Abstract

Objectives

To determine if genetic variation in genes in the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, the primary stress response system, influences susceptibility to developing musculoskeletal pain.

Methods

Pain and comorbidity data was collected at three time points in a prospective population-based cohort study. Pairwise tagging single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were selected and genotyped for seven genes. Genetic association analysis was carried out using zero-inflated negative binomial regression to test for association between SNPs and the maximum number of pain sites across the three time points in participants reporting pain, reported as proportional changes with 95% CIs. SNPs were also tested for association with chronic widespread pain (CWP) using logistic regression reporting odds ratios and 95% CI.

Results

A total of 75 SNPs were successfully genotyped in 994 participants including 164 cases with persistent CWP and 172 pain-free controls. Multiple SNPs in SERPINA6 were associated with the maximum number of pain sites; for example, each copy of the T allele of rs941601 was associated with having 16% (proportional change=1.16, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.28, p=0.006) more pain sites compared to participants with the CC genotype. SERPINA6 gene SNPs were also associated with CWP. Significant associations between the maximum number of pain sites and SNPs in the CRHBP and POMC genes were also observed and a SNP in MC2R was also associated with CWP. Associations between SNPs and comorbidity of poor sleep quality and depression explained some of the associations observed.

Conclusions

Genetic variation in HPA axis genes was associated with musculoskeletal pain; however, some of the associations were explained by comorbidities. Replication of these findings is required in independent cohorts.

Introduction

Musculoskeletal pain is common in the general population with up to 33% of people reporting low back pain (LBP) and approximately 11% reporting chronic widespread pain (CWP).1 Stress has been associated with musculoskeletal pain syndromes2 3 and psychological distress has been shown to be a strong predictor for the onset of CWP.4

The body's primary stress response system, the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, has been shown to be hyporesponsive in patients with fibromyalgia and patients with LBP.5 6 In a cohort of participants free of CWP those who went onto develop it showed reduced morning and increased evening levels of cortisol and higher levels of cortisol following a dexamethasone test (HPA axis suppression test). This suggests that individuals developing CWP show a blunting of the cortisol diurnal rhythm and a failure to suppress the HPA axis indicating a hypoactive HPA axis.

It has been hypothesised that the abnormal functioning of the HPA axis in musculoskeletal pain could be due stressors such as severe adverse events in early life, which have been shown to result in dysfunction of the HPA axis7 8 or altered levels of neurotransmitters such as reduced serotonin levels, as observed in fibromyalgia,9 10 which stimulates adrenocorticotrophin (ACTH) and corticotrophin releasing hormone (CRH) in response to stress. Genetic variation in genes key to HPA axis function could also play a role in musculoskeletal pain susceptibility. Individuals may respond inefficiently to stressors due to their genetic makeup, which may in turn render them more susceptible to developing musculoskeletal pain.

Twin studies have estimated that genetics explains 50% of the variance in pain syndromes.11 12 Pain thresholds, which are reduced in patients with CWP,13 have also been shown to have a genetic component,14, 15 however, one study did not find evidence of this.16 Attempts to identify the genes involved in CWP susceptibility and experimental pain sensitivity have been limited to date and problematic in their study design. The most prevalent problem is a lack of sufficient sample size to detect the likely modest effects of individual genes. Insufficient representation of the genetic variation within candidate genes and not considering the role of comorbidities are also common problems.17

In this study we aimed to determine if genetic variation within the HPA axis pathway genes CRH, CRH receptor 1 (CRHR1), CRH binding protein (CRHBP), the ACTH precursor pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) and its receptor (MC2R), the glucocorticoid receptor (NR3C1) and corticosteroid binding globulin (SERPINA6), is associated with susceptibility to musculoskeletal pain while accounting for the effects of comorbidities.

Methods

Participants

Pain and psychological data was collected at three time points over a 4-year period via a postal survey as part of a prospective population-based cohort study, EPIFUND (for ‘Epidemiology of Functional Disorders’). Participants aged 25–65 years were recruited from three primary care registers in the northwest of England.

