Abstract

Extensive studies over the years have shown that the AMP-activated kinase (AMPK) exhibits negative regulatory effects on the activation of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling cascade. We examined the potential involvement of AMPK in the regulation of growth and survival of malignant melanoma cells. In studies using the AMPK activators AICAR or metformin, we found potent inhibitory effects of AMPK activity on the growth of SK-MEL-2 and SK-MEL-28 malignant melanoma cells. Induction of AMPK activity was also associated with inhibition of the ability of melanoma cells to form colonies in an anchorage-independent manner in soft agar, suggesting an important role of the pathway in the control of malignant melanoma tumorigenesis. Furthermore, AICAR-treatment resulted in malignant melanoma cell death and such induction of apoptosis was further enhanced by concomitant statin-treatment. Taken together, our results provide evidence for potent inhibitory effects of AMPK on malignant melanoma cell growth and survival and raise the potential of AMPK manipulation as a novel future approach for the treatment of malignant melanoma.

Keywords: AMP-activated kinase (AMPK), malignant melanoma, 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide riboside (AICAR), metformin

Introduction

There has been accumulating evidence linking cancer cell growth and cellular metabolism, underscoring the possible therapeutic potential of targeting metabolic proteins with ties to cellular pathways that are abnormally activated in some cancers. One such metabolic protein is AMP-activated kinase (AMPK)-a protein that detects changes to cellular energy levels following binding of AMP to its gamma domain [1; 2]. Activation of AMPK is induced after phosphorylation/activation of threonine 172 in the AMPK structure by upstream kinases, subsequently resulting in engagement of downstream AMPK-dependent cellular events [1; 2]. Aside from its ties to energy balance and metabolism, AMPK is known for its link to a major cellular survival pathway, the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-K) pathway [3; 4]. AMPK activation results in inhibition of activation of the protein mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), a key downstream component of the PI3-K pathway [5; 6]. This results in inhibition of mRNA translation/protein translation, a highly consuming energy process, to maintain cellular energy balance. Therefore, AMPK’s position in both the metabolic pathway as well as its position upstream of the mTOR signaling cascade make it a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of certain cancers, especially as changes to the ATP:AMP ratio [7] are a key characteristic of malignant cells. One activator of AMPK with possible anti-cancer properties is 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide riboside (AICAR), an agent that acts like an AMP mimic and binds AMPK resulting in its activation [8].

Malignant melanoma is a highly fatal solid tumor, with an overall ten- year survival rate of less than ten percent [9]. There has been some evidence that melanoma is associated with constitutive activation of the PI3-K/Akt/mTOR signaling cascade [10], Nevertheless, the relevance of targeting such mTOR activation in the treatment of melanoma remains to be established; while the importance of other signaling pathways that regulate mTOR in melanoma growth and survival has not been exploited so far. In the present study we examined the effects of targeting of AMPK in malignant melanoma cells. Treatment of two different malignant melanoma lines with AMPK activators [11], resulted in dose-dependent suppression on melanoma cell proliferation and/or induction of apoptosis, establishing a critical role for AMPK activity in the control of survival of melanoma cells. Importantly, soft agar colony formation assays demonstrated potent suppressive effects of AICAR on melanoma anchorage-independent cell growth, suggesting an important role for AMPK activity in the control of tumorigenesis in malignant melanoma. In addition, concomitant engagement of AMPK activity and treatment of cells with statins, which based on our previous work can act as dual mTORC1/2 inhibitors [12], resulted in enhanced pro-apoptotic effects. Altogether our data provide, for the first time, evidence for a key role of AMPK-generated signals in malignant melanoma cell growth and survival; and suggest that activators of AMPK may be of future potential therapeutic value in the management of this malignancy.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines and reagents

The SK-MEL-2 and SK-MEL-28 malignant melanoma cell lines were grown in Minimal Essential Medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics. 5-Aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide (AICAR) and metformin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Fluvastatin was provided by Novartis. Simvastatin was purchased from Calbiochem.

Cell proliferation assays

Cells were seeded in 96-well plates and incubated in the presence of solvent control or the indicated concentrations of either AICAR or metformin at 37°C for 4 days. Cell proliferation was assessed by methyl-thiazolyl-tetrazolium assays, as in our previous studies [13].

