Abstract

Best practices for adolescent sex education recommend science-based approaches. However, little is known about the capacity and needs of organizations who implement sex education programs on the local level. The purpose of this research was to describe successes and challenges of community organizations in implementing science-based sex education. Using qualitative methods, we interviewed program directors and educators in 17 state-funded adolescent pregnancy prevention/sex education programs as part of a larger mixed methods evaluation. Semi-structured interviews focused on success and challenges faced in implementing science-based approaches to program design, implementation and evaluation. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed and analyzed using a thematic approach. Grantees included a range of programs, from short programs on puberty and HIV for late elementary students, to skills-based curricular sex education programs for high schools, to year-long youth development programs. Key aspects of curricular choice included meeting the needs of the population, and working within time constraints of schools and other community partners. Populations presenting specific challenges included rural youth, youth in juvenile justice facilities, and working with Indiana's growing Latino population. Programs self-developing curricula described challenges related to assessment and evaluation of impact. Programs using commercial curricula described challenges related to curricular selection and adaptation, in particularly shortening curricula, and adapting to different cultural or social groups. A remarkable degree of innovation was observed. The use of qualitative methods permitted the identification of key challenges and successes in a state-sponsored small grants program. Information can be used to enhance program capacity and quality.

Keywords: Sexual abstinence, Sex education, Adolescent, Health policy, Qualitative research, Evaluation

Introduction

This qualitative study is part of a larger mixed methods evaluation of a state small grants program for pregnancy prevention [1]. The last decade has brought increasing consensus in the field of sex education on the importance of medical accuracy and science-based practices [2, 3], what constitutes an effective program [4, 5], and what parents and adolescents want from sex education [6]. Science-based practices include identifying public health objectives, specifying goals for behavior changes, logic models, selecting or developing curricula using behavioral/social science research, and integrating evaluation into program development, adaptation, implementation and assessment [5].

On the community level, there is increasing interest in adopting effective, science-based approaches. This interest, however, is often not supported by capacity, resources or funding. While sex education curricula are developed and evaluated under ideal conditions, their implementation occurs in real-world settings, in which conditions such as location, program exposure and student characteristics, vary. Anecdotal reports suggest that many community organizations adapt curricula to make them more suitable for a particular population, time frame, or organization's mission. These adaptations present a challenge, because for science-based programs to maintain their effectiveness, adaptations need to be made without compromising the core content, pedagogy, or implementation [7]. However, community organizations frequently do not have the capacity, organizational support, and resources to evaluate these adaptations. The objective of this study was to describe the successes and challenges faced by community organizations in selection, implementation, adaptation and evaluation of adolescent sex education programs. Because little is known about the topic, a qualitative method was chosen.

Methods

Larger Evaluation

As part of a larger, mixed methods evaluation of a state adolescent pregnancy prevention initiative, we conducted a series of in-depth interviews with directors of adolescent sex education, pregnancy prevention, and HIV prevention programs. Indiana State Department of Health's (ISDH) Indiana RESPECT (Indiana Reduces Early Sex and Pregnancy by Educating Children and Teens) provides small grants ($30,000/year) to community agencies to provide sex education programs stressing sexual abstinence and the delay of pregnancy and parenting for adolescents [1]. The evaluation took place during the 2007–2009 funding cycle, and included only programs funded by the State of Indiana. The two other components of the evaluation (not reported here) included a curricular review and student questionnaires.

Interviews

Face-to-face and telephone interviews were conducted by three trained interviewers (MO, MR, and HS) between October 2007 and April 2008 as part of an Indiana University Purdue University at Indianapolis-Clarian Institutional Review Board approved research project. All 17 program directors were interviewed; half of the interviews additionally included the agency executive director and/or health educators. Interviews lasted approximately 1 h, and focused on the use of science-based practices in program development, implementation, and evaluation. A semi-structured interview guide included seven primary questions, including, “Tell me about the population and community you serve,” “Tell me about this program,” and “What is working? Not working?” (see Appendix A). A series of follow-up questions were provided if certain types of information were not provided by the respondent. Interviewers kept field notes on the tone and context of the interview, and a single, in-class observation was done for a subset of programs using a structured observation tool. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. Interviews, observations and field notes were up-loaded into Atlas-ti, for qualitative analysis.