Pain phenotype

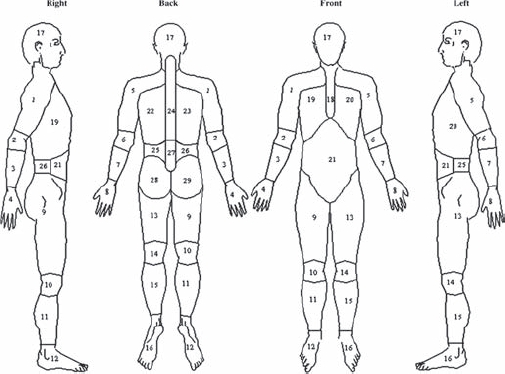

Participants were asked to indicate the site of any pain experienced for 1 day or longer in the past month on blank body manikins (front, back and sides) and to indicate if their pain had lasted for more than 3 months. Participants were classified two ways. (1) A ‘total pain’ score was constructed which ranged from 0 (no pain) to 29 (pain in all sites of the body) using the Manchester coding system18 19 (figure 1). For each participant the maximum number of pain sites across the three time points was determined. (2) CWP was classified using American College of Rheumatology criteria. Cases were defined as participants with CWP ≥2 time points and controls were pain free at all three time points.

Figure 1.

Pain sites used to calculate total pain score (Manchester coding).

Ascertainment of comorbidities

Anxiety, depression, psychological distress and sleep quality were assessed at baseline. Anxiety and depression were measured using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HAD) scale.20 The HAD questionnaire contains seven items on anxiety and seven items on depression in the last week. Each question is answered on a 4-point Likert scale (0–3) with total scores ranging from 0 to 21. Higher scores are indicative of a higher probability of having an anxiety or depressive disorder. The General Health Questionnaire 21 (12-item version) was used to assess levels of psychological distress. Scores range from 0 to 12 with higher scores indicating higher levels of psychological distress. Sleep quality was assessed using the Estimation of Sleep Problems Scale.22 A total of 4 items on recent sleep problems (sleep onset, sleep maintenance, early wakening and non-restorative sleep) were assessed on a 5-point scale (0–5) resulting in a total score of between 0 and 20, with higher scores indicating poorer sleep quality.

Genetic analysis

Participants were asked to provide a buccal swab sample for genetic analysis with informed consent. The sample collection and DNA extraction methods were adapted from Freeman et al.23

Pairwise tagging single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs, r2≥0.8) with a minor allele frequency ≥5% were selected for CRH, CRHBP, CRHR1, POMC, MC2R, NR3C1 and SERPINA6 and their 10 kb flanking regions using Tagger.24 SNPs were genotyped using Sequenom MassARRAY technology following the manufacturer's instructions (http://www.sequenom.com).

Sample and assay quality control thresholds were set to 90%. Allele frequencies were checked for consistency with HapMap data and tested for deviation from Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE) and excluded from the analysis if p≤0.01 in the total population. Linkage disequilibrium (LD) between SNPs was examined using Haploview version 3.32.25

Statistical analysis

Analysis was conducted using STATA V.9.2 (Stata, College Station, Texas, USA). p Values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Total number of pain sites

The distribution of the maximum number of pain sites was positively skewed with 17% of participants reporting no pain. To account for this and overdispersion of the data a zero-inflated negative binomial regression (ZINB) model was used. ZINB tests whether a SNP is associated with the odds of reporting no pain (logit) as well as testing for association between a SNP and the maximum number of pain sites in participants who have reported pain (negative binomial). Participants reporting pain can range from having acute pain at a single site to chronic pain at multiple sites, therefore, treating them as a referent group to determine if a SNP is associated with the odds of reporting no pain is a crude analysis and so the results of the logit portion of the model are not reported. Initially a test for trend was conducted. Where there was no evidence of a trend association, recessive (AA and Aa vs aa) and dominant (AA vs Aa and aa) models of association were tested. The results of the negative binomial portion of the model are reported as the proportional change in the number of pain sites with 95% CIs.

