Abstract

The etiology of major depression (MDD), a common and complex disorder, remains obscure. Gene expression profiling was conducted on post-mortem brain tissue samples from Brodmann Area 10 (BA10) in the prefrontal cortex from psychotropic drug-free persons with a history of MDD and age, gender, and post-mortem interval matched normal controls (n=14 pairs of subjects). Microarray analysis was conducted using the Affymetrix Exon 1.0 ST arrays. A list of differential expression changes were determined by dual fold change-probability criteria (|ALR|>0.585 [equivalent to a 1.5-fold difference in either direction], p<0.01), while molecular pathways of interest were evaluated using Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) software. The results strongly implicate increased apoptotic stress in the samples from the MDD group. Three anti-apoptotic factors, Y-box binding protein 1 (YBX1), Caspase-1 dominant-negative inhibitor pseudo-ICE (COP1), and the putative apoptosis inhibitor FKGS2 were over-expressed. Gene set analysis suggested up-regulation of a variety of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin 1α (IL1α), IL2, IL3, IL5, IL8, IL9, IL10, IL12A, IL13, IL15, IL18, interferon gamma (IFNγ), and lymphotoxin alpha (LTA; TNF super family member 1). The genes showing reduced expression included metallothionein 1M (MT1M), a zinc binding protein with a significant role in the modulation of oxidative stress. The results of this study suggest that post-mortem brain tissue samples from BA10, a region which is involved in reward-related behavior, show evidence of local inflammatory, apoptotic, and oxidative stress in MDD.

Keywords: Major depression, microarray, transcriptome profiling, frontal cortex, gene expression, inflammation, apoptosis, cytokines, oxidative stress

INTRODUCTION

A variety of brain imaging, post-mortem morphometric, and other studies suggest that major depression involves abnormalities of cortico-limbic structures, including prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulated, amygdala, and hippocampus.1 In spite of the fact that there is considerable evidence suggesting an underlying neurobiology for major depression (MDD), the molecular basis has been elusive. A number of gene expression profiling studies in post-mortem brain tissue have been conducted comparing depressed and control samples, with variable results. 2–9 Transcriptome profiling is a powerful, albeit complex method, which is affected by a number of factors, including accuracy of the pre-mortem diagnosis; peri-mortem characteristics such as cause of death, the presence of prolonged agonal states, the presence of drugs or toxins;10;11 postmortem factors such as the post-mortem interval, pH, and RNA integrity; processing methods, and other issues. Even when controlling for all of these variables, contemporary microarrays provide enormous amounts of data, creating challenges in data handling. Further, MDD is not a unitary condition and is likely to comprise a range of clinical phenotypes and endophenotypes, which may affect the results of microarray analysis.

The present study was aimed at conducting gene expression analysis of a brain area, BA10, which was chosen for several reasons. First, BA10 has been shown to be significantly involved in the mediation of reward related behavior, which is central to the clinical phenomenology of depression12. For example, Rogers et al.12 showed that a task which involved choices between high probability – low reward versus low probability – high reward options resulted in the activation of three adjacent regions in the orbito-frontal cortex, BA10, BA11, and BA47 using [15O] positron emission tomography. Cocaine13 and amphetamine14, highly reinforcing substances, have also been shown to produce activation of BA10. Kufahl et al.13 showed that cocaine administration resulted in decreased fMRI brain oxygen level dependent (BOLD) signal in ventral tegmental area (VTA), nucleus accumbens, subcallosal cortex, ventral pallidum, amygdala, parahippocampal gyrus, posterior orbital gyrus, inferior and superior temporal gyrus, but marked and sustained increases in BOLD signal in BA10 and 11. Similarly, amphetamine administration increased BA8 and 10 activities as measured by single photon emission tomography14. These data suggest that BA10 is involved in reward and reinforcement processing, a core dysfunction in depression15;16.

Only one prior study has evaluated gene expression in post-mortem tissue samples from BA10 in MDD compared with controls.17 This study found 99 differentially-expressed genes, which including sets of transcripts of genes involved in cell proliferation. Most of the altered genes are of unknown significance with regard to MDD. However, one up-regulated transcript, fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1) may be significant; the expression of both FGFR118 and its endogenous ligands FGF1 and FGF23 had previously been shown to be altered in MDD samples.

The present study investigated post-mortem brain tissue samples from 14 depressed persons who were psychotropic drug free at the time of death and age and sex -matched normal controls. Eleven of the 14 samples were from persons who met full DSM-IV criteria for MDD, melancholic subtype antemortem. The melancholic subtype is a distinct clinical phenotype, characterized by symptoms of hyperarousal (e.g., insomnia and anorexia) and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activation19 that may persist even after successful treatment.20 The Affymetrix Exon 1.0 ST array was used for assessing expression of gene transcripts using mRNA of high integrity. In addition to the gene expression analysis, molecular pathways of interest were evaluated using Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) to determine altered expression of sets of genes implicated in depression. The results showed altered expression of a large number of genes, but specifically demonstrated upregulation of the expression of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines and specific anti-apoptotic factors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human Brain Samples and Tissue Preparation

All procedures were approved by the University of Pittsburgh’s Committee for the Oversight of Research Involving the Dead and Institutional Review Board for Biomedical Research and the Vanderbilt University Health Sciences Institutional Review Board. Fresh-frozen brain specimens were obtained during routine autopsies conducted by a medical examiner after consent for tissue donation was given by the next of kin. Samples were obtained from 14 pairs of persons with major depressive disorder (MDD) and control (CTR) postmortem brains matched for sex and race, and as closely as possible for age (MDD=47.2 [SD=14.0] and CTR=48.9 [SD=12.1] respectively), and postmortem interval (PMI) (17.8 [SD=7.6] hours and 17.8 [SD=6.5] hours respectively) (all values mean ± SD)(Table 1). Depressed and control subject brain pH (6.59 [SD=0.30] and 6.71 [SD=0.26] respectively) and RNA integrity number (RIN; greater than 7 for all subjects) were also assessed (Table 1). There were no statistically significant differences in age, PMI, pH, or RIN between groups. All samples came from persons free from all known psychotropic agents and recent substance abuse. Blood samples for toxicology were obtained at the time of the brain collection; all participants were confirmed to be free of psychotropic medications except for one control subject who tested positive for temazepam. Toxicology results are listed in Table 1. The brain samples were collected through the local medical examiner’s office and all patients died a non-hospitalized, acute death, with virtually no agonal state that could bias the gene expression measurements.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics.

