Abstract

The juvenile justice setting provides a unique opportunity to administer the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine to a high-risk, medically underserved population. We examined current HPV vaccination practices in the United States. Most states (39) offer the HPV vaccine to females committed to juvenile justice facilities.

Keywords: Human papillomavirus (HPV), Human papillomavirus vaccine, Vaccine, Sexually transmitted infection, Genital warts, Cervical cancer, Adolescent, Youth, Juvenile justice, Consent

Healthcare needs of youth entering the juvenile justice system are substantial and complex. Acute healthcare needs are often treated first, and vaccination and other preventive healthcare services may be overlooked or underprioritized. In 2001, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended that special attention should be focused on the immunization status of incarcerated adolescents, as many of these youth lack a medical home [1].

A preventive vaccine for Human Papillomavirus (HPV), the most common sexually transmitted infection in the United States, was licensed in 2006 by the Food and Drug Administration. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends universal vaccination for females aged 11–26 [2]. The vaccine is optimally given prior to the onset of sexual activity, but is also beneficial and recommended for those who are sexually active.

Female youth within the juvenile justice system may be at particularly high risk for HPV and often lack a traditional medical home. Studies indicate both an earlier onset of sexual activity and an increased number of sexual partners among this population as compared with nationally reported rates of sexual activity among youth [1,3,4]. Youth in juvenile justice facilities could therefore benefit tremendously from HPV vaccination.

In 2007, we reported that 41 states were vaccinating juveniles in the juvenile justice system against hepatitis B virus (HBV) [5]. Similar to HBV, the juvenile justice setting provides a unique opportunity to administer the HPV vaccine to a high-risk, hard-to-reach population that may not seek health care services otherwise. In this study, State Immunization Program Managers were surveyed to ascertain current HPV vaccination practices in juvenile justice settings.

Methods

Semi-structured telephone interviews were conducted with State Immunization Program Managers, or when referred, with Department of Juvenile Justice medical personnel. Interviews were conducted from January to February, 2009.

Respondents were queried to determine (1) whether the HPV vaccine is offered to female adolescents within juvenile justice settings and whether it is offered to detained versus committed youth, (2) consent protocols for receipt of the HPV vaccine, and (3) barriers to administering the HPV vaccine.

