Abstract

Fusarium is a saprophytic organism that is found widely distributed in soil, subterranean and aerial plants, plant debris and other organic substrates. The organism can cause local tissue infections in immunocompetent patients such as onychomycosis, bone and joint infections, or sinusitis. Since the first case of disseminated Fusarium was described, the incidence of disseminated disease has increased significantly, particularly affecting those immunocompromised with hematological malignancies. We report here a 38 year-old hospitalized male with newly diagnosed acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) who developed disseminated Fusarium infection, originating from a toenail paronychia, in the setting of neutropenia. Pathological diagnosis of Fusarium is difficult because the septate hyphae of Fusarium are difficult to distinguish from Aspergillus, which has a more favorable outcome. Cultures of potential sources of infection, as well as tissue cultures, are essential in identifying the organism and initiating early aggressive therapy.

Introduction

Fusarium is a saprophytic organism that is found widely distributed in soil, subterranean and aerial plants, plant debris and other organic substrates that can cause local tissue infections in immunocompetent patients such as onychomycosis, bone and joint infections, or sinusitis. Fusarium spores enter a host via inhalation or settle into areas of skin breakdown or mucosal membranes. They are also associated with foreign bodies, causing keratitis in contact lens wearers, peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis patients, and fungemia associated with catheters1. Since the first case of disseminated fusariosis described by Cho et al. in 19732, the incidence of disseminated disease has increased significantly, particularly affecting those immunocompromised with hematological malignancies3. Typically, the extent of disease depends on the immune status of the patient. Patients with hematological malignancies that develop neutropenia secondary to chemotherapy or immunosuppression secondary to corticosteroid treatment for graft-versus-host-disease are at greatest risk for disseminated Fusarium infection, which tend to infect the host primarily through the respiratory tract and skin. 1,4-8

Case Report

A 38 year-old hospitalized male with newly diagnosed acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) underwent chemotherapy and subsequently developed pancytopenia and fevers. His fevers were unresponsive to piperacillin/tazobactam, vancomycin, and fluconazole. Despite numerous cultures of blood, urine and sputum, no source of the infection was initially found. After 3 to 4 days of persistent fevers, he developed nontender, nonpruritic erythematous nodules on his right shin, right shoulder (Figure 1), scalp and abdomen. The right great toenail had purulent drainage with surrounding edema and erythematous plaque that tracked up his dorsal foot (Figure 2). No plantar scale, bullae, pustules or interdigital maceration was noted. A punch biopsy of one of the lesions showed a superficial and deep perivascular dermatitis accompanied by mild perivascular dermal hemorrhage. A periodic acid-Schiff stain of this biopsy revealed septate hyphae and reproductive structures suggestive of chlamydospores in the reticular dermis associated with dermal blood vessels (Figure 3). A culture from the right toenail grew Fusarium spp., and a tissue culture from one of the erythematous nodules also grew Fusarium spp. Imaging of the sinuses did not show sinusitis; CT of the chest, abdomen and pelvis revealed numerous hypodensities in the liver, spleen, and lungs. The patient was treated with amphotericin B and voriconazole. He also received granulocyte colony stimulating factor to increase his neutrophil count. At discharge, the patient's nodules and paronychia had improved clinically, and no new skin lesions had developed. The patient was discharged on oral voriconazole. Despite continued antifungal therapy, the patient died suddenly at home within a month of discharge from the hospital. This clinical scenario suggests that the disseminated Fusarium originated from the toenail paronychia.

Figure 1.

Erythematous, firm nodule on right shoulder. Similar lesions were also found on the right forearm, scalp and abdomen. The lesions developed central necrosis after four days.

Figure 2.

The right great toenail had purulent drainage with surrounding edema and erythema that tracked up the dorsal foot.

