Abstract

Utilizing part of the survey data collected for a National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA)–funded project from 29 public elementary schools in Phoenix, Arizona (N = 1,600), this study explored the underlying structure of Mexican-heritage youths’ ethnic identity and cultural/linguistic orientation. Latent profile and transition analyses identified four distinct orientation profiles endorsed by the early adolescents and their developmental trends across four time points. Most Mexican and Mexican American adolescents endorsed bicultural profiles with developmental trends characterized by widespread stasis and transitions toward greater ethnic identity exploration. Multinominal logistic regression analyses revealed associations between profile endorsement and adolescents’ gender, socioeconomic status, parents’ birthplace, and visits outside the United States. These findings are discussed in regard to previous findings on acculturation and ethnic identity development. Individuals’ adaptation to the immediate local environment is noted as a possible cause of prevalent biculturalism. Limitations and future directions for the research on ethnic identity development and acculturation are also discussed.

Keywords: acculturation, ethnic identity development, ethnolinguistic orientation, latent profile and transition analyses, Mexicans and Mexican Americans

The size and range of migration has expanded worldwide over the past few decades. According to the UN, about 175 million people lived in countries other than their native country at the turn of this century, a figure expected to double by 2025 (United Nations, 2002). In the United States, the number of children of immigrants increased by 47% during the period of 1990 to 1997, whereas that of the native-born counterparts increased by only 7% (Hernandez, 1999). The greatest percentage of U.S. immigrants originate in Central America, including Mexico (Larsen, 2004). As a result, Hispanics, primarily those with Mexican heritage, make up the most quickly growing segment of the U.S. population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2004).

Unsurprisingly, most immigrants experience substantial changes in their lives (Berry, 1997, 2004; Ward, Bochner, & Furnham, 2001). When migration occurs, acculturation, or the “meeting of cultures and the resulting change” (Sam & Berry, 2006, p. 1), is inevitable. Acculturation provides an enveloping experience that impacts individuals’ affect, behavior, and cognition (Ward et al., 2001). This acculturation experience extends to the children of immigrants, and sometimes later generations, especially in border settings where immigrating populations enter the host country, such as the southwestern cities in the United States (Kulis, Marsiglia, Sicotte, & Nieri, 2007). Though encountered by many, the developmental processes experienced by acculturating people are still unclear, calling for research that gauges those experiences.

Undertaking this challenge, the current research examines the developmental process of Mexican-heritage youths’ ethnic identity and cultural/linguistic orientations at the beginning of adolescence. We focus on this particular group because, as noted above, Mexican-heritage individuals constitute both one of the most rapidly growing populations and one of the most prominent immigrant groups in the United States, and research suggests that the impact of acculturation is most pronounced in adolescence (French, Seidman, Allen, & Aber, 2006). The current research examines ethnic identity and cultural/linguistic orientation as each represents an important psychological and behavioral aspect of acculturating individuals’ experiences (Masgoret & Ward, 2006). The following sections review relevant literature to illustrate the structure of each of those constructs and clarify the theoretical connections among them.

Ethnic Identity: Structure and Its Relationship With Acculturation

Structure of ethnic identity development

Whereas early studies on ethnic identity focused on the unique aspects of particular groups, recent research indicates some common structure underlying the general conception of ethnic identity that runs across a variety of ethnic groups (Phinney, Romero, Nava, & Huang, 2001). According to Phinney (1990, 1992), development of ethnic identity involves two interrelated mechanisms: exploration and affirmation/belonging.

Exploration refers to the behavioral aspects of one’s ethnic identity by which individuals make continuous efforts to learn about their ethnic group, its history, and its culture and talk to other members to gain knowledge of the group norms, customs, and values (Phinney, 1990). As the communication theory of identity suggests, such interactive maneuvers represent important aspects of identity, inseparable from one’s sense of who she or he is (Hecht, Warren, Jung, & Krieger, 2005). Affirmation/belonging refers to the psychological aspects of ethnic identity, including the affective feelings and cognitive perceptions attached to one’s group (Phinney, 1990). The desire for belongingness is one of the fundamental human needs (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Maslow, 1970) and, thus, group identity constitutes an important self-concept (Tajfel & Turner, 1986).

Research suggests that the two dimensions of ethnic identity entail distinct trajectories (Berry, Phinney, Sam, & Vedder, 2006). French et al. (2006) found that ethnic awareness and group esteem, which together signify the notion of affirmation/belonging (Phinney, 1992), develop in early adolescence, but exploration of ethnic identity occurs relatively later. French et al. explain that individuals become exposed to the customs and norms of their ethnic group early on, typically via child-parent contact (Kagitcibasi, 1996), and thereby face tacit but strong encouragement to internalize the group’s values and worldviews. In contrast, exploration requires one’s voluntary and deliberate efforts to search ethnic roots and typically occurs later (French et al., 2006). With either mechanism, although this identity development process may be instigated in a variety of ways, the experience of acculturation arising from immigration and/or growing up in a multicultural border community provides a significant triggering opportunity.

The relationship between ethnic identity development and acculturation

Immigration may set off ethnic identity formation because individuals living in an inborn environment usually take the issue of ethnicity for granted (Verkuyten, Drabbles, & van den Nieuwenhuijzen, 1999), especially if they belong to the majority group of the society (Cross, 1991; Phinney, 2003). Multicultural communities encourage ethnic identification, for the contact with different ethnic cultures helps individuals realize ethnicity issues and begin identifying themselves with their ethnic group (Berry, 2004). Thus, border communities, such as southwestern cities in the United States, provide ideal settings to examine ethnic identification arising from both immigration and from the cross-cultural contact experienced by both immigrants and later generation Americans.

It is on these fronts that acculturation may intersect with the evolution of one’s ethnic identity (Phinney, 2003; Schwartz, Montgomery, & Briones, 2006). Bosma and Kunnen (2001) suggest that evolution of identity is likely to occur when individuals grow to recognize that the surrounding society’s beliefs, values, and norms are discordant with their own. Thus, to the extent that changes following immigration and challenges accompanying cross-cultural interactions in border communities confront one’s ethnically rooted worldviews, the acculturation experience resulting from immigration would provide impetus for individuals, including those of later generation, to initiate their search of ethnic identity.

One’s search for ethnic identity may be initiated upon immigration also because of the label ascribed by the receiving culture (Hecht et al., 2005; Liebkind, 2006). Immigrants, including those of later generations, are often described in terms of their ethnic group membership, rather than individual attributes and unique personalities. This ethnicity-based ascription and stereotyping give a rise to one’s realization of the ethnic group to which he or she belongs but perhaps has not been aware of previously (Hecht et al., 2005; Tajfel & Turner, 1986). This dynamic-interactive perspective suggests that the relationship with and orientation toward the host culture are essential to immigrants’ ethnic identity development (Berry, 1997; Berry et al., 2006; Bourhis, Moïse, Perreault, & Sénécal, 1997). It is to this issue of intercultural orientation that the current review now turns.

