Abstract

This study aimed to identify the incidence of adverse outcomes from ectopic pregnancy hospital care in Illinois (2000–2006), and assess patient, neighborhood, hospital and time factors associated with these outcomes. Discharge data from Illinois hospitals were retrospectively analyzed and ectopic pregnancies were identified using DRG and ICD-9 diagnosis codes. The primary outcome was any complication identified by ICD-9 procedure codes. Secondary outcomes were length of stay and discharge status. Residential zip codes were linked to 2000 U.S. Census data to identify patients’ neighborhood demographics. Logistic regression was used to identify risk factors for adverse outcomes. Independent variables were insurance status, age, co-morbidities, neighborhood demographics, hospital type, hospital ectopic pregnancy service volume, and year of discharge. Of 13,007 ectopic pregnancy hospitalizations, 7.4% involved at least one complication identified by procedure codes. Hospitalizations covered by Medicare (for women with chronic disabilities) were more likely than those with other source or without insurance to result in surgical sterilization (OR 4.7, P = 0.012). Hospitalization longer than 2 days was more likely with Medicaid (OR 1.46, P<0.0005) or no insurance (OR 1.35, P<0.0005) versus other payers, and among church-operated versus secular hospitals (OR 1.21, P<0.0005). Compared to public hospitals, private hospitals had lower rates of complications (OR 0.39, P< 0.0005) and of hospitalization longer than 2 days (OR 0.57, P<0.0005). With time, hospitalizations became shorter (OR 0.53, P<0.0005) and complication rates higher (OR 1.33, P = 0.024). Ectopic pregnancy patients with Medicaid, Medicare or no insurance, and those admitted to public or religious hospitals, were more likely to experience adverse outcomes.

Keywords: Ectopic pregnancy, Complications, Sterilization, Hospital care, Insurance status, Socioeconomic disparities

Introduction

Ectopic pregnancy occurs when a fertilized egg implants outside the lining of a woman’s uterus, most commonly in the fallopian tube. Unable to sustain a growing pregnancy, the fallopian tube or nearby organ can rupture and cause severe internal hemorrhage. Ectopic pregnancy is a leading cause of maternal mortality in the United States (1) and often leads to impaired fertility (2). Although advances in gynecologic ultrasound and human chorionic gonadotropin assays are facilitating earlier diagnosis and less invasive medical treatment for ectopic pregnancy (3), women with Medicaid or without insurance experience delays in access to timely care (4). In addition, non-white women are more likely to have ectopic pregnancies and more likely to die from the condition compared to white women (1, 5, 6).

Long-term consequences of ectopic pregnancy, such as impaired fertility and the risk of recurrence, can negatively impact women’s health, quality of life, and health care costs, as well as women’s psychological status(7). Short-term outcomes, such as hemorrhage or surgical complication, also contribute to morbidity but have not been well-quantified. Since 1992, traditional surveillance methods have been unable to provide reliable nation-wide ectopic pregnancy data because changes in practice require tracking patients through multiple sites of care (8). Researchers have analyzed ectopic pregnancy outcomes within specific providers (9–11), but new methods for studying ectopic pregnancy at the population level are needed. State-wide hospital databases represent a promising approach to surveillance (6).

We reviewed hospital discharge data to estimate the incidence and predictors of adverse outcomes from ectopic pregnancy hospitalizations and ambulatory surgery during 2000–2006 in Illinois, a large state with demographic similarity to the United States population (12).

Materials and Methods

Ambulatory surgery and inpatient discharge claims from the Illinois Hospital Association’s COMPdata files were examined (13). This database contains discharge information from all public and private Illinois hospitals (except Veterans’ Affairs facilities) and makes de-identified data available to investigators under approved research agreements. Emergency Department and outpatient (clinic or office) claims were not available, but outpatient surgical claims were included. Patient residential zip codes extracted from hospital claims were linked to 2000 United States Census data to identify the patient’s neighborhood demographics for each hospitalization.

Hospitals were classified based on standard categories using the American Hospital Association (AHA) guide to U.S. Hospitals (14). These categories included: public (government-controlled) versus private; church-operated versus other; and not-for-profit versus for-profit.

