Abstract

Fusion of the prostate-specific and androgen-regulated transmembrane-serine protease gene (TMPRSS2) with the erythroblast transformation-specific (ETS) family members is the most common genetic alteration in prostate cancer. However, the biological and clinical role of TMPRSS2-ETS fusions in prostate cancer, especially in problematic prostate needle core biopsies, has not been rigorously evaluated. We randomly collected 85 specimens including 50 archival prostate cancer tissue blocks, 15 normal prostate specimens, and 20 benign prostatic hyperplasia specimens for TMPRSS2-ETS fusion analyses. Moreover, the fusion status in an additional 20 patients with initial negative biopsies who progressed to biopsy-positive prostate cancer at subsequent follow-ups was also characterized. Fluorescently labeled probes specific for ERG-related rearrangements involving the TMPRSS2-ERG fusion as well as TMPRSS2-ETV1 and TMPRSS2-ETV4 were used to assess samples for gene rearrangements indicative of malignancy under a design of sequential trial. Rearrangements involving TMPRSS2-ETS fusions were detected in 90.0% of the 50 postoperative prostate cancer samples. The positive rate for the rearrangements in the initial prostate cancer-negative biopsies of 20 patients who eventually progressed to prostate cancer was 60.0% (12/20). Our preliminary study demonstrates that the clinical utility of TMPRSS2-ETS fusion detection as a biomarker and ancillary diagnostic tool for the early diagnosis of prostate cancer is promising, given this approach shows significant high sensitivity and specificity in detection.

Serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) measurement has led to a dramatic increase in prostate cancer detection. It has the advantage of being a noninvasive approach. However, there is little doubt that it has great limitations as well. For example, PSA is often elevated in benign conditions, such as benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostatitis, likely accounting for the poor specificity of the PSA test, which has been reported to be only 20% at a sensitivity of 80%.1 This can readily be explained by the fact that PSA is not specific for prostate cancer. One approach to improve diagnostic accuracy of tests for prostate cancer is to identify prostate cancer-specific genes.

Recently, fusion of the prostate-specific and androgen-regulated transmembrane-serine protease gene (TMPRSS2) with the erythroblast transformation-specific (ETS) family members (eg, ERG, ETV1, and ETV4) was identified as a common molecular event in prostate cancer.2,3 ERG-related rearrangements mainly involving the TMPRSS2-ERG fusion were present in 40 to 80% of primary prostate cancer. Additionally, the TMPRSS2-ETV1 fusion had a prevalence of approximately 1 to 27% of PSA-screened prostate cancer,2,4,5,6 whereas the TMPRSS2-ETV4 fusion was identified with a prevalence of only 1.02%.3 Furthermore, Perner et al7 confirmed that the TMPRSS2-ERG fusion occurred early in the development of invasive prostate adenocarcinoma. Thus, these studies highlighted the potential of TMPRSS2-ETS gene fusions to serve as a specific biomarker for the early diagnosis of prostate cancer and to play an important role in the pathogenesis of prostate cancer.

In the present study, we first analyzed a series of 50 formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded prostate cancers for the detection of ERG related rearrangements, TMPRSS2-ETV1 and TMPRSS2-ETV4 fusion genes using a multiprobe fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) assay. Moreover, the fusion status in an additional 20 patients with initial prostate cancer-negative biopsies who progressed to biopsy-positive cancer at subsequent follow-ups was also characterized to determine whether the TMPRSS2-ETS fusion could become an effective biomarker for the early diagnosis of prostate cancer.

Materials and Methods

Tissue Specimens

We randomly selected 50 archival prostate adenocarcinoma blocks from patients operated in the Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University between March 2005 and May 2009. The preoperative serum PSA level, pTNM stage, and Gleason score from all of the cases are indicated in Table 1. In addition, we randomly collected 20 benign prostatic hyperplasia samples from patients who underwent transurethral resection of the prostate between June 2003 and May 2004, and 15 normal prostate specimens from male patients undergoing radical cystectomy between January 2003 and June 2004 as controls.

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic Characteristics and TMPRSS2-ETS Fusion Status of 50 Prostate Cancer Patients

|

TMPRSS2− |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case no. | Age (year) | PSA (ng/ml) | Operation | pTNM | Gleason score | ERG | ETV1 | ETV4 |