Analysis

We used a thematic analysis to identify and analyze patterns (themes) across interviews, observations and field notes [8]. Our analysis was informed by a critical realist perspective, in which reality has three levels: an empirical level consisting of experienced events, an actual level of all events, whether experienced or not, and a causal level composed of situations, conditions, and mechanisms leading to these events [9]. This theoretical perspective allowed for examination of the perspectives of the program directors within the actual contexts in which their programs operate (e.g. limited funding, school corporation policies), and for an analysis of the mechanisms leading to the program directors' experiences.

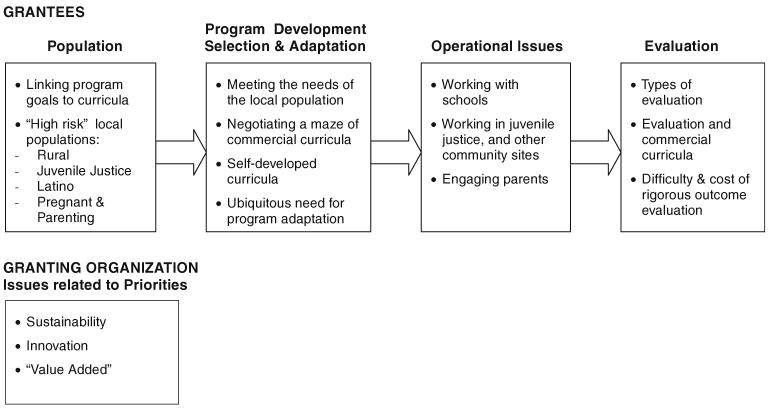

Initial, or first order, codes were developed based upon the literature and then refined based upon field notes and reviews of early transcripts. Examples of initial codes included rural youth, working with schools, program goals, perceived effectiveness, program adaptation, and program evaluation. Each initial code was selected and read by three authors (MO, JR, and MR), who identified higher order themes, characteristics and examples of each theme, and inter-relationships between themes. Higher order themes are listed in Fig. 1. Examples of higher order themes include: (1) meeting the needs of local populations (“high risk” youth, rural youth, Latino immigrants, youth in juvenile justice, pregnancy and parenting youth); (2) negotiating the maze of commercial curricula; (3) ubiquitous nature of program adaption; (4) challenges in working with schools; and (5) granting organization benefits of “value added” and supporting innovation. We use the term “value added” to describe programs who have taken the limited amount of RESPECT funding, and then used it to innovate and/or to leverage outside funding.

Fig. 1.

Community organizations implementing sex education: issues presenting challenges and often leading to successes

Results

Programs and Participants (see Table 1)

Table 1.

Summary of program characteristics

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Geographic location | |

| Indianapolis MSA | 7 (41%) |

| Counties in Chicago or Louisville, KY MSA | 2 (12%) |

| Small city, town, or rural | 8 (47%) |

| Organization | |

| Community Hospital | 4 (24%) |

| Affiliate of a National Organization | 6 (35%) |

| Local Community-based Organization | 7 (41%) |

| Ages of participants | |

| Late elementary aged (9–11) | 1 (6%) |

| Middle school aged (12–14) | 3 (18%) |

| High school aged or older (14 & up) | 6 (35%) |

| Span multiple age ranges | 7 (41%) |

| Location where program delivereda | |

| School | 13 (76%) |

| Juvenile justice facility | 5 (29%) |

| Community location | 5 (29%) |

| Type of curriculum | |

| Commercial | 8 (47%) |

| Self Developed | 8 (47%) |

| Developed by national affiliate, not available commercially | 1 (6%) |

MSA metropolitan statistical area

May be greater than 100%, as some programs serve adolescents in multiple locations

The Indiana RESPECT program provided funds to 17 distinct organizations during the grant period studied. Geographically, these organizations spanned the state of Indiana (northeast, northwest, central, southeast and southwest). Just over half were located in the major metropolitan statistical areas around Indianapolis, Chicago, and Louisville, KY. The remainder were in small cities and towns. These programs often served their surrounding rural counties. Organizations acting as fiscal agents for the grants included community hospitals, local community-based organizations, and local affiliates of national organizations, such as Girls, Inc. Participants ages' ranged from late elementary school aged (9–11 years), to high school and post-high school ages. Programs were delivered in schools, after-school programs, juvenile justice facilities, and community locations. Approximately half utilized commercial curricula and half developed their own curricula.

