Abstract

Objective

Several Studies claim that psychophysical stress and depression contribute significantly to cardiovascular disease (CVD) development. The aim of our research is to discover and analyse a possible relationship between two psychosocial disorders (Depression and Perceived Mental Stress) and traditional cardiovascular risk markers.

Methods

We selected 106 subjects (M:58, F:48), mean age 79,5 ± 3,8 years old, from The Massa Lombarda Project, an epidemiological study including 7000 north Italian adult subjects. We carried out anamnesis, clinical and blood tests. Then we administered the Perceived Stress Questionnaire (PSQ range-score 0-1) and the Self Rating Depression Scale (SRDS range score 50-70 Z), as validated instruments for depression and stress evaluation, which focus on the individual's subjective perception and emotional response. Statistical descriptive and inferential analysis of data collected were performed.

Results

The Multiple linear regression analysis showed a negative correlation between PSQ Index score and Uric Acid, LDL-C, BMI, Systolic and Diastolic Blood Pressure values, a positive and statistically significant correlation between PSQ Index score and Triglycerides(P<0.05). We found an inverse relationship between Zung SRDS score and LDL-C, Uric Acid, Glucose, Waist Circumference values, this correlation was significant only for Uric Acid (P<0.01); besides a positive and significant correlation between Zung SRDS and Triglycerides (P<0.05) was observed.

Conclusion

We suppose that psycho-emotional stress and depression disorder, often diagnosed in elderly people, may influence different metabolic parameters (triglycerides, Uric Acid, BMI) that are involved in the complex process of Metabolic Syndrome.

Keywords: depression, mental stress, metabolic syndrome, uric acid, triglycerides

Introduction

Recent epidemiological studies suggest that psychosocial factors contribute significantly to the pathogenesis of Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) [Rozanski, Blumenthal & Kaplan, 1999; Strodl, Kenardy & Aroney, 2003; Rosengren et al., 2004]. Psychosocial factors which promote atherosclerosis and adverse cardiac events can be divided into two general categories: emotional factors and chronic stressors. Emotional factors include affective disorders such as Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) and anxiety as well as hostility and anger. Chronic stressors include low social support, low socioeconomical status, stress and caregiver strain [Rozanski, Blumenthal, Davidson, Saab & Kubzansky, 2005]. Research in this area has evaluated the effects of depression in both initially healthy individuals and in patients with known CVD. Depression plays a role in promoting cardiovascular events in both cohorts with various pathophysiological mechanisms. First of all, depression can mediate its effects on cardiovascular risk through lifestyle. Behavioural changes, like worse adherence to prescribed medication and other life style modifications, can result in a higher risk of cardiovascular events in aging population [Van der Kooy et al., 2007; Keyes, 2004]. However, there is a rich literature on psychosocial factors as independent predictors of CVD and it has been proved that these effects could be mediated by Metabolic Syndrome (MS) as a function of stress-related consequences [Frisman & Kristenson, 2009]. MS is a common disorder, characterised by visceral obesity, impaired glucose metabolism, raised blood pressure, atherogenic dyslipidemia, and the existence of a proinflammatory and prothrombotic state. MS is associated with a significantly increased risk of cardiovascular events and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) onset. MS is defined in various ways, but the latest diagnostic criteria proposed by the International Diabetes Federation are: central obesity (defined as a waist circumference >94 cm in men and >80 cm in women), plus at least two of the followings: fasting glucose serum level higher than 100 mg/dL, blood pressure values higher than 130/85 mmHg, fasting triglycerides serum level higher than 150 mg/dL, and HDL-c level lower than 40 mg/dL in men and 50 mg/dL in women [Alberti, Zimmet, Shaw & IDF Epidemiology Task Force Consensus Group, 2005]. Hypercortisolemia, which characterises depressive syndrome, in association with blunted Growth and Sex Hormones, promotes central obesity and an increase of peripheral and portal fatty acids; these metabolic changes also contribute to more insulin resistance and T2DM onset [Weber-Hamann, Hentschel & Kniest, 2002]. Moreover, recent findings indicate an increase oxidative activity in women affected from MDD [Kodydková et al., 2009], and patients with MDD seems to have a reduced total antioxidant capacity, compared to a control group [Sarandol et al, 2007]. Overproduction of reactive oxygen species is also associated to MS and it represents a well established cardiovascular risk factor. Serum Uric Acid (SUA), a molecule which plays an important and complex role in oxidative and anti-oxidative processes, is more elevated in MS, and a positive correlation exists between SUA and CVD, especially in high risk patients [Tsouli, Liberopoulos, Mikhailidis, Athyros & Elisaf, 2006]. In fact, certain pathophysiologic and metabolic features seem to co-exist in MS and MDD [McIntyre et al., 2009]. Also chronic stress appears to exert direct pathophysiological effects on CVD, including elevation of arterial blood pressure and neurohumoral arousal [Dimsdale, 2008]. The risk associated with psychosocial factors may actually be greater than statistical evidence suggests for two reasons. First, behavioural and metabolic risk factors tend to aggregate disproportionately among individuals, especially in the elderly, with psychosocial stress. However, this potentially powerful effect is reduced because of the statistical convention to adjust psychosocial risk ratios for behavioural and metabolic risk factors. Second, because measures of psychosocial stress may be imprecise and the relationship between psychosocial stress and CVD outcomes may be underestimated [Rozanski et al., 1999; Rosengren et al., 2004].