Bicultural/Monocultural Orientation: Adaptation Style of Mexican-Heritage Youth

Upon encounter with a different culture and through the journey of acculturation, individuals deploy a variety of dispositional strategies to accommodate the potential tension between the new culture and their culture of origin. Note that such a tension can and does occur to immigrants of second or later generations because they may find contradiction between the beliefs and values of the host culture they experience outside the family and those of the culture of their heritage described, shown, and communicated by their parents. Berry and colleagues argue that acculturating individuals often identify with both the local culture and their heritage culture (Berry, 1997, 2004; Berry, Poortinga, Segall, & Dasen, 2002). In other words, individuals’ orientation toward the host (or majority) culture vis-à-vis their heritage culture varies along two intersecting axes. One axis concerns the endorsement and adoption of the new culture, and the other concerns the maintenance of individuals’ culture of origin (Sam, 2006).

According to this framework, individuals undergoing the acculturation process deploy one of four orientations (Berry, 2006; Kim, 2005; LaFromboise, Coleman, & Gerton, 1993): integration (individuals hold positive orientations toward both the host/majority culture and their culture of origin), assimilation (individuals weigh adaptation to the new/majority culture over maintaining their original culture and are willing to adopt the beliefs, values, and norms of the society of settlement), separation (individuals attach importance to holding their heritage culture and minimize adoption of the new/majority culture), and marginalization (there is low interest in both maintaining one’s heritage culture and adapting to the host/majority culture).

Whereas individuals vary substantially in their way of cultural orientation (see Seaton, Scottham, & Sellers, 2006), two competing patterns of acculturation have been proposed. The first pattern points to the prominence of the integration orientation (Mishra, Sinha, & Berry, 1996; Nguyen, Messé, & Stollak, 1999). Related research views integration as the rule, not an exception, in the course of acculturation (for an exception, see Ataca & Berry, 2002). Others, however, argue that the movement toward assimilation predominates (Gordon, 1964; Kim, 2005, 2006; see Sam, 2006, for a discussion of these two schools).

In regards to the case of the current study’s target population, both of those patterns have been documented. That is, past research indicates that most Mexican-heritage youth in the United States tend to exhibit either a bicultural or a monocultural orientation. The former directly corresponds to the notion of integration whereas the latter specifically represents assimilation; marginalization seems particularly rare among nonclinical, community-based populations of Mexican immigrants and Mexican Americans in the United States (French et al., 2006; Phinney & Devich-Navarro, 1997). These bicultural/monocultural orientations affect individuals’ attitudes and behaviors in their day-to-day interactions with their host culture counterparts and members of their ethnic group (Berry, 2006). As a behavioral manifestation of this cultural orientation, the current study highlights Mexican-heritage youths’ language use. Because language provides a vital tool for everyday communication wherein individuals manage their relationships with others and express identity, scrutiny into the way in which Mexican-heritage youth utilize language may shed further light on their cultural orientation and ethnic identity.

Ethnic Identity, Acculturation, and Language

Research suggests that immigrants’ sociolinguistic orientation (i.e., differentiation of language use according to the given social context) signifies their identity management and cultural adaptation style. Berry et al.’s (2006) research on immigrant youth in 13 countries suggests that language knowledge and use are closely related to one’s ethnic identity and cultural orientation. Other research has demonstrated similar relationships for second- and later generation Mexican Americans (see, e.g., Norris, Ford, & Bova, 1996).

Two theories provide explanations for the conceptual linkage between one’s language use and cultural adaptation, as well as their ethnic identity. Ethnolinguistic identity theory (ELIT) suggests that language represents a core aspect of one’s social group identity if not worldview (Giles & Johnson, 1987; Giles, Williams, Mackie, & Rosselli, 1995). Consistent with this proposition, one’s perceptions of the surrounding culture and their heritage culture are found to correlate with language preference, knowledge, and actual use (Giles et al., 1995; Phinney et al., 2001). One study revealed that, whereas Mexican Americans generally view English and Anglo/European American as more vital than Spanish and Mexican American, those who strongly identify with Mexican culture perceive the vitality of Spanish to be higher than their counterparts with weaker ethnic identification (Gao, Schmidt, & Gudykunst, 1994). Evans (1996) has shown that Hispanic immigrant parents who believe in strong vitality of the Mexican ethnic culture tend to transmit their cultural beliefs and Spanish to their children, suggesting a structural tie between Mexican-heritage youths’ ethnic identity and their language knowledge.

Additionally, the theory of subjective ethnolinguistic vitality (SEV; Bourhis & Sachdev, 1984; Giles, Bourhis, & Taylor, 1977) points to the impact of societal factors, as well as the perceived viability of the language, on minority members’ language preference. Dailey, Giles, and Jansma’s (2005) recent study, for example, has shown that the given community’s linguistic landscape is associated with Anglo and Hispanic adolescent’s perception of language such that those living in Spanish-oriented communities in terms of road signs, available media, and so forth tend to evaluate the Spanish language favorably. Similarly, Gibbons and Ramirez (2004) found that, among Hispanic teenagers living in Sydney, the determination to resist the social pressure to assimilate into the English-dominant local community is associated with their Spanish language maintenance and ethnic pride. These findings based on ELIT and SEV suggest that one’s language behavior is intertwined with their cultural orientation, ethnic identity, and local environment in a complex manner, suggesting the need to examine them simultaneously.

Heterogeneity and Complexity in the Ethnic Identity Development Process

Together, research reviewed in the preceding sections provides some insights into the complex and multifaceted processes underlying the development of ethnic identity and cultural/linguistic orientation (Berry, 1997; French et al., 2006). Naturally, possible patterns of identity development should vary considerably because not all individuals share the same background or undergo the same experience in the same social environment (Seaton et al., 2006). Furthermore, this variability extends along the chronological dimension. Based on the theorizing offered by Cross (1991) and Phinney (1990, 2003), French et al. (2006) suggest that ethnic minority members oscillate between various stages of confidence and commitment to their ethnicity.

To clarify these conjectures and come to grips with the major patterns of acculturation experience, research should encapsulate the richness of the constructs in a holistic manner by modeling related factors together and trace the developmental trajectory of this theoretical amalgam longitudinally. Furthermore, given the above notion of heterogeneity inherent in the acculturation process (Berry, 2004; French et al., 2006), this research also should explore the variability in individual development both within and across time. The current study undertakes these challenges by exploring the development of Mexican-heritage youths’ ethnic identity and cultural/linguistic orientations through latent profile and latent transition analyses.

Research Questions and Hypothesis

First, this study explores the theoretical linkage among acculturation-related constructs. As per Berry’s (2004) and French et al.’s (2006) contention, it is expected that acculturating individuals such as Mexican-heritage youth would show several distinct patterns, particularly those signifying integration and assimilation, in terms of ethnic identity and cultural/linguistic orientation. Our analysis aims to profile those unique patterns. Stated in the form of a hypothesis,

Hypothesis 1: There is a mixture of discrete profiles of Mexican-heritage youth, each characterized by qualitatively distinct patterns of ethnic identity exploration and affirmation, bicultural versus monocultural orientation, and language preference.

The literature provides less direction on how these profiles evolve over time. Research suggests that acculturating individuals continually develop, explore, and transform their ethnic identity and cultural/linguistic orientations. However, the trend characterizing such changes still remains to be investigated. To address this point, this study examines the following research question based on the longitudinal data from Mexican-heritage youth in the United States:

Research Question 1: What are the major trends in the development of Mexican-heritage youths’ ethnic identity and cultural/linguistic orientation profile?