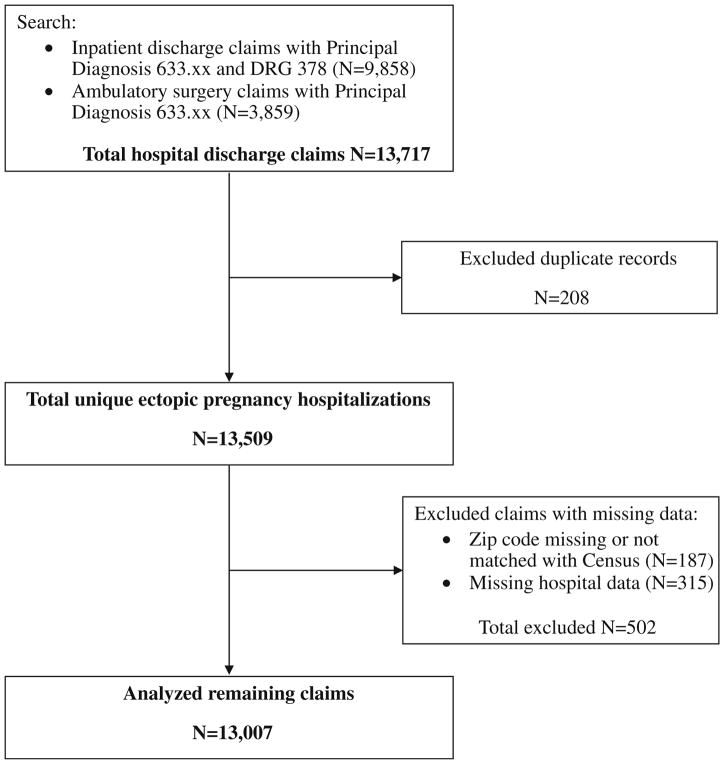

Ectopic pregnancy hospitalizations were identified by searching for claims with a principal International Classification of Diseases 9th Revision (ICD-9) diagnosis code of 633.xx (Fig. 1) (15). To increase case specificity, inpatient claims were also required to have a Diagnostic Related Group (DRG) code of 378 for ectopic pregnancy. Duplicate records were excluded in order to identify unique hospitalizations. For the sake of analysis, claims with missing or un-usable zip code or hospital data were also excluded.

Fig. 1.

Case identification

The primary outcome was complication rate. Complications were identified using ICD-9 procedure codes, with the aim of capturing all procedures that were likely to have resulted from late diagnosis or treatment or that indicated severe secondary morbidity. Codes were extracted from all procedure fields (principal, secondary and other). The two physician investigators reviewed all procedure codes found in the dataset and identified four categories of complications: transfusion, hysterectomy, surgical injury, and other complications. One of the physician investigators and an independent physician reviewer then sorted all ICD-9 procedure codes in the data files into one or more of these categories. Inter-rater agreement was calculated using the kappa statistic (16), and classified as none, slight, moderate, substantial, near-perfect or perfect according to standard classifications (17). The second physician investigator then independently adjudicated all coding discrepancies. A composite clinical outcome, surgical sterilization, was defined to include all hysterectomies plus all procedures that removed both or sole remaining fallopian tube or ovary.

Secondary outcomes were hospital length-of-stay (days) and in-hospital mortality. Clinical experience suggests that patients with uncomplicated ectopic pregnancy are typically discharged in one or 2 days; therefore, length-of-stay more than 2 days was defined as an adverse outcome. Deaths were identified by discharge status but hospital readmissions could not be identified due to lack of patient identifiers in the dataset.

Multivariable regression analysis was used to identify patient factors, hospital characteristics, and time trends associated with each outcome. Independent variables were: insurance status; zip code-level demographics (poverty rate, unemployment rate, population size, median household income, percent urban, and percent African-American); patient age and age-squared (in order to avoid the assumption of a linear age relationship); patient co-morbidities; hospital type (private versus public, church-operated versus other, not-for-profit versus for-profit); hospital ectopic pregnancy service volume (number of total ectopic pregnancy discharges during the study period); and year of discharge. Insurance status was defined by the primary payer on the hospital claim. Co-morbidities were identified by the presence of ICD-9 diagnosis codes for chronic illnesses previously shown to increase pregnancy-related and hospital complications: diabetes mellitus (250–250.7) and chronic pulmonary disease (490–496, 500–505, 506.4) (18–21). Patient race data were not available.