Several studies have explored an association between lipoproteins and depression, but findings are contradictory in general population and young people [van Reedt Dortland et al., 2009]. On the other hand, among elderly people, a significant correlation was found between TC, LDL-c and MDD [Brown et al., 1994].

In consideration of the fact that affective disorder are very common among elderly people [Lebowitz et al., 1997] and the incidence of metabolic impairment increases with aging [Reynolds & He, 2005], we undertook a study on a group of elderly people to clarify the findings of literature and to investigate the relation between two very common psychosocial factors and the most important metabolic parameters. We selected 106 elderly healthy subjects from The Massa Lombarda Project (MLP). We explored the relationship between depression and Perceived Mental Stress with a number of blood and clinical features related to lipidic and glycaemic metabolism, in order to find possible correlations which could be referable to the pathophysiologic mechanisms of metabolic impairment observed in subjects with psychosocial disorders. We included the diagnostic criteria of MS (blood pressure, waist circumference, glycaemia, HDL-c, triglycerides), besides a few parameters to evaluate body mass (BMI), renal function (creatinine), complete lipid profile (TC and LDL-c) and parameters correlated to a pro-inflammatory state and oxidative stress (fibrinogen, SUA), which are often involved into atherosclerosis development. .

Materials and methods

We carried out a psychosocial investigation in a cohort of elderly subjects from MLP to discover a probable correlation between some behavior-psychological aspects and different metabolic markers. MLP is a longitudinal observational epidemiological study including 7000 subjects over 20 years old residents in Massa Lombarda, a North-Italian rural town. The elderly people of this population (N.1000 over 75 years) were submitted to a more complex analysis, as part of the study on health status in European aging populations, aimed to reveal the determinants influencing healthy aging and to identify their impact on mortality, cardiovascular and respiratory morbidity, disability and quality of life [Nascetti et al., 2004]. We selected 106 elderly subjects (M:58, F:48), mean age 79,5 ± 3,8 years old, who did not suffer from chronic and severe disabling diseases and had a complete self-sufficiency. No subject had a history of depression or anxiety disorder, nor was taking antidepressant medication when the study was performed. We administered to this group the Perceived Stress Questionnaire (PSQ) and the Self Rating Depression Scale (SRDS) to evaluate the degree and distribution of perceived stress and depression. Levenstein et al. have published the PSQ ten years ago, to overcome some difficulties concerning the definition and measurement of stress focusing on the individual's subjective perception and emotional response [Fliege et al., 2005]. This questionnaire is based on a range-score from 0 (lowest level of perceived stress) to 1 (highest level of perceived stress). The Zung SRDS is a short self-administered survey to quantify the depressed status of a patient, based on range-score from 25 to 80 Z, which define four levels of depression for each subject [Zung, 1965]. We considered the mean value for each metabolic parameter (Total Cholesterol, LDL-c, HDL-c, Triglycerides, Glucose, Fibrinogen, SUA levels), blood pressure and anthropometric index (Body Mass Index and Waist Circumference) of six consecutive measurements, collected into the database of MLP in the recent past (five years). All laboratory measurements were carried out using standardized immunoenzymatic methods; only HDL-c serum levels were determined after precipitation of 1,006 g/ml bottom infranatant with dextran sulphate/magnesium chloride [Warnick, Benderson & Albers, 1982], whereas LDL-c was estimated through the Friedewald Formula. Data were statistically processed with SPSS software, version 16.0 for Windows. We performed a complete descriptive analysis of all studied parameters, followed by a multiple regression (adjusted for age and gender) aimed to discover a relationship between two psychosocial factors and several metabolic risk markers.