The effects of four variables; depression, anxiety, psychological distress and sleep quality on the maximum number of pain sites was assessed using ZINB and only depression and sleep were independently associated (data not shown). Therefore, SNPs significantly associated with the maximum number of pain sites were tested for association with HAD depression score (using negative binomial regression) and sleep quality score (using ZINB). Where there was evidence of an association between a SNP and depression or sleep quality the model was adjusted for the associated comorbidity (depression and/or sleep) to determine if the SNP associations with the maximum number of pain sites were occurring independently of these comorbid factors. Interactions between SNPs (associated with the maximum number of pain sites) and depression and sleep were also tested to determine if they were acting as effect modifiers on the associations observed with pain.

CWP

SNPs were tested for association with CWP using the Cochran–Armitage trend test. Where there was no evidence of a trend association, recessive and dominant models of association were tested using a χ2 test. Logistic regression was used to estimate odds ratios (OR) and 95% CI.

Haplotype structure was determined using the confidence bounds method in Haploview.26 The expectation–maximisation algorithm was used to estimate haplotype frequencies. The overall distribution of haplotypes was compared between patients with CWP and pain-free controls using a χ2 test. The frequency of each individual haplotype was also compared to the combined frequency of the other haplotypes between cases and controls using the χ2 test. Haplotype inference and association testing was conducted in PLINK.27

Depression and sleep were independently associated with CWP (data not shown). Significant associations with CWP were adjusted for depression and/or sleep if there was evidence of association between the SNP and depression and/or sleep, to determine if the associations were occurring independently of these comorbid factors. Interactions between SNPs (associated with CWP) and depression and sleep were also tested to determine if they were moderating the relationship between the SNP and CWP.

Results

Participants

DNA samples were obtained from 1189 participants with pain data at all time points. Samples from 195 (16%) participants were not successfully genotyped for 90% of the SNPs and were excluded from the analysis. The characteristics of the resulting 994 participants are given in table 1. The nested case-control study of CWP consisted of 164 cases and 172 controls. HAD depression and sleep quality scores in the cases were significantly (Mann–Whitney U test, p<0.001) higher than in the controls (table 1).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| CWP analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total population | Cases | Controls | |

| n | 994 | 164 | 172 |

| Median age (95% CI) | 50.9 (49.8 to 52.0) | 52.6 (50.3 to 53.9) | 48.5 (46.4 to 51.6) |

| % Female | 58 | 66 | 57 |

| Median depression score (95% CI) | 3 (2 to 3) | 5 (4 to 6) | 2 (1 to 2) |

| Median sleep score (95% CI) | 5 (5 to 5) | 11 (10 to 13) | 3 (2 to 4) |

CWP, chronic widespread pain.

Genotyping

Of the 88 SNPs selected, 75 were successfully genotyped and in HWE (p>0.01). Coverage of HapMap SNPs (r2<0.8) was 100% for POMC, 92% for CRHR1 and MC2R, 87% for SERPINA6, 84% for NR3C1, 67% for CRH and 60% for CRHBP.

Total number of pain sites

Four SNPs spanning 5′ to intron 4 of SERPINA6 showed association with the maximum number of pain sites in participants reporting pain. rs941601 and rs746530 both showed a significant trend for an increase in the maximum number of pain sites, in participants reporting pain, with the number of copies of the minor allele. A significant increase in the maximum number of pain sites was observed in participants with two copies of the minor allele (recessive effect) for rs11627241 and rs1998056 compared to participants with zero copies or one copy (table 2).

Table 2.

Significant associations with the maximum number of pain sites in participants reporting pain

| Gene | SNP | Genotype | n | Proportional change (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SERPINA6 | rs941601 | CC | 604 | Reference | – |

