Abstract

Protein thiocarboxylates are involved in the biosynthesis of thiamin, molybdopterin, thioquinolobactin, and cysteine. Sequence analysis suggests that this posttranslational modification is widely distributed in bacteria. Here we describe the development of lissamine rhodamine B sulfonyl azide as a sensitive click reagent for the detection of protein thiocarboxylates and describe the use of this reagent to detect PdtH, a putative protein thiocarboxylate involved in the biosynthesis of the pyridine dithiocarboxylic acid siderophore, in the Pseudomonas stutzeri proteome.

Keywords: Protein thiocarboxylate, Click reaction, detection, biosynthesis, thiamin, molybdopterin, thioquinolobactin, cysteine

1 Introduction

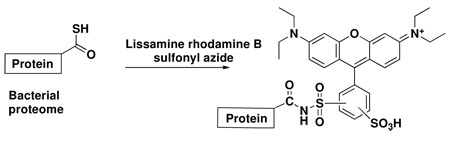

Protein thiocarboxylates function as sulfide donors in the biosynthesis of thiamin1, molybdopterin2, thioquinolobactin3, cysteine4, and eukaryotic transfer RNA (tRNA) modification5 (Figure 1). These proteins are characterized by their small size (<100 amino acids), by the presence of a flexible GlyGly sequence at the thiocarboxylate containing carboxy terminus, and by a β-grasp structure. Sequence analysis, using the biochemically characterized protein thiocarboxylates ThiS, MoaD, QbsE and CysO in the Pfam database (http://pfam.sanger.ac.uk/) suggests that ThiS-like proteins are widely distributed and may play a role in several additional biosynthetic pathways. Therefore, a reagent to selectively detect protein thiocarboxylates, in any bacterial proteome, would be of use in identifying systems for further biochemical characterization.

Figure 1.

Thiocarboxylate-containing proteins in biosynthetic pathways. The functions of ThiS, MoaD, QbsE, Urm1p and CysO have been biochemically characterized. The function of PdtH is a proposed function based on sequence analysis.

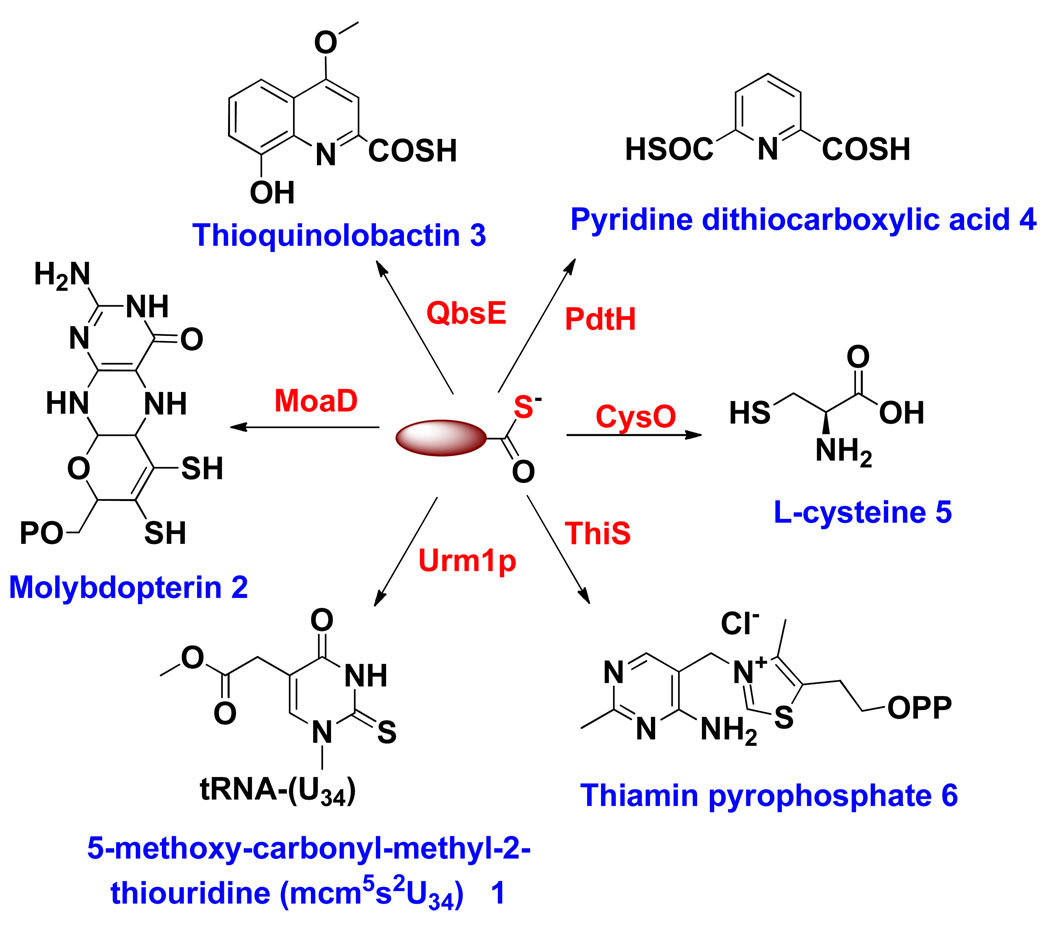

Selective protein thiocarboxylate labeling in proteomes is a challenging problem because the thiocarboxylate functional group is present at low concentrations in an environment containing many other nucleophiles. After surveying various possibilities, we decided to explore the “click reaction” between thiocarboxylates and electron-deficient sulfonyl azides to form N-acyl-sulfonamides as our labeling strategy.6,7,8 Recently, this reaction was used to label purified ubiquitin thiocarboxylate with PEG-sulfonyl azide and biotin-sulfonyl azide suggesting that the reaction has the needed selectivity for a proteomics study9. Here we describe the development of a simple, fast and sensitive fluorescence-based method to detect new thiocarboxylate-containing proteins. The method utilizes lissamine rhodamine B sulfonyl azi de (LRSA) as the fluorescent label and has been applied to tag pure over-expressed protein thiocarboxylates as well as protein thiocarboxylates in a bacterial proteome (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Protein thiocarboxylate labeling using a “click reaction” with lissamine rhodamine B sulfonyl azide.