Flow cytometric analysis

Flow cytometric studies to detect apoptosis by annexin V/propidium iodide staining were done as in our previous studies [13; 14].

Soft-agar assays

Anchorage-independent growth was assessed in a soft-agar assay system, as in our previous studies [15].

Results

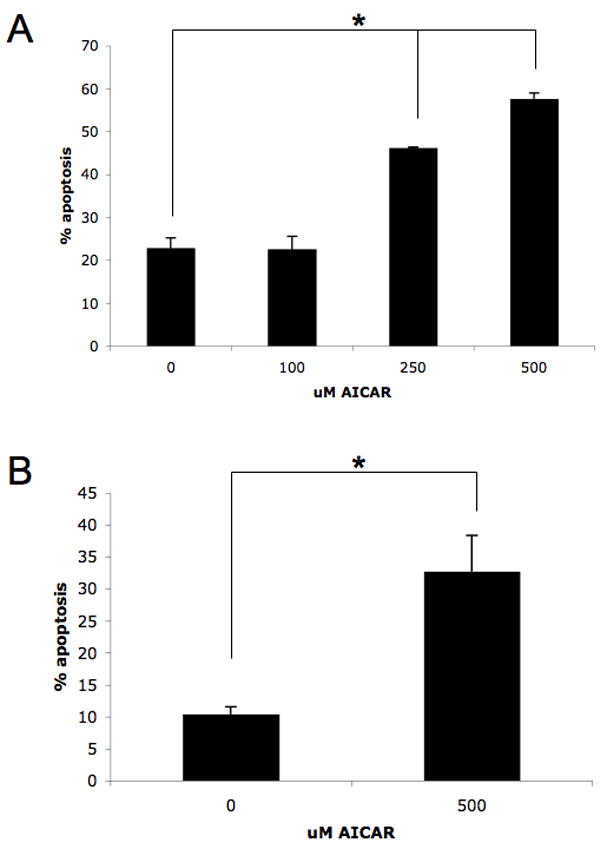

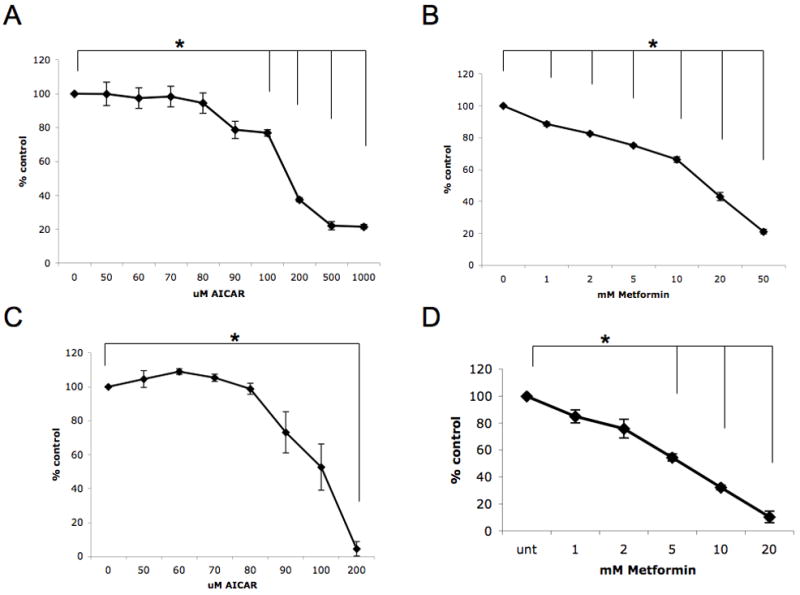

To define the functional consequences of AMPK targeting in melanoma cells, we initially analyzed the effects of the AMPK activator AICAR on survival of different malignant melanoma cell lines. For this purpose, induction of apoptosis was assessed by annexin/PI staining. AICAR-treatment resulted in significant induction of melanoma cell death of both SK-MEL-2 and SK-MEL-28 cells, with approximately 55 to 60 percent of SK-MEL-2 cells and 30 to 35 percent of SK-MEL-28 cells undergoing apoptosis at AICAR concentrations of 500 μM (Fig. 1A, B). The effects of AICAR and another AMPK activator, metformin [11], on melanoma cell proliferation were examined next. SK-MEL-2 cells were treated with increasing doses of AICAR (Fig. 2A) or metformin (Fig. 2B) and cell growth assessed by MTT assays. Similarly, the cellular proliferation of SK-MEL-28 cells in the presence of increasing concentrations of either AICAR or metformin were analyzed (Fig. 2C, D). AICAR significantly inhibited melanoma cell growth in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2A and C). Similarly, metformin suppressed the cell growth of both melanoma cell lines in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2B and D). Thus, targeting of AMPK using specific activators results in growth suppression and induction of apoptosis of malignant melanoma cells.

Figure 1. Induction of pro-apoptotic effects by AMPK activators in malignant melanoma cells.

A–B. SK-MEL-2 (A) or SK-MEL-28 (B) cells were incubated in the presence or absence of AICAR at the indicated concentrations for 96 hours. The induction of apoptosis was evaluated by flow cytometry using annexin V/propidium iodide staining. Data are expressed as percent apoptotic cells. Means + SE of three (A) or four (B) independent experiments for SK-MEL-2 or SK-MEL-28 cells, respectively, are shown. Paired t