| CT | 202 | 1.16 (1.04 to 1.28) | 0.006 | ||

| TT | 16 | 1.34 (1.09 to 1.64) | 0.006 | ||

| rs11627241 | CC and CT | 772 | Reference | – | |

| TT | 50 | 1.27 (1.03 to 1.57) | 0.026 | ||

| rs1998056 | CC and CG | 671 | Reference | – | |

| GG | 149 | 1.18 (1.03 to 1.34) | 0.017 | ||

| rs746530 | GG | 352 | Reference | – | |

| GA | 360 | 1.10 (1.02 to 1.19) | 0.011 | ||

| AA | 101 | 1.21 (1.05 to 1.41) | 0.011 | ||

| POMC | rs3769671 | AA | 740 | Reference | – |

| AC and CC | 65 | 0.81 (0.67 to 0.99) | 0.040 | ||

| CRHBP | rs1875999 | TT | 373 | Reference | – |

| TC and CC | 444 | 1.12 (1.01 to 1.24) | 0.036 |

SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

In participants reporting pain, having one or two copies of the minor allele of rs3769371 in POMC was associated with a reduction in the maximum number of pain sites compared to having zero copies (dominant effect). Conversely, rs1875999 in CRHBP was associated with an increased maximum number of pain sites in participants with one or two copies of the minor allele compared to participants with zero copies (table 2) and also showed evidence of association with an increased likelihood of depression (proportional change=1.10, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.20, p=0.047 for each copy of the minor allele) and poor sleep quality (proportional change=1.15, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.25, p=0.001 for each copy of the minor allele in participants reporting sleep problems (sleep quality score ≥1)). Adjusting the association between the maximum number of pain sites and rs1875999 for HAD depression score and sleep quality rendered the association non-significant (proportional change=1.01, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.11, p=0.860).

There was no evidence of interaction between the SNPs, associated with pain, and depression or sleep on the maximum number of pain sites. There was also no evidence of association between the maximum number of pain sites in participants reporting pain and SNPs genotyped in CRH, CRHR1, MC2R and NR3C1.

CWP

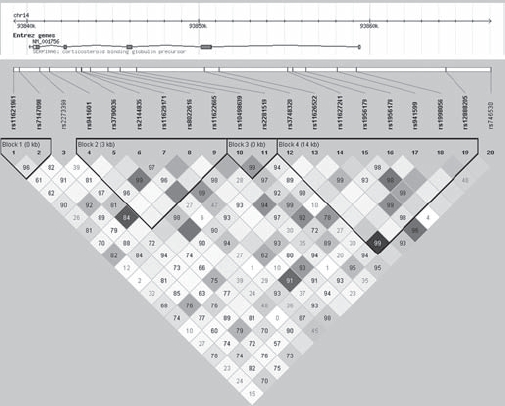

Two SNPs in SERPINA6 were significantly associated with CWP. Rs941601 and rs8022616 showed a significant trend for increasing and decreasing the odds of having CWP with the number of copies of the minor allele, respectively (table 3). These two SNPs are located within a 3-kb haplotype block containing four other SNPs spanning intron 3 to intron 4 (figure 2). Six common haplotypes were identified in this block. Although the overall haplotype distribution did not significantly differ between cases and controls (p=0.09), the haplotype containing the minor T allele of rs941601 and the common A allele of rs8022616 was significantly more frequent in cases (16%) than controls (10%), p=0.041. Conversely, the haplotype containing the common C allele of rs941601 and the variant G allele of rs8022616 was significantly more common in controls (13%) than cases (7%), p=0.019 (table 4).

Table 3.

Significant associations with CWP

| n (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | SNP | Genotype | Cases | Controls | OR (95% CI) | p Value |

| SERPINA6 | rs941601 | CC | 117 (71) | 138 (81) | Reference | – |

| CT | 43 (26) | 31 (18) | 1.61 (1.02 to 2.55) | 0.040 | ||

| TT | 4 (3) | 2 (1) | 2.59 (1.03 to 6.52) | 0.040 | ||

| rs8022616 | AA | 142 (87) | 131 (77) | Reference | – | |

| AG | 20 (12) | 36 (21) | 0.58 (0.34 to 0.97) | 0.037 | ||

| GG | 2 (1) | 3 (2) | 0.33 (0.12 to 0.93) | 0.037 | ||

| MC2R | rs11661134 | GG | 132 (84) | 158 (92) | Reference | – |

| AG and AA | 26 (16) | 14 (8) | 2.22 (1.12 to 4.43) | 0.023 | ||

CWP, chronic widespread pain; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

Figure 2.