Challenges and Successes for Grantees (see Fig. 1)

Higher order themes fell into four categories for grantees, and one category for the granting organization (see Fig. 1). For grantees, these fell across the spectrum of program planning and delivery, from defining program goals and populations, to curricular development, operational issues, and program evaluation. They are described below.

Linking Program Goals and Curricula

All programs described the broad public health goals of adolescent pregnancy and STI prevention, then sorted themselves into three groups—sexual health promotion, traditional sex education, and youth development programs. Sexual health promotion goals included fostering a sense of “self-respect”, healthy relationships, and communication about abstinence and sex. Those programs focusing on adolescent girls added, “respecting one's body” and attaining equal power and footing in relationships. Commercial curricula used by these programs emphasized relationship and communication skills.

Health education goals included puberty and HIV education, and focused on meeting Indiana state educational standards. These programs were generally shorter, with limited exposures (e.g. 1–3 sessions), and focused on achievable educational goals: “When they make decisions [about sex] we want them to have some knowledge to base those decisions off of.” Framing a program as meeting state standards in HIV and family life education was a common technique to foster collaboration with schools.

Youth development programs focused on broader achievements and skills, such as graduation from high school. These program directors expressed the belief that the provision of general communication and relationship skills, coupled with encouragement to focus on school, vocational and life goals, could be translated into healthier sexual behavior and improved public health outcomes.

We observed marked variation in how goals were translated into curricular elements and pedagogy. Some programs had clear, concise goals with concrete steps and actions identified to meet those goals. Others articulated a broad goal (e.g. decrease unplanned pregnancy), but did not explicitly link that goal to program elements. Programs using logic models made more explicit linkages.

Meeting the Needs of Local Populations

High Risk Populations Served

All RESPECT programs described attempts to target adolescents at highest risk for unintended pregnancy and STIs. “High risk” was defined by program directors as low income, juvenile justice, pregnant and parenting, and limited educational skills (e.g. poor graduation rates or alternative high schools). Those working with schools often used district and school-level data to target the program to a particular risk group, ethnicity, or rural/urban designation. Because only a small number of grantees collected behavioral or epidemiologic data directly from their participants, programs also used school-level data to approximate participants' risk factors and (if data were available) sexual behavior. Beyond the general designation of “high risk,” program directors identified four specific populations of interest: rural youth, juvenile justice, schools, and Latino youth.

Rural Youth

Indiana is a primarily rural state. Program directors described two key challenges in working with rural youth. First, curricula targeting rural youth were not available. One program director described taking an evaluated commercial curriculum originally designed for African American urban youth, and substituting examples and cultural information more appropriate to rural Indiana. Second, program directors described the rural communities they worked in as more socially conservative and less willing to accept comprehensive approaches to sex education. One program was not permitted in general health classes, but instead was given referrals from guidance counselors of students perceived to be “high risk.” Another program described a prolonged community dialogue after a public concern about a student questionnaire asking about sexual behaviors that was to be used for program planning purposes. A common reaction was self-censorship, in which programs did not attempt to use comprehensive curricula or behavioral questionnaires.

Juvenile Justice

Two programs specifically targeted juvenile justice populations, with an additional three programs providing some programming to adolescents in juvenile justice facilities. One of the programs targeting this population collected sexual behavior data as part of an ongoing grant-supported outside evaluation of their program. This program found that adolescents reported very high risk sexual behaviors (e.g. anal sex, high numbers of partners), high rates of STIs, and simultaneously little family support for healthy decision-making.

