Abstract

Recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (RDEB) is caused by loss-of-function mutations in COL7A1 encoding type VII collagen which forms key structures (anchoring fibrils) for dermal–epidermal adherence. Patients suffer since birth from skin blistering, and develop severe local and systemic complications resulting in poor prognosis. We lack a specific treatment for RDEB, but ex vivo gene transfer to epidermal stem cells shows a therapeutic potential. To minimize the risk of oncogenic events, we have developed new minimal self-inactivating (SIN) retroviral vectors in which the COL7A1 complementary DNA (cDNA) is under the control of the human elongation factor 1α (EF1α) or COL7A1 promoters. We show efficient ex vivo genetic correction of primary RDEB keratinocytes and fibroblasts without antibiotic selection, and use either of these genetically corrected cells to generate human skin equivalents (SEs) which were grafted onto immunodeficient mice. We achieved long-term expression of recombinant type VII collagen with restored dermal–epidermal adherence and anchoring fibril formation, demonstrating in vivo functional correction. In few cases, rearranged proviruses were detected, which were probably generated during the retrotranscription process. Despite this observation which should be taken under consideration for clinical application, this preclinical study paves the way for a therapy based on grafting the most severely affected skin areas of patients with fully autologous SEs genetically corrected using a SIN COL7A1 retroviral vector.

Introduction

Recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (RDEB, OMIM #226600), one of the most severe genodermatoses in children and young adults, is characterized by blistering of the skin and mucosae since birth, milia, and mutilating scarring. Four major clinical subtypes are recognized from the most severe forms to the mildest including severe generalized (Hallopeau-Siemens-RDEB), generalized-other (mitis), inversed and localized forms. Severe complications include local and systemic infections, malnutrition, joint contracture, and fusion of fingers and toes in Hallopeau-Siemens-RDEB resulting in poor functional prognosis. The majority of patients with Hallopeau-Siemens-RDEB die from invasive squamous cells carcinomas. RDEB is caused by loss-of-function mutations in the COL7A1 gene encoding type VII collagen, the component of anchoring fibrils, which attach the basement membrane to the underlying dermis.1 To date, there is no specific treatment for RDEB, but progresses in viral vectors design allow efficient transfer of the large COL7A1 complementary DNA (cDNA) (8.9 kb) into epidermal stem cells. Following the success of the gene therapy clinical trial of junctional epidermolysis bullosa by the group of Michele De Luca,2 gene therapy approaches hold great hope for this devastating disease.

Several groups have reported preclinical studies toward ex vivo gene therapy of RDEB.3,4,5,6,7,8 These studies provide a strong rationale to develop clinical gene therapy protocols for this disease. Ortiz-Urda and co-workers developed a nonviral method to correct RDEB fibroblasts3 and keratinocytes4 that required, due to a poor transfection efficiency, a selectable marker for antibiotic selection of transduced cells. Gache and co-workers used a classical retroviral gene transfer to transduce primary RDEB keratinocytes.8 While transduction efficiency was higher (~40%), the zeocin-resistance gene was used to select transduced cells. In this case, COL7A1 expression was driven by the viral long-terminal repeat (LTR) containing a strong enhancer located in its U3 region, previously associated with a higher risk of insertional mutagenesis.9 In both reports, selection of transduced cells with antibiotics implied that a prokaryotic resistance gene was added to the integrated construction, thus precluding their use for clinical trials. In parallel, Woodley's group has successfully transduced an immortalized RDEB keratinocyte cell line and primary RDEB fibroblasts using a self-inactivating (SIN) lentiviral vector encoding type VII collagen under the control of a retroviral promoter (MND).5,7

Serious adverse events occurring in the first successful gene therapy trial for X-SCID have led to consider SIN vectors instead of classical retroviral vectors. SIN vectors lack the strong U3 enhancer capable of transactivating sequences at a distance up to 270 kb.10 This enhancer was shown to upregulate the LMO2 proto-oncogene in two of the three X-SCID patients who developed leukemia in the course of this gene therapy trial.9 Moreover, in SIN vectors the transgene is expressed through an internal promoter. This safety feature allows using cellular promoters that may provide physiological regulation of transgene expression. SIN vectors significantly reduce the frequency of insertional adverse events compared to vectors with LTR-driven expression of the transgene.11 However, the subsequent requirement for an internal promoter to drive transgene expression does not completely abolish the potential for unwanted transactivation events, and the choice of the expression cassette is therefore of importance. An ideal promoter for use in integrating vectors is one that is able to drive high levels of transcription, or even better tissue-specific and regulated expression of the transgene, and which is also unlikely to affect the transcriptional state of nearby cellular genes. LTR-derived promoters such as MND (from the myeloproliferative sarcoma virus) or spleen focus-forming virus (from the Friend spleen focus-forming virus) are often used in SIN retroviral or SIN lentiviral constructs.7,12 However, these promoters contain strong enhancer elements known to be responsible for adverse transactivation of proto-oncogenes.13

We have developed a new minimal SIN retroviral backbone permitting reasonably high titers productions, from which we derived two vectors expressing type VII collagen under the control of human promoters. One contains a short COL7A1 promoter providing tissue-specific and regulatable expression, the second contains a short housekeeping gene promoter [elongation factor 1α (EF1α)] providing ubiquitous expression. Our results demonstrate long-term functional correction of RDEB in vivo, using grafts of genetically corrected human skin equivalents (SEs), with both COL7A1-expressing retroviral vectors.

Results

Generation of COL7A1-expressing retroviral vectors with human internal promoters

The full-length human COL7A1 cDNA (8.9 kb) was initially cloned into the pMSCV classical retroviral backbone developed by Grez et al.14 The full-length type VII collagen cDNA was inserted into pMSCV at the single MfeI site. In this construct (MSCV-COL7A1), COL7A1 expression was driven by the viral promoter located in the 5′LTR of the integrated provirus. Because of the risk of oncogenesis due to an insertional mutagenesis event associated with conventional retroviral vectors,15 we decided to use SIN vectors, which are deleted in the regulatory elements present in the U3 region of the 3′LTR, preventing the activation of an oncogene nearby the integration site of the transgene expressing provirus. From the existing pBullet classical vector,16 we developed a new minimal SIN retroviral vector (Supplementary Figure S1). We first removed the entire gag (400 bp) and pol (350 bp) coding regions from the pBullet vector. Then, we removed the promoter and enhancer sequences from the U3 region in 3′LTR of MFG vector (300 and 400-bp deletions in the U3 region of 3′LTR) creating the pCMS retroviral backbone. Finally, we cloned COL7A1 expression cassettes into this vector containing two different human promoters to drive COL7A1 cDNA expression. Due to the large size of the COL7A1 cDNA (8.9 kb), these promoters should be as short as possible, while maintaining good levels of expression both in basal keratinocytes and in dermal fibroblasts. One is a 616-bp long COL7A1 promoter, extending from ‐524 to +92 relative to the transcription start site, which contains all the essential functional elements and was previously shown to ensure tissue-specific and regulated expression of type VII collagen.17,18 The other is a 237 bp intron-less promoter from a housekeeping gene, the EF1α, which ensures high-level and ubiquitous expression of the transgene.19 The two different SIN retroviral vectors expressing COL7A1 cDNA (Supplementary Figure S1) were named pCMS-COL7A1-COL7A1, in which COL7A1 expression is driven by its own promoter, and pCMS-pEF1α-COL7A1, in which COL7A1 expression is under the control of the EF1α promoter.

Production of the SIN vectors

Both SIN vectors were initially produced using a transient tri-transfection procedure in human embryonic kidney 293T cells. However, great variability in viral titers steered us toward the development of a stable producer clone. Viral supernatants titers ranged from 1.105–5.106 intraperitoneal (i.p.)/ml for raw supernatants and from 1.107 up to 5.108 i.p./ml for concentrated supernatants. Supplementary Table S1 summarizes the data on the production and titration of the viral supernatants. A great variability of titer and transduction efficiencies was observed.