test analysis for the induction of apoptosis of SK-MEL-2 cells treated for 96 h with 250 μmol/L or 500 μmol/L versus control-treated cells showed two-tailed p values of 0.009 and 0.008, respectively. Paired t test analysis for the induction of apoptosis of SK-MEL-28 cells treated for 96 h versus control-treated cells showed a two-tailed p = 0.046.

Figure 2. Inhibitory effects of AMPK activators on malignant melanoma cell growth.

A. SK-MEL-2 cells were treated for 4 days with solvent control or with the indicated concentrations of AICAR. Data are expressed as % control-treated cells and represent means + SE of 3 independent experiments. Paired t test analysis for the growth of SK-MEL-2 cells treated with 100 μmol/L AICAR, 200 μmol/L AICAR, 500 μmol/L AICAR, or 1000 μmol/L AICAR versus control-treated cells showed 2-tailed p values of 0.007, 0.0004, 0.001, and 0.0003, respectively. B. SK-MEL-2 cells were treated for 4 days with solvent control or with the indicated concentrations of metformin. Data are expressed as % control-treated cells and represent means + SE of 3 independent experiments. Paired t test analysis for the growth of SK-MEL-2 cells treated with 1 mmol/L metformin, 2 mmol/L metformin, 5 mmol/L metformin, 10 mmol/L metformin, 20 mmol/L metformin, or 50 mmol/L metformin versus control-treated cells showed 2-tailed p values of 0.012, 0.003, 0.001, 0.003, 0.002, and 0.0003, respectively. C. SK-MEL-28 cells were treated for 4 days with solvent control or with the indicated concentrations of AICAR. Data are expressed as % control-treated cells and represent means + SE of 3 independent experiments. Paired t test analysis for the growth of SK-MEL-28 cells treated with 200 μmol/L AICAR versus control-treated cells showed a 2-tailed p value = 0.002. D. SK-MEL-28 cells were treated for 4 days with solvent control or with the indicated concentrations of metformin. Data are expressed as % control-treated cells and represent means + SE of 3 independent experiments. Paired t test analysis for the growth of SK-MEL-28 cells treated with 5 mmol/L metformin, 10 mmol/L metformin, or 20 mmol/L metformin versus control-treated cells showed 2-tailed p values of 0.003, 0.0006, and 0.002, respectively.