Materials and methods

Lissamine rhodamine B sulfonyl chloride, EDTA, dithiothreitol (DTT), potassium phosphate, ferrous ammonium sulphate, β-mercaptoethanol and sterile disposable polyethylene terephthalate G copolymer (PETG) flasks, with vented closure, were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Fairlawn, NJ), sodium azide, urea, ATP, Tris, bacterial protease inhibitor cocktail, propanedithiol and Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Bacterial protease inhibitor cocktail contained AEBSF (serine protease inhibitor), EDTA (metalloprotease inhibitor), bestatin (aminopeptidase inhibitor), pepstatin A (acid protease inhibitor) and E-64 (cysteine protease inhibitor). IPTG was from Lab Scientific Inc. (Livingston, NJ). Luria-Bertani was from EMD Biosciences (Gibbstown, NJ) and Difco nutrient broth was from BD (Franklin lakes, NJ). Pseudomonas stutzeri KC (ATCC 55595), S.coelicolor (ATCC 10147), S.erythrea (ATCC 11635), S.griesus (ATCC 23345) and S.avermitilis (ATCC 31267) were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). B.xenovorans LB400 was a gift from Dr. James Tiedje (Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI) and Rhodococcus sp. RHA1 was provided by Dr. Lindsay Eltis (University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada). Chitin beads and the pTYB1 vector were obtained from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA). Protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford assay. All fluorescence gel images were scanned using a Typhoon 9400 or Typhoon trio (excitation: 532 nm green laser; emission: 580-nm band-pass filter (580 BP 30)) from GE Healthcare Biosciences (Piscataway, NJ). Sonication used a Misonix Sonicator 3000 (Misonix Inc., Farmingdale, NY). ESI-MS analysis was performed on an Esquire-LC-00146 instrument (Bruker, Billerica, MA). 1D SDS-PAGE gel analysis was done using a Hoefer SE 250 mini-vertical gel electrophoresis unit. 2D-gel analysis was done using a Biorad IEF protean cell with ReadyStrip IPG strips (pH 4.0 – 7.0). Econo-pac 10 DG desalting columns were from Bio-rad (Hercules, CA). Dialysis used a Novagen D-tube dialyzer Maxi MWCO 3.5 kDa (EMD biosciences). Labeling reactions were carried out in the dark to prevent fluorophore photo bleaching. Samples were desalted using the CHCl3/methanol precipitation technique unless otherwise mentioned. For this method 100 µL of the sample was treated with 400 µL of methanol, vortexed, 100 µL of CHCl3 was added and the sample was vortexed again. 300 µL of water were then added and the samples were centrifuged at 16000 rcf (relative centrifugal force) for 2 min. The proteins precipitated at the interface. The top phase was removed without disturbing the interface and 400 µL of methanol were added. The sample was again vortexed and centrifuged for 2 min at 16000 rcf to obtain the desalted protein as a pellet. The supernatant was decanted, the pellet was air dried and redissolved in the appropriate buffer. Nano-LC-MS/MS analysis was done at the Proteomics and Mass-spectrometry facility, Cornell University. NanoLC was carried out on an LC Packings Ultimate integrated capillary HPLC system equipped with a Switchos valve switching unit (Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA). The in-gel trypsin-digested peptides were injected using a Famous auto sampler onto a C18 PepMap trap column (5 µm, 300 µm × 5 mm, Dionex) for in-line desalting and then separated on a PepMap C-18 RP nano column, eluting with a 30-minute gradient of acetonitrile (10% to 40%) in 0.1% formic acid at 275 nL/min. The nanoLC was connected to a 4000 Q Trap mass spectrometer (ABI/MDS Sciex, Framingham, MA) equipped with a Micro Ion Spray Head II ion source.

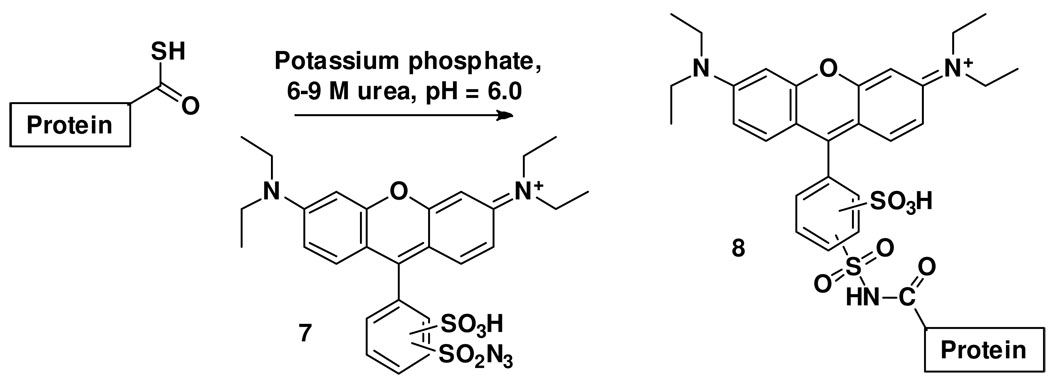

Synthesis of lissamine rhodamine B sulfonyl azide (LRSA)