| 1 | 68 | 3.6 | RP | pT2cN0M0 | 2 + 2 | neg | pos | NA |

| 2 | 69 | 3.74 | RP | pT1cN0M0 | 1 + 2 | pos | NA | NA |

| 3 | 71 | 4.33 | RP | pT2cN0M0 | 3 + 3 | neg | pos | NA |

| 4 | 85 | 5.74 | RP | pT1cN0M0 | 2 + 3 | neg | neg | neg |

| 5 | 69 | 6.79 | RP | pT2N0M0 | 2 + 3 | neg | neg | neg |

| 6 | 72 | 7.04 | RP | pT2cN0M0 | 3 + 5 | pos | NA | NA |

| 7 | 72 | 8.58 | RP | pT2cN0M0 | 3 + 3 | pos | NA | NA |

| 8 | 72 | 10.15 | RP | pT1cN0M0 | 1 + 2 | neg | pos | NA |

| 9 | 50 | 12 | RP | pT2aN0M0 | 2 + 1 | pos | NA | NA |

| 10 | 79 | 12 | RP | pT1cN0M0 | 2 + 2 | pos | NA | NA |

| 11 | 79 | 12.81 | RP | pT2cN0M0 | 2 + 3 | pos | NA | NA |

| 12 | 77 | 14.6 | RP | pT1cN0M0 | 2 + 2 | pos | NA | NA |

| 13 | 69 | 16.98 | RP | pT2cN0M0 | 2 + 3 | pos | NA | NA |

| 14 | 75 | 18.65 | RP | pT1cN0M0 | 2 + 2 | pos | NA | NA |

| 15 | 72 | 21.83 | RP | pT2cN0M0 | 3 + 4 | pos | NA | NA |

| 16 | 73 | 22 | RP | pT2cN0M0 | 2 + 4 | pos | NA | NA |

| 17 | 82 | 22.48 | RP | pT2cN0M0 | 2 + 4 | pos | NA | NA |

| 18 | 69 | 27.06 | RP | pT2cN0M0 | 4 + 4 | pos | NA | NA |

| 19 | 71 | 28.73 | RP | pT2aN0M0 | 2 + 3 | pos | NA | NA |

| 20 | 68 | 29.49 | RP | pT3aN1M0 | 4 + 4 | pos | NA | NA |

| 21 | 63 | 30.97 | RP | pT2aN0M0 | 2 + 3 | pos | NA | NA |

| 22 | 71 | 35.67 | RP | pT3N0M0 | 3 + 4 | pos | NA | NA |

| 23 | 64 | 38.2 | RP | pT2cN0M0 | 1 + 2 | pos | NA | NA |

| 24 | 75 | 45 | RP | pT2cN1M0 | 4 + 5 | pos | NA | NA |

| 25 | 75 | 49.22 | RP | pT2cN0M0 | 5 + 3 | pos | NA | NA |

| 26 | 68 | 89.92 | RP | pT3aN1M0 | 3 + 3 | neg | neg | neg |

| 27 | 68 | 89.92 | RP | pT3aN1M0 | 3 + 3 | pos | NA | NA |

| 28 | 62 | 91.7 | RP | pT3aN0M0 | 4 + 5 | pos | NA | NA |

| 29 | 61 | 100 | RP | pT2cN1M0 | 3 + 4 | pos | NA | NA |

| 30 | 68 | 100 | RP | pT3N0M0 | 4 + 5 | pos | NA | NA |

| 31 | 67 | 175.6 | RP | pT2cNxM0 | 5 + 3 | neg | pos | NA |

| 32 | 56 | 454 | RP | pT3bN1M0 | 4 + 5 | pos | NA | NA |

| 33 | 71 | 653 | RP | pT2cN1M1 | 4 + 5 | pos | NA | NA |

| 34 | 72 | 3.55 | RP | pT3aN0M0 | 5 + 5 | neg | neg | neg |

| 35 | 54 | 9.42 | RP | pT2cN1M0 | 4 + 5 | pos | NA | NA |

| 36 | 68 | 14.95 | RP | pT2bN0M0 | 4 + 4 | pos | NA | NA |

| 37 | 76 | 19.9 | RP | pT1cN0M0 | 1 + 2 | pos | NA | NA |

| 38 | 62 | 71.79 | RP | pT3aN1M0 | 5 + 4 | pos | NA | NA |

| 39 | 68 | 84.4 | RP | pT3aN1M0 | 4 + 5 | pos | NA | NA |

| 40 | 77 | 116 | RP | pT4N1M0 | 5 + 4 | pos | NA | NA |

| 41 | 62 | 420.81 | RP | pT4N1M0 | 5 + 4 | neg | neg | pos |

| 42 | 75 | 820 | RP | pT3aN1M1 | 4 + 5 | pos | NA | NA |

| 43 | 66 | 2.75 | RP | pT1cN0M0 | 1 + 1 | neg | pos | NA |

| 44 | 64 | 9.8 | TURP | pT1cNxM0 | 4 + 5 | pos | NA | NA |

| 45 | 80 | 30.94 | TURP | pT2cNxM0 | 5 + 5 | neg | neg | neg |

| 46 | 91 | 40.31 | TURP | pT4N1M0 | 5 + 5 | pos | NA | NA |

| 47 | 81 | 41 | TURP | pT2cNxM0 | 5 + 4 | pos | NA | NA |

| 48 | 81 | 90.32 | TURP | pT4N1M0 | NA | pos | NA | NA |

| 49 | 70 | 180 | TURP | pT2aNxM0 | 2 + 3 | pos | NA | NA |

| 50 | 74 | 600 | TURP | pT2cNxM0 | 4 + 5 | pos | NA | NA |

PSA indicates prostate-specific antigen; RP, radical prostatectomy; TURP, transurethral resection of the prostate; pos, positive; neg, negative; NA, not available.