Complications (present versus absent) and length-ofstay (greater than 2 days versus 2 days or less) were analyzed as dichotomous outcome variables using logit regression models. All analyses were conducted using STATA/SE10 (College Station, TX).

The study was designated exempt by the authors’ Institutional Review Board.

Results

The dataset contained 13,509 unique hospitalizations for ectopic pregnancy in 139 Illinois hospitals during 2000–2006. Based on the 2000 U.S. Census (22) and 2000–2006 Illinois birth certificate data (23), the annual state incidence of ectopic pregnancy hospitalizations was 5.4 per 10,000 women at risk (ages 13–50), or 10.6 per 1,000 births. Of these, 13,007 claims had complete data for analysis. Table 1 describes these discharges.

Table 1.

Ectopic pregnancy discharges (Illinois), 2000–2006

| Patient’s age (years) | |

| Mean (SD) | 29.1 (6.1) |

| Range | 13–50 |

| Co-morbidities | Number (%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 76 (0.6) |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 430 (3.3) |

| Insurance status | Number (%) |

| Private | 7,353 (56.6) |

| Medicaid | 3, 700 (28.5) |

| Medicare | 61 (0.5) |

| Charity care | 34 (0.3) |

| Self-payment | 1,458 (11.2) |

| Others | 401 (3.1) |

| Type of hospital | Number (%) |

| Private (vs. public) | 12,274 (94.4) |

| Non-profit (vs. profit) | 11,188 (86.0) |

| Church-operated (vs. other) | 4,458 (34.4) |

| Length-of-stay (days) | |

| Mean (SD) | 1.7 (1.4) |

| Range | 0–32 |

N = 13,007

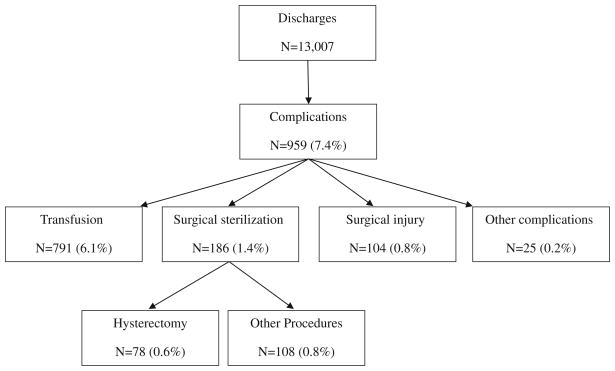

Fifty-eight unique ICD-9 procedure codes were identified as complications (Table 2). Among all discharges for ectopic pregnancy, 7.4% involved at least one type of complication (Fig. 2). Inter-rater agreement on categorization of complications was moderate for Surgical Injury (κ = 0.43), substantial for Hysterectomy (κ = 0.85), and perfect for Transfusion (κ = 1.00). For Other Complications, inter-rater agreement was 94.9%, the same as that predicted by chance (κ = −0.01).

Table 2.

Procedures identified as complications from ectopic pregnancy hospital claims

| ICD-9 Code | Procedure |

|---|---|

| Transfusion | |

| 99.00 | Perioperative autologous transfusion of whole blood or blood components |

| 99.01 | Exchange transfusion |

| 99.03 | Other transfusion of whole blood |

| 99.04 | Transfusion of packed cells |

| 99.05 | Transfusion of platelets |

| 99.07 | Transfusion of other serum |

| 99.09 | Transfusion of other substance: blood surrogate, granulocytes |

| Surgical sterilization | |

| 65.52 | Other removal of remaining ovary |

| 65.61 | Other removal of both ovaries and tubes at same operative episode |

| 65.62 | Other removal of remaining ovary and tube |

| 65.63 | Laparoscopic removal of both ovaries and tubes at same operative episode |