Results

The biochemical and anthropometric characteristics of the sample concerning metabolic profile and cardiovascular risk are reported in Table 1. Most of the elderly subjects (53.4%) had Total Cholesterol (TC) levels lower than 200 mg/dL, while 29.1% had levels ranging between 200 and 239 mg/dL and 17.5 % had TC levels higher than 240 mg/dL; 25,5% of the subjects reported LDL-c levels lower than 100 mg/dL, 25.5 % reported LDL-c levels between 100 mg/dL and 130 mg/dL, 24.5% had borderline–high concentrations of LDL-c levels between 130 mg/dL and 160 mg/dL, while the remaining 24.5% had high LDL-c values beyond 160 mg/dL. Most of the subjects (76.5 %) had HDL-c values higher than 40 mg/dL and fibrinogen blood levels below 400 mg/dL; while 74.4% of the subjects reported glucose blood levels lower than 100 mg/dL,16.1% reported glucose blood levels between 100 and 126 mg/dL and just 9.2% of the subjects suffered from diabetes. Most of the subjects (81.6%) had triglycerides serum levels below 150 mg/dL, 9.7% had borderline-high levels (between 150 mg/dL and 199 mg/dL, and l8.7% had high levels higher than 200 mg/dL. Moreover we found that 23% of our sample had a normal BMI (lower than 25 kg/m2), while 45% were overweight and 27% were obese (BMI between 25 and 30 kg/m2 and higher than 30 kg/m2 respectively). Psychometric evaluations with PSQ and Zung SRDS (Table 2) showed that no critical depression and stress scores were registered. We found a PSQ Index lower than 0.10 in 46.7% of elderly group, a PSQ Index between 0.10 and 0.35 in 37.8 % and values between 0.35 and 0.70 in the remaining subjects. Most of elderly people were not depressed (65%), whereas l8% of the subjects suffered from moderate depression and 17% from mild depression. The multiple linear regression analysis (adjusted for age and gender) showed a negative correlation between PSQ Index score and SUA, LDL-c, BMI, Systolic and Diastolic Blood Pressure values, a positive and statistically significant correlation between PSQ Index score and Triglycerides (P<0.05). We found an inverse relationship between Zung SRDS score and LDL-c, SUA, Glucose, Waist Circumference values. This correlation was significant only for SUA (P<0.01). Besides a positive and significant correlation between Zung SRDS and Triglycerides (P<0.05) was observed (Table 3, Table 4).

Table 1.

Biochemical and anthropometric characteristics of the elderly group.

| Laboratory Values (mg/dL) | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | SDˆ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cholesterol | 116.0 | 308.0 | 202.7 | 41.7 |

| LDL-c* | 57.0 | 226.0 | 131.60 | 37.7 |

| HDL-c** | 10 | 93 | 49.0 | 12.7 |

| Triglycerides | 38.0 | 482.0 | 112.6 | 63.3 |

| Glycemia | 52.0 | 214.0 | 95.3 | 24.6 |

| Fibrinogen | 155.0 | 428.0 | 269.6 | 64.8 |

| Creatinine | 0.40 | 2.10 | 1.06 | 0.27 |

| BMI (Kg/m2)*** | 20.02 | 44.43 | 27.8 | 4.2 |

| Waist Circumference (cm) | 63 | 131 | 98.2 | 11.9 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mmHg) | 110 | 190 | 145 | 14.9 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure (mmHg) | 60 | 112 | 80 | 9.2 |

Standard Deviation

Low Density Lipoprotein cholesterol

High Density Lipoprotein cholesterol

Body Mass Index

Table 2.

Psycometric Test values in the elderly sample

Standard Deviation

Perceived Stress Questionnaire

Self Rating Depression Scale

Table 3.

Multiple Regression between Metabolic parameters and PSQ Index

| Independent Variables | t | P |

|---|---|---|

| TCˆ | ,619 | ,542 |

| Triglycerides | 2,462 | ,022 |

| HDL-cˆˆ | ,585 | ,564 |

| LDL-cˆˆˆ | -,164 | ,871 |

| Uric Acid | -1,820 | ,082 |

| Glycemia | ,949 | ,352 |

| Fibrinogeno | 1,298 | ,207 |

| BMIˆˆˆˆ | -1.054 | ,301 |

| Waist Circumference | ,442 | ,663 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure | -,682 | ,500 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure | -,299 | ,766 |

Dependent Variable: PSQ Index

Weighted Least Squares Regression -Weighted by Sex (M-F)

Total Cholesterol

High Density Lipoprotein cholesterol

Low Density Lipoprotein cholesterol

Body Mass Index

Table 4.