Lissamine rhodamine B sulfonyl chloride (53 mg, 92 mmol, compound 9, Figure 3) was dissolved in 10 mL of acetone in a round-bottomed flask wrapped in aluminium foil. 29 mg of sodium azide (446 mmol, 5 eq.) were then added and the solution was stirred at room-temperature for 24 h. The solvent was removed in vacuo and the residue was re-dissolved in dichloromethane. The resulting solution was washed with water, dried over anhydrous MgSO4, filtered and the solvent removed in vacuo to give lissamine rhodamine B sulfonyl azide 7 (44.6 mg, 83 %). A 15 mM stock solution in DMSO was prepared and stored in 1 ml aliquots at −20C in the dark. 1H- and 13C-NMR spectra of the two regioisomers (2, 4-) and chemical shift values are shown in supplementary data, Figures 1s and 2s. High resolution ESI-MS (positive mode): m/z = 584.14 (predicted mass: 584.16, supplementary data, Figure 3s).

Figure 3.

Synthesis of lissamine rhodamine B sulfonyl azide (7, LRSA).

Over-expression and purification of ThiS thiocarboxylate (ThiSCOSH) and ThiS DTT thioester (ThiSCODTT)

The thiS gene from T.thermophilus was inserted into pTYB1 (between the NdeI and SapI restriction sites, Forward primer: ggttagcatatggtgtggcttaacggggagccc, Reverse primer: ggtggttgctcttccgcaacccccctgcatcagggccacc). The protein was over-expressed in E.coli BL21(DE3) as follows: 2 L cultures were grown at 37°C in LB medium to an OD600 of 0.6. The temperature was then reduced to 15°C and the cultures were induced with IPTG to a final concentration of 1 mM. Further growth was carried out at 15°C for 12–16 h with constant agitation. The cultures were harvested by centrifugation and lysed by sonication on ice in 20 mM Tris, 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% Triton X-100, pH 7.8. The samples were then loaded onto a column of chitin beads (20 mL) at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min and washed with 300 mL of 20 mM Tris, 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.8 at a flow rate of 2 mL/min. Intein mediated cleavage of the protein was carried out at 4°C for 48 h with 30 mL of 50 mM DTT to give ThiSCODTT or with 30 mL of 50 mM Na2S to yield ThiSCOSH. The proteins were buffer-exchanged by dialysis into 100 mM potassium phosphate, pH 8.0 and stored at −80°C in 30% glycerol. (No reducing agent was added to the frozen stocks as this would reduce the sulfonyl azide during protein labeling).

Labeling of ThiSCOSH with LRSA

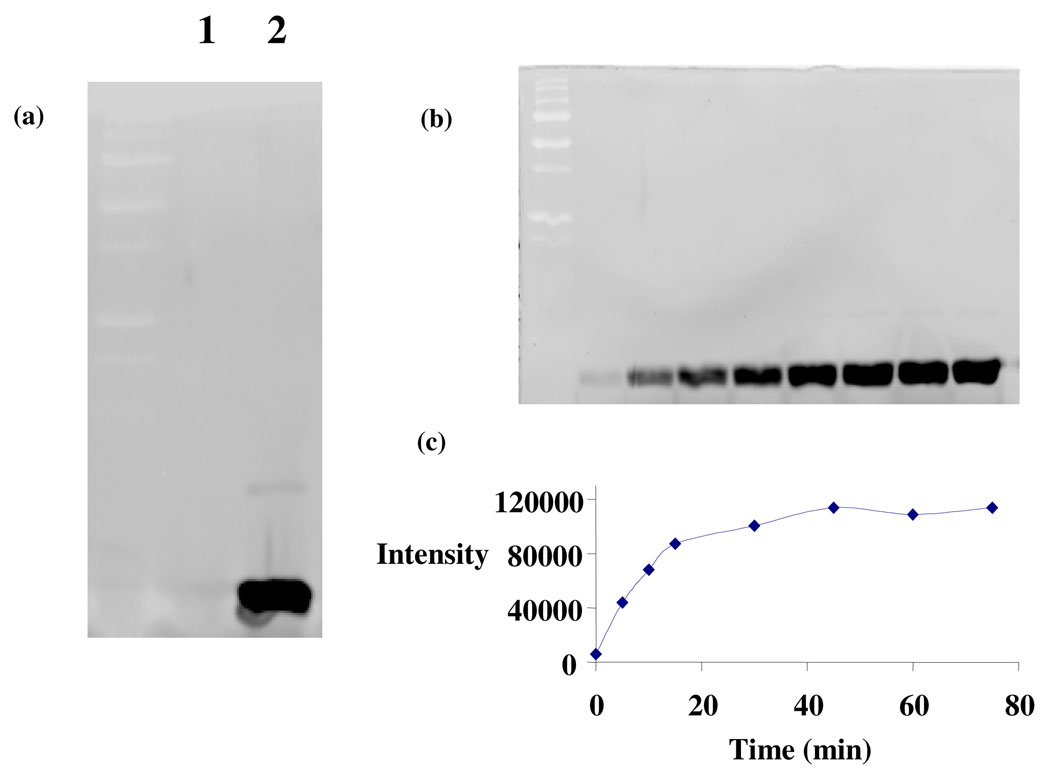

Frozen aliquots of ThiSCOSH and ThiSCODTT (both 184 µM) were thawed and buffer-exchanged into 50 mM potassium phosphate, 6 M urea, pH 6.0. Both proteins (50 µL) were then treated with LRSA (2.5 eq., 1.5 µL of 15mM stock in DMSO). The samples were incubated at room-temperature, in the dark, for 15 min. TCEP (6 µL of 250 mM solution in 1 M potassium phosphate, pH 6.0) was then added and the samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (15% Tris-glycine) and imaged on a Typhoon 9400 (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Reaction of ThiSCODTT and ThiSCOSH with LRSA.

