Abstract

Background

Dental erosion has been investigated in developed and developing countries and the prevalence varies considerably in different countries, geographic locations, and age groups. With the lifestyle of the Chinese people changing significantly over the decades, dental erosion has begun to receive more attention. However, the information about dental erosion in China is scarce. The purpose of this study was to explore the prevalence of dental erosion and associated risk factors in 12-13-year-old school children in Guangzhou, Southern China.

Methods

This cross-sectional survey was performed by two trained, calibrated examiners. A stratified random sample of 12-13-year-old children (774 boys and 725 girls) from 10 schools was examined for dental erosion using the diagnostic criteria of Eccles and the index of O'Sullivan was applied to record the distribution, severity, and amount of the lesions. Data on the socio-economic status, health behaviours, and general health involved in the etiology of dental erosion were obtained from a self-completed questionnaire. The analyses were performed using SPSS software.

Results

At least one tooth surface with signs of erosion was found in 416 children (27.3%). The most frequently affected teeth were the central incisors (upper central incisors, 16.3% and 15.9%; lower central incisors, 17.4% and 14.8%). The most frequently affected surface was the incisal or occlusal edge (43.2%). The loss of enamel contour was present in 54.6% of the tooth surfaces with erosion. Of the affected tooth surfaces, 69.3% had greater than one-half of the tooth surface was affected. The results from logistic regression analysis demonstrated that the children who were female, consumed carbonated drinks once a week or more, and those whose mothers were educated to the primary level tended to have more dental erosion.

Conclusions

Dental erosion in 12-13-year-old Chinese school children is becoming a significant problem. A strategy of offering preventive care, including more campaigns promoting a healthier lifestyle for those at risk of dental erosion should be conducted in Chinese children and their parents.

Background

Dental erosion is defined as the loss of hard dental tissue due to the chemical influence of extrinsic and intrinsic acids without bacterial involvement [1]. It is becoming an increasingly important factor when considering the long-term health of the dentition. If dental erosion is not controlled and stabilized, the child may suffer from severe tooth surface loss, tooth sensitivity, over closure, poor aesthetics, or even dental abscesses in the affected teeth [2]. Erosive lesions frequently require preventive and restorative treatments, which will add the family and government's public health burden. The etiology of dental erosion is multi-factorial and not fully understood. Currently, the increased consumption of acidic foods and carbonated beverages is becoming an important factor in the development of dental erosion [3]. The acidic attack leads to an irreversible loss of dental hard tissue, which is accompanied by a progressive softening of the surface [3].

Epidemiologic surveys have investigated dental erosion in developed and developing countries. These results have shown that the prevalence of dental erosion varies considerably in different countries, geographic locations, and age groups (Table 1). With the rapid economic development in China, the lifestyle of the Chinese people, including diet and attitude toward dental health, has changed significantly through the decades. Dental disorders, such as dental erosion, have begun to receive more attention, but the information about dental erosion is scarce.

Table 1.

Prevalence of dental erosion in 11-14-year-old children

| Author | Year | Country | Age | Sample size | Present (%) | Exposed Dentine (%) | Teeth examined |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Dlaigan [29] | 2001 | UK | 14 | 418 | 100 | 52 | All permanent teeth |

| Deery [13] | 2000 | UK | 11-13 | 125 | 37 | 0 | Upper permanent incisors |

| USA | 11-13 | 129 | 41 | 0 | Upper permanent incisors | ||

| Ganss [30] | 2001 | German | 11.4 | 1000 | 11.6 | 0.2 | All permanent teeth |

| Al-Majed [8] | 2002 | Saudi Arabia | 12-14 | 862 | 95 | 26 | Upper permanent incisors and first molars |

| Dugmore [21] | 2004 | UK | 12 | 1753 | 59.7 | 2.7 | permanent incisors and first molars |

| Peres [19] | 2005 | Brazil | 12 | 499 | 13.0 | 0.32 | Upper permanent incisors |

| Caglar [10] | 2005 | Turkey | 11 | 153 | 28 | 0 | All permanent teeth |

| EL Karim [14] | 2007 | Sudan | 12-14 | 157 | 66.9 | 0 | Upper permanent incisors |

| Auad [12] | 2007 | Brazil | 13-14 | 458 | 34.1 | 0 | All permanent teeth |

| Waterhouse [31] | 2008 | Brazil | 13-14 | 458 | 34.1 | 0 | All permanent teeth |