| 65.64 | Laparoscopic removal of remaining ovary and tube |

| 66.51 | Removal of both fallopian tubes at same operative episode |

| 66.52 | Removal of remaining fallopian tube |

| 68.3 | Subtotal abdominal hysterectomy |

| 68.39 | Other subtotal abdominal hysterectomy |

| 68.4 | Total abdominal hysterectomy |

| 68.51 | Laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy (LAVH) |

| 68.8 | Pelvic evisceration |

| 68.9 | Other and unspecified hysterectomy |

| 69.19 | Other excision or destruction of uterus and supporting structures |

| Surgical injury | |

| 39.0 | Systemic to pulmonary artery shunt |

| 39.1 | Intra-abdominal venous shunt |

| 39.2 | Other shunt or vascular bypass |

| 39.59 | Other repair of vessel |

| 39.98 | Control of hemorrhage, not otherwise specified |

| 41.95 | Repair and plastic operations on spleen |

| 45.02 | Other incision of small intestine |

| 45.03 | Incision of large intestine |

| 45.41 | Excision of lesion or tissue of large intestine |

| 45.62 | Other partial resection of small intestine |

| 46.01 | Exteriorization of small intestine |

| 46.73 | Suture of laceration of small intestine, except duodenum |

| 46.75 | Suture of laceration of large intestine |

| 46.79 | Other repair of intestine |

| 54.12 | Reopening of recent laparotomy site |

| 54.61 | Reclosure of postoperative disruption of abdominal wall |

| 57.59 | Open excision or destruction of other lesion or tissue of bladder |

| 57.81 | Suture of laceration of bladder |

| 67.61 | Suture of laceration of cervix |

| 69.41 | Suture of laceration of uterus |

| 75.61 | Repair of current obstetric laceration of bladder and urethra |

| 86.22 | Excisional debridement of wound, infection, or burn |

| Other complications | |

| 33.1 | Incision of lung |

| 34.04 | Insertion of intercostal catheter for drainage |

| 38.7 | Interruption of the vena cava |

| 39.79 | Other endovascular repair (of aneurysm) of other vessels |

| 39.97 | Other perfusion |

| 45.49 | Other destruction of lesion of large intestine |

| 54.0 | Incision of abdominal wall |

| 54.92 | Removal of foreign body from peritoneal cavity |

| 55 | Operations on kidney |

| 58.6 | Dilation of urethra |

| 59.09 | Other incision of perirenal or periureteral tissue |

| 59.8 | Ureteral catheterization |

| 75.8 | Obstetric tamponade of uterus or vagina |

| 96.6 | Enteral infusion of concentrated nutritional substances |

| 99.15 | Parenteral infusion of concentrated nutritional substances |

Fig. 2.

Documented complications among hospital claims for ectopic pregnancy, percent of all discharges. Numbers of specific complications sum to greater than 959 because some patients experienced more than one complication

Hospital length of stay ranged from 0–32 days, with a mean of 1.7 days. More than three quarters of admissions (77%) were 2 days or fewer in length. Nearly all admissions (92%) included a surgical procedure, in most cases (72%) salpingectomy. Due to the limitations of ICD-9 procedure codes, there was inability to consistently distinguish between laparoscopic versus open surgical procedures. The procedure code for conversion of a laparoscopic procedure to an open procedure (V64.4) was not documented in any discharge claim in this database. Review of discharge status data revealed only one death, giving an in-hospital mortality ratio of 0.74 per 10,000 claims. Two additional admissions were discharged to hospice and two to a skilled nursing facility.

The results of the multivariate analyses predicting complications and length-of-stay are shown in Table 3. Controlling for age, co-morbidities, neighborhood sociodemographics, year of discharge, hospital type, and service volume, insurance status was significantly associated with both length-of-stay and complications. Hospitalizations longer than 2 days were more common among those with Medicaid (OR 1.46, 95% CI 1.32–1.62) or self-pay status (OR 1.35, 95% CI 1.16–1.56) than among other insurance sources. Compared with all other payers, hospitalizations covered by Medicare had a higher chance of resulting in surgical sterilization (OR 4.7, 95% CI 1.4–15.5). In addition, patients with chronic pulmonary disease had significantly greater odds of a complication (OR 1.41, 95% CI 1.02–1.96) than those without. Chronic pulmonary disease (OR 1.65, 95% CI 1.33–2.04) and diabetes (OR 1.79, 95% CI 1.11–2.90) were both associated with longer hospitalization.

Table 3.

Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy complications or hospitalization longer than 2 daysa

| Any complication OR (95% CI) | Surgical sterilization OR (95% CI) | Length-of-stay > 2 days OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | |||

| Co-morbidities | |||

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 1.41 (1.02–1.96)b | 1.01 (0.44–2.30) | 1.65 (1.33–2.04)b |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.46 (0.72–2.99) | 0.64 (0.09–4.75) | 1.79 (1.11–2.90)b |

| Insurance status | |||

| Private insurance | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Medicaid | 1.15 (0.98–1.35) | 1.34 (0.92–1.95) | 1.46 (1.32–1.62)b |

| Medicare | – | 4.7 (1.4–15.5)b | 1.02 (0.55–1.91) |

| Self-payment | 1.22 (0.97–1.53) | 1.51 (0.92–2.45) | 1.35 (1.16–1.56)b |

| Charity care | – | 3.90 (0.88–17.23) | 0.89 (0.34–2.35) |

| Others | 0.89 (0.58–1.36) | 0.97 (0.39–2.43) | 1.54 (1.22–1.94)b |

| Hospital type | |||

| Private | 0.39 (0.25–0.61)b | 0.48 (0.18–1.25) | 0.57 (0.42–0.76)b |

| Church-operated | 1.13 (0.98–1.31) | 0.75 (0.53–1.07) | 1.21 (1.10–1.33)b |

| Non-profit | 0.96 (0.91–1.01) | 0.99 (0.88–1.11) | 0.98 (0.95–1.02) |

| Discharge year | |||

| 2000 | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| 2001 | 0.99 (0.76–1.29) | 0.84 (0.50–1.40) | 0.90 (0.77–1.05) |

| 2002 | 1.15 (0.89–1.49) | 0.78 (0.46–1.34) | 0.80 (0.68–0.93)b |

| 2003 | 1.26 (0.98–1.62) | 0.82 (0.49–1.36) | 0.89 (0.76–1.03) |

| 2004 | 1.11 (0.85–1.44) | 0.65 (0.37–1.13) | 0.78 (0.66–0.91)b |

| 2005 | 1.34 (1.04–1.72)b | 0.98 (0.60–1.62) | 0.69 (0.59–0.81)b |

| 2006 | 1.33 (1.04–1.71)b | 0.56 (0.32–1.01) | 0.53 (0.45–0.63)b |

Table reports results of multivariable regression models, controlling also for zip code demographics, patient age, age squared, and hospital ectopic pregnancy service volume

P < 0.05

Hospital factors also proved significant. Private hospitals had lower odds of complications compared with public (OR 0.39, 95% CI 0.25–0.61). Length-of-stay more than 2 days was significantly less likely among private hospitals (OR 0.57, 95% CI 0.42–0.76) and more likely among church-operated hospitals compared with others (OR 1.21, 95% CI 1.10–1.33). While surgical treatment was common in all hospitals (since the dataset excluded office and emergency department care), in bivariate Chi-square analysis, surgical treatment was significantly more common at church-operated hospitals (93.0% of all claims) compared with non-church-operated (91.8%, P = 0.02).

Finally, from the beginning of the study period to the end, complication rates increased while hospital length-of-stay shortened. Compared with the year 2000, discharges occurring in 2006 had a significantly higher odds of complication (OR 1.33, 95% CI 1.04–1.71) and lower odds of hospital stay greater than 2 days (OR 0.53, 95% CI 0.45–0.63).

Discussion

In this study of hospital-based care for ectopic pregnancy in Illinois, patient insurance status, co-morbidities, type of hospital, and year of discharge were all significantly associated with patient outcomes. Patients with Medicaid, Medicare or no insurance, those with chronic diseases, and those admitted to public or religious hospitals, were more likely to experience adverse outcomes.

Low rates of chronic disease were found among ectopic pregnancy patients, supporting the idea that pregnancy complications often affect otherwise healthy women (24). However, ectopic pregnancy, like other causes of acute hospitalization, tends to require longer hospitalization and result in worse outcomes when the patient has underlying diabetes or lung disease. Ectopic pregnancy was recorded among a wide age range (13–50 years) of the patients, which suggests that future research may need to expand the traditional definition of reproductive age (often 15–44 years). As with other causes of maternal mortality (25), morbidity data on ectopic pregnancy has been lacking. The finding of a 7.4% complication rate in this study is likely an underestimation, since it relied on documented procedures. However, no prior studies reporting U.S. ectopic pregnancy hospital complication rates were found.