| Subject jnumber | Group | Pair | Sex | Race | Age | PMI (hours) | pH | Cause of Death | Manner of Death | Blood Toxicology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 600 | MDD | 1 | M | W | 63 | 9.9 | 6.72 | Hanging | Suicide | None |

| 613 | MDD | 2 | M | W | 59 | 15.6 | 6.95 | Gunshot wound | Suicide | None |

| 668 | MDD | 3 | M | W | 34 | 24.3 | 7.00 | Hanging | Suicide | None |

| 699 | MDD | 4 | M | W | 65 | 5.5 | 6.71 | Gunshot wound | Suicide | None |

| 735 | MDD | 5 | F | W | 40 | 14.0 | 6.84 | Pulmonary embolism | Accidental | None |

| 927 | MDD | 6 | M | W | 58 | 24.9 | 6.11 | ASCVD | Natural | None |

| 949 | MDD | 7 | M | W | 38 | 25.0 | 6.23 | Cardiac arrhythmia | Natural | None |

| 1028 | MDD | 8 | M | W | 39 | 14.5 | 6.18 | Gunshot wound | Suicide | None |

| 1053 | MDD | 9 | M | W | 47 | 24.0 | 6.57 | ASCVD | Natural | Lidocaine |

| 1131 | MDD | 10 | M | W | 29 | 26.6 | 6.92 | Gunshot wound | Suicide | None |

| 1186 | MDD | 11 | M | W | 45 | 6.6 | 6.25 | Traumatic asphyxiation | Accidental | None |

| 1215 | MDD | 12 | M | W | 44 | 11.0 | 6.54 | ASCVD | Natural | None |

| 1221 | MDD | 13 | F | B | 28 | 24.8 | 6.61 | Pulmonary embolism | Natural | None |

| 10028 | MDD | 14 | F | W | 72 | 23.1 | 6.66 | Gunshot wound | Suicide | Ibuprofen |

| MDD Mean (SD): | 47.2 (14.0) | 17.8 (7.6) | 6.59 (6.46) | |||||||

| 510 | CONTROL | 1 | M | W | 63 | 12.4 | 6.51 | GI hemorrhage | Natural | None |

| 685 | CONTROL | 2 | M | W | 56 | 14.5 | 7.06 | Coronary artery disease | Natural | Alcohol (0.01%) |

| 694 | CONTROL | 3 | M | W | 38 | 20.7 | 6.73 | Subarachnoid hemorrhage | Natural | None |

| 615 | CONTROL | 4 | M | W | 62 | 7.2 | 6.39 | Ruptured aortic aneurysm | Natural | None |

| 567 | CONTROL | 5 | F | W | 46 | 15.0 | 6.77 | Mitral valve prolapse | Natural | None |

| 902 | CONTROL | 6 | M | W | 60 | 23.6 | 6.74 | ASCVD | Natural | None |

| 700 | CONTROL | 7 | M | W | 42 | 26.1 | 6.95 | ASCVD | Natural | None |

| 1047 | CONTROL | 8 | M | W | 43 | 13.8 | 6.63 | ASCVD | Natural | Chlorphen-iramine |

| 643 | CONTROL | 9 | M | W | 50 | 24.0 | 6.23 | ASCVD | Natural | None |

| 789 | CONTROL | 10 | M | W | 22 | 20.0 | 7.04 | Asphyxiation | Accidental | None |

| 1067 | CONTROL | 11 | M | W | 49 | 6.5 | 6.55 | Hypertensive heart disease | Natural | Doxylamine, metoprolol, temazepam |

| 857 | CONTROL | 12 | M | W | 48 | 16.6 | 6.54 | ASCVD | Natural | None |

| 1282 | CONTROL | 13 | F | W | 39 | 24.5 | 6.84 | Cardiac arrhythmia | Natural | None |

| 818 | CONTROL | 14 | F | W | 67 | 24.0 | 7.06 | Anaphylaxis | Accidental | None |

| Control Mean (SD): | 48.9 (12.1) | 17.8 (6.5) | 6.71 (0.25) |

Field evaluations were conducted by trained and experienced clinicians and consisted of structured interviews with family members of the deceased. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. After field interviews were completed, a committee of experienced research clinicians performed an independent diagnostic conference and assigned consensus DSM IV diagnoses (including depressive subtypes) for each subject on the basis of medical records and the results of structured interviews conducted with family members of the deceased. Eleven of the 14 depressed samples came from persons with the melancholic subtype.

Upon receipt, the brains were dissected coronally, flash-frozen and stored at −80°C. An approximately 5mm × 5mm gray matter cube from BA10 (spanning the cortical gray matter) was carved out from the frozen block using pre-chilled dental tools. This ensured a more homogenous sample, greatly diminishing harvesting bias (variable white matter/gray matter ratio) and reducing experimental noise in our dataset. Furthermore, this approach allowed us to preferentially detect expression changes in neuron- and glia-enriched tissue. The tissue piece was immediately placed in cold Trizol reagent, homogenized and used for RNA extraction.21

Design and Processing of RNA Microarrays

RNA concentration was determined with an Agilent BioAnalyzer 2100 system (Agilent, Palo Alto, California)21. The RNA integrity number (RIN) was >7 for all subjects. cDNA synthesis, amplification and labeling were performed using the manufacturer’s protocol (http://www.affymetrix.com/support/technical/technotes/human_exon_wt_target_technote.pdf). Briefly, the labeling started with a ribosomal RNA reduction step, in which 60–80% of the ribosomal RNAs are eliminated. cDNA is generated by a random priming method. The random primers incorporate a T7 promoter sequence which is subsequently used in an in vitro transcription to produce antisense cRNA fragments, where a modified dUTP is incorporated instead of dTTP. The modified dUTP is subsequently recognized by the enzymes Urasil-DNA glycosylase (UDG) and human apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1 (APE 1) which will cut the DNA, resulting in fragmentation of the cDNA. Each DNA fragment is end-labeled with biotin using terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) before being hybridized to the arrays.

In this study we used the Human Affymetrix Exon 1.0 ST arrays (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA); for this study we will report the analyses for the 60,000 core transcripts. Hybridization to the Human Exon 1.0 ST array, post-hybridization washes, staining, array image generation, segmentation and QC analysis were performed by the Vanderbilt Microarray Shared Resource (VMSR) using the manufacturer’s standard protocols.

Identifying differentially expressed genes

After a visual inspection of unsegmented microarray scans, standard image segmentation was performed and DAT files were generated. CEL files produced by the VMSR were imported into Expression Console software, version 1.1 (Affymetrix), and data normalized using the Robust Multi-Array Averaging (RMA) algorithm. Export of the data from the Expression console using the “Core” data filter collapsed exon-level data onto known transcripts, producing ~60,000 transcript-level data points for each subject. Data were analyzed in Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) in two steps. A Student’s group wise two-tailed t-test compared RMA intensities of MDD and controls samples. Then, signal intensity magnitude difference was calculated as a log2 based Average Log Ratios (ALR). ALR is calculated according to the following equation: ALR=mean(log2{D1}… log2{Dn}) − mean(log2{C1}… log2{Cn}), where D=depressed and C=control individual gene expression values. As gene expression differences of miniscule magnitude often may have statistical significance (but represent mostly artifacts), we used a conservative, previously established dual-criteria approach21–24 to identify the differentially expressed genes in our dataset: a gene was considered differentially expressed if it showed an |ALR|>0.585 (representing a 1.5 fold [50%] difference in either direction) and a group wise p<0.01 between MDD and control subjects.

