Abstract

Loci involved in local adaptation can potentially be identified by an unusual correlation between allele frequencies and important ecological variables or by extreme allele frequency differences between geographic regions. However, such comparisons are complicated by differences in sample sizes and the neutral correlation of allele frequencies across populations due to shared history and gene flow. To overcome these difficulties, we have developed a Bayesian method that estimates the empirical pattern of covariance in allele frequencies between populations from a set of markers and then uses this as a null model for a test at individual SNPs. In our model the sample frequencies of an allele across populations are drawn from a set of underlying population frequencies; a transform of these population frequencies is assumed to follow a multivariate normal distribution. We first estimate the covariance matrix of this multivariate normal across loci using a Monte Carlo Markov chain. At each SNP, we then provide a measure of the support, a Bayes factor, for a model where an environmental variable has a linear effect on the transformed allele frequencies compared to a model given by the covariance matrix alone. This test is shown through power simulations to outperform existing correlation tests. We also demonstrate that our method can be used to identify SNPs with unusually large allele frequency differentiation and offers a powerful alternative to tests based on pairwise or global FST. Software is available at http://www.eve.ucdavis.edu/gmcoop/.

LOCAL adaptation to divergent environments can lead to dramatic differences in average phenotype between populations of the same species. Such variation offers particularly compelling evidence of natural selection when it is correlated with variation in environmental factors over multiple independent geographic regions and/or species. For example, in warm-blooded species, individuals at higher latitudes tend to be smaller than those found at the equator (Bergmann 1847; Allen 1877) and birds in humid climates tend to be darker in pigmentation than those in drier habitats (Gloger 1833). There are many other examples of phenotypic adaptations to local environments, including cyptic pigmentation in deer mice (Sumner 1929; Mullen and Hoekstra 2008), body size and pigmentation gradients in Drosophila (e.g., Coyne and Beecham 1987; Huey et al. 2000; Pool and Aquadro 2007), skin pigmentation clines in humans (Relethford 1997), and toxic soil resistance in plants (Jain and Bradshaw 1966). Such patterns were among the earliest types of evidence used to demonstrate the action of local adaptation as a force driving phenotypic differences between populations within a species (e.g., Huxley 1939; Mayr 1942).

Correlations between phenotype and environment may be mirrored at the level of individual genetic polymorphisms, where at some loci, allele frequencies strongly differentiate populations that live in different environments. Such correlations can arise when selection pressures exerted by the environmental variable are sufficiently divergent between geographic locations, such that differences in allele frequency can be maintained in the face of gene flow (e.g., Haldane 1948; Slatkin 1973; Nagylaki 1975; Lenormand 2002). The study of geographic patterns of genetic variation has a long history, with some of the earliest work on genetic polymorphism being the study of clines in the frequency of cytologically visible inversion polymorphisms (Dobzhansky 1948). Other examples include loci involved in adaptations to high altitude (Storz et al. 2007; McCracken et al. 2009), pigmentation (Hoekstra et al. 2004), and life-history changes (Schmidt et al. 2008). One particularly impressive example of adaptive response to selection is provided by the ADH locus in Drosophila melanogaster, alleles of which show a strong gradient with latitude (Berry and Kreitman 1993). It has been observed that the ADH cline is quickly reestablished after the introduction of the species onto different continents and that it responds quickly to climate change (Umina et al. 2005).

The advent of genome-wide data sets with individuals from many populations, across a wide geographic range (e.g., Nordborg et al. 2005; Jakobsson et al. 2008; Li et al. 2008; Auton et al. 2009), allows investigators to obtain a systematic view of the processes shaping local adaptation and to gain valuable insights into the genetic and ecological basis of adaptation and speciation. It can also provide support for adaptive explanations for phenotypic variation, for example, suggesting an impact of selection on variation that is linked to human metabolic diseases (Thompson et al. 2004; Young et al. 2005; Hancock et al. 2008, 2010; Pickrell et al. 2009).

Some of the earliest tests of selection on genetic markers were based on identifying loci that showed extreme allele frequency differences among populations (Cavalli-Sforza 1966; Lewontin and Krakauer 1973), using statistics such as FST, and there are now a range of methods predicated on this idea (e.g., Beaumont and Balding 2004; Foll and Gaggiotti 2008). Our goal here differs, as we seek to identify loci where the allele frequencies show unusually strong correlations with one or more environmental variables. Such loci may be under selection driven by those environmental factors or correlated selection pressures. However, this goal is complicated by the fact that allele frequencies are typically correlated among closely related populations; since such populations tend to be geographically proximate they often share environmental variables (see Novembre and Di Rienzo 2009 for a recent discussion). This means that neighboring populations can rarely be treated as independent observations. Thus, a naive test of correlation between population frequency and an environmental variable will often have a high false positive rate. This situation is somewhat analogous to the reduced number of independent contrasts when comparing traits across species due to the shared phylogeny (Felsenstein 1985). The nonindependence of populations is also known to be an issue when using FST as a summary statistic to identify selected loci (Robertson 1975; Excoffier et al. 2009).

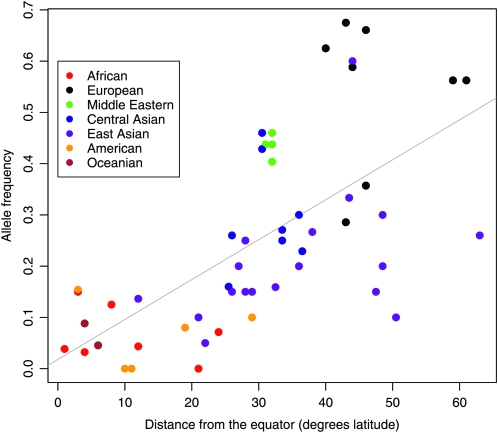

To illustrate the problem, Figure 1 shows the allele frequencies of a SNP in a series of 52 human populations, as a function of the distance of each population from the equator (Figure 1 is redrawn from a similar plot in Thompson et al. 2004). The SNP is AGT M235T and the allele that increases in frequency with latitude is known to reduce sodium retention (Lifton et al. 1993), which may have been selectively favored in cooler northern climes. However, as is apparent in Figure 1, populations cluster by broad geographic region for both allele frequency and distance from the equator. Thus, the correlation between allele frequency and environmental variable is clearly supported by far fewer independent observations than the 52 points plotted in Figure 1. Moreover, it is not clear how much of the variation in allele frequency in Figure 1 is due to sampling error in some of the smaller samples or genetic drift. For example, are the low allele frequencies in Oceania—which support an environmental correlation—simply due to sampling error or genetic drift?

Figure 1.—

The distance from the equator for each of 52 human populations, plotted against sample allele frequencies for the SNP AGT M235T in each population. The points are colored according to the geographic region each population belongs to, following region definitions of Rosenberg et al. (2002). The data were generated using HGDP samples by Thompson et al. (2004) and are replotted on the basis of a figure in that article.