Furthermore, we selected 20 additional prostate cancer patients whose initial prostate biopsies were negative for cancer between May 2005 and February 2008. Their diagnoses of prostate cancer were established by repeat biopsies at subsequent follow-ups (Table 2). The TMPRSS2-ETS fusion status was examined in the initial prostate biopsy specimens by a multiprobe FISH assay. The Institutional Ethics Committee approved this study, and all patients provided their written informed consent to this work.

Table 2.

Clinical and Pathologic Characteristics of 20 Patients with Initial Prostate Cancer-Negative Biopsy

|

TMPRSS2− |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case no. | Age (year) | PSA (ng/ml) | Initial biopsy | ERG | ETV1 | ETV4 | Follow-up (mo) | Repeat biopsy |

| 51 | 57 | 8.3 | BPH | pos | NA | NA | 30 | Gleason2 + 1 |

| 52 | 77 | 9.7 | Focal BMD | pos | NA | NA | 24 | Gleason3 + 2 |

| 53 | 73 | 9.1 | BPH with focal BMD | pos | NA | NA | 28 | Gleason2 + 1 |

| 54 | 60 | 9.3 | BPH with focal BMD | pos | NA | NA | 19 | Gleason2 + 2 |

| 55 | 68 | 10.2 | Focal BMD | neg | neg | pos | 38 | Gleason2 + 1 |

| 56 | 54 | 7.9 | BPH | pos | NA | NA | 30 | Gleason1 + 2 |

| 57 | 66 | 10.2 | BPH with focal BMD | neg | pos | NA | 24 | Gleason2 + 2 |

| 58 | 71 | 9.4 | BPH with focal BMD | pos | NA | NA | 21 | Gleason2 + 2 |

| 59 | 69 | 11.4 | Focal BMD | neg | pos | NA | 25 | Gleason2 + 3 |

| 60 | 79 | 8.5 | BPH | pos | NA | NA | 35 | Gleason2 + 2 |

| 61 | 78 | 8.67 | BPH | pos | NA | NA | 42 | Gleason3 + 3 |

| 62 | 62 | 7.9 | BPH with focal BMD | pos | NA | NA | 34 | Gleason2 + 2 |

| 63 | 67 | 10.4 | BPH with focal BMD | neg | neg | neg | 23 | Gleason2 + 3 |

| 64 | 68 | 9.8 | PIN II with focal BMD | neg | neg | neg | 18 | Gleason1 + 2 |

| 65 | 65 | 9.55 | Focal BMD | neg | neg | neg | 31 | Gleason2 + 3 |

| 66 | 62 | 7.9 | Focal BMD | neg | neg | neg | 27 | Gleason3 + 4 |

| 67 | 69 | 9.3 | BPH with focal BMD | neg | neg | neg | 15 | Gleason2 + 3 |

| 68 | 68 | 8.9 | BPH | neg | neg | neg | 36 | Gleason2 + 2 |

| 69 | 68 | 9.6 | BPH | neg | neg | neg | 48 | Gleason4 + 3 |

| 70 | 76 | 10 | PIN II with focal BMD | neg | neg | neg | 24 | Gleason2 + 1 |

PSA indicates prostate-specific antigen; BPH, benign prostatic hyperplasia; BMD, basement membrane disruption; PIN, prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia; pos, positive; neg, negative; NA, not available.

Pathological Analyses

Histopathological diagnosis was confirmed by two independent pathologists (Z.-L.S. and D.H.) on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained paraffin sections of each sample before FISH assessment. The morphological criteria for ‘normal,’ ‘benign prostatic hyperplasia,’ ‘prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia, ’ and ‘malignant prostatic epithelium’ conformed to previously published definitions.8,9,10 Immunostaining was performed using an avidin-biotin complex staining procedure as needed. Antigen retrieval was performed by treating with citrate buffer (pH 6.0) in a microwave oven for 15 minutes, with no tissue dropout. A cocktail of the three antibodies, including a rabbit monoclonal antibody to AMACR (P504S, Corixa, Seattle, WA) at a 0.5 μg/ml dilution, a mouse monoclonal antibody (34βE12, DAKO) to high-molecular-weight cytokeratin at a dilution of 1:50, and a mouse monoclonal antibody to p63 (NeoMarkers, Fremont, CA) at 0.5 μg/ml was mixed and applied to the tissue sections for 45 minutes. After a buffer rinse, the polymer-based secondary antibodies with a mixture of anti-rabbit-alkaline phosphatase and anti-mouse-horseradish peroxidase conjugates (Biocare Medical, Walnut Creek, CA) were applied for 25 minutes. For double-color reactions, NBT (nitro blue tetrazolium) substrate buffer was subsequently developed for 8 minutes for AMACR, then AEC (3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole) substrate buffer for 34βE12 and p63 was developed for 10 minutes. After development, the slides were rinsed in distilled water, counterstained with hematoxylin, and rinsed again. The slides were allowed to air dry and were coverslipped with permanent mounting media. Positive basal cell staining for 34βE12 and p63 was defined as red nuclear and/or cytoplasmic staining in the basal cells. Positive AMACR staining was defined as continuous dark brown cytoplasmic staining or apical granular staining patterns in the epithelial cells. In addition, negative control staining with no primary antibody was performed, and prostate tissue from autopsy was used as a positive control.11,12