Finally, this study investigates how these profiles are related to youths’ demographic background to clarify profile endorsement patterns. Research suggests that ethnic identity and cultural/linguistic orientations differ, for example, by gender (Kulis, Marsiglia, & Hurdle, 2003) and generation status (Portes & Rumbaut, 2001). The research question below gauges such sociological dimensions of ethnic identity and cultural/linguistic orientation:

Research Question 2: How is Mexican-heritage youths’ demographic background associated with their profile of ethnic identity and cultural/linguistic orientations?

Method

Participants

The data of this study were collected for a National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA)–funded research program from 1,600 self-identified Mexican, Mexican American, and Chicana/o students attending 29 public schools in Phoenix, Arizona, across four waves; all surveys subsequent to the baseline assessment were administered in about 6-month intervals. The mean age at the baseline was 10.4 years (SD = 0.60). Gender composition was well balanced (748 boys and 778 girls; 74 students did not report their gender). The vast majority of respondents (88%) reported that they received either free or reduced-cost lunch at school, indicating low socioeconomic status.

The sample included youth born in Mexico (27%), second-generation Americans (i.e., children of immigrants; 68%), and third- or higher generation Americans (5%). In line with this genealogy, 854 participants had lived in the United States for the entirety of their lives at the point of baseline, 115 had lived in the United States for more than 10 years, 247 for 6 to 10 years, 225 for 1 to 5 years, and 69 for less than 1 year. More than half had the experience of visiting family or friends living abroad. Finally, 455 participants reported that their best friend was Mexican, 758 Mexican American or Chicana/o, 77 White, and 163 “Other” (e.g., African American, Asian, etc.).

Data Collection Procedure

Parental active consent was obtained before the baseline data collection, and students also provided their informed assent for participation at each wave. Students had 45 minutes to complete the questionnaires in their classrooms and received small incentives for participation (e.g., pencils, small toys). Of 1,600 initial participants, 1,417 (89%) participated at the second wave, 1,155 (72%) in Wave 3, and 721 (45%) at Wave 4.

All survey materials were prepared in both English and Spanish (10% of the students took the baseline survey in Spanish, 8% at Wave 2, 3% at Wave 3, and 2% at Wave 4). The questionnaire was developed in English first and then translated into Spanish by the project personnel. The translation validity was verified using a back-translation method (Brislin, 1970).

Measures

Prior to the analyses, all scales were recoded, where necessary, so that higher scores would indicate higher levels of the respective construct. For all scales used, only a selected set of items were used to help participants maintain concentration and to alleviate fatigue.

Ethnic identity

Using six items selected from Phinney’s (1992) Multigroup Ethnic Identification Measure (MEIM), two dimensions of the ethnic identity were measured on a 4-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree). Three MEIM items (e.g., “I have tried to learn more about my own ethnic group, such as its history and customs”) were selected from the Exploration dimension and three (e.g., “I feel like I really belong to my own ethnic group”) were selected from the Affirmation/Belonging dimension.

Of note here is that one item was specified differently from Phinney’s (1992) original measure. Although the item asking one’s involvement in the group customs (“I am involved in the customs of my own ethnic group, such as food, music, or celebrations”) was originally specified as an indicator of the Exploration factor, preliminary analysis revealed that this item correlated more strongly with the Affirmation/Belonging items than the other Exploration items throughout all waves. Thus, this item was respecified as an indicator of Affirmation/Belonging, instead of Exploration. Cronbach’s alpha varied from .65 (Wave 1) to .83 (Wave 4) for Exploration, and from .81 (Wave 1) to .91 (Wave 4) for Affirmation/Belonging.

Cultural orientation

Participants’ cultural orientations were assessed by two questions asking their attitudes toward cultural ways (“I like the way things are done in the US” and “I like the way things are done in my culture”; see Unger et al., 2002) on a 4-point Likert-type scale. Correlation between these two items ranged from .22 (Wave 3) to .37 (Wave 2). Preliminary analysis revealed that, consistent with previous findings (e.g., French et al., 2006; Phinney & Devich-Navarro, 1997), the vast majority indicated strong liking for both cultural ways, yielding a sparse array of other response patterns. To create a meaningful classification for the main analysis, the cultural orientation items were combined into a dichotomous variable indicating bicultural status. Specifically, participants who answered either “agree” or “strongly agree” to both questions were classified as bicultural and the others as nonbicultural. Hence, the bicultural category referred to respondents oriented toward integration, while the nonbicultural category lumped together the respondents oriented toward assimilation, separation, and marginalization.

Linguistic orientation

Linguistic orientation was measured using three items scored on a 5-point semantic-differential scale (1 = Spanish only; 3 = both English and Spanish; 5 = English only; as = .66 to .73) as adopted from Marin, Sabogal, Marin, Otero-Sabogal, and Perez-Stable (1987). The items asked participants about the language they use with family members, friends, and in their media interactions (television, radio, and music).

Analysis Plan: Latent Profile and Transition Analyses

Latent profile analysis

To identify the underlying mixture of profiles of ethnic identity and cultural/linguistic orientation, latent profile analysis (LPA) was performed using Mplus 4.2. LPA models an unobserved (latent) categorical factor that accounts for the heterogeneity of manifest variables and estimates the fit of this hypothetical model to the given data (Vermunt & Magidson, 2002). Those latent categories illuminate the hidden structure in which a variety of variables operate vis-à-vis one another. If, for example, all variables included in an analysis have clearly bimodal distributions and all individuals score either high or low in all of them, a two-profile model (i.e., a high-score profile and a low-score profile) would be detected. This of course is an unrealistically simple scenario, and actual cases, such as the one reported in this article, involve more complex response patterns over a number of categorical and/or continuous manifest variables. LPA enables the classification of individuals into unique profiles based on this multivariate heterogeneity. LPA is therefore particularly suitable to uncover the underlying structure of diverse constructs, which nonetheless combine in a theoretically meaningful manner.

One advantage of LPA over traditional clustering techniques is that it hypothesizes an a priori specified model and evaluates its fit based on a number of statistical goodness-of-fit indices. This way, LPA classifies individuals less subjectively than, say, an eyeball inspection of a tree-dengrogram (see DiStefano & Kamphaus, 2006, for a more comprehensive comparison of LPA with cluster analysis). More specifically, the optimal number of latent profiles is determined by systematically comparing multiple models with different numbers of profiles and selecting the one that demonstrates the most adequate fit in light of a select set of indices; in the current study, we utilize the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), the Akaike information criterion (AIC), entropy, and the conceptual interpretability as the model evaluation criteria.

BIC and AIC are relative fit indices such that the lower BIC or AIC, the better a model. Note that, as relative fit indices, there is no absolute “cutoff” value for BIC and AIC. AIC is known to be “liberal” in that more complex models are favored by AIC, whereas BIC prefers simpler models; for the sake of model parsimony, we draw primarily on BIC in the current study, while noting if there is any appreciable discordance indicated by AIC. A third index is entropy; values closer to 1.00 are better and a model with an entropy greater than .80 is considered acceptable. Finally, the interpretability of the results provides an important criterion. All extracted profiles must make theoretical sense and be clearly distinguishable from one another.