Linkage disequilibrium and haplotype block structure of SERPINA6 in the study population. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) genotyped and their position in SERPINA6 are shown with pairwise linkage disequilibrium (LD; colour coded by r2 (white=0, black=1) and numbered by D′ (if no number D′=1)) and haplotype block structure as defined by the confidence bounds method.26

Table 4.

Haplotype analysis of SERPINA6 with CWP

| Distribution of individual haplotypes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combination of SNPs | Overall distribution p value | Haplotype | Case % | Control % | p Value |

| rs941601–rs3790036–rs2144835–rs11629171–rs8022616–rs11622665 | 0.09 | CACCAG | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.881 |

| CATTGA | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.019 | ||

| CGTTAA | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.651 | ||

| CACCAA | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.762 | ||

| TATCAA | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.041 | ||

| CATCCA | 0.26 | 0.23 | 0.401 | ||

CWP, chronic widespread pain.

The SERPINA6 SNP rs8022616 showed evidence of association with a reduced likelihood of depression (proportional change=0.80, 95% CI 0.69 to 0.92, p=0.002 for each copy of the minor allele) and improved sleep quality (proportional change=0.86, 95% CI 0.76 to 0.98, p=0.02) for each copy of the minor allele in participants reporting sleep problems. Adjusting the association between rs8022616 and CWP for HAD depression score and sleep quality score rendered it non-significant (p=0.275) but the odds of having CWP was still reduced, proportional change=0.69, 95% CI 0.35 to 1.35.

A single SNP in MC2R, rs11661134, was associated with an increased odds of having CWP in participants with one or two copies of the minor A allele compared to participants with zero copies (OR=2.24, 95% CI 1.14 to 4.39, p=0.02). There was no evidence of interaction between SNPs associated with CWP with depression or sleep on CWP susceptibility and no evidence of association with SNPs in CRH, CRHR1, CRHBP, POMC or NR3C1 and CWP.

Discussion

Here we report the findings of the first population-based study to examine the role of HPA axis genes in musculoskeletal pain susceptibility. The findings suggest that genetic variation in the HPA axis, most notably in the corticosteroid binding globulin gene (SERPINA6), has a role in susceptibility to CWP and musculoskeletal pain in the population, however, comorbidities seem to explain some of the associations observed.

Multiple SNPs in SERPINA6 were associated with the maximum number of pain sites in participants reporting pain and two SNPs in this gene, rs941601 and rs8022616, also showed evidence of association with CWP and are located within a single haplotype block. However, no effect of the haplotype over and above the individual effects of the SNPs was observed due to there being no evidence of recombination between the SNPs (D'=1). Genetic associations were also observed between a SNP in MC2R and CWP, and between SNPs in CRHBP and POMC with the maximum number of pain sites in participants reporting pain.

Genetic variation in the HPA axis may influence other pain-related factors such as psychological comorbidities and sleep quality. Consequently SNPs associating with pain were tested for association with these factors. The minor allele of the SERPINA6 SNP, rs8022616, was associated with a reduced likelihood of developing a depressive disorder and increased sleep quality. The minor C allele of the CRHBP SNP, rs1875999, was associated with increased likelihood of developing a depressive disorder and reduced sleep quality. This is in contrast to a previous report in which the common T allele of rs1875999 was significantly associated with increased odds of having major depressive disorder in a Swedish population.28 These factors appear to explain the associations between these two SNPs and pain as they became non-significant after adjustment for them; however, a reduced odds of having CWP was still observed in participants with the minor allele of rs8022616. Genetic variation in SERPINA6 could influence pain and psychological factors independently as previous findings from the EPIFUND study showed that HPA axis dysfunction increases the odds of developing CWP independently of depression and other psychological factors.29

Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) shares some similarity in its aetiology and symptoms with CWP and evidence of hypofunction of the HPA axis in CFS has been reported.30 Therefore, the same genes may be associated with CFS and pain susceptibility. Polymorphisms in NR3C1 have previously been associated with CFS31 and shown to distinguish between different classes of CFS.32

However, there was no evidence of association between SNPs in NR3C1 and musculoskeletal pain in this study. The most likely explanation for this is the modest sample size most notably in the previous studies but also in this study. Alternatively the previous genetic associations observed with CFS may be specific to CFS rather than being genetic predictors for functional somatic syndromes.