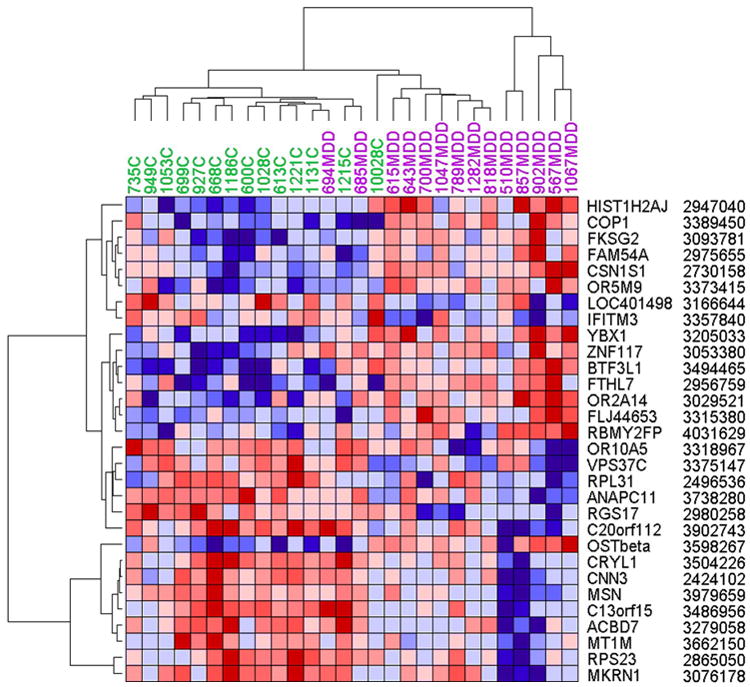

Clustering

Hierarchical clustering was performed to identify similarities in gene expression change (potentially co-regulated genes) and to assess the capacity of the disease gene “signature” to dichotomize the subject population into disease and control groups (i.e. does the disease gene signature adequately “diagnose” the disease). Differentially expressed genes (ALR>.0.585, p<0.01) were subjected to an unsupervised two-way clustering analysis based on Euclidian distance (RMA-normalized expression profile for individual genes × individually analyzed samples) using GenePattern25 as previously described21.

Correlation analysis

Bivariate correlations were determined using the Pearson Product-Moment correlation coefficient (SPSS version 16, SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). RMA-normalized ALR values were used as input data.

Gene set analysis

Gene set analysis was performed using Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) software as described previously.26 This method determines whether a priori defined set of genes shows statistically significant, concordant differences between two biological states or phenotypes. The Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) contains more than 3000 knowledge-based gene sets for use with GSEA, and the dataset is analyzed simultaneously for multiple gene sets.27 To simultaneously analyze for gene set enrichment and control for false discovery, we performed 1,000 permutations per analysis using the MDD versus control phenotypes 27. False discovery rate threshold in GSEA was measured by Q-value, a test that measures the proportion of false positives incurred when that particular test is called significant. Q-value was set at q≤0.05 28, identifying differentially expressed gene sets that had >95% probability to represent true, biological observations. Enrichment sets represent BioCarta-derived (http://www.biocarta.com/genes) gene sets (designated as “pathways”), corrected for multiple comparisons. The enrichment score (ES) represents the degree to which a specific set is represented at the extremes (high or low) of the entire list. The enrichment score corresponds to a weighted Kolmogorov Smirnov-like statistic.27 The statistical significance (nominal p-value) was calculated using permutation testing. The core members of high scoring gene sets that contribute to the ES are extracted by defining the subset of genes in the set that appear in the ranked list at or before the point where the running sum reaches its maximum deviation from zero. This is the subset of a gene set that accounts for the enrichment signal.27

Real-Time Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction

Ten genes, showing differential expression between MDD and CTR subjects, were selected for quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analysis. For each of the selected genes, cDNA was synthesized with the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems; Foster City, California). TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems) were performed on 50 ng cDNA/sample for 10 genes: histone cluster 1, H2aj (HIST1H2AJ), Y box binding protein 1 (YBX1), caspase-1 dominant-negative inhibitor pseudo-ICE (COP1), Zinc Finger Protein 117 (ZNF117), Casein Alpha S1 (CSN1S1), Calponin 3, acidic (CNN3), olfactory receptor, family 10, subfamily A, member 5 (OR10A5), vacuolar protein sorting 37 homolog C (S. cerevisiae) (VPS37C), Metallothionein 1M (MT1M), and Moesin (MSN). The results were then verified and normalized against endogenously glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDHS) which did not display a significant gene variation between MDD and CTR subjects. The qPCR reactions were performed by an ABI Prism 7000 SDS cycler (Applied Biosystems) with the ABI Prism 7000 SDS software. The software was run with the automatic baseline and threshold (Ct) detection options selected. The quantified qPCR data was exported to Microsoft Excel to organize MDD and CTR ΔCt, determine MDDΔCt - CTRΔCt (ΔΔCt).

Data Sharing

Complete microarray data will be made available by request upon publication.

RESULTS

The Affymetrix Human Exon 1.0 array allowed us to analyze 60,000 gene expression products. Samples from MDD and CTR subjects were obtained from Brodman’s area 10 in the prefrontal cortex. Our analysis revealed 30 transcripts which displayed significant expression differences between MDD and CTR samples, using a metric of |ALR| > .585 (50% change) and p ≤ 0.01. Of these genes, 14 genes (46.7%) were found to be in MDD samples compared to CTR samples with a mean ALR of 0.80 (1.7-fold increase; Table 2) and 16 genes (53.3%) were found to be under-expressed in MDD as compared to CTR samples with a mean ALR value of −0.70 (1.6-fold decrease; Table 2).

Table 2.

Genes with increased and decreased expression in BA10 of subjects with major depressive disorder

| A. Increased Expression: | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UniGene | Gene Name | Gene Symbol | Chromosome | ALR* | P** |

| Hs.406691 | Histone cluster 1, H2aj | HIST1H2AJ | 6p22-21.3 | 1.577 | <0.0001 |

| Hs.473583 | Y box binding protein 1 | YBX1 | 1p34 | 1.136 | 0.0014 |

| Hs.348365 | Caspase-1 dominant-negative inhibitor pseudo-ICE | COP1 | 11 | 0.996 | 0.0036 |

| Hs.534533 | Organic solute transporter beta | OSTbeta | 15q22.31 | 0.819 | 0.0015 |

| Hs.3155 | Casein alpha s1 | CSN1S1 | 4q21.1 | 0.778 | 0.0070 |

| Hs.651853 | Apoptosis inhibitor | FKSG2 | 8p11.2 | 0.741 | 0.0066 |

| Hs.567241 | Basic transcription factor 3, like 1 | BTF3L1 | 13q22 | 0.688 | 0.0066 |

| Hs.250693 | Zinc finger protein 117 | ZNF117 | 7q11.21 | 0.684 | 0.0005 |

| Hs.534547 | Olfactory receptor, family 2, subfamily A, member 14 | OR2A14 | 7q35 | 0.671 | <0.0001 |

| Hs.121536 | Family with sequence similarity 54, member A | FAM54A | 1q32.3 | 0.664 | 0.0065 |

| Hs.660426 | FLJ44653 protein | FLJ44653 | 10q26.3 | 0.653 | 0.0002 |

| Hs.684794 | RNA binding motif protein, Y-linked, family 2, member F pseudogene | RBMY2FP | Yq11.223 | 0.624 | 0.0085 |