Latent transition analysis (LTA)

Based on the profiling extracted from the LPA, LTA would be performed to examine the developmental process of Mexican and Mexican American adolescents’ ethnic identity and cultural/linguistic orientations in their course of acculturation. LTA estimates the underlying stage-sequential patterns in longitudinal data using multiple observed indicators (see Lanza, Flaherty, & Collins, 2003, for a review). By using LTA, not only the prevalence of particular latent profiles at each wave but also the patterns of change in the profile endorsement, or transition, across waves were estimated.

Results

LPA: Modeling the Complexity and Heterogeneity

First, LPAs were performed to determine the number of profiles needed to reconstruct the number and variety of Mexican-heritage youth’s ethnic identity and cultural/linguistic orientations. Separate LPAs were run at each wave because whether the overall “big picture” would remain the same or change (e.g., a new profile emerging at later waves) was not clear. If the profile solutions were found to vary across waves, such speciation and/or extinction of profiles would have to be incorporated into the analysis of the longitudinal trend (i.e., LTA).

This series of LPAs pointed to a four-profile model as the optimal representation of the current study’s data across all four waves. To illustrate, increasing the number of profiles consistently resulted in sizable reduction in both BIC and AIC up to the fourth profile (ΔBIC3→4-profile ranged from −47.22 to −142.11, and ΔAIC3→4-profile ranged from −70.05 to −168.36). In addition, all four-profile models demonstrated adequate levels of entropy (.84–.88). Modeling a fifth profile did not improve the fit, except for Wave 3 where the five-profile model appeared to fit better than the four-profile counterpart in terms of BIC and AIC (but the entropy difference was negligible). However, conceptual inspection revealed that the fifth profile marginally differed from the fourth one, adding little to the heuristic value of the model and making it difficult to interpret each profile. In contrast, all profiles extracted in the four-profile model were clearly interpretable as discrete patterns of ethnic identity and cultural/linguistic orientations. Hence, the decision was made to maintain the four-profile model across all four waves. Table 1 provides a summary of thus identified four profiles’ parameter estimates and prevalence across time.

Table 1.

Parameter Estimates of the Four Latent Profiles and the Estimated Prevalence Across Waves

| Latent profile |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Strong Ethnic Identification |

Moderate Ethnic Identification |

Strong Affirmation/ Weak Exploration |

Monocultural- Assimilation |

| Ethnic identity—M (SD) | ||||

| Exploration | 3.38a (0.51) | 2.72b (0.57) | 1.60c (0.54) | 1.56c (0.66) |

| Affirmation/Belonging | 3.79a (0.21) | 2.95b (0.27) | 3.81a (0.21) | 1.45c (0.43) |

| Percentage bicultural | .847a | .778b | .962a | .356c |

| Language use—M (SD) | 3.33a (0.87) | 3.54b (0.85) | 3.72b (1.09) | 3.58b (0.91) |

| Prevalence of profile—n (%) | ||||

| Wave 1 | 748 (46.8) | 733 (45.8) | 53 (3.3) | 65 (4.1) |

| Wave 2 | 854 (53.4) | 474 (29.6) | 113 (7.1) | 158 (9.9) |

| Wave 3 | 857 (53.6) | 567 (35.5) | 90 (5.6) | 85 (5.3) |

| Wave 4 | 868 (54.3) | 562 (35.1) | 83 (5.2) | 86 (5.4) |

Percentage bicultural = the likelihood of having a bicultural orientation. The parameter estimates and the estimated prevalence are computed by the latent transition analysis using the robust maximum likelihood as the estimator. Parameter estimates with the same subscripted alphabet letter are statistically indistinguishable at the .05 alpha level (classic-Bonferroni-adjusted). The two ethnic identity dimensions were both measured on a 4-point Likert-type scale. Language use was measured on a 5-point semantic-differential scale (1 = strong Spanish orientation; 3 = both English and Spanish; 5 = strong English-orientation).

The first three profiles appeared indicative of various patterns of integration. The first profile, labeled as Strong Ethnic Identification (SEI), showed strong ethnic identity in terms of both Exploration and Affirmation/Belonging, coupled with a high likelihood of having a bicultural orientation and a relatively balanced use of both English and Spanish. The second profile exhibited moderate levels of Exploration and Affirmation/Belonging, a relatively high likelihood of having a bicultural orientation, and a tendency to use more English than Spanish. This profile was labeled as Moderate Ethnic Identification (MEI). The third latent profile had an interesting combination of weak Exploration with strong Affirmation/Belonging and a high likelihood of having a bicultural orientation. This profile was labeled as Strong Affirmation/Weak Exploration (SA/WE). Finally, the fourth profile had characteristics indicative of strong assimilation: weak ethnic identity, a low likelihood of having a bicultural orientation, and a tendency to use English more than Spanish. This profile was labeled as Monocultural-Assimilation (MA).

LTA: Scrutiny Into the Trend of Ethnic Identity and Cultural/Linguistic Orientations

Based on the four-profile model identified above, an LTA with the measurement invariance restriction (Lanza et al., 2003) was performed using Mplus 4.2. All indicators were restricted to operate in the same way across all four waves so that the same profile would represent the same characteristics. Validity of this restriction was tested by comparing two models—one with the invariance restriction and the other without. The BIC suggested that the restricted LTA model (BICrestricted = 33,917.63) fit the data better than the unrestricted model (BICunrestricted = 34,076.53).

LPA revealed complex, if systematic, patterns of the trend underlying Mexican-heritage youth’s ethnic identity and cultural/linguistic orientation profile development (see Table 2 for a summary of the latent transition probabilities). First, youth with the SEI or MEI profile were most likely to retain it across waves, and if they were to change their profile, the most likely transition was between these two profiles (i.e., the adoption of the MEI profile by SEI youth or vice versa). As for those with the SA/WE profile at earlier waves, the overall trend was still the same; the most likely pattern was the maintenance of the SA/WE profile. If they adopt a new profile, the first choice would be SEI, followed by MEI. Finally, youth starting off with the MA profile were found to be the least stable. Except for the Wave 1 to 2 transition, MA youth were more likely to adopt the MEI profile in subsequent waves than SEI, which appeared to be the modal choice for the adolescents with the other profiles.

Table 2.

Latent Transition Probability Matrix Across Waves

| Latent profile at an earlier wave | Latent profile at a subsequent wave | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| W1 → W2 | W2 | |||

| SEI | MEI | SA/WE | MA | |

| W1 | ||||

| SEI | .650 | .190 | .076 | .084 |

| MEI | .342 | .462 | .074 | .122 |

| SA/WE | .287 | .142 | .484 | .087 |

| MA | .355 | .328 | .095 | .222 |

| W3 |

||||

| W2 → W3 | SEI | MEI | SA/WE | MA |

| W2 | ||||

| SEI | .683 | .238 | .044 | .035 |

| MEI | .263 | .584 | .083 | .070 |

| SA/WE | .402 | .156 | .395 | .047 |

| MA | .259 | .418 | .034 | .289 |

| W4 |

||||

| W3 → W4 | SEI | MEI | SA/WE | MA |

| W3 | ||||

| SEI | .705 | .220 | .044 | .031 |

| MEI | .349 | .535 | .055 | .061 |

| SA/WE | .242 | .188 | .539 | .030 |

| MA | .209 | .387 | .000 | .404 |

Measurement invariance restriction was imposed across all four waves. Probabilities highlighted by boldface indicate the endorsement of the same profile at two consecutive waves. SEI = Strong Ethnic Identification; MEI = Moderate Ethnic Identification; SA/WE = Strong Affirmation/Weak Exploration; MA = Monocultural-Assimilation.