In this article, we develop a model to overcome these difficulties by accounting for differences in sample sizes and for the null correlation of allele frequencies across populations when testing for correlation between an environmental variable and allele frequencies. To do this, we use a set of control loci to estimate a null model of how allele frequencies covary across populations. We can then test whether the correlation seen between the allele frequencies at a marker of interest and an environmental variable is greater than expected given this null model. We concentrate on markers such as SNPs that are codominant and usually biallelic, but we note in the discussion how the model can be extended to other types of markers. The method developed here can be applied to continuous or discrete environmental variables. We demonstrate the method by applying it to genome-wide SNP data from humans. Elsewhere we have applied this method to human genome-wide SNP data, for a range of environmental and ecological variables (Hancock et al. 2008, 2010).

METHODS

We develop a model for the joint allele frequencies across populations. One way to do so would be to use a fully explicit model of demographic history, but such models are very difficult to parameterize and to fit for so many populations. Instead, we intentionally avoid using an explicit model of the historical relationships between populations and opt for a flexible, less model-based parameterization. Under our null model, the population allele frequency in each population may deviate away from an ancestral (or global) allele frequency due to genetic drift. Populations covary in the deviation that they take, allowing some populations to be more closely related genetically to each other due to the effects of shared population history or gene flow. Thus, our null model is specified by the covariance structure of allele frequencies across populations. To estimate this covariance structure, we assume that a transform of the population frequency of an allele across populations has a multivariate normal distribution. We estimate the covariance matrix of this normal distribution using our control SNPs. This provides the null model that we use to assess the correlation between the environmental variable and allele frequencies at a SNP of interest.

Null model:

Suppose that L unlinked SNPs have been typed in K populations. First we estimate the null model using all L of these markers; if the number of markers is very large, then to improve computational speed we may estimate the null model using a large random subset L of all the markers typed. (As discussed below, we find that the null model parameters estimated from different subsets of the data are highly consistent, provided that L is large enough.) In some applications, the markers that we are interested in testing for environmental correlations may be among the L (since we expect that a small fraction of selected loci will have little impact on the parameter estimates for the null model). Alternatively, the L may represent a set of well-matched control markers (see Hancock et al. 2008, 2010, for discussion).

The data at locus l consist of the number of times we see alleles 1 and 2, respectively, in each of the k populations. (The two alleles are labeled arbitrarily.) Then let nl = {n1l, … ,nKl} be the observed counts of allele 1 and ml = {m1l, · · · , mKl} be the counts of allele 2, in populations  ; hence the total number of allele copies genotyped at locus l in population k is nkl + mkl. This notation ignores any missing data at site l, which is appropriate if we assume that any missing data are missing at random with respect to genotype. The population allele frequencies at locus l will be denoted by x1l, … , xKl, and we assume that the observed counts of each allele are the result of binomial draws from these frequencies, independently for each k and l. The population allele frequencies are unknown in advance, and must be estimated from the data.

; hence the total number of allele copies genotyped at locus l in population k is nkl + mkl. This notation ignores any missing data at site l, which is appropriate if we assume that any missing data are missing at random with respect to genotype. The population allele frequencies at locus l will be denoted by x1l, … , xKl, and we assume that the observed counts of each allele are the result of binomial draws from these frequencies, independently for each k and l. The population allele frequencies are unknown in advance, and must be estimated from the data.

We aim to construct a model for the joint distribution of allele frequencies across the k populations. If these frequencies were not constrained to be between zero and one, it would be natural to model the population allele frequencies of a SNP across populations as being multivariate normal. To overcome the constrained nature of allele frequencies, we follow Nicholson et al. (2002) by assuming that the population allele frequency in a subpopulation, xkl, is normally distributed around an ancestral allele frequency ɛl (0 < ɛl < 1), but that the densities of xkl above 1 and below 0 are replaced with point masses on 1 and 0, respectively. Further, we adopt the assumption of Nicholson et al. (2002) that, for a particular subpopulation, the variance of this normal distribution is a product of a factor that is constant across loci multiplied by a locus-specific term: i.e., ɛl(1 − ɛl). This model was introduced to describe a pure drift model where the allele frequency within each population independently drifts from the ancestral allele frequency. The normal distribution was chosen because, when the frequency of an allele in the current generation is ɛ, the binomial sampling of the next generation can be approximated as the frequency in the next generation being ∼N(ɛl, ɛl(1 − ɛl)/(2Ne)) (in a population of effective size Ne). Thus, after τ generations of genetic drift, the distribution of allele frequency can be approximated as ∼N(y, Ckɛl(1 − ɛl)), where Ck = τ/(2Ne) is shared across loci, for τ ≪ Ne (Nicholson et al. 2002). The estimate Ck can also be viewed as a model-based population-specific estimate of FST, a relationship that holds for low values of Ck (Nicholson et al. 2002), a point that we return to briefly in the discussion.

Put in notational form, we assume that the population allele frequency xkl is related by a simple transform g() to a surrogate population allele variable θkl that is not constrained to be between 0 and 1:

|

(1) |

Therefore, for a locus l there is a set of θl = θ1l, … , θKl, where θkl has a marginal distribution ∼N(ɛl, ɛl(1 – ɛl)Ck) (Nicholson et al. 2002). The point masses in the distribution of xkl on zero and one (θkl ≤ 0 and θkl ≥ 1) represent the probability that the allele has been lost or fixed in the kth population, respectively.

Since we want to explicitly estimate the covariance in allele frequencies across populations, rather than assuming independent normally distributed variables across populations (as in Nicholson et al. 2002), we assume that the θl have a multivariate normal distribution

|

(2) |

where N(μ, V) is a multivariate normal distribution with mean μ and variance–covariance matrix V. When the off-diagonal components of Ω are set to zero, this model is the same as that of Nicholson et al. (2002) with minor differences in parameterization.

We can write the joint posterior of the parameters (θl, Ω, ɛl) at a single locus l up to a normalizing constant, as

|

(3) |

where P(Ω) and P(ɛl) are priors on the covariance matrix and ancestral frequency, respectively. Our prior on the ancestral allele frequency ɛ is symmetric Beta with parameter λ. For the results presented here, we set λ = 1, reflecting the fact that the SNPs have been ascertained to be polymorphic. But in practice the choice of λ makes relatively little difference, as when there are many populations, there is reasonably good information about the parameter ɛ; we note, however, that ɛ is generally “biased” toward matching the allele frequency of geographic regions with large numbers of populations sampled.

Our prior on the variance–covariance matrix Ω, P(Ω), is somewhat more complicated, as it must have weight only on the set of positive definite matrices (a requirement of the multivariate normal distribution). We use the inverse Wishart prior, which is often used as a prior on variance–covariance matrices because it is the conjugate prior for the variance–covariance matrix of a multivariate normal. The inverse Wishart is parameterized by W(ρR−1,ρ), where R is the prior K × K shape matrix and ρ (where ρ ≥ K) is a parameter controlling the strength of the prior (i.e., how much the posterior draws of the covariance matrix resemble the shape matrix). To make the prior as weak as possible we set ρ = K. We set R to be the identity matrix (i.e., Rij = 1 if i = j, and 0 otherwise), but investigate the effect of this choice of prior later.