| Talebi [24] | 2009 | Iran | 12 | 483 | 38.1 | 4.0 | Upper permanent incisors |

| Correr [11] | 2009 | Brazil | 12 | 389 | 26 | 35 | All permanent teeth |

The sample age in studies of the prevalence of dental erosion was 3-50 years old [4]. Many studies have focused on 12-year-old children (Table 1) because the permanent incisors and first molars of children at this age have been exposed to potential etiologic factors in the mouth for a considerable duration compared to other teeth. Furthermore, the differentiation of erosion from attrition or abrasion is easier at this age compared to adults.

The objective of the present study was to evaluate the dental erosion status among 12-13-year-old school children in Guangzhou, Southern China, including the prevalence, distribution, and severity of dental erosion in the permanent dentition at the tooth and surface level. This investigation also aimed to explore the associated socioeconomic and behavioral risk factors influencing the prevalence of dental erosion.

Methods

Sample

Guangzhou is the capital city of the Guangdong province, which is located in Southern China. The climate is hot and long in the summer due to its location in the southern subtropical zone. The summer is 6 months in length (May to October). Guangzhou is a rapidly developing city with a population of approximately 10 million. The gross domestic product (GDP) per capita was USD 9,302 in 2007, and Guangzhou ranked as the third economically developed city in China, following Beijing and Shanghai [5].

A cross-sectional study was conducted in Guangzhou by a stratified multi-stage cluster sampling. A pilot study was performed before the formal study. The prevalence of dental erosion was 20.8% for 175 school children (12-13 years of age) examined from an urban junior high school. A total of 1,500 school children were proposed in our study according to the sample size formula for the estimation of prevalence (α = 0.05) in order to decrease study error. Guangzhou is comprised of 10 urban districts and 2 suburban districts. The population ratio between the urban and suburban regions was approximately 4:1 [5]. Four urban districts and one suburban district were selected by simple random sampling. A list of all junior high schools in these districts was obtained from the local Department of Education. Two junior high schools were selected by simple random sampling in each district. In each school, three classes of grade one students were selected by the same sampling method and 140-160 children were cluster-selected. All of the selected children were 12-13 years of age. Those who were with orthodontic appliances, enamel defect accompanied by a loss of tooth substance, and fractured or missing teeth of the incisors or the first molars were excluded. A total of 1,499 children (774 boys and 725 girls), 12-13 years of age, from 10 junior high schools were invited to participate in the study.

The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Guanghua School of Stomatology of Sun Yat-sen University. An informed consent letter regarding the aim and importance of the study was signed by the children and the parents/guardians before starting the survey, which assured that children participated in the study on their own accord.

Calibration of examiners

Training and calibration exercises were conducted prior to the study. An experienced dental epidemiologist who had a high level of education and experience, was responsible for training and calibrating two examiners. The diagnostic criteria of dental erosion were thoroughly discussed with the examiners. A range of dental erosion levels based on the diagnosis via photographic images was reviewed in the calibration exercise. The epidemiologist also provided instruction for the examiners during the pilot study.

To assess the reproducibility of the diagnostic criteria, approximately 10% of the subjects were re-examined (only the labial surfaces of the upper incisors). In every dental examination section at each school, approximately 15 students in intervals of 10 were re-examined by the same examiner and another examiner. The results of the duplicate examinations were used to estimate the intra- and inter-examiner reliability.

Clinical Examination

The two previously calibrated examiners participated in the clinical examinations and visited the selected schools. The clinical examinations were performed in well-lit classrooms or in shaded places under natural light using plane mouth mirrors and sterilized cotton to remove debris. The central incisors, lateral incisors, and first molars in the upper and lower jaws were examined. The diagnostic criteria of dental erosion proposed by Eccles [6] were used in this study. The index of O'Sullivan [7] was adopted to record the distribution, severity, and amount of affected teeth. This index is especially designed for epidemiologic surveys and for the diagnosis of erosion in children to determine treatment options.