a) ThiSCOSH (lane 2) is labeled with LRSA. ThiSCODTT (Lane 1) does not react. b) Time-dependence of the ThiSCOSH labeling reaction. Samples were analyzed after: 0, 5, 10, 15, 30, 45, 60 and 75 mins. c) Time course for ThiSCOSH labeling quantitated using GE ImageQuant 5.1 software. PMT voltage: 300 V (Typhoon 9400)

Time-course for the labeling reaction

ThiSCOSH was buffer-exchanged into 50 mM potassium phosphate containing 6 M urea at pH 6.0. The resulting protein (100 µL, 93 µM) was incubated with LRSA (3 eq., 2 µL of 15 mM stock made in DMSO). 10 µL aliquots were taken at 0, 5, 10, 15, 30, 45, 60 and 75 min and treated with SDS-PAGE sample buffer (10 µL) containing 50 mM TCEP, analyzed on by SDS-PAGE (15% Tris-glycine) and imaged on a Typhoon 9400 (Figure 4).

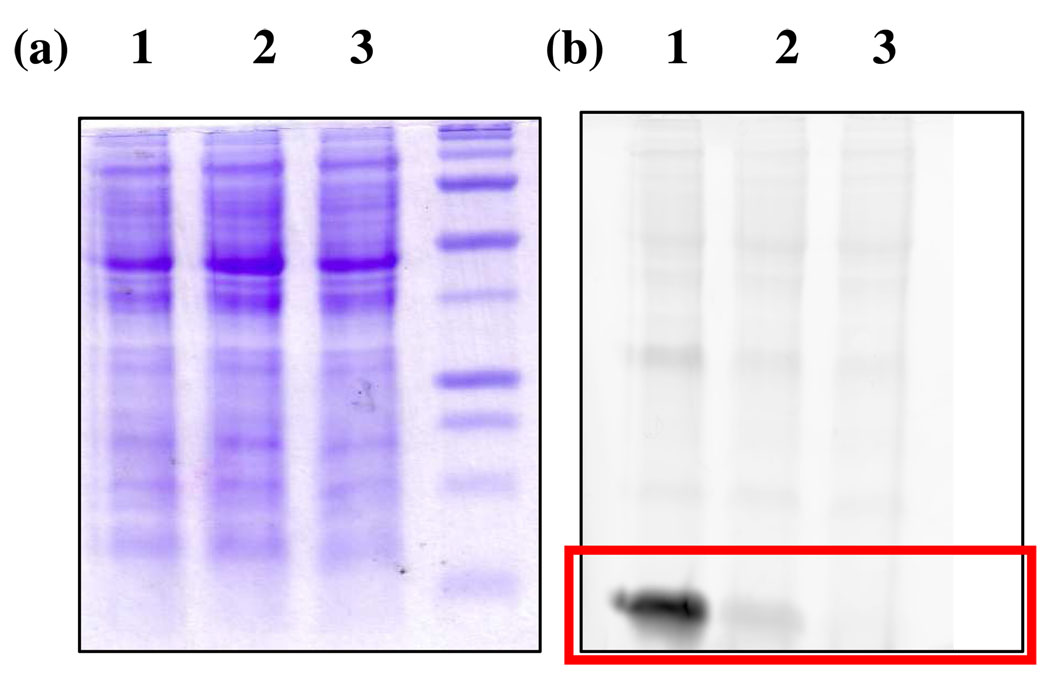

Specificity and detection limits of the labeling chemistry

E.coli BL21(DE3) was grown in 75 mL LB at 37°C to an OD600 of 1.6. The cells were harvested by centrifugation, lysed by sonication on ice in 4 mL of 50 mM potassium phosphate, 300 mM NaCl, 2 mM TCEP, pH 8.0 and centrifuged to obtain the proteome, which was buffer-exchanged into 50 mM potassium phosphate, 9 M urea, pH 6.0 using an Econo-pac 10 DG desalting column. Three 90 µL samples of this extract were prepared containing ThiSCOSH (in 100 mM potassium phosphate, 30% glycerol, pH 8.0) at final concentrations of 11 µM, 1.1 µM and 110 nM. Each sample was treated with 20 µL of LRSA (15 mM stock in DMSO) for 15 min at room-temperature in the dark followed by treatment with 25 mM TCEP for another 30 min in the dark to cleave any sulfenamides formed between LRSA and cysteine thiols.10,11 The samples were desalted by CHCl3/methanol precipitation and then dissolved in 50 µL of 50 mM potassium phosphate, 9 M urea, pH 6.0. An equal volume of SDS-PAGE sample buffer was added and the samples were analyzed on a 16% Tris-tricine gel and imaged on a Typhoon trio (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Sensitivity of labeling of ThiSCOSH in the presence of the E.coli BL21 (DE3) proteome. Lanes 1 (15 µL, 170 picomoles), 2 (15 µL, 17 picomoles) and 3 (15 µL, 1.7 picomoles). a) coomassie staining b) fluorescent image. PMT voltage: 400 V (Typhoon trio).