FISH Analyses

Bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clones for TMPRSS2 (RP11-814F13, RP1-265B9, and CTD-2337B13), ERG (RP11-476D17 and RP11-95I21), ETV1 (RP11-692G10, RP5-856O24, and CTD-2134C13), and ETV4 (CTD-2326M16, RP11-100E5, and CTC-420I11) were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). All of the BAC clones were directly labeled as probes by nick translation with fluorescein and/or tetramethylrhodamine (Beijing GP Medical Technologies, Inc., P.R. China). BAC clone information was obtained through the website of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), and the probes were confirmed to map to the precise chromosome bands by using metaphase spreads from the blood lymphocytes of healthy donors. FISH was performed according to the manufacturer's protocols (Beijing GP Medical Technologies, Inc., P.R. China) with some minor modifications. Briefly, 3-μm tissue sections were obtained from the tissue blocks and mounted on poly-L-lysine coated slides. After deparaffinization, the tissue sections were dehydrated in 100%, 85%, and 70% ethanol for 2 minutes each. After washing in deionized water for 5 minutes, the sections were boiled in deionized water at 100°C for 27 minutes and then digested with Proteinase K (200 μg/ml) at 37°C for 7–15 minutes. Subsequently, the sections were washed twice in 2× saline/sodium citrate (SSC) for 5 minutes, fixed in 1% formaldehyde solution for 10 minutes, and dehydrated in an ethanol series for 2 minutes each. The sections on slides were then dried and 10 μl of probe mix solution (1 μl probe mix, 7 μl hybridization, and 2 μl water) was applied over the target area on each slide. The slides were then coverslipped, sealed with rubber cement, and codenatured at 84°C for 8 minutes and hybridized at 42°C for 16 hours. Posthybridization washing was done with 2× SSC/0.1%NP-40 for 5 minutes and then 70% ethanol for 5 minutes. The section slides were counterstained, mounted by DAPI, and examined under oil objective original magnification (×100) using an Olympus fluorescence microscope (Olympus Co., Tokyo, Japan) and imaged with a CCD camera using the IMSTAR software system (IMSTAR S.A., Paris, France).

Criteria that Determined FISH Positivity

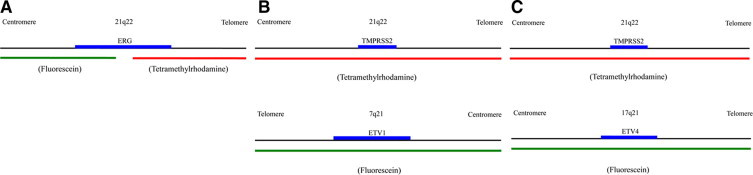

A break-apart-rearrangement model was designed for the ERG probe (Figure 1A). This design permitted the detection of rearrangements between the ERG gene and a partner gene, such as TMPRSS2, as well as deletion of the gene. Two yellow (red/green fusion) signals in a cell indicated a normal signal pattern, whereas one yellow/one green (or one red) or one yellow/one green/one red in a cell commonly represented abnormal signal patterns indicative of partial deletion or translocation, respectively. A dual-color dual-fusion model was used for the design of TMPRSS2-ETV1 and TMPRSS2-ETV4 fusion probes (Figure, 1B and 1C). For a normal signal pattern, two red/two green signals should be observed in a cell, whereas one green/one red/two yellow signals in a cell indicated an abnormal signal pattern.

Figure 1.

A schematic illustration of the design and labeling models for the ERG break-apart rearrangement probe (A), the TMPRSS2-ETV1 dual-color dual-fusion probe (B), and the TMPRSS2-ETV4 dual-color dual-fusion probe (C).

The criteria for FISH positivity were determined by evaluating specimens from 50 prostate cancer patients (case 1–50) and 35 controls (20 cases with benign prostatic hyperplasia and 15 with normal prostates) based on the numbers of cells with abnormal signal patterns for TMPRSS2-ETS fusions. A receiver operator characteristics curve, which compared the sensitivity and specificity of various cutoffs for numbers of cells with abnormal signal patterns, for these two groups of patients, was then used to determine the cutoff that should be used to interpret a positive result. In detail, for ERG related rearrangements, the optimal cutoff for positivity was seven or more cells with the abnormal signal pattern in a random count of at least 400 cells. For the TMPRSS2-ETV1 fusion, the optimal cutoff was three or more cells with the abnormal signal pattern in a random count of at least 400 cells. For the TMPRSS2-ETV4 fusion, the optimal cutoff was one or more cells with the abnormal signal pattern in a random count of at least 400 cells.

The prostate cancer specimens were analyzed by FISH under a design of sequential trial. That is, all specimens were initially carried on ERG related rearrangements detection; subsequently, the TMPRSS2-ETV1 probe was used to detect the specimens with negative ERG related rearrangements; finally, the negative specimens by both ERG related rearrangements and TMPRSS2-ETV1 detections underwent further analysis with the TMPRSS2-ETV4 probe. In detail, 50 sections were used for ERG related rearrangements detection; 11 sections for TMPRSS2-ETV1 fusion detection and 6 sections for TMPRSS2-ETV4 fusion detection in large tissue samples of prostate cancer. In biopsy tissue samples, we used 40 sections, 20 of which for ERG related rearrangements detection, 11 for TMPRSS2-ETV1 fusion, and 9 for TMPRSS2-ETV4 fusion.