| Hs.333125 | Ferritin, heavy polypeptide-like 7 | FTHL17 | Xp21 | 0.622 | 0.0004 |

| Hs.553749 | Olfactory receptor, family 5, subfamily M, member 9 | OR5M9 | 11q11 | 0.592 | 0.0007 |

| B. Decreased Expression: | |||||

| UniGene | Gene Name | Symbol | Chromosome | ALR* | P** |

| Hs.166313 | Regulator of g-protein signalling 17 | RGS17 | 6q25.3 | −0.924 | 0.0012 |

| Hs. 534456 | APC11 anaphase promoting complex subunit 11 | ANAPC11 | 17q25.3 | −0.912 | 0.0064 |

| Hs.516978 | Chromosome 20 EST | C20orf112 | 20q11.1-11.23 | −0.901 | 0.0095 |

| Hs.647370 | Metallothionein 1M | MT1M | 16q13 | −0.864 | 0.0104 |

| Hs.644598 | Acyl-coenzyme a binding domain containing 7 | ACBD7 | 10p13 | −0.804 | 0.0056 |

| Hs.646477 | interferon-induced transmembrane protein 3 | IFITM3 | 7p11.2 | −0.779 | 0.0049 |

| Hs.490347 | Makorin, ring zinc finger protein, 1 | MKRN1 | 7q34 | −0.690 | 0.0092 |

| Hs.507866 | Chromosome 13 open reading frame 15 | C13orf15 | 13q14.11 | −0.672 | 0.0097 |

| Hs.87752 | Moesin | MSN | Xq11.2-q12 | −0.686 | 0.0025 |

| Hs.469473 | Ribosomal protein L31 | RPL31 | 2q11.2 | −0.630 | 0.0087 |

| Hs.523715 | Vacuolar protein sorting 37 homolog C | VPS37C | 11q12.2 | −0.620 | 0.0084 |

| Hs.447478 | Olfactory receptor, family 10, subfamily A, member 5 | OR10A5 | 11p15.4 | −0.606 | 0.0059 |

| Hs.527193 | Ribosomal protein s23 | RPS23 | 5q14.2 | −0.605 | 0.0091 |

| Hs.483454 | Calponin 3, acidic | CNN3 | 1p22-p21 | −0.603 | 0.0039 |

| Hs.370703 | Crystallin, lambda 1 | CRYL1 | 13q12.11 | −0.589 | 0.0043 |

| Hs.522063 | RIKEN A930001M12 | LOC401498 | 9p21.1 | −0.588 | 0.0017 |

Mean ALR, depressed minus control

Groupwise p value

qPCR Findings

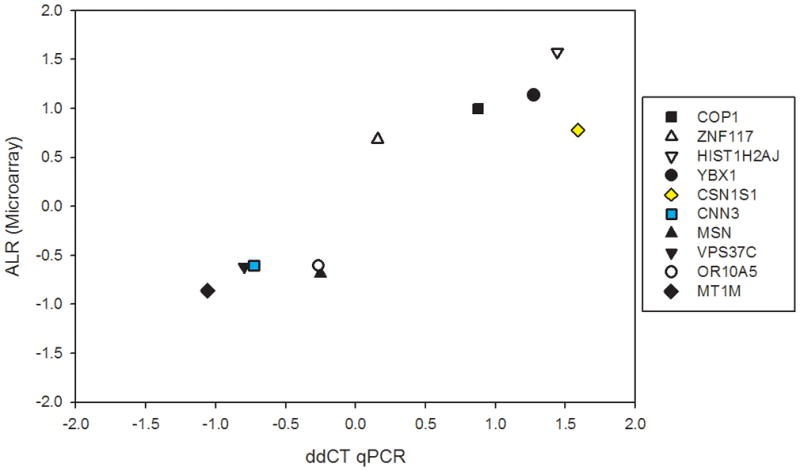

Ten genes were selected to validate our microarray findings. These transcripts were selected for validation due to their putative role in dysregulation of cytokine pathways in MDD as compared to CTR subjects. Five of the gene transcripts were over-expressed (HIST1H2AJ, YBX1, COP1, ZNF117, CSN1S1) and the other five were under-expressed (CNN3, OR10A5, VPS37C, MT1M, MSN) in the MDD samples. In addition, one over expressed cytokine, IL-9 was also included. For these 11 transcripts, the ΔΔCt qPCR findings were highly correlated (r=0.92; p< 0.001) with the microarray data between MDD and CTR subjects (Figure 2).

Figure 2. qPCR Analysis of selected cytokine-related mRNAs in MDD subjects and matched controls.

X axis denotes microarray-reported expression differences (ALR), while Y axis shows qPCR-obtained differential expression values (ΔΔCt) for 10 selected transcripts. Each symbol represents a different gene, denoted in the figure legend. Note that all the observations occupy quadrants 2–3 (and no observations are located in quadrants 1 and 4), showing that all microarray-qPCR results were concordant in directionality of change. The ALR-ΔΔCt results were highly correlated (r=0.92; p < 0.001).

The effects of age, sex, pH, and PMI on expression levels

Correlations between pH, PMI, age and differentially-expressed genes were performed. A significant correlation was found only between pH and the expression level of ZFN117 (r=0.411, df=28, p=0.03); after correction for multiple comparisons this was no longer significant. All differentially-expressed genes were compared by sex using the Students t-test; all comparisons were not significant.

Correlational analysis

Associations between the selected genes differentially-expressed in MDD were tested using the Pearson Product Moment correlation coefficient. Genes for this analysis were selected based on their effects on transcriptional regulation (HIST1H2AJ, ZNF117, MKRN1, RGS17), apoptosis (YBX1, COP1, FKSG2), structural integrity (MSN), or modulation of oxidative stress (MT1M). Most genes showed significant direct or inverse correlations with other differentially-expressed genes. There were particularly strong correlations (r>0.600) found between MT1M, MKRN1, and MSN, all with reduced expression. In addition, the anti-apoptotic factors YBX1, COP1, and FKSG2 were significantly correlated with each other, and with the histone protein HIST1H2AJ.

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

Of the 8 pathways which demonstrated significant enrichment (Table 3) the most robust finding revealed an up regulation of transcripts pertaining to the cytokine pathway in the MDD group, with a nominal p value=0.0062 and FDR q value=0.03 (Table 7). Of the 18 constituents of this pathway, 13 were significant in the core enrichment of the dataset, including interleukin 1α (IL1α), IL2, IL3, IL5, IL8, IL9, IL10, IL12A, IL13, IL15, IL18, interferon gamma (IFNγ), and lymphotoxin alpha (LTA; TNF super family, member 1; TNFβ).

Table 3.