O'sullivan index for measurement of dental erosion:

Site on erosion on each tooth

Code A: Labial or buccal only

Code B: Lingual or palatal only

Code C: Occlusal or incisal only

Code D: Labial and incisal/occlusal

Code E: Lingual and incisal/occlusal

Code F: Multi-surface

Grade of severity (worst score for an individual tooth recorded)

Code 0: Normal enamel

Code 1: Matt appearance of the enamel surface with no loss of contour

Code 2: Loss of enamel only (loss of surface contour)

Code 3: Loss of enamel with exposure of dentine (enamel-dentin junction visible)

Code 4: Loss of enamel and dentine beyond enamel-dentin junction

Code 5: Loss of enamel and dentine with exposure of the pulp

Code 9: Unable to assess (e.g. tooth crowned or large restoration)

Area of surface affected by erosion

Code -: Less than half of surface affected

Code +: More than half of surface affected

Questionnaire

The school children completed a questionnaire at the schools prior to the clinical examination. The questionnaire was designed to reflect the socio-economic status, behavioural factors, and general health involved in the etiology of erosion, as proposed by Lussi [3] and in other studies [8,9]. The pilot study was carried out to test and refine the questionnaire.

The questionnaire included questions about general information (gender and age), socio-economic status, occupation and education levels of the parents, oral hygiene habits, frequencies of ingesting certain beverage types, amount of acidic drink intake per week (including carbonated drinks, sport drinks, lemon tea, and fruit juices), special drinking habits, general health (including frequency of vomiting and heartburn or nausea in this study), and vitamin C supplements. The frequency of swimming in summer was also included in the questionnaire because of possible lower pH value in the water of swimming pools [3].

Statistical analyses

The study data were entered into a computer using Epidata (version 3.0) and analyzed using SPSS software (version 13.0). Intra- and inter-examiner agreement was evaluated using Cohen's kappa. Descriptive analysis was conducted to describe the prevalence and characteristics of dental erosion. A two-step approach was used to analyze risk factors of dental erosion. First, bivariate analysis was used to test the relationship between dental erosion and the associated factors. Then, a logistic regression analysis was used to analyse the factors that were independently related to the presence of erosion. The variables (P < 0.5) in the bivariate analyses were entered into a logistic regression model in a forward fashion. The level of statistical significance was set at 5%.

Results

Clinical data

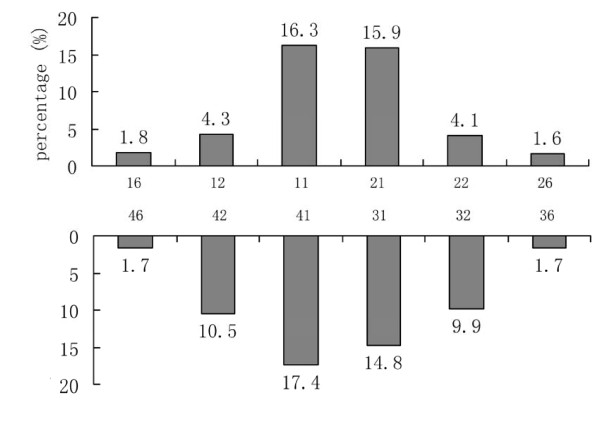

In our study, 1,499 school children (774 boys and 725 girls), 12-13 years of age, were examined. Signs of erosion on at least one tooth surface occurred in 416 children and the prevalence of dental erosion was 27.3% (95% CI = 25.0%-29.6%). The prevalence of 12- and 13-year-old children was 25.5% and 29.0%, respectively (P = 0.151). There was no significant difference in the prevalence of dental erosion in children in urban and suburban areas (26.2% vs. 28.9%; P = 0.087). The most frequently affected teeth were the central incisors, followed by the lateral incisors and first molars (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Percentage of teeth affected with any signs of dental erosion for children aged 12-13 years

A total of 17,988 teeth (53,964 tooth surfaces) were examined in this study and 1,895 teeth (3,288 surfaces) showed signs of erosion. The most frequently affected surface was the incisal/occlusal edge (43.2%), followed by the labial and incisal/occlusal surfaces (22.7%). Regarding the severity of dental erosion, most affected tooth surfaces exhibited the loss of enamel contour (54.6%). Of the affected tooth surfaces, 69.3% showed that greater than one-half of the tooth surface was affected (Table 2).

Table 2.