In large specimens of normal prostate and benign prostatic hyperplasia, three sections (one for ERG related rearrangements detection, one for TMPRSS2-ETV1 fusion, and one for TMPRSS2-ETV4 fusion) were used in each case. Overall, 45 sections from normal prostate tissue and 60 from benign prostatic hyperplasia were used for the detection of ERG related rearrangements, TMPRSS2-ETV1 fusion, and TMPRSS2-ETV4 fusion. Evaluation of FISH results from each sample was independently performed by two experienced operators, and any discrepant scores were reexamined to achieve a consensus result.

Statistical Analyses

The sensitivity of the multiprobe FISH assay was determined for the 50 specimens with pathology proved prostate cancer. Associations between clinicopathologic parameters and the TMPRSS2-ETS fusion status were examined using Fisher's exact tests. Data were analyzed using SPSS 13.0 software package (SPSS, Chicago, IL), and a two-tailed P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

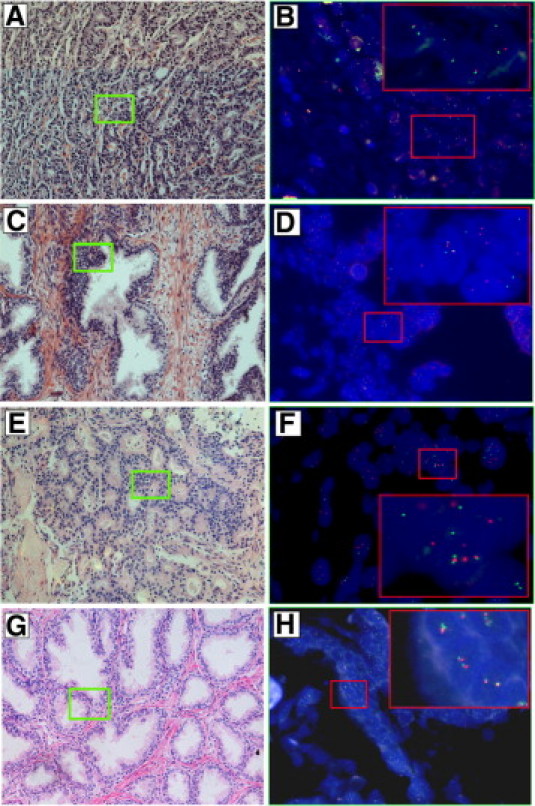

Under the design of sequential trial, we first conducted FISH detection on ERG-related rearrangements. Of the 50 prostate cancer samples, 39 (78.0%) demonstrated positive for ERG rearrangements (Figure, 2A and 2B). Of the remaining 11 cases that were negative for ERG related rearrangements, five cases were considered positive for TMPRSS2-ETV1 (Figure, 2C and 2D). In the remaining six cases with negative results for both the ERG and TMPRSS2-ETV1 probes, only one case was detected positive for the TMPRSS2-ETV4 fusion (Figure, 2E and 2F). Altogether, the positive rate for ERG related rearrangements as well as TMPRSS2-ETV1 and TMPRSS2-ETV4 fusions in the 50 prostate cancer samples was 90.0% (45/50).

Figure 2.

H&E stains and corresponding FISH images of the TMPRSS2-ETS fusion assay. A: Prostatic tissue with prostate cancer glands (Gleason score 5 + 3). B: FISH ERG probe image of the green boxed area in (A). The double-framed red inset is a magnification of the red boxed area showing three representative nuclei of a prostate cancer gland. Inset, Two nuclei with one yellow and one green signal, showing an ERG rearrangement involving partial deletion of the gene; a nucleus with one yellow, one green, and one red signal, showing an ERG rearrangement through translocation. C: Prostatic tissue with prostate cancer glands (Gleason score 2 + 2). D: FISH TMPRSS2-ETV1 probes image of the green boxed area in C. The double-framed red inset is a magnification of the red boxed area showing a representative nucleus with two yellow signals, indicating the TMPRSS2-ETV1 fusion. E: Prostatic tissue with prostate cancer glands (Gleason score 5 + 4). F: FISH TMPRSS2-ETV4 probes image of the green boxed area in E. The double-framed red inset is a magnification of the red boxed area showing a representative nucleus with two yellow signals, indicating the TMPRSS2-ETV4 fusion. G: Benign prostatic hyperplasia tissue. H: FISH ERG probe images of the green boxed areas in G. Each nucleus of the benign gland shows two yellow signals indicating absence of ERG related rearrangements. Original magnification of H&E images, ×20 objective. Original magnification of FISH images, oil objective (×100).

In contrast, none of the 15 normal prostate and 20 benign prostatic hyperplasia samples demonstrated the aforementioned genetic aberrations (Figure, 2G and 2H). There was no statistical significance between the TMPRSS2-ETS fusion status and Gleason score (P = 0.204). We also did not find any association between tumor stage and the TMPRSS2-ETS fusion status (P = 0.554). Similarly, no statistically significant association was found between preoperative PSA and the fusion status (P = 0.384, Table 1).