The covariance matrix is shared over loci, and so the joint posterior for all the loci is

|

(4) |

We use Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) to explore the posterior of the covariance matrix and other parameters. Our MCMC scheme is presented in appendix a.

Alternative model:

Having estimated a null model of how SNP frequencies vary across populations (i.e., the posterior of the covariance matrix Ω), we now use this model to investigate whether allele frequencies at a SNP of interest are significantly correlated with an environmental variable Y. To do this, we allow the allele frequency, θl, to be dependent on Y (Y is standardized to have mean zero and a standard deviation of 1). The surrogate allele frequencies θl have a deviation from the ancestral allele frequency ɛl that is linearly proportional to the environmental variable Y with coefficient β; i.e.,

|

(5) |

We note that while this model predicts a linear relationship between θl and Y, this does not necessarily imply a linear relationship between the population allele frequencies xl and Y due to the boundaries for the population allele frequency at 0 and 1. Note that β and Y could also be multivariate, allowing combinations of climate variables to be investigated. However, the allele frequencies at any one locus are intrinsic noisy; thus there is limited information about even a single climate variable correlation and so we refrain from implementing this multivariate option.

We place a prior on β, P(β), and then estimate the posterior

|

(6) |

where P(β) is defined to be a uniform distribution between our choice of the minimum and maximum values of β, βmin and βmax. We use the posterior of the covariance matrix estimated from the control SNPs as the prior for the covariance matrix for a single locus. Since we perform the test at each locus separately, we further assume that the information from the control loci provides all of the information about the covariance matrix. Thus, rather than exploring the posterior of the covariance matrix given both the control SNPs and the test SNP, we can simply use draws from the posterior of the matrix that have previously been generated from the control SNPs. In practice, in our applications to human SNP data, we found that we have sufficient information (i.e., enough control loci) that the posterior mass of the covariance matrix is tightly concentrated on a single matrix and so it makes little difference if we use a single draw of covariance matrix from the posterior given the control loci and ignore the small uncertainty in this matrix. Thus, for the applications in this article, we simply use a single draw from the posterior of the matrix, while noting that for applications with smaller numbers of markers, it may be important to incorporate the uncertainty in the matrix.

To summarize the support for the alternative model M1 (i.e., the model with β) compared to the null model M0 we calculate the Bayes factor

|

(7) |

where P(M0 | nl, ml) is the posterior probability of the data at locus l under the null model (β = 0), found by integrating the right-hand side of Equation 3 over all the parameters of the null model, and P(M1 | nl, ml) is given by the integral of Equation 6 over all parameters of the alternative model. The calculation of the Bayes factor is discussed in appendix b, where we present a way in which many environmental correlations can be tested using a single run of the MCMC for a SNP. The importance sampler will perform best when the target distribution is close to that simulated under, i.e., when the posterior of the data under the alternative model is close to that under the null model. This suggests that the importance sampler will converge quickly when the data resemble data generated under the null model; i.e., our estimates of large Bayes factors will be noisier. As with all MCMC algorithms the estimates of Bayes factors produced by the method should be checked with multiple runs of the algorithm. We find good agreement between Bayes factors over independent runs and also between the posterior of β estimated by the importance sampler and posteriors for β estimated by MCMC (results not shown).

Assessing significance:

Various aspects of population history are likely to violate the simple assumptions of our model; therefore the addition of the linear dependence on an environmental variable might improve the fit to the frequencies of even neutral alleles. Indeed, when investigating the performance of the method, on control sets of SNPs chosen to be neutral (e.g., Conrad et al. 2006; Hancock et al. 2008), we found that the distribution of Bayes factors differed dramatically between environmental variables. This variation in the distribution of Bayes factors, across environmental variables, was not seen in data sets simulated using the matrix estimated from the Human Genome Diversity Project (HGDP) data, suggesting that it represents a feature of the data (results not shown). Thus, a large Bayes factor supporting the alternative model may not be strong evidence that the SNP has been the target of selection. A robust way to overcome this problem is to apply the method to all of the control SNPs and build an “empirical distribution” of Bayes factors from the control SNPs. The Bayes factor for the SNP of interest (for a given environmental variable) can then be compared to this distribution to judge its significance (Hancock et al. 2008, 2010). For applications of the method we recommend that these empirical distributions are constructed separately for bins of mean global allele frequency and ascertainment scheme; this will control for features of the data not well captured by the model. We direct interested readers to Hancock et al. (2010), where these recommendations have been implemented in a genome-wide scan for adaptive alleles.

RESULTS

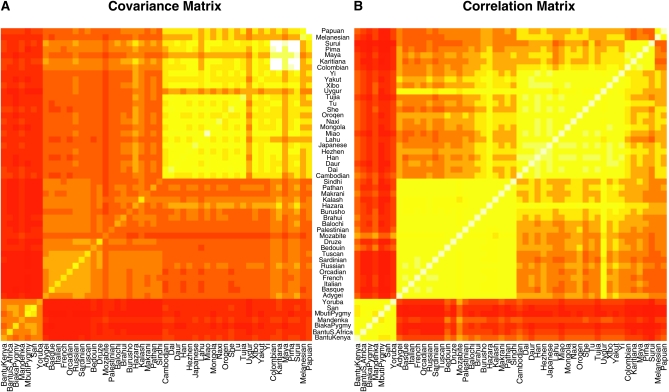

To explore our method, we initially applied our method to the genotype data gathered by Conrad et al. (2006) for 927 individuals from the 52 human populations of the HGDP panel. These populations represent a reasonable sampling from around the world, although there are some notable gaps in the sampling. Conrad et al. (2006) typed 2333 SNPs in 32 autosomal regions to study patterns of linkage disequilibrium. Although the SNPs within each region are in partial linkage disequilibrium, and thus violate our assumption of independence between SNPs, parameter estimates of the model should not be biased as a result (although this violation may lead to overconfident parameter estimates). Consistent with this, we get very similar results if we run the analysis on subsets of the genomic regions (results not shown). We first estimated the 52 × 52 variance–covariance matrix of the HGDP populations. We show a single draw from the posterior of the covariance matrix in Figure 2A and the correlation matrix computed from this matrix in Figure 2B. These matrices reveal the close genetic relationship of populations from the same geographic region, which is qualitatively similar to the groups identified by STRUCTURE for these data (Conrad et al. 2006) and samples (Rosenberg et al. 2002; Li et al. 2008). Also, the Uygur and Hazara populations are clearly picked out as showing higher covariance between the East Asian and Western Eurasia blocks than other populations within the blocks, consistent with the hypothesis that these populations result from recent admixture events between these broad geographic regions (Rosenberg et al. 2002).

Figure 2.—

(A) A single draw from the posterior of the covariance matrix estimated for the HGDP SNPs of Conrad et al. (2006). (B) The correlation matrix calculated from the covariance matrix shown in A. The matrices are displayed as heat maps with lighter colors corresponding to higher values. The rows and columns of these matrices have been arranged by broad geographic label.

The convergence of the MCMC to the posterior is relatively quick and dropping the first 5000 iterations was more than sufficient as a burn-in. Multiple independent runs with different starting positions quickly converged to similar matrices. Draws from the posterior showed relatively small fluctuations around the matrix displayed in Figure 2A, suggesting that the matrix is reliably estimated from this data set.