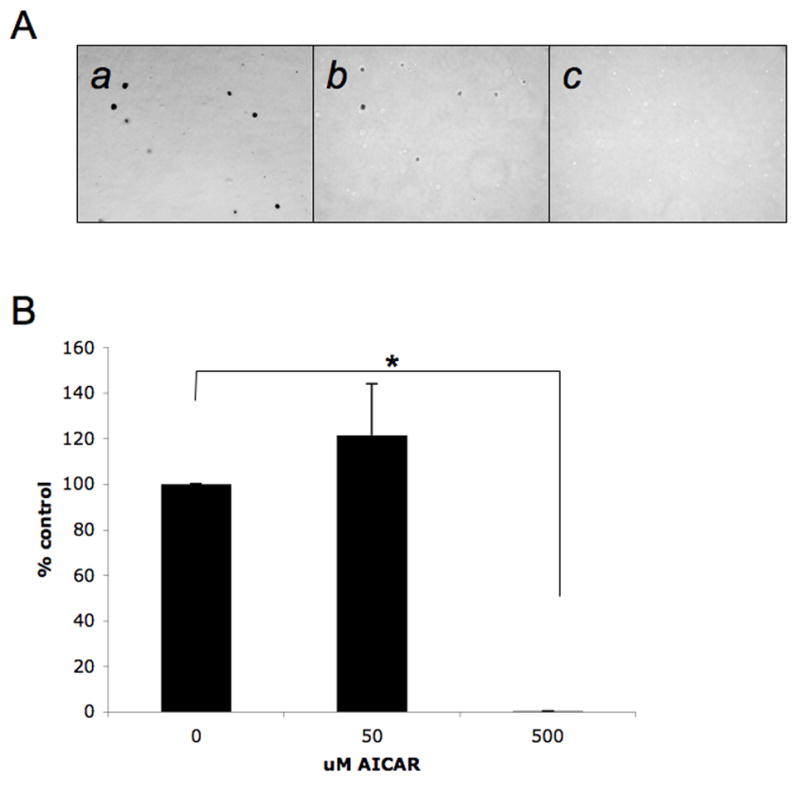

In subsequent work, the effects of AMPK activation on tumorigenicity of melanoma cells were examined by assessing the consequences of AMPK activation on anchorage-independent melanoma cell growth. SK-MEL-28 cells were plated in soft agar, in the presence or absence of different concentrations of AICAR (50 μmol/L or 500 μmol/L) and colonies were scored after 14 days. As shown in Fig. 3, anchorage-independent growth of melanoma cells was sensitive to AICAR, with significant inhibition of colony formation detected at 500 μmol/L AICAR (Fig. 3), establishing a critical negative regulatory role for AMPK in anchorage-independent melanoma cell growth.

Figure 3. Inhibitory effect of AICAR on melanoma cell anchorage-independent growth.

A. Equal numbers of SK-MEL-28 cells were plated in a soft-agar assay system and treated with solvent control or AICAR (50 μmol/L or 500 μmol/L). Colony formation was analyzed after 14 days of culture. A representative area (20 x magnification) of each treatment point is shown (a–c). Cells were treated with solvent control (DMSO) (a), 50 μmol/L AICAR (b), or 500 μmol/L AICAR (c). Colonies were stained with crystal violet. B. Colonies were counted and results were expressed as % of solvent control-treated colonies. Data shown represent means + SE of 3 independent experiments. Paired t test analysis for the growth of SK-MEL-28 colonies treated with 500 μmol/L AICAR versus control-treated cells showed a 2-tailed p value = 2.56×10−7.