The use of a stable producer clone allowed for easier quality control, a better standardization procedure, and the production of viral batches with defined and reproducible titers. In collaboration with the InsertAgene European commission-funded project, we developed stable producer clones for both COL7A1 SIN vectors using a newly established packaging cell line allowing for easy cassette exchange through a flp recombination.20 Only the pCMS-EF1α-COL7A1 gave rise to a stable producer clone with a high titer (2.106 i.p./ml on average). This producer clone allowed for easier production of viral supernatants with high and reproducible titers with more reproducible type VII collagen expression levels (Supplementary Table S1). However, due to the design of the exchange cassette, a high rate of viral particles contained the NeoR gene as described elsewhere.21

Supernatants with high titers produced with either process showed similar transduction efficiency on primary cells. In each experiment, cells treated using the pCMS-EF1α-COL7A1 supernatants arising from the producer clone are designated with an asterisk (*).

Primary keratinocyte and fibroblast transduction

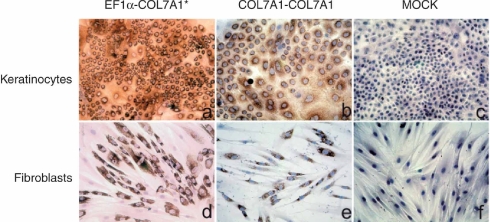

Primary RDEB keratinocytes (Krdeb) and fibroblasts (Frdeb) were cultured from a skin biopsy taken from a Hallopeau-Siemens-RDEB patient carrying a homozygous COL7A1 c.189delG mutation in exon 2.22 This deletion leads to a frameshift and a premature translation termination 70 codons downstream (p.Leu64TrpfsX40). This patient shows complete absence of type VII collagen expression on immunohistochemistry of skin sections and western blotting, and a drastic reduction in COL7A1 mRNA as a result of nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Krdeb and Frdeb were transduced twice at 24-hour interval with either the pCMS-COL7A1-COL7A1 vector or with the pCMS-EF1α-COL7A1 vector at a multiplicity of infection of 20. Efficient viral supernatant batches allowed for a high level of transduction without antibiotic selection (Figure 1). Expression of recombinant type VII collagen was detected in 30–80% of keratinocytes (Figure 1a,b) and in 38–70% of fibroblasts (Figure 1d,e) depending on the viral supernatant lot or the transduction experiment (Supplementary Table S1). For both vectors, cell populations with the highest transduction efficiency were used for further studies.

Figure 1.

Ex vivo transduction of primary RDEB keratinocytes and fibroblasts. Immunodetection of type VII collagen in (a–c) RDEB keratinocytes and (d–f) RDEB fibroblasts before and after transduction. (a,d) RDEB keratinocytes and fibroblasts transduced with the pCMS-EF1α-COL7A1 retroviral vector produced with the stable producer clone. (b,e) RDEB keratinocytes and fibroblasts transduced with the pCMS-COL7A1-COL7A1 retroviral vector. (c,f) Nontransduced RDEB keratinocytes and fibroblasts. An average of 60% of the keratinocytes and 70% of fibroblasts were transduced in these experiments. EF1α, elongation factor 1α RDEB, recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa.

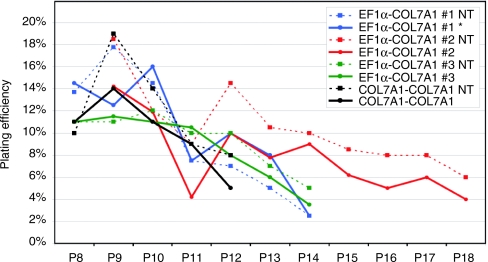

The proliferative capability of the cells was addressed by serial transfer as previously described.23 Four independent plating efficiency experiments demonstrated that transduced cells did not display altered proliferative capabilities compared to untreated cells (Figure 2). These results demonstrate that transduction is not harmful to the cells as both corrected and uncorrected cellular populations show similar cellular quality and life span potential.

Figure 2.

Plating efficiency analysis. Transduced cells with both the pCMS-COL7A1-COL7A1 and the pCMS-EF1α-COL7A1 viral vectors showed similar plating efficiency when compared to untransduced cells of the same experiment. Cells arised from the same patient biopsy were transduced at passage 5 and maintained for 7 up to 13 consecutive passages depending on the experiment. *Cells transduced with pCMS-EF1α-COL7A1 supernatant produced using the producer clone. EF1α, elongation factor 1α NT, nontransduced.

Analysis of integrated provirus

Real-time PCR analysis of genomic DNA was used to estimate the number of integrated provirus in transduced cells in four different experiments. Each time cells were transduced twice at a multiplicity of infection of 20. Results showed the presence of 1–3 integrated copies per transduced cell on average, in keratinocyte and fibroblast transduced with both SIN retroviral vectors (Supplementary Table S2).

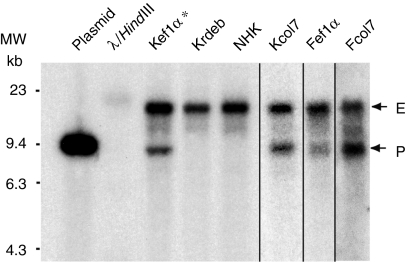

Southern blot experiments demonstrated the presence of a full-length provirus of about 9.6 kb in transduced cells for both viral constructs (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Characterization of the integrated provirus. Southern blot experiments were carried out on genomic DNA of keratinocytes and fibroblasts transduced with either the pCMS-EF1α-COL7A1 or the pCMS-COL7A1-COL7A1 SIN retroviral vectors. HindIII + EcoRV fragments of genomic DNA were probed with a 9 kb 32P-labeled fragment corresponding to the full-length COL7A1 cDNA. Single bands of 9.6 kb (EF1α-COL7A1 construct) or 10 kb (COL7A1-COL7A1 construct) corresponding to the full-length provirus (P) were detected together with a 15 kb fragment corresponding to the endogenous COL7A1 gene (E). *Cells transduced with pCMS-EF1α-COL7A1 supernatant produced using the producer clone. cDNA, complementary DNA; EF1α, elongation factor 1α.

Furthermore, we have amplified the 9.5 kb expression cassette isolated from genomic DNA of cells transduced with the pCMS-EF1α-COL7A1 vector using three overlapping PCR fragments. Direct sequencing analysis and sequencing of plasmid clones confirmed that the integrated provirus sequence was identical to the theoretical sequence (data not shown).

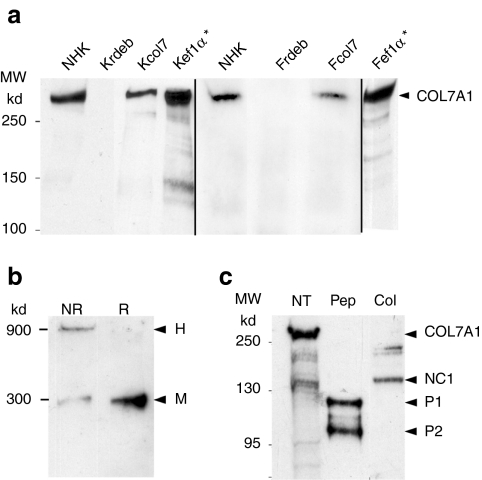

Purification and characterization of biochemical properties of recombinant type VII collagen

Western blot analysis (Figure 4a) of conditioned medium from normal human keratinocytes (NHK), normal human fibroblasts, RDEB keratinocytes or fibroblasts transduced with either of the SIN retroviral vectors (Kcol7, Kef1  Fcol7, and Fef1α) showed a 300 kd band corresponding to type VII collagen monomers. In contrast, no band was detected from the Krdeb or Frdeb media.

Fcol7, and Fef1α) showed a 300 kd band corresponding to type VII collagen monomers. In contrast, no band was detected from the Krdeb or Frdeb media.

Figure 4.