Percentage of affected tooth surfaces, severity, and area of the surfaces affected by dental erosion according to the number of teeth/surfaces

| No. of teeth/surfaces | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Affected surface | ||

| Labial or buccal only | 146 | 7.7 |

| Lingual or palatal only | 72 | 3.8 |

| Incisal or occlusal only | 818 | 43.2 |

| Labial and incisal/occlusal | 430 | 22.7 |

| Lingual and incisal/occlusal | 58 | 3.0 |

| Multi-surface | 371 | 19.6 |

| Total (teeth) | 1895 | 100.0 |

| Severity | ||

| Matt appearance of the enamel | 1447 | 44.0 |

| Loss of enamel only | 1795 | 54.6 |

| Loss of enamel with exposure of dentin (enamel-dentin junction visible) | 46 | 1.4 |

| Total (surfaces) | 3288 | 100.0 |

| Area affected | ||

| Less than half of surface affected | 1008 | 30.7 |

| More than half of surface affected | 2280 | 69.3 |

| Total (surfaces) | 3288 | 100.0 |

Diagnostic reproducibility was assessed by examining the labial surfaces of upper incisors. Duplicate examinations of a total of 150 students yielded two kappa values (both were 0.92) for intra-examiner reproducibility and a kappa value of 0.73 for inter-examiner reproducibility, which indicated good agreement for reproducibility of erosion.

Questionnaire data/associated risk factors

Socio-economic factors were based on the occupation and education levels of the parents because the income of the children being examined was unknown. The results analysed with a chi-square test indicated that children with mothers that had higher levels of education tended to have a lower prevalence of dental erosion (P < 0.05; Table 3). There was a significant difference in the prevalence of dental erosion in relation to the frequency of consumption of carbonated drinks (P < 0.05; Table 4). No significant association was found between dental erosion and oral hygiene habits, general health, and vitamin C supplements (Table 5).

Table 3.

Socio-economic factors based on the children's gender, parent's level of education, and occupation in relation to the prevalence of dental erosion

| Variables | Total No. of children | Dental erosion | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of children | % | P | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 774 | 199 | 25.7 | 0.068 |

| Female | 725 | 217 | 29.9 | |

| Father's education | ||||

| Primary | 544 | 169 | 31.1 | 0.069 |

| Secondary | 633 | 169 | 26.7 | |

| College and postgraduate | 322 | 78 | 24.2 | |

| Mother's education* | ||||

| Primary | 665 | 196 | 29.5 | 0.035 |

| Secondary | 575 | 165 | 28.7 | |

| College and postgraduate | 259 | 55 | 21.2 | |

| Father's occupation | ||||

| Employers/professional | 327 | 93 | 28.4 | 0.909 |

| Employees/non-professional | 857 | 238 | 27.8 | |

| Unemployed | 315 | 85 | 27.0 | |

| Mother's occupation | ||||

| Employers/professional | 244 | 59 | 24.2 | 0.384 |

| Employees/non-professional | 948 | 268 | 28.3 | |

| Unemployed | 307 | 89 | 29.0 | |

*P < 0.05, Chi-squared test.

Table 4.

The frequency of consumption of drinks and foods, and special drinking habits in relation to the prevalence of dental erosion

| Variables | Total No. of children | Dental erosion | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of children | % | P | ||