The posterior of the matrix estimated from these data is reasonably unaffected by the choice of prior of the covariance matrix. If instead of setting the shape matrix of the prior on the covariance matrix (R) to the identity matrix, we set it to specify a strong prior correlation (i.e., Rij = 1 if i = j and 0.99 for i ≠ j), there is no notable difference in the posterior estimate of the covariance matrix. For example, the Mantel matrix correlations between draws of the posterior matrix within a run are very similar to those observed between runs with different priors (results not shown). For applications to small numbers of markers and/or sample sizes, it may be advisable to use this prior shape matrix that reflects a strong correlation of allele frequencies between populations. This will encourage the method to combine information over small samples and will reduce the chance that populations with small samples will add noise to the test.

Power simulation:

Next we explored the power of our method to detect correlations between allele frequencies and environmental variables in the HGDP data. Simulating selection in a large number of populations under nonequilibrium models of history is challenging and unappealing, as it requires the arbitrary choice of many parameters. Instead we took an empirical approach and altered the sample frequency of the SNPs in the Conrad et al. (2006) HGDP panel by adding a linear effect of the environment variable. If the current sample frequency of an allele in population k is Xk = nk/(nk + mk), then our new frequency is  = Xk+βYk, where Yk is the environmental variable in the kth population (we rescaled Y to have mean zero and variance 1). We converted these to sample frequencies by rounding nk

= Xk+βYk, where Yk is the environmental variable in the kth population (we rescaled Y to have mean zero and variance 1). We converted these to sample frequencies by rounding nk to the nearest integer

to the nearest integer  ; if

; if  is negative or exceeds the sample size (nk+mk), then

is negative or exceeds the sample size (nk+mk), then  is set to zero or nk + mk, respectively. Informally, this linear shift may be thought of as modeling strong selection that acted recently on the frequencies of the allele across populations. We conducted these power simulations for a range of β.

is set to zero or nk + mk, respectively. Informally, this linear shift may be thought of as modeling strong selection that acted recently on the frequencies of the allele across populations. We conducted these power simulations for a range of β.

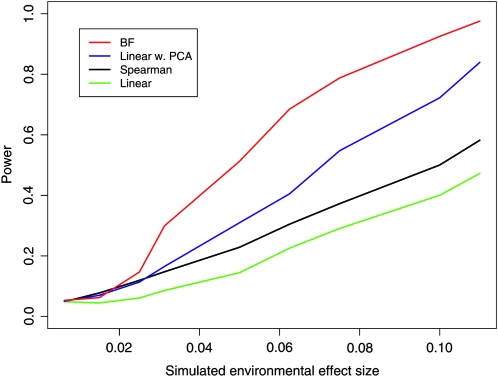

We then calculated the Bayes factor to assess support for a correlation between Y and the modified SNP frequencies. For comparison, we also calculated the power of a number of other test statistics aimed at detecting the correlation between the environmental variable and the sample allele frequencies: Spearman's rank correlation ρ, the P-value from a linear regression model, and the P-value in a linear model obtained after first regressing out the first three principal components of the genetic data. We note that none of these three alternative methods offers a well-calibrated statistic; i.e., the P-values were not uniform under the null model (i.e., β = 0). Therefore, for these alternative methods and our Bayes factors we used the empirical distribution of a test statistic to correctly set the cutoff threshold for significance. To do this, we calculate the test statistic for all SNPs, applying no linear effect of the environmental variable (i.e., β = 0), and create an empirical distribution for each of these test statistics. We then find the 5% cutoff for this empirical distribution and any test statistic lower than this is declared significant at the 5% level. To explore the power of the various methods to detect an environmental correlation, we chose a geographic variable, i.e., latitude, and a climate variable, i.e., summer precipitation. Latitude was chosen because it has been used in a number of previous studies (e.g., Beckman et al. 1994; Thompson et al. 2004; Young et al. 2005; Hancock et al. 2008) and summer precipitation was chosen as an example where all methods should have good power because summer precipitation is relatively uncorrelated with genetic patterns (it has only mildly significant correlations with the first four principal components of the genetic data). In Figure 3, we show our power to detect a latitudinal effect on population allele frequency. As can be seen, the methods that account for the genetic structure of the populations outperform those that do not, and our method is the most powerful.

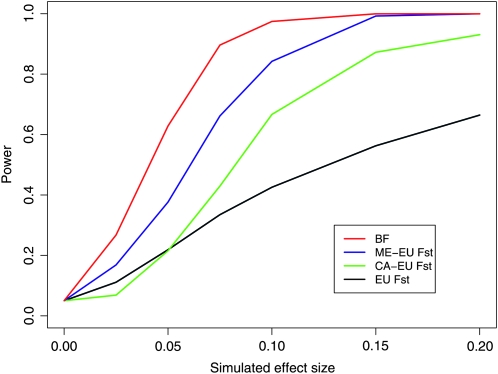

Figure 3.—

The power of various methods to detect a correlation between latitude and allele frequency.

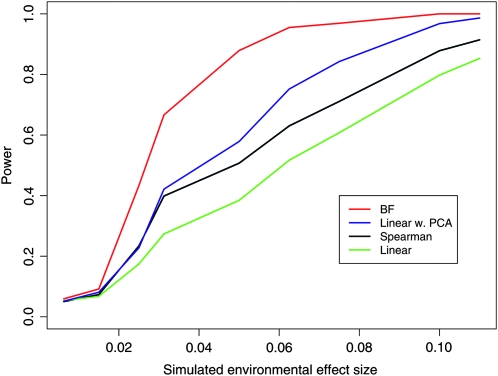

When the environmental variable is reasonably uncorrelated with the major axes of variation in genetic data, the power of all of the methods improves, compared to the latitudinal results, as the “noise” caused by genetic relatedness between populations is less confounded with the signal that we are trying to detect. This can be seen clearly by comparing the power to detect an effect with summer precipitation (see Figure 4) to the latitudinal case, where all methods have lower power (note that both environmental variables have been standardized and so the average change in frequency is approximately the same in both cases). Also, the improvement in power of methods that account for genetic structure over those that do not is greatly reduced if the environmental variable is not strongly correlated with the principal axes of variation in the genetic data. For example, the power of Spearman's rank test to detect an effect of summer precipitation is comparable to that of the principal component method.

Figure 4.—

The power of various methods to detect a correlation between summer precipitation and allele frequency.

We also explored our power to detect a “continental” effect. To this end, we created an environmental variable Y, where Y = 1 for all European populations and Y = −1 for all non-European populations. We again calculated our power to detect such an effect using our estimated Bayes factor as a test statistic. For comparison, we also calculated the power to detect the effect using various FST-based measures between broad geographic areas: pairwise FST between the Middle East and Europe, pairwise FST between Central Asia and Europe, and a European population-specific measure of FST (these were all calculated according to Cockerham and Weir 1986 and Weir and Hill 2002). We also calculated a global FST using “continent”-level labels, but it performed very poorly, presumably because the changes in allele frequency were restricted to a subset of populations, and so was not included. The results of the power simulations are shown in Figure 5. Our method has higher power than the standard FST-based methods, perhaps because it effectively combines information from all of the pairwise comparisons in the data while accounting for the noise and covariance in each comparison (see also Excoffier et al. 2009 for discussion).