Characterization of biochemical properties of recombinant type VII collagen. SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis of type VII collagen was carried out with monoclonal antibody (a) LH7:2 or (b,c) a polyclonal antibody. (a) Protein extracts from NHK, Krdeb, Kcol7, and Kef1α culture supernatant run on a 4% acrylamide gel. A single band around 300 kd corresponding to type VII collagen is present in NK, Kcol7, and Kef1α while absent in Krdeb. (b) Type VII collagen FPLC-purified from transduced cells supernatant analyzed on a 4–12% gradient gel either directly on nonreducing conditions (NR) or after reduction with β-mercaptoethanol (R), showing the presence of both monomers (M, 300 kd) and homotrimers (H, ~900 kd) of type VII collagen. (c) Purified type VII collagen run on a 7% gel. Type VII collagen monomers (300 kd) were detected without protease treatment (NT), whereas digestion with pepsine (Pep) released the triple-helical domain (TH) and its two pepsin-resistant fragments, P1 and P2. Collagenase digestion (Col) left the NC1 domain intact. *Cells transduced with pCMS-EF1α-COL7A1 supernatant produced using the producer clone. FPLC, fast protein liquid chromatography; NHK, normal human keratinocytes; SDS-PAGE, sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

To study the biochemical properties of the recombinant type VII collagen, conditioned medium from RDEB keratinocytes transduced with the MSCV-COL7A1 retroviral vector was subjected to 4–12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Figure 4b). Under nonreducing conditions, a 900 kd band corresponding to type VII collagen trimers, and a 300 kd band corresponding to type VII collagen monomers were observed. Reducing conditions (R) converted all trimers into monomers, demonstrating that the recombinant type VII collagen assembled to form S-S bonded trimers in vitro.

To study the stability and the triple-helical conformation of recombinant type VII collagen, fast protein liquid chromatography-purified type VII collagen (Figure 4c) was treated with pepsin and collagenase and then subjected to immunoblot analysis. As described previously,24 pepsin digestion produced the 120 and 110 kd protease-resistant P1 and P2 collagenous fragments, respectively and collagenase digestion released the 145 kd NC1 domain. These results are consistent with previous studies performed on native type VII collagen purified from human amnion, which showed that the noncollagenous NC1 and NC2 domains of type VII collagen were degraded by pepsin while the triple-helical domain mostly resisted digestion, except for a partial cleavage into the P1 and P2 fragments in the hinge region of the collagenous domain.25 The resistance to pepsin digestion provides evidence that recombinant type VII collagen adopts a triple-helical conformation.26

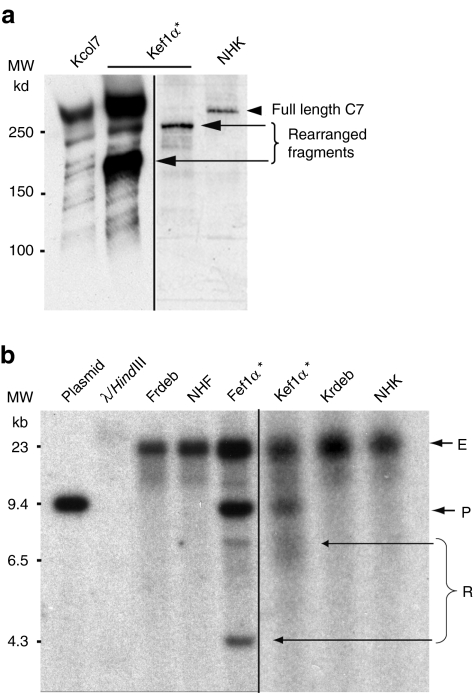

Provirus rearrangement events

Western blot analysis of transduced keratinocyte protein extracts revealed the presence of shorter bands in 3/12 experiments (Figure 5a). These events were not seen in transduced fibroblasts (seven experiments). To distinguish between type VII collagen degradation and provirus rearrangement, we performed Southern blot experiments of genomic DNA from transduced cells (Figure 5b). Southern blot analysis revealed smaller bands corresponding to rearranged forms of the provirus in 3/9 different keratinocyte transduction experiments and in 1/3 fibroblast experiments. Supplementary Table S3 summarizes the rearrangements found at the protein and DNA levels. Interestingly, some rearrangements evident at the protein level are not evident at the DNA level, and vice versa. Southern blot analysis is useful to detect major rearrangements (gross insertions/deletions) but cannot detect point mutations or small insertions/deletions that can lead to the synthesis of a truncated protein detectable by western blot. Conversely, a rearrangement at the DNA level will not always lead to the synthesis of a mutant protein, because the mutant mRNA can result in a frameshift and be degraded through nonsense-mediated mRNA decay.

Figure 5.

Analysis of type VII collagen rearrangements. (a) Some western blot experiments (3/12) of cell protein extracts from transduced keratinocytes using the polyclonal antitype VII collagen antibody showed the presence of shorter immunoreactive bands which likely correspond to truncated proteins arising from a rearranged transgene. (b) Southern blot experiments confirmed in some cases (3/9) the presence of shorter provirus fragment (R) in addition to the endogenous fragment (E) and the normal provirus (P). These shorter proviruses, probably resulted from a rearrangement event during reverse transcription. In contrast, no shorter protein fragment was detected by western blot analysis of transduced fibroblast extracts (seven experiments), although a shorter provirus form could be seen on one Southern blot experiment (out of three experiments). *Cells transduced with pCMS-EF1α-COL7A1 supernatant produced using the producer clone. EF1α, elongation factor 1α.

To investigate the possibility of genomic RNA recombination into viral vector particles, we performed northern blot experiments using vector supernatants from both SIN vectors (Supplementary Figure S2). Bands of expected sizes (around 10 kb) were detected for both SIN vectors with no evidence for RNA rearrangement into vector particles, including the viral supernatant which was used to transduce keratinocytes and fibroblasts showing rearranged proviruses (Figure 5).

Moreover, in several independent transduction experiments made with the same viral supernatant, rearrangements were detected only in a few experiments and generated bands of different sizes. It is thus likely that these rearrangements occurred during the retrotranscription process within transduced cells.

Regulation of recombinant type VII collagen

The minimal COL7A1 promoter contains known regulatory elements controlling type VII collagen expression, including the response to transforming growth factor-β and retinoic acid.17,18 We compared the effect of these two compounds on the COL7A1 expression on cells transduced with the pCMS-COL7A1-COL7A1 vector by measuring the amount of type VII collagen mRNA by real-time PCR (Supplementary Figure S3). These results demonstrate that in the context of a retroviral integration, the short COL7A1 promoter preserves its capacity to respond to physiological regulation signals.

Long-term in vivo functional correction

To demonstrate long-term functional correction, we used human SEs grafted onto immunodeficient mice. SE systems generate human skin tissues that retain the RDEB disease phenotype.27 They have been widely used in the past to demonstrate functional correction of RDEB.4,7,8 These systems allow for the testing of the entire grafting protocol using human cells genetically corrected with the human cDNA. We have produced SEs using RDEB keratinocytes and fibroblasts transduced with either viral vector (pCMS-COL7A1-COL7A1 and pCMS-EF1α-COL7A1). Type VII collagen expression was detected in 60 and 70% of the keratinocytes and fibroblasts with the pCMS-COL7A1-COL7A1 vector, and 50% on each cell type with the pCMS-EF1α-COL7A1.