Multiple Regression between Metabolic parameters and ZUNG SRDS

| Independent Variables | t | P |

|---|---|---|

| TCˆ | 1,817 | ,081 |

| Triglycerides | 2,115 | ,045 |

| HDL-cˆˆ | 1,424 | ,167 |

| LDL-cˆˆˆ | -,251 | ,804 |

| Uric Acid | -3,071 | ,005 |

| Glycemia | -1,324 | ,198 |

| Fibrinogeno | 1,623 | ,117 |

| BMIˆˆˆˆ | 2,268 | ,032 |

| Waist Circumference | -1,147 | ,259 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure | ,813 | ,423 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure | ,510 | ,614 |

| Age | -1,499 | ,146 |

Total Cholesterol

High Density Lipoprotein cholesterol

Low Density Lipoprotein cholesterol

Body Mass Index

Dependent Variable: Zung SRDS

Weighted Least Squares Regression - Weighted by Sex (M-F)

Discussion

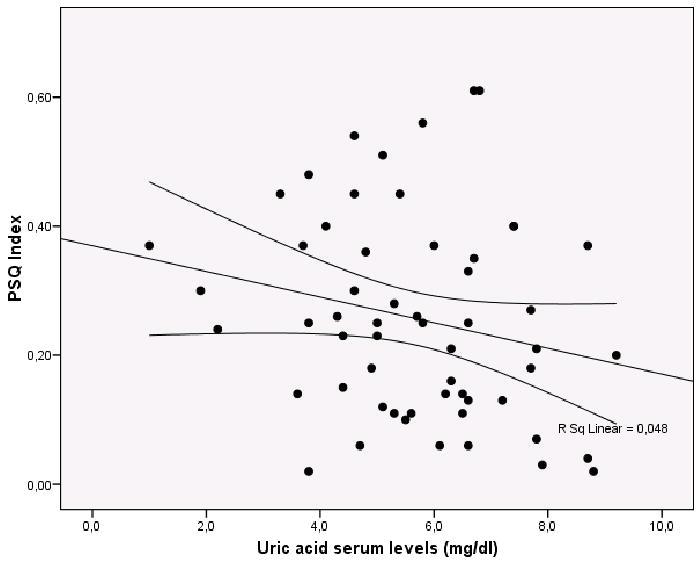

Psychosocial factors contribute significantly to pathogenesis and expression of CVD, this evidence is composed largely of data relating CVD risk to five specific psychosocial domains: depression, anxiety, personality factors, character traits, social isolation and chronic life stress [Rozanski et al., 1999; Rozanski et al., 2005]. Pathophysiological process, underlying the relationship between these entities and CVD, can be divided into behavioural mechanisms, whereby psychosocial conditions contribute to an adverse health conduct (poor diet, smoking habit, worse adherence to prescribed medication), and direct pathophysiological mechanisms such as neuroendocrine and platelet activation [Black & Garbutt, 2002]. Several authors suggested the effects of psychosocial factors as independent predictors of CVD and proved that these effects could be mediated by MS, as a complex function of stress-related biological mechanisms [Frisman & Kristenson, 2009]. We found in our group of elderly subjects a positive correlation between Triglycerides values and both PSQ index (P<0.05) and Zung SRDS (P<0.05) which confirms data reported in literature [Dimsdale & Herd, 1982]. Indeed these associations underline a tendency to develop MS or lipid profile alterations in stressed or depressed elderly patients [Weber-Hamann et al., 2002; Keyes, 2004]. Moreover we found a negative relation between SUA levels and both PSQ Index (P=0.08) and Zung SRDS (P=0.005) (Figure 1) (Figure 2). The SUA level is affected by age and by genetic and environmental factors [Kasl, Cobb & Brooks, 1968; Kuzuya et al., 2008]. There are in literature different controversial opinions concerning the anti-oxidant effect of SUA and its well-known role as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular diseases and cardiovascular mortality [Lippi, Montagnana, Franchini, Favaloro & Targher, 2008; Niskanen et al., 2004, Halliwell, 1996; Menotti et al., 2005]. The question is further motivated by the apparently dual effect of SUA per se as an oxidant/antioxidant agent. It has been hypothesized that antioxidant properties should be protective against aging, oxidative stress, and oxidative injury of cardiac, vascular, and neural cells [Glantzounis et al, 2005; Stocker & Keaney, 2004]. However, as the findings of recent studies have unfolded, a new paradigm shift in the relationship between SUA and health is emerging. Antioxidant compounds may become pro-oxidant compounds in certain situations [Bagnati et al, 1999], particularly when they are present in blood at very high levels. Therefore, according to this opinion, SUA is a protective agent against oxidative stress and all its possible consequences such as a rapid atherosclerosis development. Moreover oxidative stress may also be involved primarily or secondarily in the pathogenesis of depression, since the brain is much more vulnerable to oxidative stress as it uses 20% of the oxygen consumed by the body. The negative correlation between SUA and Zung test provides additional support to the hypothesis that this metabolic parameter is a strategic and important component of the antioxidant defence system. Further well designed clinical studies are needed to clarify a potential therapeutic use of uric acid (or uric acid precursors) in diseases associated with oxidative stress.