Figure 5.—

The power of various methods to detect a “European effect” on allele frequency.

Data application:

To demonstrate the utility of the method for genome-wide data, we applied the method to the 640,698 autosomal SNPs typed by Li et al. (2008) in the HGDP–CEPH. An expanded exploration of these data for a range of environmental variables is given in Hancock et al. (2010). Since the genotyped SNPs come from three different ascertainment panels (Eberle et al. 2007), we estimated three different covariance matrices, by sampling three different sets of 10,000 SNPs at random from the three different SNP sets. Draws from the posterior of the three covariance matrices estimated were qualitatively very similar to the example shown in Figure 2 and to each other and showed little variation within runs of the MCMC (results not shown).

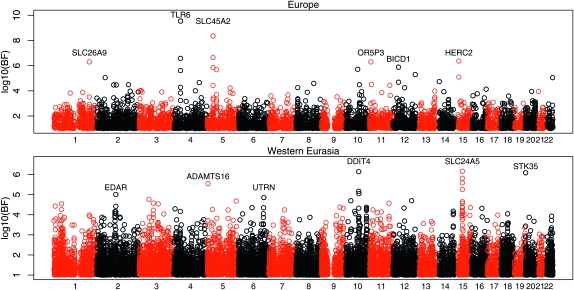

We calculated the Bayes factors for all autosomal SNPs for a number of different continental effects, using the covariance matrix for each SNP that matched its ascertainment set. All of the calculated Bayes factors, along with the matrices used, are available for download at http://www.eve.ucdavis.edu/gmcoop/. In Figure 6, we show the Bayes factors for all autosomal SNPs for two of the effects tested: a European effect and a Western Eurasian effect (Europe, Middle East, and Central Asia). For example, for the European effect we set Y = 1 for all European populations and Y = −1 for all other populations and then standardize Y.

Figure 6.—

A plot of the log10 Bayes factor for each SNP along the human genome for (A) a European effect and (B) a western Eurasian effect. Bayes factors <1 are not plotted. The numbers on the x-axis indicate chromosome number, with SNPs on different chromosomes colored alternately in red and black. We list the name of the gene that is nearest to each of the six highest-ranking SNPs in each plot (considering only the peak SNP in each cluster of high Bayes factors).

Among our top hits for a European effect are previously identified hits at TLR6 (Todd et al. 2007; Pickrell et al. 2009), SLC45A2 (Norton et al. 2007), and HERC2 (Sulem et al. 2007). Variants at these genes are known to be involved in immune response, skin pigmentation, and eye color, respectively. All of these alleles strongly differentiate the European populations from the closely related Middle Eastern and Central Asian populations. Instructively, SNPs in the Lactase gene are not among our top European effects, despite the selected allele being at high frequency within Europe and almost absent in the Middle East. This is likely due to the fact that the selected allele is also at high frequency in Central Asia (Bersaglieri et al. 2004) and in fact SNPs near the lactase gene have some of the largest Bayes factors for a joint Europe–Central Asian effect genome-wide.

Our top hit for a Western Eurasian effect (Figure 6) is the previously identified signal at SLC24A5 (Lamason et al. 2005). Interestingly, EDAR is among our top hits for a Western Eurasian effect; this gene was previously identified by Sabeti et al. (2007) as the putative target of the strong selective sweep in East Asians (and is among the top Bayes factor signals for an East Asian–America effect). The Bayes factor signal in Western Eurasia hints that this genomic region might have undergone separate sweeps in Western Eurasia and East Asia. To explore the signal for a second sweep using haplotype patterns in this region, we calculated the empirical P-value for the XPEHH statistic (Sabeti et al. 2007), which compared haplotype homozygosity between two populations, for a window containing this gene (see Pickrell et al. 2009 for details). The empirical P-value was 0.029 in Europe, 0.046 in the Middle East, and 0.026 in Central Asia, suggesting evidence of a second sweep, although less strongly than the XP-EHH signal in East Asians for this region (empirical P-value of 0.0015).

DISCUSSION

In this article, we develop a flexible model for examining the correlation in allele frequencies across populations, parameterized by the covariance matrix. Our main goal was to use this estimated covariance matrix to perform a parametric test of the effect of an environmental or continental variable on the frequency of an allele at a SNP, while controlling for the correlation of allele frequencies across populations. Therefore, this model has strong similarities to generalized linear mixed models, where the environmental variable is a fixed effect and the covariance matrix governs the random effects. Thus, the approach is conceptually similar to the approaches introduced to map phenotypes across individuals in strongly structured populations; in these approaches a kinship matrix is used to account for differences in the background genetic relatedness (Yu et al. 2006; Kang et al. 2008). The proposed test results in a considerable improvement in power to estimate effects over methods widely used in the literature. This gain of power comes from the fact that the estimated covariance matrix informs the model as to how to weight the different populations.

For a single locus, the covariance matrix is proportional to the variance and covariance of allele frequencies around a common mean, where the constant of proportionality is the binomial variance ɛl(1 – ɛl). This means that the elements of the estimated matrix have a direct intepretation as a parametric estimate of the pairwise and population-specific FST. This interpretation holds only for relatively low levels of drift, as the boundaries at zero and one distort the relationship between the variance of the multivariate normal and FST for large levels of drift. Nicholson et al. (2002) have an extensive discussion of this interpretation of the variance in the case where each population drifts independently from some shared ancestral population, and Weir and Hill (2002) and Samanta et al. (2009) discuss this connection for the maximum-likelihood estimator of the sample covariance matrix when levels of drift are low and sample sizes are large. The framework presented here thus provides a Bayesian model-based estimate of FST matrices discussed in Weir and Hill (2002). An alternative model-based formulation of population-specific FST is offered by the beta-binomial island-model framework (Balding and Nichols 1995; see also Balding 2003). This island-model framework considers populations at an equilibrium of mutation–migration–drift balance, as opposed to the nonequilibrium pure drift model of Nicholson et al. (2002); the merits of these two approaches are discussed in Nicholson et al. (2002), Balding et al. (2002), and Balding (2003). The island-model framework has been extended to identify loci that have outlying allele frequencies with respect to particular populations (Beaumont and Balding, 2004; Bazin et al. 2010). Our aim here has been to develop a test of environmental selective gradients; thus while we have implemented this in the spirit of the pure-drift model of Nicholson et al. (2002) our framework could be implemented into the island-model framework and would likely perform comparably [see also the discussion of choice of g() below].

The study of the pattern of the covariance of allele frequencies across populations has a long history as the covariance contains information about the history and levels of gene flow between populations (Cavalli-Sforza et al. 1964; see also the review by Felsenstein 1982). It may be fruitful to adapt the Bayesian framework presented here to infer the historical relationships between the sampled populations. For example, the drift on different branches of a tree of populations could be approximated by normal deviations, which would allow rapid calculation of the branch lengths (see RoyChoudhury et al. 2008 for a recent presentation of the problem). However, the pairwise covariance of allele frequencies across populations can be used only to learn about the average coalescent times within and between pairs of populations (Slatkin 1991) and so this approach could not be directly used to distinguish between isolation models and migration models (see McVean 2009, for discussion).