| Frequency of carbonated drinks* | ||||

| < once a week | 936 | 243 | 26.0 | 0.046 |

| ≥once a week | 563 | 173 | 30.7 | |

| Frequency of sport drinks | ||||

| < once a week | 1089 | 305 | 28.0 | 0.719 |

| ≥once a week | 410 | 111 | 27.1 | |

| Frequency of lemon tea | ||||

| < once a week | 1102 | 310 | 28.1 | 0.585 |

| ≥once a week | 397 | 106 | 26.7 | |

| Frequency of succade | ||||

| < once a week | 1160 | 314 | 27.1 | 0.275 |

| ≥once a week | 339 | 102 | 30.1 | |

| Frequency of fruits | ||||

| < once a week | 180 | 52 | 28.9 | 0.716 |

| ≥once a week | 1319 | 364 | 27.6 | |

| Frequency of fruit juices | ||||

| < once a week | 940 | 253 | 26.9 | 0.348 |

| ≥once a week | 559 | 163 | 29.2 | |

| Frequency of chewing gum | ||||

| < once a week | 817 | 233 | 28.5 | 0.468 |

| ≥once a week | 682 | 183 | 26.8 | |

| Amount of acidic drinks intake | ||||

| < 250 ml/week | 408 | 103 | 25.2 | 0.406 |

| 250-1000 ml/week | 962 | 275 | 28.5 | |

| > 1000 ml/week | 129 | 38 | 29.4 | |

| Drinking with straw or not | ||||

| Drinking with straw | 475 | 138 | 29.2 | 0.444 |

| Drinking without straw | 1024 | 278 | 27.1 | |

| Method of drinking | ||||

| Sucking or holding drinks in mouth | 328 | 81 | 24.7 | 0.162 |

| Drinking straight away | 1171 | 335 | 28.6 | |

| Frequency of drinks taken at night | ||||

| Once or more monthly | 82 | 26 | 31.7 | 0.418 |

| Never/occasionally | 1417 | 390 | 27.5 | |

*P < 0.05, Chi-square test

Table 5.

Oral hygiene habits, general health, vitamin C supplements, and frequency of swimming in relation to the prevalence of dental erosion

| Variables | Total No. of children | Dental erosion | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of children | % | P | ||

| Frequency of brushing | ||||

| Once or less daily | 459 | 136 | 29.6 | 0.281 |

| Twice or more daily | 1040 | 280 | 26.9 | |

| Duration of brushing | ||||

| ≤1 min | 266 | 73 | 27.4 | 0.908 |

| 2 min | 702 | 192 | 27.4 | |

| ≥3 min | 531 | 151 | 28.4 | |

| Types of toothpaste | ||||

| Fluoride | 656 | 170 | 25.9 | 0.333 |

| Non-fluoride | 74 | 20 | 27.0 | |

| Not sure | 769 | 226 | 29.4 | |

| Vomiting | ||||

| Once or more monthly | 16 | 2 | 12.5 | 0.171 |

| Never/occasionally | 1483 | 414 | 27.9 | |

| Heartburn or nausea | ||||

| Once or more monthly | 9 | 0 | - | 0.136 |

| Never/occasionally | 1490 | 416 | 27.9 | |

| Vitamin C supplements | ||||

| Yes | 273 | 78 | 28.6 | 0.749 |

| No | 1226 | 338 | 27.6 | |

| Frequency of swimming in summer | ||||

| Once or more weekly | 732 | 193 | 26.4 | 0.229 |

| Never/occasionally | 767 | 223 | 29.1 | |

Chi-square test

When other variables were taken into account, factors that remained statistically significant were gender, frequency of consumption of carbonated drinks, and the level of education of the mother (Table 6). The children who were female, consumed carbonate drinks more than once a week, and had mothers that were educated to the primary level had more dental erosion (P < 0.05).

Table 6.

Logistic regression analysis results in relation between the prevalence of dental erosion and children's gender, frequency of consumption of carbonated drinks, and mother's level of education

| 95% CI for OR | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | B | SE | P | OR | lower | upper |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male* | ||||||

| Female | 0.247 | 0.117 | 0.035 | 1.281 | 1.023 | 1.624 |

| Carbonated drinks | ||||||

| < Once a week* | ||||||

| ≥Once a week | 0.262 | 0.120 | 0.029 | 1.299 | 1.028 | 1.643 |

| Mother's education | ||||||

| Primary* | ||||||

| Secondary | -0.043 | 0.126 | 0.734 | 0.958 | 0.749 | 1.266 |

| College and postgraduate | -0.431 | 0.175 | 0.013 | 0.650 | 0.461 | 0.914 |

| Constant | -1.358 | 0.204 | < 0.001 | 0.257 | ||

B: regression coefficient; SE: standard error; P: significance; OR: odds ratio

*parameters

Omnibus Tests of Model Coefficients: X2 = 22.105, df = 4, P < 0.001

Further analyses were done for the intrinsic and extrinsic acid contact by gender. There was no significant difference in the vomiting, heartburn or nausea, frequency of consumption of carbonated drinks, lemon tea, fruit juices and chewing gum between the genders (P = 0.382, 0.813, 0.613, 0.908, 0.801, and 0.767, respectively). Girls had a higher frequency of consumption of fruits and succade than boys (P < 0.001 and P = 0.014, respectively), while boys drank more sport drinks than girls (P < 0.001). Girls liked to suck or hold drinks in their mouths (P = 0.045); however, boys consumed a greater amount of acidic drinks than girls (P < 0.001).