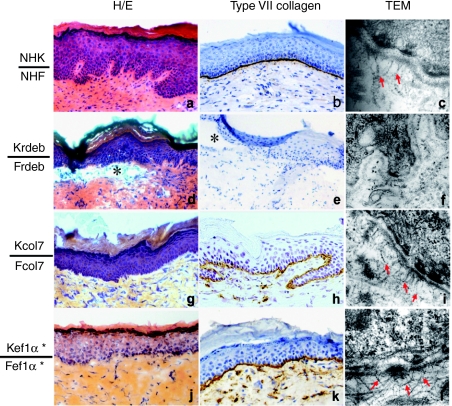

SEs made of normal cells (NHK and normal human fibroblasts), or genetically corrected RDEB keratinocytes and fibroblasts (Kcol7, Fcol7 and Kef1α, Fef1α), or untransduced RDEB cells (Krdeb and Frdeb) were grafted onto SCID mice. Five months postgrafting, SEs made of normal cells displayed a well-differentiated epidermis adherent to the underlying dermis (Figure 6a,b). In contrast, a characteristic dermal–epidermal blister (*) was seen in the uncorrected SE (Figure 6d,e). In SEs made of NHK and normal human fibroblasts, immunohistological staining revealed the presence of type VII collagen at the dermo–epidermal junction (Figure 6b), whereas no staining was detected in SEs made of uncorrected RDEB cells (Figure 6e). SEs made of RDEB keratinocytes and fibroblasts corrected with either vector displayed restored dermal–epidermal adherence (Figure 6g,j) and the presence of type VII collagen along the dermal–epidermal junction (Figure 6h,k).

Figure 6.

In vivo restoration of type VII expression and epidermal adherence in RDEB reconstructed skin. Histological analysis, type VII collagen immunostaining, and transmission electron microscopy analyses at 5 months postgrafting of SEs made of (a–c) NHK and NHF, (d–f) Krdeb and Frdeb, (g–i) Kcol7 and Fcol7, and (j–l) Kef1α and Fef1α. Type VII collagen accumulates along the dermal–epidermal junction in normal SE and in both genetically corrected SEs, whereas it is completely absent in SE made of uncorrected RDEB cells. Note the dermo–epidermal cleft (*) in the SE made of (d,e) uncorrected RDEB cells, whereas no blistering is seen in (g,h,j,k) genetically corrected SE. *Cells transduced with pCMS-EF1α-COL7A1 supernatant produced using the producer clone. Anchoring fibrils (arrows) were present below the lamina densa in all SEs except for the SE made of uncorrected RDEB cells (the picture was taken in a nonblistering area). The hemidesmosomes (HD) appear normal. Original magnification ×50,000. EF1α, elongation factor 1α NHF, normal human fibroblast; NHK, normal human keratinocytes; RDEB, recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa; SE, skin equivalent.

Dermal–epidermal junction in RDEB is characterized by the absence of functional anchoring fibrils. We performed transmission electron microscopy studies to determine whether anchoring fibrils were present in SEs made of genetically corrected RDEB cells (Figure 6). The SE models displayed a well defined dermal–epidermal junction, with marked lamina lucida and densa, and normal hemidesmosomes. Functional anchoring fibrils (arrows) were detected below the lamina densa in SEs made of normal cells (Figure 6c), in SEs made of Kcol7 and Fcol7 (Figure 6i), as well as in SEs made of Kef1α and Fef1α (Figure 6l). In contrast, no anchoring fibrils were detected in noncorrected RDEB cells (Figure 6f). The anchoring fibrils bending, striation, size, and number were comparable between corrected and normal reconstructed skin.

Similar results were obtained using different combinations of genetically corrected versus noncorrected RDEB keratinocytes or fibroblasts, demonstrating that the presence of only one cell type (keratinocytes or fibroblasts) is sufficient to achieve type VII collagen expression and localization at the basement-membrane zone, formation of anchoring fibrils and to restore dermal–epidermal adherence (Supplementary Figure S4).These results show that correction of either cell type has the potential to restore functional correction and to prevent skin blistering.

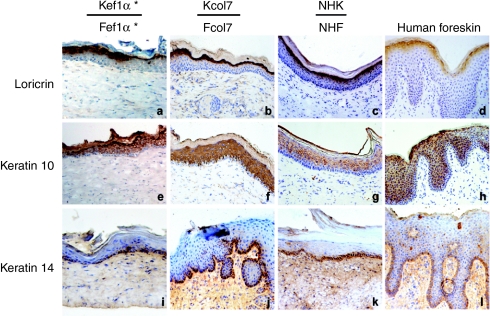

Analysis of epidermal differentiation markers

To ensure that neither the genetic correction nor the SE procedures altered the differentiation capability of keratinocytes, we studied the expression of three major epidermal differentiation markers: keratin 14, keratin 10, and loricrin (Figure 7) in SEs. SEs made of transduced cells were compared with normal reconstructed skin and normal human foreskin. The expression of loricrin, a granulous layer marker, of keratin 10, found in all suprabasal layers and of keratin 14, synthesized only in the basal layer, was identical in the three skin types.

Figure 7.

Differentiation pattern in reconstructed skins. At 5 months postgrafting, the expression of three major epidermal differentiation markers was compared between corrected SE, normal reconstructed skin and normal human foreskin. The immunostaining patterns of (a–d) loricrin, (e–h) keratin 10, and (i–l) keratin 14 are identical throughout. *Cells transduced with pCMS-EF1α-COL7A1 supernatant produced using the producer clone. EF1α, elongation factor 1α.

Biosafety assays

There are two major safety issues concerning this ex vivo gene therapy approach for RDEB. One is the potential genotoxicity associated with the integrative vector of the retroviridae family. The use of a SIN vector should considerably lower this risk, however, we have investigated the possible tumorigenic effect of cell transduction. The other concern is the potential immune response toward the newly synthesized type VII collagen in patients who do not express this protein or only express truncated or mutant form of this protein. Because we do not reconstruct the immune system of the patient during the medical procedure, it is likely that at least in a subset of patients the newly expressed protein will be considered as nonself.

To investigate any tumorigenic effect of patient cells treated by gene therapy, subcutaneous injections of NHK and fibroblasts (NHK and normal human fibroblasts), RDEB keratinocytes and fibroblasts (Krdeb and Fredb) and RDEB keratinocytes and fibroblasts transduced with the pCMS-COL7A1-COL7A1 SIN retroviral vector (Kcol7 and Fcol7) were performed onto nude mice. Cells were harvested when in log-phase growth. 2.106 cells were resuspended in 50 µl of phosphate-buffered saline and injected subcutaneously into 6-week-old immunocompromised athymic nude mice. HeLa cells were injected as positive controls. Supplementary Table S4 summarizes the experiments performed and the number of mice involved.

Mice were monitored daily during the first 2 weeks, and then twice a week. Only the positive controls (HeLa cells) developed tumors. When tumors reached a diameter of 1 cm, mice were sacrificed for ethical reasons, and tumors were collected. Half of the tumor was plated into a culture dish, and the other half was fixed in 10% formalin for histological examination. Histological and immunohistological analysis (using the MN116 antibody raised against human cytokeratins) were consistent with the development of an adenocarcinoma originated from HeLa cells (data not shown). Mice which developed no tumor showed no sign of illness and were sacrificed after 1 year of follow-up.

To further study any tumorigenic adverse event, 17 mice grafted with SEs made of genetically engineered cells, or uncorrected patient's cells, or normal human cells were monitored and analyzed. Twelve out of the seventeen mice showed a good graft uptake (70%). From 70 to 163 days, these 12 mice were sacrificed, carefully examined for any sign of sickness and the grafts were removed and analyzed by immunohistochemistry. In addition, liver, lung, and ovaries were taken, fixed, and embedded in paraffin for histological analyses.

Only one mouse developed sickness and was sacrificed after 70 days of engraftment because of the extreme weight loss observed. This mouse developed a lymphoproliferative disorder not due to the transduction procedure, as this mouse was grafted with nongenetically engineered cells. The other mice did not show any sign of illness and histological analyses of their liver, lungs, and ovaries did not reveal any tumor formation (Supplementary Table S5).

To assess the risk of immune response to type VII collagen, we developed and validated enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot assay.28 These tests address B and T cell-mediated pre-existing immunity toward type VII collagen and will be essential for the enrolment and the monitoring of patient in further clinical trials.