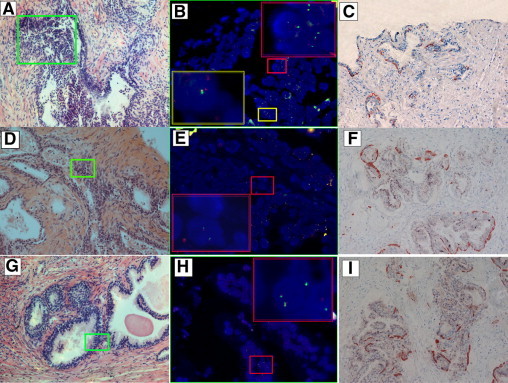

The additional 20 cases with initial negative biopsy results for cancer included six benign prostatic hyperplasia, seven benign prostatic hyperplasia with focal basement membrane disruption, five focal basement membrane disruption, and two high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia with focal basement membrane disruption (Table 2). All of these patients progressed to prostate adenocarcinoma as confirmed by subsequent repeat prostate biopsies at a mean time of 29.2 months of follow-up (median 27.5 months, range 15–48 months). Notably, in the initial prostate biopsy samples, nine cases were found positive for the ERG rearrangements (Figure 3, A–C), two cases positive for the TMPRSS2-ETV1 fusion (Figure 3, D–F), and one case positive for the TMPRSS2-ETV4 fusion (Figure 3, G–I). In total, the positive rate for ERG-related rearrangements as well as TMPRSS2-ETV1 and TMPRSS2-ETV4 fusions in the 20 prostate biopsy specimens was 60.0% (12/20).

Figure 3.

H&E stains, immunostaining, and corresponding FISH images of the TMPRSS2-ETS fusion assay in prostatic biopsy tissue. A: A prostatic gland with focal basal membrane disruption. B: FISH ERG probe images of the green boxed areas in A, demonstrating the presence of ERG-related rearrangements through partial deletion or translocation of the gene. C: Immunostaining of a prostatic gland in A by primary antibodies against 34βE12, p63, and AMACR, showing focal basal membrane disruption. D: An abnormal gland with focal basal membrane disruption surrounding benign prostatic glands. E: FISH TMPRSS2-ETV1 probes image of the green boxed area in D, indicating the presence of the TMPRSS2-ETV1 fusion. F: Immunostaining of a prostatic gland in D by primary antibodies against 34βE12, p63, and AMACR, showing focal basal membrane disruption. G: An abnormal gland with focal membrane disruption surrounding a benign prostatic gland. H: FISH TMPRSS2-ETV4 probes image of the green boxed area in E, indicating the presence of the TMPRSS2-ETV4 fusion. I: Immunostaining of a prostatic gland in G by primary antibodies against 34βE12, p63, and AMACR, showing focal basal membrane disruption. Original magnification of H&E images, ×20 objective. Original magnification of FISH images, oil objective (×100).

Discussion

At present, prostate biopsy is the conventional diagnostic approach for patients with an elevated PSA level of more than 3.0 ng/ml, which can detect prostate cancer in only about a third of the patients.13 Moreover, pathological manifestations of early stages prostate cancer are mainly associated with the organization structure changes, but not the typical pathological changes of the cells, which are vulnerable to the experience of pathologists.14 Numerous promising prostate cancer related biomarkers have been identified, including some genes specific for prostate cancer, such as AMACR, GOLPH2, SPINK1, TFF3, PCA3, and recurrent gene fusions involving TMPRSS2 and ETS family members.15,16,17 In 2005, fusions of the 5′-untranslated region of TMPRSS2 with the ETS transcription factors (ERG, ETV1, and ETV4) were reported by Tomlins et al in prostate cancer, which was considered as the most common rearrangements identified in human malignancies.2 Since then, several studies have reported on the diagnostic potential of TMPRSS2-ETS fusions. TMPRSS2-ERG fusion transcripts were detected by RT-PCR in post-DRE urine samples from prostate cancer patients with the sensitivity at 32–42% and specificity at 93%,17,18 as well as in 15–20% of men with prostate cancer but having a normal DRE and a PSA level <4.0 ng/ml.19,20 However, the biological and clinical role of TMPRSS2-ETS fusions in prostate cancer, especially in problematic prostate needle core biopsies, has not been rigorously evaluated.

Our present results demonstrated that the ERG rearrangements were present in 78.0% of cases (39/50), consistent with the previous studies by other groups who reported the presence of such rearrangements in 40–80% of cases.2,4,5,6 Recently, conflicting data indicated the association of ERG related rearrangements with both improved and worsened patient outcomes. Many studies were unable to determine the association of ERG rearrangements with PSA recurrence and instead reported the association with assumed surrogates of cancer risk such as disease stage and Gleason grade.4,21 While some studies showed the correlation of ERG rearrangements with higher stage disease,4 others reported either no association with Gleason score7,21 or an association with lower Gleason score and better survival.6 The limitations of small cohort sample size and varied populations are likely responsible for these inconsistent findings and have led to the lack of consensus about whether the TMPRSS2-ETS gene fusions influence the risk of prostate cancer progression. In the present study, we did not observe any statistically significant association between the TMPRSS2-ETS fusion status and preoperative serum PSA, pTNM stage, and Gleason score.