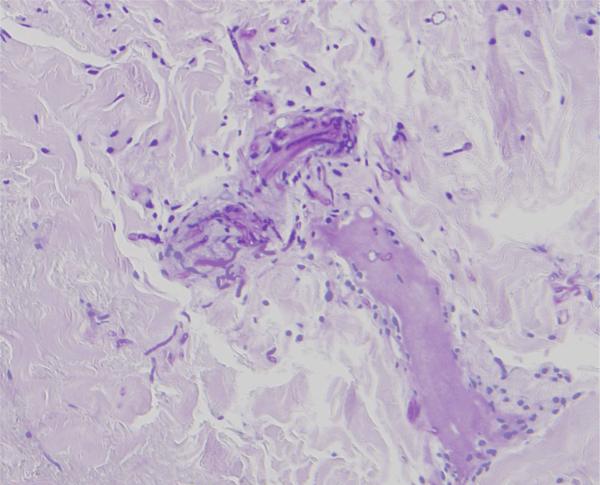

Figure 3.

Periodic acid-Schiff stain shows septate hyphae and reproductive structures suggestive of chlamydospores in the reticular dermis associated with dermal blood vessels. (PAS, original magnification x )

Comment

The characteristics of disseminated Fusarium include skin lesions and positive blood cultures with or without pneumonia. Infection occurs in the immunocompromised patient with prolonged (>10 days) and profound (<100/mm3) neutropenia. Infection may additionally occur in hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients with normal neutrophil counts who are severely immunosuppressed by corticosteroids to treat graft-versus-host-disease.4,6,8,9 Fusarium enters through the skin through local breakdown due to wounds, insect bites or onychomycosis. Usually, a localized infection will be found on hands, feet, and distal extremities and can appear as onychomycosis only or develop further in immunocompromised patients into cellulitis that can lead to disseminated disease.6,8,10 Fusarium solani is the most common species recovered, followed by F. oxysporum, F. moniliforme and F. verticillioidis.8 Studies show that skin lesions are present in greater than 70% of reported cases of fusariosis.5,6,9,11 The lesions of disseminated disease evolve from tender red or gray macules or papules to red or gray macules or papules with central eschar. They can progress further into a thick black eschar with an erythematous rim. The characteristic findings are caused by thrombosis of blood vessels by fusarial hyphae that leads to erythrocytic extravasation and eventual dermal necrosis and epidermal ulceration.10

Pathological diagnosis of Fusarium is difficult because the septate hyphae of Fusarium are difficult to distinguish from Aspergillus, which has a more favorable outcome and rarely has skin lesions1. Cultures of potential sources of infection, as well as tissue cultures, are essential in identifying the organism and initiating early aggressive therapy.8 Cutaneous lesions may precede positive blood cultures for up to 5 days.12 In addition to correctly identifying this pathogen, it is important assess the immune system of these individuals; this infection is often fatal in these patients without reconstitution of immune status. One study showed more disseminated skin lesions in neutropenic immunocompromised patients compared to non-neutropenic immunocompromised patients. Patients who were persistently neutropenic had a 100% mortality compared to 30% mortality in those who recovered from immunosuppression.11 A study of 84 hematologic disease patients with disseminated fusariosis revealed multivariate predictors of poor outcome to be persistent neutropenia and therapy with corticosteroids.5

Due to relative resistance to most antifungals, the lack of clinical trials, and the dependence on reconstitution of the host's immune system, Fusarium infections, especially if disseminated, are notoriously difficult to treat. Prevention of infection remains a key strategy in preventing a poor outcome. Recommendations include thorough skin evaluations before beginning immunosuppressive therapy, identifying any tissue breakdowns and culturing any suspicious lesions after therapy begins. Debridement or topical antifungals should be used for any local infections and avoidance of any Fusarium sources such as hospital faucets and showers.13 Disseminated fusariosis in severely immunocompromised patients is often treated with amphotericin B lipid complex but mortality remains above 70%.6,9 There are case reports of success using combination therapy of amphotericin B with caspofungin, amphotericin B with voriconazole, and amphotericin B with terbinafine .14-17 Voriconazole is considered the most efficacious against Fusarium.7 In vitro studies have shown that combination therapy of voriconazole with terbinafine is synergistic against Fusarim and that single agents were not effective.18,19 Although not standard of care, granulocyte transfusions, granulocyte-colony stimulating factor, or granulocyte-macrophage-colony stimulating factor should be considered with neutropenic patients with fusariosis. 6,8,20