SNPs in NR3C1 have also been shown to influence cortisol levels.33 34 However, none of the SNPs that we observed in association with pain here have as yet been tested for association with HPA axis function. This will be an important step in order to determine how the SNPs may be functioning via the HPA axis to influence pain susceptibility.

One of the strengths of this study is the phenotypes used. Cases had reported CWP at at least two of the three time points, providing a robust phenotype, and were compared to a pain-free control group to avoid erroneous associations due to the presence of non-persistent CWP, WP or regional pain disorders which may also be influenced by genetic variation in the HPA axis. However, this results in a limited sample size. A novel method was used to quantify pain by creating a composite score of the number of body regions, from 0 to 29, making it possible to examine the relationship between genetic variation and musculoskeletal pain in the entire study population thus increasing statistical power.

One limitation of the study is that ethnicity of participants was not determined; however, participants were derived from predominantly white Caucasian geographic areas. Another limitation of our study is that due to limited power we have chosen not to correct for multiple testing. Indeed correcting for the number of effective tests, accounting for LD between SNPs, using the methodology proposed by Li and Ji35 would result in a p value cut-off of 0.00037; none of the associations observed reached this level of significance. However, this method of correction is comparatively stringent and may result in false negatives if applied. To be certain whether these are true pain susceptibility loci or false positives, independent replication of these findings in larger cohorts is essential.

It was anticipated that similar findings would be detected with the two pain outcomes as the patients with CWP also tend to have a high number of pain sites. There is some consistency between the findings of the CWP and maximum number of pain sites analysis but also some discrepancies. This may be explained by the reduced power in the CWP analysis or because the maximum pain score is capturing acute and chronic pain which may not be influenced by the same genetic factors.

In conclusion, we report the first evidence that genetic variation in the primary stress response system influences susceptibility to musculoskeletal pain in a general population sample. However, the associations reported are modest, sometimes explained by psychological comorbidity and require replication in a large independent cohort to determine whether they play a role in the aetiology of musculoskeletal pain.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants and staff at the three general practices who contributed to the EPIFUND study. They also thank the administrative and laboratory staff at the arc Epidemiology Unit for their contributions to the project.