Results

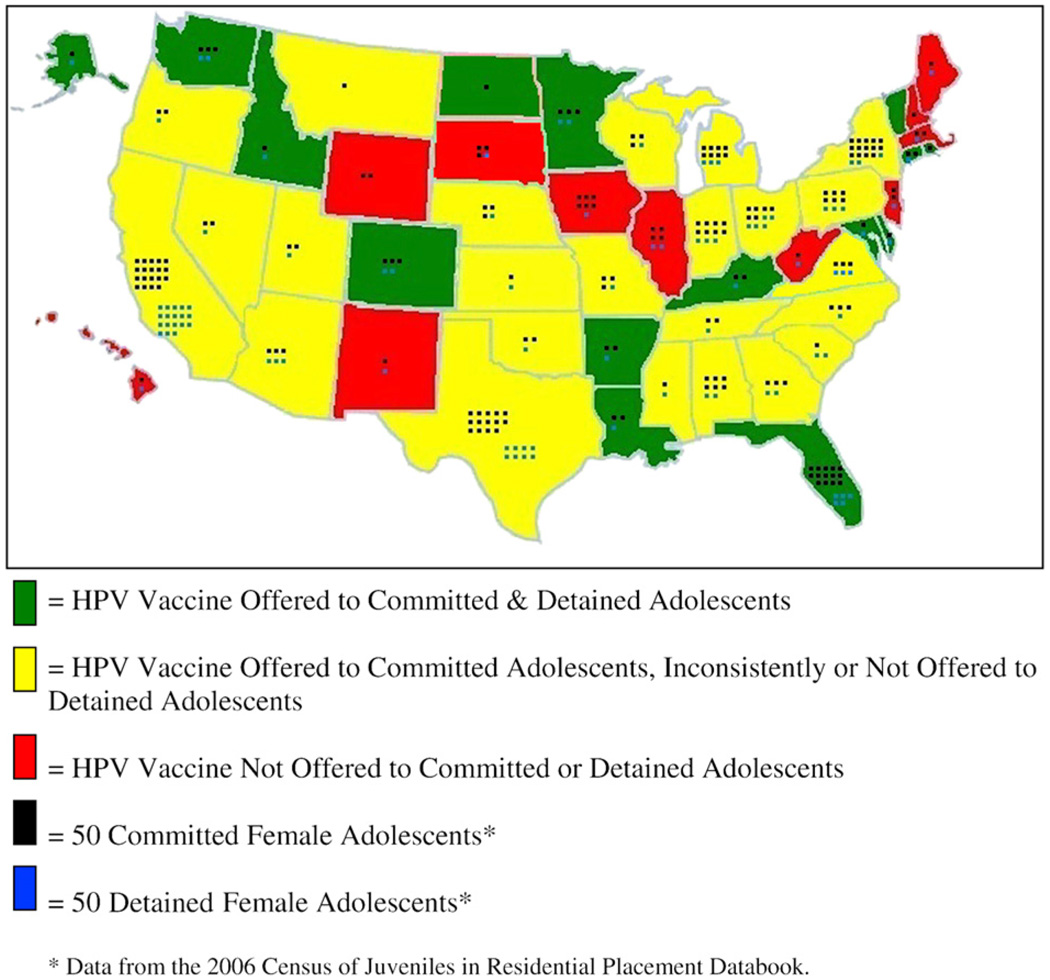

Surveys were successfully conducted with representatives from all 50 states. The HPV vaccine is currently offered to adolescents residing in juvenile justice facilities in 39 states and not offered in 11 states (see Figure 1). Fifteen states offer the HPV vaccine to both detained and committed adolescents. The vaccine is not offered to detained adolescents in 14 states; it is inconsistently offered to detained adolescents in 10 states. The most commonly cited reason for not vaccinating detained adolescents was the short length of stay.

Figure 1.

Current HPV vaccination practices, United States, 2009.

As depicted in Table 1, the state or facility superintendent is authorized to provide consent for vaccination of adolescents in 69% (n = 27) of the states that provide the HPV vaccine.

Table 1.

Persons authorized to provide HPV vaccine consent for adolescents residing in juvenile justice facilities in the 39 states offering HPV vaccination

| Parental consent only | Parental consent sought first, but state or facility superintendent can consent when not obtained |

State or facility superintendent consents on behalf of adolescent with adolescent’s agreement for vaccine receipt |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| HPV Vaccine Offered to Committed and Detained Adolescents |

Alaska | Maryland | Arkansas |

| Colorado* | Minnesota | Delaware | |

| Connecticut | Rhode Island | Idaho | |

| Florida | Kentucky | ||

| Louisiana | |||

| North Dakota | |||

| Vermont | |||

| Washington | |||

| HPV Vaccine Offered to Committed Adolescents; Inconsistently or Not Offered to Detained Adolescents |

Arizona | Alabama | California |

| Indiana | Georgia | ||

| Montana | Kansas | ||

| Pennsylvania | Michigan | ||

| Mississippi | |||

| Missouri | |||

| Nebraska | |||

| Nevada | |||

| New York | |||

| North Carolina | |||

| Ohio | |||

| Oklahoma | |||

| Oregon | |||

| South Carolina | |||

| Tennessee | |||

| Texas | |||

| Utah | |||

| Virginia | |||

| Wisconsin |

Colorado: State or facility superintendent consents for committed adolescents aged ≤ 18 years. Parental consent is required for detained adolescents.