Discussion

We described herein the functional correction of both primary RDEB keratinocytes and fibroblasts using safe retroviral vectors expressing the full-length COL7A1 cDNA under the control of human promoters. The SIN strategy allows for a safer gene transfer by minimizing the risk of insertional mutagenesis. Recent works clearly demonstrate that transcriptionally active (i.e., non-SIN) LTRs are the major determinants of genotoxicity and thus that SIN vectors have greater therapeutic potential.29,30,31

The use of the tissue-specific COL7A1 promoter adds another security level to the construct, ensuring that transgene expression is restricted to basal keratinocytes and dermal fibroblasts. However, even ubiquitous human promoters such as EF1α greatly decrease the risk of insertional transformation.11 In our setting, the risk of insertional mutagenesis is also minimized by the fact that the average copy number of integrated transgene is around 1–3 per cell, and by the low number of the initial transduced cells (100,000). Moreover, no tumor formation was observed in the nude mice up to 11 months after subcutaneous injection of genetically corrected cells, neither in mice grafted with genetically corrected SEs (up to 6 months of follow-up). These results strongly support the lack of tumorigenic event in the transduced cells.

Although SIN lentiviral vectors offer advantages over SIN retroviral vectors (i.e., infection of quiescent cells and larger cargo capacity) and may be preferred for certain cell types, and after having compared both COL7A1-expressing lentiviral and retroviral vectors, we have chosen retroviral vectors for their high efficiency on keratinocytes and fibroblasts (which are actively dividing in culture). In our hands, lentiviral vectors containing the large and highly repeated COL7A1 cDNA did not allow to obtain significant transduction efficiency in contrast to their retroviral counterparts (data not shown), as also observed by others (F. Mavilio, personal communication).

Several hypotheses may account for this observation. Either the synthesis of the lentiviral genomic RNA is difficult in the packaging cells due to the large size and the nature of the COL7A1 cDNA (cryptic splice sites, repetitive sequences), which may explain the very low titers observed and the absence of viral RNA as demonstrated by northern blot on lentiviral supernatants (data not shown). Alternatively, the retrotranscription process in the lentiviral context may be less efficient considering the size and nature of the cDNA, in particular because the retrotranscription of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) genome may be more prone to genetic recombination than in gammaretroviruses, despite similar template switching activity of their retrotranscriptases.32

These results contrast with the results obtain by Chen et al. who have used a HIV-based vector to transduce a keratinocyte cell line and primary human fibroblasts.5,7 Unfortunately, this vector was not available for comparison studies with our HIV-based COL7A1 vectors. Both vectors are Tat-independent SIN vectors containing the Rev response element sequence and the central polypurine tract/central termination sequence. The vector used by Woodley et al. derives from the SMPU vector7 whereas we used a pRRL SIN backbone containing the central polypurine tract/central termination sequence and the woodchuck-hepatitis-virus postregulatory element sequences.33 Several differences between these vectors may account for the contrasting results obtained: (i) the promoter used to drive COL7A1 cDNA synthesis (Woodley's vector uses the MND promoter which is the U3 region of a MLV LTR. We have used the human COL7A1, phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK), and EF1α promoters), (ii) differences in the 5′LTR (in the pRRL backbone, the enhancer and promoter from the U3 region of Rous sarcoma virus are joined to the R region of the HIV-1 LTR,34 whereas in the SMPU vector, the enhancer and promoter of cytomegalovirus were joined to the R region of HIV-1), (iii) the inactivation of the splice donor site located in ψ in Woodley's vector, (iv) the presence of the woodchuck-hepatitis-virus postregulatory element sequence in our vector (which is thus larger), (v) the size of the ψ packaging sequence: Woodley's vector contains a minimal ψ signal that extends only 39 bp into the gag coding sequence, whereas our vector contains the entire ψ extended sequence. However, deletion experiments (full or partial deletion of ψ, deletion of the woodchuck-hepatitis-virus postregulatory element sequence) in our pRRL backbone indicate that the two latter hypotheses are less likely.

Several studies have highlighted the integration site differences between MLV-based vectors and HIV-based vectors with regard to the risk of insertional mutagenesis.35,36,37 MLV-based vectors have a preference to integrate near the transcription start site and integrate in the proximity of growth-controlling genes at a much higher frequency than lentiviral vectors,31,38 and this may lead to a greater risk of upregulating an oncogene. Analysis of integration sites will be performed in the context of the clinical trial, because the pattern of integration is expected to be different for each transduced cell population. However, HIV-based vectors strongly favor integration in active genes, and seem to present more gene inactivation events than the retrovirus-based vectors, which could be disruptive to the host cell genome as well.30

The development of this project has highlighted difficulties to transfer a large and repetitive cDNA using retro or lentiviral SIN vectors. We were first faced with inefficient viral supernatant production, which was overcome by the generation of a stable producer clone. Although this clone displayed constant titers (2.106 i.p./ml) and allowed for reproducible high levels of transduction efficiency (~60%), the presence at a high rate of viral particles containing the NeoR gene led to abandon the use of this clone for clinical application. Further experiments were made using the transient tri-transfection system which allowed for the production of viral supernatants with relatively high titers (up to 2.106 i.p./ml for raw supernatants). However, the production by transient tri-transfection of both SIN COL7A1 vectors remains delicate. This demonstrates the need for better viral vector production systems and packaging cells for SIN retroviral or lentiviral vectors. Recently, an improvement of the flp-based cassette exchange packaging cell line that we used to derive the stable produced clone has been described.21 This cell line does not produce viral particles containing the NeoR gene or a fully functional LTR, and therefore should allow for the production of SIN retroviral supernatants with reasonably high titers suitable for clinical applications.

Another issue was the detection of shorter collagen protein arising from a rearranged shorter provirus as demonstrated by Southern blot experiments. Sequencing of the truncated provirus revealed different deletions within the collagenous and NC2 domains (data not shown). This is probably due to the nature of the transgene, which is a large, GC-rich and repetitive cDNA and to the template switching activity of the retroviridae reverse transcriptase leading to the deletion of repeats.32 This should be taken under consideration for clinical applications, and testing for rearranged provirus should be part of the quality control of transduced cells before grafting onto patients. Thus, we plan to screen the transduced cell populations by Southern and western blot analyses to select for cell populations with no detectable rearrangement.

The possibility exists that abnormal type VII collagen molecules may trigger an immune response toward transduced cells, or act as dominant negative products. However, it is likely that a majority of rearranged provirus forms would not produce a stable mRNA and/or protein as a result of frameshifts generated by rearrangements. In a few cases however, truncated proteins may still be synthesized. In fact, we have sequenced integrated provirus in a transduced cell population showing rearranged provirus with truncated type VII collagen molecules and have confirmed the presence of deletions encompassing the collagenous and NC2 domains of the COL7A1 cDNA. These rearranged provirus (2.2 and 2.8 kb deletions) predicted the synthesis of truncated polypeptides which are expected to not be able to assemble into anchoring fibrils, because the homotrimerization of type VII collagen α1-chain occurs from the carboxy terminus to the amino terminus through the interaction of the NC2 domains. Moreover, out of the 60 nonsense COL7A1 mutations referenced in the HGMD database (www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk) none is dominantly inherited. This suggests that either the mutant mRNA or proteins are degraded, or that truncated proteins synthesized from theses mutant alleles do not act as dominant negative products.

Because the transduced cell populations will be screened by Southern blot and western blot analyses, the number of transduced cells grafted on the patient that may produce such truncated proteins will be low (under the detection threshold of these techniques). Thus, a cytotoxic immune response toward cells expressing the truncated proteins would destroy a limited number of cells. Should a humoral immune response be elicited, besides the destruction of truncated proteins, the worst case scenario involves the production of antibodies to the newly expressed wild-type protein due to secondary epitope spreading. However, we believe that under these conditions this risk should be low.

One way to circumvent the genetic instability issue could be the optimization of the COL7A1 cDNA to reduce the number and size of the sequence repeats or to destroy cryptic splice and polyA sites. It has been demonstrated that such transgene sequence optimization could result in higher viral titers and higher expression levels in X-linked chronic granulomatous disease cells.39

Despite these difficulties, we could demonstrate long-term in vivo expression of recombinant type VII collagen and formation of anchoring fibrils, attesting to the functional correction of RDEB cells. Long-term type VII expression over 5 months in vivo indicates that a subset of epidermal stem cells were indeed transduced and transplanted. Importantly, these cells regenerated a well-differentiated epithelium and a normal dermal–epidermal junction. We have used a SE system, that has already proven its efficacy in the treatment of burns,40 based on fibrinogen cryoprecipitate from human plasma, allowing for a completely autologous grafting procedure.