These program directors also described a lack of curricula geared toward juvenile justice audiences. In response, the two programs working primarily with this population have developed their own curricula. A second challenge was mobility, and the variable and often short length of stay at juvenile justice facilities: “Kids come and go out of the system so it's hard to get the entire program to them.”

Latino Adolescents

Indiana has a growing Latino immigrant population, and several programs spoke of the need for new approaches to engaging Latino youth in their programs, and challenges to finding or adapting sex education programs to address Latino culture and family structure. A challenge described by program directors, who recognized that it was well described elsewhere but new to Indiana, was that adolescent participants frequently bridged two cultures as they negotiated romantic relationships, decisions about abstinence, sex and contraception, and unintended pregnancy. A program director working with pregnant and parenting adolescents described: “Translators [are needed] for Spanish-speaking parents. The girls will drop out of school to take care of the baby, or move out to [the] father of the baby's house so then he runs the show and is in control of her and the baby.” A program in a community with a large number of Latino farm workers adapted a commercial curricula to include culturally relevant examples, added bilingual educators to their program staff, and started an after-school youth development program called “Latino Student University” to provide mentors, role models, and allow students to talk in Spanish.

Program Development, Selection and Adaptation

Meeting the Needs of Local Population

Program development, program selection, and adaptation of commercial curricula was driven first and foremost by populations served. Examples of working with rural, juvenile justice involved and Latino youth are described above. One program that works primarily with young men across a variety of settings (community, high school) selected Wise Guys® to specifically address issues related to masculinity and peer pressure. When this organization then added additional high school classes and adolescent girls to their population, they adapted the gender information in the curricula to young women. Another grantee described changing activities and pedagogy (lecture to games) for out-of-school youth in a youth shelter.

Navigating the Maze of Commercial Curricula

Programs purchasing curricula described difficulties in assessing whether it was “science-based.” Finding and interpreting evaluation results was challenging, as these reports were often not readily available and frequently obscured evaluation conditions. Lists of recommended curricula were often difficult to interpret, frequently were inconsistent, and versions of programs on the lists were out of date. For example, the research showing positive effects of Postponing Sexual Involvement always paired it with a human sexuality curricula. And while the Wise Guy curriculum is considered “promising,” it was not “proven” (the program using Wise Guys is conducting an evaluation with an outside grant). Several program directors supplement their curricula with infant simulators (e.g. Baby Think It Over), but were unaware that, while infant simulators are well accepted by youth, they have not been shown to be effective in changing behavior. This inconsistent, difficult to access, and often conflicting information set up a situation in which program directors described difficulty in knowing which source to trust.

Adapting Curricula

Shortening Curricula

Shortening curricula was the most common type of adaptation, and happened in two different situations. As will be described below in the “schools” section, many stand-alone curricula were shortened based upon time or content limitations. A second group shortened curricula because sex education was only one component of broader youth development programs. These programs generally used the sex education materials to augment their broader intervention, rather than to stand alone, and choice of curricula ranged from self-developed to using components of commercial curricula. For example, one program opted to use CDC materials as a supplement. A second purchased an evaluated commercial curriculum and used only 6 of the 10 lessons.

Situational Influences on Adapting Curricula

Program directors described a variety of situational influences requiring the adaptation of curricula. For example, the presence of classroom teachers or guards (in juvenile justice facilities) triggered leaders to adapt specific activities so as not to compromise confidentiality.

Approaches to Adapting Curricula

Programs described three approaches to modifying content. First, all utilized the “expert opinion” of health educators within the organization. Second was the use of youth themselves to identify priorities or programs. For example, one program used youth focus groups to further improve its self-developed curriculum. Finally, programs relied on classroom experience with a particular curriculum to decide which elements to retain, cut or modify. An example is a program that identified lessons they felt were problematic with a particular population, modified that lesson, assessed the results, and made further modifications as was necessary.

Operational Issues

Working with Schools

Over three-fourths of programs work with schools. Most work with middle or high schools, but four provided at least some programming to upper elementary school students. These programs viewed themselves as guests in the school, and all described limitations in time, content, and evaluation placed upon them by the school.