Fig 1.

Negative correlation of Uric Acid Serum levels (mg/dL) and Zung SRDS score (P<0.01)

Fig 2.

Negative correlation of Uric Acid Serum levels (mg/dL) and PSQ Index score (P=0.08)

Conclusion

Our results confirm data reported in literature concerning a possible relationship between psychosocial markers and cardiovascular risk factors. The positive correlation between Triglycerides values and both PSQ index and Zung SRDS seems to underline the frequent metabolic changes that could even reveal a MS rising in stressed or depressed elderly subjects. The issue concerning the role of SUA is still confounded and made difficult by the powerful interrelations between this metabolic parameter and all CVD risk factors, that were clustered in the MS diagnosis. The negative correlation between SUA and Zung test support the already cited hypothesis that this metabolic element is a non-enzymatic antioxidant molecule with a potential therapeutic role.

References

- Alberti KG, Zimmet P, Shaw J IDF Epidemiology Task Force Consensus Group. The metabolic syndrome--a new worldwide definition. Lancet. 2005;366(9491):1059–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67402-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagnati M, Perugini C, Cau C, Bordone R, Albano E, Bellomo G. When and why a water-soluble antioxidant becomes pro-oxidant during copper-induced low density lipoprotein oxidation: a study using uric acid. Biochem J. 1999;340:143–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black PH, Garbutt LD. Stress inflammation and cardiovascular disease. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52:1–23. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00302-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL, Salive ME, Harris TB, Simonsick EM, Guralmik JM, Kohout FJ. Low cholesterol concentrations and severe depressive symptoms in elderly people. BMJ. 1994;308:1328–1332. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6940.1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimsdale JE, Herd JA. Variability of plasma lipids in response to emotional arousal. Psychosom Med. 1982;44(5):413–30. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198211000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimsdale JE. Psychological stress and cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(13):1237–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.12.024. Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fliege H, Rose M, Arck P, Walter OB, Kocalevent RD, Weber C, Klapp BF. The Perceived Stress Questionnaire (PSQ) Reconsidered: Validation and Reference Values From Different Clinical and Healthy Adult Samples. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:78–88. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000151491.80178.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisman GH, Kristenson M. Psychosocial status and health related quality of life in relation to the metabolic syndrome in a Swedish middle-aged population. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2009.01.004. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glantzounis GK, Tsimoyiannis EC, Kappas AM, Galaris DA. Uric acid and oxidative stress. Curr Pharm Des. 2005;11:4145–51. doi: 10.2174/138161205774913255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell B. Uric acid: An example of antioxidant evaluation. In: Cadenas E, Packer L, editors. Handbook of antioxidants. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1996. pp. 243–256. [Google Scholar]