Here, we take a Bayesian approach that fully models the uncertainty in allele frequencies due to sampling. Thus, while we have discussed the model in terms of allele frequencies across population samples, it could be applied as an individual-based analysis where the genotype of each individual represents two draws from a unique “population.” This formulation may be useful when population labels are not known a priori. The current interest in principal component analysis (PCA), now almost exclusively based upon individual-level rather than population-level analyses, suggests that such applications would be useful, given that PCA is a decomposition of the covariance matrix (see McVean 2009, for discussion). Our method can also be extended to other marker types, e.g., for biallelic dominant markers, by using a different form from P(nl, ml | xl) (e.g., Falush et al. 2007). Likewise, the method could also be applied to data for pooled sample data or next-generation short-read sequencing data—once again by modifiying P(nl, ml | xl). We have also experimented with different transforms of the population frequencies [i.e., g()], e.g., a logit transform, and found that they gave very similar results, particularly in terms of the test of environmental variables (results not shown). Such transforms may be useful for applying the method to multiallelic systems such as microsatellites (e.g., Wasser et al. 2004).

We summarize the support for the model with an effect on an environmental variable compared to a model without a linear effect using a Bayes factor. In the application to the HGDP data, we ranked the SNPs by Bayes factor. A posterior predictive P-value (Rubin 1984) could be obtained by simulation from the posterior distribution of the null model, which would likely lead to a similar ranking. However, we have deliberately refrained from utilizing the method to make statements about the absolute “significance” of the correlation seen at specific SNPs, as we are somewhat skeptical about the fit of the null model even to data with no environmental dependence. Rather we suggest that careful comparison of the empirical distribution of test statistics (in our case Bayes factors) between a set of putatively selectively neutral control markers and candidate SNPs of interest is the most convincing way forward (Hancock et al. 2008). This can be accomplished in a genome-wide setting by genic to nongenic SNPs (assuming that nongenic sites are less likely to be functional) to judge the evidence for an enrichment of selection signals in the tails of a test statistic (Barreiro et al. 2008; Coop et al. 2009; Hancock et al. 2010). The empirical approach in turn has some serious drawbacks, the most obvious of which is deciding what statistical cutoff to use, as the choice of cutoff reflects one's prior beliefs of the prelevance of selection (Teshima et al. 2006).

It is hard to predict in advance how often strong correlations between allele frequencies and environmental variables will form across a species range. However, it is likely that strong gene flow and the parallel mutation will both act to reduce the likelihood of strong correlations. If selection is not strongly divergent across a species range, i.e., the locally adaptated alleles are not selected against in other regions, then the selected allele will be spread across the species range by migration. Under these circumstances correlations may temporarily form but they may not persist for long, and these occurrences will also depend critically upon where the mutation arose and patterns of migration. [Even standard allele frequency differentiation-based methods may not identify a rapidly spreading sweep, and haplotype-based methods may be more informative (e.g., Voight et al. 2005).] In addition, the method will tend to detect only those loci where the environmental variable had a consistent effect on the frequency of a particular allele (due to either hitchhiking or the direct action of selection) and so may not detect regions of the genome where in different populations the same selection pressure has caused different haplotypes to go to fixation. Thus, if rates of gene flow are low across a species range compared to mutation rates toward the adaptive phenotype, then repeated evolution of a phenotype may occur by different genetic routes in different parts of the species range. For example, the genetic basis of pigmentation differs between geographic regions within a number of species (e.g., Hoekstra and Nachman 2003; Norton et al. 2007; Edwards et al. 2010). Under these circumstances, the frequency of an allele will be correlated with an environmental variable only in parts of the species range. This suggests that it may be profitable to perform the analysis, including the estimation of the covariance matrix, separately in different geographic regions.

In closing, we note that while the method presented here is potentially very useful in identifying selected loci via their correlation with environmental variables, we caution against overintepreting the correlations (or lack of correlations) found. It is unlikely that causal selection pressures can be identified by such correlations as many environmental and ecological variables covary. Further, as outlined above, correlations may exist as a transient stage during the spread of a selected allele (even in the absence of a causal relationship). Thus we view this method as a powerful way of highlighting interesting loci and correlations that can be further explored by follow-up studies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Molly Przeworski, John Novembre, and members of the Di Rienzo, Pritchard, Przeworski, Stephens groups and the University of California at Davis Evolutionary Discussion Group for helpful discussions. We thank John Novembre, Molly Przeworski, Peter Ralph, and the reviewers for helpful comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by a Packard Foundation and Howard Hughes Medical Institute grant to J.K.P., by National Institutes of Health grants (DK56670 and GM79558) to A.D., and by a Sloan Foundation Fellowship to G.C.

APPENDIX A: SAMPLING FROM THE POSTERIOR

We first describe how we calculate the posterior under the null model, and then we discuss the calculation of the Bayes factor in the next section. We wish to estimate the posterior of Ω integrating over our uncertainty in θ and ɛ. To do this, we use MCMC, where in each iteration of the MCMC algorithm we sequentially update the different parameters. Conditional on Ω and θl, we update ɛl at each locus using a standard Metropolis update, i.e., add a small normally distributed deviation to ɛl and accept the new ɛl if it falls within the range (0, 1), with a probability given by the ratio of the posteriors under the current and new value of ɛ.

We could use a similar proposal to update each θkl but since the θl are highly correlated over populations, we found that updating them individually results in a high rejection rate. Thus, we update the entire vector of transformed population frequencies (θl) simultaneously for a locus in a way that attempts to account for that correlation. Our proposal for the new transformed frequencies at a locus l,  , is a small deviation from our current vector of θl. This random deviation is chosen to have the correct covariance structure over populations

, is a small deviation from our current vector of θl. This random deviation is chosen to have the correct covariance structure over populations  = θl + Δ, where Δ = CX, X is a length K vector of standard uncorrelated normals, and C is the Cholesky decomposition of the current covariance matrix (i.e., Ω = CCT). We then accept

= θl + Δ, where Δ = CX, X is a length K vector of standard uncorrelated normals, and C is the Cholesky decomposition of the current covariance matrix (i.e., Ω = CCT). We then accept  with probability given by the ratio of the posteriors.

with probability given by the ratio of the posteriors.

As the inverse Wishart is the conjugate prior for the covariance–variance matrix of a multivariate normal, given all the θl and ɛl over all loci, the posterior is itself inverse Wishart with form

|

(A1) |

where  is the sample estimate of covariance matrix of θl over loci,

is the sample estimate of covariance matrix of θl over loci,  . Therefore, we can update our covariance matrix using Gibbs sampling, by sampling from the Wishart distribution given in Equation A1 using the algorithm described in Odell and Feiveson (1966).

. Therefore, we can update our covariance matrix using Gibbs sampling, by sampling from the Wishart distribution given in Equation A1 using the algorithm described in Odell and Feiveson (1966).