Discussion

The prevalence of dental erosion of 27.3% in the current study was similar to the results of Caglar et al. [10] and Correr et al. [11], which indicated that 28% of 11-year-old children and 26% of 12-year-old children had permanent teeth affected by erosion, respectively. However, the prevalence ranging from 11.6%-100% was determined during recent surveys on the permanent dentition of children in different countries (Table 1). The variation in prevalence among these studies may be partially explained by differences in the diagnostic criteria and indices. Furthermore, socio-economic, cultural, and geographic factors could influence the outcome of prevalence data.

The central incisors in the upper and lower jaws were affected predominantly, followed by the lateral incisors. The first molars in the upper and lower jaws were less affected by erosion. The upper central incisors of children were usually reported to be frequently affected by erosion [12-14]. In our study, the lower central incisors were affected predominantly as well. Both the upper and lower incisors are located in the front of the oral cavity, which predisposes these teeth to erosion by extrinsic acids, such as acidic beverages. Moreover, the lower central incisors are the first erupting teeth, which are exposed to erosive challenges for a longer period of time. These may be the possible reasons for this finding.

The most frequently affected surface was the incisal or occlusal only (43.2%) for all teeth, followed by the labial and incisal/occlusal surfaces. Al-Majed et al. [8] also determined that 91% of dental erosion occurred on the incisal/occlusal surfaces of 12-14-year-old Saudi boys. The results of other surveys varied. For example, Auad et al. [12] and Mangueira et al. [15] reported that the palatal surfaces were the most affected. The consumption of erosive drinks and food was also shown to be strongly associated with erosion on the facial and occlusal surfaces, while severe palatal erosion occurred infrequently and were highly associated with chronic vomiting [16]. The predominant affected surfaces of erosion on the incisal/occlusal might result from these tooth surfaces being predisposed to physical impacts from mastication, which promotes the effect of erosion. Although distinguishing erosion from abrasion/attrition in the incisal/occlusal surfaces at the late stages of primary and permanent dentition is difficult, the dentition of 12-13-year-old children is during the early stages and the appearance of the incisal/occlusal surfaces as grooving/cupping is mainly due to erosion [17]. According to the differential diagnosis of dental erosion proposed by Gandara et al. [18], incisal surface contour appearing flat and shiny was defined as abrasion or attrition and was not included in the records in our study.

The severity of erosive lesions in our study demonstrated that the loss of enamel contour occurred most frequently (54.6%), and only a small proportion of tooth surfaces were affected with dentine exposure (1.4%). Several surveys found that all affected children of their study samples exhibited erosion with no exposed dentin. Peres et al. [19] reported that enamel loss was the most prevalent type of dental erosion for 12-year-old school children in Brazil. However, Al-Majed et al. [8] examined 862 Saudi Arabian boys 12-14 years of age, and 26% of these children exhibited pronounced dental erosion (erosion into the dentin or pulp). The frequent ingestion of carbonated soft drinks at nighttime could contribute to the high percentage of pronounced dental erosion in these Saudi boys.

Associations between dental erosion and the variables under study were investigated through processes of bivariate and multivariate analyses. A logistic regression analysis contributed to eliminate confounding factors that may mask an actual association or falsely demonstrate an apparent association between the study variables. The results of logistic regression analysis demonstrated that the gender of the children, frequency of consumption of carbonated drinks, and the level of education of the mothers were independent risk factors for dental erosion in school children of Southern China.

A significantly higher prevalence of dental erosion was found in girls (29.9%) than in boys (25.7%), which is in agreement with the results of previous investigation of 12-year-old Cuban children by Künzel et al. [20]. However, several surveys had found a significantly higher prevalence in boys than in girls [21,22], while Correr et al. [11] and Peres et al. [19] found no difference between the genders. In the present study, there was no significant difference in the frequency of consumption of carbonated drinks between the genders. Girls ate more succade and fruit, and were more likely to suck drinks than boys, but these variables had no significant difference between children with and without dental erosion. These results indicate that the reason of gender difference in the occurrence of dental erosion was not clear and further studies are necessary on this issue.