Barriers to vaccine administration were identified among states administering the vaccine as well as states that do not currently administer the vaccine. Most commonly, survey respondents stated a general lack of education among adolescents regarding HPV vaccination. Other cited barriers included parental consent requirements (in states where parental consent is required [n = 5] or sought initially [n = 7]), a lack of adequate and consistent healthcare staff to administer the HPV vaccine, lack of refrigerated storage space for the HPV vaccine, general staff reluctance in administering the HPV vaccine, adolescents’ fear of needles, and cost.

Discussion

This is the first study of HPV vaccination practices among juvenile justice facilities. We had a 100% response rate from states and found that most states currently offer the HPV vaccine to adolescent females residing in juvenile justice facilities. However, in many of these states the HPV vaccine is offered only to committed youth and is not offered or inconsistently offered to detained youth. The primary reason given by respondents for not vaccinating detained youth was the short length of stay. Given the approximately 25,000 adolescents who pass through detention facilities annually [6] and their increased risk for HPV, vaccinating these individuals should be a priority. Providing at least the first HPV vaccine dose to detained youth, and for those released, linking them to community-based providers after release for the second and third vaccine doses, has the potential to significantly improve HPV vaccination rates among this population.

In most states that provide the vaccine, protocols allow the state or facility superintendent to consent for HPV vaccination with the adolescent’s agreement. To increase uptake of the HPV vaccine it may be beneficial for states that require parental consent or seek parental consent initially to move to more liberal consent protocols.

One of the primary barriers cited in this study was a general lack of education regarding HPV vaccination among adolescents. It is important to increase HPV vaccine educational efforts for adolescents in juvenile justice facilities.

Cost was also cited as a barrier in some states. The HPV vaccine is provided through the Center for Disease Control’s Vaccines for Children (VFC) program, as long as the juvenile justice facility is enrolled as a VFC provider [7]. Many juvenile justice facilities are enrolled as VFC providers and have access to vaccine through this program. Further research is necessary to examine reasons for non-VFC provider status among juvenile justice facilities.

One of the limitations of this study is that state immunization program managers were relied upon for accurate information regarding policy in their state and true practices of all individual facilities were not confirmed. However, state immunization program managers are in a position to be most knowledgeable about state policy. In addition, this study did not account for any adolescents residing in either adult correctional facilities or privately operated juvenile justice facilities.

The juvenile justice setting provides an important opportunity to administer the HPV vaccine to a high-risk, hard-to-reach population that might not otherwise receive the benefits of the vaccine. To maximize vaccine uptake, all states should make the HPV vaccine available, offer the vaccine universally to both detained and committed youth, and optimize consent protocols to allow for efficient vaccine delivery.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grant number K24DA022112 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health (NIDA/NIH) to Dr. Josiah D. Rich, and by grant number P30-AI-42853 from the National Institutes of Health, Center for AIDS Research (NIH/CFAR).

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Adolescence. Health care for children and adolescents in the juvenile correctional care system. Pediatrics. 2001;107:799–803. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.4.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Markowitz L, Dunne E, Saraiya M, et al. Quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine: Recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices. MMWR. 2007;56(RR-2):1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morris R, Harrison E, Knox G, et al. Health risk behavioral survey from 39 juvenile correctional facilities in the United States. J Adolesc Health. 1995;17:334–344. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(95)00098-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canterbury R, McGarvey E, Sheldon-Keller A, et al. Prevalence of HIV-related risk behaviors and STDs among incarcerated adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 1995;17:173–177. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(95)00043-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tedeschi S, Bonney L, Manalo R, et al. Vaccination in juvenile correctional facilities: State practices, hepatitis B, and the impact on anticipated sexually transmitted infection vaccines. Public Health Rep. 2007;122:44–48. doi: 10.1177/003335490712200106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Livesey S, Sickmund M, Sladky A. Washington, DC: United States Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; Juvenile Residential Facility Census, 2004: Selected Findings. 2009

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccines for Children Program. [Accessed March 25, 2009]; [Online]. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/vfc/default.htm.