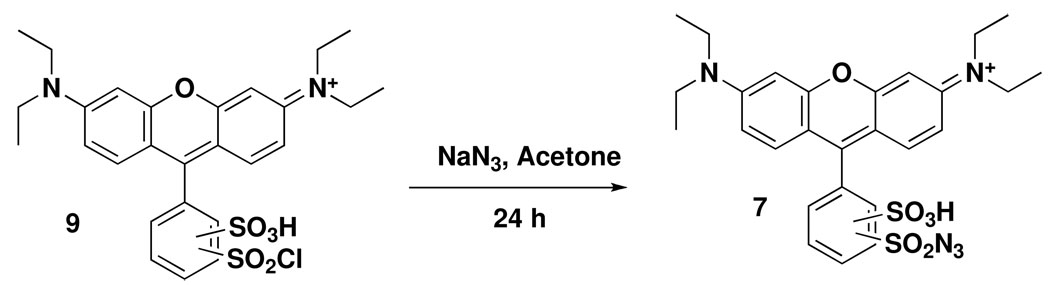

Protein thiocarboxylate detection in the P.stutzeri KC proteome

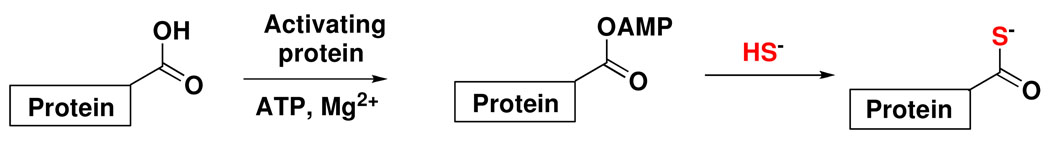

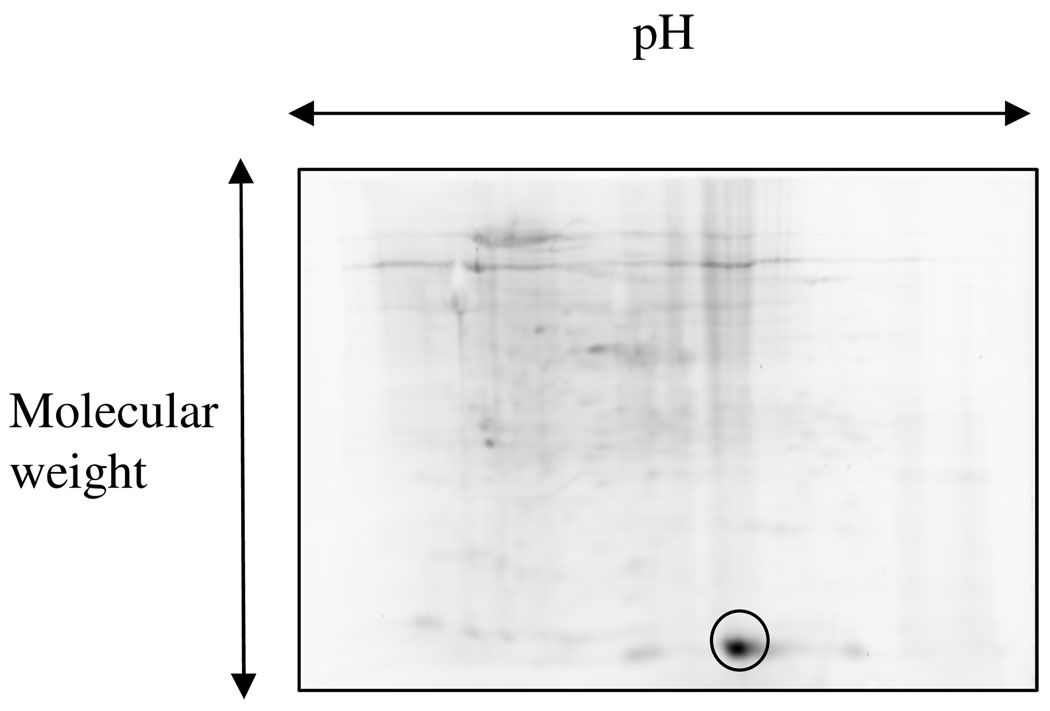

P.stutzeri KC was maintained on a nutrient broth agar plate at 4°C and a colony from this plate was used to inoculate a 100 mL culture of DRM medium12 in a sterile disposable PETG flask with vented closure. The culture was grown at 30°C for 48 h with shaking. The culture was harvested by centrifugation. The P.stutzeri KC cell-pellet was resuspended in 3 mL of 50 mM potassium phosphate, 300 mM NaCl, 2 mM TCEP, pH 8.0 containing 6.5 mg/mL of bacterial protease inhibitor cocktail. The sample was lysed by sonication on ice and clarified by centrifugation. The resulting proteome was then treated with Na2S (9 mM), ATP (18 mM) and MgCl2 (6 mM) and incubated at room-temperature for 6 h to reconstitute protein thiocarboxylate formation (Figure 6). The sample was dialysed into 50 mM ammonium acetate and freeze-dried for storage. For the labeling reaction, the sample was dissolved in 1 mL of 50 mM potassium phosphate, 6 M urea, pH 6.0. An aliquot (100 µL) of this denatured proteome was treated with 20 µL of LRSA (15 mM stock in DMSO) for 15 min at room-temperature in the dark and then with 12 µL of TCEP (250 mM dissolved in water) and further incubated at room-temperature for 30 min in the dark. The sample was precipitated by CHCl3/methanol and subjected to 2D-gel analysis (pH 4–7, 7 cm IEF strip, active rehydration @ 50V for 12 h at 20°C. Four step focussing (20°C): S1: 250V, 15 min, S2: 4000V, linear voltage ramp, 2h, S3: 4000V, rapid voltage ramp, 20000Vh, S4: 500V, hold. Current limit/gel: 50 µA). The lower molecular weight fluorescent spot, imaged on a Typhoon trio, was excised from the gel and subjected to nano-LC-MS/MS analysis.

Figure 6.

Strategy used to reconstitute protein thiocarboxylate formation prior to LRSA labeling.