The biosafety of these SIN COL7A1 vectors, the absence of antibiotic selection, and the autologous SE system that we used constitute key assets for a clinical application. Significant improvements in the vital and functional prognosis are expected from successful grafting of genetically corrected SEs onto the most severely affected skin areas of patients. A major clinical benefit could indeed be expected from the treatment of hands, feet, chronic wounds, and/or following the excision of squamous cell carcinomas, which represent the first cause of death in these patients.

Materials and Methods

Informed consent was obtained from the patient's parents. This study was approved by the medical ethics committee of the Purpan Hospital (Toulouse, France) and conducted in accordance with the ethical principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki. Animal studies have been approved by the Inserm U563 review board.

Vector design and production. The minimal backbone (pCM) was generated in three steps from the previously described pBullet vector (Supplementary Figure S1).16 First, the pBullet 5′LTR and ψ (packaging region) sequences were obtained from the corresponding plasmid by ClaI/Nhe1 restrictions. Second, a fragment containing the 3′LTR was obtained from pBullet-eGFP by BspEI/AvrII restrictions. Finally, a synthetic multi cloning site (MCS) was designed using the MCS-FW and MCS-REV oligonucleotides (Supplementary Table S6). The above three fragments were ligated together into pBlueScript-SK (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) cleaved by ClaI and XbaI. The gag deletion is similar to previous published work with a resulting ψ sequence 16 bp longer than in the pMOIN vector of Yu et al.41

The pCM SIN (pCMS) backbone was obtained by inserting the blunted EagEI/StuI fragment containing the 3′LTR from pBullet-eGFP into pGL3 Basic (Promega, Madison, WI) cut with KpnI and HpaI and blunted. pGL3-3′LTR was then digested by NheI and SacI, hence deleting 387 bp from the U3 promoter region, blunted and ligated. The SIN 3′LTR was then cut out with BspEI and AvrII and inserted back into the pCM digested with BspEI and SpeI.

pCMS-COL7A1-COL7A1 and pCMS-EF1α-COL7A1 vectors were obtained by cloning both expression cassettes into the pCMS backbone using the MluI and EcoRV enzymes.

Amphotropic pseudotyped vectors were produced by transient transfection into human embryonic kidney 293T as previously described42 or from a stable producer clone for the pCMS-EF1α-COL7A1 vector.20 Vectors in culture medium were collected and used as raw supernatants or concentrated by ultracentrifugation. Viral supernatants titers were determined by real-time PCR as described in the quantitative PCR section, after transduction of HCT116 cells. The viral supernatant titer was 2.106 i.p./ml for the pCMS-EF1α-COL7A1 vector arising from the producer clone. Viral supernatant titers of both constructs produced by tri-transfection procedure ranged from 1.105 i.p./ml up to 5.106 i.p./ml for raw supernatants and from 1.107 up to 5.108 i.p./ml for concentrated supernatants (Supplementary Table S1). Using the same ampho pseudotyped vector backbone but expressing GFP, the measured yield after ultracentrifugation was 50%. In each experiment, cells transduced using the pCMS-EF1α-COL7A1 producer clone, are designated with an asterisk (*).

Cell culture. Primary human keratinocytes and fibroblasts were obtained from skin biopsies of a RDEB patient or healthy controls. Keratinocytes were cultured on a feeder layer of lethally irradiated mouse 3T3-J2 fibroblasts as described previously43,44 culture medium. Human fibroblasts and 3T3-J2, human embryonic kidney 293T, HCT116 (ATCC, Manassas, VA) cell lines were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Gibco BRL/Invitrogen; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (Hyclone, Logan, UT), 50 IU/ml penicillin, and 50 µg/ml streptomycin (Gibco BRL/Invitrogen). BeFa-MSCV-COL7A1 cells were grown in keratinocyte growth medium as above. All cells were grown at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

Retroviral infection. RDEB keratinocytes and fibroblasts were plated at a density of 10,000 cells/cm2 in six-well tissue culture plates. Cells were infected twice with viral suspensions at an multiplicity of infection of 20 in the presence of 8 µg/ml of polybrene (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO). Transduction efficiency was evaluated by immunocytochemistry and colony counting for keratinocytes and random microscopic filed counting for fibroblasts. For keratinocytes, 500, 1,000, and 2,000 cells were plated in separate wells of a six-wells dish and grown for a week. Colonies were stained using the LH7:2 antibody and counterstained using hematoxylin. Positive and negative colonies were counted under a binocular lens. For fibroblasts, after staining, 10 microscopic fields were photographed and cells were counted on each field.

Analysis of recombinant type VII collagen

Western blot analysis. Keratinocytes were grown for 48 hours in the presence of 20 ng/ml transforming growth factor-β2 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and 50 µg/ml ascorbic acid. Cell protein extracts were quantified and separated on either 4, 7, or 4–12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Western blotting was performed using the antitype VII collagen monoclonal antibody LH7.2 (1:2,500; Sigma Aldrich), specific to the NC1 domain, or with rabbit polyclonal antibody against human type VII collagen (1:1,500; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA). Secondary antibodies were horse anti-mouse and goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G antibodies, respectively, conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (1:5,000; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverley, MA).

Type VII collagen purification and protease digestion. To obtain large amounts of recombinant type VII collagen suitable for biochemical analysis, the BeFa RDEB keratinocyte cell line45 devoid of type VII collagen expression was transduced with the MSCV-COL7A1 retroviral vector, generating the BeFa-MSCV-COL7A1 cell line. Recombinant type VII collagen was purified from conditioned serum-free medium of BeFa-MSCV-COL7A1 cells as previously described24 and incubated with pepsin overnight at 4 °C, or with bacterial collagenase (clostridiopeptidase A, type III; Sigma Aldrich) at 37 °C for 2 hours. The digestion products were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and western blotting as described below.

Southern blot analysis. Genomic DNAs were digested with HindIII and EcoRV enzymes whose sites flank the COL7A1-COL7A1 or EF1α-COL7A1 cassettes in the vector. Digestions were fractionated and transferred onto Amersham Hybond N+ membranes (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK) using standard protocols. The membranes were probed with a 32P-labeled DNA fragment of 8.9 kb encompassing the full-length COL7A1 cDNA. After stringent washes, membranes were exposed on Kodak X-Omat LS films (Sigma Aldrich) for 2 weeks at ‐80 °C using two intensifier screens.

Quantitative PCR

All reactions were performed using the SYBR Green JumpStart Taq ReadyMix (Sigma Aldrich) in an ABI Prism 7000 Sequence Detection System (Life Technologies). Primers are listed in Supplementary Table S6.

Integrated copy number determination and viral supernatant titration. Each 25-µl PCR reaction contained 50 ng of template genomic DNA of transduced cells, or control cells, and forward and reverse primers (0.2 µmol/l each). Proviral sequence was amplified at the ψ boundary, using primers pCMS-FW and pCMS-REV. The ALB sequence was amplified using primers ALB-FW and ALB-REV. Standard curves were prepared using known copy numbers of ψ and ALB. The number of proviruses per transduced cell was determined after normalization of ψ with ALB assuming two ALB alleles per cell. Viral supernatant titers in copy/ml were calculated as: normalized copy value × number infected cells/volume vector (ml).