Women who die from ectopic pregnancy often present with rupture and rapid clinical deterioration (5, 11). In our study, transfusion was the most commonly documented type of complication. We could not distinguish between transfusions needed due to the patient’s baseline status and those resulting from surgical complications; among patients with severe anemia or significant acute blood loss, transfusion is a necessary, often life-saving intervention. However, since there were no ICD-9 codes to distinguish ruptured from intact ectopic pregnancy, we report transfusion rate as a proxy to estimate the rate of clinically significant hemorrhage. The next most common complication was surgical sterilization. Women report undesired infertility to be one of the most distressing life experiences (26). We cannot rule out that some claims represented voluntary sterilization or procedures on patients who had previously undergone voluntary sterilization. However, the ICD-9 procedure codes for fallopian tube removal that we identified as complications (66.51, 66.52) specifically exclude partial salpingectomy for sterilization and are distinct from codes for the tubal destruction or occlusion procedures (66.2 and 66.3) most commonly used for sterilization (15, 27).

Low-income women have disproportionately high rates of unintended pregnancy (28) and overall pregnancy-associated hospitalization (29). Insurance and income barriers have also been identified in previous studies as factors contributing to late entry to prenatal care (30). In general, uninsured patients have been found to delay seeking preventive care and thus require costlier care for advanced illness (31). This study noted a correlation between Medicaid or self-pay status and longer hospitalizations, even controlling for other socioeconomic indicators; this suggests that both lack of insurance and coverage by Medicaid present barriers to timely care, and ultimately increase both cost and burden on the patient. In addition, neighborhood demographics by zip code were found in multivariate analysis to be significantly associated with outcomes: patients from more urban and African American zip codes, as well as zip codes with higher unemployment rates, experienced longer hospitalizations than others. This finding further suggests that socioeconomic status affects outcomes of ectopic pregnancy.

It was of concern to find admissions covered by Medicare, which in the population younger than age 65 represents chronically disabled persons (32), with a higher rate of surgical sterilization. While involuntary sterilization of disabled women was common in the past, it is rarely ethically accepted today (33, 34). The increased sterilization observed among Medicare admissions for ectopic pregnancy may reflect a higher prevalence of undesired fertility in this population or delayed access to care requiring more aggressive surgical treatment. To better understand sterilization as a complication in ectopic pregnancy, this finding merits further study, which should ideally involve prospective clinical observation.

The in-hospital mortality that we observed was lower than prior reports of overall ectopic pregnancy mortality. The last reported nationwide data showed ectopic pregnancy deaths at 3.8 per 10,000 cases in 1989 (1). However, our findings cannot be interpreted as a true mortality rate since most ectopic pregnancy deaths do not occur in the hospital (5). Hospital characteristics also proved significant in our analysis. The association of longer hospitalizations with hospital church affiliation may reflect different practice patterns based on religious teaching. Methotrexate is interpreted by some religious ethicists as equivalent to abortion (35), possibly explaining the higher rate of surgical treatment. Rates of medical management are likely under-represented in this study, since it only examined hospital-based care. Physician and patient preference for surgical versus medical management could not be taken into account given the limits of administrative data. Finally, our analysis found a trend towards shorter hospitalizations with higher complication rates over time. This may reflect growing economic pressures to admit only the sickest patients and discharge them quickly.

This study contributes to the current understanding of ectopic pregnancy outcomes by defining and quantifying adverse outcomes of hospital care, and identifying risk factors for these outcomes. Some of the key points of this study are the inclusion of all ectopic pregnancy admissions from the state and information about all payers; while the main limitation is the availability of claims for only hospital care, since many ectopic pregnancies are now cared for on an outpatient basis. There were also no patient identifiers, so the analysis was per admission and not per patient. The possibility that some patients were admitted more than once in a single episode of ectopic pregnancy could therefore not be excluded. The incidence and ratio (per births) reported here for the state of Illinois represent not ectopic pregnancy cases but ectopic pregnancy hospitalizations; furthermore, abortion data were not calculated in the denominator, so the ratio does not represent ectopic pregnancies per total reported pregnancies. Finally, the study lacked individual chart review to validate the claims data or provide more complete patient histories. While ICD-9 diagnosis and procedure codes have been found accurate in other research, it could not be guaranteed that the procedures identified were true complications or that the findings obtained in this study could be confirmed if there had been access to patient charts (36, 37). Furthermore, we cannot identify the causes of patients’ ectopic pregnancies in our sample; clinical factors such as a history of smoking, pelvic inflammatory disease, or assisted reproductive technology are relevant for patient outcomes but cannot be deduced from claims data.