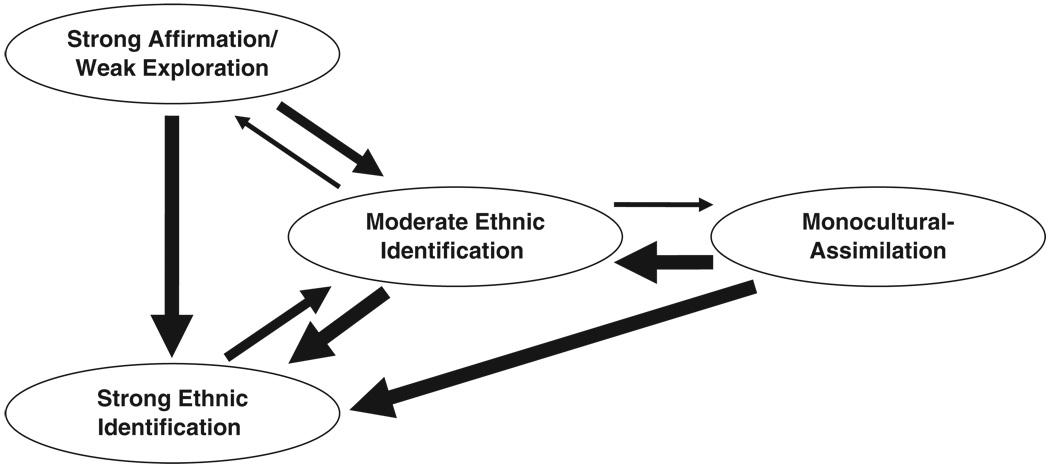

To further scrutinize these profile endorsement stases and transitions, the frequency of unique longitudinal patterns was examined. The most striking finding that emerged from this inspection was the strong tendency to maintain one’s profile. Almost 40% maintained either the SEI or MEI profile throughout the four waves. Another 20% or so exhibited “semistasis”: maintenance of the same profile across three consecutive waves. In short, the major trend among these Mexican-heritage youth seemed to be the maintenance or initiation of the exploration of their ethnic background (see Figure 1 for a visual summary).

Figure 1.

Structure of stasis/transition patterns of ethnic identity and cultural/linguistic orientation profile endorsement by Mexican-heritage youth

Arrows indicate the direction of major transition and their width indicates the average likelihood of the respective transition according to the following schema: no arrow = 0–5%, small arrows = 6–15%, medium arrows = 16–25%, and large arrows = 26% or greater mean transition likelihood.

Linking the Ethnic Identity and Cultural/Linguistic Orientation Profile With Demographics

Finally, a series of multinominal logistic regression analyses were performed to gauge the demographic characteristics of these ethnic identity and cultural/linguistic orientation profiles, using the Wave 1 latent profile endorsement as the criterion. The MA profile was set as the baseline category of the regression model. The results revealed that several demographic factors were significantly associated with the adolescents’ profile endorsement (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Multinominal Logistic Regression Table With the Ethnic Identity and Cultural/Linguistic Orientation Profile as the Criterion

| Latent profile |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEI |

MEI |

SA/WE |

|||||||

| Factor | B | SE | OR | B | SE | OR | B | SE | OR |

| Gendera | −0.52* | 0.27 | 0.60 | −0.41 | 0.27 | 0.13 | −0.99*** | 0.39 | 0.37 |

| Lunch status: Free lunch | −0.74* | 0.44 | 2.10 | −0.33 | 0.43 | 1.39 | −0.04 | 0.62 | 1.04 |

| Lunch status: Reduced-cost lunch | −1.54** | 0.62 | 4.67 | −1.05* | 0.61 | 2.85 | −1.13 | 0.80 | 3.08 |

| Youth own birthplaceb | −0.24 | 0.30 | 0.79 | −0.07 | 0.30 | 1.07 | −0.21 | 0.44 | 1.23 |

| Father’s birthplaceb | −0.18 | 0.38 | 1.19 | −0.41 | 0.38 | 1.51 | −1.41*** | 0.47 | 4.11 |

| Mother’s birthplaceb | −0.21 | 0.32 | 0.81 | −0.05 | 0.32 | 0.95 | −0.88** | 0.42 | 2.40 |

| Time spent in the United States | |||||||||

| Less than a year | −0.39 | 0.51 | 0.68 | −0.96* | 0.53 | 0.38 | −0.48 | 0.77 | 0.62 |

| Between 1 and 5 years | −0.27 | 0.41 | 1.31 | −0.03 | 0.41 | 0.97 | −0.26 | 0.59 | 0.77 |

| Between 6 and 10 years | −0.06 | 0.36 | 0.94 | −0.14 | 0.36 | 0.87 | −0.76 | 0.59 | 0.47 |

| More than 10 years | −0.47 | 0.44 | 0.63 | −0.39 | 0.44 | 0.68 | −1.22 | 0.84 | 0.29 |

| Visiting family/friends outside the United States | |||||||||

| In the past year | −0.00 | 0.31 | 1.00 | −0.21 | 0.31 | 0.81 | −0.98** | 0.46 | 0.38 |

| In the past 3 years | −1.93* | 1.00 | 6.92 | −1.88* | 1.00 | 6.53 | −0.90 | 1.20 | 2.46 |

| More than 3 years ago | −0.16 | 0.37 | 0.85 | −0.17 | 0.36 | 0.84 | −0.56 | 0.52 | 0.57 |

| Best friend’s ethnicity/nationality | |||||||||

| Mexican | −0.43 | 0.58 | 1.54 | −0.04 | 0.58 | 1.04 | −0.23 | 0.83 | 1.26 |

| Mexican American or Chicano/a | −0.42 | 0.56 | 1.51 | −0.13 | 0.58 | 1.14 | −0.01 | 0.81 | 0.99 |

| “Other” | −0.52 | 0.68 | 1.69 | −0.26 | 0.67 | 1.30 | −0.41 | 1.00 | 0.67 |

SEI = Strong Ethnic Identification; MEI = Moderate Ethnic Identification; SA/WE = Strong Affirmation/Weak Exploration. The Monocultural-Assimilation profile was set as the baseline category for the criterion. The baseline category for the time spent in the United States was “all my life.” The baseline category for the experience of visiting family or friends living outside the United States was “never.” The baseline category for the best friend’s ethnicity/nationality was “White.”

0 = girl; 1 = boy.