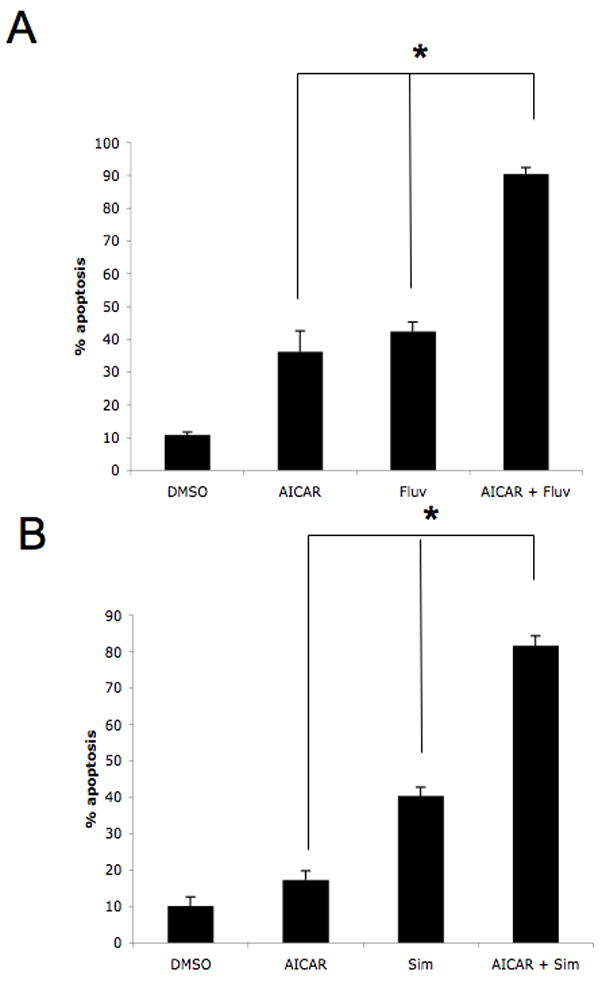

Prior work from others has demonstrated that 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibitors (statins) have anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic effects against melanoma cells [16], while work from our lab has further shown that the their suppressive effects on the AKT/mTOR pathway play key roles in the generation of the suppressive effects of statins on renal cell carcinoma cells [12]. Since AMPK activation is critically linked to control of mTOR activity and AICAR is known to exert inhibitory effects on AKT pathway activation [5; 6; 17; 18], we examined the effects of combinations of AICAR and statins on malignant melanoma cell death. Concomitant treatment of SK-MEL-28 cells with fluvastatin and AICAR resulted in greater levels of apoptosis than each agent alone (Fig. 4A). Similar results were obtained when a different statin, simvastatin, was combined with AICAR (Fig. 4B). Thus, statins enhance the anti-melanoma effects of AMPK activation, suggesting that combinations of these agents with AMPK activators may provide a novel approach for the treatment of malignant melanoma.

Figure 4. Enhanced pro-apoptotic responses in malignant melanoma cells by combinations of AICAR with statins.

A. SK-MEL-28 cells were treated with solvent control, AICAR (500 μmol/L), fluvastatin (3 μmol/L), or the indicated combinations for ninety-six hours. Data are expressed as % apoptotic cells and represent means + SE of 3 independent experiments. Paired t test analysis for the induction of apoptosis of SK-MEL-28 cells treated with AICAR versus fluvastatin and AICAR showed a 2-tailed p value = 0.022. Paired t test analysis for the induction of apoptosis of SK-MEL-28 cells treated with fluvastatin versus fluvastatin and AICAR showed a 2-tailed p value = 0.006. B. SK-MEL-28 cells were treated with solvent control, AICAR (500 μmol/L), simvastatin (3 μmol/L), or the indicated combinations for ninety-six hours. Data are expressed as % apoptotic cells and represent means + SE of 3 independent experiments. Paired t test analysis for the induction of apoptosis of SK-MEL-28 cells treated with AICAR versus simvastatin and AICAR showed a 2-tailed p value = 0.006. Paired t test analysis for the induction of apoptosis of SK-MEL-28 cells treated with simvastatin versus simvastatin and AICAR showed a 2-tailed p value = 0.0007.

Discussion

Malignant melanoma is a highly fatal malignancy with limited therapeutic options. Defining the importance of various pro-growth and pro-apoptotic pathways in malignant melanoma is highly relevant, as it may provide the basis for the ultimate development of novel specific therapeutic approaches. There is accumulating evidence that under certain circumstances AMPK plays key negative regulatory roles in the control of cellular proliferation, including the growth of certain malignant cell types, such as leukemia cells, as well as prostate and colon carcinoma cells [19; 20; 21]. Consistent with this concept, inactivation of AMPK by overexpression of dominant-negative mutants or shRNA-mediated disruption of its expression results in enhanced growth of prostate carcinoma cells, underscoring the importance of AMPK in the control of prostate tumorigenesis [22].