The availability of outpatient medical management for ectopic pregnancy is one of gynecology’s greatest advances of the past decades. This study demonstrates, however, that hospitalization and surgery for ectopic pregnancy remain important causes of maternal morbidity. Interventions to improve access to pre-conception and prenatal care among vulnerable populations, and to timely advanced care when ectopic pregnancy is suspected, may offer the best hope of allowing all women to benefit equally from early, safe treatment.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the Chicago Center of Excellence in Health Promotions Economics. The funder had no involvement in study design, data collection or analysis, or manuscript preparation. The authors thank Kathleen Rowland, MD, for serving as independent data coder, Peter Burkiewicz for technical assistance with the dataset, and Irma Hasham for general research assistance.

Contributor Information

Debra B. Stulberg, Email: stulberg@uchicago.edu, Department of Family Medicine, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA. MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA. 5841 South Maryland Avenue, MC 7110, Room M-156, Chicago, IL 60637, USA

James X. Zhang, Email: xzhang3@vcu.edu, Department of Pharmacotherapy and Outcomes Science, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, USA. Department of Healthcare Policy and Research, Virginia Commonwealth University, 209E McGuire Hall, PO Box 980533, Richmond, VA 23298, USA

Stacy Tessler Lindau, Email: slindau@babies.bsd.uchicago.edu, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA. MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA. Department of Medicine, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA. 5841 South Maryland Avenue, MC 2050, Chicago, IL 60637, USA.

References

- 1.Goldner TE, Lawson HW, Xia Z, Atrash HK. Surveillance for ectopic pregnancy—United States, 1970–1989. MMWR CDC surveillance summaries. 1993;42(6):73–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ego A, Subtil D, Cosson M, Legoueff F, Houfflin-Debarge V, Querleu D. Survival analysis of fertility after ectopic pregnancy. Fertility and Sterility. 2001;75(3):560–566. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(00)01761-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seeber BE, Barnhart KT. Suspected ectopic pregnancy. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2006;107(2 Pt 1):399–413. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000198632.15229.be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asplin BR, Rhodes KV, Levy H, Lurie N, Crain AL, Carlin BP, et al. Insurance status and access to urgent ambulatory care follow-up appointments. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;294(10):1248–1254. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.10.1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson FW, Hogan JG, Ansbacher R. Sudden death: Ectopic pregnancy mortality. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2004;103(6):1218–1223. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000127595.54974.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calderon JL, Shaheen M, Pan D, Teklehaimenot S, Robinson PL, Baker RS. Multi-cultural surveillance for ectopic pregnancy: California 1991–2000. Ethnicity and Disease. 2005;15(4 Suppl 5):20–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mol F, Strandell A, Jurkovic D, Yalcinkaya T, Verhoeve HR, Koks CA, et al. The ESEP study: Salpingostomy versus salpingectomy for tubal ectopic pregnancy; the impact on future fertility: A randomised controlled trial. BMC Womens Health. 2008;8:3–11. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-8-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zane SB, Kieke BA, Jr, Kendrick JS, Bruce C. Surveillance in a time of changing health care practices: Estimating ectopic pregnancy incidence in the United States. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2002;6(4):227–236. doi: 10.1023/a:1021106032198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Den Eeden SK, Shan J, Bruce C, Glasser M. Ectopic pregnancy rate and treatment utilization in a large managed care organization. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2005;105(5 Pt 1):1052–1057. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000158860.26939.2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nelson AL, Adams Y, Nelson LE, Lahue AK. Ambulatory diagnosis and medical management of ectopic pregnancy in a public teaching hospital serving indigent women. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2003;188(6):1541–1547. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.387. (discussion 1547–1550) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bickell NA, Bodian C, Anderson RM, Kase N. Time and the risk of ruptured tubal pregnancy. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2004;104(4):789–794. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000139912.65553.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lindau ST, Tetteh AS, Kasza K, Gilliam M. What schools teach our patients about sex: Content, quality, and influences on sex education. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2008;111(2 Pt 1):256–266. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000296660.67293.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Illinois Hospital Association. [Accessed on 18 Jan 2010.];Welcome to COMPdata. 2010 http://www.compdatainfo.com/