Growth conditions for other organisms

Typical growth conditions for Burkolderia xenovorans LB400, Streptomyces coelicolor, Streptomyces griesus, Saccharopolyspora erythrea, Streptomyces avermitilis and Rhodococcus sp. RHA1 are shown in Table 1s (Supplementary data). All the cultures were harvested by centrifugation and lysed by sonication (in case of S.avermitilis and S.griesus, this step was preceded by homogenization). The labeling protocol was the same as that used for the P.stutzeri KC proteome.

Iron dependence of protein thiocarboxylate labeling in the P.stutzeri proteome

P.stutzeri KC (ATCC 55595) from a nutrient broth agar plate, maintained at 4°C, was used to inoculate DRM medium (100 mL )12 in a sterile disposable PETG flask with vented closure. This low-iron culture was grown, with shaking, at 30°C for 48 h and harvested by centrifugation. For iron-rich conditions, nutrient broth was used to grow the bacteria at 30°C to an OD600 of 1.0. The resulting cell-pellets were suspended in 3 mL of lysis buffer (50 mM potassium phosphate, 300 mM NaCl, 2 mM TCEP, pH 8.0 containing 6.5 mg/mL of bacterial protease inhibitor cocktail), lysed by sonication on ice and clarified by centrifugation. To reconstitute protein thiocarboxylate formation, Na2S, ATP and MgCl2 were added (final concentrations 9 mM, 18 mM and 6 mM respectively) and the samples were incubated at room-temperature for 6 h. As controls, thiocarboxylate reconstitution was omitted from one low iron sample and a second was blocked by iodoacetic acid alkylation. For the latter sample, freshly prepared iodoacetic acid (in 1 M potassium phosphate, pH 8.0) was added to the sample to a final concentration of 100 mM. All samples were further incubated at room-temperature for 1 h, buffer-exchanged, by dialysis, into 50 mM ammonium acetate and freeze-dried. The residue thus obtained was dissolved in labeling buffer (50 µL of 50 mM potassium phosphate, 6 M urea, pH 6.0), 2 µL of LRSA (15 mM stock in DMSO) was added and the samples were incubated in the dark at room-temperature for 15 min. Equal volumes of 50 mM TCEP in 100 mM potassium phosphate, pH 8.0 were added to the samples which were further incubated in the dark for 30 min. The samples were then precipitated with CHCl3/methanol and re-dissolved in 50 mM potassium phosphate, 6 M urea, pH 6.0. Equal volumes of SDS-PAGE sample buffer containing 50 mM TCEP were added and the samples were analyzed on a 16% Tris-tricine gel imaged on a Typhoon 9400.

RESULTS

Synthesis of lissamine rhodamine B sulfonyl azide (LRSA)

LRSA 7 was obtained in high yield, in a single step, from a readily available starting material (Figure 3). The product consisted of two regio-isomers (2, 4-) as shown and was characterized by 1Hand 13C-NMR and high resolution ESI-MS.

ThiSCOSH and ThiSCODTT production and labeling

The T.thermophilus thiS gene was cloned into pTYB1, an E. coli cloning and expression vector designed for the in-frame insertion of a target gene adjacent to the Sce VMA intein/chitin binding domain (55 kDa). This results in the fusion of the C-terminus of the target protein to the N-terminus of the intein tag13. Cleaving the over-expressed ThiS-intein with sulfide or DTT yielded the thiocarboxylate (ThiSCOSH) or the thioester ThiSCODTT. LRSA labeled ThiSCOSH but not ThiSCODTT confirming the expected thiocarboxylate specificity of the labeling reaction. Approximately 70% labeling was achieved in 15 min (Figure 4).

To further evaluate the specificity and sensitivity of the labeling reaction, ThiSCOSH was added to the E.coli BL21(DE3) proteome in varying concentrations and the labeling reaction was carried out under denaturing conditions (9 M urea, Figure 5). Labeled ThiSCOSH could clearly be seen at 17 picomoles but not at 1.7 picomoles on a 1D SDS-PAGE gel. This places the sensitivity of the labeling reaction at approximately 10 picomoles.