The potential regulatory effects of AMPK on malignant melanoma growth and the antitumor potential of AMPK activators on melanoma cells have been unknown. In the present work we provide direct evidence for potent inhibitory effects of AMPK on malignant melanoma cell survival and proliferation. Our studies demonstrate that AICAR induces apoptosis and suppresses the growth of the SK-MEL-2 cells in a dose dependent manner. Similar AICAR-dependent pro-apoptotic and antiproliferative responses were found when SK-MEL-28 cells were studied. Importantly, functional analysis further revealed a potent inhibitory effect of AICAR on anchorage-independent growth of melanoma cells providing evidence for a critical role of AMPK in the control of malignant melanoma tumorigenesis. Altogether, our findings provide direct evidence for a key role of AMPK as a negative regulator and suppressor of malignant melanoma cell growth and suggest that detailed characterization of upstream and downstream regulatory events that control engagement of this pathway may lead to the identification of additional therapeutic targets in melanoma cells.

Previous work has demonstrated that the kinase LKB1 is an upstream regulator of AMPK [23]. As AICAR, acting like a cellular AMP mimic, binds AMPK, the corresponding conformational change of AMPK allows upstream kinases such as LKB1 to then fully activate AMPK at its active site [24]. Interestingly, recent work has demonstrated that LKB1 is phosphorylated by ERK and RSK in malignant melanoma cells that express the B-RAF V600E mutation [25], and that such phosphorylation results in inhibitory effects on the ability of LKB1 to activate AMPK [25]. These findings have provided evidence for an important mechanism by which AMPK is negatively regulated in the presence of B-RAF V600E mutation and have suggested that inhibitory effects on the LKB1/AMPK axis in melanoma by this mutation may constitute an important mechanism of tumorigenesis [25]. It should be noted that mutations of the protein kinase B-RAF occur in approximately 50 to 70 percent of malignant melanomas [26], but a large percentage of malignant melanomas do not express this mutations. Our studies using both a melanoma cell line harboring this B-RAF mutation (SK-MEL-28) [27] as well as a melanoma cell line without this mutation (SK-MEL-2) [27], suggest a role of AMPK in the control of malignant melanoma cell growth, as shown by the induction of potent anti-proliferative effects of AICAR or metformin on these cells. It should be noted, that consistent with previous work [25], we have not been able to detect phosphorylation of AMPK by AICAR in SK-MEL-28 cells. However, the ability of AICAR to induce suppressive effects on these cells suggests either an alternative mechanism by which AMPK may be engaged under these circumstances and/or additional cellular effects of AMPK activators, distinct from AMPK activity, in malignant melanoma cells and this remains to be addressed in future studies.

Independently of the precise mechanism involved, our finding that combinations of statins and AICAR result in enhanced antimelanoma effects is of particular interest and may have important translational implications. Previous studies have shown that lovastatin, mevastatin, and simvastatin inhibit cell growth, cell migration, and invasion of melanoma cell lines [16], while another study determined that simvastatin inhibits malignant melanoma cell cycle progression [28]. Our findings, for the first time, provide evidence that statins enhance the pro-apoptotic effects of AICAR, raising the possibility that combinations of statins with AMPK activators may be an approach to promote responses in melanoma cells in vitro and in vivo. Future work in that direction should help us better understand unique mechanisms that promote growth and survival of melanoma cells and, possibly, lead to translational clinical efforts involving combinations of AMPK inducers with statins for the treatment of malignant melanoma.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants R01CA121192, R01CA77816, T32CA009560 and by a Merit Review grant from the Department of Veterans Affairs.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants CA121192, CA77816, and by a grant from the Department of Veterans Affairs (to LCP). JW was supported by a NIH training grant T32CA009560.