0 = Mexico; 1 = the United States.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Boys showed a weaker tendency than girls to endorse the SEI or SA/WE profile over MA. There were no significant gender differences in terms of MEI profile. Those with lower SES (indicated by lunch status) tended to endorse SEI. Interestingly, youth’s own birthplace was not significantly associated with his or her profile endorsement. On the other hand, parents’ birthplace predicted their children’s profile such that youth with U.S.-born father or mother tended towards the SA/WE profile. An ad hoc analysis on the father’s and mother’s birthplace interaction effect revealed that this tendency was present only for the youth both of whose parents had been born in the United States (B = 1.45, p < .01, OR = 4.27). Adolescents who had the experience of visiting family or friends outside the United States within the past 3 years were about 6.5 to 7 times more likely to have the SEI or MEI profile over MA. Intriguingly, visitation within the past year showed no such effects; in fact, it was associated with a reduced likelihood to endorse the SA/WE profile, indicating some delayed effects. The length of the time spent in the United States and the best friend’s ethnicity/nationality were not associated with the youth’s profile endorsement.

Discussion

The current study explored the underlying structure of Mexican-heritage youths’ ethnic identity and cultural/linguistic orientation profiles as well as their sociodemographic correlates at the beginning of adolescence. Latent profile and transition analyses revealed that the majority of the adolescents have strong to moderate ethnic identification, along with biculturalism and English-Spanish bilingualism; moreover, they increasingly engage in exploration of their ethnic root. Furthermore, multinominal logistic regression analyses revealed that these endorsement patterns are associated with demographic background factors, including gender, SES, parents’ birthplace, and whether they had visited family or friends outside of the United States. These findings and their implications are discussed in turn below in regard to previous research on acculturation.

Ethnic Identity and Cultural/Linguistic Orientation Profiles: Acculturation as Integration

This study’s sample represented the first- or second-generation Mexican Americans, and all lived in a border community characterized by a large immigrant population and frequent movement between the United States and Mexico. As such, they are likely to have been and/or are presently undergoing the course of acculturation (Berry et al., 2006; Phinney et al., 2001). Our study has revealed that those acculturation experiences entail complex and yet systematic patterns of ethnic identification, cultural orientation, and language use.

Most of the young adolescents endorsed profiles that included biculturalism as a major component. This buttresses previous findings that suggest that the modal acculturation orientation is integration (Berry, 2006), rather than a unidirectional move toward assimilation (Gordon, 1964; Kim, 2005, 2006). Furthermore, it indicates that biculturalism may be considered vital for successful acculturation, at least in border communities where cross-cultural contact constitutes a routine of one’s everyday life (Berry, 1997, 2006; Gibson, 2001). If so, then, youth endorsing the nonbicultural (i.e., MA) profile might represent an at-risk group. In fact, research suggests that absence of commitment and belongingness to one’s ethnic group during adolescence marks a significant risk factor in terms of substance use (Marsiglia, Kulis, Hecht, & Sills, 2004) and other risk behaviors (Blum et al., 2000).

Correspondence found between linguistic orientation and ethnic identification profiles seems to add support for this working hypothesis of the “fitness” of biculturalism. It is argued to be no coincidence that the SEI profile, which is found to be the most prevalent and stable among the four profiles identified in this study, exhibited the most balanced bilingual orientation. Granted, the difference between SEI and the other profiles in language use is quite small (Table 1), and thus, this finding needs to be cautiously interpreted. Nonetheless, it is not only consistent with the ethnolinguistic identity theory’s proposition that ethnic identity and cultural orientation are related to one’s language use (Giles & Johnson, 1987; Giles et al., 1995) but also points to integration as the prominent acculturation strategy taken by the Mexican-heritage youth living in border communities (Berry, 2006; French et al., 2006). Moreover, from the theory of subjective ethnolinguistic vitality perspective (Bourhis & Sachdev, 1984), the fact that the other profiles with weaker ethnic identification tended toward more English-oriented language use indicates that deployment of two languages in a predominantly English-speaking environment (i.e., the United States) requires robust commitment to one’s ethnic group to counteract the social pressure to assimilate minority group members (Dailey et al., 2005).

Stases and Transitions in Ethnic Identity and Cultural/Linguistic Orientation Development

Building upon the profile typology established via LPA, we explored the longitudinal trend of Mexican-heritage youths’ ethnic identity and cultural/linguistic orientation. Interestingly, the prevailing pattern has turned out to be stasis. The majority maintained one profile throughout the 18 months covered in this study. Furthermore, when change occurs, there is a certainly discernable trend toward the increasing prevalence of the SEI profile (Table 2). Those changes are, however, not necessarily linear or unidirectional (see Figure 1); rather, individuals oscillate between profiles and, at times, undertake a major changeover such as the transition from MA to SEI.

These findings inspire a number of theoretical thoughts. First, they contradict some of the previous studies and theories of cultural adaptation that contend the desire to become like members of the dominant culture acts as the driving force of acculturation (Gordon, 1964; Kim, 2005, 2006). Quite the contrary, the major trend found in this study is the one toward the state in which individuals accommodate both the culture of settlement and the culture of origin and in which they increasingly explore their ethnic heritage. The MA profile did emerge, but only for 5% to 10% of the sample across four waves, and the sample as a whole tended to move away from endorsing that profile while few moved toward endorsing it.

Second, inspection of the profile transitions illuminates the structure of Mexican-heritage youths’ ethnic identity and cultural/linguistic orientation development. Most notably, the MEI profile seems to provide a “hub,” or center of major transitions. Particularly, youth with MEI profile are the ones on the boundary between biculturalism and monoculturalism, as demonstrated by the finding that transition to the MA profile occurs mainly among them. Hence, further scrutiny into the dynamics around MEI profile may reveal the mechanism that distinguishes bicultural individuals from their monocultural counterparts.

In addition, the combination of strong Affirmation/Belonging and weak Exploration found for one of the profiles (i.e., SA/WE) provides support for the notion of differential development of the two ethnic identity dimensions (French et al., 2006; Phinney, 2003). Perhaps SA/WE profile acts as a “way station” between the MEI and the SEI profiles. As suggested by French et al. (2006), the Exploration dimension of ethnic identity may require stronger commitment and thus take more time to develop. The MEI → SA/WE → SEI route might represent this twofold process in which psychological aspects of ethnic identity and biculturalism develop first (MEI → SA/WE), followed by behavioral development including increased bilingualism (SA/WE → SEI).

Finally in regards to the overall trend of Mexican-heritage youths’ ethnic identity and cultural/linguistic orientation development, the widespread stasis of biculturalism noted above deserves attention. One obvious explanation for the profile stability is the shortage of time. That is, the current research covered a relatively short period, from the beginning of fifth grade to the beginning of seventh grade. As youth move towards later adolescence and into adulthood, they might experience greater fluctuations in their ethnic identification and cultural/linguistic orientations. Theoretically, however, individuals typically explore and experiment with their ethnic heritage in adolescence, consolidating their commitment to their identity roots (Erikson, 1968; Phinney, 1990). Nonetheless, future research should examine the process of ethnic identity development along with its correspondence with one’s cultural/linguistic orientation in a more extended span.