In the literature, the influence of socio-economic status is somewhat conflicting [9,23]. Children whose mothers had higher levels of education exhibited fewer lesions, which is in agreement with the study by Harding et al. [23]. Some studies reported no relationship between erosion and social class based on the occupation of the father and education of the mother [9]. In this study, the relationship between the level of education of the mother and the presence of erosion in the children may be due to the influence of the level of education on the lifestyle of the family. Mothers who had higher levels of education may have more knowledge of oral hygiene and better oral health habits.

The frequency of consumption of carbonated drinks was significantly related to dental erosion in the present study, which supported the results of previous surveys [24-26]. Daily fluid consumption is high due to the hotter climate in Guangzhou, particularly the consumption of carbonated soft drinks, which are becoming increasingly available at a reasonable cost and are popular due to their taste. Outputs of carbonated drinks in the Guangdong province increased to approximately 2 billion litres (22.7% of the total output in China) from January - October 2007, and ranked first of all 31 provinces/municipalities [27]. A recent study performed in seven cities of China, including Guangzhou, reported that carbonated drinks were still the predominant beverage preferred by school children. The frequency of consumption of carbonated drinks has increased greatly compared to 8 years ago [28]. There is a need for intervention programs aimed at the increasing consumption of soft drinks among school children in China, such as a media campaign, classroom workshops, school meal modification, and parental support.

The present study had limitations because of recall bias, the cross-sectional study design, and the relatively small sample size of suburban residents. Standardization of the indices and the teeth examined would facilitate the comparisons of different studies. More research should be done to determine the differences in tooth erosion and the main risk factors between urban and rural children. The prospective epidemiologic design will be of benefit for elucidation of the risk factors of the disease.

Conclusions

Our study provides evidence that dental erosion is becoming a significant problem in Chinese school children. Dental erosion should receive more attention that promotes awareness in dentists to make an early diagnosis and to evaluate the different etiologic factors that identify children at risk in China. Children who were female, consumed carbonated drinks once a week or more, and had mothers that were educated to the primary level tended to have more dental erosion. A strategy of offering preventive care, including more campaigns promoting a healthier lifestyle for those at risk of dental erosion, should be conducted for school children and their parents in China in order to reduce the medical burden of the government and families.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

PW: design of the study, performing the dental examination, data management and analysis, writing of the manuscript. HCL: design of the study, training and supervising fieldworkers, revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. JHC: design of the study, project co-ordination. HYL: design of the study, implementation and supervision of field work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Contributor Information

Ping Wang, Email: wangpww@126.com.

Huan Cai Lin, Email: Lin_hc@163.net.

Jian Hong Chen, Email: zcaswed@yahoo.com.cn.

Huan You Liang, Email: 333you@163.com.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Department of Education of Guangzhou, the presidents and teachers of the junior high schools who participated in the study, and the school children and parents for their co-operation.

References

- Linnett V, Seow WK. Dental erosion in children: a literature review. Pediatr Dent. 2001;23(1):37–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lussi A, Schaffner M, Jaeggi T. Dental erosion - diagnosis and prevention in children and adults. Int Dent J. 2007;57(6):385–398. [Google Scholar]