Detection of protein thiocarboxylates in a bacterial proteome

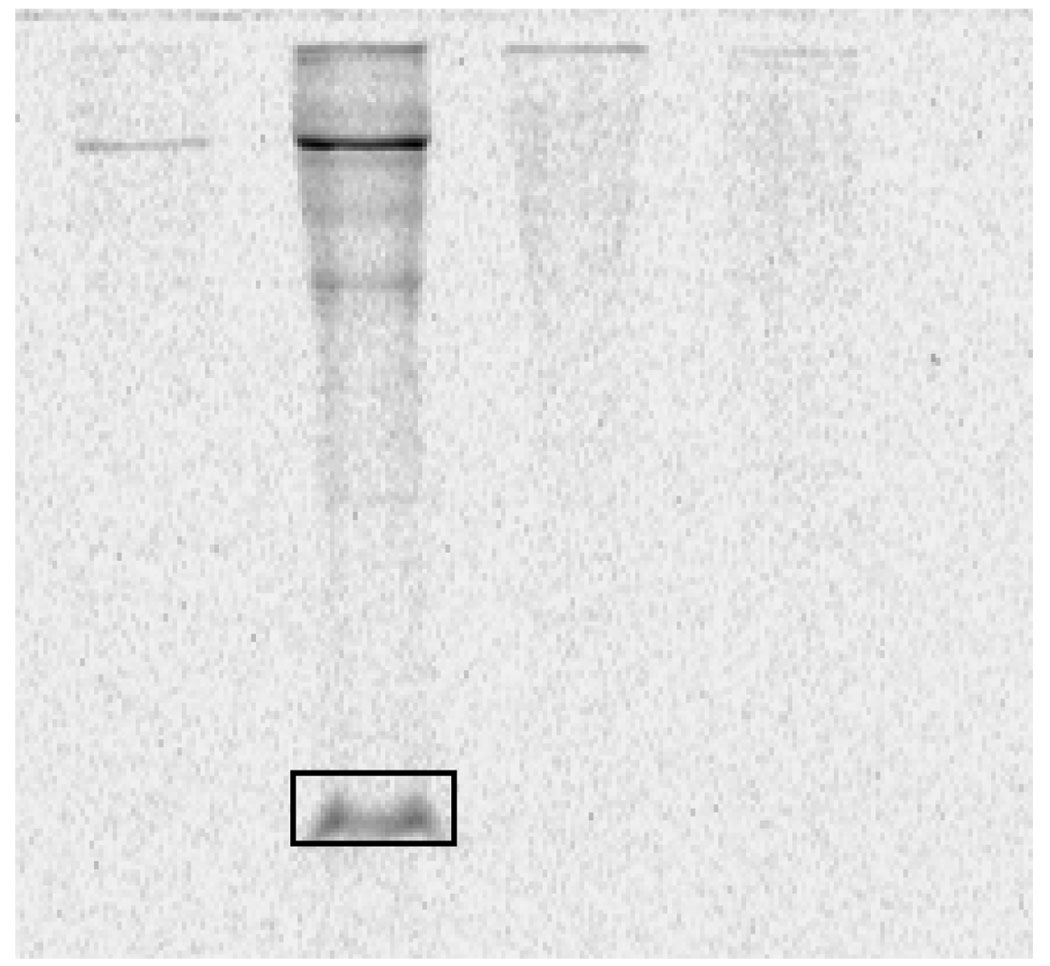

The proteomes from several bacterial sources (P.stutzeri, S.coelicolor, S.avemitilis, S.griesus, Burkolderia xenovorans, Saccharopolyspora erythrea and Rhodococcus sp. RHA1) were treated with sodium sulfide, ATP and Mg2+ to reconstitute protein thiocarboxylate formation (Figure 6) and labeled with LRSA followed by analysis by 1D and 2D SDS-PAGE. The P.stutzeri KC (Figure 7) and S.coelicolor proteomes showed strong protein labeling in the lower-molecular weight region characteristic of ThiSCOSH orthologs (approx 10kDa). S.avemitilis showed weak labeling and Burkolderia xenovorans LB400, Streptomyces griesus, Saccharopolyspora erythrea and Rhodococcus sp. RHA1 did not show any labeling (data not shown). The labeled protein in the P.stutzeri KC proteome was isolated, subjected to LC-MS/MS analysis (Supplementary data, Figures 4s and 5s) and identified as PdtH, a ThiSCOSH ortholog proposed to function as the sulfide donor in the biosynthesis of the pyridine dithiocarboxylic acid siderophore (4, Figure 1).

Figure 7.

2D-gel analysis of P.stutzeri KC proteome labeled with LRSA, 7 cm IEF strip, pH 4–7, PMT voltage: 400 V (Typhoon trio)

The P.stutzeri KC proteome was also isolated from cells grown under iron-rich and iron-depleted conditions and treated with LRSA. Labeling of the protein assigned as PdtH was observed only in the iron-depleted proteome. The proteome produced under iron-rich conditions did not show labeling. In addition, proteome not subjected to thiocarboxylate reconstitution or proteome in which the thiocarboxylate was alkylated with iodoacetic acid did not show labeling (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Labeling of the P.stutzeri KC proteome with LRSA. Lane 1: proteome produced in iron-limiting medium without thiocarboxylate reconstitution, Lane 2: proteome produced in iron-limiting medium with thiocarboxylate reconstitution, Lane 3: Lane 2 sample treated with iodoacetic acid prior to labeling. Lane 4: proteome produced in iron-rich medium with thiocarboxylate reconstitution. PMT voltage: 250 V (Typhoon 9400).

Discussion

The involvement of protein thiocarboxylates in an increasing number of biosynthetic pathways involving sulfide chemistry suggested that a sensitive labeling strategy would be of use in assays for protein thiocarboxylate formation and in screening bacterial proteomes for protein thiocarboxylate formation. Here we describe the development of lissamine rhodamine B sulfonyl azide (7, LRSA) as our first generation reagent to address this problem. This reagent rapidly labels ThiSCOSH under mild conditions (Figure 4). The reagent also labels ThiSCOSH in the presence of the E.coli proteome. In this experiment, less than 10 picomoles of labeled protein could be detected (Figure 5). Under normal conditions, protein thiocarboxylates are not expected to accumulate in the proteome. Therefore to maximize their concentration, the proteome was treated with sulfide and ATP (Figure 6) prior to labeling with LRSA. This strategy assumes that high concentrations of sulfide can replace the physiological sulfide donor. This may not always be the case and the possibility remains that we have not yet identified optimal conditions for maximizing thiocarboxylate concentrations in the proteome. This may be an important factor in limiting the sensitivity of our thiocarboxylate detection strategy.

The gels shown in Figures 5, 7 and 8 show staining of other proteins with LRSA. We currently do not understand the nature of this labeling. It is unlikely due to cysteine labeling because the mercaptoethanol and TCEP treatment after labeling would reduce sulfenamides10–11. Labeling could be due to displacement of azide by hyper-reactive nucleophiles. Alternatively, our assumption that all thiocarboxylate containing proteins are orthologs of ThiS (i.e. <10kDa with the thiocarboxylate at the carboxy terminus) may not be correct and it is possible that the thiocarboxylate posttranslational modification also occurs on larger proteins.