Approximately half of programs described having 1 or 2 week blocks in a single class. Those using commercial curricula described looking specifically for curricula that could fit into the specified time block, such as the choice of Postponing Sexual Involvement (Emory University Jane Fonda Center) for a 1 week block in 8th grade health classes. The remainder described more limited time with students, necessitating either shortening a commercial curricula or designing one's own. The shortest program provided 45 min total instructional time to late elementary students. More common was an adaptation such as making a 5 day curricula fit into 3 or 4 days, or making 90 min sessions fit into 45–60 min.

Restrictions on content were a second challenge, summarized as, “School dictates curriculum.” Consistent with Indiana's emphasis on local control in education, program directors described a range of school policies on sex education that influenced the content of RESPECT-funded programs. A few described minimal restrictions, and used comprehensive curricula providing information on contraception and condoms, including condom demonstrations. Others described more marked content restriction: “The schools mandate abstinence only, and we are not allowed to talk about contraceptives.” In two instances, program directors described different policies for different schools within the same school district.

Communication and good relationships with teachers and school administrators were considered key to successful collaboration. Difficult relationships were roadblocks to entry or implementation. Good relationships were perceived to enhance access to students, increase time allowed in classrooms, and increase ability to negotiate program content.

Engaging Parents

A challenge described by all programs was engaging parents. Those that have parent sessions or hold parent information nights were routinely disappointed by poor participation rates. Other programs have abandoned formal programs for parents, instead addressing specific issues and concerns on an individual basis.

Program Evaluation

RESPECT Program directors gave a wide range of responses to questions about program evaluation, ranging from no evaluation to a formal evaluation with behavioral outcomes by an outside consultant. Almost all had some type of process evaluation, ranging from informal assessments of program activities by students and observing classroom teachers, to formal assessments of program implementation. For outcomes, many programs had some type of pre- and post-test measures of attitudes and knowledge. Four programs measured sexual behavior at least once, with two of these as part of formal outcome evaluations by outside consultants that included pre- and post-program assessments.

Programs with innovative structures and service delivery models used alternative approaches to assessment. A youth development program tracked graduation rates and compared those rates to relevant comparison populations of pregnant and parenting teens. A second program using a diffusion of innovation model, in which peer educators acted as a resource for their peers in home, school, and social settings, tracked outside contacts by peer educators and the content of those contacts.

The main barrier to program evaluation was cost. The two with outside evaluations had grant support. Other barriers included (1) too little time, (2) no expertise to analyze collected data, (3) students often only complete part of the program, and (4) schools were perceived to be unwilling to allow questionnaires on sexual behaviors.

Issues for the Granting Organization

Sustainability

No programs discussed sustainability plans beyond grant writing to support current staff and expand. Among programs operating in schools, almost all used their own staff to provide content, rather than training teachers at the school to co-teach or take over at some point in the future.

Value Added and Innovation

The amount of funds in individual grants was not sufficient to fund a program. Most programs patched together funds from a variety of sources for their programs, frequently using the RESPECT grant to leverage outside funds, “adding value” to the grant program.

Related to “value added,” RESPECT grants were often used to launch innovative approaches to sex education. Innovations were described in designing sex education to fit specific population needs (e.g. juvenile justice), implementing youth development principles (e.g. focusing on graduation in addition to prevention of a second birth), and using innovative methods to deliver sex education (e.g. using a diffusion of innovation approach in peer education.) Programs additionally adapted and innovated in content. A male-oriented curriculum directly addressed complex topics related to masculinity, such as homophobia and male sexuality; a middle school program adapted and then built upon an existing science-based curriculum to meet the needs of Indiana's growing Latino immigrant population.

Discussion

Our findings highlight the gap between best practices in sex education and what is possible on the community level. Despite a national consensus on the importance of science-based approaches [3, 10], and increasing availability of guidance on the development, selection and implementation of science-based curricula [5, 11, 12], program directors reported difficulties in implementing these approaches in their communities.