- Kasl SV, Cobb S, Brooks GW. Changes in serum uric acid and cholesterol levels in men undergoing job loss. Jama. 1968;206:1500–07. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes CL. The nexus of cardiovascular disease and depression revisited: the complete mental health perspective and the moderating role of age and gender. Aging Ment Health. 2004;8(3):266–74. doi: 10.1080/13607860410001669804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodydková J, Vávrová L, Zeman M, Jirák R, Macásek J, Stanková B, Zák A. Antioxidative enzymes and increased oxidative stress in depressive women. Clinical Biochemistry. 2009;42(13-14):1368–74. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzuya M, Ando F, Iguchi A, Shimokata H. Effect of Aging on Serum Uric Acid Levels: Longitudinal Changes in a Large Japanese Population Group. J Jerontol. 2002;57(10):660–664. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.10.m660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebowitz BD, Pearson JL, Schneider LS, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Alexopoulos GS, Bruce ML, Parmelee P. Diagnosis and treatment of depression in late life. Consensus statement update. JAMA. 1997;278(14):1186–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippi G, Montagnana M, Franchini M, Favaloro EJ, Targher G. The paradoxical relationship between serum uric acid and cardiovascular disease. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2008;392(1-2):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2008.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre RS, Rasgon NL, Kemp DE, Nguyen HT, Law CW, Taylor VH, Goldstein BI. Metabolic syndrome and major depressive disorder: co-occurrence and pathophysiologic overlap. Current Diabetes Reports. 2009;9(1):51–9. doi: 10.1007/s11892-009-0010-0. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menotti A, Lanti M, Agabiti-Rosei E, Caratelli L, Cavera G, Dormi A, Zanchetti A. New tools for prediction of cardiovascular disease risk derived from Italian population studies. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2005;15:426–40. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nascetti S, Linarello S, Scurti M, Grandi E, Gaddoni M, Noera G, Gaddi A. Assessment of the health status in the Massa Lombarda cohort: a preliminary description of the program evaluating cardiocerebro-vascular disease risk factors and quality of life in an elderly population. Arch Gerontol Geriatr Suppl. 2004;9:309–14. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2004.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niskanen LK, Laaksonen DE, Nyyssönen K, Alfthan G, Lakka HM, Lakka TA, Salonen JT. Uric acid level as a risk factor for cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in middle-aged men: a prospective cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1546–51. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.14.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds K, He J. Epidemiology of the metabolic syndrome. Am J Med Sci. 2005;330(6):273–9. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200512000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strodl E, Kenardy J, Aroney C. Perceived stress as a predictor of the self-reported new diagnosis of symptomatic CHD in older women. Int J Behav Med. 2003;3(10):205–20. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1003_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosengren A, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Sliwa K, Zubaid M, Almahmeed WA INTERHEART investigators. Association of psychosocial risk factors with risk of acute myocardial infarction in 11119 cases and 13648 controls from 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364(9438):953–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozanski A, Blumenthal JA, Kaplan J. Impact of Psychological Factors on the Pathogenesis of Cardiovascular Disease and Implications for Therapy. Circulation. 1999;99:2192–2217. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.16.2192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozanski A, Blumenthal JA, Davidson KW, Saab PG, Kubzansky L. The epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management of psychosocial risk factors in cardiac practice: the emerging field of behavioral cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45(5):637–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.12.005. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarandol A, Sarandol E, Eker SS, Erdinc S, Vatansever E, Kirli S. Major depressive disorder is accompanied with oxidative stress: short-term antidepressant treatment does not alter oxidative-antioxidative systems. Human Psychopharmacology. 2007;22(2):67–73. doi: 10.1002/hup.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker R, Keaney JF., Jr Role of oxidative modifications in atherosclerosis. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:1381–478. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00047.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsouli SG, Liberopoulos EN, Mikhailidis DP, Athyros VG, Elisaf MS. Elevated serum uric acid levels in metabolic syndrome: an active component or an innocent bystander? Metabolism. 2006;55(10):1293–301. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2006.05.013. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Kooy K, van Hout H, Marwijk H, Marten H, Stehouwer C, Beekman A. Depression and the risk for cardiovascular diseases: systematic review and meta analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(7):613–26. doi: 10.1002/gps.1723. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Reedt Dortland AK, Giltay EJ, van Veen T, van Pelt J, Zitman FG, Penninx BW. Associations between serum lipids and major depressive disorder: results from the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA) J Clin Psychiatry. 2009 doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04865blu. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnick GR, Benderson J, Albers JJ. Dextran sulfate-Mg2+ precipitation procedure for quantitation of high-densitylipoprotein cholesterol. Clin Chem. 1982;28:1379–1388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber-Hamann B, Hentschel F, Kniest A, Deuschle M, Colla M, Lederbogen F, Heuser I. Hypercortisolemic depression is associated with increased intra-abdominal fat. Psychosom Med. 2002;64:274–7. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200203000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zauszniewsk JA, Bekhet AK. Depressive symptoms in elderly women with chronic conditions: Measurement issues. Aging Ment Health. 2009;13:64–72. doi: 10.1080/13607860802154481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zung WA. Self-Rating Depression scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;12:63–70. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1965.01720310065008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]