Footnotes

Funding: The study was funded by a grant from the Arthritis Research Campaign, grant Ref: 17552.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: This study was conducted with the approval of the local research ethics committee and the University of Manchester.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Croft P, Rigby AS, Boswell R, et al. The prevalence of chronic widespread pain in the general population. J Rheumatol 1993;20:710–13 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoogendoorn WE, Bongers PM, de Vet HC, et al. High physical work load and low job satisfaction increase the risk of sickness absence due to low back pain: results of a prospective cohort study. Occup Environ Med 2002;59:323–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diepenmaat AC, van der Wal MF, de Vet HC, et al. Neck/shoulder, low back, and arm pain in relation to computer use, physical activity, stress, and depression among Dutch adolescents. Pediatrics 2006;117:412–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McBeth J, Macfarlane GJ, Benjamin S, et al. Features of somatisation predict the onset of chronic widespread pain: results of a large population-based study. Arthritis Rheum 2001;44:940–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crofford LJ, Pillemer SR, Kalogeras KT, et al. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis perturbations in patients with fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum 1994;37:1583–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Griep EN, Boersma JW, Lentjes EG, et al. Function of the hypothalamic-pituitaryadrenal axis in patients with fibromyalgia and low back pain. J Rheumatol 1998;25:1374–81 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van VE, Scarpa A. The effects of child maltreatment on the hypothalamic-pituitaryadrenal axis. Trauma Violence Abuse 2004;5:333–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weissbecker I, Floyd A, Dedert E, et al. Childhood trauma and diurnal cortisol disruption in fibromyalgia syndrome. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2006;31:312–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolfe F, Russell IJ, Vipraio G, et al. Serotonin levels, pain threshold, and fibromyalgia symptoms in the general population. J Rheumatol 1997;24:555–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Russell IJ, Vipraio GA, Lopez YG. Serum serotonin in fibromyalgia syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis and healthy normol controls. Arthritis Rheum 1993;36:S222 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kato K, Sullivan PF, Evengård B, et al. Importance of genetic influences on chronic widespread pain. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:1682–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacGregor AJ, Andrew T, Sambrook PN, et al. Structural, psychological, and genetic influences on low back and neck pain: a study of adult female twins. Arthritis Rheum 2004;51:160–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolfe F, Ross K, Anderson J, et al. Aspects of fibromyalgia in the general population: sex, pain threshold, and fibromyalgia symptoms. J Rheumatol 1995;22:151–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Norbury TA, MacGregor AJ, Urwin J, et al. Heritability of responses to painful stimuli in women: a classical twin study. Brain 2007;130:3041–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nielsen CS, Stubhaug A, Price DD, et al. Individual differences in pain sensitivity: Genetic and environmental contributions. Pain 2007;136:21–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.MacGregor AJ, Griffiths GO, Baker J, et al. Determinants of pressure pain threshold in adult twins: evidence that shared environmental influences predominate. Pain 1997;73:253–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Limer KL, Nicholl BI, Thomson W, et al. Exploring the genetic susceptibility of chronic widespread pain: the tender points in genetic association studies. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47:572–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacFarlane GJ, Croft PR, Schollum J, et al. Widespread pain: is an improved classification possible? J Rheumatol 1996;23:1628–32 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hunt IM, Silman AJ, Benjamin S, et al. The prevalence and associated features of chronic widespread pain in the community using the ‘Manchester’ definition of chronic widespread pain. Rheumatology (Oxford) 1999;38:275–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldberg D. a User’s Guide to the General Health Questionnaire. Windsor: NFER-Nelson, 1988 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jenkins CD, Stanton BA, Niemcryk SJ, et al. A scale for the estimation of sleep problems in clinical research. J Clin Epidemiol 1988;41:313–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freeman B, Powell J, Ball D, et al. DNA by mail: an inexpensive and noninvasive method for collecting DNA samples from widely dispersed populations. Behav Genet 1997;27:251–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Bakker PI, Yelensky R, Pe’er I, et al. Efficiency and power in genetic association studies. Nat Genet 2005;37:1217–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, et al. Haploview: analysis and visualisation of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics 2005;21:263–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gabriel SB, Schaffner SF, Nguyen H, et al. The structure of haplotype blocks in the human genome. Science 2002;296:2225–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, et al. PLINK: a tool set for wholegenome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet 2007;81:559–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Claes S, Villafuerte S, Forsgren T, et al. The corticotropin-releasing hormone binding protein is associated with major depression in a population from Northern Sweden. Biol Psychiatry 2003;54:867–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McBeth J, Silman AJ, Gupta A, et al. Moderation of psychosocial risk factors through dysfunction of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal stress axis in the onset of chronic widespread musculoskeletal pain: findings of a population-based prospective cohort study. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:360–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Den EF, Moorkens G, Van HB, et al. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function in chronic fatigue syndrome. Neuropsychobiology 2007;55:112–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rajeevan MS, Smith AK, Dimulescu I, et al. Glucocorticoid receptor polymorphisms and haplotypes associated with chronic fatigue syndrome. Genes Brain Behav 2007;6:167–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith AK, White PD, Aslakson E, et al. Polymorphisms in genes regulating the HPA axis associated with empirically delineated classes of unexplained chronic fatigue. Pharmacogenomics 2006;7:387–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stevens A, Ray DW, Zeggini E, et al. Glucocorticoid sensitivity is determined by a specific glucocorticoid receptor haplotype. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004;89:892–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rautanen A, Eriksson JG, Kere J, et al. Associations of body size at birth with latelife cortisol concentrations and glucose tolerance are modified by haplotypes of the glucocorticoid receptor gene. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006;91:4544–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li J, Ji L. Adjusting multiple testing in multilocus analyses using the eigenvalues of a correlation matrix. Heredity 2005;95:221–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]