These findings likely reflect, in part, the complexities in the curricular marketplace. Because companies selling curricula have a financial stake in their use, commercially successful curricula often will not seek further evaluation, and when evaluations occur, they may be methodologically problematic, with inappropriate or missing comparison groups, or without behavioral end-points. This also reflects, in part, a shift in paradigm in sex education, from an older focus on content and educational standards, to a newer paradigm focused on skills, behavior change and public health outcomes [13].

Most evaluations use school- or community-based populations in urban settings. Community agencies serving other populations are faced with the choice of either drastic adaptations or creating their own program. We observed both approaches. Two groups of particular importance in our study were adolescents in juvenile justice facilities and adolescents in rural communities. Compared to community-based populations, incarcerated and adjudicated adolescents have higher rates of sexual risk behaviors and sexually transmitted infections [14, 15]. Additional contextual features include high levels of mobility, high poverty, substance use, school failure, lack of social supports, and high levels of mental health co-morbidity [14, 16].

Sex education in a rural setting has a different set of situational challenges compared to the urban settings of program evaluations. These include fewer available sexual health services, increased poverty, geographic isolation and transportation challenges, less tolerance of diversity, and communities opposed to sex education [17]. Organizations attempting to translate sex education programs developed for urban youth to rural settings have been met with mixed success [18–20]. Our findings demonstrate a need for resources directed to developing, adapting, and implementing programs specifically for rural youth.

Our interviews additionally highlight the importance of collaboration between schools and the public health community in adolescent sex education. While “local control” of schools over content and timing of sex education curricula allows programs to be more sensitive to community needs, “local control” can be a challenge to the broader public health community, which has invested time and effort into identifying common characteristics of effective programs to address unintended pregnancy and STIs [5].

The frequency of program adaptation was an important finding, and consistent with research in this area [20]. Nearly all programs using commercial curricula described some type of adaptation. Many times these were major changes, such as using the curricula for an entirely different social or cultural group, markedly reducing the time allotted, or eliminating major areas of content, such as information on condom use or contraceptives. Complicating matters at the community level is that the science of adaptation is a work in progress. At the time of the interviews, no guidelines were available on how to adapt, and program directors used their best judgment.

As important as what is being done, is what is not being done. Public health today emphasizes sustainability of interventions. Most of the grantees were community-based non-profit organizations contracting with schools or other organizations to provide specific programming. If the funding for the non-profit ends, the programming ends. This model may be necessary in some situations, such as juvenile justice, where most services are contracted out, and issues of confidentiality are paramount. In a school situation, however, sustainability could potentially be achieved a number of ways, such as training and utilizing health teachers to co-lead the program.

A final important finding was how limited state funds catalyzed local innovation, such as the development of curricula for youth in juvenile justice, or the use of a Diffusion of Innovation theory-based [21] peer education intervention. This innovation speaks to the ability of state funding sources to respond to community needs.

These findings point to the need for both funding and technical assistance in program development, selection, adaptation, and evaluation. Evaluation, in particular, whether of adaptations or of self-developed programs, requires sufficient dollars. One solution might be for state and local funders to identify a limited number of curricula they support (and can assist with adaptation). However, this approach carries the risk of suppressing creativity and innovation. An alternative might be to allow self-development of curricula, but to then hold these programs to standards of science-based practices in terms of evaluation and outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by NIH (K23-HD049444-01A2). These data were originally presented as a poster at the Pediatric Academic Societies and Asian Society for Pediatric Research Joint Meeting, Honolulu, May 2008. The authors thank the Indiana State Department of Health for their support of program evaluation. The information in this paper does not necessarily represent the views of the Indiana State Department of Health.

Appendix A

See Table 2

Table 2.

Interview guide

| Main question | Sample follow-up questions |

|---|---|

| Tell me about the population & community you serve |

|

| Tell me about this program |

|

| How did you select your curriculum? |

|

| How do you evaluate your program? |

|

| What parts are working? |

|

| What parts are not working? |

|

| Tell me about your experience of applying for a RESPECT grant |

|

Contributor Information

Mary A. Ott, Email: maott@iupui.edu, Section of Adolescent Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, Indiana University School of Medicine, 410 West 10th Street, HS1001, Indianapolis, IN 46202, USA.