Gene set enrichment analysis:

| A. BioCarta pathways showing gene enrichment. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BioCarta pathway name | Size (genes) | Enrichment Score | p-val | Change direction |

| VEGFPATHWAY | 25 | 0.657942 | 0.008163 | Decreased |

| CDMACPATHWAY | 15 | 0.699933 | 0.02268 | Decreased |

| INTEGRINPATHWAY | 33 | 0.549887 | 0.03527 | Decreased |

| ECMPATHWAY | 20 | 0.629207 | 0.038855 | Decreased |

| PROTEASOMEPATHWAY | 16 | 0.760643 | 0.041929 | Decreased |

| ATMPATHWAY | 18 | 0.529419 | 0.04918 | Decreased |

| MCALPAINPATHWAY | 22 | 0.62423 | 0.049587 | Decreased |

| CYTOKINEPATHWAY | 18 | −0.79414 | 0.006211 | Increased |

| B. GSEA cytokine pathway constituents (listed by Running ES rank). | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Symbol | Gene Name | Rank Metric Scorea | Running ESb | Core Enrichment |

| IL18 | Interleukin 18 (interferon-gamma-inducing factor) | −0.031 | −0.7628 | Yes |

| IL5 | Interleukin 5 (colony-stimulating factor, eosinophil) | −0.061 | −0.7613 | Yes |

| LTA | Lymphotoxin alpha (TNF superfamily, member 1; TNFβ) | −0.075 | −0.7345 | Yes |

| IFNG | Interferon, gamma | −0.098 | −0.7007 | Yes |

| IL15 | Interleukin 15 | −0.106 | −0.6492 | Yes |

| IL12A | Interleukin 12a (natural killer cell stimulatory factor 1, cytotoxic lymphocyte maturation factor 1, p35) | −0.113 | −0.5942 | Yes |

| IL1A | Interleukin 1, alpha | −0.114 | −0.5334 | Yes |

| IL10 | Interleukin 10 | −0.131 | −0.4741 | Yes |

| IL8 | Interleukin 8 | −0.137 | −0.4033 | Yes |

| IL13 | Interleukin 13 | −0.167 | −0.3277 | Yes |

| IL2 | Interleukin 2 | −0.208 | −0.2289 | Yes |

| IL9 | Interleukin 9 | −0.228 | −0.1106 | Yes |

| IL3 | Interleukin 3 (colony-stimulating factor, multiple) | −0.245 | 0.0182 | Yes |

| IL6 | Interleukin 6 | 0.074 | −0.6347 | No |

| IL4 | Interleukin 4 | 0.036 | −0.6943 | No |

| IL12B | Interleukin 12b (natural killer cell stimulatory | 0.016 | −0.7183 | No |

| factor 2, cytotoxic lymphocyte maturation factor 2, p40) | ||||

| IL16 | Interleukin 16 (lymphocyte chemoattractant factor) | 0.007 | −0.7297 | No |

| TNF | Tumor necrosis factor (TNF super family, member 2 [TNFα]) | −0.011 | −0.7515 | No |

Rank metric: GSEA uses the signal-to-noise metric to rank the genes (for details, see “Metrics for Ranking Genes” at http://www.broadinstitute.org/gsea/doc/GSEAUserGuideFrame.html?Run_GSEA_Page). The larger the signal-to-noise ratio, the larger the differences of the means (relative to the standard deviations). A high signal-to-noise metric indicates greater separation between phenotypes.

Running ES: Running enrichment score, which reflects the degree to which a gene set is overrepresented at the top or bottom of a ranked list of genes (for details, see “GSEA Statistics” at http://www.broadinstitute.org/gsea/doc/GSEAUserGuideFrame.html?Run_GSEA_Page).

DISCUSSION

The microarray mRNA expression analysis in this study from 14 matched depressed and matched control brains tissue samples from BA10 suggest that there may be increased inflammatory or other pro-apoptotic stress in the MDD sample group. For example, there was significant up regulation of Caspase-1 dominant-negative inhibitor, pseudo-ICE (COP1). Caspases are cysteine proteases that are involved in cell death cycles via apoptosis or inflammation. COP1 has significant homology with the caspase recruitment domain (CARD) of Caspase-1 and it acts as an inhibitor of both Caspase-1 and -4,29, both of which are up regulated in face of inflammatory stress.30 Increased expression of COP1 is protective of Caspase-mediated cell death.31 Similarly, Both FKSG2, a putative apoptosis inhibitor protein, and Y-box binding protein 1 (YBX1) were significantly upregulated in the MDD sample. Relatively little is known about FKSG2, although it is known to be up regulated by cysteinyl leukotrienes, which are mediators of tissue inflammation.32 YBX1 is a member of the cold shock domain super family of proteins, a highly evolutionarily conserved transcription factor.33 YBX1 is involved in a variety of intracellular functions including transcriptional regulation (either activation or repression), DNA repair, and response to stress signals.33 One role of YBX1 is to bind to free mRNA, which prevents translation (“mRNA masking”) and degradation.33 YBX1 is up regulated in face of a variety of stressors, including hyperthermia, UV radiation, and viral infection, and it is involved in nuclear viral replication. Upregulation of the expression of specific anti-apoptotic proteins suggests the possibility of apoptotic stress in this region, which has been hypothesized as a causal factor in depression.34;35 In fact, a variety of studies have implicated impaired neuroplasticity, reduction in regional brain volumes, and decreased neuronal and glial cell body numbers in depressed patients relative to controls, all of which implicate apoptosis.35

Traditional gene expression analysis has tended to focus on single genes that are differentially expressed between two groups. However, although this is a conservative and highly rigorous approach, it may miss subtle but important dysregulation of genes distributed across networks of related pathways.27 GSEA was developed to analyze gene set data, and has been successfully applied to discover distributed networks of genes in a number of conditions, such as b-cell lymphoma36 and prostate cancer.37 The results of gene set analysis in the present study amplify the evidence of upregulation of the expression of genes involved in response to stress and inflammation. GSEA tests a priori gene groupings based on underlying biological similarities. In the present analysis, only the pre-set “cytokine” grouping showed significant up-regulation (Table 3). Although the absolute fold increase for each was modest, the set analysis suggests dysregulation of proinflammatory mechanisms. A number of cytokines were up regulated, including IL1α, IL2, IL3, IL5, IL8, IL9, IL10, IL12A, IL13, IL15, IL18 (also known as interferon γ [IFNγ] inducing factor), as well as IFNγ itself and lymphotoxin alpha (TNFβ), most of which are pro-inflammatory (Table 7). An exception is IL10, which is an anti-inflammatory cytokine that inhibits synthesis of IL2, IL3, and IFNγ, which may be up regulated in response to the increase in these cytokines. Together with the up regulated expression of COP1, YBX1, and FKSG2, these results suggest a local environment experiencing significant inflammatory stress.

Evidence for inflammation as a basis for depression is supported by prior research suggesting a connection between depression and proinflammatory cytokines and related proteins.38;39 It has been postulated that certain proinflammatory cytokines act on the central nervous system causing so-called “sickness behavior” in both humans and animals. Symptoms that are common during infection share features with depression, including down mood, loss of interest in usual activities (anhedonia), anorexia, sleep disturbance, and decreased locomotor activity38. In fact, therapeutically administered interferons such as IFNα for hepatitis C can produce a syndrome that is indistinguishable from depression40. Moreover, this can be attenuated or prevented by treatment with antidepressant medication41;42. Several antidepressants have been shown to suppress proinflammatory cytokine production and to release endogenous anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL10.43–47

A variety of studies have found elevated peripheral cytokines and other proinflammatory mediators in depression, including C-reactive protein, IL-1, IL-6, TNFα, and IFNγ in MDD (for reviews see Raison et al.38, Dantzer48, Garcia-Bueno et al.,49 and Miller et al.50). To our knowledge, however, the present study is the first demonstration of elevated levels of cytokines in brain in MDD, which suggests that the elevations of cytokines demonstrated in previous studies are actually reflected in the brain itself. This strongly supports inflammation as a mediator of depression in at least some patients with depression.