An alternative account is that biculturalism is indeed an adaptive orientation for Mexican-heritage youth to endorse in their course of acculturation (Berry, 1997; Gibson, 2001). As first- and second-generation Mexican Americans seek to adapt to the local environment of border communities, they would need to exercise cultural code switching on a daily, if not more frequent, basis. For example, parents of the current study’s sample would most probably speak Spanish as their first—possibly only—language and sport Mexican culture, whereas once out of home, those young adolescents need to navigate through the surrounding U.S. society. In such a culturally ambivalent circumstance, deploying a disposition to accommodate two cultures would help mitigate the ambient stress of acculturation (Berry, 2006; Berry et al., 2006).

Sociodemographic Characteristics Related to Ethnic Identity and Cultural/Linguistic Profiles

Mexican-heritage youths’ ethnic identity and cultural/linguistic profile is related to their sociodemographic characteristics and interpersonal relationships. Boys are found to be less likely to endorse bicultural profiles than girls in general (Table 3). This gender difference may be explained in terms of the Mexican culture that favors traditional sex roles and encourages females to stay at home (Valentine & Mosley, 2000); such values would increase the daughter-parent interaction, promoting the transmission of ethnic heritage and cultural orientation preferably for girls. Also regarding demographic factors, receiving reduced-cost lunch increased the youth’s likelihood of SEI or MEI profile endorsement, though the free-lunch status did not show such associations. Berry (2006) and Phinney (2003) both point out that individuals with higher SES tend to show an assimilation orientation because they are likely to be closer to the mainstream part of the society than their low-SES counterparts.

Finally, it seems noteworthy that the experience of visiting one’s family or friends living outside the United States within the past three years was associated with the SEI or MEI profile endorsement (Table 3). Martin and Nakayama (2004) argue that encounters with those who exhibit strong ethnic identification can “result in a concern to clarify the personal implications of their heritage” (p. 173). Thus, it is argued that contact with the individuals living outside the United States might have triggered Mexican-heritage youths’ motivations to explore their ethnic roots. To test this view, future studies should explore the interpersonal dimension of ethnic identity development and acculturation process (Bourhis et al., 1997).

Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations and future directions should be noted. First, measures used in this study are abbreviated versions of the original scales. This was inevitable to help the early adolescent participants maintain concentration; nonetheless, future research should use more comprehensive measures to increase the reliability of assessment. Second, the particular setting of this study provided the youth with consistent contact with their heritage culture; Mexican-heritage youth acculturating in communities that do not provide this contact may face very different experiences. Given recent findings demonstrating the significant impact of community characteristics (Birman, Trickett, & Buchanan, 2005; Huang, Nguyen, & Lin, 2006), it is expected that factors such as the given community’s racial diversity or the population density of one’s ethnic group would affect the dynamics of ethnic identity and cultural/linguistic orientation.

While addressing these limitations, future research should explore outcomes related to the profiles found in this study. In light of the associations among ethnic identity, acculturation, and various risks (Blum et al., 2000; Marsiglia et al., 2004), such pursuits would provide insights for practitioners to design effective programs to enhance acculturating youth’s well-being. Finally, whether this study’s framework combining ethnic identity and cultural/linguistic orientations can be generalized to other ethnic groups should be determined for further theorizing of acculturation.

Acknowledgments

This publication was supported by Grant Number (RO1 DA005629) from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to The Pennsylvania State University (Michael Hecht, Principal Investigator). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Biographies

Masaki Matsunaga received his PhD in communication arts and sciences from the Pennsylvania State University and now works as an assistant professor at Waseda University. His main research area is interpersonal communication and identity management. His recent work focuses on the coping processes of bullied individuals and their surroundings.

Michael L. Hecht, PhD, is a distinguished professor of communication arts and sciences, and crime, law, and justice at the Pennsylvania State University. He is interested in understanding how people can be successful and effective communicators, developing theory and practice in the areas of interpersonal and interethnic relationships, identity, and adolescent drug resistance.

Elvira Elek, PhD, is a public health analyst in RTI’s Psychology of Health Behavior group. For the 8 years prior to coming to RTI in 2007, she worked as a data analyst and then project director and coinvestigator of the Drug Resistance Strategies Project (DRS), a National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA)–funded evaluation of culturally targeted and school-based substance use prevention intervention. Since joining RTI, she has led, assisted, and/or reviewed the evaluations and examinations of statewide antitobacco media campaigns, alcohol prevention in pregnancy, and adolescent pregnancy prevention interventions.

Khadidiatou Ndiaye, PhD (2008, Pennsylvania State University), is an assistant professor in the Department of Communication at Michigan State University. Her research centers on issues of culture, health, and international communication. She explores how culture impacts the fundamental understanding of health as well as individual and communities’ behaviors.

Footnotes

Reprints and permission: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Declaration of Conflicting Interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- Ataca B, Berry JW. Sociocultural, psychological and marital adaptation of Turkish immigrant couples in Canada. International Journal of Psychology. 2002;37:13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117:497–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Applied Psychology. 1997;46:5–34. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Fundamental psychological processes in intercultural relations. In: Landis D, Bennett J, editors. Handbook of intercultural research. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2004. pp. 166–184. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Contexts of acculturation. In: Sam DL, Berry JW, editors. The Cambridge handbook of acculturation psychology. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2006. pp. 27–42. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW, Phinney JS, Sam DL, Vedder P. Immigrant youth in cultural transition: Acculturation, identity and adaptation across national contexts. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW, Poortinga YH, Segall MH, Dasen PR. Cross-cultural psychology: Research and application. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Birman D, Trickett E, Buchanan RM. A tale of two cities: Replication of a study on the acculturation and adaptation of immigrant adolescents from the former Soviet Union in a different community context. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2005;35:83–101. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-1891-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum RW, Beuhring T, Shew ML, Bearinger LH, Sieving RE, Resnick MD. The effects of race/ethnicity, income, and family structure on adolescent risk behaviors. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:1879–1884. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.12.1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosma HA, Kunnen ES. Determinants and mechanisms in ego identity development: A review and synthesis. Developmental Review. 2001;21:39–66. [Google Scholar]

- Bourhis RY, Moïse LC, Perreault S, Sénécal S. Towards an interactive acculturation model: A social psychological approach. International Journal of Psychology. 1997;32:369–386. [Google Scholar]

- Bourhis R, Sachdev I. Vitality perceptions and language attitudes: Some Canadian data. Journal of Language and Social Psychology. 1984;3:97–126. [Google Scholar]

- Brislin RW. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1970;1:185–216. [Google Scholar]

- Cross WE., Jr . Shades of Black: Diversity in African-American identity. Philadelphia: Temple University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Dailey RM, Giles H, Jansma LL. Language attitudes in an Anglo-Hispanic context: The role of the linguistic landscape. Language & Communication. 2005;25:27–38. [Google Scholar]

- DiStefano C, Kamphaus RW. Investigating subtypes of child development: A comparison of cluster analysis and latent class cluster analysis in typology creation. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2006;66:778–794. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson E. Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: Norton; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Evans C. Ethnolinguistic vitality, prejudice, and family language transmission. Bilingual Research Journal. 1996;20:177–207. [Google Scholar]

