancies revealed by gene expression profiling. Adv Immunol 87: 163–208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su H, Bidere N, Zheng L, Cubre A, Sakai K, Dale J, Salmena L, Hakem R, Straus S, Lenardo M 2005. Requirement for caspase-8 in NF-kappaB activation by antigen receptor. Science 307: 1465–1468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Deng L, Ea CK, Xia ZP, Chen ZJ 2004. The TRAF6 ubiquitin ligase and TAK1 kinase mediate IKK activation by BCL10 and MALT1 in T lymphocytes. Mol Cell 14: 289–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner MJ, Hanel W, Gaffen SL, Lin X 2007. CARMA1 Coiled-coil domain is involved in the oligomerization and subcellular localization of CARMA1, and is required for T cell receptor-induced NF-kappa B activation. J Biol Chem 282: 17141–17147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavares GA, Panepucci EH, Brunger AT 2001. Structural characterization of the intramolecular interaction between the SH3 and guanylate kinase domains of PSD-95. Mol Cell 8: 1313–1325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thome M 2004. CARMA1, BCL-10 and MALT1 in lymphocyte development and activation. Nature reviews 4: 348–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thome M 2008. Multifunctional roles for MALT1 in T-cell activation. Nature Rev Immunol 8: 495–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thome M, Martinon F, Hofmann K, Rubio V, Steiner V, Schneider P, Mattmann C, Tschopp J 1999. Equine herpesvirus-2 E10 gene product, but not its cellular homologue, activates NF-kappaB transcription factor and c-Jun N-terminal kinase. J Biol Chem 274: 9962–9968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thome M, Tschopp J 2003. TCR-induced NF-kB activation: a crucial role for Carma1, Bcl10 and MALT1. Trends Immunol (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thome M, Weil R 2007. Post-translational modifications regulate distinct functions of CARMA1 and BCL10. Trends Immunol 28: 281–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uren AG, O’Rourke K, Aravind LA, Pisabarro MT, Seshagiri S, Koonin EV, Dixit VM 2000. Identification of paracaspases and metacaspases: two ancient families of caspase-like proteins, one of which plays a key role in MALT lymphoma. Mol Cell 6: 961–967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vercammen D, Declercq W, Vandenabeele P, Van Breusegem F 2007. Are metacaspases caspases? J Cell Biol 179: 375–380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Matsumoto R, You Y, Che T, Lin XY, Gaffen SL, Lin X 2004. CD3/CD28 costimulation-induced NF-kappaB activation is mediated by recruitment of protein kinase C-theta, Bcl10, and IkappaB kinase beta to the immunological synapse through CARMA1. Mol Cell Biol 24: 164–171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber CH, Vincenz C 2001. The death domain superfamily: a tale of two interfaces? Trends in biochemical sciences 26: 475–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegener E, Krappmann D 2007. CARD-Bcl10-Malt1 signalosomes: missing link to NF-kappaB. Sci STKE 2007: e21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegener E, Oeckinghaus A, Papadopoulou N, Lavitas L, Schmidt-Supprian M, Ferch U, Mak TW, Ruland J, Heissmeyer V, Krappmann D 2006. Essential role for IkappaB kinase beta in remodeling Carma1-Bcl10-Malt1 complexes upon T cell activation. Mol Cell 23: 13–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wertz IE, O’Rourke KM, Zhou H, Eby M, Aravind L, Seshagiri S, Wu P, Wiesmann C, Baker R, Boone DL, et al. 2004. De-ubiquitination and ubiquitin ligase domains of A20 downregulate NF-kappaB signalling. Nature 430: 694–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside ST, Israel A 1997. I kappa B proteins: structure, function and regulation. Semin Cancer Biol 8: 75–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis TG, Jadayel DM, Du MQ, Peng H, Perry AR, Abdul-Rauf M, Price H, Karran L, Majekodunmi O, Wlodarska I, et al. 1999. Bcl10 is involved in t(1;14)(p22;q32) of MALT B cell lymphoma and mutated in multiple tumor types [see comments]. Cell 96: 35–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu CJ, Ashwell JD 2008. NEMO recognition of ubiquitinated Bcl10 is required for T cell receptor-mediated NF-{kappa}B activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105: 3023–3028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue L, Morris SW, Orihuela C, Tuomanen E, Cui X, Wen R, Wang D 2003. Defective development and function of Bcl10-deficient follicular, marginal zone and B1 B cells. Nat Immunol 4: 857–865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaffe MB 2001. MAGUK SH3 Domains—Swapped and Stranded by Their Kinases? Structure 10: 3–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan M, Lee J, Schilbach S, Goddard A, Dixit V 1999. mE10, a novel caspase recruitment domain-containing proapoptotic molecule. J Biol Chem 274: 10287–10292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Siebert R, Yan M, Hinzmann B, Cui X, Xue L, Rakestraw KM, Naeve CW, Beckmann G, Weisenburger DD, et al. 1999. Inactivating mutations and overexpression of BCL10, a caspase recruitment domain-containing gene, in MALT lymphoma with t(1;14)(p22;q32). Nat Genet 22: 63–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H, Du MQ, Dixit VM 2005. Constitutive NF-kappaB activation by the t(11;18)(q21;q21) product in MALT lymphoma is linked to deregulated ubiquitin ligase activity. Cancer Cell 7: 425–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]