COL7A1 transcript quantification. NK, Kcol7, and Krdeb cells were treated with 20 ng/ml of transforming growth factor-β2 or 10 µmol/l of all-trans retinoic acid. COL7A1 mRNA expression was measured by real-time quantitative PCR using PGK1 mRNA as an internal standard. Reactions were performed with 0.6 µmol/l of primers COL7A1-FW, COL7A1-REV, PGK-FW, and PGK-REV. For COL7A1 cDNA amplification, the forward primer is designed to specifically amplify the wild-type sequence. cDNA amplification consisted of one cycle at 95 °C for 90 seconds, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 seconds, and 66 °C for 1 minute. Each experiment was performed three times in triplicate, and PCR efficiency was similar whatever the primers. COL7A1 mRNA was normalized to PGK1 mRNA and quantified relative to mRNA expression in untreated cells using the ΔΔCT method. The values were then normalized to that of untreated KEB, considered as the reference.

SE production and grafting onto SCID mice. Freeze-dried fibrinogen, obtained from human plasma of blood donors, was reconstituted with 6 ml of sterile phosphate-buffered saline, and mixed with 106 fibroblasts in 17 ml of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and 0.44 mg/ml tranexamic acid (Sigma Aldrich). The fibrin–fibroblast mix was dispensed into a 12-well culture plate and keratinocytes were subsequently seeded on top. SEs were grafted onto the dorsal region of SCID mice using a skin flap procedure. SEs were stitched to the thoracic wall and covered with a dressing of urgotul (Laboratoires Urgo, Chenove, France) and silicone sheeting (Perouse plastie, Bornel, France). 21–26 days later, the flap was excised, and the rim of the graft was stitched to the mouse skin and protected with a bandage for 3 days. Implants were harvested 12–22 weeks after grafting and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen in OCT medium (Takara, Shiga, Japan) or processed for electron microscopy analysis. SCID mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (L'Arbresle, France). A total of 43 mice were engrafted with genetically modified SE (all types).

Immunocytochemistry and immunohistochemistry. Immunocytochemistry was performed on methanol-fixed cells. Hematoxylin–eosin staining and immunostaining were performed on SE frozen sections previously fixed with acetone. Antibodies against human type VII collagen were mAb LH7.2 (1:1,000) and pAb antihuman type VII collagen (1:250). Antibodies against loricrin (1:400; Eurogentec, Angers, France), keratin 10 (1:500, Eurogentec), and keratin 14 (1:100; Abcam) were used. For the tumorigenicity test, the monoclonal antibody MNF116 to human cytokeratins was used (DakoCytomation, Trappes, France). Detection was performed using the EnVision System+ HRP (DakoCytomation) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Transmission electron microscopy. Tissues were fixed in 4% glutaraldehyde in Sorensen's buffer, pH 7.4 for 1 hour at 4 °C, rinsed twice in Sorensen's buffer for 12 hours at 4 °C and then postfixed for 1 hour at room temperature in 0.25 mol/l sucrose with 0.5 mol/l Sorensen's buffer and 2% osmium tetroxide. They were subsequently dehydrated in graded ethanol solutions and embedded using the Embed 812 kit (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA).

Subcutaneous tumorigenicity assay. NHK, Krdeb, and Kcol7 were harvested when in log-phase growth. 2.106 cells, resuspended in 50 µl of phosphate-buffered saline, were injected subcutaneously (using a 21-gauge needle) into 6-week-old nude mice. Two mice received HeLa cells, three mice received NHK, five mice received Krdeb, and five mice received Kcol7. Mice were monitored daily during the first 2 weeks, and then twice a week. Tumor volumes were measured twice a week using the formula 4/3πr3. Half of the tumors was plated into a culture dish, and the other half was fixed in 10% formalin for histological and immunohistological analysis.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Figure S1. SIN vectors design. Figure S2. Northern blot analysis of viral supernatants. Figure S3. Analysis of the regulation of recombinant type VII collagen expression. Figure S4. Correction of either cell layer is sufficient to restore the demal-epidermal adherence. Table S1. Summary of the vector production data. Table S2. Average copy number of the integrated COL7A1 provirus. Table S3. Summary of the rearrangement events detected at the protein and DNA levels. Table S4. Number of animals for each cell type subcutaneously injected. Table S5. Clinical status and histological analyses of grafted SCID mice. Table S6. Oligonucleotide primers sequences used for molecular cloning, PCR and real-time PCR.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patient and his family for their collaboration, Valerie Walshe for the cloning of the full-length COL7A1 cDNA and Philippe Bourin (EFS Midi-Pyrénées) for the gift of human plasma. They gratefully acknowledge Talal Al Saati and Florence Capilla from the experimental histopathology platform of IFR150 (IFR150, plateau d'histopathologie expérimentale de Purpan Toulouse, France), Isabelle Fourquaux from the electron microscopy platform (CMEAB, IFR150, Toulouse, France), as well as the animal facility staff (INSERM, IFR150, Toulouse, France) for their technical assistance. This work was supported by INSERM and by grants from the British Dystrophic EB Research Association (DEBRA-UK), Epidermolyse Bulleuse Association d'Entraide (EBAE), Association Française contre les Myopathies (AFM), Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (FRM), Midi-Pyrénées Region and the European Union Therapeuskin project (contract LSHB-CT-2005-511974). The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

SIN vectors design.

Northern blot analysis of viral supernatants.

Analysis of the regulation of recombinant type VII collagen expression.

Correction of either cell layer is sufficient to restore the demal-epidermal adherence.

Summary of the vector production data.

Average copy number of the integrated COL7A1 provirus.

Summary of the rearrangement events detected at the protein and DNA levels.

Number of animals for each cell type subcutaneously injected.

Clinical status and histological analyses of grafted SCID mice.

Oligonucleotide primers sequences used for molecular cloning, PCR and real-time PCR.