- French SE, Seidman E, Allen L, Aber JL. The development of ethnic identity during adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:1–10. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao G, Schmidt KL, Gudykunst WB. Strength of ethnic identity and perceptions of ethnolinguistic vitality among Mexican Americans. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1994;16:332–341. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons J, Ramirez E. Different beliefs: Beliefs and the maintenance of a minority language. Journal of Language and Social Psychology. 2004;23:99–117. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson MA. Immigrant adaptation and patterns of acculturation. Human Development. 2001;44:19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Giles H, Bourhis RY, Taylor DM. Towards a theory of language in ethnic group relations. In: Giles H, editor. Language, ethnicity, and intergroup relations. London: Academic Press; 1977. pp. 307–349. [Google Scholar]

- Giles H, Johnson P. Ethnolinguistic identity theory: A social psychological approach to language maintenance. International Journal of the Sociology of Language. 1987;68:69–99. [Google Scholar]

- Giles H, Williams A, Mackie DM, Rosselli F. Reactions to Angle- and Hispanic-American-accented speakers: Affect, identity, persuasion, and the English-only movement. Language & Communication. 1995;15:107–120. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon MM. Assimilation in American life: The role of race, religion and national origins. New York: Oxford University Press; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Hecht ML, Warren J, Jung E, Krieger J. The communication theory of identity: Development, theoretical perspective, and future directions. In: Gudykunst WB, editor. Theorizing about intercultural communication. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 2005. pp. 257–278. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez DJ. Children of immigrants: Health, adjustment and public assistance. In: Hernandez DJ, editor. Children of immigrants: Health, adjustment and public assistance. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1999. pp. 1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang LP, Nguyen HH, Lin Y. The ethnic identity, other-group attitudes, and psychosocial functioning of Asian American emerging adults from two contexts. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2006;21:542–568. [Google Scholar]

- Kagitcibasi C. Family and human development across cultures: A view from the other side. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kim YY. Adapting to a new culture: An integrative communication theory. In: Gudykunst WB, editor. Theorizing about intercultural communication. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2005. pp. 375–400. [Google Scholar]

- Kim YY. From ethnic to interethnic: The case for identity adaptation and transformation. Journal of Language and Social Psychology. 2006;25:283–300. [Google Scholar]

- Kulis S, Marsiglia FF, Hurdle D. Gender identity, ethnicity, acculturation, and drug use: Exploring differences among adolescents in the Southwest. Journal of Community Psychology. 2003;31:167–188. doi: 10.1002/jcop.10041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulis S, Marsiglia F, Sicotte F, Nieri TD. Neighborhood effects on youth substance use in a southwestern city. Sociological Perspectives. 2007;50:273–301. doi: 10.1525/sop.2007.50.2.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFromboise T, Coleman HLK, Gerton J. Psychological impact of biculturalism: Evidence and theory. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114:395–412. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.3.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza ST, Flaherty BP, Collins LM. Latent class and latent transition analysis. In: Schinka JA, Velicer WF, editors. Handbook of Psychology: Vol. 2. Research methods in psychology. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2003. pp. 663–685. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen LJ. The foreign-born population in the United States: 2003. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2004. (Current Population Report P20-551) [Google Scholar]

- Liebkind K. Ethnic identity and acculturation. In: Sam DL, Berry JW, editors. The Cambridge handbook of acculturation psychology. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2006. pp. 78–96. [Google Scholar]

- Marin G, Sabogal R, Marin BV, Otero-Sabogal R, Perez-Stable EJ. Development of a short acculturation scale for Hispanics. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Science. 1987;9:183–305. [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Kulis S, Hecht ML, Sills S. Ethnicity and ethnic identification as predictors of drug norms and drug use among pre-adolescents in the Southwest. Substance Use & Misuse. 2004;39:1061–1094. doi: 10.1081/ja-120038030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JN, Nakayama TK. Intercultural communication in context. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Masgoret A-M, Ward C. Culture learning approach to acculturation. In: Sam DL, Berry JW, editors. The Cambridge handbook of acculturation psychology. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2006. pp. 58–77. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow AH. Motivation and personality. 2nd ed. New York: Harper & Row; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra RC, Sinha D, Berry JW. Ecology: Acculturation and psychological adaptation among Adivasi in India. New Delhi: Sage; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen HH, Messé LA, Stollak GE. Toward a more complex understanding of acculturation and adjustment: Cultural involvement and psychosocial functioning in Vietnamese youth. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1999;30:5–31. [Google Scholar]

- Norris AE, Ford K, Bova CA. Psychometrics of a brief acculturation scale for Hispanics in a probability sample of urban Hispanic adolescents and young adults. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1996;18:29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. Ethnic identity in adolescents and adults: Review of research. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:499–514. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. The multigroup ethnic identity measure: A new scale for use with diverse groups. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1992;7:156–176. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. Ethnic identity and acculturation. In: Chun KM, Balls-Organista P, Marin G, editors. Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2003. pp. 63–81. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, Devich-Navarro M. Variations in bicultural identification among African American and Mexican American adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1997;7:3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, Romero I, Nava M, Huang D. The role of language, parents, and peers in ethnic identity among adolescents in immigrant families. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2001;30:135–153. [Google Scholar]

- Portes A, Rumbaut RG. Legacies: The story of the immigrant second generation. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sam DL. Acculturation: Conceptual background and core components. In: Sam DL, Berry JW, editors. The Cambridge handbook of acculturation psychology. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2006. pp. 11–26. [Google Scholar]

- Sam DL, Berry JW. Introduction. In: Sam DL, Berry JW, editors. The Cambridge handbook of acculturation psychology. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2006. pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Montgomery MJ, Briones E. The role of identity in acculturation among immigrant people: Theoretical propositions, empirical questions, and applied recommendations. Human Development. 2006;49:1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Seaton EK, Scottham KM, Sellers RM. The status model of racial identity development in African American adolescents: Evidence of structure, trajectories, and well-being. Child Development. 2006;77:1416–1426. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H, Turner J. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In: Worchel S, Austin W, editors. Psychology of intergroup relations. Chicago: Nelson-Hall; 1986. pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Unger JB, Gallaher P, Shakib S, Ritt-Olson A, Palmer PH, Johnson CA. The AHIMSA acculturation scale: A new measure of acculturation for adolescents in a multicultural society. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2002;22:225–251. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. New York: UN Statistics Division; UN population report 2002. 2002

- U.S. Census Bureau. We the people: Hispanics in the United States. 2004 Retrieved October 6, 2005, from http://www.census.gov/prod/2004pubs/censr-18.pdf.

- Valentine S, Mosley G. Acculturation and sex-role attitudes among Mexican Americans: A longitudinal analysis. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2000;22:104–113. [Google Scholar]

- Verkuyten M, Drabbles M, van den Nieuwenhuijzen K. Self-categorization and emotional reactions to ethnic minorities. European Journal of Social Psychology. 1999;29:605–619. [Google Scholar]

- Vermunt JK, Magidson J. Latent class cluster analysis. In: Hagenaars JA, McCutcheon AL, editors. Applied latent class analysis. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2002. pp. 89–106. [Google Scholar]

- Ward C, Bochner S, Furnham A. The psychology of culture shock. New York: Routledge; 2001. [Google Scholar]