Although immune activation is associated with peripheral immune cells such as neutrophils, natural killer cells, and macrophages, it is now clear that locally resident cell types including microglia, astrocytes, and neurons mount innate immune responses in the central nervous system.51 As an example, acute immune activation of microglia, such as that seen with the gram-negative endotoxin lipopolysaccharide, can result in a robust release of TNF-α, IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-6.52 Similarly, stress may also activate similar immune responses in brain without the presence of typical pathogen associated molecules.53 However, both chronic immune activation52 and chronic stress54 leads to a progressive reduction in the release of these molecules and an increase in anti-inflammatory mediators such as IL-10.55 Chronic immune activation may account, then, for the apparent discrepancy between the results we have shown in brain and the prior observation in peripheral samples, in which increased IL-6 and TNFα have been most consistently shown.38;50

The actual causal pathway connecting proinflammatory cytokines and depression remains obscure, but there are some mechanisms that have been implicated. For example, inflammatory cytokines including IL1β, TNFα56 IL3 and IL557 activate p38 mitogen activated protein kinase (p38 MAPK), which has been shown to induce catalytic activation of the serotonin transporter, which increases uptake of serotonin, decreasing synaptic availability56;58. Both IL1β and TNFα increase serotonin uptake in both a rat embryonic raphe cell line and synaptosomes isolated from mouse brain.56;58 In addition, proinflammatory cytokines, including IFNγ, activate the enzyme indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) leading to the synthesis of kynurenine from tryptophan, the precursor to serotonin. This shift to kynurenine synthesis leads to a relative depletion of serotonin which could induce depressive symptoms in vulnerable individuals.59 The kynurenine pathway leads to the synthesis of several neuroactive products, including the neuroprotective intermediaries kynurenic acid and picolinic acid and the NMDA receptor agonist neurotoxin quinolinic acid.60 Inflammatory cytokines also have significant effects on dopamine and associated reward related behavior. For example, in rats, IL2 (which was elevated in the tissue samples from depressed patients in the present study) has been shown to decrease dopamine efflux in nucleus accumbens and to inhibit self-stimulation via an electrode in the median forebrain bundle, a model of rewarding behavior.

While the present study implicates local inflammatory and apoptotic stress in BA10, the mechanisms mediating these effects are unclear. One clue may be found in one of the genes found to be reduced relative to controls in the present sample, metallothionein 1M (MT1M). Metallothioneins (MTs) represent a family of cysteine-rich proteins that bind heavy metals through the cysteine thiol group.61;62 In particular, MT1M is involved in zinc homeostasis via zinc-thiol binding. Under normal conditions, zinc concentrations are tightly regulated by MT1M and related zinc binding (thiolate) proteins.61;62 MTs also directly regulate oxidative stress by cysteine capture of free radicals.63 Under conditions of oxidative stress, MTs scavenge free radicals, releasing zinc into the cytoplasm. Reduced availability of MT1M would be expected to enhance oxidative stress directly by altered regulation of superoxide radicals, and indirectly by effects on zinc metabolism. Low MT1M, then, would create a state of vulnerability to oxidative stress by creating a redox imbalance by a failure to maintain an appropriate reducing environment. In fact, prior research indicates that MTs exert anti-apoptotic functions via a variety of mechanisms, including inflammatory and oxidative stress.61 Notably, a recent study has shown that exogenous administration of MT markedly attenuated microglia activation and quinolinic acid expression induced by IFNγ.60 Clearly, this novel finding needs further investigation to determine what, if any, role MTs may play in depression vulnerability.

The results of this study are at variance with previous post-mortem brain microarray analyses in MDD,2;3;5;8;64 which could be related to a variety of factors, including differences in microarray platforms, brain region, and clinical phenotype. BA10 is involved in reward-related cognitive processing12 and is activated in response to highly reinforcing stimuli.13;14 Cellular dysfunction in BA10 may, then, account for some of the deficits in response to reward that are found in depression.15;16 Only one previous study investigated BA10, and found a dissimilar set of differentially-expressed genes.17 A variety of factors may have contributed to these differences. For example, in that study, nine of 11 depressed subjects were on psychotropics, whereas the current set were free of known psychotropic medications. Another possible source of variance with this and other microarray studies may be the clinical phenotype chosen for our study. Most of the patient samples in the current study came from persons with the clinical phenotype of melancholic MDD, which shows particularly severe deficits of reward responding;65 the proportion of samples in previous studies from the melancholic subtype is unknown. Melancholic MDD is a distinct clinical phenotype, which tends to be characterized by marked psychomotor disturbances, sleep and appetite changes, and reduced responses to hedonic stimuli65;66. Moreover, the melancholic subtype of depression may be more likely to show dysregulation of peripheral markers of immune function53. For example, one study showed that, whereas non-melancholic depressed patients exhibited increased leukocytes (particularly natural killer cells) but no differences in cytokines, melancholics had elevated IL2, IL10, and IFNγ, which is consistent with the results of the gene set analysis in the present study67. Whether melancholia is specifically characterized by local apoptotic and inflammatory stress in brain should be further investigated in future studies.

There are significant limitations to the current analysis. We have shown altered expression of specific genes and gene sets; however, this may or may not be reflected in actual gene products or downstream functions. Further, the results were limited to a single brain area; whether these differences are found in other brain regions is unknown. We also oversampled the melancholic subtype of MDD; the accuracy of this subtype distinction depends on the precision of the diagnosis made via interview with the next-of-kin, which may or may not reflect the actual diagnosis in life.

In summary, the present study suggests that, in BA10, depressed persons show evidence of increased inflammatory and apoptotic stress, including elevations in specific cytokines as well as anti-apoptotic proteins. Although the causal mediators of these abnormalities are not known, oxidative stress is implicated. Clearly further research is needed to validate these findings and to further investigate causal mechanisms.

Figure 1. Hierarchical clustering of differentially expressed genes.

Normalized log2 intensities were clustered by GenePattern in two dimensions (horizontal: genes; vertical: samples [purple=MDD, green=controls]) on the basis of Euclidian distance. Each colored pixel represents a single gene expression value in one subject. The color intensity is proportional to its relative expression level (blue: under expressed; red: over expressed). Note that the statistical segregation of depressed and control subjects are almost complete, with an overlap of only two controls. Labels on the right denote gene symbols and probe identifiers. For more data, see Table 2.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Dr. Phil Ebert (currently with Eli Lilly and Co) for help with data analysis and Dr. Christine Konradi for advising the microarray experiments. The project described was supported by grant Award Numbers MH073630 (RCS), MH079299 (KM), MH070786 (KM), and MH084053 (DAL) from the National Institute of Mental Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIMH or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURES: None.