APPENDIX B: EVALUATING THE BAYES FACTOR

There are a number of ways to evaluate this Bayes factor; for example, we could allow the MCMC to move between the models with and without the linear factor β and estimate the Bayes factor by the proportion of time the MCMC spends in the alternative model. However, because we wish to apply the test to large sets of SNPs, e.g., genome-wide data sets for a large number of environment variables, we make use of importance sampling to quickly calculate the Bayes factor from a single run of the MCMC under the null distribution. Specifically the ratio of probabilities  can be written as

can be written as

|

(B1) |

|

(B2) |

Writing

|

(B3) |

we see that

|

(B4) |

and thus that the Bayes factor is the expected value of W(θl, β, ɛl, Ω) integrated over the null model posterior and so can be evaluated by averaging W(θl, β, ɛl, Ω) over the MCMC on θl, ɛl, Ω (see, for example, Liu 2002). We do this by averaging W(θl, β, ɛl, Ω) simultaneously for a grid of β-values and obtain an estimate of the Bayes factor by numerically integrating these grid points over the uniform prior. The fact that the Bayes factor for a particular environmental variable can be evaluated using the MCMC for the null model means that we can evaluate the Bayes factor quickly for as many environmental variables as required, using a single run of the MCMC for each SNP.

References

- Allen, J., 1877. The influence of physical conditions in the genesis of species. Radic. Rev. 1 108–140. [Google Scholar]

- Auton, A., K. Bryc, A. R. Boyko, K. E. Lohmueller, J. Novembre et al., 2009. Global distribution of genomic diversity underscores rich complex history of continental human populations. Genome Res. 19 795–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balding, D., 2003. Likelihood-based inference for genetic correlation coefficients. Theor. Popul. Biol. 63 221–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balding, D. J., and R. A. Nichols, 1995. A method for quantifying differentiation between populations at multi-allelic loci and its implications for investigating identity and paternity. Genetica 96 3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balding, D. J., A. D. Carothers, J. L. Marchini, L. R. Cardon, A. Vetta et al., 2002. Discussion on the meeting on ‘Statistical modelling and analysis of genetic data’. J. R. Stat. Soc. B 64 737–775. [Google Scholar]

- Barreiro, L., G. Laval, H. Quach, E. Patin and L. Quintana-Murci, 2008. Natural selection has driven population differentiation in modern humans. Nat. Genet. 40 340–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazin, E., K. J. Dawson and M. A. Beaumont, 2010. Likelihood-free inference of population structure and local adaptation in a Bayesian hierarchical model. Genetics 185 587–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaumont, M. A., and D. J. Balding, 2004. Identifying adaptive genetic divergence among populations from genome scans. Mol. Ecol. 13 969–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckman, G., R. Birgander, A. Sjlander, N. Saha, P. A. Holmberg et al., 1994. Is p53 polymorphism maintained by natural selection? Hum. Hered. 44 266–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann, C., 1847. Über die verhältnisse der wärmeökonomie der thiere zu ihrer grösse. Göttinger Studien 3 595–708. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, A., and M. Kreitman, 1993. Molecular analysis of an allozyme cline: alcohol dehydrogenase in Drosophila melanogaster on the east coast of North America. Genetics 134 869–893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bersaglieri, T., P. Sabeti, N. Patterson, T. Vanderploeg, S. Schaffner et al., 2004. Genetic signatures of strong recent positive selection at the lactase gene. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 74 1111–1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalli-Sforza, L., 1966. Population structure and human evolution. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 164 362–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalli-Sforza, L. L., I. Barrai and A. W. Edwards, 1964. Analysis of human evolution under random genetic drift. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 29 9–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockerham, C., and B. Weir, 1986. Estimation of inbreeding parameters in stratified populations. Annu. Hum. Genet. 50 271–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad, D., M. Jakobsson, G. Coop, X. Wen, J. Wall et al., 2006. A worldwide survey of haplotype variation and linkage disequilibrium in the human genome. Nat. Genet. 38 1251–1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coop, G., J. K. Pickrell, J. Novembre, S. Kudaravalli, J. Z. Li et al., 2009. The role of geography in human adaptation. PLoS Genet. 5 e1000500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Coyne, J. A., and E. Beecham, 1987. Heritability of two morphological characters within and among natural populations of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 117 727–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobzhansky, T., 1948. Genetics of natural populations XVI. Altitudinal and seasonal changes produced by natural selection in certain populations of Drosophila pseudoobscura and Drosophila persimilis. Genetics 33 158–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberle, M., P. Ng, K. Kuhn, L. Zhou, D. Peiffer et al., 2007. Power to detect risk alleles using genome-wide tag SNP panels. PLoS Genet. 3 1827–1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, M., A. Bigham, J. Tan, S. Li, A. Gozdzik et al., 2010. Association of the oca2 polymorphism His615Arg with melanin content in East Asian populations: further evidence of convergent evolution of skin pigmentation. PLoS Genet. 6 e1000867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Excoffier, L., T. Hofer and M. Foll, 2009. Detecting loci under selection in a hierarchically structured population. Heredity 103 285–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falush, D., M. Stephens and J. K. Pritchard, 2007. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data: dominant markers and null alleles. Mol. Ecol. Notes 7 574–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein, J., 1982. How can we infer geography and history from gene frequencies? J. Theor. Biol. 96 9–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein, J., 1985. Phylogenies and the comparative method. Am. Nat. 125 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Foll, M., and O. Gaggiotti, 2008. A genome-scan method to identify selected loci appropriate for both dominant and codominant markers: a Bayesian perspective. Genetics 180 977–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloger, C. L., 1833. Das Abändern der Vögel Durch Einfluss des Klimas. A. Schultz & Co., Breslau, Germany.

- Haldane, J. B., 1948. The theory of a cline. J. Genet. 48 277–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock, A., D. Witonsky, A. Gordon, G. Eshel, J. Pritchard et al., 2008. Adaptations to climate in candidate genes for common metabolic disorders. PLoS Genet. 4 e32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock, A., D. B. Witonsky, E. Ehler, G. Alkorta-Aranburu, C. Beall, et al., 2010. Adaptations to diet, subsistence and ecoregion in the human genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107(Suppl. 2): 8924–8930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hoekstra, H., K. Drumm and M. Nachman, 2004. Ecological genetics of adaptive color polymorphism in pocket mice: geographic variation in selected and neutral genes. Evolution 58 1329–1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoekstra, H. E., and M. W. Nachman, 2003. Different genes underlie adaptive melanism in different populations of rock pocket mice. Mol. Ecol. 12 1185–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huey, R. B., G. W. Gilchrist, M. L. Carlson, D. Berrigan and L. Serra, 2000. Rapid evolution of a geographic cline in size in an introduced fly. Science 287 308–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxley, J., 1939. Clines: an auxilliary method in taxonomy. Bijdr. Diek. 27 491–520. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, S., and A. Bradshaw, 1966. Evolutionary divergence among adjacent plant populations. I. The evidence and its theoretical analysis. Heredity 21 407–441.