Maura Rouse, Section of Adolescent Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, Indiana University School of Medicine, 410 West 10th Street, HS1001, Indianapolis, IN 46202, USA.

Jamie Resseguie, Section of Adolescent Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, Indiana University School of Medicine, 410 West 10th Street, HS1001, Indianapolis, IN 46202, USA.

Hannah Smith, Section of Adolescent Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, Indiana University School of Medicine, 410 West 10th Street, HS1001, Indianapolis, IN 46202, USA.

Stephanie Woodcox, Email: swoodcox@isdh.IN.gov, Indiana State Department of Health, 2 N. Meridian St., Section 8C, Indianapolis, IN 46204, USA.

References

- 1.Indiana State Department of Health. Indiana Respect. 2007 [cited May 8, 2009] Available from: http://www.indianarespect.com/whatIs.asp.

- 2.Santelli JS. Medical accuracy in sexuality education: Ideology and the scientific process. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98:1786–1792. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.119602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Definitions of science-based approach, science-based program, and promising program. Adolescent Reproductive Health: Promoting Science Based Approaches. 2007 [cited 2009 May 8]; Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/AdolescentReproHealth/DefineScienceApproach.htm.

- 4.Kirby D. Emerging answers 2007: Research findings on programs to reduce teen pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases. Washington, DC: National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirby D, Rolleri L, Wilson M. Tool to assess the characteristics of effective sex and Std/HIV education programs. Washington, DC: Healthy Teen Network; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Albert B. With one voice 2007: America's adults and teens sound off about teen pregnancy. Washington, DC: National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Healthy Teen Network. Science Based Approaches: Adaptation. 2008 [cited 2008 November 25]; Available from: http://www.healthyteennetwork.org/index.asp?Type=B_BASIC&SEC={E8F6E426-A1D8-4DBC-8CCF-1C68EB3BFEDB}&DE={1EE1BD19-5BEF-468D-918B-F36FA6134243}

- 8.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Houston S. Beyond social constructionism: Critical realism and social work. British Journal of Social Work. 2001;31:845–861. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Healthy Teen Network. Science-Based Programs. 2008 [cited 2008 August 22]; Available from: http://www.healthyteennetwork.org/index.asp?Type=B_BASIC&SEC={E8F6E426-A1D8-4DBC-8CCF-1C68EB3BFEDB}&DE={C0E02180-C80D-422B-B7C0-4FAE9B098193}

- 11.Science and success: Sex education and other programs that work to prevent teen pregnancy, HIV and sexually transmitted diseases. Advocates for Youth; Washington, DC: Advocates for Youth; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Putting what works to work. National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy; Washington, DC: National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy; What works: Curriculum-based programs that prevent teen pregnancy. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adolescent reproductive health: Promoting science-based approaches to prevent teen pregnancy, HIV, and Stds: Definitions of science-based approach, science-based program, and promising program. 2008 2008 October 5, 2007 [cited 2008 September 11]; Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/AdolescentReproHealth/DefineScienceApproach.htm.

- 14.Criminal Neglect: Substance Abuse, Juvenile Justice and the Children Left Behind. New York: The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Romero EG, Teplin LA, McClelland GM, et al. A longitudinal study of the prevalence, development, and persistence of HIV/sexually transmitted infection risk behaviors in delinquent youth: Implications for health care in the community. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e1126–1141. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vermeiren R, Jespers I, Moffitt T. Mental health problems in juvenile justice populations. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2006;15:333–351. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rural Center for AIDS/STD Prevention. Aids and sexually transmitted diseases in the rural south, Fact Sheet #14. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University, Purdue University and Texas A&M University; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stanton B, Harris C, Cottrell L, et al. Trial of an urban adolescent sexual risk-reduction intervention for rural youth: A promising but imperfect fit. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;38:55.e25–55.e36. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith MU, DiClemente RJ. Stand: A peer educator training curriculum for sexual risk reduction in the rural south. Preventive Medicine. 2000;30:441–449. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stanton B, Guo J, Cottrell L, et al. The complex business of adapting effective interventions to new populations: An urban to rural transfer. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;37:163. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. 4th. New York: Free Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]