Although the exact mechanism of ERG-related rearrangements primarily involving the TMPRSS2-ERG fusion is yet to be unraveled, this gene fusion has been considered as an early event involved in the development of prostate cancer. Several studies suggested that the TMPRSS2-ERG fusion protein was also present in benign prostatic hyperplasia,22 high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia,23 and even in nonmalignant tissue adjacent to prostate cancer foci22,23; however, the fact that our studies did not show TMPRSS2-ETS fusions in any of the 15 normal prostate and 20 benign prostatic hyperplasia samples demonstrated the specificity of TMPRSS2-ETS fusions in associations with prostate cancer. A significant clinical implication of our findings is to assess the TMPRSS2-ETS fusion status in problematic prostate needle core biopsies with high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and focal basement membrane disruption. Our results showed the positive rate for ERG rearrangements as well as TMPRSS2-ETV1 and TMPRSS2-ETV4 fusions in the initial prostate cancer-negative biopsies of 20 patients who were eventually diagnosed with prostate cancer at 60.0% (12/20), indicating that detection of such abnormalities by multiprobe FISH could be an extremely useful ancillary test for the early diagnosis of prostate cancer, given the number of prostate needle biopsies unable to yield a definitive diagnosis is significant. Basal cell specific immunohistochemical markers (eg, 34βE12 and p63) and AMACR have been used as an adjunct in establishing a definitive diagnosis.15,24 When used in combination, these immunostains can assist a definitive diagnosis in about 70% of the cases. Implementation of the detection of TMPRSS2-ETS fusions by multiprobe FISH assay might increase the percentage even higher, considering this approach is a very specific and sensitive assay for the detection of gene rearrangements positive cancers.

Notably, one would envision that at least a few patients who underwent transurethral resection of the prostate would at some point have prostate carcinoma. In our opinion, the patient selection and follow-up time represent the key to the explanation of our results (that is, none of the negative transurethral resection of the prostate sections revealed translocations). All patients who underwent transurethral resection of the prostate have been re-reviewed in an adequate follow-up (at least 60 months) to support a no tumor outcome, whereas 20 retrospectively selected patients with initial negative biopsy results for cancer progressed to prostate cancer as confirmed by subsequent repeat prostate biopsies (follow-up time: 15–48 months). The positive rate for ERG related rearrangements as well as TMPRSS2-ETV1 and TMPRSS2-ETV4 fusions in the 20 initial prostate cancer-negative biopsy specimens was 60.0% (12/20).

In summary, we demonstrated the usefulness of a multiprobe FISH assay on paraffin-embedded samples for the detection of TMPRSS2-ETS fusion genes in prostate cancer. There was no significant association between the fusion status and tumor stages. The clinical utility of TMPRSS2-ETS fusion detection as a biomarker and ancillary diagnostic tool for the early diagnosis of prostate cancer was promising, given this approach showed significant high sensitivity and specificity in detection.

Footnotes

Supported by the Chinese National Natural Science Foundation (30772178), Key Project of Chinese Ministry of Health, Chinese National Hi-Tech Research and Development Program (2007AA021906), and Program of 5010 of Sun-Yat Sen University (2007028).