- 14.American Hospital Association. AHA guide to the health care field. 2009. Chicago: American Hospital Association; 2008. Hospitals in the United States by state: Illinois; p. A162. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hart AC, Hopkins CA, Ford B. The international classification of diseases, ninth revision, clinical modification, 2006 professional for hospitals. Salt Lake City, UT: Ingenix; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hulley SB, Cummings SR, Browner WS, Grady D, Hearst N, Newman TB. Designing clinical research. 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Williams; 2001. Calculation of kappa to measure interobserver agreement; pp. 192–193. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGinn T, Wyer PC, Newman TB, Keitz S, Leipzig R, For GG, et al. Tips for learners of evidence-based medicine: 3. measures of observer variability (kappa statistic) CMAJ. 2004;171(11):1369–1373. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1031981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1992;45(6):613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ehrenthal DB, Jurkovitz C, Hoffman M, Kroelinger C, Weintraub W. A population study of the contribution of medical comorbidity to the risk of prematurity in blacks. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2007;197(4):409.e1–409.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu S, Wen SW, Demissie K, Marcoux S, Kramer MS. Maternal asthma and pregnancy outcomes: A retrospective cohort study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2001;184(2):90–96. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.108073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vavlukis M, Georgievska-Ismail LJ, Bosevski M, Borozanov V. Predictors of in-hospital morbidity and mortality in patients with coronary artery disease treated with coronary artery bypass surgery. Prilozi. 2006;27(2):97–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.United States Census Bureau. [Accessed 18 Jan 2010.];Census 2000 summary file 1. 2010 http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/DTTable?_bm=y&-context=dt&-ds_name=DEC_2000_SF1_U&-mt_name=DEC_2000_SF1_U_P012&-CONTEXT=dt&-tree_id=4001&-all_geo_types=N&-geo_id=04000US17&-search_results=01000US&-format=&-_lang=en.

- 23.Illinois Department of Public Health. [Accessed 18 Jan 2010];Births by county of residence. 2000–2006 http://www.idph.state.il.us/health/bdmd/birth2.htm.

- 24.Atrash HK, Alexander S, Berg CJ. Maternal mortality in developed countries: Not just a concern of the past. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1995;86(4 Pt 2):700–705. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00200-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berg CJ, Bruce FC, Callaghan WM. From mortality to morbidity: The challenge of the twenty-first century. J Am Med Womens Assoc. 2002;57(3):173–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lukse MP, Vacc NA. Grief, depression, and coping in women undergoing infertility treatment. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1999;93(2):245–251. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00432-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nardin JM, Kulier R, Boulvain M. Techniques for the interruption of tubal patency for female sterilisation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2003;(1):CD003034. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Finer LB, Henshaw SK. Disparities in rates of unintended pregnancy in the United States, 1994 and 2001. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2006;38(2):90–96. doi: 10.1363/psrh.38.090.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bacak SJ, Callaghan WM, Dietz PM, Crouse C. Pregnancy-associated hospitalizations in the United States, 1999–2000. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2005;192(2):592–597. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.10.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Entry into prenatal care—United States, 1989–1997. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2000;49(18):393–398. [Google Scholar]

- 31.McWilliams JM, Meara E, Zaslavsky AM, Ayanian JZ. Use of health services by previously uninsured medicare beneficiaries. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357(2):143–153. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa067712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.United States Department of Health and Human Services. [Accessed 18 Jan 2010.];General enrollment and eligibility. 2010 http://www.medicare.gov/MedicareEligibility/Home.asp?dest=NAV|Home|GeneralEnrollment#TabTop.

- 33.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Ethics. Sterilization of women, including those with mental disabilities. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2007;110(1):217–220. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000263915.70071.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Powderly KE. Contraceptive policy and ethics: Illustrations from american history. Hastings Center Report. 1995;25(1):S9–S11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pivarunas AR. Ethical and medical considerations in the treatment of ectopic pregnancy. Linacre Quarterly. 2003;70(3):195–209. doi: 10.1080/20508549.2003.11877678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Virnig BA, McBean M. Administrative data for public health surveillance and planning. Annual Review of Public Health. 2001;22:213–230. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.22.1.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lawthers AG, McCarthy EP, Davis RB, Peterson LE, Palmer RH, Iezzoni LI. Identification of in-hospital complications from claims data. Is it valid? Medical Care. 2000;38(8):785–795. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200008000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]