REFERENCES

- Varki R, Sadowski S, Uitto J., and, Pfendner E. Epidermolysis bullosa. II. Type VII collagen mutations and phenotype-genotype correlations in the dystrophic subtypes. J Med Genet. 2007;44:181–192. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.045302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavilio F, Pellegrini G, Ferrari S, Di Nunzio F, Di Iorio E, Recchia A, et al. Correction of junctional epidermolysis bullosa by transplantation of genetically modified epidermal stem cells. Nat Med. 2006;12:1397–1402. doi: 10.1038/nm1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Urda S, Lin Q, Green CL, Keene DR, Marinkovich MP., and, Khavari PA. Injection of genetically engineered fibroblasts corrects regenerated human epidermolysis bullosa skin tissue. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:251–255. doi: 10.1172/JCI17193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Urda S, Thyagarajan B, Keene DR, Lin Q, Fang M, Calos MP, et al. Stable nonviral genetic correction of inherited human skin disease. Nat Med. 2002;8:1166–1170. doi: 10.1038/nm766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodley DT, Krueger GG, Jorgensen CM, Fairley JA, Atha T, Huang Y, et al. Normal and gene-corrected dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa fibroblasts alone can produce type VII collagen at the basement membrane zone. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:1021–1028. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodley DT, Keene DR, Atha T, Huang Y, Ram R, Kasahara N, et al. Intradermal injection of lentiviral vectors corrects regenerated human dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa skin tissue in vivo. Mol Ther. 2004;10:318–326. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Kasahara N, Keene DR, Chan L, Hoeffler WK, Finlay D, et al. Restoration of type VII collagen expression and function in dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Nat Genet. 2002;32:670–675. doi: 10.1038/ng1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gache Y, Baldeschi C, Del Rio M, Gagnoux-Palacios L, Larcher F, Lacour JP, et al. Construction of skin equivalents for gene therapy of recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Hum Gene Ther. 2004;15:921–933. doi: 10.1089/hum.2004.15.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Von Kalle C, Schmidt M, McCormack MP, Wulffraat N, Leboulch P, et al. LMO2-associated clonal T cell proliferation in two patients after gene therapy for SCID-X1. Science. 2003;302:415–419. doi: 10.1126/science.1088547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazo PA, Lee JS., and, Tsichlis PN. Long-distance activation of the Myc protooncogene by provirus insertion in Mlvi-1 or Mlvi-4 in rat T-cell lymphomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:170–173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.1.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zychlinski D, Schambach A, Modlich U, Maetzig T, Meyer J, Grassman E, et al. Physiological promoters reduce the genotoxic risk of integrating gene vectors. Mol Ther. 2008;16:718–725. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods NB, Bottero V, Schmidt M, von Kalle C., and, Verma IM. Gene therapy: therapeutic gene causing lymphoma. Nature. 2006;440:1123. doi: 10.1038/4401123a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber EL., and, Cannon PM. Promoter choice for retroviral vectors: transcriptional strength versus trans-activation potential. Hum Gene Ther. 2007;18:849–860. doi: 10.1089/hum.2007.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grez M, Akgün E, Hilberg F., and, Ostertag W. Embryonic stem cell virus, a recombinant murine retrovirus with expression in embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:9202–9206. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.23.9202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacein-Bey-Abina S, von Kalle C, Schmidt M, Le Deist F, Wulffraat N, McIntyre E, et al. A serious adverse event after successful gene therapy for X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:255–256. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200301163480314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willemsen RA, Weijtens ME, Ronteltap C, Eshhar Z, Gratama JW, Chames P, et al. Grafting primary human T lymphocytes with cancer-specific chimeric single chain and two chain TCR. Gene Ther. 2000;7:1369–1377. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pendaries V, Verrecchia F, Michel S., and, Mauviel A. Retinoic acid receptors interfere with the TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway in a ligand-specific manner. Oncogene. 2003;22:8212–8220. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verrecchia F, Vindevoghel L, Lechleider RJ, Uitto J, Roberts AB., and, Mauviel A. Smad3/AP-1 interactions control transcriptional responses to TGF-β in a promoter-specific manner. Oncogene. 2001;20:3332–3340. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon P, Kindler V, Ducrey O, Chapuis B, Zubler RH., and, Trono D. High-level transgene expression in human hematopoietic progenitors and differentiated blood lineages after transduction with improved lentiviral vectors. Blood. 2000;96:3392–3398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schucht R, Coroadinha AS, Zanta-Boussif MA, Verhoeyen E, Carrondo MJ, Hauser H, et al. A new generation of retroviral producer cells: predictable and stable virus production by Flp-mediated site-specific integration of retroviral vectors. Mol Ther. 2006;14:285–292. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loew R, Meyer Y, Kuehlcke K, Gama-Norton L, Wirth D, Hauser H, et al. A new PG13-based packaging cell line for stable production of clinical-grade self-inactivating gamma-retroviral vectors using targeted integration. Gene Ther. 2010;17:272–280. doi: 10.1038/gt.2009.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiano AM, Amano S, Eichenfield LF, Burgeson RE., and, Uitto J. Premature termination codon mutations in the type VII collagen gene in recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa result in nonsense-mediated mRNA decay and absence of functional protein. J Invest Dermatol. 1997;109:390–394. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12336276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrandon Y., and, Green H. Three clonal types of keratinocyte with different capacities for multiplication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:2302–2306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.8.2302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Costa FK, Lindvay CR, Han YP., and, Woodley DT. The recombinant expression of full-length type VII collagen and characterization of molecular mechanisms underlying dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:2118–2124. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108779200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris NP, Keene DR, Glanville RW, Bentz H., and, Burgeson RE. The tissue form of type VII collagen is an antiparallel dimer. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:5638–5644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruckner P., and, Prockop DJ. Proteolytic enzymes as probes for the triple-helical conformation of procollagen. Anal Biochem. 1981;110:360–368. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(81)90204-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YH, Woodley DT, Wynn KC, Giomi W., and, Bauer EA. Recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa phenotype is preserved in xenografts using SCID mice: development of an experimental in vivo model. J Invest Dermatol. 1992;98:191–197. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12555849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pendaries V, Gasc G, Titeux M, Leroux C, Vitezica ZG, Mejía JE, et al. 2010Immune reactivity to type VII collagen: implications for gene therapy of recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa Gene Therepub ahead of print). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cornils K, Lange C, Schambach A, Brugman MH, Nowak R, Lioznov M, et al. Stem cell marking with promotor-deprived self-inactivating retroviral vectors does not lead to induced clonal imbalance. Mol Ther. 2009;17:131–143. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruggi G, Porcellini S, Facchini G, Perna SK, Cattoglio C, Sartori D, et al. Transcriptional enhancers induce insertional gene deregulation independently from the vector type and design. Mol Ther. 2009;17:851–856. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montini E, Cesana D, Schmidt M, Sanvito F, Bartholomae CC, Ranzani M, et al. The genotoxic potential of retroviral vectors is strongly modulated by vector design and integration site selection in a mouse model of HSC gene therapy. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:964–975. doi: 10.1172/JCI37630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onafuwa A, An W, Robson ND., and, Telesnitsky A. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genetic recombination is more frequent than that of Moloney murine leukemia virus despite similar template switching rates. J Virol. 2003;77:4577–4587. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.8.4577-4587.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zennou V, Petit C, Guetard D, Nerhbass U, Montagnier L., and, Charneau P. HIV-1 genome nuclear import is mediated by a central DNA flap. Cell. 2000;101:173–185. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80828-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dull T, Zufferey R, Kelly M, Mandel RJ, Nguyen M, Trono D, et al. A third-generation lentivirus vector with a conditional packaging system. J Virol. 1998;72:8463–8471. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.8463-8471.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Li Y, Crise B., and, Burgess SM. Transcription start regions in the human genome are favored targets for MLV integration. Science. 2003;300:1749–1751. doi: 10.1126/science.1083413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinski MK, Yamashita M, Emerman M, Ciuffi A, Marshall H, Crawford G, et al. Retroviral DNA integration: viral and cellular determinants of target-site selection. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e60. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell RS, Beitzel BF, Schroder AR, Shinn P, Chen H, Berry CC, et al. Retroviral DNA integration: ASLV, HIV, and MLV show distinct target site preferences. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:E234. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushman F, Lewinski M, Ciuffi A, Barr S, Leipzig J, Hannenhalli S, et al. Genome-wide analysis of retroviral DNA integration. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:848–858. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Carranza B, Gentsch M, Stein S, Schambach A, Santilli G, Rudolf E, et al. Transgene optimization significantly improves SIN vector titers, gp91phox expression and reconstitution of superoxide production in X-CGD cells. Gene Ther. 2009;16:111–118. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llames SG, Del Rio M, Larcher F, García E, García M, Escamez MJ, et al. Human plasma as a dermal scaffold for the generation of a completely autologous bioengineered skin. Transplantation. 2004;77:350–355. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000112381.80964.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu SS, Kim JM., and, Kim S. High efficiency retroviral vectors that contain no viral coding sequences. Gene Ther. 2000;7:797–804. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zufferey R, Nagy D, Mandel RJ, Naldini L., and, Trono D. Multiply attenuated lentiviral vector achieves efficient gene delivery in vivo. Nat Biotechnol. 1997;15:871–875. doi: 10.1038/nbt0997-871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrandon Y., and, Green H. Cell migration is essential for sustained growth of keratinocyte colonies: the roles of transforming growth factor-alpha and epidermal growth factor. Cell. 1987;50:1131–1137. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90179-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochat A, Kobayashi K., and, Barrandon Y. Location of stem cells of human hair follicles by clonal analysis. Cell. 1994;76:1063–1073. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90383-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mecklenbeck S, Compton SH, Mejía JE, Cervini R, Hovnanian A, Bruckner-Tuderman L, et al. A microinjected COL7A1-PAC vector restores synthesis of intact procollagen VII in a dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa keratinocyte cell line. Hum Gene Ther. 2002;13:1655–1662. doi: 10.1089/10430340260201743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

SIN vectors design.

Northern blot analysis of viral supernatants.

Analysis of the regulation of recombinant type VII collagen expression.

Correction of either cell layer is sufficient to restore the demal-epidermal adherence.

Summary of the vector production data.

Average copy number of the integrated COL7A1 provirus.

Summary of the rearrangement events detected at the protein and DNA levels.

Number of animals for each cell type subcutaneously injected.

Clinical status and histological analyses of grafted SCID mice.

Oligonucleotide primers sequences used for molecular cloning, PCR and real-time PCR.