Q.-P.S. and L.-Y.L. contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Catalona WJ, Hudson MA, Scardino PT, Richie JP, Ahmann FR, Flanigan RC, deKernion JB, Ratliff TL, Kavoussi LR, Dalkin BL. Selection of optimalprostate specific antigen cutoffs for early detection of prostate cancer: receiver operating characteristic curves. J Urol. 1994;152:2037–2042. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)32300-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tomlins SA, Rhodes DR, Perner S, Dhanasekaran SM, Mehra R, Sun XW, Varambally S, Cao X, Tchinda J, Kuefer R, Lee C, Montie JE, Shah RB, Pienta KJ, Rubin MA, Chinnaiyan AM. Recurrent fusion of TMPRSS2 and ETS transcription factor genes in prostate cancer. Science. 2005;310:644–648. doi: 10.1126/science.1117679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tomlins SA, Mehra R, Rhodes DR, Smith LR, Roulston D, Helgeson BE, Cao X, Wei JT, Rubin MA, Shah RB, Chinnaiyan AM. TMPRSS2: ETV4 gene fusions define a third molecular subtype of prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3396–3400. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mehra R, Tomlins SA, Shen R, Nadeem O, Wang L, Wei JT, Pienta KJ, Ghosh D, Rubin MA, Chinnaiyan AM, Shah RB. Comprehensive assessment of TMPRSS2 and ETS family gene aberrations in clinically localized prostate cancer. Mod Patho. 2007;20:538–544. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mosquera JM, Perner S, Demichelis F, Kim R, Hofer MD, Mertz KD, Paris PL, Simko J, Collins C, Bismar TA, Chinnaiyan AM, Rubin MA. Morphological features of TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion prostate cancer. J Pathol. 2007;212:91–101. doi: 10.1002/path.2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Winnes M, Lissbrant E, Damber JE, Stenman G. Molecular genetic analyses of the TMPRSS2-ERG and TMPRSS2-ETV1 gene fusions in 50 cases of prostate cancer. Oncol Rep. 2007;17:1033–1036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perner S, Mosquera JM, Demichelis F, Hofer MD, Paris PL, Simko J, Collins C, Bismar TA, Chinnaiyan AM, De Marzo AM, Rubin MA. TMPRSS2-ERG fusion prostate cancer: an early molecular event associated with invasion. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:882–888. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213424.38503.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foster CS. Cellular features distinguishing benign and malignant phenotypes in prostatic biopsies. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:1445–1447. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2000.21282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foster CS. Pathology of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Prostate Suppl. 2000;9:4–14. doi: 10.1002/1097-0045(2000)45:9+<4::aid-pros3>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foster CS, Falconer A, Dodson AR, Norman AR, Dennis N, Fletcher A, Southgate C, Dowe A, Dearnaley D, Jhavar S, Eeles R, Feber A, Cooper CS. Transcription factor E2F3 overexpressed in prostate cancer independently predicts clinical outcome. Oncogene. 2004;23:5871–5879. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang Z, Li C, Fischer A, Dresser K, Woda BA. Using an AMACR (P504S)/34betaE12/p63 cocktail for the detection of small focal prostate carcinoma in needle biopsy specimens. Am J Clin Pathol. 2005;123:231–236. doi: 10.1309/1g1nk9dbgfnb792l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stewart J, Fleshner N, Cole H, Toi A, Sweet J. Prognostic significance of alpha-methylacyl-coA racemase among men with high grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia in prostate biopsies. J Urol. 2008;179:1751–1755. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Djavan B, Remzi M, Schulman C, Marberger M, Zlotta A. Repeat prostate biopsy: who, how and when? Eur Urol. 2002;42:93–103. doi: 10.1016/s0302-2838(02)00256-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iczkowski KA, Bostwick DG. The pathologist as optimist: cancer grade deflation in prostatic needle biopsies. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:1169–1170. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199810000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rubin MA, Zhou M, Dhanasekaran SM, Varambally S, Barrette TR, Sanda MG, Pienta KJ, Ghosh D, Chinnaiyan AM. α-Methylacyl coenzyme A racemase as a tissue biomarker for prostate cancer. JAMA. 2002;287:1662–1670. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.13.1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Kok JB, Verhaegh GW, Roelofs RW, Hessels D, Kiemeney LA, Aalders TW, Swinkels DW, Schalken JA. DD3 (PCA3), a very sensitive and specific marker to detect prostate tumors. Cancer Res. 2002;62:2695–2698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laxman B, Morris DS, Yu J, Siddiqui J, Cao J, Mehra R, Lonigro RJ, Tsodikov A, Wei JT, Tomlins SA, Chinnaiyan AM. A first-generation multiplex biomarker analysis of urine for the early detection of prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:645–649. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hessels D, Smit FP, Verhaegh GW, Witjes JA, Cornel EB, Schalken JA. Detection of TMPRSS2-ERG fusion transcripts and prostate cancer antigen 3 in urinary sediments may improve diagnosis of prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:5103–5108. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tomlins SA, Bjartell A, Chinnaiyan AM, Jenster G, Nam RK, Rubin MA, Schalken JA. ETS gene fusions in prostate cancer: from discovery to daily clinical practice. Eur Urol. 2009;56:275–286. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahyai SA, Graefen M, Steuber T, Haese A, Schlomm T, Walz J, Köllermann J, Briganti A, Zacharias M, Friedrich MG, Karakiewicz PI, Montorsi F, Huland H, Chun FK. Contemporary prostate cancer prevalence among T1c biopsy-referred men with a prostate-specific antigen level < or = 4.0 ng per milliliter. Eur Urol. 2008;53:750–757. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lapointe J, Kim YH, Miller MA, Li C, Kaygusuz G, van de Rijn M, Huntsman DG, Brooks JD, Pollack JR. A variant TMPRSS2 isoform and ERG fusion product in prostate cancer with implications for molecular diagnosis. Mod Pathol. 2007;20:467–473. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clark J, Merson S, Jhavar S, Flohr P, Edwards S, Foster CS, Eeles R, Martin FL, Phillips DH, Crundwell M, Christmas T, Thompson A, Fisher C, Kovacs G, Cooper CS. Diversity of TMPRSS2-ERG fusion transcripts in the human prostate. Oncogene. 2007;26:2667–2673. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Furusato B, Gao CL, Ravindranath L, Chen Y, Cullen J, McLeod DG, Dobi A, Srivastava S, Petrovics G, Sesterhenn IA. Mapping of TMPRSS2-ERG fusions in the context of multi-focal prostate cancer. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:67–75. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Browne TJ, Hirsch MS, Brodsky G, Welch WR, Loda MF, Rubin MA. Prospective evaluation of AMACR (P504S) and basal cell markers in the assessment of routine prostate needle biopsy specimens. Hum Pathol. 2004;35:1462–1468. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]