- Jakobsson, M., S. Scholz, P. Scheet, J. Gibbs, J. VanLiere et al., 2008. Genotype, haplotype and copy-number variation in worldwide human populations. Nature 451 998–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang, H. M., N. A. Zaitlen, C. M. Wade, A. Kirby, D. Heckerman et al., 2008. Efficient control of population structure in model organism association mapping. Genetics 178 1709–1723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamason, R., M. Mohideen, J. Mest, A. Wong, H. Norton et al., 2005. SLC24A5, a putative cation exchanger, affects pigmentation in zebrafish and humans. Science 310 1782–1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenormand, T., 2002. Gene flow and the limits to natural selection. Trends Ecol. Evol. 17 183–189. [Google Scholar]

- Lewontin, R., and J. Krakauer, 1973. Distribution of gene frequency as a test of the theory of the selective neutrality of polymorphisms. Genetics 74 175–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, J., D. Absher, H. Tang, A. Southwick, A. Casto et al., 2008. Worldwide human relationships inferred from genome-wide patterns of variation. Science 319 1100–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lifton, R. I., D. Wamock, R. Acton, L. Harman and J-M. Lalouel, 1993. High prevalence of hypertension-associated angiotensinogen variant T235 in African Americans (Abstr.). Clin. Res. 41 260A. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J., 2002. Monte Carlo Strategies in Scientific Computing. Springer-Verlag, Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany/New York.

- Mayr, E., 1942. Systematics and the Origin of Species, From the Viewpoint of a Zoologist, pp. 88–98. Columbia University Press, New York.

- McCracken, K. G., M. Bulgarella, K. P. Johnson, M. K. Kuhner, J. Trucco et al., 2009. Gene flow in the face of countervailing selection: adaptation to high-altitude hypoxia in the betaA hemoglobin subunit of yellow-billed pintails in the Andes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 26 815–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McVean, G., 2009. A genealogical interpretation of principal components analysis. PLoS Genet. 5 e1000686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen, L. M., and H. E. Hoekstra, 2008. Natural selection along an environmental gradient: a classic cline in mouse pigmentation. Evolution 62 1555–1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagylaki, T., 1975. Conditions for existence of clines. Genetics 80 595–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson, G., A. Smith, F. Jónsson, O. Gústafsson, K. Stefánsson et al., 2002. Assessing population differentiation and isolation from single-nucleotide polymorphism data. J. R. Stat. Soc. B 64 695–715. [Google Scholar]

- Nordborg, M., T. T. Hu, Y. Ishino, J. Jhaveri, C. Toomajian et al., 2005. The pattern of polymorphism in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Biol. 3 e196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton, H., R. Kittles, E. Parra, P. McKeigue, X. Mao et al., 2007. Genetic evidence for the convergent evolution of light skin in Europeans and East Asians. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24 710–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novembre, J., and A. Di Rienzo, 2009. Spatial patterns of variation due to natural selection in humans. Nat. Rev. Genet. 10 745–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odell, P., and A. Feiveson, 1966. A numerical procedure to generate a sample covariance matrix. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 61 199–203. [Google Scholar]

- Pickrell, J. K., G. Coop, J. Novembre, S. Kudaravalli, J. Z. Li et al., 2009. Signals of recent positive selection in a worldwide sample of human populations. Genome Res. 19 826–837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pool, J. E., and C. F. Aquadro, 2007. The genetic basis of adaptive pigmentation variation in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol. Ecol. 16 2844–2851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relethford, J. H., 1997. Hemispheric difference in human skin color. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 104 449–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, A., 1975. Gene frequency distributions as a test of selective neutrality. Genetics 81 775–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, N., J. Pritchard, J. Weber, H. Cann, K. Kidd et al., 2002. Genetic structure of human populations. Science 298 2381–2385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RoyChoudhury, A., J. Felsenstein, and E. Thompson, 2008. A two-stage pruning algorithm for likelihood computation for a population tree. Genetics 180 1095–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, D. B., 1984. Bayesianly justifiable and relevant frequency calculations for the applied statistician. Ann. Stat. 12 1151–1172. [Google Scholar]

- Sabeti, P., P. Varilly, B. Fry, J. Lohmueller, E. Hostetter et al., 2007. Genome-wide detection and characterization of positive selection in human populations. Nature 449 913–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samanta, S., Y. J. Li and B. S. Weir, 2009. Drawing inferences about the coancestry coefficient. Theor. Popul. Biol. 75 312–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, P. S., C. T. Zhu, J. Das, M. Batavia, L. Yang et al., 2008. An amino acid polymorphism in the couch potato gene forms the basis for climatic adaptation in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105 16207–16211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slatkin, M., 1973. Gene flow and selection in a cline. Genetics 75 733–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slatkin, M., 1991. Inbreeding coefficients and coalescence times. Genet. Res. 58 167–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storz, J. F., S. J. Sabatino, F. G. Hoffmann, E. J. Gering, H. Moriyama et al., 2007. The molecular basis of high-altitude adaptation in deer mice. PLoS Genet. 3 e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulem, P., D. Gudbjartsson, S. Stacey, A. Helgason, T. Rafnar et al., 2007. Genetic determinants of hair, eye and skin pigmentation in Europeans. Nat. Genet. 39 1443–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumner, F., 1929. The analysis of a concrete case of intergradation between two subspecies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 15 110–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Teshima, K., G. Coop and M. Przeworski, 2006. How reliable are empirical genomic scans for selective sweeps? Genome Res. 16 702–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, E. E., H. Kuttab-Boulos, D. Witonsky, L. Yang, B. A. Roe et al., 2004. CYP3A variation and the evolution of salt-sensitivity variants. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 75 1059–1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd, J., N. Walker, J. Cooper, D. Smyth, K. Downes et al., 2007. Robust associations of four new chromosome regions from genome-wide analyses of type 1 diabetes. Nat. Genet. 39 857–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umina, P. A., A. R. Weeks, M. R. Kearney, S. W. McKechnie and A. A. Hoffmann, 2005. A rapid shift in a classic clinal pattern in Drosophila reflecting climate change. Science 308 691–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voight, B., A. Adams, L. Frisse, Y. Qian, R. Hudson et al., 2005. Interrogating multiple aspects of variation in a full resequencing data set to infer human population size changes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102 18508–18513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasser, S. K., A. M. Shedlock, K. Comstock, E. A. Ostrander, B. Mutayoba et al., 2004. Assigning African elephant DNA to geographic region of origin: applications to the ivory trade. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101 14847–14852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir, B. S., and W. G. Hill, 2002. Estimating F-statistics. Annu. Rev. Genet. 36 721–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young, J. H., Y. P. Chang, J. D. Kim, J. P. Chretien, M. J. Klag et al., 2005. Differential susceptibility to hypertension is due to selection during the out-of-Africa expansion. PLoS Genet. 1 e82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J., G. Pressoir, W. H. Briggs, I. Vroh Bi, M. Yamasaki et al., 2006. A unified mixed-model method for association mapping that accounts for multiple levels of relatedness. Nat. Genet. 38 203–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]