Contributor Information

RC Shelton, Email: richard.shelton@vanderbilt.edu, Department of Psychiatry, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, 1500 21st Avenue, South, Suite 2200, Nashville, TN 37212 USA. Phone: 1-615-343-9669. Fax: 1-615-322-1578

J Claiborne, Department of Psychiatry, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, TN 37212 USA

M Sidoryk-Wegrzynowicz, Department of Pediatrics, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, TN 37212 USA

R Reddy, Department of Psychiatry, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, TN 37212 USA

M Aschner, Department of Pediatrics, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, TN 37212 USA.

DA Lewis, Departments of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 15261

K Mirnics, Department of Psychiatry and the John F. Kennedy Center for Human Development, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN 37232

Reference List

- 1.Drevets WC, Price JL, Furey ML. Brain structural and functional abnormalities in mood disorders: implications for neurocircuitry models of depression. Brain Struct Funct. 2008;213:93–118. doi: 10.1007/s00429-008-0189-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sibille E, Arango V, Galfalvy HC, Pavlidis P, Erraji-Benchekroun L, Ellis SP, et al. Gene expression profiling of depression and suicide in human prefrontal cortex. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:351–361. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evans SJ, Choudary PV, Neal CR, Li JZ, Vawter MP, Tomita H, et al. Dysregulation of the fibroblast growth factor system in major depression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:15506–15511. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406788101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sequeira A, Gwadry FG, French-Mullen JM, Canetti L, Gingras Y, Casero RA, Jr, et al. Implication of SSAT by gene expression and genetic variation in suicide and major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:35–48. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klempan TA, Sequeira A, Canetti L, Lalovic A, Ernst C, French-Mullen J, et al. Altered expression of genes involved in ATP biosynthesis and GABAergic neurotransmission in the ventral prefrontal cortex of suicides with and without major depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;14:175–189. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choudary PV, Molnar M, Evans SJ, Tomita H, Li JZ, Vawter MP, et al. Altered cortical glutamatergic and GABAergic signal transmission with glial involvement in depression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15653–15658. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507901102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aston C, Jiang L, Sokolov BP. Transcriptional profiling reveals evidence for signaling and oligodendroglial abnormalities in the temporal cortex from patients with major depressive disorder. Molecular Psychiatry. 2005;10:309–322. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kang HJ, Adams DH, Simen A, Simen BB, Rajkowska G, Stockmeier CA, et al. Gene expression profiling in postmortem prefrontal cortex of major depressive disorder. J Neurosci. 2007;27:13329–13340. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4083-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tochigi M, Iwamoto K, Bundo M, Sasaki T, Kato N, Kato T. Gene expression profiling of major depression and suicide in the prefrontal cortex of postmortem brains. Neurosci Res. 2008;60:184–191. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewis DA. The human brain revisited: opportunities and challenges in postmortem studies of psychiatric disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;26:143–154. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00393-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mirnics K, Levitt P, Lewis DA. DNA microarray analysis of postmortem brain tissue. International Review of Neurobiology. 2004;60:153–181. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(04)60006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rogers RD, Owen AM, Middleton HC, Williams EJ, Pickard JD, Sahakian BJ, et al. Choosing between small, likely rewards and large, unlikely rewards activates inferior and orbital prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci. 1999;19:9029–9038. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-20-09029.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kufahl PR, Li Z, Risinger RC, Rainey CJ, Wu G, Bloom AS, et al. Neural responses to acute cocaine administration in the human brain detected by fMRI. NeuroImage. 2005;28:904–914. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Devous MD, Trivedi MH, Rush AJ. Regional cerebral blood flow response to oral amphetamine challenge in healthy volunteers. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2001;42:535–542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pizzagalli DA, Iosifescu D, Hallett LA, Ratner KG, Fava M. Reduced hedonic capacity in major depressive disorder: Evidence from a probabilistic reward task. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;43:76–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pizzagalli DA, Jahn AL, O’Shea JP. Toward an objective characterization of an anhedonic phenotype: a signal-detection approach. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:319–327. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tochigi M, Iwamoto K, Bundo M, Sasaki T, Kato N, Kato T. Gene expression profiling of major depression and suicide in the prefrontal cortex of postmortem brains. Neuroscience Research. 2008;60:184–191. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaughran F, Payne J, Sedgwick PM, Cotter D, Berry M. Hippocampal FGF-2 and FGFR1 mRNA expression in major depression, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Brain Res Bull. 2006;70:221–227. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carroll BJ, Cassidy F, Naftolowitz D, Tatham NE, Wilson WH, Iranmanesh A, et al. Pathophysiology of hypercortisolism in depression. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, Supplementum (433):90–103, 2007. 2007:90–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.00967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pintor L, Torres X, Navarro V, Martinez de Osaba MA, Matrai S, Gasto C. Corticotropin-releasing factor test in melancholic patients in depressed state versus recovery: a comparative study. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 2007;31:1027–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garbett K, Ebert PJ, Mitchell A, Lintas C, Manzi B, Mirnics K, et al. Immune transcriptome alterations in the temporal cortex of subjects with autism. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;30:303–311. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hashimoto T, Arion D, Unger T, Maldonado-Aviles JG, Morris HM, Volk DW, et al. Alterations in GABA-related transcriptome in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of subjects with schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;13:147–161. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lazarov O, Robinson J, Tang YP, Hairston IS, Korade-Mirnics Z, Lee VM, et al. Environmental enrichment reduces Abeta levels and amyloid deposition in transgenic mice. Cell. 2005;120:701–713. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mirnics K, Pevsner J. Progress in the use of microarray technology to study the neurobiology of disease. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:434–439. doi: 10.1038/nn1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reich M, Liefeld T, Gould J, Lerner J, Tamayo P, Mesirov JP. GenePattern 2.0. Nat Genet. 2006;38:500–501. doi: 10.1038/ng0506-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campbell DB, D’Oronzio R, Garbett K, Ebert PJ, Mirnics K, Levitt P, et al. Disruption of cerebral cortex MET signaling in autism spectrum disorder. Ann Neurol. 2007;62:243–250. doi: 10.1002/ana.21180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, et al. From the Cover: Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Storey JD, Tibshirani R. Statistical significance for genomewide studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9440–9445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1530509100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang X, Narayanan M, Bruey JM, Rigamonti D, Cattaneo E, Reed JC, et al. Protective role of Cop in Rip2/caspase-1/caspase-4-mediated HeLa cell death. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1762:742–754. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2006.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martinon F, Tschopp J. Inflammatory caspases and inflammasomes: master switches of inflammation. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:10–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang X, Wang H, Figueroa BE, Zhang WH, Huo C, Guan Y, et al. Dysregulation of receptor interacting protein-2 and caspase recruitment domain only protein mediates aberrant caspase-1 activation in Huntington’s disease. J Neurosci. 2005;25:11645–11654. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4181-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uzonyi B, Lotzer K, Jahn S, Kramer C, Hildner M, Bretschneider E, et al. Cysteinyl leukotriene 2 receptor and protease-activated receptor 1 activate strongly correlated early genes in human endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:6326–6331. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601223103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kohno K, Izumi H, Uchiumi T, Ashizuka M, Kuwano M. The pleiotropic functions of the Y-box-binding protein, YB-1. Bioessays. 2003;25:691–698. doi: 10.1002/bies.10300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McKernan DP, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. “Killing the Blues”: A role for cellular suicide (apoptosis) in depression and the antidepressant response? Progress in Neurobiology. 2009;88:246–263. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dwivedi Y. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor: role in depression and suicide. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2009;5:433–49. doi: 10.2147/ndt.s5700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Monti S, Savage KJ, Kutok JL, Feuerhake F, Kurtin P, Mihm M, et al. Molecular profiling of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma identifies robust subtypes including one characterized by host inflammatory response. Blood. 2005;105:1851–1861. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Majumder PK, Febbo PG, Bikoff R, Berger R, Xue Q, McMahon LM, et al. mTOR inhibition reverses Akt-dependent prostate intraepithelial neoplasia through regulation of apoptotic and HIF-1-dependent pathways. Nat Med. 2004;10:594–601. doi: 10.1038/nm1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raison CL, Capuron L, Miller AH. Cytokines sing the blues: inflammation and the pathogenesis of depression. Trends Immunol. 2006;27:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maes M. The cytokine hypothesis of depression: inflammation, oxidative & nitrosative stress (IO&NS) and leaky gut as new targets for adjunctive treatments in depression. Minireview. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2008;29:287–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Capuron L, Miller AH. Cytokines and psychopathology: lessons from interferon-alpha. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:819–824. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Capuron L, Gumnick JF, Musselman DL, Lawson DH, Reemsnyder A, Nemeroff CB, et al. Neurobehavioral effects of interferon-alpha in cancer patients: phenomenology and paroxetine responsiveness of symptom dimensions. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;26:643–652. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00407-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raison CL, Woolwine BJ, Demetrashvili MF, Borisov AS, Weinreib R, Staab JP, et al. Paroxetine for prevention of depressive symptoms induced by interferon-alpha and ribavirin for hepatitis C. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:1163–1174. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maes M, Song C, Lin AH, Bonaccorso S, Kenis G, De Jongh R, et al. Negative immunoregulatory effects of antidepressants: inhibition of interferon-gamma and stimulation of interleukin-10 secretion. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;20:370–379. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leonard BE. The immune system, depression and the action of antidepressants. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2001;25:767–780. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(01)00155-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kubera M, Lin AH, Kenis G, Bosmans E, van Bockstaele D, Maes M. Anti-Inflammatory effects of antidepressants through suppression of the interferon-gamma/interleukin-10 production ratio. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;21:199–206. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200104000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kenis G, Maes M. Effects of antidepressants on the production of cytokines. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002;5:401–412. doi: 10.1017/S1461145702003164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.O’Brien SM, Scott LV, Dinan TG. Cytokines: abnormalities in major depression and implications for pharmacological treatment. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2004;19:397–403. doi: 10.1002/hup.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dantzer R. Cytokine, sickness behavior, and depression. Neurol Clin. 2006;24:441–460. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Garcia-Bueno B, Caso JR, Leza JC. Stress as a neuroinflammatory condition in brain: damaging and protective mechanisms. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32:1136–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miller AH, Maletic V, Raison CL. Inflammation and Its Discontents: The Role of Cytokines in the Pathophysiology of Major Depression. Biological Psychiatry. 2009;65:732–741. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Griffiths M, Neal JW, Gasque P. Innate Immunity and Protective Neuroinflammation: New Emphasis on the Role of Neuroimmune Regulatory Proteins. In: Giacinto Bagetta MTCa., editor. International Review of Neurobiology Neuroinflammation in Neuronal Death and Repair. Vol. 82. Academic Press; 2007. pp. 29–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ekdahl CT, Kokaia Z, Lindvall O. Brain inflammation and adult neurogenesis: The dual role of microglia. Neuroscience. 2009;158:1021–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hayley S, Poulter MO, Merali Z, Anisman H. The pathogenesis of clinical depression: Stressor- and cytokine-induced alterations of neuroplasticity. Neuroscience. 2005;135:659–678. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bartolomucci A, Palanza P, Parmigiani S, Pederzani T, Merlot E, Neveu PJ, et al. Chronic psychosocial stress down-regulates central cytokines mRNA. Brain Research Bulletin. 2003;62:173–178. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ekdahl CT, Kokaia Z, Lindvall O. Brain inflammation and adult neurogenesis: The dual role of microglia. Neuroscience. 2009;158:1021–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhu CB, Carneiro AM, Dostmann WR, Hewlett WA, Blakely RD. p38 MAPK activation elevates serotonin transport activity via a trafficking-independent, protein phosphatase 2A-dependent process. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:15649–15658. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410858200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ip WK, Wong CK, Wang CB, Tian YP, Lam CW. Interleukin-3, -5, and granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor induce adhesion and chemotaxis of human eosinophils via p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and nuclear factor kappaB. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2005;27:371–393. doi: 10.1080/08923970500240925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhu CB, Blakely RD, Hewlett WA. The proinflammatory cytokines interleukin-1beta and tumor necrosis factor-alpha activate serotonin transporters. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2121–2131. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Delgado PL, Charney DS, Price LH, Aghajanian GK, Landis H, Heninger GR. Serotonin function and the mechanism of antidepressant action. Reversal of antidepressant-induced remission by rapid depletion of plasma tryptophan. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:411–418. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810170011002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chung RS, Leung YK, Butler CW, Chen Y, Eaton ED, Pankhurst MW, et al. Metallothionein treatment attenuates microglial activation and expression of neurotoxic quinolinic acid following traumatic brain injury. Neurotox Res. 2009;15:381–389. doi: 10.1007/s12640-009-9044-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Formigari A, Irato P, Santon A. Zinc, antioxidant systems and metallothionein in metal mediated-apoptosis: biochemical and cytochemical aspects. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol. 2007;146:443–459. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Krezel A, Hao Q, Maret W. The zinc/thiolate redox biochemistry of metallothionein and the control of zinc ion fluctuations in cell signaling. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2007;463:188–200. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kumari MVR, Hiramatsu M, Ebadi M. Free radical scavenging actions of metallothionein isoforms I and II. Free Radical Research. 1998;29:93–101. doi: 10.1080/10715769800300111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sequeira A, Klempan T, Canetti L, ffrench-Mullen J, Benkelfat C, Rouleau GA, et al. Patterns of gene expression in the limbic system of suicides with and without major depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;12:640–655. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Leventhal AM, Rehm LP. The empirical status of melancholia: implications for psychology. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005;25:25–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Parker G, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Austin MP, Mitchell P, Wilhelm K, Hickie I, et al. Subtyping depression, I. Is psychomotor disturbance necessary and sufficient to the definition of melancholia? Psychol Med. 1995;25:815–823. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700035066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rothermundt M, Arolt V, Fenker J, Gutbrodt H, Peters M, Kirchner H. Different immune patterns in melancholic and non-melancholic major depression. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2001;251:90–97. doi: 10.1007/s004060170058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]