Abbreviations

- AICAR

5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide riboside

- AMPK

AMP-activated kinase

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- PI3-K

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hardie DG. The AMP-activated protein kinase pathway--new players upstream and downstream. J of Cell Sci. 2004;117(Pt 23):5479–5487. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hardie DG, Hawley SA. AMP-activated protein kinase: the energy charge hypothesis revisited. Bioessays. 2001;23:1112–1129. doi: 10.1002/bies.10009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hay N. The Akt-mTOR tango and its relevance to cancer. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:179–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhaskar PT, Hay N. The two TORCs and Akt. Dev Cell. 2007;12:487–502. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gwinn DM, Shackelford DB, Egan DF, et al. AMPK phosphorylation of raptor mediates a metabolic checkpoint. Mol Cell. 2008;30:214–226. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hardie DG. AMPK and Raptor: matching cell growth to energy supply. Mol Cell. 2008;30:263–265. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swinnen JV, Beckers A, Brusselmans K, et al. Mimicry of a cellular low energy status blocks tumor cell anabolism and suppresses the malignant phenotype. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2441–2448. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corton JM, Gillespie JG, Hawley SA, et al. 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleoside. A specific method for activating AMP-activated protein kinase in intact cells? Eur J of Bio/FEBS. 1995;229:558–565. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhatia S, Tykodi SS, Thompson JA. Treatment of metastatic melanoma: an overview. Oncology. 2009;23:488–496. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sinnberg T, Lasithiotakis K, Niessner H, et al. Inhibition of PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling sensitizes melanoma cells to cisplatin and temozolomide. J of Invest Derm. 2009;129:1500–1515. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou G, Myers R, Li Y, et al. Role of AMP-activated protein kinase in mechanism of metformin action. J of Clin Invest. 2001;108:1167–1174. doi: 10.1172/JCI13505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woodard J, Sassano A, Hay N, Platanias LC. Statin-dependent suppression of the Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin signaling cascade and programmed cell death 4 up-regulation in renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4640–4649. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giafis N, Katsoulidis E, Sassano A, et al. Role of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in the generation of arsenic trioxide-dependent cellular responses. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6763–6771. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sassano A, Katsoulidis E, Antico G, et al. Suppressive effects of statins on acute promyelocytic leukemia cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:4524–4532. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katsoulidis E, Carayol N, Woodard J, et al. Role of Schlafen 2 (SLFN2) in the generation of IFN{alpha}-induced growth inhibitory responses. J Bio Chem. 2009;284:25051–25064. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.030445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glynn SA, O’Sullivan D, Eustace AJ, et al. The 3-hydroxy-3- methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibitors, simvastatin, lovastatin and mevastatin inhibit proliferation and invasion of melanoma cells. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rattan R, Giri S, Singh AK, Singh I. 5-Aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-beta-D-ribofuranoside inhibits cancer cell proliferation in vitro and in vivo via AMP-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:39582–39593. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507443200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hahn-Windgassen A, Nogueira V, Chen CC, et al. Akt activates the mammalian target of rapamycin by regulating cellular ATP level and AMPK activity. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:32081–32089. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502876200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sengupta TK, Leclerc GM, Hsieh-Kinser TT, et al. Cytotoxic effect of 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-beta-4-ribofuranoside (AICAR) on childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) cells: implication for targeted therapy. Mol Cancer. 2007;6:46. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-6-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiang X, Saha AK, Wen R, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase activators can inhibit the growth of prostate cancer cells by multiple mechanisms. Bio Biophys Res Comm. 2004;321:161–167. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.06.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Su RY, Chao Y, Chen TY, et al. 5-Aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide riboside sensitizes TRAIL- and TNF{alpha}-induced cytotoxicity in colon cancer cells through AMP-activated protein kinase signaling. Mol Cancer Therap. 2007;6:1562–1571. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou J, Huang W, Tao R, et al. Inactivation of AMPK alters gene expression and promotes growth of prostate cancer cells. Oncogene. 2009;28:1993–2002. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shaw RJ, Kosmatka M, Bardeesy N, et al. The tumor suppressor LKB1 kinase directly activates AMP-activated kinase and regulates apoptosis in response to energy stress. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:3329–3335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308061100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hardie DG. Minireview: the AMP-activated protein kinase cascade: the key sensor of cellular energy status. Endo. 2003;144:5179–5183. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng B, Jeong JH, Asara JM, Yuan YY, Granter SR, Chin L, Cantley LC. Oncogenic B-RAF negatively regulates the tumor suppressor LKB1 to promote melanoma cell proliferation. Mol Cell. 2009;33:237–247. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dhomen N, Marais R. New insight into BRAF mutations in cancer. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2007;17:31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grbovic OM, Basso AD, Sawai A, et al. V600E B-Raf requires the Hsp90 chaperone for stability and is degraded in response to Hsp90 inhibitors. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:57–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609973103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saito A, Saito N, Mol W, et al. Simvastatin inhibits growth via apoptosis and the induction of cell cycle arrest in human melanoma cells. Mel Res. 2008;18:85–94. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e3282f60097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]