- Lussi A. Erosive tooth wear - a multifactorial condition of growing concern and increasing knowledge. Monogr Oral Sci. 2006;20:1–8. doi: 10.1159/000093343. full_text. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaechi BT, Higham SM. Dental erosion: possible approaches to prevention and control. J Dent. 2005;33(3):243–252. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2004.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guangzhou Municipal Statistics Bureau. General Survey. In: Guangzhou Municipal Statistics Bureau, editor. Guangzhou Statistical Yearbook 2008. Beijing: China Statistics Press; 2008. pp. 18–65. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JD. Dental erosion of nonindustrial origin. A clinical survey and classification. J Prosthet Dent. 1979;42(6):649–653. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(79)90196-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Sullivan EA. A new index for measurement of erosion in children. European Journal of Paediatric Dentistry. 2000;2(1):69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Majed I, Maguire A, Murray JJ. Risk factors for dental erosion in 5-6 year old and 12-14 year old boys in Saudi Arabia. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2002;30(1):38–46. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2002.300106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Malik MI, Holt RD, Bedi R. The relationship between erosion, caries and rampant caries and dietary habits in preschool children in Saudi Arabia. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2001;11(6):430–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caglar E, Kargul B, Tanboga I, Lussi A. Dental erosion among children in an Istanbul public school. J Dent Child (Chic) 2005;72(1):5–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correr GM, Alonso RC, Correa MA, Campos EA, Baratto-Filho F, Puppin-Rontani RM. Influence of diet and salivary characteristics on the prevalence of dental erosion among 12-year-old schoolchildren. J Dent Child (Chic) 2009;76(3):181–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auad SM, Waterhouse PJ, Nunn JH, Steen N, Moynihan PJ. Dental erosion amongst 13- and 14-year-old Brazilian schoolchildren. Int Dent J. 2007;57(3):161–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2007.tb00119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deery C, Wagner ML, Longbottom C, Simon R, Nugent ZJ. The prevalence of dental erosion in a United States and a United Kingdom sample of adolescents. Pediatr Dent. 2000;22(6):505–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Karim IA, Sanhouri NM, Hashim NT, Ziada HM. Dental erosion among 12-14 year old school children in Khartoum: a pilot study. Community Dent Health. 2007;24(3):176–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangueira DF, Sampaio FC, Oliveira AF. Association between socioeconomic factors and dental erosion in Brazilian schoolchildren. J Public Health Dent. 2009;69(4):254–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2009.00131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lussi A, Schaffner M, Hotz P, Suter P. Dental erosion in a population of Swiss adults. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1991;19(5):286–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1991.tb00169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millward A, Shaw L, Smith AJ, Rippin JW, Harrington E. The distribution and severity of tooth wear and the relationship between erosion and dietary constituents in a group of children. Int J Paediatr Dent. 1994;4(3):151–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.1994.tb00124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandara BK, Truelove EL. Diagnosis and management of dental erosion. J Contemp Dent Pract. 1999;15(1):16–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peres KG, Armenio MF, Peres MA, Traebert J, De Lacerda JT. Dental erosion in 12-year-old schoolchildren: a cross-sectional study in Southern Brazil. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2005;15(4):249–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2005.00643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Künzel W, Cruz MS, Fischer T. Dental erosion in Cuban children associated with excessive consumption of oranges. Eur J Oral Sci. 2000;108(2):104–109. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0722.2000.90720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugmore CR, Rock WP. The prevalence of tooth erosion in 12-year-old children. Br Dent J. 2004;196(5):279–282. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4811040. discussion 273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truin GJ, van Rijkom HM, Mulder J, van't Hof MA. Caries trends 1996-2002 among 6- and 12-year-old children and erosive wear prevalence among 12-year-old children in The Hague. Caries Res. 2005;39(1):2–8. doi: 10.1159/000081650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding MA, Whelton H, O'Mullane DM, Cronin M. Dental erosion in 5-year-old Irish school children and associated factors: a pilot study. Community Dent Health. 2003;20(3):165–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talebi M, Saraf A, Ebrahimi M, Mahmodi E. Dental erosion and its risk factors in 12-year-old school children in Mashhad. Shiraz Univ Dent J. 2009;9(Suppl 1):13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lussi A, Schaffner M. Progression of and risk factors for dental erosion and wedge-shaped defects over a 6-year period. Caries Res. 2000;34(2):182–187. doi: 10.1159/000016587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Sullivan EA, Curzon ME. A comparison of acidic dietary factors in children with and without dental erosion. ASDC J Dent Child. 2000;67(3):186–192. 160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- China Beverage Industry Association. Ranking of outputs of carbonated drinks by province (municipality) in China (Jan-Oct, 2007) The Beverage Industry. 2008;11(1):38. [Google Scholar]

- Duan YF, Fan YO, Fan JW, Pan SX, Hong JD, Zhang Q. et al. Status quo of beverage consumption among primary and secondary students in seven cities of China. Chinese Journal of Health Education. 2009;25(9):660–663. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Dlaigan YH, Shaw L, Smith A. Dental erosion in a group of British 14-year-old, school children. Part I: Prevalence and influence of differing socioeconomic backgrounds. Br Dent J. 2001;190(3):145–149. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4800908a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganss C, Klimek J, Giese K. Dental erosion in children and adolescents--a cross-sectional and longitudinal investigation using study models. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2001;29(4):264–271. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2001.290405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse PJ, Auad SM, Nunn JH, Steen IN, Moynihan PJ. Diet and dental erosion in young people in south-east Brazil. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2008;18(5):353–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2008.00919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]