Disseminated Fusarium infection is associated with a high mortality in immunocompromised patients, particularly those with neutropenia and is often fatal in these populations without reconstitution of immune status and appropriate antifungal therapy. Skin lesions are often characteristic and assist in the early diagnosis of disseminated disease. Cultures of potential sources of infection, as well as tissue cultures, are essential in identifying the organism and initiating early aggressive therapy.

References

- 1.Nelson PE, Dignani MC, Anaissie EJ. Taxonomy, biology, and clinical aspects of Fusarium species. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1994;7:479–504. doi: 10.1128/cmr.7.4.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cho CT, Vats TS, Lowman JT, et al. Fusarium solani infection during treatment for acute leukemia. J Pediatr. 1973;83:1028–1031. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(73)80543-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pontón J, Rüchel R, Clemons KV, et al. Emerging pathogens. Med Mycol. 2000;38:225–236. doi: 10.1080/mmy.38.s1.225.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nucci M, Anaissie E. Emerging fungi. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2006;20:563–579. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nucci M, Anaissie EJ, Queiroz-Telles F, et al. Outcome predictors of 84 patients with hematologic malignancies and Fusarium infection. Cancer. 2003;98:315–319. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boutati EI, Anaissie EJ. Fusarium, a significant emerging pathogen in patients with hematologic malignancy. Blood. 1997;3:999–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mays SR, Bogle MA, Bodey GP. Cutaneous fungal infections in the oncology patient: recognition and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7:31–43. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200607010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nucci M, Anaissie E. Fusarium infections in immunocompromised patients. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:695–704. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00014-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nucci M, Marr KA, Queiroz-Telles F, et al. Fusarium infection in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:1237–1242. doi: 10.1086/383319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bodey GP, Boktour M, Mays S, et al. Skin lesions associated with Fusarium infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:659–666. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.123489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nucci M, Anaissie E. Cutaneous infection by Fusarium species in healthy and immunocompromised hosts: implications for diagnosis and management. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:909–920. doi: 10.1086/342328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dignani MC, Anaissie E. Human fusariosis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2004;10:67–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1470-9465.2004.00845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anaissie EJ, Kuchar RT, Rex JH, et al. Fusariosis associated with pathogenic Fusarium species colonization of a hospital water system: a new paradigm for the epidemiology of opportunistic mold infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:1871–1878. doi: 10.1086/324501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ho DY, Lee JD, Rosso F, et al. Treating disseminated fusariosis: amphotericin B, voriconazole or both? Mycoses. 2007;50:227–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2006.01346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rothe A, Seibold M, Hoppe T, et al. Combination therapy of disseminated Fusarium oxysporum infection with terbinafine and amphotericin B. Ann Hematol. 2004;83:394–397. doi: 10.1007/s00277-003-0795-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stanzani M, Vianelli N, Bandini G, et al. Successful treatment of disseminated fusariosis after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation with the combination of voriconazole and liposomal amphotericin B. J Infect. 2006;53:243–246. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2006.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vagace JM, Sanz-Rodriguez C, Casado MS, et al. Resolution of disseminated fusariosis in a child with acute leukemia treated with combined antifungal therapy: a case report. BMC Infect Dis. 2007;7:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-7-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ortoneda M, Capilla J, Pastor FJ, et al. In vitro interactions of licensed and novel antifungal drugs against Fusarium spp. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2004;48:69–71. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Córdobaa S, Roderob L, Vivota W, et al. In vitro interactions of antifungal agents against clinical isolates of Fusarium spp. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008;31:171–174. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dignani MC, Anaissie EJ, Hester JP, et al. Treatment of neutropenia-related fungal infections with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor-elicited white blood cell transfusions: a pilot study. Leukemia. 1997;11:1621–1630. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2400811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]