Detection of protein thiocarboxylates in the P.stutzeri KC proteome was next chosen as a test system. This micro-organism produces the pyridine dithiocarboxylate siderophore (4, PDTC) under iron-limiting conditions14. The PDTC biosynthetic gene cluster encodes a ThiS ortholog (PdtH) likely to be involved in the formation of the siderophore thiocarboxylate. This putative functional assignment was confirmed by treating the P.stutzeri KC proteome prepared from cells grown in the presence of high and low iron with LRSA. For the low-iron sample, a band with the expected molecular mass was labeled and identified by MS analysis as PdtH thiocarboxylate. This band was absent from the high-iron proteome as expected because the biosynthesis of pyridine dithiocarboxylic acid in P.stutzeri KC is repressed by iron15 (Figure 8).

Our detection limit of less than 10 picomoles of labeled protein converts to approximately 6,000 copies of the protein thiocarboxylate per cell (E.coli cell volume = 10−15L, 1OD=109cells/ml)16,17. To place this number in context, E.coli has between 7,000 and 72,000 ribosomes/cell and 370,000 pyruvate molecules/cell.18,19 This demonstrates that the LRSA labeling strategy is likely to be most useful in surveying bacterial proteomes for highly expressed protein thiocarboxylates. The sensitivity of the method however could in principle be increased by attaching a sulfonyl azide to a solid support via a cleavable linker. In this way, protein thiocarboxylate could be isolated and concentrated from large samples prior to SDS PAGE analysis.

We have surveyed several other bacteria for protein thiocarboxylates. We have detected strong labeling of a putative ThiS ortholog in Streptomyces coelicolor, a weakly-labeled spot in Streptomyces avermitilis and not detected protein thiocarboxylates in the proteomes of Burkolderia xenovorans, Rhodococcus sp. RHA1, Streptomyces griesus and Saccharopolyspora erythrea. Few reasons for not noticing labeling in the cell-free extracts of these organisms could be low reconstitution of protein thiocarboxylates in the proteome with sulfide as the sulfur donor or non-expression of thiocarboxylate-forming proteins under the growth conditions.

CONCLUSIONS

Protein thiocarboxylates function as key intermediates in the biosynthesis of a variety of natural products. Lissamine rhodamine B sulfonyl azide (LRSA) labels protein thiocarboxylates to give stable fluorescent adducts that can be detected by SDS-PAGE. The reaction is selective and occurs under mild conditions with a detection limit of >10 pmoles. To illustrate the applicability of this labeling strategy, LRSA was used to detect a protein thiocarboxylate in the Pseudomonas stutzeri proteome proposed to be involved in the biosynthesis of the pyridine dithiocarboxylic acid siderophore. This reagent will be of use in assays of protein thiocarboxylate formation as well as for the detection of protein thiocarboxylates in the bacterial proteome.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This research was supported by NIH grant DK44083. We thank Cynthia Kinsland (Protein production facility, Cornell University) for protein overexpression and Dr. Sabine Baumgart (Proteomics and massspectrometry facility, Cornell University) for MS analysis and Dr. Sameh Abdelwahed for LRSA NMR analysis.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. 1H-NMR and ESI-MS data for lissamine rhodamine sulfonyl azide; MS data for the identification of PdtH and growth conditions for bacteria screened for protein thiocarboxylates. This information is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dorrestein PC, Zhai H, McLafferty FW, Begley TP. Chem Biol. 2004;11(10):1373–1381. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leimkuhler S, Wuebbens MM, Rajagopalan KV. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(37):34695–34701. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102787200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Godert AM, Jin M, McLafferty FW, Begley TP. J Bacteriol. 2007;189(7):2941–2944. doi: 10.1128/JB.01200-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burns KE, Baumgart S, Dorrestein PC, Zhai H, McLafferty FW, Begley TP. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127(33):11602–11603. doi: 10.1021/ja053476x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leidel S, Pedrioli PG, Bucher T, Brost R, Costanzo M, Schmidt A, Aebersold R, Boone C, Hofmann K, Peter M. Nature. 2009;458(7235):228–232. doi: 10.1038/nature07643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Merkx R, Brouwer AJ, Rijkers DT, Liskamp RM. Org Lett. 2005;7(6):1125–1128. doi: 10.1021/ol0501119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shangguan N, Katukojvala S, Greenberg R, Williams LJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125(26):7754–7755. doi: 10.1021/ja0294919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kolakowski RV, Shangguan N, Sauers RR, Williams LJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128(17):5695–5702. doi: 10.1021/ja057533y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang X, Li F, Lu XW, Liu CF. Bioconjug Chem. 2009;20(2):197–200. doi: 10.1021/bc800488n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ueki M, Maruyama H, Mukaiyama T. Bulletin of the chemical society of japan. 1971;44(4):1108–1111. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cartwright IL, Hutchinson DW, Armstrong VW. Nucleic Acids Res. 1976;3(9):2331–2339. doi: 10.1093/nar/3.9.2331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee CH, Lewis TA, Paszczynski A, Crawford RL. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;261(3):562–566. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kinsland C, Taylor SV, Kelleher NL, McLafferty FW, Begley TP. Protein Sci. 1998;7(8):1839–1842. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sebat JL, Paszczynski AJ, Cortese MS, Crawford RL. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67(9):3934–3942. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.9.3934-3942.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sepulveda-Torre L, Huang A, Kim H, Criddle CS. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2002;4(2):151–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kubitschek HE. J. Bacteriol. 1990;172(1):94–101. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.1.94-101.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sezonov G, Joseleau-Petit D, D'Ari R. J. Bacteriol. 2007;189(23):8746–8749. doi: 10.1128/JB.01368-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bremer H, Dennis PP. In: Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: Cellular and Molecular Biology, 2nd ed. 2nd ed. Neidhardt eae., editor. 1996. p. 1559. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bennett BD, Kimball EH, Gao M, Osterhout R, Van Dien SJ, Rabinowitz JD. Nature Chemical Biology. 2009;5(8):593–599. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.